User login

Acute Dyspnea: Try Physiologic Approach in Differential Diagnosis

DENVER – If you presume that a patient who comes to the emergency department with acute dyspnea primarily has a pulmonary cause, you’ll almost always be right. Those few other cases, though, take a bit of detective work.

In the approximately 5% of cases in which dyspnea is not easily referable to the lungs, the culprit may be a cardiac problem (usually in a very young child) or, rarely, other problems – hemoglobinopathies, diseases that cause metabolic acidosis, or neurologic disorders, Dr. Jeffrey Sankoff said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Take a physiologic approach that can guide you through the differential diagnosis, he suggested. "As somebody who trained in critical care, everything boils down to physiology," said Dr. Sankoff of the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of quality and patient safety at Denver Health Medical Center.

To begin, think of diseases that cause hypoxemia, hypercapnia, or metabolic acidosis, which lead to dyspnea.

Hypoxemia

The most common cause of hypoxemia is ventilation-perfusion (V-Q) mismatch, in which blood flows in the lungs but areas are not getting oxygen. Diffusion abnormalities, in which oxygen gets into alveoli but oxygen transit to the bloodstream is impaired, also cause hypoxemia. These occur in primary pulmonary disease.

But extrapulmonary disease processes create four causes of hypoxemia: a shunt, low mixed venous oxygen saturation (MVO2), decreased fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), and alveolar hypoventilation.

A V-Q mismatch at its most extreme is a shunt, in which blood bypasses the lungs altogether, he said. Disease processes that cause blood to go directly from the right to the left side of circulation result in hypoxemia. A shunt is almost always intracardiac, rarely intrapulmonary.

In children, shunts are seen at characteristic times for the development of cyanotic congenital heart disease, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus in an infant.

Look for a shunt by its hallmark – oxygen saturation will not improve when you give the patient oxygen. "This is the test for any young child under the age of 6 weeks who comes to the emergency department hypoxemic," Dr. Sankoff said.

Adults with shunts will have a murmur as well as dyspnea. "Adults don’t develop shunts de novo. This is going to be happening as part of some acute process," he said. The chest x-rays in adults with shunts often are normal.

The second cause of hypoxia – low MVO2 – occurs mainly when blood flows too slowly through the capillary bed, allowing excess oxygen extraction, and blood returns to the heart in a deoxygenated state. When you see this, focus on right ventricular impairment to identify the etiology. Left ventricular impairment will show up on x-ray as pulmonary edema. A right-sided infarction or cor pulmonale from pulmonary embolism will impair right ventricular function. Cardiac tamponade from infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic processes also can cause low MVO2 and dyspnea, though nobody really understands why, he added.

The third cause of hypoxia– decreased FiO– usually is a problem relegated to people at high altitudes or industrial workers in enclosed spaces, where hypoxemia (low partial pressure of oxygen in blood) causes hypoxia (low oxygen levels in tissues). But Dr. Sankoff uses this category to remind himself to look for diseases that are not associated with lower FiO2 and hypoxemia but still are associated with hypoxia – primarily hemoglobinopathies.

"If a patient has 100% oxygen saturation yet is hypoxic, they have a problem with hemoglobin," Dr. Sankoff said. It may be a severe or acute garden-variety anemia causing the dyspnea, or occasionally a hereditary hemoglobinopathy such as thalassemia or sickle cell disease. To diagnose these, have a high index of suspicion. You’ll see no patient improvement on oxygen therapy, and some diseases create a characteristic appearance of the blood.

Alveolar hypoventilation may be the most insidious cause of hypoxemia, and dyspnea and may be a flag for impending respiratory compromise if the patient has peripheral weakness. The most common acquired causes of peripheral neuromuscular weakness are Guillain-Barre syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Colorado tick paralysis.

Make the diagnosis in context with other findings, he said. Expect an abnormal motor exam. Check the negative inspiratory force; if it isn’t at least –20 cm H2O, it’s abnormal and the patient likely will need respiratory support.

Hypercapnia

Diseases that cause hypercapnia can cause dyspnea. Three things cause carbon dioxide levels in the blood to rise: increased metabolic rate (which tends to be seen in the ICU, not in the emergency department), decreased minute ventilation, and increased pulmonary dead space. All can be diagnosed by checking arterial blood gases.

Metabolic Acidosis

Acidosis, usually due to high levels of lactate, stimulates respiratory drive to try and balance pH. Sepsis is the most important cause of acidosis. When sepsis is developing, dyspnea frequently is a subtle sign. Have a high index of suspicion for sepsis, and be wary of a normal oxygen saturation level in a patient with dyspnea, he said. Other causes of metabolic acidosis that lead to dyspnea include diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis.

Putting this physiologic approach to dyspnea into context, consider three scenarios, Dr. Sankoff suggested. A patient with dyspnea who responds to oxygen therapy and has an abnormal chest x-ray has a primary pulmonary problem. A patient who responds to oxygen but has a normal chest x-ray may have sepsis, another cause of acidosis, or alveolar hypoventilation; their response to oxygen may be transient. They will respond to oxygen but continue to be tachypneic.

The third scenario – normal x-ray, but the patient does not respond to oxygen therapy – raises a broad differential diagnosis including sepsis, other causes of acidosis, hypercapnia, cardiac causes, and hemoglobinopathies. Narrow the differential by recalling the history and physical findings and getting arterial blood gas tests.

Only after everything else has been excluded should you consider anxiety or pain as the cause of dyspnea, he said.

Dr. Sankoff reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – If you presume that a patient who comes to the emergency department with acute dyspnea primarily has a pulmonary cause, you’ll almost always be right. Those few other cases, though, take a bit of detective work.

In the approximately 5% of cases in which dyspnea is not easily referable to the lungs, the culprit may be a cardiac problem (usually in a very young child) or, rarely, other problems – hemoglobinopathies, diseases that cause metabolic acidosis, or neurologic disorders, Dr. Jeffrey Sankoff said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Take a physiologic approach that can guide you through the differential diagnosis, he suggested. "As somebody who trained in critical care, everything boils down to physiology," said Dr. Sankoff of the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of quality and patient safety at Denver Health Medical Center.

To begin, think of diseases that cause hypoxemia, hypercapnia, or metabolic acidosis, which lead to dyspnea.

Hypoxemia

The most common cause of hypoxemia is ventilation-perfusion (V-Q) mismatch, in which blood flows in the lungs but areas are not getting oxygen. Diffusion abnormalities, in which oxygen gets into alveoli but oxygen transit to the bloodstream is impaired, also cause hypoxemia. These occur in primary pulmonary disease.

But extrapulmonary disease processes create four causes of hypoxemia: a shunt, low mixed venous oxygen saturation (MVO2), decreased fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), and alveolar hypoventilation.

A V-Q mismatch at its most extreme is a shunt, in which blood bypasses the lungs altogether, he said. Disease processes that cause blood to go directly from the right to the left side of circulation result in hypoxemia. A shunt is almost always intracardiac, rarely intrapulmonary.

In children, shunts are seen at characteristic times for the development of cyanotic congenital heart disease, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus in an infant.

Look for a shunt by its hallmark – oxygen saturation will not improve when you give the patient oxygen. "This is the test for any young child under the age of 6 weeks who comes to the emergency department hypoxemic," Dr. Sankoff said.

Adults with shunts will have a murmur as well as dyspnea. "Adults don’t develop shunts de novo. This is going to be happening as part of some acute process," he said. The chest x-rays in adults with shunts often are normal.

The second cause of hypoxia – low MVO2 – occurs mainly when blood flows too slowly through the capillary bed, allowing excess oxygen extraction, and blood returns to the heart in a deoxygenated state. When you see this, focus on right ventricular impairment to identify the etiology. Left ventricular impairment will show up on x-ray as pulmonary edema. A right-sided infarction or cor pulmonale from pulmonary embolism will impair right ventricular function. Cardiac tamponade from infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic processes also can cause low MVO2 and dyspnea, though nobody really understands why, he added.

The third cause of hypoxia– decreased FiO– usually is a problem relegated to people at high altitudes or industrial workers in enclosed spaces, where hypoxemia (low partial pressure of oxygen in blood) causes hypoxia (low oxygen levels in tissues). But Dr. Sankoff uses this category to remind himself to look for diseases that are not associated with lower FiO2 and hypoxemia but still are associated with hypoxia – primarily hemoglobinopathies.

"If a patient has 100% oxygen saturation yet is hypoxic, they have a problem with hemoglobin," Dr. Sankoff said. It may be a severe or acute garden-variety anemia causing the dyspnea, or occasionally a hereditary hemoglobinopathy such as thalassemia or sickle cell disease. To diagnose these, have a high index of suspicion. You’ll see no patient improvement on oxygen therapy, and some diseases create a characteristic appearance of the blood.

Alveolar hypoventilation may be the most insidious cause of hypoxemia, and dyspnea and may be a flag for impending respiratory compromise if the patient has peripheral weakness. The most common acquired causes of peripheral neuromuscular weakness are Guillain-Barre syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Colorado tick paralysis.

Make the diagnosis in context with other findings, he said. Expect an abnormal motor exam. Check the negative inspiratory force; if it isn’t at least –20 cm H2O, it’s abnormal and the patient likely will need respiratory support.

Hypercapnia

Diseases that cause hypercapnia can cause dyspnea. Three things cause carbon dioxide levels in the blood to rise: increased metabolic rate (which tends to be seen in the ICU, not in the emergency department), decreased minute ventilation, and increased pulmonary dead space. All can be diagnosed by checking arterial blood gases.

Metabolic Acidosis

Acidosis, usually due to high levels of lactate, stimulates respiratory drive to try and balance pH. Sepsis is the most important cause of acidosis. When sepsis is developing, dyspnea frequently is a subtle sign. Have a high index of suspicion for sepsis, and be wary of a normal oxygen saturation level in a patient with dyspnea, he said. Other causes of metabolic acidosis that lead to dyspnea include diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis.

Putting this physiologic approach to dyspnea into context, consider three scenarios, Dr. Sankoff suggested. A patient with dyspnea who responds to oxygen therapy and has an abnormal chest x-ray has a primary pulmonary problem. A patient who responds to oxygen but has a normal chest x-ray may have sepsis, another cause of acidosis, or alveolar hypoventilation; their response to oxygen may be transient. They will respond to oxygen but continue to be tachypneic.

The third scenario – normal x-ray, but the patient does not respond to oxygen therapy – raises a broad differential diagnosis including sepsis, other causes of acidosis, hypercapnia, cardiac causes, and hemoglobinopathies. Narrow the differential by recalling the history and physical findings and getting arterial blood gas tests.

Only after everything else has been excluded should you consider anxiety or pain as the cause of dyspnea, he said.

Dr. Sankoff reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – If you presume that a patient who comes to the emergency department with acute dyspnea primarily has a pulmonary cause, you’ll almost always be right. Those few other cases, though, take a bit of detective work.

In the approximately 5% of cases in which dyspnea is not easily referable to the lungs, the culprit may be a cardiac problem (usually in a very young child) or, rarely, other problems – hemoglobinopathies, diseases that cause metabolic acidosis, or neurologic disorders, Dr. Jeffrey Sankoff said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Take a physiologic approach that can guide you through the differential diagnosis, he suggested. "As somebody who trained in critical care, everything boils down to physiology," said Dr. Sankoff of the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of quality and patient safety at Denver Health Medical Center.

To begin, think of diseases that cause hypoxemia, hypercapnia, or metabolic acidosis, which lead to dyspnea.

Hypoxemia

The most common cause of hypoxemia is ventilation-perfusion (V-Q) mismatch, in which blood flows in the lungs but areas are not getting oxygen. Diffusion abnormalities, in which oxygen gets into alveoli but oxygen transit to the bloodstream is impaired, also cause hypoxemia. These occur in primary pulmonary disease.

But extrapulmonary disease processes create four causes of hypoxemia: a shunt, low mixed venous oxygen saturation (MVO2), decreased fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), and alveolar hypoventilation.

A V-Q mismatch at its most extreme is a shunt, in which blood bypasses the lungs altogether, he said. Disease processes that cause blood to go directly from the right to the left side of circulation result in hypoxemia. A shunt is almost always intracardiac, rarely intrapulmonary.

In children, shunts are seen at characteristic times for the development of cyanotic congenital heart disease, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus in an infant.

Look for a shunt by its hallmark – oxygen saturation will not improve when you give the patient oxygen. "This is the test for any young child under the age of 6 weeks who comes to the emergency department hypoxemic," Dr. Sankoff said.

Adults with shunts will have a murmur as well as dyspnea. "Adults don’t develop shunts de novo. This is going to be happening as part of some acute process," he said. The chest x-rays in adults with shunts often are normal.

The second cause of hypoxia – low MVO2 – occurs mainly when blood flows too slowly through the capillary bed, allowing excess oxygen extraction, and blood returns to the heart in a deoxygenated state. When you see this, focus on right ventricular impairment to identify the etiology. Left ventricular impairment will show up on x-ray as pulmonary edema. A right-sided infarction or cor pulmonale from pulmonary embolism will impair right ventricular function. Cardiac tamponade from infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic processes also can cause low MVO2 and dyspnea, though nobody really understands why, he added.

The third cause of hypoxia– decreased FiO– usually is a problem relegated to people at high altitudes or industrial workers in enclosed spaces, where hypoxemia (low partial pressure of oxygen in blood) causes hypoxia (low oxygen levels in tissues). But Dr. Sankoff uses this category to remind himself to look for diseases that are not associated with lower FiO2 and hypoxemia but still are associated with hypoxia – primarily hemoglobinopathies.

"If a patient has 100% oxygen saturation yet is hypoxic, they have a problem with hemoglobin," Dr. Sankoff said. It may be a severe or acute garden-variety anemia causing the dyspnea, or occasionally a hereditary hemoglobinopathy such as thalassemia or sickle cell disease. To diagnose these, have a high index of suspicion. You’ll see no patient improvement on oxygen therapy, and some diseases create a characteristic appearance of the blood.

Alveolar hypoventilation may be the most insidious cause of hypoxemia, and dyspnea and may be a flag for impending respiratory compromise if the patient has peripheral weakness. The most common acquired causes of peripheral neuromuscular weakness are Guillain-Barre syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Colorado tick paralysis.

Make the diagnosis in context with other findings, he said. Expect an abnormal motor exam. Check the negative inspiratory force; if it isn’t at least –20 cm H2O, it’s abnormal and the patient likely will need respiratory support.

Hypercapnia

Diseases that cause hypercapnia can cause dyspnea. Three things cause carbon dioxide levels in the blood to rise: increased metabolic rate (which tends to be seen in the ICU, not in the emergency department), decreased minute ventilation, and increased pulmonary dead space. All can be diagnosed by checking arterial blood gases.

Metabolic Acidosis

Acidosis, usually due to high levels of lactate, stimulates respiratory drive to try and balance pH. Sepsis is the most important cause of acidosis. When sepsis is developing, dyspnea frequently is a subtle sign. Have a high index of suspicion for sepsis, and be wary of a normal oxygen saturation level in a patient with dyspnea, he said. Other causes of metabolic acidosis that lead to dyspnea include diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis.

Putting this physiologic approach to dyspnea into context, consider three scenarios, Dr. Sankoff suggested. A patient with dyspnea who responds to oxygen therapy and has an abnormal chest x-ray has a primary pulmonary problem. A patient who responds to oxygen but has a normal chest x-ray may have sepsis, another cause of acidosis, or alveolar hypoventilation; their response to oxygen may be transient. They will respond to oxygen but continue to be tachypneic.

The third scenario – normal x-ray, but the patient does not respond to oxygen therapy – raises a broad differential diagnosis including sepsis, other causes of acidosis, hypercapnia, cardiac causes, and hemoglobinopathies. Narrow the differential by recalling the history and physical findings and getting arterial blood gas tests.

Only after everything else has been excluded should you consider anxiety or pain as the cause of dyspnea, he said.

Dr. Sankoff reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF EMERGENCY PHYSICIANS

Earlier End-of-Life Talks Deter Aggressive Care of Terminal Cancer Patients

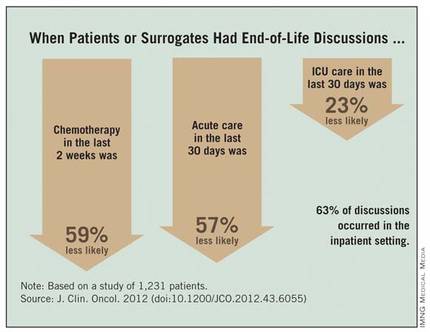

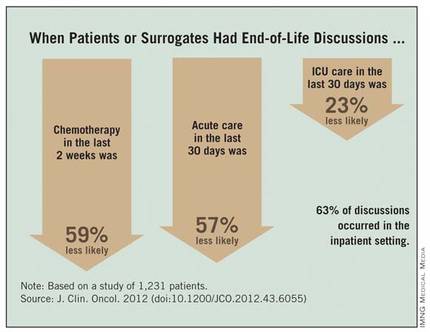

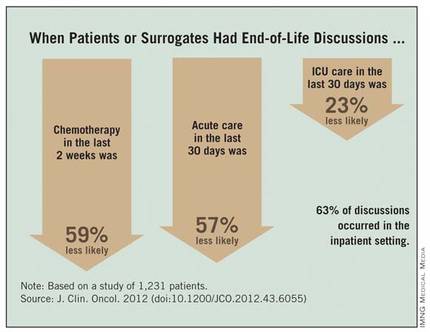

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major Finding: Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or their surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Data Source: This was a longitudinal study of 1,231 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer at HMOs or Veterans Affairs sites in five states.

Disclosures: Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Pediatric Psychiatry Services Infiltrate Primary Care

SAN FRANCISCO – After more than 2 decades as a primary care pediatrician, Dr. Teresa M. Hargrave was so frustrated by the lack of psychiatric services for her patients that she retrained as a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Now, she’s part of a New York state program that spreads her psychiatric skills to more patients than she imagined could be possible.

"If this program had been in place when I was a pediatrician, I would never have had to switch," said Dr. Hargrave of the State University of New York (SUNY) in Syracuse.

Today, New York primary care physicians can call 855-227-7272 toll free on weekdays for an immediate consultation with a master’s level therapist in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care program (CAP PC). If a patient seems to need psychotropic medication, the therapist connects the pediatrician with a psychiatrist on the program’s team, such as Dr. Hargrave, who helps the primary care physician manage treatment through phone consultations and, if needed, in-person assessments.

Dozens of similar efforts – in a variety of formats – have sprung up across the country. They’re all trying to address a fundamental mismatch: There are only 7,400 practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists in the United States but more than 15 million young people in those age groups who need psychiatric care, according to data analyses from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs acts as a hub for these programs in 24 states, with programs in 4 more states set to take their first calls soon.

These model programs are making great inroads in getting care to the estimated 15%-25% of children seen in primary care offices who have behavioral health disorders, but reimbursement problems create a roadblock that must be overcome in the years ahead for the programs to be fully effective, several experts said in interviews at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

New York Program

New York’s CAP PC program modeled itself after one of the first state-wide programs, the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project, with some key changes. The CAP PC program covers 95% of the New York state population but uses the same toll-free number everywhere, compared with multiple different phone numbers being used in different regions in Massachusetts. New York’s program also added an educational component for primary care physicians – a free 15-hour "Mini-Fellowship" weekend program followed by a dozen 1-hour biweekly case-based conference calls.

Primary care physicians seem to love the help, Dr. David Kaye said at a poster presentation at the meeting. In its 2 years of operation, the CAP PC program has registered 829 primary care physicians (80% pediatricians, 20% family physicians), 292 of whom took the training sessions. The program handled 1,016 intake and follow-up calls, provided 993 consultations with a psychiatrist, conducted 94 face-to-face evaluations, and referred 305 patients to other services, reported Dr. Kaye, professor of psychiatry and director of child and adolescent psychiatry training at SUNY in Buffalo, N.Y.

Among 325 primary care physicians surveyed 2 weeks after contact with the CAP PC program, 94% said the consultations were very or extremely helpful, and 99% said they would recommend the program to other primary care physicians.

The program has greatly increased the number of children accessing psychiatric services compared with a previous pilot program in central New York that provided immediate telephone referrals and psychiatric consultation within 24 hours of a request, Dr. Hargrave said in a separate poster presentation at the meeting.

The CAP PC program improved upon the pilot by offering psychiatric consultation within 2 hours of a request, occasional in-person consultations, the education program, and a centralized computer database that allows the therapists and psychiatrists on different shifts to access patient records quickly, she said.

Compared with data from 2 years of the pilot program, data from the CAP PC program in the central New York area showed an increase in the number of children served from 6 to 14 per month (a 133% gain), an increase in the number of clinicians involved from 77 to 116 per month (a 51% gain), and an increase in the proportion of patients managed within the primary care office because of a decrease in the rate of referrals to more expensive specialists from 39% to 22%, Dr. Hargrave reported.

"The amount of morbidity that primary care physicians are coping with is amazing," especially in rural areas, she said.

Texas Model

A different model in Texas significantly decreased psychiatric symptoms and improved quality of life in children and adolescents participating in the program, Dr. Steven R. Pliszka reported in another poster presentation.

The Services Uniting Pediatrics and Psychiatry Outreaching to Texas (SUPPORT) program, funded by the Department of State Health Services, placed master’s level licensed therapists into primary care pediatric practices in six regions across the state. These therapists tried to see patients the same day that pediatricians referred them, and typically saw each patient for one to six sessions of practical, problem-focused therapies. A consulting child and adolescent psychiatrist helped determine which patients might need psychotropic medication and advised pediatricians on drug choice, dosing, and monitoring.

The SUPPORT program enrolled 145 pediatricians and 14,582 children covered by Medicaid. The outcomes evaluation involved a subset of 4,047 patients who were assessed at baseline, 3 month, and 6 months using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).

In both younger (1.5-5 years of age) and older children (5-18 years), scores significantly decreased on the internalizing, externalizing, and total scales of the CBCL as well as on the individual symptom scales. Scores on the PedsQL improved significantly in each of four age groups (2-4 years, 5-7 years, 8-12 years, and 13-18 years), said Dr. Pliszka, professor and chair of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Mean total scores on the CBCL, for example, decreased from approximately 63 to about 53 at 6 months. Mean PedsQL scores at baseline ranged approximately from 68 to 71 at baseline (depending on the age group) and increased to a range of about 77-81.

Data on diagnoses and prescriptions tracked by the program suggest that the pediatricians prescribed appropriate medications to the 2,207 patients who received at least one psychotropic medication (15% of all patients), Dr. Pliszka said.

"So, kids with ADHD got treated with a stimulant, kids with depression got an antidepressant, [and] kids with bipolar disorder got combinations of different medications. We also did not have any really bad outcomes. There were no suicides, no serious adverse drug effects. It shows that the model is a way to treat even fairly serious mental illnesses in the primary care setting," he said.

Dr. Pliszka and his associates next plan to compare outcomes for patients managed through SUPPORT and usual care (referral by primary care physicians to mental health clinics in the community).

Reimbursement Issues

Government and academic funds support these programs for now, but better funding mechanisms for collaborative care are needed for long-term sustainability, each of the physicians interviewed said.

New York’s CAP PC is a collaboration among five academic centers that is funded by a grant from the State Office of Mental Health. The SUPPORT program received Medicaid support in Texas.

While there probably are enough master’s level therapists to expand SUPPORT beyond the Medicaid population, "what’s lacking is that it’s difficult for both the pediatrician and the master’s level person to get reimbursed for that type of activity because they use completely different codes," Dr. Pliszka said. "Projects of this type would make the argument for modifying the reimbursement system to allow more integrated care."

Part of CAP PC’s education program helps New York primary care physicians get comfortable with coding for their mental health work, but there are gaps in that approach, Dr. Kaye said. "In some of our regions, docs can be paid reasonably for what they’re doing, but in lots of places, they can’t put in a code for ADHD or depression and get reimbursed" because insurers say they’re not credentialed mental health providers.

"There’s got to be a way on the payment side that Medicaid and/or the insurers figure out how to pay primary care docs to do this work, and to pay them fairly," he said. "I think this is going to be a huge part of the future of primary care. The numbers are that mental health problems are the most common chronic condition that kids get."

Even for the psychiatrists involved, the current model is not sustainable, he added. The New York grant pays each of the five academic centers for a 10-hour day of consultation each week, which is far less than the actual hours contributed.

"We’re all university based. We believe in the project, so we’ve been able to sustain that. Can we do that for 20 years? I don’t know," Dr. Kaye said.

"The major drawback is that it takes time, and insurance does not reimburse for that time. To really get such a system as this off the ground or well integrated" will require reimbursement for the time spent by all the health care providers involved, Dr. Hargrave said.

She said she hopes that in the future, all children and primary care clinicians will have access to mental health care, advice and support, "and that the clinicians – whether primary care or psychiatric – could be paid adequately for the work that we do."

Dr. Pliszka reported financial associations with Shire Pharmaceuticals and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kaye and Dr. Hargrave received research support from the New York State Office of Mental Health. Some of their coinvestigators reported financial associations with the Resource for Advancing Children’s Health Institute, American Psychiatric Publishing, Marriott Foundation, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen.

SAN FRANCISCO – After more than 2 decades as a primary care pediatrician, Dr. Teresa M. Hargrave was so frustrated by the lack of psychiatric services for her patients that she retrained as a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Now, she’s part of a New York state program that spreads her psychiatric skills to more patients than she imagined could be possible.

"If this program had been in place when I was a pediatrician, I would never have had to switch," said Dr. Hargrave of the State University of New York (SUNY) in Syracuse.

Today, New York primary care physicians can call 855-227-7272 toll free on weekdays for an immediate consultation with a master’s level therapist in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care program (CAP PC). If a patient seems to need psychotropic medication, the therapist connects the pediatrician with a psychiatrist on the program’s team, such as Dr. Hargrave, who helps the primary care physician manage treatment through phone consultations and, if needed, in-person assessments.

Dozens of similar efforts – in a variety of formats – have sprung up across the country. They’re all trying to address a fundamental mismatch: There are only 7,400 practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists in the United States but more than 15 million young people in those age groups who need psychiatric care, according to data analyses from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs acts as a hub for these programs in 24 states, with programs in 4 more states set to take their first calls soon.

These model programs are making great inroads in getting care to the estimated 15%-25% of children seen in primary care offices who have behavioral health disorders, but reimbursement problems create a roadblock that must be overcome in the years ahead for the programs to be fully effective, several experts said in interviews at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

New York Program

New York’s CAP PC program modeled itself after one of the first state-wide programs, the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project, with some key changes. The CAP PC program covers 95% of the New York state population but uses the same toll-free number everywhere, compared with multiple different phone numbers being used in different regions in Massachusetts. New York’s program also added an educational component for primary care physicians – a free 15-hour "Mini-Fellowship" weekend program followed by a dozen 1-hour biweekly case-based conference calls.

Primary care physicians seem to love the help, Dr. David Kaye said at a poster presentation at the meeting. In its 2 years of operation, the CAP PC program has registered 829 primary care physicians (80% pediatricians, 20% family physicians), 292 of whom took the training sessions. The program handled 1,016 intake and follow-up calls, provided 993 consultations with a psychiatrist, conducted 94 face-to-face evaluations, and referred 305 patients to other services, reported Dr. Kaye, professor of psychiatry and director of child and adolescent psychiatry training at SUNY in Buffalo, N.Y.

Among 325 primary care physicians surveyed 2 weeks after contact with the CAP PC program, 94% said the consultations were very or extremely helpful, and 99% said they would recommend the program to other primary care physicians.

The program has greatly increased the number of children accessing psychiatric services compared with a previous pilot program in central New York that provided immediate telephone referrals and psychiatric consultation within 24 hours of a request, Dr. Hargrave said in a separate poster presentation at the meeting.

The CAP PC program improved upon the pilot by offering psychiatric consultation within 2 hours of a request, occasional in-person consultations, the education program, and a centralized computer database that allows the therapists and psychiatrists on different shifts to access patient records quickly, she said.

Compared with data from 2 years of the pilot program, data from the CAP PC program in the central New York area showed an increase in the number of children served from 6 to 14 per month (a 133% gain), an increase in the number of clinicians involved from 77 to 116 per month (a 51% gain), and an increase in the proportion of patients managed within the primary care office because of a decrease in the rate of referrals to more expensive specialists from 39% to 22%, Dr. Hargrave reported.

"The amount of morbidity that primary care physicians are coping with is amazing," especially in rural areas, she said.

Texas Model

A different model in Texas significantly decreased psychiatric symptoms and improved quality of life in children and adolescents participating in the program, Dr. Steven R. Pliszka reported in another poster presentation.

The Services Uniting Pediatrics and Psychiatry Outreaching to Texas (SUPPORT) program, funded by the Department of State Health Services, placed master’s level licensed therapists into primary care pediatric practices in six regions across the state. These therapists tried to see patients the same day that pediatricians referred them, and typically saw each patient for one to six sessions of practical, problem-focused therapies. A consulting child and adolescent psychiatrist helped determine which patients might need psychotropic medication and advised pediatricians on drug choice, dosing, and monitoring.

The SUPPORT program enrolled 145 pediatricians and 14,582 children covered by Medicaid. The outcomes evaluation involved a subset of 4,047 patients who were assessed at baseline, 3 month, and 6 months using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).

In both younger (1.5-5 years of age) and older children (5-18 years), scores significantly decreased on the internalizing, externalizing, and total scales of the CBCL as well as on the individual symptom scales. Scores on the PedsQL improved significantly in each of four age groups (2-4 years, 5-7 years, 8-12 years, and 13-18 years), said Dr. Pliszka, professor and chair of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Mean total scores on the CBCL, for example, decreased from approximately 63 to about 53 at 6 months. Mean PedsQL scores at baseline ranged approximately from 68 to 71 at baseline (depending on the age group) and increased to a range of about 77-81.

Data on diagnoses and prescriptions tracked by the program suggest that the pediatricians prescribed appropriate medications to the 2,207 patients who received at least one psychotropic medication (15% of all patients), Dr. Pliszka said.

"So, kids with ADHD got treated with a stimulant, kids with depression got an antidepressant, [and] kids with bipolar disorder got combinations of different medications. We also did not have any really bad outcomes. There were no suicides, no serious adverse drug effects. It shows that the model is a way to treat even fairly serious mental illnesses in the primary care setting," he said.

Dr. Pliszka and his associates next plan to compare outcomes for patients managed through SUPPORT and usual care (referral by primary care physicians to mental health clinics in the community).

Reimbursement Issues

Government and academic funds support these programs for now, but better funding mechanisms for collaborative care are needed for long-term sustainability, each of the physicians interviewed said.

New York’s CAP PC is a collaboration among five academic centers that is funded by a grant from the State Office of Mental Health. The SUPPORT program received Medicaid support in Texas.

While there probably are enough master’s level therapists to expand SUPPORT beyond the Medicaid population, "what’s lacking is that it’s difficult for both the pediatrician and the master’s level person to get reimbursed for that type of activity because they use completely different codes," Dr. Pliszka said. "Projects of this type would make the argument for modifying the reimbursement system to allow more integrated care."

Part of CAP PC’s education program helps New York primary care physicians get comfortable with coding for their mental health work, but there are gaps in that approach, Dr. Kaye said. "In some of our regions, docs can be paid reasonably for what they’re doing, but in lots of places, they can’t put in a code for ADHD or depression and get reimbursed" because insurers say they’re not credentialed mental health providers.

"There’s got to be a way on the payment side that Medicaid and/or the insurers figure out how to pay primary care docs to do this work, and to pay them fairly," he said. "I think this is going to be a huge part of the future of primary care. The numbers are that mental health problems are the most common chronic condition that kids get."

Even for the psychiatrists involved, the current model is not sustainable, he added. The New York grant pays each of the five academic centers for a 10-hour day of consultation each week, which is far less than the actual hours contributed.

"We’re all university based. We believe in the project, so we’ve been able to sustain that. Can we do that for 20 years? I don’t know," Dr. Kaye said.

"The major drawback is that it takes time, and insurance does not reimburse for that time. To really get such a system as this off the ground or well integrated" will require reimbursement for the time spent by all the health care providers involved, Dr. Hargrave said.

She said she hopes that in the future, all children and primary care clinicians will have access to mental health care, advice and support, "and that the clinicians – whether primary care or psychiatric – could be paid adequately for the work that we do."

Dr. Pliszka reported financial associations with Shire Pharmaceuticals and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kaye and Dr. Hargrave received research support from the New York State Office of Mental Health. Some of their coinvestigators reported financial associations with the Resource for Advancing Children’s Health Institute, American Psychiatric Publishing, Marriott Foundation, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen.

SAN FRANCISCO – After more than 2 decades as a primary care pediatrician, Dr. Teresa M. Hargrave was so frustrated by the lack of psychiatric services for her patients that she retrained as a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Now, she’s part of a New York state program that spreads her psychiatric skills to more patients than she imagined could be possible.

"If this program had been in place when I was a pediatrician, I would never have had to switch," said Dr. Hargrave of the State University of New York (SUNY) in Syracuse.

Today, New York primary care physicians can call 855-227-7272 toll free on weekdays for an immediate consultation with a master’s level therapist in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care program (CAP PC). If a patient seems to need psychotropic medication, the therapist connects the pediatrician with a psychiatrist on the program’s team, such as Dr. Hargrave, who helps the primary care physician manage treatment through phone consultations and, if needed, in-person assessments.

Dozens of similar efforts – in a variety of formats – have sprung up across the country. They’re all trying to address a fundamental mismatch: There are only 7,400 practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists in the United States but more than 15 million young people in those age groups who need psychiatric care, according to data analyses from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs acts as a hub for these programs in 24 states, with programs in 4 more states set to take their first calls soon.

These model programs are making great inroads in getting care to the estimated 15%-25% of children seen in primary care offices who have behavioral health disorders, but reimbursement problems create a roadblock that must be overcome in the years ahead for the programs to be fully effective, several experts said in interviews at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

New York Program

New York’s CAP PC program modeled itself after one of the first state-wide programs, the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project, with some key changes. The CAP PC program covers 95% of the New York state population but uses the same toll-free number everywhere, compared with multiple different phone numbers being used in different regions in Massachusetts. New York’s program also added an educational component for primary care physicians – a free 15-hour "Mini-Fellowship" weekend program followed by a dozen 1-hour biweekly case-based conference calls.

Primary care physicians seem to love the help, Dr. David Kaye said at a poster presentation at the meeting. In its 2 years of operation, the CAP PC program has registered 829 primary care physicians (80% pediatricians, 20% family physicians), 292 of whom took the training sessions. The program handled 1,016 intake and follow-up calls, provided 993 consultations with a psychiatrist, conducted 94 face-to-face evaluations, and referred 305 patients to other services, reported Dr. Kaye, professor of psychiatry and director of child and adolescent psychiatry training at SUNY in Buffalo, N.Y.

Among 325 primary care physicians surveyed 2 weeks after contact with the CAP PC program, 94% said the consultations were very or extremely helpful, and 99% said they would recommend the program to other primary care physicians.

The program has greatly increased the number of children accessing psychiatric services compared with a previous pilot program in central New York that provided immediate telephone referrals and psychiatric consultation within 24 hours of a request, Dr. Hargrave said in a separate poster presentation at the meeting.

The CAP PC program improved upon the pilot by offering psychiatric consultation within 2 hours of a request, occasional in-person consultations, the education program, and a centralized computer database that allows the therapists and psychiatrists on different shifts to access patient records quickly, she said.

Compared with data from 2 years of the pilot program, data from the CAP PC program in the central New York area showed an increase in the number of children served from 6 to 14 per month (a 133% gain), an increase in the number of clinicians involved from 77 to 116 per month (a 51% gain), and an increase in the proportion of patients managed within the primary care office because of a decrease in the rate of referrals to more expensive specialists from 39% to 22%, Dr. Hargrave reported.

"The amount of morbidity that primary care physicians are coping with is amazing," especially in rural areas, she said.

Texas Model

A different model in Texas significantly decreased psychiatric symptoms and improved quality of life in children and adolescents participating in the program, Dr. Steven R. Pliszka reported in another poster presentation.

The Services Uniting Pediatrics and Psychiatry Outreaching to Texas (SUPPORT) program, funded by the Department of State Health Services, placed master’s level licensed therapists into primary care pediatric practices in six regions across the state. These therapists tried to see patients the same day that pediatricians referred them, and typically saw each patient for one to six sessions of practical, problem-focused therapies. A consulting child and adolescent psychiatrist helped determine which patients might need psychotropic medication and advised pediatricians on drug choice, dosing, and monitoring.

The SUPPORT program enrolled 145 pediatricians and 14,582 children covered by Medicaid. The outcomes evaluation involved a subset of 4,047 patients who were assessed at baseline, 3 month, and 6 months using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).