User login

Boosting Alzheimer’s trial participation via Medicare Advantage ‘memory fitness programs’

Clinical trials represent future hope for patients seeking better care, and there is no disease more in need of better care than Alzheimer’s disease. While death rates among most cancers, as well as heart disease, HIV-related illness, and other categories, have declined in the past decade, there has been no progress for Alzheimer’s disease. Better health and wellness overall may be having a beneficial effect that has produced a reduction in age-adjusted dementia rates, but with the aging of the population there are a greater absolute number of dementia cases than ever before, and that number is expected to continue rising. Finding a disease-modifying therapy seems to be the best hope for changing this dim outlook. Clinical trials intend to do just that but are hampered by patient enrollment rates that remain low. Far fewer eligible patients enroll than are needed, causing studies to take longer to complete, driving up their costs and essentially slowing progress. There is a need to increase patient enrollment, and there has been a variety of efforts intended to address this, not the least of which has been an explosion of media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Global Alzheimer’s Platform (GAP) Foundation, a nonprofit, self-described patient-centric entity dedicated to reducing the time and cost of Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, recently announced an initiative to increase participation in Alzheimer’s clinical trials by supporting and collaborating with “memory fitness programs” through select Medicare Advantage plans. At worst, this seems a harmless way to increase attention and hopefully interest in clinical trial participation. At best, this may be a cost-effective way to increase enrollment and even improve dementia care. Dementia is notoriously underdiagnosed, especially by overworked, busy primary care providers who simply lack the time to perform the time-consuming testing that is typically required to diagnose and follow such patients.

There are some caveats to consider. First, memory fitness programs are of dubious benefit. They generally fit the description of being harmless, but there is little compelling evidence that they preserve or improve memory.

Second, enrollment in a clinical trial, for a patient, is not always a winning proposition. To date, there has been little success and in the absence of benefit, any downside – even if simply an inconvenience – is a net negative. Recently at the 2018 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, Merck reported that patients with mild cognitive impairment receiving active treatment in the BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat trial actually declined at a more rapid rate than did those on placebo. While the absolute difference was small, and one could argue whether it was clinically significant or simply a random occurrence, it was a reminder that intervention with an experimental agent is not necessarily benign.

Third, Medicare Advantage plans, while popular in some circles, are not considered advantageous to providers so that the proliferation of inadequate reimbursement will potentially fuel the accelerating number of providers who opt out of insurance plans altogether. This is not necessarily an issue for the GAP Foundation specifically but is nonetheless an issue for anything that promotes MA plans).

Finally, it remains important to help patients and families maintain a positive outlook, especially when we have nothing better to offer. Alzheimer’s disease is not a death sentence for every patient affected. While many have difficult and heartbreaking courses, some have slowly progressive courses with relatively little impairment for an extended period of time. There are also the dementia-phobic, cognitively unimpaired individuals (or who simply have normal age-associated cognitive changes) in whom the continued drumbeat of dementia awareness and memory testing raises their paranoia ever higher. We treat deficits (or try to), but we have to live based on our preserved skills. The challenge clinicians must face with patients and families is how to maximize function while compensating for deficits and making sure that patients and families maintain their hope.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Clinical trials represent future hope for patients seeking better care, and there is no disease more in need of better care than Alzheimer’s disease. While death rates among most cancers, as well as heart disease, HIV-related illness, and other categories, have declined in the past decade, there has been no progress for Alzheimer’s disease. Better health and wellness overall may be having a beneficial effect that has produced a reduction in age-adjusted dementia rates, but with the aging of the population there are a greater absolute number of dementia cases than ever before, and that number is expected to continue rising. Finding a disease-modifying therapy seems to be the best hope for changing this dim outlook. Clinical trials intend to do just that but are hampered by patient enrollment rates that remain low. Far fewer eligible patients enroll than are needed, causing studies to take longer to complete, driving up their costs and essentially slowing progress. There is a need to increase patient enrollment, and there has been a variety of efforts intended to address this, not the least of which has been an explosion of media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Global Alzheimer’s Platform (GAP) Foundation, a nonprofit, self-described patient-centric entity dedicated to reducing the time and cost of Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, recently announced an initiative to increase participation in Alzheimer’s clinical trials by supporting and collaborating with “memory fitness programs” through select Medicare Advantage plans. At worst, this seems a harmless way to increase attention and hopefully interest in clinical trial participation. At best, this may be a cost-effective way to increase enrollment and even improve dementia care. Dementia is notoriously underdiagnosed, especially by overworked, busy primary care providers who simply lack the time to perform the time-consuming testing that is typically required to diagnose and follow such patients.

There are some caveats to consider. First, memory fitness programs are of dubious benefit. They generally fit the description of being harmless, but there is little compelling evidence that they preserve or improve memory.

Second, enrollment in a clinical trial, for a patient, is not always a winning proposition. To date, there has been little success and in the absence of benefit, any downside – even if simply an inconvenience – is a net negative. Recently at the 2018 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, Merck reported that patients with mild cognitive impairment receiving active treatment in the BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat trial actually declined at a more rapid rate than did those on placebo. While the absolute difference was small, and one could argue whether it was clinically significant or simply a random occurrence, it was a reminder that intervention with an experimental agent is not necessarily benign.

Third, Medicare Advantage plans, while popular in some circles, are not considered advantageous to providers so that the proliferation of inadequate reimbursement will potentially fuel the accelerating number of providers who opt out of insurance plans altogether. This is not necessarily an issue for the GAP Foundation specifically but is nonetheless an issue for anything that promotes MA plans).

Finally, it remains important to help patients and families maintain a positive outlook, especially when we have nothing better to offer. Alzheimer’s disease is not a death sentence for every patient affected. While many have difficult and heartbreaking courses, some have slowly progressive courses with relatively little impairment for an extended period of time. There are also the dementia-phobic, cognitively unimpaired individuals (or who simply have normal age-associated cognitive changes) in whom the continued drumbeat of dementia awareness and memory testing raises their paranoia ever higher. We treat deficits (or try to), but we have to live based on our preserved skills. The challenge clinicians must face with patients and families is how to maximize function while compensating for deficits and making sure that patients and families maintain their hope.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Clinical trials represent future hope for patients seeking better care, and there is no disease more in need of better care than Alzheimer’s disease. While death rates among most cancers, as well as heart disease, HIV-related illness, and other categories, have declined in the past decade, there has been no progress for Alzheimer’s disease. Better health and wellness overall may be having a beneficial effect that has produced a reduction in age-adjusted dementia rates, but with the aging of the population there are a greater absolute number of dementia cases than ever before, and that number is expected to continue rising. Finding a disease-modifying therapy seems to be the best hope for changing this dim outlook. Clinical trials intend to do just that but are hampered by patient enrollment rates that remain low. Far fewer eligible patients enroll than are needed, causing studies to take longer to complete, driving up their costs and essentially slowing progress. There is a need to increase patient enrollment, and there has been a variety of efforts intended to address this, not the least of which has been an explosion of media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Global Alzheimer’s Platform (GAP) Foundation, a nonprofit, self-described patient-centric entity dedicated to reducing the time and cost of Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, recently announced an initiative to increase participation in Alzheimer’s clinical trials by supporting and collaborating with “memory fitness programs” through select Medicare Advantage plans. At worst, this seems a harmless way to increase attention and hopefully interest in clinical trial participation. At best, this may be a cost-effective way to increase enrollment and even improve dementia care. Dementia is notoriously underdiagnosed, especially by overworked, busy primary care providers who simply lack the time to perform the time-consuming testing that is typically required to diagnose and follow such patients.

There are some caveats to consider. First, memory fitness programs are of dubious benefit. They generally fit the description of being harmless, but there is little compelling evidence that they preserve or improve memory.

Second, enrollment in a clinical trial, for a patient, is not always a winning proposition. To date, there has been little success and in the absence of benefit, any downside – even if simply an inconvenience – is a net negative. Recently at the 2018 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, Merck reported that patients with mild cognitive impairment receiving active treatment in the BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat trial actually declined at a more rapid rate than did those on placebo. While the absolute difference was small, and one could argue whether it was clinically significant or simply a random occurrence, it was a reminder that intervention with an experimental agent is not necessarily benign.

Third, Medicare Advantage plans, while popular in some circles, are not considered advantageous to providers so that the proliferation of inadequate reimbursement will potentially fuel the accelerating number of providers who opt out of insurance plans altogether. This is not necessarily an issue for the GAP Foundation specifically but is nonetheless an issue for anything that promotes MA plans).

Finally, it remains important to help patients and families maintain a positive outlook, especially when we have nothing better to offer. Alzheimer’s disease is not a death sentence for every patient affected. While many have difficult and heartbreaking courses, some have slowly progressive courses with relatively little impairment for an extended period of time. There are also the dementia-phobic, cognitively unimpaired individuals (or who simply have normal age-associated cognitive changes) in whom the continued drumbeat of dementia awareness and memory testing raises their paranoia ever higher. We treat deficits (or try to), but we have to live based on our preserved skills. The challenge clinicians must face with patients and families is how to maximize function while compensating for deficits and making sure that patients and families maintain their hope.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Minimizing use of antipsychotics

Prion-like transmission of neurodegenerative pathology stirs concern

Recent developments regarding the nature of transmissible pathologic proteins in a variety of common neurodegenerative diseases have started to cause clinicians and public health experts to wonder if there is cause for concern.

A group from the National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery at Queen Square, London, recently published a study presenting evidence that Alzheimer’s disease may have transmissible properties similar to traditionally regarded prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Nature. 2015 Sep 10;525:247-50. doi:10.1038/nature15369). This conclusion was based upon the observation of cerebral and vascular amyloid-beta deposition in several patients who had received cadaveric growth hormone extracts ranging from 19 to 39 years earlier and who developed iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Amyloid deposition was also identified in the pituitary glands of patients with amyloid-beta pathology also felt to be iatrogenically transmitted.

This is not the first time, however, that analogies have been drawn between neurodegenerative diseases and prion-related diseases. Perhaps inspired by the evident connectivity of affected upper and lower motor neuronal populations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, previous investigators have sought cell-to-cell transmission of neurodegenerative pathology and have demonstrated this for amyloid as well as tau species in Alzheimer’s disease, and for synuclein species in Parkinson’s disease.

A recent article by Dr. Stanley Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues presented evidence that brain extracts from patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA) transmitted the characteristic MSA alpha-synuclein aggregates in the brains of transgenic mice as well as in cultured human embryonic kidney cells (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514475112).

An emerging theme from these recent and prior studies is that neurodegenerative diseases behave a lot like prion diseases, and although they follow a much slower time course, may spread through synaptic pathways as well as between people through prion-like mechanisms. CJD, while transmissible, is not “contagious,” and public messaging should draw this distinction in regard to neurodegenerative diseases. Nonetheless, further research is urgently needed given the implications of this work. Dr. Prusiner and his associates concluded, for example, that deep brain stimulation electrodes and related equipment should not be reused from Parkinson’s disease patients for fear of spreading the synucleinopathy from one person to another. Should there be restrictions with regard to any form of tissue transplantation or blood transfusion from patients with Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease? Questions such as these need further clarification, and given the prevalence of these procedures, such research should be highly prioritized.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. He also serves there as associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Recent developments regarding the nature of transmissible pathologic proteins in a variety of common neurodegenerative diseases have started to cause clinicians and public health experts to wonder if there is cause for concern.

A group from the National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery at Queen Square, London, recently published a study presenting evidence that Alzheimer’s disease may have transmissible properties similar to traditionally regarded prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Nature. 2015 Sep 10;525:247-50. doi:10.1038/nature15369). This conclusion was based upon the observation of cerebral and vascular amyloid-beta deposition in several patients who had received cadaveric growth hormone extracts ranging from 19 to 39 years earlier and who developed iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Amyloid deposition was also identified in the pituitary glands of patients with amyloid-beta pathology also felt to be iatrogenically transmitted.

This is not the first time, however, that analogies have been drawn between neurodegenerative diseases and prion-related diseases. Perhaps inspired by the evident connectivity of affected upper and lower motor neuronal populations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, previous investigators have sought cell-to-cell transmission of neurodegenerative pathology and have demonstrated this for amyloid as well as tau species in Alzheimer’s disease, and for synuclein species in Parkinson’s disease.

A recent article by Dr. Stanley Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues presented evidence that brain extracts from patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA) transmitted the characteristic MSA alpha-synuclein aggregates in the brains of transgenic mice as well as in cultured human embryonic kidney cells (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514475112).

An emerging theme from these recent and prior studies is that neurodegenerative diseases behave a lot like prion diseases, and although they follow a much slower time course, may spread through synaptic pathways as well as between people through prion-like mechanisms. CJD, while transmissible, is not “contagious,” and public messaging should draw this distinction in regard to neurodegenerative diseases. Nonetheless, further research is urgently needed given the implications of this work. Dr. Prusiner and his associates concluded, for example, that deep brain stimulation electrodes and related equipment should not be reused from Parkinson’s disease patients for fear of spreading the synucleinopathy from one person to another. Should there be restrictions with regard to any form of tissue transplantation or blood transfusion from patients with Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease? Questions such as these need further clarification, and given the prevalence of these procedures, such research should be highly prioritized.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. He also serves there as associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Recent developments regarding the nature of transmissible pathologic proteins in a variety of common neurodegenerative diseases have started to cause clinicians and public health experts to wonder if there is cause for concern.

A group from the National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery at Queen Square, London, recently published a study presenting evidence that Alzheimer’s disease may have transmissible properties similar to traditionally regarded prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Nature. 2015 Sep 10;525:247-50. doi:10.1038/nature15369). This conclusion was based upon the observation of cerebral and vascular amyloid-beta deposition in several patients who had received cadaveric growth hormone extracts ranging from 19 to 39 years earlier and who developed iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Amyloid deposition was also identified in the pituitary glands of patients with amyloid-beta pathology also felt to be iatrogenically transmitted.

This is not the first time, however, that analogies have been drawn between neurodegenerative diseases and prion-related diseases. Perhaps inspired by the evident connectivity of affected upper and lower motor neuronal populations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, previous investigators have sought cell-to-cell transmission of neurodegenerative pathology and have demonstrated this for amyloid as well as tau species in Alzheimer’s disease, and for synuclein species in Parkinson’s disease.

A recent article by Dr. Stanley Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues presented evidence that brain extracts from patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA) transmitted the characteristic MSA alpha-synuclein aggregates in the brains of transgenic mice as well as in cultured human embryonic kidney cells (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514475112).

An emerging theme from these recent and prior studies is that neurodegenerative diseases behave a lot like prion diseases, and although they follow a much slower time course, may spread through synaptic pathways as well as between people through prion-like mechanisms. CJD, while transmissible, is not “contagious,” and public messaging should draw this distinction in regard to neurodegenerative diseases. Nonetheless, further research is urgently needed given the implications of this work. Dr. Prusiner and his associates concluded, for example, that deep brain stimulation electrodes and related equipment should not be reused from Parkinson’s disease patients for fear of spreading the synucleinopathy from one person to another. Should there be restrictions with regard to any form of tissue transplantation or blood transfusion from patients with Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease? Questions such as these need further clarification, and given the prevalence of these procedures, such research should be highly prioritized.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. He also serves there as associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Human brain mapping project begins to reveal roots of developmental abnormalities

Understanding the neurophysiologic and molecular bases of mental illness, autism, and related conditions remains one of the most challenging frontiers of medicine and neuroscience because despite very prominent symptoms, there is little that clinical diagnostic techniques reveal. The recent report of the BrainSpan Atlas represents a major collaborative attempt to map the human brain from its gestational developmental stages to its adult form (Nature 2014 April 2 [doi:10.1038/nature13185]). Previous work has examined the histology and transcriptomic profiles of 900 neuroanatomical subdivisions (Nature 2012;489:391-9) of two adult human brains that characterized the transcriptomic relationships between different cell types and different cell regions.

Now, based upon four prenatal brains, the atlas displays the gene expression profiles of the developing brain and reveals that many neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, have identifiable developmental abnormalities. To what degree these brains are representative of healthy preterm humans is not entirely clear, but the insights gained are remarkable and will certainly contribute importantly to our understanding of these most enigmatic conditions.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Understanding the neurophysiologic and molecular bases of mental illness, autism, and related conditions remains one of the most challenging frontiers of medicine and neuroscience because despite very prominent symptoms, there is little that clinical diagnostic techniques reveal. The recent report of the BrainSpan Atlas represents a major collaborative attempt to map the human brain from its gestational developmental stages to its adult form (Nature 2014 April 2 [doi:10.1038/nature13185]). Previous work has examined the histology and transcriptomic profiles of 900 neuroanatomical subdivisions (Nature 2012;489:391-9) of two adult human brains that characterized the transcriptomic relationships between different cell types and different cell regions.

Now, based upon four prenatal brains, the atlas displays the gene expression profiles of the developing brain and reveals that many neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, have identifiable developmental abnormalities. To what degree these brains are representative of healthy preterm humans is not entirely clear, but the insights gained are remarkable and will certainly contribute importantly to our understanding of these most enigmatic conditions.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Understanding the neurophysiologic and molecular bases of mental illness, autism, and related conditions remains one of the most challenging frontiers of medicine and neuroscience because despite very prominent symptoms, there is little that clinical diagnostic techniques reveal. The recent report of the BrainSpan Atlas represents a major collaborative attempt to map the human brain from its gestational developmental stages to its adult form (Nature 2014 April 2 [doi:10.1038/nature13185]). Previous work has examined the histology and transcriptomic profiles of 900 neuroanatomical subdivisions (Nature 2012;489:391-9) of two adult human brains that characterized the transcriptomic relationships between different cell types and different cell regions.

Now, based upon four prenatal brains, the atlas displays the gene expression profiles of the developing brain and reveals that many neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, have identifiable developmental abnormalities. To what degree these brains are representative of healthy preterm humans is not entirely clear, but the insights gained are remarkable and will certainly contribute importantly to our understanding of these most enigmatic conditions.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Redesign needed for Alzheimer’s screening programs

Advances in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis have led to the characterization of a preclinical stage, opening the door for therapeutic interventions designed to delay or even prevent the onset of symptomatic cognitive decline. Advocates for such a "pre-emptive strike" cite the ineffectiveness in symptomatic patients of seemingly well-conceived therapeutic trials using advanced biologic agents that are able to clear amyloid from the brain and yet fail to halt or even significantly slow clinical progression. A few prevention trials to date using agents such as Ginkgo biloba have unfortunately been unsuccessful, but the new trials, planned to begin enrollment in 2014, will be using monoclonal antibody–based agents with a demonstrated ability to clear amyloid, and will be targeted at genetically high-risk, presymptomatic individuals, particularly those with pathogenic autosomal dominant mutations (Biomark. Med. 2010;4:3-14) .

Although it seems clear why a presenilin 1 carrier might be willing to undergo such therapy, there are others who advocate widespread dementia screening programs so as to improve patient outcomes using existing therapies with the logic that earlier intervention must be best. A study presented by Dr. Carol Brayne at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference noted that the evidence showing beneficial clinical or psychosocial outcomes for population-based dementia screening is lacking. Screening programs have traditionally taken the form of simple mental status–styled tests, but a more recent development that has already become a thriving business involves genetic screening. The Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) study has shown that under carefully controlled conditions – including psychological screening, patient education, and follow-up – disclosure of apolipoprotein E allele status results can be done safely (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:245-54).

However, the paradigm followed by most who wish to pursue genetic testing is quite different. Interested individuals can simply go onto the websites of companies that offer genetic testing, purchase a DNA test kit, and receive their genetic results in the mail. This is not at all the model used by REVEAL, yet it is a rapidly growing practice.

People want predictive tests whether there is an immediate tangible impact on their health or not, and this seems true for a variety of conditions including, but not limited to, Alzheimer’s disease (Health Econ. 2012;21:238-51). There are a variety of reasons why such testing may be deemed valuable by participants, including a general dislike for uncertainty, greater insight into one’s health risks, nonmedical decision making, future planning, and, of course, actual disease prevention. To what degree people would use this information for making healthy lifestyle choices is at best unclear, and at worst discouraging.

Those who propose parallels between cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s development reason that control of risk factors for Alzheimer’s may prevent or at least delay the onset of symptoms, much like the control of CV risk factors may prevent or delay atherosclerosis-related complications, such as heart attack, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. The analogy is highly imperfect given the far greater correlation between CV risk factors with CV outcomes. Yet, in a cohort of 11,993 followed for more than 11 years, only 0.2% had all seven ideal metrics for CV health (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, healthy diet, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose). Ideal diet, for example, was met in only 4.2% (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:944-52). The level of noncompliance with proven, indisputable risk factors for the leading cause of death should at least raise concern that the public’s desire to know correlates very imperfectly with optimizing healthy behaviors, the primary point of predictive testing.

Another possible outcome of screening programs would be the identification of individuals eligible for research programs. Preclinical Alzheimer’s is a research construct, not a clinical diagnosis, and is primarily based upon biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in asymptomatic individuals. Group analyses leave little doubt that biomarker evidence of pathology correlates with future clinical outcomes (Ann. Neurol. 2012;71:765-75; Lancet Neurol. 2013 Sept. 4 [doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7]), but at the level of the individual (the clinical level), outcomes vary enough to make prognostication for any given patient unreliable. However, this should not invalidate preclinical Alzheimer’s as the research tool for which it was intended. Rather than declare a stalemate between those who advocate for and against preclinical testing, both sides undoubtedly agree that better therapies are needed, and preclinical Alzheimer’s, as a research construct, offers the opportunity to harness the current "free-for-all" state of genetic screening into a more thoughtfully designed and implemented program with the goal of pairing results with an action plan that, for some, could include participation in a therapeutic trial. What form such screening programs should take, how widespread they should be, and what rules should govern disclosure of results are all questions still in need of answers, but new research opportunities provide a compelling rationale to redesign rather than abandon screening programs.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Advances in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis have led to the characterization of a preclinical stage, opening the door for therapeutic interventions designed to delay or even prevent the onset of symptomatic cognitive decline. Advocates for such a "pre-emptive strike" cite the ineffectiveness in symptomatic patients of seemingly well-conceived therapeutic trials using advanced biologic agents that are able to clear amyloid from the brain and yet fail to halt or even significantly slow clinical progression. A few prevention trials to date using agents such as Ginkgo biloba have unfortunately been unsuccessful, but the new trials, planned to begin enrollment in 2014, will be using monoclonal antibody–based agents with a demonstrated ability to clear amyloid, and will be targeted at genetically high-risk, presymptomatic individuals, particularly those with pathogenic autosomal dominant mutations (Biomark. Med. 2010;4:3-14) .

Although it seems clear why a presenilin 1 carrier might be willing to undergo such therapy, there are others who advocate widespread dementia screening programs so as to improve patient outcomes using existing therapies with the logic that earlier intervention must be best. A study presented by Dr. Carol Brayne at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference noted that the evidence showing beneficial clinical or psychosocial outcomes for population-based dementia screening is lacking. Screening programs have traditionally taken the form of simple mental status–styled tests, but a more recent development that has already become a thriving business involves genetic screening. The Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) study has shown that under carefully controlled conditions – including psychological screening, patient education, and follow-up – disclosure of apolipoprotein E allele status results can be done safely (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:245-54).

However, the paradigm followed by most who wish to pursue genetic testing is quite different. Interested individuals can simply go onto the websites of companies that offer genetic testing, purchase a DNA test kit, and receive their genetic results in the mail. This is not at all the model used by REVEAL, yet it is a rapidly growing practice.

People want predictive tests whether there is an immediate tangible impact on their health or not, and this seems true for a variety of conditions including, but not limited to, Alzheimer’s disease (Health Econ. 2012;21:238-51). There are a variety of reasons why such testing may be deemed valuable by participants, including a general dislike for uncertainty, greater insight into one’s health risks, nonmedical decision making, future planning, and, of course, actual disease prevention. To what degree people would use this information for making healthy lifestyle choices is at best unclear, and at worst discouraging.

Those who propose parallels between cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s development reason that control of risk factors for Alzheimer’s may prevent or at least delay the onset of symptoms, much like the control of CV risk factors may prevent or delay atherosclerosis-related complications, such as heart attack, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. The analogy is highly imperfect given the far greater correlation between CV risk factors with CV outcomes. Yet, in a cohort of 11,993 followed for more than 11 years, only 0.2% had all seven ideal metrics for CV health (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, healthy diet, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose). Ideal diet, for example, was met in only 4.2% (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:944-52). The level of noncompliance with proven, indisputable risk factors for the leading cause of death should at least raise concern that the public’s desire to know correlates very imperfectly with optimizing healthy behaviors, the primary point of predictive testing.

Another possible outcome of screening programs would be the identification of individuals eligible for research programs. Preclinical Alzheimer’s is a research construct, not a clinical diagnosis, and is primarily based upon biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in asymptomatic individuals. Group analyses leave little doubt that biomarker evidence of pathology correlates with future clinical outcomes (Ann. Neurol. 2012;71:765-75; Lancet Neurol. 2013 Sept. 4 [doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7]), but at the level of the individual (the clinical level), outcomes vary enough to make prognostication for any given patient unreliable. However, this should not invalidate preclinical Alzheimer’s as the research tool for which it was intended. Rather than declare a stalemate between those who advocate for and against preclinical testing, both sides undoubtedly agree that better therapies are needed, and preclinical Alzheimer’s, as a research construct, offers the opportunity to harness the current "free-for-all" state of genetic screening into a more thoughtfully designed and implemented program with the goal of pairing results with an action plan that, for some, could include participation in a therapeutic trial. What form such screening programs should take, how widespread they should be, and what rules should govern disclosure of results are all questions still in need of answers, but new research opportunities provide a compelling rationale to redesign rather than abandon screening programs.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Advances in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis have led to the characterization of a preclinical stage, opening the door for therapeutic interventions designed to delay or even prevent the onset of symptomatic cognitive decline. Advocates for such a "pre-emptive strike" cite the ineffectiveness in symptomatic patients of seemingly well-conceived therapeutic trials using advanced biologic agents that are able to clear amyloid from the brain and yet fail to halt or even significantly slow clinical progression. A few prevention trials to date using agents such as Ginkgo biloba have unfortunately been unsuccessful, but the new trials, planned to begin enrollment in 2014, will be using monoclonal antibody–based agents with a demonstrated ability to clear amyloid, and will be targeted at genetically high-risk, presymptomatic individuals, particularly those with pathogenic autosomal dominant mutations (Biomark. Med. 2010;4:3-14) .

Although it seems clear why a presenilin 1 carrier might be willing to undergo such therapy, there are others who advocate widespread dementia screening programs so as to improve patient outcomes using existing therapies with the logic that earlier intervention must be best. A study presented by Dr. Carol Brayne at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference noted that the evidence showing beneficial clinical or psychosocial outcomes for population-based dementia screening is lacking. Screening programs have traditionally taken the form of simple mental status–styled tests, but a more recent development that has already become a thriving business involves genetic screening. The Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) study has shown that under carefully controlled conditions – including psychological screening, patient education, and follow-up – disclosure of apolipoprotein E allele status results can be done safely (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:245-54).

However, the paradigm followed by most who wish to pursue genetic testing is quite different. Interested individuals can simply go onto the websites of companies that offer genetic testing, purchase a DNA test kit, and receive their genetic results in the mail. This is not at all the model used by REVEAL, yet it is a rapidly growing practice.

People want predictive tests whether there is an immediate tangible impact on their health or not, and this seems true for a variety of conditions including, but not limited to, Alzheimer’s disease (Health Econ. 2012;21:238-51). There are a variety of reasons why such testing may be deemed valuable by participants, including a general dislike for uncertainty, greater insight into one’s health risks, nonmedical decision making, future planning, and, of course, actual disease prevention. To what degree people would use this information for making healthy lifestyle choices is at best unclear, and at worst discouraging.

Those who propose parallels between cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s development reason that control of risk factors for Alzheimer’s may prevent or at least delay the onset of symptoms, much like the control of CV risk factors may prevent or delay atherosclerosis-related complications, such as heart attack, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. The analogy is highly imperfect given the far greater correlation between CV risk factors with CV outcomes. Yet, in a cohort of 11,993 followed for more than 11 years, only 0.2% had all seven ideal metrics for CV health (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, healthy diet, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose). Ideal diet, for example, was met in only 4.2% (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:944-52). The level of noncompliance with proven, indisputable risk factors for the leading cause of death should at least raise concern that the public’s desire to know correlates very imperfectly with optimizing healthy behaviors, the primary point of predictive testing.

Another possible outcome of screening programs would be the identification of individuals eligible for research programs. Preclinical Alzheimer’s is a research construct, not a clinical diagnosis, and is primarily based upon biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in asymptomatic individuals. Group analyses leave little doubt that biomarker evidence of pathology correlates with future clinical outcomes (Ann. Neurol. 2012;71:765-75; Lancet Neurol. 2013 Sept. 4 [doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7]), but at the level of the individual (the clinical level), outcomes vary enough to make prognostication for any given patient unreliable. However, this should not invalidate preclinical Alzheimer’s as the research tool for which it was intended. Rather than declare a stalemate between those who advocate for and against preclinical testing, both sides undoubtedly agree that better therapies are needed, and preclinical Alzheimer’s, as a research construct, offers the opportunity to harness the current "free-for-all" state of genetic screening into a more thoughtfully designed and implemented program with the goal of pairing results with an action plan that, for some, could include participation in a therapeutic trial. What form such screening programs should take, how widespread they should be, and what rules should govern disclosure of results are all questions still in need of answers, but new research opportunities provide a compelling rationale to redesign rather than abandon screening programs.

Dr. Caselli is a professor of neurology and associate director and clinical core director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Alzheimer's research to watch for at AAN

Alzheimer's disease sessions and lectures at this year's American Academy of Neurology annual meeting continue the theme of early detection of symptoms and intervention for modifiable risk factors that have become ever more relevant to ongoing research and treatment efforts.

- Genetics, imaging, and other biomarkers allow us to identify those individuals at the greatest risk, while prevention trials and disease modifying agents have gone from dream to reality. Among the best sessions for these should be Tuesday's Hot Topics plenary session lecture by Alison Goate, D.Phil., titled "Rare and Common Genetic Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease," and the oral abstract session "Amyloid Imaging in the Prediction of and Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease," both on March 19. There’s also the Integrated Neuroscience Session, "Alzheimer's Biomarkers in Clinical Practice," on March 18.

- Trials of monoclonal antibodies, such as solanezumab and bapineuzumab, continue to show enough of an effect to keep our interest on amyloid-modifying therapies, but clinical outcomes remain disappointing and again echo the theme that earlier intervention may be needed. These can be found in the March 20 oral abstract session "Aging and Dementia: Epidemiology and Clinical Science," and the March 22 Clinical Trials plenary presentation by Dr. Ann Hake on solanezumab.

- New studies continue to provide evidence in support of "mom's recipe for good health,", i.e., sleep, exercise, and a good diet, and we can only hope that preventing or delaying dementia will add further impetus to the public to comply with these habits.

- At the Hot Topics plenary, Dr. John Trojanowski’s study on spreading tau fibrils in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy should be absorbing. We have suspected this sort of tau fibril transmission in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, of course (their presence in upper and lower motor neurons hardly seems like a coincidence), but it has been more difficult to prove in anatomically more complex areas like the hippocampus. His study contributes importantly to other research suggesting that a degenerative disease starts in a specific area and spreads from there (just as the stages of pathology have always implied).

Alzheimer's disease sessions and lectures at this year's American Academy of Neurology annual meeting continue the theme of early detection of symptoms and intervention for modifiable risk factors that have become ever more relevant to ongoing research and treatment efforts.

- Genetics, imaging, and other biomarkers allow us to identify those individuals at the greatest risk, while prevention trials and disease modifying agents have gone from dream to reality. Among the best sessions for these should be Tuesday's Hot Topics plenary session lecture by Alison Goate, D.Phil., titled "Rare and Common Genetic Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease," and the oral abstract session "Amyloid Imaging in the Prediction of and Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease," both on March 19. There’s also the Integrated Neuroscience Session, "Alzheimer's Biomarkers in Clinical Practice," on March 18.

- Trials of monoclonal antibodies, such as solanezumab and bapineuzumab, continue to show enough of an effect to keep our interest on amyloid-modifying therapies, but clinical outcomes remain disappointing and again echo the theme that earlier intervention may be needed. These can be found in the March 20 oral abstract session "Aging and Dementia: Epidemiology and Clinical Science," and the March 22 Clinical Trials plenary presentation by Dr. Ann Hake on solanezumab.

- New studies continue to provide evidence in support of "mom's recipe for good health,", i.e., sleep, exercise, and a good diet, and we can only hope that preventing or delaying dementia will add further impetus to the public to comply with these habits.

- At the Hot Topics plenary, Dr. John Trojanowski’s study on spreading tau fibrils in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy should be absorbing. We have suspected this sort of tau fibril transmission in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, of course (their presence in upper and lower motor neurons hardly seems like a coincidence), but it has been more difficult to prove in anatomically more complex areas like the hippocampus. His study contributes importantly to other research suggesting that a degenerative disease starts in a specific area and spreads from there (just as the stages of pathology have always implied).

Alzheimer's disease sessions and lectures at this year's American Academy of Neurology annual meeting continue the theme of early detection of symptoms and intervention for modifiable risk factors that have become ever more relevant to ongoing research and treatment efforts.

- Genetics, imaging, and other biomarkers allow us to identify those individuals at the greatest risk, while prevention trials and disease modifying agents have gone from dream to reality. Among the best sessions for these should be Tuesday's Hot Topics plenary session lecture by Alison Goate, D.Phil., titled "Rare and Common Genetic Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease," and the oral abstract session "Amyloid Imaging in the Prediction of and Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease," both on March 19. There’s also the Integrated Neuroscience Session, "Alzheimer's Biomarkers in Clinical Practice," on March 18.

- Trials of monoclonal antibodies, such as solanezumab and bapineuzumab, continue to show enough of an effect to keep our interest on amyloid-modifying therapies, but clinical outcomes remain disappointing and again echo the theme that earlier intervention may be needed. These can be found in the March 20 oral abstract session "Aging and Dementia: Epidemiology and Clinical Science," and the March 22 Clinical Trials plenary presentation by Dr. Ann Hake on solanezumab.

- New studies continue to provide evidence in support of "mom's recipe for good health,", i.e., sleep, exercise, and a good diet, and we can only hope that preventing or delaying dementia will add further impetus to the public to comply with these habits.

- At the Hot Topics plenary, Dr. John Trojanowski’s study on spreading tau fibrils in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy should be absorbing. We have suspected this sort of tau fibril transmission in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, of course (their presence in upper and lower motor neurons hardly seems like a coincidence), but it has been more difficult to prove in anatomically more complex areas like the hippocampus. His study contributes importantly to other research suggesting that a degenerative disease starts in a specific area and spreads from there (just as the stages of pathology have always implied).

Viewing the Creative Process Through a Life Span

This is the last chapter of our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders. My how time flies! There is so much we could still say, but the basic pieces are now there for you to continue considering on your own. If I could leave you with a time-lapse inner monologue summarizing the creative experience of human life, it would go something like this:

Motivation

Appetitive and aversive, approach and avoid, love and hate – this essentially is the underlying theme of life. It may be the theme of more than just human life, too. Humans, chimpanzees, and other primates – in fact, most creatures down through fish and even insects and microbes – cluster together in groups yet compete with one another within the groups: killing each other, hating each other, and avoiding each other, yet remaining within the larger social grouping. This is the paradox of our existence and may be the social need, the insatiable conflict that needs constant soothing.

Part one – I am born – is already skipping a step. In part zero, I am conceived, and in fractional parts up to one, I am undergoing fetal development so that by the time I am born, I already have defined motivations of want and fear. I have yet to perceive, yet to envision, yet to plan, yet to act, yet to manage, yet to socialize, but I have my motivations.

Perception

I am born, and I am alive. My prewired circuits are pulsing with spontaneous activity – spontaneously generated rhythms that are modestly but significantly altered as I perceive the world around me. I see, hear, feel, smell, and taste it. I move and it is altered, even if just a little. I begin to associate things I perceive with my motivations. If I am hungry, milk and food satisfies my hunger and satisfies me. If I am alone, I am afraid, but the arrival of my mother, of someone familiar who feeds me, holds me, and keeps me warm, dispels my fear.

I am getting smart. I feel my hunger, and I remember what makes it better. I envision the arrival of food before it actually comes. I am learning what I want. When I feel afraid, I remember what makes it go away. I envision the arrival of my mother before she even gets there. And I even know if the wrong thing happens. If I am crying because I am hungry and someone gives me a toy, that is not what I want, and it is not what I envisioned. I expected food, and I want food. If the wrong person arrives, some stranger who is not who I expected, that is not who I want. I want my mother.

Action

I am getting really smart. I know when it is lunch time and where the cookies are. I can figure out when to have a snack so I am not too hungry but so I can still eat my dinner at dinnertime. I can even go to the store and get what I want (well, some things anyway, like a pack of gum). But it’s getting harder, more difficult. As I get older, people do not always give me what I want, I have to figure out ways to get things on my own more often. And that requires certain skills, without skills I have no value to trade for money that lets me buy what I want. So I am going to school, I am getting educated, I am working and learning as I work, getting better at what I do. I am getting promoted, I am graduating, I am climbing some kind of "ladder" and the higher I go, the more I can get.

Temperament

This ladder climbing and getting what I want requires some thought. I have many needs now. I want a fancy car, but I need to pay the rent. Some day, I want to buy a house. I think I want to be the boss, but that means I need to spend more time in school or at work. It means I have to perform at a higher and higher level. My own children have needs, and sometimes they need things at a time when I have other commitments, and I have to choose what to do. Some of the tasks I am given, or some of the paths I have taken have been less successful than others. My time is valuable. I have to choose carefully what I pursue and what I don’t and when to let something go and when to stick with it. Gosh, there are times I want to just throw my hands up, but I have control myself.

Social context

Society has needs and wants just like I do. I want society to like me, to support me, to reward me. If I make society happy, I will be rewarded. If I make society angry, I may get punished. If I bore society, or if society does not notice me, I will simply tread along my way but not advance very far. What does society want? Society is made up of people like me. In groups, there is a new identity that emerges. Some people are Christians, some are Muslims; some are Knicks fans, some are Lakers fans; some are Republicans, some Democrats; and some are foreigners from places like Mexico, Germany, Italy, Haiti, and China. Foreigners are different from Americans, and even from one another, depending on where they are from. It seems the groups define the identity of its members, at least to a degree. But they all have one thing in common. They all share that love-hate paradox of wanting to belong to the group while hating individuals within the group, competing with them, even sometimes killing them.

So what can I bring to the group? Something that soothes that inner love-hate conflict.

I hope you have enjoyed exploring creativity with me as much as I have enjoyed exploring it with you. Thanks for all the well wishes I have received for this column, they have meant a great deal to me. And thanks to Jeff Evans, the managing editor who indulged me this opportunity, and to IMNG Medical Media for publishing this work. And now ... back to my real job as a neurologist. See you all at the meetings!

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz

This is the last chapter of our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders. My how time flies! There is so much we could still say, but the basic pieces are now there for you to continue considering on your own. If I could leave you with a time-lapse inner monologue summarizing the creative experience of human life, it would go something like this:

Motivation

Appetitive and aversive, approach and avoid, love and hate – this essentially is the underlying theme of life. It may be the theme of more than just human life, too. Humans, chimpanzees, and other primates – in fact, most creatures down through fish and even insects and microbes – cluster together in groups yet compete with one another within the groups: killing each other, hating each other, and avoiding each other, yet remaining within the larger social grouping. This is the paradox of our existence and may be the social need, the insatiable conflict that needs constant soothing.

Part one – I am born – is already skipping a step. In part zero, I am conceived, and in fractional parts up to one, I am undergoing fetal development so that by the time I am born, I already have defined motivations of want and fear. I have yet to perceive, yet to envision, yet to plan, yet to act, yet to manage, yet to socialize, but I have my motivations.

Perception

I am born, and I am alive. My prewired circuits are pulsing with spontaneous activity – spontaneously generated rhythms that are modestly but significantly altered as I perceive the world around me. I see, hear, feel, smell, and taste it. I move and it is altered, even if just a little. I begin to associate things I perceive with my motivations. If I am hungry, milk and food satisfies my hunger and satisfies me. If I am alone, I am afraid, but the arrival of my mother, of someone familiar who feeds me, holds me, and keeps me warm, dispels my fear.

I am getting smart. I feel my hunger, and I remember what makes it better. I envision the arrival of food before it actually comes. I am learning what I want. When I feel afraid, I remember what makes it go away. I envision the arrival of my mother before she even gets there. And I even know if the wrong thing happens. If I am crying because I am hungry and someone gives me a toy, that is not what I want, and it is not what I envisioned. I expected food, and I want food. If the wrong person arrives, some stranger who is not who I expected, that is not who I want. I want my mother.

Action

I am getting really smart. I know when it is lunch time and where the cookies are. I can figure out when to have a snack so I am not too hungry but so I can still eat my dinner at dinnertime. I can even go to the store and get what I want (well, some things anyway, like a pack of gum). But it’s getting harder, more difficult. As I get older, people do not always give me what I want, I have to figure out ways to get things on my own more often. And that requires certain skills, without skills I have no value to trade for money that lets me buy what I want. So I am going to school, I am getting educated, I am working and learning as I work, getting better at what I do. I am getting promoted, I am graduating, I am climbing some kind of "ladder" and the higher I go, the more I can get.

Temperament

This ladder climbing and getting what I want requires some thought. I have many needs now. I want a fancy car, but I need to pay the rent. Some day, I want to buy a house. I think I want to be the boss, but that means I need to spend more time in school or at work. It means I have to perform at a higher and higher level. My own children have needs, and sometimes they need things at a time when I have other commitments, and I have to choose what to do. Some of the tasks I am given, or some of the paths I have taken have been less successful than others. My time is valuable. I have to choose carefully what I pursue and what I don’t and when to let something go and when to stick with it. Gosh, there are times I want to just throw my hands up, but I have control myself.

Social context

Society has needs and wants just like I do. I want society to like me, to support me, to reward me. If I make society happy, I will be rewarded. If I make society angry, I may get punished. If I bore society, or if society does not notice me, I will simply tread along my way but not advance very far. What does society want? Society is made up of people like me. In groups, there is a new identity that emerges. Some people are Christians, some are Muslims; some are Knicks fans, some are Lakers fans; some are Republicans, some Democrats; and some are foreigners from places like Mexico, Germany, Italy, Haiti, and China. Foreigners are different from Americans, and even from one another, depending on where they are from. It seems the groups define the identity of its members, at least to a degree. But they all have one thing in common. They all share that love-hate paradox of wanting to belong to the group while hating individuals within the group, competing with them, even sometimes killing them.

So what can I bring to the group? Something that soothes that inner love-hate conflict.

I hope you have enjoyed exploring creativity with me as much as I have enjoyed exploring it with you. Thanks for all the well wishes I have received for this column, they have meant a great deal to me. And thanks to Jeff Evans, the managing editor who indulged me this opportunity, and to IMNG Medical Media for publishing this work. And now ... back to my real job as a neurologist. See you all at the meetings!

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz

This is the last chapter of our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders. My how time flies! There is so much we could still say, but the basic pieces are now there for you to continue considering on your own. If I could leave you with a time-lapse inner monologue summarizing the creative experience of human life, it would go something like this:

Motivation

Appetitive and aversive, approach and avoid, love and hate – this essentially is the underlying theme of life. It may be the theme of more than just human life, too. Humans, chimpanzees, and other primates – in fact, most creatures down through fish and even insects and microbes – cluster together in groups yet compete with one another within the groups: killing each other, hating each other, and avoiding each other, yet remaining within the larger social grouping. This is the paradox of our existence and may be the social need, the insatiable conflict that needs constant soothing.

Part one – I am born – is already skipping a step. In part zero, I am conceived, and in fractional parts up to one, I am undergoing fetal development so that by the time I am born, I already have defined motivations of want and fear. I have yet to perceive, yet to envision, yet to plan, yet to act, yet to manage, yet to socialize, but I have my motivations.

Perception

I am born, and I am alive. My prewired circuits are pulsing with spontaneous activity – spontaneously generated rhythms that are modestly but significantly altered as I perceive the world around me. I see, hear, feel, smell, and taste it. I move and it is altered, even if just a little. I begin to associate things I perceive with my motivations. If I am hungry, milk and food satisfies my hunger and satisfies me. If I am alone, I am afraid, but the arrival of my mother, of someone familiar who feeds me, holds me, and keeps me warm, dispels my fear.

I am getting smart. I feel my hunger, and I remember what makes it better. I envision the arrival of food before it actually comes. I am learning what I want. When I feel afraid, I remember what makes it go away. I envision the arrival of my mother before she even gets there. And I even know if the wrong thing happens. If I am crying because I am hungry and someone gives me a toy, that is not what I want, and it is not what I envisioned. I expected food, and I want food. If the wrong person arrives, some stranger who is not who I expected, that is not who I want. I want my mother.

Action

I am getting really smart. I know when it is lunch time and where the cookies are. I can figure out when to have a snack so I am not too hungry but so I can still eat my dinner at dinnertime. I can even go to the store and get what I want (well, some things anyway, like a pack of gum). But it’s getting harder, more difficult. As I get older, people do not always give me what I want, I have to figure out ways to get things on my own more often. And that requires certain skills, without skills I have no value to trade for money that lets me buy what I want. So I am going to school, I am getting educated, I am working and learning as I work, getting better at what I do. I am getting promoted, I am graduating, I am climbing some kind of "ladder" and the higher I go, the more I can get.

Temperament

This ladder climbing and getting what I want requires some thought. I have many needs now. I want a fancy car, but I need to pay the rent. Some day, I want to buy a house. I think I want to be the boss, but that means I need to spend more time in school or at work. It means I have to perform at a higher and higher level. My own children have needs, and sometimes they need things at a time when I have other commitments, and I have to choose what to do. Some of the tasks I am given, or some of the paths I have taken have been less successful than others. My time is valuable. I have to choose carefully what I pursue and what I don’t and when to let something go and when to stick with it. Gosh, there are times I want to just throw my hands up, but I have control myself.

Social context

Society has needs and wants just like I do. I want society to like me, to support me, to reward me. If I make society happy, I will be rewarded. If I make society angry, I may get punished. If I bore society, or if society does not notice me, I will simply tread along my way but not advance very far. What does society want? Society is made up of people like me. In groups, there is a new identity that emerges. Some people are Christians, some are Muslims; some are Knicks fans, some are Lakers fans; some are Republicans, some Democrats; and some are foreigners from places like Mexico, Germany, Italy, Haiti, and China. Foreigners are different from Americans, and even from one another, depending on where they are from. It seems the groups define the identity of its members, at least to a degree. But they all have one thing in common. They all share that love-hate paradox of wanting to belong to the group while hating individuals within the group, competing with them, even sometimes killing them.

So what can I bring to the group? Something that soothes that inner love-hate conflict.

I hope you have enjoyed exploring creativity with me as much as I have enjoyed exploring it with you. Thanks for all the well wishes I have received for this column, they have meant a great deal to me. And thanks to Jeff Evans, the managing editor who indulged me this opportunity, and to IMNG Medical Media for publishing this work. And now ... back to my real job as a neurologist. See you all at the meetings!

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz

Aging's Effect on Creativity Involves Trade-offs

In the last installment of this column we considered how group creativity can go very wrong even when all the neurobiological pieces are working properly. In this installment we will discuss how aging, a normal and inevitable consequence of living, affects these neurobiological pieces and in turn might affect creativity. The effect of age on creativity is particularly salient at this time when the most rapidly growing age demographic of our society is the oldest old. We see this in and around us: Baby boomers are reaching retirement, medical advances are reducing the rate of disease-related deaths, physicians are aging, we neurologists are aging.

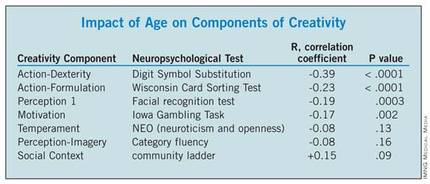

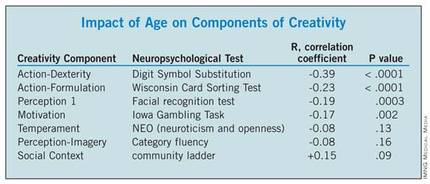

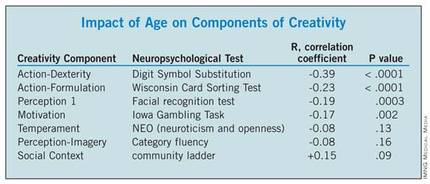

There are many cognitive manifestations of aging. In a cognitive aging study of the Arizona APOE Cohort that I led (Neurology 2011;76:1383-8), neuropsychological measures reflecting different components of creativity tended to decline with age (as seen in the accompanying table). These are the same components of the model of creativity that I introduced in a previous column. The cohort included 351 healthy individuals aged 21-81 years (two-thirds were women), with a mean educational level of nearly 16 years, who completed the Iowa Gambling Task and a battery of other tests.

The data in the table are presented for illustration purposes only, and do not constitute a thorough analysis of all aspects of creativity, but our findings do reflect those that others have reported as well in studies focused on creativity. With increasing age comes greater wisdom (as reflected by higher scores on tests of general knowledge and vocabulary not shown above), greater accumulated assets both materially and in terms of social standing (reflected in the Community ladder above). On the other hand, there appears to be a decline in motivational intensity and reward-based learning caused by age-related alterations in reward systems (Brain Res. Bull. 2005;67:382-90). Senescent changes in the neural machinery of perception, executive function, and dexterity cause these skills to decline even more (Am. J. Psychiatry 1998;155:344-9), and if our data is at all representative, it is in the area of action – including both strategic formulation and dexterous execution – that the biggest declines occur. Temperament, on the other hand, seems to be relatively stable, showing little change with age.

What is the net effect of increasing knowledge, assets, and social standing coupled with declining motivation, perception, and execution on individual creativity? Studies of creative productivity over a lifetime have revealed that noteworthy achievements tend to remain in constant proportion to one’s total creative output (Psychol. Bull. 1988;104:251-67). That is, the more one creates, the more noteworthy creations are produced. Even in old age, this ratio generally remains constant. What changes is the total output. Over the course of a lifetime, there is a ramp-up period leading eventually to a maximally productive phase, typically from one’s late 30s to their late 40s or early 50s (depending in part on the field of creative endeavor), and then a declining phase (not as steep as the initial ramp-up phase). The later years are also vulnerable to external circumstances such as illness and family problems. So the good news is that one’s ability to generate good work does not decline with age. The bad news is that total productivity does decline, and so too therefore does the total number of noteworthy contributions. This has been demonstrated in a variety of creative arenas including the arts and sciences.

Leadership ability, a specific form of creative behavior, appears to be relatively resilient with age. Two different aspects of cognition are crystallized or accumulated knowledge and fluid ability reflecting reasoning, memory, and speed. Our fluid ability peaks before age 30, yet the peak age for CEOs is 60. Accumulated knowledge increases with age until roughly age 60, after which it declines modestly, while fluid ability, such as novel problem solving, declines more steeply with age after its early age peak.

What accounts for the mismatch between declining fluid intelligence and work performance is unclear but may reflect at least four factors, including 1) one seldom needs to perform at their maximum level, 2) there is a shift with age from novel processing (fluid problem solving) to greater reliance on accumulated knowledge, 3) cognition may not be the only determinant of success ("can do, will do, have done"... the latter two represent temperament and experience), and 4) accommodations can be made for some declining skills (Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:201-26). A fifth possibly related factor may be that older-appearing individuals are preferred as leaders during times of intergroup conflict (PLoS One 2012;7:e36945), a state in which most companies find themselves most of the time.

However, group members who are not in leadership positions may not be as fortunate. Few things are the same now as they were 10 years ago, and the rate of change has accelerated in the computer-catalyzed information age. Biological evolution may be slow, but ideas evolve quickly.

Meme evolution eventually results in meme speciation, with the consequence that memes of different species can no longer interbreed. Consider the example of subspecialization in medicine. We all begin as medical students with a common knowledge base and vernacular, but with subspecialization a child psychiatrist no longer has anything in common with a transplant surgeon. Even within neurology, there is little knowledge shared between epileptologists and neuroimmunologists.

Older individuals who failed to align themselves with one meme line (or physicians who failed to specialize) may find their ideas can no longer "interbreed" with the new meme species (or currently practiced medical specialties). Even within a field, those who fail to keep up with evolving technology will find themselves left behind, such as an aging surgeon who may not have mastered new robotic techniques or an aging secretary who may not understand the latest software. Add to this state of brain affairs, the prevalent ailments of the aging body such as arthritis, hypertension, and deconditioning, and we find that our workforce is not simply getting older, it actually is at risk of becoming obsolete.

And so the effects of age upon our creative behavior are varied and determined not only by our neurobiology, but also by our health (both physical and mental), our family and friends, and our fortune (or lack of it). Next month, we will conclude our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders.

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the last installment of this column we considered how group creativity can go very wrong even when all the neurobiological pieces are working properly. In this installment we will discuss how aging, a normal and inevitable consequence of living, affects these neurobiological pieces and in turn might affect creativity. The effect of age on creativity is particularly salient at this time when the most rapidly growing age demographic of our society is the oldest old. We see this in and around us: Baby boomers are reaching retirement, medical advances are reducing the rate of disease-related deaths, physicians are aging, we neurologists are aging.

There are many cognitive manifestations of aging. In a cognitive aging study of the Arizona APOE Cohort that I led (Neurology 2011;76:1383-8), neuropsychological measures reflecting different components of creativity tended to decline with age (as seen in the accompanying table). These are the same components of the model of creativity that I introduced in a previous column. The cohort included 351 healthy individuals aged 21-81 years (two-thirds were women), with a mean educational level of nearly 16 years, who completed the Iowa Gambling Task and a battery of other tests.

The data in the table are presented for illustration purposes only, and do not constitute a thorough analysis of all aspects of creativity, but our findings do reflect those that others have reported as well in studies focused on creativity. With increasing age comes greater wisdom (as reflected by higher scores on tests of general knowledge and vocabulary not shown above), greater accumulated assets both materially and in terms of social standing (reflected in the Community ladder above). On the other hand, there appears to be a decline in motivational intensity and reward-based learning caused by age-related alterations in reward systems (Brain Res. Bull. 2005;67:382-90). Senescent changes in the neural machinery of perception, executive function, and dexterity cause these skills to decline even more (Am. J. Psychiatry 1998;155:344-9), and if our data is at all representative, it is in the area of action – including both strategic formulation and dexterous execution – that the biggest declines occur. Temperament, on the other hand, seems to be relatively stable, showing little change with age.

What is the net effect of increasing knowledge, assets, and social standing coupled with declining motivation, perception, and execution on individual creativity? Studies of creative productivity over a lifetime have revealed that noteworthy achievements tend to remain in constant proportion to one’s total creative output (Psychol. Bull. 1988;104:251-67). That is, the more one creates, the more noteworthy creations are produced. Even in old age, this ratio generally remains constant. What changes is the total output. Over the course of a lifetime, there is a ramp-up period leading eventually to a maximally productive phase, typically from one’s late 30s to their late 40s or early 50s (depending in part on the field of creative endeavor), and then a declining phase (not as steep as the initial ramp-up phase). The later years are also vulnerable to external circumstances such as illness and family problems. So the good news is that one’s ability to generate good work does not decline with age. The bad news is that total productivity does decline, and so too therefore does the total number of noteworthy contributions. This has been demonstrated in a variety of creative arenas including the arts and sciences.

Leadership ability, a specific form of creative behavior, appears to be relatively resilient with age. Two different aspects of cognition are crystallized or accumulated knowledge and fluid ability reflecting reasoning, memory, and speed. Our fluid ability peaks before age 30, yet the peak age for CEOs is 60. Accumulated knowledge increases with age until roughly age 60, after which it declines modestly, while fluid ability, such as novel problem solving, declines more steeply with age after its early age peak.