User login

Norwegian scabies

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

Fournier gangrene

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

Palmoplantar exanthema and liver dysfunction

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

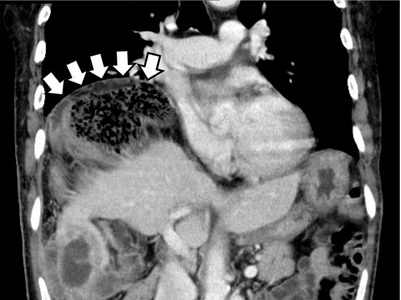

Gas under the right diaphragm

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.