User login

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Overlap Syndrome in a Patient With Relapsing Polychondritis

To the Editor:

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a chronic, progressive, and episodic systemic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the cartilaginous structures of the ears and nose. Involvement of other proteoglycan-rich structures such as the joints, eyes, inner ears, blood vessels, heart, and kidneys also may be seen. Dermatologic manifestations occur in 35% to 50% of patients and may be the presenting sign in up to 12% of cases.1 The most commonly reported dermatologic findings include oral aphthosis, erythema nodosum, and purpura with vasculitic changes. Less commonly reported associations include Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, erythema annulare centrifugum, and erythema multiforme.1

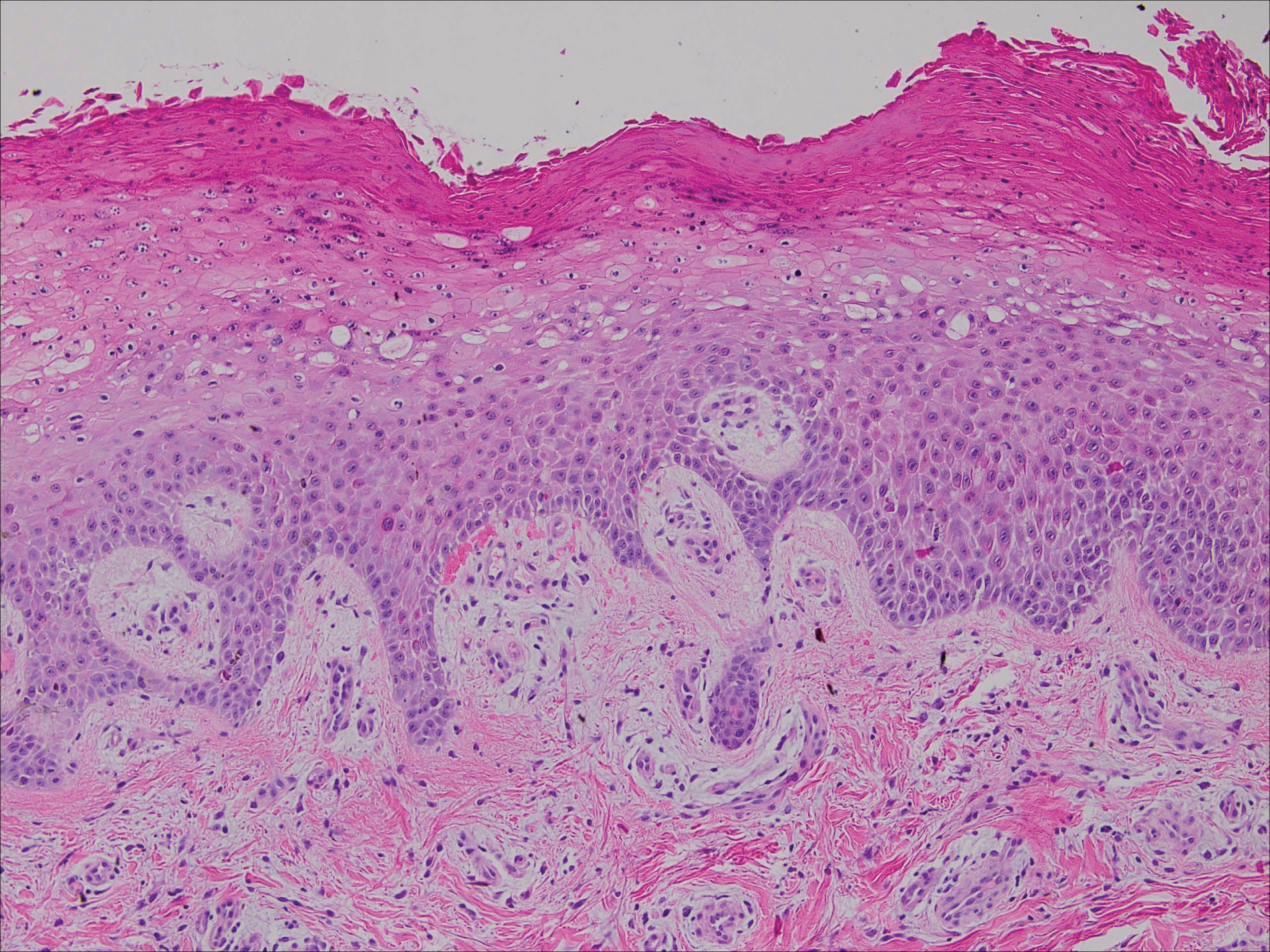

A 43-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy developed new-onset tenderness and swelling of the left pinna while on vacation. She was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and levofloxacin for presumed auricular cellulitis. The patient developed a fever; sore throat; and a progressive, pruritic, blistering rash on the face, torso, bilateral extremities, palms, and soles 1 day after completing the antibiotic course. After 5 days of unremitting symptoms despite oral, intramuscular, and topical steroids, the patient presented to the emergency department. Physical examination revealed diffuse, tender, erythematous to violaceous macules with varying degrees of coalescence on the chest, back, and extremities. Scattered flaccid bullae and erosions of the oral and genital mucosa also were seen. Laboratory analysis was notable only for a urinary tract infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae. A punch biopsy demonstrated full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis with subepidermal bullae and a mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils, consistent with a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Because of the body surface area involved (20%) and the recent history of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole use, a diagnosis of SJS/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) overlap syndrome was made. The patient was successfully treated with subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg), supportive care, and cephalexin for the urinary tract infection.

Approximately 5 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the patient was evaluated for new-onset pain and swelling of the right ear (Figure) in conjunction with recent tenderness and depression of the superior septal structure of the nose. A punch biopsy of the ear revealed mild perichondral inflammation without vasculitic changes and a superficial, deep perivascular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with scattered eosinophils. A diagnosis of RP was made, as the patient met Damiani and Levine’s2 criteria with bilateral auricular inflammation, ocular inflammation, and nasal chondritis.

Although the exact pathogenesis of RP remains unclear, there is strong evidence to suggest an underlying autoimmune etiology.3 Autoantibodies against type II collagen, in addition to other minor collagen and cartilage proteins, such as cartilage oligomeric matrix proteins and matrilin-1, are seen in a subset of patients. Titers have been reported to correlate with disease activity.3,4 Direct immunofluorescence also has demonstrated plentiful CD4+ T cells, as well as IgM, IgA, IgG, and C3 deposits in the inflamed cartilage of patients with RP.3 Additionally, approximately 30% of patients with RP will have another autoimmune disease, and more than 50% of patients with RP carry the HLA-DR4 antigen.3 Alternatively, SJS and TEN are not reported in association with autoimmune diseases and are believed to be CD8+ T-cell driven. Some HLA-B subtypes have been found in strong association with SJS and TEN, suggesting the role of a potential genetic susceptibility.5

We report a unique case of SJS/TEN overlap syndrome occurring in a patient with RP.1 Although the association may be coincidental, it is well known that patients with lupus erythematosus are predisposed to the development of SJS and TEN. Therefore, a shared underlying genetic predisposition or immune system hyperactivity secondary to active RP is a possible explanation for our patient’s unique presentation.

- Watkins S, Magill JM Jr, Ramos-Caro FA. Annular eruption preceding relapsing polychondritis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:356-362.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis—report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-46.

- Puéchal X, Terrier B, Mouthon L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:118-24.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Harr T, French L. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;16;5:39.

To the Editor:

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a chronic, progressive, and episodic systemic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the cartilaginous structures of the ears and nose. Involvement of other proteoglycan-rich structures such as the joints, eyes, inner ears, blood vessels, heart, and kidneys also may be seen. Dermatologic manifestations occur in 35% to 50% of patients and may be the presenting sign in up to 12% of cases.1 The most commonly reported dermatologic findings include oral aphthosis, erythema nodosum, and purpura with vasculitic changes. Less commonly reported associations include Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, erythema annulare centrifugum, and erythema multiforme.1

A 43-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy developed new-onset tenderness and swelling of the left pinna while on vacation. She was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and levofloxacin for presumed auricular cellulitis. The patient developed a fever; sore throat; and a progressive, pruritic, blistering rash on the face, torso, bilateral extremities, palms, and soles 1 day after completing the antibiotic course. After 5 days of unremitting symptoms despite oral, intramuscular, and topical steroids, the patient presented to the emergency department. Physical examination revealed diffuse, tender, erythematous to violaceous macules with varying degrees of coalescence on the chest, back, and extremities. Scattered flaccid bullae and erosions of the oral and genital mucosa also were seen. Laboratory analysis was notable only for a urinary tract infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae. A punch biopsy demonstrated full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis with subepidermal bullae and a mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils, consistent with a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Because of the body surface area involved (20%) and the recent history of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole use, a diagnosis of SJS/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) overlap syndrome was made. The patient was successfully treated with subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg), supportive care, and cephalexin for the urinary tract infection.

Approximately 5 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the patient was evaluated for new-onset pain and swelling of the right ear (Figure) in conjunction with recent tenderness and depression of the superior septal structure of the nose. A punch biopsy of the ear revealed mild perichondral inflammation without vasculitic changes and a superficial, deep perivascular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with scattered eosinophils. A diagnosis of RP was made, as the patient met Damiani and Levine’s2 criteria with bilateral auricular inflammation, ocular inflammation, and nasal chondritis.

Although the exact pathogenesis of RP remains unclear, there is strong evidence to suggest an underlying autoimmune etiology.3 Autoantibodies against type II collagen, in addition to other minor collagen and cartilage proteins, such as cartilage oligomeric matrix proteins and matrilin-1, are seen in a subset of patients. Titers have been reported to correlate with disease activity.3,4 Direct immunofluorescence also has demonstrated plentiful CD4+ T cells, as well as IgM, IgA, IgG, and C3 deposits in the inflamed cartilage of patients with RP.3 Additionally, approximately 30% of patients with RP will have another autoimmune disease, and more than 50% of patients with RP carry the HLA-DR4 antigen.3 Alternatively, SJS and TEN are not reported in association with autoimmune diseases and are believed to be CD8+ T-cell driven. Some HLA-B subtypes have been found in strong association with SJS and TEN, suggesting the role of a potential genetic susceptibility.5

We report a unique case of SJS/TEN overlap syndrome occurring in a patient with RP.1 Although the association may be coincidental, it is well known that patients with lupus erythematosus are predisposed to the development of SJS and TEN. Therefore, a shared underlying genetic predisposition or immune system hyperactivity secondary to active RP is a possible explanation for our patient’s unique presentation.

To the Editor:

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a chronic, progressive, and episodic systemic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the cartilaginous structures of the ears and nose. Involvement of other proteoglycan-rich structures such as the joints, eyes, inner ears, blood vessels, heart, and kidneys also may be seen. Dermatologic manifestations occur in 35% to 50% of patients and may be the presenting sign in up to 12% of cases.1 The most commonly reported dermatologic findings include oral aphthosis, erythema nodosum, and purpura with vasculitic changes. Less commonly reported associations include Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, erythema annulare centrifugum, and erythema multiforme.1

A 43-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy developed new-onset tenderness and swelling of the left pinna while on vacation. She was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and levofloxacin for presumed auricular cellulitis. The patient developed a fever; sore throat; and a progressive, pruritic, blistering rash on the face, torso, bilateral extremities, palms, and soles 1 day after completing the antibiotic course. After 5 days of unremitting symptoms despite oral, intramuscular, and topical steroids, the patient presented to the emergency department. Physical examination revealed diffuse, tender, erythematous to violaceous macules with varying degrees of coalescence on the chest, back, and extremities. Scattered flaccid bullae and erosions of the oral and genital mucosa also were seen. Laboratory analysis was notable only for a urinary tract infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae. A punch biopsy demonstrated full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis with subepidermal bullae and a mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils, consistent with a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Because of the body surface area involved (20%) and the recent history of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole use, a diagnosis of SJS/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) overlap syndrome was made. The patient was successfully treated with subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg), supportive care, and cephalexin for the urinary tract infection.

Approximately 5 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the patient was evaluated for new-onset pain and swelling of the right ear (Figure) in conjunction with recent tenderness and depression of the superior septal structure of the nose. A punch biopsy of the ear revealed mild perichondral inflammation without vasculitic changes and a superficial, deep perivascular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with scattered eosinophils. A diagnosis of RP was made, as the patient met Damiani and Levine’s2 criteria with bilateral auricular inflammation, ocular inflammation, and nasal chondritis.

Although the exact pathogenesis of RP remains unclear, there is strong evidence to suggest an underlying autoimmune etiology.3 Autoantibodies against type II collagen, in addition to other minor collagen and cartilage proteins, such as cartilage oligomeric matrix proteins and matrilin-1, are seen in a subset of patients. Titers have been reported to correlate with disease activity.3,4 Direct immunofluorescence also has demonstrated plentiful CD4+ T cells, as well as IgM, IgA, IgG, and C3 deposits in the inflamed cartilage of patients with RP.3 Additionally, approximately 30% of patients with RP will have another autoimmune disease, and more than 50% of patients with RP carry the HLA-DR4 antigen.3 Alternatively, SJS and TEN are not reported in association with autoimmune diseases and are believed to be CD8+ T-cell driven. Some HLA-B subtypes have been found in strong association with SJS and TEN, suggesting the role of a potential genetic susceptibility.5

We report a unique case of SJS/TEN overlap syndrome occurring in a patient with RP.1 Although the association may be coincidental, it is well known that patients with lupus erythematosus are predisposed to the development of SJS and TEN. Therefore, a shared underlying genetic predisposition or immune system hyperactivity secondary to active RP is a possible explanation for our patient’s unique presentation.

- Watkins S, Magill JM Jr, Ramos-Caro FA. Annular eruption preceding relapsing polychondritis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:356-362.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis—report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-46.

- Puéchal X, Terrier B, Mouthon L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:118-24.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Harr T, French L. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;16;5:39.

- Watkins S, Magill JM Jr, Ramos-Caro FA. Annular eruption preceding relapsing polychondritis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:356-362.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis—report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-46.

- Puéchal X, Terrier B, Mouthon L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:118-24.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Harr T, French L. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;16;5:39.

Practice Points

- The clinical presentation of relapsing polychondritis (RP) may demonstrate cutaneous manifestations other than the typical inflammation of cartilage-rich structures.

- Approximately 30% of patients with RP will have another autoimmune disease.

Residency Training During the #MeToo Movement

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

Paraneoplastic Dermatomyositis Presenting With Interesting Cutaneous Findings

To the Editor:

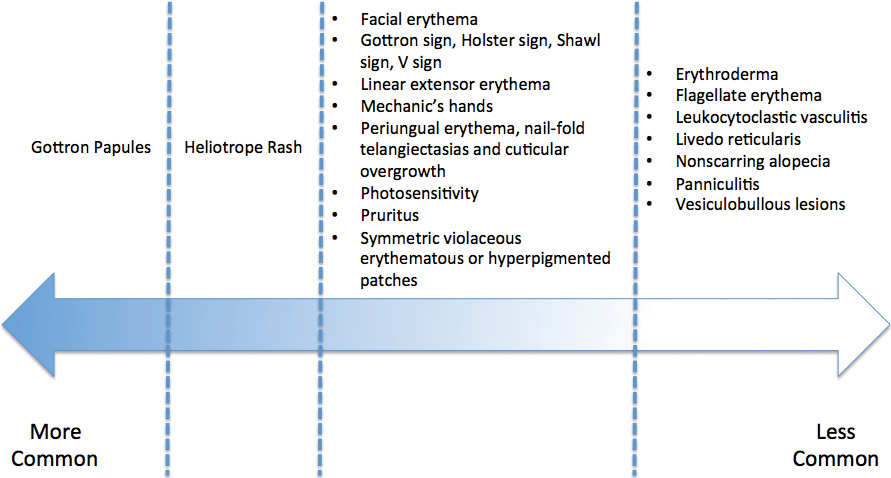

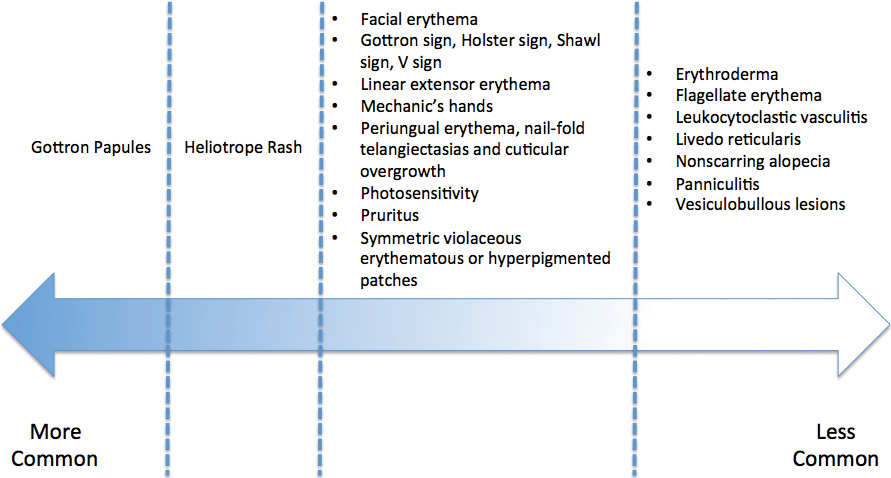

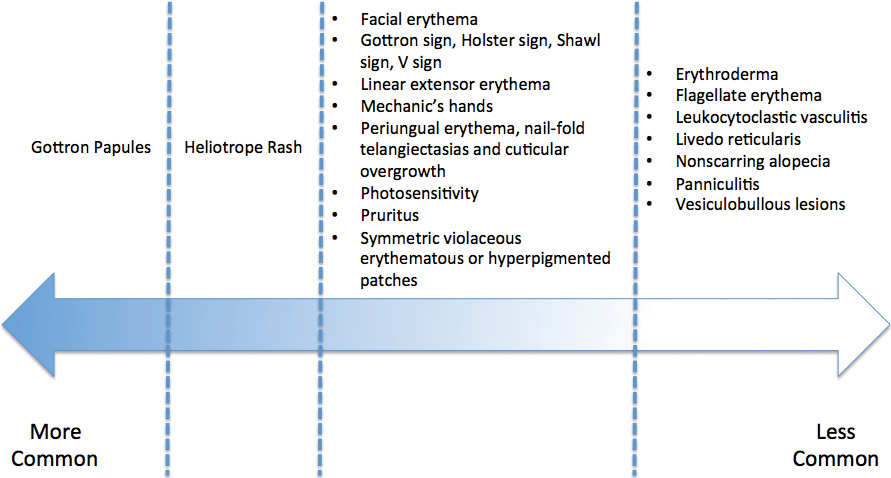

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

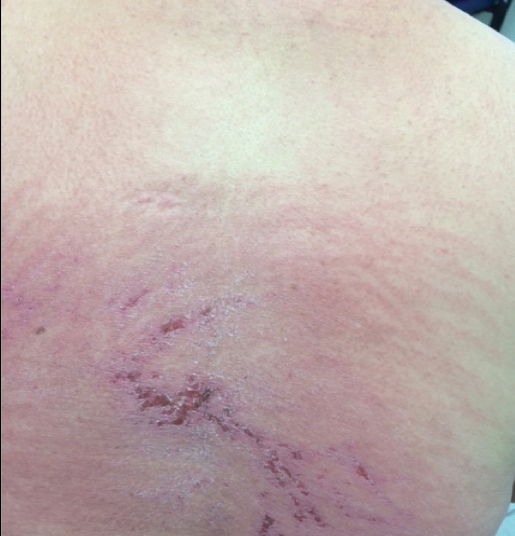

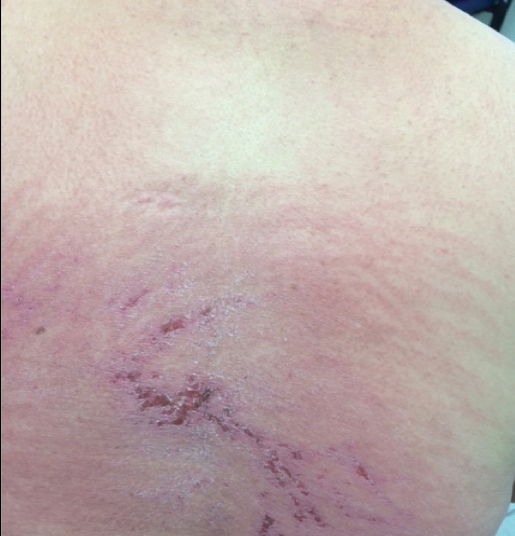

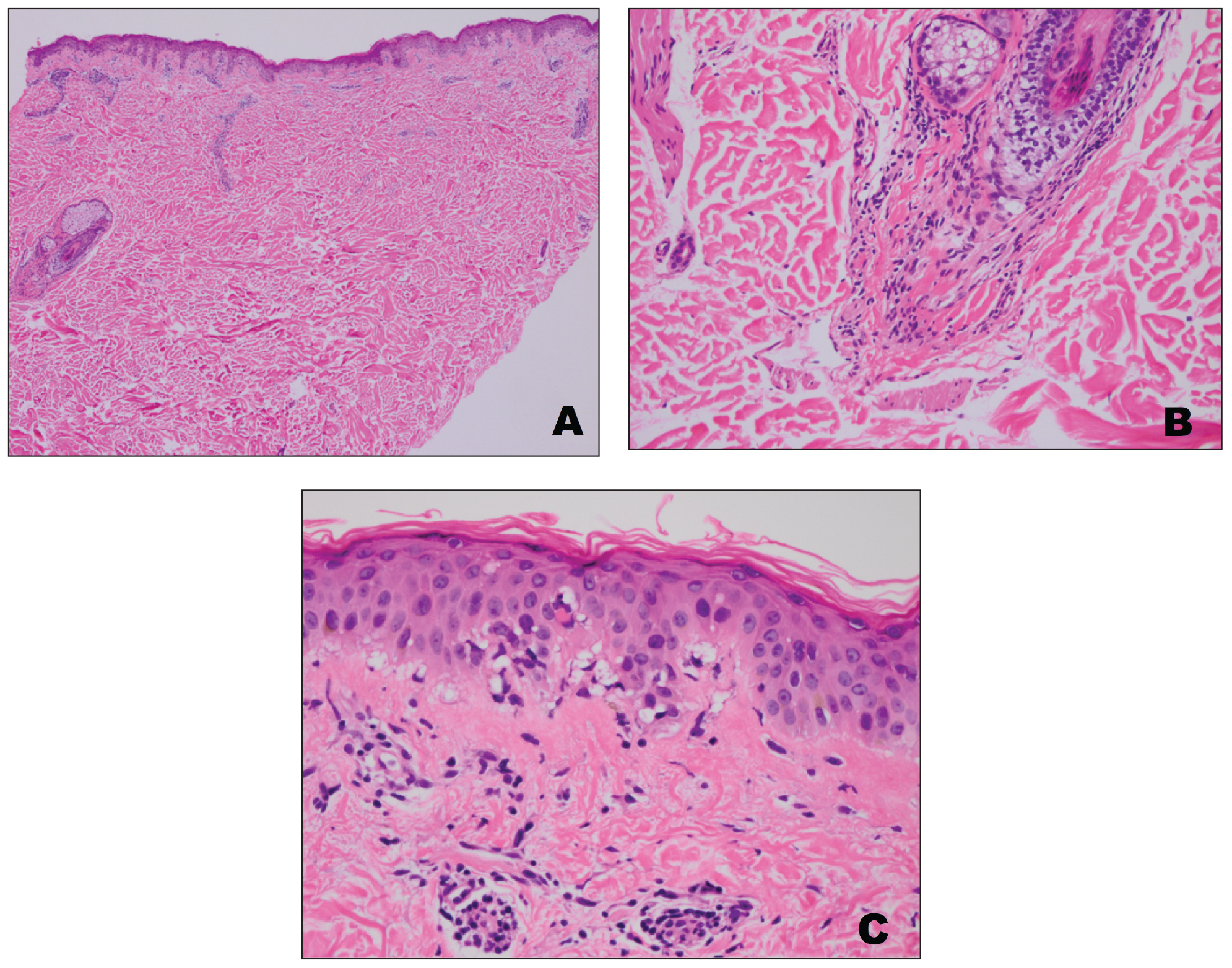

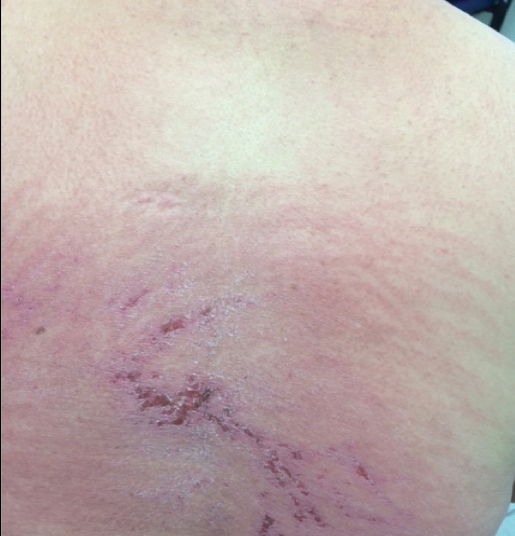

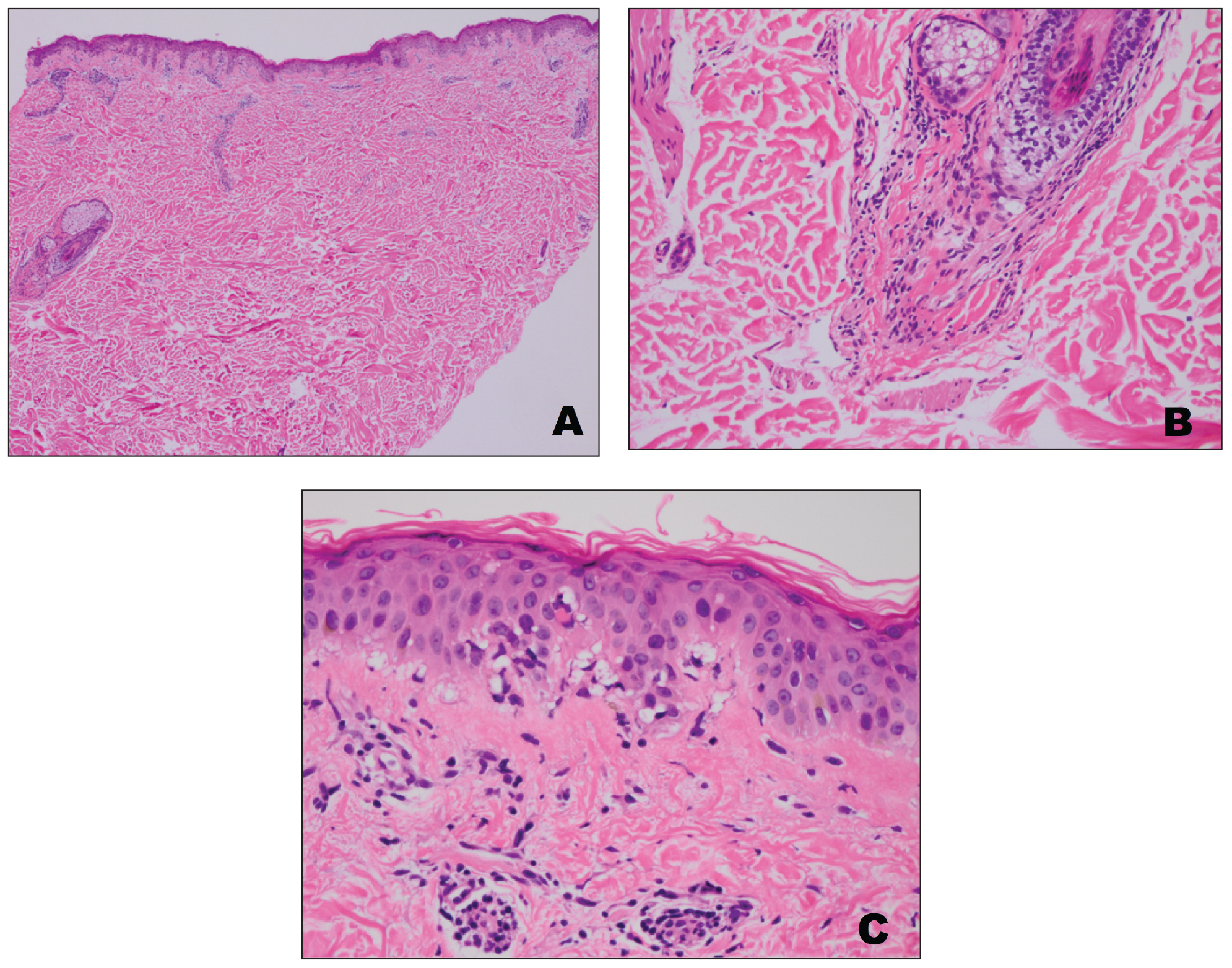

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

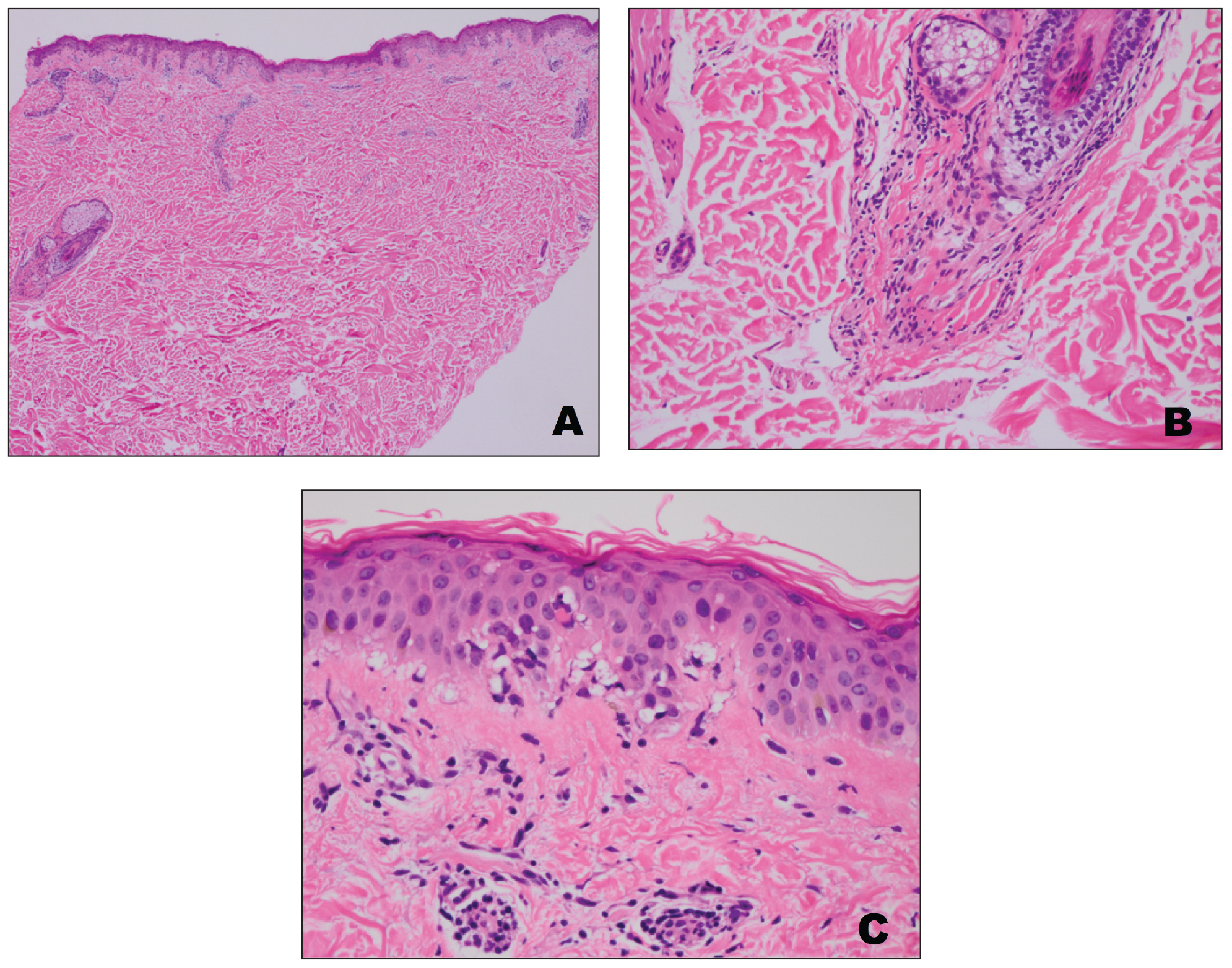

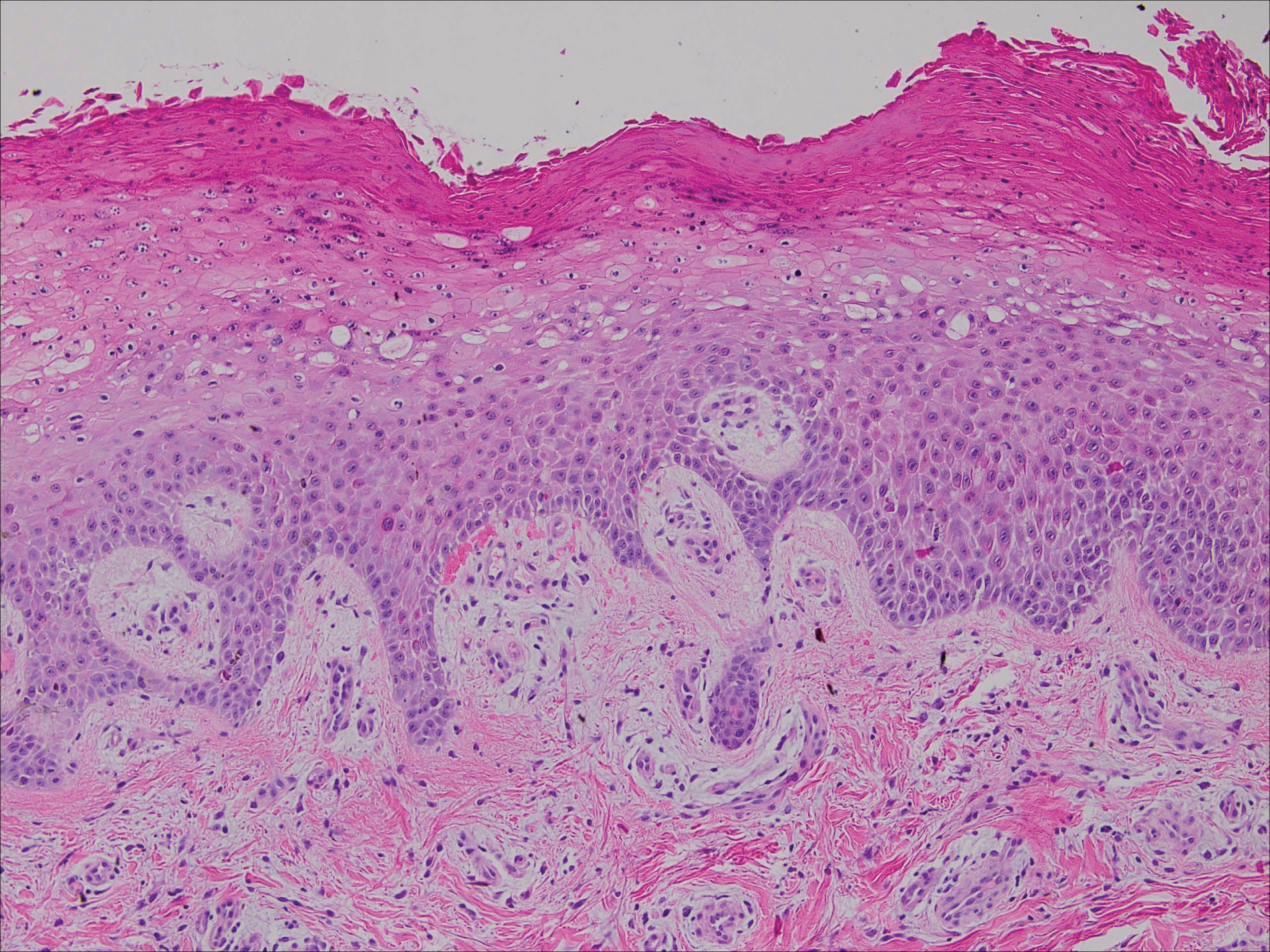

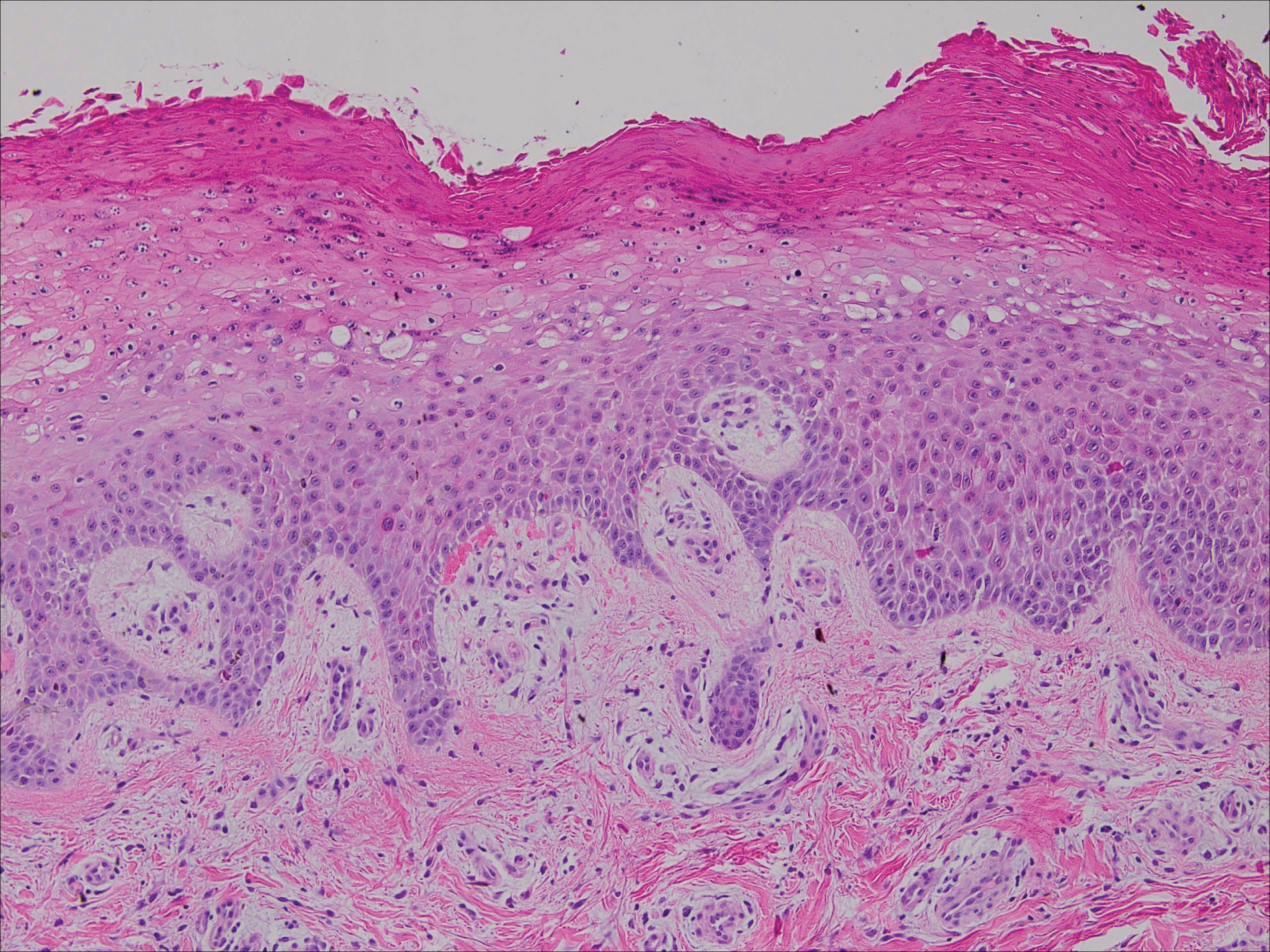

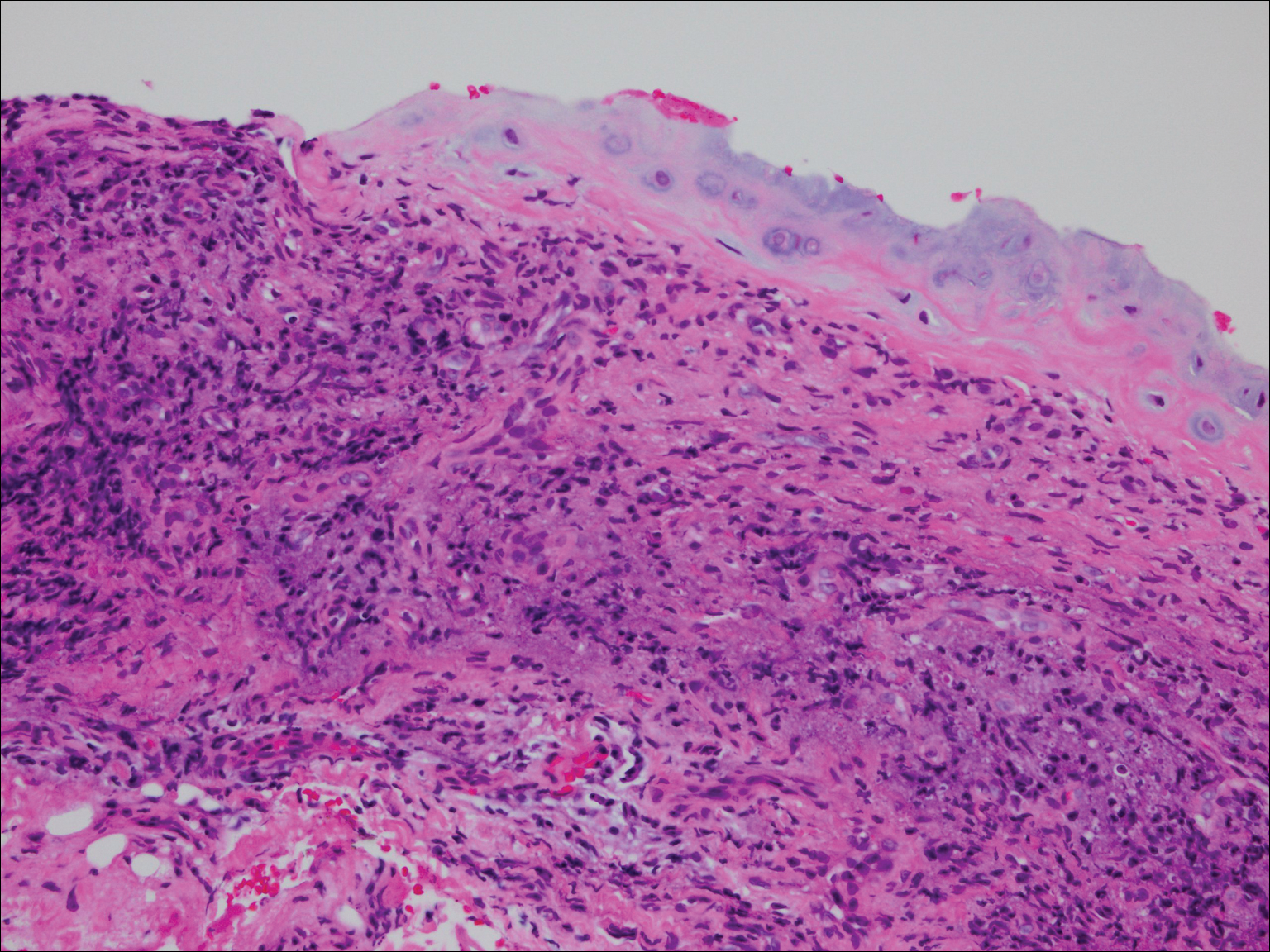

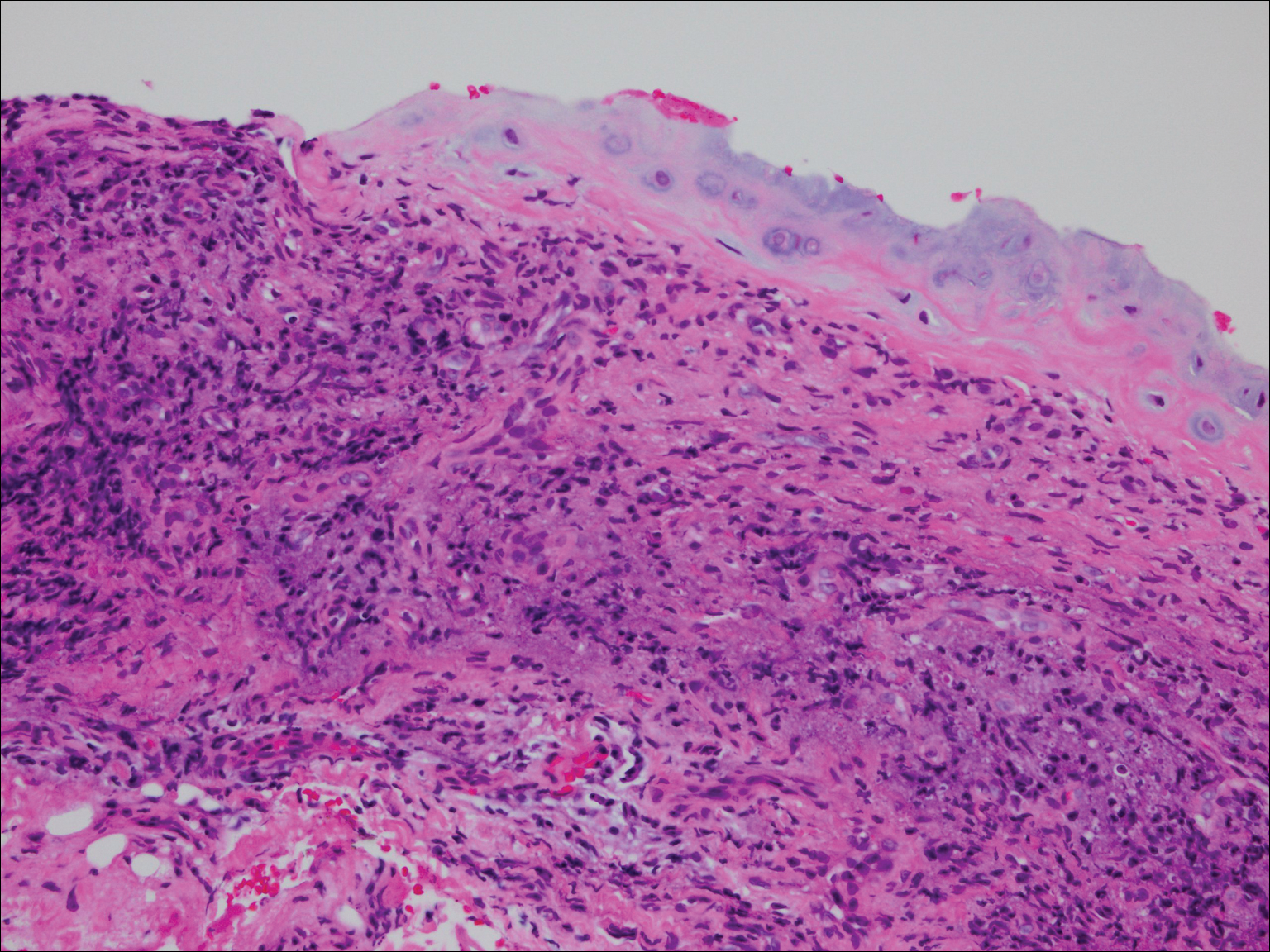

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

To the Editor:

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

We report an interesting clinical case of dermatomyositis (DM) that presented with an associated malignancy (small cell lung cancer). This patient also had an unusual clinical finding of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a cutaneous sign that is seldom described in the DM literature. This case serves to reinforce the classic findings and associations of DM, in addition to the uncommon manifestation of predominantly unilateral papules on the knee.

A 68-year-old woman presented with several cutaneous manifestations including the classic findings of photo distributed erythema on the arms and face, a heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and confluent pink papules on the left knee (Figure 1). The patient also had one of the more rare manifestations of DM, flagellate erythema on the back (Figure 2). She had a history of breast cancer and was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer at the time of the DM diagnosis.

A punch biopsy from an area of flagellate erythema on the back revealed an interface dermatitis with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Alcian blue and colloidal iron stains revealed a marked increase in papillary dermal mucin. With the characteristic changes on skin biopsy and the classic skin findings present in our patient, we felt confident diagnosing her with DM. At the time of diagnosis, the patient also was found to have metastatic small cell lung cancer, suggesting a true paraneoplastic relationship.

The association of DM and amyopathic DM with internal malignancy is well known. Bohan and Peter1 noted an overall figure ranging from 15% to 34% with an increased frequency in patients with skin and muscle involvement.1 Hill et al5 examined this link in a population-based study that identified corresponding malignancies. Specifically, they noted cancers to arise most frequently in the airway (eg, lung, trachea, bronchus), ovaries, breasts, colorectal region, and stomach.5 There also has been work performed to identify if certain dermatologic findings may be associated with a higher risk of malignancy.6,7 A meta-analysis by Wang et al6 showed that Gottron sign did not have an association with cancer, but findings of cutaneous necrosis did have an association. It is unknown if the specific cutaneous findings in our patient, including the predominantly unilateral papules on the knee, may have been a clue to the underlying malignancy.

In summary, we believe that our patient presented with the classic manifestations of DM in addition to the curious cutaneous sign of predominantly unilateral, confluent, erythematous papules on the knee, a clinical finding that may aid in the diagnosis of DM and also may alert the clinician to a possible underlying malignancy.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger B, Dugan EM. Skin involvement in dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:714-722.

- Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53-57.

- Lister RK, Cooper ES, Paige DG. Papules and pustules of the elbows and knees: an uncommon clinical sign of dermatomyositis in oriental children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:37-40.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta‐analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831.

Practice Points

- Dermatomyositis has myriad cutaneous features including the shawl sign, the heliotrope sign, and Gottron papules.

- Less commonly, patients can present with the Holster sign (poikiloderma of the lateral thighs).

- Even less commonly, as in this report, patients can present with a psoriasiform papular eruption on the knees or with flagellate erythema on the back.

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in a Patient With Short Bowel Syndrome

To the Editor:

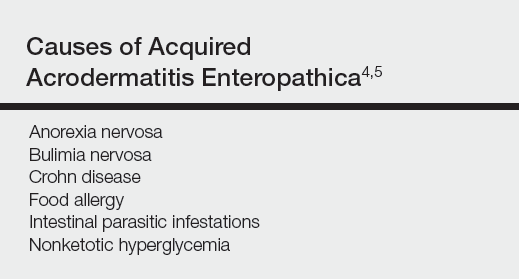

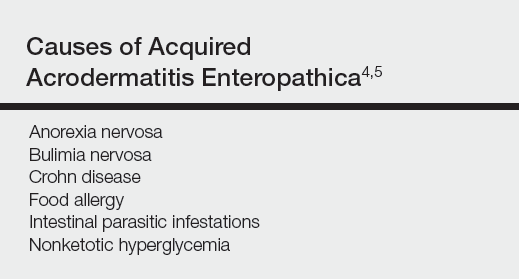

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

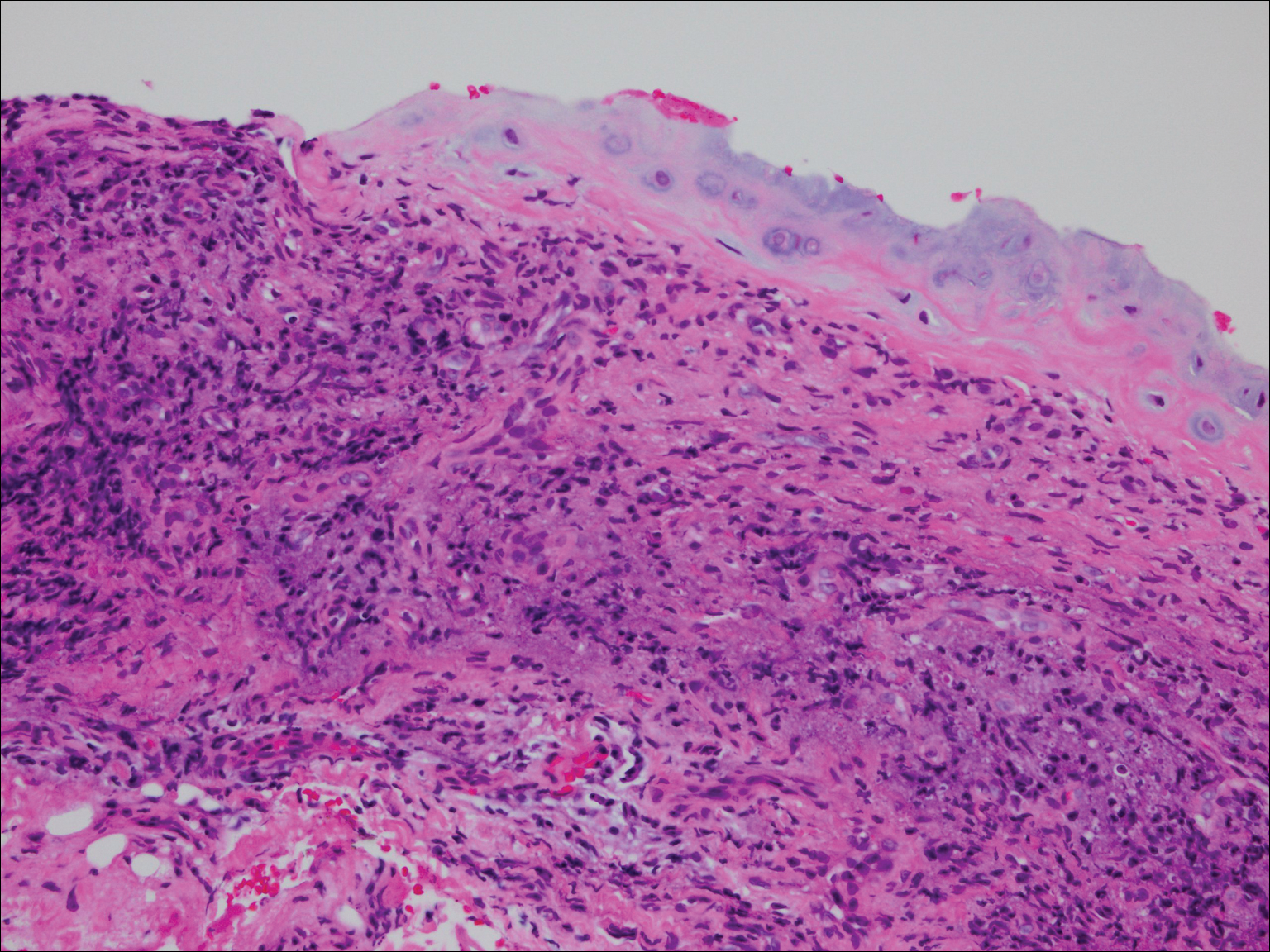

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be a manifestation of zinc deficiency.

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica should be considered in patients with poor intestinal absorption of nutrients.

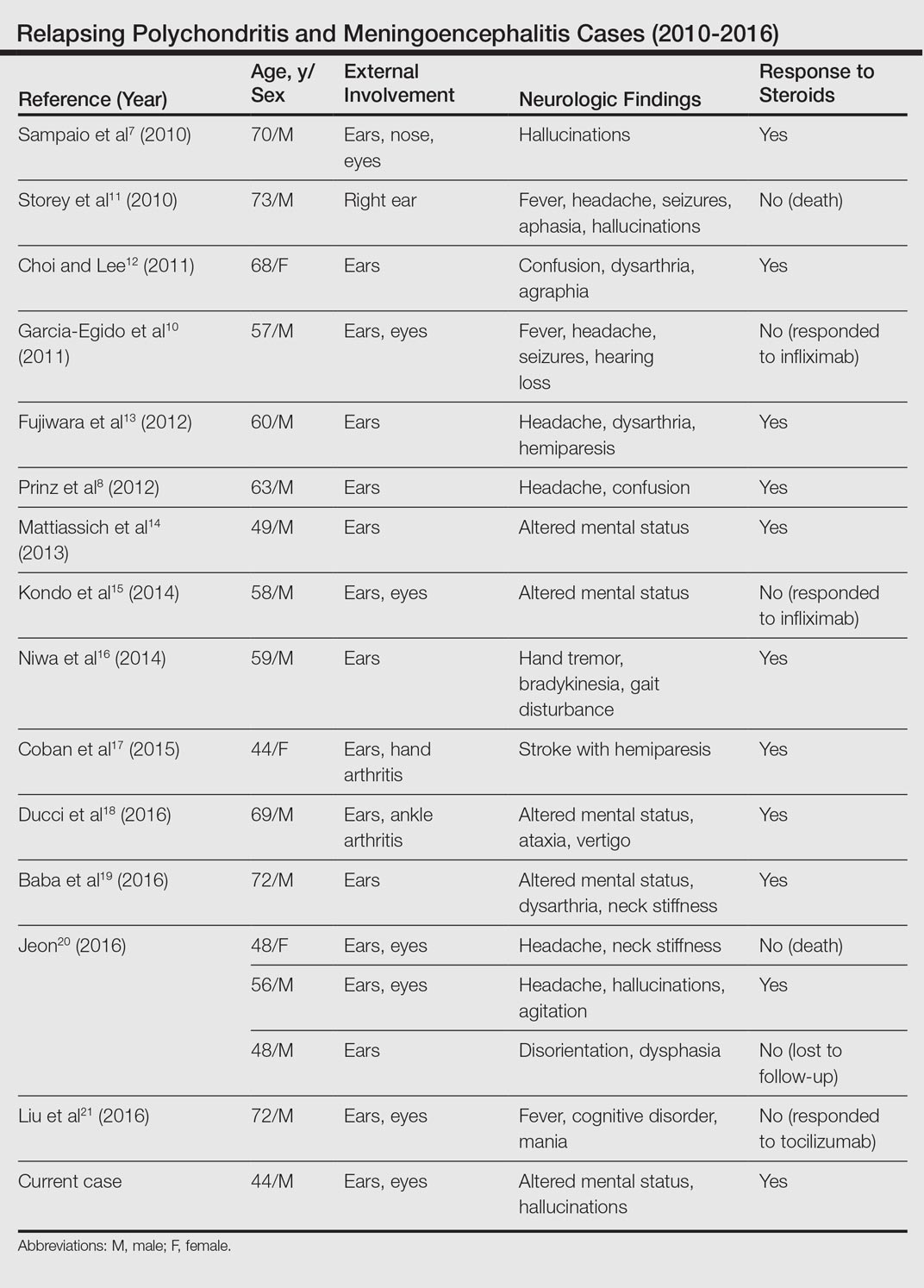

Relapsing Polychondritis With Meningoencephalitis

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report