User login

Rapid Development of Perifolliculitis Following Mesotherapy

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

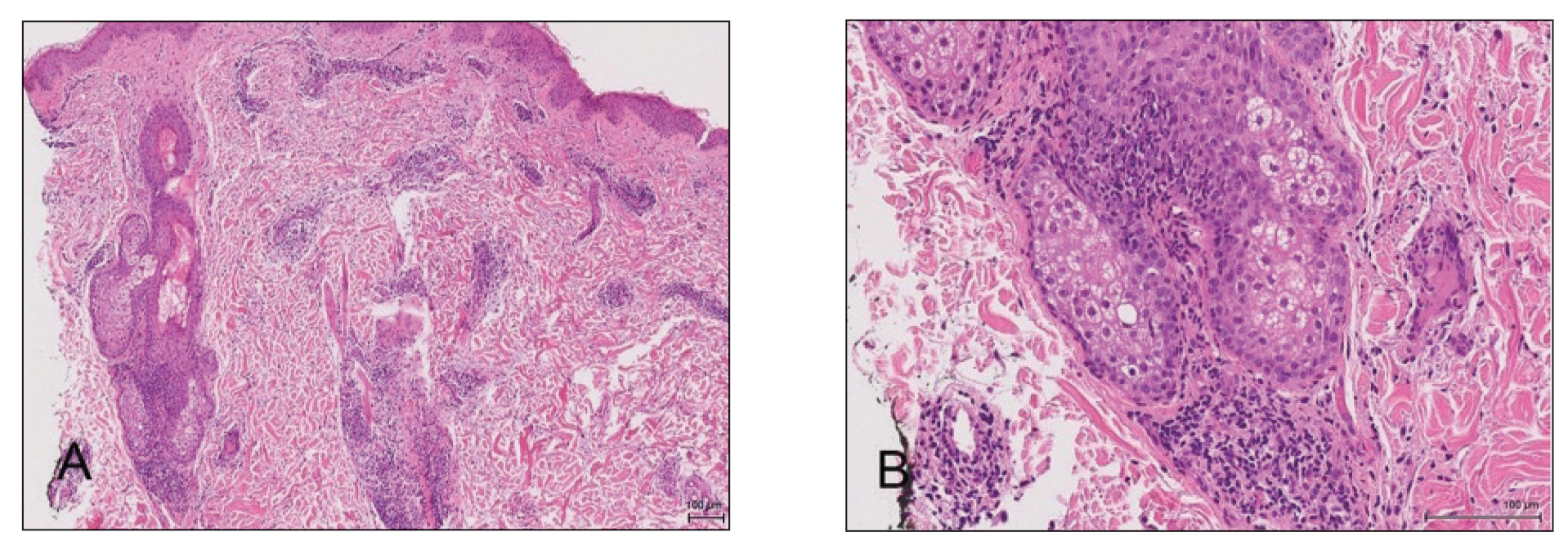

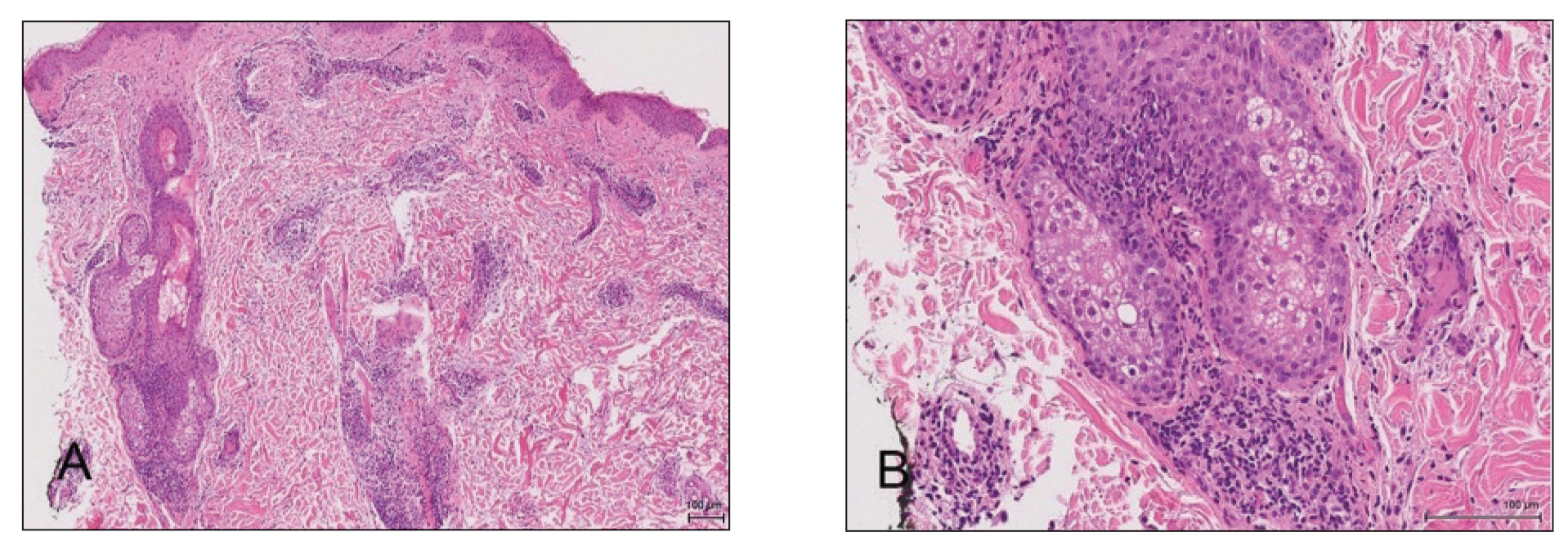

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

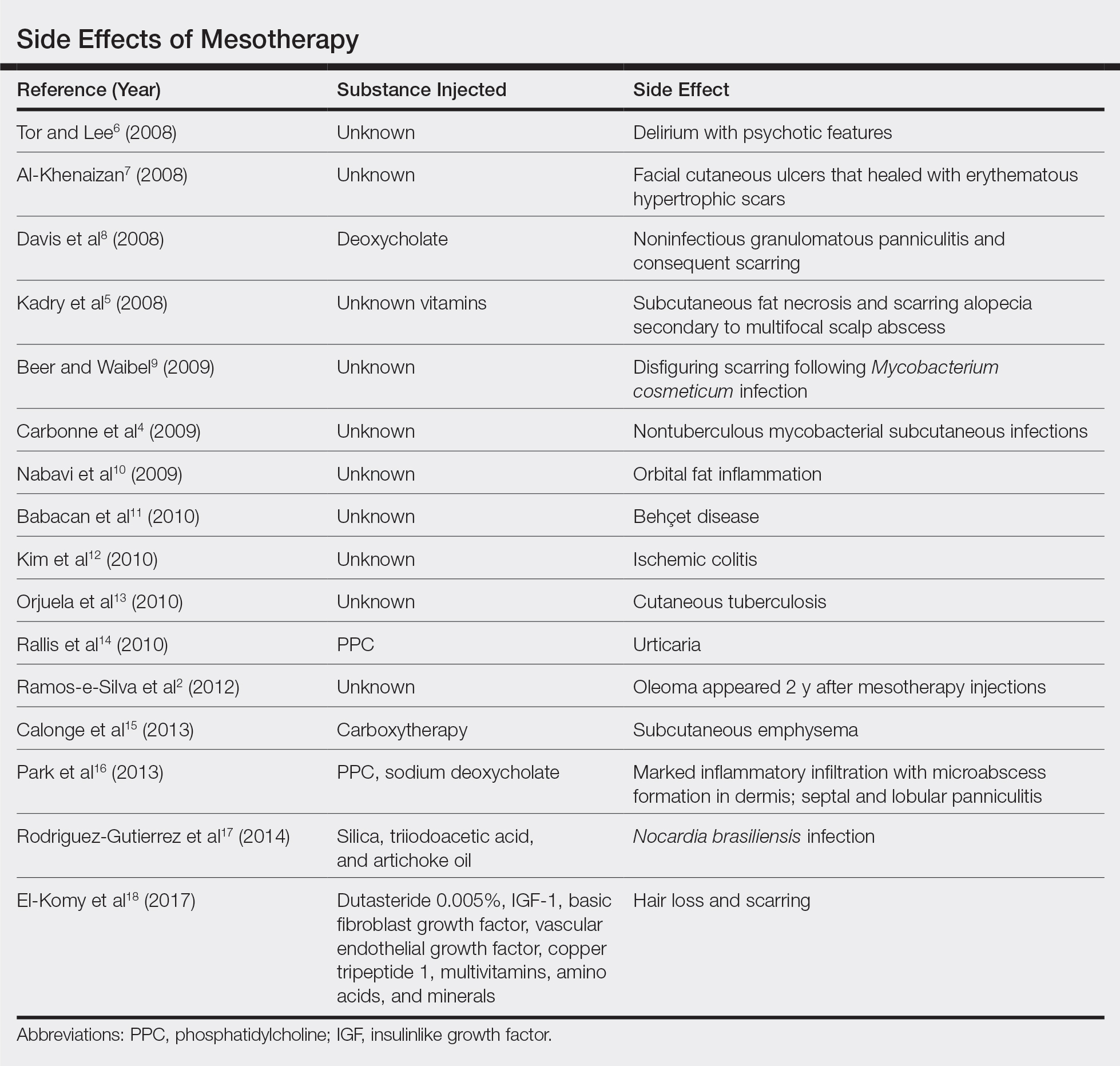

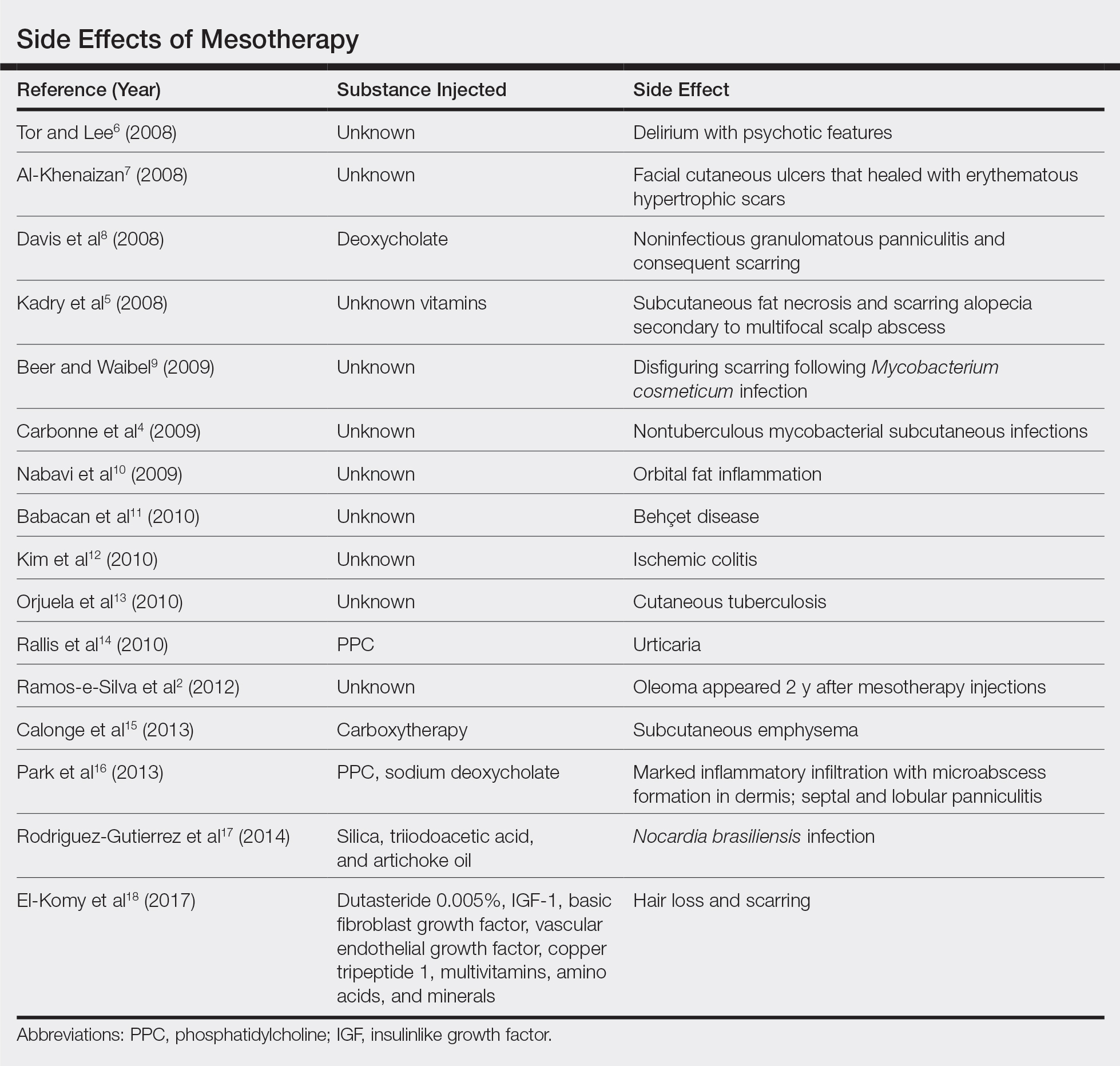

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

Practice Points

- Mesotherapy—the delivery of vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts directly into the dermis via injections—is a common procedure performed in both medical and nonmedical settings for cosmetic rejuvenation.

- Complications can occur from mesotherapy treatment.

- Patients should be advised to seek medical care with US Food and Drug Administration–approved cosmetic techniques and substances only

Multiple Eruptive Syringomas on the Penis

To the Editor:

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

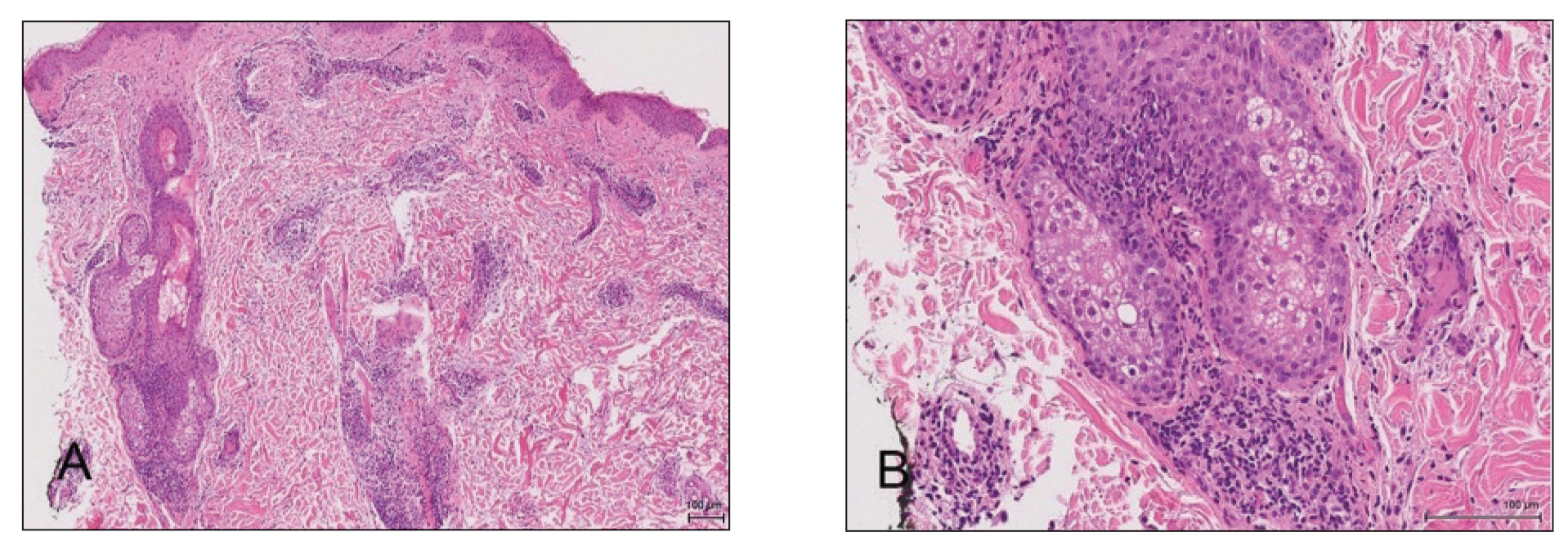

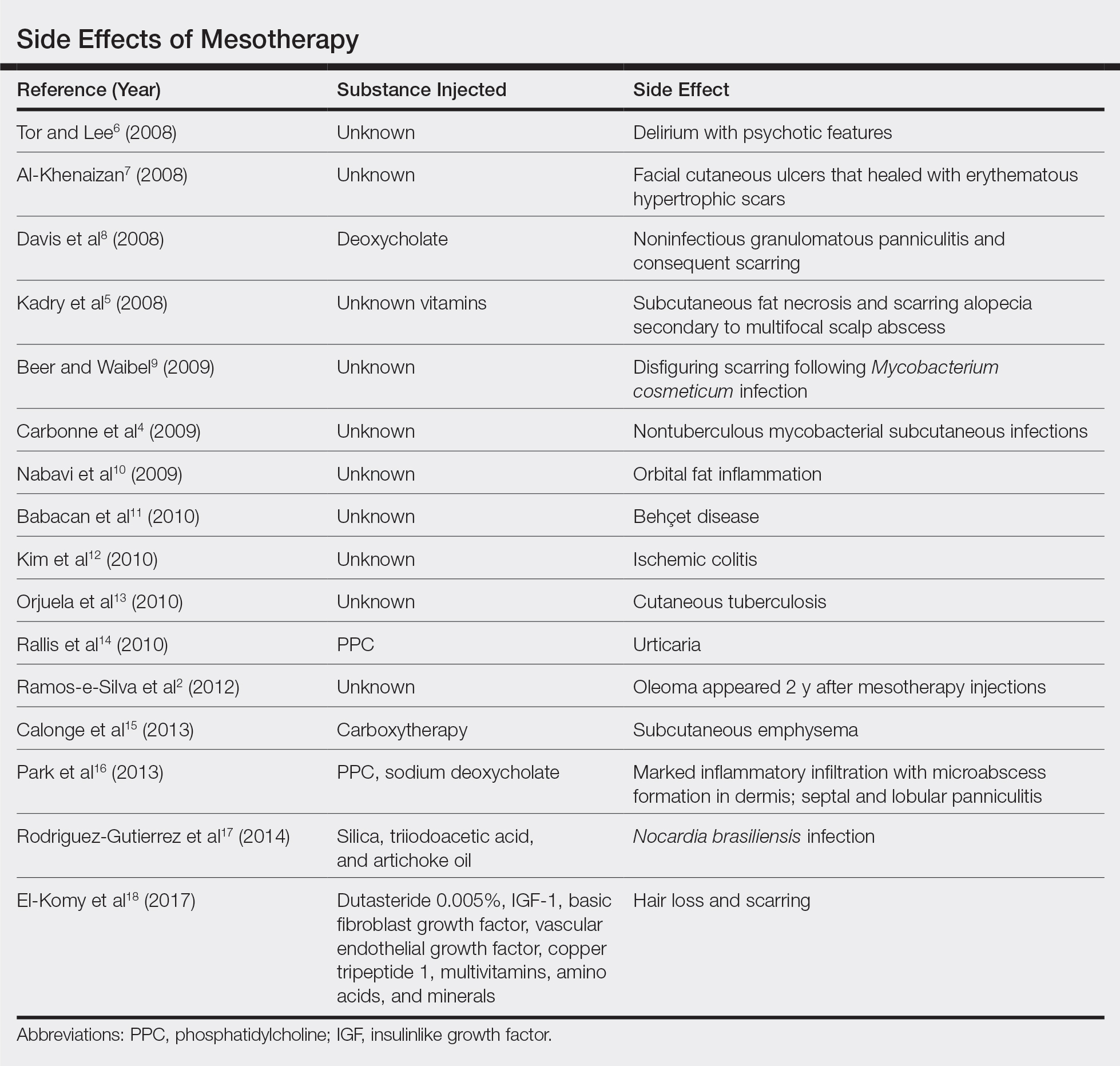

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

Practice Points

- Penile syringoma can mimic sexually transmitted disease such as condyloma acuminatum or molluscum contagiosum.

- Penile syringomas can be long-standing and require biopsy to differentiate from other conditions.