User login

Generalized Essential Telangiectasia Treated With Pulsed Dye Laser

To the Editor:

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a rare, benign, and progressive primary cutaneous disease manifesting as telangiectases of the skin without systemic symptoms. It is unique in that it has widespread distribution on the body. Generalized essential telangiectasia more commonly affects women, usually in the fourth decade of life. The telangiectases most frequently appear on the legs, advancing over time to involve the trunk and arms and presenting in several patterns, including diffuse, macular, plaquelike, discrete, or confluent. Although GET typically is asymptomatic, numbness, tingling, and burning of the involved areas have been reported.1 Treatment modalities for GET vary, though pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy is most common. We report the case of a 40-year-old woman with a 5-year history of GET who was treated successfully with PDL.

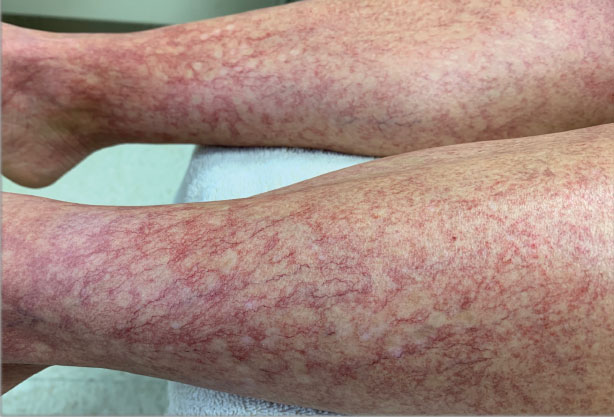

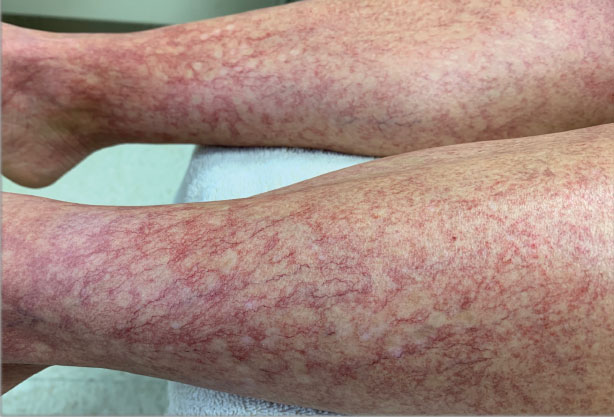

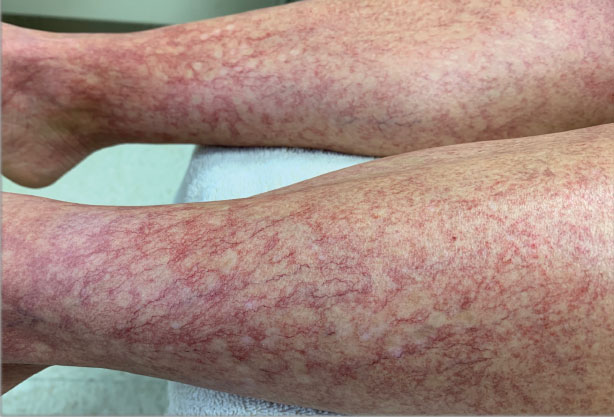

A 40-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive prominence of blood vessels involving the dorsal aspects of the feet of 5 years’ duration. The prominent vessels had spread to involve the legs (Figure 1), buttocks, lower abdomen, forearms, and medial upper arms. The patient denied any personal history of bleeding disorders or family history of inherited conditions associated with visceral vascular malformations, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Notably, magnetic resonance imaging of the liver approximately 3 weeks prior to initiating treatment with PDL demonstrated multiple hepatic lesions consistent with hemangiomas. The patient reported an occasional tingling sensation in the feet. She was otherwise asymptomatic but did report psychological distress associated with the skin changes.

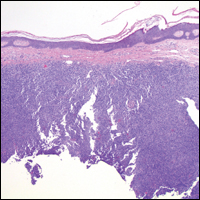

Punch biopsies from the right lower leg and right buttock demonstrated increased vascularity of the dermis, a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and mild edema of the upper dermis without evidence of vasculitis. Autoimmune and coagulopathy workups were negative. The clinical and pathological findings were most consistent with GET.

Over the next 2.5 years, the patient underwent treatment with doxycycline and a series of 16 treatments with PDL (fluence, 6–12 J/cm2; pulse width, 10 milliseconds) with a positive cosmetic response. Considerable improvement in the lower legs was noted after 2 years of treatment with PDL (Figure 2).

Recurrence of GET was noted between PDL treatments, which led to progression of the disease process; all treated sites showed slow recurrence of lesions within several months after treatment. After 2 years, doxycycline was discontinued because of a perceived lack of continued benefit and the patient’s desire for alternative therapy. She was started on a 3-month trial of supplementation with ascorbic acid and rutin (or rutoside, a bioflavinoid), without noticeable improvement.

The diffuse distribution of dramatic telangiectases in GET makes treatment difficult. Standard treatments are not well established or studied due to the rarity of the condition. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms treatment and generalized essential telangiectasias demonstrated several attempted treatment modalities for GET with varying success. In 4 cases in which PDL was used,2-5 a positive cosmetic response was noted, similar to what was seen in our patient. In 1 of the 4 cases, conservative management with ascorbic acid and compression stockings was unsuccessful; however, 6-mercaptopurine, used to treat that patient’s ulcerative colitis, incidentally resulted in resolution of GET.2 In 2 cases, response was maintained at 1.5-year follow-up.3,5 Two cases noted successful treatment with acyclovir,6,7 and 2 more demonstrated successful treatment with systemic ketoconazole.6,8 Some improvement was reported with oral doxycycline or tetracycline in 2 cases.9,10 Sclerotherapy improved the cosmetic appearance of telangiectases in one patient but was unsustainable because of the pain associated with the procedure.11 Nd:YAG laser therapy was effective in one case12; however, the patient experienced relapse at 6-month follow-up—similar to what we observed in our patient. Three patients treated with intense pulsed light therapy experienced results that were maintained at 2-year follow-up.13

Generalized essential telangiectasia generally is considered a skin-limited disease without systemic manifestations, but 2 reports11,14 described its association with gastric antral vascular ectasia—known as watermelon stomach. Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign liver lesions; however, the findings on magnetic resonance imaging in our patient, in combination with the 2 reported cases of watermelon stomach, suggest that the vascular changes of GET might extend below the skin.

Of the cases we reviewed, our patient had the longest reported duration of PDL treatment and follow-up for GET in which a successful, albeit transient, response was demonstrated. Our review of the literature revealed other reports of success with PDL and intense pulsed light therapy; results were maintained in some patients, while disease relapsed in others. Further studies are needed to understand why results are maintained in some but not all patients.

Although the cost of PDL as a cosmetic procedure must be taken into consideration when planning treatment of GET, we conclude that it is a safe option that can be effective until other treatment options are established to control the disease.

- McGrae JD Jr, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120019015

- Glazer AM, Sofen BD, Rigel DS, et al. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with 6-mercaptopurine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:280-282.

- B, M, Boixeda P, et al. Progressive ascending telangiectasia treated with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1997;21:413-416. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1997)21:5<413::aid-lsm1>3.0.co;2-t

- Buscaglia DA, Conte ET. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2001;67:107-108.

- Powell E, Markus R, Malone CH. Generalized essential telangiectasia treated with PDL. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1086-1087. doi:10.1111/jocd.13938

- Ali MM, Teimory M, Sarhan M. Generalized essential telangiectasia with conjunctival involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:781-782. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02217.x

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Essential progressive telangiectasia in an autoimmune setting: successful treatment with acyclovir. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5 pt 2):1094-1096. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70303-0

- Shelley WB, Fierer JA. Focal intravascular coagulation in progressive ascending telangiectasia: ultrastructural studies of ketoconazole-induced involution of vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(5 pt 2):876-887. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80439-9

- Wiznia LE, Steuer AB, Penn LA, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia [published online December 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/D32412042395

- Shelley WB. Essential progressive telangiectasia. successful treatment with tetracycline. JAMA. 1971;216:1343-1344.

- Checketts SR, Burton PS, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia in the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 2):321-325.

- Gambichler T, Avermaete A, Wilmert M, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia successfully treated with high-energy, long-pulse, frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:355-357. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00307.x

- -Torres R, del Pozo J, de la Torre C, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia: a report of three cases treated using an intense pulsed light system. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:192-193.

- Tetart F, Lorthioir A, Girszyn N, et al. Watermelon stomach revealing generalized essential telangiectasia. Intern Med J. 2009;39:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02048.x

To the Editor:

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a rare, benign, and progressive primary cutaneous disease manifesting as telangiectases of the skin without systemic symptoms. It is unique in that it has widespread distribution on the body. Generalized essential telangiectasia more commonly affects women, usually in the fourth decade of life. The telangiectases most frequently appear on the legs, advancing over time to involve the trunk and arms and presenting in several patterns, including diffuse, macular, plaquelike, discrete, or confluent. Although GET typically is asymptomatic, numbness, tingling, and burning of the involved areas have been reported.1 Treatment modalities for GET vary, though pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy is most common. We report the case of a 40-year-old woman with a 5-year history of GET who was treated successfully with PDL.

A 40-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive prominence of blood vessels involving the dorsal aspects of the feet of 5 years’ duration. The prominent vessels had spread to involve the legs (Figure 1), buttocks, lower abdomen, forearms, and medial upper arms. The patient denied any personal history of bleeding disorders or family history of inherited conditions associated with visceral vascular malformations, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Notably, magnetic resonance imaging of the liver approximately 3 weeks prior to initiating treatment with PDL demonstrated multiple hepatic lesions consistent with hemangiomas. The patient reported an occasional tingling sensation in the feet. She was otherwise asymptomatic but did report psychological distress associated with the skin changes.

Punch biopsies from the right lower leg and right buttock demonstrated increased vascularity of the dermis, a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and mild edema of the upper dermis without evidence of vasculitis. Autoimmune and coagulopathy workups were negative. The clinical and pathological findings were most consistent with GET.

Over the next 2.5 years, the patient underwent treatment with doxycycline and a series of 16 treatments with PDL (fluence, 6–12 J/cm2; pulse width, 10 milliseconds) with a positive cosmetic response. Considerable improvement in the lower legs was noted after 2 years of treatment with PDL (Figure 2).

Recurrence of GET was noted between PDL treatments, which led to progression of the disease process; all treated sites showed slow recurrence of lesions within several months after treatment. After 2 years, doxycycline was discontinued because of a perceived lack of continued benefit and the patient’s desire for alternative therapy. She was started on a 3-month trial of supplementation with ascorbic acid and rutin (or rutoside, a bioflavinoid), without noticeable improvement.

The diffuse distribution of dramatic telangiectases in GET makes treatment difficult. Standard treatments are not well established or studied due to the rarity of the condition. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms treatment and generalized essential telangiectasias demonstrated several attempted treatment modalities for GET with varying success. In 4 cases in which PDL was used,2-5 a positive cosmetic response was noted, similar to what was seen in our patient. In 1 of the 4 cases, conservative management with ascorbic acid and compression stockings was unsuccessful; however, 6-mercaptopurine, used to treat that patient’s ulcerative colitis, incidentally resulted in resolution of GET.2 In 2 cases, response was maintained at 1.5-year follow-up.3,5 Two cases noted successful treatment with acyclovir,6,7 and 2 more demonstrated successful treatment with systemic ketoconazole.6,8 Some improvement was reported with oral doxycycline or tetracycline in 2 cases.9,10 Sclerotherapy improved the cosmetic appearance of telangiectases in one patient but was unsustainable because of the pain associated with the procedure.11 Nd:YAG laser therapy was effective in one case12; however, the patient experienced relapse at 6-month follow-up—similar to what we observed in our patient. Three patients treated with intense pulsed light therapy experienced results that were maintained at 2-year follow-up.13

Generalized essential telangiectasia generally is considered a skin-limited disease without systemic manifestations, but 2 reports11,14 described its association with gastric antral vascular ectasia—known as watermelon stomach. Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign liver lesions; however, the findings on magnetic resonance imaging in our patient, in combination with the 2 reported cases of watermelon stomach, suggest that the vascular changes of GET might extend below the skin.

Of the cases we reviewed, our patient had the longest reported duration of PDL treatment and follow-up for GET in which a successful, albeit transient, response was demonstrated. Our review of the literature revealed other reports of success with PDL and intense pulsed light therapy; results were maintained in some patients, while disease relapsed in others. Further studies are needed to understand why results are maintained in some but not all patients.

Although the cost of PDL as a cosmetic procedure must be taken into consideration when planning treatment of GET, we conclude that it is a safe option that can be effective until other treatment options are established to control the disease.

To the Editor:

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a rare, benign, and progressive primary cutaneous disease manifesting as telangiectases of the skin without systemic symptoms. It is unique in that it has widespread distribution on the body. Generalized essential telangiectasia more commonly affects women, usually in the fourth decade of life. The telangiectases most frequently appear on the legs, advancing over time to involve the trunk and arms and presenting in several patterns, including diffuse, macular, plaquelike, discrete, or confluent. Although GET typically is asymptomatic, numbness, tingling, and burning of the involved areas have been reported.1 Treatment modalities for GET vary, though pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy is most common. We report the case of a 40-year-old woman with a 5-year history of GET who was treated successfully with PDL.

A 40-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive prominence of blood vessels involving the dorsal aspects of the feet of 5 years’ duration. The prominent vessels had spread to involve the legs (Figure 1), buttocks, lower abdomen, forearms, and medial upper arms. The patient denied any personal history of bleeding disorders or family history of inherited conditions associated with visceral vascular malformations, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Notably, magnetic resonance imaging of the liver approximately 3 weeks prior to initiating treatment with PDL demonstrated multiple hepatic lesions consistent with hemangiomas. The patient reported an occasional tingling sensation in the feet. She was otherwise asymptomatic but did report psychological distress associated with the skin changes.

Punch biopsies from the right lower leg and right buttock demonstrated increased vascularity of the dermis, a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and mild edema of the upper dermis without evidence of vasculitis. Autoimmune and coagulopathy workups were negative. The clinical and pathological findings were most consistent with GET.

Over the next 2.5 years, the patient underwent treatment with doxycycline and a series of 16 treatments with PDL (fluence, 6–12 J/cm2; pulse width, 10 milliseconds) with a positive cosmetic response. Considerable improvement in the lower legs was noted after 2 years of treatment with PDL (Figure 2).

Recurrence of GET was noted between PDL treatments, which led to progression of the disease process; all treated sites showed slow recurrence of lesions within several months after treatment. After 2 years, doxycycline was discontinued because of a perceived lack of continued benefit and the patient’s desire for alternative therapy. She was started on a 3-month trial of supplementation with ascorbic acid and rutin (or rutoside, a bioflavinoid), without noticeable improvement.

The diffuse distribution of dramatic telangiectases in GET makes treatment difficult. Standard treatments are not well established or studied due to the rarity of the condition. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms treatment and generalized essential telangiectasias demonstrated several attempted treatment modalities for GET with varying success. In 4 cases in which PDL was used,2-5 a positive cosmetic response was noted, similar to what was seen in our patient. In 1 of the 4 cases, conservative management with ascorbic acid and compression stockings was unsuccessful; however, 6-mercaptopurine, used to treat that patient’s ulcerative colitis, incidentally resulted in resolution of GET.2 In 2 cases, response was maintained at 1.5-year follow-up.3,5 Two cases noted successful treatment with acyclovir,6,7 and 2 more demonstrated successful treatment with systemic ketoconazole.6,8 Some improvement was reported with oral doxycycline or tetracycline in 2 cases.9,10 Sclerotherapy improved the cosmetic appearance of telangiectases in one patient but was unsustainable because of the pain associated with the procedure.11 Nd:YAG laser therapy was effective in one case12; however, the patient experienced relapse at 6-month follow-up—similar to what we observed in our patient. Three patients treated with intense pulsed light therapy experienced results that were maintained at 2-year follow-up.13

Generalized essential telangiectasia generally is considered a skin-limited disease without systemic manifestations, but 2 reports11,14 described its association with gastric antral vascular ectasia—known as watermelon stomach. Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign liver lesions; however, the findings on magnetic resonance imaging in our patient, in combination with the 2 reported cases of watermelon stomach, suggest that the vascular changes of GET might extend below the skin.

Of the cases we reviewed, our patient had the longest reported duration of PDL treatment and follow-up for GET in which a successful, albeit transient, response was demonstrated. Our review of the literature revealed other reports of success with PDL and intense pulsed light therapy; results were maintained in some patients, while disease relapsed in others. Further studies are needed to understand why results are maintained in some but not all patients.

Although the cost of PDL as a cosmetic procedure must be taken into consideration when planning treatment of GET, we conclude that it is a safe option that can be effective until other treatment options are established to control the disease.

- McGrae JD Jr, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120019015

- Glazer AM, Sofen BD, Rigel DS, et al. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with 6-mercaptopurine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:280-282.

- B, M, Boixeda P, et al. Progressive ascending telangiectasia treated with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1997;21:413-416. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1997)21:5<413::aid-lsm1>3.0.co;2-t

- Buscaglia DA, Conte ET. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2001;67:107-108.

- Powell E, Markus R, Malone CH. Generalized essential telangiectasia treated with PDL. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1086-1087. doi:10.1111/jocd.13938

- Ali MM, Teimory M, Sarhan M. Generalized essential telangiectasia with conjunctival involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:781-782. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02217.x

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Essential progressive telangiectasia in an autoimmune setting: successful treatment with acyclovir. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5 pt 2):1094-1096. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70303-0

- Shelley WB, Fierer JA. Focal intravascular coagulation in progressive ascending telangiectasia: ultrastructural studies of ketoconazole-induced involution of vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(5 pt 2):876-887. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80439-9

- Wiznia LE, Steuer AB, Penn LA, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia [published online December 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/D32412042395

- Shelley WB. Essential progressive telangiectasia. successful treatment with tetracycline. JAMA. 1971;216:1343-1344.

- Checketts SR, Burton PS, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia in the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 2):321-325.

- Gambichler T, Avermaete A, Wilmert M, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia successfully treated with high-energy, long-pulse, frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:355-357. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00307.x

- -Torres R, del Pozo J, de la Torre C, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia: a report of three cases treated using an intense pulsed light system. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:192-193.

- Tetart F, Lorthioir A, Girszyn N, et al. Watermelon stomach revealing generalized essential telangiectasia. Intern Med J. 2009;39:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02048.x

- McGrae JD Jr, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120019015

- Glazer AM, Sofen BD, Rigel DS, et al. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with 6-mercaptopurine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:280-282.

- B, M, Boixeda P, et al. Progressive ascending telangiectasia treated with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1997;21:413-416. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1997)21:5<413::aid-lsm1>3.0.co;2-t

- Buscaglia DA, Conte ET. Successful treatment of generalized essential telangiectasia with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2001;67:107-108.

- Powell E, Markus R, Malone CH. Generalized essential telangiectasia treated with PDL. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1086-1087. doi:10.1111/jocd.13938

- Ali MM, Teimory M, Sarhan M. Generalized essential telangiectasia with conjunctival involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:781-782. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02217.x

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Essential progressive telangiectasia in an autoimmune setting: successful treatment with acyclovir. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5 pt 2):1094-1096. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70303-0

- Shelley WB, Fierer JA. Focal intravascular coagulation in progressive ascending telangiectasia: ultrastructural studies of ketoconazole-induced involution of vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(5 pt 2):876-887. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80439-9

- Wiznia LE, Steuer AB, Penn LA, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia [published online December 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/D32412042395

- Shelley WB. Essential progressive telangiectasia. successful treatment with tetracycline. JAMA. 1971;216:1343-1344.

- Checketts SR, Burton PS, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia in the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 2):321-325.

- Gambichler T, Avermaete A, Wilmert M, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia successfully treated with high-energy, long-pulse, frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:355-357. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00307.x

- -Torres R, del Pozo J, de la Torre C, et al. Generalized essential telangiectasia: a report of three cases treated using an intense pulsed light system. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:192-193.

- Tetart F, Lorthioir A, Girszyn N, et al. Watermelon stomach revealing generalized essential telangiectasia. Intern Med J. 2009;39:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02048.x

Practice Points

- Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a primary benign skin condition in which there is progressive development of telangiectases but a lack of systemic symptoms.

- Although patients should be assured that GET is a benign disease, its manifestation on the skin may cause negative psychologic impacts that should not be overlooked.

- Pulsed dye laser therapy does lead to improvement of the condition, but it does not prevent progression.

Metastatic Melanoma Mimicking Eruptive Keratoacanthomas

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

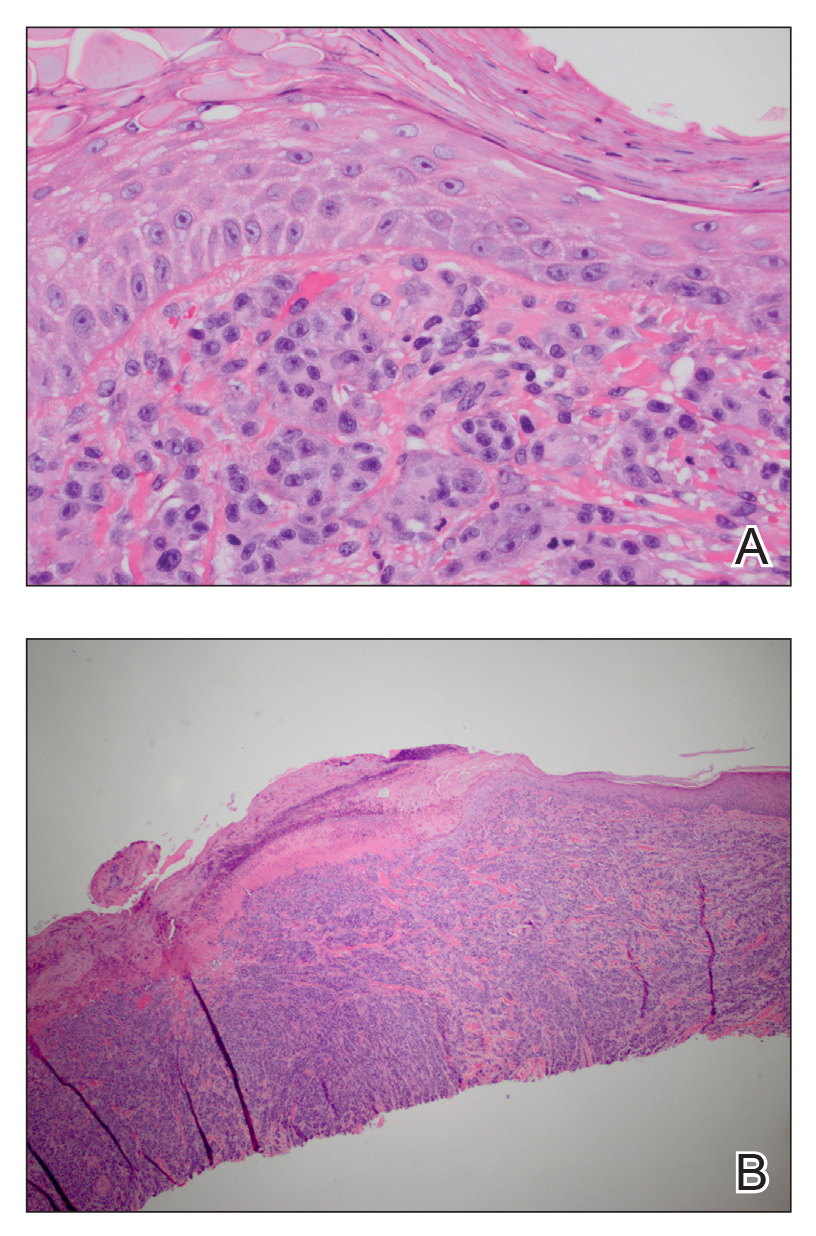

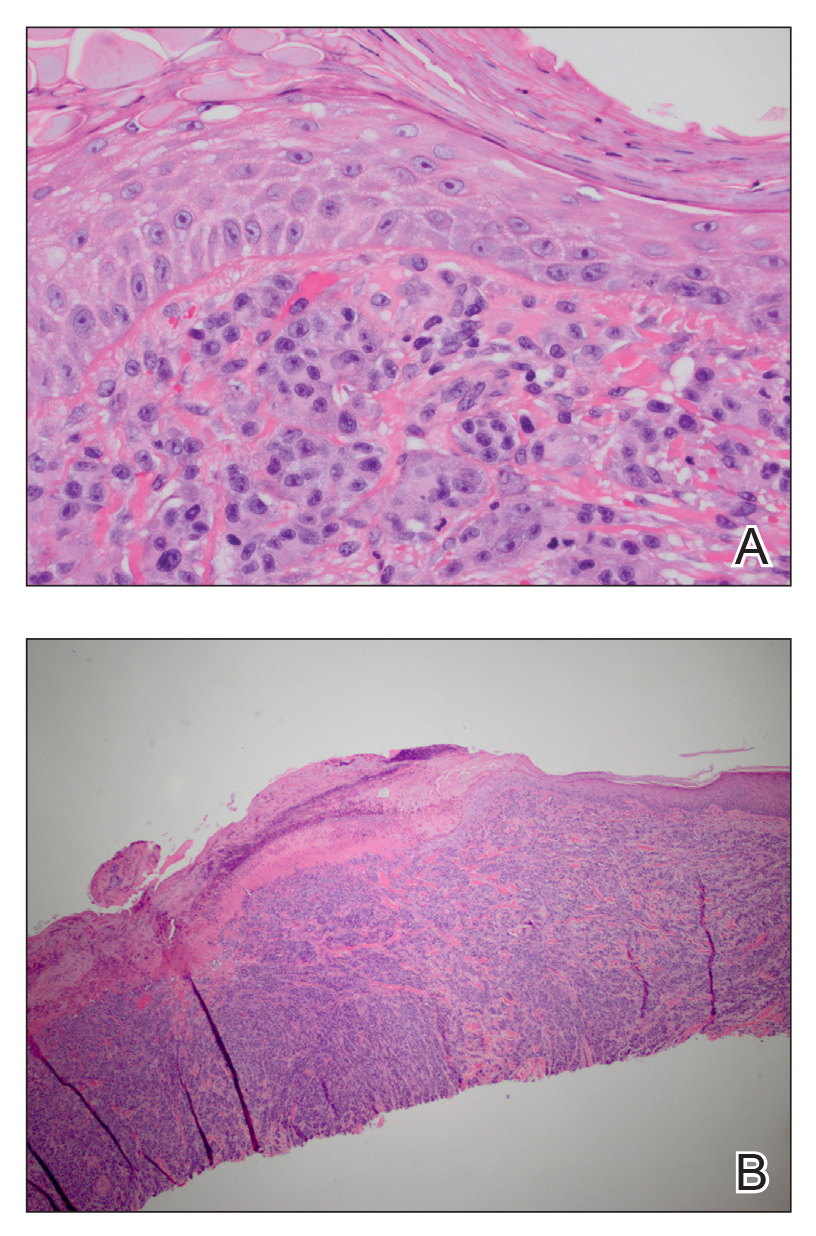

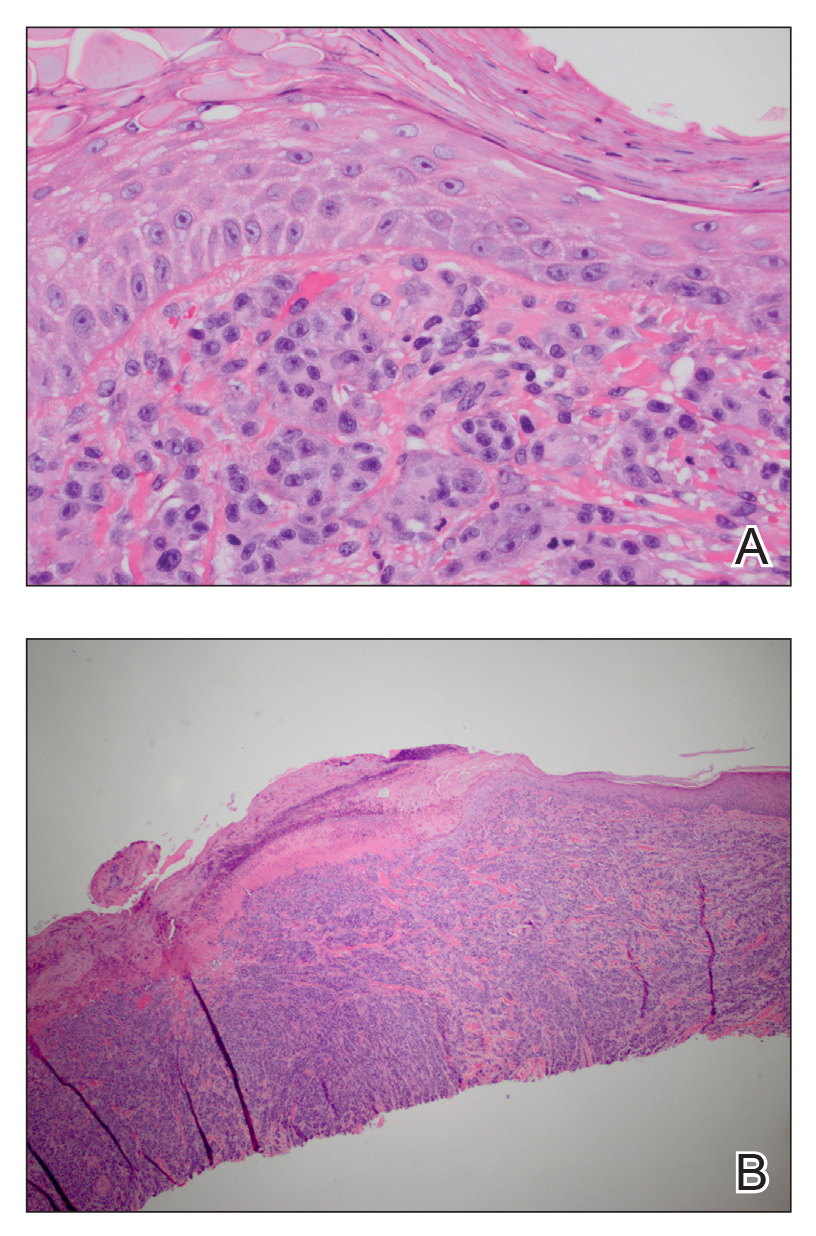

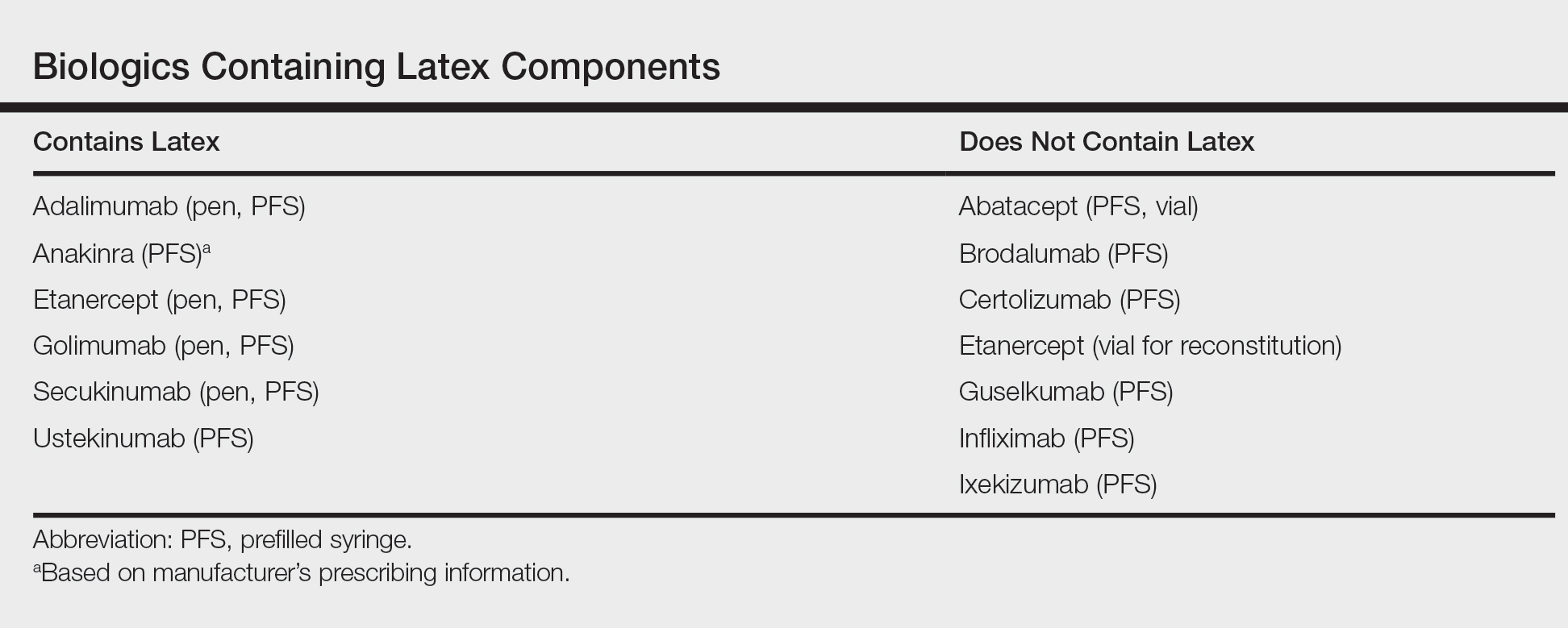

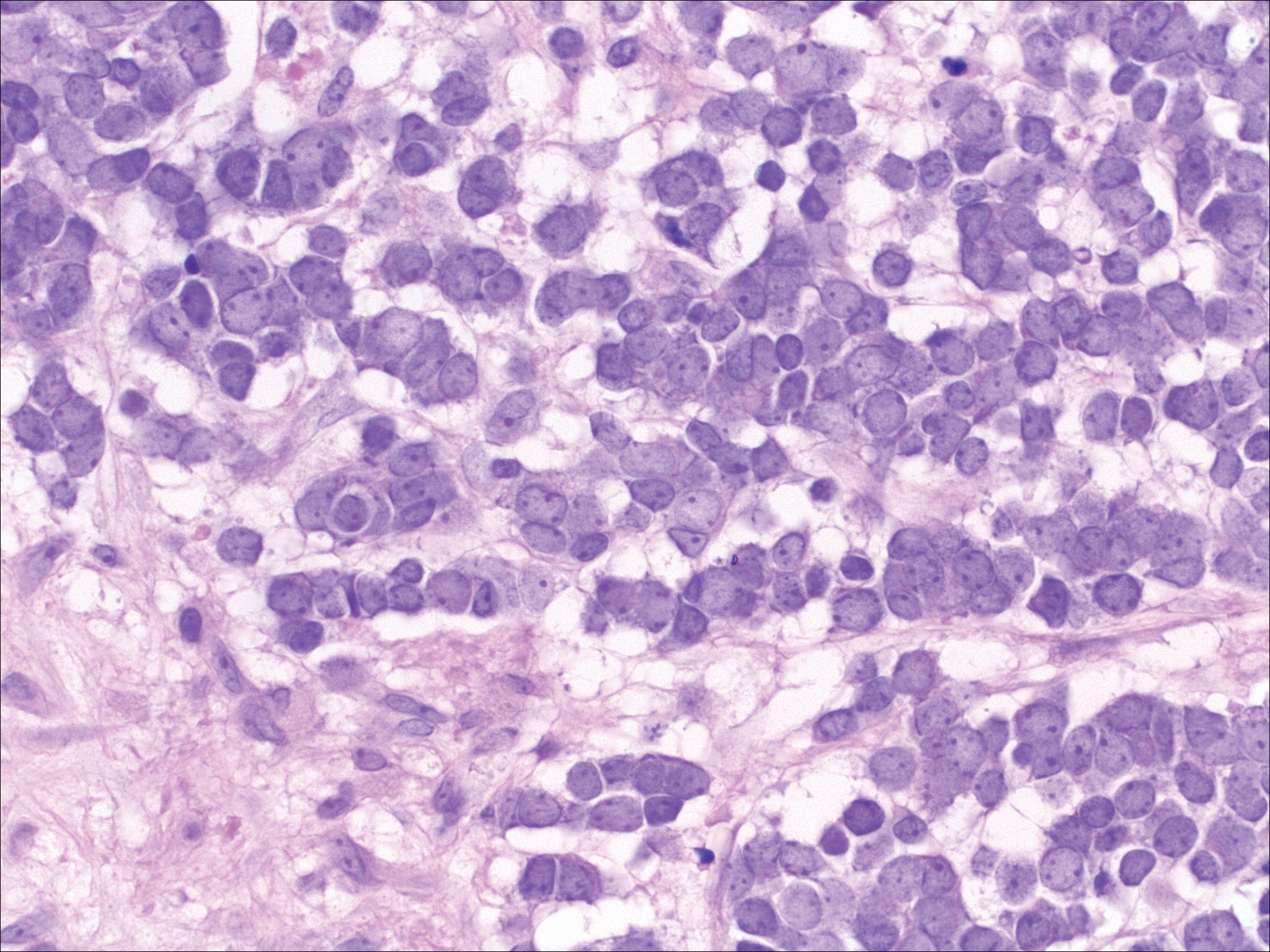

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastatic melanoma can have variable clinical presentations.

- Patients with a history of melanoma should be monitored closely with a low threshold for biopsy of new skin lesions.

Latex Hypersensitivity to Injection Devices for Biologic Therapies in Psoriasis Patients

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

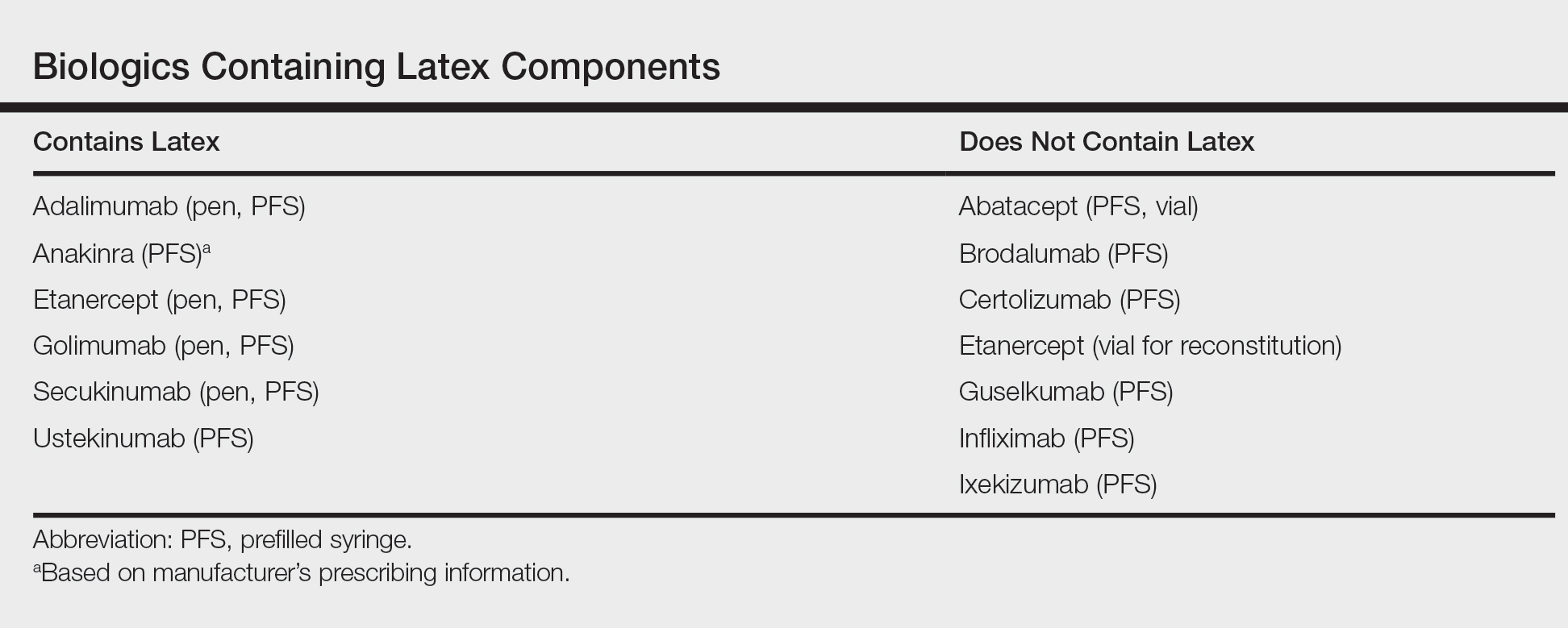

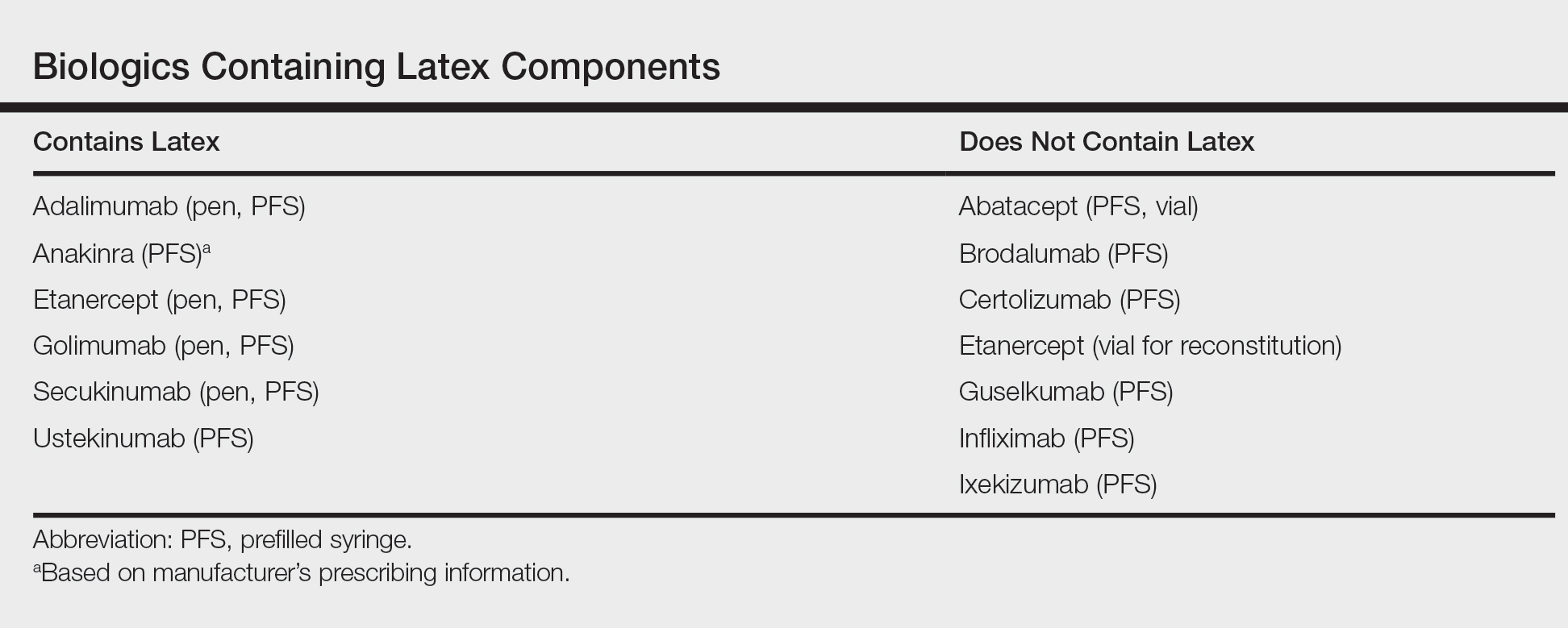

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

Erythematous Pearly Papule on the Chest

Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) are a diverse but rare group of cutaneous lymphoproliferative neoplasms that make up approximately 20% of the total number of hematolymphoid neoplasms primary to the skin.1 These lymphomas are comprised of neoplastic B cells in various stages of differentiation. As a whole, they are rare neoplasms that primarily involve the head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs.1 Clinically, patients present with nontender, compressible, solitary, red to violaceous papules or nodules. Most CBCLs are considered low-grade malignancies with nonaggressive behavior and excellent prognosis; however, the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, including but not limited to intravascular and leg type; lymphomatoid granulomatosis; and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma can act more aggressively.1

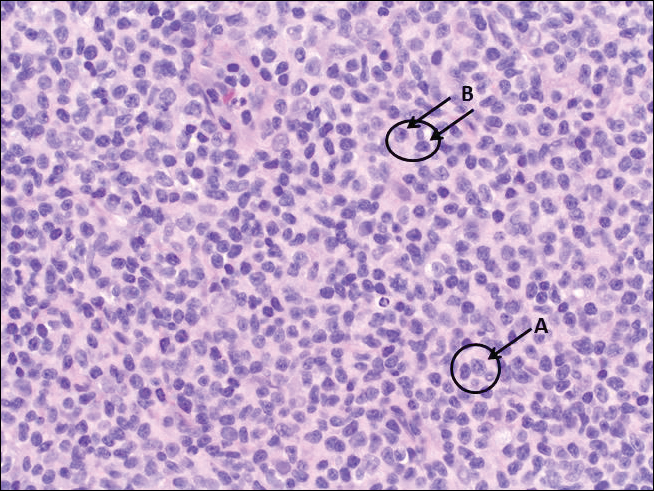

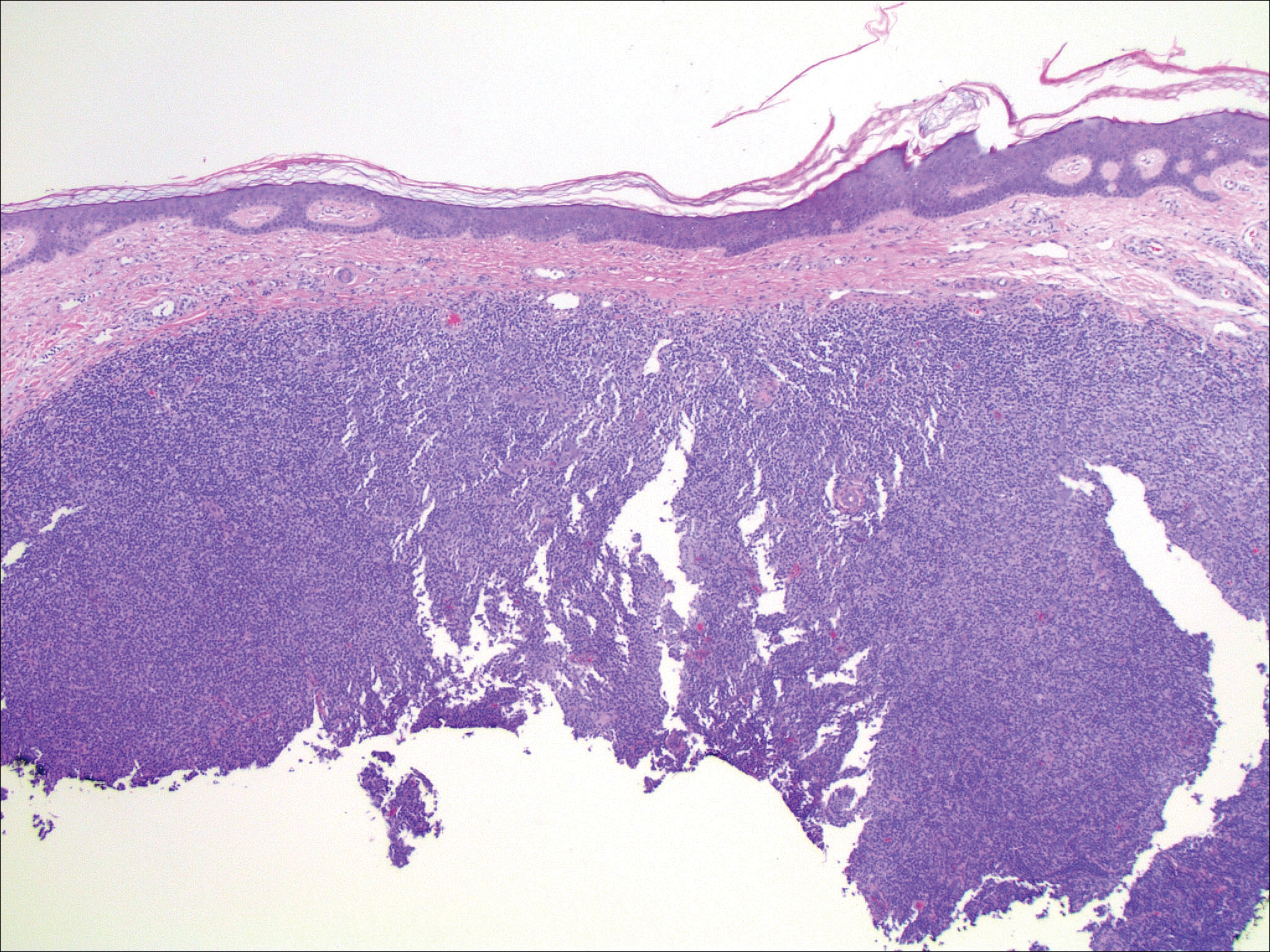

Histopathologic examination of primary CBCL generally reveals a relatively normal epidermis accompanied by a nodular to diffuse monomorphic lymphocytic cellular infiltrate in the dermis that can occasionally extend into the subcutaneous tissue (quiz image). Although not specific for CBCLs, oftentimes there is an acellular portion of the superficial papillary dermis known as a grenz zone that can serve as a histopathologic clue to the diagnosis of a cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The list of malignant B-cell neoplasms is extensive (eg, cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma), and few are seen in the skin.

The most common type of CBCL is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which is considered to be a tumor of mucosa-associated (or skin-associated) lymphoid tissue. It is characterized by a monomorphous population of small mature lymphocytes showing characteristics of the B cells of the marginal zone of the lymph node. Some cells have the features of centrocytes/centroblasts (Figure 1) demonstrated by slightly irregular or indented nuclei and generous amounts of cytoplasm. Larger and more pleomorphic cells such as immunoblasts are similarly noted (Figure 1). The quiz image and Figure 1 demonstrate a cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. A histomorphologic clue supporting a diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma over reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is a B-cell predominate (B- to T-cell ratio of at least 3 to 1) infiltrate that is comprised of marginal zone-type cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrating fewer differentiated B cells with light chain restriction may provide additional evidence that supports a clonal and potentially malignant process.

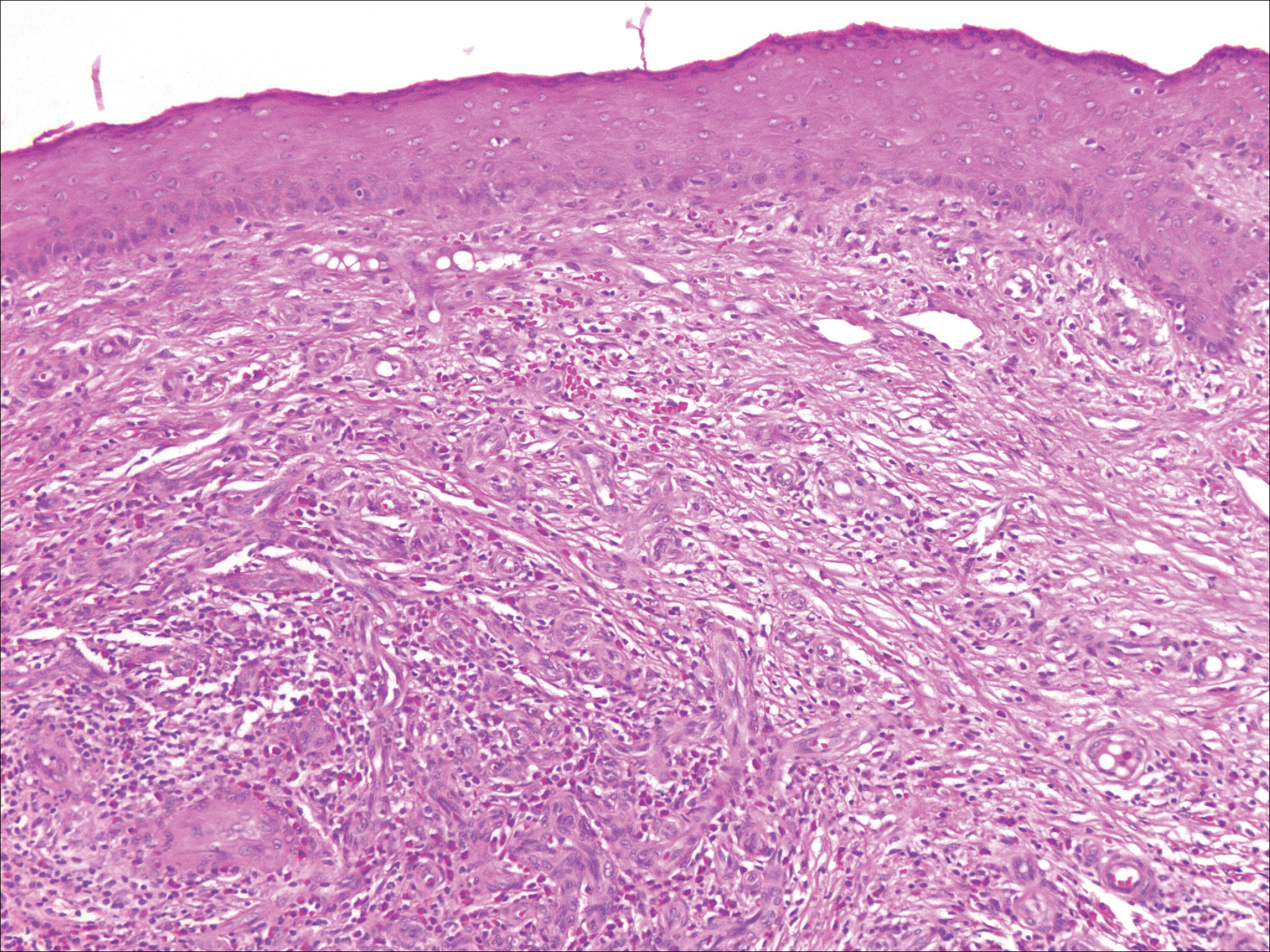

Erythematous to violaceous nodules on the head and neck of older individuals are characteristic of both granuloma faciale and CBCL. Histologically, granuloma faciale is characterized by a dense cellular infiltrate, often with a nodular outline, occupying the mid dermis.2 Granuloma faciale typically spares the immediate subepidermis and hair follicles, forming a grenz zone. The cellular infiltrate is polymorphic and consists of eosinophils and neutrophils with scattered plasma cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes in a vasculocentric distribution, eventually with chronic concentric fibrosis (Figure 2).

Leukemia cutis demonstrates a dermal infiltrate that contains atypical mononuclear cells (myeloblasts and myelocytes)(Figure 3).3 These markedly atypical mononuclear cells can have kidney bean-shaped nuclei and percolate through the dermal collagen, resembling single-file cells. They have increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and occasionally have prominent nucleoli. Correlation with immunophenotypic and cytochemical studies is required for specific typing of the leukemic infiltrate.

Similar to primary CBCL, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) consists of erythematous papules or nodules that can occur anywhere on the body. In contrast to CBCL, the lesions of LyP classically self-resolve. However, approximately 10% to 20% of patients develop a malignant lymphoma, with mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin disease, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma being the most commonly associated.