User login

Acute-onset quadriplegia with hyperreflexia

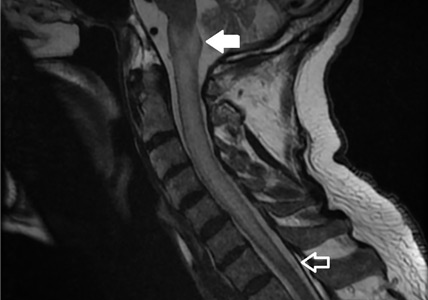

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern unmasked by severe musculoskeletal pain

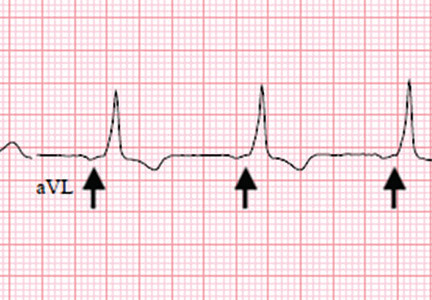

A 55-year-old man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with left-sided flank pain that had begun 3 days earlier. He described the pain as continuous, sharp, and aggravated by movement. He worked in construction, and before the pain started he had moved 8 sheets of drywall and lifted 5-gallon buckets of spackling compound. He denied any associated chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, cough, or lightheadedness. His family history included sudden cardiac death in 2 second-degree relatives.

On arrival in the emergency department, his vital signs were normal, as were the rest of the findings on physical examination except for reproducible point tenderness below the left scapula.

Laboratory workup revealed normal blood cell counts, liver enzymes, and kidney function. His initial troponin test was negative.

The patient was referred to an electrophysiologist for further evaluation, but he returned to his home country (Haiti) after discharge and was lost to follow-up.

WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE PATTERN VS SYNDROME

WPW syndrome is a disorder of the conduction system leading to preexcitation of the ventricles by an accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles. It is characterized by preexcitation manifested on electrocardiography and by symptomatic arrhythmias.

In contrast, the WPW pattern is defined only by preexcitation findings on electrocardiography without symptomatic arrhythmias. Patients with WPW syndrome can present with palpitation, dizziness, and syncope resulting from underlying arrhythmia.1 This is not seen in patients with the WPW pattern.

A short PR interval with or without delta waves can also be seen in the absence of an accessory pathway, eg, in hypoplastic left heart syndrome, atrioventricular canal defect, and Ebstein anomaly. These conditions are termed pseudopreexcitation syndrome.2

Our patient presented with severe musculoskeletal pain that precipitated the electrocardiographic changes of the WPW pattern and resolved with adequate pain control. The WPW pattern can be unmasked under different scenarios, including anesthesia, sympathomimetic drugs, and postoperatively.3–5

Catecholamine challenge has been used to unmask high-risk features in WPW syndrome.3 Our patient may have had a transient spike in catecholamine levels because of severe musculoskeletal pain, leading to unmasking of accessory pathways and resulting in the WPW pattern on electrocardiography.

Most patients with the WPW pattern experience no symptoms, but a small percentage develop arrhythmias.

In rare cases, sudden cardiac death can be the presenting feature of WPW syndrome. The estimated risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with the WPW pattern is 1.25 per 1,000 person-years; ventricular fibrillation is the underlying mechanism.6 As our patient had a family history of sudden cardiac death, he was considered at high risk and was therefore referred to an electrophysiologist.

- Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953–1989. Circulation 1993; 87(3):866–873. pmid:8443907

- Carlson AM, Turek JW, Law IH, Von Bergen NH. Pseudo-preexcitation is prevalent among patients with repaired complex congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol.2015; 36(1):8–13. doi:10.1007/s00246-014-0955-x

- Aleong RG, Singh SM, Levinson JR, Milan DJ. Catecholamine challenge unmasking high-risk features in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Europace 2009; 11(10):1396–1398. doi:10.1093/europace/eup211

- Sahu S, Karna ST, Karna A, Lata I, Kapoor D. Anaesthetic management of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome for hysterectomy. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55(4):378–380. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.84866

- Tseng ZH, Yadav AV, Scheinman MM. Catecholamine dependent accessory pathway automaticity. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004; 27(7):1005–1007. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00574.x

- Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012; 125(19):2308–2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350

A 55-year-old man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with left-sided flank pain that had begun 3 days earlier. He described the pain as continuous, sharp, and aggravated by movement. He worked in construction, and before the pain started he had moved 8 sheets of drywall and lifted 5-gallon buckets of spackling compound. He denied any associated chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, cough, or lightheadedness. His family history included sudden cardiac death in 2 second-degree relatives.

On arrival in the emergency department, his vital signs were normal, as were the rest of the findings on physical examination except for reproducible point tenderness below the left scapula.

Laboratory workup revealed normal blood cell counts, liver enzymes, and kidney function. His initial troponin test was negative.

The patient was referred to an electrophysiologist for further evaluation, but he returned to his home country (Haiti) after discharge and was lost to follow-up.

WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE PATTERN VS SYNDROME

WPW syndrome is a disorder of the conduction system leading to preexcitation of the ventricles by an accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles. It is characterized by preexcitation manifested on electrocardiography and by symptomatic arrhythmias.

In contrast, the WPW pattern is defined only by preexcitation findings on electrocardiography without symptomatic arrhythmias. Patients with WPW syndrome can present with palpitation, dizziness, and syncope resulting from underlying arrhythmia.1 This is not seen in patients with the WPW pattern.

A short PR interval with or without delta waves can also be seen in the absence of an accessory pathway, eg, in hypoplastic left heart syndrome, atrioventricular canal defect, and Ebstein anomaly. These conditions are termed pseudopreexcitation syndrome.2

Our patient presented with severe musculoskeletal pain that precipitated the electrocardiographic changes of the WPW pattern and resolved with adequate pain control. The WPW pattern can be unmasked under different scenarios, including anesthesia, sympathomimetic drugs, and postoperatively.3–5

Catecholamine challenge has been used to unmask high-risk features in WPW syndrome.3 Our patient may have had a transient spike in catecholamine levels because of severe musculoskeletal pain, leading to unmasking of accessory pathways and resulting in the WPW pattern on electrocardiography.

Most patients with the WPW pattern experience no symptoms, but a small percentage develop arrhythmias.

In rare cases, sudden cardiac death can be the presenting feature of WPW syndrome. The estimated risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with the WPW pattern is 1.25 per 1,000 person-years; ventricular fibrillation is the underlying mechanism.6 As our patient had a family history of sudden cardiac death, he was considered at high risk and was therefore referred to an electrophysiologist.

A 55-year-old man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with left-sided flank pain that had begun 3 days earlier. He described the pain as continuous, sharp, and aggravated by movement. He worked in construction, and before the pain started he had moved 8 sheets of drywall and lifted 5-gallon buckets of spackling compound. He denied any associated chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, cough, or lightheadedness. His family history included sudden cardiac death in 2 second-degree relatives.

On arrival in the emergency department, his vital signs were normal, as were the rest of the findings on physical examination except for reproducible point tenderness below the left scapula.

Laboratory workup revealed normal blood cell counts, liver enzymes, and kidney function. His initial troponin test was negative.

The patient was referred to an electrophysiologist for further evaluation, but he returned to his home country (Haiti) after discharge and was lost to follow-up.

WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE PATTERN VS SYNDROME

WPW syndrome is a disorder of the conduction system leading to preexcitation of the ventricles by an accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles. It is characterized by preexcitation manifested on electrocardiography and by symptomatic arrhythmias.

In contrast, the WPW pattern is defined only by preexcitation findings on electrocardiography without symptomatic arrhythmias. Patients with WPW syndrome can present with palpitation, dizziness, and syncope resulting from underlying arrhythmia.1 This is not seen in patients with the WPW pattern.

A short PR interval with or without delta waves can also be seen in the absence of an accessory pathway, eg, in hypoplastic left heart syndrome, atrioventricular canal defect, and Ebstein anomaly. These conditions are termed pseudopreexcitation syndrome.2

Our patient presented with severe musculoskeletal pain that precipitated the electrocardiographic changes of the WPW pattern and resolved with adequate pain control. The WPW pattern can be unmasked under different scenarios, including anesthesia, sympathomimetic drugs, and postoperatively.3–5

Catecholamine challenge has been used to unmask high-risk features in WPW syndrome.3 Our patient may have had a transient spike in catecholamine levels because of severe musculoskeletal pain, leading to unmasking of accessory pathways and resulting in the WPW pattern on electrocardiography.

Most patients with the WPW pattern experience no symptoms, but a small percentage develop arrhythmias.

In rare cases, sudden cardiac death can be the presenting feature of WPW syndrome. The estimated risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with the WPW pattern is 1.25 per 1,000 person-years; ventricular fibrillation is the underlying mechanism.6 As our patient had a family history of sudden cardiac death, he was considered at high risk and was therefore referred to an electrophysiologist.

- Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953–1989. Circulation 1993; 87(3):866–873. pmid:8443907

- Carlson AM, Turek JW, Law IH, Von Bergen NH. Pseudo-preexcitation is prevalent among patients with repaired complex congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol.2015; 36(1):8–13. doi:10.1007/s00246-014-0955-x

- Aleong RG, Singh SM, Levinson JR, Milan DJ. Catecholamine challenge unmasking high-risk features in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Europace 2009; 11(10):1396–1398. doi:10.1093/europace/eup211

- Sahu S, Karna ST, Karna A, Lata I, Kapoor D. Anaesthetic management of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome for hysterectomy. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55(4):378–380. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.84866

- Tseng ZH, Yadav AV, Scheinman MM. Catecholamine dependent accessory pathway automaticity. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004; 27(7):1005–1007. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00574.x

- Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012; 125(19):2308–2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350

- Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953–1989. Circulation 1993; 87(3):866–873. pmid:8443907

- Carlson AM, Turek JW, Law IH, Von Bergen NH. Pseudo-preexcitation is prevalent among patients with repaired complex congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol.2015; 36(1):8–13. doi:10.1007/s00246-014-0955-x

- Aleong RG, Singh SM, Levinson JR, Milan DJ. Catecholamine challenge unmasking high-risk features in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Europace 2009; 11(10):1396–1398. doi:10.1093/europace/eup211

- Sahu S, Karna ST, Karna A, Lata I, Kapoor D. Anaesthetic management of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome for hysterectomy. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55(4):378–380. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.84866

- Tseng ZH, Yadav AV, Scheinman MM. Catecholamine dependent accessory pathway automaticity. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004; 27(7):1005–1007. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00574.x

- Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012; 125(19):2308–2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350