User login

Decreasing Chemotherapy Administration Wait Time for Veterans with Cancer: A Minneapolis VA Medical Center Quality Improvement Project

Background: Cancer diagnosis is a devastating and painful process for patients and their families, resulting in significant stress and uncertainty. Chemotherapy treatments may provide a cure, control or palliate symptoms caused by cancer. However, delivery of chemotherapy in outpatient clinics is challenging and timeconsuming. Long wait is a common patient complaint, affects work-flow and chair time usage, increases costs, and compromises safety. We sought to review our system and implement changes that may result in decrease wait time.

Methods: Utilizing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) model, the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) method to test and implement changes, we established a preintervention Ishikawa diagram over a 4 weeks period to study the process and determine cause of delay. Changes were implemented in a stepwise fashion, assess for improvement and revised our process over another 4 week period. We collect and analyze data for a total of 2 months. The objective of the study was to decrease wait-time to initiate chemotherapy treatment from the end of clinic visit to start of chemotherapy infusion by 20-30 minutes for 50% of patients in the oncology clinic over a three-month period.

Results: Pre-intervention data was collected on 245 patients. 55% (n=136) of these patients waited an average of 90 minutes and 45% (n=110) waited an average of 42 minutes from check-in to infusion clinic to start of chemotherapy. Identified barriers causing delayed chemotherapy administration included no consent, no prior authorization, unwritten/unsigned orders, pharmacy release delay, incomplete required labs, delay drug delivery from pharmacy, and difficulty with IV access. After the first cycle of PDSA, post-intervention data reveal a small improvement. 52% (n=199) patients waited an average of 87 minutes and 48% (n=183) average wait was 41 minutes.

Conclusions: By utilizing the PDSA cycle to test the modification of the revised workflow system and eliminate barriers to release of chemotherapy we could potentially reduce wait times for patient receiving chemotherapy at the Minneapolis VA. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO Annual Meeting.

Background: Cancer diagnosis is a devastating and painful process for patients and their families, resulting in significant stress and uncertainty. Chemotherapy treatments may provide a cure, control or palliate symptoms caused by cancer. However, delivery of chemotherapy in outpatient clinics is challenging and timeconsuming. Long wait is a common patient complaint, affects work-flow and chair time usage, increases costs, and compromises safety. We sought to review our system and implement changes that may result in decrease wait time.

Methods: Utilizing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) model, the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) method to test and implement changes, we established a preintervention Ishikawa diagram over a 4 weeks period to study the process and determine cause of delay. Changes were implemented in a stepwise fashion, assess for improvement and revised our process over another 4 week period. We collect and analyze data for a total of 2 months. The objective of the study was to decrease wait-time to initiate chemotherapy treatment from the end of clinic visit to start of chemotherapy infusion by 20-30 minutes for 50% of patients in the oncology clinic over a three-month period.

Results: Pre-intervention data was collected on 245 patients. 55% (n=136) of these patients waited an average of 90 minutes and 45% (n=110) waited an average of 42 minutes from check-in to infusion clinic to start of chemotherapy. Identified barriers causing delayed chemotherapy administration included no consent, no prior authorization, unwritten/unsigned orders, pharmacy release delay, incomplete required labs, delay drug delivery from pharmacy, and difficulty with IV access. After the first cycle of PDSA, post-intervention data reveal a small improvement. 52% (n=199) patients waited an average of 87 minutes and 48% (n=183) average wait was 41 minutes.

Conclusions: By utilizing the PDSA cycle to test the modification of the revised workflow system and eliminate barriers to release of chemotherapy we could potentially reduce wait times for patient receiving chemotherapy at the Minneapolis VA. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO Annual Meeting.

Background: Cancer diagnosis is a devastating and painful process for patients and their families, resulting in significant stress and uncertainty. Chemotherapy treatments may provide a cure, control or palliate symptoms caused by cancer. However, delivery of chemotherapy in outpatient clinics is challenging and timeconsuming. Long wait is a common patient complaint, affects work-flow and chair time usage, increases costs, and compromises safety. We sought to review our system and implement changes that may result in decrease wait time.

Methods: Utilizing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) model, the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) method to test and implement changes, we established a preintervention Ishikawa diagram over a 4 weeks period to study the process and determine cause of delay. Changes were implemented in a stepwise fashion, assess for improvement and revised our process over another 4 week period. We collect and analyze data for a total of 2 months. The objective of the study was to decrease wait-time to initiate chemotherapy treatment from the end of clinic visit to start of chemotherapy infusion by 20-30 minutes for 50% of patients in the oncology clinic over a three-month period.

Results: Pre-intervention data was collected on 245 patients. 55% (n=136) of these patients waited an average of 90 minutes and 45% (n=110) waited an average of 42 minutes from check-in to infusion clinic to start of chemotherapy. Identified barriers causing delayed chemotherapy administration included no consent, no prior authorization, unwritten/unsigned orders, pharmacy release delay, incomplete required labs, delay drug delivery from pharmacy, and difficulty with IV access. After the first cycle of PDSA, post-intervention data reveal a small improvement. 52% (n=199) patients waited an average of 87 minutes and 48% (n=183) average wait was 41 minutes.

Conclusions: By utilizing the PDSA cycle to test the modification of the revised workflow system and eliminate barriers to release of chemotherapy we could potentially reduce wait times for patient receiving chemotherapy at the Minneapolis VA. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO Annual Meeting.

Use of Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms in Patients With Advanced Cancer

Purpose/Rationale: Our Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) team developed a self-management symptom program using the existing Annie Mobile Messaging System platform that was designed to be userfriendly for Veterans. We are currently determining which patients with advanced cancer might benefit most from the system. Here we describe early results from this program.

Background: Symptom monitoring programs using electronic communications platforms in patients with advanced solid tumors undergoing routine outpatient chemotherapy has resulted in benefits such as improved quality of life, improved survival, and reduced Emergency Room (ER) usage.

Methods: We created a symptom management protocol in conjunction with the Annie Program Team. Patients are sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and they are asked to rate the following symptoms with a severity scale of 0-4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): Nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue, trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea, numbness/tingling, and pain. In addition, patients are asked whether they have had a fever or not. Based on the patient response, the patient receives an automated, corresponding text back. The text may provide positive affirmation that they are doing well, give them education, refer them to an educational hyperlink, ask them to call a direct number to the clinic, or report directly to the ER.

Results: We have currently enrolled 5 patients in the program through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education. There have not been any calls to the clinic or visits to the ER to date. Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges and patients have been very positive about the program, including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and utilization of the texting advice.

Conclusions: Development and introduction of the MVAHCS Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms has been completed. Early evaluation has not revealed any major concerns. We will continue to introduce this technology to patients undergoing chemotherapy and will further assess the feasibility and efficacy of this novel VA program.

Purpose/Rationale: Our Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) team developed a self-management symptom program using the existing Annie Mobile Messaging System platform that was designed to be userfriendly for Veterans. We are currently determining which patients with advanced cancer might benefit most from the system. Here we describe early results from this program.

Background: Symptom monitoring programs using electronic communications platforms in patients with advanced solid tumors undergoing routine outpatient chemotherapy has resulted in benefits such as improved quality of life, improved survival, and reduced Emergency Room (ER) usage.

Methods: We created a symptom management protocol in conjunction with the Annie Program Team. Patients are sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and they are asked to rate the following symptoms with a severity scale of 0-4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): Nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue, trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea, numbness/tingling, and pain. In addition, patients are asked whether they have had a fever or not. Based on the patient response, the patient receives an automated, corresponding text back. The text may provide positive affirmation that they are doing well, give them education, refer them to an educational hyperlink, ask them to call a direct number to the clinic, or report directly to the ER.

Results: We have currently enrolled 5 patients in the program through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education. There have not been any calls to the clinic or visits to the ER to date. Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges and patients have been very positive about the program, including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and utilization of the texting advice.

Conclusions: Development and introduction of the MVAHCS Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms has been completed. Early evaluation has not revealed any major concerns. We will continue to introduce this technology to patients undergoing chemotherapy and will further assess the feasibility and efficacy of this novel VA program.

Purpose/Rationale: Our Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) team developed a self-management symptom program using the existing Annie Mobile Messaging System platform that was designed to be userfriendly for Veterans. We are currently determining which patients with advanced cancer might benefit most from the system. Here we describe early results from this program.

Background: Symptom monitoring programs using electronic communications platforms in patients with advanced solid tumors undergoing routine outpatient chemotherapy has resulted in benefits such as improved quality of life, improved survival, and reduced Emergency Room (ER) usage.

Methods: We created a symptom management protocol in conjunction with the Annie Program Team. Patients are sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and they are asked to rate the following symptoms with a severity scale of 0-4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): Nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue, trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea, numbness/tingling, and pain. In addition, patients are asked whether they have had a fever or not. Based on the patient response, the patient receives an automated, corresponding text back. The text may provide positive affirmation that they are doing well, give them education, refer them to an educational hyperlink, ask them to call a direct number to the clinic, or report directly to the ER.

Results: We have currently enrolled 5 patients in the program through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education. There have not been any calls to the clinic or visits to the ER to date. Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges and patients have been very positive about the program, including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and utilization of the texting advice.

Conclusions: Development and introduction of the MVAHCS Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms has been completed. Early evaluation has not revealed any major concerns. We will continue to introduce this technology to patients undergoing chemotherapy and will further assess the feasibility and efficacy of this novel VA program.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Disclosure Policy Fails to Accurately Inform Its Members of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The relationship and collaboration between orthopedic surgeons and the orthopedic industry are considerable. Orthopedic surgeons can provide companies with important clinical input into the design of implants, facilitate commercialization of innovations developed by clinician entrepreneurs, and help provide rapid dissemination of new technologies.1,2 However, these relationships can result in conflicts of interest, thereby influencing the physicians’ judgment and choices and ultimately patient care.3,4 Making these potential conflicts transparent through physician disclosures is an accepted way to limit the negative effects of these relationships.5 The relationship between orthopedic surgeons and industry was brought to the forefront in 2007 with a settlement between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the 5 largest orthopedic implant makers.6 Among other things, this settlement required that each company publicly disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of all surgeons and organizations it paid, and how much. The DOJ settlement was one of the impetuses that led many orthopedic societies to adopt either voluntary or mandatory disclosure policies for their members.

In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an orthopedic disclosure program to promote transparency and confidence in its educational programs and decisions.7 One of the 2 main purposes of the disclosure program is “streamlining the disclosure process for orthopedic surgeons and others involved in organizational governance, all formats of continuing medical education [CME] and authors of enduring materials, clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and appropriate use criteria (AUC) development and editors-in-chief and editorial boards, from whom disclosure is required.”8 Disclosure is mandatory only for participants in the AAOS CME programs (including any podium or poster presentation) or authors of enduring materials; members of the AAOS Board of Directors, Board of Councilors, Board of Specialty Societies, councils, cabinets, committees, project teams, or other AAOS governance groups; editors-in-chief and editorial boards; and AAOS guideline development workgroups. Members who fail to disclose are informed they cannot participate in AAOS activities. All other members of the organization are not required to disclose any industry-related relationships, and any disclosure is completely voluntary.7 This seems contrary to the second main goal of the disclosure policy: “increase transparency throughout AAOS by making this disclosure program available to the public and to AAOS members.”8

We conducted a study to compare the disclosures posted by the top orthopedic companies with the disclosures made by their surgeon-consultants and to determine how many of these surgeons have disclosed this information on the AAOS website.

Materials and Methods

On November 26, 2012, we reviewed the websites of the top 13 orthopedic device companies by revenue (Stryker, DePuy Orthopaedics, Zimmer Holdings, Smith & Nephew, Synthes, Medtronic Spine, Biomet, DJO Global, Orthofix, NuVasive, Wright Medical Group, ArthroCare, Exactech)9 to identify their surgeon-consultants for 2011. We excluded non-US surgeons (DOJ disclosure not required), revenues under $1000, and reimbursement for meals and travel. Although the DOJ settlement required that each company disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of its paid consultants and the amounts paid, the settlement did not stipulate how long this must be continued. Of the 13 companies, only 6 (Stryker, DePuy, Smith & Nephew, Medtronic, Wright, Exactech) continued listing and updating surgeon disclosure information.

As the companies differed in how they defined surgeon consulting services, we defined surgeon-consultant payments as the sum of consulting payments, royalty payments, and research support. We searched for each surgeon-consultant’s name in the AAOS orthopedic disclosure program database.7 From the database, we determined whether the surgeon was a member of AAOS. All members were then categorized into those who disclosed all their payments, those who incompletely disclosed their payments, those who did not disclose any payments, and those who did not provide any information. They were then subdivided into those who had and had not participated in CME activities at the AAOS annual meeting in 2011 (participants were listed in the meeting proceedings). This does not take into account AAOS members who presented at other AAOS-sponsored CME courses during 2011 and who therefore were required to disclose. The information was categorized by company, payment amount, and overall. To simplify matters and deal with varying corporate categories, we divided payments into 4 amount groups: less than $10,000, $10,000 to $100,000, $100,001 to $1 million, and more than $1 million. Some orthopedic companies reported surgeon payments as categorical rather than exact amounts. In these cases, we coded the payment as the midpoint of the range.

Results

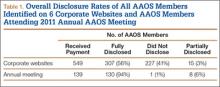

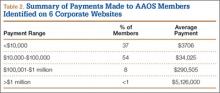

Overall, 549 AAOS members received payments of more than $1000 from at least 1 of the 6 companies. Of these surgeons, 307 (56%) fully disclosed their payments, and 242 (44%) did not (Table 1). Of the 32 surgeons who were on 2 corporate payment lists, 24 disclosed both companies, 6 disclosed only 1 company, and 2 failed to disclose either company. AAOS members who did not disclose payments received less than $10,000 (average, $3706) in 37% of cases (Table 2), between $10,000 and $100,000 (average, $34,025) in 54% of cases, between $100,001 and $1 million (average, $290,505) in 8% of cases, and more than $1 million (average, $5,126,000) in less than 1% of cases.

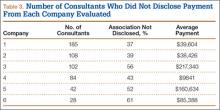

Number of consultants, number of surgeons not disclosing payments, and value of these payments varied from company to company (Table 3). The company with the most consultants listed 185 AAOS members, of which 37% had not disclosed payments (average, $39,604). Second was the company that listed 108 members; 39% had not disclosed payments (average, $38,426). The third company listed 102 members, of which 56% had not disclosed payments (average, $217,340). The company with the fourth most consultants listed 84 members; 43% had not disclosed payments (average, $9841). Next to last was the company listing 42 members, of which 52% had not disclosed payments (average, $160,634). The company with the fewest consultants listed 28 members; 61% had not disclosed payments (average $85,388).

Of AAOS members who attended the 2011 annual meeting, 94% fully disclosed industry payments (Table 1). Only 7% of the membership either failed to disclose or incompletely disclosed this relationship. In 36 cases (26%), members disclosed a financial relationship with at least 1 orthopedic company, but this relationship was not listed on the company’s website. One of the companies was responsible for 47% of the underreporting.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether surgeons fully disclosed (on the website for the AAOS disclosure program) payments they received from orthopedic companies. Overall compliance was poor, with 44% of surgeons not disclosing payments. The percentage of surgeons disclosing corporate relationships and payments received varied among orthopedic companies. It is unclear whether this reflects partial reporting, or AAOS disclosure policy being mandatory only for select members rather than the entire membership.

This study had a few limitations, none of which had a substantive impact on the results or conclusions. First, we could not determine how many AAOS members who were required to disclose actually disclosed. There is no mechanism for determining which members are involved in activities that require disclosure. Nonetheless, the intent of the policy is to make collaborations between orthopedic surgeons and industry transparent in order to address concerns about potential conflicts of interest. That 44% of AAOS members did not disclose their relationships cannot be considered a success. Second, information was available on the websites of only 6 of the top 15 orthopedic companies—a result stemming from the DOJ’s failure to specify how long these companies must continue posting disclosures. In this study, the lowest nondisclosure rate was 37%, and there is no reason to suspect that any other group of surgeon-consultants would be any more compliant with AAOS’s policy.

There are few reports on the effects of the DOJ settlement on the behavior of surgeon-consultants who are AAOS members. Hockenberry and colleagues10 found that, since the settlement, surgeon payments have increased, number of consultants has decreased, and the proportion of consultants from academia has increased. They thought their findings confirmed concerns that orthopedic device makers would deliberately select high-volume orthopedic surgeons as consultants in order to increase sales of their implants and gain market share at the expense of their competitors. The authors thought that AAOS had some power to address disclosure through its influence on its members, but that influence may not be enough. Jegede and colleagues11 found that a significant percentage (41%) of orthopedic surgeons who received corporate payments and presented at the AAOS annual meeting were inconsistent in submitting disclosure information. Results of the present study suggest that AAOS policy is weak and does not adequately address the issue and provide full transparency, either within the organization or to the public, of all its members’ industry relationships.

As the preeminent provider of musculoskeletal education to orthopedic surgeons and others, and with a membership totaling almost 39,000, AAOS is one of the most important orthopedic societies in the world. AAOS has clearly stated that one of its goals is to increase transparency by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. However, it can be completely transparent only if all its members are required to disclose their corporate relationships. This study demonstrated that AAOS’s policy of mandatory disclosure for select members and voluntary disclosure for all other members is ineffective. We found that 44% of members failed to disclose industry-derived payments. This inadequate level of compliance runs contrary to the AAOS goal of increasing transparency of surgeon–industry consulting by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. The AAOS disclosure program and the potential consequences of noncompliance need to be reevaluated by the organization if it wants its program to succeed.

1. Crowninshield RD, Callaghan JJ. The orthopaedic profession and the industry partnership. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(457):73-77.

2. White AP, Vaccaro AR, Zdeblick T. Counterpoint: physician–industry relationships can be ethically established, and conflicts of interest can be ethically managed. Spine. 2007;32(11 suppl):S53-S57.

3. Steinbrook R. Online disclosure of physician–industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):325-327.

4. Steinbrook R. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):559-561.

5. Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Dinan MA, et al. Disclosing conflicts of interest in clinical research: views of institutional review boards, conflict of interest committees, and investigators. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(3):581-591, 481.

6. US Attorney’s Office, District of New Jersey. Monitoring and deferred prosecution agreements terminated with companies in hip and knee replacement industry [press release]. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Newark Division website. http://www.fbi.gov/newark/press-releases/2009/nk033009a.htm. March 30, 2009. Accessed May 13, 2015.

7. AAOS mandatory disclosure policy. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/about/policies/DisclosurePolicy.asp. Adopted February 2007. Revised December 2009, February 2012. Accessed May 13, 2015.

8. The AAOS orthopaedic disclosure program. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www7.aaos.org/education/disclosure. Accessed May 13, 2015.

9. Top 15 ortho companies by revenue [based on 2011 full-year financials]. OrthoStreams website. http://orthostreams.com/top-15-ortho-companies-by-revenue/http://orthostreams.com/2012/03/the-top-15-orthopedic-companies-ranked-by-2011 revenue/. Accessed May 13, 2015.

10. Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, Cram P. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(19):1759-1765.

11. Jegede KA, Ju B, Miller CP, Whang P, Grauer JN. Quantifying the variability of financial disclosure information reported by authors presenting research at multiple sports medicine conferences. Am J Orthop. 2011;40(11):583-587.

The relationship and collaboration between orthopedic surgeons and the orthopedic industry are considerable. Orthopedic surgeons can provide companies with important clinical input into the design of implants, facilitate commercialization of innovations developed by clinician entrepreneurs, and help provide rapid dissemination of new technologies.1,2 However, these relationships can result in conflicts of interest, thereby influencing the physicians’ judgment and choices and ultimately patient care.3,4 Making these potential conflicts transparent through physician disclosures is an accepted way to limit the negative effects of these relationships.5 The relationship between orthopedic surgeons and industry was brought to the forefront in 2007 with a settlement between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the 5 largest orthopedic implant makers.6 Among other things, this settlement required that each company publicly disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of all surgeons and organizations it paid, and how much. The DOJ settlement was one of the impetuses that led many orthopedic societies to adopt either voluntary or mandatory disclosure policies for their members.

In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an orthopedic disclosure program to promote transparency and confidence in its educational programs and decisions.7 One of the 2 main purposes of the disclosure program is “streamlining the disclosure process for orthopedic surgeons and others involved in organizational governance, all formats of continuing medical education [CME] and authors of enduring materials, clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and appropriate use criteria (AUC) development and editors-in-chief and editorial boards, from whom disclosure is required.”8 Disclosure is mandatory only for participants in the AAOS CME programs (including any podium or poster presentation) or authors of enduring materials; members of the AAOS Board of Directors, Board of Councilors, Board of Specialty Societies, councils, cabinets, committees, project teams, or other AAOS governance groups; editors-in-chief and editorial boards; and AAOS guideline development workgroups. Members who fail to disclose are informed they cannot participate in AAOS activities. All other members of the organization are not required to disclose any industry-related relationships, and any disclosure is completely voluntary.7 This seems contrary to the second main goal of the disclosure policy: “increase transparency throughout AAOS by making this disclosure program available to the public and to AAOS members.”8

We conducted a study to compare the disclosures posted by the top orthopedic companies with the disclosures made by their surgeon-consultants and to determine how many of these surgeons have disclosed this information on the AAOS website.

Materials and Methods

On November 26, 2012, we reviewed the websites of the top 13 orthopedic device companies by revenue (Stryker, DePuy Orthopaedics, Zimmer Holdings, Smith & Nephew, Synthes, Medtronic Spine, Biomet, DJO Global, Orthofix, NuVasive, Wright Medical Group, ArthroCare, Exactech)9 to identify their surgeon-consultants for 2011. We excluded non-US surgeons (DOJ disclosure not required), revenues under $1000, and reimbursement for meals and travel. Although the DOJ settlement required that each company disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of its paid consultants and the amounts paid, the settlement did not stipulate how long this must be continued. Of the 13 companies, only 6 (Stryker, DePuy, Smith & Nephew, Medtronic, Wright, Exactech) continued listing and updating surgeon disclosure information.

As the companies differed in how they defined surgeon consulting services, we defined surgeon-consultant payments as the sum of consulting payments, royalty payments, and research support. We searched for each surgeon-consultant’s name in the AAOS orthopedic disclosure program database.7 From the database, we determined whether the surgeon was a member of AAOS. All members were then categorized into those who disclosed all their payments, those who incompletely disclosed their payments, those who did not disclose any payments, and those who did not provide any information. They were then subdivided into those who had and had not participated in CME activities at the AAOS annual meeting in 2011 (participants were listed in the meeting proceedings). This does not take into account AAOS members who presented at other AAOS-sponsored CME courses during 2011 and who therefore were required to disclose. The information was categorized by company, payment amount, and overall. To simplify matters and deal with varying corporate categories, we divided payments into 4 amount groups: less than $10,000, $10,000 to $100,000, $100,001 to $1 million, and more than $1 million. Some orthopedic companies reported surgeon payments as categorical rather than exact amounts. In these cases, we coded the payment as the midpoint of the range.

Results

Overall, 549 AAOS members received payments of more than $1000 from at least 1 of the 6 companies. Of these surgeons, 307 (56%) fully disclosed their payments, and 242 (44%) did not (Table 1). Of the 32 surgeons who were on 2 corporate payment lists, 24 disclosed both companies, 6 disclosed only 1 company, and 2 failed to disclose either company. AAOS members who did not disclose payments received less than $10,000 (average, $3706) in 37% of cases (Table 2), between $10,000 and $100,000 (average, $34,025) in 54% of cases, between $100,001 and $1 million (average, $290,505) in 8% of cases, and more than $1 million (average, $5,126,000) in less than 1% of cases.

Number of consultants, number of surgeons not disclosing payments, and value of these payments varied from company to company (Table 3). The company with the most consultants listed 185 AAOS members, of which 37% had not disclosed payments (average, $39,604). Second was the company that listed 108 members; 39% had not disclosed payments (average, $38,426). The third company listed 102 members, of which 56% had not disclosed payments (average, $217,340). The company with the fourth most consultants listed 84 members; 43% had not disclosed payments (average, $9841). Next to last was the company listing 42 members, of which 52% had not disclosed payments (average, $160,634). The company with the fewest consultants listed 28 members; 61% had not disclosed payments (average $85,388).

Of AAOS members who attended the 2011 annual meeting, 94% fully disclosed industry payments (Table 1). Only 7% of the membership either failed to disclose or incompletely disclosed this relationship. In 36 cases (26%), members disclosed a financial relationship with at least 1 orthopedic company, but this relationship was not listed on the company’s website. One of the companies was responsible for 47% of the underreporting.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether surgeons fully disclosed (on the website for the AAOS disclosure program) payments they received from orthopedic companies. Overall compliance was poor, with 44% of surgeons not disclosing payments. The percentage of surgeons disclosing corporate relationships and payments received varied among orthopedic companies. It is unclear whether this reflects partial reporting, or AAOS disclosure policy being mandatory only for select members rather than the entire membership.

This study had a few limitations, none of which had a substantive impact on the results or conclusions. First, we could not determine how many AAOS members who were required to disclose actually disclosed. There is no mechanism for determining which members are involved in activities that require disclosure. Nonetheless, the intent of the policy is to make collaborations between orthopedic surgeons and industry transparent in order to address concerns about potential conflicts of interest. That 44% of AAOS members did not disclose their relationships cannot be considered a success. Second, information was available on the websites of only 6 of the top 15 orthopedic companies—a result stemming from the DOJ’s failure to specify how long these companies must continue posting disclosures. In this study, the lowest nondisclosure rate was 37%, and there is no reason to suspect that any other group of surgeon-consultants would be any more compliant with AAOS’s policy.

There are few reports on the effects of the DOJ settlement on the behavior of surgeon-consultants who are AAOS members. Hockenberry and colleagues10 found that, since the settlement, surgeon payments have increased, number of consultants has decreased, and the proportion of consultants from academia has increased. They thought their findings confirmed concerns that orthopedic device makers would deliberately select high-volume orthopedic surgeons as consultants in order to increase sales of their implants and gain market share at the expense of their competitors. The authors thought that AAOS had some power to address disclosure through its influence on its members, but that influence may not be enough. Jegede and colleagues11 found that a significant percentage (41%) of orthopedic surgeons who received corporate payments and presented at the AAOS annual meeting were inconsistent in submitting disclosure information. Results of the present study suggest that AAOS policy is weak and does not adequately address the issue and provide full transparency, either within the organization or to the public, of all its members’ industry relationships.

As the preeminent provider of musculoskeletal education to orthopedic surgeons and others, and with a membership totaling almost 39,000, AAOS is one of the most important orthopedic societies in the world. AAOS has clearly stated that one of its goals is to increase transparency by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. However, it can be completely transparent only if all its members are required to disclose their corporate relationships. This study demonstrated that AAOS’s policy of mandatory disclosure for select members and voluntary disclosure for all other members is ineffective. We found that 44% of members failed to disclose industry-derived payments. This inadequate level of compliance runs contrary to the AAOS goal of increasing transparency of surgeon–industry consulting by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. The AAOS disclosure program and the potential consequences of noncompliance need to be reevaluated by the organization if it wants its program to succeed.

The relationship and collaboration between orthopedic surgeons and the orthopedic industry are considerable. Orthopedic surgeons can provide companies with important clinical input into the design of implants, facilitate commercialization of innovations developed by clinician entrepreneurs, and help provide rapid dissemination of new technologies.1,2 However, these relationships can result in conflicts of interest, thereby influencing the physicians’ judgment and choices and ultimately patient care.3,4 Making these potential conflicts transparent through physician disclosures is an accepted way to limit the negative effects of these relationships.5 The relationship between orthopedic surgeons and industry was brought to the forefront in 2007 with a settlement between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the 5 largest orthopedic implant makers.6 Among other things, this settlement required that each company publicly disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of all surgeons and organizations it paid, and how much. The DOJ settlement was one of the impetuses that led many orthopedic societies to adopt either voluntary or mandatory disclosure policies for their members.

In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an orthopedic disclosure program to promote transparency and confidence in its educational programs and decisions.7 One of the 2 main purposes of the disclosure program is “streamlining the disclosure process for orthopedic surgeons and others involved in organizational governance, all formats of continuing medical education [CME] and authors of enduring materials, clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and appropriate use criteria (AUC) development and editors-in-chief and editorial boards, from whom disclosure is required.”8 Disclosure is mandatory only for participants in the AAOS CME programs (including any podium or poster presentation) or authors of enduring materials; members of the AAOS Board of Directors, Board of Councilors, Board of Specialty Societies, councils, cabinets, committees, project teams, or other AAOS governance groups; editors-in-chief and editorial boards; and AAOS guideline development workgroups. Members who fail to disclose are informed they cannot participate in AAOS activities. All other members of the organization are not required to disclose any industry-related relationships, and any disclosure is completely voluntary.7 This seems contrary to the second main goal of the disclosure policy: “increase transparency throughout AAOS by making this disclosure program available to the public and to AAOS members.”8

We conducted a study to compare the disclosures posted by the top orthopedic companies with the disclosures made by their surgeon-consultants and to determine how many of these surgeons have disclosed this information on the AAOS website.

Materials and Methods

On November 26, 2012, we reviewed the websites of the top 13 orthopedic device companies by revenue (Stryker, DePuy Orthopaedics, Zimmer Holdings, Smith & Nephew, Synthes, Medtronic Spine, Biomet, DJO Global, Orthofix, NuVasive, Wright Medical Group, ArthroCare, Exactech)9 to identify their surgeon-consultants for 2011. We excluded non-US surgeons (DOJ disclosure not required), revenues under $1000, and reimbursement for meals and travel. Although the DOJ settlement required that each company disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of its paid consultants and the amounts paid, the settlement did not stipulate how long this must be continued. Of the 13 companies, only 6 (Stryker, DePuy, Smith & Nephew, Medtronic, Wright, Exactech) continued listing and updating surgeon disclosure information.

As the companies differed in how they defined surgeon consulting services, we defined surgeon-consultant payments as the sum of consulting payments, royalty payments, and research support. We searched for each surgeon-consultant’s name in the AAOS orthopedic disclosure program database.7 From the database, we determined whether the surgeon was a member of AAOS. All members were then categorized into those who disclosed all their payments, those who incompletely disclosed their payments, those who did not disclose any payments, and those who did not provide any information. They were then subdivided into those who had and had not participated in CME activities at the AAOS annual meeting in 2011 (participants were listed in the meeting proceedings). This does not take into account AAOS members who presented at other AAOS-sponsored CME courses during 2011 and who therefore were required to disclose. The information was categorized by company, payment amount, and overall. To simplify matters and deal with varying corporate categories, we divided payments into 4 amount groups: less than $10,000, $10,000 to $100,000, $100,001 to $1 million, and more than $1 million. Some orthopedic companies reported surgeon payments as categorical rather than exact amounts. In these cases, we coded the payment as the midpoint of the range.

Results

Overall, 549 AAOS members received payments of more than $1000 from at least 1 of the 6 companies. Of these surgeons, 307 (56%) fully disclosed their payments, and 242 (44%) did not (Table 1). Of the 32 surgeons who were on 2 corporate payment lists, 24 disclosed both companies, 6 disclosed only 1 company, and 2 failed to disclose either company. AAOS members who did not disclose payments received less than $10,000 (average, $3706) in 37% of cases (Table 2), between $10,000 and $100,000 (average, $34,025) in 54% of cases, between $100,001 and $1 million (average, $290,505) in 8% of cases, and more than $1 million (average, $5,126,000) in less than 1% of cases.

Number of consultants, number of surgeons not disclosing payments, and value of these payments varied from company to company (Table 3). The company with the most consultants listed 185 AAOS members, of which 37% had not disclosed payments (average, $39,604). Second was the company that listed 108 members; 39% had not disclosed payments (average, $38,426). The third company listed 102 members, of which 56% had not disclosed payments (average, $217,340). The company with the fourth most consultants listed 84 members; 43% had not disclosed payments (average, $9841). Next to last was the company listing 42 members, of which 52% had not disclosed payments (average, $160,634). The company with the fewest consultants listed 28 members; 61% had not disclosed payments (average $85,388).

Of AAOS members who attended the 2011 annual meeting, 94% fully disclosed industry payments (Table 1). Only 7% of the membership either failed to disclose or incompletely disclosed this relationship. In 36 cases (26%), members disclosed a financial relationship with at least 1 orthopedic company, but this relationship was not listed on the company’s website. One of the companies was responsible for 47% of the underreporting.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether surgeons fully disclosed (on the website for the AAOS disclosure program) payments they received from orthopedic companies. Overall compliance was poor, with 44% of surgeons not disclosing payments. The percentage of surgeons disclosing corporate relationships and payments received varied among orthopedic companies. It is unclear whether this reflects partial reporting, or AAOS disclosure policy being mandatory only for select members rather than the entire membership.

This study had a few limitations, none of which had a substantive impact on the results or conclusions. First, we could not determine how many AAOS members who were required to disclose actually disclosed. There is no mechanism for determining which members are involved in activities that require disclosure. Nonetheless, the intent of the policy is to make collaborations between orthopedic surgeons and industry transparent in order to address concerns about potential conflicts of interest. That 44% of AAOS members did not disclose their relationships cannot be considered a success. Second, information was available on the websites of only 6 of the top 15 orthopedic companies—a result stemming from the DOJ’s failure to specify how long these companies must continue posting disclosures. In this study, the lowest nondisclosure rate was 37%, and there is no reason to suspect that any other group of surgeon-consultants would be any more compliant with AAOS’s policy.

There are few reports on the effects of the DOJ settlement on the behavior of surgeon-consultants who are AAOS members. Hockenberry and colleagues10 found that, since the settlement, surgeon payments have increased, number of consultants has decreased, and the proportion of consultants from academia has increased. They thought their findings confirmed concerns that orthopedic device makers would deliberately select high-volume orthopedic surgeons as consultants in order to increase sales of their implants and gain market share at the expense of their competitors. The authors thought that AAOS had some power to address disclosure through its influence on its members, but that influence may not be enough. Jegede and colleagues11 found that a significant percentage (41%) of orthopedic surgeons who received corporate payments and presented at the AAOS annual meeting were inconsistent in submitting disclosure information. Results of the present study suggest that AAOS policy is weak and does not adequately address the issue and provide full transparency, either within the organization or to the public, of all its members’ industry relationships.

As the preeminent provider of musculoskeletal education to orthopedic surgeons and others, and with a membership totaling almost 39,000, AAOS is one of the most important orthopedic societies in the world. AAOS has clearly stated that one of its goals is to increase transparency by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. However, it can be completely transparent only if all its members are required to disclose their corporate relationships. This study demonstrated that AAOS’s policy of mandatory disclosure for select members and voluntary disclosure for all other members is ineffective. We found that 44% of members failed to disclose industry-derived payments. This inadequate level of compliance runs contrary to the AAOS goal of increasing transparency of surgeon–industry consulting by making its surgeon disclosure program available to AAOS members and the public. The AAOS disclosure program and the potential consequences of noncompliance need to be reevaluated by the organization if it wants its program to succeed.

1. Crowninshield RD, Callaghan JJ. The orthopaedic profession and the industry partnership. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(457):73-77.

2. White AP, Vaccaro AR, Zdeblick T. Counterpoint: physician–industry relationships can be ethically established, and conflicts of interest can be ethically managed. Spine. 2007;32(11 suppl):S53-S57.

3. Steinbrook R. Online disclosure of physician–industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):325-327.

4. Steinbrook R. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):559-561.

5. Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Dinan MA, et al. Disclosing conflicts of interest in clinical research: views of institutional review boards, conflict of interest committees, and investigators. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(3):581-591, 481.

6. US Attorney’s Office, District of New Jersey. Monitoring and deferred prosecution agreements terminated with companies in hip and knee replacement industry [press release]. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Newark Division website. http://www.fbi.gov/newark/press-releases/2009/nk033009a.htm. March 30, 2009. Accessed May 13, 2015.

7. AAOS mandatory disclosure policy. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/about/policies/DisclosurePolicy.asp. Adopted February 2007. Revised December 2009, February 2012. Accessed May 13, 2015.

8. The AAOS orthopaedic disclosure program. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www7.aaos.org/education/disclosure. Accessed May 13, 2015.

9. Top 15 ortho companies by revenue [based on 2011 full-year financials]. OrthoStreams website. http://orthostreams.com/top-15-ortho-companies-by-revenue/http://orthostreams.com/2012/03/the-top-15-orthopedic-companies-ranked-by-2011 revenue/. Accessed May 13, 2015.

10. Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, Cram P. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(19):1759-1765.

11. Jegede KA, Ju B, Miller CP, Whang P, Grauer JN. Quantifying the variability of financial disclosure information reported by authors presenting research at multiple sports medicine conferences. Am J Orthop. 2011;40(11):583-587.

1. Crowninshield RD, Callaghan JJ. The orthopaedic profession and the industry partnership. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(457):73-77.

2. White AP, Vaccaro AR, Zdeblick T. Counterpoint: physician–industry relationships can be ethically established, and conflicts of interest can be ethically managed. Spine. 2007;32(11 suppl):S53-S57.

3. Steinbrook R. Online disclosure of physician–industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):325-327.

4. Steinbrook R. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):559-561.

5. Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Dinan MA, et al. Disclosing conflicts of interest in clinical research: views of institutional review boards, conflict of interest committees, and investigators. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(3):581-591, 481.

6. US Attorney’s Office, District of New Jersey. Monitoring and deferred prosecution agreements terminated with companies in hip and knee replacement industry [press release]. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Newark Division website. http://www.fbi.gov/newark/press-releases/2009/nk033009a.htm. March 30, 2009. Accessed May 13, 2015.

7. AAOS mandatory disclosure policy. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/about/policies/DisclosurePolicy.asp. Adopted February 2007. Revised December 2009, February 2012. Accessed May 13, 2015.

8. The AAOS orthopaedic disclosure program. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www7.aaos.org/education/disclosure. Accessed May 13, 2015.

9. Top 15 ortho companies by revenue [based on 2011 full-year financials]. OrthoStreams website. http://orthostreams.com/top-15-ortho-companies-by-revenue/http://orthostreams.com/2012/03/the-top-15-orthopedic-companies-ranked-by-2011 revenue/. Accessed May 13, 2015.

10. Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, Cram P. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(19):1759-1765.

11. Jegede KA, Ju B, Miller CP, Whang P, Grauer JN. Quantifying the variability of financial disclosure information reported by authors presenting research at multiple sports medicine conferences. Am J Orthop. 2011;40(11):583-587.