User login

Transition From Lichen Sclerosus to Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Single Tissue Section

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

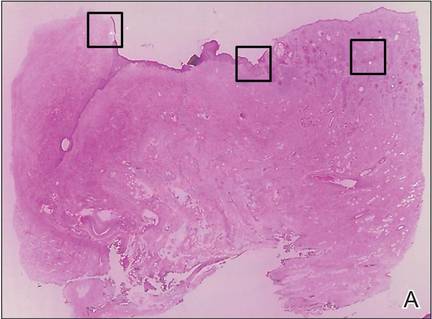

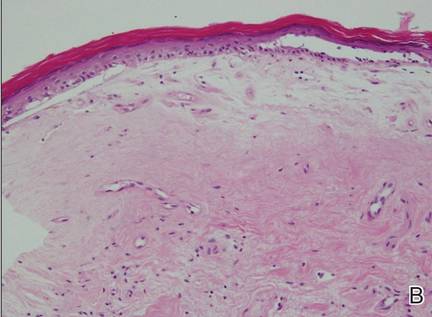

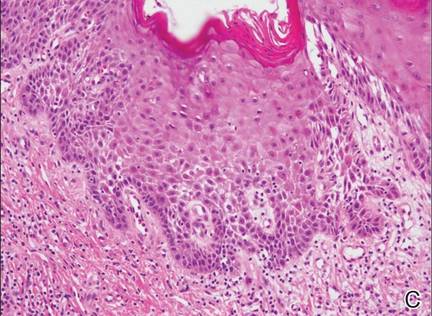

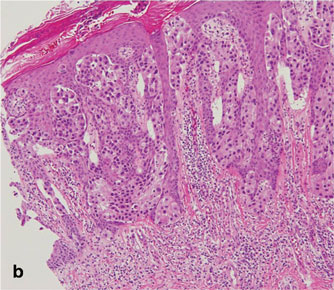

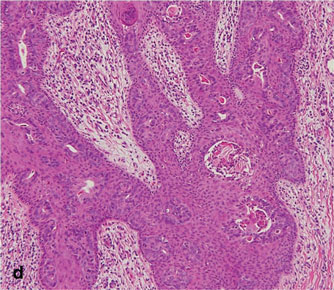

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

Practice Points

- Lichen sclerosus has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients.

- Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

Nodular Extramammary Paget Disease With Fibroepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

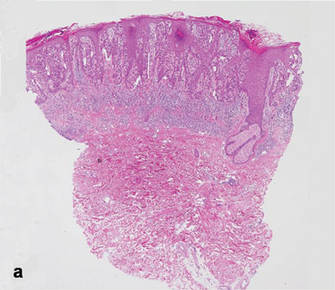

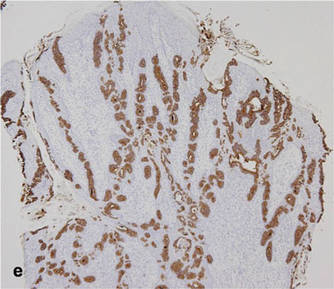

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the anogenital region but can arise in any area of the skin or mucosa.1 On clinical examination, EMPD typically presents as a sharply demarcated, erythematous, eczematoid, weeping lesion with varying degrees of induration; it rarely presents as a palpable mass or evenly raised nodule.2 Microscopically, it may be accompanied by varying degrees of epidermal hyperplasia.1 In particular, fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia contains lacy strands of squamous epithelium resembling fibroepithelioma of Pinkus.3 We report a case of EMPD in a 90-year-old man who presented with a verrucous nodule in the pubic area that histologically demonstrated fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

Case Report

A 90-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques in the pubic area of 5 years’ duration, along with a 3.0×2.5-cm nodule on the left side of the pubic area (Figure 1). Laboratory test results including a complete blood cell count, blood chemistry, and routine urinalysis were within reference range. Punch biopsies were taken from each plaque and nodule, as marked with arrows in Figure 1. Histopathologically, the plaques were seen to contain a number of large round cells with abundant pale cytoplasm and pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei that were present at various levels of the epidermis where they formed nests and clusters but did not extend into the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The nodule contained lacy strands of squamous epithelium extending from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures (Figures 2C and 2D). The cells in the epidermis stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 7 (Figure 2E). We also tested for S-100 protein to rule out malignant melanoma, which was negative.

Based on both the clinical and histological features, a diagnosis of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia was made. It was recommended that the patient undergo further evaluation and treatment; he declined due to his financial situation and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Clinically, EMPD usually presents as a patch of macular erythema, an erythematous eruption, or erythematous papules and plaques.4 The palpable nodule seen in our patient is not a common presentation of EMPD. Pruritus is the most common symptom of EMPD, occurring in 70% of patients.5 Other symptoms include burning, irritation, pain, tenderness, bleeding, and swelling. Ten percent of EMPD cases are asymptomatic.5

Histologically, Paget cells primarily involve the epidermis where they usually form clusters or solid nests. In more than 90% of EMPD cases, the Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin that stains positively with mucicarmine and PAS. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, S-100 protein, and CEA sometimes may be needed to differentiate from mimickers such as Bowen disease and superficial spreading melanoma.6 In our patient, the tumor cells stained positive for cytokeratin 7, CEA, and PAS. Malignant melanoma was ruled out with a test for S-100 protein.

|

|

Extramammary Paget disease often is associated with epidermal hyperplasia, which can be classified as squamous, papillomatous, or fibroepitheliomatous.3 Microscopically, squamous hyperplasia is characterized by prominent thickening of the epidermis from diffuse plaquelike hyperplasia and is usually associated with hyperkeratosis. Papillomatous hyperplasia has an exophytic papillary or verrucous architecture and is associated with parakeratosis. Fibroepitheliomatous, or fibroepitheliomalike, hyperplasia generally consists of a discrete, broad, elevated plaque or nodule produced by hyperplasia of keratinocytes that form lacy strands of squamous epithelium.3 The biphasic pattern of proliferating epidermis and entrapped dermis simulates a so-called fibroepithelioma. Paget cells can be seen within the lacy strands of epidermal columns and in the acanthotic surface component.2 The finding of fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia in anogenital skin should prompt a search for the diagnostic Paget cells to eliminate a fibroepithelioma of Pinkus variant of basal cell carcinoma, though the latter is uncommon and rarely occurs at this site.7

Of the 3 types of epidermal hyperplasia, our case demonstrated the fibroepitheliomatous type. There may be some relationship between EMPD and fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia because most reported cases of EMPD with fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia have occurred in the anogenital region. Also, epidermal hyperplasia is more frequent in anogenital Paget disease than in axillary Paget disease.8

Conclusion

Our case showed the unique finding of a verrucous nodular EMPD lesion in which peculiar histological features presented as extensions of the tumor cells forming lacy strands of squamous epithelium from the epidermis to the mid dermis as well as many glandular structures.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

1. Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

2. Billings SD, Roth LM. Pseudoinvasive, nodular extramam-mary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:471-474.

3. Brainard JA, Hart WR. Proliferative epidermal lesions associated with anogenital Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:543-552.

4. Neuhaus IM, Grekin RC. Mammary and extramammary Paget disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1094-1098.

5. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

6. Kim JC, Kim HC, Jeong CS, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease with aggressive behavior: a report of two cases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:223-226.

7. Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epitheliomas in usual and unusual sites. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:425-431.

8. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Fibroepithelioma-like changes occurring in perianal Paget’s disease with rectal mucinous carcinoma: case report and review of 49 cases of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:185-189.

- Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) should be considered in the clinical differential diagnosis of verrucous nodules in the pubic area.

- Histopathologically, EMPD in the anogenital area could show fibroepitheliomatous hyperplasia with lacy strands of squamous epithelium.

An Amelanotic Malignant Melanoma of the Lip: Unusual Shape and Atypical Location

Test your knowledge on diagnosing cancer with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.