User login

Bell Palsy Mimics

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

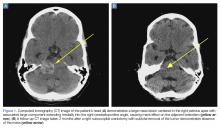

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

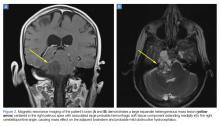

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

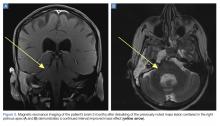

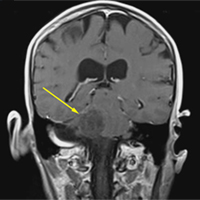

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

Thyroid Cartilage Fracture in Context of Noncompetitive "Horseplay" Wrestling

An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7

Case

A 38-year-old man presented with a complaint of throat pain after wrestling at home, in horseplay, with his 15-year-old son. He reported that when his son placed a choke hold on him, he felt a "crack" in the area of his neck, and soon afterwards felt throat pain with swallowing, along with discomfort with breathing. He also felt a sensation of "fluid building up in his throat." There were no changes noted with his voice and the patient was speaking in full sentences. There was no wheezing or stridor. He denied shortness of breath or any other complaints. He denied pain over the posterior elements of his cervical spine. At the time of the incident, there was no loss of consciousness. Palpation of the neck and chest did not elicit any crepitance to suggest subcutaneous emphysema. The trachea was midline. There was no pain overlying the carotids bilaterally, and the patient had no bruits. The neck examination did not show any surface abnormalities to suggest trauma, such as ecchymosis or swelling. He did have slight tenderness to palpation over the thyroid cartilage.

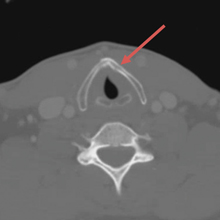

The patient was sent for a computed tomography (CT) scan of the soft-tissue neck with intravenous (IV) contrast, and a CT scan of the cervical spine. The results showed no cervical spine fracture. However, there was a minimally displaced fracture of the left thyroid cartilage, with soft-tissue swelling that was noted, along with minimal narrowing of the subglottic trachea. There were no abnormal enhancements or fluid collections. No evidence of vocal cord abnormality or asymmetry was seen, and there was no evidence of airway compromise (Figure).

Discussion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. A thyroid cartilage fracture is a type of laryngeal fracture. Using an anatomic system in which such injuries are classified by location (supraglottic, glottis, or infraglottic), a thyroid cartilage fracture is classified as a supraglottic laryngeal injury.1,2 In our case, the fracture was due to a blunt force mechanism. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma.8 An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature.

Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7 When reported, significant force is usually involved. For example, Tasca et al6 reported a thyroid cartilage fracture from direct blunt trauma (rugby, opponent stamped on patient’s throat) in which the patient presented with pain with swallowing and a lowering of the pitch of his voice. Rejali et al9 reported the case of a midair collision in a soccer match, resulting in an obvious mandibular fracture, but with an arytenoid cartilage fracture that was not initially identified. A football struck a 17-year-old boy with a resulting fracture of the superior cornu of the larynx and a puncture of the laryngeal mucosal wall in a case reported by Saab and Birkinshaw.10 The patient presented with neck pain and dysphagia, as well as subcutaneous air.10 A 21-year-old collegiate basketball player was struck in the neck by a teammate’s head while jumping for a rebound. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage and a fracture of the anterior cricoid ring.3 Patients with such injuries "may appear deceptively normal when seeking medical attention."8 Kragha2 refers to such injuries as "rare but potentially deadly."

Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, and even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of prominence of the thyroid cartilage.3 Tracheal deviation and stridor can occur.10,11 Computed tomography scan and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process; 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions may be needed.

Various classification systems have been proposed with related treatment strategies. Percevik et al11 summarized a five-part clinical classification. Group 1 (hematoma, no fracture) and Group 2 (non-displaced fracture) may be treated conservatively. Group 3 (stable, displaced fracture), Group 4 (unstable, displaced fracture), and Group 5 (laryngotracheal disinsertion) are more likely to be treated with surgery.11 Surgical techniques vary and have been refined over time.12

In this case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible that this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive force. Lin et al,1 described a case of neck hyperflexion in an unrestrained driver, with a resulting isolated thyroid cartilage fracture without direct impact to the neck. Walsh and Trotter5 presented a case of a motorcyclist with a blow to the back of the head, with resulting neck hyperflexion, which resulted in a fracture of the thyroid cartilage. Beato-Martínez et al,13 reported a case of thyroid cartilage fracture following a sneezing episode. The patient presented with odynophagia, dysphonia and neck pain.13 In our review of the literature, we found that only one other similar case has been reported. In that case, a patient experienced a feeling of a neck click, followed by neck pain and hoarseness. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage.14

In reviewing the hyperflexion mechanism, Lin et al1 noted that isolated thyroid cartilage fractures are rare and that "most of these are caused by direct injury to the neck, except for two patients reported in the literature who sustained isolated thyroid cartilage fractures after sneezing." Lin et al1 proposed an interesting hypothesis—that "the mechanism causing thyroid cartilage fracture during impaction may be the same with sneezing." Sneezing can be associated with sudden and forceful flexion of the neck.

It is certainly possible that this hyperflexion mechanism was involved in our case, given there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck, as in the sports-related injuries discussed. Wrestling holds can produce hyperflexion. The patient described a feeling of a "crack", which is similar to the clicking sound described in one of the sneezing-related cases. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is rare in the absence of major trauma. However, as noted by Rejali et al,9 this can create a potential management pitfall. "In the context of non-contact sports, the attendant doctor may not realize the significance of apparently minor head and neck trauma."9

There are no series data to provide us with an exact incidence of airway compromise. However, seemingly minor insults to the anterior neck can cause posterior compression of the larynx and can result in airway compromise.9-11

The CT scan is described as an important imaging modality to rule out cervical spine fracture. Although there was no significant blunt force, the cervical spine was exposed to hyperflexion forces. Another important potential consequence is long-term injury to the vocal cords, with subsequent speech difficulties.11 Computed tomography can visualize the thyroid fracture, but many authors point out that visualization of the vocal cords, with nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy or other modality, is an important adjunct to the CT scan.9-11

Otolaryngologist consultation should be strongly considered. This patient was transferred to a tertiary care center with expertise in thyroid fractures, and planned nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy to be performed at the receiving institution.

Conclusion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, or even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, tracheal deviation, and stridor. Computed tomography scan imaging with 3-D reconstructions and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process. In our case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive forces, similar to that described by Lin et al.1 Certainly, there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck on the level of the sports-related injuries discussed.

1. Lin HL, Kuo LC, Chen CW, Cheng YC, Lee WC. Neck hyperflexion causing isolated thyroid cartilage fracture--a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(9):1064.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.030

2. Kragha KO. Acute traumatic injury of the larynx. Case Reports in Otolaryngology. Volume 2015. Article ID393978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/393978

3. Kim JD, Shuler FD, Mo B, Gibbs SR, Belmaggio T, Giangarra CE. Traumatic laryngeal fracture in a collegiate basketball player. Sports Health. 2013;5(3):

273-275.

4. Knopke S, Todt I, Ernst A, Seidl RO. Pseudarthroses of the cornu of the thyroid cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(2):186-189. doi:10.1016/5.otohns.2010.04.011.

5. Walsh PV, Trotter GA. Fracture of the thyroid cartilage associated with full face integral crash helmet. Injury. 1979;11(1):47-48.

6. Tasca RA, Sherman IW, Wood GD. Thyroid cartilage fracture: treatment with biodegradable plates. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(2):159-160.

7. Mitrović SM. Blunt external laryngeal trauma. Two case reports. Med Pregl. 2007;60(9-10):489-492.

8. O'Keefe LJ, Maw AR. The dangers of minor blunt laryngeal trauma. J. Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(4):372-373.

9. Rejali SD, Bennett JD, Upile T, Rothera MP. Diagnostic pitfalls in sports related laryngeal injury. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(2):180-181.

10. Saab M, Birkinshaw R. Blunt laryngeal trauma: an unusual case. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51(8):527.

11. Pekcevik Y, Ibrahim C, Ülker C. Cricoid and thyroid cartilage fracture, cricothyroid joint dislocation,pseudofracture appearance of the hyoid bone: CT, MRI and laryngoscopic findings. JAEM. 2013;12:170-173.

12. Bent JP 3rd, Porubsky ES. The management of blunt fractures of the thyroid cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;110(2):195-202. doi: 10:.1177/019459989411000209.

13. Beato Martínez A, Moreno Juara A, López Moya JJ. Fracture of thyroid cartilage after a sneezing episode. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58(2):73-74.

14. Quinlan PT. Fracture of thyroid cartilage during a sneezing attack. Br Med J. 1950;1(4661):1052.

An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7

Case

A 38-year-old man presented with a complaint of throat pain after wrestling at home, in horseplay, with his 15-year-old son. He reported that when his son placed a choke hold on him, he felt a "crack" in the area of his neck, and soon afterwards felt throat pain with swallowing, along with discomfort with breathing. He also felt a sensation of "fluid building up in his throat." There were no changes noted with his voice and the patient was speaking in full sentences. There was no wheezing or stridor. He denied shortness of breath or any other complaints. He denied pain over the posterior elements of his cervical spine. At the time of the incident, there was no loss of consciousness. Palpation of the neck and chest did not elicit any crepitance to suggest subcutaneous emphysema. The trachea was midline. There was no pain overlying the carotids bilaterally, and the patient had no bruits. The neck examination did not show any surface abnormalities to suggest trauma, such as ecchymosis or swelling. He did have slight tenderness to palpation over the thyroid cartilage.

The patient was sent for a computed tomography (CT) scan of the soft-tissue neck with intravenous (IV) contrast, and a CT scan of the cervical spine. The results showed no cervical spine fracture. However, there was a minimally displaced fracture of the left thyroid cartilage, with soft-tissue swelling that was noted, along with minimal narrowing of the subglottic trachea. There were no abnormal enhancements or fluid collections. No evidence of vocal cord abnormality or asymmetry was seen, and there was no evidence of airway compromise (Figure).

Discussion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. A thyroid cartilage fracture is a type of laryngeal fracture. Using an anatomic system in which such injuries are classified by location (supraglottic, glottis, or infraglottic), a thyroid cartilage fracture is classified as a supraglottic laryngeal injury.1,2 In our case, the fracture was due to a blunt force mechanism. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma.8 An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature.

Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7 When reported, significant force is usually involved. For example, Tasca et al6 reported a thyroid cartilage fracture from direct blunt trauma (rugby, opponent stamped on patient’s throat) in which the patient presented with pain with swallowing and a lowering of the pitch of his voice. Rejali et al9 reported the case of a midair collision in a soccer match, resulting in an obvious mandibular fracture, but with an arytenoid cartilage fracture that was not initially identified. A football struck a 17-year-old boy with a resulting fracture of the superior cornu of the larynx and a puncture of the laryngeal mucosal wall in a case reported by Saab and Birkinshaw.10 The patient presented with neck pain and dysphagia, as well as subcutaneous air.10 A 21-year-old collegiate basketball player was struck in the neck by a teammate’s head while jumping for a rebound. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage and a fracture of the anterior cricoid ring.3 Patients with such injuries "may appear deceptively normal when seeking medical attention."8 Kragha2 refers to such injuries as "rare but potentially deadly."

Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, and even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of prominence of the thyroid cartilage.3 Tracheal deviation and stridor can occur.10,11 Computed tomography scan and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process; 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions may be needed.

Various classification systems have been proposed with related treatment strategies. Percevik et al11 summarized a five-part clinical classification. Group 1 (hematoma, no fracture) and Group 2 (non-displaced fracture) may be treated conservatively. Group 3 (stable, displaced fracture), Group 4 (unstable, displaced fracture), and Group 5 (laryngotracheal disinsertion) are more likely to be treated with surgery.11 Surgical techniques vary and have been refined over time.12

In this case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible that this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive force. Lin et al,1 described a case of neck hyperflexion in an unrestrained driver, with a resulting isolated thyroid cartilage fracture without direct impact to the neck. Walsh and Trotter5 presented a case of a motorcyclist with a blow to the back of the head, with resulting neck hyperflexion, which resulted in a fracture of the thyroid cartilage. Beato-Martínez et al,13 reported a case of thyroid cartilage fracture following a sneezing episode. The patient presented with odynophagia, dysphonia and neck pain.13 In our review of the literature, we found that only one other similar case has been reported. In that case, a patient experienced a feeling of a neck click, followed by neck pain and hoarseness. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage.14

In reviewing the hyperflexion mechanism, Lin et al1 noted that isolated thyroid cartilage fractures are rare and that "most of these are caused by direct injury to the neck, except for two patients reported in the literature who sustained isolated thyroid cartilage fractures after sneezing." Lin et al1 proposed an interesting hypothesis—that "the mechanism causing thyroid cartilage fracture during impaction may be the same with sneezing." Sneezing can be associated with sudden and forceful flexion of the neck.

It is certainly possible that this hyperflexion mechanism was involved in our case, given there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck, as in the sports-related injuries discussed. Wrestling holds can produce hyperflexion. The patient described a feeling of a "crack", which is similar to the clicking sound described in one of the sneezing-related cases. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is rare in the absence of major trauma. However, as noted by Rejali et al,9 this can create a potential management pitfall. "In the context of non-contact sports, the attendant doctor may not realize the significance of apparently minor head and neck trauma."9

There are no series data to provide us with an exact incidence of airway compromise. However, seemingly minor insults to the anterior neck can cause posterior compression of the larynx and can result in airway compromise.9-11

The CT scan is described as an important imaging modality to rule out cervical spine fracture. Although there was no significant blunt force, the cervical spine was exposed to hyperflexion forces. Another important potential consequence is long-term injury to the vocal cords, with subsequent speech difficulties.11 Computed tomography can visualize the thyroid fracture, but many authors point out that visualization of the vocal cords, with nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy or other modality, is an important adjunct to the CT scan.9-11

Otolaryngologist consultation should be strongly considered. This patient was transferred to a tertiary care center with expertise in thyroid fractures, and planned nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy to be performed at the receiving institution.

Conclusion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, or even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, tracheal deviation, and stridor. Computed tomography scan imaging with 3-D reconstructions and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process. In our case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive forces, similar to that described by Lin et al.1 Certainly, there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck on the level of the sports-related injuries discussed.

An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7

Case

A 38-year-old man presented with a complaint of throat pain after wrestling at home, in horseplay, with his 15-year-old son. He reported that when his son placed a choke hold on him, he felt a "crack" in the area of his neck, and soon afterwards felt throat pain with swallowing, along with discomfort with breathing. He also felt a sensation of "fluid building up in his throat." There were no changes noted with his voice and the patient was speaking in full sentences. There was no wheezing or stridor. He denied shortness of breath or any other complaints. He denied pain over the posterior elements of his cervical spine. At the time of the incident, there was no loss of consciousness. Palpation of the neck and chest did not elicit any crepitance to suggest subcutaneous emphysema. The trachea was midline. There was no pain overlying the carotids bilaterally, and the patient had no bruits. The neck examination did not show any surface abnormalities to suggest trauma, such as ecchymosis or swelling. He did have slight tenderness to palpation over the thyroid cartilage.

The patient was sent for a computed tomography (CT) scan of the soft-tissue neck with intravenous (IV) contrast, and a CT scan of the cervical spine. The results showed no cervical spine fracture. However, there was a minimally displaced fracture of the left thyroid cartilage, with soft-tissue swelling that was noted, along with minimal narrowing of the subglottic trachea. There were no abnormal enhancements or fluid collections. No evidence of vocal cord abnormality or asymmetry was seen, and there was no evidence of airway compromise (Figure).

Discussion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. A thyroid cartilage fracture is a type of laryngeal fracture. Using an anatomic system in which such injuries are classified by location (supraglottic, glottis, or infraglottic), a thyroid cartilage fracture is classified as a supraglottic laryngeal injury.1,2 In our case, the fracture was due to a blunt force mechanism. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma.8 An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare.1-5 More interestingly, an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature.

Sports-related injuries to the larynx and related structures are uncommon.6,7 When reported, significant force is usually involved. For example, Tasca et al6 reported a thyroid cartilage fracture from direct blunt trauma (rugby, opponent stamped on patient’s throat) in which the patient presented with pain with swallowing and a lowering of the pitch of his voice. Rejali et al9 reported the case of a midair collision in a soccer match, resulting in an obvious mandibular fracture, but with an arytenoid cartilage fracture that was not initially identified. A football struck a 17-year-old boy with a resulting fracture of the superior cornu of the larynx and a puncture of the laryngeal mucosal wall in a case reported by Saab and Birkinshaw.10 The patient presented with neck pain and dysphagia, as well as subcutaneous air.10 A 21-year-old collegiate basketball player was struck in the neck by a teammate’s head while jumping for a rebound. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage and a fracture of the anterior cricoid ring.3 Patients with such injuries "may appear deceptively normal when seeking medical attention."8 Kragha2 refers to such injuries as "rare but potentially deadly."

Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, and even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of prominence of the thyroid cartilage.3 Tracheal deviation and stridor can occur.10,11 Computed tomography scan and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process; 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions may be needed.

Various classification systems have been proposed with related treatment strategies. Percevik et al11 summarized a five-part clinical classification. Group 1 (hematoma, no fracture) and Group 2 (non-displaced fracture) may be treated conservatively. Group 3 (stable, displaced fracture), Group 4 (unstable, displaced fracture), and Group 5 (laryngotracheal disinsertion) are more likely to be treated with surgery.11 Surgical techniques vary and have been refined over time.12

In this case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible that this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive force. Lin et al,1 described a case of neck hyperflexion in an unrestrained driver, with a resulting isolated thyroid cartilage fracture without direct impact to the neck. Walsh and Trotter5 presented a case of a motorcyclist with a blow to the back of the head, with resulting neck hyperflexion, which resulted in a fracture of the thyroid cartilage. Beato-Martínez et al,13 reported a case of thyroid cartilage fracture following a sneezing episode. The patient presented with odynophagia, dysphonia and neck pain.13 In our review of the literature, we found that only one other similar case has been reported. In that case, a patient experienced a feeling of a neck click, followed by neck pain and hoarseness. He sustained a fracture of the thyroid cartilage.14

In reviewing the hyperflexion mechanism, Lin et al1 noted that isolated thyroid cartilage fractures are rare and that "most of these are caused by direct injury to the neck, except for two patients reported in the literature who sustained isolated thyroid cartilage fractures after sneezing." Lin et al1 proposed an interesting hypothesis—that "the mechanism causing thyroid cartilage fracture during impaction may be the same with sneezing." Sneezing can be associated with sudden and forceful flexion of the neck.

It is certainly possible that this hyperflexion mechanism was involved in our case, given there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck, as in the sports-related injuries discussed. Wrestling holds can produce hyperflexion. The patient described a feeling of a "crack", which is similar to the clicking sound described in one of the sneezing-related cases. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is rare in the absence of major trauma. However, as noted by Rejali et al,9 this can create a potential management pitfall. "In the context of non-contact sports, the attendant doctor may not realize the significance of apparently minor head and neck trauma."9

There are no series data to provide us with an exact incidence of airway compromise. However, seemingly minor insults to the anterior neck can cause posterior compression of the larynx and can result in airway compromise.9-11

The CT scan is described as an important imaging modality to rule out cervical spine fracture. Although there was no significant blunt force, the cervical spine was exposed to hyperflexion forces. Another important potential consequence is long-term injury to the vocal cords, with subsequent speech difficulties.11 Computed tomography can visualize the thyroid fracture, but many authors point out that visualization of the vocal cords, with nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy or other modality, is an important adjunct to the CT scan.9-11

Otolaryngologist consultation should be strongly considered. This patient was transferred to a tertiary care center with expertise in thyroid fractures, and planned nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy to be performed at the receiving institution.

Conclusion

Our patient sustained an isolated thyroid cartilage fracture. Most blunt force laryngeal fractures are associated with multiple trauma. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture is very rare. An isolated thyroid cartilage fracture from a wrestling injury, especially in a non-sports competition context, such as horseplay, has not been previously reported in the literature. Symptoms can include neck pain, voice changes, pain with swallowing, and shortness of breath. Signs can include tenderness, ecchymosis, or even subcutaneous emphysema. There may be loss of the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, tracheal deviation, and stridor. Computed tomography scan imaging with 3-D reconstructions and laryngoscopy can be helpful in the diagnostic process. In our case, the patient sustained a thyroid cartilage fracture without the energy and force involved in a motor vehicle collision and without significant sports-related force. It is possible this injury may have involved neck hyperflexion, rather than direct compressive forces, similar to that described by Lin et al.1 Certainly, there was no history of significant blunt force to the neck on the level of the sports-related injuries discussed.

1. Lin HL, Kuo LC, Chen CW, Cheng YC, Lee WC. Neck hyperflexion causing isolated thyroid cartilage fracture--a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(9):1064.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.030

2. Kragha KO. Acute traumatic injury of the larynx. Case Reports in Otolaryngology. Volume 2015. Article ID393978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/393978

3. Kim JD, Shuler FD, Mo B, Gibbs SR, Belmaggio T, Giangarra CE. Traumatic laryngeal fracture in a collegiate basketball player. Sports Health. 2013;5(3):

273-275.

4. Knopke S, Todt I, Ernst A, Seidl RO. Pseudarthroses of the cornu of the thyroid cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(2):186-189. doi:10.1016/5.otohns.2010.04.011.

5. Walsh PV, Trotter GA. Fracture of the thyroid cartilage associated with full face integral crash helmet. Injury. 1979;11(1):47-48.

6. Tasca RA, Sherman IW, Wood GD. Thyroid cartilage fracture: treatment with biodegradable plates. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(2):159-160.

7. Mitrović SM. Blunt external laryngeal trauma. Two case reports. Med Pregl. 2007;60(9-10):489-492.

8. O'Keefe LJ, Maw AR. The dangers of minor blunt laryngeal trauma. J. Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(4):372-373.

9. Rejali SD, Bennett JD, Upile T, Rothera MP. Diagnostic pitfalls in sports related laryngeal injury. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(2):180-181.

10. Saab M, Birkinshaw R. Blunt laryngeal trauma: an unusual case. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51(8):527.

11. Pekcevik Y, Ibrahim C, Ülker C. Cricoid and thyroid cartilage fracture, cricothyroid joint dislocation,pseudofracture appearance of the hyoid bone: CT, MRI and laryngoscopic findings. JAEM. 2013;12:170-173.

12. Bent JP 3rd, Porubsky ES. The management of blunt fractures of the thyroid cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;110(2):195-202. doi: 10:.1177/019459989411000209.

13. Beato Martínez A, Moreno Juara A, López Moya JJ. Fracture of thyroid cartilage after a sneezing episode. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58(2):73-74.

14. Quinlan PT. Fracture of thyroid cartilage during a sneezing attack. Br Med J. 1950;1(4661):1052.

1. Lin HL, Kuo LC, Chen CW, Cheng YC, Lee WC. Neck hyperflexion causing isolated thyroid cartilage fracture--a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(9):1064.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.030

2. Kragha KO. Acute traumatic injury of the larynx. Case Reports in Otolaryngology. Volume 2015. Article ID393978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/393978

3. Kim JD, Shuler FD, Mo B, Gibbs SR, Belmaggio T, Giangarra CE. Traumatic laryngeal fracture in a collegiate basketball player. Sports Health. 2013;5(3):

273-275.

4. Knopke S, Todt I, Ernst A, Seidl RO. Pseudarthroses of the cornu of the thyroid cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(2):186-189. doi:10.1016/5.otohns.2010.04.011.

5. Walsh PV, Trotter GA. Fracture of the thyroid cartilage associated with full face integral crash helmet. Injury. 1979;11(1):47-48.

6. Tasca RA, Sherman IW, Wood GD. Thyroid cartilage fracture: treatment with biodegradable plates. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(2):159-160.

7. Mitrović SM. Blunt external laryngeal trauma. Two case reports. Med Pregl. 2007;60(9-10):489-492.

8. O'Keefe LJ, Maw AR. The dangers of minor blunt laryngeal trauma. J. Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(4):372-373.