User login

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

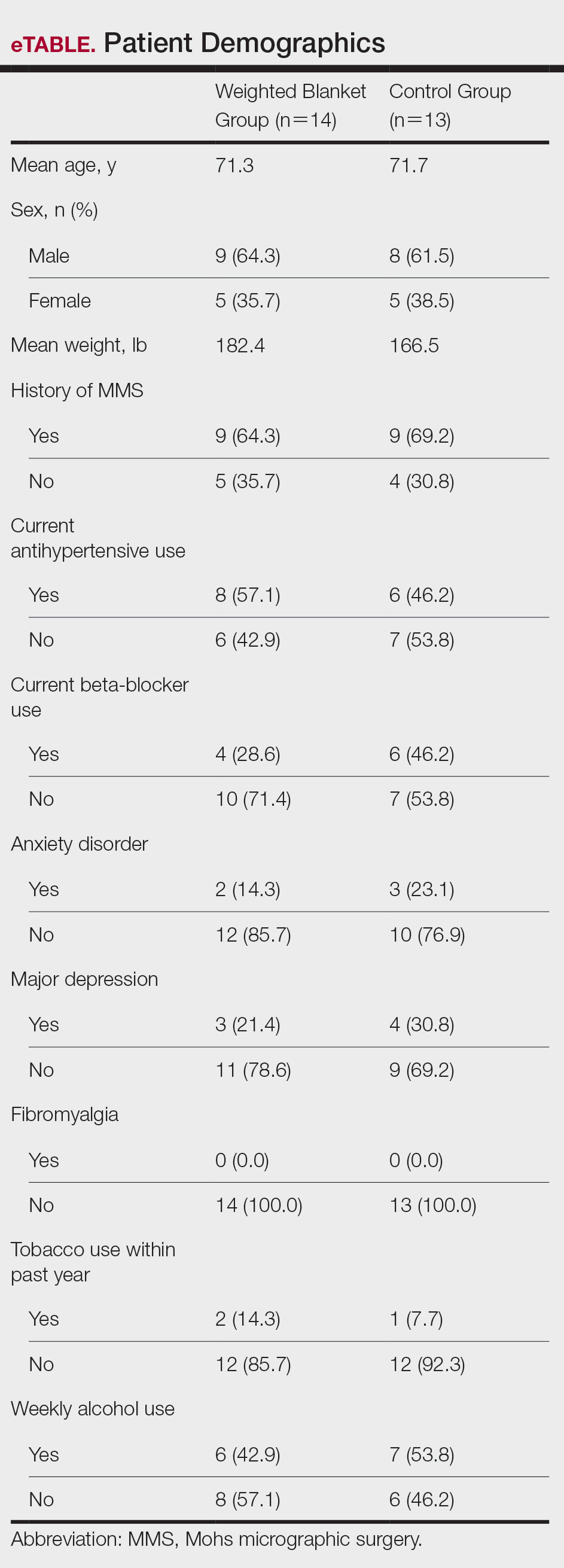

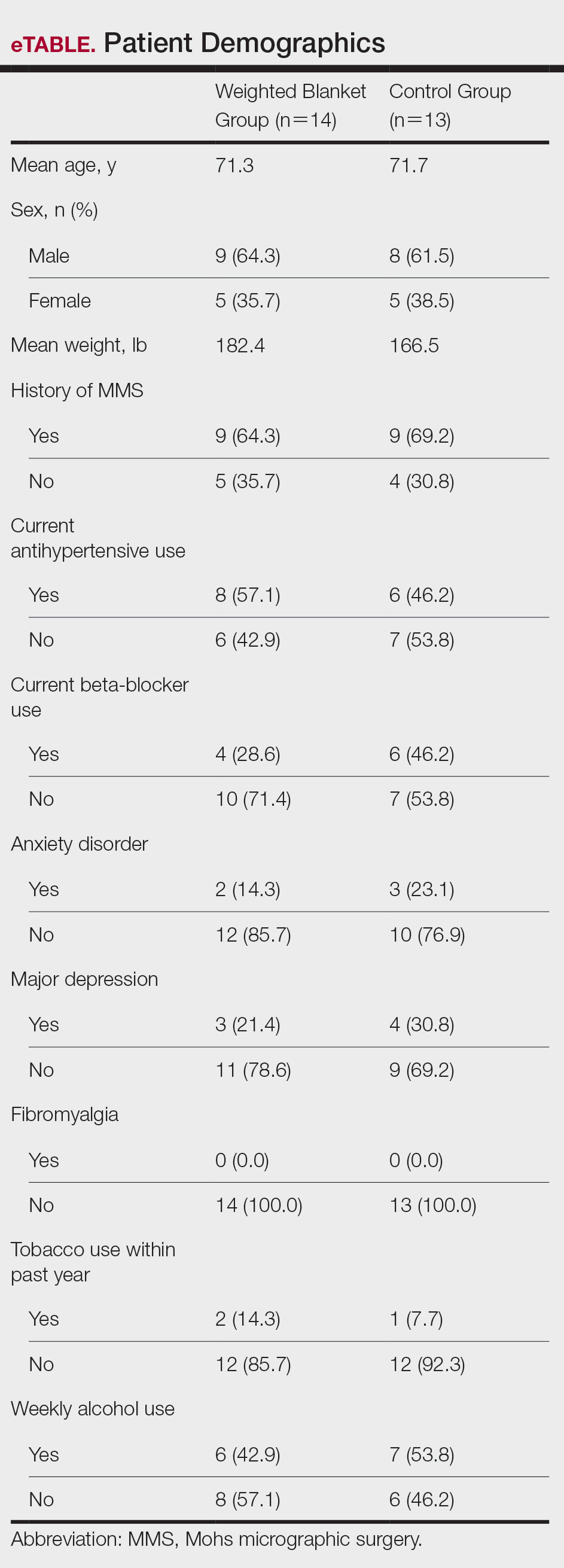

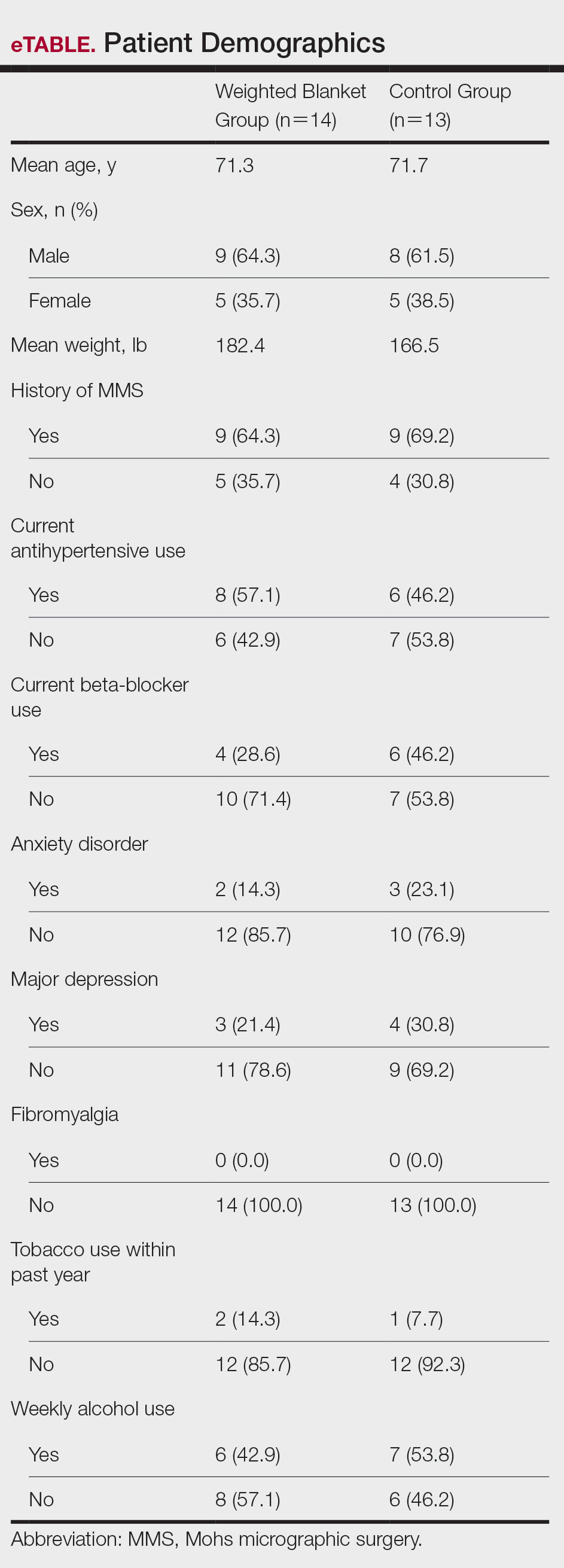

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

PRACTICE POINTS

- Preoperative anxiety in patients during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.

- Using weighted blankets may reduce anxiety in patients undergoing MMS of the head and neck.

Reticulated Brownish Erythema on the Lower Back

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

A 42-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, erythematous, lacelike rash on the lower back of 8 months’ duration that was first noticed by her husband. The patient had a long-standing history of chronic fatigue and lower back pain treated with acetaminophen, diclofenac gel, and heating pads. Physical examination revealed reticulated brownish erythema confined to the lower back. Laboratory findings were unremarkable.