User login

Impact of 3 Months of Supervised Exercise on Function by Arthritis Status

Impact of 3 Months of Supervised Exercise on Function by Arthritis Status

About half of US adults aged ≥ 65 years report arthritis, and of those, 44% have an arthritis-attributable activity limitation.1,2 Arthritis is a significant health issue for veterans, with veterans reporting higher rates of disability compared with the civilian population.3

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis.4 Among individuals aged ≥ 40 years, the incidence of OA is nearly twice as high among veterans compared with civilians and is a leading cause of separation from military service and disability.5,6 OA pain and disability have been shown to be associated with increases in health care and medication use, including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and muscle relaxants.7,8 Because OA is chronic and has no cure, safe and effective management strategies—such as exercise— are critical to minimize pain and maintain physical function.9

Exercise can reduce pain and disability associated with OA and is a first-line recommendation in guidelines for the treatment of knee and hip OA.9 Given the limited exercise and high levels of physical inactivity among veterans with OA, there is a need to identify opportunities that support veterans with OA engaging in regular exercise.

Gerofit, an outpatient clinical exercise program available at 30 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) sites, may provide an opportunity for older veterans with arthritis to engage in exercise.10 Gerofit is specifically designed for veterans aged ≥ 65 years. It is not disease-specific and supports older veterans with multiple chronic conditions, including OA. Veterans aged ≥ 65 years with a referral from a VA clinician are eligible for Gerofit. Those who are unable to perform activities of daily living; unable to independently function without assistance; have a history of unstable angina, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, volatile behavioral issues, or are unable to work successfully in a group environment/setting; experience active substance abuse, homelessness, or uncontrolled incontinence; and have open wounds that cannot be appropriately dressed are excluded from Gerofit. Exercise sessions are held 3 times per week and last from 60 to 90 minutes. Sessions are supervised by Gerofit staff and include personalized exercise prescriptions based on functional assessments. Exercise prescriptions include aerobic, resistance, and balance/flexibility components and are modified by the Gerofit program staff as needed. Gerofit adopts a functional fitness approach and includes individual progression as appropriate according to evidence-based guidelines, using the Borg ratings of perceived exertion. 11 Assessments are performed at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and annually thereafter. Clinical staff conduct all assessments, including physical function testing, and record them in a database. Assessments are reviewed with the veteran to chart progress and identify future goals or needs. Veterans perform personalized self-paced exercises in the Gerofit group setting. Exercise prescriptions are continuously modified to meet individualized needs and goals. Veterans may participate continuously with no end date.

Participation in supervised exercise is associated with improved physical function and individuals with arthritis can improve function even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis. 12 In this analysis, we examine the impact of exercise on the status and location of arthritis (upper body, lower body, or both). Lower body arthritis is more common than upper body arthritis and lower extremity function is associated with increased ability to perform activities of daily living, resulting in independence among older adults.13,14 We also include upper body strength measures to capture important functional movements such as reaching and pulling.15 Among those who participate in Gerofit, the greatest gains in physical function occur during the initial 3 months, which tend to be sustained over 12 months.16 For this reason, this study focused on the initial 3 months of the program.

Older adults with arthritis may have pain and functional limitations that exceed those of the general older adult population. Exercise programs for older adults that do not specifically target arthritis but are able to improve physical function among those with arthritis could potentially increase access to exercise for older adults living with arthritis. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether change in physical function with participation in Gerofit for 3 months varies by arthritis status, including no arthritis, any arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both upper and lower body arthritis compared with no arthritis.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of previously collected data from 10 VHA Gerofit sites (Ann Arbor, Baltimore, Greater Los Angeles, Canandaigua, Cincinnati, Miami, Honolulu, Denver, Durham, and Pittsburgh) from 2002 to 2019. Implementation data regarding the consistency of the program delivery at Gerofit expansion sites have been previously published.16 Although the delivery of Gerofit transitioned to telehealth due to COVID-19, data for this analysis were collected from in-person exercise sessions prior to the pandemic.17 Data were collected for clinical purposes. This project was part of the Gerofit quality improvement initiative and was reviewed and approved by the Durham Institutional Review Board as quality improvement.

Participants in Gerofit who completed baseline and 3-month assessments were included to analyze the effects of exercise on physical function. At each of the time points, physical functional assessments included: (1) usual gait speed (> 10 meters [m/s], or 10- meter walk test [10MWT]); (2) lower body strength (chair stands [number completed in 30 seconds]); (3) upper body strength (number of arm curls [5-lb for females/8-lb for males] completed in 30 seconds); and (4) 6-minute walk distance [6MWD] in meters to measure aerobic endurance). These measures have been validated in older adults.18-21 Arm curls were added to the physical function assessments after the 10MWT, chair stands, and 6MWD; therefore, fewer participants had data for this measure. Participants self-reported at baseline on 45 common medical conditions, including arthritis or rheumatism (both upper body and lower body were offered as choices). Self-reporting has been shown to be an acceptable method of identifying arthritis in adults.22

Descriptive statistics at baseline were calculated for all participants. One-way analysis of variance and X2 tests were used to determine differences in baseline characteristics across arthritis status. The primary outcomes were changes in physical function measures from baseline to 3 months by arthritis status. Arthritis status was defined as: any arthritis, which includes individuals who reported upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both; and arthritis status individuals reporting either upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both. Categories of arthritis for arthritis status were mutually exclusive. Two separate linear models were constructed for each of the 4 physical function measures, with change from baseline to 3 months as the outcome (dependent variable) and arthritis status, age, and body mass index (BMI) as predictors (independent variables). The first model compared any arthritis with no arthritis and the second model compared arthritis status (both upper and lower body arthritis vs lower body arthritis) with no arthritis. These models were used to obtain mean changes and 95% CIs in physical function and to test for differences in the change in physical function measures by arthritis status. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.0.3.

Results

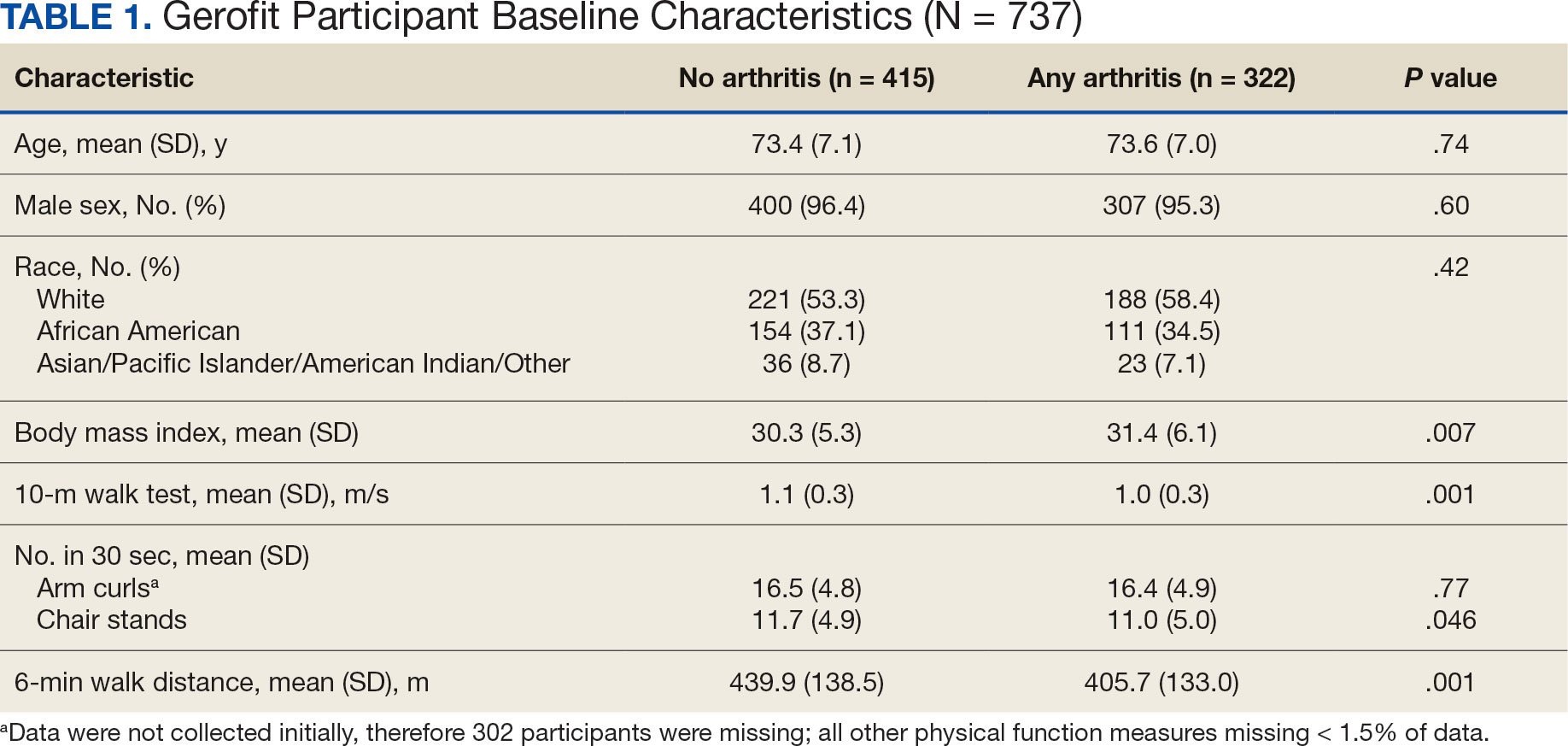

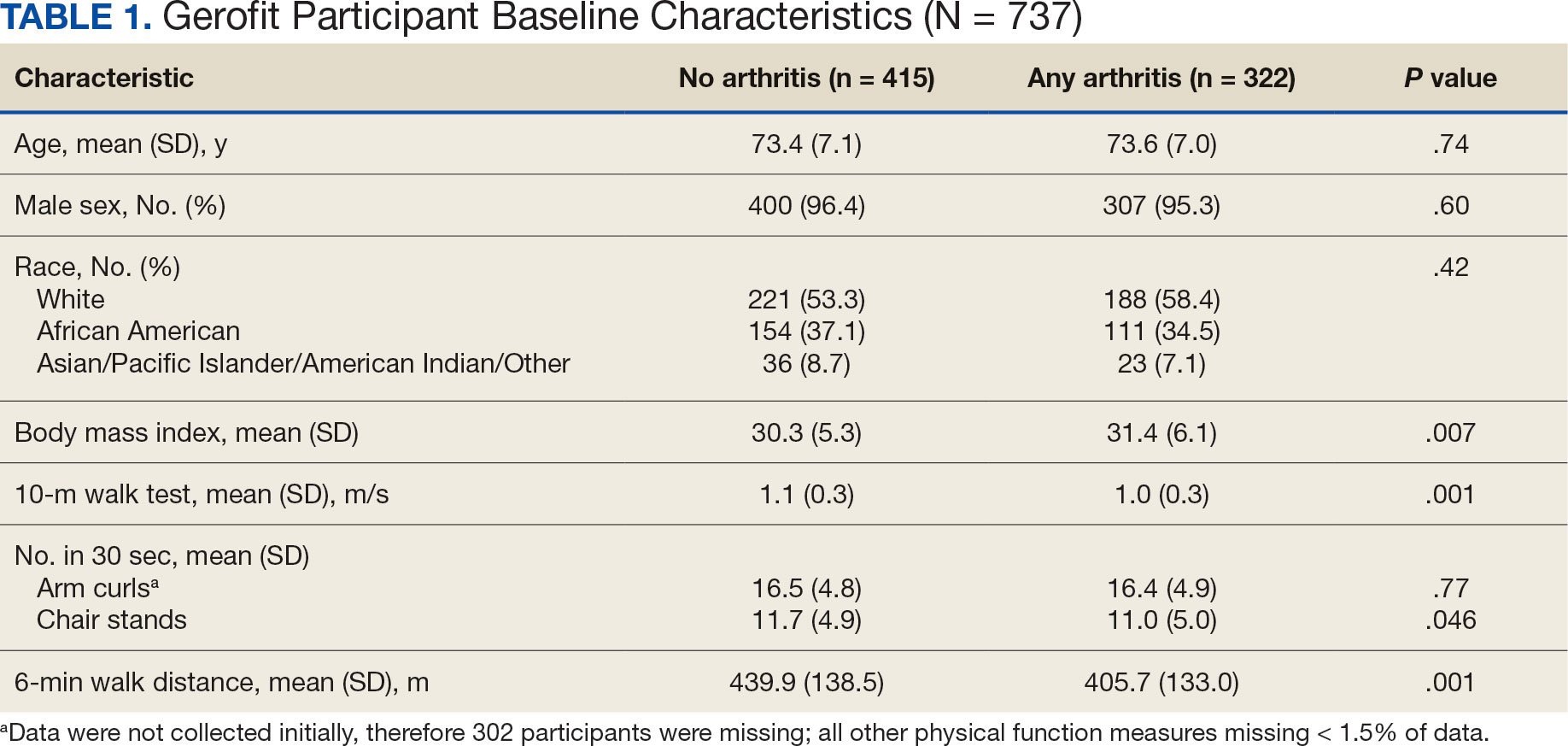

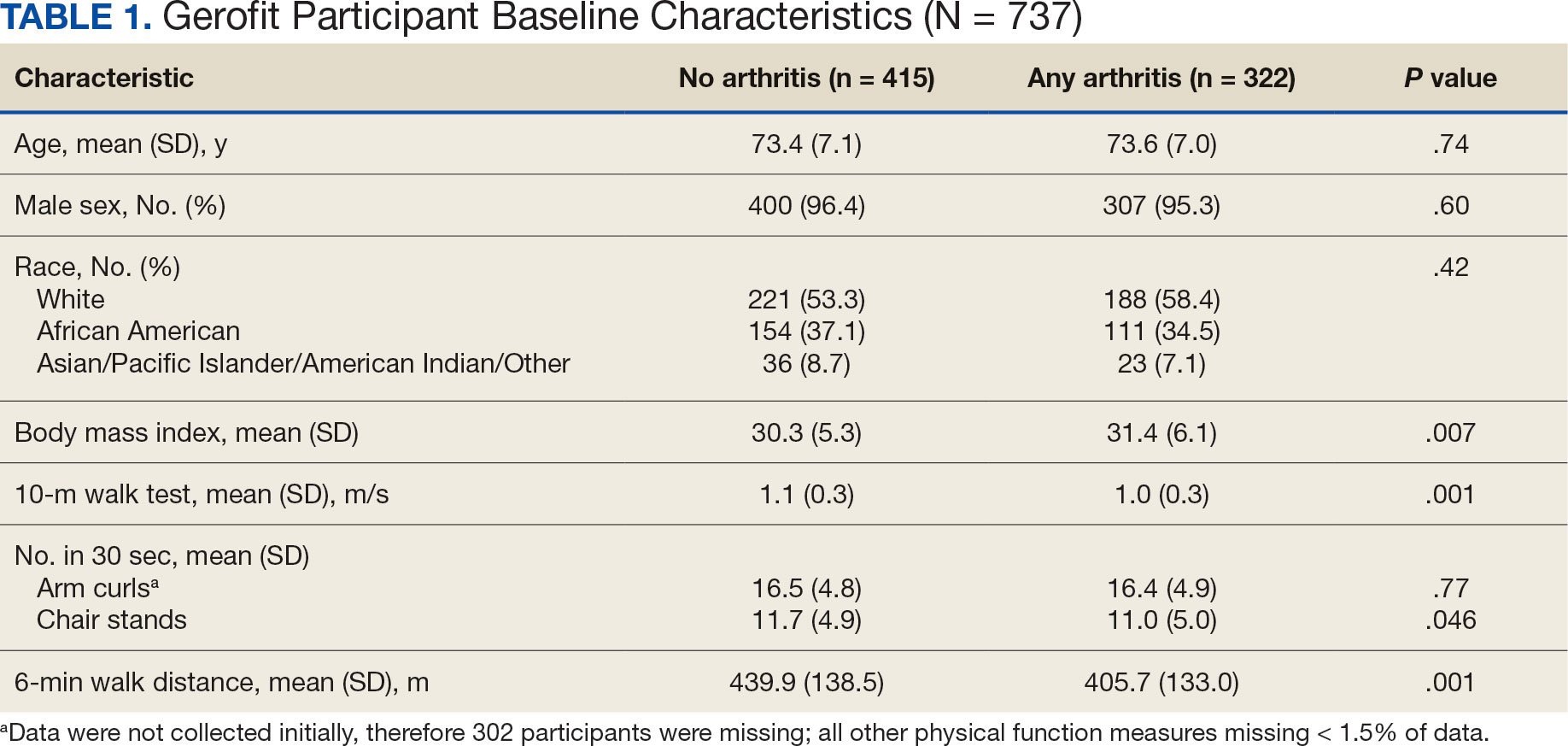

Baseline and 3-month data were available for 737 Gerofit participants and included in the analysis. The mean (SD) age was 73.5 (7.1) years. A total of 707 participants were male (95.9%) and 322 (43.6%) reported some arthritis, with arthritis in both the upper and lower body being reported by 168 participants (52.2%) (Table 1). There were no differences in age, sex, or race for those with any arthritis compared with those with no arthritis, but BMI was significantly higher in those reporting any arthritis compared with no arthritis. For the baseline functional measures, statistically significant differences were observed between those with no arthritis and those reporting any arthritis for the 10MWT (P = .001), chair stands (P = .046), and 6MWD (P = .001), but not for arm curls (P = .77), with those with no arthritis performing better.

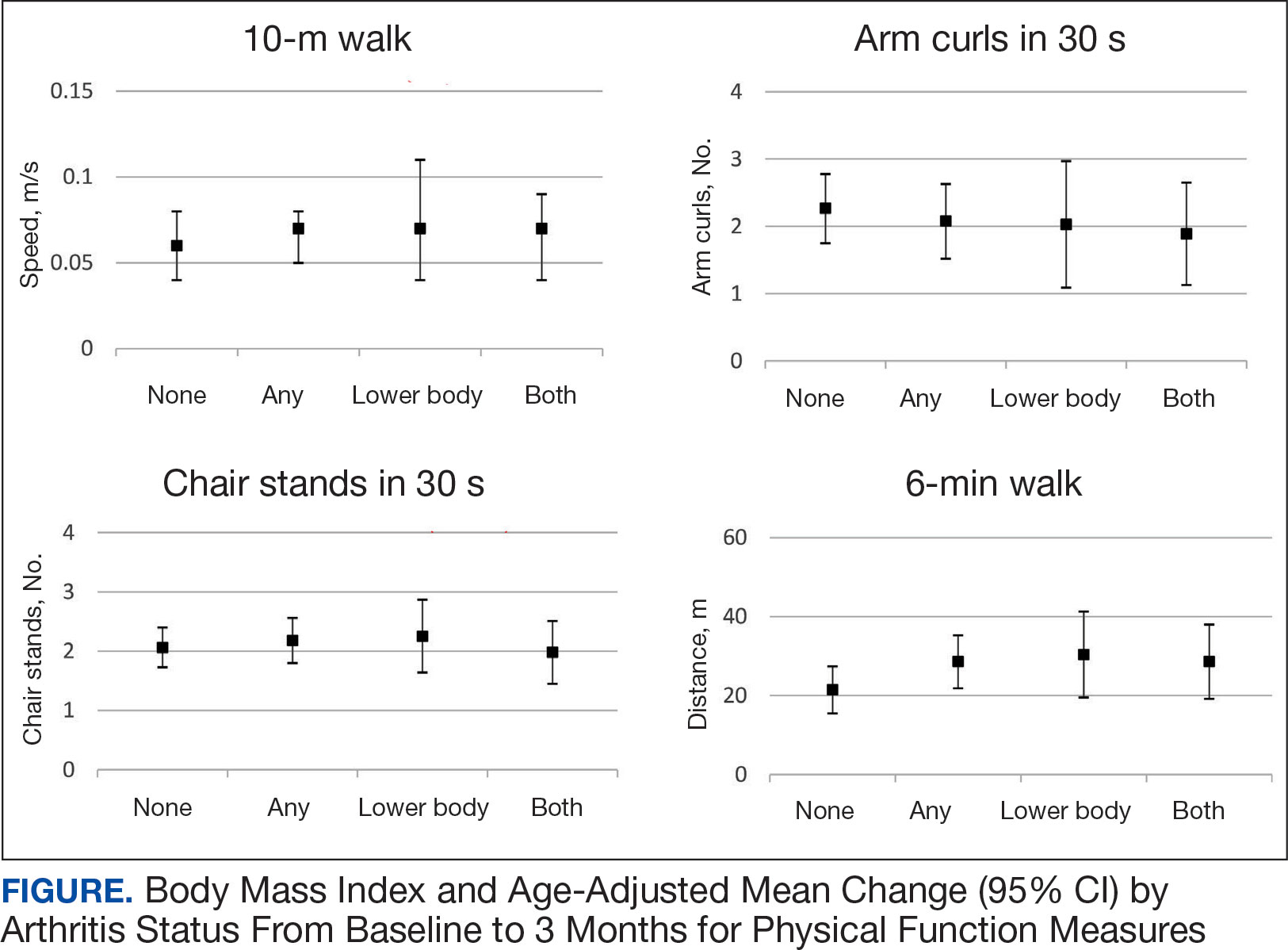

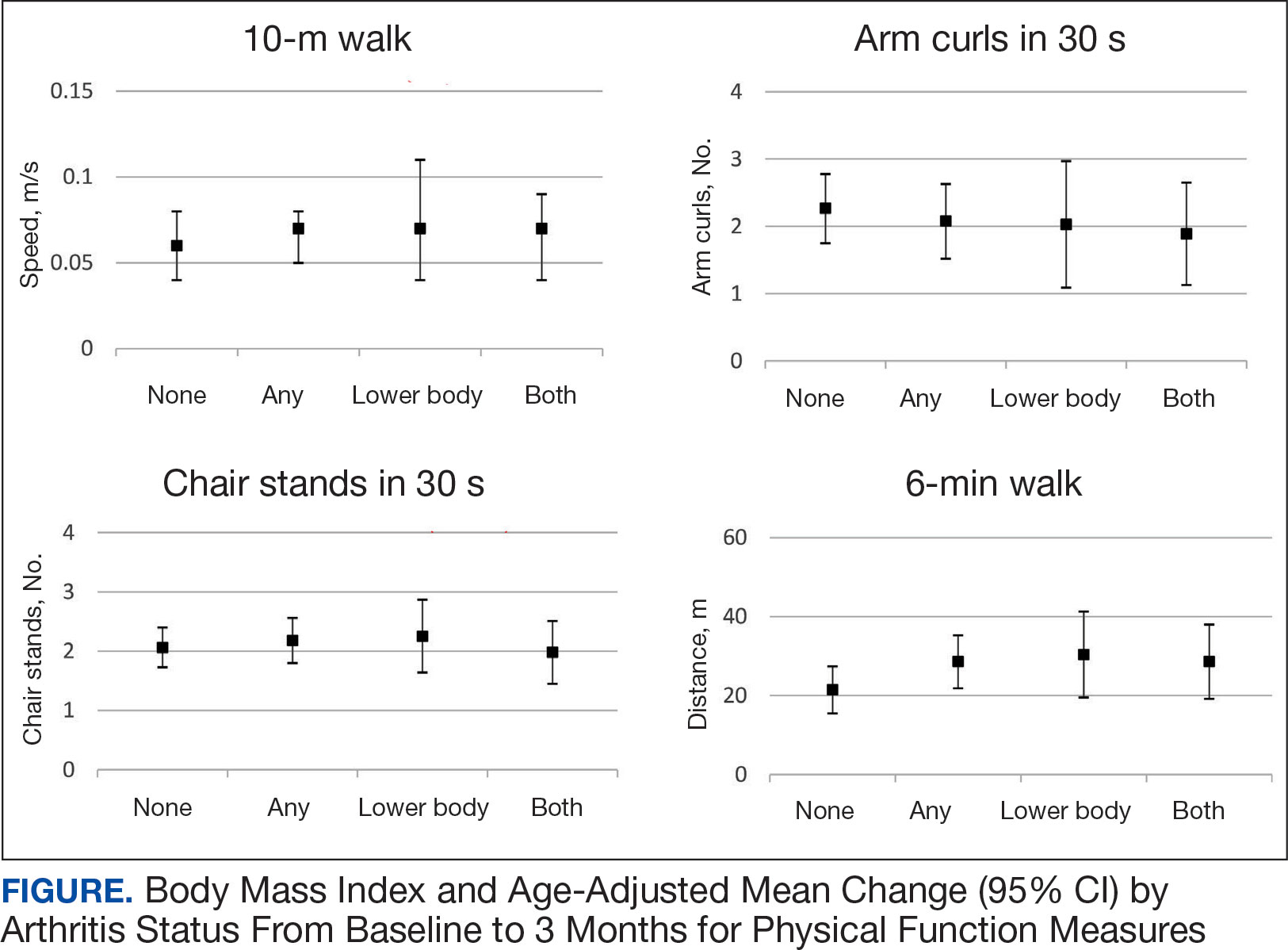

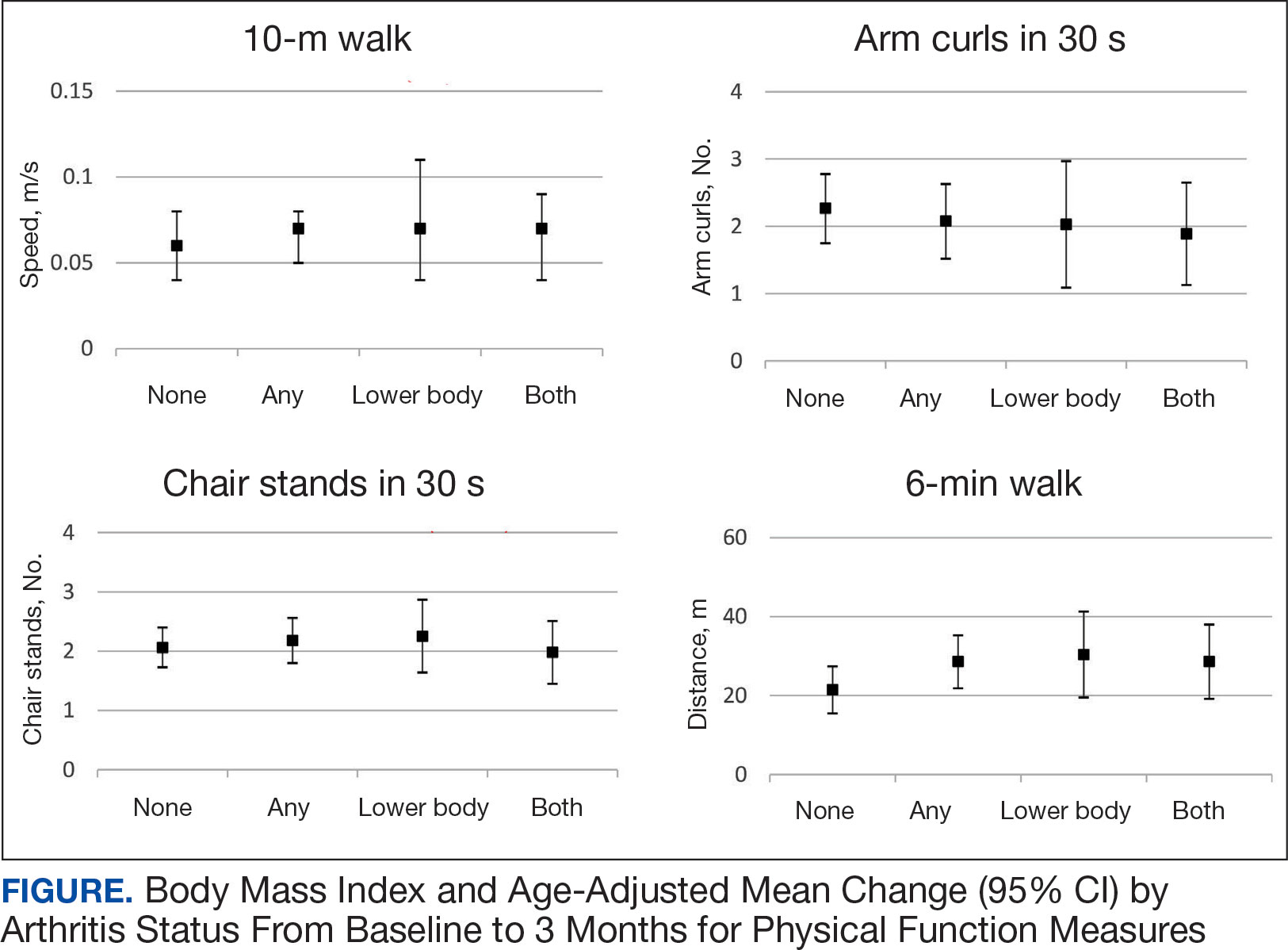

All 4 arthritis status groups showed improvements in each of the physical function measures over 3 months. For the 10MWT the mean change (95% CI) in gait speed (m/s) was 0.06 (0.04-0.08) for patients with no arthritis, 0.07 (0.05- 0.08) for any arthritis, 0.07 (0.04-0.11) for lower body arthritis, and 0.07 (0.04- 0.09) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of arm curls in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.3 (1.8-2.8) for patients with no arthritis, 2.1 (1.5-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.0 (1.1-3.0) for lower body arthritis, and 1.9 (1.1-2.7) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of chair stands in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.1 (1.7-2.4) for patients with no arthritis, 2.2 (1.8-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.3 (1.6-2.9), for lower body arthritis, and 2.0 (1.5-2.5) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the 6MWD distance in meters the mean change (95% CI) was 21.5 (15.5-27.4) for patients with no arthritis, 28.6 (21.9-35.3) for any arthritis, 30.4 (19.5-41.3) for lower body arthritis, and 28.6 (19.2-38.0) for both lower and upper body arthritis (Figure).

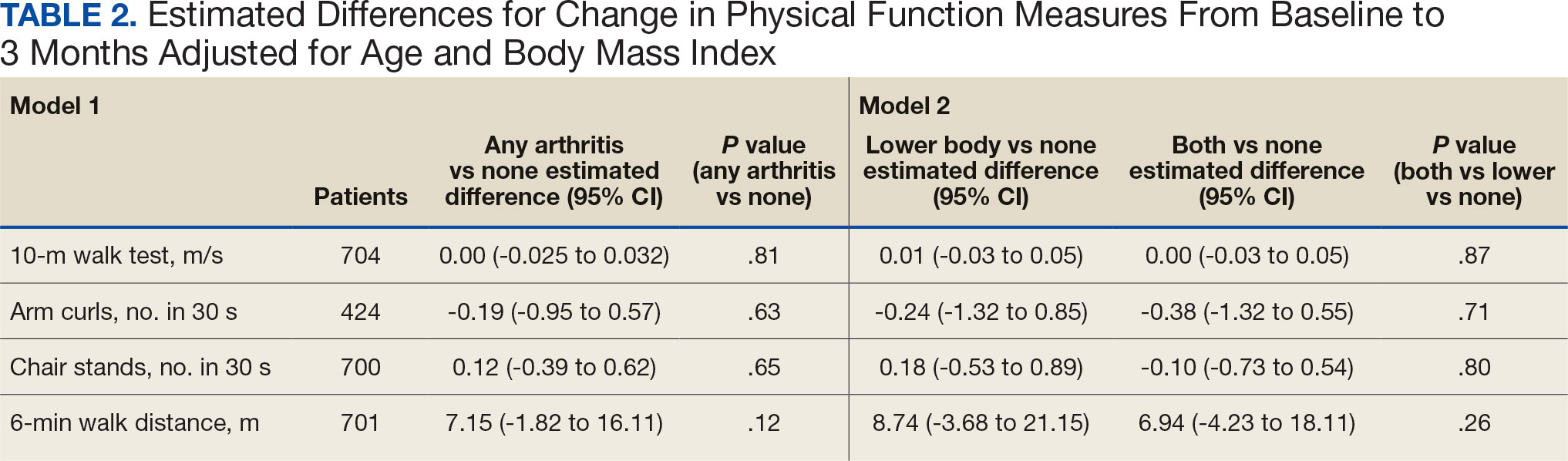

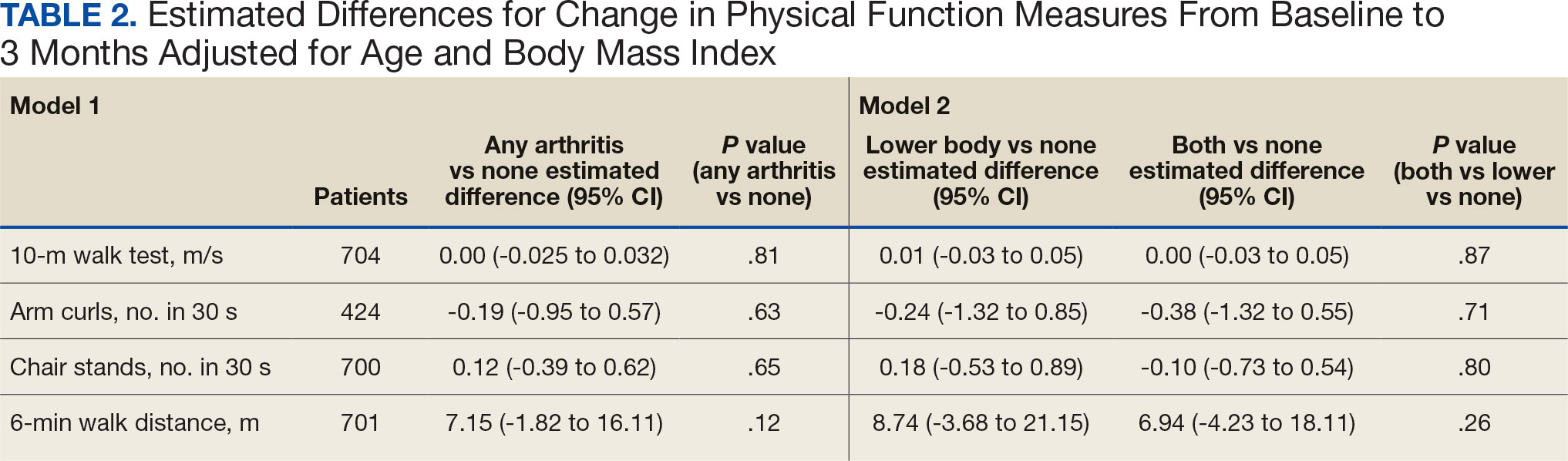

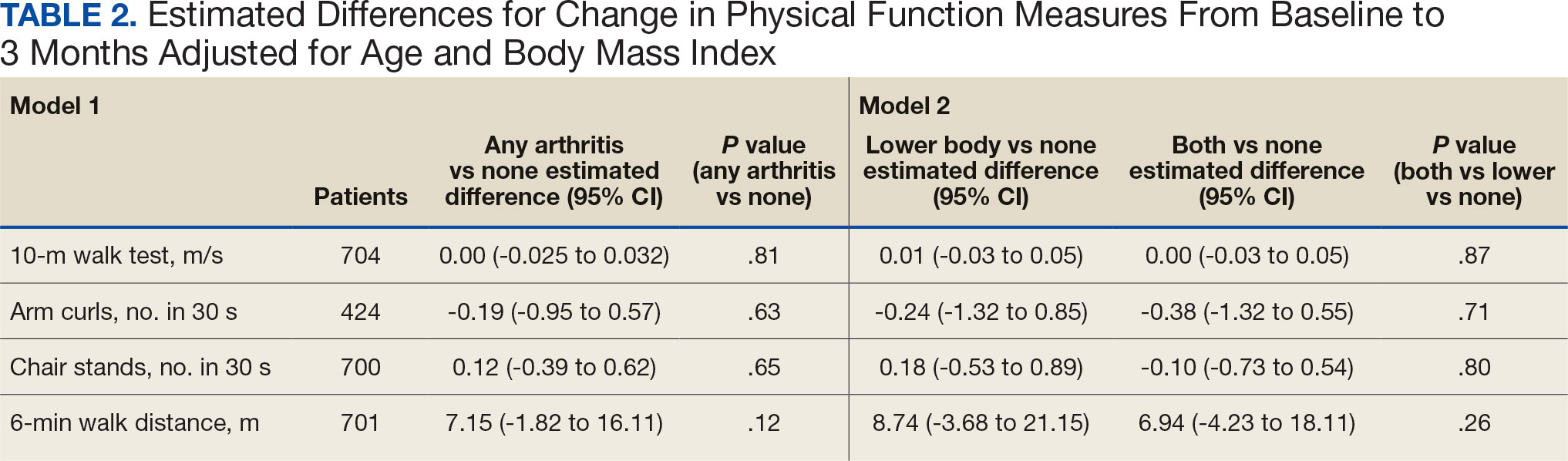

We used 2 models to measure the change from baseline to 3 months for each of the arthritis groups. Model 1 compared any arthritis vs no arthritis and model 2 compared lower body arthritis and both upper and lower body arthritis vs no arthritis for each physical function measure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in 3-month change in physical function for any of the physical function measures between arthritis groups after adjusting for age and BMI.

Discussion

Participation in Gerofit was associated with functional gains among all participants over 3 months, regardless of arthritis status. Older veterans reporting any arthritis had significantly lower physical function scores upon enrollment into Gerofit compared with those veterans reporting no arthritis. However, compared with individuals who reported no arthritis, individuals who reported arthritis (any arthritis, lower body arthritis only, or both lower and upper body arthritis) experienced similar improvements (ie, no statistically significant differences in mean change from baseline to follow-up among those with and without arthritis). This study suggests that progressive, multicomponent exercise programs for older adults may be beneficial for those with arthritis.

Involvement of multiple sites of arthritis is associated with moderate to severe functional limitations as well as lower healthrelated quality of life.23 While it has been found that individuals with arthritis can improve function with supervised exercise, even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis, it was not clear whether individuals with multiple joint involvement also would benefit.12 The results of this study suggest that these individuals can improve across various domains of physical function despite variation in arthritis location and status. As incidence of arthritis increases with age, targeting older adults for exercise programs such as Gerofit may improve functional limitations and health-related quality of life associated with arthritis.2

We evaluated physical function using multiple measures to assess upper (arm curls) and lower (chair stands, 10MWT) extremity physical function and aerobic endurance (6MWD). Participants in this study reached clinically meaningful changes with 3 months of participation in Gerofit for most of the physical function measures. Gerofit participants had a mean gait speed improvement of 0.05 to 0.07 m/s compared with 0.10 to 0.30 m/s, which was reported previously. 24,25 In this study, nearly all groups achieved the clinically important improvements in the chair stand in 30 seconds (2.0 to 2.6) and the 6MWD (21.8 to 59.1 m) that have been reported in the literature.24-26

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends the chair stand and 6MWD performance-based tests for individuals with hip and knee arthritis because they align with patient-reported outcomes and represent the types of activities relevant to this population.27 The findings of this study suggest that improvement in these physical function measures with participation in exercise align with data from arthritis-specific exercise programs designed for wide implementation. Hughes and colleagues reported improvements in the 6MWD after the 8-week Fit and Strong exercise intervention, which included walking and lower body resistance training.28 The Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease program is a 6-week walking program that has shown improvements in chair stands and gait speed.29 Another Arthritis Foundation program, People with Arthritis Can Exercise, is an 8-week course consisting of a variety of resistance, aerobic, and balance activities. This program has been associated with increases in chair stands but not gait speed or 6MWD.30,31

This study found that participation in a VHA outpatient clinical supervised exercise program results in improvements in physical function that can be realized by older adults regardless of arthritis burden. Gerofit programs typically require 1.5 to 2.0 dedicated full-time equivalent employees to run the program effectively and additional administrative support, depending on size of the program.32 The cost savings generated by the program include reductions in hospitalization rates, emergency department visits, days in hospital, and medication use and provide a compelling argument for the program’s financial viability to health care systems through long-term savings and improved health outcomes for older adults.33-36

While evidenced-based arthritis programs exist, this study illustrates that an exercise program without a focus on arthritis also improves physical function, potentially reducing the risk of disability related to arthritis. The clinical implication for these findings is that arthritis-specific exercise programs may not be needed to achieve functional improvements in individuals with arthritis. This is critical for under-resourced or exercise- limited health care systems or communities. Therefore, if exercise programming is limited, or arthritis-specific programs and interventions are not available, nonspecific exercise programs will also be beneficial to individuals with arthritis. Thus, individuals with arthritis should be encouraged to participate in any available exercise programming to achieve improvements in physical function. In addition, many older adults have multiple comorbidities, most of which improve with participation in exercise. 37 Disease-specific exercise programs can offer tailored exercises and coaching related to common barriers in participation, such as joint pain for arthritis.31 It is unclear whether these additional programmatic components are associated with greater improvements in outcomes, such as physical function. More research is needed to explore the benefits of disease-specific tailored exercise programs compared with general exercise programs.

Strengths and Limitations

This study demonstrated the effect of participation in a clinical, supervised exercise program in a real-world setting. It suggests that even exercise programs not specifically targeted for arthritis populations can improve physical function among those with arthritis.

As a VHA clinical supervised exercise program, Gerofit may not be generalizable to all older adults or other exercise programs. In addition, this analysis only included a veteran population that was > 95% male and may not be generalizable to other populations. Arthritis status was defined by self-report and not verified in the health record. However, this approach has been shown to be acceptable in this setting and the most common type of arthritis in this population (OA) is a painful musculoskeletal condition associated with functional limitations.4,22,38,39 Self-reported arthritis or rheumatism is associated with functional limitations.1 Therefore, it is unlikely that the results would differ for physician-diagnosed or radiographically defined OA. Additionally, the study did not have data on the total number of joints with arthritis or arthritis severity but rather used upper body, lower body, and both upper and lower body arthritis as a proxy for arthritis status. While our models were adjusted for age and BMI, 2 known confounding factors for the association between arthritis and physical function, there are other potential confounding factors that were not included in the models. 40,41 Finally, this study only included individuals with completed baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments, and the individuals who participated for longer or shorter periods may have had different physical function outcomes than individuals included in this study.

Conclusions

Participation in 3 months VHA Gerofit outpatient supervised exercise programs can improve physical function for all older adults, regardless of arthritis status. These programs may increase access to exercise programming that is beneficial for common conditions affecting older adults, such as arthritis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults- -United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421-426.

- Theis KA, Murphy LB, Guglielmo D, et al. Prevalence of arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2016–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1401-1407. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7040a2

- Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Allen KD, et al. Arthritis among veterans—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:999-1003.

- Park J, Mendy A, Vieira ER. Various types of arthritis in the United States: prevalence and age-related trends from 1999 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:256-258.

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2974-2982. doi:10.1002/art.30498

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, Ficke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(suppl 1):S23-S30. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Rivera JC, Amuan ME, Morris RM, Johnson AE, Pugh MJ. Arthritis, comorbidities, and care utilization in veterans of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:682-687. doi:10.1002/jor.23323

- Singh JA, Nelson DB, Fink HA, Nichol KL. Health-related quality of life predicts future health care utilization and mortality in veterans with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis: the Veterans Arthritis Quality of Life Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:755- 765. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, Cowper PA, Sullivan RJ Jr. The Gerofit Program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-S87.

- Chen MJ, Fan X, Moe ST. Criterion-related validity of the Borg ratings of perceived exertion scale in healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2002;20:873-899. doi:10.1080/026404102320761787

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, Crowley GM, Cowper PA, Robbins MS. Five-year performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Allen KD, Gol ight ly YM. State of the evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:276-283. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000161

- den Ouden MEM, Schuurmans MJ, Arts IEMA, van der Schouw YT. Association between physical performance characteristics and independence in activities of daily living in middle-aged and elderly men. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:274-280. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00890.x

- Daly M, Vidt ME, Eggebeen JD, et al. Upper extremity muscle volumes and functional strength after resistance training in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2013;21:186-207. doi:10.1123/japa.21.2.186

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420980313

- Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314-322. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:113- 119. doi:10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129-161. doi:10.1123/japa.7.2.129

- Harada ND, Chiu V, Stewart AL. Mobility-related function in older adults: assessment with a 6-minute walk test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:837-841. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90236-8

- Peeters GGME, Alshurafa M, Schaap L, de Vet HCW. Diagnostic accuracy of self-reported arthritis in the general adult population is acceptable. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.019

- Cuperus N, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Mahler EAM, Kersten CC, Hoogeboom TJ, van den Ende CHM. The clinical burden of generalized osteoarthritis represented by self-reported health-related quality of life and activity limitations: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:871-877. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-3149-1

- Coleman G, Dobson F, Hinman RS, Bennell K, White DK. Measures of physical performance. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(suppl 10):452-485. doi:10.1002/acr.24373

- Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743-749. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x

- Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, Dockerty JD, Abbott JH. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:319-327. doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.3515

- Dobson F, Hinman R, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1042- 1052. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002

- Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist. 2004;44:217-228. doi:10.1093/geront/44.2.217

- Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation's Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1098-1107. doi:10.1002/acr.20490

- Boutaugh ML. Arthritis Foundation community-based physical activity programs: effectiveness and implementation issues. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:463-470. doi:10.1002/art.11050

- Callahan LF, Mielenz T, Freburger J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the People with Arthritis Can Exercise Program: symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:92-101. doi:10.1002/art.23239

- Hall KS, Jennings SC, Pearson MP. Outpatient care models: the Gerofit model of care for exercise promotion in older adults. In: Malone ML, Boltz M, Macias Tejada J, White H, eds. Geriatrics Models of Care. Springer; 2024:205-213. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-56204-4_21

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420956751

- Abbate L, Li J, Veazie P, et al. Does Gerofit exercise reduce veterans’ use of emergency department and inpatient care? Innov Aging. 2020;4(suppl 1):771. doi:10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2786

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, Sullivan RJ Jr, Puglisi CM. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Manning KM, Hall KS, Sloane R, et al. Longitudinal analysis of physical function in older adults: the effects of physical inactivity and exercise training. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e13987. doi:10.1111/acel.13987

- Bean JF, Vora A, Frontera WR. Benefits of exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(7 suppl 3):S31-S42; quiz S3-S4. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.010

- Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, Yelin E. Pain, functional limitations, and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57:1556-1561. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02388.x

- Katz JN, Wright EA, Baron JA, Losina E. Development and validation of an index of musculoskeletal functional limitations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:62. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-62

- Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022;30:184-195. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2021.04.020

- Riebe D, Blissmer BJ, Greaney ML, Ewing Garber C, Lees FD, Clark PG. The relationship between obesity, physical activity, and physical function in older adults. J Aging Health. 2009;21:1159-1178. doi:10.1177/0898264309350076

About half of US adults aged ≥ 65 years report arthritis, and of those, 44% have an arthritis-attributable activity limitation.1,2 Arthritis is a significant health issue for veterans, with veterans reporting higher rates of disability compared with the civilian population.3

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis.4 Among individuals aged ≥ 40 years, the incidence of OA is nearly twice as high among veterans compared with civilians and is a leading cause of separation from military service and disability.5,6 OA pain and disability have been shown to be associated with increases in health care and medication use, including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and muscle relaxants.7,8 Because OA is chronic and has no cure, safe and effective management strategies—such as exercise— are critical to minimize pain and maintain physical function.9

Exercise can reduce pain and disability associated with OA and is a first-line recommendation in guidelines for the treatment of knee and hip OA.9 Given the limited exercise and high levels of physical inactivity among veterans with OA, there is a need to identify opportunities that support veterans with OA engaging in regular exercise.

Gerofit, an outpatient clinical exercise program available at 30 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) sites, may provide an opportunity for older veterans with arthritis to engage in exercise.10 Gerofit is specifically designed for veterans aged ≥ 65 years. It is not disease-specific and supports older veterans with multiple chronic conditions, including OA. Veterans aged ≥ 65 years with a referral from a VA clinician are eligible for Gerofit. Those who are unable to perform activities of daily living; unable to independently function without assistance; have a history of unstable angina, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, volatile behavioral issues, or are unable to work successfully in a group environment/setting; experience active substance abuse, homelessness, or uncontrolled incontinence; and have open wounds that cannot be appropriately dressed are excluded from Gerofit. Exercise sessions are held 3 times per week and last from 60 to 90 minutes. Sessions are supervised by Gerofit staff and include personalized exercise prescriptions based on functional assessments. Exercise prescriptions include aerobic, resistance, and balance/flexibility components and are modified by the Gerofit program staff as needed. Gerofit adopts a functional fitness approach and includes individual progression as appropriate according to evidence-based guidelines, using the Borg ratings of perceived exertion. 11 Assessments are performed at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and annually thereafter. Clinical staff conduct all assessments, including physical function testing, and record them in a database. Assessments are reviewed with the veteran to chart progress and identify future goals or needs. Veterans perform personalized self-paced exercises in the Gerofit group setting. Exercise prescriptions are continuously modified to meet individualized needs and goals. Veterans may participate continuously with no end date.

Participation in supervised exercise is associated with improved physical function and individuals with arthritis can improve function even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis. 12 In this analysis, we examine the impact of exercise on the status and location of arthritis (upper body, lower body, or both). Lower body arthritis is more common than upper body arthritis and lower extremity function is associated with increased ability to perform activities of daily living, resulting in independence among older adults.13,14 We also include upper body strength measures to capture important functional movements such as reaching and pulling.15 Among those who participate in Gerofit, the greatest gains in physical function occur during the initial 3 months, which tend to be sustained over 12 months.16 For this reason, this study focused on the initial 3 months of the program.

Older adults with arthritis may have pain and functional limitations that exceed those of the general older adult population. Exercise programs for older adults that do not specifically target arthritis but are able to improve physical function among those with arthritis could potentially increase access to exercise for older adults living with arthritis. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether change in physical function with participation in Gerofit for 3 months varies by arthritis status, including no arthritis, any arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both upper and lower body arthritis compared with no arthritis.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of previously collected data from 10 VHA Gerofit sites (Ann Arbor, Baltimore, Greater Los Angeles, Canandaigua, Cincinnati, Miami, Honolulu, Denver, Durham, and Pittsburgh) from 2002 to 2019. Implementation data regarding the consistency of the program delivery at Gerofit expansion sites have been previously published.16 Although the delivery of Gerofit transitioned to telehealth due to COVID-19, data for this analysis were collected from in-person exercise sessions prior to the pandemic.17 Data were collected for clinical purposes. This project was part of the Gerofit quality improvement initiative and was reviewed and approved by the Durham Institutional Review Board as quality improvement.

Participants in Gerofit who completed baseline and 3-month assessments were included to analyze the effects of exercise on physical function. At each of the time points, physical functional assessments included: (1) usual gait speed (> 10 meters [m/s], or 10- meter walk test [10MWT]); (2) lower body strength (chair stands [number completed in 30 seconds]); (3) upper body strength (number of arm curls [5-lb for females/8-lb for males] completed in 30 seconds); and (4) 6-minute walk distance [6MWD] in meters to measure aerobic endurance). These measures have been validated in older adults.18-21 Arm curls were added to the physical function assessments after the 10MWT, chair stands, and 6MWD; therefore, fewer participants had data for this measure. Participants self-reported at baseline on 45 common medical conditions, including arthritis or rheumatism (both upper body and lower body were offered as choices). Self-reporting has been shown to be an acceptable method of identifying arthritis in adults.22

Descriptive statistics at baseline were calculated for all participants. One-way analysis of variance and X2 tests were used to determine differences in baseline characteristics across arthritis status. The primary outcomes were changes in physical function measures from baseline to 3 months by arthritis status. Arthritis status was defined as: any arthritis, which includes individuals who reported upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both; and arthritis status individuals reporting either upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both. Categories of arthritis for arthritis status were mutually exclusive. Two separate linear models were constructed for each of the 4 physical function measures, with change from baseline to 3 months as the outcome (dependent variable) and arthritis status, age, and body mass index (BMI) as predictors (independent variables). The first model compared any arthritis with no arthritis and the second model compared arthritis status (both upper and lower body arthritis vs lower body arthritis) with no arthritis. These models were used to obtain mean changes and 95% CIs in physical function and to test for differences in the change in physical function measures by arthritis status. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.0.3.

Results

Baseline and 3-month data were available for 737 Gerofit participants and included in the analysis. The mean (SD) age was 73.5 (7.1) years. A total of 707 participants were male (95.9%) and 322 (43.6%) reported some arthritis, with arthritis in both the upper and lower body being reported by 168 participants (52.2%) (Table 1). There were no differences in age, sex, or race for those with any arthritis compared with those with no arthritis, but BMI was significantly higher in those reporting any arthritis compared with no arthritis. For the baseline functional measures, statistically significant differences were observed between those with no arthritis and those reporting any arthritis for the 10MWT (P = .001), chair stands (P = .046), and 6MWD (P = .001), but not for arm curls (P = .77), with those with no arthritis performing better.

All 4 arthritis status groups showed improvements in each of the physical function measures over 3 months. For the 10MWT the mean change (95% CI) in gait speed (m/s) was 0.06 (0.04-0.08) for patients with no arthritis, 0.07 (0.05- 0.08) for any arthritis, 0.07 (0.04-0.11) for lower body arthritis, and 0.07 (0.04- 0.09) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of arm curls in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.3 (1.8-2.8) for patients with no arthritis, 2.1 (1.5-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.0 (1.1-3.0) for lower body arthritis, and 1.9 (1.1-2.7) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of chair stands in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.1 (1.7-2.4) for patients with no arthritis, 2.2 (1.8-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.3 (1.6-2.9), for lower body arthritis, and 2.0 (1.5-2.5) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the 6MWD distance in meters the mean change (95% CI) was 21.5 (15.5-27.4) for patients with no arthritis, 28.6 (21.9-35.3) for any arthritis, 30.4 (19.5-41.3) for lower body arthritis, and 28.6 (19.2-38.0) for both lower and upper body arthritis (Figure).

We used 2 models to measure the change from baseline to 3 months for each of the arthritis groups. Model 1 compared any arthritis vs no arthritis and model 2 compared lower body arthritis and both upper and lower body arthritis vs no arthritis for each physical function measure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in 3-month change in physical function for any of the physical function measures between arthritis groups after adjusting for age and BMI.

Discussion

Participation in Gerofit was associated with functional gains among all participants over 3 months, regardless of arthritis status. Older veterans reporting any arthritis had significantly lower physical function scores upon enrollment into Gerofit compared with those veterans reporting no arthritis. However, compared with individuals who reported no arthritis, individuals who reported arthritis (any arthritis, lower body arthritis only, or both lower and upper body arthritis) experienced similar improvements (ie, no statistically significant differences in mean change from baseline to follow-up among those with and without arthritis). This study suggests that progressive, multicomponent exercise programs for older adults may be beneficial for those with arthritis.

Involvement of multiple sites of arthritis is associated with moderate to severe functional limitations as well as lower healthrelated quality of life.23 While it has been found that individuals with arthritis can improve function with supervised exercise, even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis, it was not clear whether individuals with multiple joint involvement also would benefit.12 The results of this study suggest that these individuals can improve across various domains of physical function despite variation in arthritis location and status. As incidence of arthritis increases with age, targeting older adults for exercise programs such as Gerofit may improve functional limitations and health-related quality of life associated with arthritis.2

We evaluated physical function using multiple measures to assess upper (arm curls) and lower (chair stands, 10MWT) extremity physical function and aerobic endurance (6MWD). Participants in this study reached clinically meaningful changes with 3 months of participation in Gerofit for most of the physical function measures. Gerofit participants had a mean gait speed improvement of 0.05 to 0.07 m/s compared with 0.10 to 0.30 m/s, which was reported previously. 24,25 In this study, nearly all groups achieved the clinically important improvements in the chair stand in 30 seconds (2.0 to 2.6) and the 6MWD (21.8 to 59.1 m) that have been reported in the literature.24-26

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends the chair stand and 6MWD performance-based tests for individuals with hip and knee arthritis because they align with patient-reported outcomes and represent the types of activities relevant to this population.27 The findings of this study suggest that improvement in these physical function measures with participation in exercise align with data from arthritis-specific exercise programs designed for wide implementation. Hughes and colleagues reported improvements in the 6MWD after the 8-week Fit and Strong exercise intervention, which included walking and lower body resistance training.28 The Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease program is a 6-week walking program that has shown improvements in chair stands and gait speed.29 Another Arthritis Foundation program, People with Arthritis Can Exercise, is an 8-week course consisting of a variety of resistance, aerobic, and balance activities. This program has been associated with increases in chair stands but not gait speed or 6MWD.30,31

This study found that participation in a VHA outpatient clinical supervised exercise program results in improvements in physical function that can be realized by older adults regardless of arthritis burden. Gerofit programs typically require 1.5 to 2.0 dedicated full-time equivalent employees to run the program effectively and additional administrative support, depending on size of the program.32 The cost savings generated by the program include reductions in hospitalization rates, emergency department visits, days in hospital, and medication use and provide a compelling argument for the program’s financial viability to health care systems through long-term savings and improved health outcomes for older adults.33-36

While evidenced-based arthritis programs exist, this study illustrates that an exercise program without a focus on arthritis also improves physical function, potentially reducing the risk of disability related to arthritis. The clinical implication for these findings is that arthritis-specific exercise programs may not be needed to achieve functional improvements in individuals with arthritis. This is critical for under-resourced or exercise- limited health care systems or communities. Therefore, if exercise programming is limited, or arthritis-specific programs and interventions are not available, nonspecific exercise programs will also be beneficial to individuals with arthritis. Thus, individuals with arthritis should be encouraged to participate in any available exercise programming to achieve improvements in physical function. In addition, many older adults have multiple comorbidities, most of which improve with participation in exercise. 37 Disease-specific exercise programs can offer tailored exercises and coaching related to common barriers in participation, such as joint pain for arthritis.31 It is unclear whether these additional programmatic components are associated with greater improvements in outcomes, such as physical function. More research is needed to explore the benefits of disease-specific tailored exercise programs compared with general exercise programs.

Strengths and Limitations

This study demonstrated the effect of participation in a clinical, supervised exercise program in a real-world setting. It suggests that even exercise programs not specifically targeted for arthritis populations can improve physical function among those with arthritis.

As a VHA clinical supervised exercise program, Gerofit may not be generalizable to all older adults or other exercise programs. In addition, this analysis only included a veteran population that was > 95% male and may not be generalizable to other populations. Arthritis status was defined by self-report and not verified in the health record. However, this approach has been shown to be acceptable in this setting and the most common type of arthritis in this population (OA) is a painful musculoskeletal condition associated with functional limitations.4,22,38,39 Self-reported arthritis or rheumatism is associated with functional limitations.1 Therefore, it is unlikely that the results would differ for physician-diagnosed or radiographically defined OA. Additionally, the study did not have data on the total number of joints with arthritis or arthritis severity but rather used upper body, lower body, and both upper and lower body arthritis as a proxy for arthritis status. While our models were adjusted for age and BMI, 2 known confounding factors for the association between arthritis and physical function, there are other potential confounding factors that were not included in the models. 40,41 Finally, this study only included individuals with completed baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments, and the individuals who participated for longer or shorter periods may have had different physical function outcomes than individuals included in this study.

Conclusions

Participation in 3 months VHA Gerofit outpatient supervised exercise programs can improve physical function for all older adults, regardless of arthritis status. These programs may increase access to exercise programming that is beneficial for common conditions affecting older adults, such as arthritis.

About half of US adults aged ≥ 65 years report arthritis, and of those, 44% have an arthritis-attributable activity limitation.1,2 Arthritis is a significant health issue for veterans, with veterans reporting higher rates of disability compared with the civilian population.3

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis.4 Among individuals aged ≥ 40 years, the incidence of OA is nearly twice as high among veterans compared with civilians and is a leading cause of separation from military service and disability.5,6 OA pain and disability have been shown to be associated with increases in health care and medication use, including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and muscle relaxants.7,8 Because OA is chronic and has no cure, safe and effective management strategies—such as exercise— are critical to minimize pain and maintain physical function.9

Exercise can reduce pain and disability associated with OA and is a first-line recommendation in guidelines for the treatment of knee and hip OA.9 Given the limited exercise and high levels of physical inactivity among veterans with OA, there is a need to identify opportunities that support veterans with OA engaging in regular exercise.

Gerofit, an outpatient clinical exercise program available at 30 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) sites, may provide an opportunity for older veterans with arthritis to engage in exercise.10 Gerofit is specifically designed for veterans aged ≥ 65 years. It is not disease-specific and supports older veterans with multiple chronic conditions, including OA. Veterans aged ≥ 65 years with a referral from a VA clinician are eligible for Gerofit. Those who are unable to perform activities of daily living; unable to independently function without assistance; have a history of unstable angina, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, volatile behavioral issues, or are unable to work successfully in a group environment/setting; experience active substance abuse, homelessness, or uncontrolled incontinence; and have open wounds that cannot be appropriately dressed are excluded from Gerofit. Exercise sessions are held 3 times per week and last from 60 to 90 minutes. Sessions are supervised by Gerofit staff and include personalized exercise prescriptions based on functional assessments. Exercise prescriptions include aerobic, resistance, and balance/flexibility components and are modified by the Gerofit program staff as needed. Gerofit adopts a functional fitness approach and includes individual progression as appropriate according to evidence-based guidelines, using the Borg ratings of perceived exertion. 11 Assessments are performed at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and annually thereafter. Clinical staff conduct all assessments, including physical function testing, and record them in a database. Assessments are reviewed with the veteran to chart progress and identify future goals or needs. Veterans perform personalized self-paced exercises in the Gerofit group setting. Exercise prescriptions are continuously modified to meet individualized needs and goals. Veterans may participate continuously with no end date.

Participation in supervised exercise is associated with improved physical function and individuals with arthritis can improve function even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis. 12 In this analysis, we examine the impact of exercise on the status and location of arthritis (upper body, lower body, or both). Lower body arthritis is more common than upper body arthritis and lower extremity function is associated with increased ability to perform activities of daily living, resulting in independence among older adults.13,14 We also include upper body strength measures to capture important functional movements such as reaching and pulling.15 Among those who participate in Gerofit, the greatest gains in physical function occur during the initial 3 months, which tend to be sustained over 12 months.16 For this reason, this study focused on the initial 3 months of the program.

Older adults with arthritis may have pain and functional limitations that exceed those of the general older adult population. Exercise programs for older adults that do not specifically target arthritis but are able to improve physical function among those with arthritis could potentially increase access to exercise for older adults living with arthritis. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether change in physical function with participation in Gerofit for 3 months varies by arthritis status, including no arthritis, any arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both upper and lower body arthritis compared with no arthritis.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of previously collected data from 10 VHA Gerofit sites (Ann Arbor, Baltimore, Greater Los Angeles, Canandaigua, Cincinnati, Miami, Honolulu, Denver, Durham, and Pittsburgh) from 2002 to 2019. Implementation data regarding the consistency of the program delivery at Gerofit expansion sites have been previously published.16 Although the delivery of Gerofit transitioned to telehealth due to COVID-19, data for this analysis were collected from in-person exercise sessions prior to the pandemic.17 Data were collected for clinical purposes. This project was part of the Gerofit quality improvement initiative and was reviewed and approved by the Durham Institutional Review Board as quality improvement.

Participants in Gerofit who completed baseline and 3-month assessments were included to analyze the effects of exercise on physical function. At each of the time points, physical functional assessments included: (1) usual gait speed (> 10 meters [m/s], or 10- meter walk test [10MWT]); (2) lower body strength (chair stands [number completed in 30 seconds]); (3) upper body strength (number of arm curls [5-lb for females/8-lb for males] completed in 30 seconds); and (4) 6-minute walk distance [6MWD] in meters to measure aerobic endurance). These measures have been validated in older adults.18-21 Arm curls were added to the physical function assessments after the 10MWT, chair stands, and 6MWD; therefore, fewer participants had data for this measure. Participants self-reported at baseline on 45 common medical conditions, including arthritis or rheumatism (both upper body and lower body were offered as choices). Self-reporting has been shown to be an acceptable method of identifying arthritis in adults.22

Descriptive statistics at baseline were calculated for all participants. One-way analysis of variance and X2 tests were used to determine differences in baseline characteristics across arthritis status. The primary outcomes were changes in physical function measures from baseline to 3 months by arthritis status. Arthritis status was defined as: any arthritis, which includes individuals who reported upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both; and arthritis status individuals reporting either upper body arthritis, lower body arthritis, or both. Categories of arthritis for arthritis status were mutually exclusive. Two separate linear models were constructed for each of the 4 physical function measures, with change from baseline to 3 months as the outcome (dependent variable) and arthritis status, age, and body mass index (BMI) as predictors (independent variables). The first model compared any arthritis with no arthritis and the second model compared arthritis status (both upper and lower body arthritis vs lower body arthritis) with no arthritis. These models were used to obtain mean changes and 95% CIs in physical function and to test for differences in the change in physical function measures by arthritis status. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.0.3.

Results

Baseline and 3-month data were available for 737 Gerofit participants and included in the analysis. The mean (SD) age was 73.5 (7.1) years. A total of 707 participants were male (95.9%) and 322 (43.6%) reported some arthritis, with arthritis in both the upper and lower body being reported by 168 participants (52.2%) (Table 1). There were no differences in age, sex, or race for those with any arthritis compared with those with no arthritis, but BMI was significantly higher in those reporting any arthritis compared with no arthritis. For the baseline functional measures, statistically significant differences were observed between those with no arthritis and those reporting any arthritis for the 10MWT (P = .001), chair stands (P = .046), and 6MWD (P = .001), but not for arm curls (P = .77), with those with no arthritis performing better.

All 4 arthritis status groups showed improvements in each of the physical function measures over 3 months. For the 10MWT the mean change (95% CI) in gait speed (m/s) was 0.06 (0.04-0.08) for patients with no arthritis, 0.07 (0.05- 0.08) for any arthritis, 0.07 (0.04-0.11) for lower body arthritis, and 0.07 (0.04- 0.09) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of arm curls in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.3 (1.8-2.8) for patients with no arthritis, 2.1 (1.5-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.0 (1.1-3.0) for lower body arthritis, and 1.9 (1.1-2.7) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the number of chair stands in 30 seconds the mean change (95% CI) was 2.1 (1.7-2.4) for patients with no arthritis, 2.2 (1.8-2.6) for any arthritis, 2.3 (1.6-2.9), for lower body arthritis, and 2.0 (1.5-2.5) for both lower and upper body arthritis. For the 6MWD distance in meters the mean change (95% CI) was 21.5 (15.5-27.4) for patients with no arthritis, 28.6 (21.9-35.3) for any arthritis, 30.4 (19.5-41.3) for lower body arthritis, and 28.6 (19.2-38.0) for both lower and upper body arthritis (Figure).

We used 2 models to measure the change from baseline to 3 months for each of the arthritis groups. Model 1 compared any arthritis vs no arthritis and model 2 compared lower body arthritis and both upper and lower body arthritis vs no arthritis for each physical function measure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in 3-month change in physical function for any of the physical function measures between arthritis groups after adjusting for age and BMI.

Discussion

Participation in Gerofit was associated with functional gains among all participants over 3 months, regardless of arthritis status. Older veterans reporting any arthritis had significantly lower physical function scores upon enrollment into Gerofit compared with those veterans reporting no arthritis. However, compared with individuals who reported no arthritis, individuals who reported arthritis (any arthritis, lower body arthritis only, or both lower and upper body arthritis) experienced similar improvements (ie, no statistically significant differences in mean change from baseline to follow-up among those with and without arthritis). This study suggests that progressive, multicomponent exercise programs for older adults may be beneficial for those with arthritis.

Involvement of multiple sites of arthritis is associated with moderate to severe functional limitations as well as lower healthrelated quality of life.23 While it has been found that individuals with arthritis can improve function with supervised exercise, even though their baseline functional status is lower than individuals without arthritis, it was not clear whether individuals with multiple joint involvement also would benefit.12 The results of this study suggest that these individuals can improve across various domains of physical function despite variation in arthritis location and status. As incidence of arthritis increases with age, targeting older adults for exercise programs such as Gerofit may improve functional limitations and health-related quality of life associated with arthritis.2

We evaluated physical function using multiple measures to assess upper (arm curls) and lower (chair stands, 10MWT) extremity physical function and aerobic endurance (6MWD). Participants in this study reached clinically meaningful changes with 3 months of participation in Gerofit for most of the physical function measures. Gerofit participants had a mean gait speed improvement of 0.05 to 0.07 m/s compared with 0.10 to 0.30 m/s, which was reported previously. 24,25 In this study, nearly all groups achieved the clinically important improvements in the chair stand in 30 seconds (2.0 to 2.6) and the 6MWD (21.8 to 59.1 m) that have been reported in the literature.24-26

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends the chair stand and 6MWD performance-based tests for individuals with hip and knee arthritis because they align with patient-reported outcomes and represent the types of activities relevant to this population.27 The findings of this study suggest that improvement in these physical function measures with participation in exercise align with data from arthritis-specific exercise programs designed for wide implementation. Hughes and colleagues reported improvements in the 6MWD after the 8-week Fit and Strong exercise intervention, which included walking and lower body resistance training.28 The Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease program is a 6-week walking program that has shown improvements in chair stands and gait speed.29 Another Arthritis Foundation program, People with Arthritis Can Exercise, is an 8-week course consisting of a variety of resistance, aerobic, and balance activities. This program has been associated with increases in chair stands but not gait speed or 6MWD.30,31

This study found that participation in a VHA outpatient clinical supervised exercise program results in improvements in physical function that can be realized by older adults regardless of arthritis burden. Gerofit programs typically require 1.5 to 2.0 dedicated full-time equivalent employees to run the program effectively and additional administrative support, depending on size of the program.32 The cost savings generated by the program include reductions in hospitalization rates, emergency department visits, days in hospital, and medication use and provide a compelling argument for the program’s financial viability to health care systems through long-term savings and improved health outcomes for older adults.33-36

While evidenced-based arthritis programs exist, this study illustrates that an exercise program without a focus on arthritis also improves physical function, potentially reducing the risk of disability related to arthritis. The clinical implication for these findings is that arthritis-specific exercise programs may not be needed to achieve functional improvements in individuals with arthritis. This is critical for under-resourced or exercise- limited health care systems or communities. Therefore, if exercise programming is limited, or arthritis-specific programs and interventions are not available, nonspecific exercise programs will also be beneficial to individuals with arthritis. Thus, individuals with arthritis should be encouraged to participate in any available exercise programming to achieve improvements in physical function. In addition, many older adults have multiple comorbidities, most of which improve with participation in exercise. 37 Disease-specific exercise programs can offer tailored exercises and coaching related to common barriers in participation, such as joint pain for arthritis.31 It is unclear whether these additional programmatic components are associated with greater improvements in outcomes, such as physical function. More research is needed to explore the benefits of disease-specific tailored exercise programs compared with general exercise programs.

Strengths and Limitations

This study demonstrated the effect of participation in a clinical, supervised exercise program in a real-world setting. It suggests that even exercise programs not specifically targeted for arthritis populations can improve physical function among those with arthritis.

As a VHA clinical supervised exercise program, Gerofit may not be generalizable to all older adults or other exercise programs. In addition, this analysis only included a veteran population that was > 95% male and may not be generalizable to other populations. Arthritis status was defined by self-report and not verified in the health record. However, this approach has been shown to be acceptable in this setting and the most common type of arthritis in this population (OA) is a painful musculoskeletal condition associated with functional limitations.4,22,38,39 Self-reported arthritis or rheumatism is associated with functional limitations.1 Therefore, it is unlikely that the results would differ for physician-diagnosed or radiographically defined OA. Additionally, the study did not have data on the total number of joints with arthritis or arthritis severity but rather used upper body, lower body, and both upper and lower body arthritis as a proxy for arthritis status. While our models were adjusted for age and BMI, 2 known confounding factors for the association between arthritis and physical function, there are other potential confounding factors that were not included in the models. 40,41 Finally, this study only included individuals with completed baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments, and the individuals who participated for longer or shorter periods may have had different physical function outcomes than individuals included in this study.

Conclusions

Participation in 3 months VHA Gerofit outpatient supervised exercise programs can improve physical function for all older adults, regardless of arthritis status. These programs may increase access to exercise programming that is beneficial for common conditions affecting older adults, such as arthritis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults- -United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421-426.

- Theis KA, Murphy LB, Guglielmo D, et al. Prevalence of arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2016–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1401-1407. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7040a2

- Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Allen KD, et al. Arthritis among veterans—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:999-1003.

- Park J, Mendy A, Vieira ER. Various types of arthritis in the United States: prevalence and age-related trends from 1999 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:256-258.

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2974-2982. doi:10.1002/art.30498

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, Ficke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(suppl 1):S23-S30. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Rivera JC, Amuan ME, Morris RM, Johnson AE, Pugh MJ. Arthritis, comorbidities, and care utilization in veterans of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:682-687. doi:10.1002/jor.23323

- Singh JA, Nelson DB, Fink HA, Nichol KL. Health-related quality of life predicts future health care utilization and mortality in veterans with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis: the Veterans Arthritis Quality of Life Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:755- 765. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, Cowper PA, Sullivan RJ Jr. The Gerofit Program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-S87.

- Chen MJ, Fan X, Moe ST. Criterion-related validity of the Borg ratings of perceived exertion scale in healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2002;20:873-899. doi:10.1080/026404102320761787

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, Crowley GM, Cowper PA, Robbins MS. Five-year performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Allen KD, Gol ight ly YM. State of the evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:276-283. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000161

- den Ouden MEM, Schuurmans MJ, Arts IEMA, van der Schouw YT. Association between physical performance characteristics and independence in activities of daily living in middle-aged and elderly men. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:274-280. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00890.x

- Daly M, Vidt ME, Eggebeen JD, et al. Upper extremity muscle volumes and functional strength after resistance training in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2013;21:186-207. doi:10.1123/japa.21.2.186

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420980313

- Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314-322. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:113- 119. doi:10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129-161. doi:10.1123/japa.7.2.129

- Harada ND, Chiu V, Stewart AL. Mobility-related function in older adults: assessment with a 6-minute walk test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:837-841. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90236-8

- Peeters GGME, Alshurafa M, Schaap L, de Vet HCW. Diagnostic accuracy of self-reported arthritis in the general adult population is acceptable. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.019

- Cuperus N, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Mahler EAM, Kersten CC, Hoogeboom TJ, van den Ende CHM. The clinical burden of generalized osteoarthritis represented by self-reported health-related quality of life and activity limitations: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:871-877. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-3149-1

- Coleman G, Dobson F, Hinman RS, Bennell K, White DK. Measures of physical performance. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(suppl 10):452-485. doi:10.1002/acr.24373

- Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743-749. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x

- Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, Dockerty JD, Abbott JH. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:319-327. doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.3515

- Dobson F, Hinman R, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1042- 1052. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002

- Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist. 2004;44:217-228. doi:10.1093/geront/44.2.217

- Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation's Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1098-1107. doi:10.1002/acr.20490

- Boutaugh ML. Arthritis Foundation community-based physical activity programs: effectiveness and implementation issues. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:463-470. doi:10.1002/art.11050

- Callahan LF, Mielenz T, Freburger J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the People with Arthritis Can Exercise Program: symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:92-101. doi:10.1002/art.23239

- Hall KS, Jennings SC, Pearson MP. Outpatient care models: the Gerofit model of care for exercise promotion in older adults. In: Malone ML, Boltz M, Macias Tejada J, White H, eds. Geriatrics Models of Care. Springer; 2024:205-213. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-56204-4_21

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420956751

- Abbate L, Li J, Veazie P, et al. Does Gerofit exercise reduce veterans’ use of emergency department and inpatient care? Innov Aging. 2020;4(suppl 1):771. doi:10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2786

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, Sullivan RJ Jr, Puglisi CM. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Manning KM, Hall KS, Sloane R, et al. Longitudinal analysis of physical function in older adults: the effects of physical inactivity and exercise training. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e13987. doi:10.1111/acel.13987

- Bean JF, Vora A, Frontera WR. Benefits of exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(7 suppl 3):S31-S42; quiz S3-S4. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.010

- Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, Yelin E. Pain, functional limitations, and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57:1556-1561. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02388.x

- Katz JN, Wright EA, Baron JA, Losina E. Development and validation of an index of musculoskeletal functional limitations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:62. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-62

- Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022;30:184-195. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2021.04.020

- Riebe D, Blissmer BJ, Greaney ML, Ewing Garber C, Lees FD, Clark PG. The relationship between obesity, physical activity, and physical function in older adults. J Aging Health. 2009;21:1159-1178. doi:10.1177/0898264309350076

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults- -United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421-426.

- Theis KA, Murphy LB, Guglielmo D, et al. Prevalence of arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2016–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1401-1407. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7040a2

- Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Allen KD, et al. Arthritis among veterans—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:999-1003.

- Park J, Mendy A, Vieira ER. Various types of arthritis in the United States: prevalence and age-related trends from 1999 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:256-258.

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2974-2982. doi:10.1002/art.30498

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, Ficke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(suppl 1):S23-S30. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Rivera JC, Amuan ME, Morris RM, Johnson AE, Pugh MJ. Arthritis, comorbidities, and care utilization in veterans of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:682-687. doi:10.1002/jor.23323

- Singh JA, Nelson DB, Fink HA, Nichol KL. Health-related quality of life predicts future health care utilization and mortality in veterans with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis: the Veterans Arthritis Quality of Life Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:755- 765. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, Cowper PA, Sullivan RJ Jr. The Gerofit Program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-S87.

- Chen MJ, Fan X, Moe ST. Criterion-related validity of the Borg ratings of perceived exertion scale in healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2002;20:873-899. doi:10.1080/026404102320761787

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, Crowley GM, Cowper PA, Robbins MS. Five-year performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Allen KD, Gol ight ly YM. State of the evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:276-283. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000161

- den Ouden MEM, Schuurmans MJ, Arts IEMA, van der Schouw YT. Association between physical performance characteristics and independence in activities of daily living in middle-aged and elderly men. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:274-280. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00890.x

- Daly M, Vidt ME, Eggebeen JD, et al. Upper extremity muscle volumes and functional strength after resistance training in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2013;21:186-207. doi:10.1123/japa.21.2.186

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420980313

- Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314-322. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:113- 119. doi:10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129-161. doi:10.1123/japa.7.2.129

- Harada ND, Chiu V, Stewart AL. Mobility-related function in older adults: assessment with a 6-minute walk test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:837-841. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90236-8

- Peeters GGME, Alshurafa M, Schaap L, de Vet HCW. Diagnostic accuracy of self-reported arthritis in the general adult population is acceptable. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.019

- Cuperus N, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Mahler EAM, Kersten CC, Hoogeboom TJ, van den Ende CHM. The clinical burden of generalized osteoarthritis represented by self-reported health-related quality of life and activity limitations: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:871-877. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-3149-1

- Coleman G, Dobson F, Hinman RS, Bennell K, White DK. Measures of physical performance. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(suppl 10):452-485. doi:10.1002/acr.24373

- Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743-749. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x

- Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, Dockerty JD, Abbott JH. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:319-327. doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.3515

- Dobson F, Hinman R, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1042- 1052. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002

- Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist. 2004;44:217-228. doi:10.1093/geront/44.2.217

- Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation's Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1098-1107. doi:10.1002/acr.20490

- Boutaugh ML. Arthritis Foundation community-based physical activity programs: effectiveness and implementation issues. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:463-470. doi:10.1002/art.11050

- Callahan LF, Mielenz T, Freburger J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the People with Arthritis Can Exercise Program: symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:92-101. doi:10.1002/art.23239

- Hall KS, Jennings SC, Pearson MP. Outpatient care models: the Gerofit model of care for exercise promotion in older adults. In: Malone ML, Boltz M, Macias Tejada J, White H, eds. Geriatrics Models of Care. Springer; 2024:205-213. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-56204-4_21

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/ 2333721420956751

- Abbate L, Li J, Veazie P, et al. Does Gerofit exercise reduce veterans’ use of emergency department and inpatient care? Innov Aging. 2020;4(suppl 1):771. doi:10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2786

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, Sullivan RJ Jr, Puglisi CM. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Manning KM, Hall KS, Sloane R, et al. Longitudinal analysis of physical function in older adults: the effects of physical inactivity and exercise training. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e13987. doi:10.1111/acel.13987

- Bean JF, Vora A, Frontera WR. Benefits of exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(7 suppl 3):S31-S42; quiz S3-S4. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.010