User login

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Successfully Treated With Miltefosine

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

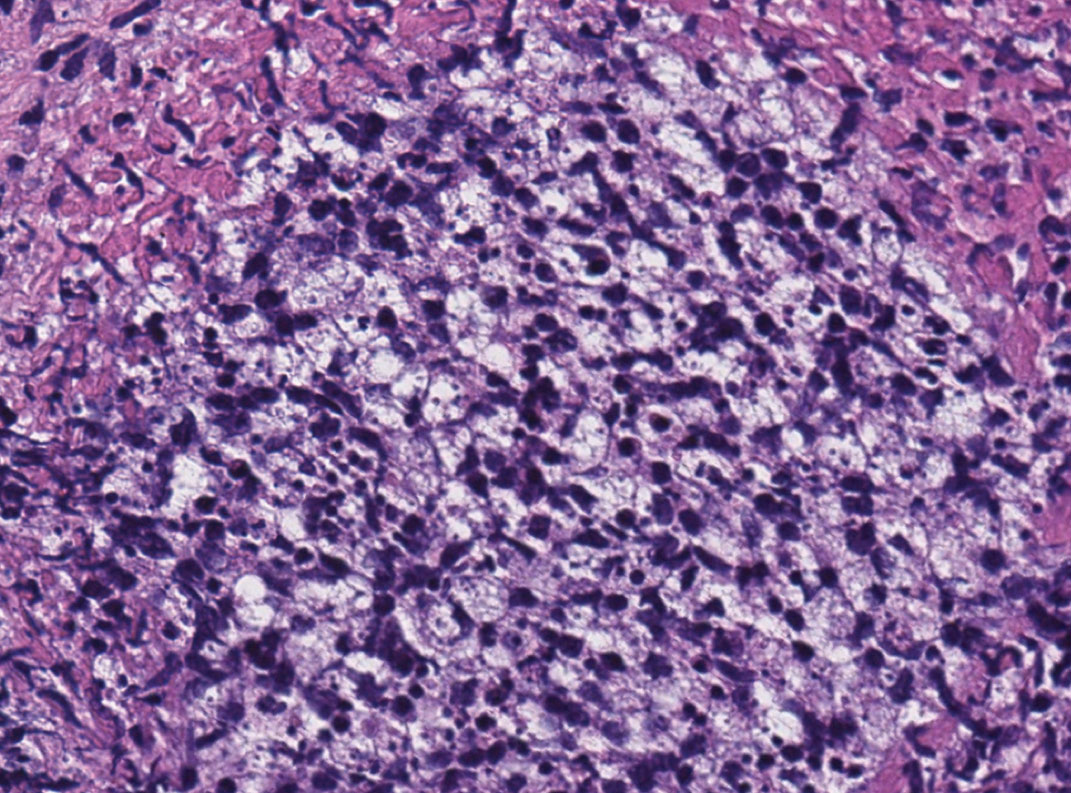

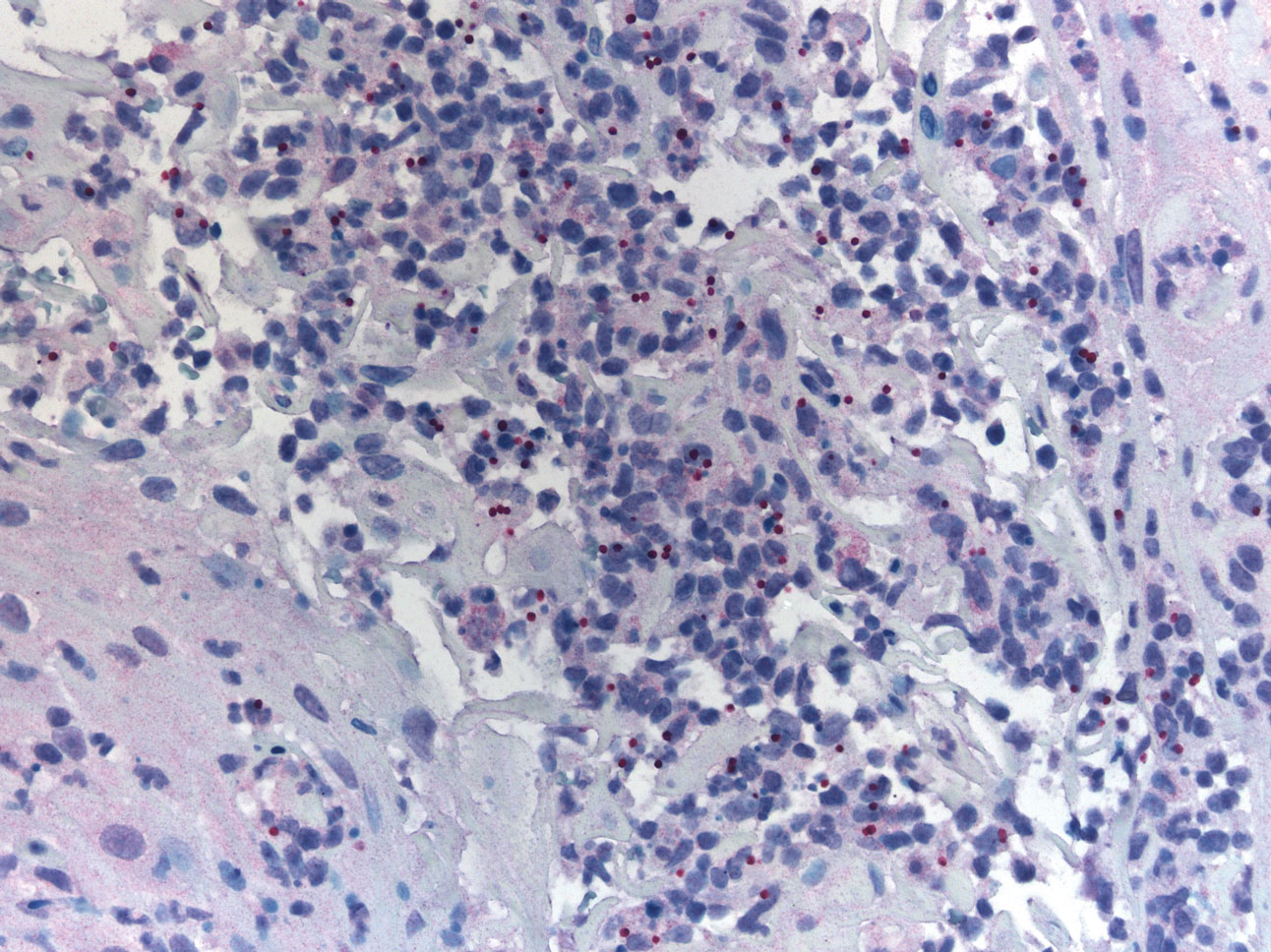

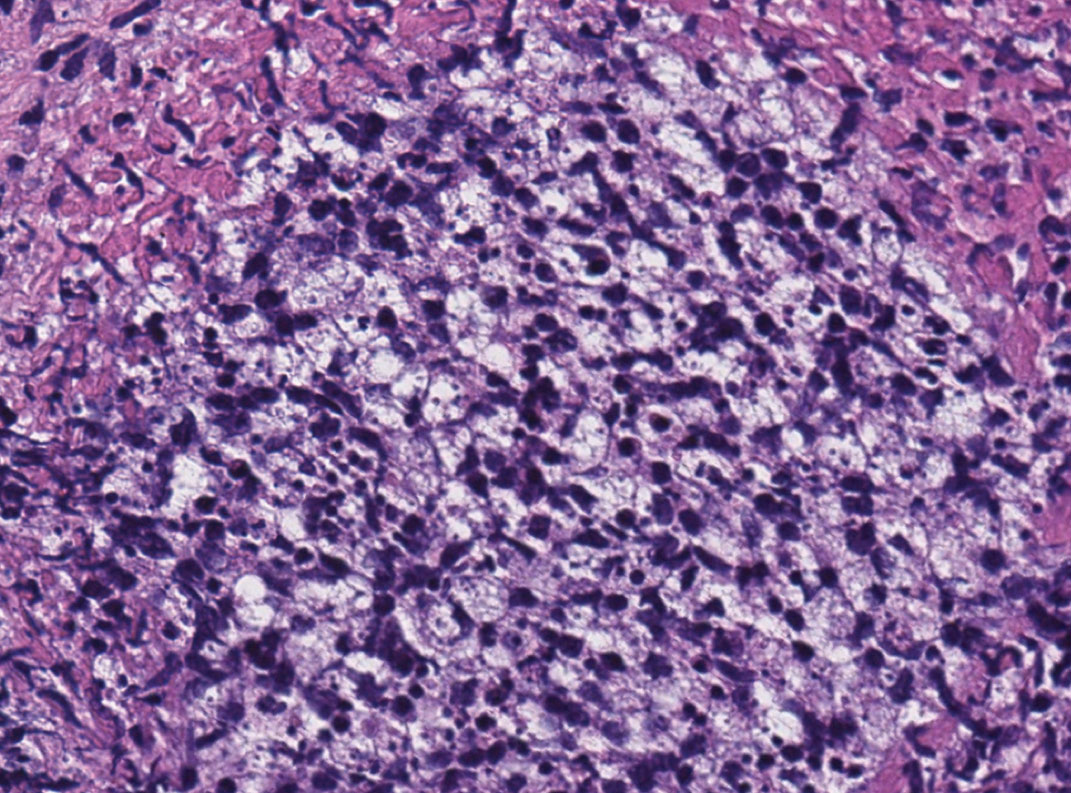

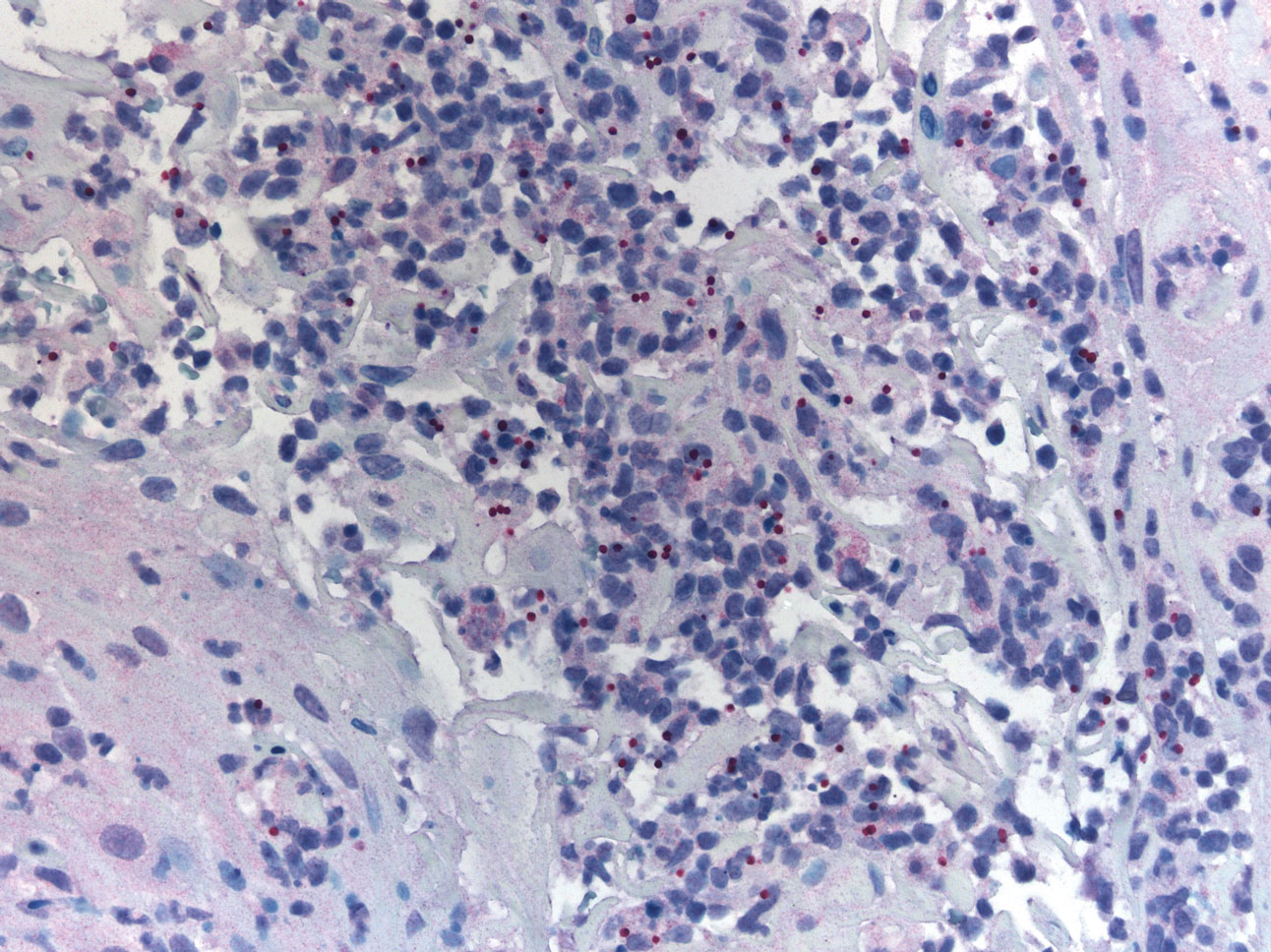

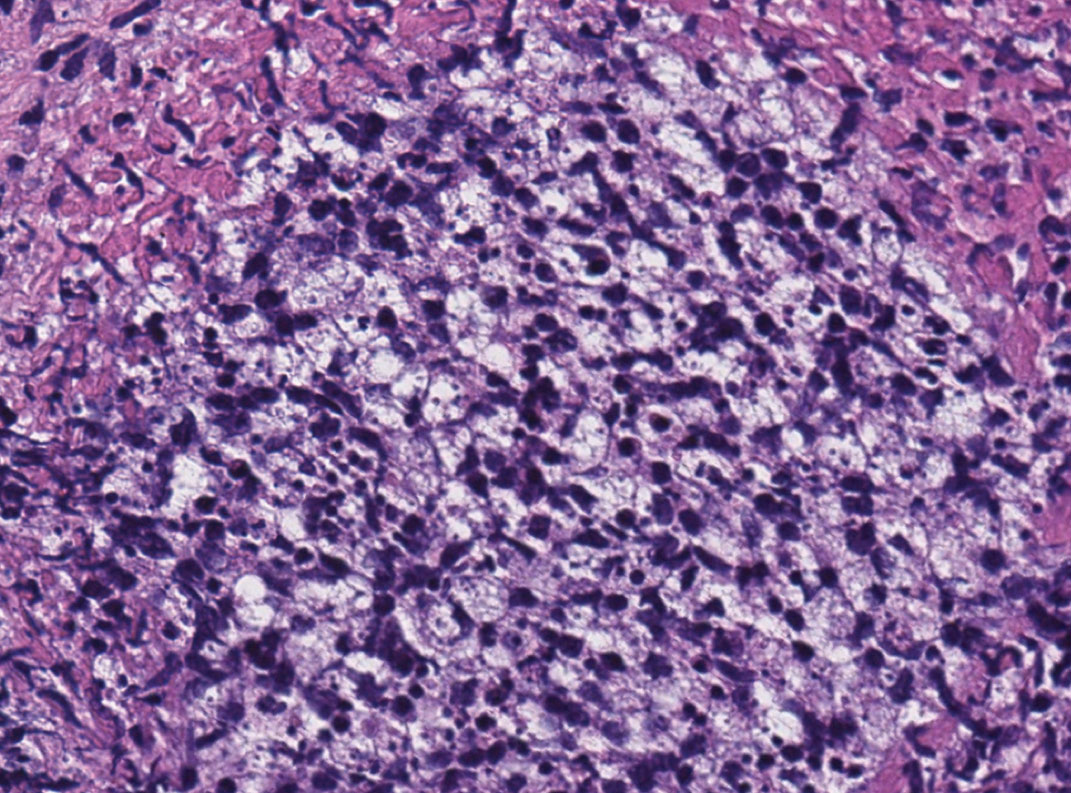

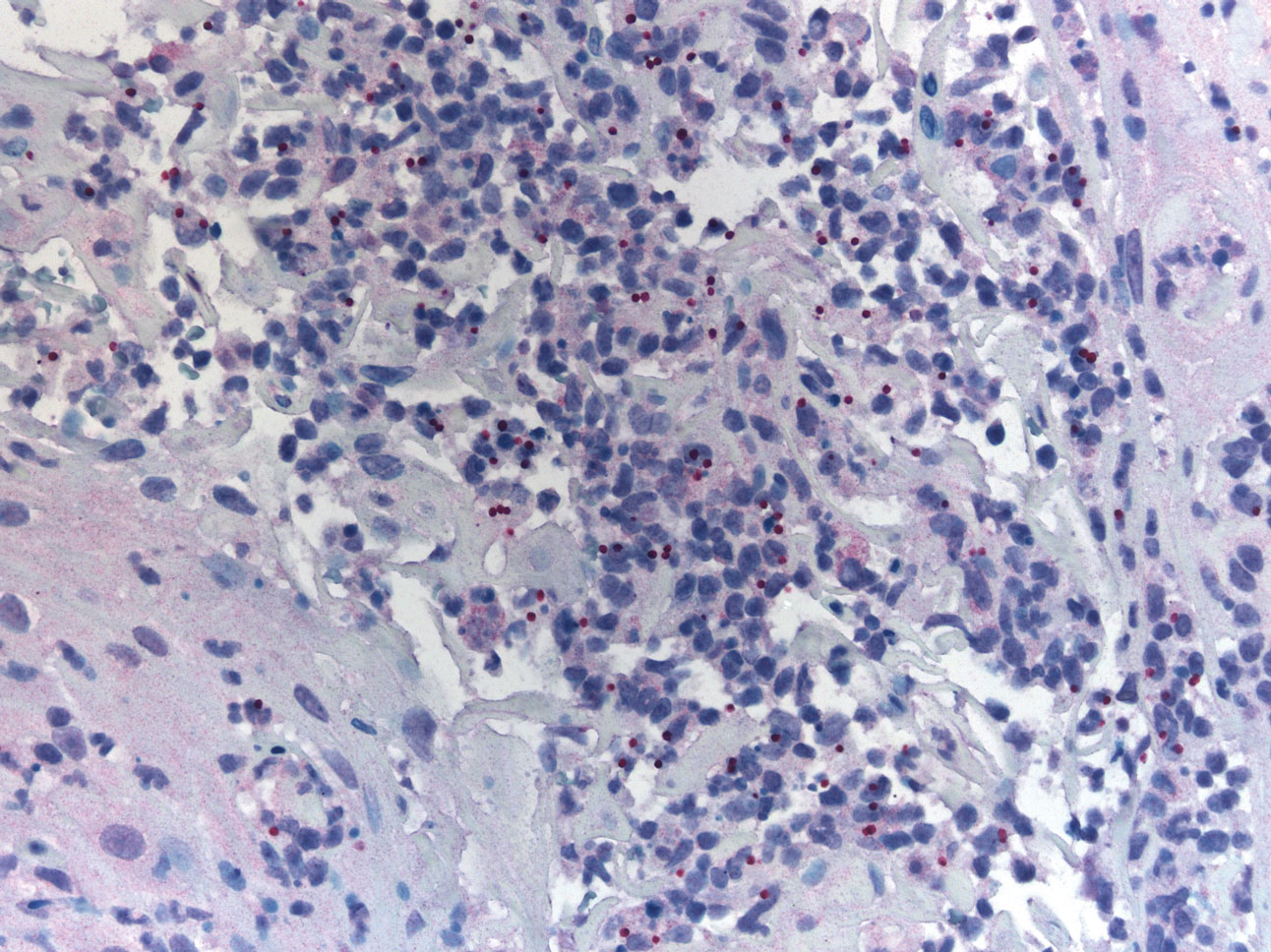

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6

Leishmania braziliensis and L panamensis, the species that infected our patients, can uniquely cause cutaneous leishmaniasis that metastasizes into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which always affects the nasal mucosa. Risk factors for transformation include a primary lesion site above the waist, multiple or large primary lesions, and delayed healing of primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can result in notable morbidity and even mortality from invasion and destruction of nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa, as well as intercurrent pneumonia, especially if treatment is insufficient or delayed.4

Diagnosis

Prompt treatment relies on accurate and timely diagnosis, which is complicated by the relative unfamiliarity with leishmaniasis in the United States. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis is broad, including deep fungal infection, Mycobacterium infection, cutaneous granulomatous conditions, nonmelanoma cutaneous neoplasms, and trauma. Taking a thorough patient history, including potential exposures and travels; having high clinical suspicion; and being aware of classic presentation allows for identification of leishmaniasis and subsequent stratification by manifestation.7

Diagnosis is made by detecting Leishmania organisms or DNA using light microscopy and staining to visualize the kinetoplast in an amastigote, molecular methods, or specialized culturing.7 The CDC is a valuable diagnostic partner for confirmation and speciation. Specific instructions for specimen collection and transportation can be found by contacting the CDC or reading their guide.8 To provide prompt care and reassurance to patients, it is important to be aware of the coordination effort that may be needed to send samples, receive results, and otherwise correspond with a separate institution.

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is indicated to decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination and clinical reactivation of lesions, accelerate healing of lesions, decrease local morbidity caused by large or persistent lesions, and decrease the reservoir of infection in places where infected humans serve as reservoir hosts. Oral treatments include ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, recommended at doses ranging from 200 to 600 mg daily for at least 28 days. For severe, refractory, or visceral leishmaniasis, parenteral choices include

Miltefosine is becoming a more common treatment of leishmaniasis because of its oral route, tolerability in nonpregnant patients, and commercial availability. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L panamensis, and Leishmania guyanensis; mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis; and visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani in patients at least 12 years of age. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, the standard dosage of 50 mg twice daily (for patients weighing 30–44 kg) or 3 times daily (for patients weighing 45 kg or more) for 28 consecutive days has cure rates of 48% to 85% by 6 months after therapy ends. Cure is defined as epithelialization of lesions, no enlargement greater than 50% in lesions, no appearance of new lesions, and/or negative parasitology. The antileishmanial mechanism of action is unknown and likely involves interaction with lipids, inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, and apoptosislike cell death. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnancy. The most common adverse reactions in patients include nausea (35.9%–41.7%), motion sickness (29.2%), headache (28.1%), and emesis (4.5%–27.5%). With the exception of headache, these adverse reactions can decrease with administration of food, fluids, and antiemetics. Potentially more serious but rarer adverse reactions include elevated serum creatinine (5%–25%) and transaminases (5%). Although our patients had mild hyperkalemia, it is not an established adverse reaction. However, renal injury has been reported.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence in the United States due to increased foreign travel. Providers should be familiar with the cutaneous presentation of leishmaniasis, even in areas of low prevalence, to limit the risk for mucocutaneous dissemination from infection with the subgenus Viannia. Prompt treatment is vital to ensuring the best prognosis, and first-line treatment with miltefosine should be strongly considered given its efficacy and tolerability.

- Babuadze G, Alvar J, Argaw D, et al. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Georgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2725.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/Leishmaniasis. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Update March 2, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for DEET insect repellent use. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/toolkit/DEET.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2020.

- Buescher MD, Rutledge LC, Wirtz RA, et al. The dose-persistence relationship of DEET against Aedes aegypti. Mosq News. 1983;43:364-366.

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202-e264.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Practical guide for specimen collection and reference diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/resources/pdf/cdc_diagnosis_guide_leishmaniasis_2016.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative website. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/leishmaniasis/. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Impavido Medication Guide. Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204684s000lbl.pdf. Revised March 2014. Accessed May 18, 2020.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6

Leishmania braziliensis and L panamensis, the species that infected our patients, can uniquely cause cutaneous leishmaniasis that metastasizes into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which always affects the nasal mucosa. Risk factors for transformation include a primary lesion site above the waist, multiple or large primary lesions, and delayed healing of primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can result in notable morbidity and even mortality from invasion and destruction of nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa, as well as intercurrent pneumonia, especially if treatment is insufficient or delayed.4

Diagnosis

Prompt treatment relies on accurate and timely diagnosis, which is complicated by the relative unfamiliarity with leishmaniasis in the United States. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis is broad, including deep fungal infection, Mycobacterium infection, cutaneous granulomatous conditions, nonmelanoma cutaneous neoplasms, and trauma. Taking a thorough patient history, including potential exposures and travels; having high clinical suspicion; and being aware of classic presentation allows for identification of leishmaniasis and subsequent stratification by manifestation.7

Diagnosis is made by detecting Leishmania organisms or DNA using light microscopy and staining to visualize the kinetoplast in an amastigote, molecular methods, or specialized culturing.7 The CDC is a valuable diagnostic partner for confirmation and speciation. Specific instructions for specimen collection and transportation can be found by contacting the CDC or reading their guide.8 To provide prompt care and reassurance to patients, it is important to be aware of the coordination effort that may be needed to send samples, receive results, and otherwise correspond with a separate institution.

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is indicated to decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination and clinical reactivation of lesions, accelerate healing of lesions, decrease local morbidity caused by large or persistent lesions, and decrease the reservoir of infection in places where infected humans serve as reservoir hosts. Oral treatments include ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, recommended at doses ranging from 200 to 600 mg daily for at least 28 days. For severe, refractory, or visceral leishmaniasis, parenteral choices include

Miltefosine is becoming a more common treatment of leishmaniasis because of its oral route, tolerability in nonpregnant patients, and commercial availability. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L panamensis, and Leishmania guyanensis; mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis; and visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani in patients at least 12 years of age. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, the standard dosage of 50 mg twice daily (for patients weighing 30–44 kg) or 3 times daily (for patients weighing 45 kg or more) for 28 consecutive days has cure rates of 48% to 85% by 6 months after therapy ends. Cure is defined as epithelialization of lesions, no enlargement greater than 50% in lesions, no appearance of new lesions, and/or negative parasitology. The antileishmanial mechanism of action is unknown and likely involves interaction with lipids, inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, and apoptosislike cell death. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnancy. The most common adverse reactions in patients include nausea (35.9%–41.7%), motion sickness (29.2%), headache (28.1%), and emesis (4.5%–27.5%). With the exception of headache, these adverse reactions can decrease with administration of food, fluids, and antiemetics. Potentially more serious but rarer adverse reactions include elevated serum creatinine (5%–25%) and transaminases (5%). Although our patients had mild hyperkalemia, it is not an established adverse reaction. However, renal injury has been reported.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence in the United States due to increased foreign travel. Providers should be familiar with the cutaneous presentation of leishmaniasis, even in areas of low prevalence, to limit the risk for mucocutaneous dissemination from infection with the subgenus Viannia. Prompt treatment is vital to ensuring the best prognosis, and first-line treatment with miltefosine should be strongly considered given its efficacy and tolerability.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6

Leishmania braziliensis and L panamensis, the species that infected our patients, can uniquely cause cutaneous leishmaniasis that metastasizes into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which always affects the nasal mucosa. Risk factors for transformation include a primary lesion site above the waist, multiple or large primary lesions, and delayed healing of primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can result in notable morbidity and even mortality from invasion and destruction of nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa, as well as intercurrent pneumonia, especially if treatment is insufficient or delayed.4

Diagnosis

Prompt treatment relies on accurate and timely diagnosis, which is complicated by the relative unfamiliarity with leishmaniasis in the United States. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis is broad, including deep fungal infection, Mycobacterium infection, cutaneous granulomatous conditions, nonmelanoma cutaneous neoplasms, and trauma. Taking a thorough patient history, including potential exposures and travels; having high clinical suspicion; and being aware of classic presentation allows for identification of leishmaniasis and subsequent stratification by manifestation.7

Diagnosis is made by detecting Leishmania organisms or DNA using light microscopy and staining to visualize the kinetoplast in an amastigote, molecular methods, or specialized culturing.7 The CDC is a valuable diagnostic partner for confirmation and speciation. Specific instructions for specimen collection and transportation can be found by contacting the CDC or reading their guide.8 To provide prompt care and reassurance to patients, it is important to be aware of the coordination effort that may be needed to send samples, receive results, and otherwise correspond with a separate institution.

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is indicated to decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination and clinical reactivation of lesions, accelerate healing of lesions, decrease local morbidity caused by large or persistent lesions, and decrease the reservoir of infection in places where infected humans serve as reservoir hosts. Oral treatments include ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, recommended at doses ranging from 200 to 600 mg daily for at least 28 days. For severe, refractory, or visceral leishmaniasis, parenteral choices include

Miltefosine is becoming a more common treatment of leishmaniasis because of its oral route, tolerability in nonpregnant patients, and commercial availability. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L panamensis, and Leishmania guyanensis; mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis; and visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani in patients at least 12 years of age. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, the standard dosage of 50 mg twice daily (for patients weighing 30–44 kg) or 3 times daily (for patients weighing 45 kg or more) for 28 consecutive days has cure rates of 48% to 85% by 6 months after therapy ends. Cure is defined as epithelialization of lesions, no enlargement greater than 50% in lesions, no appearance of new lesions, and/or negative parasitology. The antileishmanial mechanism of action is unknown and likely involves interaction with lipids, inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, and apoptosislike cell death. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnancy. The most common adverse reactions in patients include nausea (35.9%–41.7%), motion sickness (29.2%), headache (28.1%), and emesis (4.5%–27.5%). With the exception of headache, these adverse reactions can decrease with administration of food, fluids, and antiemetics. Potentially more serious but rarer adverse reactions include elevated serum creatinine (5%–25%) and transaminases (5%). Although our patients had mild hyperkalemia, it is not an established adverse reaction. However, renal injury has been reported.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence in the United States due to increased foreign travel. Providers should be familiar with the cutaneous presentation of leishmaniasis, even in areas of low prevalence, to limit the risk for mucocutaneous dissemination from infection with the subgenus Viannia. Prompt treatment is vital to ensuring the best prognosis, and first-line treatment with miltefosine should be strongly considered given its efficacy and tolerability.

- Babuadze G, Alvar J, Argaw D, et al. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Georgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2725.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/Leishmaniasis. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Update March 2, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for DEET insect repellent use. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/toolkit/DEET.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2020.

- Buescher MD, Rutledge LC, Wirtz RA, et al. The dose-persistence relationship of DEET against Aedes aegypti. Mosq News. 1983;43:364-366.

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202-e264.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Practical guide for specimen collection and reference diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/resources/pdf/cdc_diagnosis_guide_leishmaniasis_2016.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative website. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/leishmaniasis/. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Impavido Medication Guide. Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204684s000lbl.pdf. Revised March 2014. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Babuadze G, Alvar J, Argaw D, et al. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Georgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2725.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/Leishmaniasis. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Update March 2, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for DEET insect repellent use. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/toolkit/DEET.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2020.

- Buescher MD, Rutledge LC, Wirtz RA, et al. The dose-persistence relationship of DEET against Aedes aegypti. Mosq News. 1983;43:364-366.

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202-e264.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Practical guide for specimen collection and reference diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/resources/pdf/cdc_diagnosis_guide_leishmaniasis_2016.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative website. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/leishmaniasis/. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Impavido Medication Guide. Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204684s000lbl.pdf. Revised March 2014. Accessed May 18, 2020.

Practice Points

- Avoiding phlebotomine sand fly vector bites is the most effective way to prevent leishmaniasis.

- Prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania species that have potential for mucocutaneous spread are key to limiting morbidity and mortality.

- Partnering with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is critical for timely diagnosis.

- Miltefosine should be considered as a first-line agent for cutaneous leishmaniasis given its efficacy, tolerability, and ease of administration.

Agminated Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

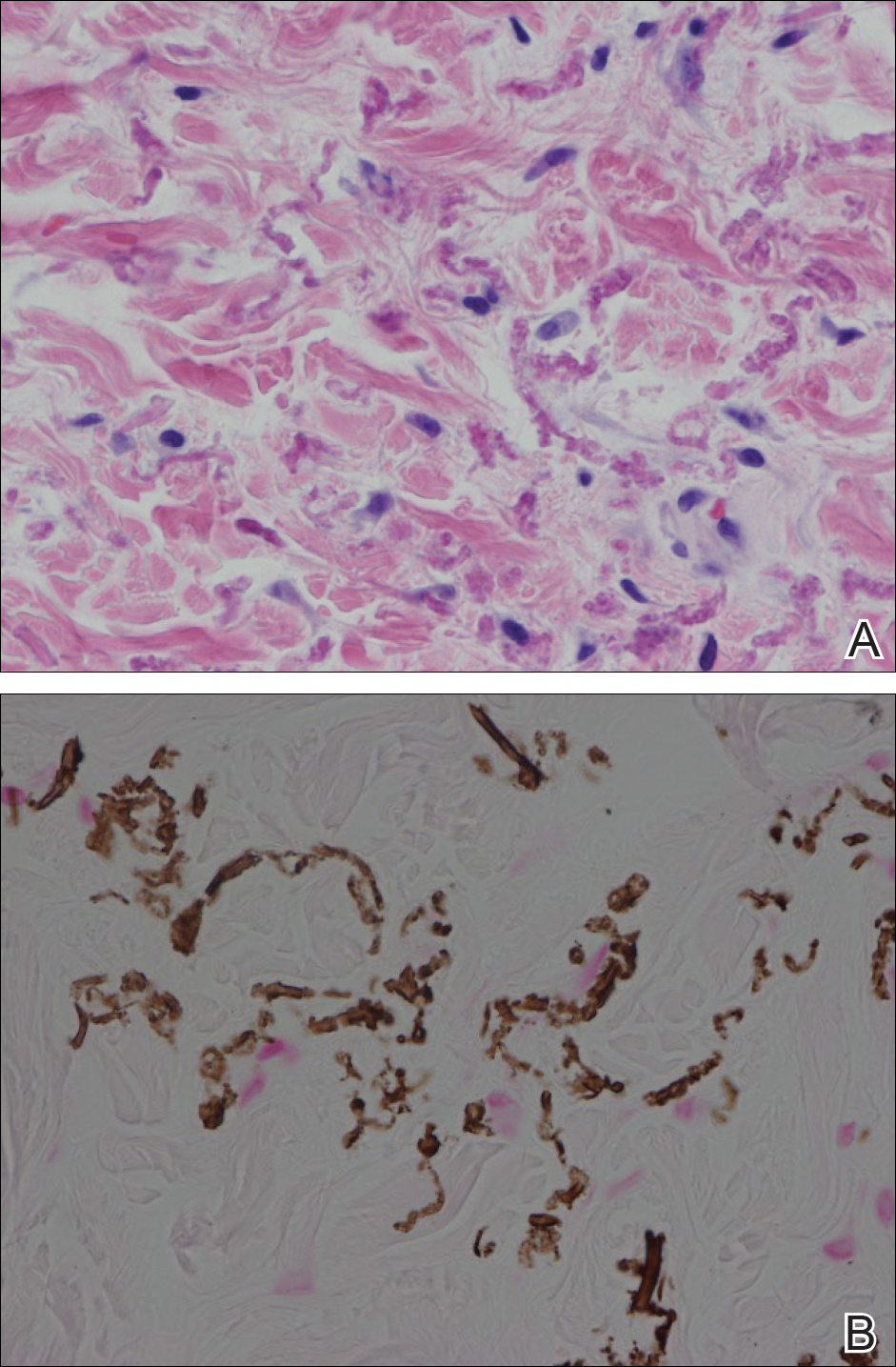

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

A 24-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the neck of 3 months' duration. She noted occasional mild pruritus at the site but no other symptoms or similar lesions elsewhere. At the time of presentation, she was at 17 weeks of gestation without any complications. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, unspecified chest pain with a normal electrocardiogram, and 2 spontaneous abortions. She denied a personal or family history of notable cardiovascular or gastrointestinal tract diseases. Examination of the skin showed indurated 3- to 5-mm papules coalescing into a 3- to 4-cm plaque on the left posterolateral neck.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Pantoprazole

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

Painful Violaceous Nodule With Peripheral Hyperpigmentation

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

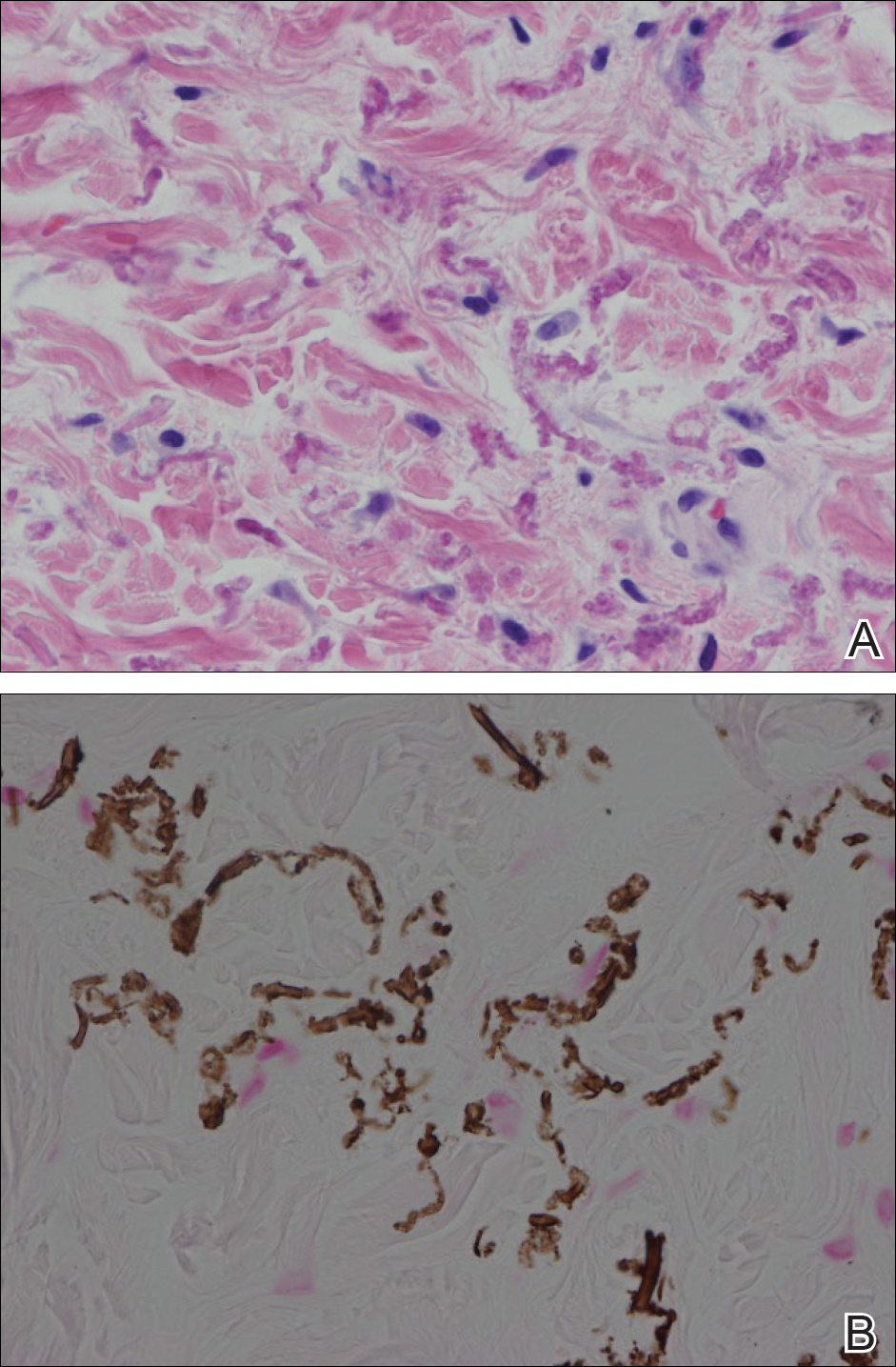

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.

- Alves JV, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Ferrari A, Argenziano G, Buccini P, et al. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1375-1380.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours--an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.

- Alves JV, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Ferrari A, Argenziano G, Buccini P, et al. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1375-1380.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours--an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.