User login

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS)—developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s—is the gold standard for treating various cutaneous malignancies. It provides maximal conservation of uninvolved tissues while producing higher cure rates compared to wide local excision.1,2

We sought to assess the various characteristics that impact patient satisfaction to help Mohs surgeons incorporate relatively simple yet clinically significant practices into their patient encounters. We conducted a systematic literature search of peer-reviewed PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from database inception through November 2023 using the terms Mohs micrographic surgery and patient satisfaction. Among the inclusion criteria were studies involving participants having undergone MMS, with objective assessments on patient-reported satisfaction or preferences related to patient education, communication, anxiety-alleviating measures, or QOL in MMS. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet these criteria, were outdated and no longer clinically relevant, or measured unalterable factors with no significant impact on how Mohs surgeons could change clinical practice. Of the 157 nonreplicated studies identified, 34 met inclusion criteria.

Perioperative Patient Communication and Education Techniques

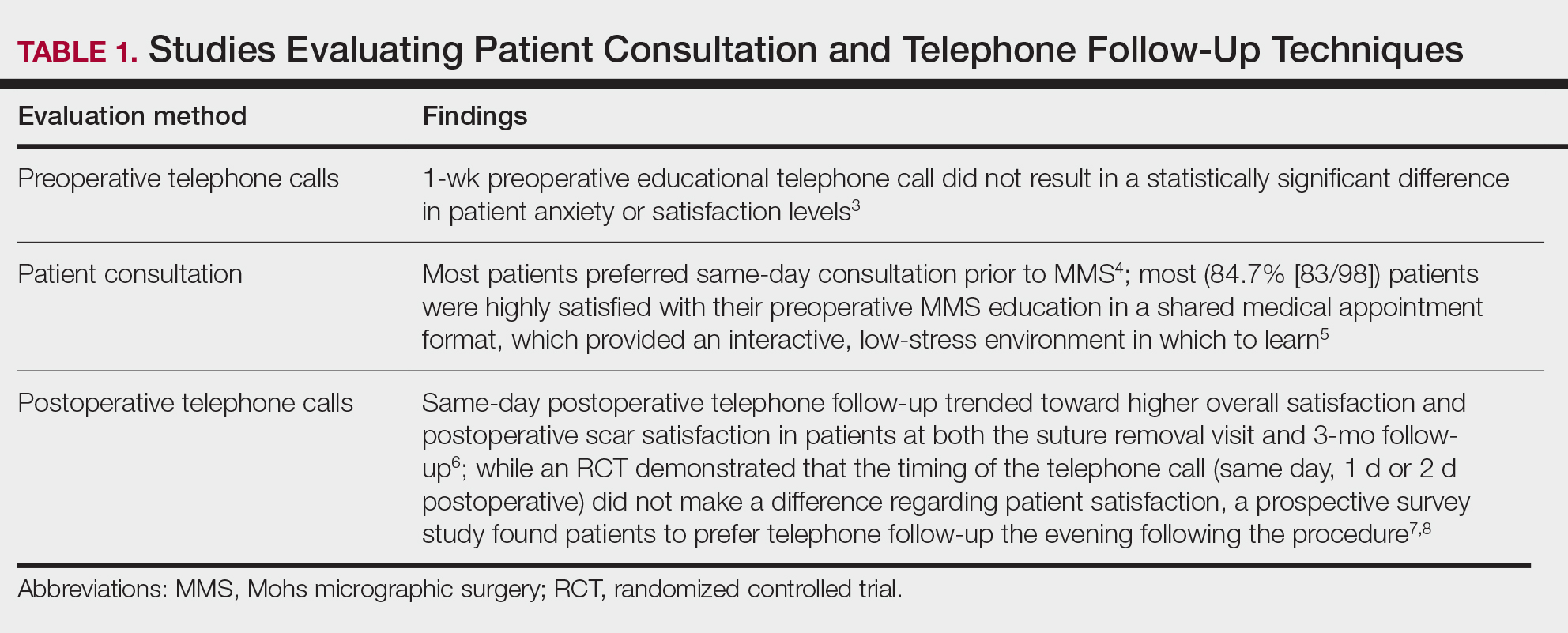

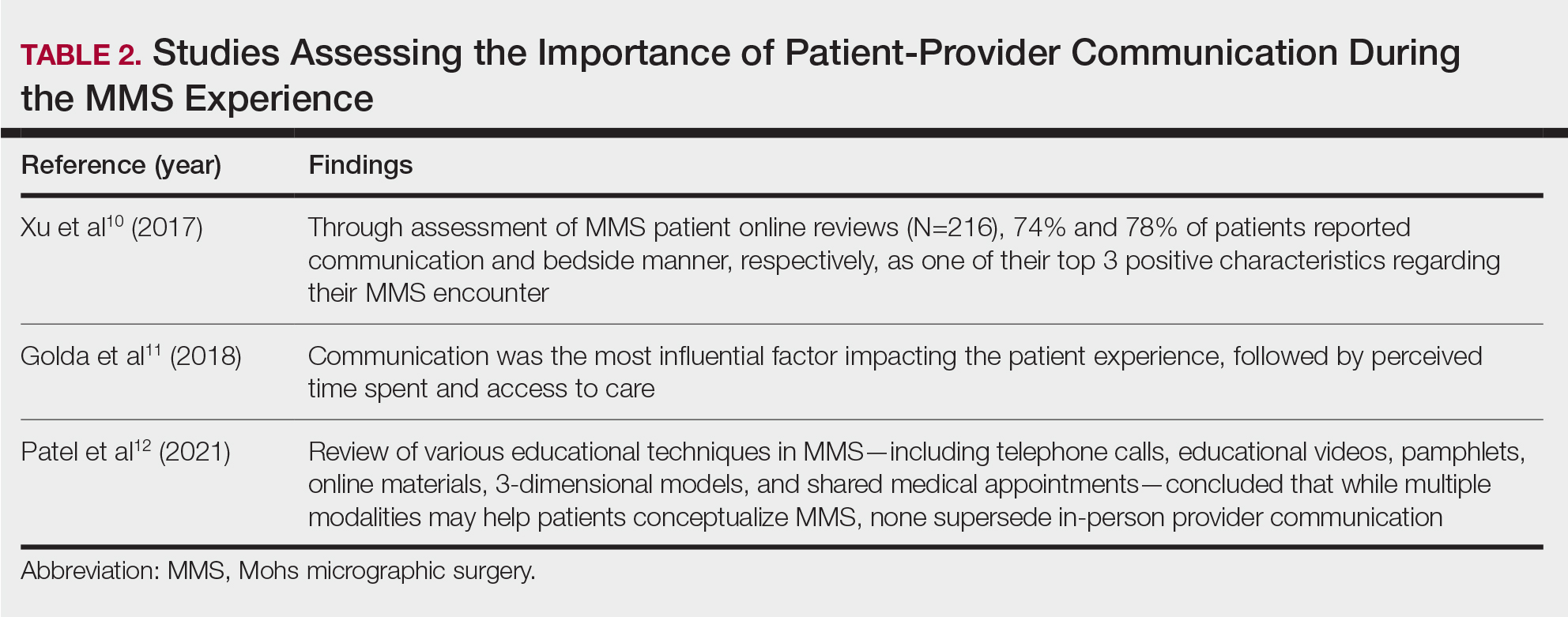

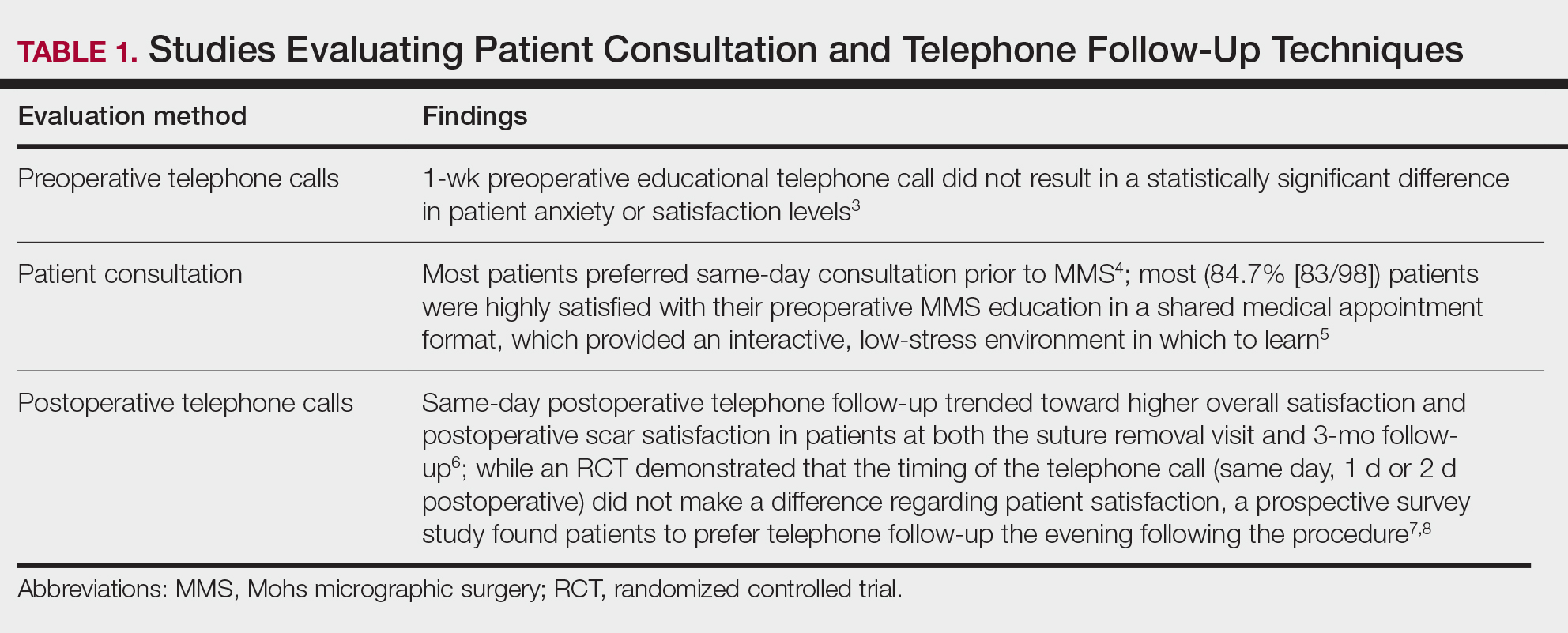

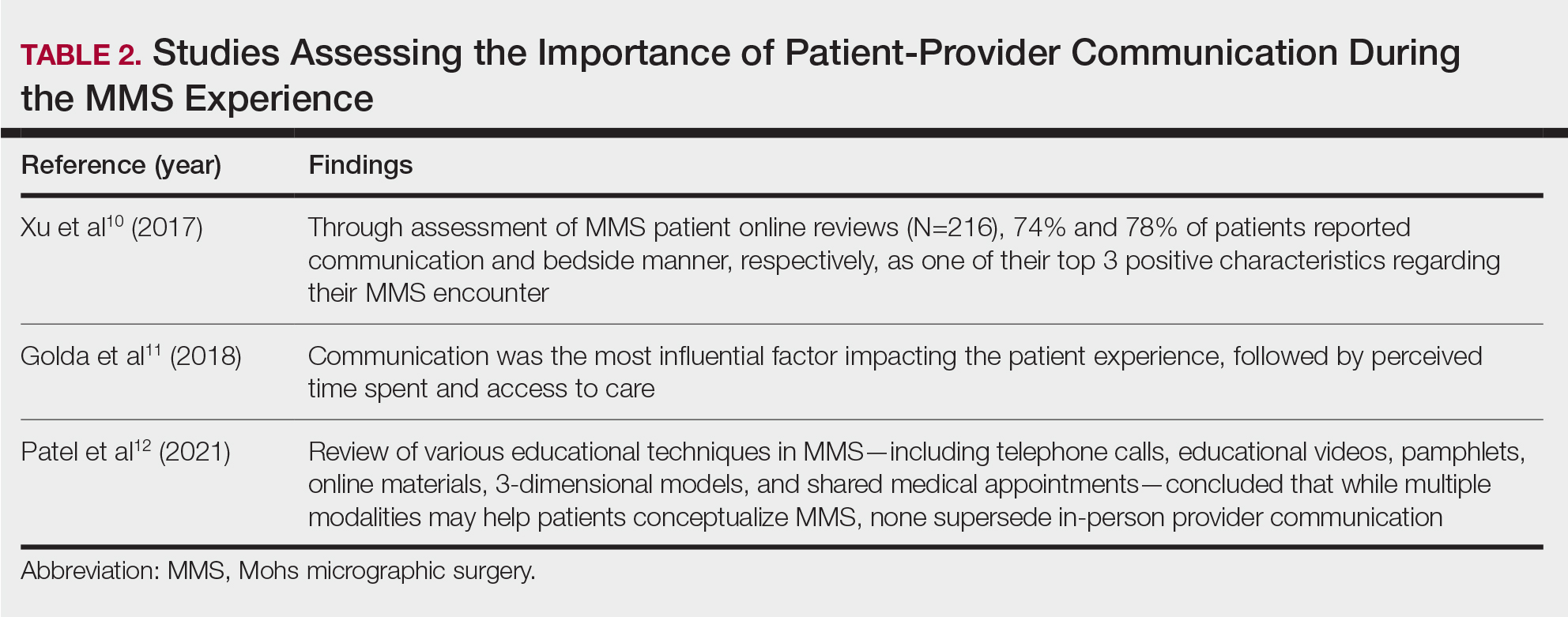

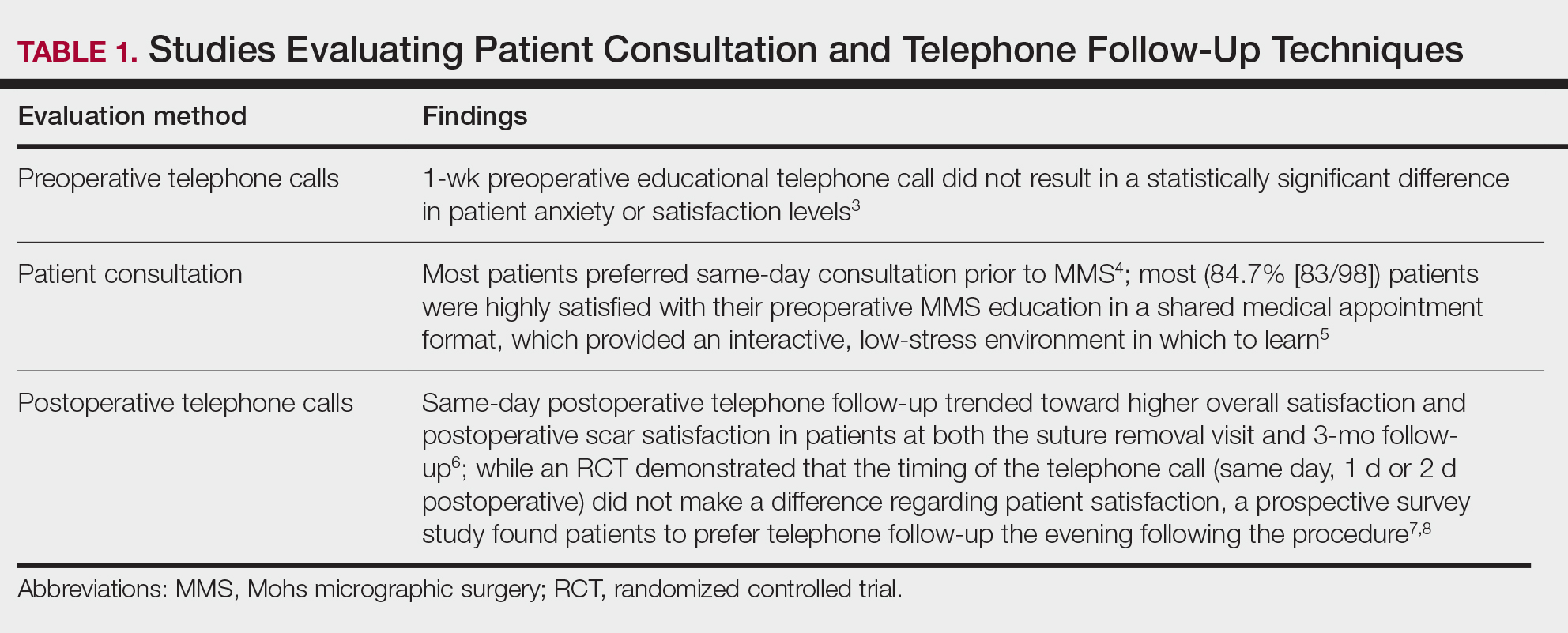

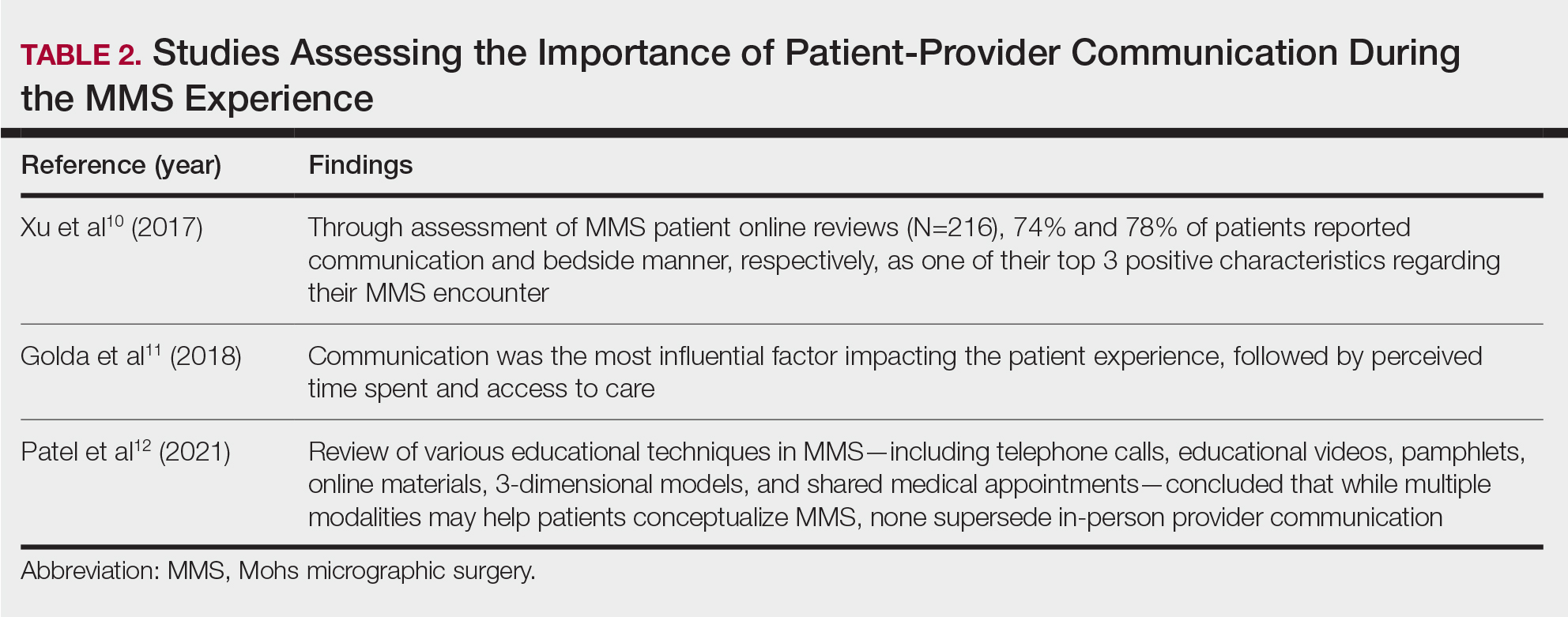

Perioperative Patient Communication—Many studies have evaluated the impact of perioperative patient-provider communication and education on patient satisfaction in those undergoing MMS. Studies focusing on preoperative and postoperative telephone calls, patient consultation formats, and patient-perceived impact of such communication modalities have been well documented (Table 1).3-8 The importance of the patient follow-up after MMS was further supported by a retrospective study concluding that 88.7% (86/97) of patients regarded follow-up visits as important, and 80% (77/97) desired additional follow-up 3 months after MMS.9 Additional studies have highlighted the importance of thorough and open perioperative patient-provider communication during MMS (Table 2).10-12

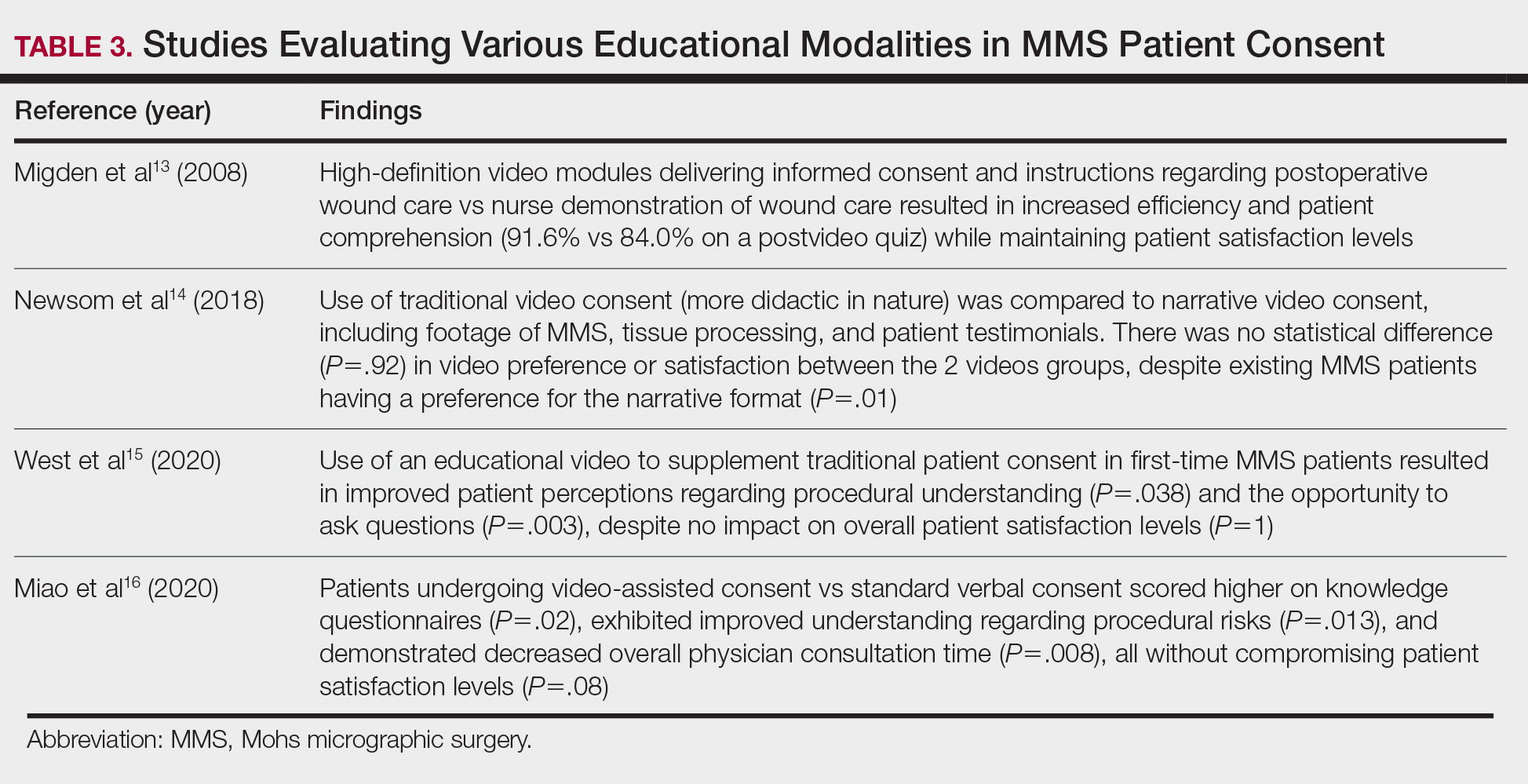

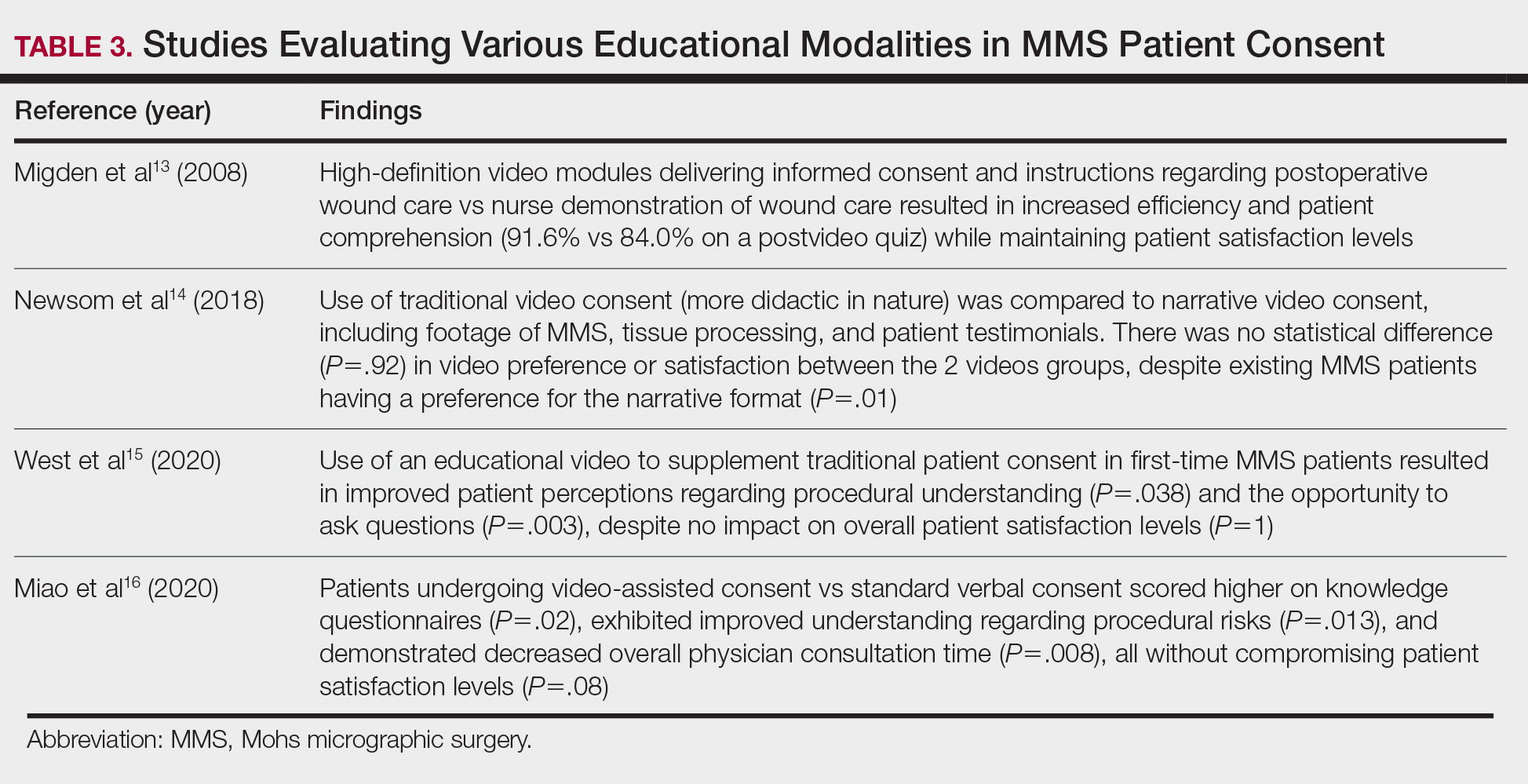

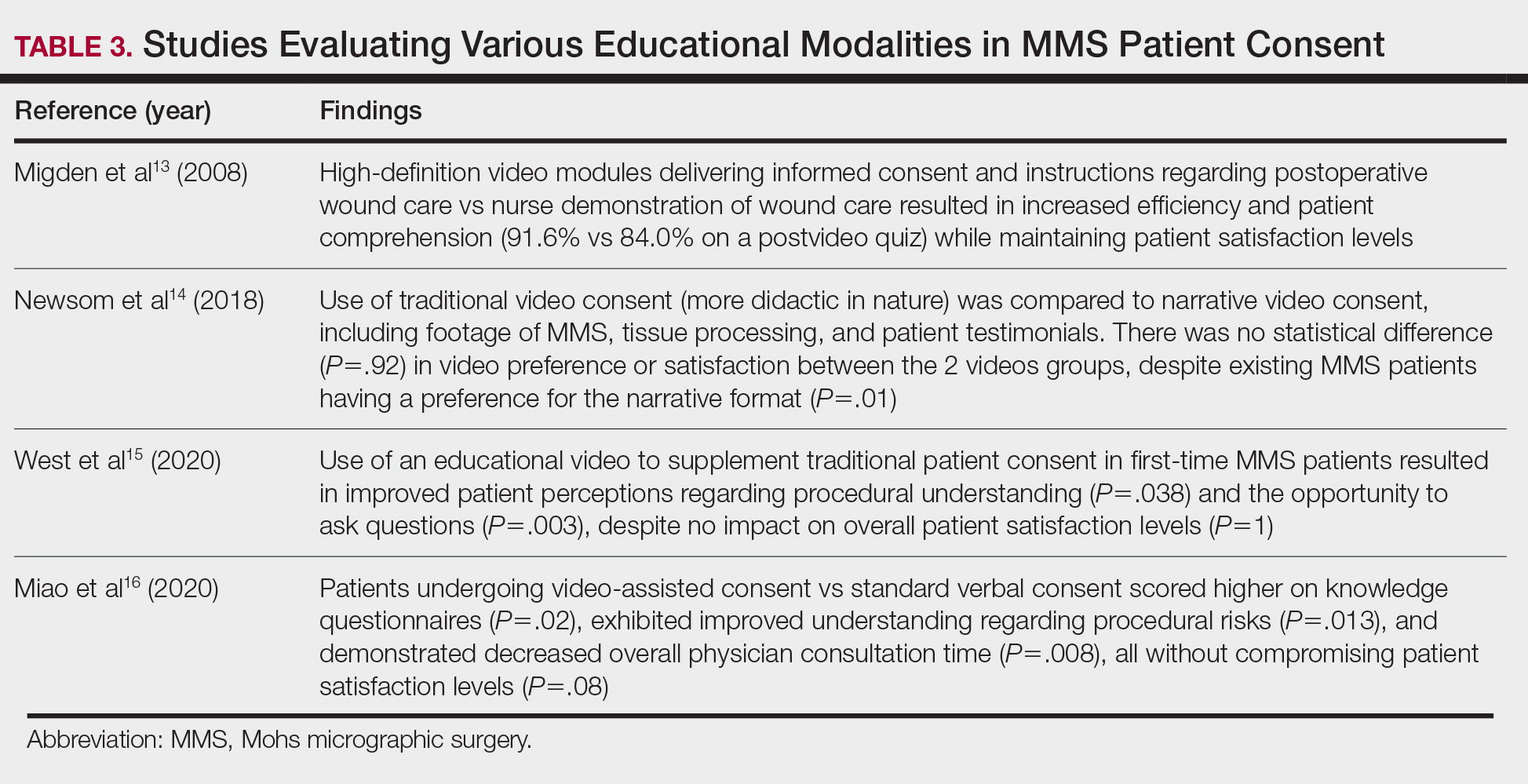

Patient-Education Techniques—Many studies have assessed the use of visual models to aid in patient education on MMS, specifically the preprocedural consent process (Table 3).13-16 Additionally, 2 randomized controlled trials assessing the use of at-home and same-day in-office preoperative educational videos concluded that these interventions increased patient knowledge and confidence regarding procedural risks and benefits, with no statistically significant differences in patient anxiety or satisfaction.17,18

Despite the availability of these educational videos, many patients often turn to online resources for self-education, which is problematic if reader literacy is incongruent with online readability. One study assessing readability of online MMS resources concluded that the most accessed articles exceeded the recommended reading level for adequate patient comprehension.19 A survey studying a wide range of variables related to patient satisfaction (eg, demographics, socioeconomics, health status) in 339 MMS patients found that those who considered themselves more involved in the decision-making process were more satisfied in the short-term, and married patients had even higher long-term satisfaction. Interestingly, this study also concluded that undergoing 3 or more MMS stages was associated with higher short- and long-term satisfaction, likely secondary to perceived effects of increased overall care, medical attention, and time spent with the provider.20

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding patient education and communication13-20:

- Preoperative and same-day postoperative telephone follow-up (TFU) do not show statistically significant impacts on patient satisfaction; however, TFU allows for identification of postoperative concerns and inadequate pain management, which may have downstream effects on long-term perception of the overall patient experience.

- The use of video-assisted consent yields improved patient satisfaction and knowledge, while video content—traditional or didactic—has no impact on satisfaction in new MMS patients.

- The use of at-home or same-day in-office preoperative educational videos can improve procedural knowledge and risk-benefit understanding of MMS while having no impact on satisfaction.

- Bedside manner and effective in-person communication by the provider often takes precedence in the patient experience; however, implementation of additional educational modalities should be considered.

Patient Anxiety and QOL

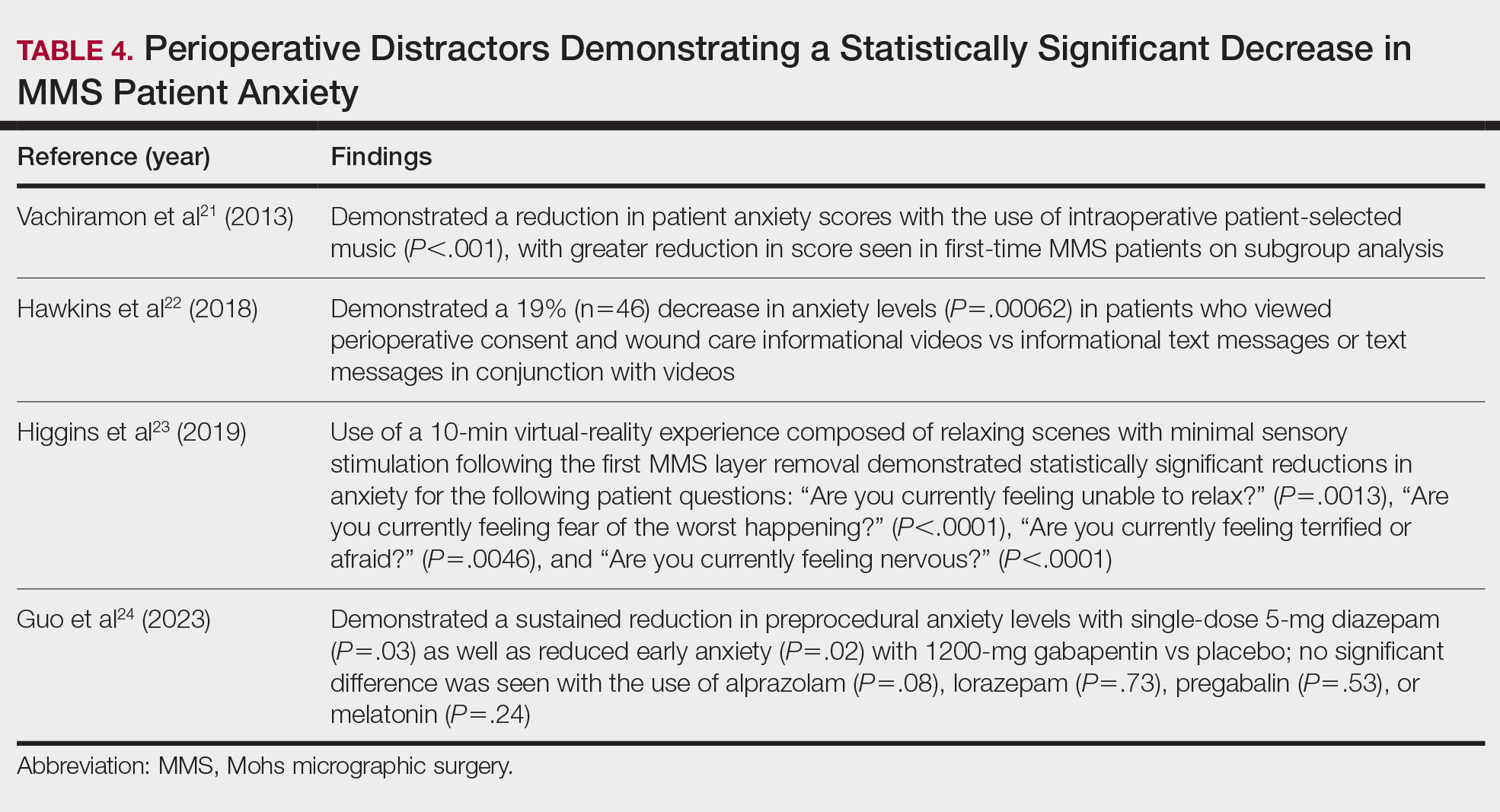

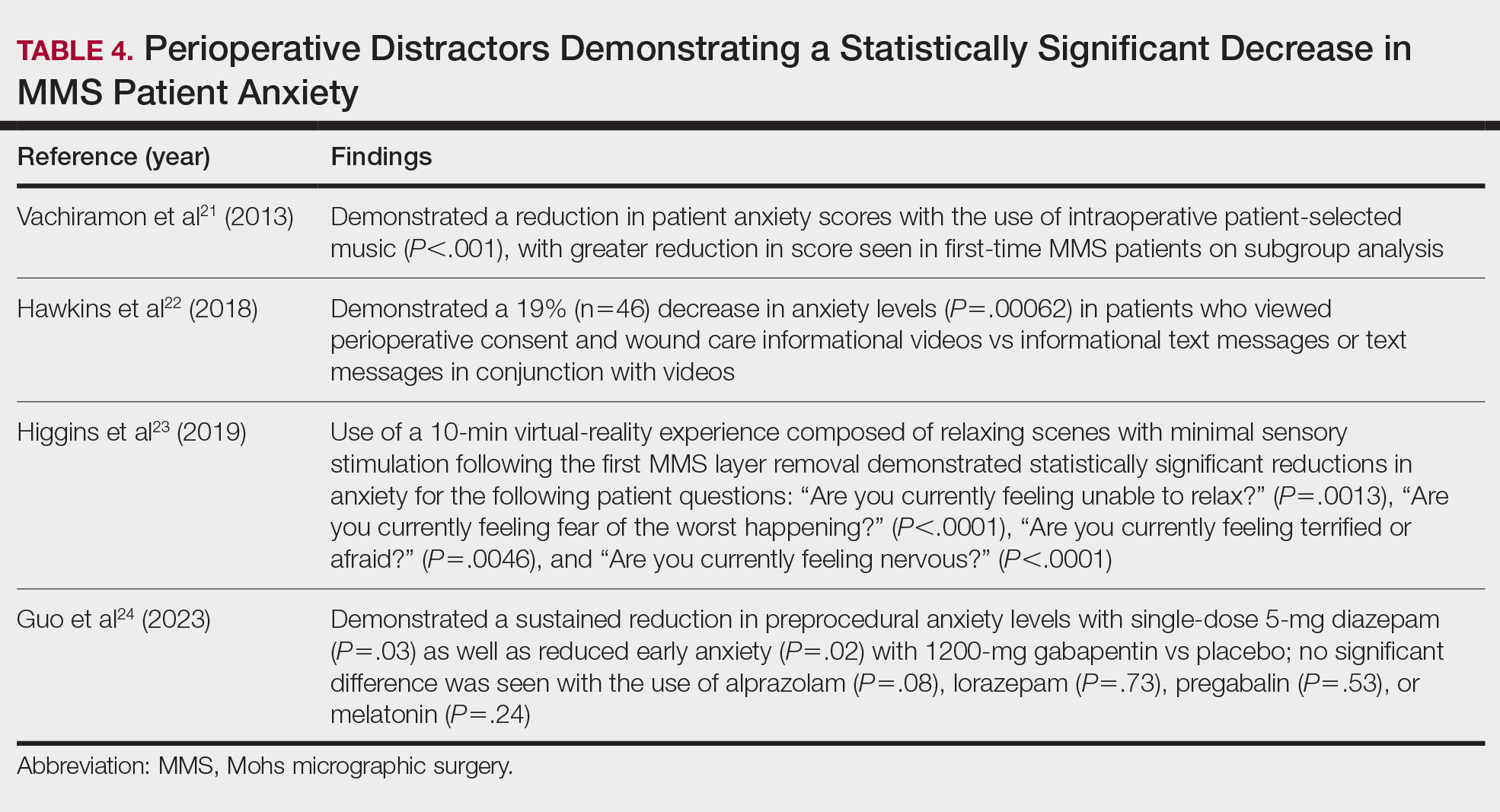

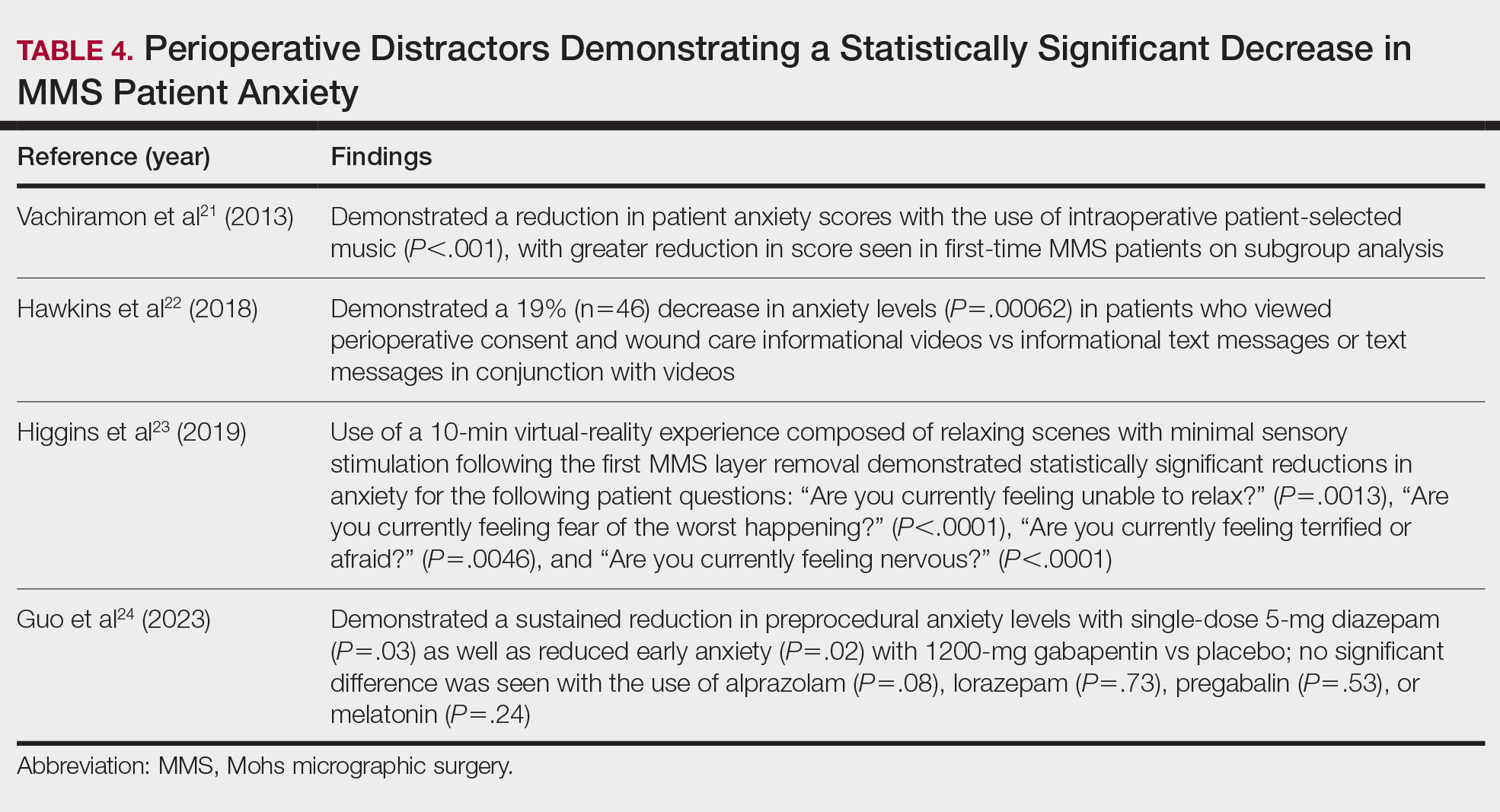

Reducing Patient Anxiety—The use of perioperative distractors to reduce patient anxiety may play an integral role when patients undergo MMS, as there often are prolonged waiting periods between stages when patients may feel increasingly vulnerable or anxious. Table 4 reviews studies on perioperative distractors that showed a statistically significant reduction in MMS patient anxiety.21-24

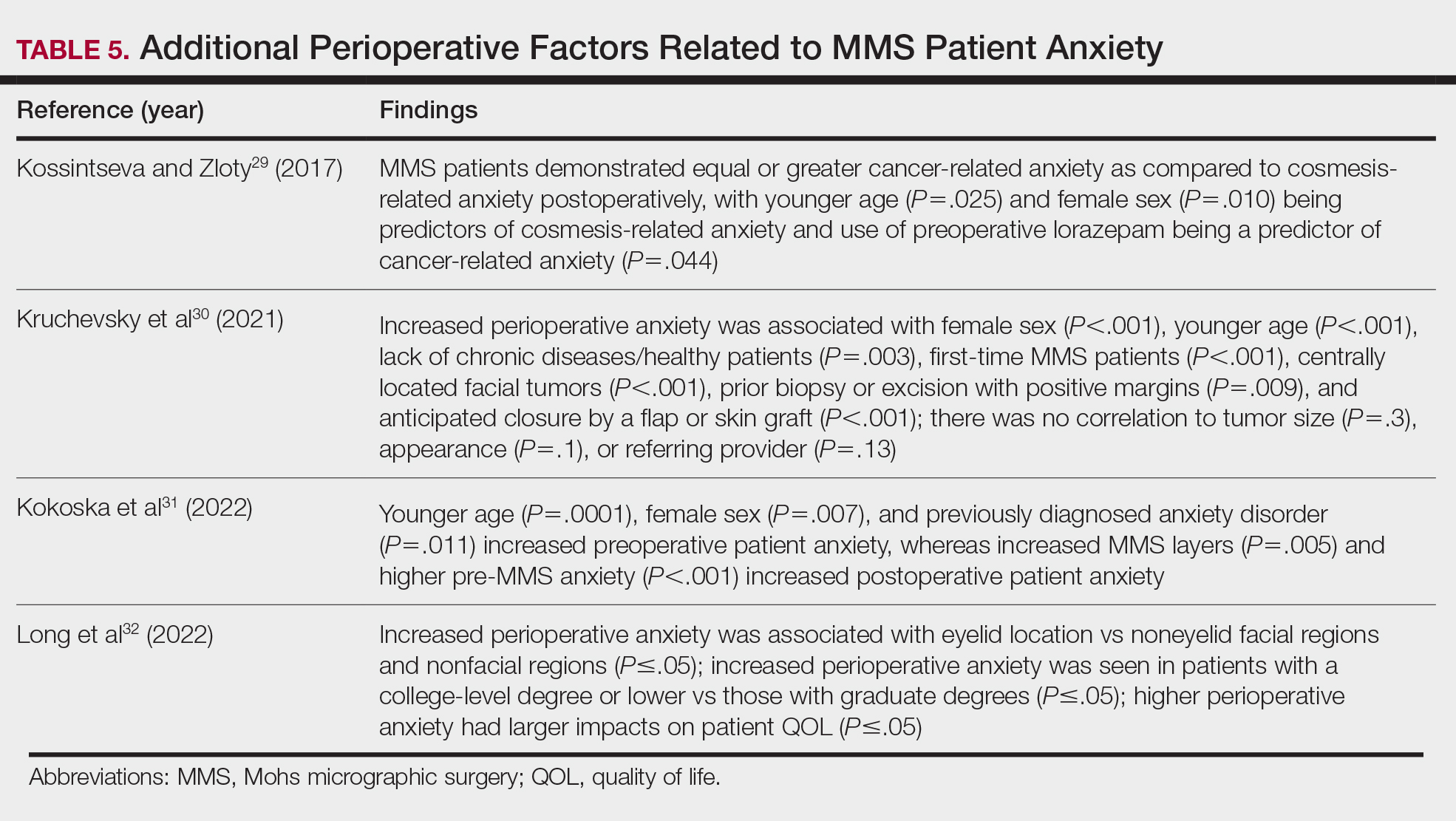

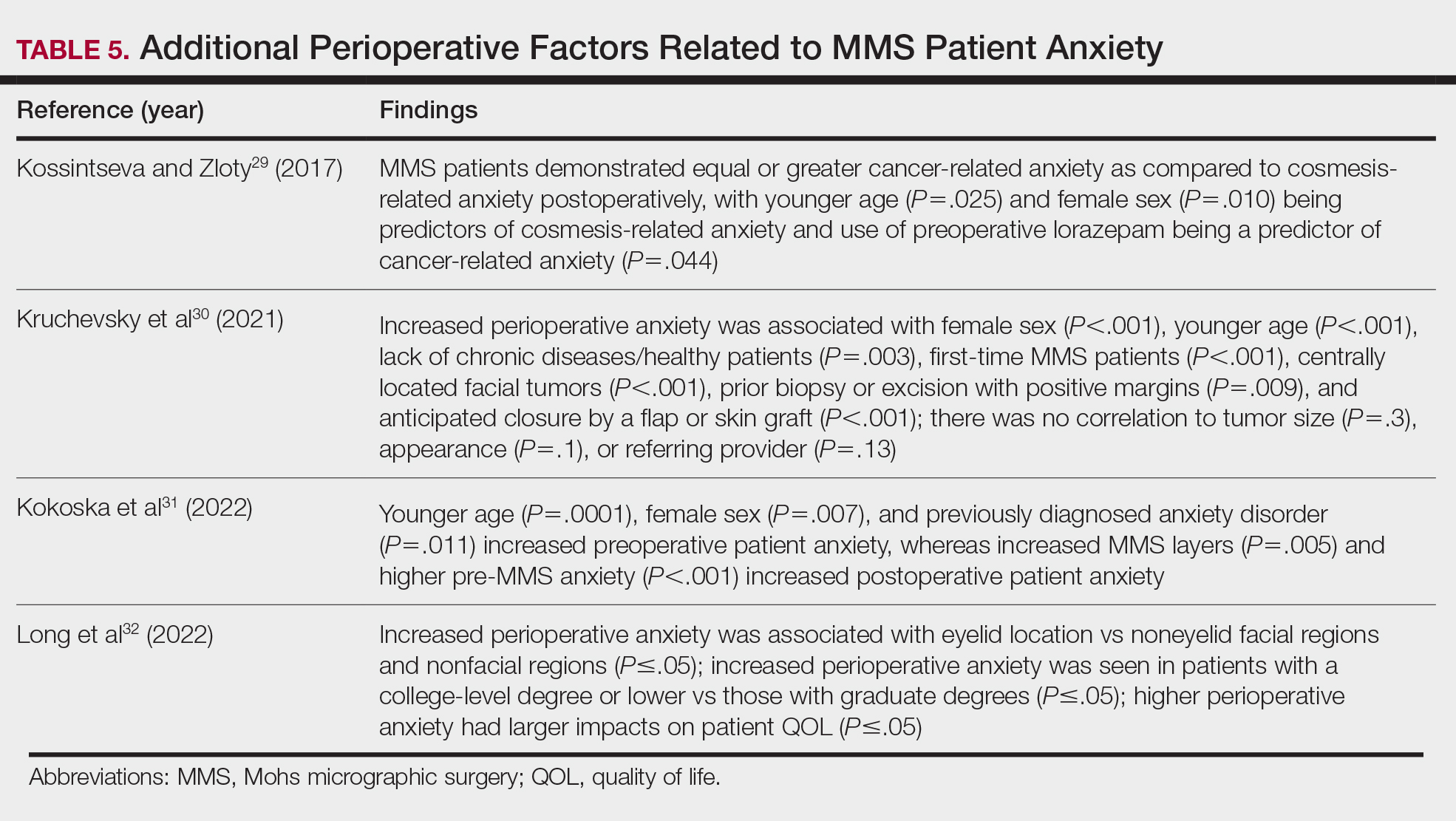

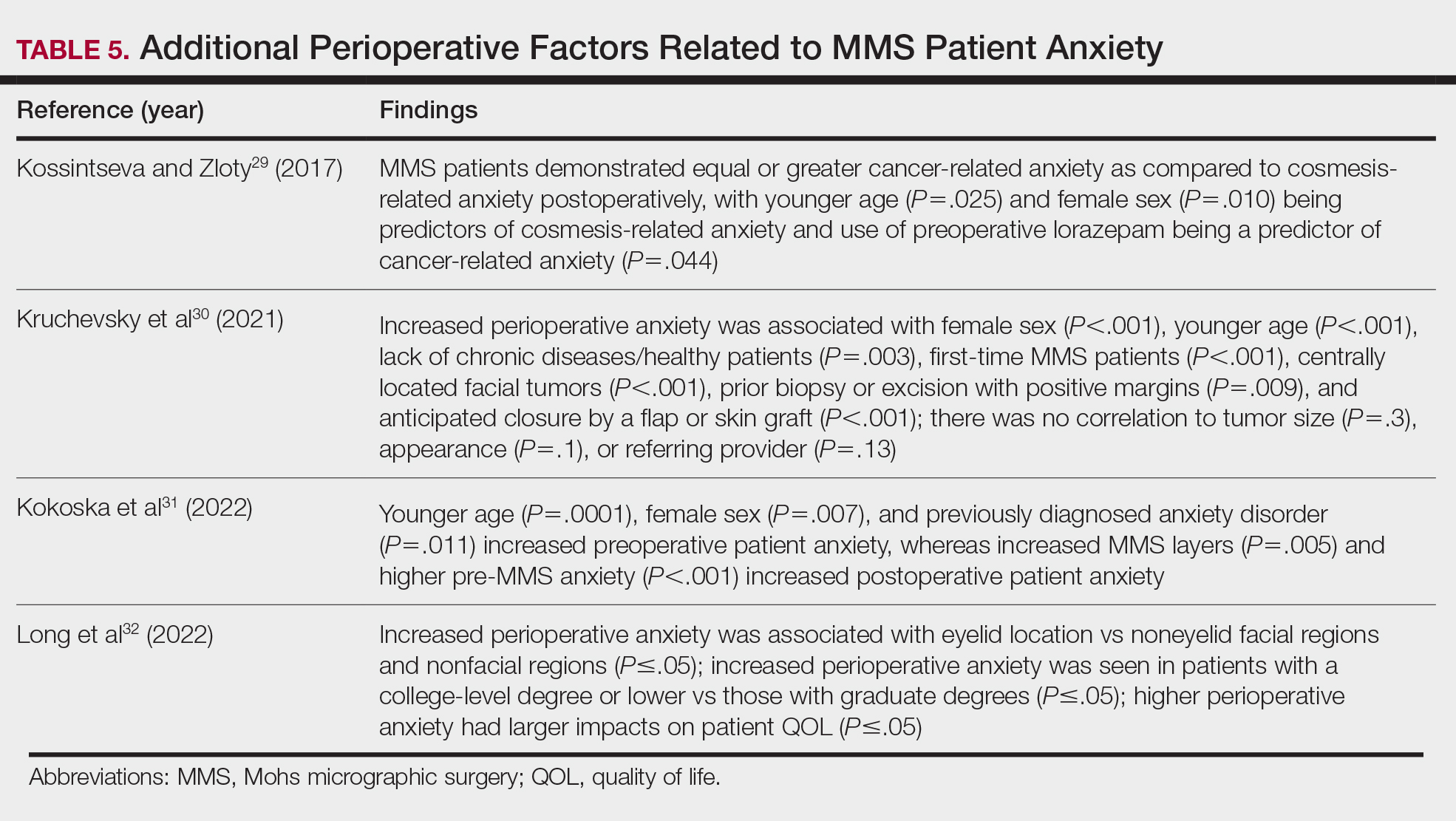

Although not statistically significant, additional studies evaluating the use of intraoperative anxiety-reduction methods in MMS have demonstrated a downtrend in patient anxiety with the following interventions: engaging in small talk with clinic staff, bringing a guest, eating, watching television, communicating surgical expectations with the provider, handholding, use of a stress ball, and use of 3-dimensional educational MMS models.25-27 Similarly, a survey of 73 patients undergoing MMS found that patients tended to enjoy complimentary beverages preprocedurally in the waiting room, reading, speaking with their guest, watching television, or using their telephone during wait times.28 Table 5 lists additional perioperative factors encompassing specific patient and surgical characteristics that help reduce patient anxiety.29-32

Patient QOL—Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety often show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience. A prospective observational study of MMS patients noted a statistically significant improvement in patient QOL scores 3 months postsurgery (P=.0007), demonstrating that MMS generally results in positive patient outcomes despite preprocedural anxiety.33 An additional prospective study in MMS patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer concluded that sex, age, and closure type—factors often shown to affect anxiety levels—did not significantly impact patient satisfaction.34 Similarly, high satisfaction levels can be expected among MMS patients undergoing treatment of melanoma in situ, with more than 90% of patients rating their treatment experience a 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) out of 5 in short- and long-term satisfaction assessments (38/41 and 40/42, respectively).35 This assessment, conducted 3 months postoperatively, asked patients to score the statement, “I am completely satisfied with the treatment of my skin problem,” on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Lastly, patient perception of their surgeon’s skill may contribute to levels of patient satisfaction. Although suture spacing has not been shown to affect surgical outcomes, it has been demonstrated to impact the patient’s perception of surgical skill and is further supported by a study concluding that closures with 2-mm spacing were ranked significantly lower by patients compared with closures with either 4- or 6-mm spacing (P=.005 and P=.012, respectively).36

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding anxiety-reducing measures and patient-perceived QOL21-36:

- Factors shown to decrease patient anxiety include patient personalized music, virtual-reality experience, perioperative informational videos, and 3-dimensional–printed MMS models.

- Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience.

- Higher anxiety can be associated with worse QOL scores in MMS patients, and additional factors that may have a negative impact on anxiety include female sex, younger age, and tumor location on the face.

Conclusion

Many factors affect patient satisfaction in MMS. Increased awareness and acknowledgement of these factors can foster improved clinical practice and patient experience, which can have downstream effects on patient compliance and overall psychosocial and medical well-being. With the movement toward value-based health care, patient satisfaction ratings are likely to play an increasingly important role in physician reimbursement. Adapting one’s practice to include high-quality, time-efficient, patient-centered care goes hand in hand with increasing MMS patient satisfaction. Careful evaluation and scrutiny of one’s current practices while remaining cognizant of patient population, resource availability, and clinical limitations often reveal opportunities for small adjustments that can have a great impact on patient satisfaction. This thorough assessment and review of the published literature aims to assist MMS surgeons in understanding the role that certain factors—(1) perioperative patient communication and education techniques and (2) patient anxiety, QOL, and additional considerations—have on overall satisfaction with MMS. Specific consideration should be placed on the fact that patient satisfaction is multifactorial, and many different interventions can have a positive impact on the overall patient experience.

- Trost LB, Bailin PL. History of Mohs surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2011; 29:135-139, vii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.01.010

- Leslie DF, Greenway HT. Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer. Australas J Dermatol. 1991;32:159-164. doi:10.1111/j.1440 -0960.1991.tb01783.x

- Sobanko JF, Da Silva D, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Preoperative telephone consultation does not decrease patient anxiety before Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.027

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim On SC, et al. Separate- versus same-day preoperative consultation in dermatologic surgery: a patient-centered investigation in an academic practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:240-247. doi:10.1111/dsu.12083

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.022

- Vance S, Fontecilla N, Samie FH, et al. Effect of postoperative telephone calls on patient satisfaction and scar satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1459-1464. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001913

- Hafiji J, Salmon P, Hussain W. Patient satisfaction with post-operative telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a New Zealand and U.K. experience. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:570-574. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2133.2012.11011.x

- Bednarek R, Jonak C, Golda N. Optimal timing of postoperative patient telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:220-221. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.07.106

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim-On S, et al. Postoperative preferences in cutaneous surgery: a patient-centered investigation from an academic dermatologic surgery practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:773-778. doi:10.1111/dsu.12136

- Xu S, Atanelov Z, Bhatia AC. Online patient-reported reviews of Mohs micrographic surgery: qualitative analysis of positive and negative experiences. Cutis. 2017;99:E25-E29.

- Golda N, Beeson S, Kohli N, et al. Recommendations for improving the patient experience in specialty encounters. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:653-659. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.040

- Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Patient education in Mohs surgery: a review and critical evaluation of techniques. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:217-224. doi:10.1007/s00403-020-02119-5

- Migden M, Chavez-Frazier A, Nguyen T. The use of high definition video modules for delivery of informed consent and wound care education in the Mohs surgery unit. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.02.001

- Newsom E, Lee E, Rossi A, et al. Modernizing the Mohs surgery consultation: instituting a video module for improved patient education and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:778-784. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001473

- West L, Srivastava D, Goldberg LH, et al. Multimedia technology used to supplement patient consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:586-590. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002134

- Miao Y, Venning VL, Mallitt KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing video-assisted informed consent with standard consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Int. 2020;1:13-20. doi:10.1016 /j.jdin.2020.03.005

- Mann J, Li L, Kulakov E, et al. Home viewing of educational video improves patient understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:93-97. doi:10.1111/ced.14845

- Delcambre M, Haynes D, Hajar T, et al. Using a multimedia tool for informed consent in Mohs surgery: a randomized trial measuring effects on patient anxiety, knowledge, and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:591-598. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002213

- Vargas CR, DePry J, Lee BT, et al. The readability of online patient information about Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1135-1141. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000866

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Hawkins SD, Koch SB, Williford PM, et al. Web app- and text message-based patient education in Mohs micrographic surgery-a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:924-932. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001489

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient-a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001854

- Guo D, Zloty DM, Kossintseva I. Efficacy and safety of anxiolytics in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:989-994. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000003905

- Locke MC, Wilkerson EC, Mistur RL, et al. 2015 Arte Poster Competition first place winner: assessing the correlation between patient anxiety and satisfaction for Mohs surgery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1070-1072.

- Yanes AF, Weil A, Furlan KC, et al. Effect of stress ball use or hand-holding on anxiety during skin cancer excision: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1045-1049. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1783

- Biro M, Kim I, Huynh A, et al. The use of 3-dimensionally printed models to optimize patient education and alleviate perioperative anxiety in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1339-1345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.085

- Ali FR, Al-Niaimi F, Craythorne EE, et al. Patient satisfaction and the waiting room in Mohs surgery: appropriate prewarning may abrogate boredom. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:e337-e338.

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035.

- Kruchevsky D, Hirth J, Capucha T, et al. Triggers of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1110-1112.

- Kokoska RE, Szeto MD, Steadman L, et al. Analysis of factors contributing to perioperative Mohs micrographic surgery anxiety: patient survey study at an academic center. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1279-1282.

- Long J, Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Levin A, et al. Perioperative anxiety associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a survey-based study. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:711-715.

- Zhang J, Miller CJ, O’Malley V, et al. Patient quality of life fluctuates before and after Mohs micrographic surgery: a longitudinal assessment of the patient experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1060-1067.

- Lee EB, Ford A, Clarey D, et al. Patient outcomes and satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery in patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Sur. 2021;47:1190-1194.

- Condie D, West L, Hynan LS, et al. Patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery for melanoma in situ. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:288-290.

- Arshanapalli A, Tra n JM, Aylward JL, et al. The effect of suture spacing on patient perception of surgical skill. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:735-736.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS)—developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s—is the gold standard for treating various cutaneous malignancies. It provides maximal conservation of uninvolved tissues while producing higher cure rates compared to wide local excision.1,2

We sought to assess the various characteristics that impact patient satisfaction to help Mohs surgeons incorporate relatively simple yet clinically significant practices into their patient encounters. We conducted a systematic literature search of peer-reviewed PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from database inception through November 2023 using the terms Mohs micrographic surgery and patient satisfaction. Among the inclusion criteria were studies involving participants having undergone MMS, with objective assessments on patient-reported satisfaction or preferences related to patient education, communication, anxiety-alleviating measures, or QOL in MMS. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet these criteria, were outdated and no longer clinically relevant, or measured unalterable factors with no significant impact on how Mohs surgeons could change clinical practice. Of the 157 nonreplicated studies identified, 34 met inclusion criteria.

Perioperative Patient Communication and Education Techniques

Perioperative Patient Communication—Many studies have evaluated the impact of perioperative patient-provider communication and education on patient satisfaction in those undergoing MMS. Studies focusing on preoperative and postoperative telephone calls, patient consultation formats, and patient-perceived impact of such communication modalities have been well documented (Table 1).3-8 The importance of the patient follow-up after MMS was further supported by a retrospective study concluding that 88.7% (86/97) of patients regarded follow-up visits as important, and 80% (77/97) desired additional follow-up 3 months after MMS.9 Additional studies have highlighted the importance of thorough and open perioperative patient-provider communication during MMS (Table 2).10-12

Patient-Education Techniques—Many studies have assessed the use of visual models to aid in patient education on MMS, specifically the preprocedural consent process (Table 3).13-16 Additionally, 2 randomized controlled trials assessing the use of at-home and same-day in-office preoperative educational videos concluded that these interventions increased patient knowledge and confidence regarding procedural risks and benefits, with no statistically significant differences in patient anxiety or satisfaction.17,18

Despite the availability of these educational videos, many patients often turn to online resources for self-education, which is problematic if reader literacy is incongruent with online readability. One study assessing readability of online MMS resources concluded that the most accessed articles exceeded the recommended reading level for adequate patient comprehension.19 A survey studying a wide range of variables related to patient satisfaction (eg, demographics, socioeconomics, health status) in 339 MMS patients found that those who considered themselves more involved in the decision-making process were more satisfied in the short-term, and married patients had even higher long-term satisfaction. Interestingly, this study also concluded that undergoing 3 or more MMS stages was associated with higher short- and long-term satisfaction, likely secondary to perceived effects of increased overall care, medical attention, and time spent with the provider.20

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding patient education and communication13-20:

- Preoperative and same-day postoperative telephone follow-up (TFU) do not show statistically significant impacts on patient satisfaction; however, TFU allows for identification of postoperative concerns and inadequate pain management, which may have downstream effects on long-term perception of the overall patient experience.

- The use of video-assisted consent yields improved patient satisfaction and knowledge, while video content—traditional or didactic—has no impact on satisfaction in new MMS patients.

- The use of at-home or same-day in-office preoperative educational videos can improve procedural knowledge and risk-benefit understanding of MMS while having no impact on satisfaction.

- Bedside manner and effective in-person communication by the provider often takes precedence in the patient experience; however, implementation of additional educational modalities should be considered.

Patient Anxiety and QOL

Reducing Patient Anxiety—The use of perioperative distractors to reduce patient anxiety may play an integral role when patients undergo MMS, as there often are prolonged waiting periods between stages when patients may feel increasingly vulnerable or anxious. Table 4 reviews studies on perioperative distractors that showed a statistically significant reduction in MMS patient anxiety.21-24

Although not statistically significant, additional studies evaluating the use of intraoperative anxiety-reduction methods in MMS have demonstrated a downtrend in patient anxiety with the following interventions: engaging in small talk with clinic staff, bringing a guest, eating, watching television, communicating surgical expectations with the provider, handholding, use of a stress ball, and use of 3-dimensional educational MMS models.25-27 Similarly, a survey of 73 patients undergoing MMS found that patients tended to enjoy complimentary beverages preprocedurally in the waiting room, reading, speaking with their guest, watching television, or using their telephone during wait times.28 Table 5 lists additional perioperative factors encompassing specific patient and surgical characteristics that help reduce patient anxiety.29-32

Patient QOL—Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety often show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience. A prospective observational study of MMS patients noted a statistically significant improvement in patient QOL scores 3 months postsurgery (P=.0007), demonstrating that MMS generally results in positive patient outcomes despite preprocedural anxiety.33 An additional prospective study in MMS patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer concluded that sex, age, and closure type—factors often shown to affect anxiety levels—did not significantly impact patient satisfaction.34 Similarly, high satisfaction levels can be expected among MMS patients undergoing treatment of melanoma in situ, with more than 90% of patients rating their treatment experience a 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) out of 5 in short- and long-term satisfaction assessments (38/41 and 40/42, respectively).35 This assessment, conducted 3 months postoperatively, asked patients to score the statement, “I am completely satisfied with the treatment of my skin problem,” on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Lastly, patient perception of their surgeon’s skill may contribute to levels of patient satisfaction. Although suture spacing has not been shown to affect surgical outcomes, it has been demonstrated to impact the patient’s perception of surgical skill and is further supported by a study concluding that closures with 2-mm spacing were ranked significantly lower by patients compared with closures with either 4- or 6-mm spacing (P=.005 and P=.012, respectively).36

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding anxiety-reducing measures and patient-perceived QOL21-36:

- Factors shown to decrease patient anxiety include patient personalized music, virtual-reality experience, perioperative informational videos, and 3-dimensional–printed MMS models.

- Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience.

- Higher anxiety can be associated with worse QOL scores in MMS patients, and additional factors that may have a negative impact on anxiety include female sex, younger age, and tumor location on the face.

Conclusion

Many factors affect patient satisfaction in MMS. Increased awareness and acknowledgement of these factors can foster improved clinical practice and patient experience, which can have downstream effects on patient compliance and overall psychosocial and medical well-being. With the movement toward value-based health care, patient satisfaction ratings are likely to play an increasingly important role in physician reimbursement. Adapting one’s practice to include high-quality, time-efficient, patient-centered care goes hand in hand with increasing MMS patient satisfaction. Careful evaluation and scrutiny of one’s current practices while remaining cognizant of patient population, resource availability, and clinical limitations often reveal opportunities for small adjustments that can have a great impact on patient satisfaction. This thorough assessment and review of the published literature aims to assist MMS surgeons in understanding the role that certain factors—(1) perioperative patient communication and education techniques and (2) patient anxiety, QOL, and additional considerations—have on overall satisfaction with MMS. Specific consideration should be placed on the fact that patient satisfaction is multifactorial, and many different interventions can have a positive impact on the overall patient experience.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS)—developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s—is the gold standard for treating various cutaneous malignancies. It provides maximal conservation of uninvolved tissues while producing higher cure rates compared to wide local excision.1,2

We sought to assess the various characteristics that impact patient satisfaction to help Mohs surgeons incorporate relatively simple yet clinically significant practices into their patient encounters. We conducted a systematic literature search of peer-reviewed PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from database inception through November 2023 using the terms Mohs micrographic surgery and patient satisfaction. Among the inclusion criteria were studies involving participants having undergone MMS, with objective assessments on patient-reported satisfaction or preferences related to patient education, communication, anxiety-alleviating measures, or QOL in MMS. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet these criteria, were outdated and no longer clinically relevant, or measured unalterable factors with no significant impact on how Mohs surgeons could change clinical practice. Of the 157 nonreplicated studies identified, 34 met inclusion criteria.

Perioperative Patient Communication and Education Techniques

Perioperative Patient Communication—Many studies have evaluated the impact of perioperative patient-provider communication and education on patient satisfaction in those undergoing MMS. Studies focusing on preoperative and postoperative telephone calls, patient consultation formats, and patient-perceived impact of such communication modalities have been well documented (Table 1).3-8 The importance of the patient follow-up after MMS was further supported by a retrospective study concluding that 88.7% (86/97) of patients regarded follow-up visits as important, and 80% (77/97) desired additional follow-up 3 months after MMS.9 Additional studies have highlighted the importance of thorough and open perioperative patient-provider communication during MMS (Table 2).10-12

Patient-Education Techniques—Many studies have assessed the use of visual models to aid in patient education on MMS, specifically the preprocedural consent process (Table 3).13-16 Additionally, 2 randomized controlled trials assessing the use of at-home and same-day in-office preoperative educational videos concluded that these interventions increased patient knowledge and confidence regarding procedural risks and benefits, with no statistically significant differences in patient anxiety or satisfaction.17,18

Despite the availability of these educational videos, many patients often turn to online resources for self-education, which is problematic if reader literacy is incongruent with online readability. One study assessing readability of online MMS resources concluded that the most accessed articles exceeded the recommended reading level for adequate patient comprehension.19 A survey studying a wide range of variables related to patient satisfaction (eg, demographics, socioeconomics, health status) in 339 MMS patients found that those who considered themselves more involved in the decision-making process were more satisfied in the short-term, and married patients had even higher long-term satisfaction. Interestingly, this study also concluded that undergoing 3 or more MMS stages was associated with higher short- and long-term satisfaction, likely secondary to perceived effects of increased overall care, medical attention, and time spent with the provider.20

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding patient education and communication13-20:

- Preoperative and same-day postoperative telephone follow-up (TFU) do not show statistically significant impacts on patient satisfaction; however, TFU allows for identification of postoperative concerns and inadequate pain management, which may have downstream effects on long-term perception of the overall patient experience.

- The use of video-assisted consent yields improved patient satisfaction and knowledge, while video content—traditional or didactic—has no impact on satisfaction in new MMS patients.

- The use of at-home or same-day in-office preoperative educational videos can improve procedural knowledge and risk-benefit understanding of MMS while having no impact on satisfaction.

- Bedside manner and effective in-person communication by the provider often takes precedence in the patient experience; however, implementation of additional educational modalities should be considered.

Patient Anxiety and QOL

Reducing Patient Anxiety—The use of perioperative distractors to reduce patient anxiety may play an integral role when patients undergo MMS, as there often are prolonged waiting periods between stages when patients may feel increasingly vulnerable or anxious. Table 4 reviews studies on perioperative distractors that showed a statistically significant reduction in MMS patient anxiety.21-24

Although not statistically significant, additional studies evaluating the use of intraoperative anxiety-reduction methods in MMS have demonstrated a downtrend in patient anxiety with the following interventions: engaging in small talk with clinic staff, bringing a guest, eating, watching television, communicating surgical expectations with the provider, handholding, use of a stress ball, and use of 3-dimensional educational MMS models.25-27 Similarly, a survey of 73 patients undergoing MMS found that patients tended to enjoy complimentary beverages preprocedurally in the waiting room, reading, speaking with their guest, watching television, or using their telephone during wait times.28 Table 5 lists additional perioperative factors encompassing specific patient and surgical characteristics that help reduce patient anxiety.29-32

Patient QOL—Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety often show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience. A prospective observational study of MMS patients noted a statistically significant improvement in patient QOL scores 3 months postsurgery (P=.0007), demonstrating that MMS generally results in positive patient outcomes despite preprocedural anxiety.33 An additional prospective study in MMS patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer concluded that sex, age, and closure type—factors often shown to affect anxiety levels—did not significantly impact patient satisfaction.34 Similarly, high satisfaction levels can be expected among MMS patients undergoing treatment of melanoma in situ, with more than 90% of patients rating their treatment experience a 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) out of 5 in short- and long-term satisfaction assessments (38/41 and 40/42, respectively).35 This assessment, conducted 3 months postoperatively, asked patients to score the statement, “I am completely satisfied with the treatment of my skin problem,” on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Lastly, patient perception of their surgeon’s skill may contribute to levels of patient satisfaction. Although suture spacing has not been shown to affect surgical outcomes, it has been demonstrated to impact the patient’s perception of surgical skill and is further supported by a study concluding that closures with 2-mm spacing were ranked significantly lower by patients compared with closures with either 4- or 6-mm spacing (P=.005 and P=.012, respectively).36

Synthesis of this information with emphasis on the higher evidence-based studies—including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials—yields the following beneficial interventions regarding anxiety-reducing measures and patient-perceived QOL21-36:

- Factors shown to decrease patient anxiety include patient personalized music, virtual-reality experience, perioperative informational videos, and 3-dimensional–printed MMS models.

- Many methods aimed at decreasing MMS-related patient anxiety show no direct impact on patient satisfaction, likely due to the multifactorial nature of the patient-perceived experience.

- Higher anxiety can be associated with worse QOL scores in MMS patients, and additional factors that may have a negative impact on anxiety include female sex, younger age, and tumor location on the face.

Conclusion

Many factors affect patient satisfaction in MMS. Increased awareness and acknowledgement of these factors can foster improved clinical practice and patient experience, which can have downstream effects on patient compliance and overall psychosocial and medical well-being. With the movement toward value-based health care, patient satisfaction ratings are likely to play an increasingly important role in physician reimbursement. Adapting one’s practice to include high-quality, time-efficient, patient-centered care goes hand in hand with increasing MMS patient satisfaction. Careful evaluation and scrutiny of one’s current practices while remaining cognizant of patient population, resource availability, and clinical limitations often reveal opportunities for small adjustments that can have a great impact on patient satisfaction. This thorough assessment and review of the published literature aims to assist MMS surgeons in understanding the role that certain factors—(1) perioperative patient communication and education techniques and (2) patient anxiety, QOL, and additional considerations—have on overall satisfaction with MMS. Specific consideration should be placed on the fact that patient satisfaction is multifactorial, and many different interventions can have a positive impact on the overall patient experience.

- Trost LB, Bailin PL. History of Mohs surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2011; 29:135-139, vii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.01.010

- Leslie DF, Greenway HT. Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer. Australas J Dermatol. 1991;32:159-164. doi:10.1111/j.1440 -0960.1991.tb01783.x

- Sobanko JF, Da Silva D, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Preoperative telephone consultation does not decrease patient anxiety before Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.027

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim On SC, et al. Separate- versus same-day preoperative consultation in dermatologic surgery: a patient-centered investigation in an academic practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:240-247. doi:10.1111/dsu.12083

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.022

- Vance S, Fontecilla N, Samie FH, et al. Effect of postoperative telephone calls on patient satisfaction and scar satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1459-1464. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001913

- Hafiji J, Salmon P, Hussain W. Patient satisfaction with post-operative telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a New Zealand and U.K. experience. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:570-574. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2133.2012.11011.x

- Bednarek R, Jonak C, Golda N. Optimal timing of postoperative patient telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:220-221. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.07.106

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim-On S, et al. Postoperative preferences in cutaneous surgery: a patient-centered investigation from an academic dermatologic surgery practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:773-778. doi:10.1111/dsu.12136

- Xu S, Atanelov Z, Bhatia AC. Online patient-reported reviews of Mohs micrographic surgery: qualitative analysis of positive and negative experiences. Cutis. 2017;99:E25-E29.

- Golda N, Beeson S, Kohli N, et al. Recommendations for improving the patient experience in specialty encounters. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:653-659. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.040

- Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Patient education in Mohs surgery: a review and critical evaluation of techniques. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:217-224. doi:10.1007/s00403-020-02119-5

- Migden M, Chavez-Frazier A, Nguyen T. The use of high definition video modules for delivery of informed consent and wound care education in the Mohs surgery unit. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.02.001

- Newsom E, Lee E, Rossi A, et al. Modernizing the Mohs surgery consultation: instituting a video module for improved patient education and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:778-784. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001473

- West L, Srivastava D, Goldberg LH, et al. Multimedia technology used to supplement patient consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:586-590. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002134

- Miao Y, Venning VL, Mallitt KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing video-assisted informed consent with standard consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Int. 2020;1:13-20. doi:10.1016 /j.jdin.2020.03.005

- Mann J, Li L, Kulakov E, et al. Home viewing of educational video improves patient understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:93-97. doi:10.1111/ced.14845

- Delcambre M, Haynes D, Hajar T, et al. Using a multimedia tool for informed consent in Mohs surgery: a randomized trial measuring effects on patient anxiety, knowledge, and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:591-598. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002213

- Vargas CR, DePry J, Lee BT, et al. The readability of online patient information about Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1135-1141. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000866

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Hawkins SD, Koch SB, Williford PM, et al. Web app- and text message-based patient education in Mohs micrographic surgery-a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:924-932. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001489

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient-a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001854

- Guo D, Zloty DM, Kossintseva I. Efficacy and safety of anxiolytics in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:989-994. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000003905

- Locke MC, Wilkerson EC, Mistur RL, et al. 2015 Arte Poster Competition first place winner: assessing the correlation between patient anxiety and satisfaction for Mohs surgery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1070-1072.

- Yanes AF, Weil A, Furlan KC, et al. Effect of stress ball use or hand-holding on anxiety during skin cancer excision: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1045-1049. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1783

- Biro M, Kim I, Huynh A, et al. The use of 3-dimensionally printed models to optimize patient education and alleviate perioperative anxiety in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1339-1345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.085

- Ali FR, Al-Niaimi F, Craythorne EE, et al. Patient satisfaction and the waiting room in Mohs surgery: appropriate prewarning may abrogate boredom. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:e337-e338.

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035.

- Kruchevsky D, Hirth J, Capucha T, et al. Triggers of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1110-1112.

- Kokoska RE, Szeto MD, Steadman L, et al. Analysis of factors contributing to perioperative Mohs micrographic surgery anxiety: patient survey study at an academic center. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1279-1282.

- Long J, Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Levin A, et al. Perioperative anxiety associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a survey-based study. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:711-715.

- Zhang J, Miller CJ, O’Malley V, et al. Patient quality of life fluctuates before and after Mohs micrographic surgery: a longitudinal assessment of the patient experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1060-1067.

- Lee EB, Ford A, Clarey D, et al. Patient outcomes and satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery in patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Sur. 2021;47:1190-1194.

- Condie D, West L, Hynan LS, et al. Patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery for melanoma in situ. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:288-290.

- Arshanapalli A, Tra n JM, Aylward JL, et al. The effect of suture spacing on patient perception of surgical skill. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:735-736.

- Trost LB, Bailin PL. History of Mohs surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2011; 29:135-139, vii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.01.010

- Leslie DF, Greenway HT. Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer. Australas J Dermatol. 1991;32:159-164. doi:10.1111/j.1440 -0960.1991.tb01783.x

- Sobanko JF, Da Silva D, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Preoperative telephone consultation does not decrease patient anxiety before Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.027

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim On SC, et al. Separate- versus same-day preoperative consultation in dermatologic surgery: a patient-centered investigation in an academic practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:240-247. doi:10.1111/dsu.12083

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.022

- Vance S, Fontecilla N, Samie FH, et al. Effect of postoperative telephone calls on patient satisfaction and scar satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1459-1464. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001913

- Hafiji J, Salmon P, Hussain W. Patient satisfaction with post-operative telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a New Zealand and U.K. experience. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:570-574. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2133.2012.11011.x

- Bednarek R, Jonak C, Golda N. Optimal timing of postoperative patient telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:220-221. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2020.07.106

- Sharon VR, Armstrong AW, Jim-On S, et al. Postoperative preferences in cutaneous surgery: a patient-centered investigation from an academic dermatologic surgery practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:773-778. doi:10.1111/dsu.12136

- Xu S, Atanelov Z, Bhatia AC. Online patient-reported reviews of Mohs micrographic surgery: qualitative analysis of positive and negative experiences. Cutis. 2017;99:E25-E29.

- Golda N, Beeson S, Kohli N, et al. Recommendations for improving the patient experience in specialty encounters. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:653-659. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.040

- Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Patient education in Mohs surgery: a review and critical evaluation of techniques. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:217-224. doi:10.1007/s00403-020-02119-5

- Migden M, Chavez-Frazier A, Nguyen T. The use of high definition video modules for delivery of informed consent and wound care education in the Mohs surgery unit. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.02.001

- Newsom E, Lee E, Rossi A, et al. Modernizing the Mohs surgery consultation: instituting a video module for improved patient education and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:778-784. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001473

- West L, Srivastava D, Goldberg LH, et al. Multimedia technology used to supplement patient consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:586-590. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002134

- Miao Y, Venning VL, Mallitt KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing video-assisted informed consent with standard consent for Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Int. 2020;1:13-20. doi:10.1016 /j.jdin.2020.03.005

- Mann J, Li L, Kulakov E, et al. Home viewing of educational video improves patient understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:93-97. doi:10.1111/ced.14845

- Delcambre M, Haynes D, Hajar T, et al. Using a multimedia tool for informed consent in Mohs surgery: a randomized trial measuring effects on patient anxiety, knowledge, and satisfaction. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:591-598. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002213

- Vargas CR, DePry J, Lee BT, et al. The readability of online patient information about Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1135-1141. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000866

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Hawkins SD, Koch SB, Williford PM, et al. Web app- and text message-based patient education in Mohs micrographic surgery-a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:924-932. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001489

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient-a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001854

- Guo D, Zloty DM, Kossintseva I. Efficacy and safety of anxiolytics in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:989-994. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000003905

- Locke MC, Wilkerson EC, Mistur RL, et al. 2015 Arte Poster Competition first place winner: assessing the correlation between patient anxiety and satisfaction for Mohs surgery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1070-1072.

- Yanes AF, Weil A, Furlan KC, et al. Effect of stress ball use or hand-holding on anxiety during skin cancer excision: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1045-1049. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1783

- Biro M, Kim I, Huynh A, et al. The use of 3-dimensionally printed models to optimize patient education and alleviate perioperative anxiety in Mohs micrographic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1339-1345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.085

- Ali FR, Al-Niaimi F, Craythorne EE, et al. Patient satisfaction and the waiting room in Mohs surgery: appropriate prewarning may abrogate boredom. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:e337-e338.

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035.

- Kruchevsky D, Hirth J, Capucha T, et al. Triggers of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1110-1112.

- Kokoska RE, Szeto MD, Steadman L, et al. Analysis of factors contributing to perioperative Mohs micrographic surgery anxiety: patient survey study at an academic center. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1279-1282.

- Long J, Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Levin A, et al. Perioperative anxiety associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a survey-based study. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:711-715.

- Zhang J, Miller CJ, O’Malley V, et al. Patient quality of life fluctuates before and after Mohs micrographic surgery: a longitudinal assessment of the patient experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1060-1067.

- Lee EB, Ford A, Clarey D, et al. Patient outcomes and satisfaction after Mohs micrographic surgery in patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Sur. 2021;47:1190-1194.

- Condie D, West L, Hynan LS, et al. Patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery for melanoma in situ. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:288-290.

- Arshanapalli A, Tra n JM, Aylward JL, et al. The effect of suture spacing on patient perception of surgical skill. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:735-736.

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

PRACTICE POINTS

- When patients are treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), thorough in-person dialogue augmented by pre- and same-day telephone follow-ups can help them feel heard and better supported, even though follow-up calls alone may not drive satisfaction scores.

- Increased awareness and implementation of the various factors influencing patient satisfaction and quality of life in MMS can enhance clinical practice and improve patient experiences, with potential impacts on compliance, psychosocial well-being, medical outcomes, and physician reimbursement.

- Patient satisfaction and procedural understanding can be improved with video and visual-based education. Anxiety-reducing methods help lower perioperative stress.

How to Foster Camaraderie in Dermatology Residency

Change is inevitable in residency as well as in life. Every year on July 1, the atmosphere and social structure of residencies change with the new postgraduate year 2 class. Each class brings a unique perspective and energy. Residents come together from different backgrounds and life situations. Some residents are single, some are engaged or married, and some are starting or expanding their families. Some residents will have prior careers, others will have graduate degrees or expertise in various fields. They will have different ethnic backgrounds, religious and/or spiritual beliefs, familial upbringings, personalities, and methods of communicating. These differences all are important to consider when developing a mindset of inclusion and camaraderie. As residents start their journey together, it is important to remember that residency is a team endeavor. The principles of teamwork apply directly to residents and are founded on creating a climate of trust and building strong relationships with one another.1 Trust is the foundation of good relationships in the workplace; it allows people to communicate freely and foster the belief that everyone is working for each other’s best interests. Being open and sharing knowledge about networking opportunities, scholarships, and research projects is one way to foster collaboration and trust in residency.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology is a work in progress. In the 2020-2021 dermatology application cycle, only 4.8% of applicants identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 7.8% identified as Black or African American.2 The American Academy of Dermatology took an active role in promoting diversity by creating a task force in 2018 to increase the exposure and recruitment into dermatology of medical students who are underrepresented in medicine.2 As standards for diversity are met in dermatology, we will have the wonderful opportunity to welcome even more diversity into our lives.

Listening, showing curiosity about your co-residents’ lives outside of work, and asking questions can help build respect, friendships, and camaraderie. Ask your co-residents what makes them happy and what their goals are in residency. Finding common goals and cultivating the mindset that you all work together to achieve your goals is key to the success of a residency class. Now that we discussed accepting and welcoming differences, how do you foster camaraderie in a social setting?

Establish a Social Committee

As a class, consider 1 or 2 residents who are always excited to try new activities such as attend restaurant openings, exercise classes, concerts, or movie nights. Consider nominating these co-residents along with one attending to be social chairs of your residency. The social chairs should meet and establish at least 1 social event per season, with 4 total for the academic year. There are only 2 rules with social events: (1) they must be held outside of clinic, and (2) everyone should try their best to attend.

Social chairs should try to prioritize a location-specific event that allows the residents who are not from the area to experience something local, which can be anything from apple picking at an orchard in the fall to beach volleyball in the summer. Planning these parties gives everyone an event to look forward to and a chance to spend time together and grow closer. The memories and inside jokes that arise from these outings are invaluable and increase joy inside and outside of clinic.

Utilize Social Media

Another project can be developing a social media account for your program with the approval of your faculty. @unmcdermatology, @uwderm, and @gwdermres can help foster social relationships by establishing a lighthearted space to celebrate the residency’s achievements, new publications, volunteer events, or social gatherings.

Encourage Local and National Conference Attendance

All residents should be encouraged to submit abstracts to local and national conferences and attend with their co-residents. Conferences are peak opportunities to foster camaraderie within residency classes, as they involve a sense of togetherness in the specialty along with the excitement of traveling to a new city and meeting other like-minded individuals. Conferences allow collaboration within the specialty on a national level and foster relationships between residency programs.

In addition, national groups such as the Women’s Dermatologic Society, the Skin of Color Society, and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion task force meet at the national conferences and discuss their next initiatives and projects. Joining a society of your interest can lead to many new networks and relationships you may not have had before. Even if you are not interested in specializing after general dermatology, consider attending a surgery, dermatopathology, or pediatric or cosmetic dermatology conference to learn more about the field from the experts.

Repair Conflicts and Build a Climate of Collaboration

Conflicts and disagreements unfortunately are inevitable during residency. Whether they involve planning vacation times or coordinating call schedules, everyone will not agree on every decision. Learning how to handle and approach conflict with co-residents is of utmost importance to maintaining the hard work you have put in to create trust, camaraderie, and a good social atmosphere. If you are having an issue with a circumstance involving a co-resident, holding a grudge will only sour your experience and the experience of others. Talking to your co-resident directly about your concerns before escalating the issue to a chief resident or faculty member is a great start. Consider asking them about their thought process and show concern for their point of view. Listen to them openly before going into your preferences. It is important to remember that working as a team requires sacrifices, and sometimes you will not be satisfied with the outcome of a conflict.

It also is important to remember that feelings change, and an issue you feel you must address immediately can wait to be addressed at a better time when you have calmed down. You may even find that you decide not to address it at all. At the end of the day, if a conflict cannot be worked out between those involved, consider confiding in a chief resident or a faculty mentor for advice on the next steps to take to resolve the problem. Ultimately, having a good foundation of respect and strong bonds with your residents will help tremendously when conflicts arise.

Final Thoughts

Fostering camaraderie in residency will improve the overall experience and lives of the residents, as well as the experience of the faculty, staff, and patients by the trickle-down effect. Creating a cheerful and fun atmosphere filled with inside jokes and excitement regarding upcoming social events or conferences will certainly result in a time you will cherish for the rest of your life.

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Foster collaboration. In: Kouzes JM, Posner BZ, eds. The Leadership Challenge. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2017:195-217.

- Cooper J, Shao K, Feng H. Racial/ethnic health disparities in dermatology in the United States, part 1: overview of contributing factors and management strategies [published online February 7, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:723-730. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.061

Change is inevitable in residency as well as in life. Every year on July 1, the atmosphere and social structure of residencies change with the new postgraduate year 2 class. Each class brings a unique perspective and energy. Residents come together from different backgrounds and life situations. Some residents are single, some are engaged or married, and some are starting or expanding their families. Some residents will have prior careers, others will have graduate degrees or expertise in various fields. They will have different ethnic backgrounds, religious and/or spiritual beliefs, familial upbringings, personalities, and methods of communicating. These differences all are important to consider when developing a mindset of inclusion and camaraderie. As residents start their journey together, it is important to remember that residency is a team endeavor. The principles of teamwork apply directly to residents and are founded on creating a climate of trust and building strong relationships with one another.1 Trust is the foundation of good relationships in the workplace; it allows people to communicate freely and foster the belief that everyone is working for each other’s best interests. Being open and sharing knowledge about networking opportunities, scholarships, and research projects is one way to foster collaboration and trust in residency.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology is a work in progress. In the 2020-2021 dermatology application cycle, only 4.8% of applicants identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 7.8% identified as Black or African American.2 The American Academy of Dermatology took an active role in promoting diversity by creating a task force in 2018 to increase the exposure and recruitment into dermatology of medical students who are underrepresented in medicine.2 As standards for diversity are met in dermatology, we will have the wonderful opportunity to welcome even more diversity into our lives.

Listening, showing curiosity about your co-residents’ lives outside of work, and asking questions can help build respect, friendships, and camaraderie. Ask your co-residents what makes them happy and what their goals are in residency. Finding common goals and cultivating the mindset that you all work together to achieve your goals is key to the success of a residency class. Now that we discussed accepting and welcoming differences, how do you foster camaraderie in a social setting?

Establish a Social Committee

As a class, consider 1 or 2 residents who are always excited to try new activities such as attend restaurant openings, exercise classes, concerts, or movie nights. Consider nominating these co-residents along with one attending to be social chairs of your residency. The social chairs should meet and establish at least 1 social event per season, with 4 total for the academic year. There are only 2 rules with social events: (1) they must be held outside of clinic, and (2) everyone should try their best to attend.

Social chairs should try to prioritize a location-specific event that allows the residents who are not from the area to experience something local, which can be anything from apple picking at an orchard in the fall to beach volleyball in the summer. Planning these parties gives everyone an event to look forward to and a chance to spend time together and grow closer. The memories and inside jokes that arise from these outings are invaluable and increase joy inside and outside of clinic.

Utilize Social Media

Another project can be developing a social media account for your program with the approval of your faculty. @unmcdermatology, @uwderm, and @gwdermres can help foster social relationships by establishing a lighthearted space to celebrate the residency’s achievements, new publications, volunteer events, or social gatherings.

Encourage Local and National Conference Attendance

All residents should be encouraged to submit abstracts to local and national conferences and attend with their co-residents. Conferences are peak opportunities to foster camaraderie within residency classes, as they involve a sense of togetherness in the specialty along with the excitement of traveling to a new city and meeting other like-minded individuals. Conferences allow collaboration within the specialty on a national level and foster relationships between residency programs.

In addition, national groups such as the Women’s Dermatologic Society, the Skin of Color Society, and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion task force meet at the national conferences and discuss their next initiatives and projects. Joining a society of your interest can lead to many new networks and relationships you may not have had before. Even if you are not interested in specializing after general dermatology, consider attending a surgery, dermatopathology, or pediatric or cosmetic dermatology conference to learn more about the field from the experts.

Repair Conflicts and Build a Climate of Collaboration

Conflicts and disagreements unfortunately are inevitable during residency. Whether they involve planning vacation times or coordinating call schedules, everyone will not agree on every decision. Learning how to handle and approach conflict with co-residents is of utmost importance to maintaining the hard work you have put in to create trust, camaraderie, and a good social atmosphere. If you are having an issue with a circumstance involving a co-resident, holding a grudge will only sour your experience and the experience of others. Talking to your co-resident directly about your concerns before escalating the issue to a chief resident or faculty member is a great start. Consider asking them about their thought process and show concern for their point of view. Listen to them openly before going into your preferences. It is important to remember that working as a team requires sacrifices, and sometimes you will not be satisfied with the outcome of a conflict.

It also is important to remember that feelings change, and an issue you feel you must address immediately can wait to be addressed at a better time when you have calmed down. You may even find that you decide not to address it at all. At the end of the day, if a conflict cannot be worked out between those involved, consider confiding in a chief resident or a faculty mentor for advice on the next steps to take to resolve the problem. Ultimately, having a good foundation of respect and strong bonds with your residents will help tremendously when conflicts arise.

Final Thoughts

Fostering camaraderie in residency will improve the overall experience and lives of the residents, as well as the experience of the faculty, staff, and patients by the trickle-down effect. Creating a cheerful and fun atmosphere filled with inside jokes and excitement regarding upcoming social events or conferences will certainly result in a time you will cherish for the rest of your life.

Change is inevitable in residency as well as in life. Every year on July 1, the atmosphere and social structure of residencies change with the new postgraduate year 2 class. Each class brings a unique perspective and energy. Residents come together from different backgrounds and life situations. Some residents are single, some are engaged or married, and some are starting or expanding their families. Some residents will have prior careers, others will have graduate degrees or expertise in various fields. They will have different ethnic backgrounds, religious and/or spiritual beliefs, familial upbringings, personalities, and methods of communicating. These differences all are important to consider when developing a mindset of inclusion and camaraderie. As residents start their journey together, it is important to remember that residency is a team endeavor. The principles of teamwork apply directly to residents and are founded on creating a climate of trust and building strong relationships with one another.1 Trust is the foundation of good relationships in the workplace; it allows people to communicate freely and foster the belief that everyone is working for each other’s best interests. Being open and sharing knowledge about networking opportunities, scholarships, and research projects is one way to foster collaboration and trust in residency.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology is a work in progress. In the 2020-2021 dermatology application cycle, only 4.8% of applicants identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 7.8% identified as Black or African American.2 The American Academy of Dermatology took an active role in promoting diversity by creating a task force in 2018 to increase the exposure and recruitment into dermatology of medical students who are underrepresented in medicine.2 As standards for diversity are met in dermatology, we will have the wonderful opportunity to welcome even more diversity into our lives.

Listening, showing curiosity about your co-residents’ lives outside of work, and asking questions can help build respect, friendships, and camaraderie. Ask your co-residents what makes them happy and what their goals are in residency. Finding common goals and cultivating the mindset that you all work together to achieve your goals is key to the success of a residency class. Now that we discussed accepting and welcoming differences, how do you foster camaraderie in a social setting?

Establish a Social Committee

As a class, consider 1 or 2 residents who are always excited to try new activities such as attend restaurant openings, exercise classes, concerts, or movie nights. Consider nominating these co-residents along with one attending to be social chairs of your residency. The social chairs should meet and establish at least 1 social event per season, with 4 total for the academic year. There are only 2 rules with social events: (1) they must be held outside of clinic, and (2) everyone should try their best to attend.

Social chairs should try to prioritize a location-specific event that allows the residents who are not from the area to experience something local, which can be anything from apple picking at an orchard in the fall to beach volleyball in the summer. Planning these parties gives everyone an event to look forward to and a chance to spend time together and grow closer. The memories and inside jokes that arise from these outings are invaluable and increase joy inside and outside of clinic.

Utilize Social Media

Another project can be developing a social media account for your program with the approval of your faculty. @unmcdermatology, @uwderm, and @gwdermres can help foster social relationships by establishing a lighthearted space to celebrate the residency’s achievements, new publications, volunteer events, or social gatherings.

Encourage Local and National Conference Attendance

All residents should be encouraged to submit abstracts to local and national conferences and attend with their co-residents. Conferences are peak opportunities to foster camaraderie within residency classes, as they involve a sense of togetherness in the specialty along with the excitement of traveling to a new city and meeting other like-minded individuals. Conferences allow collaboration within the specialty on a national level and foster relationships between residency programs.

In addition, national groups such as the Women’s Dermatologic Society, the Skin of Color Society, and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion task force meet at the national conferences and discuss their next initiatives and projects. Joining a society of your interest can lead to many new networks and relationships you may not have had before. Even if you are not interested in specializing after general dermatology, consider attending a surgery, dermatopathology, or pediatric or cosmetic dermatology conference to learn more about the field from the experts.

Repair Conflicts and Build a Climate of Collaboration

Conflicts and disagreements unfortunately are inevitable during residency. Whether they involve planning vacation times or coordinating call schedules, everyone will not agree on every decision. Learning how to handle and approach conflict with co-residents is of utmost importance to maintaining the hard work you have put in to create trust, camaraderie, and a good social atmosphere. If you are having an issue with a circumstance involving a co-resident, holding a grudge will only sour your experience and the experience of others. Talking to your co-resident directly about your concerns before escalating the issue to a chief resident or faculty member is a great start. Consider asking them about their thought process and show concern for their point of view. Listen to them openly before going into your preferences. It is important to remember that working as a team requires sacrifices, and sometimes you will not be satisfied with the outcome of a conflict.

It also is important to remember that feelings change, and an issue you feel you must address immediately can wait to be addressed at a better time when you have calmed down. You may even find that you decide not to address it at all. At the end of the day, if a conflict cannot be worked out between those involved, consider confiding in a chief resident or a faculty mentor for advice on the next steps to take to resolve the problem. Ultimately, having a good foundation of respect and strong bonds with your residents will help tremendously when conflicts arise.

Final Thoughts

Fostering camaraderie in residency will improve the overall experience and lives of the residents, as well as the experience of the faculty, staff, and patients by the trickle-down effect. Creating a cheerful and fun atmosphere filled with inside jokes and excitement regarding upcoming social events or conferences will certainly result in a time you will cherish for the rest of your life.

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Foster collaboration. In: Kouzes JM, Posner BZ, eds. The Leadership Challenge. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2017:195-217.

- Cooper J, Shao K, Feng H. Racial/ethnic health disparities in dermatology in the United States, part 1: overview of contributing factors and management strategies [published online February 7, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:723-730. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.061

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Foster collaboration. In: Kouzes JM, Posner BZ, eds. The Leadership Challenge. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2017:195-217.

- Cooper J, Shao K, Feng H. Racial/ethnic health disparities in dermatology in the United States, part 1: overview of contributing factors and management strategies [published online February 7, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:723-730. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.061

Resident Pearls

- Camaraderie in residency is a special dynamic that can be enhanced and fostered in many different ways.

- The relationships among residents should be treated with importance, as some of the friends you make will last a career and/or a lifetime.

- Conflicts inevitably will arise and learning how to handle them effectively can improve the residency experience.

Nail Salon Safety: From Nail Dystrophy to Acrylate Contact Allergies

As residents, it is important to understand the steps of the manicuring process and be able to inform patients on how to maintain optimal nail health while continuing to go to nail salons. Most patients are not aware of the possible allergic, traumatic, and/or infectious complications of manicuring their nails. There are practical steps that can be taken to prevent nail issues, such as avoiding cutting one’s cuticles or using allergen-free nail polishes. These simple fixes can make a big difference in long-term nail health in our patients.

Nail Polish Application Process

The nails are first soaked in a warm soapy solution to soften the nail plate and cuticles.1 Then the nail tips and plates are filed and occasionally are smoothed with a drill. The cuticles are cut with a cuticle cutter. Nail polish—base coat, color enamel, and top coat—is then applied to the nail. Acrylic or sculptured nails and gel and dip manicures are composed of chemical monomers and polymers that harden either at room temperature or through UV or light-emitting diode (LED) exposure. The chemicals in these products can damage nails and cause allergic reactions.

Contact Dermatitis

Approximately 2% of individuals have been found to have allergic or irritant contact dermatitis to nail care products. The top 5 allergens implicated in nail products are (1) 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, (2) methyl methacrylate, (3) ethyl acrylate, (4) ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and (5) tosylamide.2 Methyl methacrylate was banned in 1974 by the US Food and Drug Administration due to reports of severe contact dermatitis, paronychia, and nail dystrophy.3 Due to their potent sensitizing effects, acrylates were named the contact allergen of the year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.3

Acrylates are plastic products formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid.4 Artificial sculptured nails are created by mixing powdered polymethyl methacrylate polymers and liquid ethyl or isobutyl methacrylate monomers and then applying this mixture to the nail plate.5 Gel and powder nails employ a mixture that is similar to acrylic powders, which require UV or LED radiation to polymerize and harden on the nail plate.

Tosylamide, or tosylamide formaldehyde resin, is another potent allergen that promotes adhesion of the enamel to the nail.6 It is important to note that sensitization may develop months to years after using artificial nails.

Clinical features of contact allergy secondary to nail polish can vary. Some patients experience severe periungual dermatitis. Others can present with facial or eyelid dermatitis due to exposure to airborne particles of acrylates or from contact with fingertips bearing acrylic nails.6,7 If inhaled, acrylates also can cause wheezing asthma or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Common Onychodystrophies