User login

Fewer GI docs, more alcohol-associated liver disease deaths

People are more likely to die of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) when there are fewer gastroenterologists in their state, researchers say.

The finding raises questions about steps that policymakers could take to increase the number of gastroenterologists and spread them more evenly around the United States.

“We found that there’s a fivefold difference in density of gastroenterologists through different states,” said Brian P. Lee, MD, MAS, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Lee and colleagues published their findings in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

ALD is becoming more common, and it is killing more people. Research among veterans has linked visits to gastroenterologists to a lower risk for death from liver disease.

To see whether that correlation applies more broadly, Dr. Lee and colleagues compared multiple datasets. One from the U.S. Health Resources & Service Administration provided the number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 population. The other from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 adults for each state and the District of Columbia.

The researchers adjusted for many variables that could affect the relationship between the availability of gastroenterologists and deaths related to ALD, including the age distribution of the population in each state, the gender balance, race and ethnicity, binge drinking, household income, obesity, and the proportion of rural residents.

They found that for every additional gastroenterologist, there is almost one fewer ALD-related death each year per 100,000 population (9.0 [95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.7] fewer ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 population for each additional gastroenterologist per 100,000 population).

The strength of the association appeared to plateau when there were at least 7.5 gastroenterologists per 100,000 people.

From these findings, the researchers calculated that as many as 40% of deaths from ALD nationwide could be prevented by providing more gastroenterologists in the places where they are lacking.

The mean number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 people in the United States was 4.6, and the annual ALD-related death rate was 85.6 per 1,000,000 people.

The Atlantic states had the greatest concentration of gastroenterologists and the lowest ALD-related mortality, whereas the Mountain states had the lowest concentration of gastroenterologists and the highest ALD-related mortality.

The lowest mortality related to ALD was in New Jersey, Maryland, and Hawaii, with 52 per 1,000,000 people, and the highest was in Wyoming, with 289.

Study shines spotlight on general GI care

Access to liver transplants did not make a statistically significant difference in mortality from ALD.

“It makes you realize that transplant will only be accessible for really just a small fraction of the population who needs it,” Dr. Lee told this news organization.

General gastroenterologic care appears to make a bigger difference in saving patients’ lives. “Are they getting endoscopy for bleeding from varices?” Dr. Lee asked. “Are they getting appropriate antibiotics prescribed to prevent bacterial infection of ascites?”

The concentration of primary care physicians did not reduce mortality from ALD, and neither did the concentration of substance use, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors.

Previous research has shown that substance abuse therapy is effective. But many people do not want to undertake it, or they face barriers of transportation, language, or insurance, said Dr. Lee.

“I have many patients whose insurance will provide them access to medical visits to me but will not to substance-use rehab, for example,” he said.

To see whether the effect was more generally due to the concentration of medical specialists, the researchers examined the state-level density of ophthalmologists and dermatologists. They found no significant difference in ALD-related mortality.

The finding builds on reports by the American Gastroenterological Association and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that the number of gastroenterologists has not kept up with the U.S. population nor the burden of digestive diseases, and that predicts a critical shortage in the future.

Overcoming barriers to care for liver disease

The overall supply of gastroenterologists could be increased by reducing the educational requirements and increasing the funding for fellowships, said Dr. Lee.

“We have to have a better understanding as to the barriers to gastroenterology practice in certain areas, then interventions to address those barriers and also incentives to attract gastroenterologists to those areas,” Dr. Lee said.

The study underscores the importance of access to gastroenterological care, said George Cholankeril, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the study. That urgency has only grown as ALD has spiraled up with the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

“Anyone in clinical practice right now will be able to say that there’s been a clear rising tide of patients with alcohol-related liver disease,” he told this news organization. “There’s an urgent need to address this and provide the necessary resources.”

Prevention remains essential, Dr. Cholankeril said.

Gastroenterologists and primary care physicians can help stem the tide of ALD by screening their patients for the disease through a tool like AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), he said. They can then refer patients to substance abuse treatment centers or to psychologists and psychiatrists.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Cholankeril report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People are more likely to die of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) when there are fewer gastroenterologists in their state, researchers say.

The finding raises questions about steps that policymakers could take to increase the number of gastroenterologists and spread them more evenly around the United States.

“We found that there’s a fivefold difference in density of gastroenterologists through different states,” said Brian P. Lee, MD, MAS, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Lee and colleagues published their findings in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

ALD is becoming more common, and it is killing more people. Research among veterans has linked visits to gastroenterologists to a lower risk for death from liver disease.

To see whether that correlation applies more broadly, Dr. Lee and colleagues compared multiple datasets. One from the U.S. Health Resources & Service Administration provided the number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 population. The other from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 adults for each state and the District of Columbia.

The researchers adjusted for many variables that could affect the relationship between the availability of gastroenterologists and deaths related to ALD, including the age distribution of the population in each state, the gender balance, race and ethnicity, binge drinking, household income, obesity, and the proportion of rural residents.

They found that for every additional gastroenterologist, there is almost one fewer ALD-related death each year per 100,000 population (9.0 [95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.7] fewer ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 population for each additional gastroenterologist per 100,000 population).

The strength of the association appeared to plateau when there were at least 7.5 gastroenterologists per 100,000 people.

From these findings, the researchers calculated that as many as 40% of deaths from ALD nationwide could be prevented by providing more gastroenterologists in the places where they are lacking.

The mean number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 people in the United States was 4.6, and the annual ALD-related death rate was 85.6 per 1,000,000 people.

The Atlantic states had the greatest concentration of gastroenterologists and the lowest ALD-related mortality, whereas the Mountain states had the lowest concentration of gastroenterologists and the highest ALD-related mortality.

The lowest mortality related to ALD was in New Jersey, Maryland, and Hawaii, with 52 per 1,000,000 people, and the highest was in Wyoming, with 289.

Study shines spotlight on general GI care

Access to liver transplants did not make a statistically significant difference in mortality from ALD.

“It makes you realize that transplant will only be accessible for really just a small fraction of the population who needs it,” Dr. Lee told this news organization.

General gastroenterologic care appears to make a bigger difference in saving patients’ lives. “Are they getting endoscopy for bleeding from varices?” Dr. Lee asked. “Are they getting appropriate antibiotics prescribed to prevent bacterial infection of ascites?”

The concentration of primary care physicians did not reduce mortality from ALD, and neither did the concentration of substance use, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors.

Previous research has shown that substance abuse therapy is effective. But many people do not want to undertake it, or they face barriers of transportation, language, or insurance, said Dr. Lee.

“I have many patients whose insurance will provide them access to medical visits to me but will not to substance-use rehab, for example,” he said.

To see whether the effect was more generally due to the concentration of medical specialists, the researchers examined the state-level density of ophthalmologists and dermatologists. They found no significant difference in ALD-related mortality.

The finding builds on reports by the American Gastroenterological Association and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that the number of gastroenterologists has not kept up with the U.S. population nor the burden of digestive diseases, and that predicts a critical shortage in the future.

Overcoming barriers to care for liver disease

The overall supply of gastroenterologists could be increased by reducing the educational requirements and increasing the funding for fellowships, said Dr. Lee.

“We have to have a better understanding as to the barriers to gastroenterology practice in certain areas, then interventions to address those barriers and also incentives to attract gastroenterologists to those areas,” Dr. Lee said.

The study underscores the importance of access to gastroenterological care, said George Cholankeril, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the study. That urgency has only grown as ALD has spiraled up with the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

“Anyone in clinical practice right now will be able to say that there’s been a clear rising tide of patients with alcohol-related liver disease,” he told this news organization. “There’s an urgent need to address this and provide the necessary resources.”

Prevention remains essential, Dr. Cholankeril said.

Gastroenterologists and primary care physicians can help stem the tide of ALD by screening their patients for the disease through a tool like AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), he said. They can then refer patients to substance abuse treatment centers or to psychologists and psychiatrists.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Cholankeril report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People are more likely to die of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) when there are fewer gastroenterologists in their state, researchers say.

The finding raises questions about steps that policymakers could take to increase the number of gastroenterologists and spread them more evenly around the United States.

“We found that there’s a fivefold difference in density of gastroenterologists through different states,” said Brian P. Lee, MD, MAS, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Lee and colleagues published their findings in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

ALD is becoming more common, and it is killing more people. Research among veterans has linked visits to gastroenterologists to a lower risk for death from liver disease.

To see whether that correlation applies more broadly, Dr. Lee and colleagues compared multiple datasets. One from the U.S. Health Resources & Service Administration provided the number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 population. The other from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 adults for each state and the District of Columbia.

The researchers adjusted for many variables that could affect the relationship between the availability of gastroenterologists and deaths related to ALD, including the age distribution of the population in each state, the gender balance, race and ethnicity, binge drinking, household income, obesity, and the proportion of rural residents.

They found that for every additional gastroenterologist, there is almost one fewer ALD-related death each year per 100,000 population (9.0 [95% confidence interval, 1.3-16.7] fewer ALD-related deaths per 1,000,000 population for each additional gastroenterologist per 100,000 population).

The strength of the association appeared to plateau when there were at least 7.5 gastroenterologists per 100,000 people.

From these findings, the researchers calculated that as many as 40% of deaths from ALD nationwide could be prevented by providing more gastroenterologists in the places where they are lacking.

The mean number of gastroenterologists per 100,000 people in the United States was 4.6, and the annual ALD-related death rate was 85.6 per 1,000,000 people.

The Atlantic states had the greatest concentration of gastroenterologists and the lowest ALD-related mortality, whereas the Mountain states had the lowest concentration of gastroenterologists and the highest ALD-related mortality.

The lowest mortality related to ALD was in New Jersey, Maryland, and Hawaii, with 52 per 1,000,000 people, and the highest was in Wyoming, with 289.

Study shines spotlight on general GI care

Access to liver transplants did not make a statistically significant difference in mortality from ALD.

“It makes you realize that transplant will only be accessible for really just a small fraction of the population who needs it,” Dr. Lee told this news organization.

General gastroenterologic care appears to make a bigger difference in saving patients’ lives. “Are they getting endoscopy for bleeding from varices?” Dr. Lee asked. “Are they getting appropriate antibiotics prescribed to prevent bacterial infection of ascites?”

The concentration of primary care physicians did not reduce mortality from ALD, and neither did the concentration of substance use, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors.

Previous research has shown that substance abuse therapy is effective. But many people do not want to undertake it, or they face barriers of transportation, language, or insurance, said Dr. Lee.

“I have many patients whose insurance will provide them access to medical visits to me but will not to substance-use rehab, for example,” he said.

To see whether the effect was more generally due to the concentration of medical specialists, the researchers examined the state-level density of ophthalmologists and dermatologists. They found no significant difference in ALD-related mortality.

The finding builds on reports by the American Gastroenterological Association and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that the number of gastroenterologists has not kept up with the U.S. population nor the burden of digestive diseases, and that predicts a critical shortage in the future.

Overcoming barriers to care for liver disease

The overall supply of gastroenterologists could be increased by reducing the educational requirements and increasing the funding for fellowships, said Dr. Lee.

“We have to have a better understanding as to the barriers to gastroenterology practice in certain areas, then interventions to address those barriers and also incentives to attract gastroenterologists to those areas,” Dr. Lee said.

The study underscores the importance of access to gastroenterological care, said George Cholankeril, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the study. That urgency has only grown as ALD has spiraled up with the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

“Anyone in clinical practice right now will be able to say that there’s been a clear rising tide of patients with alcohol-related liver disease,” he told this news organization. “There’s an urgent need to address this and provide the necessary resources.”

Prevention remains essential, Dr. Cholankeril said.

Gastroenterologists and primary care physicians can help stem the tide of ALD by screening their patients for the disease through a tool like AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), he said. They can then refer patients to substance abuse treatment centers or to psychologists and psychiatrists.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Cholankeril report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Gene variants found to protect against liver disease

Rare gene variants are associated with a reduced risk for multiple types of liver disease, including cirrhosis, researchers say.

People with certain variants in the gene CIDEB are one-third less likely to develop any sort of liver disease, according to Aris Baras, MD, a senior vice president at Regeneron, and colleagues.

“The unprecedented protective effect that these CIDEB genetic variants have against liver disease provides us with one of our most exciting targets and potential therapeutic approaches for a notoriously hard-to-treat disease where there are currently no approved treatments,” said Dr. Baras in a press release.

Dr. Baras and colleagues published the finding in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The finding follows on a similar discovery about a common variant in the gene HSD17B13. Treatments targeting this gene are being tested in clinical trials.

To search for more such genes, the researchers analyzed human exomes – the part of the genome that codes for proteins – to look for associations between gene variants and liver function.

The researchers used exome sequencing on 542,904 people from the UK Biobank, the Geisinger Health System MyCode cohort, and other datasets.

They found that coding variants in APOB, ABCB4, SLC30A10, and TM6SF2 were associated with increased aminotransferase levels and an increased risk for liver disease.

But variants in CIDEB were associated with decreased levels of alanine aminotransferase, a biomarker of hepatocellular injury. And they were associated with a decreased risk for liver disease of any cause (odds ratio per allele, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.79).

The CIDEB variants were present in only 0.7% of the persons in the study.

Zeroing in on various kinds of liver disease, the researchers found that the CIDEB variants were associated with a reduced risk for alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic liver disease, any liver cirrhosis, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, nonalcoholic liver cirrhosis, and viral hepatitis.

In 3,599 patients who had undergone bariatric surgery, variants in CIDEB were associated with a reduced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of –0.98 beta per allele in score units, where scores range from 0-8, with a higher score indicating more severe disease.

In patients for whom MRI data were available, those with rare coding variants in CIDEB had lower proportions of liver fat. However, percentage of liver fat did not fully explain the reduced risk for liver disease.

Pursuing another line of investigation, the researchers found that they could prevent the buildup of large lipid droplets in oleic acid-treated human hepatoma cell lines by silencing the CIDEB gene using small interfering RNA.

The association was particularly strong among people with higher body mass indices and type 2 diabetes.

The associations with the rare protective CIDEB variants were consistent across ancestries, but people of non-European ancestry, who might be disproportionately affected by liver disease, were underrepresented in the database, the researchers note.

The study was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which also employed several of the researchers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rare gene variants are associated with a reduced risk for multiple types of liver disease, including cirrhosis, researchers say.

People with certain variants in the gene CIDEB are one-third less likely to develop any sort of liver disease, according to Aris Baras, MD, a senior vice president at Regeneron, and colleagues.

“The unprecedented protective effect that these CIDEB genetic variants have against liver disease provides us with one of our most exciting targets and potential therapeutic approaches for a notoriously hard-to-treat disease where there are currently no approved treatments,” said Dr. Baras in a press release.

Dr. Baras and colleagues published the finding in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The finding follows on a similar discovery about a common variant in the gene HSD17B13. Treatments targeting this gene are being tested in clinical trials.

To search for more such genes, the researchers analyzed human exomes – the part of the genome that codes for proteins – to look for associations between gene variants and liver function.

The researchers used exome sequencing on 542,904 people from the UK Biobank, the Geisinger Health System MyCode cohort, and other datasets.

They found that coding variants in APOB, ABCB4, SLC30A10, and TM6SF2 were associated with increased aminotransferase levels and an increased risk for liver disease.

But variants in CIDEB were associated with decreased levels of alanine aminotransferase, a biomarker of hepatocellular injury. And they were associated with a decreased risk for liver disease of any cause (odds ratio per allele, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.79).

The CIDEB variants were present in only 0.7% of the persons in the study.

Zeroing in on various kinds of liver disease, the researchers found that the CIDEB variants were associated with a reduced risk for alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic liver disease, any liver cirrhosis, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, nonalcoholic liver cirrhosis, and viral hepatitis.

In 3,599 patients who had undergone bariatric surgery, variants in CIDEB were associated with a reduced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of –0.98 beta per allele in score units, where scores range from 0-8, with a higher score indicating more severe disease.

In patients for whom MRI data were available, those with rare coding variants in CIDEB had lower proportions of liver fat. However, percentage of liver fat did not fully explain the reduced risk for liver disease.

Pursuing another line of investigation, the researchers found that they could prevent the buildup of large lipid droplets in oleic acid-treated human hepatoma cell lines by silencing the CIDEB gene using small interfering RNA.

The association was particularly strong among people with higher body mass indices and type 2 diabetes.

The associations with the rare protective CIDEB variants were consistent across ancestries, but people of non-European ancestry, who might be disproportionately affected by liver disease, were underrepresented in the database, the researchers note.

The study was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which also employed several of the researchers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rare gene variants are associated with a reduced risk for multiple types of liver disease, including cirrhosis, researchers say.

People with certain variants in the gene CIDEB are one-third less likely to develop any sort of liver disease, according to Aris Baras, MD, a senior vice president at Regeneron, and colleagues.

“The unprecedented protective effect that these CIDEB genetic variants have against liver disease provides us with one of our most exciting targets and potential therapeutic approaches for a notoriously hard-to-treat disease where there are currently no approved treatments,” said Dr. Baras in a press release.

Dr. Baras and colleagues published the finding in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The finding follows on a similar discovery about a common variant in the gene HSD17B13. Treatments targeting this gene are being tested in clinical trials.

To search for more such genes, the researchers analyzed human exomes – the part of the genome that codes for proteins – to look for associations between gene variants and liver function.

The researchers used exome sequencing on 542,904 people from the UK Biobank, the Geisinger Health System MyCode cohort, and other datasets.

They found that coding variants in APOB, ABCB4, SLC30A10, and TM6SF2 were associated with increased aminotransferase levels and an increased risk for liver disease.

But variants in CIDEB were associated with decreased levels of alanine aminotransferase, a biomarker of hepatocellular injury. And they were associated with a decreased risk for liver disease of any cause (odds ratio per allele, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.79).

The CIDEB variants were present in only 0.7% of the persons in the study.

Zeroing in on various kinds of liver disease, the researchers found that the CIDEB variants were associated with a reduced risk for alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic liver disease, any liver cirrhosis, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, nonalcoholic liver cirrhosis, and viral hepatitis.

In 3,599 patients who had undergone bariatric surgery, variants in CIDEB were associated with a reduced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of –0.98 beta per allele in score units, where scores range from 0-8, with a higher score indicating more severe disease.

In patients for whom MRI data were available, those with rare coding variants in CIDEB had lower proportions of liver fat. However, percentage of liver fat did not fully explain the reduced risk for liver disease.

Pursuing another line of investigation, the researchers found that they could prevent the buildup of large lipid droplets in oleic acid-treated human hepatoma cell lines by silencing the CIDEB gene using small interfering RNA.

The association was particularly strong among people with higher body mass indices and type 2 diabetes.

The associations with the rare protective CIDEB variants were consistent across ancestries, but people of non-European ancestry, who might be disproportionately affected by liver disease, were underrepresented in the database, the researchers note.

The study was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which also employed several of the researchers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

COVID-19 may trigger irritable bowel syndrome

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Low urate limits for gout questioned in study

Lower limits on serum urate levels applied in gout management may be based on a misreading of data on mortality risks, researchers say.

Low urate levels may not in themselves pose a risk of death but may be a sign of some other illness, said Joshua F. Baker, MD, MSCE, associate professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“It points us towards being more reassured that we can be aggressive in treating gout without a concern about long-term effects for our patients,” he said in an interview. He and colleagues published their findings online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Previous research has linked high levels of urate with excessive fat and low levels of urate with loss of skeletal muscle mass. And epidemiologic studies have shown a U-shaped relationship between urate levels and mortality, suggesting that very high and very low levels of urate could be harmful.

Based on this correlation, and the theory that urate could have antioxidant benefits, some professional societies have recommended not lowering urate levels below a defined threshold when treating gout. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology has recommended a lower limit of 3 mg/dL.

But the evidence doesn’t entirely support this caution. For example, in a clinical trial of pegloticase (Krystexxa) in patients with refractory gout, patients whose mean serum urate dropped below 2 mg/dL did not die in higher proportions than patients with higher urate levels.

To better understand the risk of low urate, Dr. Baker and colleagues analyzed data on 13,979 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) during 1999-2006. The dataset included whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition measures as well as urate levels.

The researchers argue this measurement reveals more about a person’s overall health than body mass index (BMI), which doesn’t distinguish between mass from fat and mass from muscle.

They defined low lean body mass, or sarcopenia, as an appendicular lean mass index relative to fat mass index z score of –1. And they defined low urate as less than 2.5 mg/dL in women and less than 3.5 mg/dL in men.

They found that 29% of people with low urate had low lean body mass, compared with 16% of people with normal urate levels. The difference was statistically significant (P = .001).

They found an association between low urate and increased mortality (hazard ratio, 1.61; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.28; P = .008). But that association lost its statistical significance when the researchers adjusted for body composition and weight loss (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.92-1.85; P = .13).

Dr. Baker thinks the association between elevated mortality and low urate can be explained by conditions such as cancer or lung inflammation that might on one hand increase the risk of death and on the other hand lower urate levels by lowering muscle mass. “Low uric acid levels are observed in people who have lost weight for unhealthy reasons, and that can explain relationships with long-term outcomes,” he said.

Proportions of muscle and fat could not account for the risk of mortality associated with high levels of urate, the researchers found. Those participants with urate levels above 5.7 mg/dL had a higher risk of death with higher levels of urate, and this persisted even after statistical adjustment for body composition.

The study sheds light on an important area of controversy, said Mehdi Fini, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the research.

But body composition does not entirely explain the relationship between urate and mortality, he told this news organization. Medications used to lower urate can cause side effects that might increase mortality, he said.

Also, he said, it’s important to understand the role of comorbidities. He cited evidence that low urate is associated with renal, cardiovascular, and pulmonary conditions. Safe levels of urate might differ depending on these factors. So rather than applying the same target serum level to all patients, perhaps researchers should investigate whether lowering urate by a percentage of the patient’s current level is safer and more effective, he suggested.

He agreed with an editorial that also appeared in Arthritis & Rheumatology saying that there is no evidence for a benefit in lowering urate much below 5 mg/dL. “No matter what, I think we should just be careful,” Dr. Fini said.

Dr. Fini and Dr. Baker report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Baker acknowledged support from a VA Clinical Science Research & Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation R&D Merit Award.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lower limits on serum urate levels applied in gout management may be based on a misreading of data on mortality risks, researchers say.

Low urate levels may not in themselves pose a risk of death but may be a sign of some other illness, said Joshua F. Baker, MD, MSCE, associate professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“It points us towards being more reassured that we can be aggressive in treating gout without a concern about long-term effects for our patients,” he said in an interview. He and colleagues published their findings online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Previous research has linked high levels of urate with excessive fat and low levels of urate with loss of skeletal muscle mass. And epidemiologic studies have shown a U-shaped relationship between urate levels and mortality, suggesting that very high and very low levels of urate could be harmful.

Based on this correlation, and the theory that urate could have antioxidant benefits, some professional societies have recommended not lowering urate levels below a defined threshold when treating gout. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology has recommended a lower limit of 3 mg/dL.

But the evidence doesn’t entirely support this caution. For example, in a clinical trial of pegloticase (Krystexxa) in patients with refractory gout, patients whose mean serum urate dropped below 2 mg/dL did not die in higher proportions than patients with higher urate levels.

To better understand the risk of low urate, Dr. Baker and colleagues analyzed data on 13,979 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) during 1999-2006. The dataset included whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition measures as well as urate levels.

The researchers argue this measurement reveals more about a person’s overall health than body mass index (BMI), which doesn’t distinguish between mass from fat and mass from muscle.

They defined low lean body mass, or sarcopenia, as an appendicular lean mass index relative to fat mass index z score of –1. And they defined low urate as less than 2.5 mg/dL in women and less than 3.5 mg/dL in men.

They found that 29% of people with low urate had low lean body mass, compared with 16% of people with normal urate levels. The difference was statistically significant (P = .001).

They found an association between low urate and increased mortality (hazard ratio, 1.61; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.28; P = .008). But that association lost its statistical significance when the researchers adjusted for body composition and weight loss (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.92-1.85; P = .13).

Dr. Baker thinks the association between elevated mortality and low urate can be explained by conditions such as cancer or lung inflammation that might on one hand increase the risk of death and on the other hand lower urate levels by lowering muscle mass. “Low uric acid levels are observed in people who have lost weight for unhealthy reasons, and that can explain relationships with long-term outcomes,” he said.

Proportions of muscle and fat could not account for the risk of mortality associated with high levels of urate, the researchers found. Those participants with urate levels above 5.7 mg/dL had a higher risk of death with higher levels of urate, and this persisted even after statistical adjustment for body composition.

The study sheds light on an important area of controversy, said Mehdi Fini, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the research.

But body composition does not entirely explain the relationship between urate and mortality, he told this news organization. Medications used to lower urate can cause side effects that might increase mortality, he said.

Also, he said, it’s important to understand the role of comorbidities. He cited evidence that low urate is associated with renal, cardiovascular, and pulmonary conditions. Safe levels of urate might differ depending on these factors. So rather than applying the same target serum level to all patients, perhaps researchers should investigate whether lowering urate by a percentage of the patient’s current level is safer and more effective, he suggested.

He agreed with an editorial that also appeared in Arthritis & Rheumatology saying that there is no evidence for a benefit in lowering urate much below 5 mg/dL. “No matter what, I think we should just be careful,” Dr. Fini said.

Dr. Fini and Dr. Baker report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Baker acknowledged support from a VA Clinical Science Research & Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation R&D Merit Award.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lower limits on serum urate levels applied in gout management may be based on a misreading of data on mortality risks, researchers say.

Low urate levels may not in themselves pose a risk of death but may be a sign of some other illness, said Joshua F. Baker, MD, MSCE, associate professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“It points us towards being more reassured that we can be aggressive in treating gout without a concern about long-term effects for our patients,” he said in an interview. He and colleagues published their findings online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Previous research has linked high levels of urate with excessive fat and low levels of urate with loss of skeletal muscle mass. And epidemiologic studies have shown a U-shaped relationship between urate levels and mortality, suggesting that very high and very low levels of urate could be harmful.

Based on this correlation, and the theory that urate could have antioxidant benefits, some professional societies have recommended not lowering urate levels below a defined threshold when treating gout. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology has recommended a lower limit of 3 mg/dL.

But the evidence doesn’t entirely support this caution. For example, in a clinical trial of pegloticase (Krystexxa) in patients with refractory gout, patients whose mean serum urate dropped below 2 mg/dL did not die in higher proportions than patients with higher urate levels.

To better understand the risk of low urate, Dr. Baker and colleagues analyzed data on 13,979 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) during 1999-2006. The dataset included whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition measures as well as urate levels.

The researchers argue this measurement reveals more about a person’s overall health than body mass index (BMI), which doesn’t distinguish between mass from fat and mass from muscle.

They defined low lean body mass, or sarcopenia, as an appendicular lean mass index relative to fat mass index z score of –1. And they defined low urate as less than 2.5 mg/dL in women and less than 3.5 mg/dL in men.

They found that 29% of people with low urate had low lean body mass, compared with 16% of people with normal urate levels. The difference was statistically significant (P = .001).

They found an association between low urate and increased mortality (hazard ratio, 1.61; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.28; P = .008). But that association lost its statistical significance when the researchers adjusted for body composition and weight loss (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.92-1.85; P = .13).

Dr. Baker thinks the association between elevated mortality and low urate can be explained by conditions such as cancer or lung inflammation that might on one hand increase the risk of death and on the other hand lower urate levels by lowering muscle mass. “Low uric acid levels are observed in people who have lost weight for unhealthy reasons, and that can explain relationships with long-term outcomes,” he said.

Proportions of muscle and fat could not account for the risk of mortality associated with high levels of urate, the researchers found. Those participants with urate levels above 5.7 mg/dL had a higher risk of death with higher levels of urate, and this persisted even after statistical adjustment for body composition.

The study sheds light on an important area of controversy, said Mehdi Fini, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the research.

But body composition does not entirely explain the relationship between urate and mortality, he told this news organization. Medications used to lower urate can cause side effects that might increase mortality, he said.

Also, he said, it’s important to understand the role of comorbidities. He cited evidence that low urate is associated with renal, cardiovascular, and pulmonary conditions. Safe levels of urate might differ depending on these factors. So rather than applying the same target serum level to all patients, perhaps researchers should investigate whether lowering urate by a percentage of the patient’s current level is safer and more effective, he suggested.

He agreed with an editorial that also appeared in Arthritis & Rheumatology saying that there is no evidence for a benefit in lowering urate much below 5 mg/dL. “No matter what, I think we should just be careful,” Dr. Fini said.

Dr. Fini and Dr. Baker report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Baker acknowledged support from a VA Clinical Science Research & Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation R&D Merit Award.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Artificial intelligence colonoscopy system shows promise

A new artificial intelligence (AI) system can help expert endoscopists improve their colonoscopies, a new study indicates.

Endoscopists using the computer program SKOUT (Iterative Scopes) achieved a 27% better detection rate of adenomas per colonoscopy, compared with endoscopists working without computer assistance, said lead author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at New York University.

The study showed that AI colonoscopy systems can work in a routine population of U.S. patients, Dr. Shaukat said in an interview.

“As gastroenterologists, we are very excited,” she said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology and was presented at the annual Digestive Disease® Week.

Previous research has shown that experienced endoscopists miss many polyps. To improve their detection rate, multiple companies have used machine learning to develop algorithms to identify suspicious areas.

“Once the computer sees the polyp, it puts a bounding box around it,” said Dr. Shaukat. “It draws the attention of the endoscopist to it. It assists the endoscopist but doesn’t replace the endoscopist.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two such systems: EndoScreener (Wision AI) and GI Genius (Cosmo Pharmaceuticals).

The SKOUT algorithm was trained on 3,616 full-length colonoscopy procedure videos from multiple centers. In bench testing, it achieved a 93.5% polyp-level true positive rate and a 2.3% false positive rate.

Randomized trial pits AI against standard procedure

To see how well the system works in the clinic, Dr. Shaukat and colleagues recruited 22 U.S. board-certified gastroenterologists from five academic and community centers. The gastroenterologists all had a minimum adenoma detection rate of 25%, defined as the number of colonoscopies in which at least one adenoma is found, divided by the number of colonoscopies performed. All the gastroenterologists had performed a minimum of 1,000 colonoscopy procedures.

The researchers randomly assigned 682 patients to undergo colonoscopy with the SKOUT and 677 to undergo colonoscopy using the standard procedure. The patients were aged 40 years or older and were scheduled for either screening or surveillance.

The endoscopists who received computer assistance detected 1.05 adenomas per colonoscopy versus 0.83 for those who did not have computer assistance, a statistically significant difference.

The proportion of resections with clinically significant histology was 71.7% with standard colonoscopies versus 67.4% with computer-assisted colonoscopies. This fell within the 14% margin that the researchers had set to show noninferiority for the computer system.

“The important thing is not just detecting all polyps but the polyps we care about, which are adenomas, and doing so without increasing the false positive rate,” said Dr. Shaukat.

The adenoma detection rate was 43.9% for the standard procedure and 47.8% for the computer-assisted procedure. This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr. Shaukat argued that the adenoma detection rate is not the best measure of success, because endoscopists sometimes stop looking for polyps once they find one.

The overall sessile serrated lesion detection rate for the standard colonoscopies was 16.0% versus 12.6% for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which also was not statistically significant.

Next steps

This study is important because it was a large, multicenter trial in the United States, said Omer Ahmad, BSc, MBBS, MRCP, a gastroenterologist and clinical researcher at University College London, who was not involved in the study. Most of the trials of AI have been in China or Europe. “It was very important just to see this replicated in the U.S. population.”

The average procedure time was 15.41 minutes for the standard colonoscopies versus 15.82 minutes for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which was not statistically different.

“It is important to note that the studies so far suggest that false positives do not have a significant impact on workflow,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The next crucial step in evaluating AI colonoscopy will be to track the effects over the long term, said Dr. Shaukat.

“As these technologies get approved and we see them in practice, we need to see that it’s leading to some outcome, like reduced colon cancer,” she said.

That also may be necessary before payers in the United States are willing to pay the additional cost for this technology, she added.

In the meantime, Dr. Ahmad said computer assistance is improving his own colonoscopies.

“I have found the systems have spotted some polyps that I may have otherwise missed,” he said. “There is a false positive rate, but for me, it doesn’t distract from my workflow.”

He believes the systems will be particularly helpful in improving the performance of less-skilled endoscopists.

He is also looking forward to systems that can help complete the reports needed at the end of each colonoscopy. “Most of us dislike having to write a laborious report and having to code everything at the end of the procedure,” he said.

The study was funded by Iterative Scopes. Dr. Shaukat reported having received research funding to her institution for the current study from Iterative Scopes and consulting fees from Freenome and Medtronic. Dr. Ahmad reports receiving speaker fees from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology/Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new artificial intelligence (AI) system can help expert endoscopists improve their colonoscopies, a new study indicates.

Endoscopists using the computer program SKOUT (Iterative Scopes) achieved a 27% better detection rate of adenomas per colonoscopy, compared with endoscopists working without computer assistance, said lead author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at New York University.

The study showed that AI colonoscopy systems can work in a routine population of U.S. patients, Dr. Shaukat said in an interview.

“As gastroenterologists, we are very excited,” she said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology and was presented at the annual Digestive Disease® Week.

Previous research has shown that experienced endoscopists miss many polyps. To improve their detection rate, multiple companies have used machine learning to develop algorithms to identify suspicious areas.

“Once the computer sees the polyp, it puts a bounding box around it,” said Dr. Shaukat. “It draws the attention of the endoscopist to it. It assists the endoscopist but doesn’t replace the endoscopist.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two such systems: EndoScreener (Wision AI) and GI Genius (Cosmo Pharmaceuticals).

The SKOUT algorithm was trained on 3,616 full-length colonoscopy procedure videos from multiple centers. In bench testing, it achieved a 93.5% polyp-level true positive rate and a 2.3% false positive rate.

Randomized trial pits AI against standard procedure

To see how well the system works in the clinic, Dr. Shaukat and colleagues recruited 22 U.S. board-certified gastroenterologists from five academic and community centers. The gastroenterologists all had a minimum adenoma detection rate of 25%, defined as the number of colonoscopies in which at least one adenoma is found, divided by the number of colonoscopies performed. All the gastroenterologists had performed a minimum of 1,000 colonoscopy procedures.

The researchers randomly assigned 682 patients to undergo colonoscopy with the SKOUT and 677 to undergo colonoscopy using the standard procedure. The patients were aged 40 years or older and were scheduled for either screening or surveillance.

The endoscopists who received computer assistance detected 1.05 adenomas per colonoscopy versus 0.83 for those who did not have computer assistance, a statistically significant difference.

The proportion of resections with clinically significant histology was 71.7% with standard colonoscopies versus 67.4% with computer-assisted colonoscopies. This fell within the 14% margin that the researchers had set to show noninferiority for the computer system.

“The important thing is not just detecting all polyps but the polyps we care about, which are adenomas, and doing so without increasing the false positive rate,” said Dr. Shaukat.

The adenoma detection rate was 43.9% for the standard procedure and 47.8% for the computer-assisted procedure. This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr. Shaukat argued that the adenoma detection rate is not the best measure of success, because endoscopists sometimes stop looking for polyps once they find one.

The overall sessile serrated lesion detection rate for the standard colonoscopies was 16.0% versus 12.6% for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which also was not statistically significant.

Next steps

This study is important because it was a large, multicenter trial in the United States, said Omer Ahmad, BSc, MBBS, MRCP, a gastroenterologist and clinical researcher at University College London, who was not involved in the study. Most of the trials of AI have been in China or Europe. “It was very important just to see this replicated in the U.S. population.”

The average procedure time was 15.41 minutes for the standard colonoscopies versus 15.82 minutes for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which was not statistically different.

“It is important to note that the studies so far suggest that false positives do not have a significant impact on workflow,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The next crucial step in evaluating AI colonoscopy will be to track the effects over the long term, said Dr. Shaukat.

“As these technologies get approved and we see them in practice, we need to see that it’s leading to some outcome, like reduced colon cancer,” she said.

That also may be necessary before payers in the United States are willing to pay the additional cost for this technology, she added.

In the meantime, Dr. Ahmad said computer assistance is improving his own colonoscopies.

“I have found the systems have spotted some polyps that I may have otherwise missed,” he said. “There is a false positive rate, but for me, it doesn’t distract from my workflow.”

He believes the systems will be particularly helpful in improving the performance of less-skilled endoscopists.

He is also looking forward to systems that can help complete the reports needed at the end of each colonoscopy. “Most of us dislike having to write a laborious report and having to code everything at the end of the procedure,” he said.

The study was funded by Iterative Scopes. Dr. Shaukat reported having received research funding to her institution for the current study from Iterative Scopes and consulting fees from Freenome and Medtronic. Dr. Ahmad reports receiving speaker fees from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology/Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new artificial intelligence (AI) system can help expert endoscopists improve their colonoscopies, a new study indicates.

Endoscopists using the computer program SKOUT (Iterative Scopes) achieved a 27% better detection rate of adenomas per colonoscopy, compared with endoscopists working without computer assistance, said lead author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at New York University.

The study showed that AI colonoscopy systems can work in a routine population of U.S. patients, Dr. Shaukat said in an interview.

“As gastroenterologists, we are very excited,” she said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology and was presented at the annual Digestive Disease® Week.

Previous research has shown that experienced endoscopists miss many polyps. To improve their detection rate, multiple companies have used machine learning to develop algorithms to identify suspicious areas.

“Once the computer sees the polyp, it puts a bounding box around it,” said Dr. Shaukat. “It draws the attention of the endoscopist to it. It assists the endoscopist but doesn’t replace the endoscopist.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two such systems: EndoScreener (Wision AI) and GI Genius (Cosmo Pharmaceuticals).

The SKOUT algorithm was trained on 3,616 full-length colonoscopy procedure videos from multiple centers. In bench testing, it achieved a 93.5% polyp-level true positive rate and a 2.3% false positive rate.

Randomized trial pits AI against standard procedure

To see how well the system works in the clinic, Dr. Shaukat and colleagues recruited 22 U.S. board-certified gastroenterologists from five academic and community centers. The gastroenterologists all had a minimum adenoma detection rate of 25%, defined as the number of colonoscopies in which at least one adenoma is found, divided by the number of colonoscopies performed. All the gastroenterologists had performed a minimum of 1,000 colonoscopy procedures.

The researchers randomly assigned 682 patients to undergo colonoscopy with the SKOUT and 677 to undergo colonoscopy using the standard procedure. The patients were aged 40 years or older and were scheduled for either screening or surveillance.

The endoscopists who received computer assistance detected 1.05 adenomas per colonoscopy versus 0.83 for those who did not have computer assistance, a statistically significant difference.

The proportion of resections with clinically significant histology was 71.7% with standard colonoscopies versus 67.4% with computer-assisted colonoscopies. This fell within the 14% margin that the researchers had set to show noninferiority for the computer system.

“The important thing is not just detecting all polyps but the polyps we care about, which are adenomas, and doing so without increasing the false positive rate,” said Dr. Shaukat.

The adenoma detection rate was 43.9% for the standard procedure and 47.8% for the computer-assisted procedure. This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr. Shaukat argued that the adenoma detection rate is not the best measure of success, because endoscopists sometimes stop looking for polyps once they find one.

The overall sessile serrated lesion detection rate for the standard colonoscopies was 16.0% versus 12.6% for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which also was not statistically significant.

Next steps

This study is important because it was a large, multicenter trial in the United States, said Omer Ahmad, BSc, MBBS, MRCP, a gastroenterologist and clinical researcher at University College London, who was not involved in the study. Most of the trials of AI have been in China or Europe. “It was very important just to see this replicated in the U.S. population.”

The average procedure time was 15.41 minutes for the standard colonoscopies versus 15.82 minutes for the computer-assisted colonoscopies, which was not statistically different.

“It is important to note that the studies so far suggest that false positives do not have a significant impact on workflow,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The next crucial step in evaluating AI colonoscopy will be to track the effects over the long term, said Dr. Shaukat.

“As these technologies get approved and we see them in practice, we need to see that it’s leading to some outcome, like reduced colon cancer,” she said.

That also may be necessary before payers in the United States are willing to pay the additional cost for this technology, she added.

In the meantime, Dr. Ahmad said computer assistance is improving his own colonoscopies.

“I have found the systems have spotted some polyps that I may have otherwise missed,” he said. “There is a false positive rate, but for me, it doesn’t distract from my workflow.”

He believes the systems will be particularly helpful in improving the performance of less-skilled endoscopists.

He is also looking forward to systems that can help complete the reports needed at the end of each colonoscopy. “Most of us dislike having to write a laborious report and having to code everything at the end of the procedure,” he said.

The study was funded by Iterative Scopes. Dr. Shaukat reported having received research funding to her institution for the current study from Iterative Scopes and consulting fees from Freenome and Medtronic. Dr. Ahmad reports receiving speaker fees from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology/Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

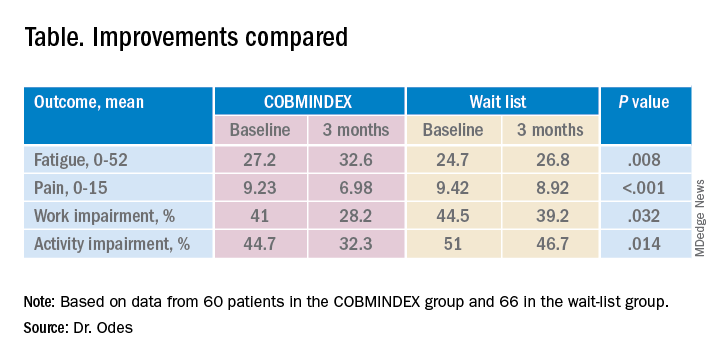

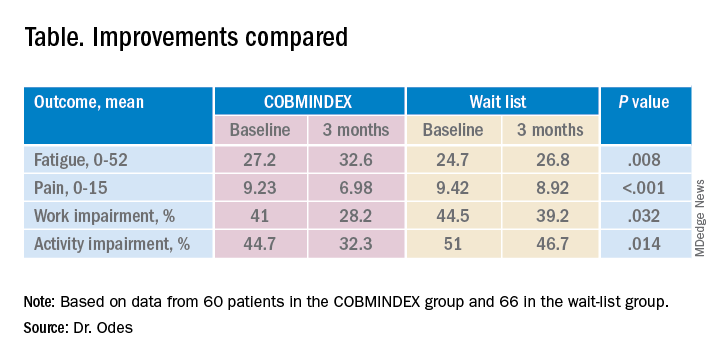

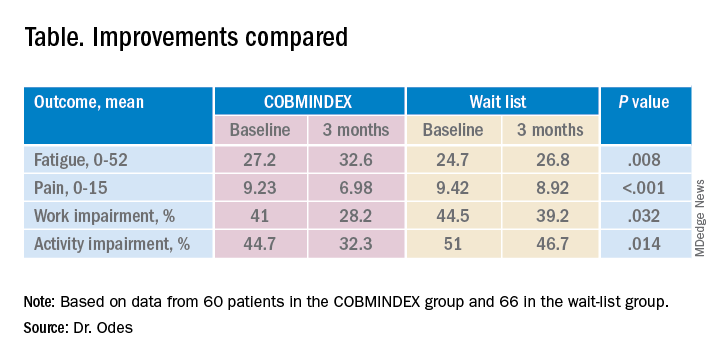

Psychological intervention looks promising in Crohn’s disease

SAN DIEGO – A combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness meditation could reduce pain and fatigue from Crohn’s disease, researchers say.

Patients who followed the program not only felt better but were also more often able to show up for work and leisure activities, compared with a control group assigned to a wait list, said Shmuel Odes, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba, Israel. He presented the finding at Digestive Diseases Week® (DDW) 2022.

Psychological and social factors affect the gut and vice versa, Dr. Odes said. Yet many inflammatory bowel disease clinics overlook psychological interventions.

To address these issues, Dr. Odes and colleagues developed cognitive-behavioral– and mindfulness-based stress reduction (COBMINDEX) training, which can be taught by clinical social workers over the Internet. “The patient learns to relax,” Dr. Odes told MDedge News. “He learns not to fight his condition.”

In a previous paper, published in the journal Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Dr. Odes and colleagues reported that patients who learned the technique showed improvement on a variety of psychological and quality-of-life measures, accompanied by changes in inflammatory cytokines and cortisol.

In a follow-up analysis presented here, the researchers looked at measures of pain and fatigue and then examined whether these were associated with productivity at work and other daily activities.

The study investigators randomly assigned 72 patients to an intervention group who got COBMINDEX training right away, and another 70 to a control group assigned to a wait list of 12 weeks before they could get the training. At baseline, the two groups were not significantly different in any demographic or clinical variable the researchers could find.

Social workers provided COBMINDEX training for the patients in seven 60-minute session over 12 weeks. Five of the sessions were devoted to cognitive-behavioral therapy and two to mindfulness-based stress reduction. The social workers asked the patients to do exercises at least once a day and report outcomes through an app.

Twelve patients dropped out of the COBMINDEX group and four dropped from the wait-list group because of lack of interest, time constraints, pregnancy, or illness.

The researchers created a composite score with a 0-15 scale (with higher scores indicating greater pain) from three pain items from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index for Crohn’s Disease, the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, and the 12-Item Short Form Survey.

To measure fatigue, they used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, which has a 0-52 scale, with lower scores indicating greater fatigue.

To measure impairment while working and other daily activities, they used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Crohn’s Disease. Scores on this measure are expressed as a percentage, with higher values indicating greater impairment.

Both the COBMINDEX and the wait-list groups improved on all these scales, but the improvements were significantly greater for the COBMINDEX group.

Through statistical analysis, the researchers found that the improvements in pain and fatigue indirectly caused the improvements in work and activity impairment, and that pain and fatigue improvements made independent contributions of similar magnitudes. COBMINDEX did not directly improve work or activity.

Psychological interventions are too often overlooked in Crohn’s disease, said the session comoderator Paul Moayyedi, MD, a professor of gastroenterology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “We need to realize how important this is to patients and urgently make this available,” he told MDedge.

A variety of interventions are being researched, and this study makes an important contribution, he said. However, he questioned whether people on a wait list can serve as an adequate control. “If you have to wait for something, you tend to have more pain, and you could have less productivity just because of waiting,” he said. “Ideally they should do a randomized trial with a sham intervention, not a wait list.”

Dr. Odes responded that it is very difficult to recruit people to a trial if they only have a 50% chance of getting a real treatment. And he noted that the people on the wait list in this trial did not show any signs of increased symptoms.

Physicians wanting to provide psychological help to their Crohn’s disease patients can refer them to social workers or psychotherapists, Dr. Odes said, but these professionals may lack training for applying cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction to patients with Crohn’s disease. His team hopes to make an app publicly available soon.

Neither Dr. Odes nor Dr. Moayyedi reported any relevant financial interests. The study was supported by a grant from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

SAN DIEGO – A combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness meditation could reduce pain and fatigue from Crohn’s disease, researchers say.

Patients who followed the program not only felt better but were also more often able to show up for work and leisure activities, compared with a control group assigned to a wait list, said Shmuel Odes, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba, Israel. He presented the finding at Digestive Diseases Week® (DDW) 2022.

Psychological and social factors affect the gut and vice versa, Dr. Odes said. Yet many inflammatory bowel disease clinics overlook psychological interventions.

To address these issues, Dr. Odes and colleagues developed cognitive-behavioral– and mindfulness-based stress reduction (COBMINDEX) training, which can be taught by clinical social workers over the Internet. “The patient learns to relax,” Dr. Odes told MDedge News. “He learns not to fight his condition.”

In a previous paper, published in the journal Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Dr. Odes and colleagues reported that patients who learned the technique showed improvement on a variety of psychological and quality-of-life measures, accompanied by changes in inflammatory cytokines and cortisol.

In a follow-up analysis presented here, the researchers looked at measures of pain and fatigue and then examined whether these were associated with productivity at work and other daily activities.

The study investigators randomly assigned 72 patients to an intervention group who got COBMINDEX training right away, and another 70 to a control group assigned to a wait list of 12 weeks before they could get the training. At baseline, the two groups were not significantly different in any demographic or clinical variable the researchers could find.

Social workers provided COBMINDEX training for the patients in seven 60-minute session over 12 weeks. Five of the sessions were devoted to cognitive-behavioral therapy and two to mindfulness-based stress reduction. The social workers asked the patients to do exercises at least once a day and report outcomes through an app.

Twelve patients dropped out of the COBMINDEX group and four dropped from the wait-list group because of lack of interest, time constraints, pregnancy, or illness.

The researchers created a composite score with a 0-15 scale (with higher scores indicating greater pain) from three pain items from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index for Crohn’s Disease, the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, and the 12-Item Short Form Survey.

To measure fatigue, they used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, which has a 0-52 scale, with lower scores indicating greater fatigue.

To measure impairment while working and other daily activities, they used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Crohn’s Disease. Scores on this measure are expressed as a percentage, with higher values indicating greater impairment.

Both the COBMINDEX and the wait-list groups improved on all these scales, but the improvements were significantly greater for the COBMINDEX group.

Through statistical analysis, the researchers found that the improvements in pain and fatigue indirectly caused the improvements in work and activity impairment, and that pain and fatigue improvements made independent contributions of similar magnitudes. COBMINDEX did not directly improve work or activity.

Psychological interventions are too often overlooked in Crohn’s disease, said the session comoderator Paul Moayyedi, MD, a professor of gastroenterology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “We need to realize how important this is to patients and urgently make this available,” he told MDedge.