User login

Darkening and Eruptive Nevi During Treatment With Erlotinib

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

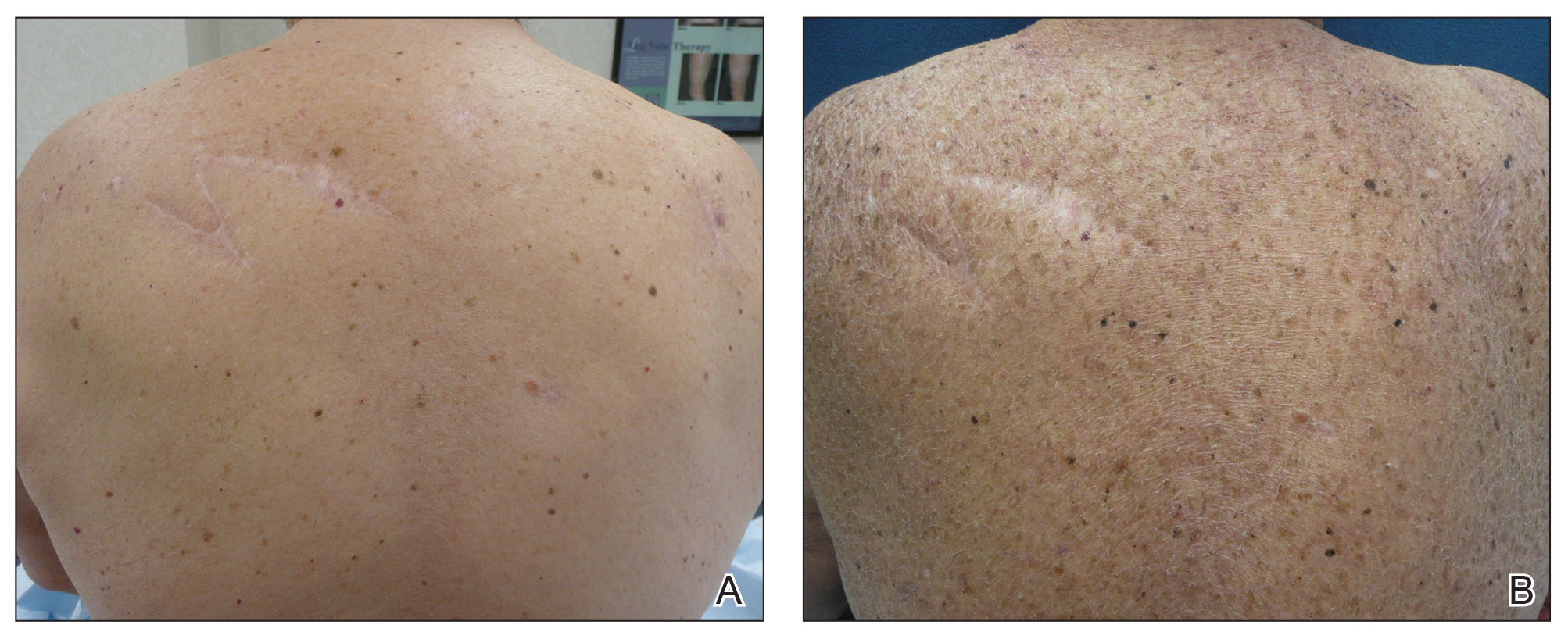

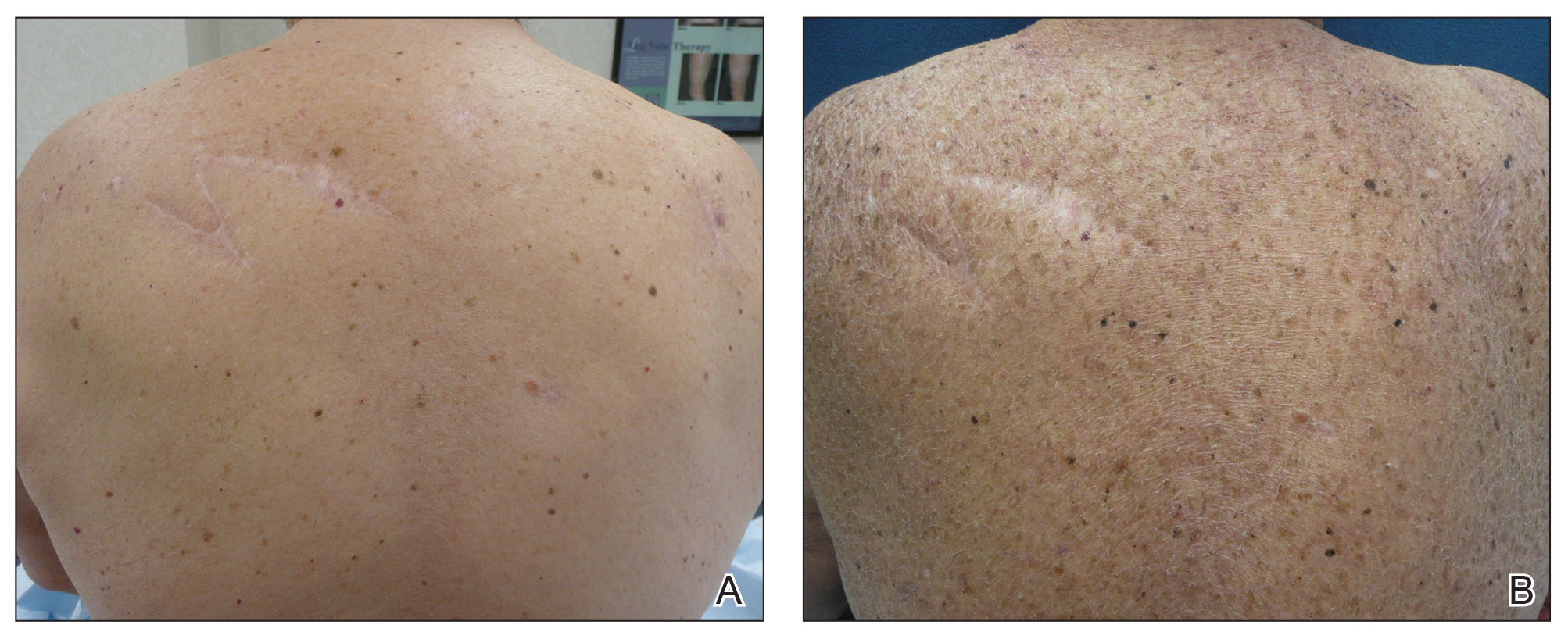

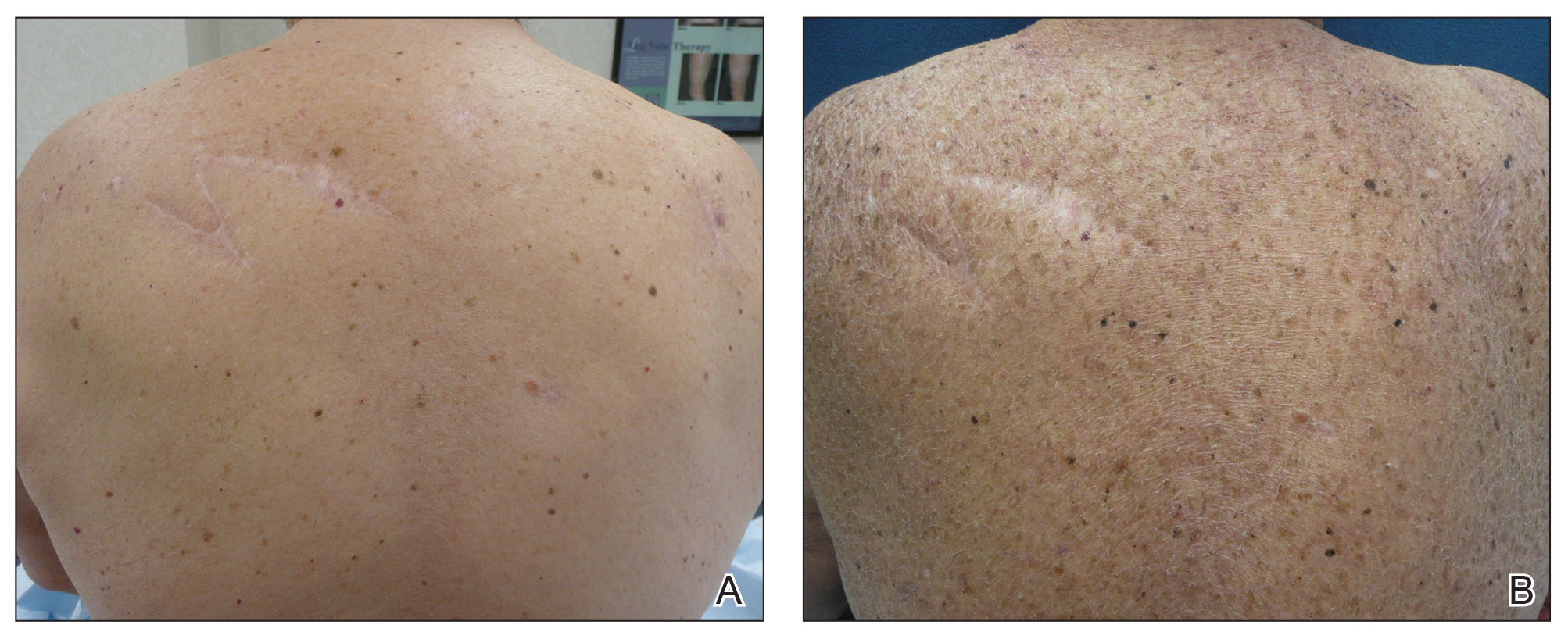

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

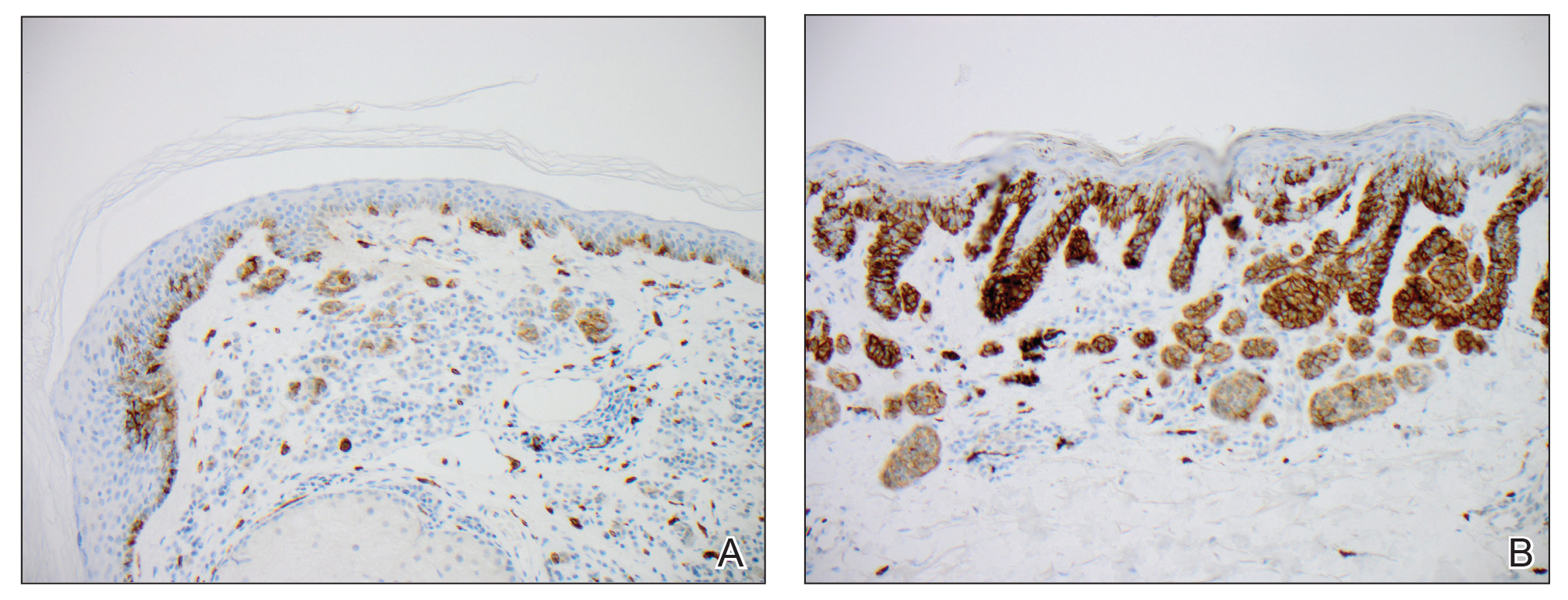

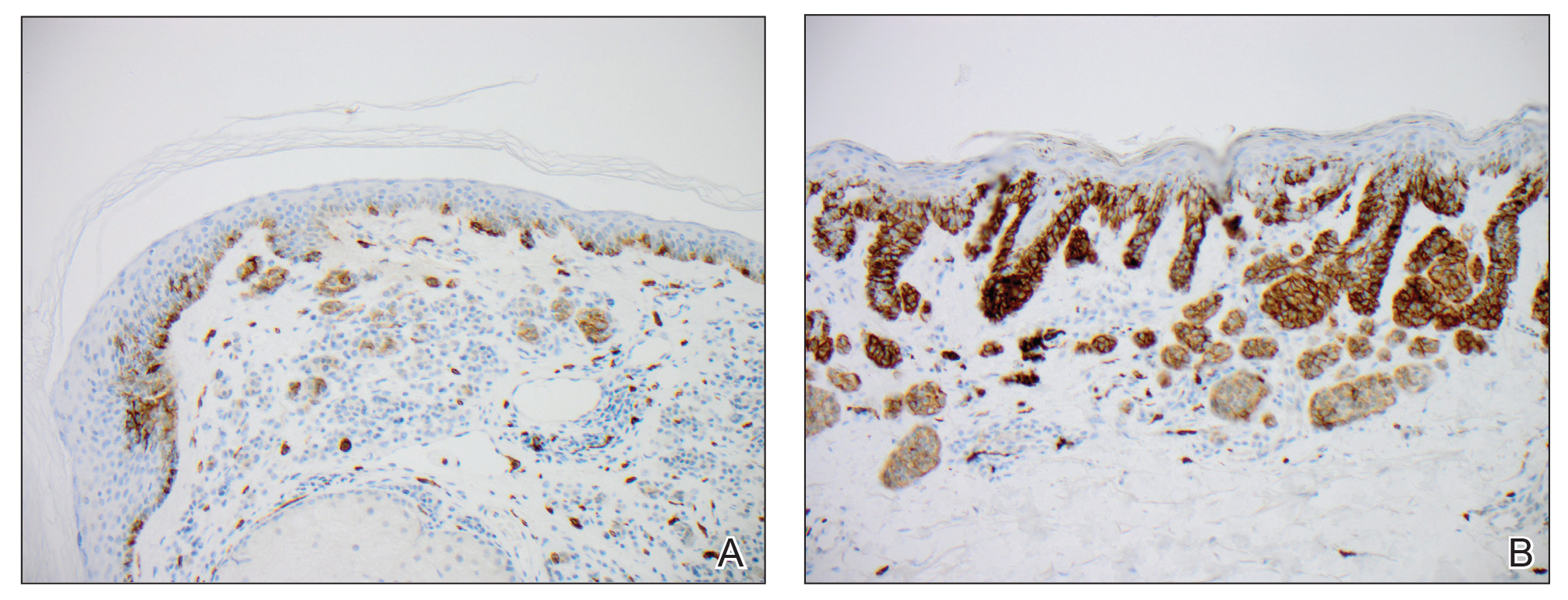

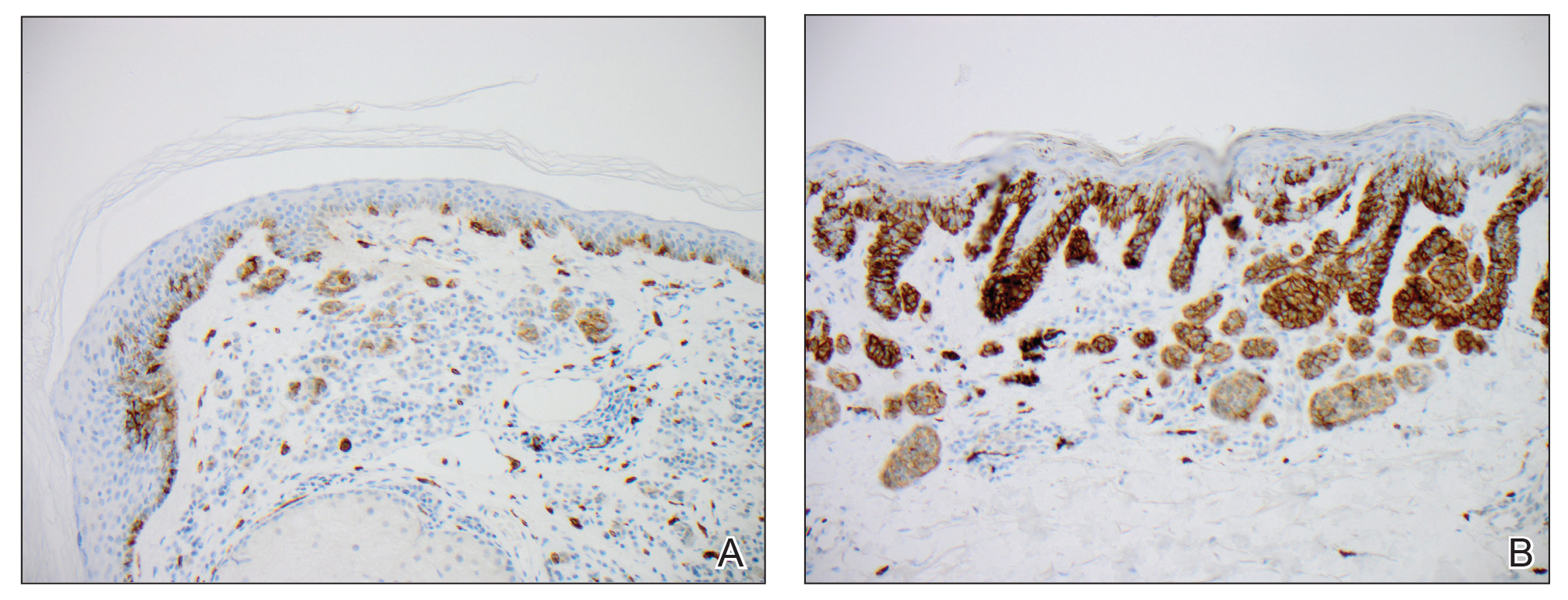

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous side effects of erlotinib include acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.

- Clinicians should monitor patients for darkening and/or eruptive nevi as well as melanoma during treatment with erlotinib.

Advanced-stage calciphylaxis: Think before you punch

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

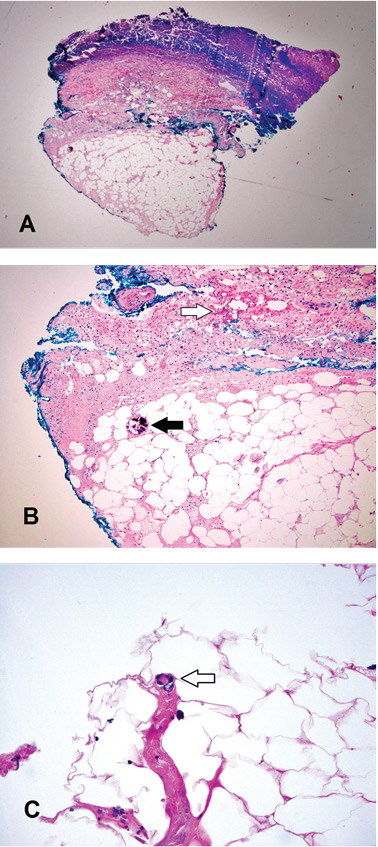

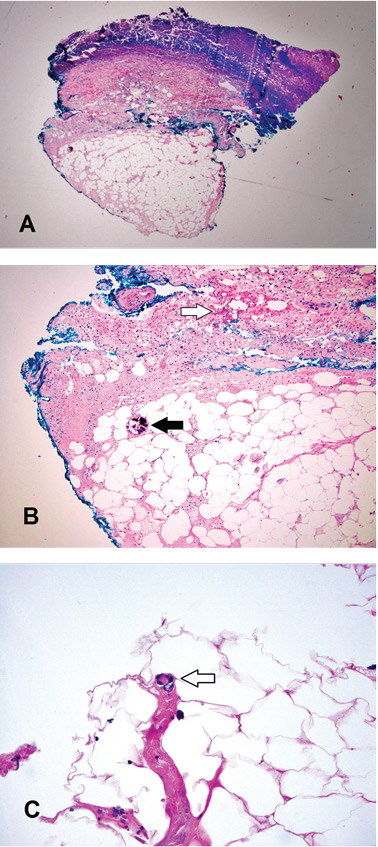

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

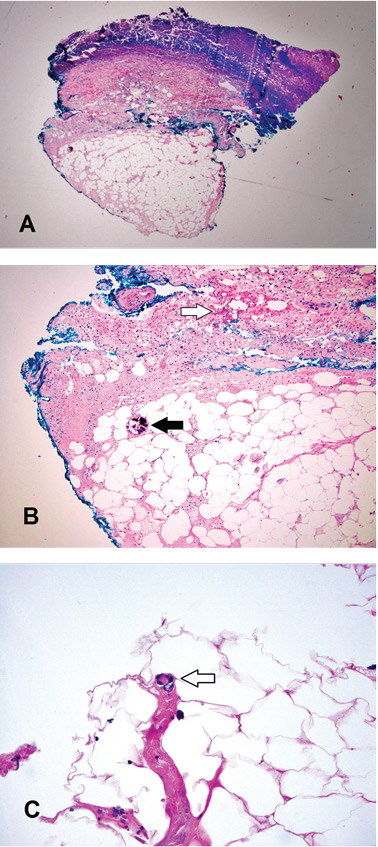

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.