User login

Gallstones: Watch and wait, or intervene?

The prevalence of gallstones is approximately 10% to 15% of the adult US population.1,2 Most cases are asymptomatic, as gallstones are usually discovered incidentally during routine imaging for other abdominal conditions, and only about 20% of patients with asymptomatic gallstones develop clinically significant complications.2,3

Nevertheless, gallstones carry significant healthcare costs. In 2004, the median inpatient cost for any gallstone-related disease was $11,584, with an overall annual cost of $6.2 billion.4,5

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard treatment for symptomatic cholelithiasis. For asymptomatic cholelithasis, the usual approach is expectant management (“watch and wait”), but prophylactic cholecystectomy may be an option in certain patients at high risk.

CHEMICAL COMPOSITION

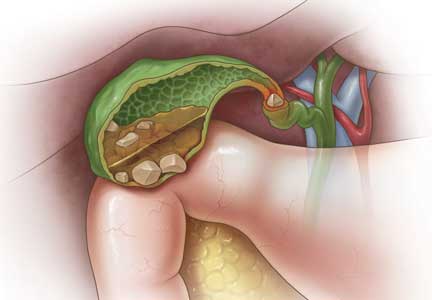

Gallstones can be classified into 2 main categories based on their predominant chemical composition: cholesterol or pigment.

Cholesterol gallstones

About 75% of gallstones are composed of cholesterol.3,4 In the past, this type of stone was thought to be caused by gallbladder inflammation, bile stasis, and absorption of bile salts from damaged mucosa. However, it is now known that cholesterol gallstones are the result of biliary supersaturation caused by cholesterol hypersecretion into the gallbladder, gallbladder hypomotility, accelerated cholesterol nucleation and crystallization, and mucin gel accumulation.

Pigment gallstones

Black pigment gallstones account for 10% to 15% of all gallstones.6 They are caused by chronic hemolysis in association with supersaturation of bile with calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, along with deposition of calcium carbonate, phosphate, and inorganic salts.7

Brown pigment stones, accounting for 5% to 10% of all gallstones,6 are caused by infection in the obstructed bile ducts, where bacteria that produce beta-glucuronidase, phospholipase, and slime contribute to formation of the stone.8,9

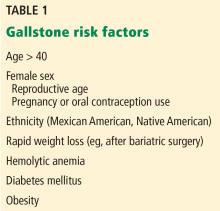

RISK FACTORS FOR GALLSTONES

Age. After age 40, the risk increases dramatically, with an incidence 4 times higher for those ages 40 to 69 than in younger people.10

Female sex. Women of reproductive age are 4 times more likely to develop gallstones than men, but this gap narrows after menopause.11 The higher risk is attributed to female sex hormones, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Estrogen decreases secretion of bile salts and increases secretion of cholesterol into the gallbladder, which leads to cholesterol supersaturation. Progesterone acts synergistically by causing hypomobility of the gallbladder, which in turn leads to bile stasis.12,13

Ethnicity. The risk is higher in Mexican Americans and Native Americans than in other ethnic groups.14

Rapid weight loss, such as after bariatric surgery, occurs from decreased caloric intake and promotes bile stasis, while lipolysis increases cholesterol mobilization and secretion into the gallbladder. This creates an environment conducive to bile supersaturation with cholesterol, leading to gallstone formation.

Chronic hemolytic disorders carry an increased risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones due to increased excretion of bilirubin during hemolysis.

Obesity and diabetes mellitus are both attributed to insulin resistance. Obesity also increases bile stasis and cholesterol saturation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GALLSTONES (CHOLELITHIASIS)

Most patients with gallstones (cholelithiasis) experience no symptoms. Their gallstones are often discovered incidentally during imaging tests for unrelated or unexplained abdominal symptoms. Most patients with asymptomatic gallstones remain symptom-free, while about 20% develop gallstone-related symptoms.2,3

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom. The phrase biliary colic—suggesting pain that is fluctuating in nature—appears ubiquitously in the medical literature, but it does not correctly characterize the pain associated with gallstones.

Most patients with gallstone symptoms describe a constant and often severe pain in the right upper abdomen, epigastrium, or both, often persisting for 30 to 120 minutes. Symptoms are frequently reported in the epigastrium when only visceral pain fibers are stimulated due to gallbladder distention. This is usually called midline pain; however, pain occurs in the back and right shoulder in up to 60% of patients, with involvement of somatic fibers.15,16 Gallstone pain is not relieved by change of position or passage of stool or gas.

Onset of symptoms more than an hour after eating or in the late evening or at night also very strongly suggests biliary pain. Patients with a history of biliary pain are more likely to experience it again, with a 69% chance of developing recurrent pain within 2 years.17

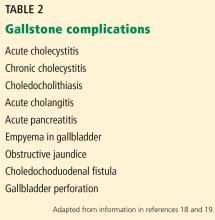

GALLSTONE-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Acute gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis)

Gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) is the most common complication, occurring in up to 10% of symptomatic cases. Many patients with acute cholecystitis present with right upper quadrant pain that may be accompanied by anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Inspiratory arrest on deep palpation of the right upper quadrant (Murphy sign) has a specificity of 79% to 96% for acute cholecystitis.20 Markers of systemic inflammation such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, and elevated C-reactive protein are highly suggestive of acute cholecystitis.20,21

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis)

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis) are detected in 3.4% to 12% of patients with gallstones.22,23 Most stones in the common bile duct migrate there from the gallbladder via the cystic duct. Less commonly, primary duct stones form in the duct due to biliary stasis. Removing the gallbladder does not completely eliminate the risk of bile duct stones, as stones can remain or recur after surgery.

Bile duct stones can obstruct the common bile duct, which disrupts normal bile flow and leads to jaundice. Other symptoms may include pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting. Serum levels of bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase are usually high.24

Acute bacterial infection (cholangitis)

Acute bacterial infection of the biliary system (cholangitis) is usually associated with obstruction of the common bile duct. Common symptoms of acute cholangitis include right upper quadrant pain, fever, and jaundice (Charcot triad), and these are present in about 50% to 75% of cases.21 In severe cases, patients can develop altered mental status and septicemic shock in addition to the Charcot triad, a condition called the Reynold pentad. White blood cell counts and serum levels of C-reactive protein, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and alkaline phosphatase are usually elevated.21

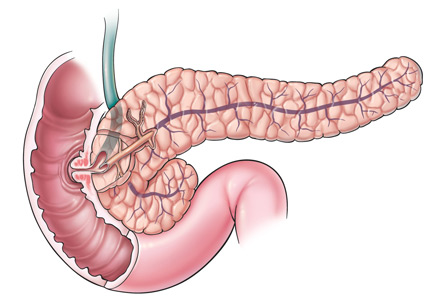

Pancreatitis

Approximately 4% to 8% of patients with gallstones develop inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).25 The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least 2 of the following:26,27

- Abdominal pain (typically epigastric, often radiating to the back)

- Amylase or lipase levels at least 3 times above the normal limit

- Imaging findings that suggest acute pancreatitis.

Gallstone-related pancreatitis should be considered if the ALT level is greater than 150 U/mL, which has a 97% specificity for gallstone-related pancreatitis.28

ABDOMINAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY FOR DIAGNOSIS

Transabdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of 84% to 89% and a specificity of up to 99%, is the test of choice for detecting gallstones.29 The characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis on ultrasonography include enlargement of the gallbladder, thickening of the gallbladder wall, presence of pericholecystic fluid, and tenderness elicited by the ultrasound probe over the gallbladder (sonographic Murphy sign).

Scintigraphy as a second test

Acute cholecystitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis and typically does not require additional imaging beyond ultrasonography. When there is discordance between clinical and ultrasonographic findings, the most accurate second imaging test is scintigraphy of the biliary tract, usually performed with technetium-labeled hydroxy iminodiacetic acid. Given intravenously, the radionuclide is rapidly taken up by the liver and then secreted into the bile. In acute cholecystitis, the cystic duct is functionally occluded and the isotope does not enter the gallbladder, creating an imaging void compared with a normal appearance.

Scintigraphy is more sensitive than abdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of up to 97% vs 81% to 88%, respectively.29,30 The tests have about equal specificity.

Even though scintigraphy is more sensitive, abdominal ultrasonography is often the initial test for patients with suspected acute cholecystitis because it is more widely available, takes less time, does not involve radiation exposure, and can assess for the presence or absence of gallstones and dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts.

Looking for stones in the common bile duct

When acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography is a prudent initial test to look for gallstones or biliary dilation suggesting obstruction by stones in the common bile duct. Abdominal ultrasonography has only a 22% to 55% sensitivity for visualizing stones in the common bile duct, but it has a 77% to 87% sensitivity for detecting common bile duct dilation, a surrogate marker of stones.31

The normal bile duct diameter ranges from 3 to 6 mm, although mild dilation is often seen in older patients or after cholecystectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.32,33 Bile duct dilation of up to 10 mm can be considered normal in patients after cholecystectomy.34 A normal-appearing bile duct on ultrasonography has a negative predictive value of 95% for excluding common bile duct stones.31

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have similar sensitivity (89%–94%, 85%–92%, and 89%–93%, respectively) and specificity (94%–95%, 93%–97%, and 100%, respectively) for detecting common bile duct stones.35–37 EUS is superior to MRCP in detecting stones smaller than 6 mm.38

ERCP should be reserved for managing rather than diagnosing common bile duct stones because of the risk of pancreatitis and perforation. Patients undergoing cholecystectomy who are suspected of having choledocholithiasis may undergo intraoperative cholangiography or laparoscopic common bile duct ultrasonography.

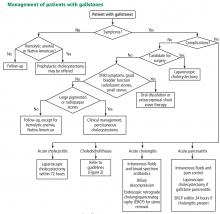

WATCH AND WAIT, OR INTERVENE?

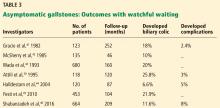

Asymptomatic gallstones

Standard treatment for these patients is expectant management. Cholecystectomy is not recommended for patients with asymptomatic gallstones.47 Nevertheless, some patients may benefit from prophylactic cholecystectomy. We and others48 suggest considering cholecystectomy in the following patients.

Patients with chronic hemolytic anemia (including children with sickle cell anemia and spherocytosis). These patients have a higher risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones, and cholecystectomy has improved outcomes.49 It should be noted that most of these data come from pediatric populations and have been extrapolated to adults.

Native Americans, who have a higher risk of gallbladder cancer if they have gallstones.2,50

Conversely, calcification of the gallbladder wall (“porcelain gallbladder”) is no longer considered an absolute indication for cholecystectomy. This condition was thought to be associated with a high rate of gallbladder carcinoma, but analyses of larger, more recent data sets found much smaller risks.51,52 Further, cholecystectomy in these patients was found to be associated with high rates of postoperative complications. Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy is no longer recommended in asymptomatic cases of porcelain gallbladder.

In addition, concomitant cholecystectomy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery is no longer considered the therapeutic standard. Historically, cholecystectomy was performed in these patients because of the increased risk of gallstones associated with rapid weight loss after surgery. However, research now weighs against concomitant cholecystectomy with bariatric surgery and most other abdominal surgeries for asymptomatic gallstones.53

Laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic gallstones

For patients experiencing acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.48 There were safety concerns regarding higher rates of morbidity and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy in patients who underwent surgery before the acute cholecystitis episode had settled. However, a large meta-analysis found no significant difference between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in bile duct injury or conversion rates.54 Further, early cholecystectomy—defined as within 1 week of symptom onset—has been found to reduce gallstone-related complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower costs.55–57 If the patient cannot undergo surgery, percutaneous cholecystotomy or novel endoscopic gallbladder drainage interventions can be used.

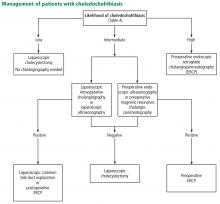

Several variables predict the presence of bile duct stones in patients who have symptoms (Table 4). Based on these predictors, the ASGE classifies the probabilities as low (< 10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), and high (> 50%)31:

- High-risk patients should undergo preoperative ERCP and stone extraction if needed

- Intermediate-risk patients should undergo preoperative imaging with EUS or MRCP or intraoperative bile duct evaluation, depending on the availability, costs, and local expertise.

Patients with associated cholangitis should be given intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Biliary decompression should be done as early as possible to decrease the risk of morbidity and mortality. For acute cholangitis, ERCP is the treatment of choice.25

Patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis should receive conservative management with intravenous isotonic solutions and pain control, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.48

The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute gallstone pancreatitis has been debated. Studies conducted during the era of open cholecystectomy reported similar or worse outcomes if cholecystectomy was done sooner rather than later.

However, in 1999, Uhl et al58 reported that 48 of 77 patients admitted with acute gallstone pancreatitis were able to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same admission. Success rates were 85% (30 of 35 patients) in those with mild disease and 62% (8 of 13 patients) in those with severe disease. They concluded laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be safely performed within 7 days in patients with mild disease, whereas in severe disease at least 3 weeks should elapse because of the risk of infection.

In a randomized trial published in 2010, Aboulian et al59 reported that hospital length of stay (the primary end point) was shorter in 25 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy early (within 48 hours of admission) than in 25 patients who underwent surgery after abdominal pain had resolved and laboratory enzymes showed a normalizing trend, 3.5 vs 5.8 days (P = .0016). Rates of perioperative complications and need for conversion to open surgery were similar between the 2 groups.

If there is associated cholangitis, patients should also be given broad-spectrum antibiotics and should undergo ERCP within 24 hours of admission.25–27

SUMMARY

Gallstones are common in US adults. Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging test of choice to detect gallbladder stones and assess for findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis and dilation of the common bile duct. Fortunately, most gallstones are asymptomatic and can usually be managed expectantly. In patients who have symptoms or have gallstone complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard of care.

- Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2005; 15(3):329–338. doi:10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v15.i3.90

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver 2012; 6(2):172–187. doi:10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172

- Lee JY, Keane MG, Pereira S. Diagnosis and treatment of gallstone disease. Practitioner 2015; 259(1783):15–19.

- Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, et al. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(5):1448–1453. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.025

- Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and upper gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(2):376–386. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.015

- Cariati A. Gallstone classification in Western countries. Indian J Surg 2015; 77(suppl 2):376–380. doi.org/10.1007/s12262-013-0847-y

- Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):410–419. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80932-8

- Lammert F, Gurusamy K, Ko CW, et al. Gallstones. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16024. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.24

- Stewart L, Oesterle AL, Erdan I, Griffiss JM, Way LW. Pathogenesis of pigment gallstones in Western societies: the central role of bacteria. J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6(6):891–904.

- Barbara L, Sama C, Morselli Labate AM, et al. A population study on the prevalence of gallstone disease: the Sirmione Study. Hepatology 1987; 7(5):913–917. doi:10.1002/hep.1840070520

- Sood S, Winn T, Ibrahim S, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic gallstones: differential behaviour in male and female subjects. Med J Malaysia 2015; 70(6):341–345.

- Maringhini A, Ciambra M, Baccelliere P, et al. Biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnancy: incidence, risk factors, and natural history. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119(2):116–120. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00004

- Etminan M, Delaney JA, Bressler B, Brophy JM. Oral contraceptives and the risk of gallbladder disease: a comparative safety study. CMAJ 2011; 183(8):899–904. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110161

- Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 1999; 117(3):632–639.

- Festi D, Sottili S, Colecchia A, et al. Clinical manifestations of gallstone disease: evidence from the multicenter Italian study on cholelithiasis (MICOL). Hepatology 1999; 30(4):839–846. doi:10.1002/hep.510300401

- Berhane T, Vetrhus M, Hausken T, Olafsson S, Sondenaa K. Pain attacks in non-complicated and complicated gallstone disease have a characteristic pattern and are accompanied by dyspepsia in most patients: the results of a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41(1):93–101. doi:10.1080/00365520510023990

- Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Tyor MP, Hersh T. The natural history of cholelithiasis: the National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(2):171–175. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-101-2-171

- Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):399–404. doi:0.1016/S0002-9610(05)80930-4

- Friedman GD, Raviola CA, Fireman B. Prognosis of gallstones with mild or no symptoms: 25 years of follow-up in a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42(2):127–136. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90086-3

- Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):78–82. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1159-4

- Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):27–34. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1153-x

- Koo KP, Traverso LW. Do preoperative indicators predict the presence of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg 1996; 171(5):495–499. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89611-0

- Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg 2004; 239(1):28–33. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000103069.00170.9c

- Costi R, Gnocchi A, Di Mario F, Sarli L. Diagnosis and management of choledocholithiasis in the golden age of imaging, endoscopy and laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(37):13382–13401. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13382

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol 2016; 65(1):146–181. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.005

- Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg 2016; 59 (2):128–140. doi:10.1503/cjs.015015

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1400–1416. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218

- Moolla Z, Anderson F, Thomson SR. Use of amylase and alanine transaminase to predict acute gallstone pancreatitis in a population with high HIV prevalence. World J Surg 2013; 37(1):156–161. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1801-z

- Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154(22):2573–2581. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420220069008

- Kiewiet JJ, Leeuwenburgh MM, Bipat S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of imaging in acute cholecystitis. Radiology 2012; 264(3):708–720. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111561

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.041

- Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med 2003; 22(9):879–885. doi:10.7863/jum.2003.22.9.879

- El-Hayek K, Timratana P, Meranda J, Shimizu H, Eldar S, Chand B. Post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass biliary dilation: natural process or significant entity? J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16(12):2185–2189. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-2058-4

- Park SM, Kim WS, Bae IH, et al. Common bile duct dilatation after cholecystectomy: a one-year prospective study. J Korean Surg Soc 2012; 83(2):97–101. doi:10.4174/jkss.2012.83.2.97

- Tse F, Liu L, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Moayyedi P. EUS: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67(2):235–244. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.047

- Verma D, Kapadia A, Eisen GM, Adler DG. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64(2):248–254. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.038

- Tseng LJ, Jao YT, Mo LR, Lin RC. Over-the-wire US catheter probe as an adjunct to ERCP in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54(6):720–723. doi:10.1067/mge.2001.119255

- Kondo S, Isayama H, Akahane M, et al. Detection of common bile duct stones: comparison between endoscopic ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiography, and helical-computed-tomographic cholangiography. Eur J Radiol 2005; 54(2):271–275. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.07.007

- Attili AF, De Santis A, Capri R, Repice AM, Maselli S. The natural history of gallstones: the GREPCO experience. The GREPCO Group. Hepatology 1995; 21(3):656–660. doi:10.1016/0270-9139(95)90514-6

- Sakorafas GH, Milingos D, Peros G. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis: is cholecystectomy really needed? A critical reappraisal 15 years after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52(5):1313–1325. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9107-3

- Gracie WA, Ransohoff DF. The natural history of silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med 1982; 307(13):798–800. doi:10.1056/NEJM198209233071305

- McSherry CK, Ferstenberg H, Calhoun WF, Lahman E, Virshup M. The natural history of diagnosed gallstone disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ann Surg 1985; 202(1):59–63. doi:10.1097/00000658-198507000-00009

- Wada K, Wada K, Imamura T. Natural course of asymptomatic gallstone disease. Nihon Rinsho 1993; 51(7):1737–1743. Japanese.

- Halldestam I, Enell EL, Kullman E, Borch K. Development of symptoms and complications in individuals with asymptomatic gallstones. Br J Surg 2004; 91(6):734–738. doi:10.1002/bjs.4547

- Festi D, Reggiani ML, Attili AF, et al. Natural history of gallstone disease: expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(4):719–724. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06146.x

- Shabanzadeh DM, Sorensen LT, Jorgensen T. A prediction rule for risk stratification of incidentally discovered gallstones: results from a large cohort study. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(1):156–167e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.002

- Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, Fanelli R; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc 2010; 24(10):2368–2386. doi:10.1007/s00464-010-1268-7

- Abraham S, Rivero HG, Erlikh IV, Griffith LF, Kondamudi VK. Surgical and nonsurgical management of gallstones. Am Fam Physician 2014; 89(10):795–802.

- Currò G,, Iapichino G, Lorenzini C, Palmeri R, Cucinotta E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children with chronic hemolytic anemia. Is the outcome related to the timing of the procedure? Surg Endosc 2006; 20(2):252–255. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0318-z

- Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6:99–109. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S37357

- Chen GL, Akmal Y, DiFronzo AL, Vuong B, O’Connor V. Porcelain gallbladder: no longer an indication for prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am Surg 2015; 81(10):936–940.

- Schnelldorfer T. Porcelain gallbladder: a benign process or concern for malignancy? J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17(6):1161–1168. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2170-0

- Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, et al. Concomitant cholecystectomy during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese patients is not justified: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2013; 23(3)3979–408. doi:10.1007/s11695-012-0852-4

- Gurusamy K, Samraj K, Gluud C, Wilson E, Davidson BR. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 2010; 97(2):141–150. doi:10.1002/bjs.6870

- Papi C, Catarci M, D’Ambrosio L, et al. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99(1):147–155. doi:10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04002.x

- Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD005440. doi:10.1002/14651858

- Menahem B, Mulliri A, Fohlen A, Guittet L, Alves A, Lubrano J. Delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy increases the total hospital stay compared to an early laparoscopic cholecystectomy after acute cholecystitis: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17(10):857–862. doi:10.1111/hpb.12449

- Uhl W, Müller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid SW, Schölzel S, Büchler MW. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc 1999; 13(11):1070–1076. doi:10.1007/s004649901175

- Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg 2010(4): 251:615–619. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c38f1f

The prevalence of gallstones is approximately 10% to 15% of the adult US population.1,2 Most cases are asymptomatic, as gallstones are usually discovered incidentally during routine imaging for other abdominal conditions, and only about 20% of patients with asymptomatic gallstones develop clinically significant complications.2,3

Nevertheless, gallstones carry significant healthcare costs. In 2004, the median inpatient cost for any gallstone-related disease was $11,584, with an overall annual cost of $6.2 billion.4,5

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard treatment for symptomatic cholelithiasis. For asymptomatic cholelithasis, the usual approach is expectant management (“watch and wait”), but prophylactic cholecystectomy may be an option in certain patients at high risk.

CHEMICAL COMPOSITION

Gallstones can be classified into 2 main categories based on their predominant chemical composition: cholesterol or pigment.

Cholesterol gallstones

About 75% of gallstones are composed of cholesterol.3,4 In the past, this type of stone was thought to be caused by gallbladder inflammation, bile stasis, and absorption of bile salts from damaged mucosa. However, it is now known that cholesterol gallstones are the result of biliary supersaturation caused by cholesterol hypersecretion into the gallbladder, gallbladder hypomotility, accelerated cholesterol nucleation and crystallization, and mucin gel accumulation.

Pigment gallstones

Black pigment gallstones account for 10% to 15% of all gallstones.6 They are caused by chronic hemolysis in association with supersaturation of bile with calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, along with deposition of calcium carbonate, phosphate, and inorganic salts.7

Brown pigment stones, accounting for 5% to 10% of all gallstones,6 are caused by infection in the obstructed bile ducts, where bacteria that produce beta-glucuronidase, phospholipase, and slime contribute to formation of the stone.8,9

RISK FACTORS FOR GALLSTONES

Age. After age 40, the risk increases dramatically, with an incidence 4 times higher for those ages 40 to 69 than in younger people.10

Female sex. Women of reproductive age are 4 times more likely to develop gallstones than men, but this gap narrows after menopause.11 The higher risk is attributed to female sex hormones, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Estrogen decreases secretion of bile salts and increases secretion of cholesterol into the gallbladder, which leads to cholesterol supersaturation. Progesterone acts synergistically by causing hypomobility of the gallbladder, which in turn leads to bile stasis.12,13

Ethnicity. The risk is higher in Mexican Americans and Native Americans than in other ethnic groups.14

Rapid weight loss, such as after bariatric surgery, occurs from decreased caloric intake and promotes bile stasis, while lipolysis increases cholesterol mobilization and secretion into the gallbladder. This creates an environment conducive to bile supersaturation with cholesterol, leading to gallstone formation.

Chronic hemolytic disorders carry an increased risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones due to increased excretion of bilirubin during hemolysis.

Obesity and diabetes mellitus are both attributed to insulin resistance. Obesity also increases bile stasis and cholesterol saturation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GALLSTONES (CHOLELITHIASIS)

Most patients with gallstones (cholelithiasis) experience no symptoms. Their gallstones are often discovered incidentally during imaging tests for unrelated or unexplained abdominal symptoms. Most patients with asymptomatic gallstones remain symptom-free, while about 20% develop gallstone-related symptoms.2,3

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom. The phrase biliary colic—suggesting pain that is fluctuating in nature—appears ubiquitously in the medical literature, but it does not correctly characterize the pain associated with gallstones.

Most patients with gallstone symptoms describe a constant and often severe pain in the right upper abdomen, epigastrium, or both, often persisting for 30 to 120 minutes. Symptoms are frequently reported in the epigastrium when only visceral pain fibers are stimulated due to gallbladder distention. This is usually called midline pain; however, pain occurs in the back and right shoulder in up to 60% of patients, with involvement of somatic fibers.15,16 Gallstone pain is not relieved by change of position or passage of stool or gas.

Onset of symptoms more than an hour after eating or in the late evening or at night also very strongly suggests biliary pain. Patients with a history of biliary pain are more likely to experience it again, with a 69% chance of developing recurrent pain within 2 years.17

GALLSTONE-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Acute gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis)

Gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) is the most common complication, occurring in up to 10% of symptomatic cases. Many patients with acute cholecystitis present with right upper quadrant pain that may be accompanied by anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Inspiratory arrest on deep palpation of the right upper quadrant (Murphy sign) has a specificity of 79% to 96% for acute cholecystitis.20 Markers of systemic inflammation such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, and elevated C-reactive protein are highly suggestive of acute cholecystitis.20,21

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis)

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis) are detected in 3.4% to 12% of patients with gallstones.22,23 Most stones in the common bile duct migrate there from the gallbladder via the cystic duct. Less commonly, primary duct stones form in the duct due to biliary stasis. Removing the gallbladder does not completely eliminate the risk of bile duct stones, as stones can remain or recur after surgery.

Bile duct stones can obstruct the common bile duct, which disrupts normal bile flow and leads to jaundice. Other symptoms may include pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting. Serum levels of bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase are usually high.24

Acute bacterial infection (cholangitis)

Acute bacterial infection of the biliary system (cholangitis) is usually associated with obstruction of the common bile duct. Common symptoms of acute cholangitis include right upper quadrant pain, fever, and jaundice (Charcot triad), and these are present in about 50% to 75% of cases.21 In severe cases, patients can develop altered mental status and septicemic shock in addition to the Charcot triad, a condition called the Reynold pentad. White blood cell counts and serum levels of C-reactive protein, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and alkaline phosphatase are usually elevated.21

Pancreatitis

Approximately 4% to 8% of patients with gallstones develop inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).25 The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least 2 of the following:26,27

- Abdominal pain (typically epigastric, often radiating to the back)

- Amylase or lipase levels at least 3 times above the normal limit

- Imaging findings that suggest acute pancreatitis.

Gallstone-related pancreatitis should be considered if the ALT level is greater than 150 U/mL, which has a 97% specificity for gallstone-related pancreatitis.28

ABDOMINAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY FOR DIAGNOSIS

Transabdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of 84% to 89% and a specificity of up to 99%, is the test of choice for detecting gallstones.29 The characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis on ultrasonography include enlargement of the gallbladder, thickening of the gallbladder wall, presence of pericholecystic fluid, and tenderness elicited by the ultrasound probe over the gallbladder (sonographic Murphy sign).

Scintigraphy as a second test

Acute cholecystitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis and typically does not require additional imaging beyond ultrasonography. When there is discordance between clinical and ultrasonographic findings, the most accurate second imaging test is scintigraphy of the biliary tract, usually performed with technetium-labeled hydroxy iminodiacetic acid. Given intravenously, the radionuclide is rapidly taken up by the liver and then secreted into the bile. In acute cholecystitis, the cystic duct is functionally occluded and the isotope does not enter the gallbladder, creating an imaging void compared with a normal appearance.

Scintigraphy is more sensitive than abdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of up to 97% vs 81% to 88%, respectively.29,30 The tests have about equal specificity.

Even though scintigraphy is more sensitive, abdominal ultrasonography is often the initial test for patients with suspected acute cholecystitis because it is more widely available, takes less time, does not involve radiation exposure, and can assess for the presence or absence of gallstones and dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts.

Looking for stones in the common bile duct

When acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography is a prudent initial test to look for gallstones or biliary dilation suggesting obstruction by stones in the common bile duct. Abdominal ultrasonography has only a 22% to 55% sensitivity for visualizing stones in the common bile duct, but it has a 77% to 87% sensitivity for detecting common bile duct dilation, a surrogate marker of stones.31

The normal bile duct diameter ranges from 3 to 6 mm, although mild dilation is often seen in older patients or after cholecystectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.32,33 Bile duct dilation of up to 10 mm can be considered normal in patients after cholecystectomy.34 A normal-appearing bile duct on ultrasonography has a negative predictive value of 95% for excluding common bile duct stones.31

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have similar sensitivity (89%–94%, 85%–92%, and 89%–93%, respectively) and specificity (94%–95%, 93%–97%, and 100%, respectively) for detecting common bile duct stones.35–37 EUS is superior to MRCP in detecting stones smaller than 6 mm.38

ERCP should be reserved for managing rather than diagnosing common bile duct stones because of the risk of pancreatitis and perforation. Patients undergoing cholecystectomy who are suspected of having choledocholithiasis may undergo intraoperative cholangiography or laparoscopic common bile duct ultrasonography.

WATCH AND WAIT, OR INTERVENE?

Asymptomatic gallstones

Standard treatment for these patients is expectant management. Cholecystectomy is not recommended for patients with asymptomatic gallstones.47 Nevertheless, some patients may benefit from prophylactic cholecystectomy. We and others48 suggest considering cholecystectomy in the following patients.

Patients with chronic hemolytic anemia (including children with sickle cell anemia and spherocytosis). These patients have a higher risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones, and cholecystectomy has improved outcomes.49 It should be noted that most of these data come from pediatric populations and have been extrapolated to adults.

Native Americans, who have a higher risk of gallbladder cancer if they have gallstones.2,50

Conversely, calcification of the gallbladder wall (“porcelain gallbladder”) is no longer considered an absolute indication for cholecystectomy. This condition was thought to be associated with a high rate of gallbladder carcinoma, but analyses of larger, more recent data sets found much smaller risks.51,52 Further, cholecystectomy in these patients was found to be associated with high rates of postoperative complications. Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy is no longer recommended in asymptomatic cases of porcelain gallbladder.

In addition, concomitant cholecystectomy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery is no longer considered the therapeutic standard. Historically, cholecystectomy was performed in these patients because of the increased risk of gallstones associated with rapid weight loss after surgery. However, research now weighs against concomitant cholecystectomy with bariatric surgery and most other abdominal surgeries for asymptomatic gallstones.53

Laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic gallstones

For patients experiencing acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.48 There were safety concerns regarding higher rates of morbidity and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy in patients who underwent surgery before the acute cholecystitis episode had settled. However, a large meta-analysis found no significant difference between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in bile duct injury or conversion rates.54 Further, early cholecystectomy—defined as within 1 week of symptom onset—has been found to reduce gallstone-related complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower costs.55–57 If the patient cannot undergo surgery, percutaneous cholecystotomy or novel endoscopic gallbladder drainage interventions can be used.

Several variables predict the presence of bile duct stones in patients who have symptoms (Table 4). Based on these predictors, the ASGE classifies the probabilities as low (< 10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), and high (> 50%)31:

- High-risk patients should undergo preoperative ERCP and stone extraction if needed

- Intermediate-risk patients should undergo preoperative imaging with EUS or MRCP or intraoperative bile duct evaluation, depending on the availability, costs, and local expertise.

Patients with associated cholangitis should be given intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Biliary decompression should be done as early as possible to decrease the risk of morbidity and mortality. For acute cholangitis, ERCP is the treatment of choice.25

Patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis should receive conservative management with intravenous isotonic solutions and pain control, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.48

The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute gallstone pancreatitis has been debated. Studies conducted during the era of open cholecystectomy reported similar or worse outcomes if cholecystectomy was done sooner rather than later.

However, in 1999, Uhl et al58 reported that 48 of 77 patients admitted with acute gallstone pancreatitis were able to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same admission. Success rates were 85% (30 of 35 patients) in those with mild disease and 62% (8 of 13 patients) in those with severe disease. They concluded laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be safely performed within 7 days in patients with mild disease, whereas in severe disease at least 3 weeks should elapse because of the risk of infection.

In a randomized trial published in 2010, Aboulian et al59 reported that hospital length of stay (the primary end point) was shorter in 25 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy early (within 48 hours of admission) than in 25 patients who underwent surgery after abdominal pain had resolved and laboratory enzymes showed a normalizing trend, 3.5 vs 5.8 days (P = .0016). Rates of perioperative complications and need for conversion to open surgery were similar between the 2 groups.

If there is associated cholangitis, patients should also be given broad-spectrum antibiotics and should undergo ERCP within 24 hours of admission.25–27

SUMMARY

Gallstones are common in US adults. Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging test of choice to detect gallbladder stones and assess for findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis and dilation of the common bile duct. Fortunately, most gallstones are asymptomatic and can usually be managed expectantly. In patients who have symptoms or have gallstone complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard of care.

The prevalence of gallstones is approximately 10% to 15% of the adult US population.1,2 Most cases are asymptomatic, as gallstones are usually discovered incidentally during routine imaging for other abdominal conditions, and only about 20% of patients with asymptomatic gallstones develop clinically significant complications.2,3

Nevertheless, gallstones carry significant healthcare costs. In 2004, the median inpatient cost for any gallstone-related disease was $11,584, with an overall annual cost of $6.2 billion.4,5

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard treatment for symptomatic cholelithiasis. For asymptomatic cholelithasis, the usual approach is expectant management (“watch and wait”), but prophylactic cholecystectomy may be an option in certain patients at high risk.

CHEMICAL COMPOSITION

Gallstones can be classified into 2 main categories based on their predominant chemical composition: cholesterol or pigment.

Cholesterol gallstones

About 75% of gallstones are composed of cholesterol.3,4 In the past, this type of stone was thought to be caused by gallbladder inflammation, bile stasis, and absorption of bile salts from damaged mucosa. However, it is now known that cholesterol gallstones are the result of biliary supersaturation caused by cholesterol hypersecretion into the gallbladder, gallbladder hypomotility, accelerated cholesterol nucleation and crystallization, and mucin gel accumulation.

Pigment gallstones

Black pigment gallstones account for 10% to 15% of all gallstones.6 They are caused by chronic hemolysis in association with supersaturation of bile with calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, along with deposition of calcium carbonate, phosphate, and inorganic salts.7

Brown pigment stones, accounting for 5% to 10% of all gallstones,6 are caused by infection in the obstructed bile ducts, where bacteria that produce beta-glucuronidase, phospholipase, and slime contribute to formation of the stone.8,9

RISK FACTORS FOR GALLSTONES

Age. After age 40, the risk increases dramatically, with an incidence 4 times higher for those ages 40 to 69 than in younger people.10

Female sex. Women of reproductive age are 4 times more likely to develop gallstones than men, but this gap narrows after menopause.11 The higher risk is attributed to female sex hormones, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Estrogen decreases secretion of bile salts and increases secretion of cholesterol into the gallbladder, which leads to cholesterol supersaturation. Progesterone acts synergistically by causing hypomobility of the gallbladder, which in turn leads to bile stasis.12,13

Ethnicity. The risk is higher in Mexican Americans and Native Americans than in other ethnic groups.14

Rapid weight loss, such as after bariatric surgery, occurs from decreased caloric intake and promotes bile stasis, while lipolysis increases cholesterol mobilization and secretion into the gallbladder. This creates an environment conducive to bile supersaturation with cholesterol, leading to gallstone formation.

Chronic hemolytic disorders carry an increased risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones due to increased excretion of bilirubin during hemolysis.

Obesity and diabetes mellitus are both attributed to insulin resistance. Obesity also increases bile stasis and cholesterol saturation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GALLSTONES (CHOLELITHIASIS)

Most patients with gallstones (cholelithiasis) experience no symptoms. Their gallstones are often discovered incidentally during imaging tests for unrelated or unexplained abdominal symptoms. Most patients with asymptomatic gallstones remain symptom-free, while about 20% develop gallstone-related symptoms.2,3

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom. The phrase biliary colic—suggesting pain that is fluctuating in nature—appears ubiquitously in the medical literature, but it does not correctly characterize the pain associated with gallstones.

Most patients with gallstone symptoms describe a constant and often severe pain in the right upper abdomen, epigastrium, or both, often persisting for 30 to 120 minutes. Symptoms are frequently reported in the epigastrium when only visceral pain fibers are stimulated due to gallbladder distention. This is usually called midline pain; however, pain occurs in the back and right shoulder in up to 60% of patients, with involvement of somatic fibers.15,16 Gallstone pain is not relieved by change of position or passage of stool or gas.

Onset of symptoms more than an hour after eating or in the late evening or at night also very strongly suggests biliary pain. Patients with a history of biliary pain are more likely to experience it again, with a 69% chance of developing recurrent pain within 2 years.17

GALLSTONE-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Acute gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis)

Gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) is the most common complication, occurring in up to 10% of symptomatic cases. Many patients with acute cholecystitis present with right upper quadrant pain that may be accompanied by anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Inspiratory arrest on deep palpation of the right upper quadrant (Murphy sign) has a specificity of 79% to 96% for acute cholecystitis.20 Markers of systemic inflammation such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, and elevated C-reactive protein are highly suggestive of acute cholecystitis.20,21

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis)

Bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis) are detected in 3.4% to 12% of patients with gallstones.22,23 Most stones in the common bile duct migrate there from the gallbladder via the cystic duct. Less commonly, primary duct stones form in the duct due to biliary stasis. Removing the gallbladder does not completely eliminate the risk of bile duct stones, as stones can remain or recur after surgery.

Bile duct stones can obstruct the common bile duct, which disrupts normal bile flow and leads to jaundice. Other symptoms may include pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting. Serum levels of bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase are usually high.24

Acute bacterial infection (cholangitis)

Acute bacterial infection of the biliary system (cholangitis) is usually associated with obstruction of the common bile duct. Common symptoms of acute cholangitis include right upper quadrant pain, fever, and jaundice (Charcot triad), and these are present in about 50% to 75% of cases.21 In severe cases, patients can develop altered mental status and septicemic shock in addition to the Charcot triad, a condition called the Reynold pentad. White blood cell counts and serum levels of C-reactive protein, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and alkaline phosphatase are usually elevated.21

Pancreatitis

Approximately 4% to 8% of patients with gallstones develop inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).25 The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least 2 of the following:26,27

- Abdominal pain (typically epigastric, often radiating to the back)

- Amylase or lipase levels at least 3 times above the normal limit

- Imaging findings that suggest acute pancreatitis.

Gallstone-related pancreatitis should be considered if the ALT level is greater than 150 U/mL, which has a 97% specificity for gallstone-related pancreatitis.28

ABDOMINAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY FOR DIAGNOSIS

Transabdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of 84% to 89% and a specificity of up to 99%, is the test of choice for detecting gallstones.29 The characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis on ultrasonography include enlargement of the gallbladder, thickening of the gallbladder wall, presence of pericholecystic fluid, and tenderness elicited by the ultrasound probe over the gallbladder (sonographic Murphy sign).

Scintigraphy as a second test

Acute cholecystitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis and typically does not require additional imaging beyond ultrasonography. When there is discordance between clinical and ultrasonographic findings, the most accurate second imaging test is scintigraphy of the biliary tract, usually performed with technetium-labeled hydroxy iminodiacetic acid. Given intravenously, the radionuclide is rapidly taken up by the liver and then secreted into the bile. In acute cholecystitis, the cystic duct is functionally occluded and the isotope does not enter the gallbladder, creating an imaging void compared with a normal appearance.

Scintigraphy is more sensitive than abdominal ultrasonography, with a sensitivity of up to 97% vs 81% to 88%, respectively.29,30 The tests have about equal specificity.

Even though scintigraphy is more sensitive, abdominal ultrasonography is often the initial test for patients with suspected acute cholecystitis because it is more widely available, takes less time, does not involve radiation exposure, and can assess for the presence or absence of gallstones and dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts.

Looking for stones in the common bile duct

When acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography is a prudent initial test to look for gallstones or biliary dilation suggesting obstruction by stones in the common bile duct. Abdominal ultrasonography has only a 22% to 55% sensitivity for visualizing stones in the common bile duct, but it has a 77% to 87% sensitivity for detecting common bile duct dilation, a surrogate marker of stones.31

The normal bile duct diameter ranges from 3 to 6 mm, although mild dilation is often seen in older patients or after cholecystectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.32,33 Bile duct dilation of up to 10 mm can be considered normal in patients after cholecystectomy.34 A normal-appearing bile duct on ultrasonography has a negative predictive value of 95% for excluding common bile duct stones.31

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have similar sensitivity (89%–94%, 85%–92%, and 89%–93%, respectively) and specificity (94%–95%, 93%–97%, and 100%, respectively) for detecting common bile duct stones.35–37 EUS is superior to MRCP in detecting stones smaller than 6 mm.38

ERCP should be reserved for managing rather than diagnosing common bile duct stones because of the risk of pancreatitis and perforation. Patients undergoing cholecystectomy who are suspected of having choledocholithiasis may undergo intraoperative cholangiography or laparoscopic common bile duct ultrasonography.

WATCH AND WAIT, OR INTERVENE?

Asymptomatic gallstones

Standard treatment for these patients is expectant management. Cholecystectomy is not recommended for patients with asymptomatic gallstones.47 Nevertheless, some patients may benefit from prophylactic cholecystectomy. We and others48 suggest considering cholecystectomy in the following patients.

Patients with chronic hemolytic anemia (including children with sickle cell anemia and spherocytosis). These patients have a higher risk of developing calcium bilirubinate stones, and cholecystectomy has improved outcomes.49 It should be noted that most of these data come from pediatric populations and have been extrapolated to adults.

Native Americans, who have a higher risk of gallbladder cancer if they have gallstones.2,50

Conversely, calcification of the gallbladder wall (“porcelain gallbladder”) is no longer considered an absolute indication for cholecystectomy. This condition was thought to be associated with a high rate of gallbladder carcinoma, but analyses of larger, more recent data sets found much smaller risks.51,52 Further, cholecystectomy in these patients was found to be associated with high rates of postoperative complications. Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy is no longer recommended in asymptomatic cases of porcelain gallbladder.

In addition, concomitant cholecystectomy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery is no longer considered the therapeutic standard. Historically, cholecystectomy was performed in these patients because of the increased risk of gallstones associated with rapid weight loss after surgery. However, research now weighs against concomitant cholecystectomy with bariatric surgery and most other abdominal surgeries for asymptomatic gallstones.53

Laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic gallstones

For patients experiencing acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.48 There were safety concerns regarding higher rates of morbidity and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy in patients who underwent surgery before the acute cholecystitis episode had settled. However, a large meta-analysis found no significant difference between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in bile duct injury or conversion rates.54 Further, early cholecystectomy—defined as within 1 week of symptom onset—has been found to reduce gallstone-related complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower costs.55–57 If the patient cannot undergo surgery, percutaneous cholecystotomy or novel endoscopic gallbladder drainage interventions can be used.

Several variables predict the presence of bile duct stones in patients who have symptoms (Table 4). Based on these predictors, the ASGE classifies the probabilities as low (< 10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), and high (> 50%)31:

- High-risk patients should undergo preoperative ERCP and stone extraction if needed

- Intermediate-risk patients should undergo preoperative imaging with EUS or MRCP or intraoperative bile duct evaluation, depending on the availability, costs, and local expertise.

Patients with associated cholangitis should be given intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Biliary decompression should be done as early as possible to decrease the risk of morbidity and mortality. For acute cholangitis, ERCP is the treatment of choice.25

Patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis should receive conservative management with intravenous isotonic solutions and pain control, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.48

The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute gallstone pancreatitis has been debated. Studies conducted during the era of open cholecystectomy reported similar or worse outcomes if cholecystectomy was done sooner rather than later.

However, in 1999, Uhl et al58 reported that 48 of 77 patients admitted with acute gallstone pancreatitis were able to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same admission. Success rates were 85% (30 of 35 patients) in those with mild disease and 62% (8 of 13 patients) in those with severe disease. They concluded laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be safely performed within 7 days in patients with mild disease, whereas in severe disease at least 3 weeks should elapse because of the risk of infection.

In a randomized trial published in 2010, Aboulian et al59 reported that hospital length of stay (the primary end point) was shorter in 25 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy early (within 48 hours of admission) than in 25 patients who underwent surgery after abdominal pain had resolved and laboratory enzymes showed a normalizing trend, 3.5 vs 5.8 days (P = .0016). Rates of perioperative complications and need for conversion to open surgery were similar between the 2 groups.

If there is associated cholangitis, patients should also be given broad-spectrum antibiotics and should undergo ERCP within 24 hours of admission.25–27

SUMMARY

Gallstones are common in US adults. Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging test of choice to detect gallbladder stones and assess for findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis and dilation of the common bile duct. Fortunately, most gallstones are asymptomatic and can usually be managed expectantly. In patients who have symptoms or have gallstone complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard of care.

- Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2005; 15(3):329–338. doi:10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v15.i3.90

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver 2012; 6(2):172–187. doi:10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172

- Lee JY, Keane MG, Pereira S. Diagnosis and treatment of gallstone disease. Practitioner 2015; 259(1783):15–19.

- Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, et al. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(5):1448–1453. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.025

- Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and upper gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(2):376–386. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.015

- Cariati A. Gallstone classification in Western countries. Indian J Surg 2015; 77(suppl 2):376–380. doi.org/10.1007/s12262-013-0847-y

- Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):410–419. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80932-8

- Lammert F, Gurusamy K, Ko CW, et al. Gallstones. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16024. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.24

- Stewart L, Oesterle AL, Erdan I, Griffiss JM, Way LW. Pathogenesis of pigment gallstones in Western societies: the central role of bacteria. J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6(6):891–904.

- Barbara L, Sama C, Morselli Labate AM, et al. A population study on the prevalence of gallstone disease: the Sirmione Study. Hepatology 1987; 7(5):913–917. doi:10.1002/hep.1840070520

- Sood S, Winn T, Ibrahim S, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic gallstones: differential behaviour in male and female subjects. Med J Malaysia 2015; 70(6):341–345.

- Maringhini A, Ciambra M, Baccelliere P, et al. Biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnancy: incidence, risk factors, and natural history. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119(2):116–120. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00004

- Etminan M, Delaney JA, Bressler B, Brophy JM. Oral contraceptives and the risk of gallbladder disease: a comparative safety study. CMAJ 2011; 183(8):899–904. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110161

- Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 1999; 117(3):632–639.

- Festi D, Sottili S, Colecchia A, et al. Clinical manifestations of gallstone disease: evidence from the multicenter Italian study on cholelithiasis (MICOL). Hepatology 1999; 30(4):839–846. doi:10.1002/hep.510300401

- Berhane T, Vetrhus M, Hausken T, Olafsson S, Sondenaa K. Pain attacks in non-complicated and complicated gallstone disease have a characteristic pattern and are accompanied by dyspepsia in most patients: the results of a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41(1):93–101. doi:10.1080/00365520510023990

- Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Tyor MP, Hersh T. The natural history of cholelithiasis: the National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(2):171–175. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-101-2-171

- Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):399–404. doi:0.1016/S0002-9610(05)80930-4

- Friedman GD, Raviola CA, Fireman B. Prognosis of gallstones with mild or no symptoms: 25 years of follow-up in a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42(2):127–136. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90086-3

- Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):78–82. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1159-4

- Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):27–34. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1153-x

- Koo KP, Traverso LW. Do preoperative indicators predict the presence of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg 1996; 171(5):495–499. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89611-0

- Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg 2004; 239(1):28–33. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000103069.00170.9c

- Costi R, Gnocchi A, Di Mario F, Sarli L. Diagnosis and management of choledocholithiasis in the golden age of imaging, endoscopy and laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(37):13382–13401. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13382

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol 2016; 65(1):146–181. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.005

- Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg 2016; 59 (2):128–140. doi:10.1503/cjs.015015

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1400–1416. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218

- Moolla Z, Anderson F, Thomson SR. Use of amylase and alanine transaminase to predict acute gallstone pancreatitis in a population with high HIV prevalence. World J Surg 2013; 37(1):156–161. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1801-z

- Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154(22):2573–2581. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420220069008

- Kiewiet JJ, Leeuwenburgh MM, Bipat S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of imaging in acute cholecystitis. Radiology 2012; 264(3):708–720. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111561

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.041

- Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med 2003; 22(9):879–885. doi:10.7863/jum.2003.22.9.879

- El-Hayek K, Timratana P, Meranda J, Shimizu H, Eldar S, Chand B. Post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass biliary dilation: natural process or significant entity? J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16(12):2185–2189. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-2058-4

- Park SM, Kim WS, Bae IH, et al. Common bile duct dilatation after cholecystectomy: a one-year prospective study. J Korean Surg Soc 2012; 83(2):97–101. doi:10.4174/jkss.2012.83.2.97

- Tse F, Liu L, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Moayyedi P. EUS: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67(2):235–244. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.047

- Verma D, Kapadia A, Eisen GM, Adler DG. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64(2):248–254. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.038

- Tseng LJ, Jao YT, Mo LR, Lin RC. Over-the-wire US catheter probe as an adjunct to ERCP in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54(6):720–723. doi:10.1067/mge.2001.119255

- Kondo S, Isayama H, Akahane M, et al. Detection of common bile duct stones: comparison between endoscopic ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiography, and helical-computed-tomographic cholangiography. Eur J Radiol 2005; 54(2):271–275. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.07.007

- Attili AF, De Santis A, Capri R, Repice AM, Maselli S. The natural history of gallstones: the GREPCO experience. The GREPCO Group. Hepatology 1995; 21(3):656–660. doi:10.1016/0270-9139(95)90514-6

- Sakorafas GH, Milingos D, Peros G. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis: is cholecystectomy really needed? A critical reappraisal 15 years after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52(5):1313–1325. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9107-3

- Gracie WA, Ransohoff DF. The natural history of silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med 1982; 307(13):798–800. doi:10.1056/NEJM198209233071305

- McSherry CK, Ferstenberg H, Calhoun WF, Lahman E, Virshup M. The natural history of diagnosed gallstone disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ann Surg 1985; 202(1):59–63. doi:10.1097/00000658-198507000-00009

- Wada K, Wada K, Imamura T. Natural course of asymptomatic gallstone disease. Nihon Rinsho 1993; 51(7):1737–1743. Japanese.

- Halldestam I, Enell EL, Kullman E, Borch K. Development of symptoms and complications in individuals with asymptomatic gallstones. Br J Surg 2004; 91(6):734–738. doi:10.1002/bjs.4547

- Festi D, Reggiani ML, Attili AF, et al. Natural history of gallstone disease: expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(4):719–724. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06146.x

- Shabanzadeh DM, Sorensen LT, Jorgensen T. A prediction rule for risk stratification of incidentally discovered gallstones: results from a large cohort study. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(1):156–167e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.002

- Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, Fanelli R; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc 2010; 24(10):2368–2386. doi:10.1007/s00464-010-1268-7

- Abraham S, Rivero HG, Erlikh IV, Griffith LF, Kondamudi VK. Surgical and nonsurgical management of gallstones. Am Fam Physician 2014; 89(10):795–802.

- Currò G,, Iapichino G, Lorenzini C, Palmeri R, Cucinotta E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children with chronic hemolytic anemia. Is the outcome related to the timing of the procedure? Surg Endosc 2006; 20(2):252–255. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0318-z

- Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6:99–109. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S37357

- Chen GL, Akmal Y, DiFronzo AL, Vuong B, O’Connor V. Porcelain gallbladder: no longer an indication for prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am Surg 2015; 81(10):936–940.

- Schnelldorfer T. Porcelain gallbladder: a benign process or concern for malignancy? J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17(6):1161–1168. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2170-0

- Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, et al. Concomitant cholecystectomy during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese patients is not justified: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2013; 23(3)3979–408. doi:10.1007/s11695-012-0852-4

- Gurusamy K, Samraj K, Gluud C, Wilson E, Davidson BR. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 2010; 97(2):141–150. doi:10.1002/bjs.6870

- Papi C, Catarci M, D’Ambrosio L, et al. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99(1):147–155. doi:10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04002.x

- Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD005440. doi:10.1002/14651858

- Menahem B, Mulliri A, Fohlen A, Guittet L, Alves A, Lubrano J. Delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy increases the total hospital stay compared to an early laparoscopic cholecystectomy after acute cholecystitis: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17(10):857–862. doi:10.1111/hpb.12449

- Uhl W, Müller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid SW, Schölzel S, Büchler MW. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc 1999; 13(11):1070–1076. doi:10.1007/s004649901175

- Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg 2010(4): 251:615–619. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c38f1f

- Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2005; 15(3):329–338. doi:10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v15.i3.90

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver 2012; 6(2):172–187. doi:10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172

- Lee JY, Keane MG, Pereira S. Diagnosis and treatment of gallstone disease. Practitioner 2015; 259(1783):15–19.

- Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, et al. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(5):1448–1453. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.025

- Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and upper gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(2):376–386. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.015

- Cariati A. Gallstone classification in Western countries. Indian J Surg 2015; 77(suppl 2):376–380. doi.org/10.1007/s12262-013-0847-y

- Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):410–419. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80932-8

- Lammert F, Gurusamy K, Ko CW, et al. Gallstones. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16024. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.24

- Stewart L, Oesterle AL, Erdan I, Griffiss JM, Way LW. Pathogenesis of pigment gallstones in Western societies: the central role of bacteria. J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6(6):891–904.

- Barbara L, Sama C, Morselli Labate AM, et al. A population study on the prevalence of gallstone disease: the Sirmione Study. Hepatology 1987; 7(5):913–917. doi:10.1002/hep.1840070520

- Sood S, Winn T, Ibrahim S, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic gallstones: differential behaviour in male and female subjects. Med J Malaysia 2015; 70(6):341–345.

- Maringhini A, Ciambra M, Baccelliere P, et al. Biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnancy: incidence, risk factors, and natural history. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119(2):116–120. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00004

- Etminan M, Delaney JA, Bressler B, Brophy JM. Oral contraceptives and the risk of gallbladder disease: a comparative safety study. CMAJ 2011; 183(8):899–904. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110161

- Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 1999; 117(3):632–639.

- Festi D, Sottili S, Colecchia A, et al. Clinical manifestations of gallstone disease: evidence from the multicenter Italian study on cholelithiasis (MICOL). Hepatology 1999; 30(4):839–846. doi:10.1002/hep.510300401

- Berhane T, Vetrhus M, Hausken T, Olafsson S, Sondenaa K. Pain attacks in non-complicated and complicated gallstone disease have a characteristic pattern and are accompanied by dyspepsia in most patients: the results of a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41(1):93–101. doi:10.1080/00365520510023990

- Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Tyor MP, Hersh T. The natural history of cholelithiasis: the National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(2):171–175. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-101-2-171

- Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg 1993; 165(4):399–404. doi:0.1016/S0002-9610(05)80930-4

- Friedman GD, Raviola CA, Fireman B. Prognosis of gallstones with mild or no symptoms: 25 years of follow-up in a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42(2):127–136. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90086-3

- Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):78–82. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1159-4

- Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14(1):27–34. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1153-x

- Koo KP, Traverso LW. Do preoperative indicators predict the presence of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg 1996; 171(5):495–499. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89611-0

- Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg 2004; 239(1):28–33. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000103069.00170.9c

- Costi R, Gnocchi A, Di Mario F, Sarli L. Diagnosis and management of choledocholithiasis in the golden age of imaging, endoscopy and laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(37):13382–13401. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13382

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol 2016; 65(1):146–181. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.005

- Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg 2016; 59 (2):128–140. doi:10.1503/cjs.015015

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1400–1416. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218

- Moolla Z, Anderson F, Thomson SR. Use of amylase and alanine transaminase to predict acute gallstone pancreatitis in a population with high HIV prevalence. World J Surg 2013; 37(1):156–161. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1801-z

- Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154(22):2573–2581. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420220069008

- Kiewiet JJ, Leeuwenburgh MM, Bipat S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of imaging in acute cholecystitis. Radiology 2012; 264(3):708–720. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111561

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.041

- Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med 2003; 22(9):879–885. doi:10.7863/jum.2003.22.9.879

- El-Hayek K, Timratana P, Meranda J, Shimizu H, Eldar S, Chand B. Post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass biliary dilation: natural process or significant entity? J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16(12):2185–2189. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-2058-4

- Park SM, Kim WS, Bae IH, et al. Common bile duct dilatation after cholecystectomy: a one-year prospective study. J Korean Surg Soc 2012; 83(2):97–101. doi:10.4174/jkss.2012.83.2.97