User login

Painful Plaque on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

A 30-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the right forearm of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She reported working as a chef and caring for multiple pets in her home, including 3 cats, 6 fish tanks, 3 dogs, and 3 lizards. Physical examination revealed a painful, indurated, red-violaceous plaque on the right forearm with satellite pink nodules that had been slowly migrating proximally up the forearm. An outside excisional biopsy performed 1 year prior had shown suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms and negative tissue cultures. At that time, the patient was diagnosed with ruptured folliculitis; however, a subsequent lack of clinical improvement prompted her to seek a second opinion at our clinic.

Cutaneous Metastases From Esophageal Adenocarcinoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

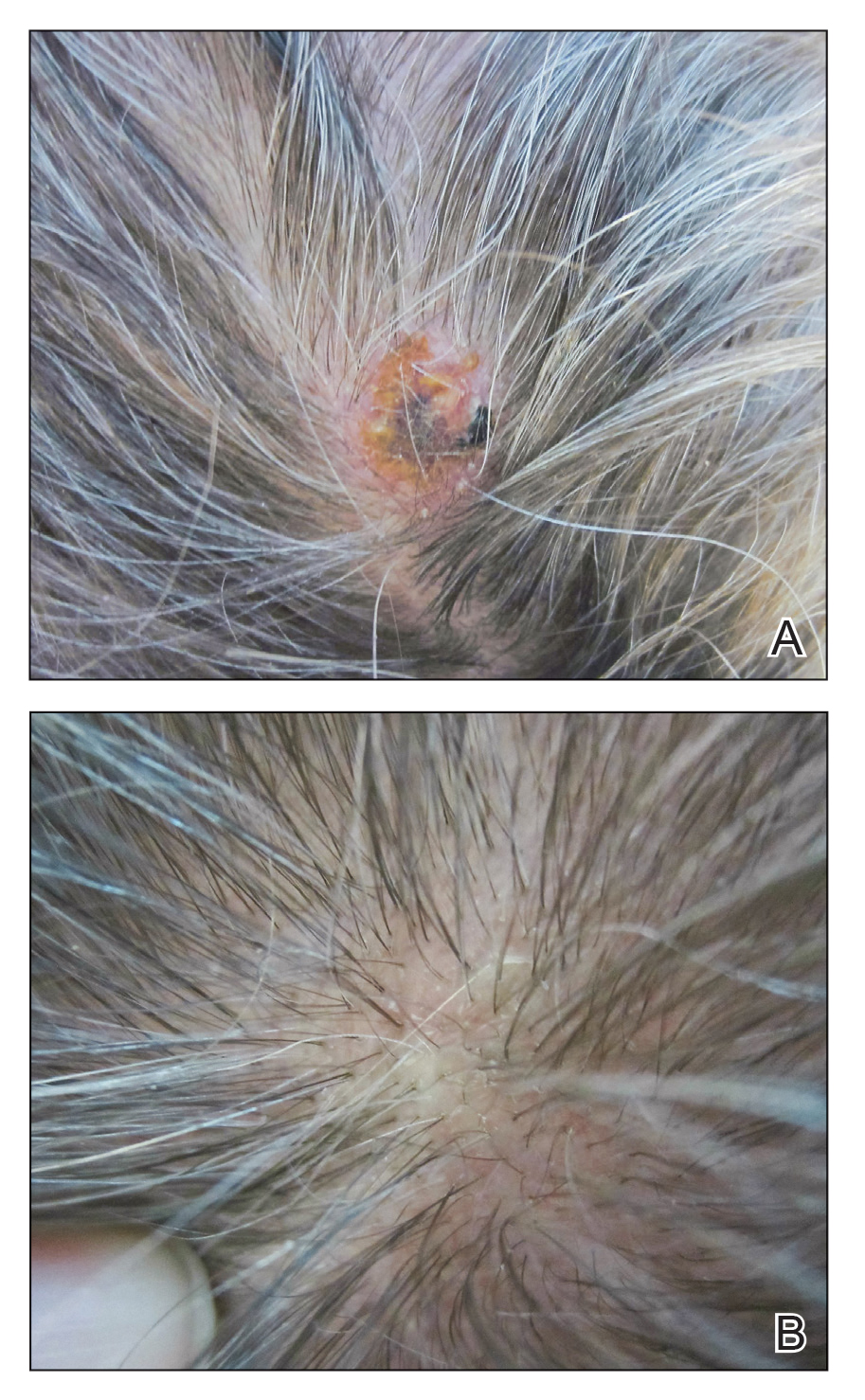

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

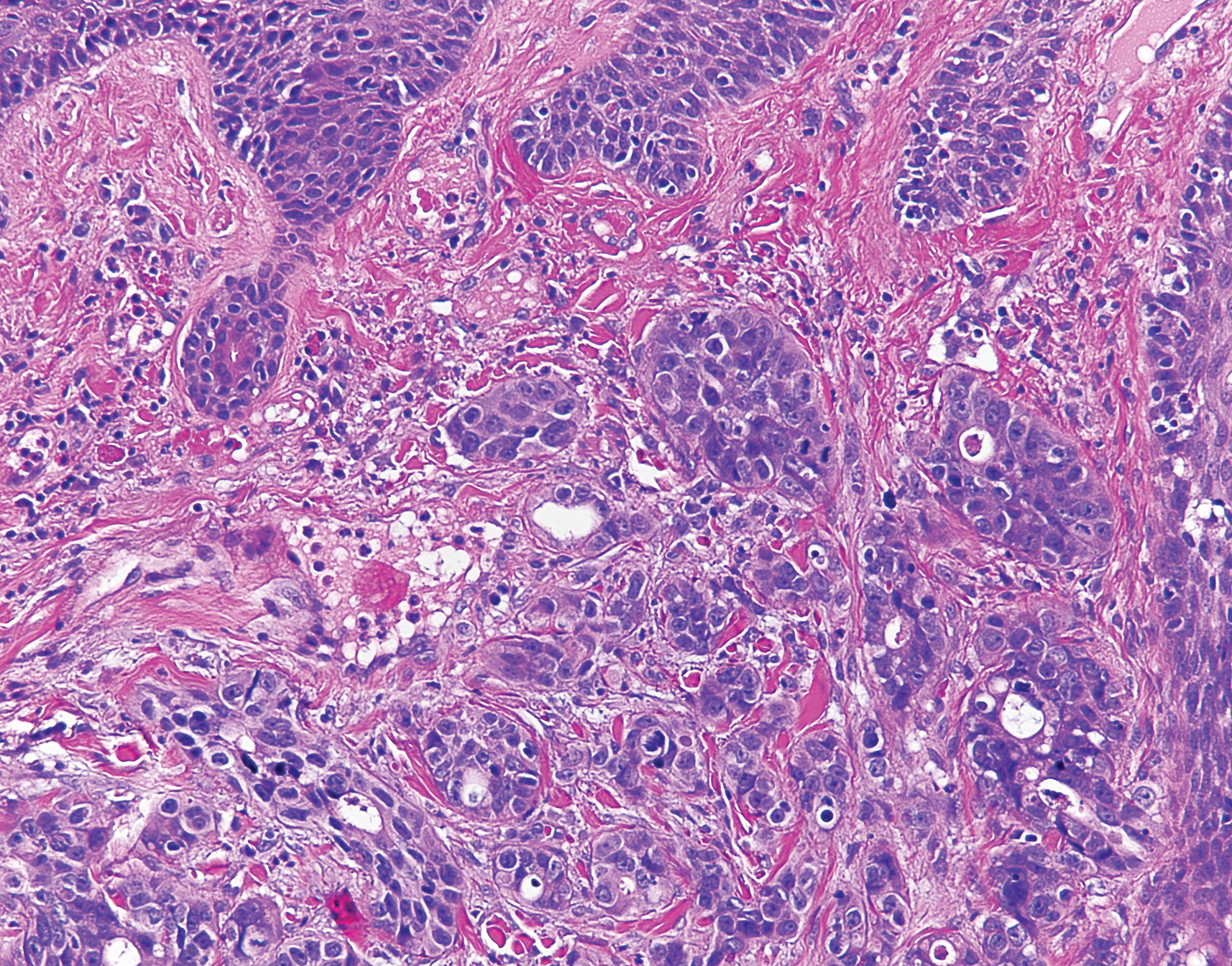

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

Practice Points

- In the setting of underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma, metastatic spread to the scalp should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any suspicious scalp lesions.

- Coupling histopathology with immunohistochemical stains may aid in the diagnosis for cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma.