User login

Subcorneal Hematomas in Excessive Video Game Play

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

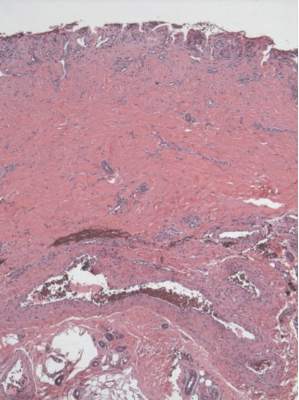

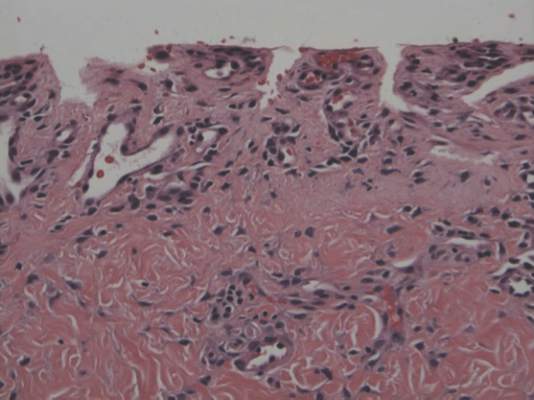

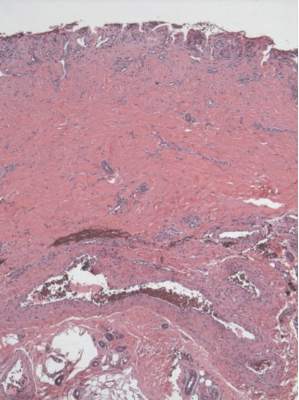

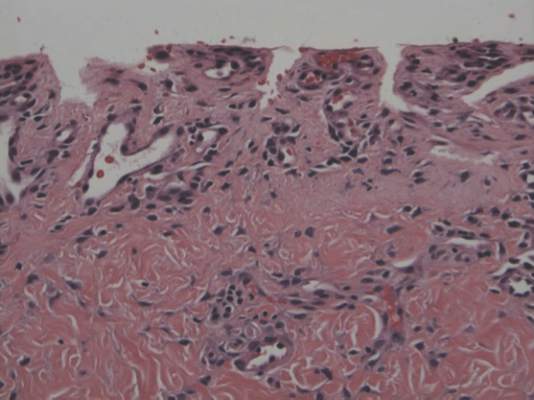

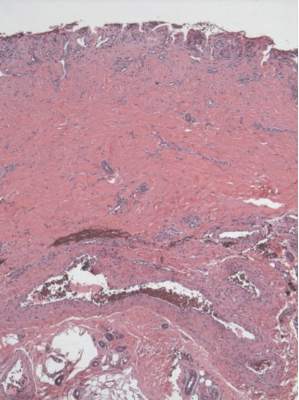

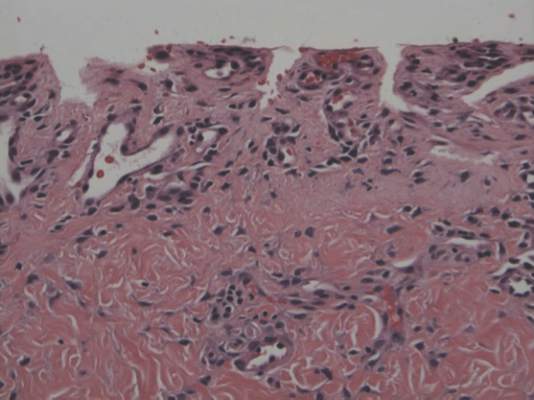

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

Practice Points

- Video game play has been reported as an etiologic factor in multiple musculoskeletal and dermatologic conditions.

- More than two-thirds of US children aged 2 to 18 years live in a home with a video game system.

- Cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

Painful Skin Lesions on the Hands Following Black Henna Application

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with painful skin lesions on the dorsal aspect of the hands of 10 days’ duration. She reported having received red henna tattoo on the palmar surface of the hands and black henna tattoo on the dorsal surface of the hands 1 day prior to development of the lesions. Within 1 day of receiving the tattoo, she developed pruritus, blisters, and pain on the dorsal aspect of the hands. The palms were unaffected. Physical examination revealed erythematous, brown to black bullae and crusts that followed the contours of the henna design on the dorsal aspect of the hands. There were orange and brown henna designs on the patient’s palms, but no erythema, bullae, or induration was noted.

Patchy hair loss on the scalp

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

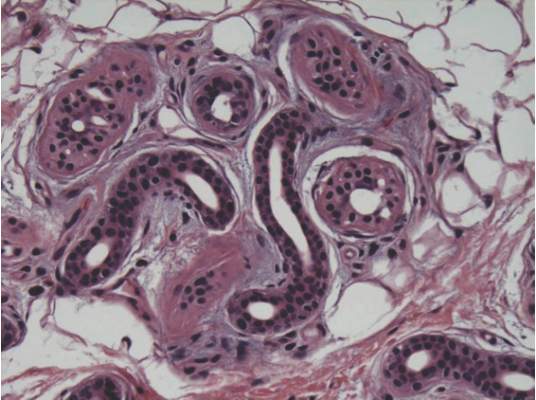

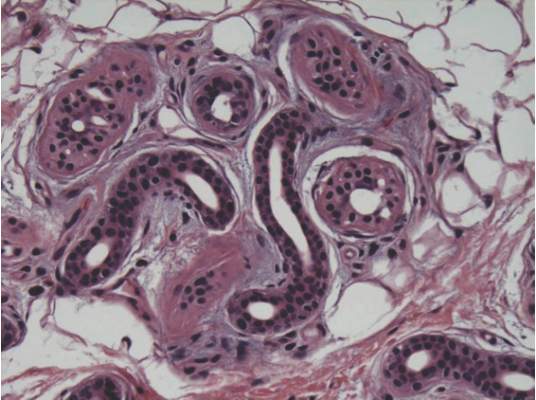

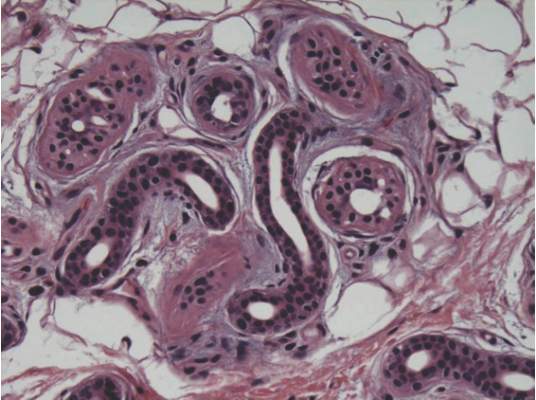

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.