User login

Standardize Communication to Reduce Medical Errors

DENVER – Do you speak in SBAR?

If not, communication in your department probably could be better, two speakers said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, in a session on improving teamwork.

SBAR is the acronym for a standardized communication format that organizes the transfer of information under four themes – situation, background; assessment, and recommendation. Developed by anesthesiologist Dr. Michael Leonard and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, Evergreen, the SBAR tool has been endorsed by many national organizations and medical accreditation bodies, said Dr. Jennifer L. Wiler.

It originally was used for acute-care communications from nurses to physicians but now is being used more widely for communication from nurse to nurse and from physician to physician in a variety of care settings. One study found that it was particularly useful for reporting changes in a patient’s status or a patient’s deterioration between health care services or shifts (Healthcare Quarterly 2008;11:72-9).

Using SBAR won’t necessarily save you time – at least one study suggests it increases time for communications. The limited data from seven published studies so far suggest that SBAR use improves the transfer of important information, the perception of a culture of safety, and patient satisfaction, though SBAR has yet to be validated in an emergency department setting, said Dr. Wiler of the University of Colorado, Aurora.

It has worked in hospital medicine. Hospitalists with Kaiser Permanente found SBAR to be helpful, according to a study conducted from May 2008 to August 2009. SBAR was used for end-of-rotation patient handoffs, the researchers wrote. "The Hospitalist Chief finds SBAR useful when communicating with consultants, especially during the initial telephone conversation when it is important for hospitalists to clearly state information needs." Hospitalists communicate primarily with ED physicians, and "communications with KP ED physicians is superb; [we] get a complete diagnosis" (Perm. J. 2011 Summer;15:51-60).

The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) list communication problems as the No. 1 cause of medical error, she noted. "Addressing errors related to communication is really critical," Dr. Wiler said.

To communicate in SBAR, use the following structure:

– Situation. Identify yourself, your occupation and where you are calling from, if speaking by phone. Identify the patient – the name, date of birth, age, and sex, and the reason for your report. Describe the current status of the patient or your reason for calling. If it’s urgent, say so.

– Background. Give the patient’s presenting complaint, any relevant past medical history, and a brief summary of background.

– Assessment. Describe abnormal vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, pain scale, or level of consciousness). Provide your clinical impression, the severity of the patient’s situation, and any additional concerns.

– Recommendation. Explain what you require, how urgently, and when action needs to be taken. Suggest what action might be taken. Clarify what action you expect to be taken.

One of the challenges to good communication is that physicians and nurses practice in parallel environments and too seldom prioritize teamwork, said Eric Christensen, R.N.

Beyond SBAR, a variety of strategies can improve communication between team members, he said. For example, the AHRQ suggests a structured handoff sign-out protocol dubbed ANTICipate (for Administrative data, New clinical information, Tasks to be performed, Illness severity, and Contingency plans).

Develop structured communication events specific to your hospital or department, suggested Mr. Christensen, a staff nurse at Denver Health Medical Center.

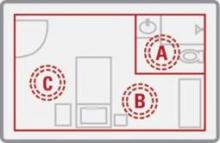

These might include a patient’s physiologic parameters that trigger an alert to the nurse and doctor, or required communication to reconcile abnormal vital signs. A "time out" at discharge will lead to safer discharge if all providers are aware of the treatment plan and pending issues are resolved. Face-to-face debriefings at shift changes are a good idea. He also recommended greater use of physician-nurse huddles to discuss significant patient issues, therapies, oxygen status and last vital signs, and any pending issues in clinical management.

"One of the things we’ve done at our institution is to institute huddles throughout the shift," he said in an interview. Every 2-3 hours the nurses and physicians round together to make sure throughout the shift that everyone is "on the same page."

At Dr. Wiler’s institution, team-based huddles are standard practice at presentation of more acute, sicker patient or trauma patients. "We’re moving to that methodology with all our patients," she said in an interview.

If you have concerns to raise with nurses, resist the temptation to direct them only to the most senior nursing staff, Mr. Christensen said. "It makes a world of difference to address a nurse by name," he added. If you don’t know a nurse’s name, ask directly, so the nurse feels included.

Taking 2 minutes to discuss the plan of care for complicated patients directly with the nurse and seek the nurse’s input will pay off in the long run, he said. With any patient, providing brief targeted bedside education for nurses by not just saying what will be done, but why, gets nurses more engaged in the clinical care team and better prepared to anticipate treatment of similar patients in the future.

Being approachable and complimenting nurses who are doing a good job also pays off, Mr. Christensen said.

"Be a leader, not a commander," he said. "Managers manage process and leaders lead people. If you want to know which you are, just look behind you. If there is no one there, you are just going for a walk."

Dr. Wiler and Mr. Christensen reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Do you speak in SBAR?

If not, communication in your department probably could be better, two speakers said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, in a session on improving teamwork.

SBAR is the acronym for a standardized communication format that organizes the transfer of information under four themes – situation, background; assessment, and recommendation. Developed by anesthesiologist Dr. Michael Leonard and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, Evergreen, the SBAR tool has been endorsed by many national organizations and medical accreditation bodies, said Dr. Jennifer L. Wiler.

It originally was used for acute-care communications from nurses to physicians but now is being used more widely for communication from nurse to nurse and from physician to physician in a variety of care settings. One study found that it was particularly useful for reporting changes in a patient’s status or a patient’s deterioration between health care services or shifts (Healthcare Quarterly 2008;11:72-9).

Using SBAR won’t necessarily save you time – at least one study suggests it increases time for communications. The limited data from seven published studies so far suggest that SBAR use improves the transfer of important information, the perception of a culture of safety, and patient satisfaction, though SBAR has yet to be validated in an emergency department setting, said Dr. Wiler of the University of Colorado, Aurora.

It has worked in hospital medicine. Hospitalists with Kaiser Permanente found SBAR to be helpful, according to a study conducted from May 2008 to August 2009. SBAR was used for end-of-rotation patient handoffs, the researchers wrote. "The Hospitalist Chief finds SBAR useful when communicating with consultants, especially during the initial telephone conversation when it is important for hospitalists to clearly state information needs." Hospitalists communicate primarily with ED physicians, and "communications with KP ED physicians is superb; [we] get a complete diagnosis" (Perm. J. 2011 Summer;15:51-60).

The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) list communication problems as the No. 1 cause of medical error, she noted. "Addressing errors related to communication is really critical," Dr. Wiler said.

To communicate in SBAR, use the following structure:

– Situation. Identify yourself, your occupation and where you are calling from, if speaking by phone. Identify the patient – the name, date of birth, age, and sex, and the reason for your report. Describe the current status of the patient or your reason for calling. If it’s urgent, say so.

– Background. Give the patient’s presenting complaint, any relevant past medical history, and a brief summary of background.

– Assessment. Describe abnormal vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, pain scale, or level of consciousness). Provide your clinical impression, the severity of the patient’s situation, and any additional concerns.

– Recommendation. Explain what you require, how urgently, and when action needs to be taken. Suggest what action might be taken. Clarify what action you expect to be taken.

One of the challenges to good communication is that physicians and nurses practice in parallel environments and too seldom prioritize teamwork, said Eric Christensen, R.N.

Beyond SBAR, a variety of strategies can improve communication between team members, he said. For example, the AHRQ suggests a structured handoff sign-out protocol dubbed ANTICipate (for Administrative data, New clinical information, Tasks to be performed, Illness severity, and Contingency plans).

Develop structured communication events specific to your hospital or department, suggested Mr. Christensen, a staff nurse at Denver Health Medical Center.

These might include a patient’s physiologic parameters that trigger an alert to the nurse and doctor, or required communication to reconcile abnormal vital signs. A "time out" at discharge will lead to safer discharge if all providers are aware of the treatment plan and pending issues are resolved. Face-to-face debriefings at shift changes are a good idea. He also recommended greater use of physician-nurse huddles to discuss significant patient issues, therapies, oxygen status and last vital signs, and any pending issues in clinical management.

"One of the things we’ve done at our institution is to institute huddles throughout the shift," he said in an interview. Every 2-3 hours the nurses and physicians round together to make sure throughout the shift that everyone is "on the same page."

At Dr. Wiler’s institution, team-based huddles are standard practice at presentation of more acute, sicker patient or trauma patients. "We’re moving to that methodology with all our patients," she said in an interview.

If you have concerns to raise with nurses, resist the temptation to direct them only to the most senior nursing staff, Mr. Christensen said. "It makes a world of difference to address a nurse by name," he added. If you don’t know a nurse’s name, ask directly, so the nurse feels included.

Taking 2 minutes to discuss the plan of care for complicated patients directly with the nurse and seek the nurse’s input will pay off in the long run, he said. With any patient, providing brief targeted bedside education for nurses by not just saying what will be done, but why, gets nurses more engaged in the clinical care team and better prepared to anticipate treatment of similar patients in the future.

Being approachable and complimenting nurses who are doing a good job also pays off, Mr. Christensen said.

"Be a leader, not a commander," he said. "Managers manage process and leaders lead people. If you want to know which you are, just look behind you. If there is no one there, you are just going for a walk."

Dr. Wiler and Mr. Christensen reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Do you speak in SBAR?

If not, communication in your department probably could be better, two speakers said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, in a session on improving teamwork.

SBAR is the acronym for a standardized communication format that organizes the transfer of information under four themes – situation, background; assessment, and recommendation. Developed by anesthesiologist Dr. Michael Leonard and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, Evergreen, the SBAR tool has been endorsed by many national organizations and medical accreditation bodies, said Dr. Jennifer L. Wiler.

It originally was used for acute-care communications from nurses to physicians but now is being used more widely for communication from nurse to nurse and from physician to physician in a variety of care settings. One study found that it was particularly useful for reporting changes in a patient’s status or a patient’s deterioration between health care services or shifts (Healthcare Quarterly 2008;11:72-9).

Using SBAR won’t necessarily save you time – at least one study suggests it increases time for communications. The limited data from seven published studies so far suggest that SBAR use improves the transfer of important information, the perception of a culture of safety, and patient satisfaction, though SBAR has yet to be validated in an emergency department setting, said Dr. Wiler of the University of Colorado, Aurora.

It has worked in hospital medicine. Hospitalists with Kaiser Permanente found SBAR to be helpful, according to a study conducted from May 2008 to August 2009. SBAR was used for end-of-rotation patient handoffs, the researchers wrote. "The Hospitalist Chief finds SBAR useful when communicating with consultants, especially during the initial telephone conversation when it is important for hospitalists to clearly state information needs." Hospitalists communicate primarily with ED physicians, and "communications with KP ED physicians is superb; [we] get a complete diagnosis" (Perm. J. 2011 Summer;15:51-60).

The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) list communication problems as the No. 1 cause of medical error, she noted. "Addressing errors related to communication is really critical," Dr. Wiler said.

To communicate in SBAR, use the following structure:

– Situation. Identify yourself, your occupation and where you are calling from, if speaking by phone. Identify the patient – the name, date of birth, age, and sex, and the reason for your report. Describe the current status of the patient or your reason for calling. If it’s urgent, say so.

– Background. Give the patient’s presenting complaint, any relevant past medical history, and a brief summary of background.

– Assessment. Describe abnormal vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, pain scale, or level of consciousness). Provide your clinical impression, the severity of the patient’s situation, and any additional concerns.

– Recommendation. Explain what you require, how urgently, and when action needs to be taken. Suggest what action might be taken. Clarify what action you expect to be taken.

One of the challenges to good communication is that physicians and nurses practice in parallel environments and too seldom prioritize teamwork, said Eric Christensen, R.N.

Beyond SBAR, a variety of strategies can improve communication between team members, he said. For example, the AHRQ suggests a structured handoff sign-out protocol dubbed ANTICipate (for Administrative data, New clinical information, Tasks to be performed, Illness severity, and Contingency plans).

Develop structured communication events specific to your hospital or department, suggested Mr. Christensen, a staff nurse at Denver Health Medical Center.

These might include a patient’s physiologic parameters that trigger an alert to the nurse and doctor, or required communication to reconcile abnormal vital signs. A "time out" at discharge will lead to safer discharge if all providers are aware of the treatment plan and pending issues are resolved. Face-to-face debriefings at shift changes are a good idea. He also recommended greater use of physician-nurse huddles to discuss significant patient issues, therapies, oxygen status and last vital signs, and any pending issues in clinical management.

"One of the things we’ve done at our institution is to institute huddles throughout the shift," he said in an interview. Every 2-3 hours the nurses and physicians round together to make sure throughout the shift that everyone is "on the same page."

At Dr. Wiler’s institution, team-based huddles are standard practice at presentation of more acute, sicker patient or trauma patients. "We’re moving to that methodology with all our patients," she said in an interview.

If you have concerns to raise with nurses, resist the temptation to direct them only to the most senior nursing staff, Mr. Christensen said. "It makes a world of difference to address a nurse by name," he added. If you don’t know a nurse’s name, ask directly, so the nurse feels included.

Taking 2 minutes to discuss the plan of care for complicated patients directly with the nurse and seek the nurse’s input will pay off in the long run, he said. With any patient, providing brief targeted bedside education for nurses by not just saying what will be done, but why, gets nurses more engaged in the clinical care team and better prepared to anticipate treatment of similar patients in the future.

Being approachable and complimenting nurses who are doing a good job also pays off, Mr. Christensen said.

"Be a leader, not a commander," he said. "Managers manage process and leaders lead people. If you want to know which you are, just look behind you. If there is no one there, you are just going for a walk."

Dr. Wiler and Mr. Christensen reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF EMERGENCY PHYSICIANS

Higher MI Mortality in Hospitalized HIV Patients

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have an acute MI are 53% more likely to die if they are infected with HIV, based on a secondary analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database.

The mortality rates for in-hospital acute MI were 4.3% for HIV-positive patients and 2.4% for HIV-negative ones, a statistically significant difference.

HIV-positive patients had a greater burden of comorbidities, as evidenced by a mean Charlson’s Comorbidity Index score of 1.14, as compared with HIV-negative patients with an average score of 0.94. Comorbidities that were significantly more prevalent in the HIV-positive cases, compared with HIV-negative cases, included renal disease (13% vs. 5%, respectively), mild liver disease (8% vs. 1%), and heart failure (26% vs. 20%), Dr. Daniel Pearce reported at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

He and his associates analyzed data from 1997 to 2006 for nearly 1.5 million adults who were hospitalized for more than a day and had an acute MI. The data approximated a stratified 20% sample of all nonfederal, short-term, general, and specialty hospitals serving adults in the United States.

The hazard ratio for death after MI was 53% higher among the 5,984 HIV-positive patients, compared with those without HIV after adjusting for the effects of age, race, gender, comorbidity, and type of insurance (as a marker for socioeconomic status), Dr. Pearce, of the Riverside County (Calif.) Department of Public Health, and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The HIV-positive group was significantly younger compared with the HIV-negative group (mean ages of 54 and 64 years, respectively), more likely to be male (65% vs. 72%), and more likely to be insured primarily by Medicare or Medicaid (62% vs. 25%).

On the other hand, the HIV-positive cases had lower rates of the most common cardiometabolic risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac arrhythmias. Substance abuse was more prevalent in the HIV-positive group than the HIV-negative group.

Dr. Pearce speculated the higher death rate could be related to the pathological effects of HIV viremia on cardiac vasculature and function.

Dr. Pearce reported having no financial disclosures.

|

|

The higher rate of in-hospital MI mortality in HIV-infected patients may be due to risk factors other than HIV infection itself. Many of these patients use illicit drugs and they’re in and out of care, disenfranchised, or don’t have access to medical care. We know that people with very limited resources don’t do as well with any diagnosed illness.

There may or may not be some truth to an underlying role of inflammation related to HIV infection in driving the higher rate of death, but we haven’t really locked that down yet, especially for early infection.

I’m not sure that these results show that HIV infection is the cause of the increased risk for fatal in-hospital acute MI. The risk may be related to HIV, but it may also be related to lifestyles and other risk factors.

Dr. Howard Edelstein is an infectious diseases specialist at Alameda County Medical Center, Oakland, Calif. He reported having no financial disclosures.

|

|

The higher rate of in-hospital MI mortality in HIV-infected patients may be due to risk factors other than HIV infection itself. Many of these patients use illicit drugs and they’re in and out of care, disenfranchised, or don’t have access to medical care. We know that people with very limited resources don’t do as well with any diagnosed illness.

There may or may not be some truth to an underlying role of inflammation related to HIV infection in driving the higher rate of death, but we haven’t really locked that down yet, especially for early infection.

I’m not sure that these results show that HIV infection is the cause of the increased risk for fatal in-hospital acute MI. The risk may be related to HIV, but it may also be related to lifestyles and other risk factors.

Dr. Howard Edelstein is an infectious diseases specialist at Alameda County Medical Center, Oakland, Calif. He reported having no financial disclosures.

|

|

The higher rate of in-hospital MI mortality in HIV-infected patients may be due to risk factors other than HIV infection itself. Many of these patients use illicit drugs and they’re in and out of care, disenfranchised, or don’t have access to medical care. We know that people with very limited resources don’t do as well with any diagnosed illness.

There may or may not be some truth to an underlying role of inflammation related to HIV infection in driving the higher rate of death, but we haven’t really locked that down yet, especially for early infection.

I’m not sure that these results show that HIV infection is the cause of the increased risk for fatal in-hospital acute MI. The risk may be related to HIV, but it may also be related to lifestyles and other risk factors.

Dr. Howard Edelstein is an infectious diseases specialist at Alameda County Medical Center, Oakland, Calif. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have an acute MI are 53% more likely to die if they are infected with HIV, based on a secondary analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database.

The mortality rates for in-hospital acute MI were 4.3% for HIV-positive patients and 2.4% for HIV-negative ones, a statistically significant difference.

HIV-positive patients had a greater burden of comorbidities, as evidenced by a mean Charlson’s Comorbidity Index score of 1.14, as compared with HIV-negative patients with an average score of 0.94. Comorbidities that were significantly more prevalent in the HIV-positive cases, compared with HIV-negative cases, included renal disease (13% vs. 5%, respectively), mild liver disease (8% vs. 1%), and heart failure (26% vs. 20%), Dr. Daniel Pearce reported at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

He and his associates analyzed data from 1997 to 2006 for nearly 1.5 million adults who were hospitalized for more than a day and had an acute MI. The data approximated a stratified 20% sample of all nonfederal, short-term, general, and specialty hospitals serving adults in the United States.

The hazard ratio for death after MI was 53% higher among the 5,984 HIV-positive patients, compared with those without HIV after adjusting for the effects of age, race, gender, comorbidity, and type of insurance (as a marker for socioeconomic status), Dr. Pearce, of the Riverside County (Calif.) Department of Public Health, and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The HIV-positive group was significantly younger compared with the HIV-negative group (mean ages of 54 and 64 years, respectively), more likely to be male (65% vs. 72%), and more likely to be insured primarily by Medicare or Medicaid (62% vs. 25%).

On the other hand, the HIV-positive cases had lower rates of the most common cardiometabolic risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac arrhythmias. Substance abuse was more prevalent in the HIV-positive group than the HIV-negative group.

Dr. Pearce speculated the higher death rate could be related to the pathological effects of HIV viremia on cardiac vasculature and function.

Dr. Pearce reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have an acute MI are 53% more likely to die if they are infected with HIV, based on a secondary analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database.

The mortality rates for in-hospital acute MI were 4.3% for HIV-positive patients and 2.4% for HIV-negative ones, a statistically significant difference.

HIV-positive patients had a greater burden of comorbidities, as evidenced by a mean Charlson’s Comorbidity Index score of 1.14, as compared with HIV-negative patients with an average score of 0.94. Comorbidities that were significantly more prevalent in the HIV-positive cases, compared with HIV-negative cases, included renal disease (13% vs. 5%, respectively), mild liver disease (8% vs. 1%), and heart failure (26% vs. 20%), Dr. Daniel Pearce reported at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

He and his associates analyzed data from 1997 to 2006 for nearly 1.5 million adults who were hospitalized for more than a day and had an acute MI. The data approximated a stratified 20% sample of all nonfederal, short-term, general, and specialty hospitals serving adults in the United States.

The hazard ratio for death after MI was 53% higher among the 5,984 HIV-positive patients, compared with those without HIV after adjusting for the effects of age, race, gender, comorbidity, and type of insurance (as a marker for socioeconomic status), Dr. Pearce, of the Riverside County (Calif.) Department of Public Health, and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The HIV-positive group was significantly younger compared with the HIV-negative group (mean ages of 54 and 64 years, respectively), more likely to be male (65% vs. 72%), and more likely to be insured primarily by Medicare or Medicaid (62% vs. 25%).

On the other hand, the HIV-positive cases had lower rates of the most common cardiometabolic risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac arrhythmias. Substance abuse was more prevalent in the HIV-positive group than the HIV-negative group.

Dr. Pearce speculated the higher death rate could be related to the pathological effects of HIV viremia on cardiac vasculature and function.

Dr. Pearce reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Major Finding: Hospitalized patients who develop acute MI are 53% more likely to die if they are HIV infected.

Data Source: Results were taken from a secondary analysis of national data on nearly 1.5 million hospitalized adults who had an in-hospital MI, 5,984 of whom had HIV.

Disclosures: Dr. Pearce reported having no financial disclosures.

Apps Proliferate Amid Concerns About Medical Use

DENVER – Do you need a stethoscope, a blood pressure monitor, or a tool to assess cardiac rhythms? There are apps for that. In fact, by recent count there are more than 200,000 applications of technology – or "apps" – available for smartphones or tablet devices, and they’re being used more and more for medical purposes.

Need a convenient way to look up drug interactions, pediatric dosing, or clinical decision rules from guidelines? Or how about a translator, a light to examine a finicky infant’s throat, or a "white board" to draw a picture for your patient? Yup – they’re all in apps, and chances are you already may be using some of these.

Dr. Joshua S. Broder expects an exponential increase in the use of apps in medicine as smartphones and tablets continue to proliferate, but their accuracy needs to be verified and potential problems need to be addressed, he said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Apps will be used increasingly for bedside diagnosis and measurement of hemoglobin or other physiologic parameters. "Some of these tests may be taken over by smartphones in the near future," according to Dr. Broder of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

On the other hand, he cautioned, how do you sterilize a smartphone as you move from one hospital room or patient to another, so that you avoid transmitting infection? There are few independent studies so far testing the accuracy and reliability of medical apps, most of which were designed for lay consumers, not physicians.

The Food and Drug Administration is "very interested" in regulating any apps that might substitute for proven technologies such as stethoscopes or that physicians use as accessories to medical devices that already are regulated, he said. The FDA described its approach to deciding which mobile technology to regulate in a draft report in July 2012.

Even the basic functions of smartphones can be convenient in clinical practice, such as taking photos or videos and transmitting information by text or e-mail, but make sure you protect patient privacy and autonomy in ways that maintain trust and comply with HIPAA, Dr. Broder said.

The Duke University Health System has resolved any issues with HIPAA so that it’s safe for physicians to transmit images and video as long as they’re not sent outside the system. Talk to the HIPAA compliance officer at your medical center to establish the ground rules, he said. You can refresh your memory about which parts of data are considered by HIPAA to be protected information via a University of Miami site.

Dr. Broder reviewed some smartphone functions and apps that may be helpful and others that are not yet ready for medical prime time. Many are available for no cost or for as nominal fee. One study of health and fitness apps suggests that apps costing $0.99 or more tend to be higher quality and more trustworthy than less-expensive ones, he noted (J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14:e72).

• Sleep: One of his residents swears by "smart alarm clock" apps that claim to use a smartphone’s accelerometer to assess where you are in your sleep cycle (based on your movements in bed) to wake you at a time that will leave you feeling less fatigued. You may set for 6 a.m., but the alarm may wake you at 5:45 a.m. Apps like Sleep Cycle ($0.99) and Sleep as Android have some underlying sleep science behind them, but no independent studies have verified their claims.

• CPR: The accelerometer also is used in the free app PocketCPR to give real-time feedback during CPR on the rate and depth of compression. Its has not been cleared by the FDA for use in humans, however, so the app warns that it’s meant for practice only. One prospective, randomized trial in 1,586 cardiac arrests that happened outside of hospitals found that use by emergency services personnel did not significantly change the likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation or other outcomes (BMJ 2011;342:d512).

• Chest: If you’re trying to teach students and residents about heart and lung sounds, or if you still get confused between mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis, you might want to have a digital stethoscope app handy. These apps interpret heart and lung sounds heard typically through your smartphone’s microphone, which may not be good enough for clinical use. The Thinklabs Stethoscope app at $70 is pricey, compared with others, but it records sounds directly via the smartphone or through an attached electronic stethoscope.

A case that turns an iPhone into an ECG device has been submitted to the FDA for approval. The AliveCor iPhone ECG is expected to sell for between $100 and $200, compared with the usual price tag of thousands of dollars for conventional ECG machines, according to PC Magazine.

One small prospective study of experimental software that programs an iPhone to detect atrial fibrillation by placing a patient’s finger over the camera lens showed it was 98% sensitive and nearly 100% specific in detecting atrial fibrillation (IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012 [doi:10.1109/TBME.2012.2208112]).

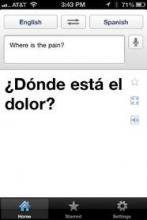

• Translation: When your hospital’s interpreter isn’t available, a free app like Google Translate can help. You can write or speak in one language and your device will write and say the message in a wide selection of language. You’ll need a wireless Internet connection for some translation apps.

Pull up an app like the free EyeChart on your smartphone or tablet.

• Light: You want to inspect a patient’s sore throat, but the light in the exam room is broken. Use the flash on your smartphone camera, or use one of many free "flashlight" apps that turn the smartphone screen into a light source. Be sure to turn it off when you’re done, though, or your battery will run down quickly.

• Ultrasound: The miniaturization of ultrasound devices continues, with systems like the Mobisante MoblUS that attaches a probe to show images on your smartphone screen.

• Skin: For better evaluation of skin lesions, turn your iPhone into a dermatoscope by using the DermScope app ($4.99) and attaching the phone to the DermScope hardware (sold separately).

• Decision support: The PediStat app ($2.99 and up) makes it easy to determine the right pediatric drug dosing, among other features. The free Calculate (Medical Calculator) by QxMD app provides quick intuitive guides to common decision rules and can be customized by medical specialty.

• Drugs: Look up drug dosing, side effects, interactions and other information on free apps from Micromedex and others.

• Photos/videos: These apps are handy for documenting and sharing the appearance of a wound, a patient’s range of motion, or performance on a neurologic exam. Anyone who thinks they see uvula deviation in the throat of a struggling 3-year-old can snap a photo or video for review with other health care providers, medical students, or parents and avoid having to repeat the exam. Images of a wound problem after surgery can be sent to the surgeon when he or she is out of town.

Dr. Broder particularly finds the video useful for children having "pseudoseizures" whose parents demand a neurologic consult, even though the seizure event probably won’t be happening when the neurologist arrives. A video shows the neurologist exactly what Dr. Broder saw. (See the Dos and Don’ts for using photos and videos on the next page.)

Once you’ve got an image or data you want to transmit, avoid texting as first-line means of communication because texts typically are not encrypted. Be careful when e-mailing to make sure it’s going to the correct address and only that address. Use e-mail options such as "confirm delivery" or "request read receipt," and add a sentence to the e-mail saying, "Please delete once no longer necessary for patient care," he advised.

Always document in the patient’s chart that you obtained patient consent and describe what was sent and who received it. Describe any images you send.

Don’t leave images on your portable devices. They’re easily lost, and most have inadequate encryption. Make images part of the medical record by uploading to the patient’s record, printing and scanning, or describing them clearly in the medical record. Then delete them from your device.

Store images and data in "cloud" computing sites with caution, Dr. Broder said. Services such as Google Drive or Dropbox allow sharing of very large files but provide no assurances about the quality of encryption or security. Cloud sites may be best used for giving patients access to instructions, instructional videos, reference papers, anatomic diagrams, etc.

The FDA approved the free Centricity Radiology Mobile Access app, which lets you view CT and MRI images on your iPhone if the images are stored in a GE Centricity PACS (picture archiving and communication system) platform – which may include 20% of U.S. radiology images, according to the company.

The free CloudOn app lets you use MS Office software (including Word, Excel, and Powerpoint) on an iPad.

Various screen replicators that allow you to remotely access your computer desktop from your mobile device (such as ones by Citrix, or Splashtop Remote Desktop) all have the same problem, Dr. Broder said – they’re too clunky and not "touchscreen friendly."

And one final word on an underappreciated perk of medical apps on smartphones: When your medical director stops by, wanting to talk about your productivity, pull out your smartphone to show the data you’ve entered about patient encounters in your free iRVU app, which calculates total RVUs, charges, and average charge per encounter, among other features.

This list only begins to scratch the surface of app use in medicine. Other apps are available for immunization schedules, dictation, infectious disease guides, and teaching aids. Journals provide content to portable devices through apps, and some medical societies offer multifaceted apps such as ACEP Mobile.

Apps on smartphones and tablets will become part of daily medical practice, Dr. Broder predicted, but physicians need to be conscious about their limitations and potential problems as well as their assets.

Dos and Don’ts for Medical Images on Smartphones

Do:

Obtain consent to acquire images or transmit them for the patient’s medical benefit.

Explain to the patient and get consent for any other intended use, such as education or publication.

Tell the patient what you will do with images when their use is completed – delete them or upload them to the medical record.

Confirm receipt if you send to other health care providers.

Specify in your message what that provider should do with the image.

Document in the patient’s chart that consent was obtained, what was sent, who received it, and content of the images.

Don’t:

Obtain images covertly.

Send to any unnecessary recipients.

Show images to anyone for fun.

Post to social media sites.

Blog about "funny" patient encounters.

Dr. Broder owns stock in Apple.

* The photo credits in this story were updated on 10/26/2012.

DENVER – Do you need a stethoscope, a blood pressure monitor, or a tool to assess cardiac rhythms? There are apps for that. In fact, by recent count there are more than 200,000 applications of technology – or "apps" – available for smartphones or tablet devices, and they’re being used more and more for medical purposes.

Need a convenient way to look up drug interactions, pediatric dosing, or clinical decision rules from guidelines? Or how about a translator, a light to examine a finicky infant’s throat, or a "white board" to draw a picture for your patient? Yup – they’re all in apps, and chances are you already may be using some of these.

Dr. Joshua S. Broder expects an exponential increase in the use of apps in medicine as smartphones and tablets continue to proliferate, but their accuracy needs to be verified and potential problems need to be addressed, he said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Apps will be used increasingly for bedside diagnosis and measurement of hemoglobin or other physiologic parameters. "Some of these tests may be taken over by smartphones in the near future," according to Dr. Broder of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

On the other hand, he cautioned, how do you sterilize a smartphone as you move from one hospital room or patient to another, so that you avoid transmitting infection? There are few independent studies so far testing the accuracy and reliability of medical apps, most of which were designed for lay consumers, not physicians.

The Food and Drug Administration is "very interested" in regulating any apps that might substitute for proven technologies such as stethoscopes or that physicians use as accessories to medical devices that already are regulated, he said. The FDA described its approach to deciding which mobile technology to regulate in a draft report in July 2012.

Even the basic functions of smartphones can be convenient in clinical practice, such as taking photos or videos and transmitting information by text or e-mail, but make sure you protect patient privacy and autonomy in ways that maintain trust and comply with HIPAA, Dr. Broder said.

The Duke University Health System has resolved any issues with HIPAA so that it’s safe for physicians to transmit images and video as long as they’re not sent outside the system. Talk to the HIPAA compliance officer at your medical center to establish the ground rules, he said. You can refresh your memory about which parts of data are considered by HIPAA to be protected information via a University of Miami site.

Dr. Broder reviewed some smartphone functions and apps that may be helpful and others that are not yet ready for medical prime time. Many are available for no cost or for as nominal fee. One study of health and fitness apps suggests that apps costing $0.99 or more tend to be higher quality and more trustworthy than less-expensive ones, he noted (J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14:e72).

• Sleep: One of his residents swears by "smart alarm clock" apps that claim to use a smartphone’s accelerometer to assess where you are in your sleep cycle (based on your movements in bed) to wake you at a time that will leave you feeling less fatigued. You may set for 6 a.m., but the alarm may wake you at 5:45 a.m. Apps like Sleep Cycle ($0.99) and Sleep as Android have some underlying sleep science behind them, but no independent studies have verified their claims.

• CPR: The accelerometer also is used in the free app PocketCPR to give real-time feedback during CPR on the rate and depth of compression. Its has not been cleared by the FDA for use in humans, however, so the app warns that it’s meant for practice only. One prospective, randomized trial in 1,586 cardiac arrests that happened outside of hospitals found that use by emergency services personnel did not significantly change the likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation or other outcomes (BMJ 2011;342:d512).

• Chest: If you’re trying to teach students and residents about heart and lung sounds, or if you still get confused between mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis, you might want to have a digital stethoscope app handy. These apps interpret heart and lung sounds heard typically through your smartphone’s microphone, which may not be good enough for clinical use. The Thinklabs Stethoscope app at $70 is pricey, compared with others, but it records sounds directly via the smartphone or through an attached electronic stethoscope.

A case that turns an iPhone into an ECG device has been submitted to the FDA for approval. The AliveCor iPhone ECG is expected to sell for between $100 and $200, compared with the usual price tag of thousands of dollars for conventional ECG machines, according to PC Magazine.

One small prospective study of experimental software that programs an iPhone to detect atrial fibrillation by placing a patient’s finger over the camera lens showed it was 98% sensitive and nearly 100% specific in detecting atrial fibrillation (IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012 [doi:10.1109/TBME.2012.2208112]).

• Translation: When your hospital’s interpreter isn’t available, a free app like Google Translate can help. You can write or speak in one language and your device will write and say the message in a wide selection of language. You’ll need a wireless Internet connection for some translation apps.

Pull up an app like the free EyeChart on your smartphone or tablet.

• Light: You want to inspect a patient’s sore throat, but the light in the exam room is broken. Use the flash on your smartphone camera, or use one of many free "flashlight" apps that turn the smartphone screen into a light source. Be sure to turn it off when you’re done, though, or your battery will run down quickly.

• Ultrasound: The miniaturization of ultrasound devices continues, with systems like the Mobisante MoblUS that attaches a probe to show images on your smartphone screen.

• Skin: For better evaluation of skin lesions, turn your iPhone into a dermatoscope by using the DermScope app ($4.99) and attaching the phone to the DermScope hardware (sold separately).

• Decision support: The PediStat app ($2.99 and up) makes it easy to determine the right pediatric drug dosing, among other features. The free Calculate (Medical Calculator) by QxMD app provides quick intuitive guides to common decision rules and can be customized by medical specialty.

• Drugs: Look up drug dosing, side effects, interactions and other information on free apps from Micromedex and others.

• Photos/videos: These apps are handy for documenting and sharing the appearance of a wound, a patient’s range of motion, or performance on a neurologic exam. Anyone who thinks they see uvula deviation in the throat of a struggling 3-year-old can snap a photo or video for review with other health care providers, medical students, or parents and avoid having to repeat the exam. Images of a wound problem after surgery can be sent to the surgeon when he or she is out of town.

Dr. Broder particularly finds the video useful for children having "pseudoseizures" whose parents demand a neurologic consult, even though the seizure event probably won’t be happening when the neurologist arrives. A video shows the neurologist exactly what Dr. Broder saw. (See the Dos and Don’ts for using photos and videos on the next page.)

Once you’ve got an image or data you want to transmit, avoid texting as first-line means of communication because texts typically are not encrypted. Be careful when e-mailing to make sure it’s going to the correct address and only that address. Use e-mail options such as "confirm delivery" or "request read receipt," and add a sentence to the e-mail saying, "Please delete once no longer necessary for patient care," he advised.

Always document in the patient’s chart that you obtained patient consent and describe what was sent and who received it. Describe any images you send.

Don’t leave images on your portable devices. They’re easily lost, and most have inadequate encryption. Make images part of the medical record by uploading to the patient’s record, printing and scanning, or describing them clearly in the medical record. Then delete them from your device.

Store images and data in "cloud" computing sites with caution, Dr. Broder said. Services such as Google Drive or Dropbox allow sharing of very large files but provide no assurances about the quality of encryption or security. Cloud sites may be best used for giving patients access to instructions, instructional videos, reference papers, anatomic diagrams, etc.

The FDA approved the free Centricity Radiology Mobile Access app, which lets you view CT and MRI images on your iPhone if the images are stored in a GE Centricity PACS (picture archiving and communication system) platform – which may include 20% of U.S. radiology images, according to the company.

The free CloudOn app lets you use MS Office software (including Word, Excel, and Powerpoint) on an iPad.

Various screen replicators that allow you to remotely access your computer desktop from your mobile device (such as ones by Citrix, or Splashtop Remote Desktop) all have the same problem, Dr. Broder said – they’re too clunky and not "touchscreen friendly."

And one final word on an underappreciated perk of medical apps on smartphones: When your medical director stops by, wanting to talk about your productivity, pull out your smartphone to show the data you’ve entered about patient encounters in your free iRVU app, which calculates total RVUs, charges, and average charge per encounter, among other features.

This list only begins to scratch the surface of app use in medicine. Other apps are available for immunization schedules, dictation, infectious disease guides, and teaching aids. Journals provide content to portable devices through apps, and some medical societies offer multifaceted apps such as ACEP Mobile.

Apps on smartphones and tablets will become part of daily medical practice, Dr. Broder predicted, but physicians need to be conscious about their limitations and potential problems as well as their assets.

Dos and Don’ts for Medical Images on Smartphones

Do:

Obtain consent to acquire images or transmit them for the patient’s medical benefit.

Explain to the patient and get consent for any other intended use, such as education or publication.

Tell the patient what you will do with images when their use is completed – delete them or upload them to the medical record.

Confirm receipt if you send to other health care providers.

Specify in your message what that provider should do with the image.

Document in the patient’s chart that consent was obtained, what was sent, who received it, and content of the images.

Don’t:

Obtain images covertly.

Send to any unnecessary recipients.

Show images to anyone for fun.

Post to social media sites.

Blog about "funny" patient encounters.

Dr. Broder owns stock in Apple.

* The photo credits in this story were updated on 10/26/2012.

DENVER – Do you need a stethoscope, a blood pressure monitor, or a tool to assess cardiac rhythms? There are apps for that. In fact, by recent count there are more than 200,000 applications of technology – or "apps" – available for smartphones or tablet devices, and they’re being used more and more for medical purposes.

Need a convenient way to look up drug interactions, pediatric dosing, or clinical decision rules from guidelines? Or how about a translator, a light to examine a finicky infant’s throat, or a "white board" to draw a picture for your patient? Yup – they’re all in apps, and chances are you already may be using some of these.

Dr. Joshua S. Broder expects an exponential increase in the use of apps in medicine as smartphones and tablets continue to proliferate, but their accuracy needs to be verified and potential problems need to be addressed, he said at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Apps will be used increasingly for bedside diagnosis and measurement of hemoglobin or other physiologic parameters. "Some of these tests may be taken over by smartphones in the near future," according to Dr. Broder of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

On the other hand, he cautioned, how do you sterilize a smartphone as you move from one hospital room or patient to another, so that you avoid transmitting infection? There are few independent studies so far testing the accuracy and reliability of medical apps, most of which were designed for lay consumers, not physicians.

The Food and Drug Administration is "very interested" in regulating any apps that might substitute for proven technologies such as stethoscopes or that physicians use as accessories to medical devices that already are regulated, he said. The FDA described its approach to deciding which mobile technology to regulate in a draft report in July 2012.

Even the basic functions of smartphones can be convenient in clinical practice, such as taking photos or videos and transmitting information by text or e-mail, but make sure you protect patient privacy and autonomy in ways that maintain trust and comply with HIPAA, Dr. Broder said.

The Duke University Health System has resolved any issues with HIPAA so that it’s safe for physicians to transmit images and video as long as they’re not sent outside the system. Talk to the HIPAA compliance officer at your medical center to establish the ground rules, he said. You can refresh your memory about which parts of data are considered by HIPAA to be protected information via a University of Miami site.

Dr. Broder reviewed some smartphone functions and apps that may be helpful and others that are not yet ready for medical prime time. Many are available for no cost or for as nominal fee. One study of health and fitness apps suggests that apps costing $0.99 or more tend to be higher quality and more trustworthy than less-expensive ones, he noted (J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14:e72).

• Sleep: One of his residents swears by "smart alarm clock" apps that claim to use a smartphone’s accelerometer to assess where you are in your sleep cycle (based on your movements in bed) to wake you at a time that will leave you feeling less fatigued. You may set for 6 a.m., but the alarm may wake you at 5:45 a.m. Apps like Sleep Cycle ($0.99) and Sleep as Android have some underlying sleep science behind them, but no independent studies have verified their claims.

• CPR: The accelerometer also is used in the free app PocketCPR to give real-time feedback during CPR on the rate and depth of compression. Its has not been cleared by the FDA for use in humans, however, so the app warns that it’s meant for practice only. One prospective, randomized trial in 1,586 cardiac arrests that happened outside of hospitals found that use by emergency services personnel did not significantly change the likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation or other outcomes (BMJ 2011;342:d512).

• Chest: If you’re trying to teach students and residents about heart and lung sounds, or if you still get confused between mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis, you might want to have a digital stethoscope app handy. These apps interpret heart and lung sounds heard typically through your smartphone’s microphone, which may not be good enough for clinical use. The Thinklabs Stethoscope app at $70 is pricey, compared with others, but it records sounds directly via the smartphone or through an attached electronic stethoscope.

A case that turns an iPhone into an ECG device has been submitted to the FDA for approval. The AliveCor iPhone ECG is expected to sell for between $100 and $200, compared with the usual price tag of thousands of dollars for conventional ECG machines, according to PC Magazine.

One small prospective study of experimental software that programs an iPhone to detect atrial fibrillation by placing a patient’s finger over the camera lens showed it was 98% sensitive and nearly 100% specific in detecting atrial fibrillation (IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012 [doi:10.1109/TBME.2012.2208112]).

• Translation: When your hospital’s interpreter isn’t available, a free app like Google Translate can help. You can write or speak in one language and your device will write and say the message in a wide selection of language. You’ll need a wireless Internet connection for some translation apps.

Pull up an app like the free EyeChart on your smartphone or tablet.

• Light: You want to inspect a patient’s sore throat, but the light in the exam room is broken. Use the flash on your smartphone camera, or use one of many free "flashlight" apps that turn the smartphone screen into a light source. Be sure to turn it off when you’re done, though, or your battery will run down quickly.

• Ultrasound: The miniaturization of ultrasound devices continues, with systems like the Mobisante MoblUS that attaches a probe to show images on your smartphone screen.

• Skin: For better evaluation of skin lesions, turn your iPhone into a dermatoscope by using the DermScope app ($4.99) and attaching the phone to the DermScope hardware (sold separately).

• Decision support: The PediStat app ($2.99 and up) makes it easy to determine the right pediatric drug dosing, among other features. The free Calculate (Medical Calculator) by QxMD app provides quick intuitive guides to common decision rules and can be customized by medical specialty.

• Drugs: Look up drug dosing, side effects, interactions and other information on free apps from Micromedex and others.

• Photos/videos: These apps are handy for documenting and sharing the appearance of a wound, a patient’s range of motion, or performance on a neurologic exam. Anyone who thinks they see uvula deviation in the throat of a struggling 3-year-old can snap a photo or video for review with other health care providers, medical students, or parents and avoid having to repeat the exam. Images of a wound problem after surgery can be sent to the surgeon when he or she is out of town.

Dr. Broder particularly finds the video useful for children having "pseudoseizures" whose parents demand a neurologic consult, even though the seizure event probably won’t be happening when the neurologist arrives. A video shows the neurologist exactly what Dr. Broder saw. (See the Dos and Don’ts for using photos and videos on the next page.)

Once you’ve got an image or data you want to transmit, avoid texting as first-line means of communication because texts typically are not encrypted. Be careful when e-mailing to make sure it’s going to the correct address and only that address. Use e-mail options such as "confirm delivery" or "request read receipt," and add a sentence to the e-mail saying, "Please delete once no longer necessary for patient care," he advised.

Always document in the patient’s chart that you obtained patient consent and describe what was sent and who received it. Describe any images you send.

Don’t leave images on your portable devices. They’re easily lost, and most have inadequate encryption. Make images part of the medical record by uploading to the patient’s record, printing and scanning, or describing them clearly in the medical record. Then delete them from your device.

Store images and data in "cloud" computing sites with caution, Dr. Broder said. Services such as Google Drive or Dropbox allow sharing of very large files but provide no assurances about the quality of encryption or security. Cloud sites may be best used for giving patients access to instructions, instructional videos, reference papers, anatomic diagrams, etc.

The FDA approved the free Centricity Radiology Mobile Access app, which lets you view CT and MRI images on your iPhone if the images are stored in a GE Centricity PACS (picture archiving and communication system) platform – which may include 20% of U.S. radiology images, according to the company.

The free CloudOn app lets you use MS Office software (including Word, Excel, and Powerpoint) on an iPad.

Various screen replicators that allow you to remotely access your computer desktop from your mobile device (such as ones by Citrix, or Splashtop Remote Desktop) all have the same problem, Dr. Broder said – they’re too clunky and not "touchscreen friendly."

And one final word on an underappreciated perk of medical apps on smartphones: When your medical director stops by, wanting to talk about your productivity, pull out your smartphone to show the data you’ve entered about patient encounters in your free iRVU app, which calculates total RVUs, charges, and average charge per encounter, among other features.

This list only begins to scratch the surface of app use in medicine. Other apps are available for immunization schedules, dictation, infectious disease guides, and teaching aids. Journals provide content to portable devices through apps, and some medical societies offer multifaceted apps such as ACEP Mobile.

Apps on smartphones and tablets will become part of daily medical practice, Dr. Broder predicted, but physicians need to be conscious about their limitations and potential problems as well as their assets.

Dos and Don’ts for Medical Images on Smartphones

Do:

Obtain consent to acquire images or transmit them for the patient’s medical benefit.

Explain to the patient and get consent for any other intended use, such as education or publication.

Tell the patient what you will do with images when their use is completed – delete them or upload them to the medical record.

Confirm receipt if you send to other health care providers.

Specify in your message what that provider should do with the image.

Document in the patient’s chart that consent was obtained, what was sent, who received it, and content of the images.

Don’t:

Obtain images covertly.

Send to any unnecessary recipients.

Show images to anyone for fun.

Post to social media sites.

Blog about "funny" patient encounters.

Dr. Broder owns stock in Apple.

* The photo credits in this story were updated on 10/26/2012.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF EMERGENCY PHYSICIANS

Bedside Tools to ID Severe C. difficile Fall Short

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

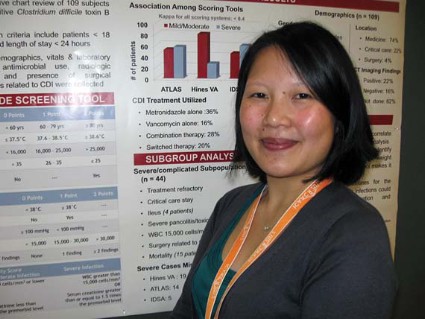

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer severity criteria, but these require the observation of clinical end points and thus are ineffective for assessing patients at initial presentation, she said in a poster presentation at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

The Hines VA scoring system, in addition to missing the most severe cases, also gives a great deal of weight to diagnostic imaging, which "makes it impractical at our institution," she said. The Hines VA tool incorporates temperature, the presence of ileus, systolic blood pressure, leukocytosis, and abnormal CT findings to stratify patients by severity.

"We’re going to continue relying on the clinician’s assessment at the bedside at the time of diagnosis to evaluate whether cases are severe or not severe, and not use any of these tools that are available," Dr. Doan said.

A good bedside tool sure would be nice, though, to have a good, objective way of identifying severe C. difficile infection, she added. In a large health system, order sets could be developed based on the tool’s findings "so that everybody would be on the same page in terms of treatment," she said. None of the current tools are good enough for that.

Severe cases of C. difficile are on the rise because of increasing prevalence of the hypervirulent NAP1/BI/027 strain, she noted.

A number of clinicians at the meeting approached her with their own versions of bedside tools for identifying severe C. difficile infection, which Dr. Doan and her associates may evaluate next. They also may compare the tools on different subpopulations of patients with severe infection, such as only patients whose death or surgery was related to C. difficile infection.

Dr. Doan reported having no financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer severity criteria, but these require the observation of clinical end points and thus are ineffective for assessing patients at initial presentation, she said in a poster presentation at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

The Hines VA scoring system, in addition to missing the most severe cases, also gives a great deal of weight to diagnostic imaging, which "makes it impractical at our institution," she said. The Hines VA tool incorporates temperature, the presence of ileus, systolic blood pressure, leukocytosis, and abnormal CT findings to stratify patients by severity.

"We’re going to continue relying on the clinician’s assessment at the bedside at the time of diagnosis to evaluate whether cases are severe or not severe, and not use any of these tools that are available," Dr. Doan said.

A good bedside tool sure would be nice, though, to have a good, objective way of identifying severe C. difficile infection, she added. In a large health system, order sets could be developed based on the tool’s findings "so that everybody would be on the same page in terms of treatment," she said. None of the current tools are good enough for that.

Severe cases of C. difficile are on the rise because of increasing prevalence of the hypervirulent NAP1/BI/027 strain, she noted.

A number of clinicians at the meeting approached her with their own versions of bedside tools for identifying severe C. difficile infection, which Dr. Doan and her associates may evaluate next. They also may compare the tools on different subpopulations of patients with severe infection, such as only patients whose death or surgery was related to C. difficile infection.

Dr. Doan reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.