User login

Management of Psoriasis With Topicals: Applying the 2020 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care to Clinical Practice

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythematous scaly plaques that can invoke substantial pain, pruritus, and quality-of-life disturbance in patients. Topical therapies are the most commonly used medications for treating psoriasis, with one study (N = 128,308) showing that more than 85% of patients with psoriasis were managed solely with topical medications. 1 For patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical agents alone may be able to control disease completely. For those with more severe disease, topical agents are used adjunctively with systemic or biologic agents to optimize disease control in localized areas.

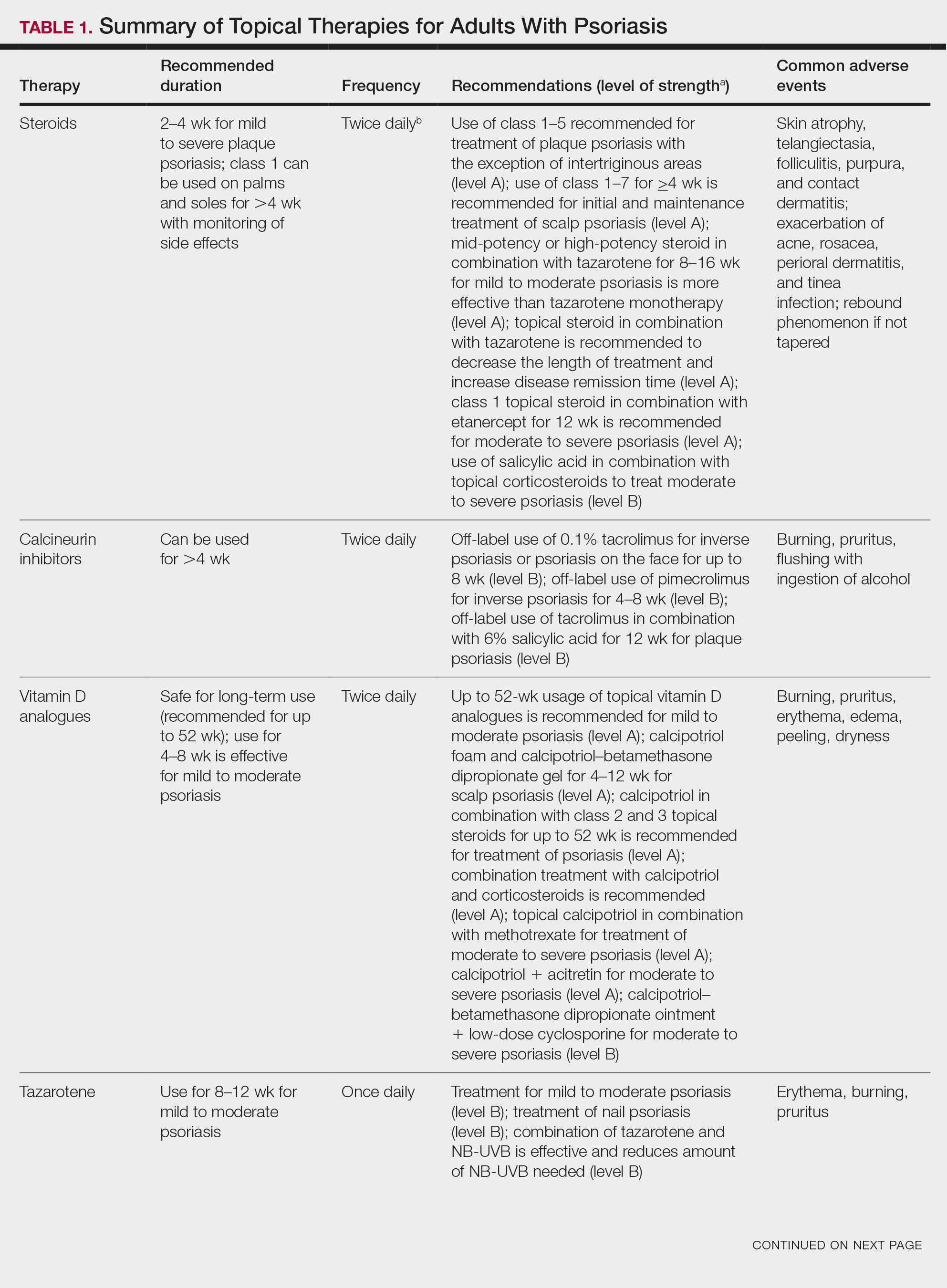

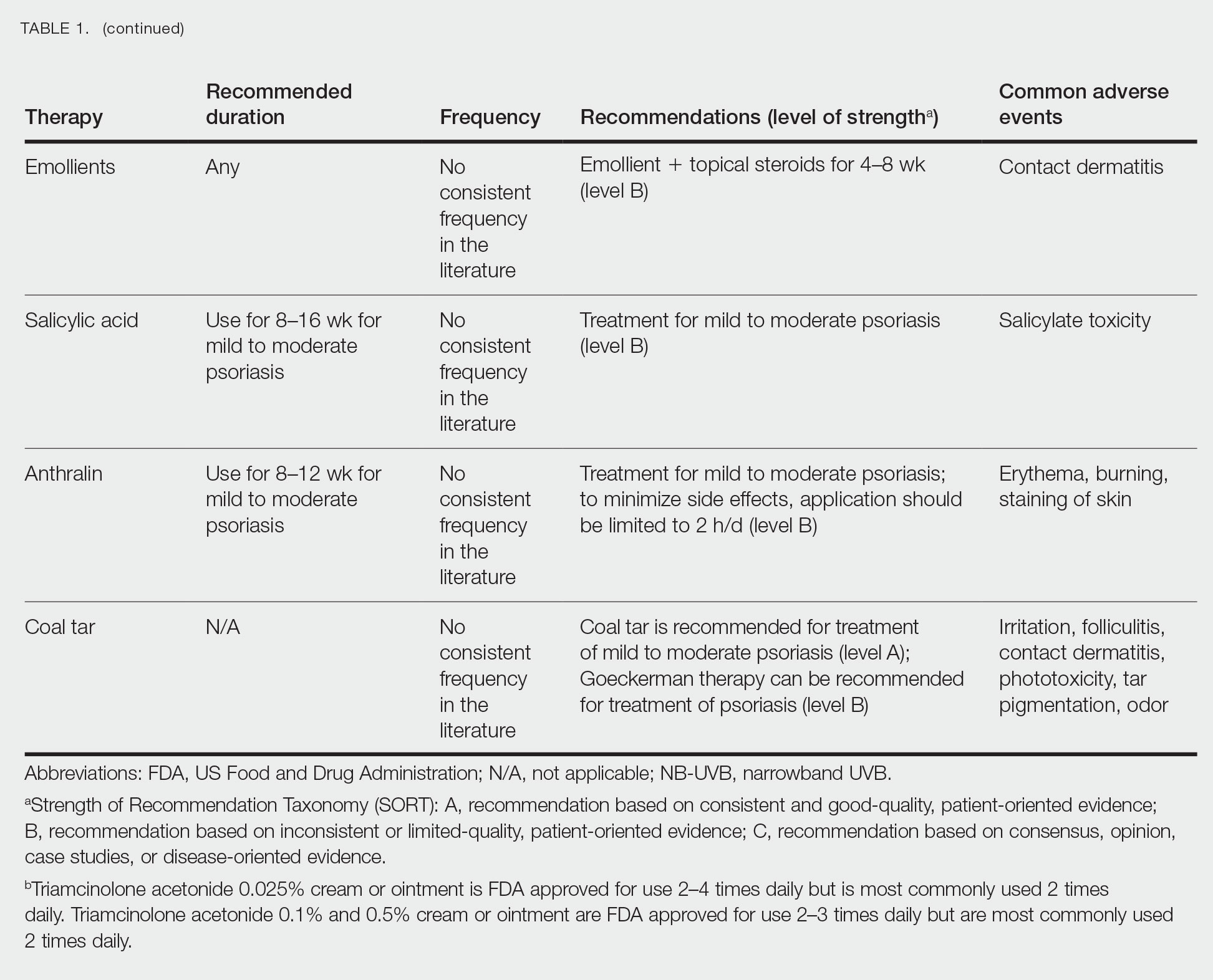

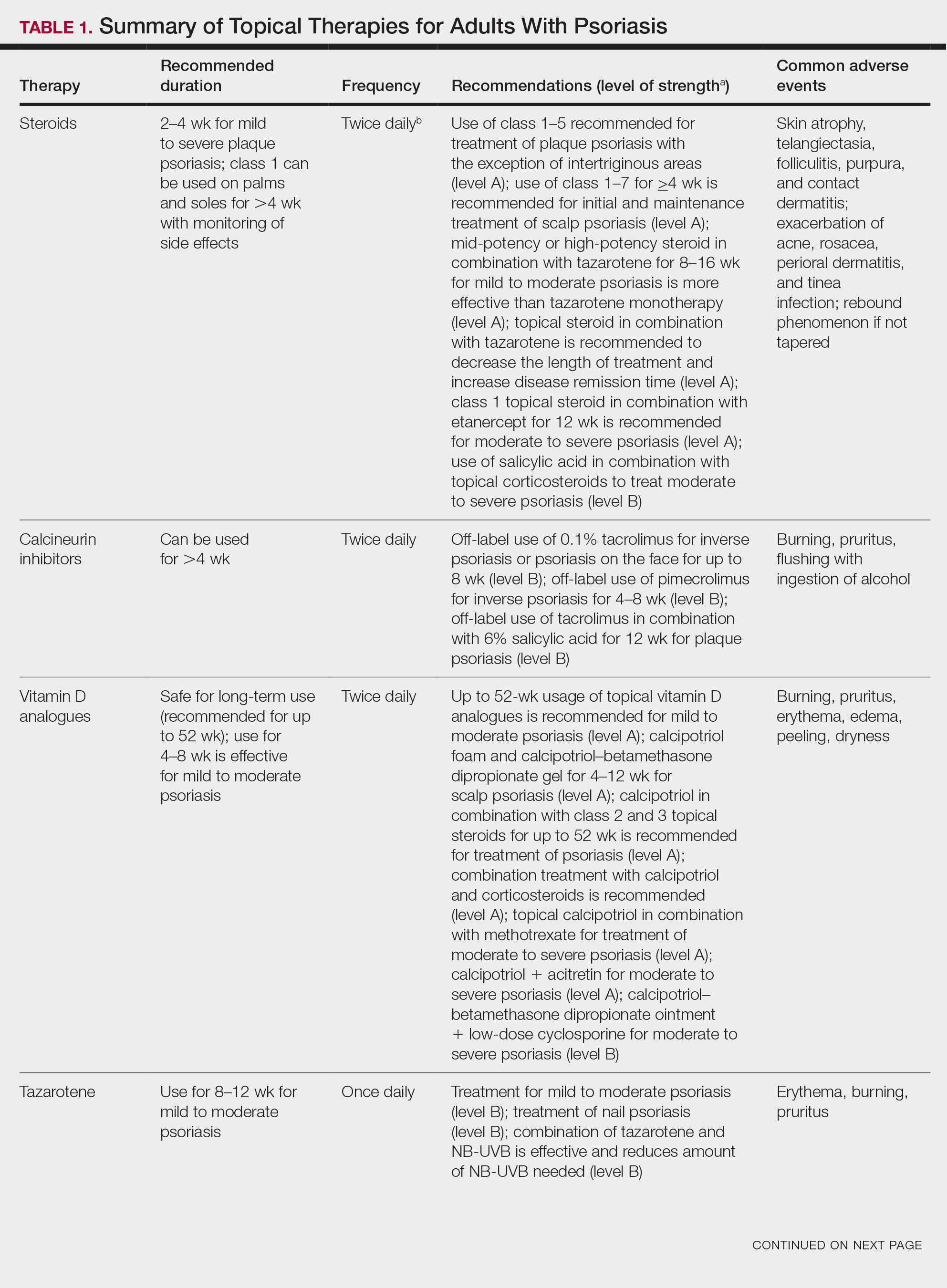

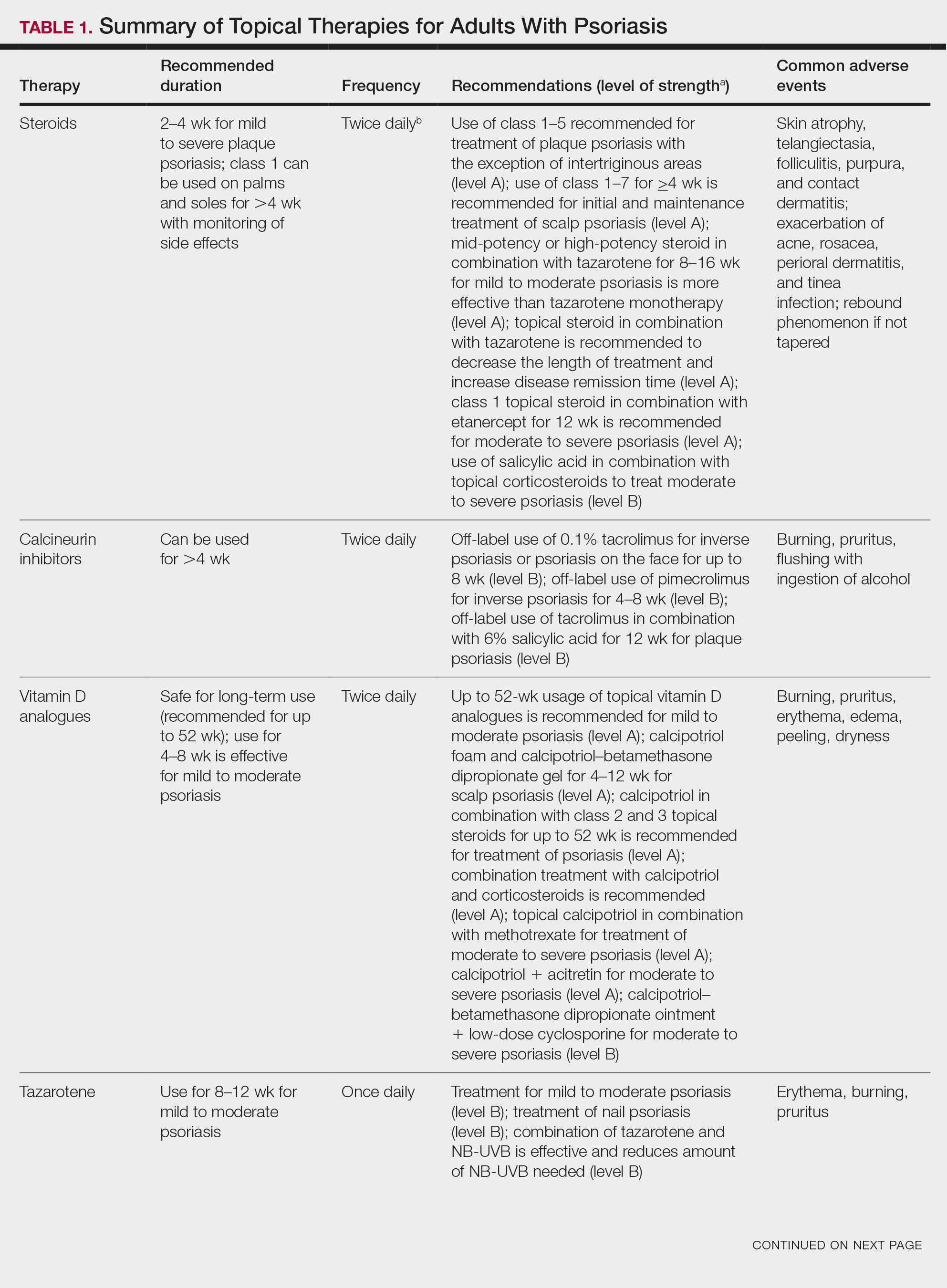

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines in 2020 for managing psoriasis with topical agents in adults.2 This review presents the most up-to-date clinical recommendations for topical agent use in adult patients with psoriasis and elaborates on each drug’s pharmacologic and safety profile. Specifically, evidence-based treatment recommendations for topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), vitamin D analogues, retinoids (tazarotene), emollients, keratolytics (salicylic acid), anthracenes (anthralin), and keratoplastics (coal tar) will be addressed (Table 1). Recommendations for combination therapy with other treatment modalities including UVB light therapy, biologics, and systemic nonbiologic agents also will be discussed.

Selecting a Topical Agent Based on Disease Localization

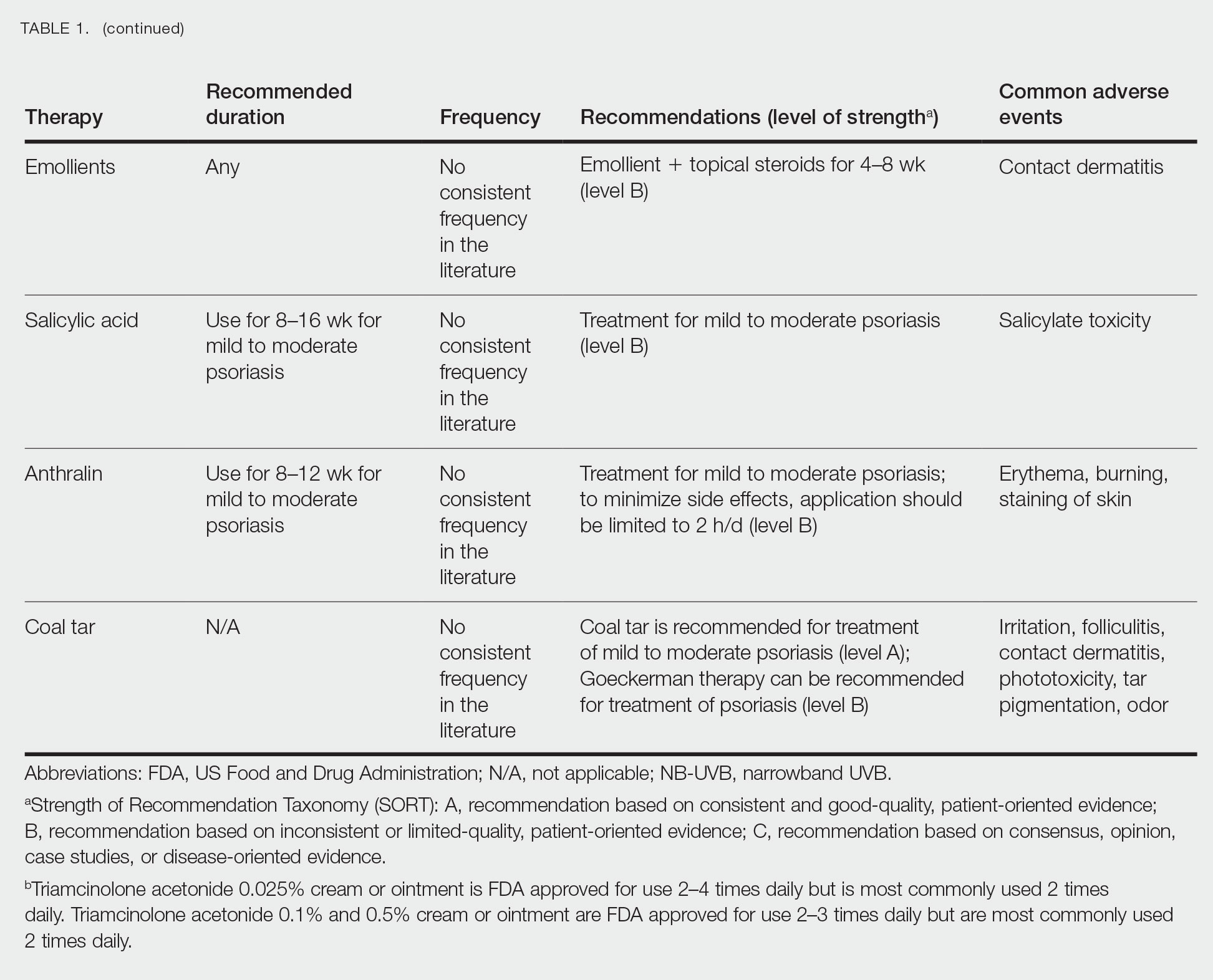

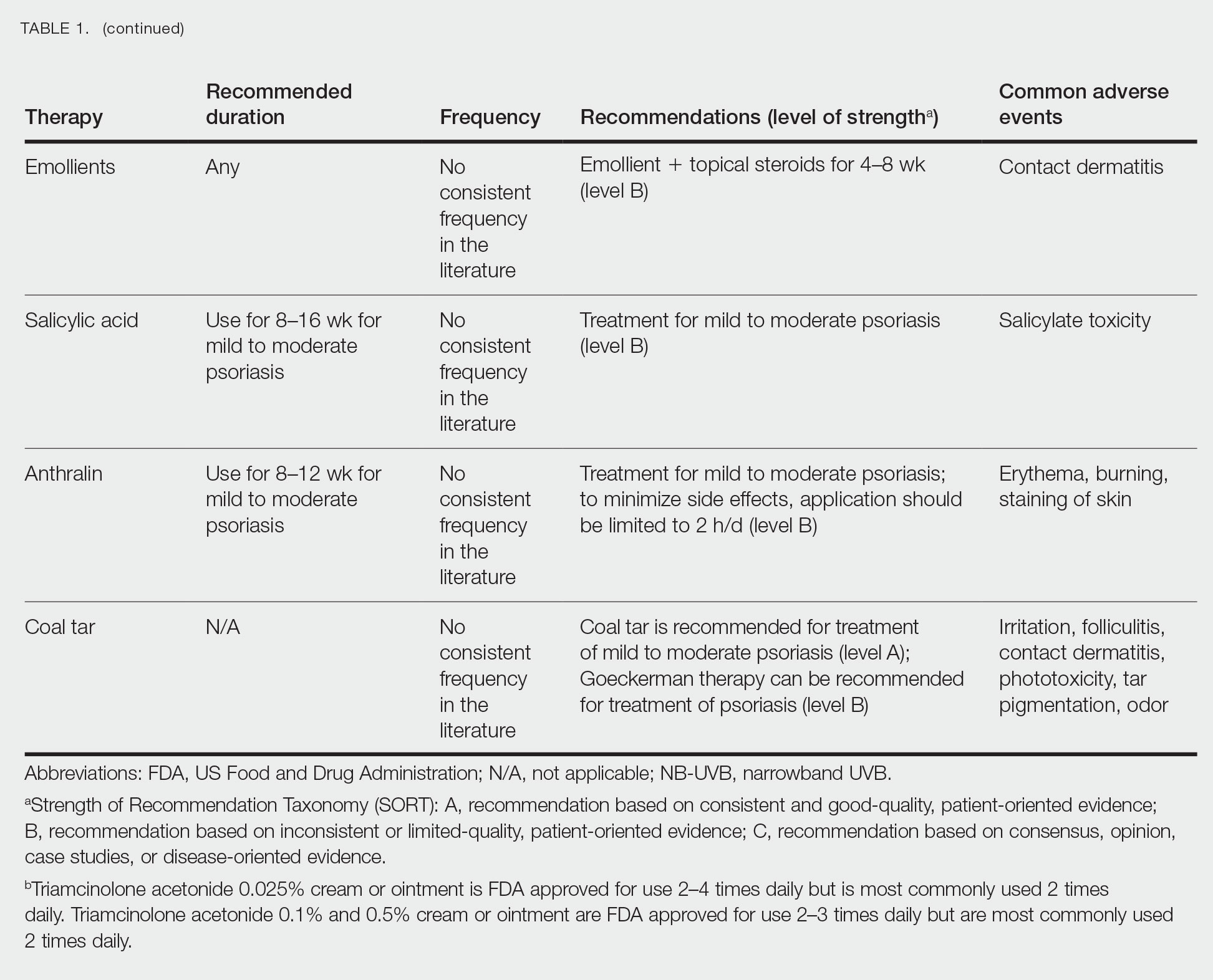

When treating patients with psoriasis with topical therapies, clinicians should take into consideration drug potency, as it determines how effective a treatment will be in penetrating the skin barrier. Plaque characteristics, such as distribution (localized vs widespread), anatomical localization (flexural, scalp, palms/soles/nails), size (large vs small), and thickness (thick vs thin), not only influence treatment effectiveness but also the incidence of drug-related adverse events. Furthermore, preferred topical therapies are tailored to each patient based on disease characteristics and activity. Coal tar and anthralin have been used less frequently than other topical therapies for psoriasis because of their undesirable side-effect profiles (Table 1).3

Face and Intertriginous Regions—The face and intertriginous areas are sensitive because skin tends to be thin in these regions. Emollients are recommended for disease in these locations given their safety and flexibility in use for most areas. Conversely, anthralin should be avoided on the face, intertriginous areas, and even highly visible locations because of the potential for skin staining. Low-potency corticosteroids also have utility in psoriasis distributed on the face and intertriginous regions. Additionally, application of steroids around the eyes should be cautioned because topical steroids can induce ocular complications such as glaucoma and cataracts in rare circumstances.4

Off-label use of CNIs for psoriasis on the face and intertriginous areas also is effective. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for off-label use of 0.1% tacrolimus for up to 8 weeks for inverse psoriasis or psoriasis on the face. Off-label use of pimecrolimus for 4 to 8 weeks also can be considered for inverse psoriasis. Combination therapy consisting of hydrocortisone with calcipotriol ointment is another effective regimen.5 One study also suggested that use of crisaborole for 4 to 8 weeks in intertriginous psoriasis can be effective and well tolerated.6

Scalp—The vehicle of medication administration is especially important in hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, as these areas are challenging for medication application and patient adherence. Thus, patient preferences for the vehicle must be considered. Several studies have been conducted to assess preference for various vehicles in scalp psoriasis. A foam or solution may be preferable to ointments, gels, or creams.7 Gels may be preferred over ointments.8 There is a level A recommendation supporting the use of class 1 to 7 topical steroids for a minimum of 4 weeks as initial and maintenance treatment of scalp psoriasis. The highest level of evidence (level A) also supports the use of calcipotriol foam or combination therapy of calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate gel for 4 to 12 weeks as treatment of mild to moderate scalp psoriasis.

Nails—Several options for topical medications have been recommended for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for the use of tazarotene for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Another effective regimen is combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and betamethasone dipropionate.9 Topical steroid use for nail psoriasis should be limited to 12 weeks because of the risk for bone atrophy with chronic steroid use.

Palmoplantar—The palms and soles have a thicker epidermal layer than other areas of the body. As a result, class 1 corticosteroids can be used for palmoplantar psoriasis for more than 4 weeks with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects such as skin atrophy, tachyphylaxis, or tinea infection. Tazarotene also has been shown to be helpful in treating palmoplantar psoriasis.

Resistant Disease—Intralesional steroids are beneficial treatment options for recalcitrant psoriasis in glabrous areas, as well as for palmoplantar, nail, and scalp psoriasis. Up to 10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide used every 3 to 4 weeks is an effective regimen.10Pregnancy/Breastfeeding—Women of childbearing potential have additional safety precautions that should be considered during medication selection. Emollients have been shown to be safe during pregnancy and lactation. Currently, there is little known about CNI use during pregnancy. During lactation, CNIs can be used by breastfeeding mothers in most areas, excluding the breasts. Evaluation of the safety of anthralin and vitamin D analogues during pregnancy and lactation have not been studied. For these agents, dermatologists need to use their clinical judgment to weigh the risks and benefits of medication, particularly in patients requiring occlusion, higher medication doses, or treatment over a large surface area. Salicylic acid should be used with caution in pregnant and breastfeeding mothers because it is a pregnancy category C drug. Lower-potency corticosteroids may be used with caution during pregnancy and breastfeeding. More potent corticosteroids and coal tar, however, should be avoided. Similarly, tazarotene use is contraindicated in pregnancy. According to the US Food and Drug Administration labels for all forms of topical tazarotene, a pregnancy test must be obtained 2 weeks prior to tazarotene treatment initiation in women of childbearing potential because of the risk for serious fetal malformations and toxicity.

Recommendations, Risks, and Benefits of Topical Therapy for the Management of Psoriasis

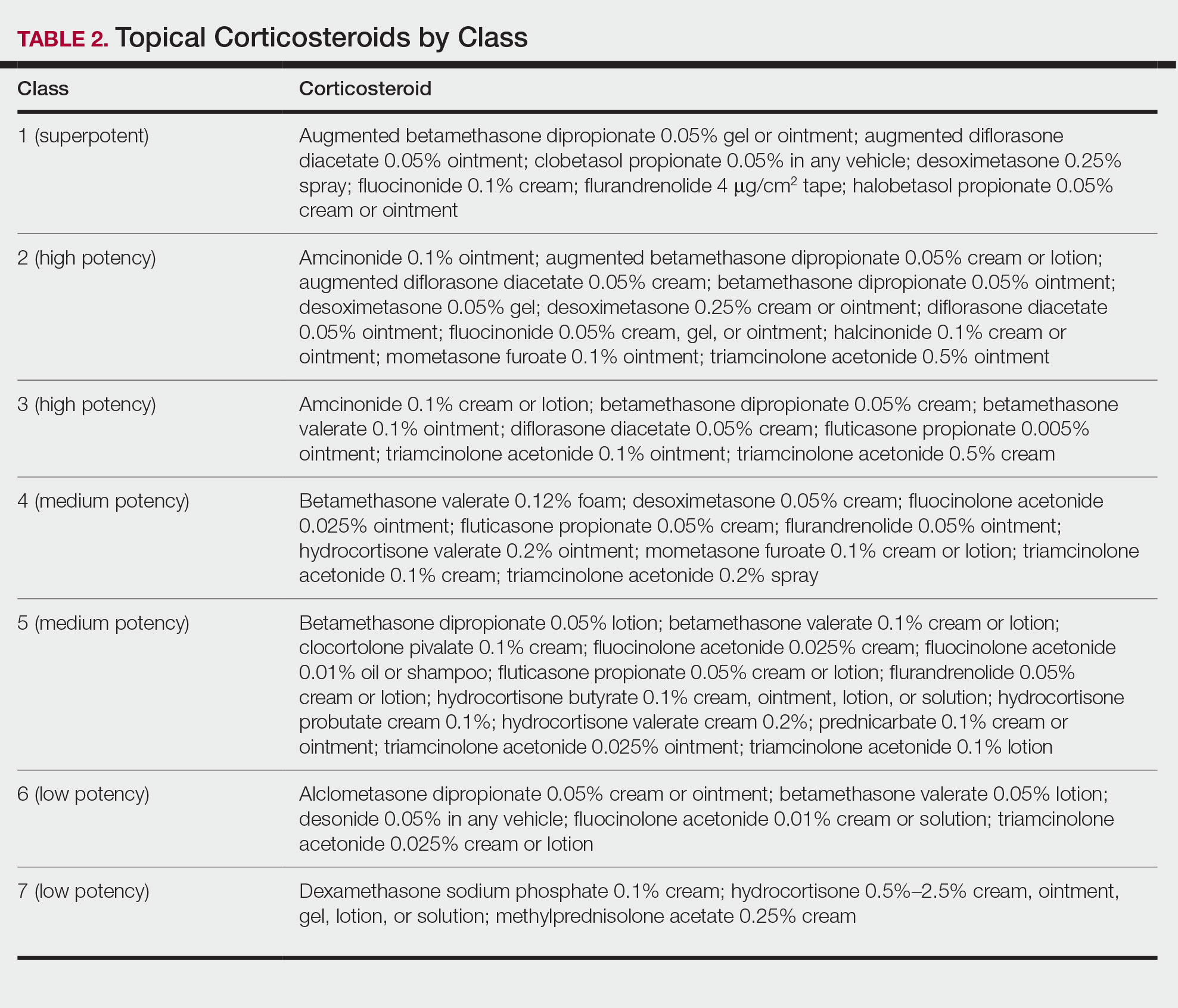

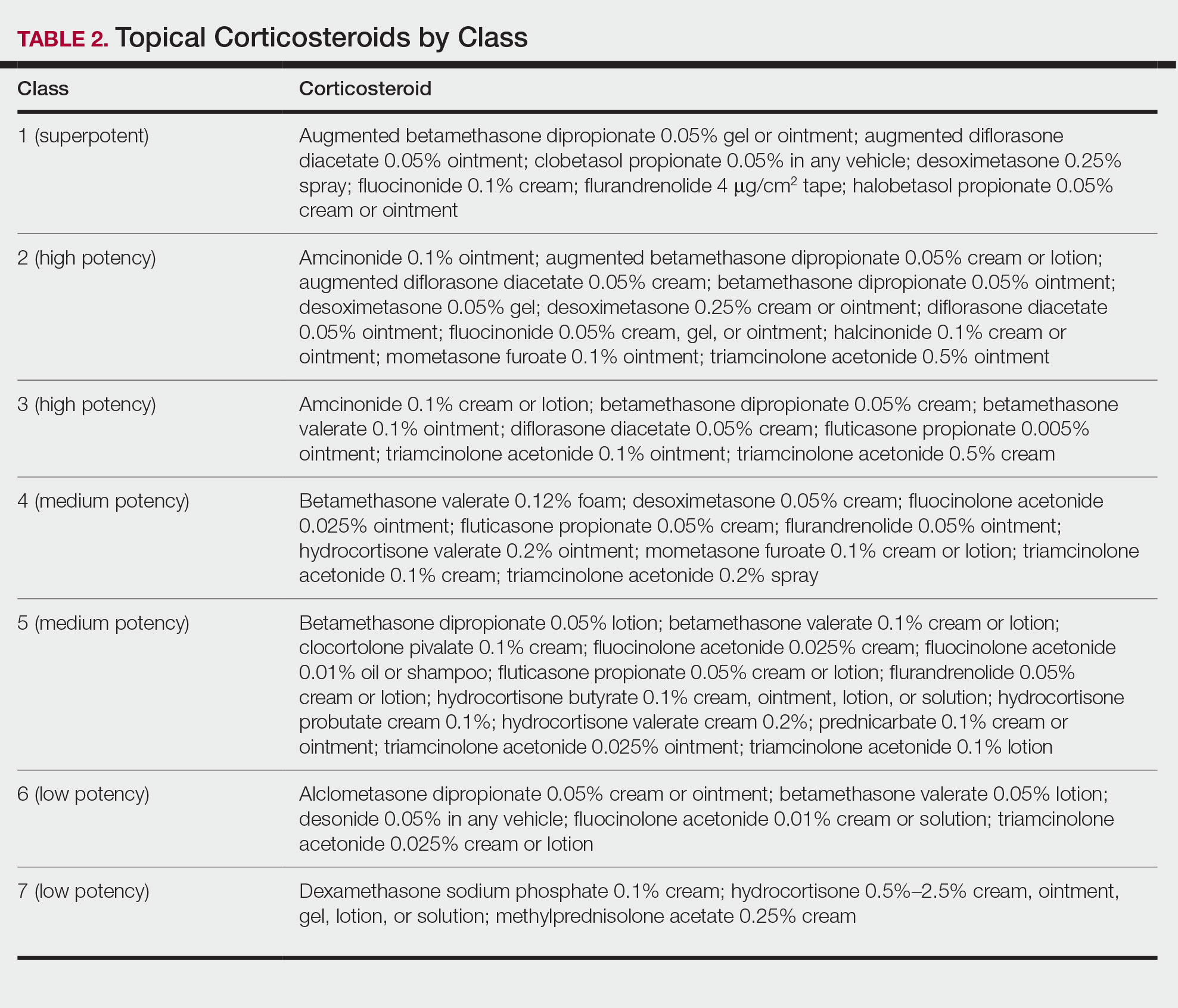

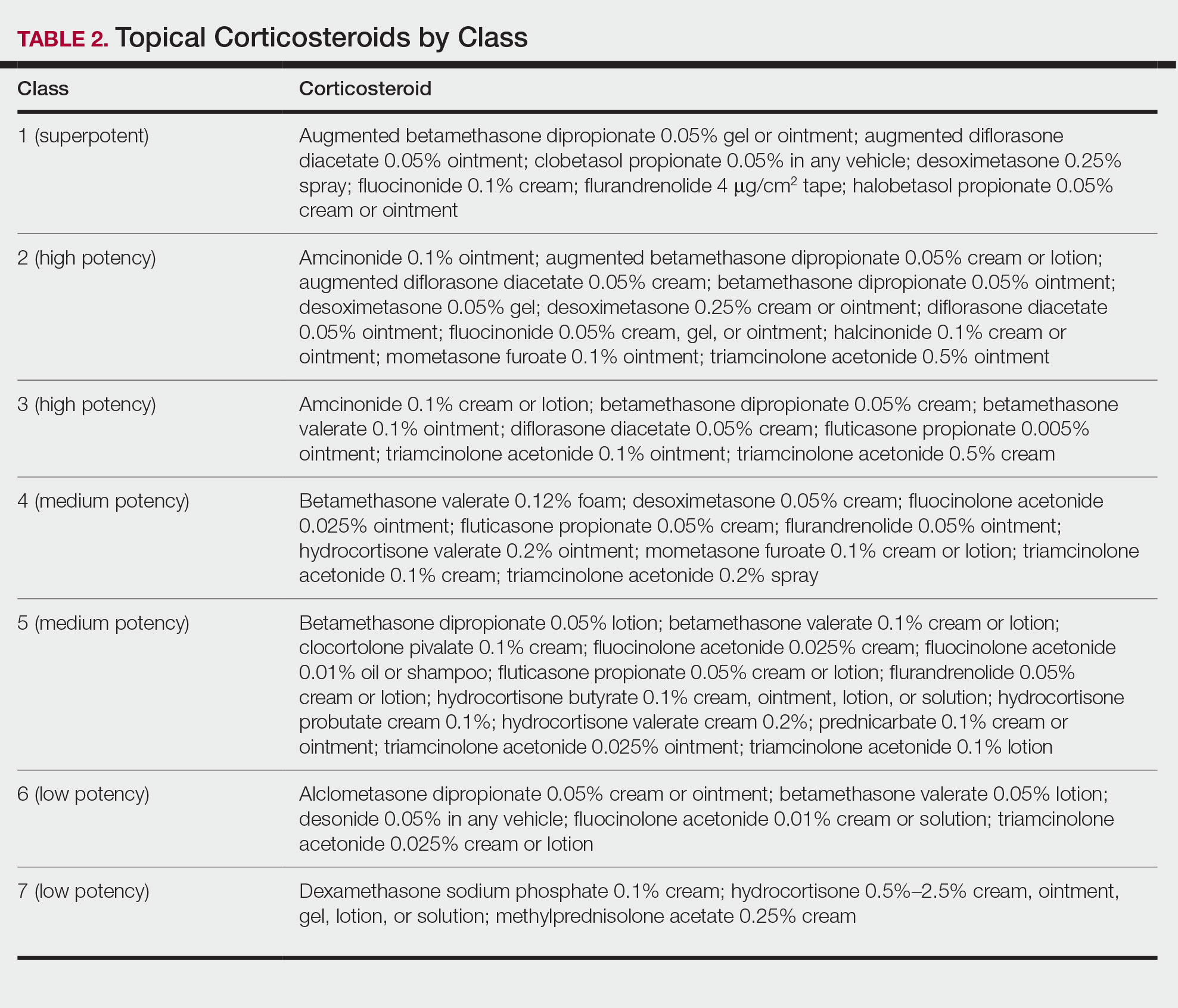

Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids (TCs) are widely used for inflammatory skin conditions and are available in a variety of strengths (Table 2). They are thought to exert their action by regulating the gene transcription of proinflammatory mediators. For psoriasis, steroids are recommended for 2 to 4 weeks, depending on disease severity. Although potent and superpotent steroids are more effective than mild- to moderate-strength TCs, use of lower-potency TCs may be warranted depending on disease distribution and localization.11 For treatment of psoriasis with no involvement of the intertriginous areas, use of class 1 to 5 TCs for up to 4 weeks is recommended.

For moderate to severe psoriasis with 20% or less body surface area (BSA) affected, combination therapy consisting of mometasone and salicylic acid has been shown to be more effective than mometasone alone.12,13 There currently is a level A recommendation for the use of combination therapy with class 1 TCs and etanercept for 12 weeks in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who require both systemic and topical therapies for disease control. Similarly, combination therapy with infliximab and high-potency TCs has a level B recommendation to enhance efficacy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis.14 High-quality studies on the use of TCs with anti–IL-12/IL-23, anti–IL-23, and anti–IL-17 currently are unavailable, but the combination is not expected to be unsafe.14,15 Combination therapy of betamethasone dipropionate ointment and low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative regimen with a level B recommendation.

The most common adverse effects with use of TCs are skin thinning and atrophy, telangiectasia, and striae (Table 1). With clinical improvement of disease, it is recommended that clinicians taper TCs to prevent rebound effect. To decrease TC-related adverse effects, clinicians should use combination therapy with steroid-sparing agents for disease maintenance, transition to lower-potency corticosteroids, or use intermittent steroid therapy. Systemic effects of TC use include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, Cushing syndrome, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head.16-18 These systemic effects with TC use are rare unless treatment is for disease involving greater than 20% BSA or occlusion for more than 4 weeks.

Calcineurin Inhibitors—Calcineurin inhibitors inhibit calcineurin phosphorylation and T-cell activation, subsequently decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Currently, they are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat psoriasis but have demonstrated efficacy in randomized control trials (RCTs) for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. In RCTs, 71% of patients using pimecrolimus cream 0.1% twice daily for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) compared with 21% of placebo-treated patients (N=57).19 Other trials have shown that 65% of patients receiving tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with 31% of placebo-treated patients (N=167).20 Because of their efficacy in RCTs, CNIs commonly are used off label to treat psoriasis.

The most common adverse effects with CNI use are burning, pruritus, and flushing with alcohol ingestion (Table 1). Additionally, CNIs have a black box warning that use may increase the risk for malignancy, but this risk has not been demonstrated with topical use in humans.21Vitamin D Analogues—The class of vitamin D analogues—calcipotriol/calcipotriene and calcitriol—frequently are used to treat psoriasis. Vitamin D analogues exert their beneficial effects by inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation and enhancing keratinocyte differentiation. They also are ideal for long-term use (up to 52 weeks) in mild to moderate psoriasis and can be used in combination with class 2 and 3 TCs. There is a level A recommendation that supports the use of combination therapy with calcipotriol and TCs for the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

For severe psoriasis, many studies have investigated the efficacy of combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and systemic treatments. Combination therapy with calcipotriol and methotrexate or calcipotriol and acitretin are effective treatment regimens with level A recommendations. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate ointment in combination with low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative option with a level B recommendation. Because vitamin D analogues are inactivated by UVA and UVB radiation, clinicians should advise their patients to use vitamin D analogues after receiving UVB phototherapy.22

Common adverse effects of vitamin D analogues include burning, pruritus, erythema, and dryness (Table 1). Hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone suppression are extremely rare unless treatment occurs over a large surface area (>30% BSA) or the patient has concurrent renal disease or impairments in calcium metabolism.

Tazarotene—Tazarotene is a topical retinoid that acts by decreasing keratinocyte proliferation, facilitating keratinocyte differentiation, and inhibiting inflammation. Patients with mild to moderate psoriasis are recommended to receive tazarotene treatment for 8 to 12 weeks. In several RCTs, tazarotene gel 0.1% and tazarotene cream 0.1% and 0.05% achieved treatment success in treating plaque psoriasis.23,24

For increased efficacy, clinicians can recommend combination therapy with tazarotene and a TC. Combination therapy with tazarotene and a mid- or high-potency TC for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be more effective than treatment with tazarotene alone.25 Thus, there is a level A recommendation for use of this combination to treat mild to moderate psoriasis. Agents used in combination therapy work synergistically to decrease the length of treatment and increase the duration of remission. The frequency of adverse effects, such as irritation from tazarotene and skin atrophy from TCs, also are reduced.26 Combination therapy with tazarotene and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is another effective option that requires less UV radiation than NB-UVB alone because of the synergistic effects of both treatment modalities.27 Clinicians should counsel patients on the adverse effects of tazarotene, which include local irritation, burning, pruritus, and erythema (Table 1).

Emollients—Emollients are nonmedicated moisturizers that decrease the amount of transepidermal water loss. There is a level B recommendation for use of emollients and TCs in combination for 4 to 8 weeks to treat psoriasis. In fact, combination therapy with mometasone and emollients has demonstrated greater improvement in symptoms of palmoplantar psoriasis (ie, erythema, desquamation, infiltration, BSA involvement) than mometasone alone.28 Emollients are safe options that can be used on all areas of the body and during pregnancy and lactation. Although adverse effects of emollients are rare, clinicians should counsel patients on the risk for contact dermatitis if specific allergies to ingredients/fragrances exist (Table 1).

Salicylic Acid—Salicylic acid is a topical keratolytic that can be used to treat psoriatic plaques. Use of salicylic acid for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be effective for mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy of salicylic acid and TCs in patients with 20% or less BSA affected is a safe and effective option with a level B recommendation. Combination therapy with salicylic acid and calcipotriene, however, should be avoided because calcipotriene is inactivated by salicylic acid. It also is recommended that salicylic acid application follow phototherapy when both treatment modalities are used in combination.29,30 Clinicians should be cautious about using salicylic acid in patients with renal or hepatic disease because of the increased risk for salicylate toxicity (Table 1).

Anthralin—Anthralin is a synthetic hydrocarbon derivative that has been shown to reduce inflammation and normalize keratinocyte proliferation through an unknown mechanism. It is recommended that patients with mild to moderate psoriasis receive anthralin treatment for 8 to 12 weeks, with a maximum application time of 2 hours per day. Combination therapy of excimer laser and anthralin has been shown to be more effective in treating psoriasis than anthralin alone.31 Therefore, clinicians have the option of including excimer laser therapy for additional disease control. Anthralin should be avoided on the face, flexural regions, and highly visible areas because of potential skin staining (Table 1). Other adverse effects include application-site burning and erythema.

Coal Tar—Coal tar is a heterogenous mixture of aromatic hydrocarbons that is an effective treatment of psoriasis because of its inherent anti-inflammatory and keratoplastic properties. There is high-quality evidence supporting a level A recommendation for coal tar use in mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy with NB-UVB and coal tar (also known as Goeckerman therapy) is a recommended treatment option with a quicker onset of action and improved outcomes compared with NB-UVB therapy alone.32,33 Adverse events of coal tar include application-site irritation, folliculitis, contact dermatitis, phototoxicity, and skin pigmentation (Table 1).

Conclusion

Topical medications are versatile treatment options that can be utilized as monotherapy or adjunct therapy for mild to severe psoriasis. Benefits of topical agents include minimal required monitoring, few contraindications, and direct localized effect on plaques. Therefore, side effects with topical agent use rarely are systemic. Medication interactions are less of a concern with topical therapies; thus, they have better safety profiles compared with systemic therapies. This clinical review summarizes the recently published evidence-based guidelines from the AAD and NPF on the use of topical agents in psoriasis and may be a useful guiding framework for clinicians in their everyday practice.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study. J Med Econ. 2018:1-9.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Svendsen MT, Jeyabalan J, Andersen KE, et al. Worldwide utilization of topical remedies in treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:374-383.

- Day A, Abramson AK, Patel M, et al. The spectrum of oculocutaneous disease: part II. neoplastic and drug-related causes of oculocutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:821.e821-819.

- Choi JW, Choi JW, Kwon IH, et al. High-concentration (20 μg g-¹) tacalcitol ointment in the treatment of facial psoriasis: an 8-week open-label clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1359-1364.

- Hashim PW, Chima M, Kim HJ, et al. Crisaborole 2% ointment for the treatment of intertriginous, anogenital, and facial psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:360-365.

- Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70:327-332.

- Iversen L, Jakobsen HB. Patient preferences for topical psoriasis treatments are diverse and difficult to predict. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:273-285.

- Clobex Package insert. Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2012.

- Kenalog-10 Injection. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2018.

- Mason J, Mason AR, Cork MJ. Topical preparations for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:351-364.

- Koo J, Cuffie CA, Tanner DJ, et al. Mometasone furoate 0.1%-salicylic acid 5% ointment versus mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a multicenter study. Clin Ther. 1998;20:283-291.

- Tiplica GS, Salavastru CM. Mometasone furoate 0.1% and salicylic acid 5% vs. mometasone furoate 0.1% as sequential local therapy in psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:905-912.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Strober BE, Bissonnette R, Fiorentino D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologic agents for the treatment of psoriasis in a real-world setting: results from a large, prospective, observational study (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry [PSOLAR]). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:851-861.e854.

- Castela E, Archier E, Devaux S, et al. Topical corticosteroids in plaque psoriasis: a systematic review of risk of adrenal axis suppression and skin atrophy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):47-51.

- Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Honma M, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after long-term topical corticosteroid treatment in a psoriasis patient. J Dermatol. 2012;39:887-888.

- el Maghraoui A, Tabache F, Bezza A, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after topical corticosteroid therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:233.

- Gribetz C, Ling M, Lebwohl M, et al. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of intertriginous psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:731-738.

- Lebwohl M, Freeman AK, Chapman MS, et al. Tacrolimus ointment is effective for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:723-730.

- Paller AS, Fölster-Holst R, Chen SC, et al. No evidence of increased cancer incidence in children using topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:375-381.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Lebwohl M, Ast E, Callen JP, et al. Once-daily tazarotene gel versus twice-daily fluocinonide cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:705-711.

- Weinstein GD, Koo JY, Krueger GG, et al. Tazarotene cream in the treatment of psoriasis: two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene creams 0.05% and 0.1% applied once daily for 12 weeks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:760-767.

- Lebwohl M, Lombardi K, Tan MH. Duration of improvement in psoriasis after treatment with tazarotene 0.1% gel plus clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment: comparison of maintenance treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:64-66.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Koo JY, Lowe NJ, Lew-Kaya DA, et al. Tazarotene plus UVB phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:821-828.

- Cassano N, Mantegazza R, Battaglini S, et al. Adjuvant role of a new emollient cream in patients with palmar and/or plantar psoriasis: a pilot randomized open-label study. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:789-792.

- Kristensen B, Kristensen O. Topical salicylic acid interferes with UVB therapy for psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:37-40.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Rogalski C, Grunewald S, Schetschorke M, et al. Treatment of plaque-type psoriasis with the 308 nm excimer laser in combination with dithranol or calcipotriol. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:184-190.

- Bagel J. LCD plus NB-UVB reduces time to improvement of psoriasis vs. NB-UVB alone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:351-357.

- Abdallah MA, El-Khateeb EA, Abdel-Rahman SH. The influence of psoriatic plaques pretreatment with crude coal tar vs. petrolatum on the efficacy of narrow-band ultraviolet B: a half-vs.-half intra-individual double-blinded comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:226-230.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythematous scaly plaques that can invoke substantial pain, pruritus, and quality-of-life disturbance in patients. Topical therapies are the most commonly used medications for treating psoriasis, with one study (N = 128,308) showing that more than 85% of patients with psoriasis were managed solely with topical medications. 1 For patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical agents alone may be able to control disease completely. For those with more severe disease, topical agents are used adjunctively with systemic or biologic agents to optimize disease control in localized areas.

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines in 2020 for managing psoriasis with topical agents in adults.2 This review presents the most up-to-date clinical recommendations for topical agent use in adult patients with psoriasis and elaborates on each drug’s pharmacologic and safety profile. Specifically, evidence-based treatment recommendations for topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), vitamin D analogues, retinoids (tazarotene), emollients, keratolytics (salicylic acid), anthracenes (anthralin), and keratoplastics (coal tar) will be addressed (Table 1). Recommendations for combination therapy with other treatment modalities including UVB light therapy, biologics, and systemic nonbiologic agents also will be discussed.

Selecting a Topical Agent Based on Disease Localization

When treating patients with psoriasis with topical therapies, clinicians should take into consideration drug potency, as it determines how effective a treatment will be in penetrating the skin barrier. Plaque characteristics, such as distribution (localized vs widespread), anatomical localization (flexural, scalp, palms/soles/nails), size (large vs small), and thickness (thick vs thin), not only influence treatment effectiveness but also the incidence of drug-related adverse events. Furthermore, preferred topical therapies are tailored to each patient based on disease characteristics and activity. Coal tar and anthralin have been used less frequently than other topical therapies for psoriasis because of their undesirable side-effect profiles (Table 1).3

Face and Intertriginous Regions—The face and intertriginous areas are sensitive because skin tends to be thin in these regions. Emollients are recommended for disease in these locations given their safety and flexibility in use for most areas. Conversely, anthralin should be avoided on the face, intertriginous areas, and even highly visible locations because of the potential for skin staining. Low-potency corticosteroids also have utility in psoriasis distributed on the face and intertriginous regions. Additionally, application of steroids around the eyes should be cautioned because topical steroids can induce ocular complications such as glaucoma and cataracts in rare circumstances.4

Off-label use of CNIs for psoriasis on the face and intertriginous areas also is effective. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for off-label use of 0.1% tacrolimus for up to 8 weeks for inverse psoriasis or psoriasis on the face. Off-label use of pimecrolimus for 4 to 8 weeks also can be considered for inverse psoriasis. Combination therapy consisting of hydrocortisone with calcipotriol ointment is another effective regimen.5 One study also suggested that use of crisaborole for 4 to 8 weeks in intertriginous psoriasis can be effective and well tolerated.6

Scalp—The vehicle of medication administration is especially important in hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, as these areas are challenging for medication application and patient adherence. Thus, patient preferences for the vehicle must be considered. Several studies have been conducted to assess preference for various vehicles in scalp psoriasis. A foam or solution may be preferable to ointments, gels, or creams.7 Gels may be preferred over ointments.8 There is a level A recommendation supporting the use of class 1 to 7 topical steroids for a minimum of 4 weeks as initial and maintenance treatment of scalp psoriasis. The highest level of evidence (level A) also supports the use of calcipotriol foam or combination therapy of calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate gel for 4 to 12 weeks as treatment of mild to moderate scalp psoriasis.

Nails—Several options for topical medications have been recommended for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for the use of tazarotene for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Another effective regimen is combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and betamethasone dipropionate.9 Topical steroid use for nail psoriasis should be limited to 12 weeks because of the risk for bone atrophy with chronic steroid use.

Palmoplantar—The palms and soles have a thicker epidermal layer than other areas of the body. As a result, class 1 corticosteroids can be used for palmoplantar psoriasis for more than 4 weeks with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects such as skin atrophy, tachyphylaxis, or tinea infection. Tazarotene also has been shown to be helpful in treating palmoplantar psoriasis.

Resistant Disease—Intralesional steroids are beneficial treatment options for recalcitrant psoriasis in glabrous areas, as well as for palmoplantar, nail, and scalp psoriasis. Up to 10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide used every 3 to 4 weeks is an effective regimen.10Pregnancy/Breastfeeding—Women of childbearing potential have additional safety precautions that should be considered during medication selection. Emollients have been shown to be safe during pregnancy and lactation. Currently, there is little known about CNI use during pregnancy. During lactation, CNIs can be used by breastfeeding mothers in most areas, excluding the breasts. Evaluation of the safety of anthralin and vitamin D analogues during pregnancy and lactation have not been studied. For these agents, dermatologists need to use their clinical judgment to weigh the risks and benefits of medication, particularly in patients requiring occlusion, higher medication doses, or treatment over a large surface area. Salicylic acid should be used with caution in pregnant and breastfeeding mothers because it is a pregnancy category C drug. Lower-potency corticosteroids may be used with caution during pregnancy and breastfeeding. More potent corticosteroids and coal tar, however, should be avoided. Similarly, tazarotene use is contraindicated in pregnancy. According to the US Food and Drug Administration labels for all forms of topical tazarotene, a pregnancy test must be obtained 2 weeks prior to tazarotene treatment initiation in women of childbearing potential because of the risk for serious fetal malformations and toxicity.

Recommendations, Risks, and Benefits of Topical Therapy for the Management of Psoriasis

Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids (TCs) are widely used for inflammatory skin conditions and are available in a variety of strengths (Table 2). They are thought to exert their action by regulating the gene transcription of proinflammatory mediators. For psoriasis, steroids are recommended for 2 to 4 weeks, depending on disease severity. Although potent and superpotent steroids are more effective than mild- to moderate-strength TCs, use of lower-potency TCs may be warranted depending on disease distribution and localization.11 For treatment of psoriasis with no involvement of the intertriginous areas, use of class 1 to 5 TCs for up to 4 weeks is recommended.

For moderate to severe psoriasis with 20% or less body surface area (BSA) affected, combination therapy consisting of mometasone and salicylic acid has been shown to be more effective than mometasone alone.12,13 There currently is a level A recommendation for the use of combination therapy with class 1 TCs and etanercept for 12 weeks in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who require both systemic and topical therapies for disease control. Similarly, combination therapy with infliximab and high-potency TCs has a level B recommendation to enhance efficacy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis.14 High-quality studies on the use of TCs with anti–IL-12/IL-23, anti–IL-23, and anti–IL-17 currently are unavailable, but the combination is not expected to be unsafe.14,15 Combination therapy of betamethasone dipropionate ointment and low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative regimen with a level B recommendation.

The most common adverse effects with use of TCs are skin thinning and atrophy, telangiectasia, and striae (Table 1). With clinical improvement of disease, it is recommended that clinicians taper TCs to prevent rebound effect. To decrease TC-related adverse effects, clinicians should use combination therapy with steroid-sparing agents for disease maintenance, transition to lower-potency corticosteroids, or use intermittent steroid therapy. Systemic effects of TC use include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, Cushing syndrome, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head.16-18 These systemic effects with TC use are rare unless treatment is for disease involving greater than 20% BSA or occlusion for more than 4 weeks.

Calcineurin Inhibitors—Calcineurin inhibitors inhibit calcineurin phosphorylation and T-cell activation, subsequently decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Currently, they are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat psoriasis but have demonstrated efficacy in randomized control trials (RCTs) for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. In RCTs, 71% of patients using pimecrolimus cream 0.1% twice daily for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) compared with 21% of placebo-treated patients (N=57).19 Other trials have shown that 65% of patients receiving tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with 31% of placebo-treated patients (N=167).20 Because of their efficacy in RCTs, CNIs commonly are used off label to treat psoriasis.

The most common adverse effects with CNI use are burning, pruritus, and flushing with alcohol ingestion (Table 1). Additionally, CNIs have a black box warning that use may increase the risk for malignancy, but this risk has not been demonstrated with topical use in humans.21Vitamin D Analogues—The class of vitamin D analogues—calcipotriol/calcipotriene and calcitriol—frequently are used to treat psoriasis. Vitamin D analogues exert their beneficial effects by inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation and enhancing keratinocyte differentiation. They also are ideal for long-term use (up to 52 weeks) in mild to moderate psoriasis and can be used in combination with class 2 and 3 TCs. There is a level A recommendation that supports the use of combination therapy with calcipotriol and TCs for the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

For severe psoriasis, many studies have investigated the efficacy of combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and systemic treatments. Combination therapy with calcipotriol and methotrexate or calcipotriol and acitretin are effective treatment regimens with level A recommendations. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate ointment in combination with low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative option with a level B recommendation. Because vitamin D analogues are inactivated by UVA and UVB radiation, clinicians should advise their patients to use vitamin D analogues after receiving UVB phototherapy.22

Common adverse effects of vitamin D analogues include burning, pruritus, erythema, and dryness (Table 1). Hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone suppression are extremely rare unless treatment occurs over a large surface area (>30% BSA) or the patient has concurrent renal disease or impairments in calcium metabolism.

Tazarotene—Tazarotene is a topical retinoid that acts by decreasing keratinocyte proliferation, facilitating keratinocyte differentiation, and inhibiting inflammation. Patients with mild to moderate psoriasis are recommended to receive tazarotene treatment for 8 to 12 weeks. In several RCTs, tazarotene gel 0.1% and tazarotene cream 0.1% and 0.05% achieved treatment success in treating plaque psoriasis.23,24

For increased efficacy, clinicians can recommend combination therapy with tazarotene and a TC. Combination therapy with tazarotene and a mid- or high-potency TC for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be more effective than treatment with tazarotene alone.25 Thus, there is a level A recommendation for use of this combination to treat mild to moderate psoriasis. Agents used in combination therapy work synergistically to decrease the length of treatment and increase the duration of remission. The frequency of adverse effects, such as irritation from tazarotene and skin atrophy from TCs, also are reduced.26 Combination therapy with tazarotene and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is another effective option that requires less UV radiation than NB-UVB alone because of the synergistic effects of both treatment modalities.27 Clinicians should counsel patients on the adverse effects of tazarotene, which include local irritation, burning, pruritus, and erythema (Table 1).

Emollients—Emollients are nonmedicated moisturizers that decrease the amount of transepidermal water loss. There is a level B recommendation for use of emollients and TCs in combination for 4 to 8 weeks to treat psoriasis. In fact, combination therapy with mometasone and emollients has demonstrated greater improvement in symptoms of palmoplantar psoriasis (ie, erythema, desquamation, infiltration, BSA involvement) than mometasone alone.28 Emollients are safe options that can be used on all areas of the body and during pregnancy and lactation. Although adverse effects of emollients are rare, clinicians should counsel patients on the risk for contact dermatitis if specific allergies to ingredients/fragrances exist (Table 1).

Salicylic Acid—Salicylic acid is a topical keratolytic that can be used to treat psoriatic plaques. Use of salicylic acid for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be effective for mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy of salicylic acid and TCs in patients with 20% or less BSA affected is a safe and effective option with a level B recommendation. Combination therapy with salicylic acid and calcipotriene, however, should be avoided because calcipotriene is inactivated by salicylic acid. It also is recommended that salicylic acid application follow phototherapy when both treatment modalities are used in combination.29,30 Clinicians should be cautious about using salicylic acid in patients with renal or hepatic disease because of the increased risk for salicylate toxicity (Table 1).

Anthralin—Anthralin is a synthetic hydrocarbon derivative that has been shown to reduce inflammation and normalize keratinocyte proliferation through an unknown mechanism. It is recommended that patients with mild to moderate psoriasis receive anthralin treatment for 8 to 12 weeks, with a maximum application time of 2 hours per day. Combination therapy of excimer laser and anthralin has been shown to be more effective in treating psoriasis than anthralin alone.31 Therefore, clinicians have the option of including excimer laser therapy for additional disease control. Anthralin should be avoided on the face, flexural regions, and highly visible areas because of potential skin staining (Table 1). Other adverse effects include application-site burning and erythema.

Coal Tar—Coal tar is a heterogenous mixture of aromatic hydrocarbons that is an effective treatment of psoriasis because of its inherent anti-inflammatory and keratoplastic properties. There is high-quality evidence supporting a level A recommendation for coal tar use in mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy with NB-UVB and coal tar (also known as Goeckerman therapy) is a recommended treatment option with a quicker onset of action and improved outcomes compared with NB-UVB therapy alone.32,33 Adverse events of coal tar include application-site irritation, folliculitis, contact dermatitis, phototoxicity, and skin pigmentation (Table 1).

Conclusion

Topical medications are versatile treatment options that can be utilized as monotherapy or adjunct therapy for mild to severe psoriasis. Benefits of topical agents include minimal required monitoring, few contraindications, and direct localized effect on plaques. Therefore, side effects with topical agent use rarely are systemic. Medication interactions are less of a concern with topical therapies; thus, they have better safety profiles compared with systemic therapies. This clinical review summarizes the recently published evidence-based guidelines from the AAD and NPF on the use of topical agents in psoriasis and may be a useful guiding framework for clinicians in their everyday practice.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythematous scaly plaques that can invoke substantial pain, pruritus, and quality-of-life disturbance in patients. Topical therapies are the most commonly used medications for treating psoriasis, with one study (N = 128,308) showing that more than 85% of patients with psoriasis were managed solely with topical medications. 1 For patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical agents alone may be able to control disease completely. For those with more severe disease, topical agents are used adjunctively with systemic or biologic agents to optimize disease control in localized areas.

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines in 2020 for managing psoriasis with topical agents in adults.2 This review presents the most up-to-date clinical recommendations for topical agent use in adult patients with psoriasis and elaborates on each drug’s pharmacologic and safety profile. Specifically, evidence-based treatment recommendations for topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), vitamin D analogues, retinoids (tazarotene), emollients, keratolytics (salicylic acid), anthracenes (anthralin), and keratoplastics (coal tar) will be addressed (Table 1). Recommendations for combination therapy with other treatment modalities including UVB light therapy, biologics, and systemic nonbiologic agents also will be discussed.

Selecting a Topical Agent Based on Disease Localization

When treating patients with psoriasis with topical therapies, clinicians should take into consideration drug potency, as it determines how effective a treatment will be in penetrating the skin barrier. Plaque characteristics, such as distribution (localized vs widespread), anatomical localization (flexural, scalp, palms/soles/nails), size (large vs small), and thickness (thick vs thin), not only influence treatment effectiveness but also the incidence of drug-related adverse events. Furthermore, preferred topical therapies are tailored to each patient based on disease characteristics and activity. Coal tar and anthralin have been used less frequently than other topical therapies for psoriasis because of their undesirable side-effect profiles (Table 1).3

Face and Intertriginous Regions—The face and intertriginous areas are sensitive because skin tends to be thin in these regions. Emollients are recommended for disease in these locations given their safety and flexibility in use for most areas. Conversely, anthralin should be avoided on the face, intertriginous areas, and even highly visible locations because of the potential for skin staining. Low-potency corticosteroids also have utility in psoriasis distributed on the face and intertriginous regions. Additionally, application of steroids around the eyes should be cautioned because topical steroids can induce ocular complications such as glaucoma and cataracts in rare circumstances.4

Off-label use of CNIs for psoriasis on the face and intertriginous areas also is effective. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for off-label use of 0.1% tacrolimus for up to 8 weeks for inverse psoriasis or psoriasis on the face. Off-label use of pimecrolimus for 4 to 8 weeks also can be considered for inverse psoriasis. Combination therapy consisting of hydrocortisone with calcipotriol ointment is another effective regimen.5 One study also suggested that use of crisaborole for 4 to 8 weeks in intertriginous psoriasis can be effective and well tolerated.6

Scalp—The vehicle of medication administration is especially important in hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, as these areas are challenging for medication application and patient adherence. Thus, patient preferences for the vehicle must be considered. Several studies have been conducted to assess preference for various vehicles in scalp psoriasis. A foam or solution may be preferable to ointments, gels, or creams.7 Gels may be preferred over ointments.8 There is a level A recommendation supporting the use of class 1 to 7 topical steroids for a minimum of 4 weeks as initial and maintenance treatment of scalp psoriasis. The highest level of evidence (level A) also supports the use of calcipotriol foam or combination therapy of calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate gel for 4 to 12 weeks as treatment of mild to moderate scalp psoriasis.

Nails—Several options for topical medications have been recommended for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Currently, there is a level B recommendation for the use of tazarotene for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Another effective regimen is combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and betamethasone dipropionate.9 Topical steroid use for nail psoriasis should be limited to 12 weeks because of the risk for bone atrophy with chronic steroid use.

Palmoplantar—The palms and soles have a thicker epidermal layer than other areas of the body. As a result, class 1 corticosteroids can be used for palmoplantar psoriasis for more than 4 weeks with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects such as skin atrophy, tachyphylaxis, or tinea infection. Tazarotene also has been shown to be helpful in treating palmoplantar psoriasis.

Resistant Disease—Intralesional steroids are beneficial treatment options for recalcitrant psoriasis in glabrous areas, as well as for palmoplantar, nail, and scalp psoriasis. Up to 10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide used every 3 to 4 weeks is an effective regimen.10Pregnancy/Breastfeeding—Women of childbearing potential have additional safety precautions that should be considered during medication selection. Emollients have been shown to be safe during pregnancy and lactation. Currently, there is little known about CNI use during pregnancy. During lactation, CNIs can be used by breastfeeding mothers in most areas, excluding the breasts. Evaluation of the safety of anthralin and vitamin D analogues during pregnancy and lactation have not been studied. For these agents, dermatologists need to use their clinical judgment to weigh the risks and benefits of medication, particularly in patients requiring occlusion, higher medication doses, or treatment over a large surface area. Salicylic acid should be used with caution in pregnant and breastfeeding mothers because it is a pregnancy category C drug. Lower-potency corticosteroids may be used with caution during pregnancy and breastfeeding. More potent corticosteroids and coal tar, however, should be avoided. Similarly, tazarotene use is contraindicated in pregnancy. According to the US Food and Drug Administration labels for all forms of topical tazarotene, a pregnancy test must be obtained 2 weeks prior to tazarotene treatment initiation in women of childbearing potential because of the risk for serious fetal malformations and toxicity.

Recommendations, Risks, and Benefits of Topical Therapy for the Management of Psoriasis

Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids (TCs) are widely used for inflammatory skin conditions and are available in a variety of strengths (Table 2). They are thought to exert their action by regulating the gene transcription of proinflammatory mediators. For psoriasis, steroids are recommended for 2 to 4 weeks, depending on disease severity. Although potent and superpotent steroids are more effective than mild- to moderate-strength TCs, use of lower-potency TCs may be warranted depending on disease distribution and localization.11 For treatment of psoriasis with no involvement of the intertriginous areas, use of class 1 to 5 TCs for up to 4 weeks is recommended.

For moderate to severe psoriasis with 20% or less body surface area (BSA) affected, combination therapy consisting of mometasone and salicylic acid has been shown to be more effective than mometasone alone.12,13 There currently is a level A recommendation for the use of combination therapy with class 1 TCs and etanercept for 12 weeks in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who require both systemic and topical therapies for disease control. Similarly, combination therapy with infliximab and high-potency TCs has a level B recommendation to enhance efficacy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis.14 High-quality studies on the use of TCs with anti–IL-12/IL-23, anti–IL-23, and anti–IL-17 currently are unavailable, but the combination is not expected to be unsafe.14,15 Combination therapy of betamethasone dipropionate ointment and low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative regimen with a level B recommendation.

The most common adverse effects with use of TCs are skin thinning and atrophy, telangiectasia, and striae (Table 1). With clinical improvement of disease, it is recommended that clinicians taper TCs to prevent rebound effect. To decrease TC-related adverse effects, clinicians should use combination therapy with steroid-sparing agents for disease maintenance, transition to lower-potency corticosteroids, or use intermittent steroid therapy. Systemic effects of TC use include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, Cushing syndrome, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head.16-18 These systemic effects with TC use are rare unless treatment is for disease involving greater than 20% BSA or occlusion for more than 4 weeks.

Calcineurin Inhibitors—Calcineurin inhibitors inhibit calcineurin phosphorylation and T-cell activation, subsequently decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Currently, they are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat psoriasis but have demonstrated efficacy in randomized control trials (RCTs) for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. In RCTs, 71% of patients using pimecrolimus cream 0.1% twice daily for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) compared with 21% of placebo-treated patients (N=57).19 Other trials have shown that 65% of patients receiving tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for 8 weeks achieved an investigator global assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with 31% of placebo-treated patients (N=167).20 Because of their efficacy in RCTs, CNIs commonly are used off label to treat psoriasis.

The most common adverse effects with CNI use are burning, pruritus, and flushing with alcohol ingestion (Table 1). Additionally, CNIs have a black box warning that use may increase the risk for malignancy, but this risk has not been demonstrated with topical use in humans.21Vitamin D Analogues—The class of vitamin D analogues—calcipotriol/calcipotriene and calcitriol—frequently are used to treat psoriasis. Vitamin D analogues exert their beneficial effects by inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation and enhancing keratinocyte differentiation. They also are ideal for long-term use (up to 52 weeks) in mild to moderate psoriasis and can be used in combination with class 2 and 3 TCs. There is a level A recommendation that supports the use of combination therapy with calcipotriol and TCs for the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

For severe psoriasis, many studies have investigated the efficacy of combination therapy with vitamin D analogues and systemic treatments. Combination therapy with calcipotriol and methotrexate or calcipotriol and acitretin are effective treatment regimens with level A recommendations. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate ointment in combination with low-dose cyclosporine is an alternative option with a level B recommendation. Because vitamin D analogues are inactivated by UVA and UVB radiation, clinicians should advise their patients to use vitamin D analogues after receiving UVB phototherapy.22

Common adverse effects of vitamin D analogues include burning, pruritus, erythema, and dryness (Table 1). Hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone suppression are extremely rare unless treatment occurs over a large surface area (>30% BSA) or the patient has concurrent renal disease or impairments in calcium metabolism.

Tazarotene—Tazarotene is a topical retinoid that acts by decreasing keratinocyte proliferation, facilitating keratinocyte differentiation, and inhibiting inflammation. Patients with mild to moderate psoriasis are recommended to receive tazarotene treatment for 8 to 12 weeks. In several RCTs, tazarotene gel 0.1% and tazarotene cream 0.1% and 0.05% achieved treatment success in treating plaque psoriasis.23,24

For increased efficacy, clinicians can recommend combination therapy with tazarotene and a TC. Combination therapy with tazarotene and a mid- or high-potency TC for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be more effective than treatment with tazarotene alone.25 Thus, there is a level A recommendation for use of this combination to treat mild to moderate psoriasis. Agents used in combination therapy work synergistically to decrease the length of treatment and increase the duration of remission. The frequency of adverse effects, such as irritation from tazarotene and skin atrophy from TCs, also are reduced.26 Combination therapy with tazarotene and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is another effective option that requires less UV radiation than NB-UVB alone because of the synergistic effects of both treatment modalities.27 Clinicians should counsel patients on the adverse effects of tazarotene, which include local irritation, burning, pruritus, and erythema (Table 1).

Emollients—Emollients are nonmedicated moisturizers that decrease the amount of transepidermal water loss. There is a level B recommendation for use of emollients and TCs in combination for 4 to 8 weeks to treat psoriasis. In fact, combination therapy with mometasone and emollients has demonstrated greater improvement in symptoms of palmoplantar psoriasis (ie, erythema, desquamation, infiltration, BSA involvement) than mometasone alone.28 Emollients are safe options that can be used on all areas of the body and during pregnancy and lactation. Although adverse effects of emollients are rare, clinicians should counsel patients on the risk for contact dermatitis if specific allergies to ingredients/fragrances exist (Table 1).

Salicylic Acid—Salicylic acid is a topical keratolytic that can be used to treat psoriatic plaques. Use of salicylic acid for 8 to 16 weeks has been shown to be effective for mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy of salicylic acid and TCs in patients with 20% or less BSA affected is a safe and effective option with a level B recommendation. Combination therapy with salicylic acid and calcipotriene, however, should be avoided because calcipotriene is inactivated by salicylic acid. It also is recommended that salicylic acid application follow phototherapy when both treatment modalities are used in combination.29,30 Clinicians should be cautious about using salicylic acid in patients with renal or hepatic disease because of the increased risk for salicylate toxicity (Table 1).

Anthralin—Anthralin is a synthetic hydrocarbon derivative that has been shown to reduce inflammation and normalize keratinocyte proliferation through an unknown mechanism. It is recommended that patients with mild to moderate psoriasis receive anthralin treatment for 8 to 12 weeks, with a maximum application time of 2 hours per day. Combination therapy of excimer laser and anthralin has been shown to be more effective in treating psoriasis than anthralin alone.31 Therefore, clinicians have the option of including excimer laser therapy for additional disease control. Anthralin should be avoided on the face, flexural regions, and highly visible areas because of potential skin staining (Table 1). Other adverse effects include application-site burning and erythema.

Coal Tar—Coal tar is a heterogenous mixture of aromatic hydrocarbons that is an effective treatment of psoriasis because of its inherent anti-inflammatory and keratoplastic properties. There is high-quality evidence supporting a level A recommendation for coal tar use in mild to moderate psoriasis. Combination therapy with NB-UVB and coal tar (also known as Goeckerman therapy) is a recommended treatment option with a quicker onset of action and improved outcomes compared with NB-UVB therapy alone.32,33 Adverse events of coal tar include application-site irritation, folliculitis, contact dermatitis, phototoxicity, and skin pigmentation (Table 1).

Conclusion

Topical medications are versatile treatment options that can be utilized as monotherapy or adjunct therapy for mild to severe psoriasis. Benefits of topical agents include minimal required monitoring, few contraindications, and direct localized effect on plaques. Therefore, side effects with topical agent use rarely are systemic. Medication interactions are less of a concern with topical therapies; thus, they have better safety profiles compared with systemic therapies. This clinical review summarizes the recently published evidence-based guidelines from the AAD and NPF on the use of topical agents in psoriasis and may be a useful guiding framework for clinicians in their everyday practice.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study. J Med Econ. 2018:1-9.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Svendsen MT, Jeyabalan J, Andersen KE, et al. Worldwide utilization of topical remedies in treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:374-383.

- Day A, Abramson AK, Patel M, et al. The spectrum of oculocutaneous disease: part II. neoplastic and drug-related causes of oculocutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:821.e821-819.

- Choi JW, Choi JW, Kwon IH, et al. High-concentration (20 μg g-¹) tacalcitol ointment in the treatment of facial psoriasis: an 8-week open-label clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1359-1364.

- Hashim PW, Chima M, Kim HJ, et al. Crisaborole 2% ointment for the treatment of intertriginous, anogenital, and facial psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:360-365.

- Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70:327-332.

- Iversen L, Jakobsen HB. Patient preferences for topical psoriasis treatments are diverse and difficult to predict. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:273-285.

- Clobex Package insert. Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2012.

- Kenalog-10 Injection. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2018.

- Mason J, Mason AR, Cork MJ. Topical preparations for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:351-364.

- Koo J, Cuffie CA, Tanner DJ, et al. Mometasone furoate 0.1%-salicylic acid 5% ointment versus mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a multicenter study. Clin Ther. 1998;20:283-291.

- Tiplica GS, Salavastru CM. Mometasone furoate 0.1% and salicylic acid 5% vs. mometasone furoate 0.1% as sequential local therapy in psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:905-912.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Strober BE, Bissonnette R, Fiorentino D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologic agents for the treatment of psoriasis in a real-world setting: results from a large, prospective, observational study (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry [PSOLAR]). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:851-861.e854.

- Castela E, Archier E, Devaux S, et al. Topical corticosteroids in plaque psoriasis: a systematic review of risk of adrenal axis suppression and skin atrophy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):47-51.

- Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Honma M, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after long-term topical corticosteroid treatment in a psoriasis patient. J Dermatol. 2012;39:887-888.

- el Maghraoui A, Tabache F, Bezza A, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after topical corticosteroid therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:233.

- Gribetz C, Ling M, Lebwohl M, et al. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of intertriginous psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:731-738.

- Lebwohl M, Freeman AK, Chapman MS, et al. Tacrolimus ointment is effective for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:723-730.

- Paller AS, Fölster-Holst R, Chen SC, et al. No evidence of increased cancer incidence in children using topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:375-381.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Lebwohl M, Ast E, Callen JP, et al. Once-daily tazarotene gel versus twice-daily fluocinonide cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:705-711.

- Weinstein GD, Koo JY, Krueger GG, et al. Tazarotene cream in the treatment of psoriasis: two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene creams 0.05% and 0.1% applied once daily for 12 weeks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:760-767.

- Lebwohl M, Lombardi K, Tan MH. Duration of improvement in psoriasis after treatment with tazarotene 0.1% gel plus clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment: comparison of maintenance treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:64-66.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Koo JY, Lowe NJ, Lew-Kaya DA, et al. Tazarotene plus UVB phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:821-828.

- Cassano N, Mantegazza R, Battaglini S, et al. Adjuvant role of a new emollient cream in patients with palmar and/or plantar psoriasis: a pilot randomized open-label study. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:789-792.

- Kristensen B, Kristensen O. Topical salicylic acid interferes with UVB therapy for psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:37-40.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Rogalski C, Grunewald S, Schetschorke M, et al. Treatment of plaque-type psoriasis with the 308 nm excimer laser in combination with dithranol or calcipotriol. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:184-190.

- Bagel J. LCD plus NB-UVB reduces time to improvement of psoriasis vs. NB-UVB alone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:351-357.

- Abdallah MA, El-Khateeb EA, Abdel-Rahman SH. The influence of psoriatic plaques pretreatment with crude coal tar vs. petrolatum on the efficacy of narrow-band ultraviolet B: a half-vs.-half intra-individual double-blinded comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:226-230.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study. J Med Econ. 2018:1-9.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Svendsen MT, Jeyabalan J, Andersen KE, et al. Worldwide utilization of topical remedies in treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:374-383.

- Day A, Abramson AK, Patel M, et al. The spectrum of oculocutaneous disease: part II. neoplastic and drug-related causes of oculocutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:821.e821-819.

- Choi JW, Choi JW, Kwon IH, et al. High-concentration (20 μg g-¹) tacalcitol ointment in the treatment of facial psoriasis: an 8-week open-label clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1359-1364.

- Hashim PW, Chima M, Kim HJ, et al. Crisaborole 2% ointment for the treatment of intertriginous, anogenital, and facial psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:360-365.

- Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70:327-332.

- Iversen L, Jakobsen HB. Patient preferences for topical psoriasis treatments are diverse and difficult to predict. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:273-285.

- Clobex Package insert. Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2012.

- Kenalog-10 Injection. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2018.

- Mason J, Mason AR, Cork MJ. Topical preparations for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:351-364.

- Koo J, Cuffie CA, Tanner DJ, et al. Mometasone furoate 0.1%-salicylic acid 5% ointment versus mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a multicenter study. Clin Ther. 1998;20:283-291.

- Tiplica GS, Salavastru CM. Mometasone furoate 0.1% and salicylic acid 5% vs. mometasone furoate 0.1% as sequential local therapy in psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:905-912.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Strober BE, Bissonnette R, Fiorentino D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologic agents for the treatment of psoriasis in a real-world setting: results from a large, prospective, observational study (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry [PSOLAR]). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:851-861.e854.

- Castela E, Archier E, Devaux S, et al. Topical corticosteroids in plaque psoriasis: a systematic review of risk of adrenal axis suppression and skin atrophy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):47-51.

- Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Honma M, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after long-term topical corticosteroid treatment in a psoriasis patient. J Dermatol. 2012;39:887-888.

- el Maghraoui A, Tabache F, Bezza A, et al. Femoral head osteonecrosis after topical corticosteroid therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:233.

- Gribetz C, Ling M, Lebwohl M, et al. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of intertriginous psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:731-738.

- Lebwohl M, Freeman AK, Chapman MS, et al. Tacrolimus ointment is effective for facial and intertriginous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:723-730.

- Paller AS, Fölster-Holst R, Chen SC, et al. No evidence of increased cancer incidence in children using topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:375-381.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Lebwohl M, Ast E, Callen JP, et al. Once-daily tazarotene gel versus twice-daily fluocinonide cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:705-711.

- Weinstein GD, Koo JY, Krueger GG, et al. Tazarotene cream in the treatment of psoriasis: two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene creams 0.05% and 0.1% applied once daily for 12 weeks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:760-767.

- Lebwohl M, Lombardi K, Tan MH. Duration of improvement in psoriasis after treatment with tazarotene 0.1% gel plus clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment: comparison of maintenance treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:64-66.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Koo JY, Lowe NJ, Lew-Kaya DA, et al. Tazarotene plus UVB phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:821-828.

- Cassano N, Mantegazza R, Battaglini S, et al. Adjuvant role of a new emollient cream in patients with palmar and/or plantar psoriasis: a pilot randomized open-label study. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:789-792.

- Kristensen B, Kristensen O. Topical salicylic acid interferes with UVB therapy for psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:37-40.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Rogalski C, Grunewald S, Schetschorke M, et al. Treatment of plaque-type psoriasis with the 308 nm excimer laser in combination with dithranol or calcipotriol. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:184-190.

- Bagel J. LCD plus NB-UVB reduces time to improvement of psoriasis vs. NB-UVB alone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:351-357.

- Abdallah MA, El-Khateeb EA, Abdel-Rahman SH. The influence of psoriatic plaques pretreatment with crude coal tar vs. petrolatum on the efficacy of narrow-band ultraviolet B: a half-vs.-half intra-individual double-blinded comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:226-230.

Practice Points

- Topical medications collectively represent the most common form of psoriasis treatment. Depending on disease severity and distribution, topical agents can be used as monotherapy or adjunct therapy, offering the benefit of localized treatment without systemic side effects.

- Dermatologists should base the selection of an appropriate topical medication on factors including adverse effects, potency, vehicle, and anatomic localization of disease.

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for Psoriasis With Attention to Comorbidities

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

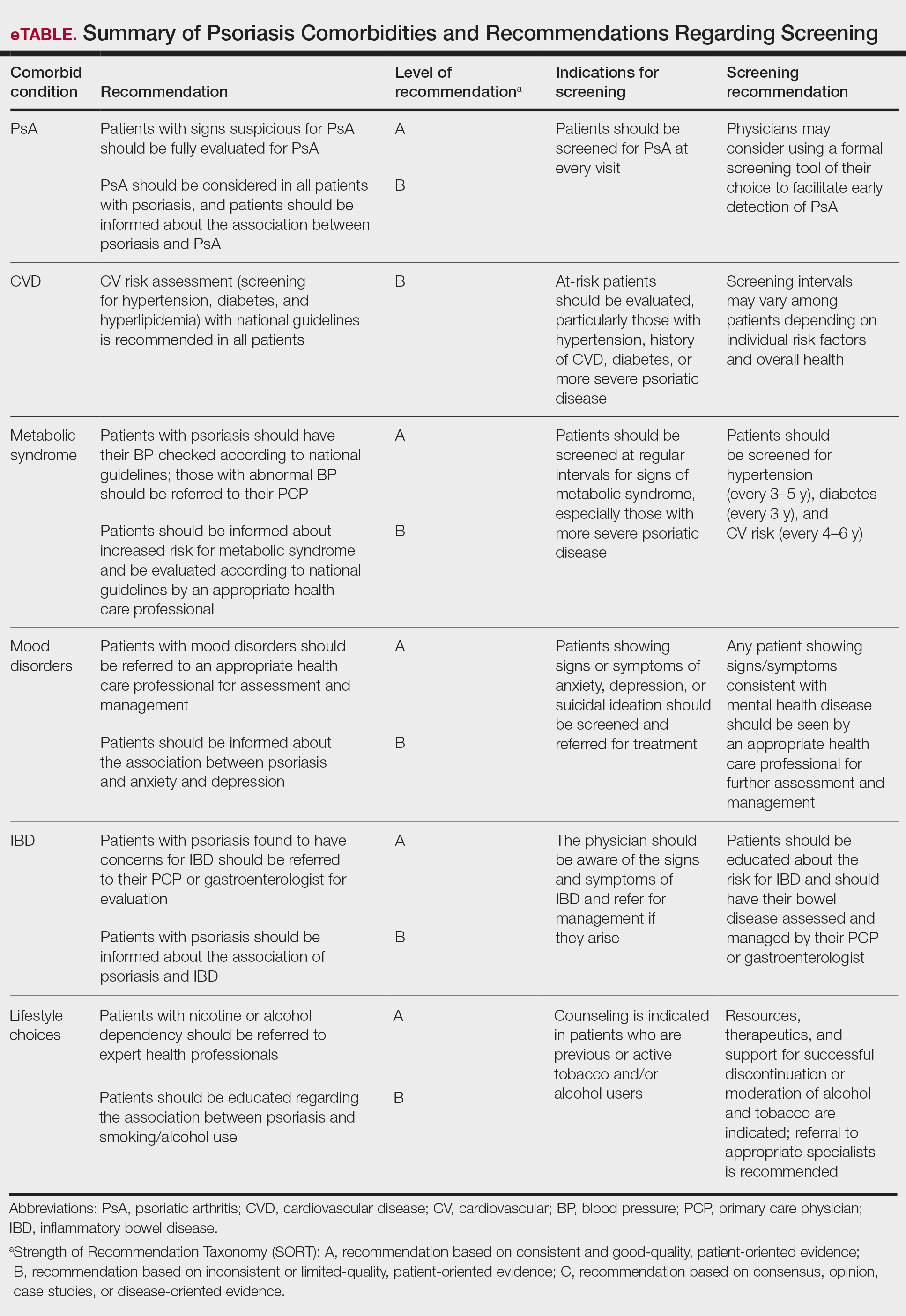

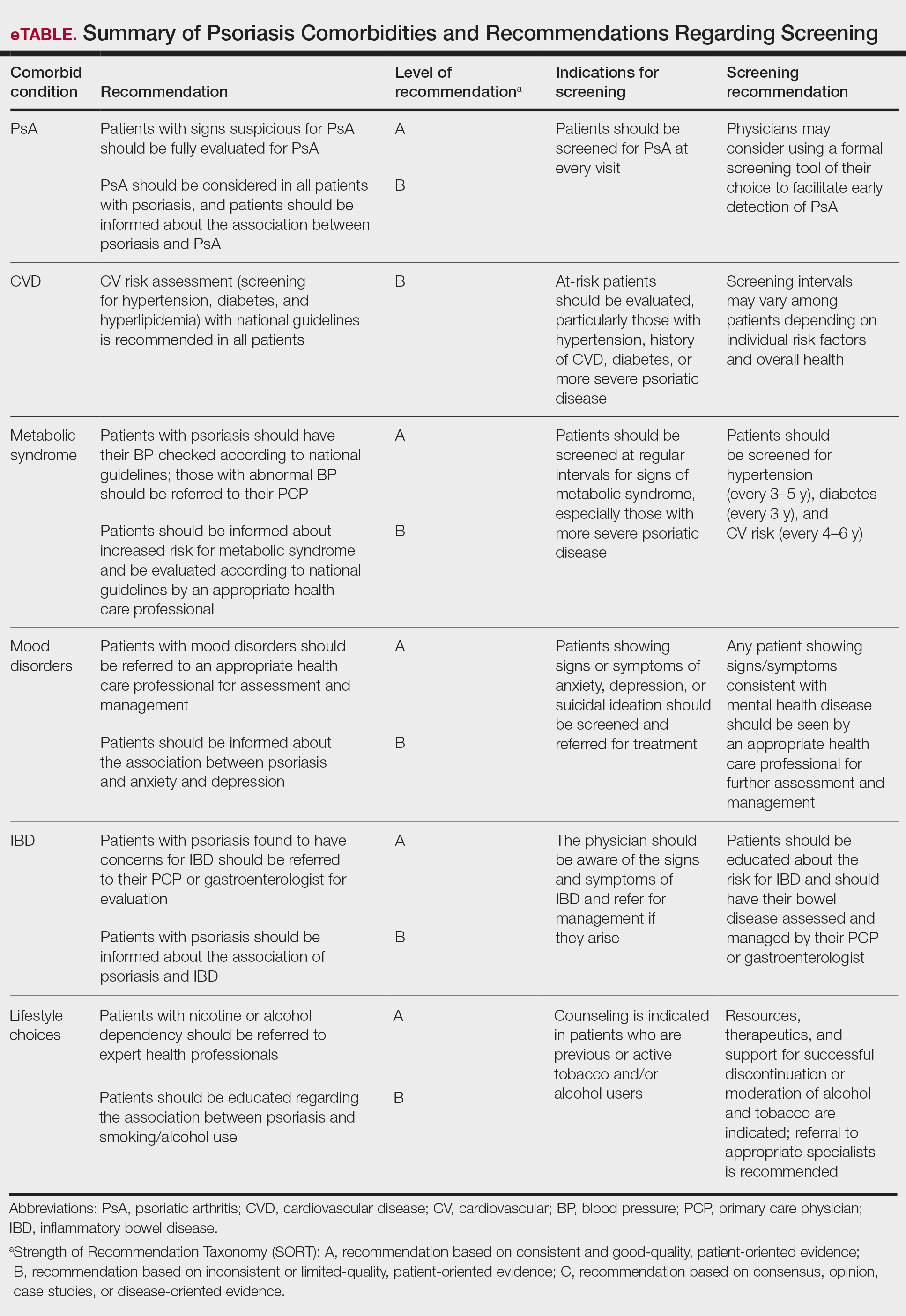

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

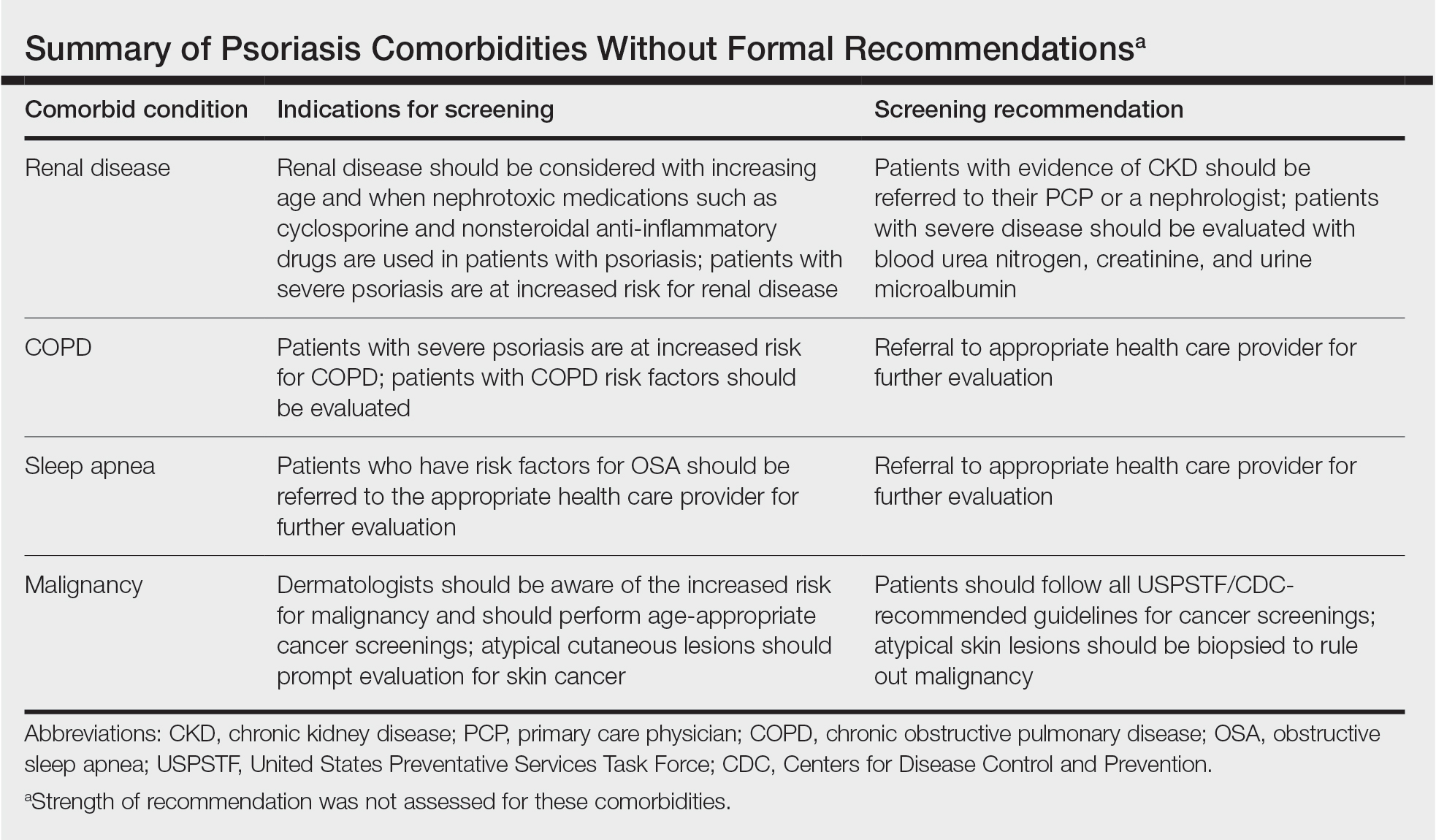

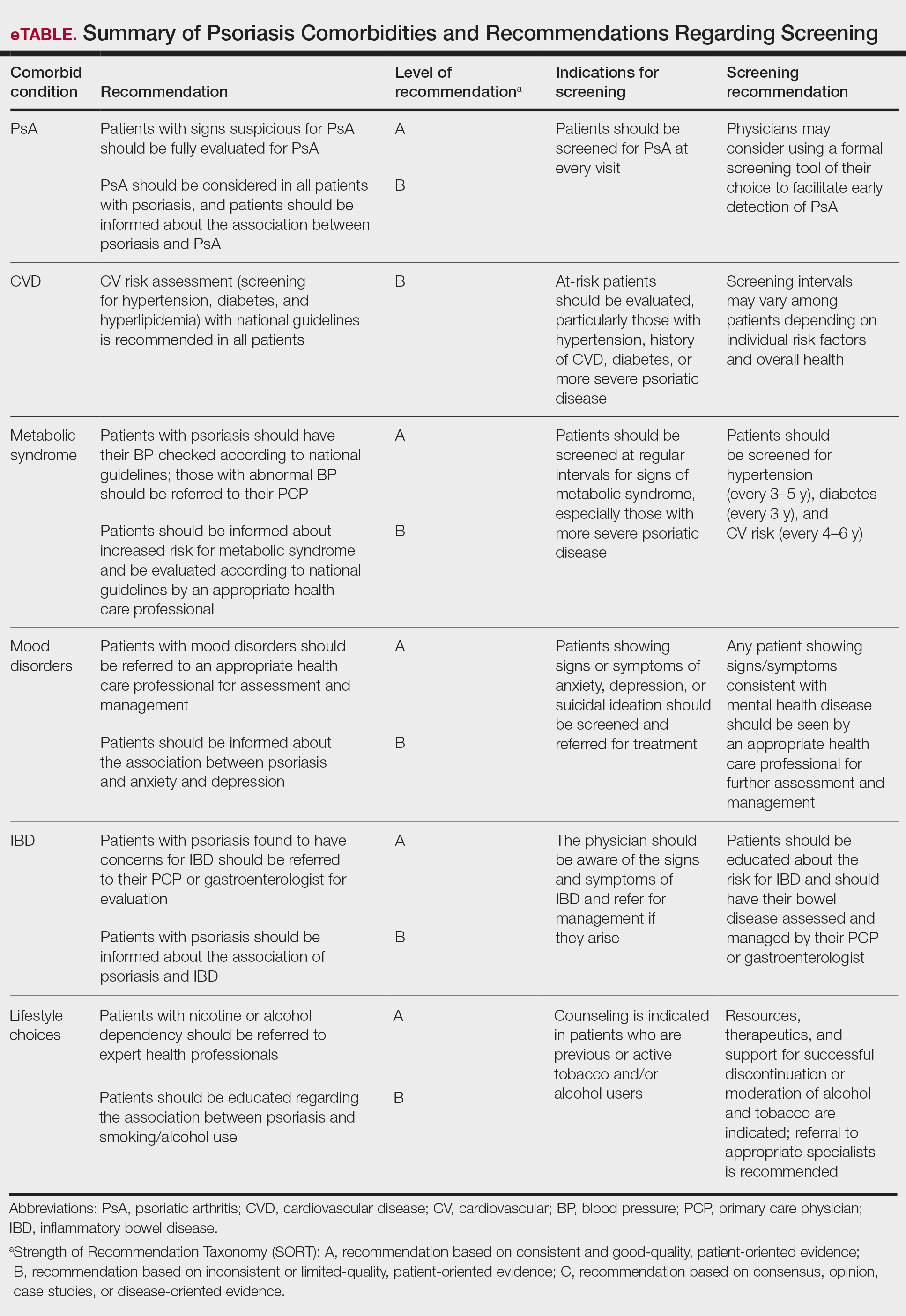

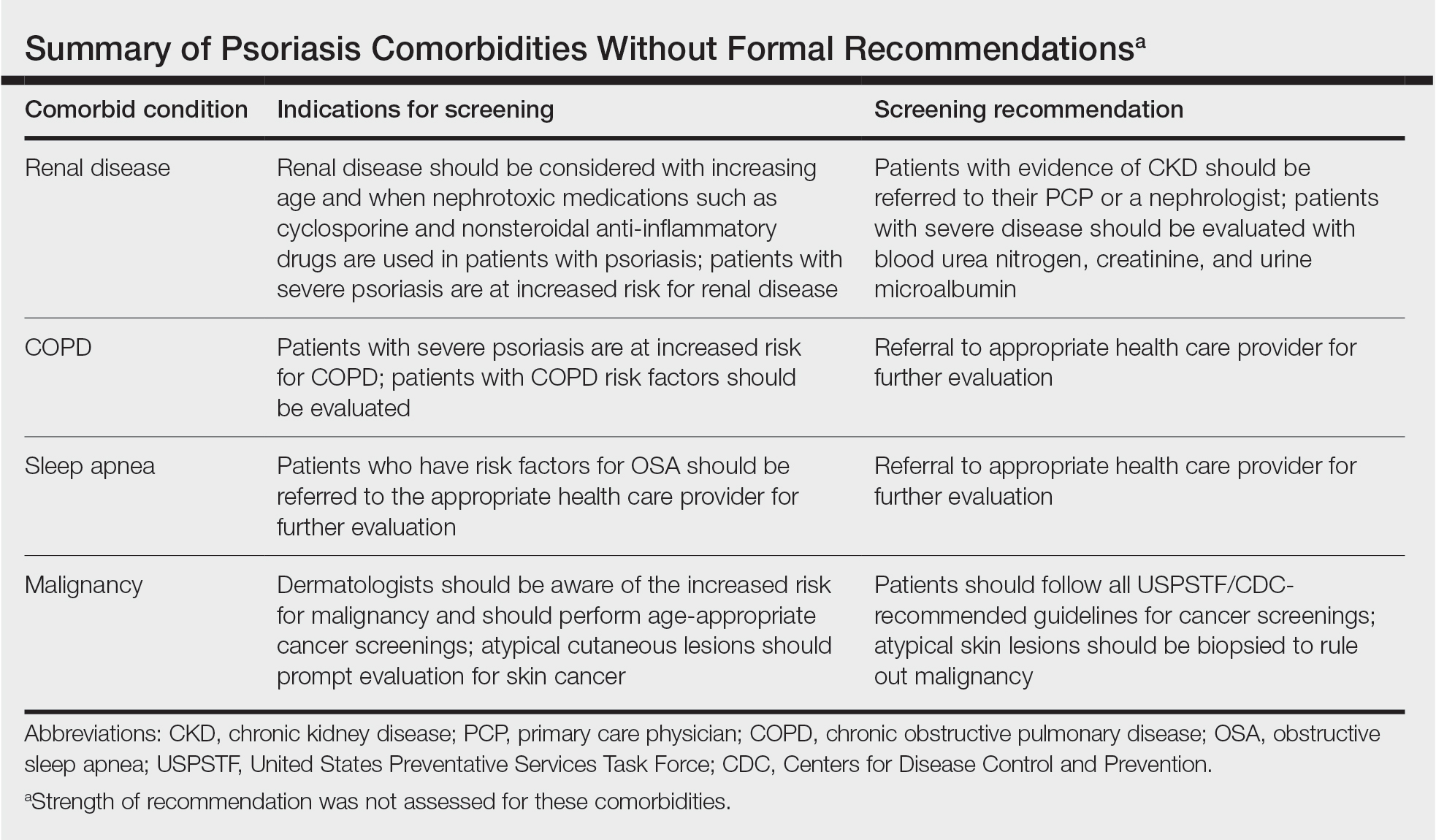

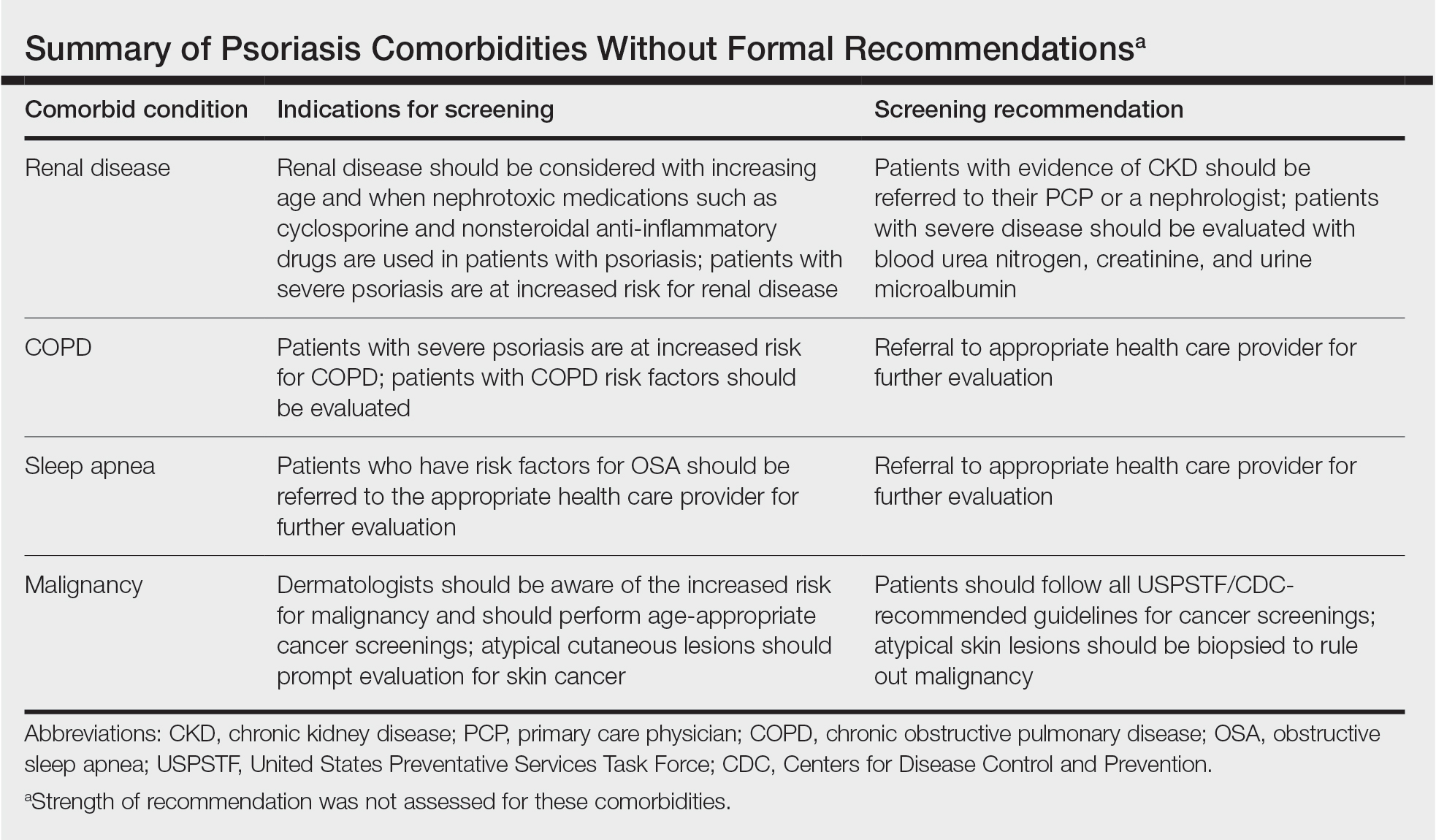

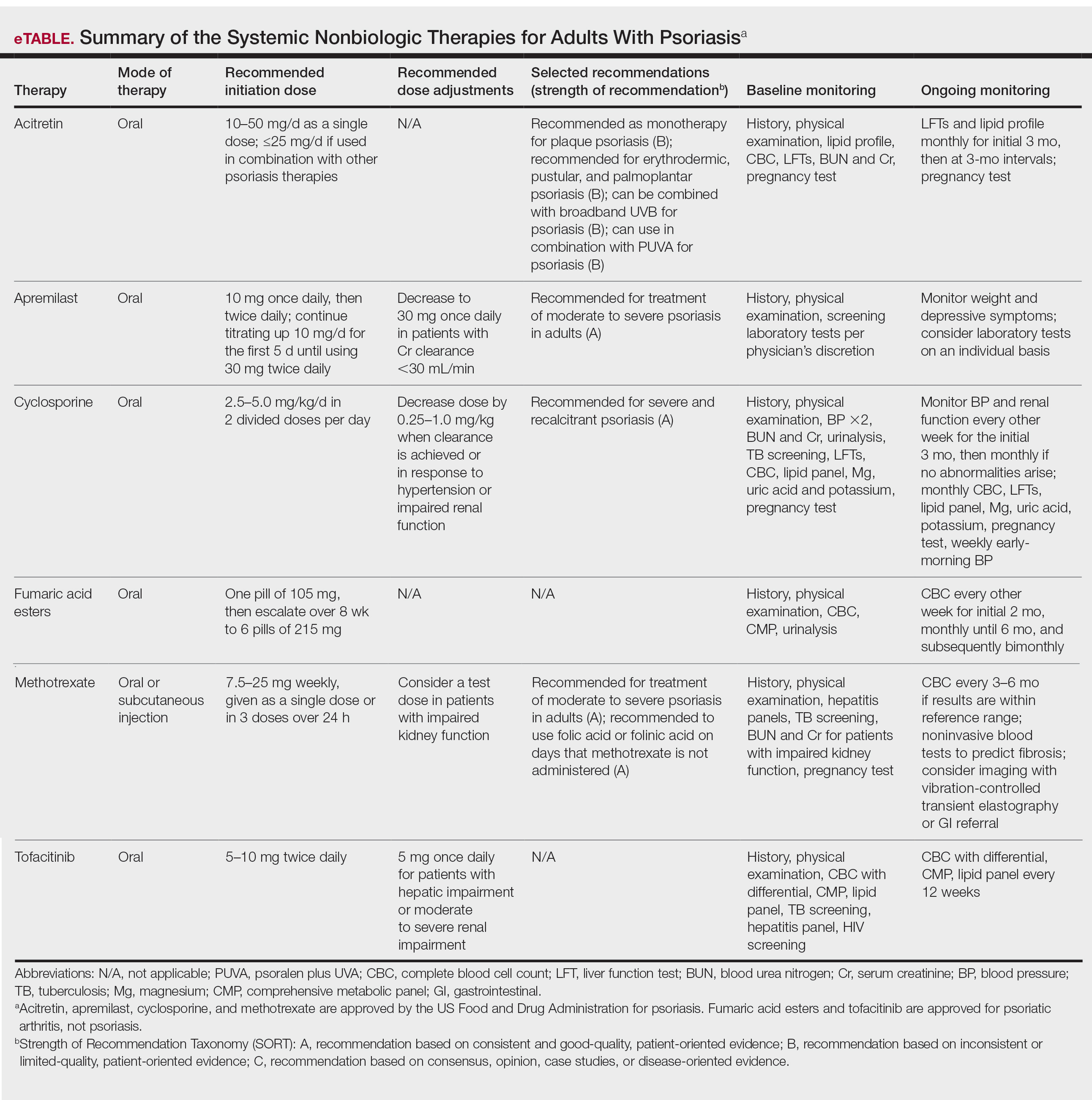

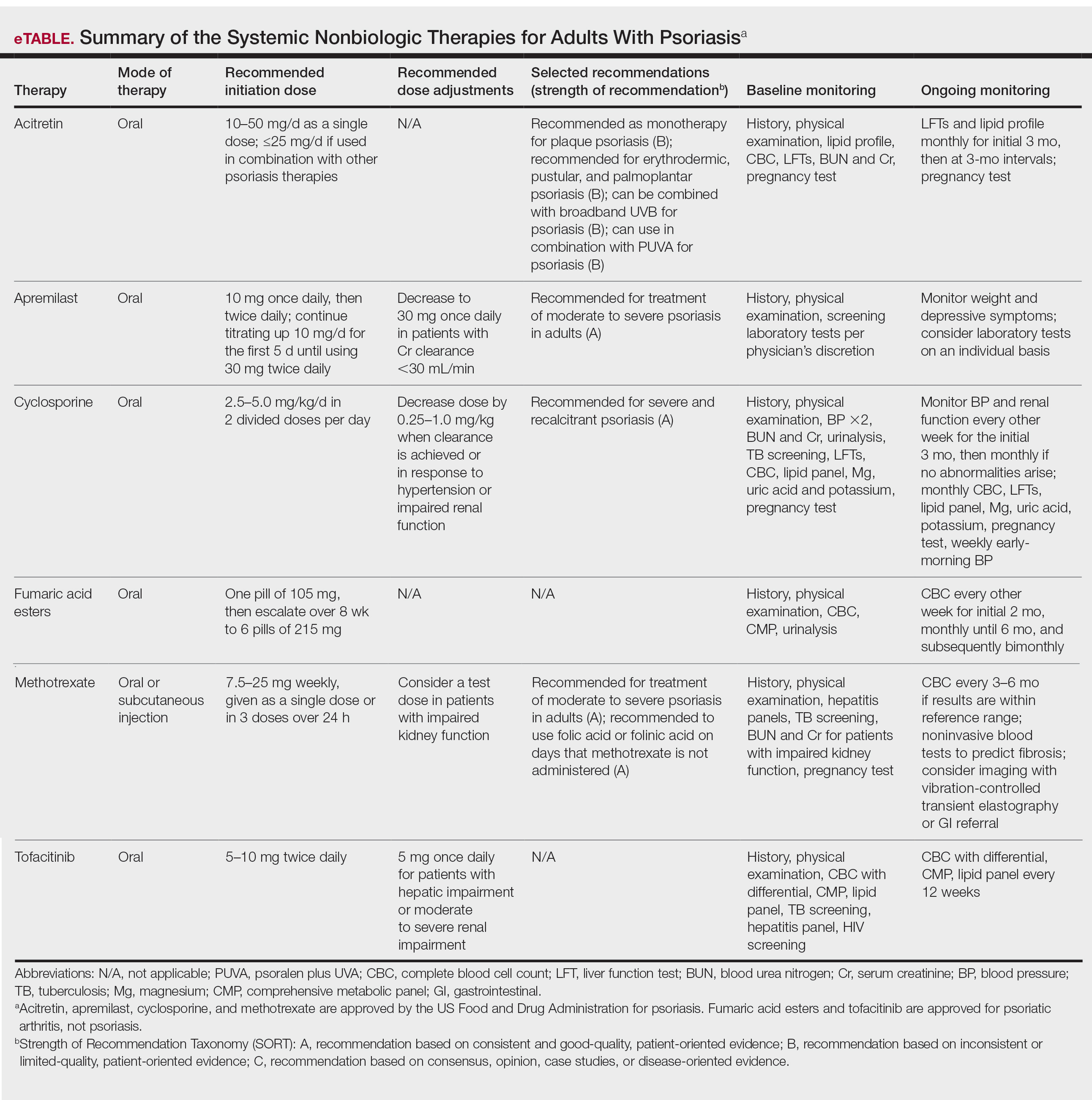

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

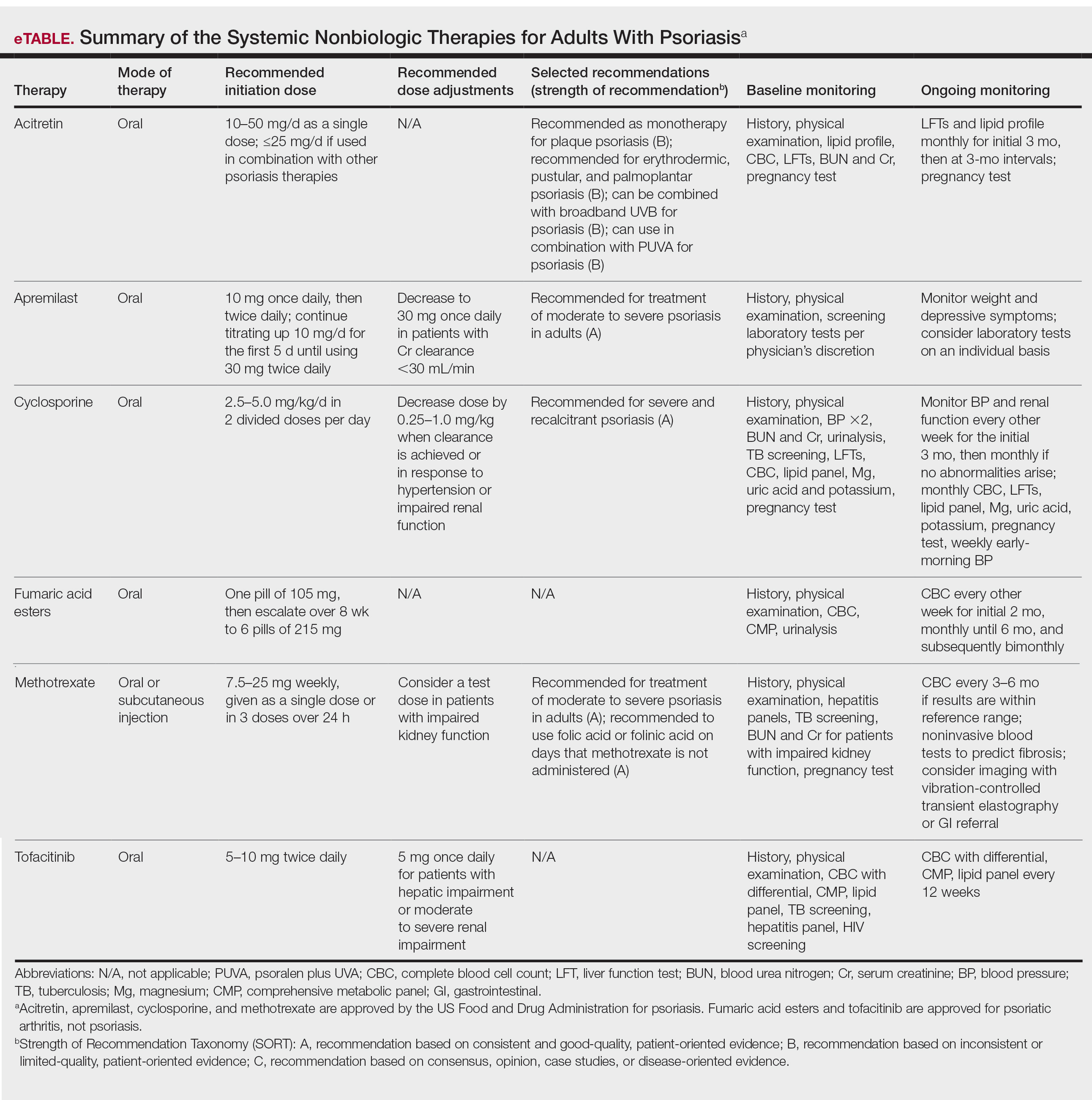

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.