User login

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Non-ICU Hospitalization for COVID-19 in a Nonepicenter, Centrally Monitored Healthcare System

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is associated with a wide range of illness severity and community prevalence, with an estimated 20% to 30% of patients requiring hospitalization.1,2 Outcome studies of hospitalized patients to date have focused on epicenter healthcare systems operating at surge-level bed capacity in resource-limited settings with mortality exceeding 20% among patients with a discharge disposition3,4 and have had a publication bias toward those suffering critical illness.5-7 Generalizability of these results to nonepicenter hospital systems is unclear given potential differences in triage practices and resource availability according to disease prevalence, with nonepicenter systems that are operating below capacity potentially able to accommodate the needs of most, if not all patients, requiring inpatient level care. Clinical outcomes associated with non–critically ill patients in nonepicenter regions remain poorly characterized yet highly relevant because these will ultimately apply to most US and global healthcare environments.

Nonepicenter healthcare systems must anticipate disease requirements for noncritically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in order to appropriately allocate resources, including monitoring services like continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Data regarding the incidence of in-hospital respiratory and cardiovascular complications, including arrhythmias, among non–intensive care unit (non-ICU) hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are limited, with little granularity in terms of associated variables.7-11 Further data are needed to guide prioritization of valuable non-ICU continuous monitoring resources to the highest-risk patients in order to minimize consumption of personal protective equipment, reduce healthcare worker exposure, and ensure adequate availability for the expansion of prepandemic services.

Projections indicate that COVID-19 incidence may persist in the coming months.11-13 As nonessential hospital operations simultaneously resume, planning for resource allocation for patients with COVID-19 must be incorporated into broader systems of care. Further data are needed to help hospitals anticipate resource needs during this transition, especially by most systems that are caring for COVID-19 patients in nonepicenter environments. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study of a large, multihospital, nonepicenter health system equipped with centralized continuous monitoring services in order to describe the detailed clinical course, resource utilization, and risk factors for adverse events in patients with COVID-19 initially admitted to the non-ICU setting.

METHODS

Central Monitoring Unit

The central monitoring unit (CMU) provides standardized and continuous off-site secondary monitoring of cardiac telemetry and pulse oximetry for non-ICU patients within Cleveland Clinic hospitals (Ohio, Florida), with direct communication to bedside nursing and inpatient emergency response teams for clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory events, and vital sign changes according to standardized indications, as previously reported.14 Clinical variables of interest, including electrocardiographic and vital sign data, are collected and periodically analyzed within a central registry for quality assurance, risk stratification, and resource allocation. The data registry carries Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective analysis and deidentified outcomes reporting with consent form waiver.

Study Design and Data Collection

All patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction assay (Applied Biosystems) admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU bed at a CMU hospital on or after March 13, 2020, and subsequently discharged on or before May 1, 2020, were identified. Retrospective review of the electronic medical record was performed, with follow-up continued through hospital discharge. Data were collected on patient demographics, clinical characteristics including admission laboratories and chest x-ray findings (abnormal defined as presence of an infiltrate/opacity consistent with airspace disease), continuous monitoring utilization, respiratory support, medication treatment, ICU transfer, and final hospital disposition. In addition, prospective recordings of cardiac arrhythmias that prompted CMU notification of bedside nursing were reviewed.

The primary outcome was a composite of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement defined as escalation from simple nasal cannula to either high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), noninvasive ventilation (NIV) consisting of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or mechanical ventilation. In accordance with published guidelines, patients were treated with supplemental oxygen to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation between 92% and 96%.15

Of note, based on the validated performance of high sensitivity troponin primarily for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, our system reserves its use for this context and prefers conventional (fourth generation) troponin T testing for inpatients. Therefore, conventional troponin T values are reported in this study.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers with percentages. Independent samples t and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate, and chi-square testing was used to compare categorical variables. Clinical variables satisfying an a priori two-tailed threshold of P < .05 were retained for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables retaining P < .05 in multivariable modeling were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, Version 23 (SPSS Inc).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

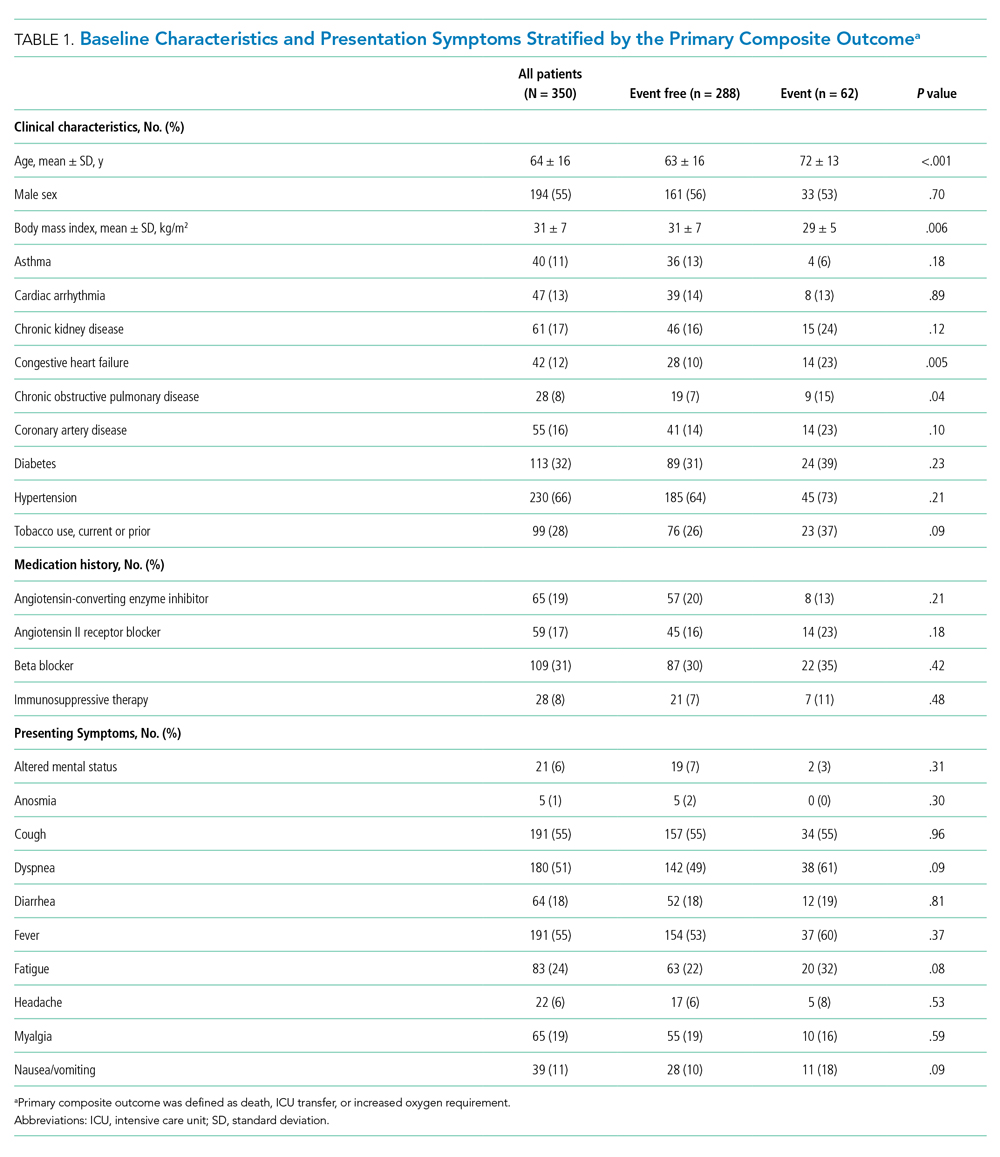

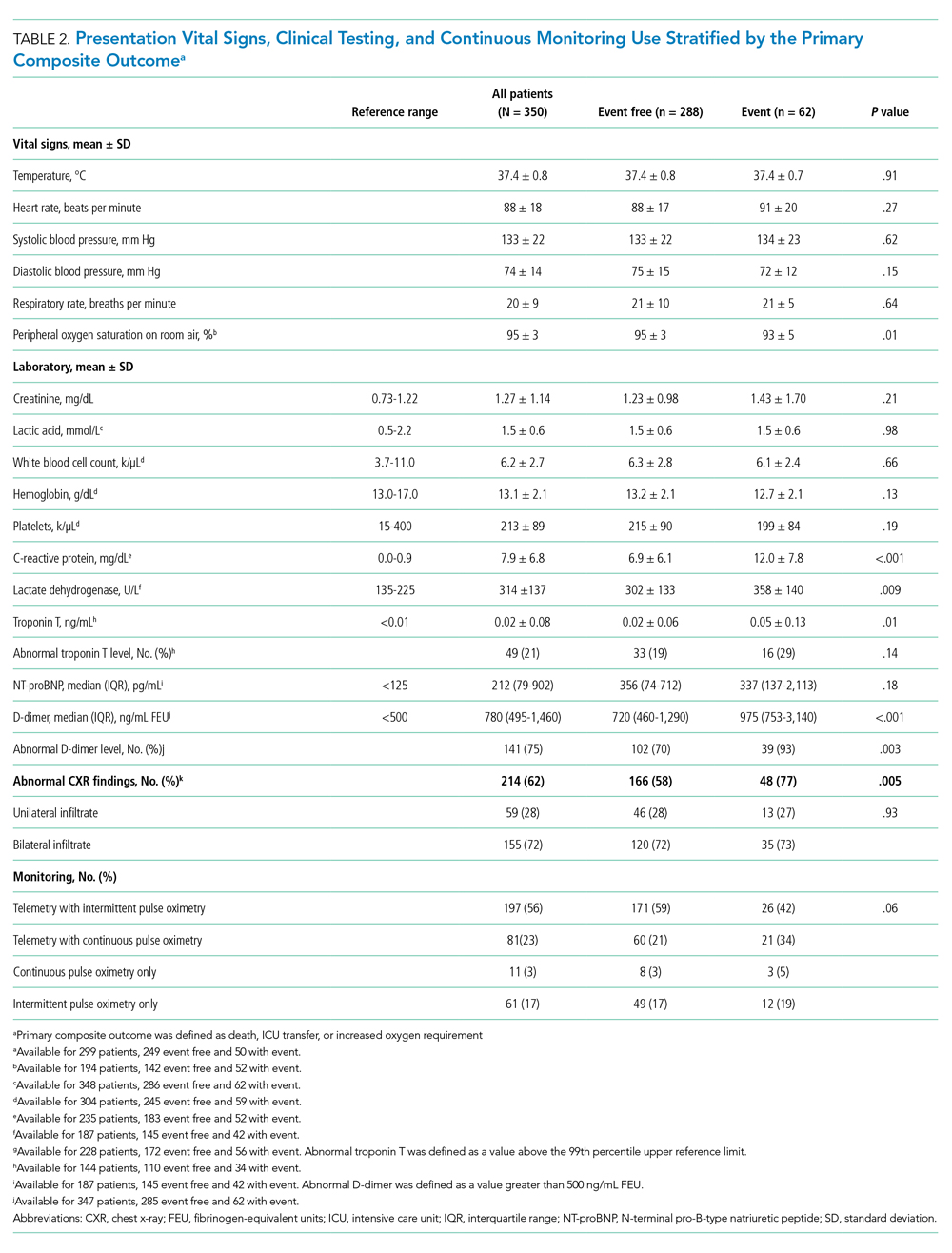

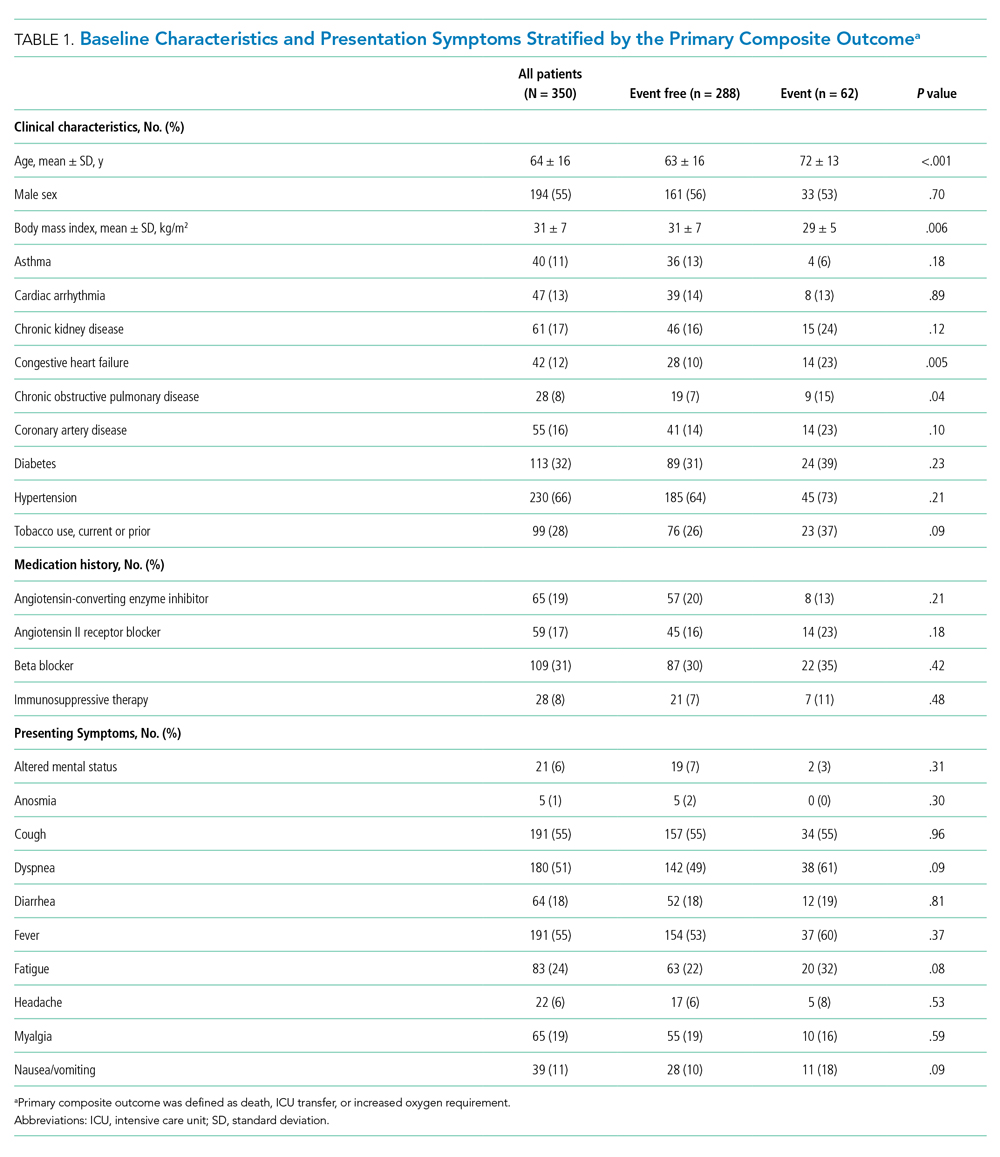

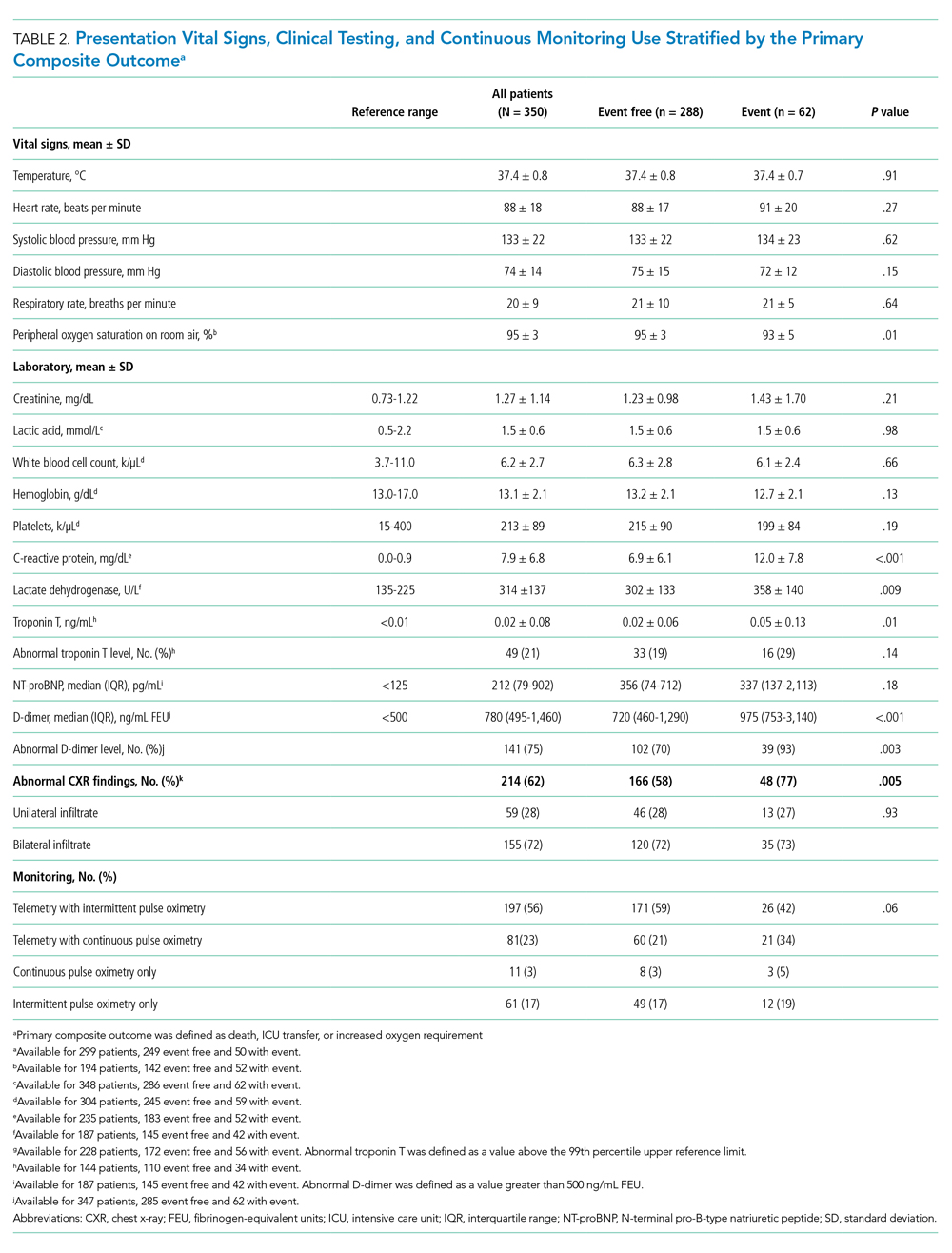

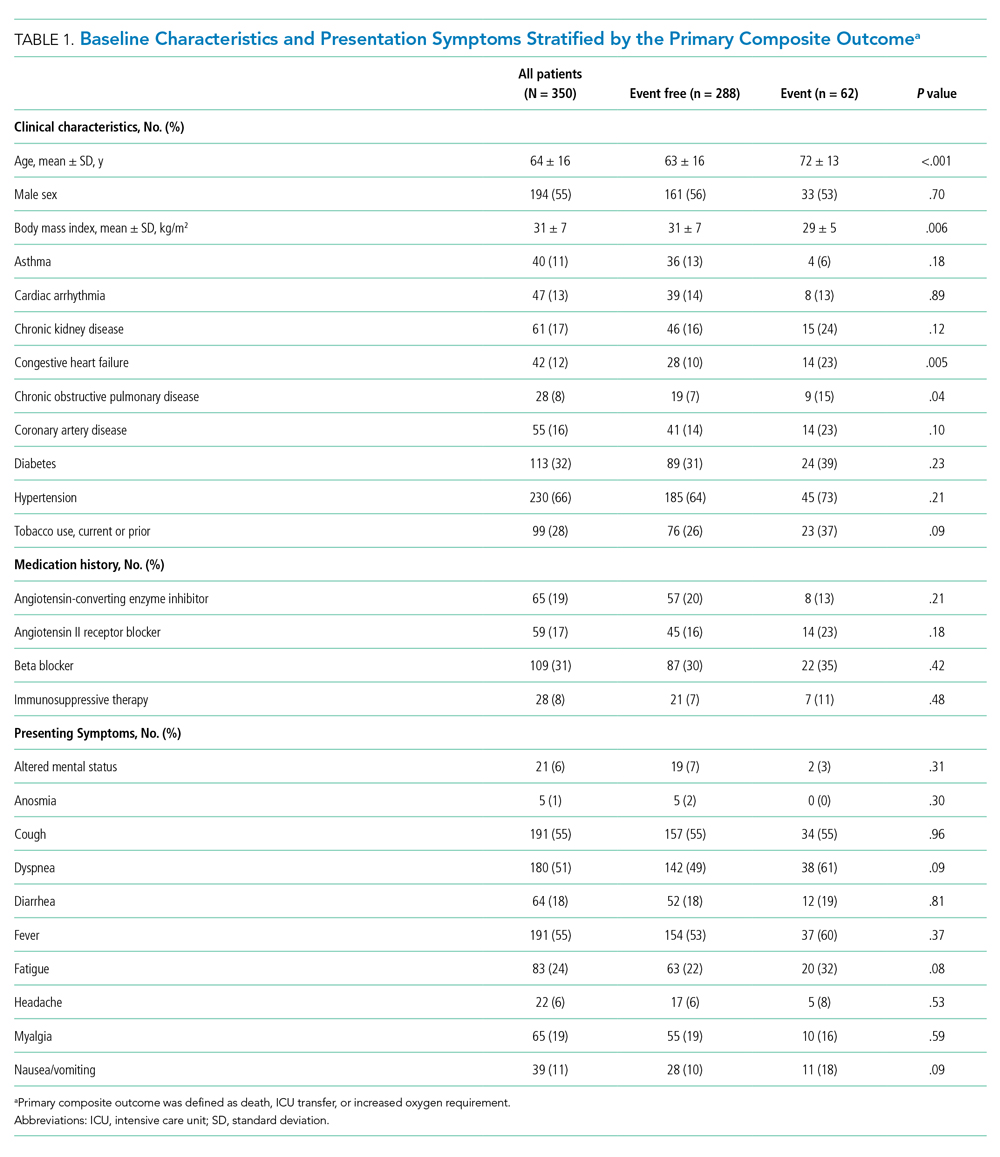

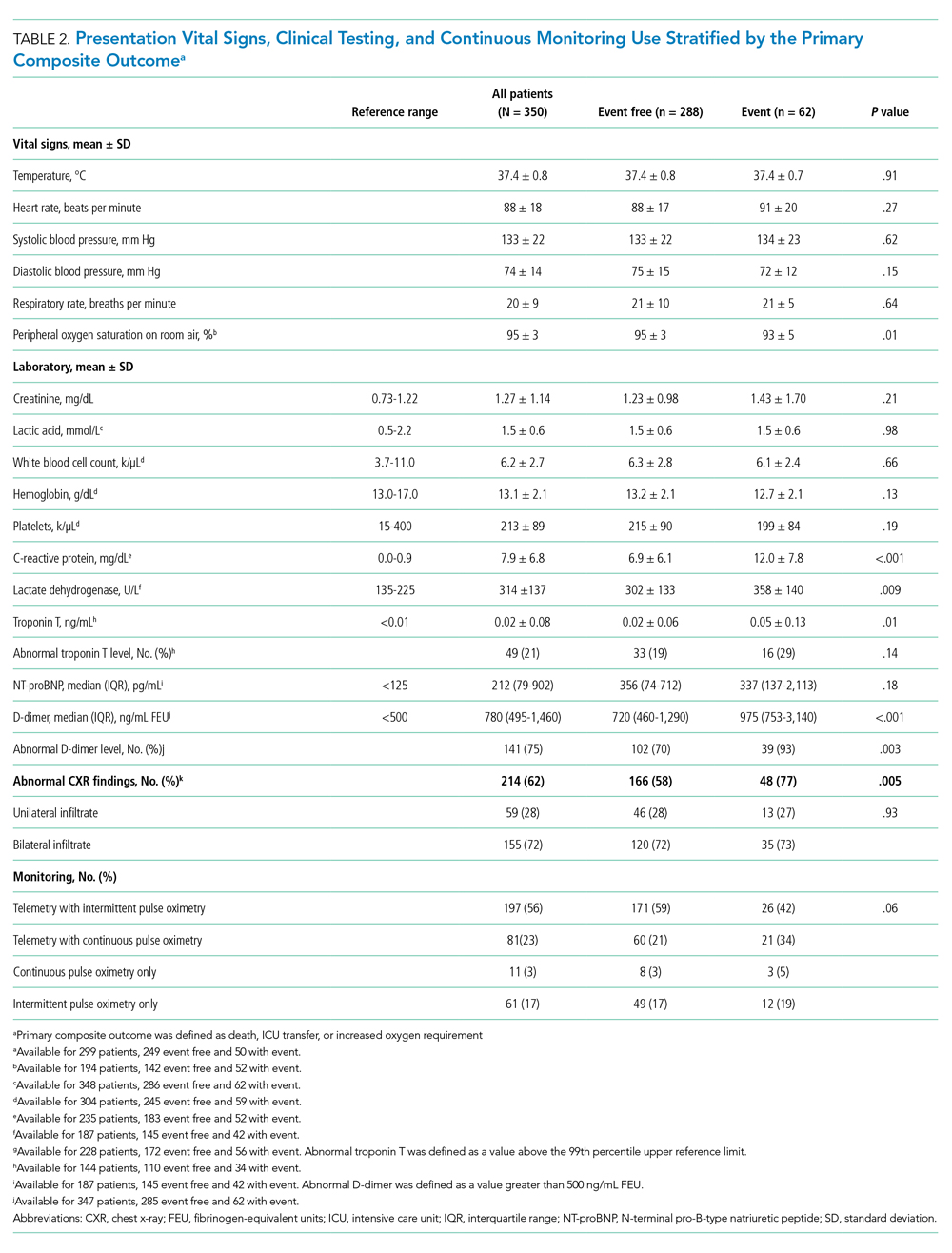

Between March 13, 2020, and May 1, 2020, a total of 350 patients admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU inpatient bed had a final hospital disposition. Baseline characteristics, medication treatments, and continuous monitoring utilization are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The average age was 64 ± 16 years, more than half of patients were male (n = 194; 55%), and most patients had at least one underlying comorbidity (n = 297; 85%), the most common being hypertension (n = 230; 66%), diabetes mellitus (n = 113; 32%), and current or prior tobacco use (n = 99; 28%). The presenting syndrome most frequently included subjective fever (n = 191; 55%), cough (n = 191; 55%), or dyspnea (n = 180; 51%).

Continuous Monitoring Use

Continuous monitoring was used in most patients (n = 289; 83%), including telemetry with intermittent pulse oximetry (n = 197; 56%), telemetry with continuous pulse oximetry (n = 81; 23%), or continuous pulse oximetry alone (n = 11; 3%). Among telemetry-monitored patients (n = 278; 79%), the most frequent indication was for a noncardiac disease state (n = 187; 67%), while indications for known cardiac arrhythmia (n = 74; 27%), heart failure (n = 10; 4%), or coronary artery disease (n = 7; 2%) were less common.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias

The maximum level of respiratory support required by each patient is shown in Appendix Figure 1A. A total of 256 patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 45 (13%) required more than 3 L/min of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 19 (5%) required HFNC, 8 (2%) required NIV, and 22 patients (6%) required mechanical ventilation. Among patients requiring HFNC or NIV, there were 13 (48%) who remained in a non-ICU bed, while the remaining 14 patients (52%) were transferred to the ICU.

Cardiac arrhythmias were detected in 39 (14%) of the 278 telemetry-monitored patients (Appendix Figure 1B). Clinical arrhythmias consisted of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) in 17 patients (6%), nonsustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) in 15 patients (5%), and a prolonged pause or severe bradyarrhythmia in 12 patients (4%). There were no cases of sustained monomorphic VT, polymorphic VT (including torsades de pointes), or ventricular fibrillation. All supraventricular tachycardias, nonsustained monomorphic VTs, and bradyarrhythmias/pauses were managed medically in the non-ICU setting, with the exception of one patient who was transferred to the ICU for a primary indication of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, which was treated with amiodarone. No patient with supraventricular tachycardia required emergent cardioversion, and no patient with a bradyarrhythmia or pause required temporary or permanent pacemaker implantation.

The detection of any arrhythmia was more common in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmia (n = 18/41 vs 21/237; 44% vs 9%; P < .001), congestive heart failure (n = 11/36 vs 28/242; 31% vs 12%; P = .002), coronary artery disease (n = 12/49 vs 27/229; 24% vs 12%; P = .02), hypertension (n = 33/190 vs 6/88; 17% vs 7%; P = .02), and an abnormal admission troponin level (n = 13/40 vs 19/142; 33% vs 13%; P = .005). Notably, of the 39 patients with cardiac arrhythmias, 35 (90%) had either an abnormal admission troponin level or a history of cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or hypertension. Of the 17 patients with SVT episodes, 13 (76%) had a known history of atrial fibrillation. Among patients who had a cardiac arrhythmia vs those who did not, there were no differences in levels of C-reactive protein (CRP; 7.3 ± 6.2 mg/dL vs. 7.8 ± 6.8 mg/dL, P = .63) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; 281 ± 89 U/L vs. 318 ± 142 U/L; P = .17). Approximately half of patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine (n = 185; 53%) or azithromycin (n = 182; 52%); 41% were treated with both (n = 142), with no observed association between any arrhythmia type and treatment with one or both medications (P > .05 for all comparisons).

Discharge Disposition and Adverse Outcomes

After an average length of stay of 6.1 ± 5.9 days, final hospital disposition included discharge to home (n = 278; 79%), discharge to subacute facility (n = 40; 11%), discharge to hospice (n = 8; 2%), death (n = 22, 6%), or release against medical advice (n = 2; 1%) (Figure). The primary composite outcome occurred in 62 patients (18%), including 22 deaths (6%), 48 ICU transfers (14%), and 49 patients with increased oxygen requirements (14%). Only two deaths occurred in the absence of an increased oxygen requirement or ICU transfer.

Increased oxygen requirement was the indication for ICU transfer in 37 of 48 patients (77%), with 22 patients (46%) requiring mechanical ventilation. Of the 48 patients requiring ICU transfer, 14 (29%) died, including 10 of the 22 patients (45%) treated with mechanical ventilation. Of the 302 patients who remained in the non-ICU setting, 8 (3%) died and 8 (3%) were discharged to hospice.

In univariable analyses, the primary composite outcome was more common among older patients (event vs event free, 72 ± 13 years vs 63 ± 16 years; P < .001); it was also more common in patients with congestive heart failure (n = 14/62 vs 28/288; 23% vs 10%; P = .005), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 9/62 vs 19/288; 15% vs 7%; P = .04), lower body mass index (29 ± 5 kg/m2 vs 31 ± 7 kg/m2; P = .006), lower peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (93% ± 5% vs 95% ± 3%; P = .005), higher CRP level (12.0 ± 7.8 mg/dL vs 6.9 ± 6.1 mg/dL; P < .001), higher LDH level (358 ± 140 U/L vs 302 ± 133 U/L; P = .009), higher troponin level (0.05 ± 0.13 ng/dL vs 0.02 ± 0.06 ng/dL; P = .01), abnormal D-dimer level (n = 39/42 vs 102/145; 93% vs 70%; P = .003), and abnormal chest x-ray findings (n = 48/62 vs 166/285; 77% vs 58%; P = .005) (Table 1 and Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, CRP level (odds ratio [OR], 1.09 per 1 mg/dL increase; 95% CI, 1.01-1.18; P = .04) and LDH level (OR, 1.006 per 1 U/L increase; 95% CI, 1.001-1.012; P = .03) remained significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome (Table 3). The rate of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement was sixfold higher in patients with a CRP level in the fourth quartile (≥11.0 mg/dL) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL) (P < .001 for trend), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L) (P = .001 for trend) (Appendix Figure 2). No patient with a CRP level in the reference range (≤ 0.9 mg/dL) experienced the composite adverse event, compared to three patients (n = 3/49, 6.1%) within the reference range for LDH level (≤ 225 U/L), all of whom had an elevated CRP.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 350 patients initially admitted to a non-ICU hospital bed within a large, nonepicenter healthcare system, the primary outcome of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement occurred in 18% of patients and was independently associated with higher admission CRP and LDH levels on multivariable analysis. Most patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen, while 14% of patients required escalation to HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Despite frequent telemetry use (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), including no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer occurred in 14% of patients, most often for an indication of increased oxygen requirement (77%). In-hospital mortality was 6% for the entire cohort, 29% for patients requiring ICU transfer, and 3% for patients who remained in the non-ICU setting.

Nonepicenter, Non-ICU Mortality

This study offers an assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a non-ICU, nonepicenter healthcare system operating below capacity. Although such systems account for most institutions caring for patients with COVID-19, this population has been underrepresented in the literature, which has focused on epicenter hospitals and critically ill patients.3-7 Existing epicenter estimates of in-hospital mortality for patients not requiring ICU-level care range from 6% in Northern California2 to at least 10% in New York, New York,3 and 11% in Wuhan, China.4 The corresponding non-ICU in-hospital mortality in our study was only 3%, supporting the vital role of social distancing in reducing COVID-19 mortality by facilitating care delivery in a non–resource limited hospital setting.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias in Non-ICU Patients

Beyond nonepicenter mortality estimates, this study is the first to provide a detailed characterization of the clinical course and resource usage among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the non-ICU setting. Given the predicted persistence of SARS-CoV-2 spread,11-13 this information is crucial to healthcare systems that must anticipate resource requirements, such as respiratory support and continuous monitoring equipment, for the care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Such informed planning takes on even greater importance as prepandemic hospital services resume.

While most patients (73%) with COVID-19 admitted to a non-ICU bed required peak supplemental oxygen of 3 L/min or less, a relevant proportion (14%) developed a need for HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, among telemetry-monitored patients (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), and nearly all (90%) occurred in patients with either a positive troponin or known history of cardiac disease. There were no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias associated with frequent use of hydroxychloroquine (53%) and azithromycin (52%).

These telemetry findings expand upon a smaller study of non-ICU patients receiving either hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin, in which no life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias were detected.8 A separate study reported a 5.9% incidence of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,10 but this study did not stratify arrhythmias by illness severity, and a high frequency of critical illness is suggested by the mechanical ventilation rate of 24%, thereby limiting comparison with our non-ICU telemetry findings.

CRP and LDH Levels as Predictors of Adverse Outcomes

This study supports the utility of obtaining CRP and LDH levels for risk stratification at the time of non-ICU hospital admission. In multivariable analysis, higher CRP and LDH levels were significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome. The adverse event rates was increased sixfold between patients with a CRP in the fourth quartile (≥ 11.0 mg/dL, 36%) and those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL, 5.3%), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L, 34%) compared with those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L, 7%).

These findings are consistent with prior studies that have associated elevated inflammatory markers with poor prognosis and death.7,9,16 In some cases, COVID-19 may manifest similar to a cytokine storm syndrome, which highlights the importance of inflammation-associated tissue injury and leads to widespread interest in the use of immunosuppressive medications.17,18 Several studies also have demonstrated an association between LDH level and severe illness,4,7,19 although this is the first to specifically demonstrate its association with clinical decompensation in the non-ICU hospitalized population. Given that SARS-CoV-2 can infect multiple organs,20,21 there is biological plausibility for the use of LDH levels as a nonspecific marker of tissue injury for early identification of more severe infection.

Notably, while elevated troponin levels have been strongly associated with the need for mechanical ventilation and with death, this has primarily been established using either high-sensitivity troponin assays at the time of admission22 or using peak conventional troponin levels during hospitalization.10 In this study, while abnormal conventional troponin levels at the time of non-ICU admission were not significantly associated with the primary outcome in multivariable analysis, absolute troponin values were significantly higher in univariable analysis. Incomplete troponin sampling and the lack of routine high-sensitivity troponin assay use may explain the lack of more robust troponin significance in this study.

Implications for Non-ICU Continuous Monitoring Resource Allocation

Prioritization of non-ICU continuous monitoring resources among patients with COVID-19 has numerous benefits, including reduced consumption of personal protective equipment, fewer healthcare worker exposures, and adequate availability of continuous monitoring for the expansion of prepandemic hospital services. While individualized clinical discretion is still required, the results of this study can be used as a guide for the allocation of continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Patients with a normal presenting CRP level and/or LDH level had a low incidence of clinical decompensation, which suggests that such patients could be monitored with intermittent rather than continuous pulse oximetry. Furthermore, cardiac telemetry could be reserved for patients with a history of cardiac comorbidities or abnormal troponin levels because such patients accounted for 90% of cardiac arrhythmias in this study.

Limitations

This study was limited to a single health system, and it lacks a direct comparison to nonhospitalized patients and those directly admitted to the ICU. Triage practices and thresholds for hospitalization may differ across institutions and regions, thereby limiting the generalizability of our study. Additional limitations include the lack of selected admission laboratories for all patients, as well as the lack of telemetry monitoring in all patients. However, any resulting selection bias may be more likely to attenuate the magnitude of observed effects given that additional testing and increased telemetry use may be expected in patients who are felt to be higher risk by routine clinical assessment.

CONCLUSION

In this study of non–critically ill patients hospitalized within a nonepicenter health system, the development of more severe illness or death was significantly associated with higher levels of CRP and LDH on admission. Clinical decompensation was driven largely by respiratory complications, while cardiac arrhythmias were rare. Overall, the non-ICU mortality rate was at least half of that reported in epicenter regions. Altogether, these findings provide valuable information for resource allocation planning while nonepicenter health systems continue caring for patients with COVID-19 as they also resume prepandemic operations.

1. Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, et al; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2

2. Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2195-2198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.7202

3. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. Published online April 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

5. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4326

6. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394

7. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

8. Chang D, Saleh M, Gabriels J, et al. Inpatient use of ambulatory telemetry monitors for COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2992-2993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.032

9. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

10. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Forecasts. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/forecasting-us.html

12. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860-868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793

13. Baker RE, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. Susceptible supply limits the role of climate in the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Science. 2020;369(6501):315-319. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc2535

14. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non-critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10258

15. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004363

16. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

17. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033-1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30628-0

18. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. Published online April 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019

19. Liang W, Liang H, Ou L, et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033

20. Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):590-592. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2011400

21. Zhou J, Li C, Liu X, et al. Infection of bat and human intestinal organoids by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1077-1083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0912-6

22. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802-810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is associated with a wide range of illness severity and community prevalence, with an estimated 20% to 30% of patients requiring hospitalization.1,2 Outcome studies of hospitalized patients to date have focused on epicenter healthcare systems operating at surge-level bed capacity in resource-limited settings with mortality exceeding 20% among patients with a discharge disposition3,4 and have had a publication bias toward those suffering critical illness.5-7 Generalizability of these results to nonepicenter hospital systems is unclear given potential differences in triage practices and resource availability according to disease prevalence, with nonepicenter systems that are operating below capacity potentially able to accommodate the needs of most, if not all patients, requiring inpatient level care. Clinical outcomes associated with non–critically ill patients in nonepicenter regions remain poorly characterized yet highly relevant because these will ultimately apply to most US and global healthcare environments.

Nonepicenter healthcare systems must anticipate disease requirements for noncritically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in order to appropriately allocate resources, including monitoring services like continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Data regarding the incidence of in-hospital respiratory and cardiovascular complications, including arrhythmias, among non–intensive care unit (non-ICU) hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are limited, with little granularity in terms of associated variables.7-11 Further data are needed to guide prioritization of valuable non-ICU continuous monitoring resources to the highest-risk patients in order to minimize consumption of personal protective equipment, reduce healthcare worker exposure, and ensure adequate availability for the expansion of prepandemic services.

Projections indicate that COVID-19 incidence may persist in the coming months.11-13 As nonessential hospital operations simultaneously resume, planning for resource allocation for patients with COVID-19 must be incorporated into broader systems of care. Further data are needed to help hospitals anticipate resource needs during this transition, especially by most systems that are caring for COVID-19 patients in nonepicenter environments. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study of a large, multihospital, nonepicenter health system equipped with centralized continuous monitoring services in order to describe the detailed clinical course, resource utilization, and risk factors for adverse events in patients with COVID-19 initially admitted to the non-ICU setting.

METHODS

Central Monitoring Unit

The central monitoring unit (CMU) provides standardized and continuous off-site secondary monitoring of cardiac telemetry and pulse oximetry for non-ICU patients within Cleveland Clinic hospitals (Ohio, Florida), with direct communication to bedside nursing and inpatient emergency response teams for clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory events, and vital sign changes according to standardized indications, as previously reported.14 Clinical variables of interest, including electrocardiographic and vital sign data, are collected and periodically analyzed within a central registry for quality assurance, risk stratification, and resource allocation. The data registry carries Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective analysis and deidentified outcomes reporting with consent form waiver.

Study Design and Data Collection

All patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction assay (Applied Biosystems) admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU bed at a CMU hospital on or after March 13, 2020, and subsequently discharged on or before May 1, 2020, were identified. Retrospective review of the electronic medical record was performed, with follow-up continued through hospital discharge. Data were collected on patient demographics, clinical characteristics including admission laboratories and chest x-ray findings (abnormal defined as presence of an infiltrate/opacity consistent with airspace disease), continuous monitoring utilization, respiratory support, medication treatment, ICU transfer, and final hospital disposition. In addition, prospective recordings of cardiac arrhythmias that prompted CMU notification of bedside nursing were reviewed.

The primary outcome was a composite of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement defined as escalation from simple nasal cannula to either high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), noninvasive ventilation (NIV) consisting of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or mechanical ventilation. In accordance with published guidelines, patients were treated with supplemental oxygen to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation between 92% and 96%.15

Of note, based on the validated performance of high sensitivity troponin primarily for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, our system reserves its use for this context and prefers conventional (fourth generation) troponin T testing for inpatients. Therefore, conventional troponin T values are reported in this study.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers with percentages. Independent samples t and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate, and chi-square testing was used to compare categorical variables. Clinical variables satisfying an a priori two-tailed threshold of P < .05 were retained for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables retaining P < .05 in multivariable modeling were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, Version 23 (SPSS Inc).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Between March 13, 2020, and May 1, 2020, a total of 350 patients admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU inpatient bed had a final hospital disposition. Baseline characteristics, medication treatments, and continuous monitoring utilization are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The average age was 64 ± 16 years, more than half of patients were male (n = 194; 55%), and most patients had at least one underlying comorbidity (n = 297; 85%), the most common being hypertension (n = 230; 66%), diabetes mellitus (n = 113; 32%), and current or prior tobacco use (n = 99; 28%). The presenting syndrome most frequently included subjective fever (n = 191; 55%), cough (n = 191; 55%), or dyspnea (n = 180; 51%).

Continuous Monitoring Use

Continuous monitoring was used in most patients (n = 289; 83%), including telemetry with intermittent pulse oximetry (n = 197; 56%), telemetry with continuous pulse oximetry (n = 81; 23%), or continuous pulse oximetry alone (n = 11; 3%). Among telemetry-monitored patients (n = 278; 79%), the most frequent indication was for a noncardiac disease state (n = 187; 67%), while indications for known cardiac arrhythmia (n = 74; 27%), heart failure (n = 10; 4%), or coronary artery disease (n = 7; 2%) were less common.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias

The maximum level of respiratory support required by each patient is shown in Appendix Figure 1A. A total of 256 patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 45 (13%) required more than 3 L/min of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 19 (5%) required HFNC, 8 (2%) required NIV, and 22 patients (6%) required mechanical ventilation. Among patients requiring HFNC or NIV, there were 13 (48%) who remained in a non-ICU bed, while the remaining 14 patients (52%) were transferred to the ICU.

Cardiac arrhythmias were detected in 39 (14%) of the 278 telemetry-monitored patients (Appendix Figure 1B). Clinical arrhythmias consisted of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) in 17 patients (6%), nonsustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) in 15 patients (5%), and a prolonged pause or severe bradyarrhythmia in 12 patients (4%). There were no cases of sustained monomorphic VT, polymorphic VT (including torsades de pointes), or ventricular fibrillation. All supraventricular tachycardias, nonsustained monomorphic VTs, and bradyarrhythmias/pauses were managed medically in the non-ICU setting, with the exception of one patient who was transferred to the ICU for a primary indication of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, which was treated with amiodarone. No patient with supraventricular tachycardia required emergent cardioversion, and no patient with a bradyarrhythmia or pause required temporary or permanent pacemaker implantation.

The detection of any arrhythmia was more common in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmia (n = 18/41 vs 21/237; 44% vs 9%; P < .001), congestive heart failure (n = 11/36 vs 28/242; 31% vs 12%; P = .002), coronary artery disease (n = 12/49 vs 27/229; 24% vs 12%; P = .02), hypertension (n = 33/190 vs 6/88; 17% vs 7%; P = .02), and an abnormal admission troponin level (n = 13/40 vs 19/142; 33% vs 13%; P = .005). Notably, of the 39 patients with cardiac arrhythmias, 35 (90%) had either an abnormal admission troponin level or a history of cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or hypertension. Of the 17 patients with SVT episodes, 13 (76%) had a known history of atrial fibrillation. Among patients who had a cardiac arrhythmia vs those who did not, there were no differences in levels of C-reactive protein (CRP; 7.3 ± 6.2 mg/dL vs. 7.8 ± 6.8 mg/dL, P = .63) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; 281 ± 89 U/L vs. 318 ± 142 U/L; P = .17). Approximately half of patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine (n = 185; 53%) or azithromycin (n = 182; 52%); 41% were treated with both (n = 142), with no observed association between any arrhythmia type and treatment with one or both medications (P > .05 for all comparisons).

Discharge Disposition and Adverse Outcomes

After an average length of stay of 6.1 ± 5.9 days, final hospital disposition included discharge to home (n = 278; 79%), discharge to subacute facility (n = 40; 11%), discharge to hospice (n = 8; 2%), death (n = 22, 6%), or release against medical advice (n = 2; 1%) (Figure). The primary composite outcome occurred in 62 patients (18%), including 22 deaths (6%), 48 ICU transfers (14%), and 49 patients with increased oxygen requirements (14%). Only two deaths occurred in the absence of an increased oxygen requirement or ICU transfer.

Increased oxygen requirement was the indication for ICU transfer in 37 of 48 patients (77%), with 22 patients (46%) requiring mechanical ventilation. Of the 48 patients requiring ICU transfer, 14 (29%) died, including 10 of the 22 patients (45%) treated with mechanical ventilation. Of the 302 patients who remained in the non-ICU setting, 8 (3%) died and 8 (3%) were discharged to hospice.

In univariable analyses, the primary composite outcome was more common among older patients (event vs event free, 72 ± 13 years vs 63 ± 16 years; P < .001); it was also more common in patients with congestive heart failure (n = 14/62 vs 28/288; 23% vs 10%; P = .005), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 9/62 vs 19/288; 15% vs 7%; P = .04), lower body mass index (29 ± 5 kg/m2 vs 31 ± 7 kg/m2; P = .006), lower peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (93% ± 5% vs 95% ± 3%; P = .005), higher CRP level (12.0 ± 7.8 mg/dL vs 6.9 ± 6.1 mg/dL; P < .001), higher LDH level (358 ± 140 U/L vs 302 ± 133 U/L; P = .009), higher troponin level (0.05 ± 0.13 ng/dL vs 0.02 ± 0.06 ng/dL; P = .01), abnormal D-dimer level (n = 39/42 vs 102/145; 93% vs 70%; P = .003), and abnormal chest x-ray findings (n = 48/62 vs 166/285; 77% vs 58%; P = .005) (Table 1 and Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, CRP level (odds ratio [OR], 1.09 per 1 mg/dL increase; 95% CI, 1.01-1.18; P = .04) and LDH level (OR, 1.006 per 1 U/L increase; 95% CI, 1.001-1.012; P = .03) remained significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome (Table 3). The rate of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement was sixfold higher in patients with a CRP level in the fourth quartile (≥11.0 mg/dL) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL) (P < .001 for trend), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L) (P = .001 for trend) (Appendix Figure 2). No patient with a CRP level in the reference range (≤ 0.9 mg/dL) experienced the composite adverse event, compared to three patients (n = 3/49, 6.1%) within the reference range for LDH level (≤ 225 U/L), all of whom had an elevated CRP.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 350 patients initially admitted to a non-ICU hospital bed within a large, nonepicenter healthcare system, the primary outcome of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement occurred in 18% of patients and was independently associated with higher admission CRP and LDH levels on multivariable analysis. Most patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen, while 14% of patients required escalation to HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Despite frequent telemetry use (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), including no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer occurred in 14% of patients, most often for an indication of increased oxygen requirement (77%). In-hospital mortality was 6% for the entire cohort, 29% for patients requiring ICU transfer, and 3% for patients who remained in the non-ICU setting.

Nonepicenter, Non-ICU Mortality

This study offers an assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a non-ICU, nonepicenter healthcare system operating below capacity. Although such systems account for most institutions caring for patients with COVID-19, this population has been underrepresented in the literature, which has focused on epicenter hospitals and critically ill patients.3-7 Existing epicenter estimates of in-hospital mortality for patients not requiring ICU-level care range from 6% in Northern California2 to at least 10% in New York, New York,3 and 11% in Wuhan, China.4 The corresponding non-ICU in-hospital mortality in our study was only 3%, supporting the vital role of social distancing in reducing COVID-19 mortality by facilitating care delivery in a non–resource limited hospital setting.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias in Non-ICU Patients

Beyond nonepicenter mortality estimates, this study is the first to provide a detailed characterization of the clinical course and resource usage among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the non-ICU setting. Given the predicted persistence of SARS-CoV-2 spread,11-13 this information is crucial to healthcare systems that must anticipate resource requirements, such as respiratory support and continuous monitoring equipment, for the care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Such informed planning takes on even greater importance as prepandemic hospital services resume.

While most patients (73%) with COVID-19 admitted to a non-ICU bed required peak supplemental oxygen of 3 L/min or less, a relevant proportion (14%) developed a need for HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, among telemetry-monitored patients (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), and nearly all (90%) occurred in patients with either a positive troponin or known history of cardiac disease. There were no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias associated with frequent use of hydroxychloroquine (53%) and azithromycin (52%).

These telemetry findings expand upon a smaller study of non-ICU patients receiving either hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin, in which no life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias were detected.8 A separate study reported a 5.9% incidence of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,10 but this study did not stratify arrhythmias by illness severity, and a high frequency of critical illness is suggested by the mechanical ventilation rate of 24%, thereby limiting comparison with our non-ICU telemetry findings.

CRP and LDH Levels as Predictors of Adverse Outcomes

This study supports the utility of obtaining CRP and LDH levels for risk stratification at the time of non-ICU hospital admission. In multivariable analysis, higher CRP and LDH levels were significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome. The adverse event rates was increased sixfold between patients with a CRP in the fourth quartile (≥ 11.0 mg/dL, 36%) and those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL, 5.3%), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L, 34%) compared with those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L, 7%).

These findings are consistent with prior studies that have associated elevated inflammatory markers with poor prognosis and death.7,9,16 In some cases, COVID-19 may manifest similar to a cytokine storm syndrome, which highlights the importance of inflammation-associated tissue injury and leads to widespread interest in the use of immunosuppressive medications.17,18 Several studies also have demonstrated an association between LDH level and severe illness,4,7,19 although this is the first to specifically demonstrate its association with clinical decompensation in the non-ICU hospitalized population. Given that SARS-CoV-2 can infect multiple organs,20,21 there is biological plausibility for the use of LDH levels as a nonspecific marker of tissue injury for early identification of more severe infection.

Notably, while elevated troponin levels have been strongly associated with the need for mechanical ventilation and with death, this has primarily been established using either high-sensitivity troponin assays at the time of admission22 or using peak conventional troponin levels during hospitalization.10 In this study, while abnormal conventional troponin levels at the time of non-ICU admission were not significantly associated with the primary outcome in multivariable analysis, absolute troponin values were significantly higher in univariable analysis. Incomplete troponin sampling and the lack of routine high-sensitivity troponin assay use may explain the lack of more robust troponin significance in this study.

Implications for Non-ICU Continuous Monitoring Resource Allocation

Prioritization of non-ICU continuous monitoring resources among patients with COVID-19 has numerous benefits, including reduced consumption of personal protective equipment, fewer healthcare worker exposures, and adequate availability of continuous monitoring for the expansion of prepandemic hospital services. While individualized clinical discretion is still required, the results of this study can be used as a guide for the allocation of continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Patients with a normal presenting CRP level and/or LDH level had a low incidence of clinical decompensation, which suggests that such patients could be monitored with intermittent rather than continuous pulse oximetry. Furthermore, cardiac telemetry could be reserved for patients with a history of cardiac comorbidities or abnormal troponin levels because such patients accounted for 90% of cardiac arrhythmias in this study.

Limitations

This study was limited to a single health system, and it lacks a direct comparison to nonhospitalized patients and those directly admitted to the ICU. Triage practices and thresholds for hospitalization may differ across institutions and regions, thereby limiting the generalizability of our study. Additional limitations include the lack of selected admission laboratories for all patients, as well as the lack of telemetry monitoring in all patients. However, any resulting selection bias may be more likely to attenuate the magnitude of observed effects given that additional testing and increased telemetry use may be expected in patients who are felt to be higher risk by routine clinical assessment.

CONCLUSION

In this study of non–critically ill patients hospitalized within a nonepicenter health system, the development of more severe illness or death was significantly associated with higher levels of CRP and LDH on admission. Clinical decompensation was driven largely by respiratory complications, while cardiac arrhythmias were rare. Overall, the non-ICU mortality rate was at least half of that reported in epicenter regions. Altogether, these findings provide valuable information for resource allocation planning while nonepicenter health systems continue caring for patients with COVID-19 as they also resume prepandemic operations.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is associated with a wide range of illness severity and community prevalence, with an estimated 20% to 30% of patients requiring hospitalization.1,2 Outcome studies of hospitalized patients to date have focused on epicenter healthcare systems operating at surge-level bed capacity in resource-limited settings with mortality exceeding 20% among patients with a discharge disposition3,4 and have had a publication bias toward those suffering critical illness.5-7 Generalizability of these results to nonepicenter hospital systems is unclear given potential differences in triage practices and resource availability according to disease prevalence, with nonepicenter systems that are operating below capacity potentially able to accommodate the needs of most, if not all patients, requiring inpatient level care. Clinical outcomes associated with non–critically ill patients in nonepicenter regions remain poorly characterized yet highly relevant because these will ultimately apply to most US and global healthcare environments.

Nonepicenter healthcare systems must anticipate disease requirements for noncritically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in order to appropriately allocate resources, including monitoring services like continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Data regarding the incidence of in-hospital respiratory and cardiovascular complications, including arrhythmias, among non–intensive care unit (non-ICU) hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are limited, with little granularity in terms of associated variables.7-11 Further data are needed to guide prioritization of valuable non-ICU continuous monitoring resources to the highest-risk patients in order to minimize consumption of personal protective equipment, reduce healthcare worker exposure, and ensure adequate availability for the expansion of prepandemic services.

Projections indicate that COVID-19 incidence may persist in the coming months.11-13 As nonessential hospital operations simultaneously resume, planning for resource allocation for patients with COVID-19 must be incorporated into broader systems of care. Further data are needed to help hospitals anticipate resource needs during this transition, especially by most systems that are caring for COVID-19 patients in nonepicenter environments. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study of a large, multihospital, nonepicenter health system equipped with centralized continuous monitoring services in order to describe the detailed clinical course, resource utilization, and risk factors for adverse events in patients with COVID-19 initially admitted to the non-ICU setting.

METHODS

Central Monitoring Unit

The central monitoring unit (CMU) provides standardized and continuous off-site secondary monitoring of cardiac telemetry and pulse oximetry for non-ICU patients within Cleveland Clinic hospitals (Ohio, Florida), with direct communication to bedside nursing and inpatient emergency response teams for clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory events, and vital sign changes according to standardized indications, as previously reported.14 Clinical variables of interest, including electrocardiographic and vital sign data, are collected and periodically analyzed within a central registry for quality assurance, risk stratification, and resource allocation. The data registry carries Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective analysis and deidentified outcomes reporting with consent form waiver.

Study Design and Data Collection

All patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction assay (Applied Biosystems) admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU bed at a CMU hospital on or after March 13, 2020, and subsequently discharged on or before May 1, 2020, were identified. Retrospective review of the electronic medical record was performed, with follow-up continued through hospital discharge. Data were collected on patient demographics, clinical characteristics including admission laboratories and chest x-ray findings (abnormal defined as presence of an infiltrate/opacity consistent with airspace disease), continuous monitoring utilization, respiratory support, medication treatment, ICU transfer, and final hospital disposition. In addition, prospective recordings of cardiac arrhythmias that prompted CMU notification of bedside nursing were reviewed.

The primary outcome was a composite of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement defined as escalation from simple nasal cannula to either high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), noninvasive ventilation (NIV) consisting of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or mechanical ventilation. In accordance with published guidelines, patients were treated with supplemental oxygen to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation between 92% and 96%.15

Of note, based on the validated performance of high sensitivity troponin primarily for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, our system reserves its use for this context and prefers conventional (fourth generation) troponin T testing for inpatients. Therefore, conventional troponin T values are reported in this study.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers with percentages. Independent samples t and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate, and chi-square testing was used to compare categorical variables. Clinical variables satisfying an a priori two-tailed threshold of P < .05 were retained for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables retaining P < .05 in multivariable modeling were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, Version 23 (SPSS Inc).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Between March 13, 2020, and May 1, 2020, a total of 350 patients admitted from the emergency department to a non-ICU inpatient bed had a final hospital disposition. Baseline characteristics, medication treatments, and continuous monitoring utilization are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The average age was 64 ± 16 years, more than half of patients were male (n = 194; 55%), and most patients had at least one underlying comorbidity (n = 297; 85%), the most common being hypertension (n = 230; 66%), diabetes mellitus (n = 113; 32%), and current or prior tobacco use (n = 99; 28%). The presenting syndrome most frequently included subjective fever (n = 191; 55%), cough (n = 191; 55%), or dyspnea (n = 180; 51%).

Continuous Monitoring Use

Continuous monitoring was used in most patients (n = 289; 83%), including telemetry with intermittent pulse oximetry (n = 197; 56%), telemetry with continuous pulse oximetry (n = 81; 23%), or continuous pulse oximetry alone (n = 11; 3%). Among telemetry-monitored patients (n = 278; 79%), the most frequent indication was for a noncardiac disease state (n = 187; 67%), while indications for known cardiac arrhythmia (n = 74; 27%), heart failure (n = 10; 4%), or coronary artery disease (n = 7; 2%) were less common.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias

The maximum level of respiratory support required by each patient is shown in Appendix Figure 1A. A total of 256 patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 45 (13%) required more than 3 L/min of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, 19 (5%) required HFNC, 8 (2%) required NIV, and 22 patients (6%) required mechanical ventilation. Among patients requiring HFNC or NIV, there were 13 (48%) who remained in a non-ICU bed, while the remaining 14 patients (52%) were transferred to the ICU.

Cardiac arrhythmias were detected in 39 (14%) of the 278 telemetry-monitored patients (Appendix Figure 1B). Clinical arrhythmias consisted of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) in 17 patients (6%), nonsustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) in 15 patients (5%), and a prolonged pause or severe bradyarrhythmia in 12 patients (4%). There were no cases of sustained monomorphic VT, polymorphic VT (including torsades de pointes), or ventricular fibrillation. All supraventricular tachycardias, nonsustained monomorphic VTs, and bradyarrhythmias/pauses were managed medically in the non-ICU setting, with the exception of one patient who was transferred to the ICU for a primary indication of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, which was treated with amiodarone. No patient with supraventricular tachycardia required emergent cardioversion, and no patient with a bradyarrhythmia or pause required temporary or permanent pacemaker implantation.

The detection of any arrhythmia was more common in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmia (n = 18/41 vs 21/237; 44% vs 9%; P < .001), congestive heart failure (n = 11/36 vs 28/242; 31% vs 12%; P = .002), coronary artery disease (n = 12/49 vs 27/229; 24% vs 12%; P = .02), hypertension (n = 33/190 vs 6/88; 17% vs 7%; P = .02), and an abnormal admission troponin level (n = 13/40 vs 19/142; 33% vs 13%; P = .005). Notably, of the 39 patients with cardiac arrhythmias, 35 (90%) had either an abnormal admission troponin level or a history of cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or hypertension. Of the 17 patients with SVT episodes, 13 (76%) had a known history of atrial fibrillation. Among patients who had a cardiac arrhythmia vs those who did not, there were no differences in levels of C-reactive protein (CRP; 7.3 ± 6.2 mg/dL vs. 7.8 ± 6.8 mg/dL, P = .63) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; 281 ± 89 U/L vs. 318 ± 142 U/L; P = .17). Approximately half of patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine (n = 185; 53%) or azithromycin (n = 182; 52%); 41% were treated with both (n = 142), with no observed association between any arrhythmia type and treatment with one or both medications (P > .05 for all comparisons).

Discharge Disposition and Adverse Outcomes

After an average length of stay of 6.1 ± 5.9 days, final hospital disposition included discharge to home (n = 278; 79%), discharge to subacute facility (n = 40; 11%), discharge to hospice (n = 8; 2%), death (n = 22, 6%), or release against medical advice (n = 2; 1%) (Figure). The primary composite outcome occurred in 62 patients (18%), including 22 deaths (6%), 48 ICU transfers (14%), and 49 patients with increased oxygen requirements (14%). Only two deaths occurred in the absence of an increased oxygen requirement or ICU transfer.

Increased oxygen requirement was the indication for ICU transfer in 37 of 48 patients (77%), with 22 patients (46%) requiring mechanical ventilation. Of the 48 patients requiring ICU transfer, 14 (29%) died, including 10 of the 22 patients (45%) treated with mechanical ventilation. Of the 302 patients who remained in the non-ICU setting, 8 (3%) died and 8 (3%) were discharged to hospice.

In univariable analyses, the primary composite outcome was more common among older patients (event vs event free, 72 ± 13 years vs 63 ± 16 years; P < .001); it was also more common in patients with congestive heart failure (n = 14/62 vs 28/288; 23% vs 10%; P = .005), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 9/62 vs 19/288; 15% vs 7%; P = .04), lower body mass index (29 ± 5 kg/m2 vs 31 ± 7 kg/m2; P = .006), lower peripheral oxygen saturation on room air (93% ± 5% vs 95% ± 3%; P = .005), higher CRP level (12.0 ± 7.8 mg/dL vs 6.9 ± 6.1 mg/dL; P < .001), higher LDH level (358 ± 140 U/L vs 302 ± 133 U/L; P = .009), higher troponin level (0.05 ± 0.13 ng/dL vs 0.02 ± 0.06 ng/dL; P = .01), abnormal D-dimer level (n = 39/42 vs 102/145; 93% vs 70%; P = .003), and abnormal chest x-ray findings (n = 48/62 vs 166/285; 77% vs 58%; P = .005) (Table 1 and Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, CRP level (odds ratio [OR], 1.09 per 1 mg/dL increase; 95% CI, 1.01-1.18; P = .04) and LDH level (OR, 1.006 per 1 U/L increase; 95% CI, 1.001-1.012; P = .03) remained significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome (Table 3). The rate of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement was sixfold higher in patients with a CRP level in the fourth quartile (≥11.0 mg/dL) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL) (P < .001 for trend), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L) than it was among those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L) (P = .001 for trend) (Appendix Figure 2). No patient with a CRP level in the reference range (≤ 0.9 mg/dL) experienced the composite adverse event, compared to three patients (n = 3/49, 6.1%) within the reference range for LDH level (≤ 225 U/L), all of whom had an elevated CRP.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 350 patients initially admitted to a non-ICU hospital bed within a large, nonepicenter healthcare system, the primary outcome of death, ICU transfer, or increased oxygen requirement occurred in 18% of patients and was independently associated with higher admission CRP and LDH levels on multivariable analysis. Most patients (73%) required 3 L/min or less of supplemental oxygen, while 14% of patients required escalation to HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Despite frequent telemetry use (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), including no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer occurred in 14% of patients, most often for an indication of increased oxygen requirement (77%). In-hospital mortality was 6% for the entire cohort, 29% for patients requiring ICU transfer, and 3% for patients who remained in the non-ICU setting.

Nonepicenter, Non-ICU Mortality

This study offers an assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a non-ICU, nonepicenter healthcare system operating below capacity. Although such systems account for most institutions caring for patients with COVID-19, this population has been underrepresented in the literature, which has focused on epicenter hospitals and critically ill patients.3-7 Existing epicenter estimates of in-hospital mortality for patients not requiring ICU-level care range from 6% in Northern California2 to at least 10% in New York, New York,3 and 11% in Wuhan, China.4 The corresponding non-ICU in-hospital mortality in our study was only 3%, supporting the vital role of social distancing in reducing COVID-19 mortality by facilitating care delivery in a non–resource limited hospital setting.

Oxygen Requirements and Cardiac Arrhythmias in Non-ICU Patients

Beyond nonepicenter mortality estimates, this study is the first to provide a detailed characterization of the clinical course and resource usage among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the non-ICU setting. Given the predicted persistence of SARS-CoV-2 spread,11-13 this information is crucial to healthcare systems that must anticipate resource requirements, such as respiratory support and continuous monitoring equipment, for the care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Such informed planning takes on even greater importance as prepandemic hospital services resume.

While most patients (73%) with COVID-19 admitted to a non-ICU bed required peak supplemental oxygen of 3 L/min or less, a relevant proportion (14%) developed a need for HFNC, NIV, or mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, among telemetry-monitored patients (79%), cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (14%), and nearly all (90%) occurred in patients with either a positive troponin or known history of cardiac disease. There were no life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias associated with frequent use of hydroxychloroquine (53%) and azithromycin (52%).

These telemetry findings expand upon a smaller study of non-ICU patients receiving either hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin, in which no life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias were detected.8 A separate study reported a 5.9% incidence of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,10 but this study did not stratify arrhythmias by illness severity, and a high frequency of critical illness is suggested by the mechanical ventilation rate of 24%, thereby limiting comparison with our non-ICU telemetry findings.

CRP and LDH Levels as Predictors of Adverse Outcomes

This study supports the utility of obtaining CRP and LDH levels for risk stratification at the time of non-ICU hospital admission. In multivariable analysis, higher CRP and LDH levels were significantly associated with the composite adverse outcome. The adverse event rates was increased sixfold between patients with a CRP in the fourth quartile (≥ 11.0 mg/dL, 36%) and those in the first quartile (≤ 2.6 mg/dL, 5.3%), and it was fivefold higher in patients with an LDH level in the fourth quartile (≥ 354 U/L, 34%) compared with those in the first quartile (≤ 232 U/L, 7%).

These findings are consistent with prior studies that have associated elevated inflammatory markers with poor prognosis and death.7,9,16 In some cases, COVID-19 may manifest similar to a cytokine storm syndrome, which highlights the importance of inflammation-associated tissue injury and leads to widespread interest in the use of immunosuppressive medications.17,18 Several studies also have demonstrated an association between LDH level and severe illness,4,7,19 although this is the first to specifically demonstrate its association with clinical decompensation in the non-ICU hospitalized population. Given that SARS-CoV-2 can infect multiple organs,20,21 there is biological plausibility for the use of LDH levels as a nonspecific marker of tissue injury for early identification of more severe infection.

Notably, while elevated troponin levels have been strongly associated with the need for mechanical ventilation and with death, this has primarily been established using either high-sensitivity troponin assays at the time of admission22 or using peak conventional troponin levels during hospitalization.10 In this study, while abnormal conventional troponin levels at the time of non-ICU admission were not significantly associated with the primary outcome in multivariable analysis, absolute troponin values were significantly higher in univariable analysis. Incomplete troponin sampling and the lack of routine high-sensitivity troponin assay use may explain the lack of more robust troponin significance in this study.

Implications for Non-ICU Continuous Monitoring Resource Allocation

Prioritization of non-ICU continuous monitoring resources among patients with COVID-19 has numerous benefits, including reduced consumption of personal protective equipment, fewer healthcare worker exposures, and adequate availability of continuous monitoring for the expansion of prepandemic hospital services. While individualized clinical discretion is still required, the results of this study can be used as a guide for the allocation of continuous pulse oximetry and cardiac telemetry. Patients with a normal presenting CRP level and/or LDH level had a low incidence of clinical decompensation, which suggests that such patients could be monitored with intermittent rather than continuous pulse oximetry. Furthermore, cardiac telemetry could be reserved for patients with a history of cardiac comorbidities or abnormal troponin levels because such patients accounted for 90% of cardiac arrhythmias in this study.

Limitations

This study was limited to a single health system, and it lacks a direct comparison to nonhospitalized patients and those directly admitted to the ICU. Triage practices and thresholds for hospitalization may differ across institutions and regions, thereby limiting the generalizability of our study. Additional limitations include the lack of selected admission laboratories for all patients, as well as the lack of telemetry monitoring in all patients. However, any resulting selection bias may be more likely to attenuate the magnitude of observed effects given that additional testing and increased telemetry use may be expected in patients who are felt to be higher risk by routine clinical assessment.

CONCLUSION

In this study of non–critically ill patients hospitalized within a nonepicenter health system, the development of more severe illness or death was significantly associated with higher levels of CRP and LDH on admission. Clinical decompensation was driven largely by respiratory complications, while cardiac arrhythmias were rare. Overall, the non-ICU mortality rate was at least half of that reported in epicenter regions. Altogether, these findings provide valuable information for resource allocation planning while nonepicenter health systems continue caring for patients with COVID-19 as they also resume prepandemic operations.

1. Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, et al; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2

2. Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2195-2198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.7202

3. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. Published online April 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

5. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4326

6. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394

7. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

8. Chang D, Saleh M, Gabriels J, et al. Inpatient use of ambulatory telemetry monitors for COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2992-2993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.032

9. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

10. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Forecasts. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/forecasting-us.html

12. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860-868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793

13. Baker RE, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. Susceptible supply limits the role of climate in the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Science. 2020;369(6501):315-319. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc2535

14. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non-critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10258

15. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004363

16. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

17. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033-1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30628-0

18. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. Published online April 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019

19. Liang W, Liang H, Ou L, et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033

20. Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):590-592. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2011400

21. Zhou J, Li C, Liu X, et al. Infection of bat and human intestinal organoids by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1077-1083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0912-6

22. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802-810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950

1. Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, et al; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2

2. Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2195-2198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.7202

3. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. Published online April 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

5. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4326

6. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394

7. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

8. Chang D, Saleh M, Gabriels J, et al. Inpatient use of ambulatory telemetry monitors for COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2992-2993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.032

9. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

10. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Forecasts. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/forecasting-us.html

12. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860-868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793

13. Baker RE, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. Susceptible supply limits the role of climate in the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Science. 2020;369(6501):315-319. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc2535

14. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non-critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10258

15. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004363

16. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

17. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033-1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30628-0

18. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. Published online April 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019

19. Liang W, Liang H, Ou L, et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033

20. Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):590-592. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2011400

21. Zhou J, Li C, Liu X, et al. Infection of bat and human intestinal organoids by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1077-1083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0912-6

22. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802-810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

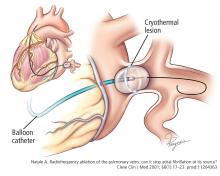

Ablation of atrial fibrillation: Facts for the referring physician

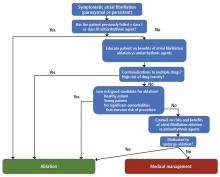

A 64-year-old man with hypertension but without known structural heart disease presents for a second opinion on management of his atrial fibrillation. The condition was first diagnosed at age 38, when he experienced palpitations and shortness of breath on exertion; at times he also experienced decreased endurance and fatigue without overt palpitations. At first, these episodes occurred about twice a year, and the patient was managed with a beta-blocker for rate control and an oral anticoagulant.

Over the past 10 years, the episodes have become more frequent and longer-lasting and have required frequent cardioversions. He was given flecainide for rhythm control but continued to have frequent episodes, and so about 1 year ago he was switched to amiodarone, which controlled his rhythm better. However, after reading about side effects of amiodarone, he decided to seek a second opinion.

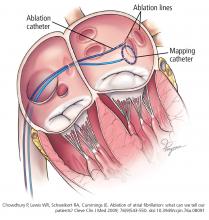

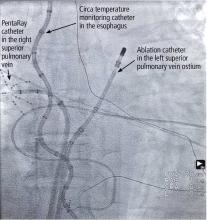

He was evaluated by our team and eventually underwent radiofrequency ablation. During the procedure, he was noted to have diffuse scarring and fibrosis of his left atrium, and afterward he continued to require antiarrhythmic drugs to maintain sinus rhythm.

Should he have been referred sooner? What factors should primary care physicians consider when referring a patient with atrial fibrillation for ablation?

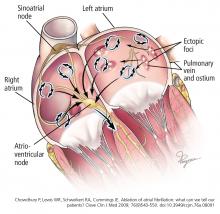

THE EPIDEMIC OF ATRIAL FIBRILLATION