User login

White Spots on the Extremities

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

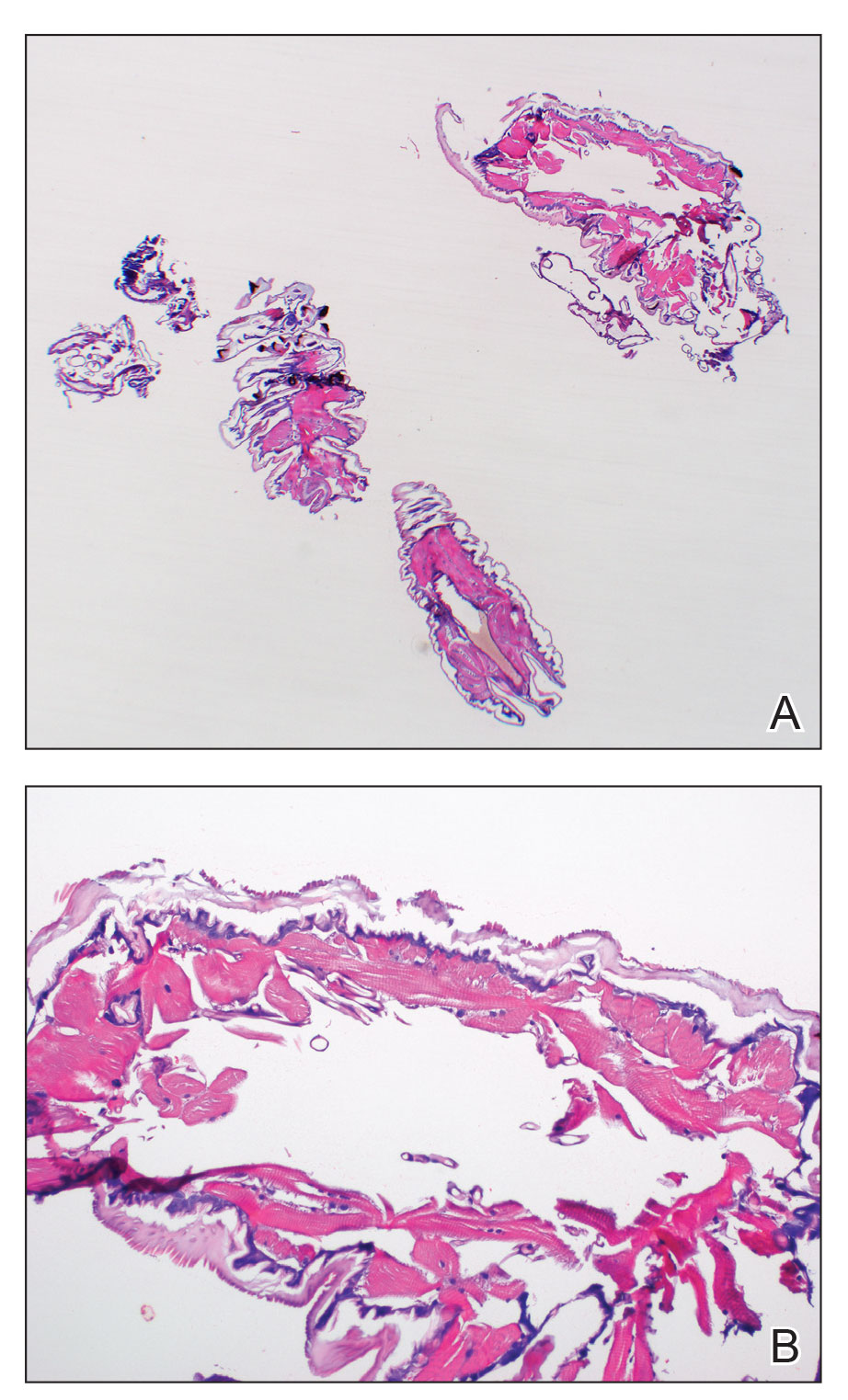

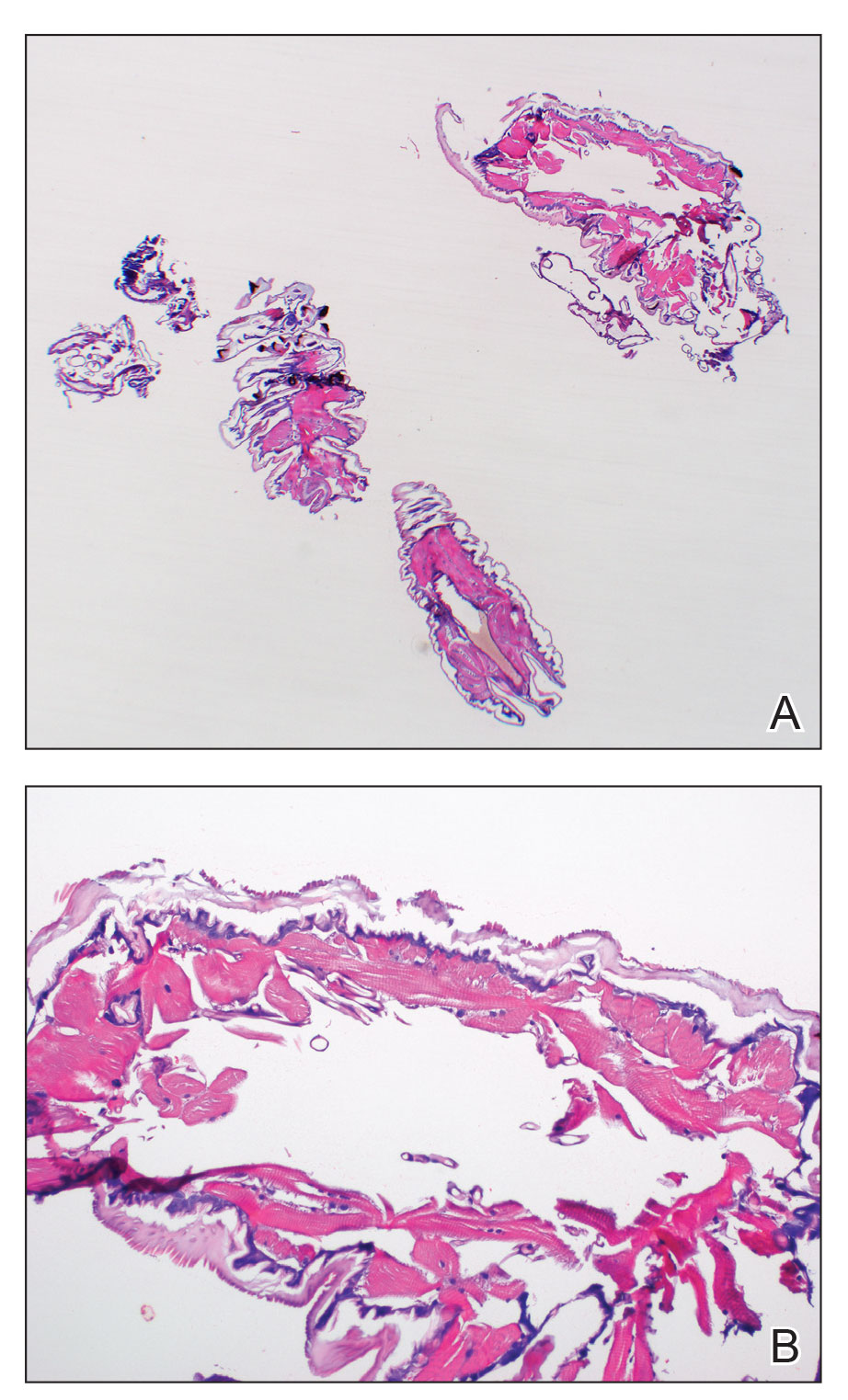

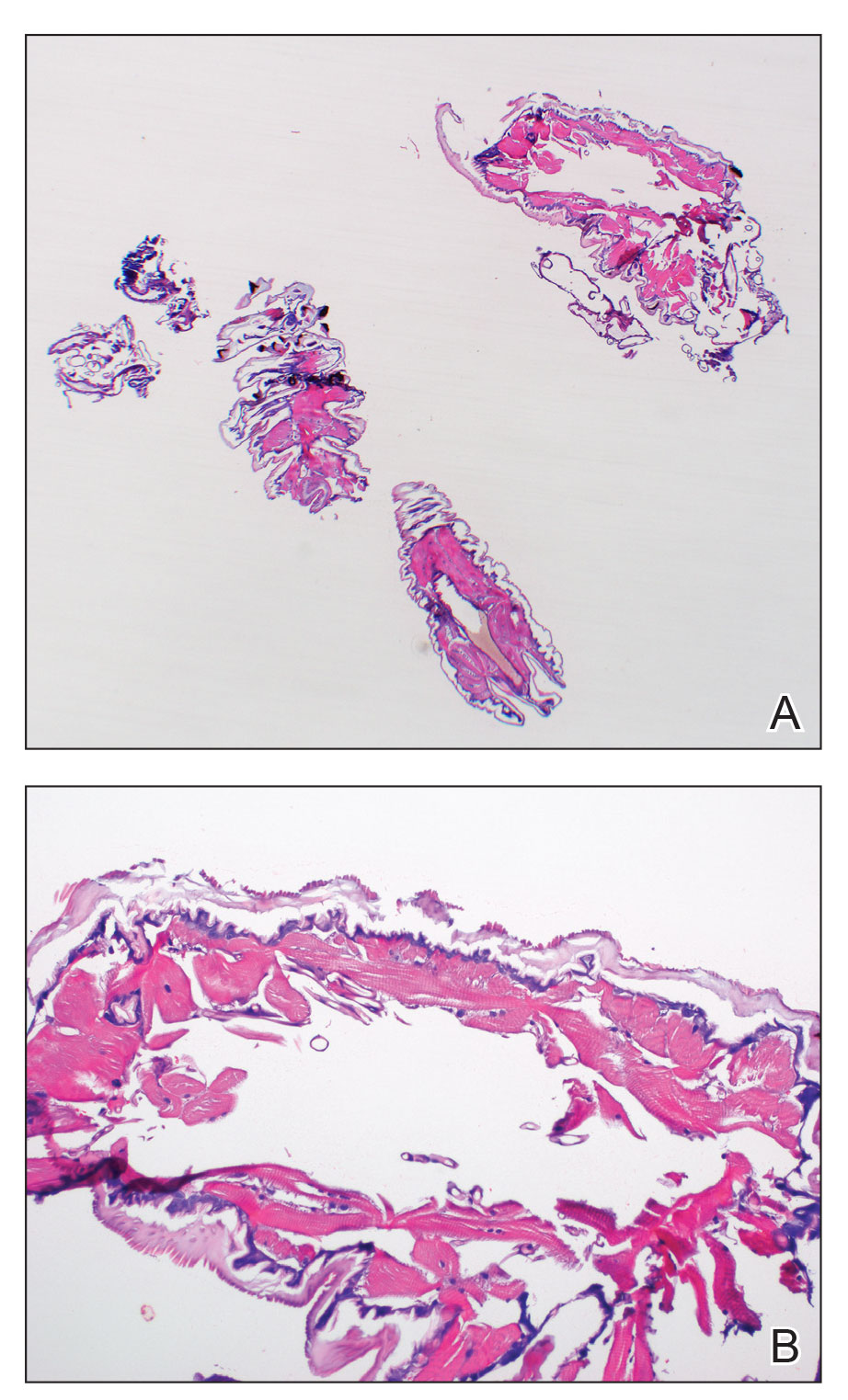

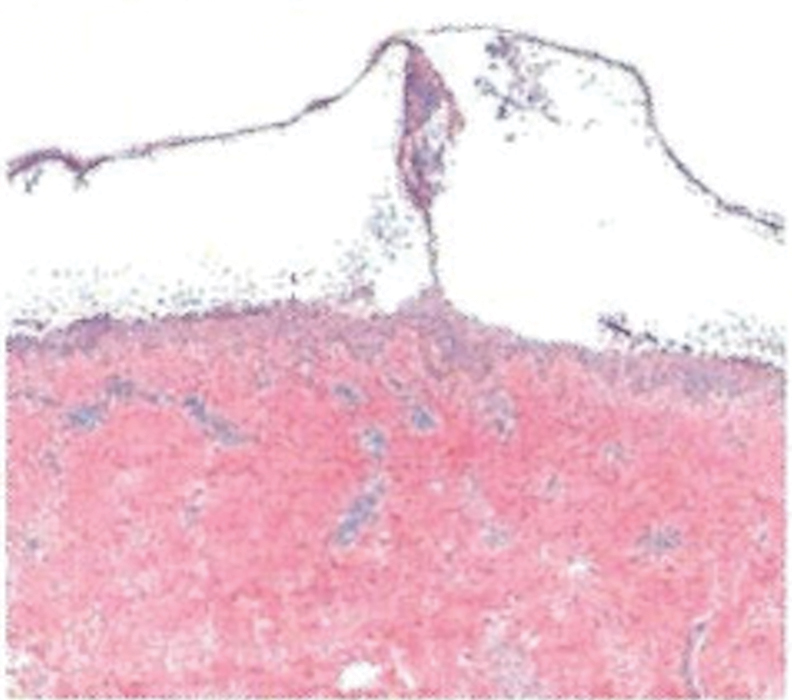

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

A 52-year-old Black woman presented with self-described whitened spots on the arms and legs of 2 years’ duration. She experienced no improvement with ketoconazole cream and topical calcineurin inhibitors prescribed during a prior dermatology visit at an outside institution. She denied pain or pruritus. A review of systems as well as the patient’s medical history were noncontributory. A prior biopsy at an outside institution revealed an interface dermatitis suggestive of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The patient noted social drinking and denied tobacco use. She had no known allergies to medications and currently was on tamoxifen for breast cancer following a right mastectomy. Physical examination showed hypopigmented macules and patches on the left upper arm and right proximal leg. The center of the lesions was not erythematous or scaly. Palpation did not reveal enlarged lymph nodes, and laboratory analyses ruled out low levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Punch biopsies from the left arm and right thigh were performed.

Painful Nodules With a Crawling Sensation

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

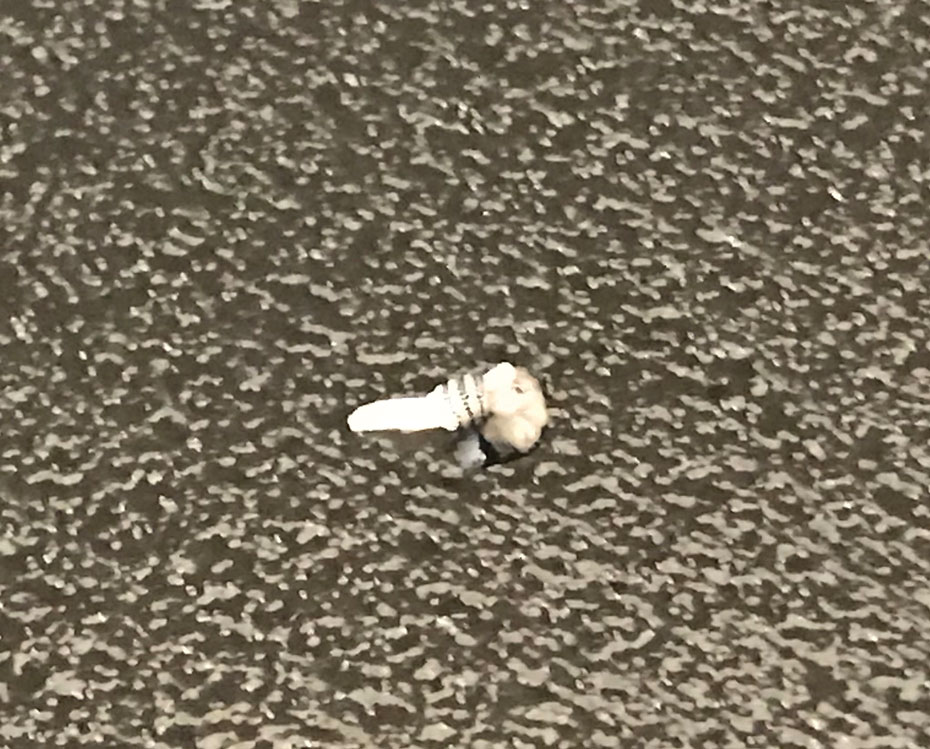

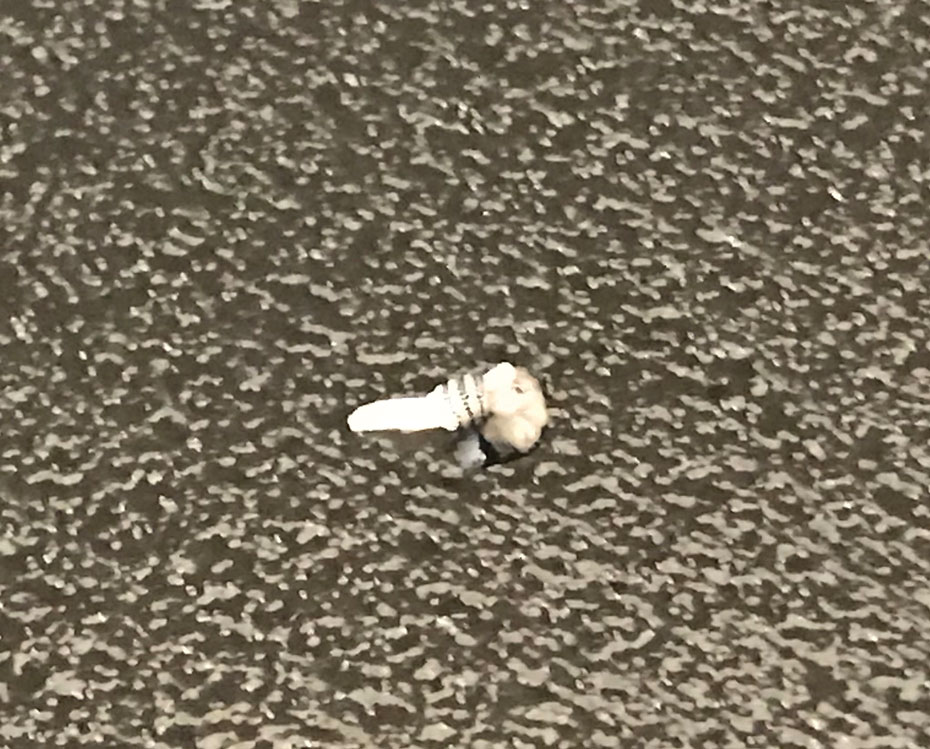

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

A 20-year-old man presented with progressively enlarging, painful lesions on the arm with a crawling sensation of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions appeared after a recent trip to Brazil where he was hiking in the Amazon. He noted that the pain occurred suddenly and there was some serous drainage from the lesions. He denied any trauma to the area and reported no history of similar eruptions, treatments, or systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed 2 tender erythematous nodules, each measuring 0.6 cm in diameter, with associated crust and a reported crawling sensation on the posterior aspect of the left arm. No drainage was seen. A punch biopsy was performed.

Painful and Pruritic Eruptions on the Entire Body

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

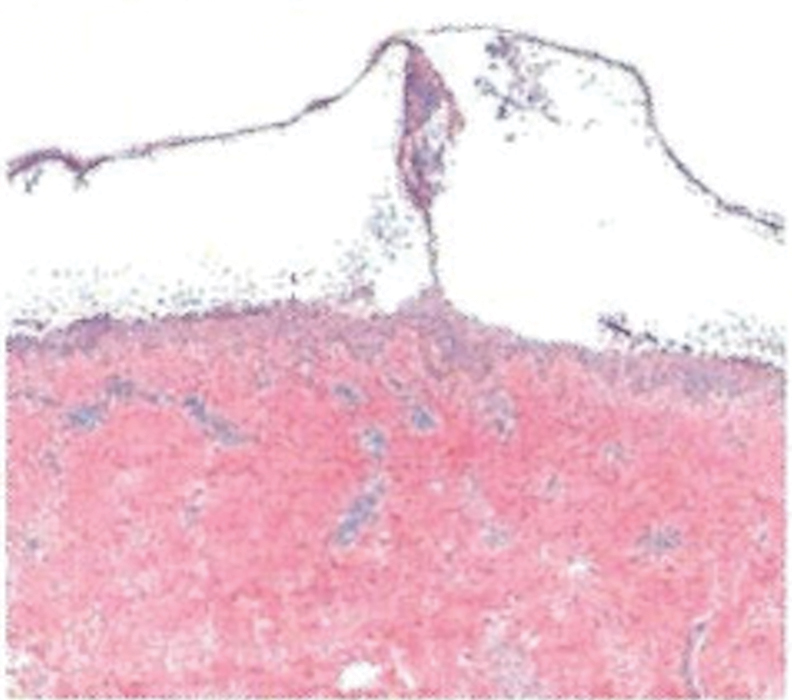

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

A 36-year-old man presented with painful tender blisters and rashes on the entire body, including the ears and tongue. The rash began as a few pinpointed red dots on the abdomen, which subsequently increased in size and spread over the last week. He initially felt red and flushed and noticed new lesions appearing throughout the day. He did not attempt any specific treatment for these lesions. The patient tested positive for COVID-19 four months prior to the skin eruption. He denied systemic symptoms, smoking, or recent travel. He had no history of skin cancer, skin disorders, HIV, or hepatitis. He had no known medication allergies. Physical examination revealed multiple disseminated pustules on the ears, superficial ulcerations on the tongue, and blisters on the right lip. Few lesions were tender to the touch and drained clear fluid. Bacterial, viral, HIV, herpes, and rapid plasma reagin culture and laboratory screenings were negative. He was started on valaciclovir and cephalexin; however, no improvement was noticed. Punch biopsies were taken from the blisters on the chest and perilesional area.

Pediatric Subungual Exostosis

Exostosis is a type of benign bone tumor in which trabecular (spongy) bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. 1,2 Histologically, it usually is surrounded by a fibrocartilaginous cap. 3 It is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the foot and is thought to be caused by trauma, either physical pressure or infection. 4 When this lesion is found under the nail bed, it is termed subungual exostosis ( Dupuytren exostosis ) . 3 Sequelae of a subungual exostosis include nail dystrophy and lifting of the nail away from the toe, in addition to infection and possible loss of the toenail (onycholysis). There are only 2 genetic conditions related to exostosis: hereditary multiple exostosis and multiple exostoses-mental retardation syndrome.

An exostosis may appear to be a wart on first inspection. It may present similar to osteochondromas, and the only way to get a true diagnosis is by biopsy of the lesion. The treatment for an exostosis is surgery. The surgeon must remove the lesion at the base of the bone from which it grows to prevent recurrence of the lesion.5

Because exostosis may cause nail bed disruption, the differential diagnosis may include nail deformities, such as traumatic onycholysis, onychogryphosis, verrucae, subungual infection, or nail trauma.6,7

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy presented with changes of the right great toenail over the last 4 months. The patient noted that the affected nail was discolored, dystrophic, painful, and thickened. He did not recall prior trauma to the affected nail, and his mother stated that the lesion was growing and becoming more painful with a throbbing sensation at times. He described the pain as stabbing, which was exacerbated while walking and playing sports. Neither the patient nor his family had ever had any similar condition. He was not taking any medications, only a daily multivitamin. He had a history of eczematous dermatitis and keratosis pilaris without any other medical illnesses. He had a family history of psoriasis; however, no prior instances of exostosis had been reported. He had no medication allergies.

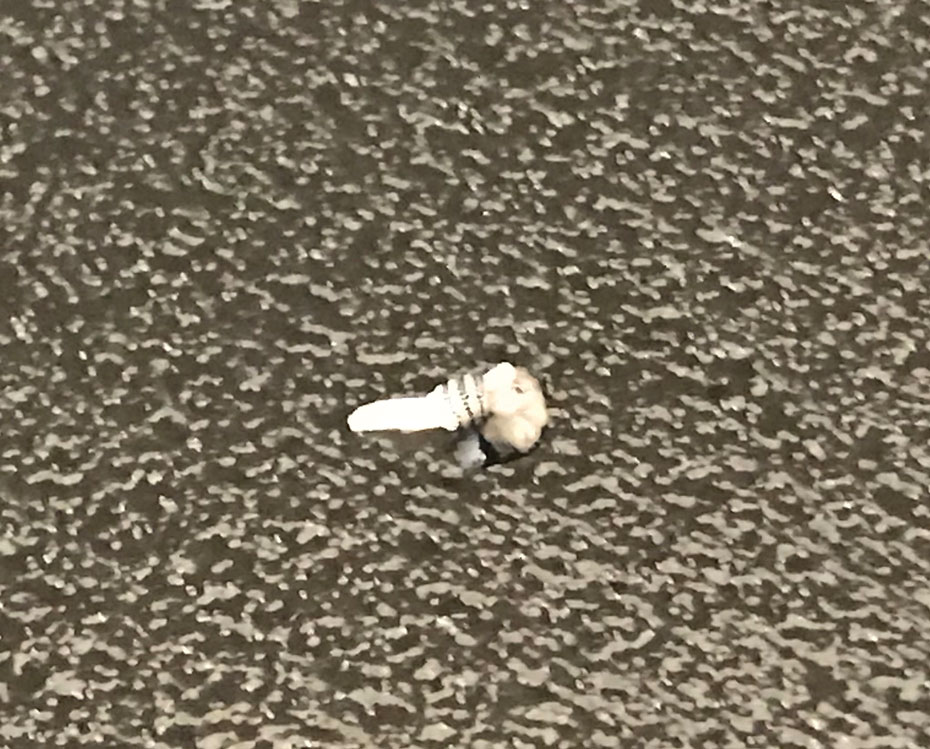

A full-body cutaneous and nail examination showed a well-developed, well-nourished boy who was in no acute distress. A firm, subungual, pink, pearly,hyperkeratotic nodule was appreciated on the right great toe (Figure 1). The lesion was tender to palpation. The rest of the examination and review of systems were normal.

From the clinical findings, a differential diagnosis of glomus tumor, hemangioma, and infection was considered. Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative, which ruled out fungal infection. Nail avulsion and a shave biopsy were performed under general anesthesia. There was an exostosis arising from the dorsal aspect of the great toe measuring approximately 5 mm in width at the base and approximately 1 mm in height, which endorsed a diagnosis of distal phalanx subungual exostosis. A postsurgery radiograph (Figure 2) showed residual bone below the level of shave removal at the nail bed.

Comment

Exostosis is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the hallux (great toe) in patients younger than 18 years.8 Diagnosis often is obvious, even without a radiograph or biopsy, because the exostosis comes out from under the tip of the nail. Our case was interesting because the patient was a child, and the exostosis did not lift the nail or extrude from the distal tip of the nail bed. Evidence suggests that a greater-than-expected genetic influence contributes to an exostosis, though further investigation is needed to determine all of the causes and risk factors for subungual bony exostosis. Timely diagnosis and treatment are essential to the prevention of sequelae of the disease, such as toe infection or chronic pain.

- de Palma L, Gigante A, Specchia N. Subungual exostosis of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:758-763. doi:10.1177/107110079601701208

- Multhopp-Stephens H, Walling AK. Subungual (Dupuytren’s) exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:582-584. doi:10.1097/01241398-199509000-00006

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Subungual exostosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:212-218.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Risitano G, et al. Solitary asymptomatic nodule of the great toe. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:245-247.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Hoy NY, Leung AKC, Metelitsa AI, et al. New concepts in median nail dystrophy, onychomycosis, and hand, foot, and mouth disease nail pathology. ISRN Dermatol. 2012;2012:680163.

- Rich P, Scher RK. Examination of the nail and work-up of nail conditions. In: Rich P, Scher RK, eds. An Atlas of Diseases of the Nail. Parthenon Publishing; 2003.

- DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

Exostosis is a type of benign bone tumor in which trabecular (spongy) bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. 1,2 Histologically, it usually is surrounded by a fibrocartilaginous cap. 3 It is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the foot and is thought to be caused by trauma, either physical pressure or infection. 4 When this lesion is found under the nail bed, it is termed subungual exostosis ( Dupuytren exostosis ) . 3 Sequelae of a subungual exostosis include nail dystrophy and lifting of the nail away from the toe, in addition to infection and possible loss of the toenail (onycholysis). There are only 2 genetic conditions related to exostosis: hereditary multiple exostosis and multiple exostoses-mental retardation syndrome.

An exostosis may appear to be a wart on first inspection. It may present similar to osteochondromas, and the only way to get a true diagnosis is by biopsy of the lesion. The treatment for an exostosis is surgery. The surgeon must remove the lesion at the base of the bone from which it grows to prevent recurrence of the lesion.5

Because exostosis may cause nail bed disruption, the differential diagnosis may include nail deformities, such as traumatic onycholysis, onychogryphosis, verrucae, subungual infection, or nail trauma.6,7

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy presented with changes of the right great toenail over the last 4 months. The patient noted that the affected nail was discolored, dystrophic, painful, and thickened. He did not recall prior trauma to the affected nail, and his mother stated that the lesion was growing and becoming more painful with a throbbing sensation at times. He described the pain as stabbing, which was exacerbated while walking and playing sports. Neither the patient nor his family had ever had any similar condition. He was not taking any medications, only a daily multivitamin. He had a history of eczematous dermatitis and keratosis pilaris without any other medical illnesses. He had a family history of psoriasis; however, no prior instances of exostosis had been reported. He had no medication allergies.

A full-body cutaneous and nail examination showed a well-developed, well-nourished boy who was in no acute distress. A firm, subungual, pink, pearly,hyperkeratotic nodule was appreciated on the right great toe (Figure 1). The lesion was tender to palpation. The rest of the examination and review of systems were normal.

From the clinical findings, a differential diagnosis of glomus tumor, hemangioma, and infection was considered. Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative, which ruled out fungal infection. Nail avulsion and a shave biopsy were performed under general anesthesia. There was an exostosis arising from the dorsal aspect of the great toe measuring approximately 5 mm in width at the base and approximately 1 mm in height, which endorsed a diagnosis of distal phalanx subungual exostosis. A postsurgery radiograph (Figure 2) showed residual bone below the level of shave removal at the nail bed.

Comment

Exostosis is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the hallux (great toe) in patients younger than 18 years.8 Diagnosis often is obvious, even without a radiograph or biopsy, because the exostosis comes out from under the tip of the nail. Our case was interesting because the patient was a child, and the exostosis did not lift the nail or extrude from the distal tip of the nail bed. Evidence suggests that a greater-than-expected genetic influence contributes to an exostosis, though further investigation is needed to determine all of the causes and risk factors for subungual bony exostosis. Timely diagnosis and treatment are essential to the prevention of sequelae of the disease, such as toe infection or chronic pain.

Exostosis is a type of benign bone tumor in which trabecular (spongy) bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. 1,2 Histologically, it usually is surrounded by a fibrocartilaginous cap. 3 It is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the foot and is thought to be caused by trauma, either physical pressure or infection. 4 When this lesion is found under the nail bed, it is termed subungual exostosis ( Dupuytren exostosis ) . 3 Sequelae of a subungual exostosis include nail dystrophy and lifting of the nail away from the toe, in addition to infection and possible loss of the toenail (onycholysis). There are only 2 genetic conditions related to exostosis: hereditary multiple exostosis and multiple exostoses-mental retardation syndrome.

An exostosis may appear to be a wart on first inspection. It may present similar to osteochondromas, and the only way to get a true diagnosis is by biopsy of the lesion. The treatment for an exostosis is surgery. The surgeon must remove the lesion at the base of the bone from which it grows to prevent recurrence of the lesion.5

Because exostosis may cause nail bed disruption, the differential diagnosis may include nail deformities, such as traumatic onycholysis, onychogryphosis, verrucae, subungual infection, or nail trauma.6,7

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy presented with changes of the right great toenail over the last 4 months. The patient noted that the affected nail was discolored, dystrophic, painful, and thickened. He did not recall prior trauma to the affected nail, and his mother stated that the lesion was growing and becoming more painful with a throbbing sensation at times. He described the pain as stabbing, which was exacerbated while walking and playing sports. Neither the patient nor his family had ever had any similar condition. He was not taking any medications, only a daily multivitamin. He had a history of eczematous dermatitis and keratosis pilaris without any other medical illnesses. He had a family history of psoriasis; however, no prior instances of exostosis had been reported. He had no medication allergies.

A full-body cutaneous and nail examination showed a well-developed, well-nourished boy who was in no acute distress. A firm, subungual, pink, pearly,hyperkeratotic nodule was appreciated on the right great toe (Figure 1). The lesion was tender to palpation. The rest of the examination and review of systems were normal.

From the clinical findings, a differential diagnosis of glomus tumor, hemangioma, and infection was considered. Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative, which ruled out fungal infection. Nail avulsion and a shave biopsy were performed under general anesthesia. There was an exostosis arising from the dorsal aspect of the great toe measuring approximately 5 mm in width at the base and approximately 1 mm in height, which endorsed a diagnosis of distal phalanx subungual exostosis. A postsurgery radiograph (Figure 2) showed residual bone below the level of shave removal at the nail bed.

Comment

Exostosis is most commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the hallux (great toe) in patients younger than 18 years.8 Diagnosis often is obvious, even without a radiograph or biopsy, because the exostosis comes out from under the tip of the nail. Our case was interesting because the patient was a child, and the exostosis did not lift the nail or extrude from the distal tip of the nail bed. Evidence suggests that a greater-than-expected genetic influence contributes to an exostosis, though further investigation is needed to determine all of the causes and risk factors for subungual bony exostosis. Timely diagnosis and treatment are essential to the prevention of sequelae of the disease, such as toe infection or chronic pain.

- de Palma L, Gigante A, Specchia N. Subungual exostosis of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:758-763. doi:10.1177/107110079601701208

- Multhopp-Stephens H, Walling AK. Subungual (Dupuytren’s) exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:582-584. doi:10.1097/01241398-199509000-00006

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Subungual exostosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:212-218.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Risitano G, et al. Solitary asymptomatic nodule of the great toe. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:245-247.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Hoy NY, Leung AKC, Metelitsa AI, et al. New concepts in median nail dystrophy, onychomycosis, and hand, foot, and mouth disease nail pathology. ISRN Dermatol. 2012;2012:680163.

- Rich P, Scher RK. Examination of the nail and work-up of nail conditions. In: Rich P, Scher RK, eds. An Atlas of Diseases of the Nail. Parthenon Publishing; 2003.

- DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

- de Palma L, Gigante A, Specchia N. Subungual exostosis of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:758-763. doi:10.1177/107110079601701208

- Multhopp-Stephens H, Walling AK. Subungual (Dupuytren’s) exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:582-584. doi:10.1097/01241398-199509000-00006

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Subungual exostosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:212-218.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Risitano G, et al. Solitary asymptomatic nodule of the great toe. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:245-247.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Hoy NY, Leung AKC, Metelitsa AI, et al. New concepts in median nail dystrophy, onychomycosis, and hand, foot, and mouth disease nail pathology. ISRN Dermatol. 2012;2012:680163.

- Rich P, Scher RK. Examination of the nail and work-up of nail conditions. In: Rich P, Scher RK, eds. An Atlas of Diseases of the Nail. Parthenon Publishing; 2003.

- DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

Practice Points

- Nail dystrophy can have a variety of causes, most commonly trauma, onychomycosis, verrucae, or subungual exostosis.

- Exostosis is a benign osteochondral tumor commonly found on the lateral or medial aspect of the hallux (great toe) in pediatric and young adult patients.

- A radiograph can be used as a preliminary tool for diagnosis, but subungual exostosis must be confirmed by biopsy or tissue histology at the time of excision.