User login

USPSTF makes significant change to Hep C screening recommendation

References

- Hepatitis C questions and answers for health professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Surveillance for Viral Hepatitis–United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Published March 2, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

References

- Hepatitis C questions and answers for health professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Surveillance for Viral Hepatitis–United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Published March 2, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

References

- Hepatitis C questions and answers for health professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Surveillance for Viral Hepatitis–United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Published March 2, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

Screen asymptomatic older adults for cognitive impairment? Not so fast

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Published February 2020. Accessed March 19, 2020.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Published February 2020. Accessed March 19, 2020.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Published February 2020. Accessed March 19, 2020.

ACIP vaccination update

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

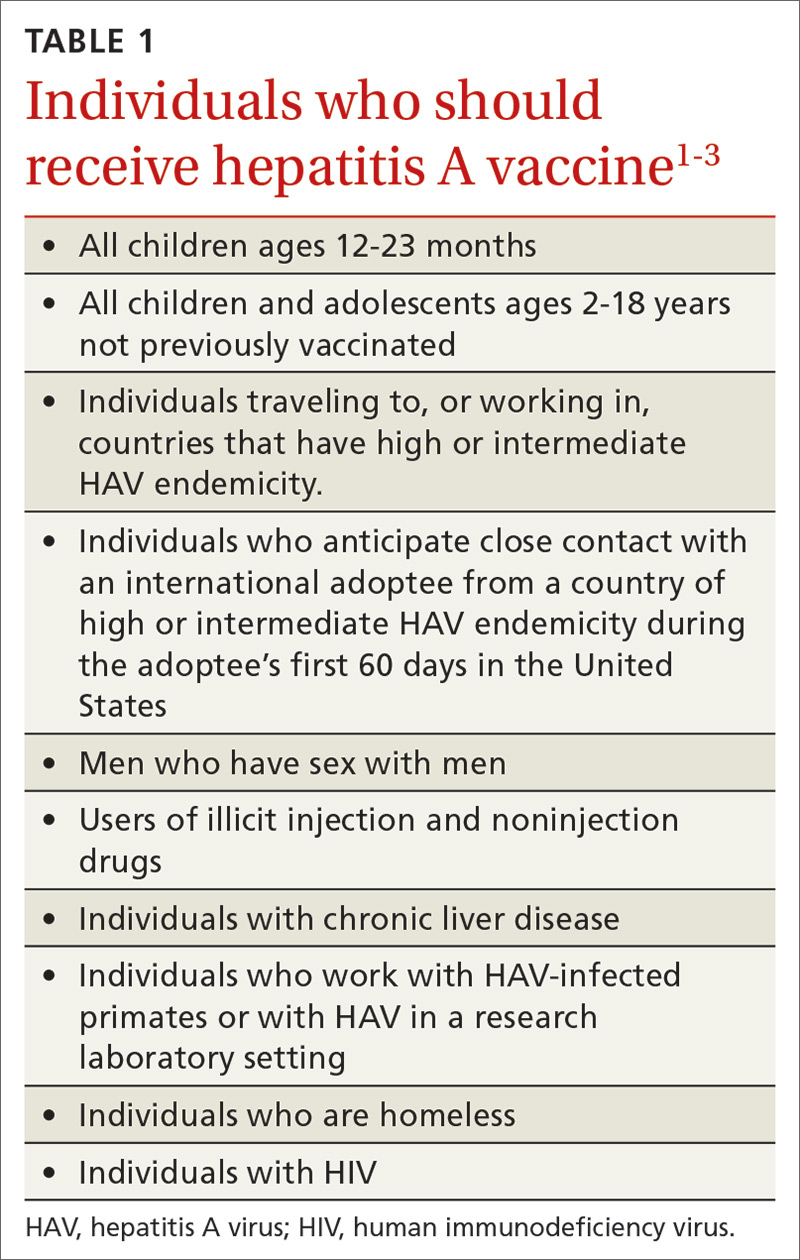

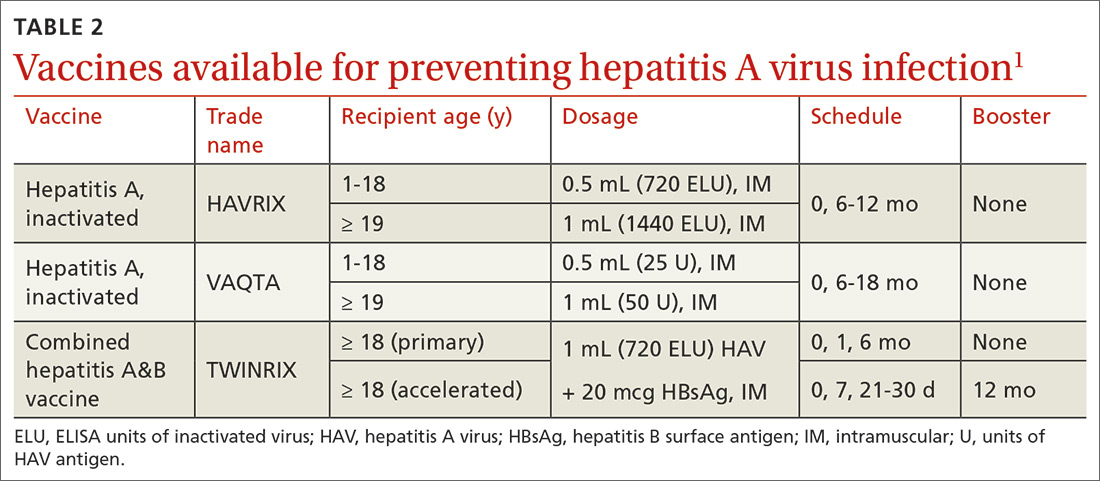

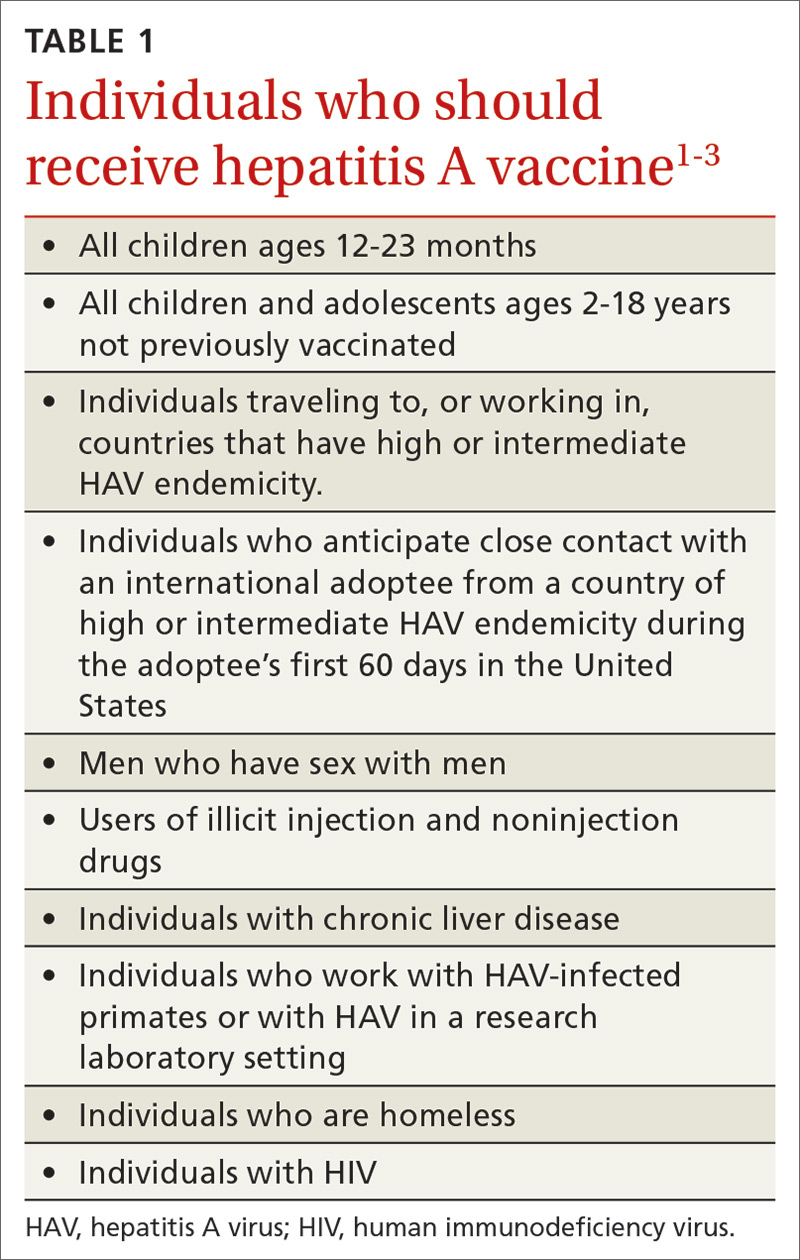

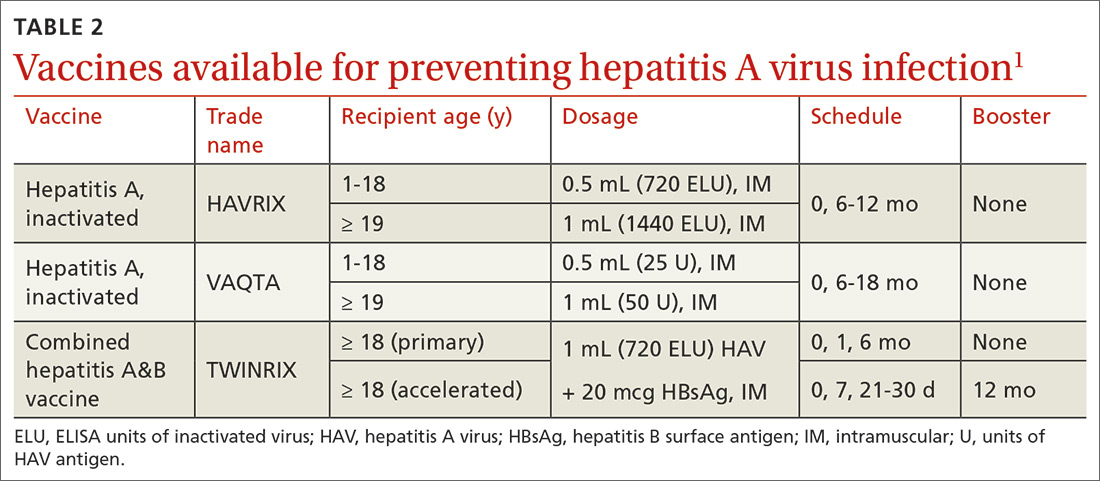

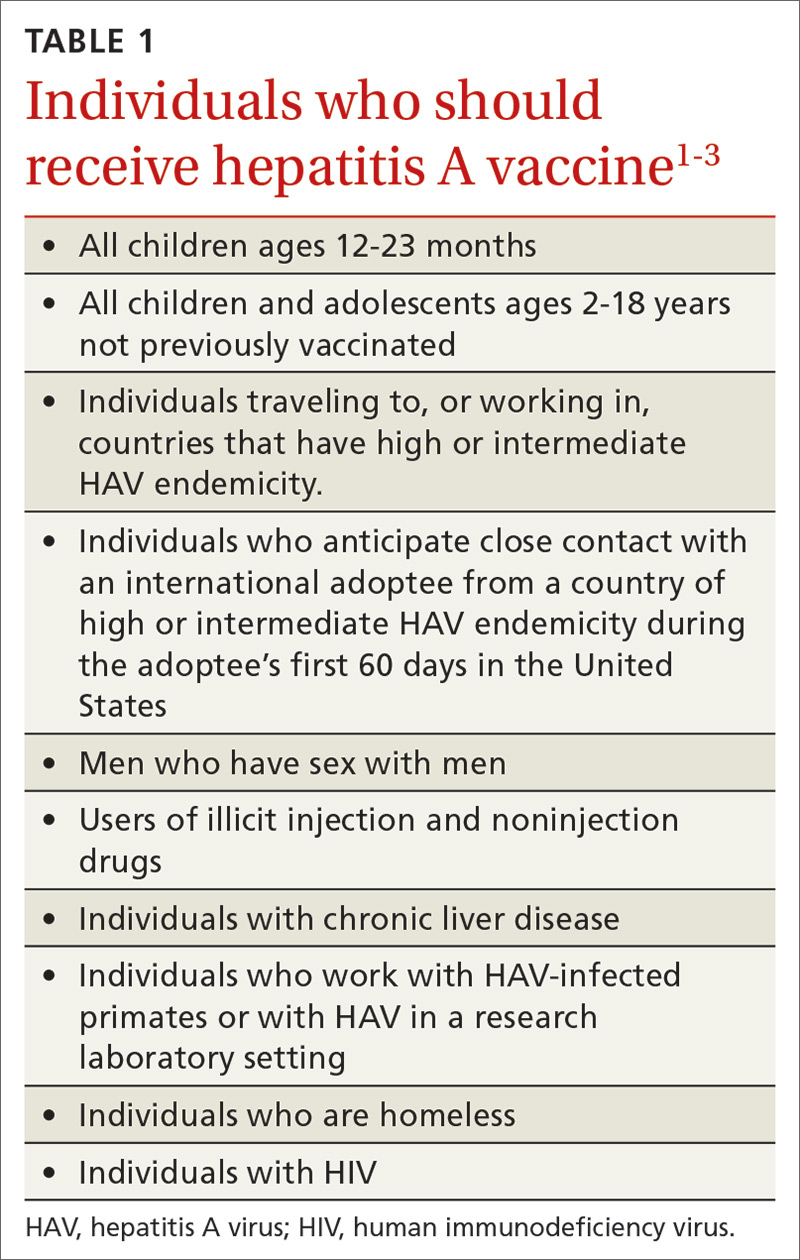

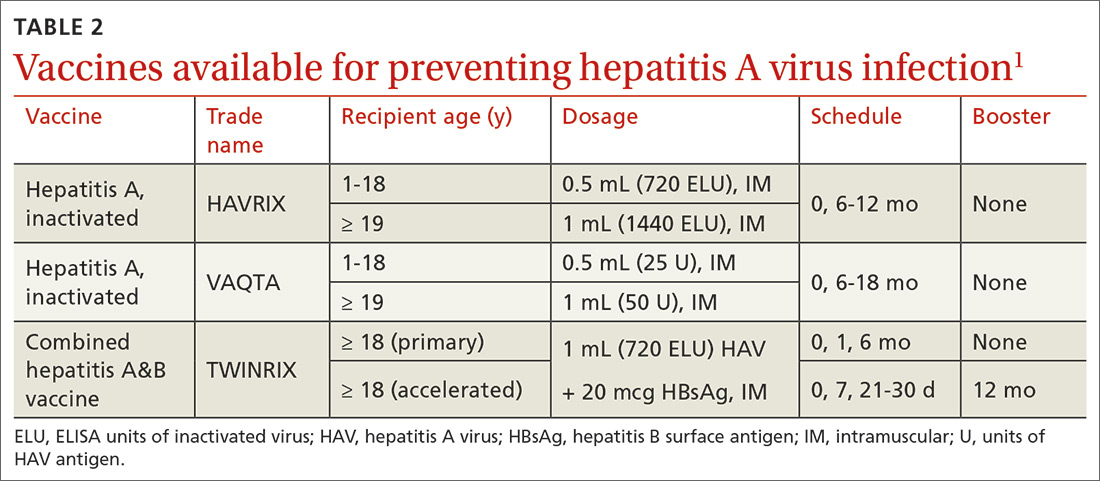

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

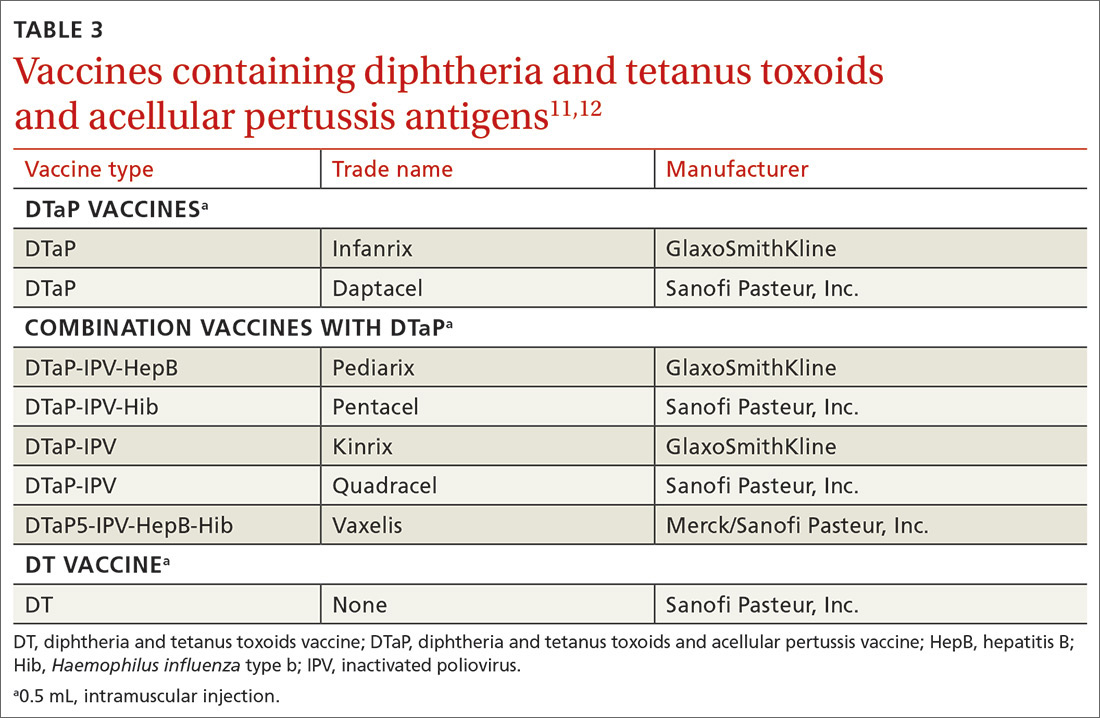

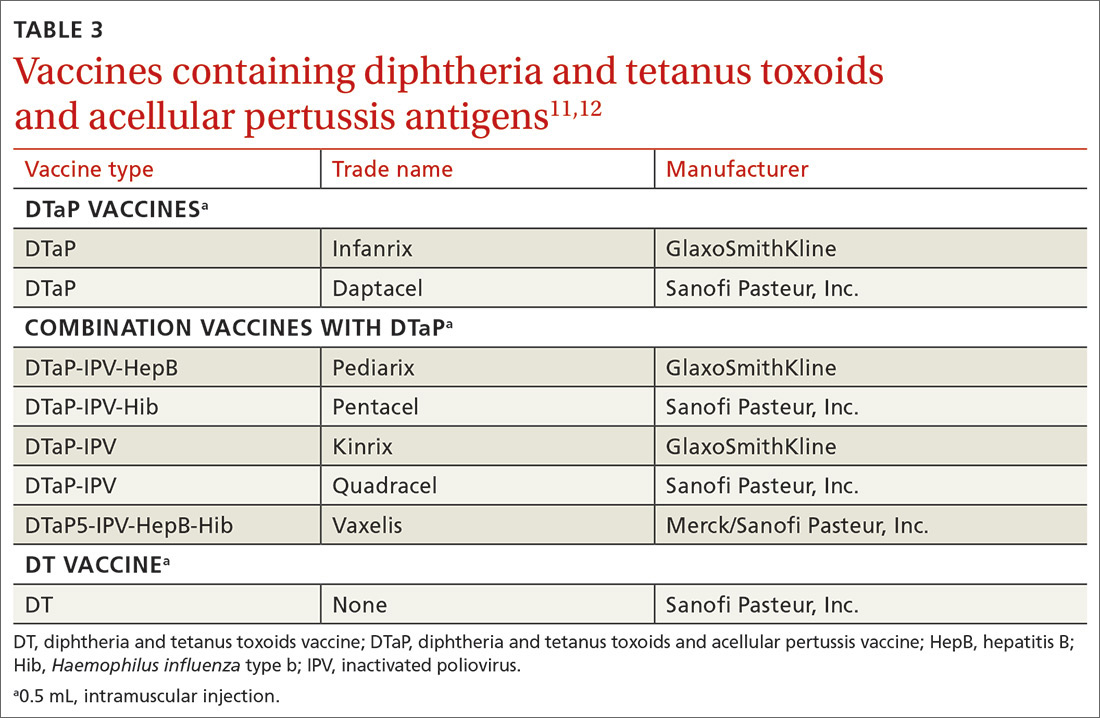

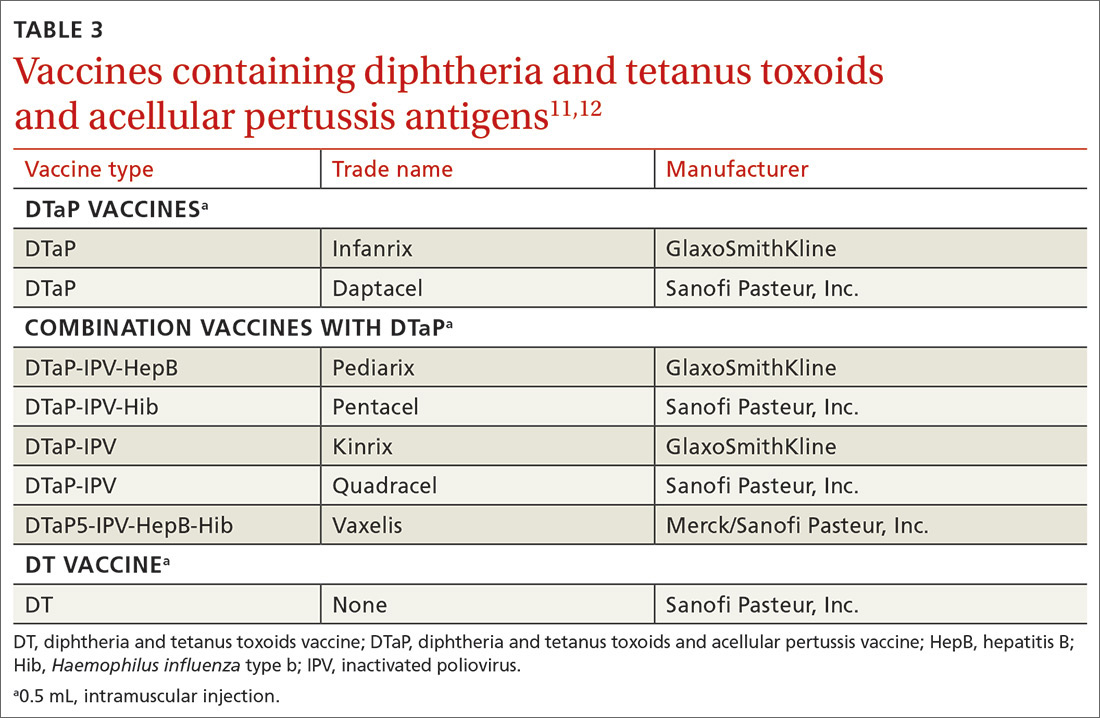

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Coronavirus outbreak: Time to prepare

References

- Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) or Persons Under Investigation for COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Finfection-control.html. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Implementing Home Care of People Not Requiring Hospitalization for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-home-care.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Preventing the Spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Homes and Residential Communities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-prevent-spread.html. Updated February 14, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-in-us.html. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

ALSO, see last month’s audiocast: “Coronavirus outbreak: Putting it into perspective.”

References

- Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) or Persons Under Investigation for COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Finfection-control.html. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Implementing Home Care of People Not Requiring Hospitalization for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-home-care.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Preventing the Spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Homes and Residential Communities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-prevent-spread.html. Updated February 14, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-in-us.html. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

ALSO, see last month’s audiocast: “Coronavirus outbreak: Putting it into perspective.”

References

- Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) or Persons Under Investigation for COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Finfection-control.html. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Implementing Home Care of People Not Requiring Hospitalization for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-home-care.html. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Interim Guidance for Preventing the Spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Homes and Residential Communities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-prevent-spread.html. Updated February 14, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-in-us.html. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2020.

ALSO, see last month’s audiocast: “Coronavirus outbreak: Putting it into perspective.”

Coronavirus outbreak: Putting it into perspective

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Last reviewed February 8, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation as of 10 February 2020. http://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/c88e37cfc43b4ed3baf977d77e4a0667. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus: Evaluating and reporting persons under investigation (PUI). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html Last reviewed February 3, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Last reviewed February 7, 2020. Accessed February 12, 2020.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Last reviewed February 8, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation as of 10 February 2020. http://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/c88e37cfc43b4ed3baf977d77e4a0667. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus: Evaluating and reporting persons under investigation (PUI). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html Last reviewed February 3, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Last reviewed February 7, 2020. Accessed February 12, 2020.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Last reviewed February 8, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation as of 10 February 2020. http://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/c88e37cfc43b4ed3baf977d77e4a0667. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 novel coronavirus: Evaluating and reporting persons under investigation (PUI). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html Last reviewed February 3, 2020. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Last reviewed February 7, 2020. Accessed February 12, 2020.

A quick guide to PrEP: Steps to take & insurance coverage changes to watch for

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2019;24. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. CDC Web Site. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: preexposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Published June 2019. Accessed January 17, 2020.

- Campos-Outcalt D. A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:768-772.

What do the new AGA guidelines recommend for opioid-induced constipation?

References

- Crockett SD, Greer KB, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Medical Management of Opioid-Induced Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:218-226.

- Rao VL, Micic D, Davis AM. Medical management of opioid-induced constipation. JAMA. 2019;322:2241-2242.

- Naldemedine (Symproic) for opioid-induced constipation. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59:196-198.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

References

- Crockett SD, Greer KB, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Medical Management of Opioid-Induced Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:218-226.

- Rao VL, Micic D, Davis AM. Medical management of opioid-induced constipation. JAMA. 2019;322:2241-2242.

- Naldemedine (Symproic) for opioid-induced constipation. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59:196-198.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

References

- Crockett SD, Greer KB, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Medical Management of Opioid-Induced Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:218-226.

- Rao VL, Micic D, Davis AM. Medical management of opioid-induced constipation. JAMA. 2019;322:2241-2242.

- Naldemedine (Symproic) for opioid-induced constipation. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59:196-198.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update

Two pneumococcal vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 [Prevnar 13, Wyeth]) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23 [Pneumovax, Merck]). The recommendations for using these vaccines in adults ages ≥ 19 years are arguably among the most complicated and confusing of all vaccine recommendations made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In June 2019, things got even more complicated with ACIP’s unusual decision to change the previous recommendation on the routine use of PCV13 in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent older adults only after individual clinical decision making. The recommendation for routine use of PPSV23 remains unchanged. This Practice Alert explains the reasoning behind this change and its practical implications.

How we got to where we are now

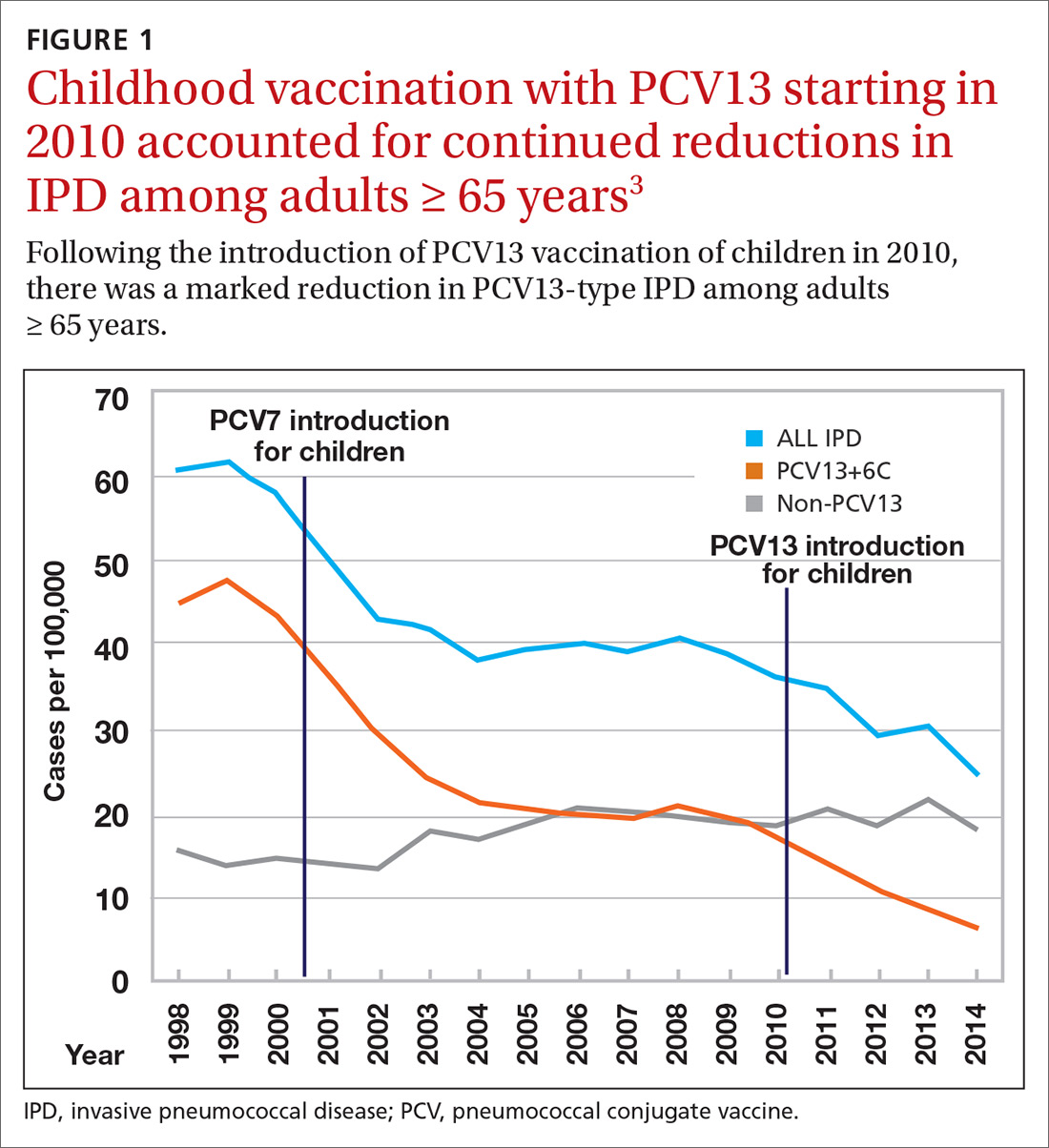

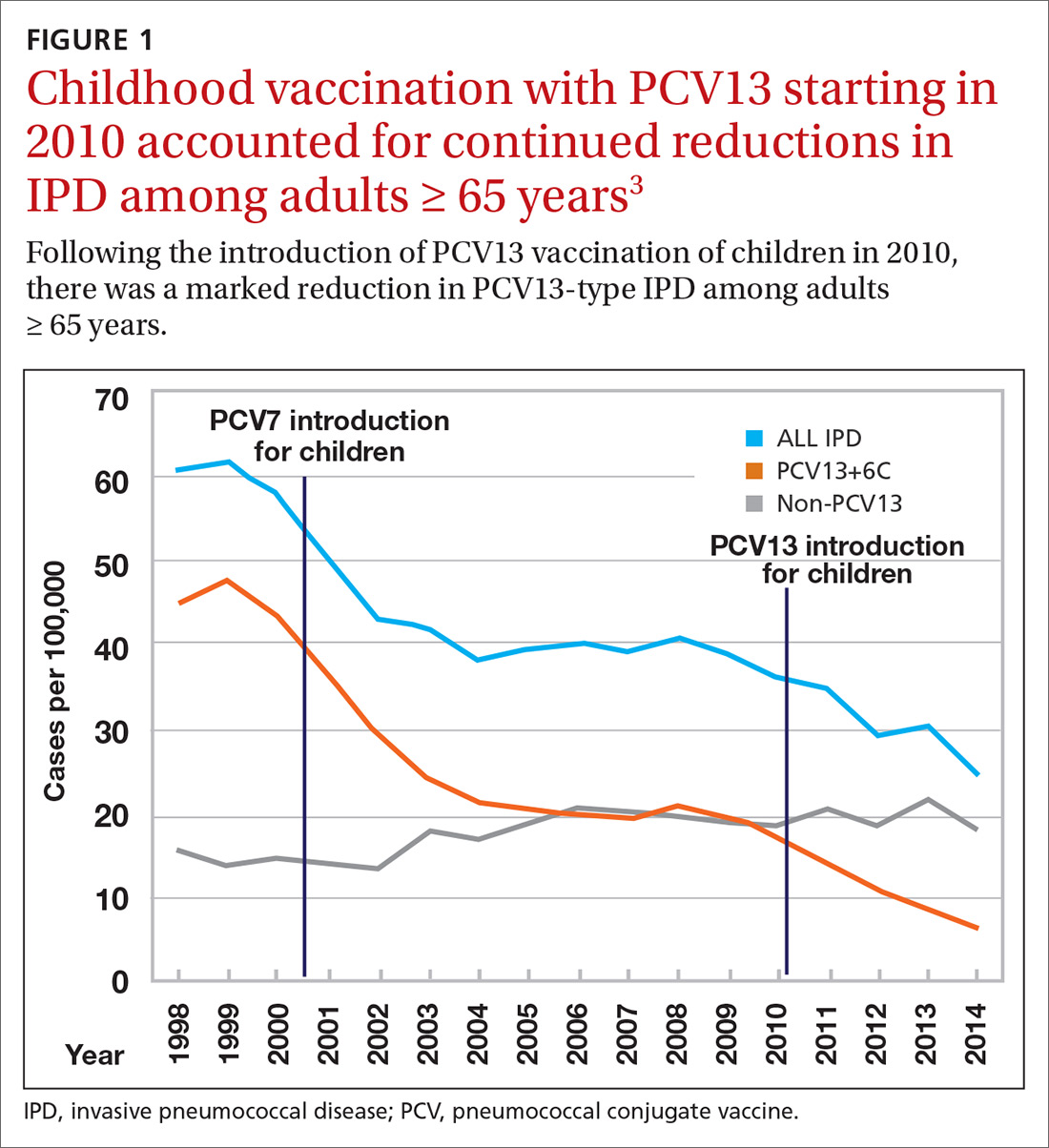

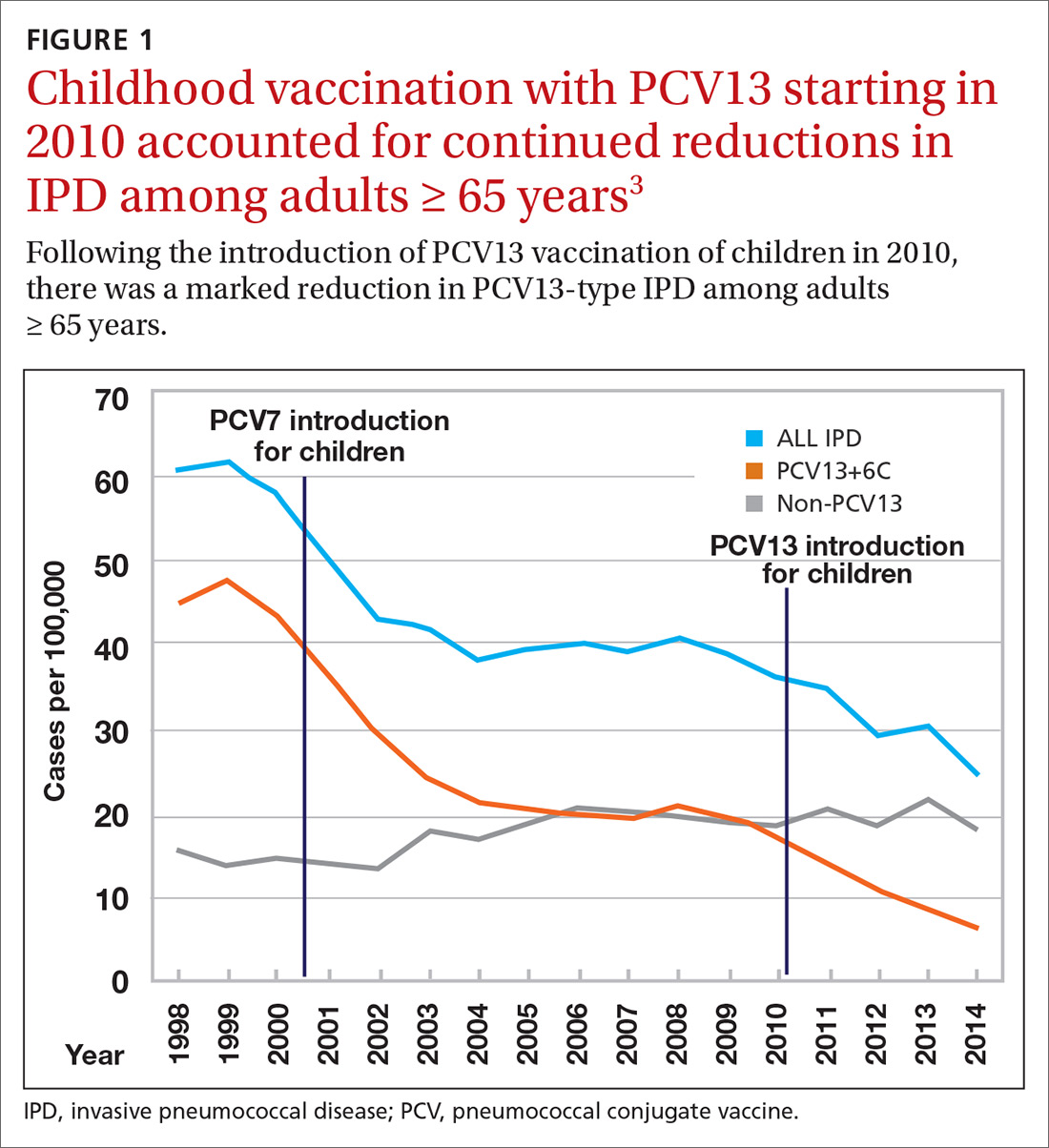

Nearly 20 years ago, PCV was introduced into the child immunization schedule in the United States as a 7-valent vaccine (PCV7). In 2010, it was modified to include 13 antigens. And in 2012, the use of PCV13 was expanded to include adults with immunocompromising conditions.1 In 2014, PCV13 was recommended as an addition to PPSV23 for adults ≥ 65 years.2 However, with this recommendation, ACIP noted that the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly had been declining since the introduction of PCV7 use in children in the year 2000 (FIGURE 13), presumably due to the decreased transmission of pneumococcal infections from children to older adults.

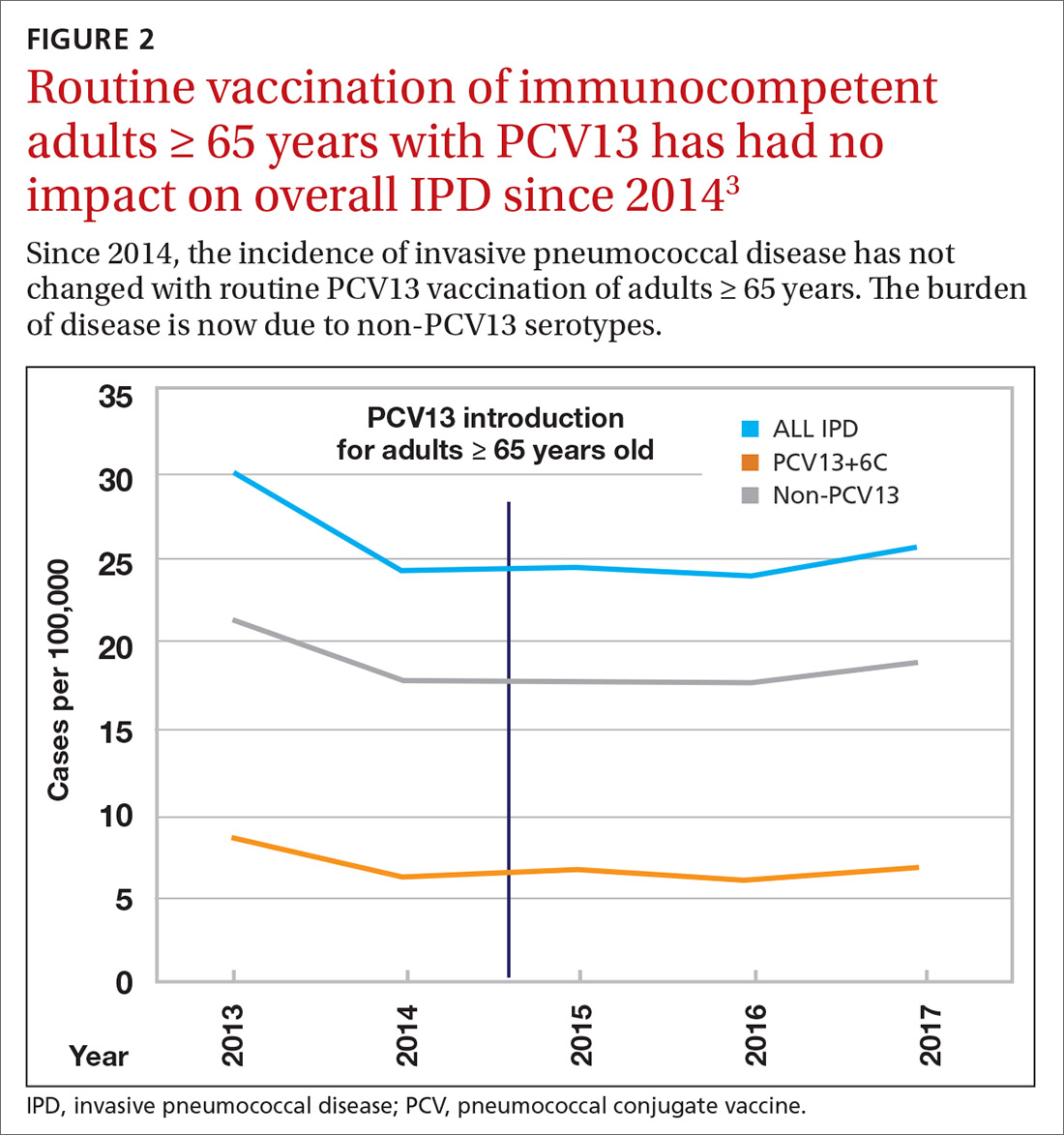

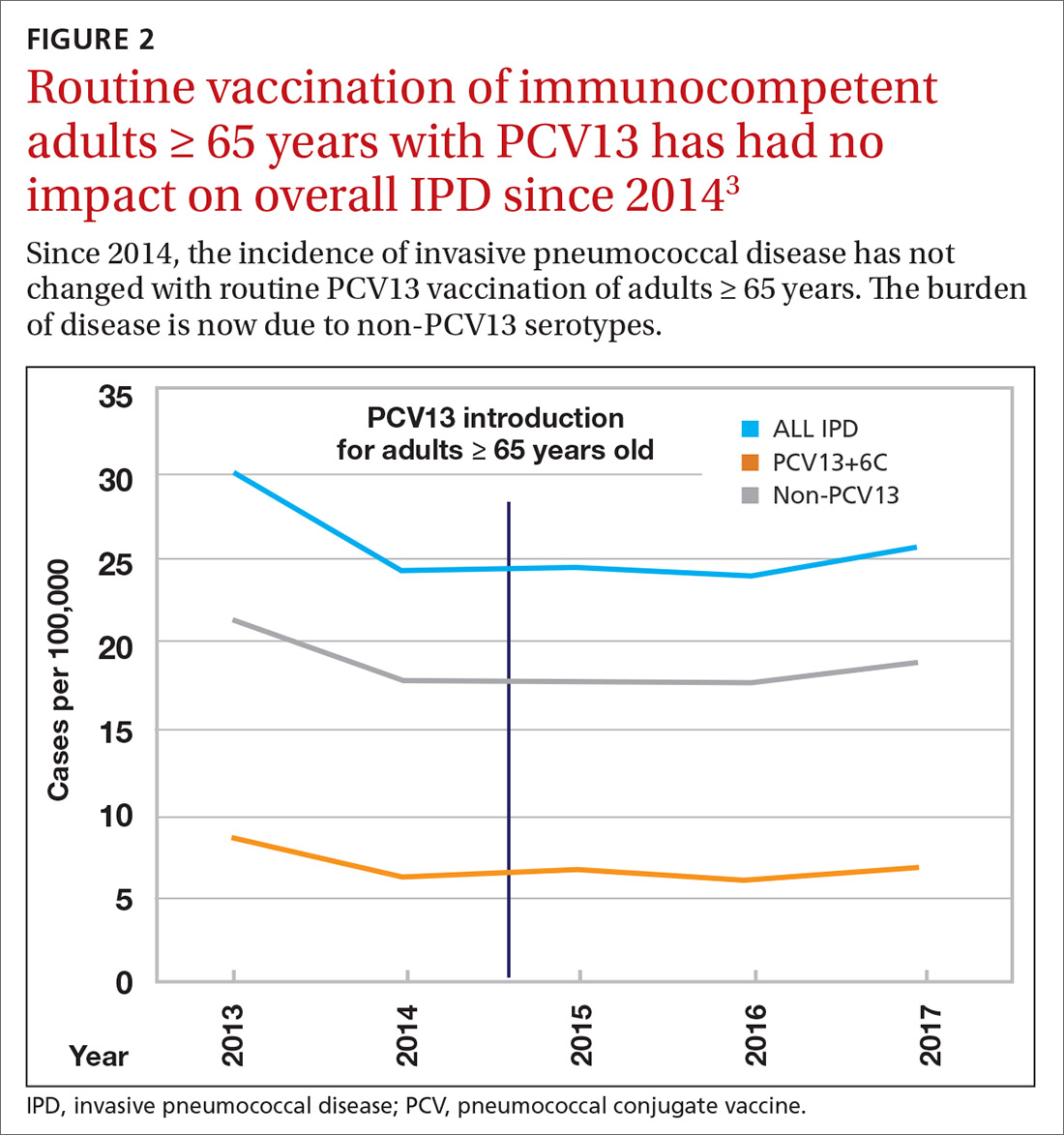

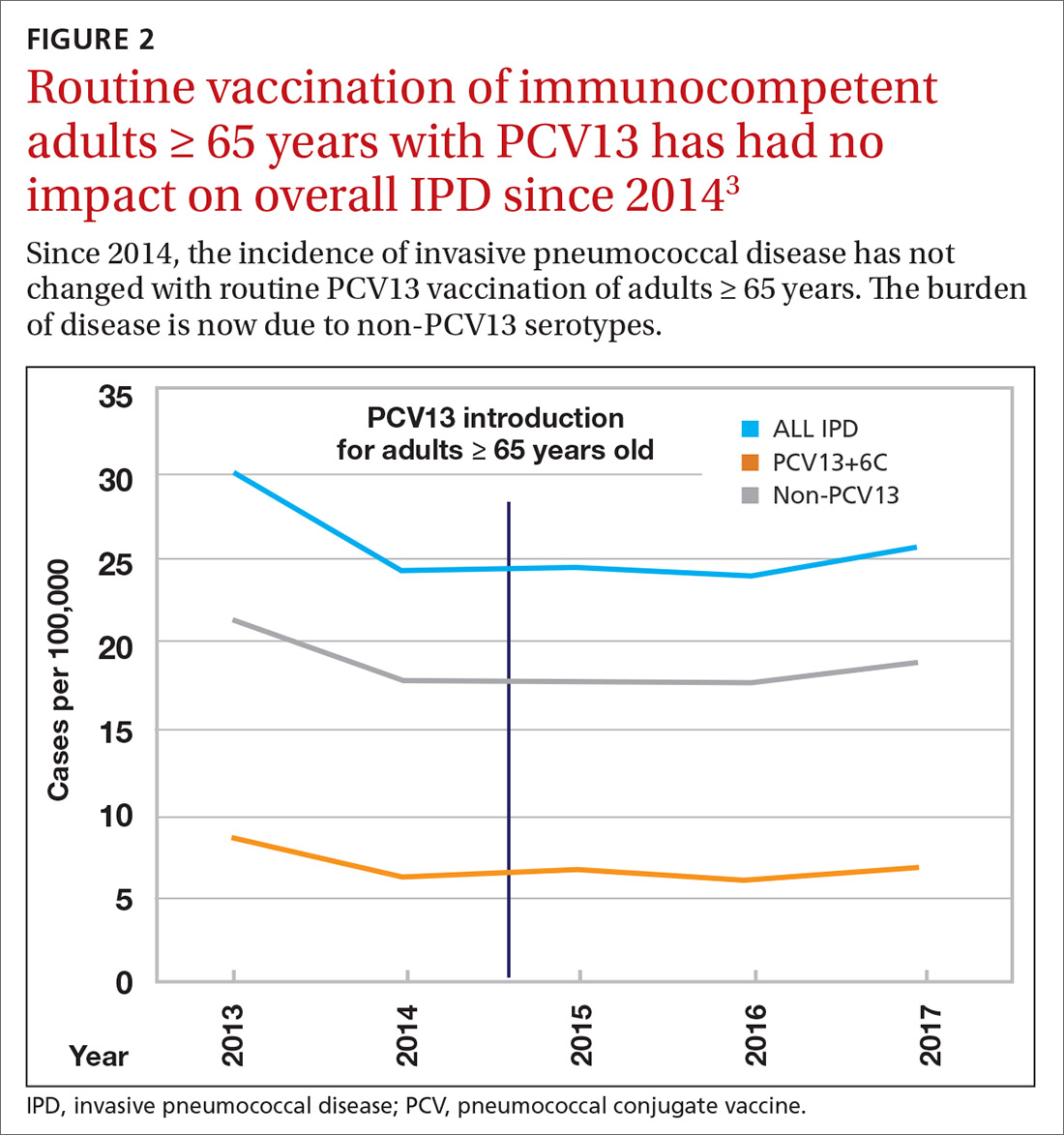

Because it was unclear in 2014 how much added benefit PCV13 would offer older adults, ACIP voted to restudy the issue after 4 years. At the June 2019 ACIP meeting, the results of an interim analysis were presented. ACIP concluded that routine use of PCV13 in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years adds little population-wide public health benefit given the vaccine’s routine use among children and immunocompromised adults (FIGURE 23).

ACIP had 3 options in formulating its recommendations.

- Recommend the vaccine for routine use universally or among designated high-risk groups.

- Do not recommend the vaccine.

- Recommend the vaccine only for specific patients after individualized clinical decision making.

The last option—the one ACIP decided on—applies when a safe and immunogenic vaccine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and may be beneficial for (or desired by) individuals even though it does not meet criteria for routine universal or targeted use.

Practical issues

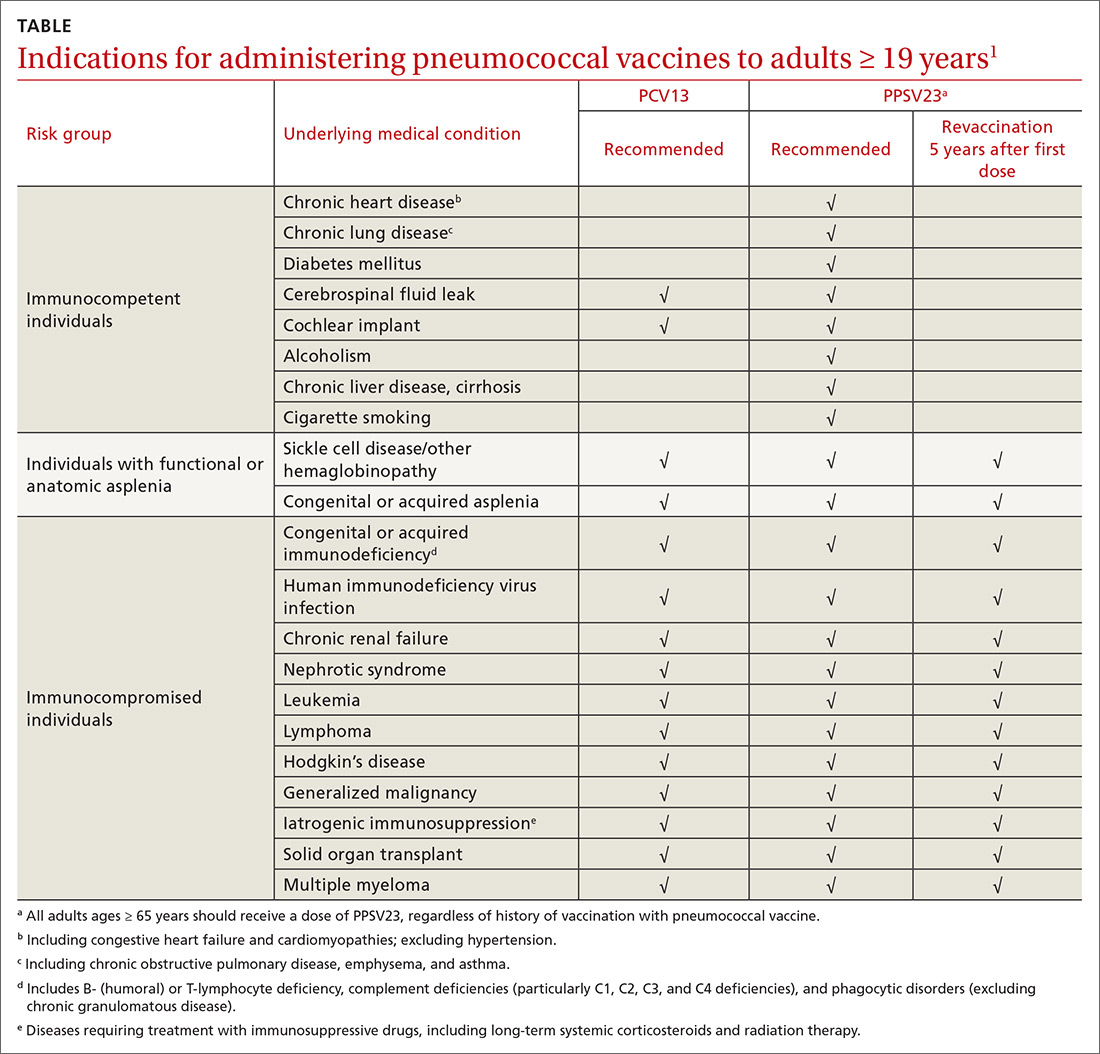

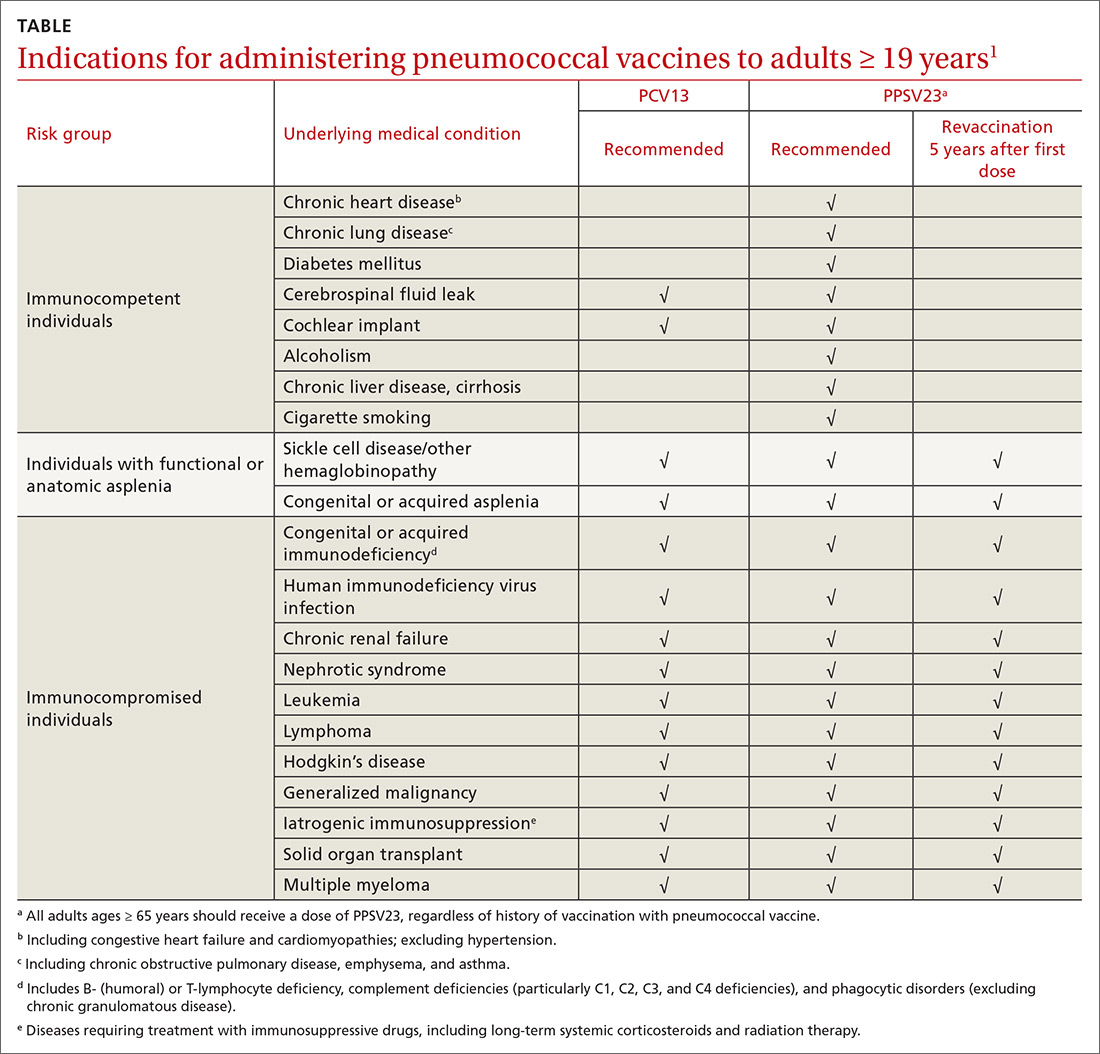

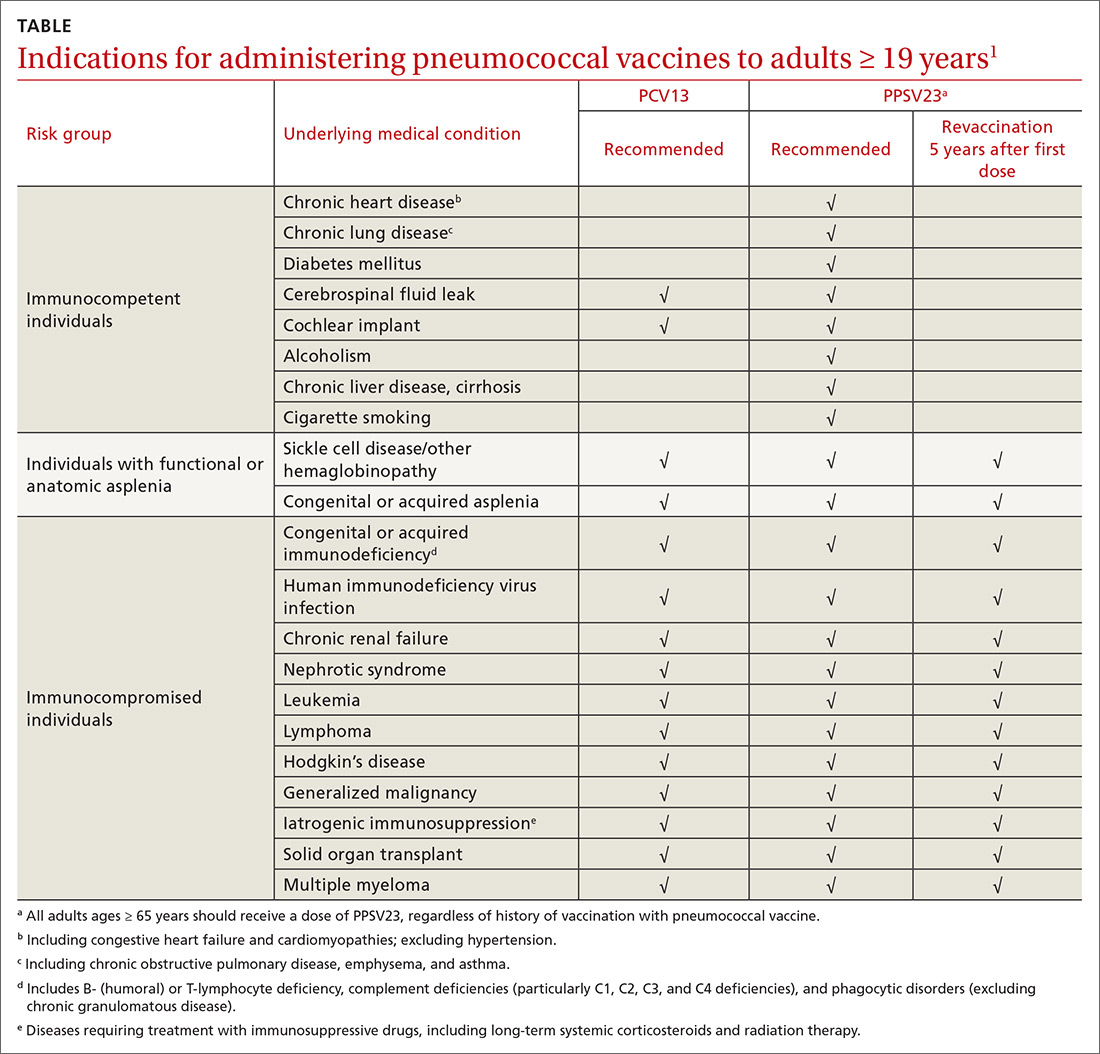

ACIP recommendations for the use of PCV13 and PPSV23 in adults vary according to 3 categories of health status: immunocompetent patients with underlying medical conditions; those with functional or anatomic asplenia; and immunocompromised individuals (TABLE1). Those in the latter 2 categories should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23 and be revaccinated once with PPSV23 before the age of 65 (given 5 years after the first dose). For immunocompetent individuals with underlying medical conditions, only those with cerebral spinal fluid leaks or cochlear implants should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23, although revaccination with PPSV23 before the age of 65 is not recommended.

Continue to: Prior to the recent change...

Prior to the recent change, ACIP recommended both PCV13 and PPSV23 for those ≥ 65 years. Now, PCV13 is not recommended routinely for immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years; however, individuals in this age group who have chronic underlying medical conditions may receive PCV13 after consulting with their physician. PPSV23 is still recommended for all adults in this age group. Recommendations for those with immunocompromising conditions are also unchanged.

3 sentences summarize change in vaccine intervals. Another source of confusion is the recommended intervals in administering the 2 vaccines when both are indicated. The current guidance has been simplified and can be summarized in 3 sentences4:

- When both PCV13 and PPSV23 are indicated, give PCV13 before PPSV23.

- For patients ≥ 65 years, separate the vaccines by 12 months or more—regardless of which vaccine is administered first.

- For patients who are 19 to 64 years of age, separate the vaccines by ≥ 8 weeks.

Advice on repeating the PPSV23 vaccine also can be summarized in 3 sentences1:

- When a repeat PPSV23 dose is indicated, give it at least 5 years after the first dose.

- Administer no more than 2 doses before age 65.

- For an individual older than 65, only 1 dose should be administered and it should be done at least 5 years after a previous PPSV23 dose.

1. CDC. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:816-819.

2. Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:822-825.

3. Matanock A. Considerations for PCV13 use among adults ≥65 years old and a summary of the evidence to recommendations framework. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Pneumococcal-2-Matanock-508.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

4. Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:944-947.

Two pneumococcal vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 [Prevnar 13, Wyeth]) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23 [Pneumovax, Merck]). The recommendations for using these vaccines in adults ages ≥ 19 years are arguably among the most complicated and confusing of all vaccine recommendations made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In June 2019, things got even more complicated with ACIP’s unusual decision to change the previous recommendation on the routine use of PCV13 in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent older adults only after individual clinical decision making. The recommendation for routine use of PPSV23 remains unchanged. This Practice Alert explains the reasoning behind this change and its practical implications.

How we got to where we are now

Nearly 20 years ago, PCV was introduced into the child immunization schedule in the United States as a 7-valent vaccine (PCV7). In 2010, it was modified to include 13 antigens. And in 2012, the use of PCV13 was expanded to include adults with immunocompromising conditions.1 In 2014, PCV13 was recommended as an addition to PPSV23 for adults ≥ 65 years.2 However, with this recommendation, ACIP noted that the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly had been declining since the introduction of PCV7 use in children in the year 2000 (FIGURE 13), presumably due to the decreased transmission of pneumococcal infections from children to older adults.

Because it was unclear in 2014 how much added benefit PCV13 would offer older adults, ACIP voted to restudy the issue after 4 years. At the June 2019 ACIP meeting, the results of an interim analysis were presented. ACIP concluded that routine use of PCV13 in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years adds little population-wide public health benefit given the vaccine’s routine use among children and immunocompromised adults (FIGURE 23).

ACIP had 3 options in formulating its recommendations.

- Recommend the vaccine for routine use universally or among designated high-risk groups.

- Do not recommend the vaccine.

- Recommend the vaccine only for specific patients after individualized clinical decision making.

The last option—the one ACIP decided on—applies when a safe and immunogenic vaccine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and may be beneficial for (or desired by) individuals even though it does not meet criteria for routine universal or targeted use.

Practical issues

ACIP recommendations for the use of PCV13 and PPSV23 in adults vary according to 3 categories of health status: immunocompetent patients with underlying medical conditions; those with functional or anatomic asplenia; and immunocompromised individuals (TABLE1). Those in the latter 2 categories should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23 and be revaccinated once with PPSV23 before the age of 65 (given 5 years after the first dose). For immunocompetent individuals with underlying medical conditions, only those with cerebral spinal fluid leaks or cochlear implants should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23, although revaccination with PPSV23 before the age of 65 is not recommended.

Continue to: Prior to the recent change...

Prior to the recent change, ACIP recommended both PCV13 and PPSV23 for those ≥ 65 years. Now, PCV13 is not recommended routinely for immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years; however, individuals in this age group who have chronic underlying medical conditions may receive PCV13 after consulting with their physician. PPSV23 is still recommended for all adults in this age group. Recommendations for those with immunocompromising conditions are also unchanged.

3 sentences summarize change in vaccine intervals. Another source of confusion is the recommended intervals in administering the 2 vaccines when both are indicated. The current guidance has been simplified and can be summarized in 3 sentences4:

- When both PCV13 and PPSV23 are indicated, give PCV13 before PPSV23.

- For patients ≥ 65 years, separate the vaccines by 12 months or more—regardless of which vaccine is administered first.

- For patients who are 19 to 64 years of age, separate the vaccines by ≥ 8 weeks.

Advice on repeating the PPSV23 vaccine also can be summarized in 3 sentences1:

- When a repeat PPSV23 dose is indicated, give it at least 5 years after the first dose.

- Administer no more than 2 doses before age 65.

- For an individual older than 65, only 1 dose should be administered and it should be done at least 5 years after a previous PPSV23 dose.

Two pneumococcal vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 [Prevnar 13, Wyeth]) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23 [Pneumovax, Merck]). The recommendations for using these vaccines in adults ages ≥ 19 years are arguably among the most complicated and confusing of all vaccine recommendations made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In June 2019, things got even more complicated with ACIP’s unusual decision to change the previous recommendation on the routine use of PCV13 in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent older adults only after individual clinical decision making. The recommendation for routine use of PPSV23 remains unchanged. This Practice Alert explains the reasoning behind this change and its practical implications.

How we got to where we are now

Nearly 20 years ago, PCV was introduced into the child immunization schedule in the United States as a 7-valent vaccine (PCV7). In 2010, it was modified to include 13 antigens. And in 2012, the use of PCV13 was expanded to include adults with immunocompromising conditions.1 In 2014, PCV13 was recommended as an addition to PPSV23 for adults ≥ 65 years.2 However, with this recommendation, ACIP noted that the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly had been declining since the introduction of PCV7 use in children in the year 2000 (FIGURE 13), presumably due to the decreased transmission of pneumococcal infections from children to older adults.

Because it was unclear in 2014 how much added benefit PCV13 would offer older adults, ACIP voted to restudy the issue after 4 years. At the June 2019 ACIP meeting, the results of an interim analysis were presented. ACIP concluded that routine use of PCV13 in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years adds little population-wide public health benefit given the vaccine’s routine use among children and immunocompromised adults (FIGURE 23).

ACIP had 3 options in formulating its recommendations.

- Recommend the vaccine for routine use universally or among designated high-risk groups.

- Do not recommend the vaccine.

- Recommend the vaccine only for specific patients after individualized clinical decision making.

The last option—the one ACIP decided on—applies when a safe and immunogenic vaccine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and may be beneficial for (or desired by) individuals even though it does not meet criteria for routine universal or targeted use.

Practical issues

ACIP recommendations for the use of PCV13 and PPSV23 in adults vary according to 3 categories of health status: immunocompetent patients with underlying medical conditions; those with functional or anatomic asplenia; and immunocompromised individuals (TABLE1). Those in the latter 2 categories should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23 and be revaccinated once with PPSV23 before the age of 65 (given 5 years after the first dose). For immunocompetent individuals with underlying medical conditions, only those with cerebral spinal fluid leaks or cochlear implants should receive both PCV13 and PPSV23, although revaccination with PPSV23 before the age of 65 is not recommended.

Continue to: Prior to the recent change...

Prior to the recent change, ACIP recommended both PCV13 and PPSV23 for those ≥ 65 years. Now, PCV13 is not recommended routinely for immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years; however, individuals in this age group who have chronic underlying medical conditions may receive PCV13 after consulting with their physician. PPSV23 is still recommended for all adults in this age group. Recommendations for those with immunocompromising conditions are also unchanged.

3 sentences summarize change in vaccine intervals. Another source of confusion is the recommended intervals in administering the 2 vaccines when both are indicated. The current guidance has been simplified and can be summarized in 3 sentences4:

- When both PCV13 and PPSV23 are indicated, give PCV13 before PPSV23.

- For patients ≥ 65 years, separate the vaccines by 12 months or more—regardless of which vaccine is administered first.

- For patients who are 19 to 64 years of age, separate the vaccines by ≥ 8 weeks.

Advice on repeating the PPSV23 vaccine also can be summarized in 3 sentences1:

- When a repeat PPSV23 dose is indicated, give it at least 5 years after the first dose.

- Administer no more than 2 doses before age 65.

- For an individual older than 65, only 1 dose should be administered and it should be done at least 5 years after a previous PPSV23 dose.

1. CDC. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:816-819.

2. Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:822-825.

3. Matanock A. Considerations for PCV13 use among adults ≥65 years old and a summary of the evidence to recommendations framework. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Pneumococcal-2-Matanock-508.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

4. Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:944-947.

1. CDC. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:816-819.

2. Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:822-825.

3. Matanock A. Considerations for PCV13 use among adults ≥65 years old and a summary of the evidence to recommendations framework. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Pneumococcal-2-Matanock-508.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

4. Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:944-947.

Could your patient benefit from a breast CA risk-reducing med?

References

1. Final update summary: breast cancer: medication use to reduce risk. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction1 Updated October 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

2. Final update summary: BRCA-related cancer: risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/brca-related-cancer-risk-assessment-genetic-counseling-and-genetic-testing1. Updated August 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF BRCA testing recs: 2 more groups require attention. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:audio. https://www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/208085/womens-health/uspstf-brca-testing-recs-2-more-groups-require-attention?channel=60894. Accessed November 25, 2019.

References

1. Final update summary: breast cancer: medication use to reduce risk. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction1 Updated October 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

2. Final update summary: BRCA-related cancer: risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/brca-related-cancer-risk-assessment-genetic-counseling-and-genetic-testing1. Updated August 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF BRCA testing recs: 2 more groups require attention. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:audio. https://www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/208085/womens-health/uspstf-brca-testing-recs-2-more-groups-require-attention?channel=60894. Accessed November 25, 2019.

References

1. Final update summary: breast cancer: medication use to reduce risk. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction1 Updated October 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

2. Final update summary: BRCA-related cancer: risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Web Site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/brca-related-cancer-risk-assessment-genetic-counseling-and-genetic-testing1. Updated August 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF BRCA testing recs: 2 more groups require attention. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:audio. https://www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/208085/womens-health/uspstf-brca-testing-recs-2-more-groups-require-attention?channel=60894. Accessed November 25, 2019.

Vaping related lung injury: Warning signs, care, & prevention

References

1. Lewis N, McCaffrey K, Sage K, et al. E-cigarette use, or vaping, practices and characteristics among persons with associated lung injury — Utah, April–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6842e1.htm?s_cid=mm6842e1_w. Published October 22, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.

2. Siegal DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury – United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:919-927.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.

References

1. Lewis N, McCaffrey K, Sage K, et al. E-cigarette use, or vaping, practices and characteristics among persons with associated lung injury — Utah, April–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6842e1.htm?s_cid=mm6842e1_w. Published October 22, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.

2. Siegal DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury – United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:919-927.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.

References

1. Lewis N, McCaffrey K, Sage K, et al. E-cigarette use, or vaping, practices and characteristics among persons with associated lung injury — Utah, April–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6842e1.htm?s_cid=mm6842e1_w. Published October 22, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.

2. Siegal DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury – United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:919-927.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2019.