User login

A Nervous Recipient of a “Tongue Lashing”

Self-injurious behaviors are common and can be either volitional or unintentional. Often people who perform these behaviors receive “tongue lashings” from family, friends, and loved ones. We recently treated a patient whose lesion in the oral cavity was thought to be caused by some form of self-injury, though the prognosis clearly depended on the true culprit. It is important for clinicians to identify the cause of the injury when encountering patients with oral cavity lesions.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white male with a medical history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, polysubstance abuse, and recently diagnosed temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome was seen in outpatient primary care for a bleeding lesion in his mouth for the past 3 weeks. The lesion was under the surface of his right tongue. He first noted the lesion after he had burned himself tasting some homemade rice pudding while under the influence of marijuana. The next day, an impression was taken of his mouth by a dental assistant who was fitting him for an oral appliance for his TMJ syndrome; according to his history, she did not perform a visual inspection of his mouth nor could he recall his last dental examination. He had neither lost weight nor experienced dysphagia. He was not taking any prescribed medications, had an 8 pack-year history of smoking cigarettes, and had smoked crack cocaine intermittently for several years. The also patient had chewed one-half tin per day of chewing tobacco for 5 years, though he had quit 7 years before presentation. He was consuming 6 alcoholic drinks daily and had no history of chewing betel nuts.

On physical examination, the patient seemed extremely anxious, but his vital signs were unremarkable. The nasal dorsum was straight, and the nares were widely patent. There were no suspicious cutaneous lesions noted of the face, head, trunk, or extremities. The salivary glands were soft and showed no lesions or masses within the parotid or submandibular glands bilaterally. There was no obvious obstruction of Stenson or Wharton ducts bilaterally. He had normal lips and oral competence. The dentition was noted to be fair.

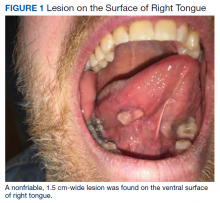

A nonfriable, 1.5 cm-wide lesion was found on the ventral surface of the right tongue (Figure 1). The tongue was mobile. The mouth floor was soft and without evidence of masses or lesions. The tonsils, tonsillar pillars, palate, and base of tongue did not show any concerning lesions or masses. The neck revealed a nonenlarged thyroid and no lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Diagnosis

Given his risk factors of alcohol use disorder and a history of both inhaled and chewing tobacco, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was considered. The differential diagnosis also included pyogenic granuloma, mucocele, sublingual fibroma, and metastasis to the oral soft tissue. Due to its implications with respect to morbidity and mortality, we thought it necessary to rule out SCC of the oral cavity. SCC comprises more than 90% of oral malignancies, and tobacco-related products, alcohol, and human papilloma virus are well-established risk factors.1

Pyogenic granuloma, also known as eruptive hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma, is a relatively common benign lesion of the skin and mucosal surfaces that often presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging papule or nodule that is extremely friable.2 Interestingly, pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer, since it is neither infectious in origin nor granulomatous when visualized under the microscope and is thought to arise from an exuberant tissue response to localized irritation or trauma. An individual lesion can range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters and generally reaches its maximum size within a matter of weeks; they often arise at sites of minor trauma.3 While the pathogenesis of pyogenic granuloma has not been clearly established, it seems to be related to an imbalance of angiogenesis secondary to overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.4 While they can occur at any age, pyogenic granulomas are frequently seen in pediatric patients and during pregnancy.

A fibroma, also known as an irritation fibroma, is one of the more common fibrous tumorlike growths and is often caused by trauma or irritation. It usually presents as a smooth-surfaced, painless solid lesion, though it can be nodular and histopathologically shows collagen and connective tissue.5 While fibromas can occur anywhere in the oral cavity, they commonly arise on the buccal mucosa along the plane of occlusion between the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Mucoceles are the most common benign lesions in the mouth and are commonly found on the lower lip and are mucus-filled cavities, arising from the accumulation of mucus from trauma or lip-biting and alteration of minor salivary glands.6 Our patient’s rapid evolution and history of trauma were consistent with a mucocele. Although the lower lip is the most common site of involvement, mucoceles also occur on the tongue, cheek, palate, and mouth floor.Metastases to the oral cavity are rare and comprise only 1% of all oral cavity malignancies.7 Although most commonly seen in the jaw, nearly one-third of oral cavity metastases are in the soft tissue.8 They generally occur late in the course of disease, and the time between appearance and death is usually short.8 Our patient’s lack of known primary malignancy and lack of weight loss rendered this diagnosis unlikely.

Other possibilities include peripheral giant cell granuloma, a reactive hyperplastic lesion of the oral cavity originating from the periosteum or periodontal membrane following local irritation or chronic trauma,9 and peripheral ossifying fibroma, a reactive soft tissue growth usually seen on the interdental papilla.10

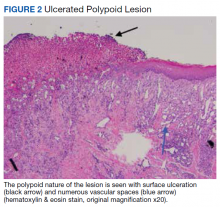

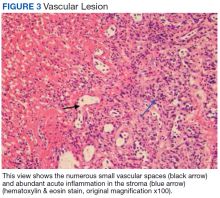

Surgical excision was performed and revealed reactive epidermal hyperplasia, ulceration, granulation tissue formation, and marked inflammation with reactive changes. There was no evidence of malignancy and was interpreted as consistent with pyogenic granuloma (Figures 2 and 3) likely due to the trauma from the thermal burn or poor dentition.

Management

The patient was relieved to be informed of the diagnosis of an unusual presentation of pyogenic granuloma with no evidence of cancer. Current treatment strategies for pyogenic granuloma include surgical excision, shave excision with cautery, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, carbon dioxide or pulsed dye laser, as well as expectant management. However, recurrence after initial treatment can occur, with lower recurrence rates occurring with surgical excision.11

Although we wouldn’t state that we gave the patient a “tongue-lashing,” we strongly advised him that he return to his dentist and abstain from tobacco products, alcohol, illicit drugs, and taste-testing scalding food directly from the pot.

1. Khot KP, Deshmane S, Choudhari S. Human papilloma virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma-the enigma unraveled. Clin J Dent Res. 2016;19(1):17-23.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Neoplasms of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1627-1901.

3. Tatusov M, Reddy S, Federman DG. Pyogenic granuloma: yet another motorcycle peril. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(6):124-126.

4. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):701-709.

5. Krishnan V, Shunmugavelu K. A clinical challenging situation of intra oral fibroma mimicking pyogenic granuloma. J Pan African Med. 2015;22(1):263.

6. Nallasivam KU, Sudha BR. Oral mucocele: review of literature and a case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 2):S731-S733.

7. Zachariades N. Neoplasms metastatic to the mouth, jaws, and surrounding tissues. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(6):283-290.

8. Irani S. Metastasis to the oral soft tissues: a review of 412 cases. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(5):393-401.

9. Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Jafari S, Eslami M. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: a review of 123 cases. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2009;6(1):47-50.

10. Poonacha KS, Shigli AL, Shirol D. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: a clinical report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1(1):54-56.

11. Gilmore A, Kelsberg G, Safranek G. Clinical inquiries. What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(1):40-42.

Self-injurious behaviors are common and can be either volitional or unintentional. Often people who perform these behaviors receive “tongue lashings” from family, friends, and loved ones. We recently treated a patient whose lesion in the oral cavity was thought to be caused by some form of self-injury, though the prognosis clearly depended on the true culprit. It is important for clinicians to identify the cause of the injury when encountering patients with oral cavity lesions.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white male with a medical history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, polysubstance abuse, and recently diagnosed temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome was seen in outpatient primary care for a bleeding lesion in his mouth for the past 3 weeks. The lesion was under the surface of his right tongue. He first noted the lesion after he had burned himself tasting some homemade rice pudding while under the influence of marijuana. The next day, an impression was taken of his mouth by a dental assistant who was fitting him for an oral appliance for his TMJ syndrome; according to his history, she did not perform a visual inspection of his mouth nor could he recall his last dental examination. He had neither lost weight nor experienced dysphagia. He was not taking any prescribed medications, had an 8 pack-year history of smoking cigarettes, and had smoked crack cocaine intermittently for several years. The also patient had chewed one-half tin per day of chewing tobacco for 5 years, though he had quit 7 years before presentation. He was consuming 6 alcoholic drinks daily and had no history of chewing betel nuts.

On physical examination, the patient seemed extremely anxious, but his vital signs were unremarkable. The nasal dorsum was straight, and the nares were widely patent. There were no suspicious cutaneous lesions noted of the face, head, trunk, or extremities. The salivary glands were soft and showed no lesions or masses within the parotid or submandibular glands bilaterally. There was no obvious obstruction of Stenson or Wharton ducts bilaterally. He had normal lips and oral competence. The dentition was noted to be fair.

A nonfriable, 1.5 cm-wide lesion was found on the ventral surface of the right tongue (Figure 1). The tongue was mobile. The mouth floor was soft and without evidence of masses or lesions. The tonsils, tonsillar pillars, palate, and base of tongue did not show any concerning lesions or masses. The neck revealed a nonenlarged thyroid and no lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Diagnosis

Given his risk factors of alcohol use disorder and a history of both inhaled and chewing tobacco, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was considered. The differential diagnosis also included pyogenic granuloma, mucocele, sublingual fibroma, and metastasis to the oral soft tissue. Due to its implications with respect to morbidity and mortality, we thought it necessary to rule out SCC of the oral cavity. SCC comprises more than 90% of oral malignancies, and tobacco-related products, alcohol, and human papilloma virus are well-established risk factors.1

Pyogenic granuloma, also known as eruptive hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma, is a relatively common benign lesion of the skin and mucosal surfaces that often presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging papule or nodule that is extremely friable.2 Interestingly, pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer, since it is neither infectious in origin nor granulomatous when visualized under the microscope and is thought to arise from an exuberant tissue response to localized irritation or trauma. An individual lesion can range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters and generally reaches its maximum size within a matter of weeks; they often arise at sites of minor trauma.3 While the pathogenesis of pyogenic granuloma has not been clearly established, it seems to be related to an imbalance of angiogenesis secondary to overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.4 While they can occur at any age, pyogenic granulomas are frequently seen in pediatric patients and during pregnancy.

A fibroma, also known as an irritation fibroma, is one of the more common fibrous tumorlike growths and is often caused by trauma or irritation. It usually presents as a smooth-surfaced, painless solid lesion, though it can be nodular and histopathologically shows collagen and connective tissue.5 While fibromas can occur anywhere in the oral cavity, they commonly arise on the buccal mucosa along the plane of occlusion between the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Mucoceles are the most common benign lesions in the mouth and are commonly found on the lower lip and are mucus-filled cavities, arising from the accumulation of mucus from trauma or lip-biting and alteration of minor salivary glands.6 Our patient’s rapid evolution and history of trauma were consistent with a mucocele. Although the lower lip is the most common site of involvement, mucoceles also occur on the tongue, cheek, palate, and mouth floor.Metastases to the oral cavity are rare and comprise only 1% of all oral cavity malignancies.7 Although most commonly seen in the jaw, nearly one-third of oral cavity metastases are in the soft tissue.8 They generally occur late in the course of disease, and the time between appearance and death is usually short.8 Our patient’s lack of known primary malignancy and lack of weight loss rendered this diagnosis unlikely.

Other possibilities include peripheral giant cell granuloma, a reactive hyperplastic lesion of the oral cavity originating from the periosteum or periodontal membrane following local irritation or chronic trauma,9 and peripheral ossifying fibroma, a reactive soft tissue growth usually seen on the interdental papilla.10

Surgical excision was performed and revealed reactive epidermal hyperplasia, ulceration, granulation tissue formation, and marked inflammation with reactive changes. There was no evidence of malignancy and was interpreted as consistent with pyogenic granuloma (Figures 2 and 3) likely due to the trauma from the thermal burn or poor dentition.

Management

The patient was relieved to be informed of the diagnosis of an unusual presentation of pyogenic granuloma with no evidence of cancer. Current treatment strategies for pyogenic granuloma include surgical excision, shave excision with cautery, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, carbon dioxide or pulsed dye laser, as well as expectant management. However, recurrence after initial treatment can occur, with lower recurrence rates occurring with surgical excision.11

Although we wouldn’t state that we gave the patient a “tongue-lashing,” we strongly advised him that he return to his dentist and abstain from tobacco products, alcohol, illicit drugs, and taste-testing scalding food directly from the pot.

Self-injurious behaviors are common and can be either volitional or unintentional. Often people who perform these behaviors receive “tongue lashings” from family, friends, and loved ones. We recently treated a patient whose lesion in the oral cavity was thought to be caused by some form of self-injury, though the prognosis clearly depended on the true culprit. It is important for clinicians to identify the cause of the injury when encountering patients with oral cavity lesions.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white male with a medical history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, polysubstance abuse, and recently diagnosed temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome was seen in outpatient primary care for a bleeding lesion in his mouth for the past 3 weeks. The lesion was under the surface of his right tongue. He first noted the lesion after he had burned himself tasting some homemade rice pudding while under the influence of marijuana. The next day, an impression was taken of his mouth by a dental assistant who was fitting him for an oral appliance for his TMJ syndrome; according to his history, she did not perform a visual inspection of his mouth nor could he recall his last dental examination. He had neither lost weight nor experienced dysphagia. He was not taking any prescribed medications, had an 8 pack-year history of smoking cigarettes, and had smoked crack cocaine intermittently for several years. The also patient had chewed one-half tin per day of chewing tobacco for 5 years, though he had quit 7 years before presentation. He was consuming 6 alcoholic drinks daily and had no history of chewing betel nuts.

On physical examination, the patient seemed extremely anxious, but his vital signs were unremarkable. The nasal dorsum was straight, and the nares were widely patent. There were no suspicious cutaneous lesions noted of the face, head, trunk, or extremities. The salivary glands were soft and showed no lesions or masses within the parotid or submandibular glands bilaterally. There was no obvious obstruction of Stenson or Wharton ducts bilaterally. He had normal lips and oral competence. The dentition was noted to be fair.

A nonfriable, 1.5 cm-wide lesion was found on the ventral surface of the right tongue (Figure 1). The tongue was mobile. The mouth floor was soft and without evidence of masses or lesions. The tonsils, tonsillar pillars, palate, and base of tongue did not show any concerning lesions or masses. The neck revealed a nonenlarged thyroid and no lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Diagnosis

Given his risk factors of alcohol use disorder and a history of both inhaled and chewing tobacco, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was considered. The differential diagnosis also included pyogenic granuloma, mucocele, sublingual fibroma, and metastasis to the oral soft tissue. Due to its implications with respect to morbidity and mortality, we thought it necessary to rule out SCC of the oral cavity. SCC comprises more than 90% of oral malignancies, and tobacco-related products, alcohol, and human papilloma virus are well-established risk factors.1

Pyogenic granuloma, also known as eruptive hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma, is a relatively common benign lesion of the skin and mucosal surfaces that often presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging papule or nodule that is extremely friable.2 Interestingly, pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer, since it is neither infectious in origin nor granulomatous when visualized under the microscope and is thought to arise from an exuberant tissue response to localized irritation or trauma. An individual lesion can range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters and generally reaches its maximum size within a matter of weeks; they often arise at sites of minor trauma.3 While the pathogenesis of pyogenic granuloma has not been clearly established, it seems to be related to an imbalance of angiogenesis secondary to overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.4 While they can occur at any age, pyogenic granulomas are frequently seen in pediatric patients and during pregnancy.

A fibroma, also known as an irritation fibroma, is one of the more common fibrous tumorlike growths and is often caused by trauma or irritation. It usually presents as a smooth-surfaced, painless solid lesion, though it can be nodular and histopathologically shows collagen and connective tissue.5 While fibromas can occur anywhere in the oral cavity, they commonly arise on the buccal mucosa along the plane of occlusion between the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Mucoceles are the most common benign lesions in the mouth and are commonly found on the lower lip and are mucus-filled cavities, arising from the accumulation of mucus from trauma or lip-biting and alteration of minor salivary glands.6 Our patient’s rapid evolution and history of trauma were consistent with a mucocele. Although the lower lip is the most common site of involvement, mucoceles also occur on the tongue, cheek, palate, and mouth floor.Metastases to the oral cavity are rare and comprise only 1% of all oral cavity malignancies.7 Although most commonly seen in the jaw, nearly one-third of oral cavity metastases are in the soft tissue.8 They generally occur late in the course of disease, and the time between appearance and death is usually short.8 Our patient’s lack of known primary malignancy and lack of weight loss rendered this diagnosis unlikely.

Other possibilities include peripheral giant cell granuloma, a reactive hyperplastic lesion of the oral cavity originating from the periosteum or periodontal membrane following local irritation or chronic trauma,9 and peripheral ossifying fibroma, a reactive soft tissue growth usually seen on the interdental papilla.10

Surgical excision was performed and revealed reactive epidermal hyperplasia, ulceration, granulation tissue formation, and marked inflammation with reactive changes. There was no evidence of malignancy and was interpreted as consistent with pyogenic granuloma (Figures 2 and 3) likely due to the trauma from the thermal burn or poor dentition.

Management

The patient was relieved to be informed of the diagnosis of an unusual presentation of pyogenic granuloma with no evidence of cancer. Current treatment strategies for pyogenic granuloma include surgical excision, shave excision with cautery, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, carbon dioxide or pulsed dye laser, as well as expectant management. However, recurrence after initial treatment can occur, with lower recurrence rates occurring with surgical excision.11

Although we wouldn’t state that we gave the patient a “tongue-lashing,” we strongly advised him that he return to his dentist and abstain from tobacco products, alcohol, illicit drugs, and taste-testing scalding food directly from the pot.

1. Khot KP, Deshmane S, Choudhari S. Human papilloma virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma-the enigma unraveled. Clin J Dent Res. 2016;19(1):17-23.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Neoplasms of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1627-1901.

3. Tatusov M, Reddy S, Federman DG. Pyogenic granuloma: yet another motorcycle peril. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(6):124-126.

4. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):701-709.

5. Krishnan V, Shunmugavelu K. A clinical challenging situation of intra oral fibroma mimicking pyogenic granuloma. J Pan African Med. 2015;22(1):263.

6. Nallasivam KU, Sudha BR. Oral mucocele: review of literature and a case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 2):S731-S733.

7. Zachariades N. Neoplasms metastatic to the mouth, jaws, and surrounding tissues. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(6):283-290.

8. Irani S. Metastasis to the oral soft tissues: a review of 412 cases. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(5):393-401.

9. Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Jafari S, Eslami M. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: a review of 123 cases. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2009;6(1):47-50.

10. Poonacha KS, Shigli AL, Shirol D. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: a clinical report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1(1):54-56.

11. Gilmore A, Kelsberg G, Safranek G. Clinical inquiries. What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(1):40-42.

1. Khot KP, Deshmane S, Choudhari S. Human papilloma virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma-the enigma unraveled. Clin J Dent Res. 2016;19(1):17-23.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Neoplasms of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1627-1901.

3. Tatusov M, Reddy S, Federman DG. Pyogenic granuloma: yet another motorcycle peril. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(6):124-126.

4. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):701-709.

5. Krishnan V, Shunmugavelu K. A clinical challenging situation of intra oral fibroma mimicking pyogenic granuloma. J Pan African Med. 2015;22(1):263.

6. Nallasivam KU, Sudha BR. Oral mucocele: review of literature and a case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 2):S731-S733.

7. Zachariades N. Neoplasms metastatic to the mouth, jaws, and surrounding tissues. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(6):283-290.

8. Irani S. Metastasis to the oral soft tissues: a review of 412 cases. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(5):393-401.

9. Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Jafari S, Eslami M. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: a review of 123 cases. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2009;6(1):47-50.

10. Poonacha KS, Shigli AL, Shirol D. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: a clinical report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1(1):54-56.

11. Gilmore A, Kelsberg G, Safranek G. Clinical inquiries. What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(1):40-42.

The Personal Health Inventory: Current Use, Perceived Barriers, and Benefits

To better meet the needs and values of patients, the VA has been promulgating a paradigm shift away from the disease-focused model toward a whole health, patient-centered focus.1 To achieve this goal, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation has advocated the use of the personal health inventory (PHI). This inventory asks patients to mindfully assess why their health is important to them and to determine where they feel they are and where they want to be with respect to 8 areas of self-care (working the body, physical and emotional surroundings, personal development, food and drink, sleep, human relationships, spirituality/purpose, and awareness of relationship between mind and body).

Personal health inventory written responses are then discussed with a member of the health care team to develop a proactive, patient-driven health plan unique to that veteran’s circumstances and aspirations.2 The PHI is applicable not only to veterans, but also in primary care and other practices outside the VA to improve shared decision making and produce more effective clinician-patient partnerships.

After national PHI promotion by the VA, the authors observed that there was not widespread adoption of this practice at their institution, despite its introduction and discussion at several primary care staff meetings. The authors surveyed primary care providers (PCPs) at VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) to understand perceived barriers and benefits to the use of PHIs in clinical practice.

Methods

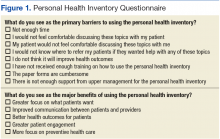

The authors surveyed PCPs at VACHS sites about their current use of the PHI as well as their perceptions of barriers and benefits for future implementation of the PHI in clinical settings. Current use of the PHI was captured in a free response question. The authors assessed comfort with the PHI using a 5-point Likert scale, asking participants how comfortable they would feel explaining the PHI to a patient and or a coworker (1 = very uncomfortable, 5 = very comfortable). Barriers and benefits of future PHI implementation were chosen from preselected lists (Figure 1). Participants also were asked how important they feel it is for VA PCPs to use the PHI (1 = very unimportant, 5 = very important).

Finally, participants were asked whether they plan to use the PHI with their patients and how often (1 = less than once a month, 5 = daily). Participants were initially asked at staff meetings to complete the survey in a paper format. Nonrespondents then were asked to complete the survey electronically. This research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the participating institutions.

Study Population

The survey was delivered to all PCPs in the VACHS, which consisted of 2 main facilities (West Haven and Newington campuses) and 7 community-based outpatient clinics. The VACHS provides care to Connecticut’s eligible veteran population of > 55,000 patients who are enrolled in care. Survey participants included physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. Trainees were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were calculated to assess current use of the PHI, barriers to and benefits of future implementation, and other scaled responses. Chi-square tests were used to compare the responses of participants who were completing the survey online with those completing it on paper for major study outcomes. Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to assess whether responses to certain questions (eg, future plans to use the PHI) were associated with responses to other related questions (eg, importance of VACHS providers pursuing the PHI). Significance was determined as P ≤ .05.

Results

Thirty-eight (53%) of 72 PCPs completed the survey. Thirteen providers completed the survey in the online format and 25 on paper. There was no significant difference between participants who completed the survey online vs paper for each of the major outcomes assessed. Most participants were aged between 40 and 60 years (64%), female (70%), and white (76%), similar to the entire PCP population at VACHS. The majority of participants worked in a hospital-based outpatient primary care setting (58%) (Table).

Current Use of PHI

Of respondents, 84% stated that they had heard of the PHI. Of those, 68% felt very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a patient, with slightly fewer, 64%, very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a coworker. Forty-eight percent stated that they had implemented the PHI in their clinical practices. Examples of current use included “can refer to RN to complete a true PHI,” “giving blank PHI to patients to fill out and bring back/mail,” and “occasional patient who I am trying to achieve some sort of lifestyle modification or change in behavior.”

PHI Barriers and Benefits

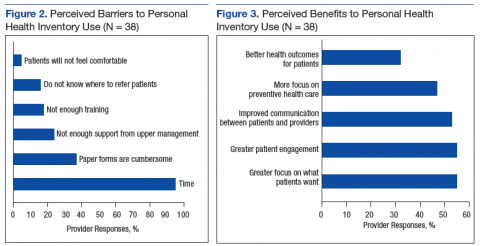

Almost all participants (95%) stated that lack of time was a barrier to using the PHI in their clinical settings (Figure 2). The next most common barriers were cumbersome paper forms (37%) and lack of support from upper management (24%). Very few participants listed discomfort as a reason for not discussing the PHI with patients (5%).

Respondents were divided evenly when identifying the benefits of the PHI. The top 3 selections were greater focus on what patients want (55%), greater patient engagement (55%), and improved patient/provider communication (53%) (Figure 3).

PHI Importance and Future Use

The majority of participants (71%) stated that it was very or somewhat important for VA PCPs to pursue the PHI. However, only 45% planned to use the PHI with their patients. Respondents who said they had implemented the PHI in the past were not more likely than others to state that pursuing the PHI was very important (P = .81). However, respondents who stated that it was very important to pursue the PHI were significantly more likely to plan to implement the PHI (P = .04). Of those planning on its use, the frequency of expected use varied from 31% planning to use the PHI daily with patients to 25% expecting to use it less than once a month.

Discussion

The traditional model of care has been fraught with problems. For example, patients are frequently nonadherent to medical therapies and lifestyle recommendations.3-6 Clearly, changes need to be made. To improve health care outcomes by delivering more patient-centered care, the VA initiated the PHI.7

Although nearly three-fourths of the respondents believed that the PHI was an important tool that the VA should pursue, more than half of all respondents did not intend to use it. Of those planning on using it, a large proportion planned on using it infrequently.

The authors found that despite PCP knowledge of PHI and its acceptance as a tool to focus more on what patients want to accomplish, to enhance patient engagement, and to improve communication between patients and providers, time constraints were a universal barrier to implementation, followed by cumbersome paper forms, and not enough perceived support from local upper management.

Measures to decrease PCP time investment and involvement with paper forms, such as having the patient complete the PHI outside of an office visit with a PCP, either at home, with the assistance of a team member with less training than a PCP, or electronically could help address an identified barrier. Further, if the PHI is to be more broadly adopted, support of local upper management should be enlisted to vociferously advocate its use, thus it will be deemed more essential to enhance care and introduce an organizational system for its effective implementation.

Interestingly, only about one-third of respondents believed that the use of the PHI would lead to better health outcomes for patients. Future studies should address whether the use of the PHI improves surrogate goals, such as cholesterol levels, blood pressures, hemoglobin A1c, or medication adherence as well as harder outcomes, such as risk of cardiovascular outcomes, diabetic complications, and mortality.

Limitations

The questionnaire was used at only 1 health care system within the VA. Whether it could be generalizable to PCPs with other baseline demographic information, non-VA facilities, or even other VA facilities, is not known. Since this survey was administered to PCPs, the authors also do not know the impact of implementing the PHI in specialty settings.

Conclusion

Although the concept of the PHI is favored by the majority of PCPs within VACHS, significant barriers, the most common being time constraints, need to be overcome before it is widely adopted. Implementation of novel collaborative systems of PHI administration may be needed.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.VA patient centered care. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/about.asp. Updated March 3, 2016. Accessed March 30, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. MyStory: personal health inventory. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal-health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Published October 7, 2013. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, Dimatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):189-199.

4. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD000011.

5. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44.

6. Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785-795. 7. Simmons LA, Drake CD, Gaudet TW, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning in primary care settings. Fed Pract. 2016;33(1):27-34.

To better meet the needs and values of patients, the VA has been promulgating a paradigm shift away from the disease-focused model toward a whole health, patient-centered focus.1 To achieve this goal, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation has advocated the use of the personal health inventory (PHI). This inventory asks patients to mindfully assess why their health is important to them and to determine where they feel they are and where they want to be with respect to 8 areas of self-care (working the body, physical and emotional surroundings, personal development, food and drink, sleep, human relationships, spirituality/purpose, and awareness of relationship between mind and body).

Personal health inventory written responses are then discussed with a member of the health care team to develop a proactive, patient-driven health plan unique to that veteran’s circumstances and aspirations.2 The PHI is applicable not only to veterans, but also in primary care and other practices outside the VA to improve shared decision making and produce more effective clinician-patient partnerships.

After national PHI promotion by the VA, the authors observed that there was not widespread adoption of this practice at their institution, despite its introduction and discussion at several primary care staff meetings. The authors surveyed primary care providers (PCPs) at VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) to understand perceived barriers and benefits to the use of PHIs in clinical practice.

Methods

The authors surveyed PCPs at VACHS sites about their current use of the PHI as well as their perceptions of barriers and benefits for future implementation of the PHI in clinical settings. Current use of the PHI was captured in a free response question. The authors assessed comfort with the PHI using a 5-point Likert scale, asking participants how comfortable they would feel explaining the PHI to a patient and or a coworker (1 = very uncomfortable, 5 = very comfortable). Barriers and benefits of future PHI implementation were chosen from preselected lists (Figure 1). Participants also were asked how important they feel it is for VA PCPs to use the PHI (1 = very unimportant, 5 = very important).

Finally, participants were asked whether they plan to use the PHI with their patients and how often (1 = less than once a month, 5 = daily). Participants were initially asked at staff meetings to complete the survey in a paper format. Nonrespondents then were asked to complete the survey electronically. This research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the participating institutions.

Study Population

The survey was delivered to all PCPs in the VACHS, which consisted of 2 main facilities (West Haven and Newington campuses) and 7 community-based outpatient clinics. The VACHS provides care to Connecticut’s eligible veteran population of > 55,000 patients who are enrolled in care. Survey participants included physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. Trainees were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were calculated to assess current use of the PHI, barriers to and benefits of future implementation, and other scaled responses. Chi-square tests were used to compare the responses of participants who were completing the survey online with those completing it on paper for major study outcomes. Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to assess whether responses to certain questions (eg, future plans to use the PHI) were associated with responses to other related questions (eg, importance of VACHS providers pursuing the PHI). Significance was determined as P ≤ .05.

Results

Thirty-eight (53%) of 72 PCPs completed the survey. Thirteen providers completed the survey in the online format and 25 on paper. There was no significant difference between participants who completed the survey online vs paper for each of the major outcomes assessed. Most participants were aged between 40 and 60 years (64%), female (70%), and white (76%), similar to the entire PCP population at VACHS. The majority of participants worked in a hospital-based outpatient primary care setting (58%) (Table).

Current Use of PHI

Of respondents, 84% stated that they had heard of the PHI. Of those, 68% felt very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a patient, with slightly fewer, 64%, very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a coworker. Forty-eight percent stated that they had implemented the PHI in their clinical practices. Examples of current use included “can refer to RN to complete a true PHI,” “giving blank PHI to patients to fill out and bring back/mail,” and “occasional patient who I am trying to achieve some sort of lifestyle modification or change in behavior.”

PHI Barriers and Benefits

Almost all participants (95%) stated that lack of time was a barrier to using the PHI in their clinical settings (Figure 2). The next most common barriers were cumbersome paper forms (37%) and lack of support from upper management (24%). Very few participants listed discomfort as a reason for not discussing the PHI with patients (5%).

Respondents were divided evenly when identifying the benefits of the PHI. The top 3 selections were greater focus on what patients want (55%), greater patient engagement (55%), and improved patient/provider communication (53%) (Figure 3).

PHI Importance and Future Use

The majority of participants (71%) stated that it was very or somewhat important for VA PCPs to pursue the PHI. However, only 45% planned to use the PHI with their patients. Respondents who said they had implemented the PHI in the past were not more likely than others to state that pursuing the PHI was very important (P = .81). However, respondents who stated that it was very important to pursue the PHI were significantly more likely to plan to implement the PHI (P = .04). Of those planning on its use, the frequency of expected use varied from 31% planning to use the PHI daily with patients to 25% expecting to use it less than once a month.

Discussion

The traditional model of care has been fraught with problems. For example, patients are frequently nonadherent to medical therapies and lifestyle recommendations.3-6 Clearly, changes need to be made. To improve health care outcomes by delivering more patient-centered care, the VA initiated the PHI.7

Although nearly three-fourths of the respondents believed that the PHI was an important tool that the VA should pursue, more than half of all respondents did not intend to use it. Of those planning on using it, a large proportion planned on using it infrequently.

The authors found that despite PCP knowledge of PHI and its acceptance as a tool to focus more on what patients want to accomplish, to enhance patient engagement, and to improve communication between patients and providers, time constraints were a universal barrier to implementation, followed by cumbersome paper forms, and not enough perceived support from local upper management.

Measures to decrease PCP time investment and involvement with paper forms, such as having the patient complete the PHI outside of an office visit with a PCP, either at home, with the assistance of a team member with less training than a PCP, or electronically could help address an identified barrier. Further, if the PHI is to be more broadly adopted, support of local upper management should be enlisted to vociferously advocate its use, thus it will be deemed more essential to enhance care and introduce an organizational system for its effective implementation.

Interestingly, only about one-third of respondents believed that the use of the PHI would lead to better health outcomes for patients. Future studies should address whether the use of the PHI improves surrogate goals, such as cholesterol levels, blood pressures, hemoglobin A1c, or medication adherence as well as harder outcomes, such as risk of cardiovascular outcomes, diabetic complications, and mortality.

Limitations

The questionnaire was used at only 1 health care system within the VA. Whether it could be generalizable to PCPs with other baseline demographic information, non-VA facilities, or even other VA facilities, is not known. Since this survey was administered to PCPs, the authors also do not know the impact of implementing the PHI in specialty settings.

Conclusion

Although the concept of the PHI is favored by the majority of PCPs within VACHS, significant barriers, the most common being time constraints, need to be overcome before it is widely adopted. Implementation of novel collaborative systems of PHI administration may be needed.

To better meet the needs and values of patients, the VA has been promulgating a paradigm shift away from the disease-focused model toward a whole health, patient-centered focus.1 To achieve this goal, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation has advocated the use of the personal health inventory (PHI). This inventory asks patients to mindfully assess why their health is important to them and to determine where they feel they are and where they want to be with respect to 8 areas of self-care (working the body, physical and emotional surroundings, personal development, food and drink, sleep, human relationships, spirituality/purpose, and awareness of relationship between mind and body).

Personal health inventory written responses are then discussed with a member of the health care team to develop a proactive, patient-driven health plan unique to that veteran’s circumstances and aspirations.2 The PHI is applicable not only to veterans, but also in primary care and other practices outside the VA to improve shared decision making and produce more effective clinician-patient partnerships.

After national PHI promotion by the VA, the authors observed that there was not widespread adoption of this practice at their institution, despite its introduction and discussion at several primary care staff meetings. The authors surveyed primary care providers (PCPs) at VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) to understand perceived barriers and benefits to the use of PHIs in clinical practice.

Methods

The authors surveyed PCPs at VACHS sites about their current use of the PHI as well as their perceptions of barriers and benefits for future implementation of the PHI in clinical settings. Current use of the PHI was captured in a free response question. The authors assessed comfort with the PHI using a 5-point Likert scale, asking participants how comfortable they would feel explaining the PHI to a patient and or a coworker (1 = very uncomfortable, 5 = very comfortable). Barriers and benefits of future PHI implementation were chosen from preselected lists (Figure 1). Participants also were asked how important they feel it is for VA PCPs to use the PHI (1 = very unimportant, 5 = very important).

Finally, participants were asked whether they plan to use the PHI with their patients and how often (1 = less than once a month, 5 = daily). Participants were initially asked at staff meetings to complete the survey in a paper format. Nonrespondents then were asked to complete the survey electronically. This research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the participating institutions.

Study Population

The survey was delivered to all PCPs in the VACHS, which consisted of 2 main facilities (West Haven and Newington campuses) and 7 community-based outpatient clinics. The VACHS provides care to Connecticut’s eligible veteran population of > 55,000 patients who are enrolled in care. Survey participants included physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. Trainees were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were calculated to assess current use of the PHI, barriers to and benefits of future implementation, and other scaled responses. Chi-square tests were used to compare the responses of participants who were completing the survey online with those completing it on paper for major study outcomes. Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to assess whether responses to certain questions (eg, future plans to use the PHI) were associated with responses to other related questions (eg, importance of VACHS providers pursuing the PHI). Significance was determined as P ≤ .05.

Results

Thirty-eight (53%) of 72 PCPs completed the survey. Thirteen providers completed the survey in the online format and 25 on paper. There was no significant difference between participants who completed the survey online vs paper for each of the major outcomes assessed. Most participants were aged between 40 and 60 years (64%), female (70%), and white (76%), similar to the entire PCP population at VACHS. The majority of participants worked in a hospital-based outpatient primary care setting (58%) (Table).

Current Use of PHI

Of respondents, 84% stated that they had heard of the PHI. Of those, 68% felt very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a patient, with slightly fewer, 64%, very or somewhat comfortable explaining the PHI to a coworker. Forty-eight percent stated that they had implemented the PHI in their clinical practices. Examples of current use included “can refer to RN to complete a true PHI,” “giving blank PHI to patients to fill out and bring back/mail,” and “occasional patient who I am trying to achieve some sort of lifestyle modification or change in behavior.”

PHI Barriers and Benefits

Almost all participants (95%) stated that lack of time was a barrier to using the PHI in their clinical settings (Figure 2). The next most common barriers were cumbersome paper forms (37%) and lack of support from upper management (24%). Very few participants listed discomfort as a reason for not discussing the PHI with patients (5%).

Respondents were divided evenly when identifying the benefits of the PHI. The top 3 selections were greater focus on what patients want (55%), greater patient engagement (55%), and improved patient/provider communication (53%) (Figure 3).

PHI Importance and Future Use

The majority of participants (71%) stated that it was very or somewhat important for VA PCPs to pursue the PHI. However, only 45% planned to use the PHI with their patients. Respondents who said they had implemented the PHI in the past were not more likely than others to state that pursuing the PHI was very important (P = .81). However, respondents who stated that it was very important to pursue the PHI were significantly more likely to plan to implement the PHI (P = .04). Of those planning on its use, the frequency of expected use varied from 31% planning to use the PHI daily with patients to 25% expecting to use it less than once a month.

Discussion

The traditional model of care has been fraught with problems. For example, patients are frequently nonadherent to medical therapies and lifestyle recommendations.3-6 Clearly, changes need to be made. To improve health care outcomes by delivering more patient-centered care, the VA initiated the PHI.7

Although nearly three-fourths of the respondents believed that the PHI was an important tool that the VA should pursue, more than half of all respondents did not intend to use it. Of those planning on using it, a large proportion planned on using it infrequently.

The authors found that despite PCP knowledge of PHI and its acceptance as a tool to focus more on what patients want to accomplish, to enhance patient engagement, and to improve communication between patients and providers, time constraints were a universal barrier to implementation, followed by cumbersome paper forms, and not enough perceived support from local upper management.

Measures to decrease PCP time investment and involvement with paper forms, such as having the patient complete the PHI outside of an office visit with a PCP, either at home, with the assistance of a team member with less training than a PCP, or electronically could help address an identified barrier. Further, if the PHI is to be more broadly adopted, support of local upper management should be enlisted to vociferously advocate its use, thus it will be deemed more essential to enhance care and introduce an organizational system for its effective implementation.

Interestingly, only about one-third of respondents believed that the use of the PHI would lead to better health outcomes for patients. Future studies should address whether the use of the PHI improves surrogate goals, such as cholesterol levels, blood pressures, hemoglobin A1c, or medication adherence as well as harder outcomes, such as risk of cardiovascular outcomes, diabetic complications, and mortality.

Limitations

The questionnaire was used at only 1 health care system within the VA. Whether it could be generalizable to PCPs with other baseline demographic information, non-VA facilities, or even other VA facilities, is not known. Since this survey was administered to PCPs, the authors also do not know the impact of implementing the PHI in specialty settings.

Conclusion

Although the concept of the PHI is favored by the majority of PCPs within VACHS, significant barriers, the most common being time constraints, need to be overcome before it is widely adopted. Implementation of novel collaborative systems of PHI administration may be needed.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.VA patient centered care. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/about.asp. Updated March 3, 2016. Accessed March 30, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. MyStory: personal health inventory. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal-health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Published October 7, 2013. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, Dimatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):189-199.

4. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD000011.

5. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44.

6. Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785-795. 7. Simmons LA, Drake CD, Gaudet TW, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning in primary care settings. Fed Pract. 2016;33(1):27-34.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.VA patient centered care. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/about.asp. Updated March 3, 2016. Accessed March 30, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. MyStory: personal health inventory. http://www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal-health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Published October 7, 2013. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, Dimatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):189-199.

4. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD000011.

5. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44.

6. Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785-795. 7. Simmons LA, Drake CD, Gaudet TW, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning in primary care settings. Fed Pract. 2016;33(1):27-34.