User login

Medical Complications and Outcomes After Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Nationwide Analysis

ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of evidence describing the types and rates of postoperative complications following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). We sought to analyze the complications following TSA and determine their effects on described outcome measures.

Using discharge data from the weighted Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2010, patients who underwent primary TSA were identified. The prevalence of specific complications was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. The data from this database represent events occurring during admission, prior to discharge. The associations between patient characteristics, complications, and outcomes of TSA were evaluated. The specific outcomes analyzed in this study were mortality and length of stay (LOS).

A total of 125,766 patients were identified. The rate of complication after TSA was 6.7% (8457 patients). The most frequent complications were respiratory, renal, and cardiac, occurring in 2.9%, 0.8%, and 0.8% of cases, respectively. Increasing age and total number of preoperative comorbidities significantly increased the likelihood of having a complication. The prevalence of postoperative shock and central nervous system, cardiac, vascular, and respiratory complications was significantly higher in patients who suffered postoperative mortality (88 patients; 0.07% mortality rate) than in those who survived surgery (P < 0.0001). In terms of LOS, shock and infectious and vascular complications most significantly increased the length of hospitalization.

Postoperative complications following TSA are not uncommon and occur in >6% of patients. Older patients and certain comorbidities are associated with complications after surgery. These complications are associated with postoperative mortality and increased LOS.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) provides a predictably high level of satisfaction with survival as high as 92% at 15 years.1 As implant instrumentation and surgical technique and understanding have improved, the frequency of TSAs being performed has also increased.2 Although there are enough data on long-term surgical complications following TSA,1,3-6 there is a paucity of evidence delineating the incidence and types of postoperative complications during hospitalization. Several current issues motivate the improved understanding of TSA, including the increasing number of TSAs being performed, the desire to improve quality of care, and the desire to create financially efficient healthcare.

The purpose of this study is to detail the postoperative complications that occur following TSA using a large national database. Specifically, our goals are to determine the incidence and types of complications after shoulder arthroplasty, determine the patient factors that are associated with these complications, and evaluate the effects of these complications on postoperative in-hospital mortality and length of stay (LOS). Our hypothesis is that there would be a correlation between specific patient factors and complications and that these complications would adversely correlate to patient postoperative outcomes.

METHODS

DESIGN

We conducted a retrospective analysis of TSAs captured by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database between 2006 and 2010. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database that is currently available to the public in the United States.7

The NIS is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the US Department of Health and Human Services. The NIS database is designed to approximate a 20% sample of US hospitals and the patients they serve, including community, academic, general, and specialty-specific hospitals such as orthopedic hospitals.7 The 2010 update of the NIS database contains discharge data from 1051 hospitals across 45 states, with a representative sample of >39 million inpatient hospital stays.7 The NIS database and its data sources have been independently validated and assessed for quality each year since 1988.8Furthermore, comparative analysis of multiple database elements and distributions has been validated against standard norms, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey.9 The NIS database has been used in numerous published studies.2,10,11

PATIENT SELECTION

The yearly NIS databases from 2006 to 2010 were compiled. Patients aged ≥40 years who underwent a TSA were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9), procedural code 81.80. Exclusion criteria were patients with a primary or a secondary diagnosis of humeral or scapular fracture, chronic osteomyelitis, rheumatologic diseases, or evidence of concurrent malignancy (Figure 1).

Native to NIS are patient demographics, including age, sex, and race. Patient comorbidities as described by Elixhauser and colleagues12 are also included in the database.

Continue to: OUTCOMES...

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome of this study was a description of the type and frequency of postoperative complications of TSA. To conduct this analysis, we queried the TSA cohort for specific ICD-9 codes representing acute cardiac, central nervous system, infectious, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, postoperative shock, renal, respiratory, surgical, vascular, and wound complications. The ICD-9 codes used to identify complications were modeled according to previous literature on various surgical applications and were further parsed to reflect only acute postoperative diagnoses13-15(see the Appendix for the comprehensive list of ICD-9 codes).

Two additional outcomes were analyzed, including postoperative mortality and LOS. Postoperative mortality was defined as death occurring prior to discharge. We calculated the average LOS among the complication and the noncomplication cohort.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Patient demographics and target outcomes of the study were analyzed by frequency distribution. Where applicable, the chi-square and the Student’s t tests were used to confirm the statistical difference for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariate regressions were performed after controlling for possible clustering of the data using a generalized estimating equation following a previous analytical methodology.16-20 The results are reported with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals where applicable, all statistical tests with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to be significant, and all statistical tests were two-sided. We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

From 2006 to 2010, a weighted sample of 141,973 patients was found to undergo a TSA. After applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria, our study cohort consisted of 125,766 patients (Figure 1).

Continue to: OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS...

OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

The average age of the TSA cohort was 69.4 years (standard deviation [SD], 21.20), and 54.1% were females. The cohort had significant comorbidities, with 83.3% of them having at least 1 comorbidity at the time of surgery. Specifically, 31.3% of the patients had 1 comorbidity, 26.5% had 2 comorbidities, and 25.4% had ≥3 comorbidities. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity present in 66.2% of patients, and diabetes was the second most common comorbidity with a prevalence of 16.8%.

COMPLICATION COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

An overall postoperative complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients) was noted in the overall TSA cohort. The TSA cohort was dichotomized into patients who suffered at least 1 complication (weighted, n = 8457) and patients undergoing routine TSAs (weighted, n = 117,308). The average age was significantly higher in the complication vs routine cohort (71.38 vs 69.27 years, P < 0.0001). Similarly, there were significantly more comorbidities (2.51 vs 1.71, P < 0.0001) in the complication cohort.

COMPLICATIONS

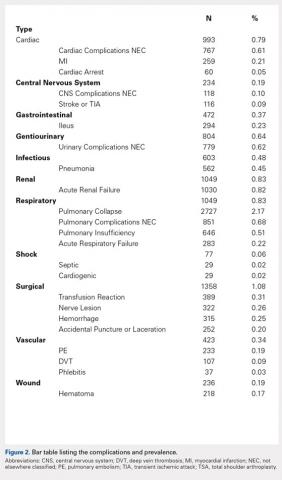

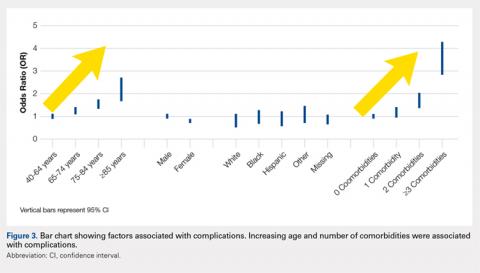

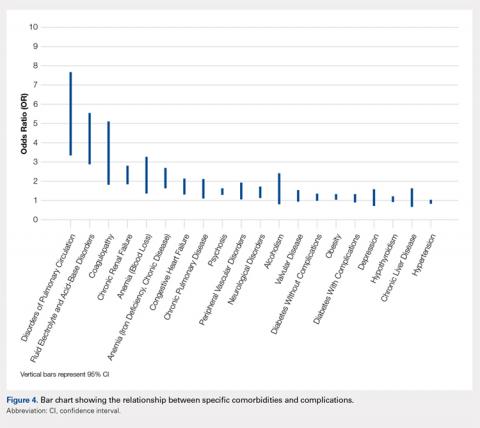

We noted a complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients). A single complication was noted in 5% of these patients, whereas 1.3% and 0.4% of the patients had 2 and ≥3 complications, respectively. Respiratory abnormalities (2.9%), acute renal failure (0.8%), and cardiac complications (0.8%) were the most prevalent complications after TSA. The list of complications is detailed in Figure 2. Logistic regression analysis of patient characteristics predicting complications showed that advanced age (odds ratio [OR], 2.1 in those aged ≥85 years) and increasing number of comorbidities (≥3; OR, 3.5) were most significant in predicting complications (all P < 0.0001) (Figure 3). Despite the ubiquity of hypertension in this patient population, it was not a significant predictor of complication (OR, 0.9); in contrast, pulmonary disorders (OR, 5.1) and fluid and electrolyte disorders (4.0) were most strongly associated with the development of a postoperative complication after surgery (Figure 4).

EFFECT OF COMPLICATIONS ON LOS

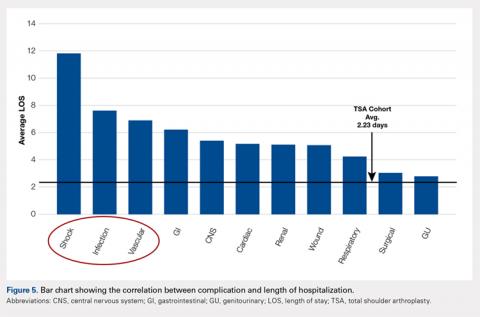

The average length of hospitalization was 2.3 days (95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.25) among the entire cohort. The average LOS was longer in the complication cohort (3.9 days) than in patients who did not have a complication (2.1 days, P < 0.0001). Of the specific complications noted, hemodynamic shock (11.8 days); infectious, most commonly pneumonia (7.6 days); and vascular complications (6.9 days) were associated with the longest hospitalizations. This result is summarized in Figure 5.

MORTALITY

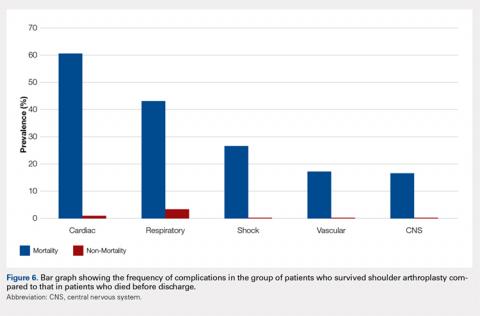

An overall postoperative (in-house) mortality rate of 0.07% was noted (weighted, n = 88). Comparison between the patient cohort that died vs those who survived TSA resulted in significant differences in the rates of complications. Complications that were most significantly different between the cohorts included cardiac (60.47% vs 0.75%, P < 0.0001), postoperative shock (26.61% vs 0.04%, P < 0.0001), and respiratory complications (43.1% vs 2.8%, P < 0.0001). It is important to note that the overall rate of postoperative shock was exceedingly low in the TSA cohort, but it was highly prevalent in the mortality cohort, occurring in 26.61% of patients. A summary of the mortality statistics is presented in Figure 6.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

TSA continues to be associated with high levels of satisfaction;1 as a result, its incidence is increasing.2 As our understanding and efficiency improves nationally, it is imperative that we determine the short-term and longer-term outcomes and complications. In addition, the factors that may affect prognosis must be elucidated to provide a more individualized and effective standard of care. To date, most of the outcome studies of TSA have evaluated long-term outcomes and specific implant-related complications.1,5,6,21,22 Our intent was to evaluate the complications that occur in the postoperative period and their effect on unique “patient care” outcomes. With knowledge of these complications and the predisposing factors, we can better assess patients, risk-stratify, and provide appropriate guidelines.

We noted that complications occurring after TSA are not uncommon, with >6% of patients suffering a postoperative complication. In this study, the number of complications noted was associated with worse patient outcomes. In addition, we noted that patients undergoing a TSA have a significant burden of comorbidities; however, hematologic and fluid disorders (eg, iron deficiency anemia, pulmonary circulatory disorders, and fluid imbalances) were most important in predicting postoperative complications.

Increased LOS in the hospital after TSA was associated with the occurrence of complications. Of all noted complications, shock and infectious and vascular complications led to the longest hospitalizations. Hospital-acquired pneumonia was the most common infectious etiology, while pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis were the most consistent vascular complications. Although seldom studied in the TSA population, a similar finding has been noted in patients after THA. O’Malley and colleagues,23 using the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, identified independent factors that were associated with complications and average prolonged LOS. They noted that the occurrence of major complications was associated with a prolonged LOS. Some, but not all the major complications, included organ space infection, cardiac events, pneumonia, and venous thromboembolic events.23 Therefore, attempts to limit the amount of time spent in hospitals and control the associated costs must focus on managing the incidence of complications.

Postoperative mortality after TSA was uncommon, occurring in 0.07% of the patients in this study. The low incidence of mortality noted in this study is probably related to the fact that our data represent mortality, whereas in the hospital and, unlike most mortality studies, it does not account for patient demise that may occur in the months after surgery. Other reports have noted that mortality occurs in <1.5% of these patients.24-28 Singh and colleagues25 observed in their evaluation of perioperative mortality after TSA a mortality rate of 0.8% with 90 days after 4380 shoulder replacements performed at their institution. Using multivariate analysis, they were able to identify associations between mortality and increasing American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class and Charlson Comorbidity Index. These results in relation to ours would indicate that the majority of patients who die after shoulder arthroplasty do so after initial discharge. Although we could not determine a causal relationship between mortality and patient comorbidities, we noted that certain complications strongly correlated with mortality. In patients who died, there was a relatively high incidence of cardiac (60.5%) and respiratory (43.1%) complications. Similarly, although postoperative shock was almost nonexistent in the patients who survived surgery (0.04%), it was much more common in the patients who suffered mortality (26.6%).

This study is not without limitations. Data were extracted from a national database, therefore precluding the inclusion of specific details of surgery and functional assessment. Inherent to ICD-9 coding, we were unable to assess the exact detail and severity of complications. For instance, we cannot be certain what criteria were used to define “acute renal failure” for each patient. This study is retrospective in nature and therefore adequate randomization and standardization of patients is not possible. Similarly, the nature of the database may not allow for exacting our inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, the large sample size of the patient population lessens the chance of potential biases and type 2 errors. Prior to October 2010, reverse shoulder arthroplasty was coded under the ICD-9procedural code 81.80 as TSA. Therefore, there is some overlap between TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty in our data. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty is now coded under ICD-9 procedural code 81.88. It is possible that results may differ if reverse shoulder arthroplasty were excluded from our patient cohort. This can be an area of future research.

CONCLUSION

Although much is known about the long-term hardware and functional complications after TSA, in this study, we have attempted to broaden the understanding of perioperative complications and the associated sequelae. Complications are common after TSA surgery and are related to adverse outcomes. In the setting of healthcare changes, the surgeon and the patient must understand the cause, types, incidence, and outcomes of medical and surgical complications after surgery. This allows for more accurate “standard of care” metrics. Further large-volume multicenter studies are needed to gain further insight into the short- and long-term outcomes of TSA.

1. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

2. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01994.

3. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution's experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43–48. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.03.010.

4. Boyd AD Jr, Aliabadi P, Thornhill TS. Postoperative proximal migration in total shoulder arthroplasty. Incidence and significance. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6(1):31-37. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80154-3.

5. Choi T, Horodyski M, Struk AM, Sahajpal DT, Wright TW. Incidence of early radiolucent lines after glenoid component insertion for total shoulder arthroplasty: a radiographic study comparing pressurized and unpressurized cementing techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):403-408. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.05.041.

6. Favard L, Katz D, Colmar M, Benkalfate T, Thomazeau H, Emily S. Total shoulder arthroplasty - arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthropathies: results and complications after a minimum follow-up of 8 years according to the type of arthroplasty and etiology. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4 Suppl):S41-S47. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2012.04.003.

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Introduction to the HCUP national inpatient sample (NIS) 2012. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NISIntroduction2012.pdf 2012. Accessed June 9, 2013.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP quality control procedures. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/quality.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2013.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative analysis of HCUP and NHDS inpatient discharge data: technical supplement 13. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/nhds/niscomp.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

10. Rajaee SS, Trofa D, Matzkin E, Smith E. National trends in primary total hip arthroplasty in extremely young patients: a focus on bearing surface usage. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1870-1878. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.006.

11. Bozic KJ, Kurtz S, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of bearing surface usage in total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1614-1620. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.01220.

12. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

13. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

14. Lin CA, Kuo AC, Takemoto S. Comorbidities and perioperative complications in HIV-positive patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):1028-1036. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00269.

15. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.001.

16. Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1138-1144. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa011788.

17. Hu JC, Gold KF, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Temporal trends in radical prostatectomy complications from 1991 to 1998. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1443-1448. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000056046.16588.e4.

18. Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, et al. Surgical caseload is an important determinant of continent urinary diversion rate at radical cystectomy: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(9):2680-2687. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1618-2.

19. Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, Bach PB, Begg CB. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(8):658-665. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009.

20. Joice GA, Deibert CM, Kates M, Spencer BA, McKiernan JM. "Never events”: centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services complications after radical cystectomy. Urology. 2013;81(3):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.050.

21. Taunton MJ, McIntosh AL, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with a metal-backed, bone-ingrowth glenoid component. Medium to long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(10):2180-2188. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00966.

22. Raiss P, Schmitt M, Bruckner T, et al. Results of cemented total shoulder replacement with a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):e1711-e1710. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00580.

23. O'Malley NT, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing SP, Kates SL. Factors independently associated with complications and length of stay after hip arthroplasty: analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1832-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.025.

24. White CB, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Ninety-day mortality after shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7):886-888. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00269-9.

25. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Ninety day mortality and its predictors after primary shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 4,019 patients from 1976-2008. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:231. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-231.

26. Fehringer EV, Mikuls TR, Michaud KD, Henderson WG, O'Dell JR. Shoulder arthroplasties have fewer complications than hip or knee arthroplasties in US veterans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):717-722. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0996-2.

27. Farmer KW, Hammond JW, Queale WS, Keyurapan E, McFarland EG. Shoulder arthroplasty versus hip and knee arthroplasties: a comparison of outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:183-189. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000238839.26423.8d.

28. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of evidence describing the types and rates of postoperative complications following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). We sought to analyze the complications following TSA and determine their effects on described outcome measures.

Using discharge data from the weighted Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2010, patients who underwent primary TSA were identified. The prevalence of specific complications was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. The data from this database represent events occurring during admission, prior to discharge. The associations between patient characteristics, complications, and outcomes of TSA were evaluated. The specific outcomes analyzed in this study were mortality and length of stay (LOS).

A total of 125,766 patients were identified. The rate of complication after TSA was 6.7% (8457 patients). The most frequent complications were respiratory, renal, and cardiac, occurring in 2.9%, 0.8%, and 0.8% of cases, respectively. Increasing age and total number of preoperative comorbidities significantly increased the likelihood of having a complication. The prevalence of postoperative shock and central nervous system, cardiac, vascular, and respiratory complications was significantly higher in patients who suffered postoperative mortality (88 patients; 0.07% mortality rate) than in those who survived surgery (P < 0.0001). In terms of LOS, shock and infectious and vascular complications most significantly increased the length of hospitalization.

Postoperative complications following TSA are not uncommon and occur in >6% of patients. Older patients and certain comorbidities are associated with complications after surgery. These complications are associated with postoperative mortality and increased LOS.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) provides a predictably high level of satisfaction with survival as high as 92% at 15 years.1 As implant instrumentation and surgical technique and understanding have improved, the frequency of TSAs being performed has also increased.2 Although there are enough data on long-term surgical complications following TSA,1,3-6 there is a paucity of evidence delineating the incidence and types of postoperative complications during hospitalization. Several current issues motivate the improved understanding of TSA, including the increasing number of TSAs being performed, the desire to improve quality of care, and the desire to create financially efficient healthcare.

The purpose of this study is to detail the postoperative complications that occur following TSA using a large national database. Specifically, our goals are to determine the incidence and types of complications after shoulder arthroplasty, determine the patient factors that are associated with these complications, and evaluate the effects of these complications on postoperative in-hospital mortality and length of stay (LOS). Our hypothesis is that there would be a correlation between specific patient factors and complications and that these complications would adversely correlate to patient postoperative outcomes.

METHODS

DESIGN

We conducted a retrospective analysis of TSAs captured by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database between 2006 and 2010. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database that is currently available to the public in the United States.7

The NIS is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the US Department of Health and Human Services. The NIS database is designed to approximate a 20% sample of US hospitals and the patients they serve, including community, academic, general, and specialty-specific hospitals such as orthopedic hospitals.7 The 2010 update of the NIS database contains discharge data from 1051 hospitals across 45 states, with a representative sample of >39 million inpatient hospital stays.7 The NIS database and its data sources have been independently validated and assessed for quality each year since 1988.8Furthermore, comparative analysis of multiple database elements and distributions has been validated against standard norms, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey.9 The NIS database has been used in numerous published studies.2,10,11

PATIENT SELECTION

The yearly NIS databases from 2006 to 2010 were compiled. Patients aged ≥40 years who underwent a TSA were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9), procedural code 81.80. Exclusion criteria were patients with a primary or a secondary diagnosis of humeral or scapular fracture, chronic osteomyelitis, rheumatologic diseases, or evidence of concurrent malignancy (Figure 1).

Native to NIS are patient demographics, including age, sex, and race. Patient comorbidities as described by Elixhauser and colleagues12 are also included in the database.

Continue to: OUTCOMES...

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome of this study was a description of the type and frequency of postoperative complications of TSA. To conduct this analysis, we queried the TSA cohort for specific ICD-9 codes representing acute cardiac, central nervous system, infectious, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, postoperative shock, renal, respiratory, surgical, vascular, and wound complications. The ICD-9 codes used to identify complications were modeled according to previous literature on various surgical applications and were further parsed to reflect only acute postoperative diagnoses13-15(see the Appendix for the comprehensive list of ICD-9 codes).

Two additional outcomes were analyzed, including postoperative mortality and LOS. Postoperative mortality was defined as death occurring prior to discharge. We calculated the average LOS among the complication and the noncomplication cohort.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Patient demographics and target outcomes of the study were analyzed by frequency distribution. Where applicable, the chi-square and the Student’s t tests were used to confirm the statistical difference for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariate regressions were performed after controlling for possible clustering of the data using a generalized estimating equation following a previous analytical methodology.16-20 The results are reported with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals where applicable, all statistical tests with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to be significant, and all statistical tests were two-sided. We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

From 2006 to 2010, a weighted sample of 141,973 patients was found to undergo a TSA. After applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria, our study cohort consisted of 125,766 patients (Figure 1).

Continue to: OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS...

OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

The average age of the TSA cohort was 69.4 years (standard deviation [SD], 21.20), and 54.1% were females. The cohort had significant comorbidities, with 83.3% of them having at least 1 comorbidity at the time of surgery. Specifically, 31.3% of the patients had 1 comorbidity, 26.5% had 2 comorbidities, and 25.4% had ≥3 comorbidities. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity present in 66.2% of patients, and diabetes was the second most common comorbidity with a prevalence of 16.8%.

COMPLICATION COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

An overall postoperative complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients) was noted in the overall TSA cohort. The TSA cohort was dichotomized into patients who suffered at least 1 complication (weighted, n = 8457) and patients undergoing routine TSAs (weighted, n = 117,308). The average age was significantly higher in the complication vs routine cohort (71.38 vs 69.27 years, P < 0.0001). Similarly, there were significantly more comorbidities (2.51 vs 1.71, P < 0.0001) in the complication cohort.

COMPLICATIONS

We noted a complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients). A single complication was noted in 5% of these patients, whereas 1.3% and 0.4% of the patients had 2 and ≥3 complications, respectively. Respiratory abnormalities (2.9%), acute renal failure (0.8%), and cardiac complications (0.8%) were the most prevalent complications after TSA. The list of complications is detailed in Figure 2. Logistic regression analysis of patient characteristics predicting complications showed that advanced age (odds ratio [OR], 2.1 in those aged ≥85 years) and increasing number of comorbidities (≥3; OR, 3.5) were most significant in predicting complications (all P < 0.0001) (Figure 3). Despite the ubiquity of hypertension in this patient population, it was not a significant predictor of complication (OR, 0.9); in contrast, pulmonary disorders (OR, 5.1) and fluid and electrolyte disorders (4.0) were most strongly associated with the development of a postoperative complication after surgery (Figure 4).

EFFECT OF COMPLICATIONS ON LOS

The average length of hospitalization was 2.3 days (95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.25) among the entire cohort. The average LOS was longer in the complication cohort (3.9 days) than in patients who did not have a complication (2.1 days, P < 0.0001). Of the specific complications noted, hemodynamic shock (11.8 days); infectious, most commonly pneumonia (7.6 days); and vascular complications (6.9 days) were associated with the longest hospitalizations. This result is summarized in Figure 5.

MORTALITY

An overall postoperative (in-house) mortality rate of 0.07% was noted (weighted, n = 88). Comparison between the patient cohort that died vs those who survived TSA resulted in significant differences in the rates of complications. Complications that were most significantly different between the cohorts included cardiac (60.47% vs 0.75%, P < 0.0001), postoperative shock (26.61% vs 0.04%, P < 0.0001), and respiratory complications (43.1% vs 2.8%, P < 0.0001). It is important to note that the overall rate of postoperative shock was exceedingly low in the TSA cohort, but it was highly prevalent in the mortality cohort, occurring in 26.61% of patients. A summary of the mortality statistics is presented in Figure 6.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

TSA continues to be associated with high levels of satisfaction;1 as a result, its incidence is increasing.2 As our understanding and efficiency improves nationally, it is imperative that we determine the short-term and longer-term outcomes and complications. In addition, the factors that may affect prognosis must be elucidated to provide a more individualized and effective standard of care. To date, most of the outcome studies of TSA have evaluated long-term outcomes and specific implant-related complications.1,5,6,21,22 Our intent was to evaluate the complications that occur in the postoperative period and their effect on unique “patient care” outcomes. With knowledge of these complications and the predisposing factors, we can better assess patients, risk-stratify, and provide appropriate guidelines.

We noted that complications occurring after TSA are not uncommon, with >6% of patients suffering a postoperative complication. In this study, the number of complications noted was associated with worse patient outcomes. In addition, we noted that patients undergoing a TSA have a significant burden of comorbidities; however, hematologic and fluid disorders (eg, iron deficiency anemia, pulmonary circulatory disorders, and fluid imbalances) were most important in predicting postoperative complications.

Increased LOS in the hospital after TSA was associated with the occurrence of complications. Of all noted complications, shock and infectious and vascular complications led to the longest hospitalizations. Hospital-acquired pneumonia was the most common infectious etiology, while pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis were the most consistent vascular complications. Although seldom studied in the TSA population, a similar finding has been noted in patients after THA. O’Malley and colleagues,23 using the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, identified independent factors that were associated with complications and average prolonged LOS. They noted that the occurrence of major complications was associated with a prolonged LOS. Some, but not all the major complications, included organ space infection, cardiac events, pneumonia, and venous thromboembolic events.23 Therefore, attempts to limit the amount of time spent in hospitals and control the associated costs must focus on managing the incidence of complications.

Postoperative mortality after TSA was uncommon, occurring in 0.07% of the patients in this study. The low incidence of mortality noted in this study is probably related to the fact that our data represent mortality, whereas in the hospital and, unlike most mortality studies, it does not account for patient demise that may occur in the months after surgery. Other reports have noted that mortality occurs in <1.5% of these patients.24-28 Singh and colleagues25 observed in their evaluation of perioperative mortality after TSA a mortality rate of 0.8% with 90 days after 4380 shoulder replacements performed at their institution. Using multivariate analysis, they were able to identify associations between mortality and increasing American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class and Charlson Comorbidity Index. These results in relation to ours would indicate that the majority of patients who die after shoulder arthroplasty do so after initial discharge. Although we could not determine a causal relationship between mortality and patient comorbidities, we noted that certain complications strongly correlated with mortality. In patients who died, there was a relatively high incidence of cardiac (60.5%) and respiratory (43.1%) complications. Similarly, although postoperative shock was almost nonexistent in the patients who survived surgery (0.04%), it was much more common in the patients who suffered mortality (26.6%).

This study is not without limitations. Data were extracted from a national database, therefore precluding the inclusion of specific details of surgery and functional assessment. Inherent to ICD-9 coding, we were unable to assess the exact detail and severity of complications. For instance, we cannot be certain what criteria were used to define “acute renal failure” for each patient. This study is retrospective in nature and therefore adequate randomization and standardization of patients is not possible. Similarly, the nature of the database may not allow for exacting our inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, the large sample size of the patient population lessens the chance of potential biases and type 2 errors. Prior to October 2010, reverse shoulder arthroplasty was coded under the ICD-9procedural code 81.80 as TSA. Therefore, there is some overlap between TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty in our data. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty is now coded under ICD-9 procedural code 81.88. It is possible that results may differ if reverse shoulder arthroplasty were excluded from our patient cohort. This can be an area of future research.

CONCLUSION

Although much is known about the long-term hardware and functional complications after TSA, in this study, we have attempted to broaden the understanding of perioperative complications and the associated sequelae. Complications are common after TSA surgery and are related to adverse outcomes. In the setting of healthcare changes, the surgeon and the patient must understand the cause, types, incidence, and outcomes of medical and surgical complications after surgery. This allows for more accurate “standard of care” metrics. Further large-volume multicenter studies are needed to gain further insight into the short- and long-term outcomes of TSA.

ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of evidence describing the types and rates of postoperative complications following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). We sought to analyze the complications following TSA and determine their effects on described outcome measures.

Using discharge data from the weighted Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2010, patients who underwent primary TSA were identified. The prevalence of specific complications was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. The data from this database represent events occurring during admission, prior to discharge. The associations between patient characteristics, complications, and outcomes of TSA were evaluated. The specific outcomes analyzed in this study were mortality and length of stay (LOS).

A total of 125,766 patients were identified. The rate of complication after TSA was 6.7% (8457 patients). The most frequent complications were respiratory, renal, and cardiac, occurring in 2.9%, 0.8%, and 0.8% of cases, respectively. Increasing age and total number of preoperative comorbidities significantly increased the likelihood of having a complication. The prevalence of postoperative shock and central nervous system, cardiac, vascular, and respiratory complications was significantly higher in patients who suffered postoperative mortality (88 patients; 0.07% mortality rate) than in those who survived surgery (P < 0.0001). In terms of LOS, shock and infectious and vascular complications most significantly increased the length of hospitalization.

Postoperative complications following TSA are not uncommon and occur in >6% of patients. Older patients and certain comorbidities are associated with complications after surgery. These complications are associated with postoperative mortality and increased LOS.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) provides a predictably high level of satisfaction with survival as high as 92% at 15 years.1 As implant instrumentation and surgical technique and understanding have improved, the frequency of TSAs being performed has also increased.2 Although there are enough data on long-term surgical complications following TSA,1,3-6 there is a paucity of evidence delineating the incidence and types of postoperative complications during hospitalization. Several current issues motivate the improved understanding of TSA, including the increasing number of TSAs being performed, the desire to improve quality of care, and the desire to create financially efficient healthcare.

The purpose of this study is to detail the postoperative complications that occur following TSA using a large national database. Specifically, our goals are to determine the incidence and types of complications after shoulder arthroplasty, determine the patient factors that are associated with these complications, and evaluate the effects of these complications on postoperative in-hospital mortality and length of stay (LOS). Our hypothesis is that there would be a correlation between specific patient factors and complications and that these complications would adversely correlate to patient postoperative outcomes.

METHODS

DESIGN

We conducted a retrospective analysis of TSAs captured by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database between 2006 and 2010. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database that is currently available to the public in the United States.7

The NIS is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the US Department of Health and Human Services. The NIS database is designed to approximate a 20% sample of US hospitals and the patients they serve, including community, academic, general, and specialty-specific hospitals such as orthopedic hospitals.7 The 2010 update of the NIS database contains discharge data from 1051 hospitals across 45 states, with a representative sample of >39 million inpatient hospital stays.7 The NIS database and its data sources have been independently validated and assessed for quality each year since 1988.8Furthermore, comparative analysis of multiple database elements and distributions has been validated against standard norms, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey.9 The NIS database has been used in numerous published studies.2,10,11

PATIENT SELECTION

The yearly NIS databases from 2006 to 2010 were compiled. Patients aged ≥40 years who underwent a TSA were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9), procedural code 81.80. Exclusion criteria were patients with a primary or a secondary diagnosis of humeral or scapular fracture, chronic osteomyelitis, rheumatologic diseases, or evidence of concurrent malignancy (Figure 1).

Native to NIS are patient demographics, including age, sex, and race. Patient comorbidities as described by Elixhauser and colleagues12 are also included in the database.

Continue to: OUTCOMES...

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome of this study was a description of the type and frequency of postoperative complications of TSA. To conduct this analysis, we queried the TSA cohort for specific ICD-9 codes representing acute cardiac, central nervous system, infectious, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, postoperative shock, renal, respiratory, surgical, vascular, and wound complications. The ICD-9 codes used to identify complications were modeled according to previous literature on various surgical applications and were further parsed to reflect only acute postoperative diagnoses13-15(see the Appendix for the comprehensive list of ICD-9 codes).

Two additional outcomes were analyzed, including postoperative mortality and LOS. Postoperative mortality was defined as death occurring prior to discharge. We calculated the average LOS among the complication and the noncomplication cohort.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Patient demographics and target outcomes of the study were analyzed by frequency distribution. Where applicable, the chi-square and the Student’s t tests were used to confirm the statistical difference for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariate regressions were performed after controlling for possible clustering of the data using a generalized estimating equation following a previous analytical methodology.16-20 The results are reported with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals where applicable, all statistical tests with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to be significant, and all statistical tests were two-sided. We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

From 2006 to 2010, a weighted sample of 141,973 patients was found to undergo a TSA. After applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria, our study cohort consisted of 125,766 patients (Figure 1).

Continue to: OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS...

OVERALL TSA COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

The average age of the TSA cohort was 69.4 years (standard deviation [SD], 21.20), and 54.1% were females. The cohort had significant comorbidities, with 83.3% of them having at least 1 comorbidity at the time of surgery. Specifically, 31.3% of the patients had 1 comorbidity, 26.5% had 2 comorbidities, and 25.4% had ≥3 comorbidities. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity present in 66.2% of patients, and diabetes was the second most common comorbidity with a prevalence of 16.8%.

COMPLICATION COHORT DEMOGRAPHICS

An overall postoperative complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients) was noted in the overall TSA cohort. The TSA cohort was dichotomized into patients who suffered at least 1 complication (weighted, n = 8457) and patients undergoing routine TSAs (weighted, n = 117,308). The average age was significantly higher in the complication vs routine cohort (71.38 vs 69.27 years, P < 0.0001). Similarly, there were significantly more comorbidities (2.51 vs 1.71, P < 0.0001) in the complication cohort.

COMPLICATIONS

We noted a complication rate of 6.7% (weighted sample of 8457 patients). A single complication was noted in 5% of these patients, whereas 1.3% and 0.4% of the patients had 2 and ≥3 complications, respectively. Respiratory abnormalities (2.9%), acute renal failure (0.8%), and cardiac complications (0.8%) were the most prevalent complications after TSA. The list of complications is detailed in Figure 2. Logistic regression analysis of patient characteristics predicting complications showed that advanced age (odds ratio [OR], 2.1 in those aged ≥85 years) and increasing number of comorbidities (≥3; OR, 3.5) were most significant in predicting complications (all P < 0.0001) (Figure 3). Despite the ubiquity of hypertension in this patient population, it was not a significant predictor of complication (OR, 0.9); in contrast, pulmonary disorders (OR, 5.1) and fluid and electrolyte disorders (4.0) were most strongly associated with the development of a postoperative complication after surgery (Figure 4).

EFFECT OF COMPLICATIONS ON LOS

The average length of hospitalization was 2.3 days (95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.25) among the entire cohort. The average LOS was longer in the complication cohort (3.9 days) than in patients who did not have a complication (2.1 days, P < 0.0001). Of the specific complications noted, hemodynamic shock (11.8 days); infectious, most commonly pneumonia (7.6 days); and vascular complications (6.9 days) were associated with the longest hospitalizations. This result is summarized in Figure 5.

MORTALITY

An overall postoperative (in-house) mortality rate of 0.07% was noted (weighted, n = 88). Comparison between the patient cohort that died vs those who survived TSA resulted in significant differences in the rates of complications. Complications that were most significantly different between the cohorts included cardiac (60.47% vs 0.75%, P < 0.0001), postoperative shock (26.61% vs 0.04%, P < 0.0001), and respiratory complications (43.1% vs 2.8%, P < 0.0001). It is important to note that the overall rate of postoperative shock was exceedingly low in the TSA cohort, but it was highly prevalent in the mortality cohort, occurring in 26.61% of patients. A summary of the mortality statistics is presented in Figure 6.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

TSA continues to be associated with high levels of satisfaction;1 as a result, its incidence is increasing.2 As our understanding and efficiency improves nationally, it is imperative that we determine the short-term and longer-term outcomes and complications. In addition, the factors that may affect prognosis must be elucidated to provide a more individualized and effective standard of care. To date, most of the outcome studies of TSA have evaluated long-term outcomes and specific implant-related complications.1,5,6,21,22 Our intent was to evaluate the complications that occur in the postoperative period and their effect on unique “patient care” outcomes. With knowledge of these complications and the predisposing factors, we can better assess patients, risk-stratify, and provide appropriate guidelines.

We noted that complications occurring after TSA are not uncommon, with >6% of patients suffering a postoperative complication. In this study, the number of complications noted was associated with worse patient outcomes. In addition, we noted that patients undergoing a TSA have a significant burden of comorbidities; however, hematologic and fluid disorders (eg, iron deficiency anemia, pulmonary circulatory disorders, and fluid imbalances) were most important in predicting postoperative complications.

Increased LOS in the hospital after TSA was associated with the occurrence of complications. Of all noted complications, shock and infectious and vascular complications led to the longest hospitalizations. Hospital-acquired pneumonia was the most common infectious etiology, while pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis were the most consistent vascular complications. Although seldom studied in the TSA population, a similar finding has been noted in patients after THA. O’Malley and colleagues,23 using the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, identified independent factors that were associated with complications and average prolonged LOS. They noted that the occurrence of major complications was associated with a prolonged LOS. Some, but not all the major complications, included organ space infection, cardiac events, pneumonia, and venous thromboembolic events.23 Therefore, attempts to limit the amount of time spent in hospitals and control the associated costs must focus on managing the incidence of complications.

Postoperative mortality after TSA was uncommon, occurring in 0.07% of the patients in this study. The low incidence of mortality noted in this study is probably related to the fact that our data represent mortality, whereas in the hospital and, unlike most mortality studies, it does not account for patient demise that may occur in the months after surgery. Other reports have noted that mortality occurs in <1.5% of these patients.24-28 Singh and colleagues25 observed in their evaluation of perioperative mortality after TSA a mortality rate of 0.8% with 90 days after 4380 shoulder replacements performed at their institution. Using multivariate analysis, they were able to identify associations between mortality and increasing American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class and Charlson Comorbidity Index. These results in relation to ours would indicate that the majority of patients who die after shoulder arthroplasty do so after initial discharge. Although we could not determine a causal relationship between mortality and patient comorbidities, we noted that certain complications strongly correlated with mortality. In patients who died, there was a relatively high incidence of cardiac (60.5%) and respiratory (43.1%) complications. Similarly, although postoperative shock was almost nonexistent in the patients who survived surgery (0.04%), it was much more common in the patients who suffered mortality (26.6%).

This study is not without limitations. Data were extracted from a national database, therefore precluding the inclusion of specific details of surgery and functional assessment. Inherent to ICD-9 coding, we were unable to assess the exact detail and severity of complications. For instance, we cannot be certain what criteria were used to define “acute renal failure” for each patient. This study is retrospective in nature and therefore adequate randomization and standardization of patients is not possible. Similarly, the nature of the database may not allow for exacting our inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, the large sample size of the patient population lessens the chance of potential biases and type 2 errors. Prior to October 2010, reverse shoulder arthroplasty was coded under the ICD-9procedural code 81.80 as TSA. Therefore, there is some overlap between TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty in our data. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty is now coded under ICD-9 procedural code 81.88. It is possible that results may differ if reverse shoulder arthroplasty were excluded from our patient cohort. This can be an area of future research.

CONCLUSION

Although much is known about the long-term hardware and functional complications after TSA, in this study, we have attempted to broaden the understanding of perioperative complications and the associated sequelae. Complications are common after TSA surgery and are related to adverse outcomes. In the setting of healthcare changes, the surgeon and the patient must understand the cause, types, incidence, and outcomes of medical and surgical complications after surgery. This allows for more accurate “standard of care” metrics. Further large-volume multicenter studies are needed to gain further insight into the short- and long-term outcomes of TSA.

1. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

2. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01994.

3. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution's experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43–48. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.03.010.

4. Boyd AD Jr, Aliabadi P, Thornhill TS. Postoperative proximal migration in total shoulder arthroplasty. Incidence and significance. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6(1):31-37. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80154-3.

5. Choi T, Horodyski M, Struk AM, Sahajpal DT, Wright TW. Incidence of early radiolucent lines after glenoid component insertion for total shoulder arthroplasty: a radiographic study comparing pressurized and unpressurized cementing techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):403-408. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.05.041.

6. Favard L, Katz D, Colmar M, Benkalfate T, Thomazeau H, Emily S. Total shoulder arthroplasty - arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthropathies: results and complications after a minimum follow-up of 8 years according to the type of arthroplasty and etiology. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4 Suppl):S41-S47. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2012.04.003.

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Introduction to the HCUP national inpatient sample (NIS) 2012. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NISIntroduction2012.pdf 2012. Accessed June 9, 2013.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP quality control procedures. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/quality.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2013.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative analysis of HCUP and NHDS inpatient discharge data: technical supplement 13. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/nhds/niscomp.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

10. Rajaee SS, Trofa D, Matzkin E, Smith E. National trends in primary total hip arthroplasty in extremely young patients: a focus on bearing surface usage. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1870-1878. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.006.

11. Bozic KJ, Kurtz S, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of bearing surface usage in total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1614-1620. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.01220.

12. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

13. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

14. Lin CA, Kuo AC, Takemoto S. Comorbidities and perioperative complications in HIV-positive patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):1028-1036. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00269.

15. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.001.

16. Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1138-1144. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa011788.

17. Hu JC, Gold KF, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Temporal trends in radical prostatectomy complications from 1991 to 1998. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1443-1448. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000056046.16588.e4.

18. Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, et al. Surgical caseload is an important determinant of continent urinary diversion rate at radical cystectomy: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(9):2680-2687. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1618-2.

19. Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, Bach PB, Begg CB. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(8):658-665. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009.

20. Joice GA, Deibert CM, Kates M, Spencer BA, McKiernan JM. "Never events”: centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services complications after radical cystectomy. Urology. 2013;81(3):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.050.

21. Taunton MJ, McIntosh AL, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with a metal-backed, bone-ingrowth glenoid component. Medium to long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(10):2180-2188. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00966.

22. Raiss P, Schmitt M, Bruckner T, et al. Results of cemented total shoulder replacement with a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):e1711-e1710. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00580.

23. O'Malley NT, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing SP, Kates SL. Factors independently associated with complications and length of stay after hip arthroplasty: analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1832-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.025.

24. White CB, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Ninety-day mortality after shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7):886-888. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00269-9.

25. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Ninety day mortality and its predictors after primary shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 4,019 patients from 1976-2008. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:231. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-231.

26. Fehringer EV, Mikuls TR, Michaud KD, Henderson WG, O'Dell JR. Shoulder arthroplasties have fewer complications than hip or knee arthroplasties in US veterans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):717-722. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0996-2.

27. Farmer KW, Hammond JW, Queale WS, Keyurapan E, McFarland EG. Shoulder arthroplasty versus hip and knee arthroplasties: a comparison of outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:183-189. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000238839.26423.8d.

28. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

1. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

2. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01994.

3. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution's experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43–48. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.03.010.

4. Boyd AD Jr, Aliabadi P, Thornhill TS. Postoperative proximal migration in total shoulder arthroplasty. Incidence and significance. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6(1):31-37. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80154-3.

5. Choi T, Horodyski M, Struk AM, Sahajpal DT, Wright TW. Incidence of early radiolucent lines after glenoid component insertion for total shoulder arthroplasty: a radiographic study comparing pressurized and unpressurized cementing techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):403-408. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.05.041.

6. Favard L, Katz D, Colmar M, Benkalfate T, Thomazeau H, Emily S. Total shoulder arthroplasty - arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthropathies: results and complications after a minimum follow-up of 8 years according to the type of arthroplasty and etiology. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4 Suppl):S41-S47. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2012.04.003.

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Introduction to the HCUP national inpatient sample (NIS) 2012. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NISIntroduction2012.pdf 2012. Accessed June 9, 2013.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP quality control procedures. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/quality.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2013.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative analysis of HCUP and NHDS inpatient discharge data: technical supplement 13. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/nhds/niscomp.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

10. Rajaee SS, Trofa D, Matzkin E, Smith E. National trends in primary total hip arthroplasty in extremely young patients: a focus on bearing surface usage. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1870-1878. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.006.

11. Bozic KJ, Kurtz S, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of bearing surface usage in total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1614-1620. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.01220.

12. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

13. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

14. Lin CA, Kuo AC, Takemoto S. Comorbidities and perioperative complications in HIV-positive patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):1028-1036. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00269.

15. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.001.

16. Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1138-1144. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa011788.

17. Hu JC, Gold KF, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Temporal trends in radical prostatectomy complications from 1991 to 1998. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1443-1448. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000056046.16588.e4.

18. Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, et al. Surgical caseload is an important determinant of continent urinary diversion rate at radical cystectomy: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(9):2680-2687. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1618-2.

19. Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, Bach PB, Begg CB. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(8):658-665. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009.

20. Joice GA, Deibert CM, Kates M, Spencer BA, McKiernan JM. "Never events”: centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services complications after radical cystectomy. Urology. 2013;81(3):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.050.

21. Taunton MJ, McIntosh AL, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with a metal-backed, bone-ingrowth glenoid component. Medium to long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(10):2180-2188. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00966.

22. Raiss P, Schmitt M, Bruckner T, et al. Results of cemented total shoulder replacement with a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):e1711-e1710. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00580.

23. O'Malley NT, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing SP, Kates SL. Factors independently associated with complications and length of stay after hip arthroplasty: analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1832-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.025.

24. White CB, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Ninety-day mortality after shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7):886-888. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00269-9.

25. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Ninety day mortality and its predictors after primary shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 4,019 patients from 1976-2008. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:231. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-231.

26. Fehringer EV, Mikuls TR, Michaud KD, Henderson WG, O'Dell JR. Shoulder arthroplasties have fewer complications than hip or knee arthroplasties in US veterans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):717-722. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0996-2.

27. Farmer KW, Hammond JW, Queale WS, Keyurapan E, McFarland EG. Shoulder arthroplasty versus hip and knee arthroplasties: a comparison of outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:183-189. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000238839.26423.8d.

28. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

TAKE HOME POINTS

- Medical complications are common (6.7%) after total shoulder arthroplasty.

- Age and preoperative medical comorbidities increased the risk of a postoperative complication.

- The most frequent medical complications are respiratory, renal, and cardiac.

- Length of stay was effected most by shock, infections, and vascular complications.

- Mortality was associated with major complications such as, shock, central nervous system, cardiac, vascular, and respiratory complications.

Proximal Humerus Fracture 3-D Modeling

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study is to determine the reproducibility and feasibility of using 3-dimensional (3-D) computer simulation of proximal humerus fracture computed tomography (CT) scans for fracture reduction. We hypothesized that anatomic reconstruction with 3-D models would be anatomically accurate and reproducible.

Preoperative CT scans of 28 patients with 3- and 4-part (AO classification 11-B1, 11-B2, 11-C1, 11-C2) proximal humerus fractures who were treated by hemiarthroplasty were converted into 3-D computer models. The displaced fractured fragments were anatomically reduced with computer simulation by 2 fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons, and measurements were made of the reconstructed proximal humerus.

The measurements of the reconstructed models had very good to excellent interobserver and intraobserver reliability. The reconstructions of these humerus fractures showed interclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.71 to 0.93 between 1 observer and from 0.82 to 0.98 between 2 different observers. The fracture reduction was judged against normal proximal humerus geometry to determine reduction accuracy.

The 3-D modeling techniques used to reconstruct 3- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures were reliable and accurate. This technique of modeling and reconstructing proximal humerus fractures could be used to enhance the preoperative planning of open reduction and internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty for 3- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures.

The treatment of proximal humerus fractures is influenced by multiple factors, including patient age, associated injuries, bone quality, and fracture pattern. Three- and 4-part fractures are among the more severe of these fractures, which may result in vascular compromise to the humeral head, leading to avascular necrosis. Surgical goals for the management of these fractures are to optimize functional outcomes by re-creating a stable construct with a functional rotator cuff by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), hemiarthroplasty with tuberosity ORIF, or reverse shoulder replacement. Achieving a good outcome following hemiarthroplasty is dependent on many factors, including anatomic tuberosity healing and component positioning.1,2,3 Repairing the greater tuberosity in a near-anatomic position has been shown to greatly affect the results of hemiarthroplasty for fracture.3,4

Continue to: Three-dimensional (3-D) modeling...

Three-dimensional (3-D) modeling is increasingly being used in preoperative planning of shoulder arthroplasty and determining proper proximal humeral fracture treatment. 5 However, no studies have examined the reconstruction of a fractured proximal humerus into native anatomy using computer simulation. The purpose of this study is to determine the accuracy and reliability of anatomically reconstructing the preinjury proximal humerus using 3-D computer models created from postinjury computed tomography (CT) scans. The results of this study could lead to useful techniques employing CT–based models for patient-specific preoperative planning of proximal humeral fracture ORIF and during tuberosity reduction and fixation during hemiarthroplasty for fracture. We hypothesize that it is feasible to reconstruct the original anatomy of the proximal humerus by using 3-D computer modeling of proximal humerus fractures with high reliability based on interobserver and intraobserver review.

METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, we reviewed the medical records of consecutive patients with a diagnosis of proximal humeral fracture and the treatment codes for hemiarthroplasty from 2000 to 2013. Inclusion criteria included 3- and 4-part fractures (AO classifications 11-B1, 11-B2, 11-C1, 11-C2). CT scans with insufficient quality to differentiate bone from soft tissue (inadequate signal-to-noise ratio) were excluded from the study. A total of 28 patients with adequate CT scans met the criteria for inclusion in this study.

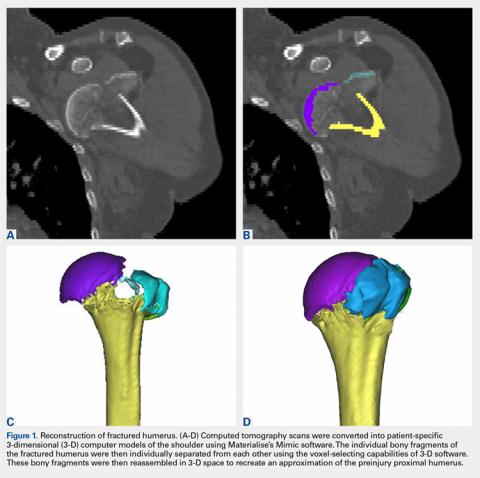

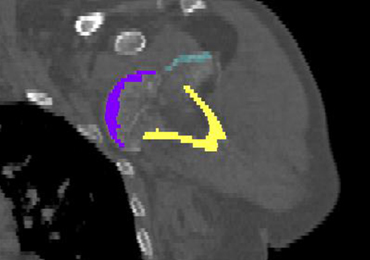

The CT scan protocol included 0.5-mm axial cuts with inclusion of the proximal humerus in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format. These CT scans were converted into patient-specific 3-D computer models of the shoulder using Mimics software (Materialise Inc.). The use of this software to produce anatomically accurate models has previously been verified in a shoulder model.6,7 The tuberosity fragments were then individually separated from each other using the voxel-selecting capabilities of 3-D software and manipulated with translation and rotation for anatomic reduction (Figures 1A-1D, Figure 2).

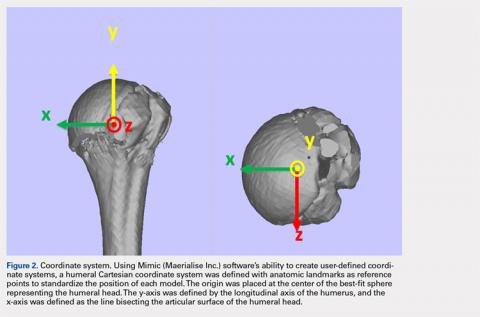

The de-identified anatomically reconstructed shoulder models were then uploaded into Materialise’s Magics rapid prototyping software, and a user-defined humeral Cartesian coordinate system was defined with anatomic landmarks as reference points to standardize the position of each model (Figure 3).8,9

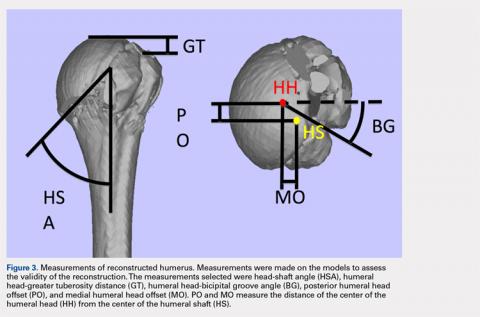

A series of measurements were made on these models to assess the validity and reliability of the reassembly. The bicipital groove at the anatomic neck was used to measure humeral head version as described by Kummer and colleagues.10 The head-shaft angle, humeral head-greater tuberosity distance, humeral head-bicipital groove angle, and posterior and medial humeral head offset were measured directly on the reconstructed humerus.

Continue to: Two fellowship-trained shoulder...

Two fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons independently reassembled these fracture fragments via computer simulation. Interobserver reliability testing was conducted on these reconstructions by measuring the geometry between the 2 different surgeons’ reconstructions. Intraobserver reliability testing was conducted by 1 surgeon repeating the reconstructions with 4-week intervals between trials and measuring the geometry between the 2 different trials. The average dimensions of the reconstructed proximal humerus fractures were compared with the geometry of normal humeri reported in previously conducted anatomic studies.11,12,13

STATISTICS

The measured dimensions of the 28 reassembled proximal humeri models were averaged across all trials between the 2 fellowship-trained surgeons and compared with the range of normal dimensions of a healthy proximal humerus using the 2 one-sided tests (TOST) method for equivalence between 2 means given a range. The interobserver and intraobserver reliabilities were quantified using the interclass correlation coefficient. An excellent correlation was defined as a correlation coefficient >0.81; very good was defined as 0.61 to 0.80; and good was defined as 0.41 to 0.60.

RESULTS

Of the patients studied, 9 (32.1%) were male, and the average age at the time of CT scanning was 72 years. Of the 28 patients with fracture, 18 (64.2%) had 3-part fractures (AO classifications 11-B1, 11-B2), and 10 (35.8%) had 4-part fractures (AO classifications 11-C1, 11-C2). When examining the location of the intertubercular fracture line, we found that 13 (46.4%) fractures went through the bicipital groove. Of the remaining fracture lines, 9 (32.1%) extended into the greater tuberosity and 6 (21.4%) extended into the lesser tuberosity.

All users were able to reconstruct all 28 fractures using this technique. The average measured dimensions fell within the range of dimensions of a normal healthy proximal humerus specified in the literature to within a 95% confidence interval using the TOST for equivalence, in which we compared measured values with ranges reported in the literature (Table).11,12,13

Table. Dimensions of Proximal Humerus Geometry

| Normal Parameters | Average Dimensions From Trials | Dimensions From Literature |

| Head shaft angle | 43.5° ± 1° | 42.5° ± 12.5° |

| Head to greater tuberosity distance | 4.9 mm ± 0.4 mm | 8 mm ± 3.2 mm |

Head to bicipital groove angle (anatomic neck) | 26.4° ± 2° | 27.3° ± 14° |

| Posterior humeral head offset | 1.6 mm ± 0.3 mm | 4 mm ± 6 mm |

| Medial humeral head offset | 4.5 mm ± 0.3 mm | 9 mm ± 5 mm |

The reconstructions of these humerus fractures showed intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.71 to 0.93 in 1 observer and interclass correlation coefficients from 0.82 to 0.98 between 2 different observers (Table).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that it is feasible to reliably and accurately reconstruct the original anatomy of the proximal humerus by using 3-D computer modeling of proximal humerus fractures. Poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures are mostly related to tuberosity malpositioning, resorption, or failure of fixation and resultant dysfunction of the rotator cuff.14,15,16 These studies highlight the importance of accurate tuberosity reduction during surgical care of these fractures.

Continue to: The 3-D computer model...

The 3-D computer model reconstruction of 3- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures were reliable and valid. The interclass correlation coefficients showed very good to excellent interobserver and intraobserver reliability for all measurements conducted. The averaged dimensions from all trials fell within the appropriate range of dimensions for a normal healthy humerus reported in the literature, as verified by the TOST method.11,12,13 The 3-D modeling capabilities demonstrated in this study allowed a greater understanding of the fracture patterns present in 3- and 4-part (AO classifications 11-B1, 11-B2, 11-C1, 11-C2) humerus fractures.

Overreduction of greater tuberosity to create cortical overlap with the lateral shaft may be used to promote bony union. As a result of this distalization, there may be extra strains placed on the rotator cuff, making the patient more prone to rotator cuff tear, as well as improperly balancing the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder. Poor clinical outcomes in hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures have been correlated with a greater tuberosity placed distal relative to the humeral head by 1 cm in a study2 and by 2 cm in another.3

This study has several limitations. The first is the assumption that our injured patients had preinjury proximal humerus geometry within the range of normal dimensions of a healthy humerus. Unfortunately, because we were unable to obtain CT scans of the contralateral shoulder, we had to use standard proximal humerus geometry as the control. Another limitation, inherent in the technique, is that only cortical and dense trabecular bone was modeled, so that comminuted or osteoporotic bone was not well modeled. This study did not correlate the findings from these models with clinical outcomes. A prospective study is needed to evaluate the impact of this 3-D modeling on fracture reductions and clinical outcomes.