User login

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

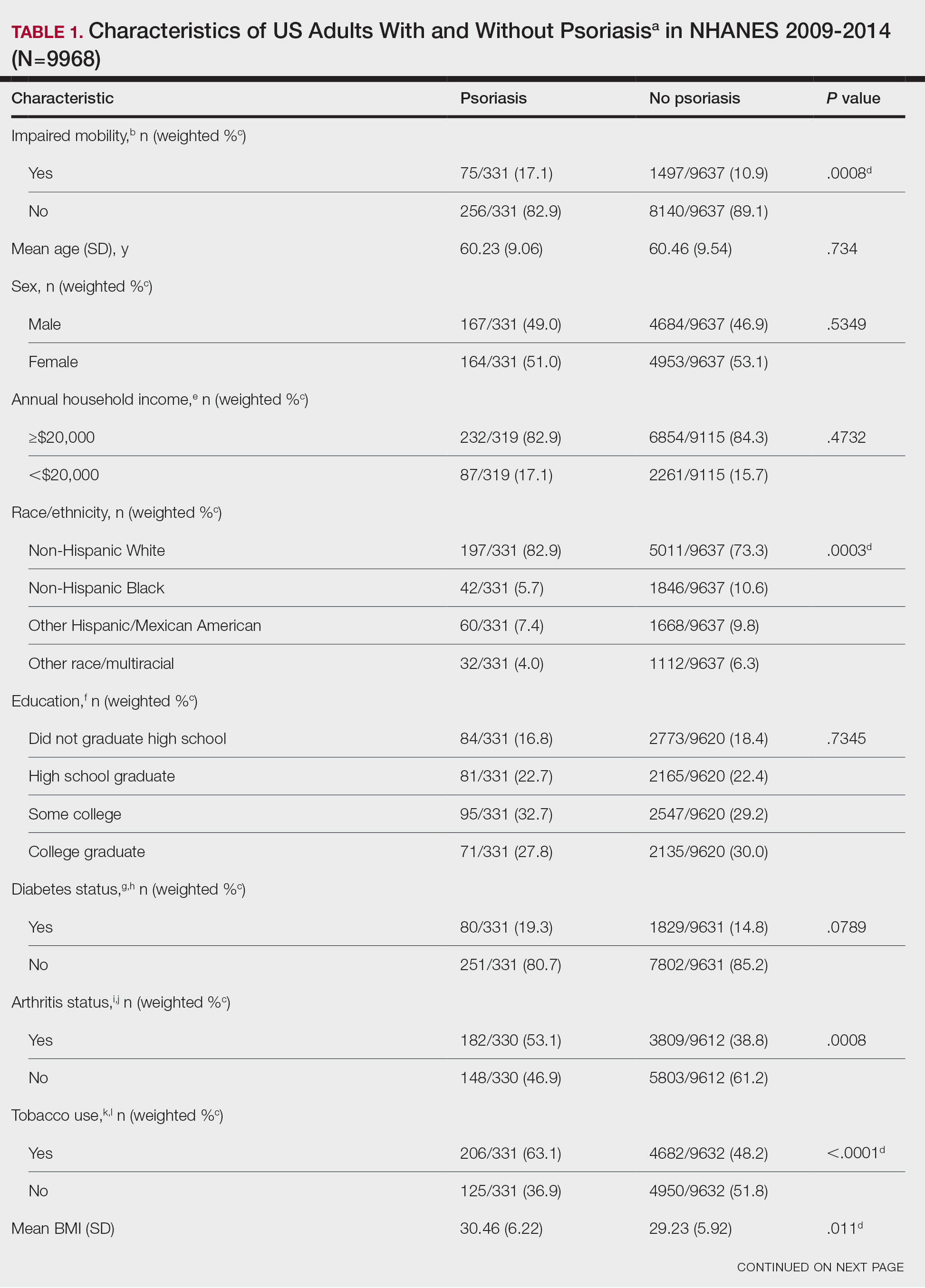

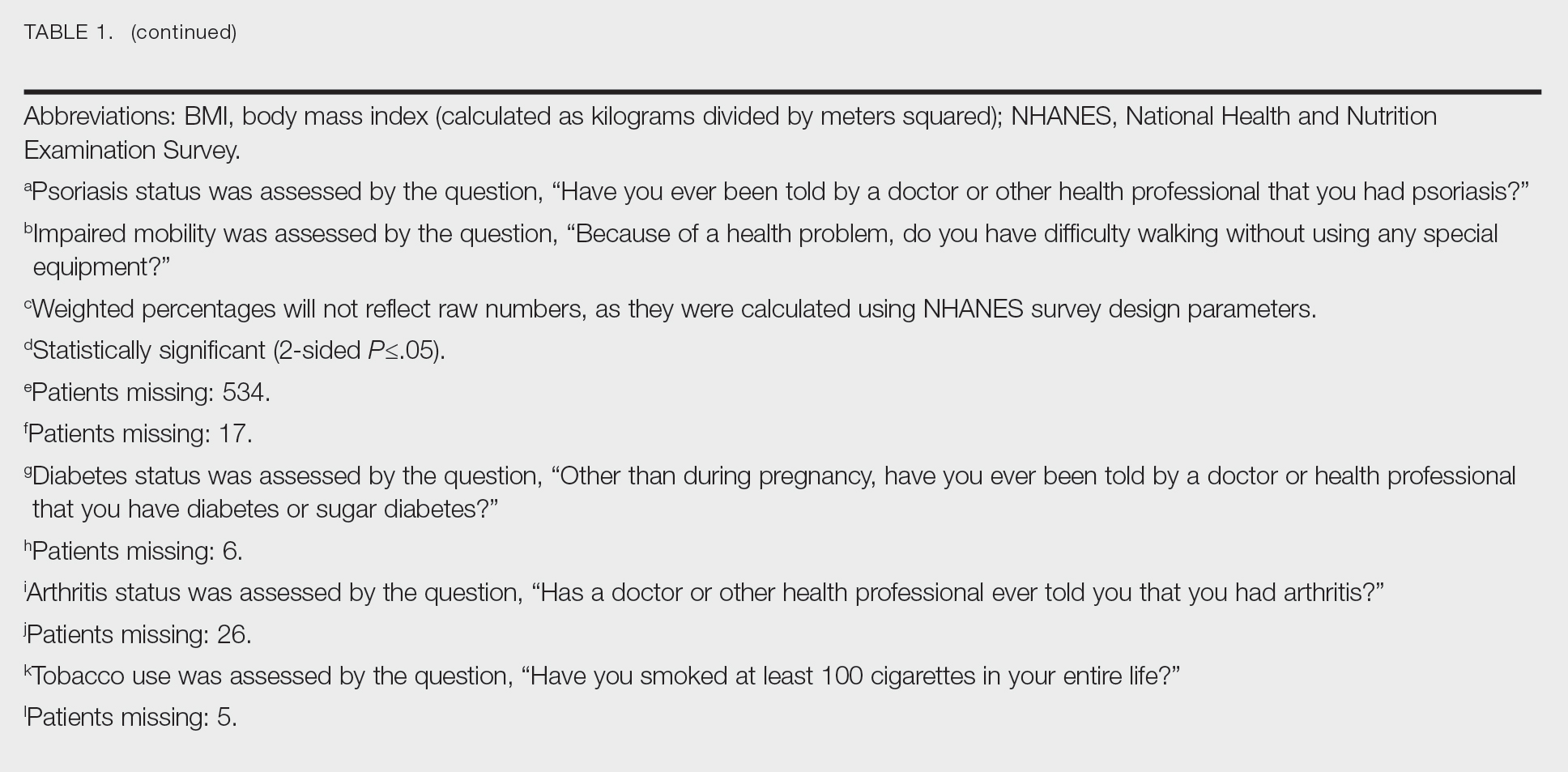

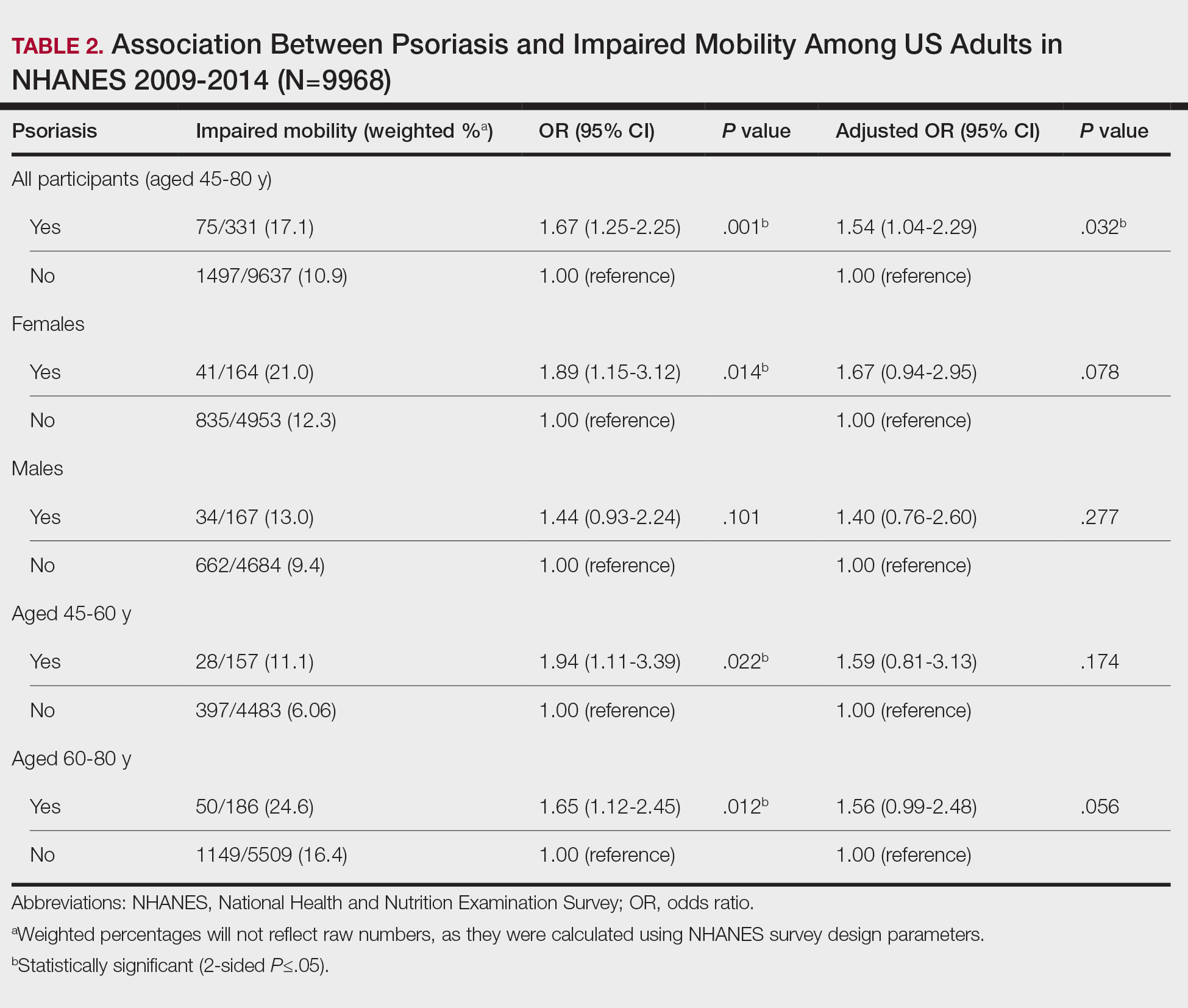

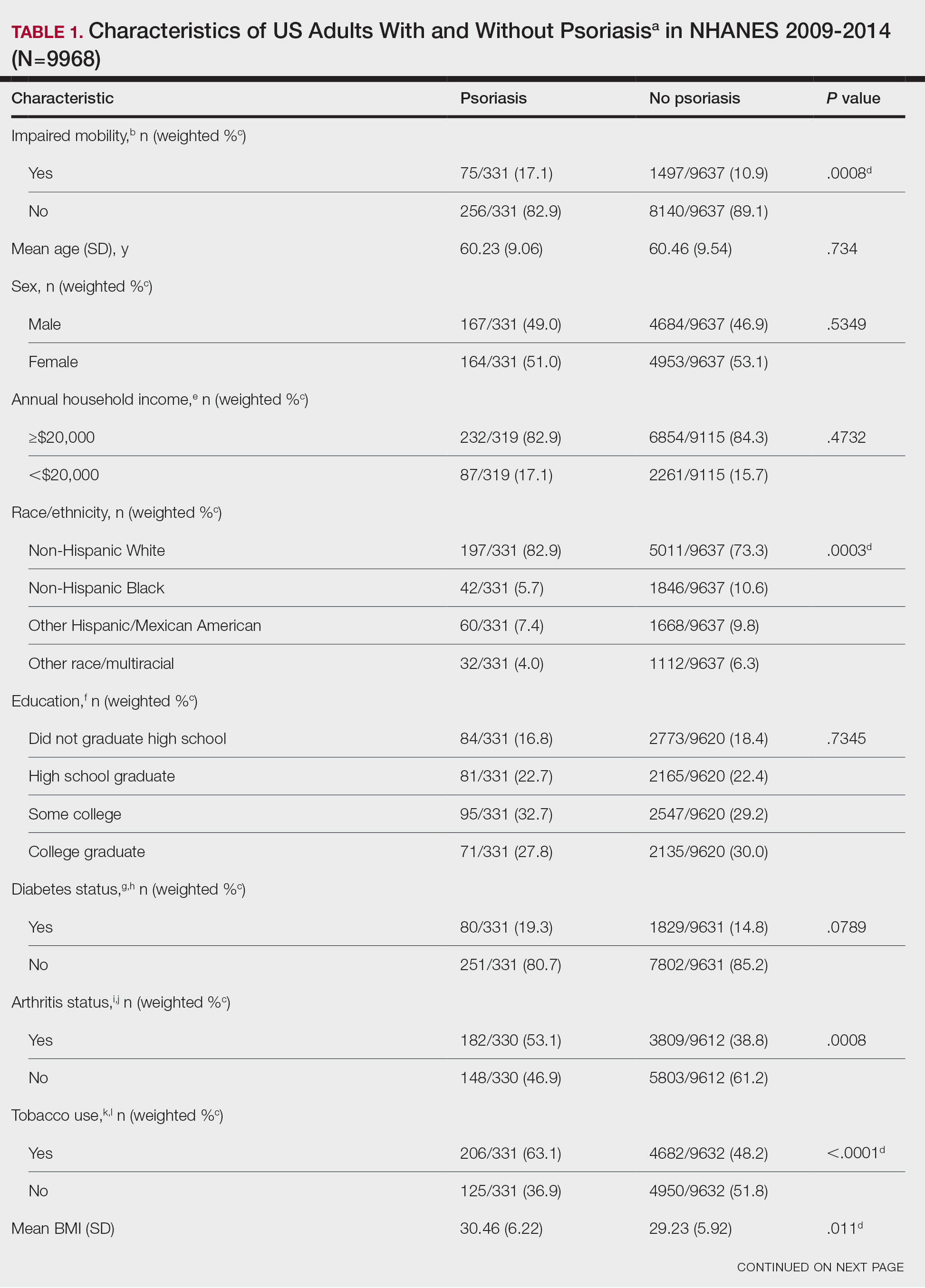

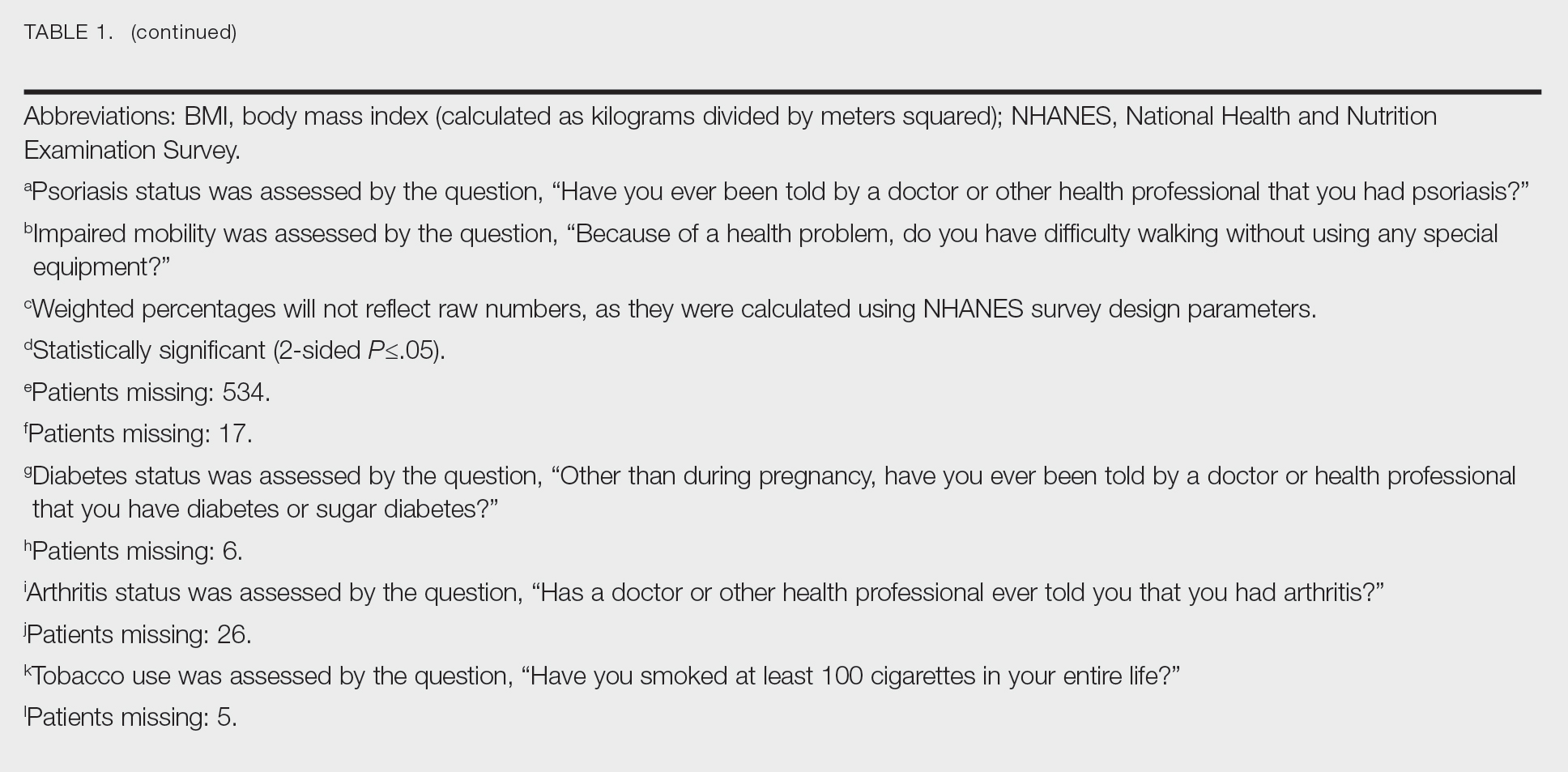

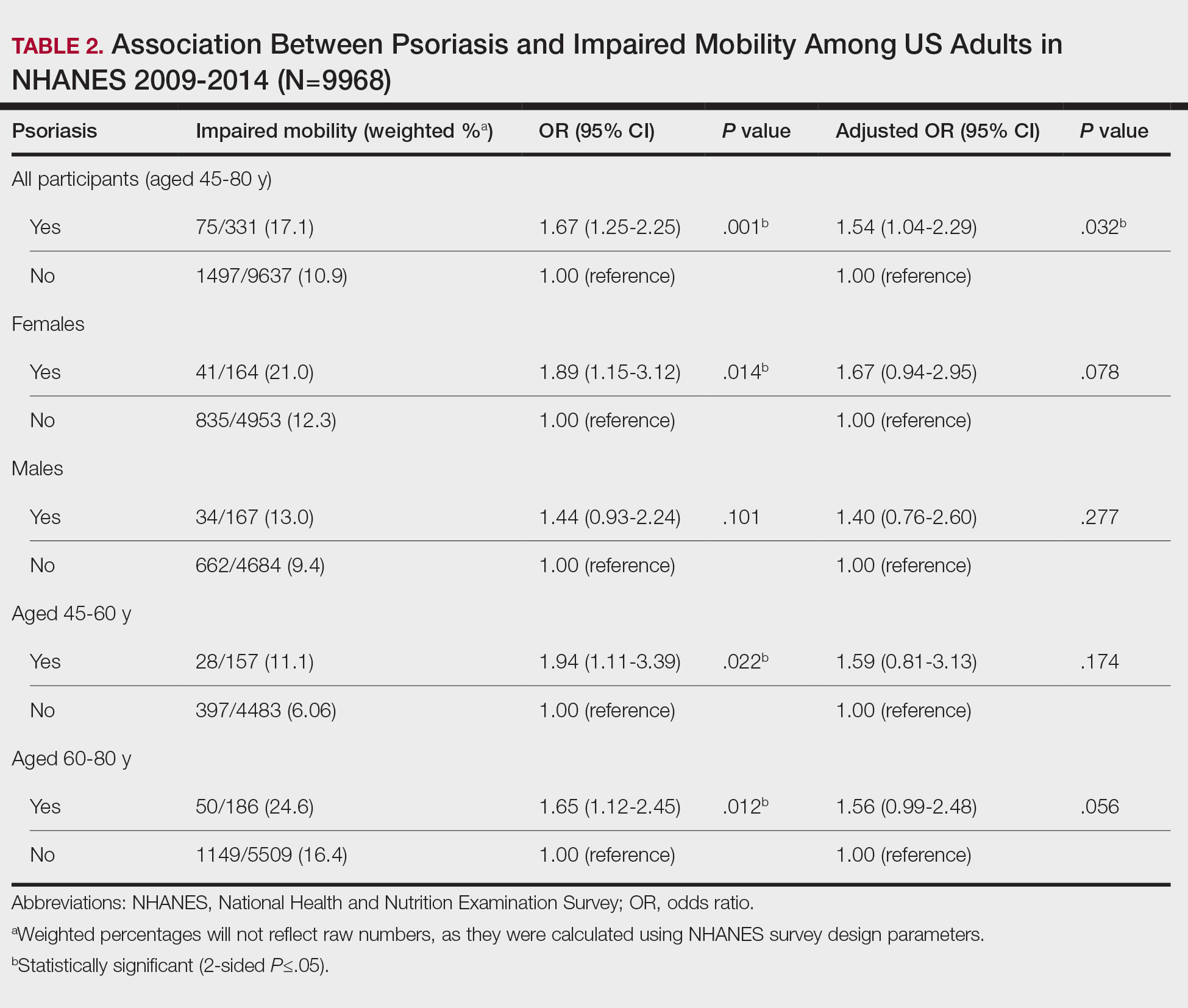

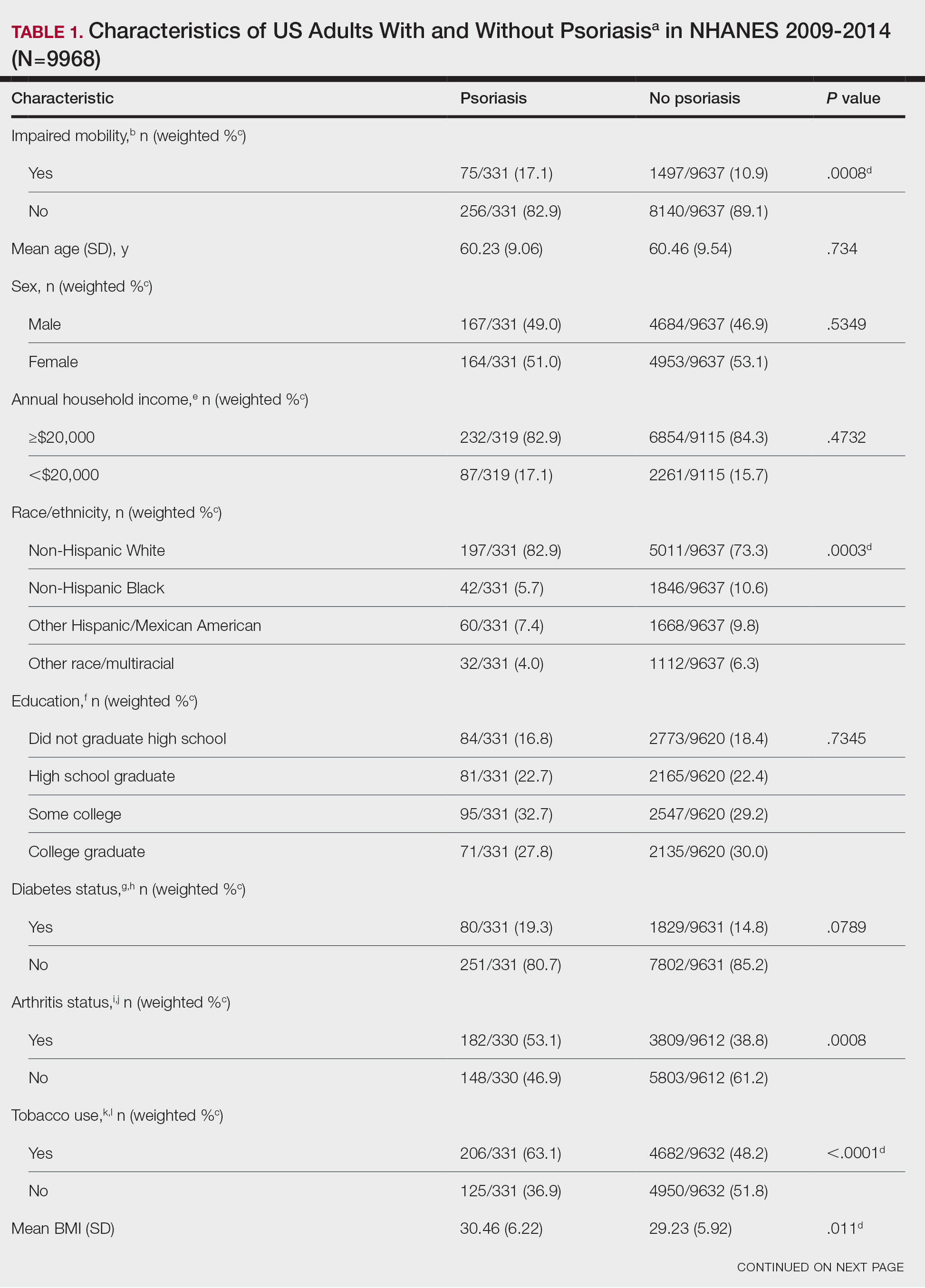

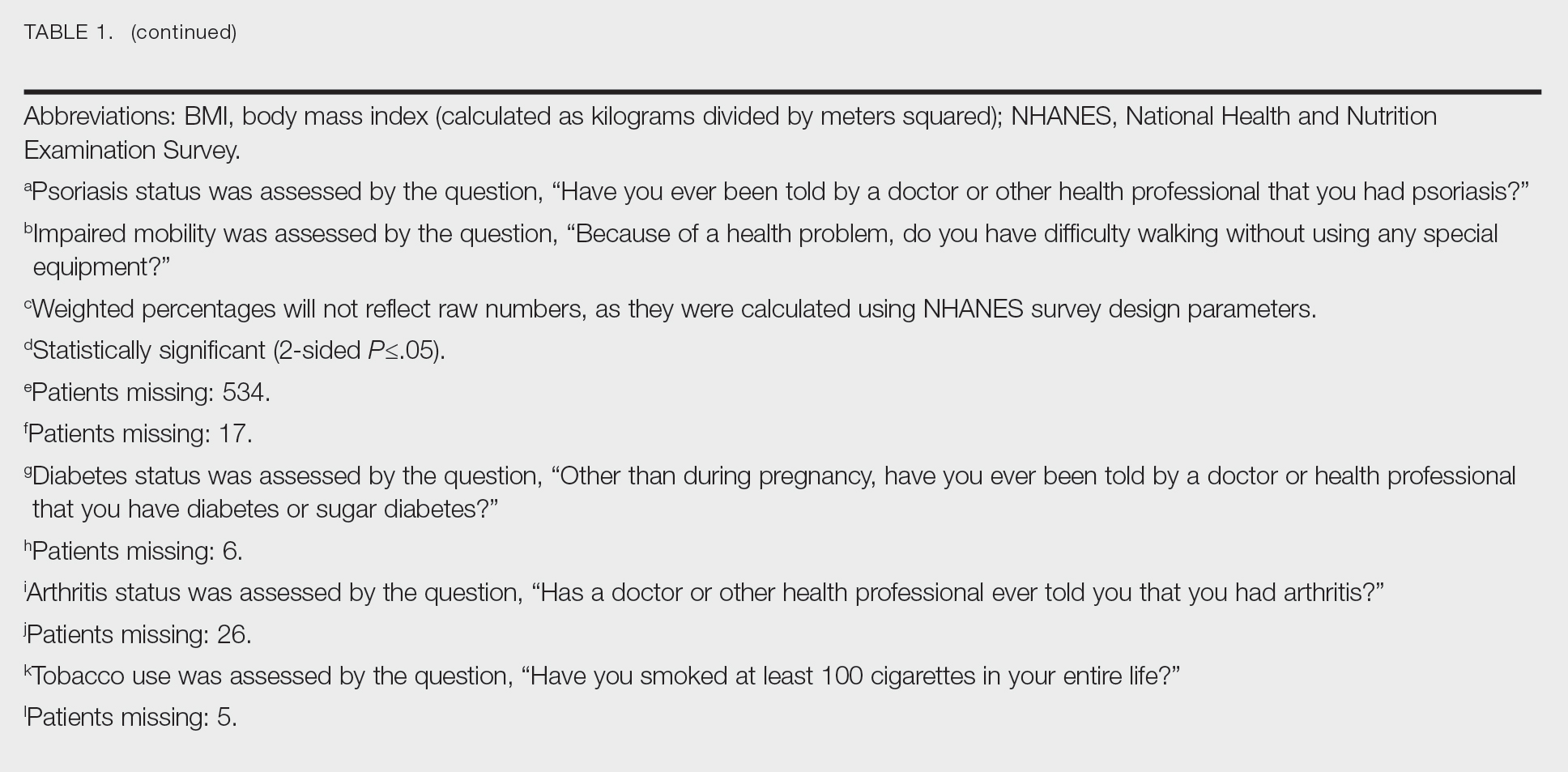

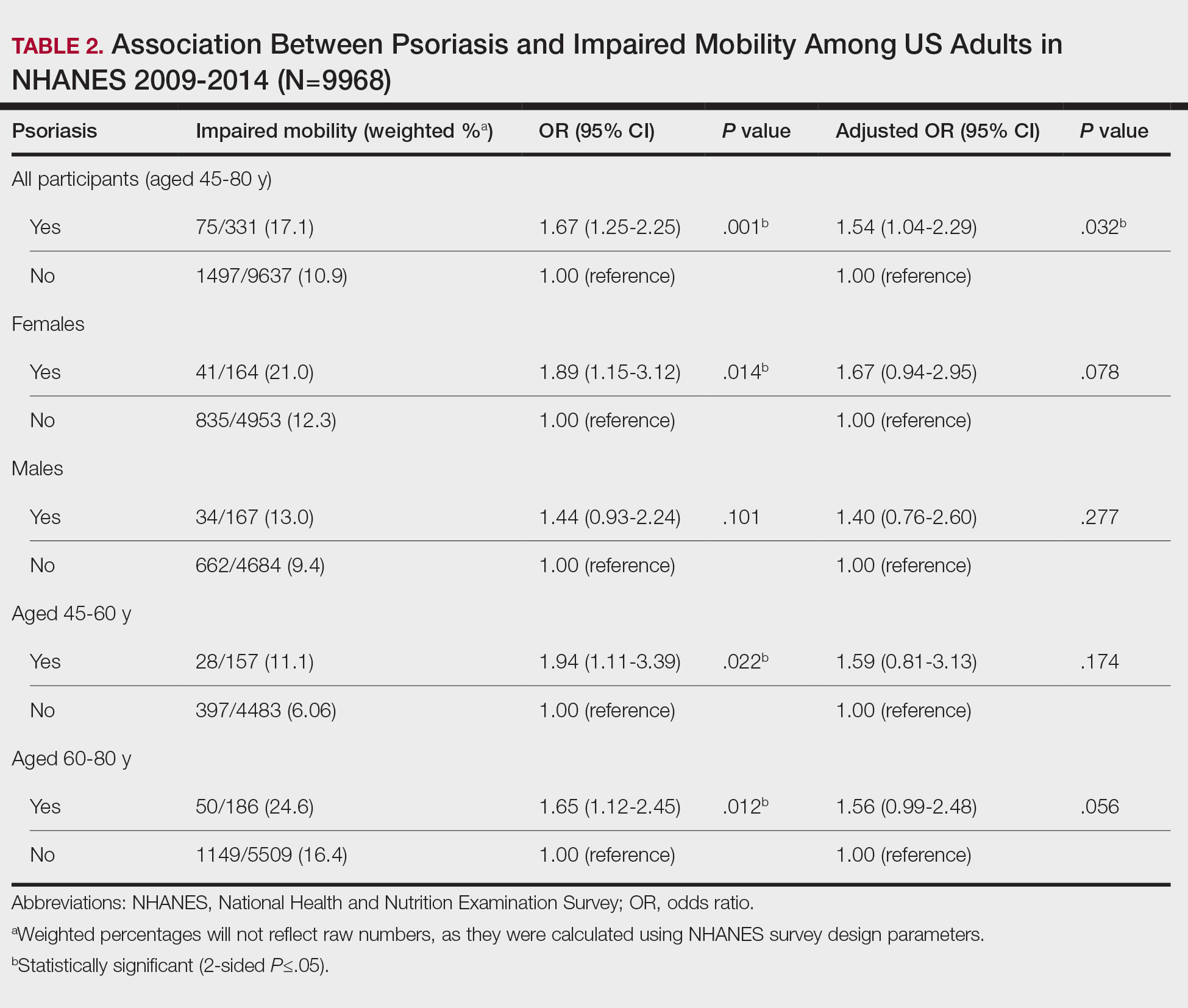

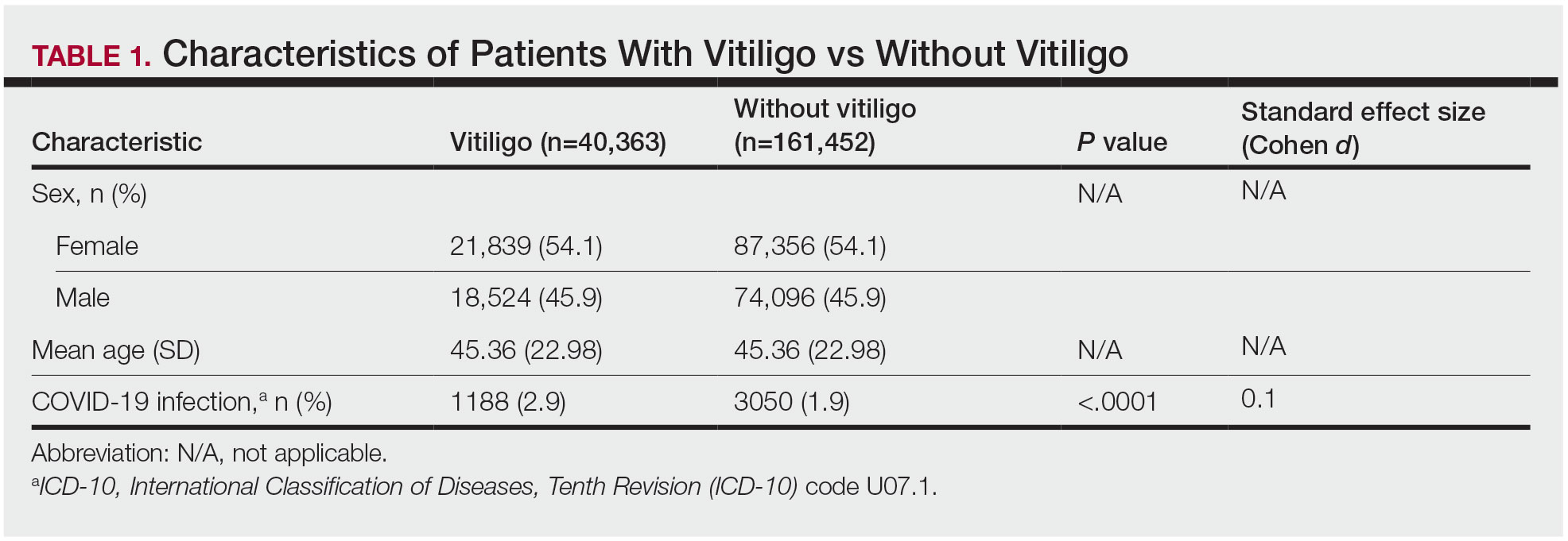

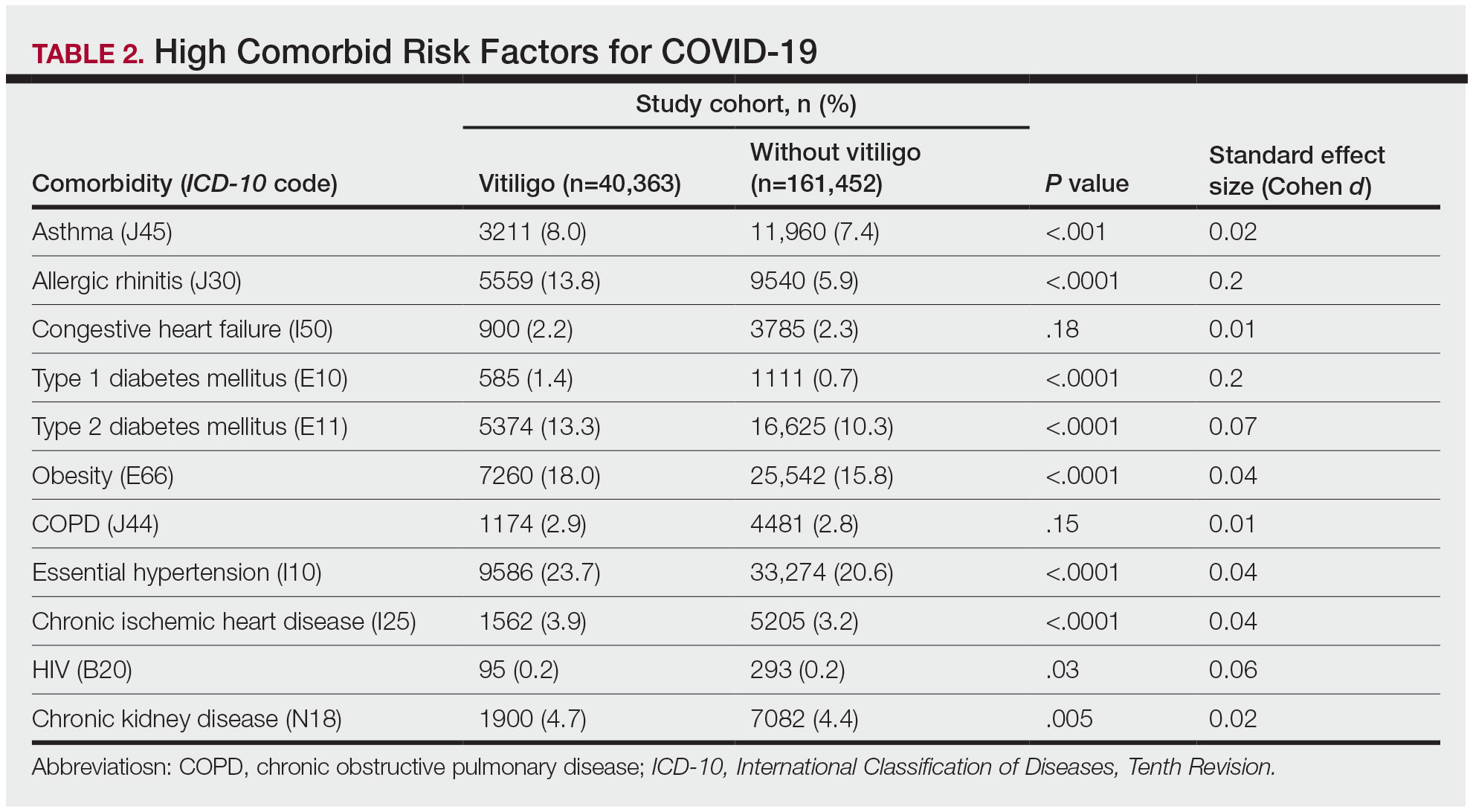

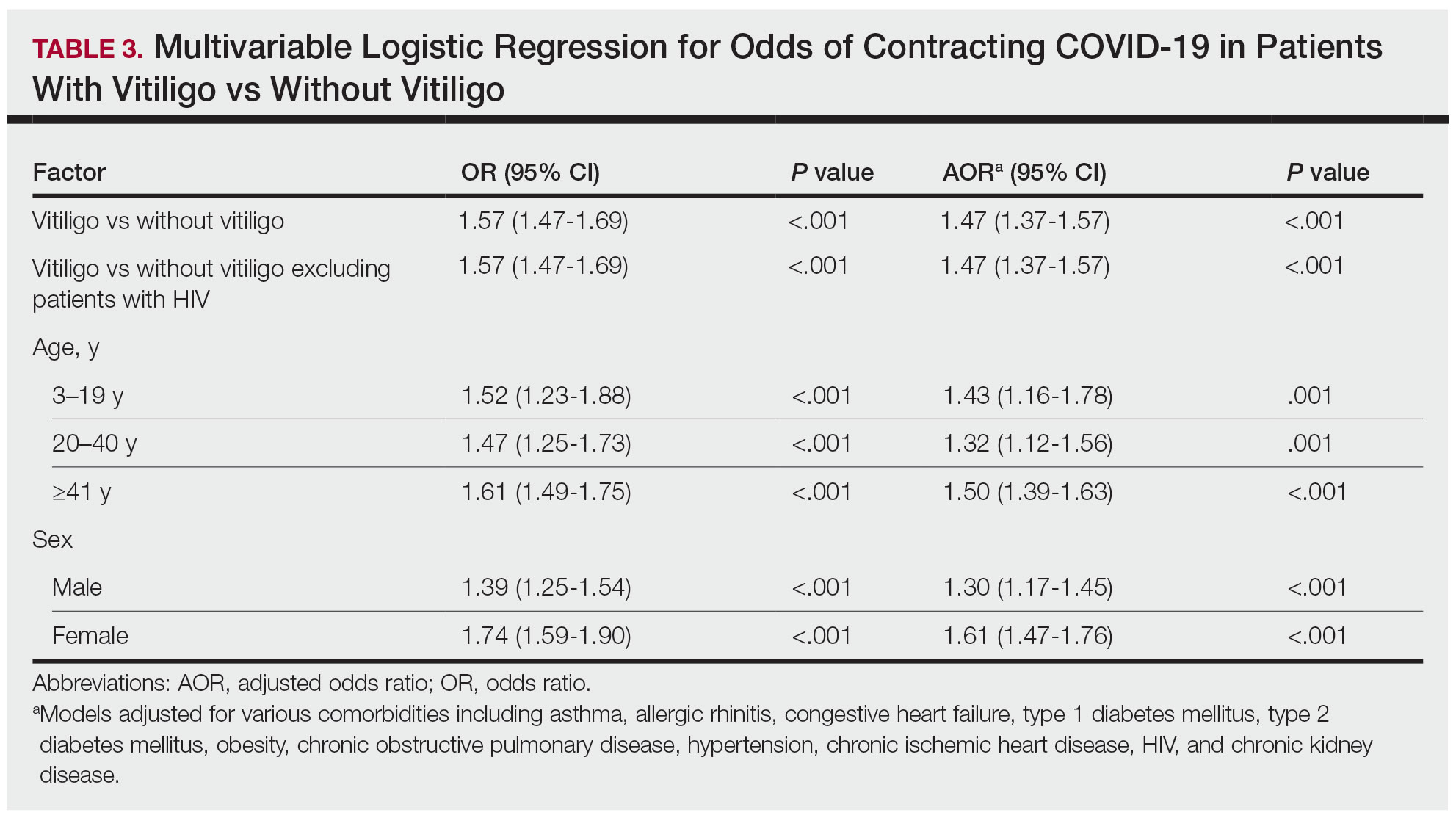

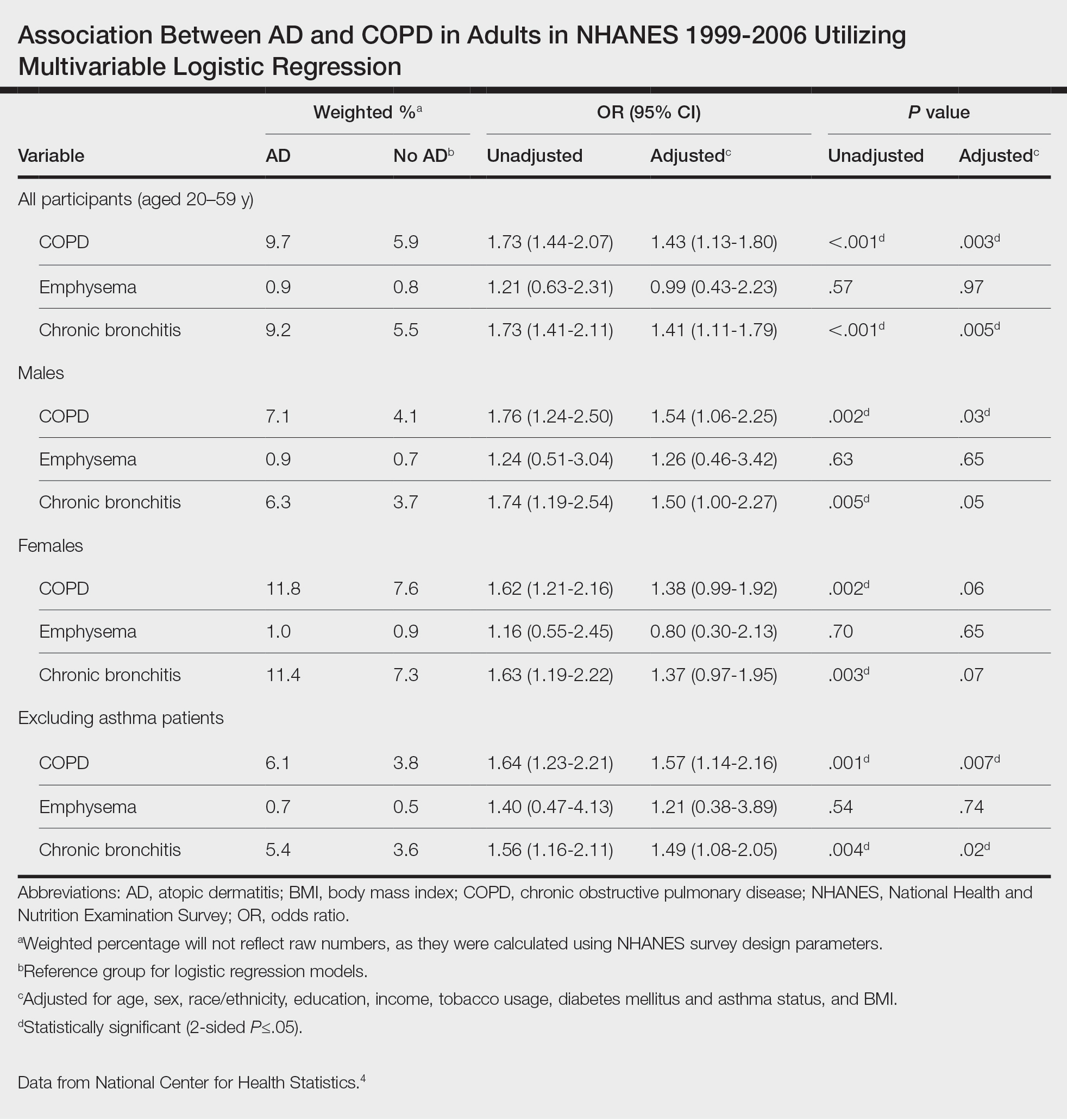

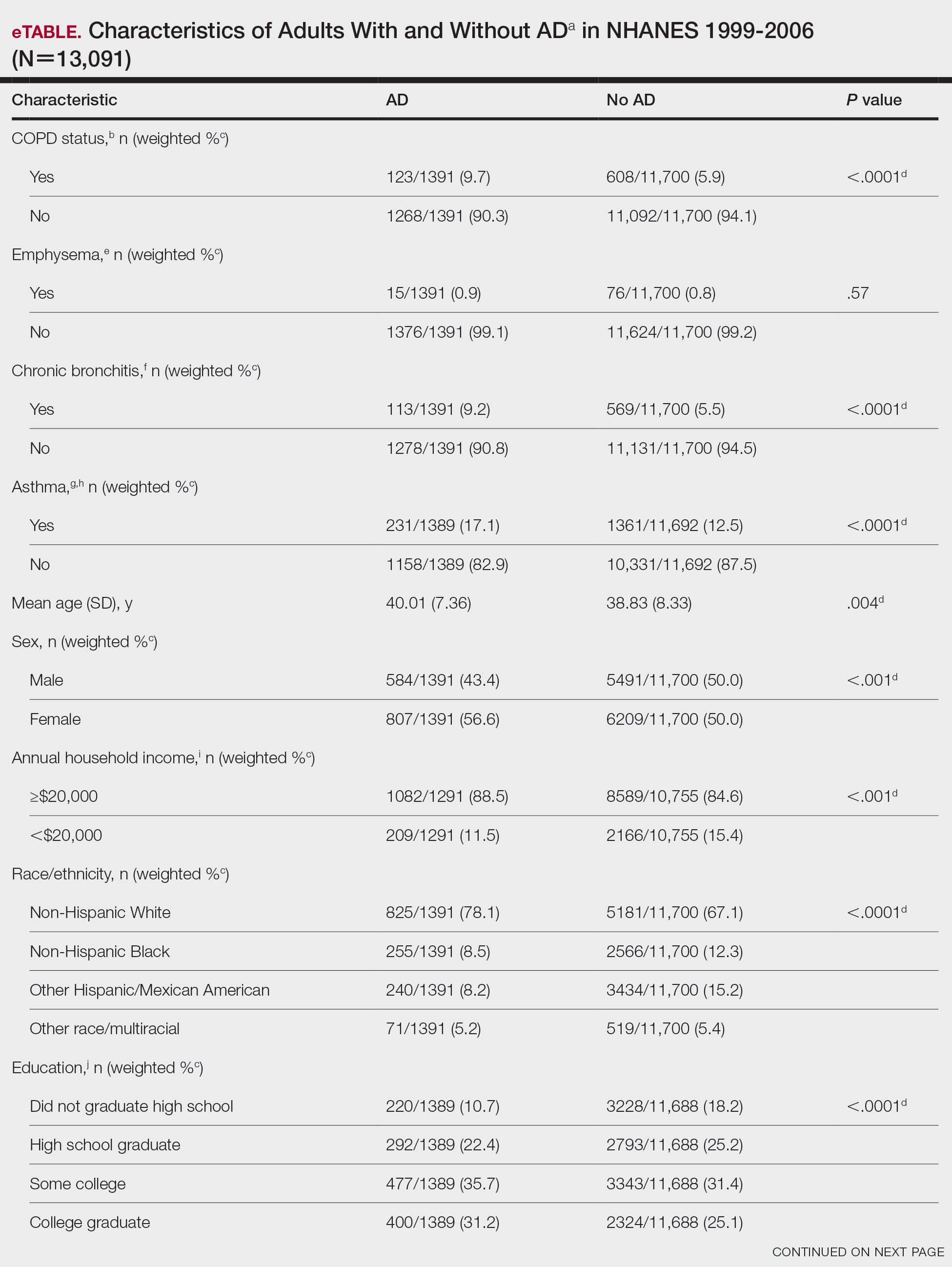

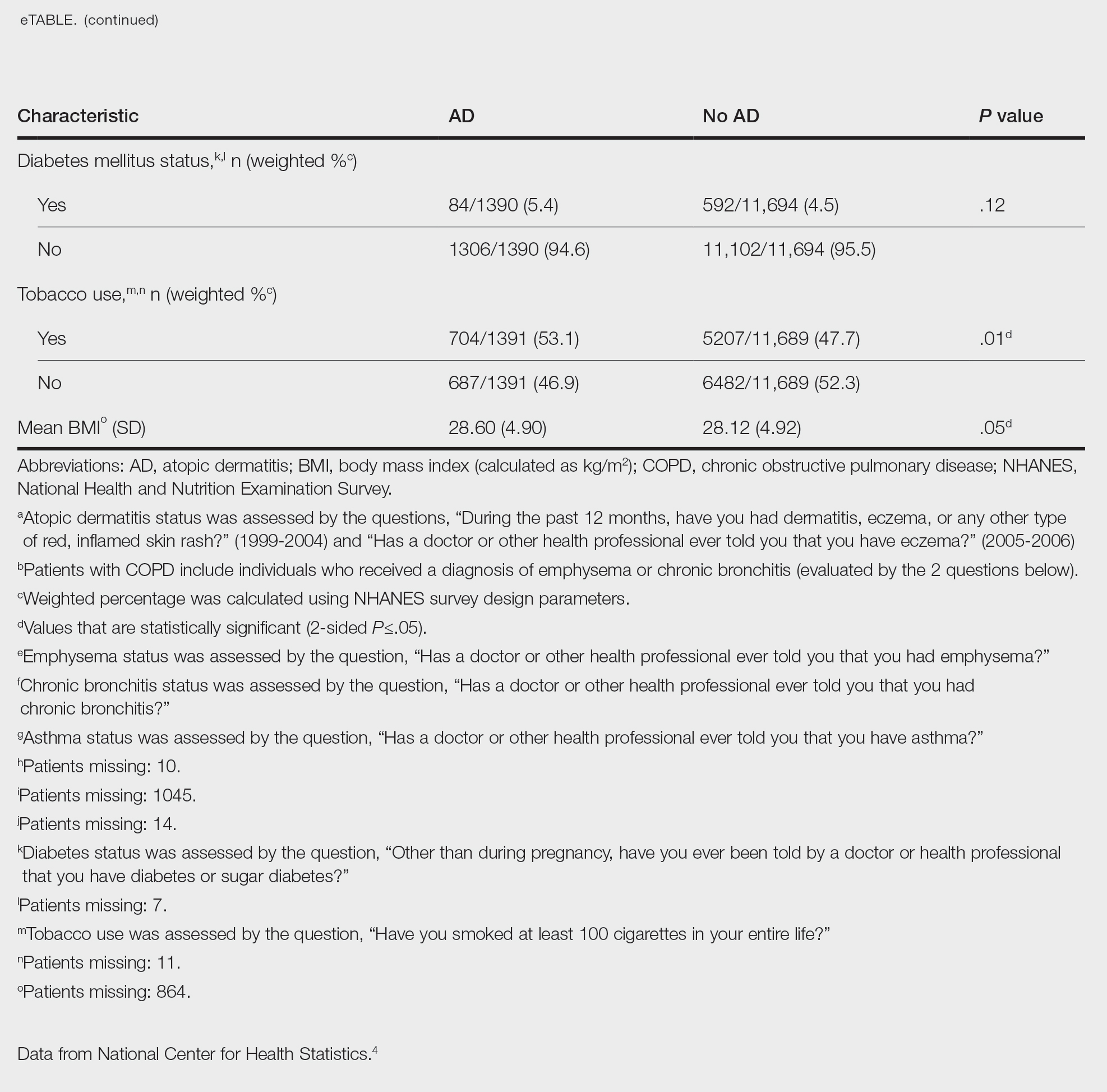

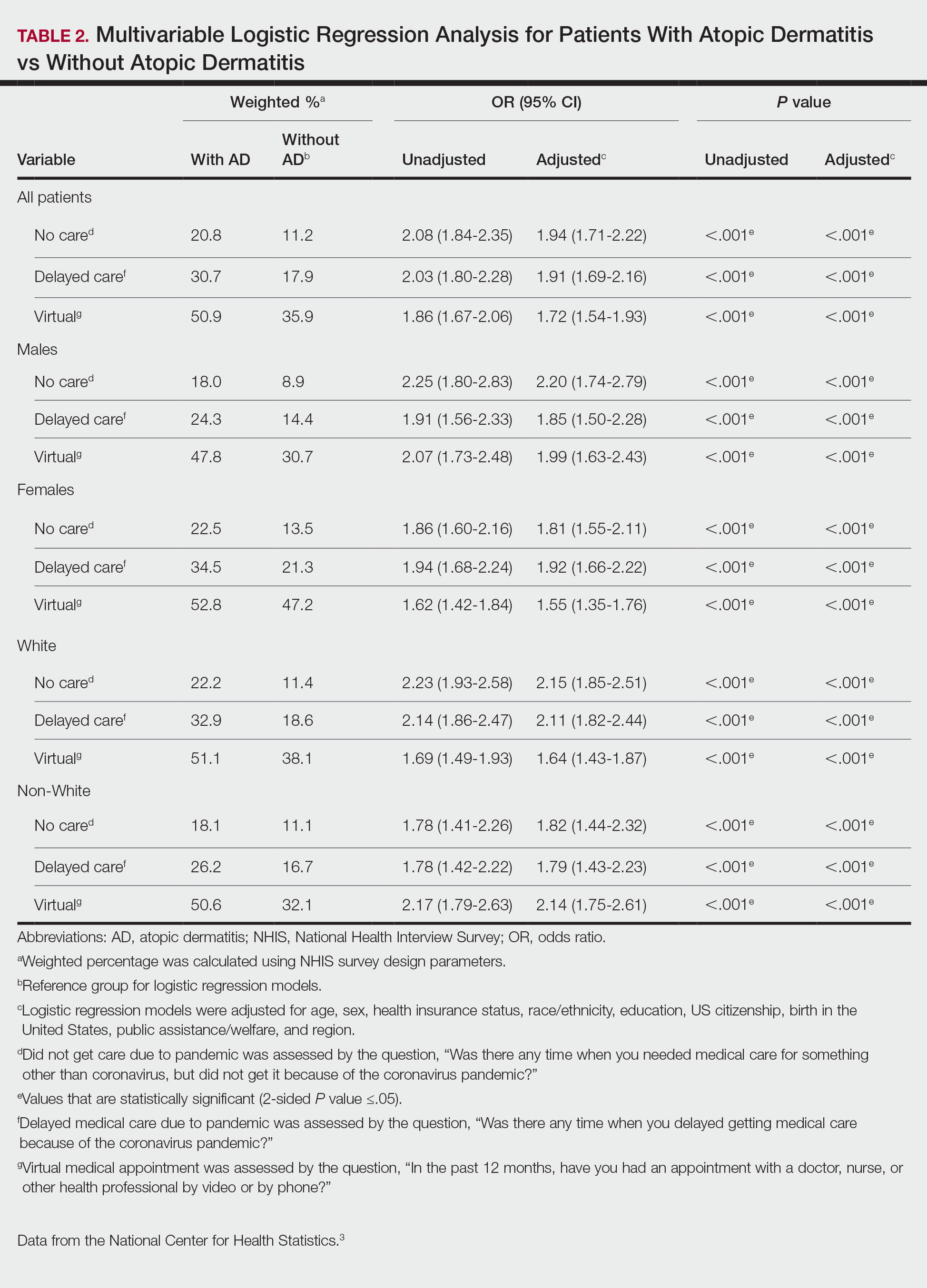

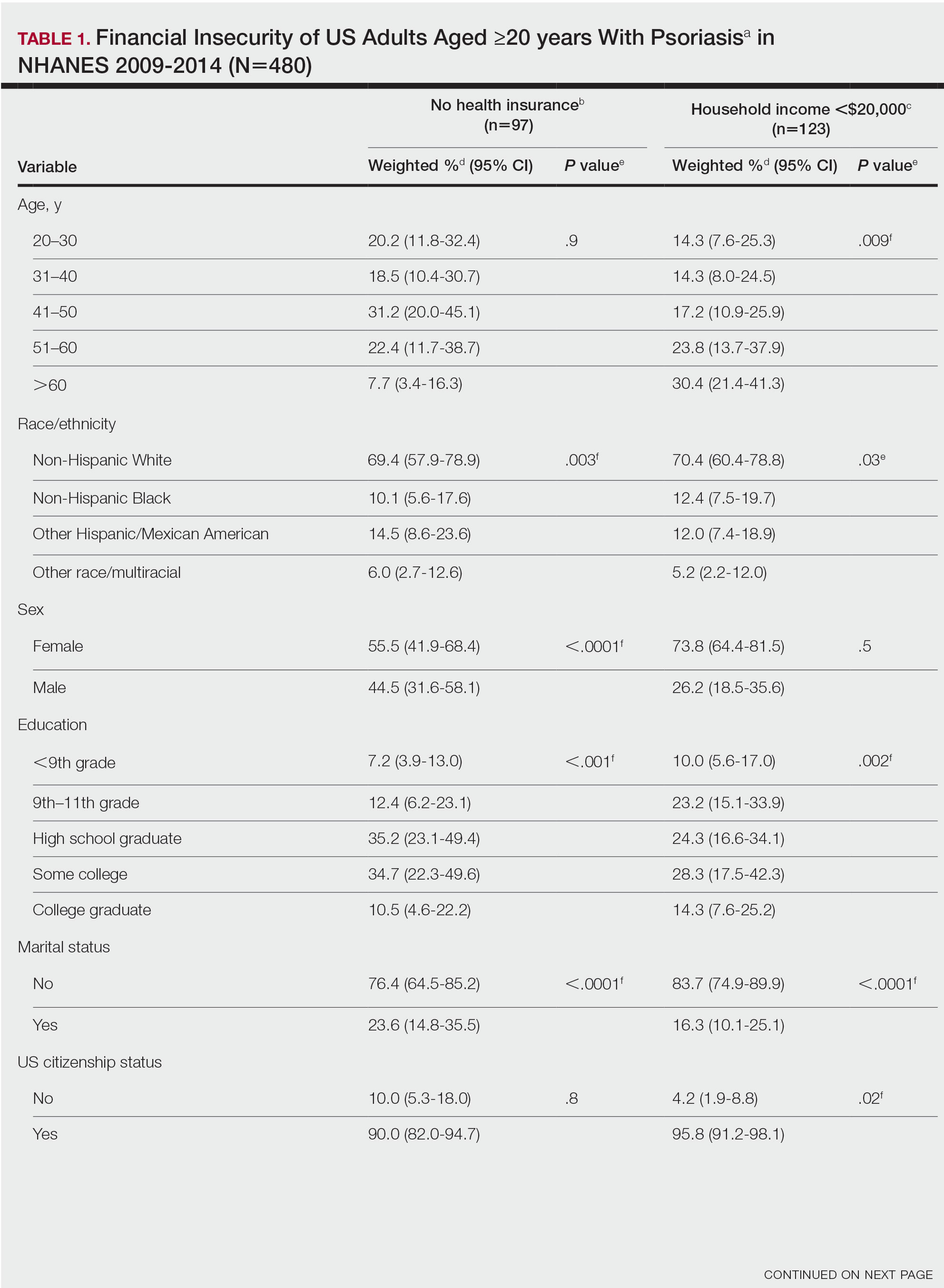

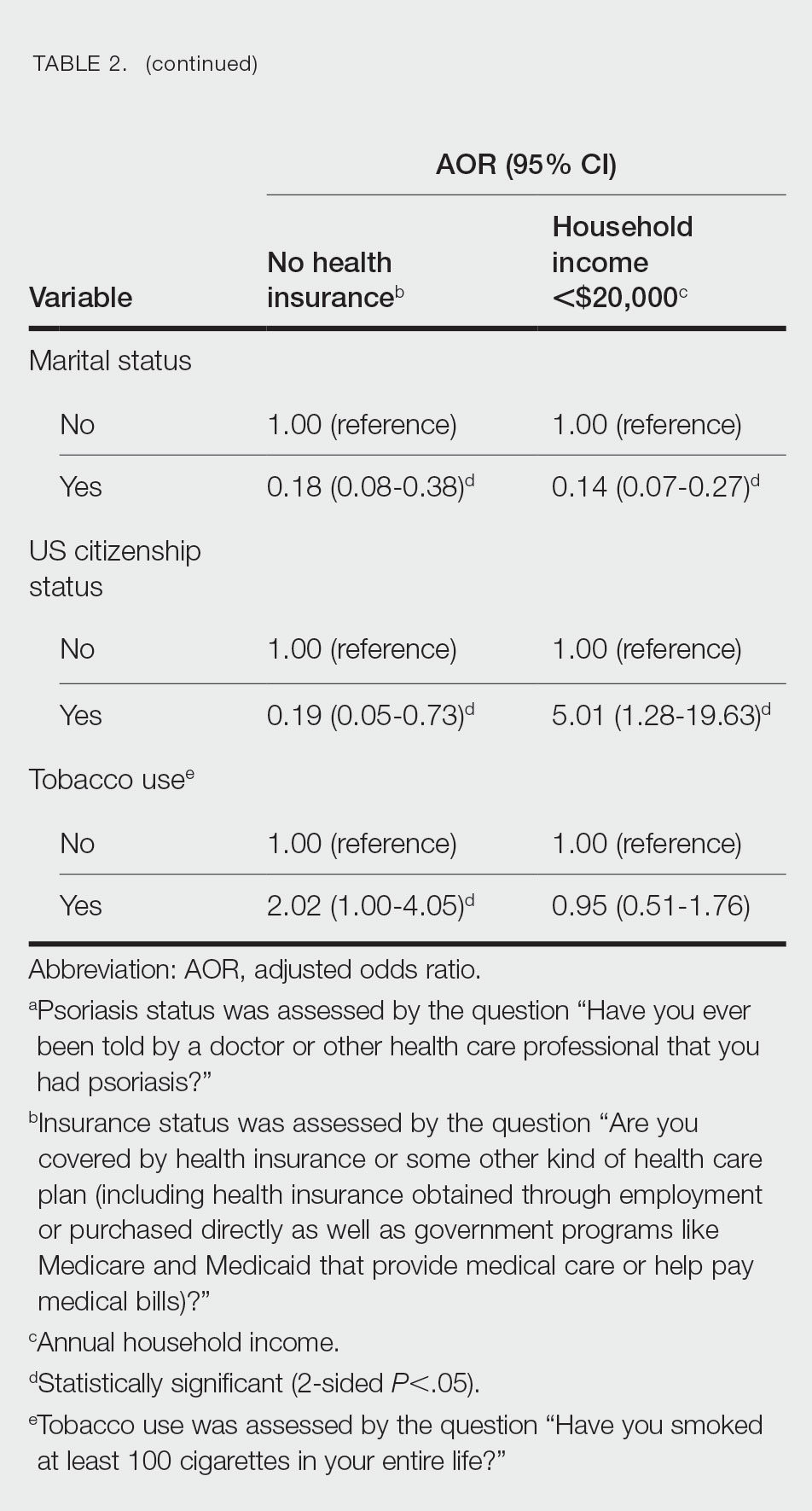

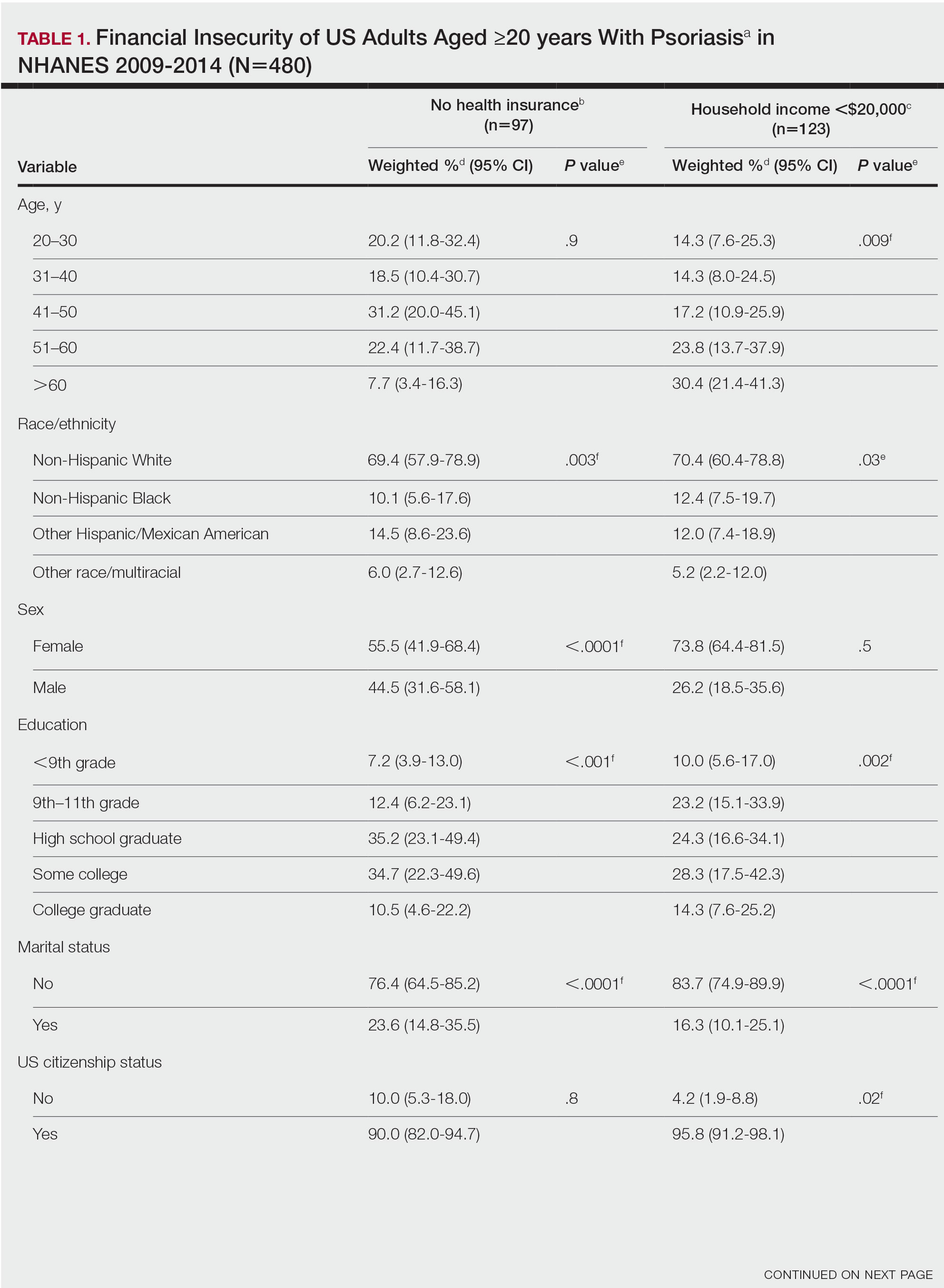

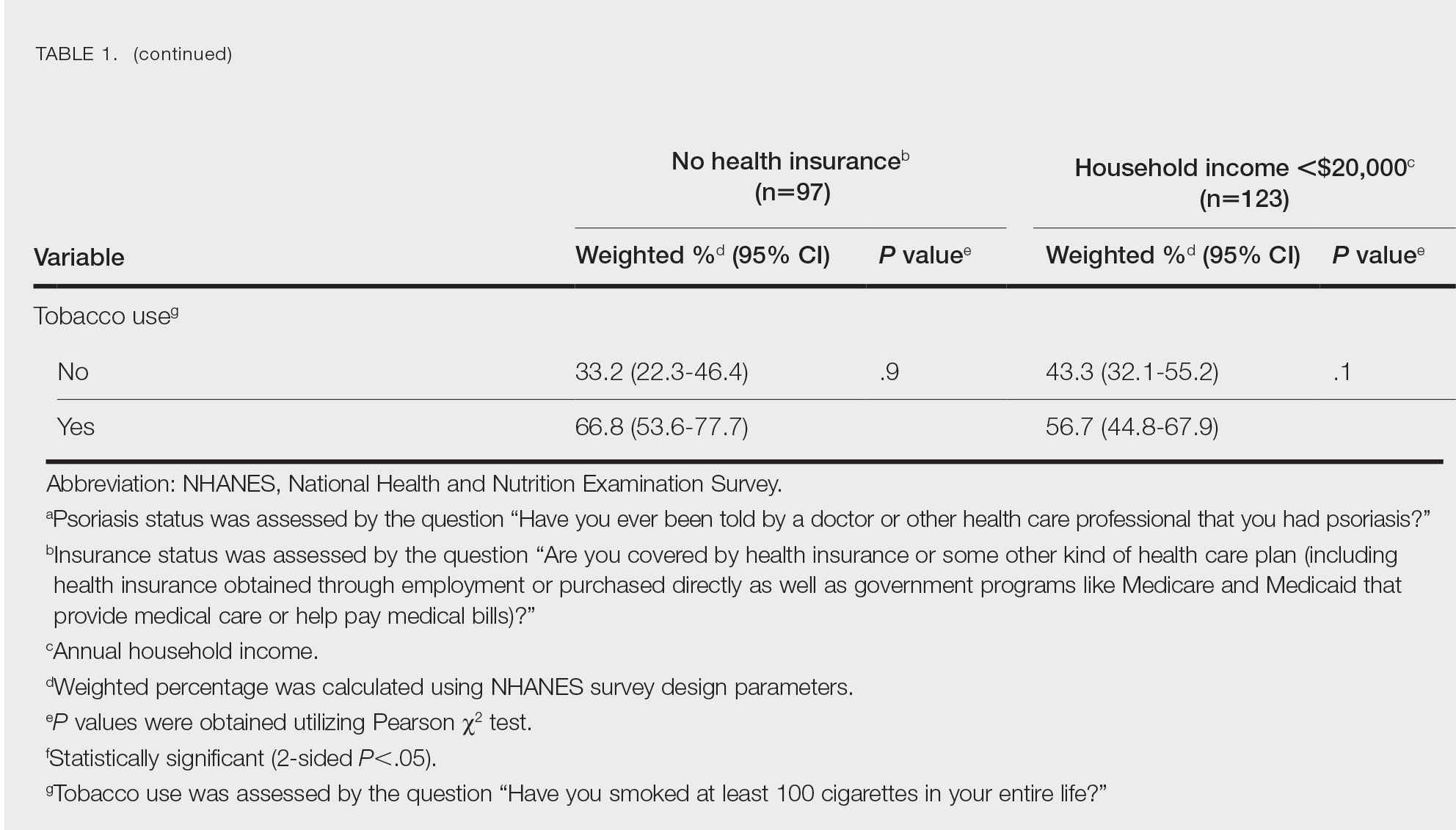

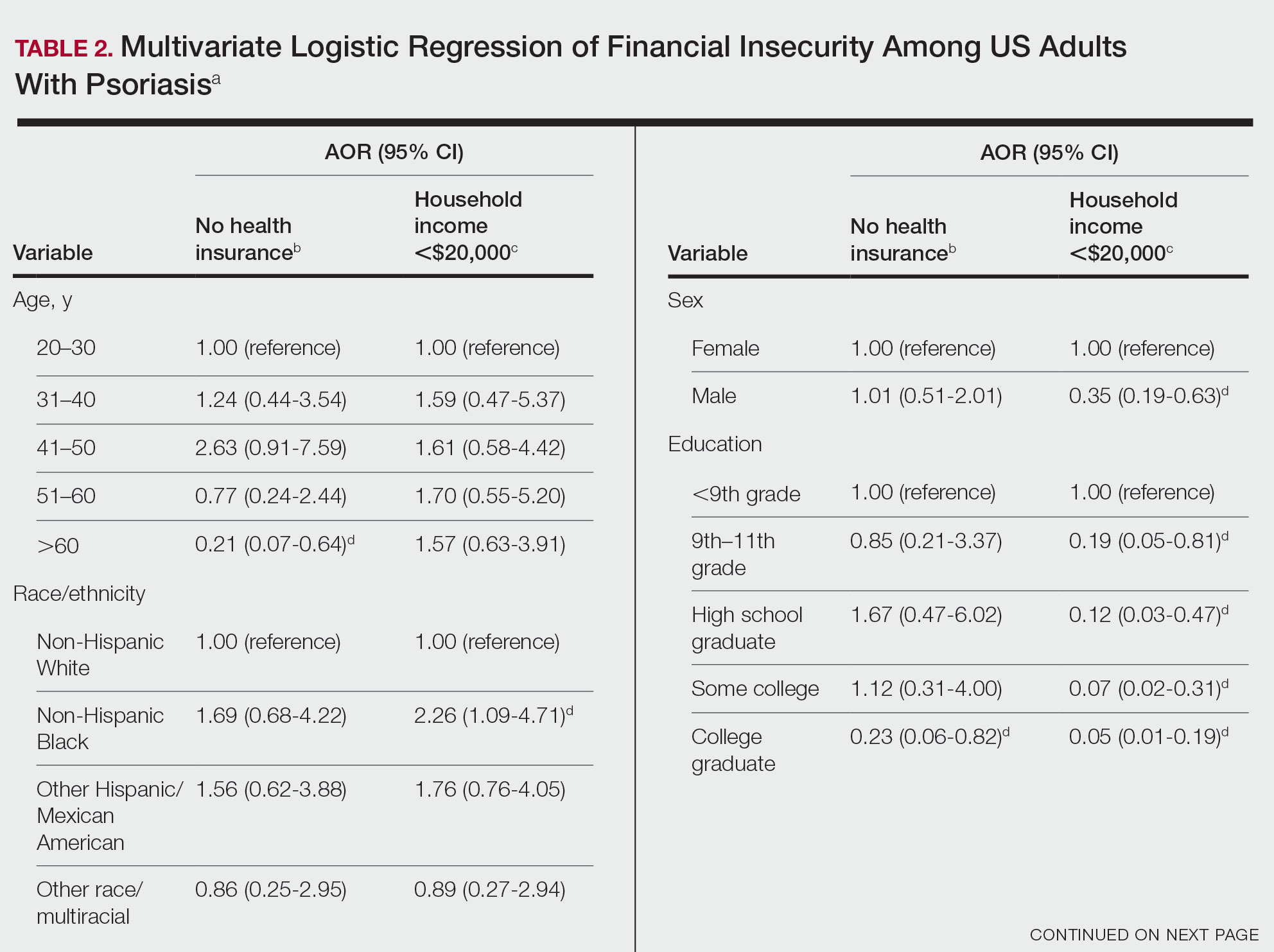

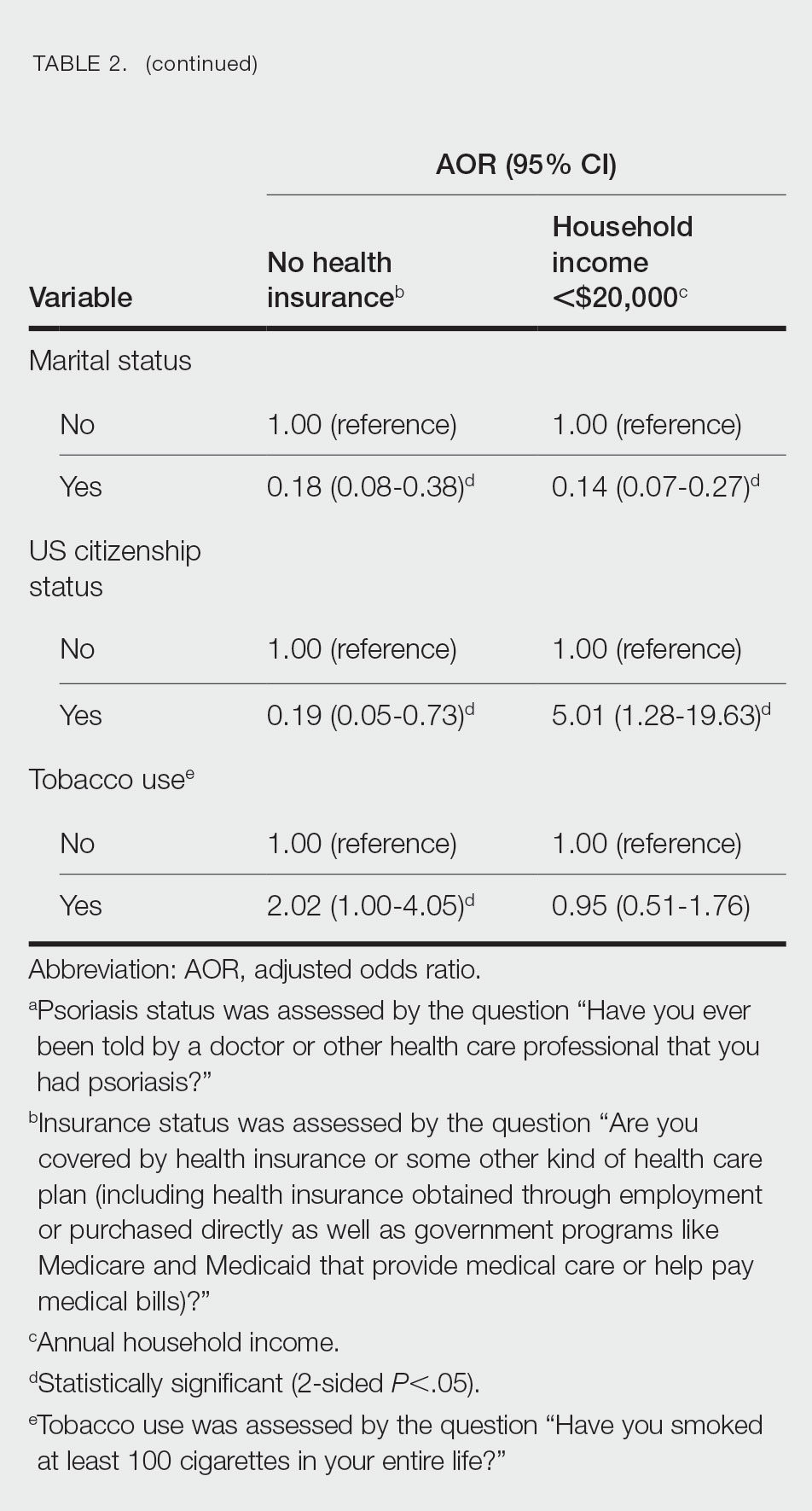

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

PRACTICE POINTS

- Mobility issues are more common in patients who have psoriasis than in those who do not.

- It is important to assess patients with psoriasis for mobility issues regardless of age or comorbid conditions such as arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

- Dermatologists can help patients with psoriasis and impaired mobility overcome potential barriers to care by incorporating telehealth services into their practices and informing patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions.

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

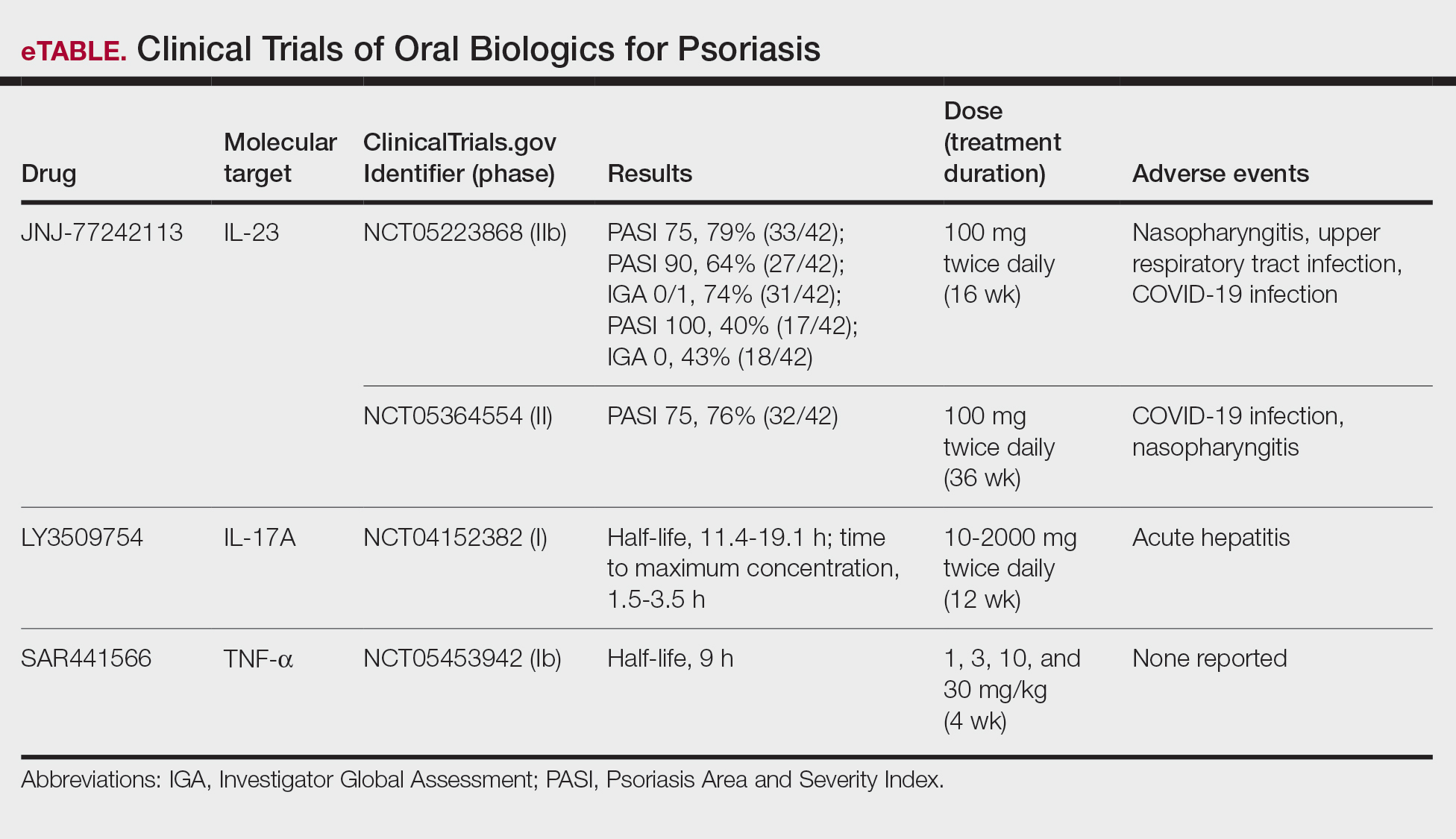

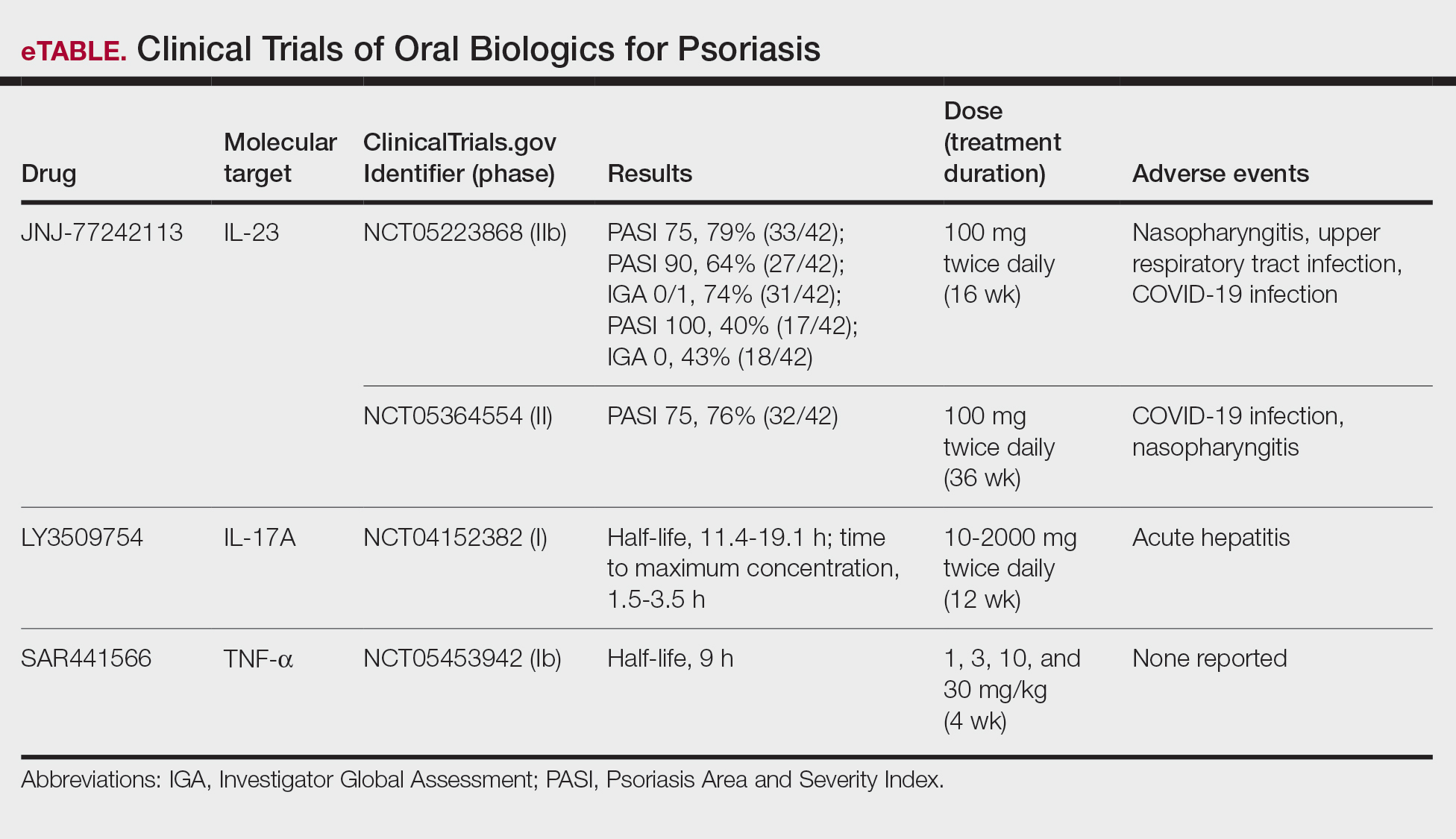

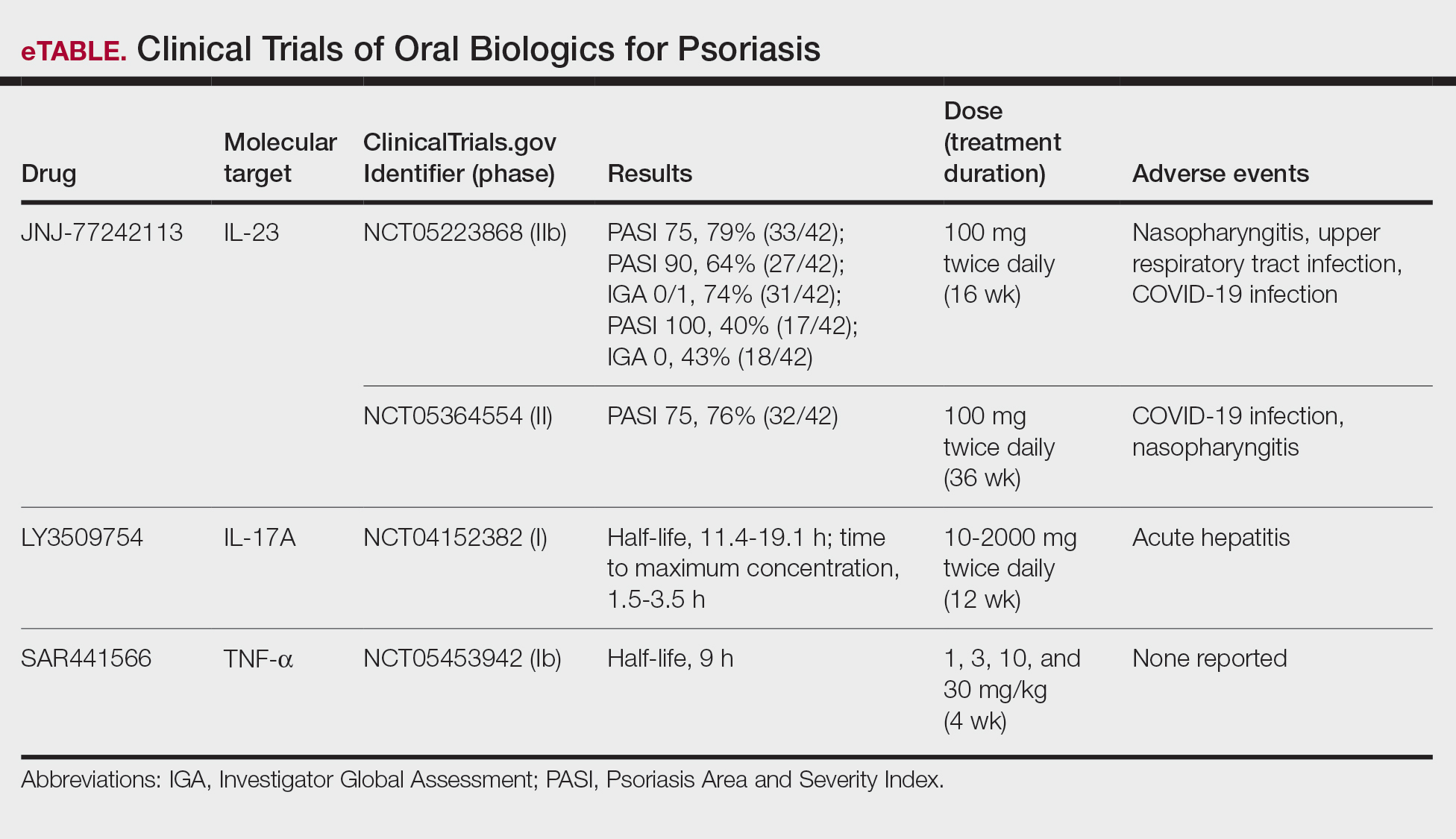

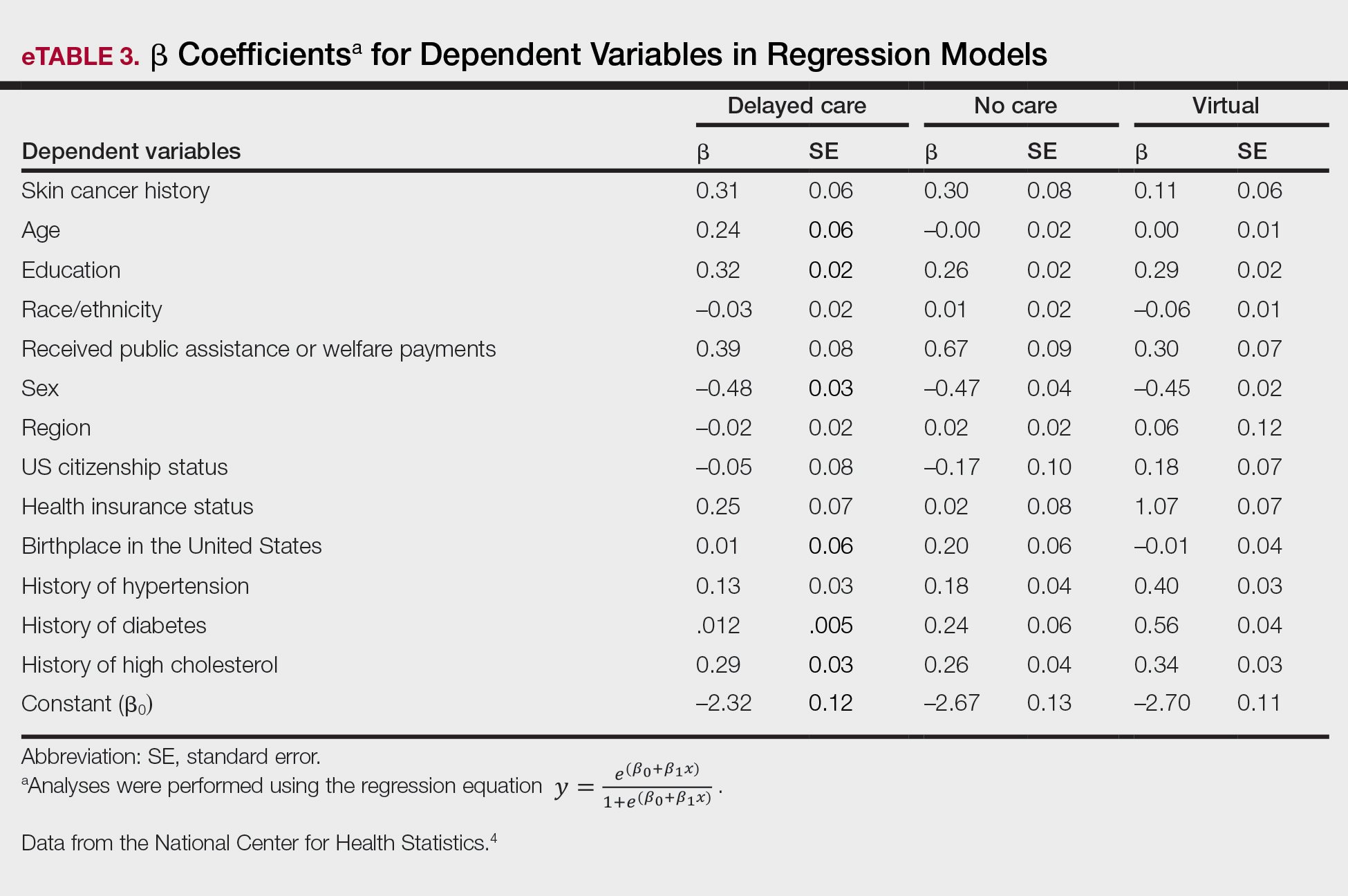

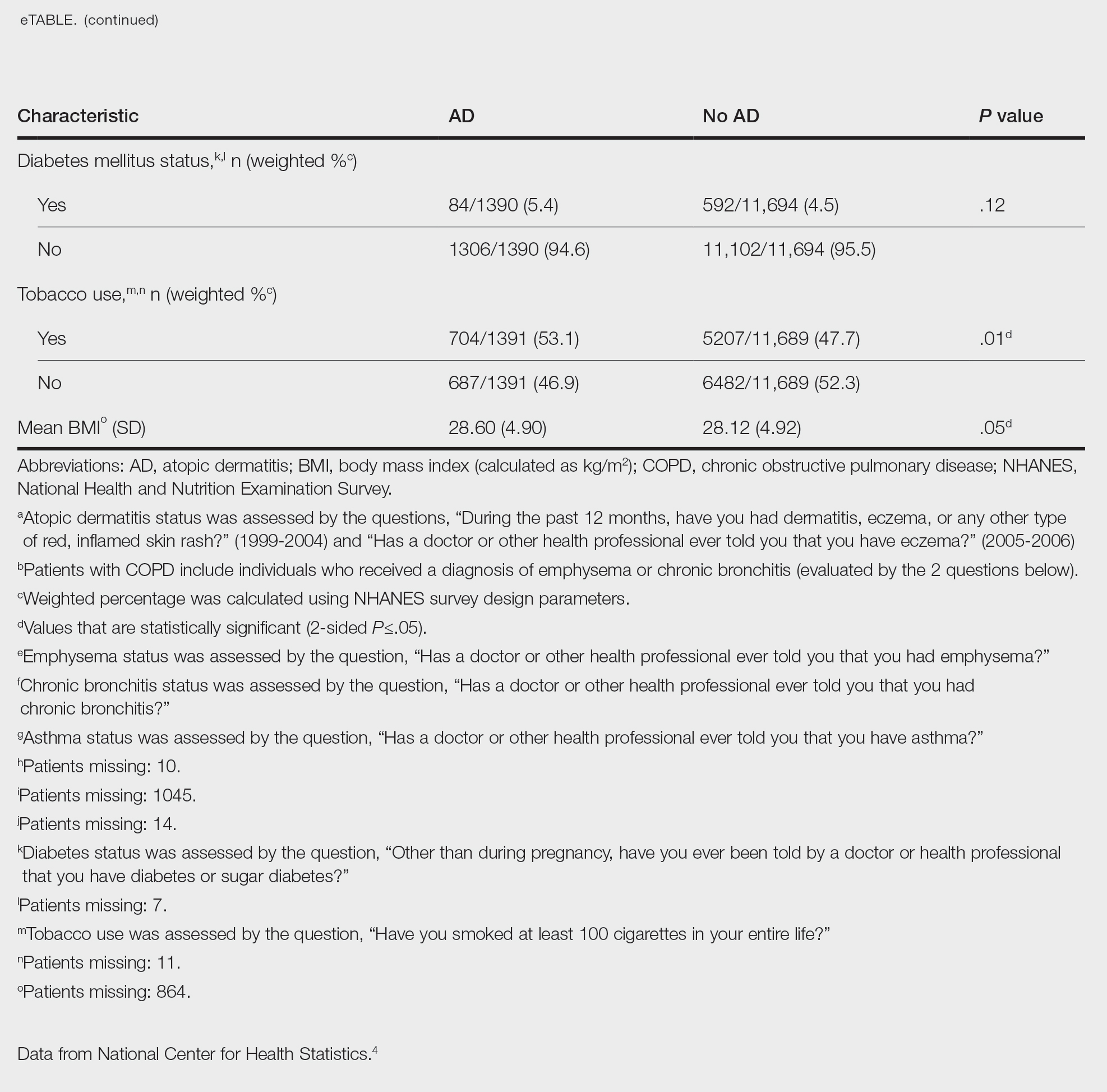

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

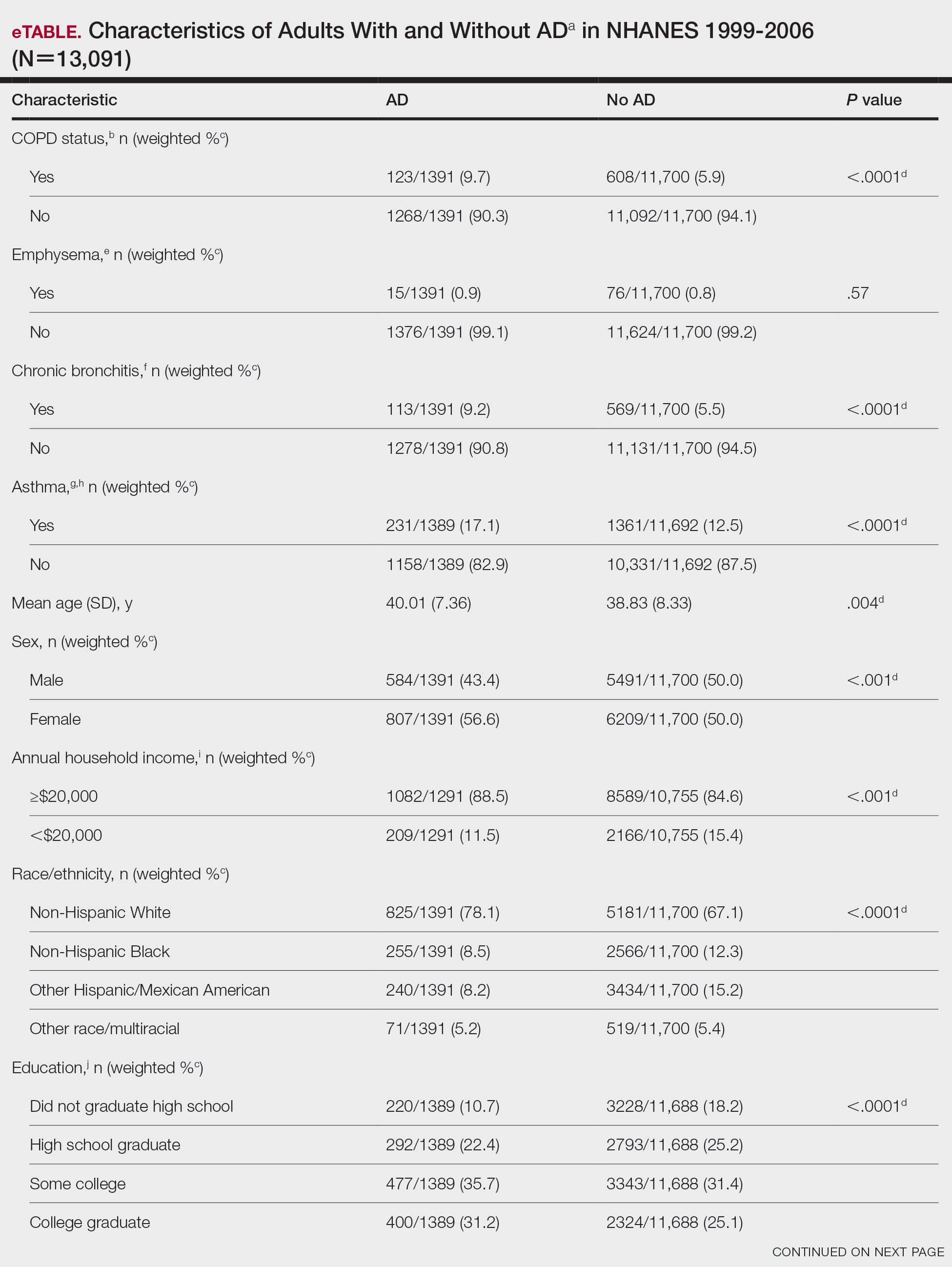

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

PRACTICE POINTS

- The biologics that currently are approved for psoriasis are expensive and must be administered via injection due to their large molecule size.

- Emerging small-molecule oral therapies for psoriasis are effective and affordable and may represent the future for psoriasis patients.

Association Between Psoriasis and Sunburn Prevalence in US Adults

Association Between Psoriasis and Sunburn Prevalence in US Adults

To the Editor:

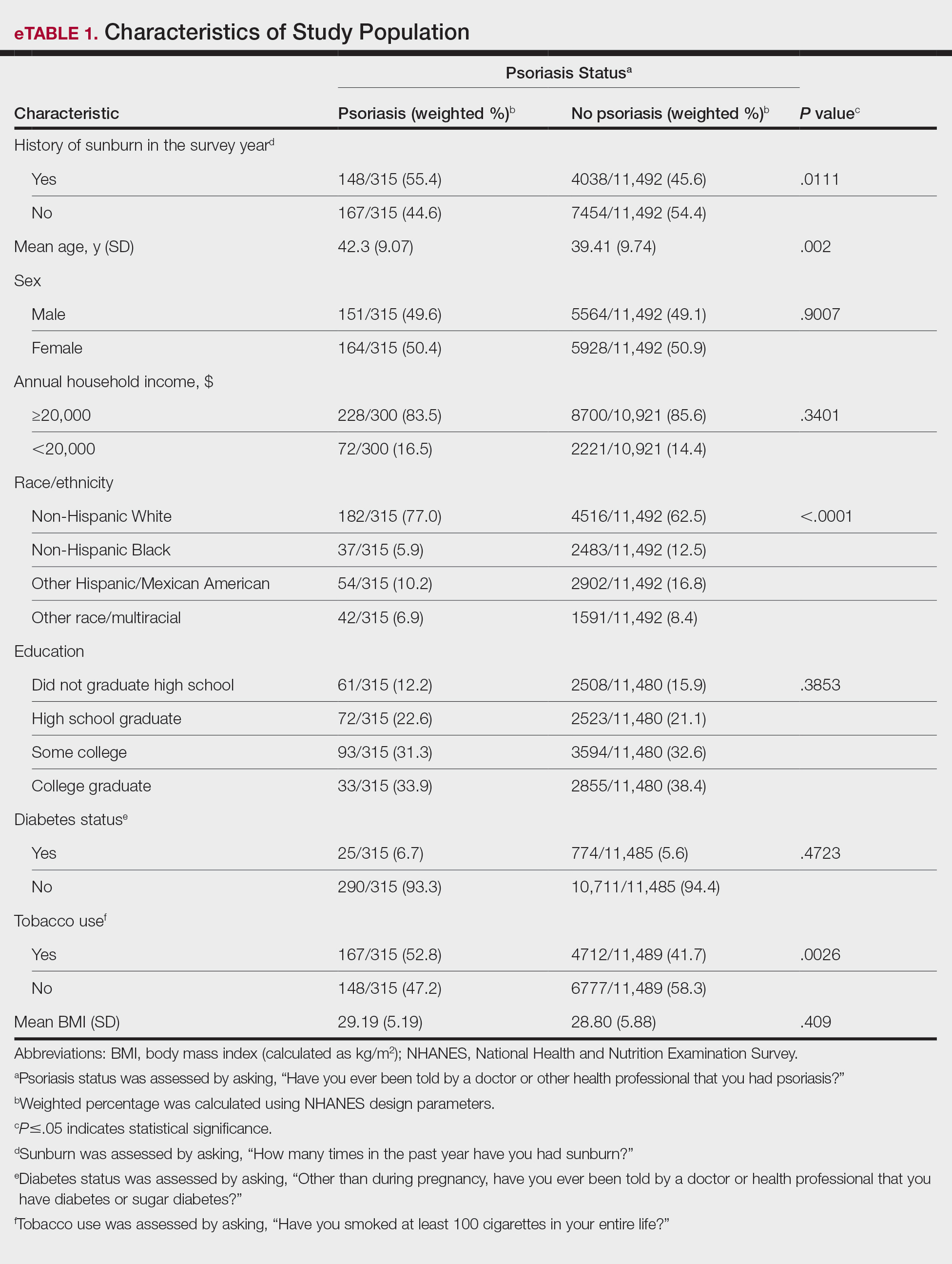

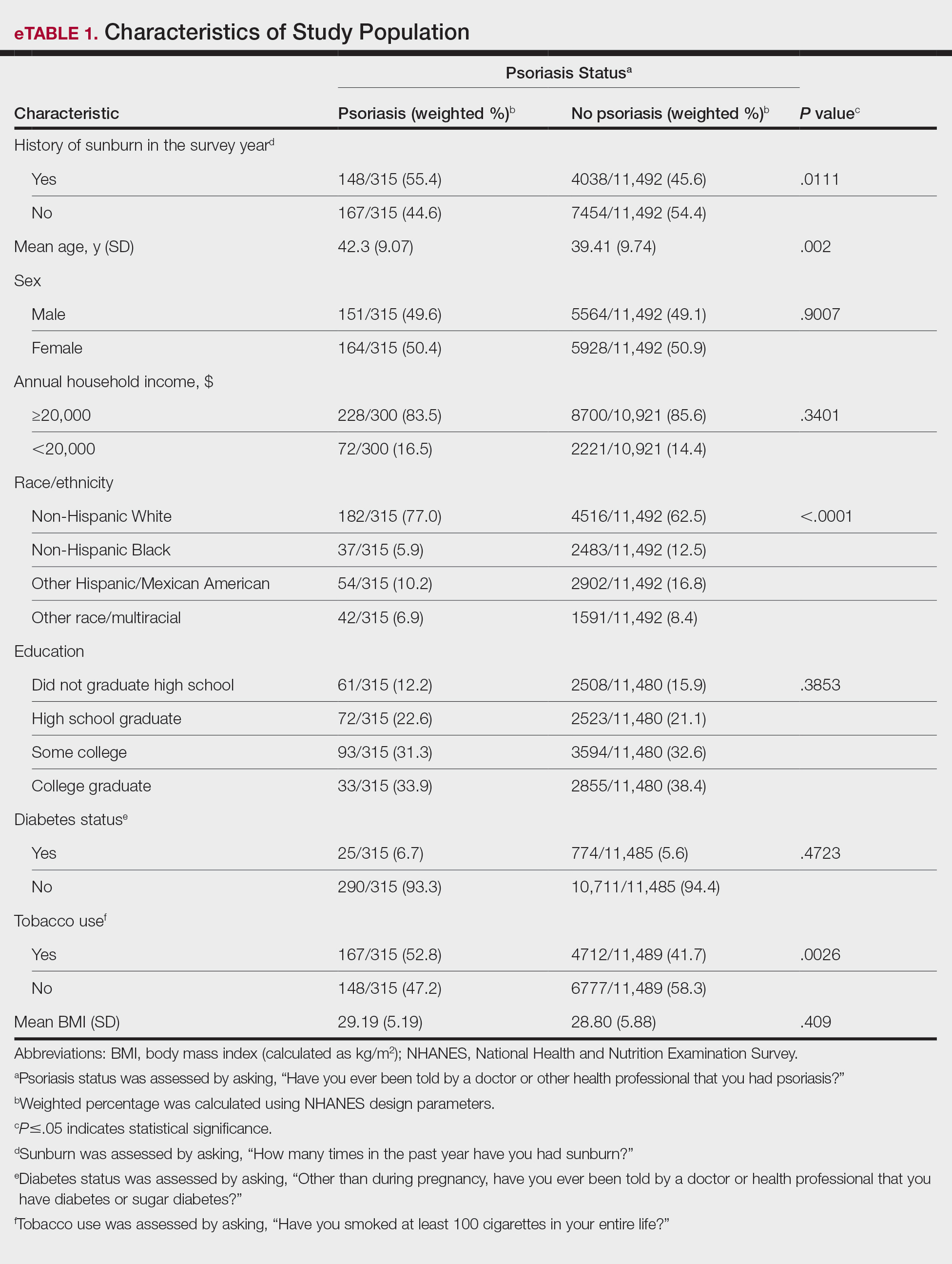

UV light plays an essential role in various environmental and biological processes.1 Excessive exposure to UV radiation can lead to sunburn, which is marked by skin erythema and pain.2 A study of more than 31,000 individuals found that 34.2% of adults aged 18 years and older reported at least 1 sunburn during the survey year.3 A lack of research regarding the incidence of sunburns in patients with psoriasis is particularly important considering the heightened incidence of skin cancer observed in this population.4 Thus, the aim of our study was to analyze the prevalence of sunburns among US adults with psoriasis utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database.5

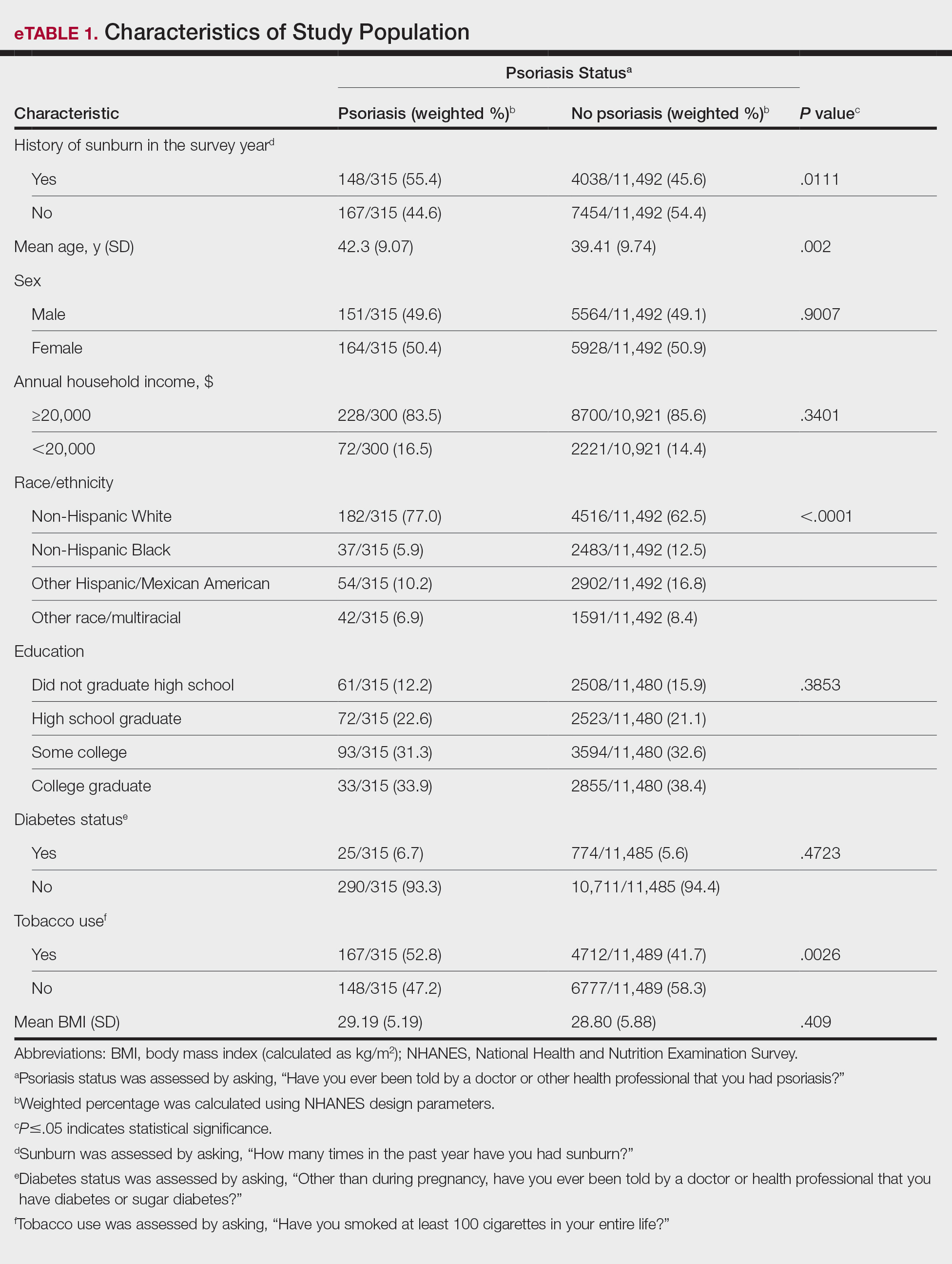

Our analysis initially included 11,842 participants ranging in age from 20 to 59 years; 35 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and sunburn prevalence and thus were excluded. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18 (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and sunburns. Our models controlled for patient age, sex, income, race, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, and body mass index. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The study period from January 2009 to December 2014 was chosen based on the availability of the most recent and comprehensive psoriasis data within the NHANES database.

In the NHANES data we evaluated, psoriasis status was assessed by asking, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” History of sunburns in the survey year was assessed by the question, “How many times in the past year have you had sunburn?” Patients who reported 1 or more sunburns were included in the sunburn cohort, while those who did not report a sunburn were included in the no sunburn cohort.

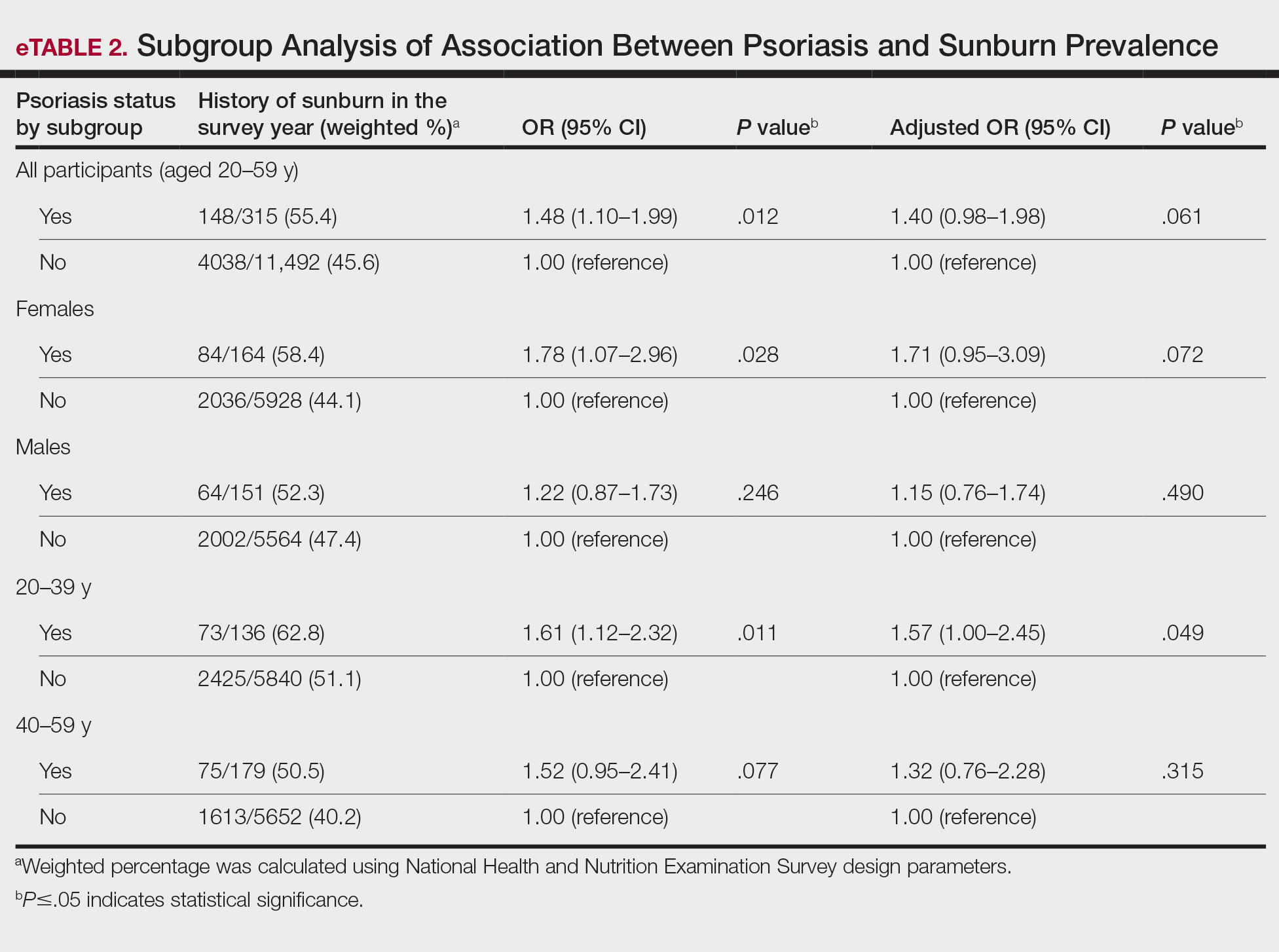

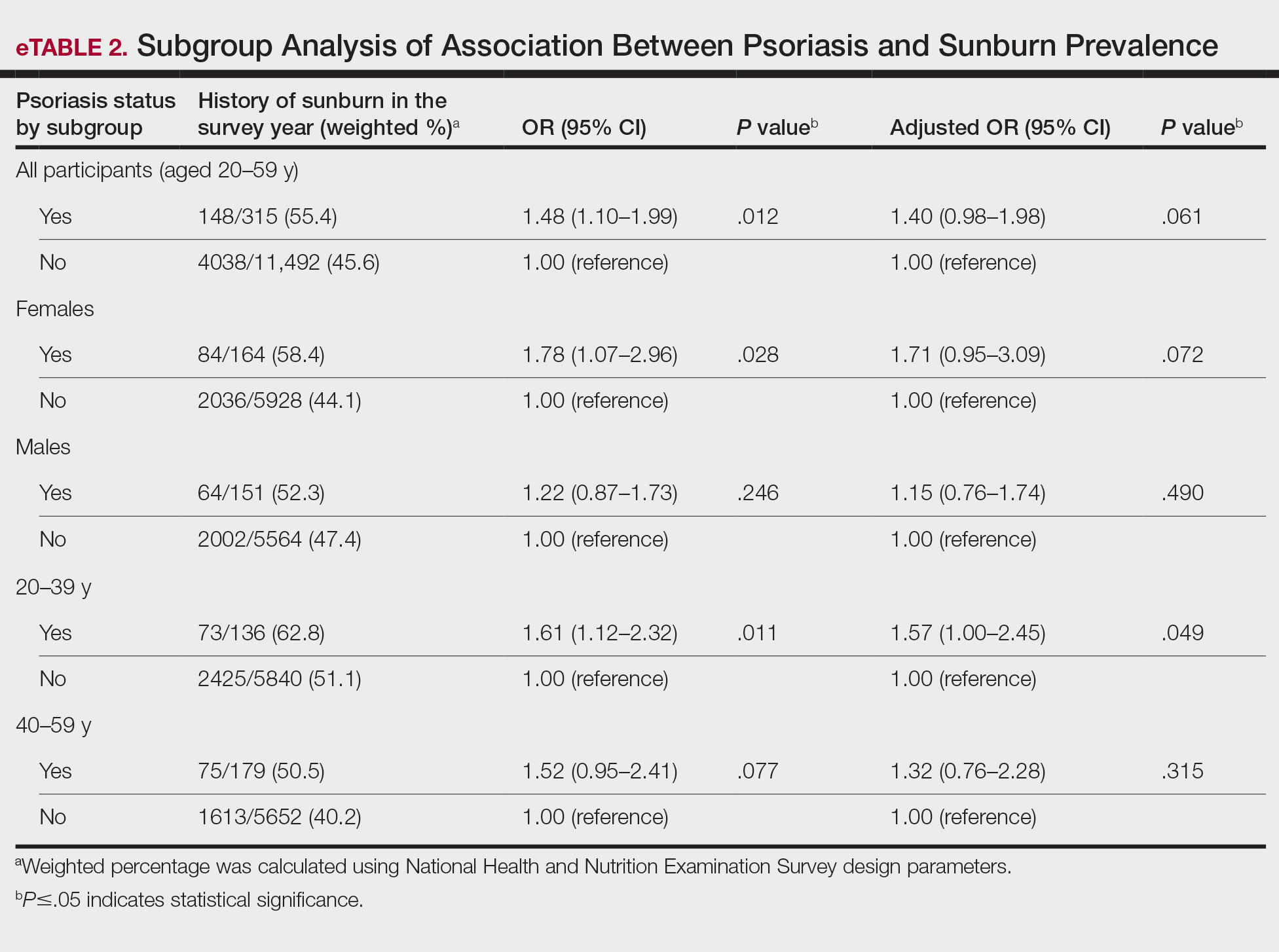

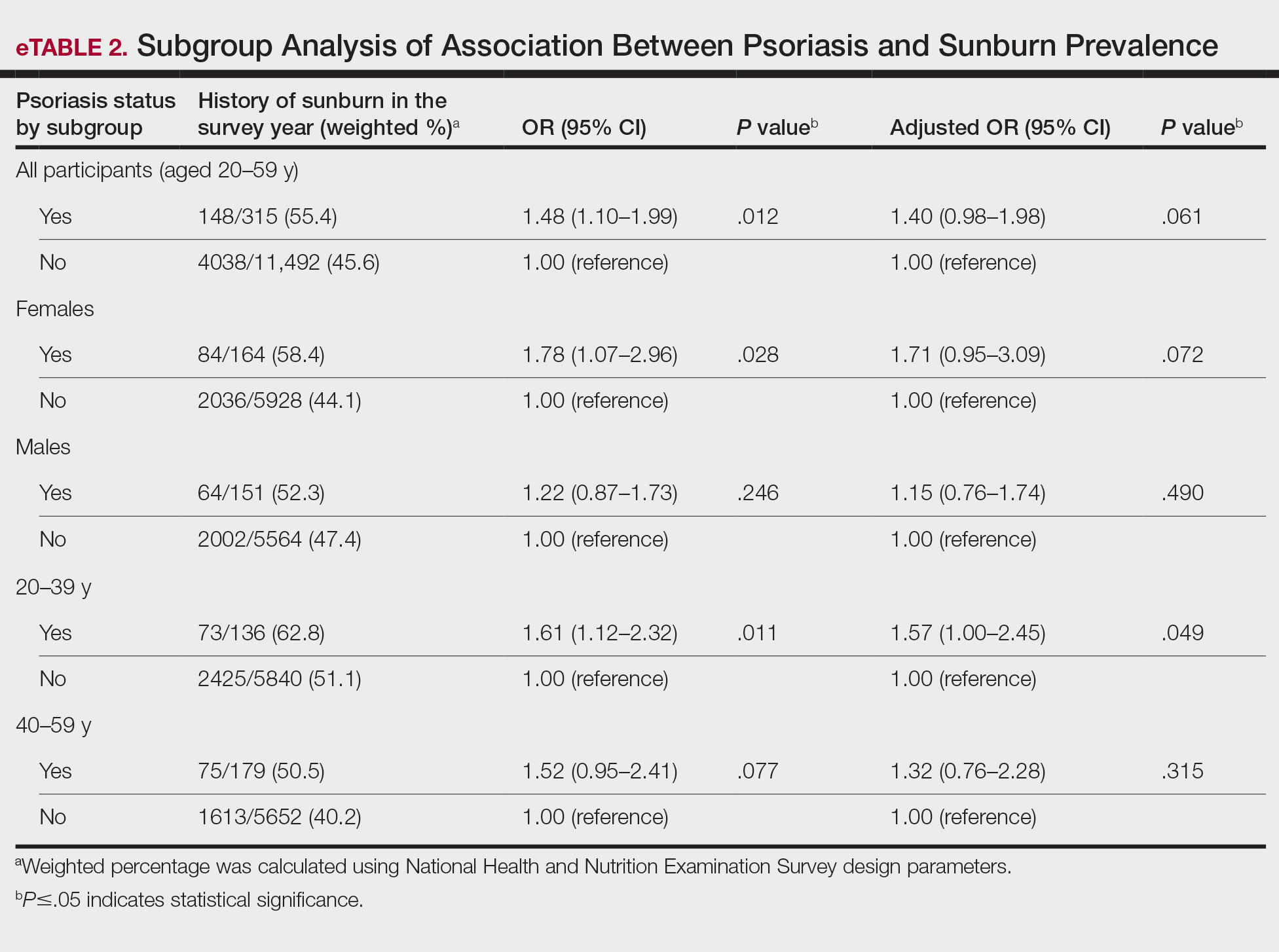

In our analysis, the prevalence of at least 1 sunburn in the survey year in patients with psoriasis was 55.4% (weighted), compared to 45.6% (weighted) among those without psoriasis (eTable 1). Although there was no statistically significant relationship between psoriasis and history of sunburn in patients aged 20 to 59 years, a subgroup analysis revealed a significant association between psoriasis and sunburn in adults aged 20 to 39 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted OR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.00-2.45]; P=.049)(eTable 2). Further analysis of subgroups showed no statistically significant results with adjustment of the logistic regression model. Characterizing response rates is important for assessing the validity of survey studies. The NHANES response rate from 2009 to 2014 was 72.9%, enhancing the reliability of our findings.

Our study revealed an increased prevalence of sunburn in US adults with psoriasis. A trend of increased sunburn prevalence among younger adults regardless of psoriasis status is corroborated by the literature. Surveys conducted in the United States in 2005, 2010, and 2015 showed that 43% to 50% of adults aged 18 to 39 years and 28% to 42% of those aged 40 to 59 years reported experiencing at least 1 sunburn within the respective survey year.6 Furthermore, in our study, patients with psoriasis reported higher rates of sunburn than their counterparts without psoriasis, both in those aged 20 to 39 years (psoriasis, 62.8% [73/136]; no psoriasis, 51.1% [2425/5840]) and those aged 40 to 59 years (psoriasis, 50.5% [n=75/179]; no psoriasis, 40.2% [1613/5652]), though it was only statistically significant in the 20-to-39 age group. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in sun-protective behaviors in younger vs older adults. A study from the NHANES database found that, among individuals aged 20 to 39 years, 75.9% [4225/5493] reported staying in the shade, 50.0% [2346/5493] reported using sunscreen, and 31.2% [1874/5493] reported wearing sun-protective clothing.7 Interestingly, the likelihood of engaging in all 3 behaviors was 28% lower in the 20-to-39 age group vs the 40-to-59 age group (adjusted OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62-0.83).7

While our analysis adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and tobacco use to mitigate potential confounding, we acknowledge the statistically significant differences observed in these variables between study groups as presented in eTable 2. These differences may reflect inherent disparities in the study population. We employed multivariable regression analysis to control for these covariates in our primary analyses. Of note, there was a statistically significant difference associated with race/ethnicity when comparing non-Hispanic White individuals with psoriasis (77.0% [n=182/315]) and those without psoriasis (62.5% [n=4516/11,492])(P<.0001)(eTable 1). The higher proportion of non-Hispanic White patients in the psoriasis group may reflect an increased susceptibility to sunburn given their typically lighter skin pigmentation; however, our analysis controlled for race/ethnicity (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of racial/ethnic differences. There also were statistically significant differences in tobacco use (P=.0026) and age (P=.002) in our unadjusted findings (eTable 1). Again, our analysis controlled for these factors (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of tobacco use and age differences. This approach enhanced the reliability of our findings.

The association between psoriasis and skin cancer has previously been evaluated using the NHANES database—one study found that patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer compared with those without psoriasis (3.0% vs 1.3%; relative risk, 2.29; P<.001).8 This difference remained significant after adjusting for confounding variables, as it was found that psoriasis was independently associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer (adjusted relative risk, 2.06; P=.004).8

The relationship between psoriasis and sunburn may be due to behavioral choices, such as the use of phototherapy for managing psoriasis due to its recognized advantages.9 Patients may seek out both artificial and natural light sources more frequently, potentially increasing the risk for sunburn.10 Psoriasis-related sunburn susceptibility may stem from biological factors, including vitamin D insufficiency, as vitamin D is crucial for keratinocyte differentiation, immune function, and UV protection and repair.11 One study examined the effects of high-dose vitamin D3 on sunburn-induced inflammation.12 Patients who received high-dose vitamin D3 exhibited reduced skin inflammation, enhanced skin barrier repair, and increased anti-inflammatory response compared with those who did not receive the supplement. This improvement was associated with upregulation of arginase 1, an anti-inflammatory enzyme, leading to decreased levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α and inducible nitric oxide synthase, thereby promoting tissue repair and reducing prolonged inflammation.12 These findings suggest that vitamin D insufficiency coupled with dysregulated immune responses may contribute to the heightened susceptibility of individuals with psoriasis to sunburn.

The established correlation between sunburn and skin cancer4,8 coupled with our findings of increased prevalence of sunburn in individuals with psoriasis underscores the need for additional research to clarify the underlying biological and behavioral factors that may contribute to a higher prevalence of sunburn in these patients, along with the implications for skin cancer development. Limitations of our study included potential recall bias, as individuals self-reported their clinical conditions and the inability to incorporate psoriasis severity into our analysis, as this was not consistently captured in the NHANES questionnaire during the study period.

- Blaustein AR, Searle C. Ultraviolet radiation. In: Levin SA, ed. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2013:296-303.

- D’Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, et al. UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:12222-12248

- Holman DM, Ding H, Guy GP Jr, et al. Prevalence of sun protection use and sunburn and association of demographic and behavioral characteristics with sunburn among US adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:561-568.

- Balda A, Wani I, Roohi TF, et al. Psoriasis and skin cancer—is there a link? Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;121:110464.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Holman DM, Ding H, Berkowitz Z, et al. Sunburn prevalence among US adults, National Health Interview Survey 2005, 2010, and 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:817-820.

- Challapalli SD, Shetty KR, Bui Q, et al. Sun protective behaviors among adolescents and young adults in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2023;115:353-361.

- Herbosa CM, Hodges W, Mann C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: study of a nationally representative sample of the US population with comparison to a single]institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E529-E531.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Åkerla P, Pukkala E, Helminen M, et al. Skin cancer risk of narrow-band UV-B (TL-01) phototherapy: a multi-center registry study with 4,815 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv39927.

- Filoni A, Vestita M, Congedo M, et al. Association between psoriasis and vitamin D: duration of disease correlates with decreased vitamin D serum levels: an observational case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E11185.

- Scott JF, Das LM, Ahsanuddin S, et al. Oral vitamin D rapidly attenuates inflammation from sunburn: an interventional study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2078-2086.

To the Editor:

UV light plays an essential role in various environmental and biological processes.1 Excessive exposure to UV radiation can lead to sunburn, which is marked by skin erythema and pain.2 A study of more than 31,000 individuals found that 34.2% of adults aged 18 years and older reported at least 1 sunburn during the survey year.3 A lack of research regarding the incidence of sunburns in patients with psoriasis is particularly important considering the heightened incidence of skin cancer observed in this population.4 Thus, the aim of our study was to analyze the prevalence of sunburns among US adults with psoriasis utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database.5

Our analysis initially included 11,842 participants ranging in age from 20 to 59 years; 35 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and sunburn prevalence and thus were excluded. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18 (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and sunburns. Our models controlled for patient age, sex, income, race, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, and body mass index. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The study period from January 2009 to December 2014 was chosen based on the availability of the most recent and comprehensive psoriasis data within the NHANES database.

In the NHANES data we evaluated, psoriasis status was assessed by asking, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” History of sunburns in the survey year was assessed by the question, “How many times in the past year have you had sunburn?” Patients who reported 1 or more sunburns were included in the sunburn cohort, while those who did not report a sunburn were included in the no sunburn cohort.

In our analysis, the prevalence of at least 1 sunburn in the survey year in patients with psoriasis was 55.4% (weighted), compared to 45.6% (weighted) among those without psoriasis (eTable 1). Although there was no statistically significant relationship between psoriasis and history of sunburn in patients aged 20 to 59 years, a subgroup analysis revealed a significant association between psoriasis and sunburn in adults aged 20 to 39 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted OR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.00-2.45]; P=.049)(eTable 2). Further analysis of subgroups showed no statistically significant results with adjustment of the logistic regression model. Characterizing response rates is important for assessing the validity of survey studies. The NHANES response rate from 2009 to 2014 was 72.9%, enhancing the reliability of our findings.

Our study revealed an increased prevalence of sunburn in US adults with psoriasis. A trend of increased sunburn prevalence among younger adults regardless of psoriasis status is corroborated by the literature. Surveys conducted in the United States in 2005, 2010, and 2015 showed that 43% to 50% of adults aged 18 to 39 years and 28% to 42% of those aged 40 to 59 years reported experiencing at least 1 sunburn within the respective survey year.6 Furthermore, in our study, patients with psoriasis reported higher rates of sunburn than their counterparts without psoriasis, both in those aged 20 to 39 years (psoriasis, 62.8% [73/136]; no psoriasis, 51.1% [2425/5840]) and those aged 40 to 59 years (psoriasis, 50.5% [n=75/179]; no psoriasis, 40.2% [1613/5652]), though it was only statistically significant in the 20-to-39 age group. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in sun-protective behaviors in younger vs older adults. A study from the NHANES database found that, among individuals aged 20 to 39 years, 75.9% [4225/5493] reported staying in the shade, 50.0% [2346/5493] reported using sunscreen, and 31.2% [1874/5493] reported wearing sun-protective clothing.7 Interestingly, the likelihood of engaging in all 3 behaviors was 28% lower in the 20-to-39 age group vs the 40-to-59 age group (adjusted OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62-0.83).7

While our analysis adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and tobacco use to mitigate potential confounding, we acknowledge the statistically significant differences observed in these variables between study groups as presented in eTable 2. These differences may reflect inherent disparities in the study population. We employed multivariable regression analysis to control for these covariates in our primary analyses. Of note, there was a statistically significant difference associated with race/ethnicity when comparing non-Hispanic White individuals with psoriasis (77.0% [n=182/315]) and those without psoriasis (62.5% [n=4516/11,492])(P<.0001)(eTable 1). The higher proportion of non-Hispanic White patients in the psoriasis group may reflect an increased susceptibility to sunburn given their typically lighter skin pigmentation; however, our analysis controlled for race/ethnicity (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of racial/ethnic differences. There also were statistically significant differences in tobacco use (P=.0026) and age (P=.002) in our unadjusted findings (eTable 1). Again, our analysis controlled for these factors (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of tobacco use and age differences. This approach enhanced the reliability of our findings.

The association between psoriasis and skin cancer has previously been evaluated using the NHANES database—one study found that patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer compared with those without psoriasis (3.0% vs 1.3%; relative risk, 2.29; P<.001).8 This difference remained significant after adjusting for confounding variables, as it was found that psoriasis was independently associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer (adjusted relative risk, 2.06; P=.004).8

The relationship between psoriasis and sunburn may be due to behavioral choices, such as the use of phototherapy for managing psoriasis due to its recognized advantages.9 Patients may seek out both artificial and natural light sources more frequently, potentially increasing the risk for sunburn.10 Psoriasis-related sunburn susceptibility may stem from biological factors, including vitamin D insufficiency, as vitamin D is crucial for keratinocyte differentiation, immune function, and UV protection and repair.11 One study examined the effects of high-dose vitamin D3 on sunburn-induced inflammation.12 Patients who received high-dose vitamin D3 exhibited reduced skin inflammation, enhanced skin barrier repair, and increased anti-inflammatory response compared with those who did not receive the supplement. This improvement was associated with upregulation of arginase 1, an anti-inflammatory enzyme, leading to decreased levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α and inducible nitric oxide synthase, thereby promoting tissue repair and reducing prolonged inflammation.12 These findings suggest that vitamin D insufficiency coupled with dysregulated immune responses may contribute to the heightened susceptibility of individuals with psoriasis to sunburn.

The established correlation between sunburn and skin cancer4,8 coupled with our findings of increased prevalence of sunburn in individuals with psoriasis underscores the need for additional research to clarify the underlying biological and behavioral factors that may contribute to a higher prevalence of sunburn in these patients, along with the implications for skin cancer development. Limitations of our study included potential recall bias, as individuals self-reported their clinical conditions and the inability to incorporate psoriasis severity into our analysis, as this was not consistently captured in the NHANES questionnaire during the study period.

To the Editor:

UV light plays an essential role in various environmental and biological processes.1 Excessive exposure to UV radiation can lead to sunburn, which is marked by skin erythema and pain.2 A study of more than 31,000 individuals found that 34.2% of adults aged 18 years and older reported at least 1 sunburn during the survey year.3 A lack of research regarding the incidence of sunburns in patients with psoriasis is particularly important considering the heightened incidence of skin cancer observed in this population.4 Thus, the aim of our study was to analyze the prevalence of sunburns among US adults with psoriasis utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database.5

Our analysis initially included 11,842 participants ranging in age from 20 to 59 years; 35 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and sunburn prevalence and thus were excluded. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18 (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and sunburns. Our models controlled for patient age, sex, income, race, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, and body mass index. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The study period from January 2009 to December 2014 was chosen based on the availability of the most recent and comprehensive psoriasis data within the NHANES database.

In the NHANES data we evaluated, psoriasis status was assessed by asking, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” History of sunburns in the survey year was assessed by the question, “How many times in the past year have you had sunburn?” Patients who reported 1 or more sunburns were included in the sunburn cohort, while those who did not report a sunburn were included in the no sunburn cohort.

In our analysis, the prevalence of at least 1 sunburn in the survey year in patients with psoriasis was 55.4% (weighted), compared to 45.6% (weighted) among those without psoriasis (eTable 1). Although there was no statistically significant relationship between psoriasis and history of sunburn in patients aged 20 to 59 years, a subgroup analysis revealed a significant association between psoriasis and sunburn in adults aged 20 to 39 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted OR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.00-2.45]; P=.049)(eTable 2). Further analysis of subgroups showed no statistically significant results with adjustment of the logistic regression model. Characterizing response rates is important for assessing the validity of survey studies. The NHANES response rate from 2009 to 2014 was 72.9%, enhancing the reliability of our findings.

Our study revealed an increased prevalence of sunburn in US adults with psoriasis. A trend of increased sunburn prevalence among younger adults regardless of psoriasis status is corroborated by the literature. Surveys conducted in the United States in 2005, 2010, and 2015 showed that 43% to 50% of adults aged 18 to 39 years and 28% to 42% of those aged 40 to 59 years reported experiencing at least 1 sunburn within the respective survey year.6 Furthermore, in our study, patients with psoriasis reported higher rates of sunburn than their counterparts without psoriasis, both in those aged 20 to 39 years (psoriasis, 62.8% [73/136]; no psoriasis, 51.1% [2425/5840]) and those aged 40 to 59 years (psoriasis, 50.5% [n=75/179]; no psoriasis, 40.2% [1613/5652]), though it was only statistically significant in the 20-to-39 age group. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in sun-protective behaviors in younger vs older adults. A study from the NHANES database found that, among individuals aged 20 to 39 years, 75.9% [4225/5493] reported staying in the shade, 50.0% [2346/5493] reported using sunscreen, and 31.2% [1874/5493] reported wearing sun-protective clothing.7 Interestingly, the likelihood of engaging in all 3 behaviors was 28% lower in the 20-to-39 age group vs the 40-to-59 age group (adjusted OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62-0.83).7

While our analysis adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and tobacco use to mitigate potential confounding, we acknowledge the statistically significant differences observed in these variables between study groups as presented in eTable 2. These differences may reflect inherent disparities in the study population. We employed multivariable regression analysis to control for these covariates in our primary analyses. Of note, there was a statistically significant difference associated with race/ethnicity when comparing non-Hispanic White individuals with psoriasis (77.0% [n=182/315]) and those without psoriasis (62.5% [n=4516/11,492])(P<.0001)(eTable 1). The higher proportion of non-Hispanic White patients in the psoriasis group may reflect an increased susceptibility to sunburn given their typically lighter skin pigmentation; however, our analysis controlled for race/ethnicity (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of racial/ethnic differences. There also were statistically significant differences in tobacco use (P=.0026) and age (P=.002) in our unadjusted findings (eTable 1). Again, our analysis controlled for these factors (eTable 2), thereby allowing us to isolate the effect of psoriasis on sunburn prevalence independent of tobacco use and age differences. This approach enhanced the reliability of our findings.

The association between psoriasis and skin cancer has previously been evaluated using the NHANES database—one study found that patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer compared with those without psoriasis (3.0% vs 1.3%; relative risk, 2.29; P<.001).8 This difference remained significant after adjusting for confounding variables, as it was found that psoriasis was independently associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer (adjusted relative risk, 2.06; P=.004).8

The relationship between psoriasis and sunburn may be due to behavioral choices, such as the use of phototherapy for managing psoriasis due to its recognized advantages.9 Patients may seek out both artificial and natural light sources more frequently, potentially increasing the risk for sunburn.10 Psoriasis-related sunburn susceptibility may stem from biological factors, including vitamin D insufficiency, as vitamin D is crucial for keratinocyte differentiation, immune function, and UV protection and repair.11 One study examined the effects of high-dose vitamin D3 on sunburn-induced inflammation.12 Patients who received high-dose vitamin D3 exhibited reduced skin inflammation, enhanced skin barrier repair, and increased anti-inflammatory response compared with those who did not receive the supplement. This improvement was associated with upregulation of arginase 1, an anti-inflammatory enzyme, leading to decreased levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α and inducible nitric oxide synthase, thereby promoting tissue repair and reducing prolonged inflammation.12 These findings suggest that vitamin D insufficiency coupled with dysregulated immune responses may contribute to the heightened susceptibility of individuals with psoriasis to sunburn.

The established correlation between sunburn and skin cancer4,8 coupled with our findings of increased prevalence of sunburn in individuals with psoriasis underscores the need for additional research to clarify the underlying biological and behavioral factors that may contribute to a higher prevalence of sunburn in these patients, along with the implications for skin cancer development. Limitations of our study included potential recall bias, as individuals self-reported their clinical conditions and the inability to incorporate psoriasis severity into our analysis, as this was not consistently captured in the NHANES questionnaire during the study period.

- Blaustein AR, Searle C. Ultraviolet radiation. In: Levin SA, ed. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2013:296-303.

- D’Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, et al. UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:12222-12248

- Holman DM, Ding H, Guy GP Jr, et al. Prevalence of sun protection use and sunburn and association of demographic and behavioral characteristics with sunburn among US adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:561-568.

- Balda A, Wani I, Roohi TF, et al. Psoriasis and skin cancer—is there a link? Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;121:110464.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Holman DM, Ding H, Berkowitz Z, et al. Sunburn prevalence among US adults, National Health Interview Survey 2005, 2010, and 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:817-820.

- Challapalli SD, Shetty KR, Bui Q, et al. Sun protective behaviors among adolescents and young adults in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2023;115:353-361.

- Herbosa CM, Hodges W, Mann C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: study of a nationally representative sample of the US population with comparison to a single]institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E529-E531.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Åkerla P, Pukkala E, Helminen M, et al. Skin cancer risk of narrow-band UV-B (TL-01) phototherapy: a multi-center registry study with 4,815 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv39927.

- Filoni A, Vestita M, Congedo M, et al. Association between psoriasis and vitamin D: duration of disease correlates with decreased vitamin D serum levels: an observational case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E11185.

- Scott JF, Das LM, Ahsanuddin S, et al. Oral vitamin D rapidly attenuates inflammation from sunburn: an interventional study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2078-2086.

- Blaustein AR, Searle C. Ultraviolet radiation. In: Levin SA, ed. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2013:296-303.

- D’Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, et al. UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:12222-12248

- Holman DM, Ding H, Guy GP Jr, et al. Prevalence of sun protection use and sunburn and association of demographic and behavioral characteristics with sunburn among US adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:561-568.

- Balda A, Wani I, Roohi TF, et al. Psoriasis and skin cancer—is there a link? Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;121:110464.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Holman DM, Ding H, Berkowitz Z, et al. Sunburn prevalence among US adults, National Health Interview Survey 2005, 2010, and 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:817-820.

- Challapalli SD, Shetty KR, Bui Q, et al. Sun protective behaviors among adolescents and young adults in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2023;115:353-361.

- Herbosa CM, Hodges W, Mann C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: study of a nationally representative sample of the US population with comparison to a single]institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E529-E531.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Åkerla P, Pukkala E, Helminen M, et al. Skin cancer risk of narrow-band UV-B (TL-01) phototherapy: a multi-center registry study with 4,815 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv39927.

- Filoni A, Vestita M, Congedo M, et al. Association between psoriasis and vitamin D: duration of disease correlates with decreased vitamin D serum levels: an observational case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E11185.

- Scott JF, Das LM, Ahsanuddin S, et al. Oral vitamin D rapidly attenuates inflammation from sunburn: an interventional study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2078-2086.

Association Between Psoriasis and Sunburn Prevalence in US Adults

Association Between Psoriasis and Sunburn Prevalence in US Adults

PRACTICE POINTS

- It is important for dermatologists to encourage rigorous sun-safety practices in patients with psoriasis, particularly those aged 20 to 59 years.

- A thorough sunburn history should be taken for skin cancer risk assessment in patients with psoriasis.

The Post-PASI Era: Considering Comorbidities to Select Appropriate Systemic Psoriasis Treatments

The Post-PASI Era: Considering Comorbidities to Select Appropriate Systemic Psoriasis Treatments

Psoriasis treatments have come a long way in the past 20 years. We now have more than a dozen systemic targeted treatments for psoriatic disease, with more on the way; however, with each successive class of medications introduced, the gap has narrowed in terms of increasing efficacy. In an era of medications reporting complete clearance rates in the 70% range, the average improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) for most biologics has remained at 90% to 95% in the past half-decade. While this is a far cry from the mean PASI improvements of 70% seen with the first biologics,1 it is becoming more challenging to base our treatment decisions solely on PASI outcome measures.

How, then, do we approach rational selection of a systemic psoriasis treatment? We could try to delineate based on mechanism of action, but it may be disingenuous to dissect minor differences in pathways (eg, IL-17 vs IL-23) that are fundamentally related and on the same continuum in psoriasis pathophysiology. Therefore, the most meaningful way to select an appropriate therapeutic may be to adopt a patient-centered approach that accounts for both individual preferences and specific medical needs by evaluating for other comorbidities2 to exclude or select certain medicines or types of treatments. We have long known to avoid tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors in patients with congestive heart failure or a history of demyelinating disorders while regularly considering the presence of psoriatic arthritis and family planning when making treatment decisions. Now, we can be more nuanced in our approaches to psoriasis biologics. Specifically, the most important comorbidities to consider broadly encompass cardiometabolic disorders, gastrointestinal conditions, and psychiatric conditions.

Cardiometabolic Disorders

Possibly the hottest topic in psoriasis for some years now, the relationship between cardiometabolic disorders and psoriasis is of great interest to clinicians, scientists, and patients alike. There is a clear link between development of atherosclerosis and Th17-related immune mechanisms that also are implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.3 Furthermore, the incidence of cardiovascular disease is markedly increased in patients with psoriasis, which is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction, particularly among younger patients.4,5 Although several retrospective studies6-8 have shown that TNF-α inhibitors are associated with a reduction in cardiovascular outcomes, it is yet to be seen whether biologic treatment actually has a direct impact on cardiovascular outcomes, multiple studies investigating the effect of biologics on arterial inflammation markers notwithstanding.9

There are some direct factors to keep in mind when considering cardiometabolic comorbidities in patients with psoriasis. Obesity is common in the psoriasis population and can have a direct negative effect on cardiovascular health.10 However, the data on obesity and psoriasis are somewhat mixed with regard to treatment outcomes. In general, with increased volumes of distribution for biologics in patients with obesity, it has been shown that treatment success is more difficult to achieve in those with a body mass index greater than 30.11 Rather surprisingly, a separate nationwide study in South Korea found that patients on biologics for psoriasis were more likely to experience weight gain, even after controlling for factors such as exercise, smoking, and drinking,12 but it is unclear whether this is driven mostly by a known connection between weight gain and TNF-α inhibitors.13 These contrasting results point to the need for further studies in this area, as our intuitive approach would involve promoting weight loss while starting on a systemic treatment for psoriasis—but perhaps it is important not to assume that one will come with the other in tow, reinforcing the need to discuss a healthy diet with our patients with psoriasis regardless of treatment decisions.

The data that we have do not directly answer the big questions about biologic treatment and cardiovascular health, but we are starting to see interesting signals. For example, in a report of tildrakizumab treatment in patients with and without metabolic syndrome, the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events as well as cardiac disorders were essentially the same in both groups after receiving treatment for up to 244 weeks.14 This is interesting, more because of the lack of an increase in cardiovascular adverse events in the metabolic syndrome group, who entered the trial on average 25 kg to 30 kg heavier than those without metabolic syndrome. There is an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events among patients with metabolic syndrome, a roughly 2-fold relative risk in as few as 5 to 6 years of follow-up.15 While the cohorts in the tildrakizumab study14 were too small to draw firm conclusions, the data are interesting and a step in the right direction; we need much larger data sets for analysis. Among other agents, similar efficacy and safety have been reported for guselkumab in a long-term psoriasis study; as a class, IL-23 inhibitors also tend to perform well from an efficacy standpoint in patients with obesity.16

Overall, when assessing the evidence for cardiometabolic disorders, it is reasonable to consider starting a biologic from the IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitor classes— thus avoiding both the potential downside of weight gain and contraindication in patients with congestive heart failure associated with TNF-α inhibitors. It is important to counsel patients about weight loss in conjunction with these treatments, both to improve efficacy and reduce cardiovascular risk factors. There may be a preference for IL-23 inhibitors in patients with obesity, as this class of medications maintains efficacy particularly well in these patients. Patients with psoriasis should be counseled to follow up with a primary care physician given their higher risk for metabolic syndrome and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Gastrointestinal Conditions

Psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a bidirectional association, and patients with psoriasis are about 1.7 times more likely to have either Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.17,18 This association may be related to a shared pathogenesis with regard to immune dysregulation and overactivated inflammatory pathways, but there are some important differences to consider from a therapeutic standpoint. Given the increased expression of IL-17 in patients with IBD,19 a phase II trial of secukinumab yielded surprising results—not only was secukinumab ineffective in treating Crohn disease, but there also were higher rates of adverse events20 (as noted on the product label for all IL-17 inhibitors). We have come to understand that there are regulatory subsets of IL-17 cells that are important in mucosal homeostasis and also regulate IL-10, which generally is considered an anti-inflammatory cytokine.21 Thus, while IL-17 inhibition can reduce some component of inflammatory signaling, it also can increase inflammatory signaling through indirect pathways while increasing intestinal permeability to microbes. Importantly, this process seems to occur via IL-23–independent pathways; as such, while direct inhibition of IL-17 can be deleterious, IL-23 inhibitors have become important therapeutics for IBD.22

IL-17 family, IL-17A clearly is the culprit for worsening colitis as evidenced by both human and animal models. On the contrary, IL-17F blockade has been shown to ameliorate colitis in a murine model, whereas IL-17A inhibition worsens it.23 Furthermore, dual blockade of IL-17A and IL-17F has a protective effect against colitis, suggesting that the IL-17F inhibition is dominant. This interesting finding has some mechanistic backing, since blockade of IL-17F induces Treg cells that serve to maintain gut epithelium homeostasis and integrity.24