User login

Dome-Shaped White Papules on the Earlobe

Dome-Shaped White Papules on the Earlobe

THE DIAGNOSIS: Trichodiscoma

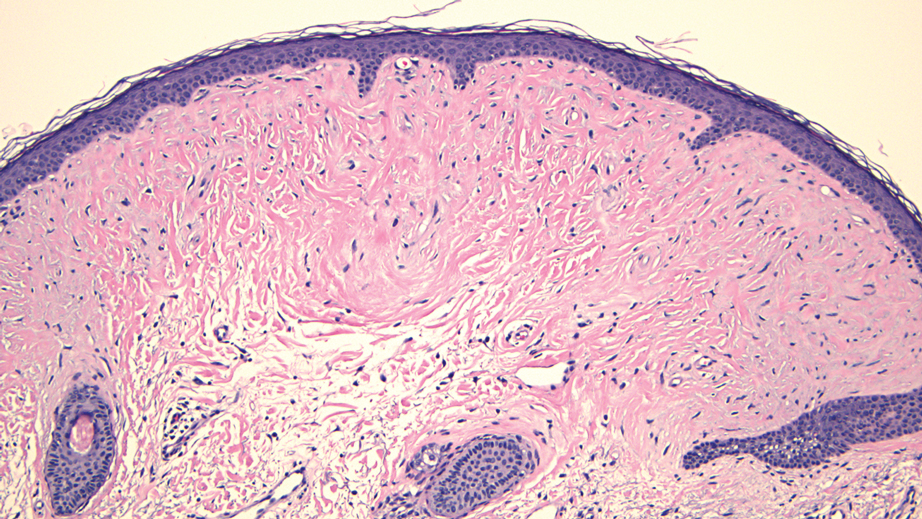

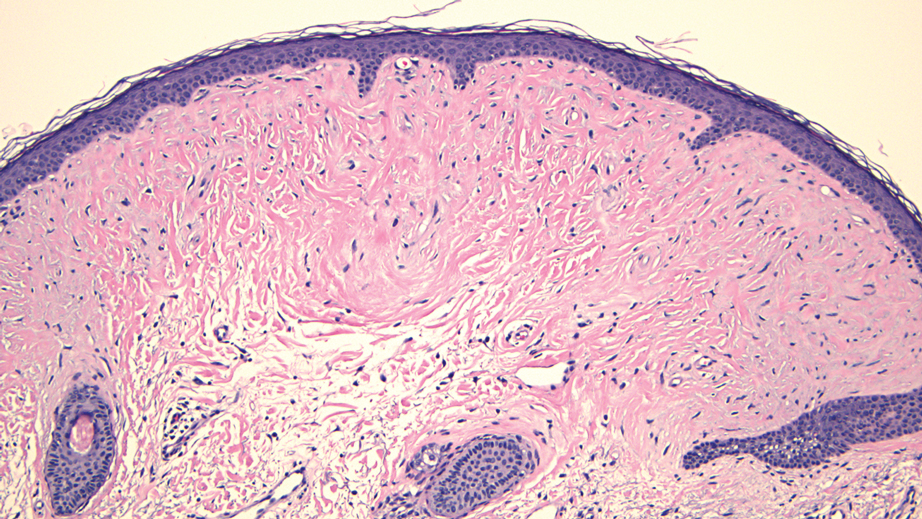

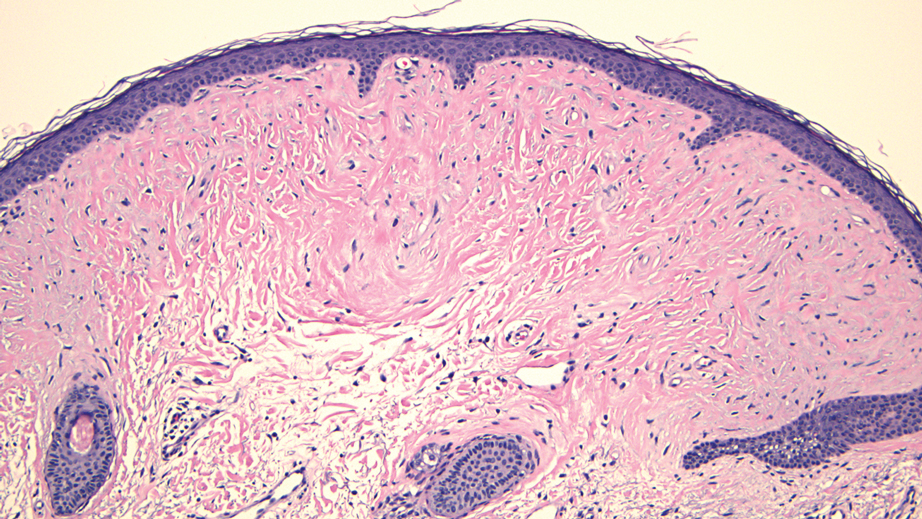

Histologic evaluation revealed an unremarkable epidermal surface and a subjacent well-demarcated superficial dermal nodule showing a proliferation, sometimes fascicular, of wavy and spindled fibroblasts with some stellate forms within a variably loose fibrous stroma. Some angioplasia and vascular ectasia also were seen (Figure). A diagnosis of trichodiscoma was made based on these histologic findings.

While the patient’s personal and family history of pneumothorax originally had been attributed to other causes, the diagnosis of trichodiscoma raised suspicion for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome due to the classic association of skin lesions (often trichodiscomas), renal cell carcinoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax in this condition. The patient was sent for genetic testing for the associated folliculin (FLCN) gene, which was positive and thereby confirmed the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. At the most recent follow-up almost 2 years after initial presentation, the lesions on the earlobe were stable. The patient has since undergone screening for abdominal and renal neoplasia with negative results, and he has had no other occurrences of pneumothorax.

Our case highlights the association between trichodiscomas and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which necessitates screening for renal cell carcinoma, pneumothorax, and lung cysts.1 Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal- dominant disorder of the skin and lungs that is characterized by a predisposition for renal carcinoma, pneumothorax, and colon polyps as well as cutaneous markers that include fibrofolliculomas, acrochordons, and trichodiscomas; the trichodiscomas tend to manifest as numerous smooth, flesh-colored or grayish-white papules on the face, ears, neck, and/or upper trunk.1

Trichodiscomas are benign lesions and do not require treatment2; however, if they are cosmetically bothersome to the patient, surgical excision is an option for single lesions. For more widespread cutaneous disease, combination therapy with a CO2 laser and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser may be utilized.3 The differential diagnosis for trichodiscoma includes basal cell carcinoma, fibrous papule, dermal nevus, and trichofolliculoma.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.4 Clinically, it typically manifests as pink or flesh-colored papules on the head or neck, often with overlying ulceration or telangiectasia. Due to its association with chronic sun exposure, the median age of diagnosis for basal cell carcinoma is 68 years. Histopathologically, basal cell carcinoma is characterized by islands or nests of atypical basaloid cells with palisading cells at the periphery.4 Treatment depends on the location and size of the lesion, but Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common intervention on the face and ears.5

In contrast, fibrous papules are benign lesions that manifest clinically as small, firm, flesh-colored papules that most commonly are found on the nose.6,7 On dermatopathology, classic findings include fibrovascular proliferation and scattered multinucleated triangular or stellate cells in the upper dermis.7 Due to the benign nature of the lesion, treatment is not required6; however, shave excision, electrodessication, and laser therapies can be attempted if the patient chooses to pursue treatment.8

Dermal nevus is a type of benign acquired melanocytic nevus that manifests clinically as a light-brown to flesh-colored, dome-shaped or papillomatous papule.9 It typically develops in areas that are exposed to the sun, including the face.10 There also have been cases of dermal nevi on the ear.11 Histopathology shows melanocytic nevus cells that have completely detached from the epidermis and are located entirely in the dermis.12 While dermal nevi are benign and treatment is not necessary, surgical excision is an option for patients who request removal.13

Trichofolliculoma is a benign tumor of the adnexa that shows follicular differentiation on histopathology.14 On physical examination, it manifests as an isolated flesh-colored papule or nodule with a central pore from which tufted hairs protrude. These lesions usually appear on the face or scalp and occur more commonly in women than in men. While these may be clinically indistinguishable from trichodiscomas, the absence of protruding hair in our patient’s case makes trichofolliculoma less likely. When biopsied, histopathology classically shows a cystically dilated hair follicle with keratinous material and several mature and immature branched follicular structures. Preferred treatment for trichofolliculomas is surgical excision, and recurrence is rare.14

- Toro JR, Glenn G, Duray P, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195-202. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.10.1195

- Tong Y, Coda AB, Schneider JA, et al. Familial multiple trichodiscomas: case report and concise review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1596. doi:10.7759/cureus.1596

- Riley J, Athalye L, Tran D, et al. Concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen. Cutis. 2018;102:E30-E32.

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 13, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

- Bittner GC, Kubo EM, Fantini BC, et al. Auricular reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery: analysis of 101 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:408-415. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.12.008

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001083

- Jacyk WK, Rütten A, Requena L. Fibrous papule of the face with granular cells. Dermatology. 2008;216:56-59. doi:10.1159/000109359

- Macri A, Kwan E, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 19, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482470/

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Agozzino M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma and dermal nevi of the face: comparison of localization and dermatoscopic features. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:996-1002. doi:10.1111/ijd.15554

- Alves RV, Brandão FH, Aquino JE, et al. Intradermal melanocytic nevus of the external auditory canal. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:104-106. doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31295-7

- Muradia I, Khunger N, Yadav AK. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological analysis of common acquired melanocytic nevi in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:41-51.

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Massara B, Sellami K, Graja S, et al. Trichofolliculoma: a case series. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16:41-43.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Trichodiscoma

Histologic evaluation revealed an unremarkable epidermal surface and a subjacent well-demarcated superficial dermal nodule showing a proliferation, sometimes fascicular, of wavy and spindled fibroblasts with some stellate forms within a variably loose fibrous stroma. Some angioplasia and vascular ectasia also were seen (Figure). A diagnosis of trichodiscoma was made based on these histologic findings.

While the patient’s personal and family history of pneumothorax originally had been attributed to other causes, the diagnosis of trichodiscoma raised suspicion for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome due to the classic association of skin lesions (often trichodiscomas), renal cell carcinoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax in this condition. The patient was sent for genetic testing for the associated folliculin (FLCN) gene, which was positive and thereby confirmed the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. At the most recent follow-up almost 2 years after initial presentation, the lesions on the earlobe were stable. The patient has since undergone screening for abdominal and renal neoplasia with negative results, and he has had no other occurrences of pneumothorax.

Our case highlights the association between trichodiscomas and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which necessitates screening for renal cell carcinoma, pneumothorax, and lung cysts.1 Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal- dominant disorder of the skin and lungs that is characterized by a predisposition for renal carcinoma, pneumothorax, and colon polyps as well as cutaneous markers that include fibrofolliculomas, acrochordons, and trichodiscomas; the trichodiscomas tend to manifest as numerous smooth, flesh-colored or grayish-white papules on the face, ears, neck, and/or upper trunk.1

Trichodiscomas are benign lesions and do not require treatment2; however, if they are cosmetically bothersome to the patient, surgical excision is an option for single lesions. For more widespread cutaneous disease, combination therapy with a CO2 laser and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser may be utilized.3 The differential diagnosis for trichodiscoma includes basal cell carcinoma, fibrous papule, dermal nevus, and trichofolliculoma.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.4 Clinically, it typically manifests as pink or flesh-colored papules on the head or neck, often with overlying ulceration or telangiectasia. Due to its association with chronic sun exposure, the median age of diagnosis for basal cell carcinoma is 68 years. Histopathologically, basal cell carcinoma is characterized by islands or nests of atypical basaloid cells with palisading cells at the periphery.4 Treatment depends on the location and size of the lesion, but Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common intervention on the face and ears.5

In contrast, fibrous papules are benign lesions that manifest clinically as small, firm, flesh-colored papules that most commonly are found on the nose.6,7 On dermatopathology, classic findings include fibrovascular proliferation and scattered multinucleated triangular or stellate cells in the upper dermis.7 Due to the benign nature of the lesion, treatment is not required6; however, shave excision, electrodessication, and laser therapies can be attempted if the patient chooses to pursue treatment.8

Dermal nevus is a type of benign acquired melanocytic nevus that manifests clinically as a light-brown to flesh-colored, dome-shaped or papillomatous papule.9 It typically develops in areas that are exposed to the sun, including the face.10 There also have been cases of dermal nevi on the ear.11 Histopathology shows melanocytic nevus cells that have completely detached from the epidermis and are located entirely in the dermis.12 While dermal nevi are benign and treatment is not necessary, surgical excision is an option for patients who request removal.13

Trichofolliculoma is a benign tumor of the adnexa that shows follicular differentiation on histopathology.14 On physical examination, it manifests as an isolated flesh-colored papule or nodule with a central pore from which tufted hairs protrude. These lesions usually appear on the face or scalp and occur more commonly in women than in men. While these may be clinically indistinguishable from trichodiscomas, the absence of protruding hair in our patient’s case makes trichofolliculoma less likely. When biopsied, histopathology classically shows a cystically dilated hair follicle with keratinous material and several mature and immature branched follicular structures. Preferred treatment for trichofolliculomas is surgical excision, and recurrence is rare.14

THE DIAGNOSIS: Trichodiscoma

Histologic evaluation revealed an unremarkable epidermal surface and a subjacent well-demarcated superficial dermal nodule showing a proliferation, sometimes fascicular, of wavy and spindled fibroblasts with some stellate forms within a variably loose fibrous stroma. Some angioplasia and vascular ectasia also were seen (Figure). A diagnosis of trichodiscoma was made based on these histologic findings.

While the patient’s personal and family history of pneumothorax originally had been attributed to other causes, the diagnosis of trichodiscoma raised suspicion for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome due to the classic association of skin lesions (often trichodiscomas), renal cell carcinoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax in this condition. The patient was sent for genetic testing for the associated folliculin (FLCN) gene, which was positive and thereby confirmed the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. At the most recent follow-up almost 2 years after initial presentation, the lesions on the earlobe were stable. The patient has since undergone screening for abdominal and renal neoplasia with negative results, and he has had no other occurrences of pneumothorax.

Our case highlights the association between trichodiscomas and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which necessitates screening for renal cell carcinoma, pneumothorax, and lung cysts.1 Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal- dominant disorder of the skin and lungs that is characterized by a predisposition for renal carcinoma, pneumothorax, and colon polyps as well as cutaneous markers that include fibrofolliculomas, acrochordons, and trichodiscomas; the trichodiscomas tend to manifest as numerous smooth, flesh-colored or grayish-white papules on the face, ears, neck, and/or upper trunk.1

Trichodiscomas are benign lesions and do not require treatment2; however, if they are cosmetically bothersome to the patient, surgical excision is an option for single lesions. For more widespread cutaneous disease, combination therapy with a CO2 laser and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser may be utilized.3 The differential diagnosis for trichodiscoma includes basal cell carcinoma, fibrous papule, dermal nevus, and trichofolliculoma.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.4 Clinically, it typically manifests as pink or flesh-colored papules on the head or neck, often with overlying ulceration or telangiectasia. Due to its association with chronic sun exposure, the median age of diagnosis for basal cell carcinoma is 68 years. Histopathologically, basal cell carcinoma is characterized by islands or nests of atypical basaloid cells with palisading cells at the periphery.4 Treatment depends on the location and size of the lesion, but Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common intervention on the face and ears.5

In contrast, fibrous papules are benign lesions that manifest clinically as small, firm, flesh-colored papules that most commonly are found on the nose.6,7 On dermatopathology, classic findings include fibrovascular proliferation and scattered multinucleated triangular or stellate cells in the upper dermis.7 Due to the benign nature of the lesion, treatment is not required6; however, shave excision, electrodessication, and laser therapies can be attempted if the patient chooses to pursue treatment.8

Dermal nevus is a type of benign acquired melanocytic nevus that manifests clinically as a light-brown to flesh-colored, dome-shaped or papillomatous papule.9 It typically develops in areas that are exposed to the sun, including the face.10 There also have been cases of dermal nevi on the ear.11 Histopathology shows melanocytic nevus cells that have completely detached from the epidermis and are located entirely in the dermis.12 While dermal nevi are benign and treatment is not necessary, surgical excision is an option for patients who request removal.13

Trichofolliculoma is a benign tumor of the adnexa that shows follicular differentiation on histopathology.14 On physical examination, it manifests as an isolated flesh-colored papule or nodule with a central pore from which tufted hairs protrude. These lesions usually appear on the face or scalp and occur more commonly in women than in men. While these may be clinically indistinguishable from trichodiscomas, the absence of protruding hair in our patient’s case makes trichofolliculoma less likely. When biopsied, histopathology classically shows a cystically dilated hair follicle with keratinous material and several mature and immature branched follicular structures. Preferred treatment for trichofolliculomas is surgical excision, and recurrence is rare.14

- Toro JR, Glenn G, Duray P, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195-202. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.10.1195

- Tong Y, Coda AB, Schneider JA, et al. Familial multiple trichodiscomas: case report and concise review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1596. doi:10.7759/cureus.1596

- Riley J, Athalye L, Tran D, et al. Concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen. Cutis. 2018;102:E30-E32.

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 13, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

- Bittner GC, Kubo EM, Fantini BC, et al. Auricular reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery: analysis of 101 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:408-415. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.12.008

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001083

- Jacyk WK, Rütten A, Requena L. Fibrous papule of the face with granular cells. Dermatology. 2008;216:56-59. doi:10.1159/000109359

- Macri A, Kwan E, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 19, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482470/

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Agozzino M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma and dermal nevi of the face: comparison of localization and dermatoscopic features. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:996-1002. doi:10.1111/ijd.15554

- Alves RV, Brandão FH, Aquino JE, et al. Intradermal melanocytic nevus of the external auditory canal. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:104-106. doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31295-7

- Muradia I, Khunger N, Yadav AK. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological analysis of common acquired melanocytic nevi in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:41-51.

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Massara B, Sellami K, Graja S, et al. Trichofolliculoma: a case series. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16:41-43.

- Toro JR, Glenn G, Duray P, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195-202. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.10.1195

- Tong Y, Coda AB, Schneider JA, et al. Familial multiple trichodiscomas: case report and concise review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1596. doi:10.7759/cureus.1596

- Riley J, Athalye L, Tran D, et al. Concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen. Cutis. 2018;102:E30-E32.

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 13, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

- Bittner GC, Kubo EM, Fantini BC, et al. Auricular reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery: analysis of 101 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:408-415. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.12.008

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001083

- Jacyk WK, Rütten A, Requena L. Fibrous papule of the face with granular cells. Dermatology. 2008;216:56-59. doi:10.1159/000109359

- Macri A, Kwan E, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 19, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482470/

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Agozzino M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma and dermal nevi of the face: comparison of localization and dermatoscopic features. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:996-1002. doi:10.1111/ijd.15554

- Alves RV, Brandão FH, Aquino JE, et al. Intradermal melanocytic nevus of the external auditory canal. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:104-106. doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31295-7

- Muradia I, Khunger N, Yadav AK. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological analysis of common acquired melanocytic nevi in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:41-51.

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89-103. doi:10.2147/CCID.S57782

- Massara B, Sellami K, Graja S, et al. Trichofolliculoma: a case series. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16:41-43.

Dome-Shaped White Papules on the Earlobe

Dome-Shaped White Papules on the Earlobe

A 70-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for a routine full-body skin examination that revealed multiple asymptomatic, dome-shaped, white papules on the left posterior earlobe. The patient had a personal and family history of spontaneous pneumothorax and no history of cancer. A shave biopsy of one of the papules was performed.

Digital Strategies For Dermatology Patient Education

Technology offers new opportunities that can both enhance and challenge the physician-patient relationship, including the ways in which patients are educated. Ensuring dermatology patients are appropriately educated about their conditions can improve clinical care and treatment adherence, increase patient satisfaction, and potentially decrease medical costs. There are various digital methods by which physicians can deliver information to their patients, and while there are benefits and drawbacks to each, many Americans turn to the Internet for health information—a practice that is only predicted to become more prevalent.1

Dermatologists should strive to keep up with this trend by staying informed about the digital patient education options that are available and which tools they can use to more effectively share their knowledge with patients. Electronic health education has a powerful potential, but it is up to physicians to direct patients to the appropriate resources and education tools that will support their clear understanding of all elements of care.

Effective patient education can transform the role of the patient from passive recipient to active participant in his/her care and subsequently supports the physician-patient relationship. The benefits of patient education are timely and valuable with the new pay-for-performance model instated by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act and the Merit-based Incentive Payment System.2 In dermatology, patient education alone can essentially be a management strategy for numerous conditions (eg, identifying which triggers patients with contact dermatitis should avoid). On the other hand, a lack of patient knowledge can result in perceived noncompliance or treatment failure, when in reality there has simply been a communication gap between the physician and the patient. For example, if a patient notices little to no improvement of a fungal infection after applying ketoconazole shampoo 2% to affected areas and immediately rinsing, this does not necessarily constitute a treatment failure, as the patient should have been educated on the importance of leaving the shampoo on for 5 minutes before rinsing. One study alluded to this communication gap, revealing physicians’ tendency to overestimate how effectively they are communicating with their patients.3

Successful patient education ultimately is dependent on both the content provided and the method of delivery. In one survey of 2636 Internet users, 72% of respondents admitted to searching online for health information within the previous year; however, the same survey showed that physicians remain patients’ most trusted source of information.4 Physicians can use digital education methods to fulfill patient needs by providing them with and directing them to credible up-to-date sources.

Physicians can use electronic medical record (EMR) systems to electronically deliver health information to patients by directly communicating via an online patient portal. Allowing patients to engage with their health care providers electronically has been shown to increase patient satisfaction, promote adherence to preventative and treatment recommendations, improve clinical outcomes, and lower medical costs.5 The online portal can provide direct links for patients to digital resources; for example, MedlinePlus Connect (https://medlineplus.gov/connect/overview.html) is a free service that connects patients to MedlinePlus, an authoritative, up-to-date health information resource for consumer health information; however, many EMR systems lack quality dermatology content, as there is a greater emphasis on primary care, and patient usage of these online portals also is notoriously low.6 Dermatologists can work with EMR vendors to enhance the dermatology content for patient portals, and in some cases, specialty-specific content may be available for an additional fee. Clinicians can make their patients aware of the online portal and incentivize its use by sending an informational email, including a link on their practice’s website, promoting the portal during check-in and check-out at office visits, making tablets or kiosks available in the waiting room for sign-up, hanging posters in the examination rooms, and explaining the portal’s useful features during consultations with patients.

Mobile apps have revolutionized the potential for dermatologists to streamline patient education to a large population. In a 2014 review of 365 dermatology mobile apps, 13% were categorized as educational aids, adding to the realm of possibilities for digital patient education. For example, these apps may provide information on specific dermatologic conditions and medications, help users perform skin cancer checks, and provide reminders for when to administer injections for those on biologics. However, a drawback of medical mobile apps is that, to date, the US Food and Drug Administration has not released formal guidelines for their development.

It would be impractical for busy dermatologists to keep up with the credibility of every mobile app available in a growing market, but one solution could be for physicians to stay informed on only the most popular and most reviewed apps to keep in their digital toolbox. In 2014, the most reviewed dermatology app was the Dermatology app, which provided a guide to common dermatologic conditions and included images and a list of symptoms.7 To help keep physicians up to date on the most reliable dermatology apps, specialty societies, journal task forces, or interested dermatologists, residents, or medical students could publish updated literature on the most popular and most reviewed dermatology apps for patient education annually or biannually.

A practice’s website is a prime place for physicians to direct patients to educational content. Although many dermatology practice websites offer clinical information, the content often is focused on cosmetic procedures or is designed for search engine optimization to support online marketing and therefore may not be helpful to patients trying to understand a specific condition or treatment. Links to trusted resources, such as dermatology journals or medical societies, may be added but also would direct patients away from the practice’s website and would not allow physicians to customize the information he or she would like to share with their patients. Dermatologists should consider investing time and money into customizing educational material for their websites so patients can access health information from the source they trust most: their own physician.

Many of these digital options are useful for patients who want to access education material outside of the physician’s office, but digital opportunities to enhance point-of-care education also are available. In 2016, the American Academy of Dermatology partnered with ContextMedia:Health with the goal of delivering important decision enhancement technologies, educational content, and intelligence to patients and dermatologists for use before and during the consultation.8 ContextMedia:Health’s digital wallboard tablets are an engaging way to visually explain conditions and treatments to patients during the consultation, thus empowering physicians and patients to make decisions together and helping patients to be better advocates of their own health care. The downside is that health care workers must devote time and resources to be trained in using these devices.

The increasing availability of technology for electronic health information can be both beneficial and challenging for dermatologists. Physicians should explore and familiarize themselves with the tools that are available and assess their effectiveness by communicating with patients about their perception and understanding of their conditions. Digital delivery of health information is not meant to replace other methods of patient education but to supplement and reinforce them that which is verbally discussed during the office visit. Electronic health education demonstrates powerful potential, but it is up to the physician to direct patients to the appropriate resources and educational tools that will support a clear understanding of all elements of care.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Becker (Berkeley, California) for helpful discussion and reviewing this manuscript.

- Explosive growth in healthcare apps raises oversight questions. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- What’s MACRA? Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Updated November 16, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495-507.

- Dutta-Bergman M. Trusted online sources of health information: differences in demographics, health beliefs, and health-information orientation [published online September 25, 2003]. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5:E21.

- Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, et al. Patient portals: who uses them? what features do they use? and do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7:489-501.

- Lin CT, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, et al. An internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:E47.

- Patel S, Eluri M, Boyers LN, et al. Update on mobile applications in dermatology [published online November 9, 2014]. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21. pii:13030/qt1zc343js.

- American Academy of Dermatology selects ContextMedia:Health as patient education affinity partner. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-selects-patient-education-affinity-partner. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed February 25, 2018.

Technology offers new opportunities that can both enhance and challenge the physician-patient relationship, including the ways in which patients are educated. Ensuring dermatology patients are appropriately educated about their conditions can improve clinical care and treatment adherence, increase patient satisfaction, and potentially decrease medical costs. There are various digital methods by which physicians can deliver information to their patients, and while there are benefits and drawbacks to each, many Americans turn to the Internet for health information—a practice that is only predicted to become more prevalent.1

Dermatologists should strive to keep up with this trend by staying informed about the digital patient education options that are available and which tools they can use to more effectively share their knowledge with patients. Electronic health education has a powerful potential, but it is up to physicians to direct patients to the appropriate resources and education tools that will support their clear understanding of all elements of care.

Effective patient education can transform the role of the patient from passive recipient to active participant in his/her care and subsequently supports the physician-patient relationship. The benefits of patient education are timely and valuable with the new pay-for-performance model instated by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act and the Merit-based Incentive Payment System.2 In dermatology, patient education alone can essentially be a management strategy for numerous conditions (eg, identifying which triggers patients with contact dermatitis should avoid). On the other hand, a lack of patient knowledge can result in perceived noncompliance or treatment failure, when in reality there has simply been a communication gap between the physician and the patient. For example, if a patient notices little to no improvement of a fungal infection after applying ketoconazole shampoo 2% to affected areas and immediately rinsing, this does not necessarily constitute a treatment failure, as the patient should have been educated on the importance of leaving the shampoo on for 5 minutes before rinsing. One study alluded to this communication gap, revealing physicians’ tendency to overestimate how effectively they are communicating with their patients.3

Successful patient education ultimately is dependent on both the content provided and the method of delivery. In one survey of 2636 Internet users, 72% of respondents admitted to searching online for health information within the previous year; however, the same survey showed that physicians remain patients’ most trusted source of information.4 Physicians can use digital education methods to fulfill patient needs by providing them with and directing them to credible up-to-date sources.

Physicians can use electronic medical record (EMR) systems to electronically deliver health information to patients by directly communicating via an online patient portal. Allowing patients to engage with their health care providers electronically has been shown to increase patient satisfaction, promote adherence to preventative and treatment recommendations, improve clinical outcomes, and lower medical costs.5 The online portal can provide direct links for patients to digital resources; for example, MedlinePlus Connect (https://medlineplus.gov/connect/overview.html) is a free service that connects patients to MedlinePlus, an authoritative, up-to-date health information resource for consumer health information; however, many EMR systems lack quality dermatology content, as there is a greater emphasis on primary care, and patient usage of these online portals also is notoriously low.6 Dermatologists can work with EMR vendors to enhance the dermatology content for patient portals, and in some cases, specialty-specific content may be available for an additional fee. Clinicians can make their patients aware of the online portal and incentivize its use by sending an informational email, including a link on their practice’s website, promoting the portal during check-in and check-out at office visits, making tablets or kiosks available in the waiting room for sign-up, hanging posters in the examination rooms, and explaining the portal’s useful features during consultations with patients.

Mobile apps have revolutionized the potential for dermatologists to streamline patient education to a large population. In a 2014 review of 365 dermatology mobile apps, 13% were categorized as educational aids, adding to the realm of possibilities for digital patient education. For example, these apps may provide information on specific dermatologic conditions and medications, help users perform skin cancer checks, and provide reminders for when to administer injections for those on biologics. However, a drawback of medical mobile apps is that, to date, the US Food and Drug Administration has not released formal guidelines for their development.

It would be impractical for busy dermatologists to keep up with the credibility of every mobile app available in a growing market, but one solution could be for physicians to stay informed on only the most popular and most reviewed apps to keep in their digital toolbox. In 2014, the most reviewed dermatology app was the Dermatology app, which provided a guide to common dermatologic conditions and included images and a list of symptoms.7 To help keep physicians up to date on the most reliable dermatology apps, specialty societies, journal task forces, or interested dermatologists, residents, or medical students could publish updated literature on the most popular and most reviewed dermatology apps for patient education annually or biannually.

A practice’s website is a prime place for physicians to direct patients to educational content. Although many dermatology practice websites offer clinical information, the content often is focused on cosmetic procedures or is designed for search engine optimization to support online marketing and therefore may not be helpful to patients trying to understand a specific condition or treatment. Links to trusted resources, such as dermatology journals or medical societies, may be added but also would direct patients away from the practice’s website and would not allow physicians to customize the information he or she would like to share with their patients. Dermatologists should consider investing time and money into customizing educational material for their websites so patients can access health information from the source they trust most: their own physician.

Many of these digital options are useful for patients who want to access education material outside of the physician’s office, but digital opportunities to enhance point-of-care education also are available. In 2016, the American Academy of Dermatology partnered with ContextMedia:Health with the goal of delivering important decision enhancement technologies, educational content, and intelligence to patients and dermatologists for use before and during the consultation.8 ContextMedia:Health’s digital wallboard tablets are an engaging way to visually explain conditions and treatments to patients during the consultation, thus empowering physicians and patients to make decisions together and helping patients to be better advocates of their own health care. The downside is that health care workers must devote time and resources to be trained in using these devices.

The increasing availability of technology for electronic health information can be both beneficial and challenging for dermatologists. Physicians should explore and familiarize themselves with the tools that are available and assess their effectiveness by communicating with patients about their perception and understanding of their conditions. Digital delivery of health information is not meant to replace other methods of patient education but to supplement and reinforce them that which is verbally discussed during the office visit. Electronic health education demonstrates powerful potential, but it is up to the physician to direct patients to the appropriate resources and educational tools that will support a clear understanding of all elements of care.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Becker (Berkeley, California) for helpful discussion and reviewing this manuscript.

Technology offers new opportunities that can both enhance and challenge the physician-patient relationship, including the ways in which patients are educated. Ensuring dermatology patients are appropriately educated about their conditions can improve clinical care and treatment adherence, increase patient satisfaction, and potentially decrease medical costs. There are various digital methods by which physicians can deliver information to their patients, and while there are benefits and drawbacks to each, many Americans turn to the Internet for health information—a practice that is only predicted to become more prevalent.1

Dermatologists should strive to keep up with this trend by staying informed about the digital patient education options that are available and which tools they can use to more effectively share their knowledge with patients. Electronic health education has a powerful potential, but it is up to physicians to direct patients to the appropriate resources and education tools that will support their clear understanding of all elements of care.

Effective patient education can transform the role of the patient from passive recipient to active participant in his/her care and subsequently supports the physician-patient relationship. The benefits of patient education are timely and valuable with the new pay-for-performance model instated by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act and the Merit-based Incentive Payment System.2 In dermatology, patient education alone can essentially be a management strategy for numerous conditions (eg, identifying which triggers patients with contact dermatitis should avoid). On the other hand, a lack of patient knowledge can result in perceived noncompliance or treatment failure, when in reality there has simply been a communication gap between the physician and the patient. For example, if a patient notices little to no improvement of a fungal infection after applying ketoconazole shampoo 2% to affected areas and immediately rinsing, this does not necessarily constitute a treatment failure, as the patient should have been educated on the importance of leaving the shampoo on for 5 minutes before rinsing. One study alluded to this communication gap, revealing physicians’ tendency to overestimate how effectively they are communicating with their patients.3

Successful patient education ultimately is dependent on both the content provided and the method of delivery. In one survey of 2636 Internet users, 72% of respondents admitted to searching online for health information within the previous year; however, the same survey showed that physicians remain patients’ most trusted source of information.4 Physicians can use digital education methods to fulfill patient needs by providing them with and directing them to credible up-to-date sources.

Physicians can use electronic medical record (EMR) systems to electronically deliver health information to patients by directly communicating via an online patient portal. Allowing patients to engage with their health care providers electronically has been shown to increase patient satisfaction, promote adherence to preventative and treatment recommendations, improve clinical outcomes, and lower medical costs.5 The online portal can provide direct links for patients to digital resources; for example, MedlinePlus Connect (https://medlineplus.gov/connect/overview.html) is a free service that connects patients to MedlinePlus, an authoritative, up-to-date health information resource for consumer health information; however, many EMR systems lack quality dermatology content, as there is a greater emphasis on primary care, and patient usage of these online portals also is notoriously low.6 Dermatologists can work with EMR vendors to enhance the dermatology content for patient portals, and in some cases, specialty-specific content may be available for an additional fee. Clinicians can make their patients aware of the online portal and incentivize its use by sending an informational email, including a link on their practice’s website, promoting the portal during check-in and check-out at office visits, making tablets or kiosks available in the waiting room for sign-up, hanging posters in the examination rooms, and explaining the portal’s useful features during consultations with patients.

Mobile apps have revolutionized the potential for dermatologists to streamline patient education to a large population. In a 2014 review of 365 dermatology mobile apps, 13% were categorized as educational aids, adding to the realm of possibilities for digital patient education. For example, these apps may provide information on specific dermatologic conditions and medications, help users perform skin cancer checks, and provide reminders for when to administer injections for those on biologics. However, a drawback of medical mobile apps is that, to date, the US Food and Drug Administration has not released formal guidelines for their development.

It would be impractical for busy dermatologists to keep up with the credibility of every mobile app available in a growing market, but one solution could be for physicians to stay informed on only the most popular and most reviewed apps to keep in their digital toolbox. In 2014, the most reviewed dermatology app was the Dermatology app, which provided a guide to common dermatologic conditions and included images and a list of symptoms.7 To help keep physicians up to date on the most reliable dermatology apps, specialty societies, journal task forces, or interested dermatologists, residents, or medical students could publish updated literature on the most popular and most reviewed dermatology apps for patient education annually or biannually.

A practice’s website is a prime place for physicians to direct patients to educational content. Although many dermatology practice websites offer clinical information, the content often is focused on cosmetic procedures or is designed for search engine optimization to support online marketing and therefore may not be helpful to patients trying to understand a specific condition or treatment. Links to trusted resources, such as dermatology journals or medical societies, may be added but also would direct patients away from the practice’s website and would not allow physicians to customize the information he or she would like to share with their patients. Dermatologists should consider investing time and money into customizing educational material for their websites so patients can access health information from the source they trust most: their own physician.

Many of these digital options are useful for patients who want to access education material outside of the physician’s office, but digital opportunities to enhance point-of-care education also are available. In 2016, the American Academy of Dermatology partnered with ContextMedia:Health with the goal of delivering important decision enhancement technologies, educational content, and intelligence to patients and dermatologists for use before and during the consultation.8 ContextMedia:Health’s digital wallboard tablets are an engaging way to visually explain conditions and treatments to patients during the consultation, thus empowering physicians and patients to make decisions together and helping patients to be better advocates of their own health care. The downside is that health care workers must devote time and resources to be trained in using these devices.

The increasing availability of technology for electronic health information can be both beneficial and challenging for dermatologists. Physicians should explore and familiarize themselves with the tools that are available and assess their effectiveness by communicating with patients about their perception and understanding of their conditions. Digital delivery of health information is not meant to replace other methods of patient education but to supplement and reinforce them that which is verbally discussed during the office visit. Electronic health education demonstrates powerful potential, but it is up to the physician to direct patients to the appropriate resources and educational tools that will support a clear understanding of all elements of care.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Becker (Berkeley, California) for helpful discussion and reviewing this manuscript.

- Explosive growth in healthcare apps raises oversight questions. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- What’s MACRA? Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Updated November 16, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495-507.

- Dutta-Bergman M. Trusted online sources of health information: differences in demographics, health beliefs, and health-information orientation [published online September 25, 2003]. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5:E21.

- Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, et al. Patient portals: who uses them? what features do they use? and do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7:489-501.

- Lin CT, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, et al. An internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:E47.

- Patel S, Eluri M, Boyers LN, et al. Update on mobile applications in dermatology [published online November 9, 2014]. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21. pii:13030/qt1zc343js.

- American Academy of Dermatology selects ContextMedia:Health as patient education affinity partner. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-selects-patient-education-affinity-partner. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed February 25, 2018.

- Explosive growth in healthcare apps raises oversight questions. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- What’s MACRA? Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Updated November 16, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495-507.

- Dutta-Bergman M. Trusted online sources of health information: differences in demographics, health beliefs, and health-information orientation [published online September 25, 2003]. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5:E21.

- Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, et al. Patient portals: who uses them? what features do they use? and do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7:489-501.

- Lin CT, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, et al. An internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:E47.

- Patel S, Eluri M, Boyers LN, et al. Update on mobile applications in dermatology [published online November 9, 2014]. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21. pii:13030/qt1zc343js.

- American Academy of Dermatology selects ContextMedia:Health as patient education affinity partner. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-selects-patient-education-affinity-partner. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed February 25, 2018.