User login

Violaceous Nodules on the Hard Palate

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

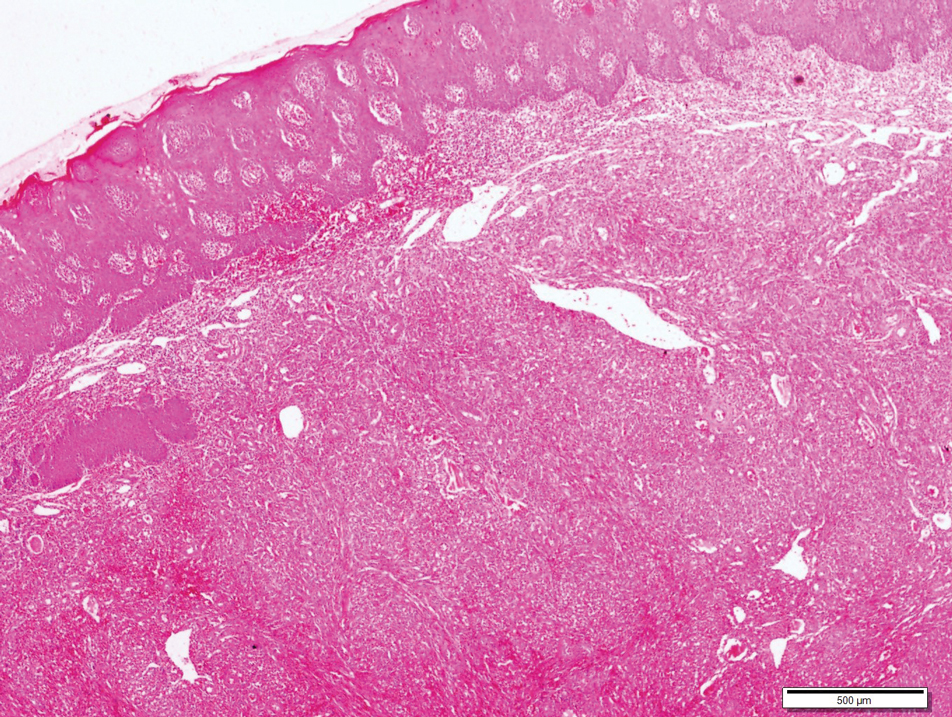

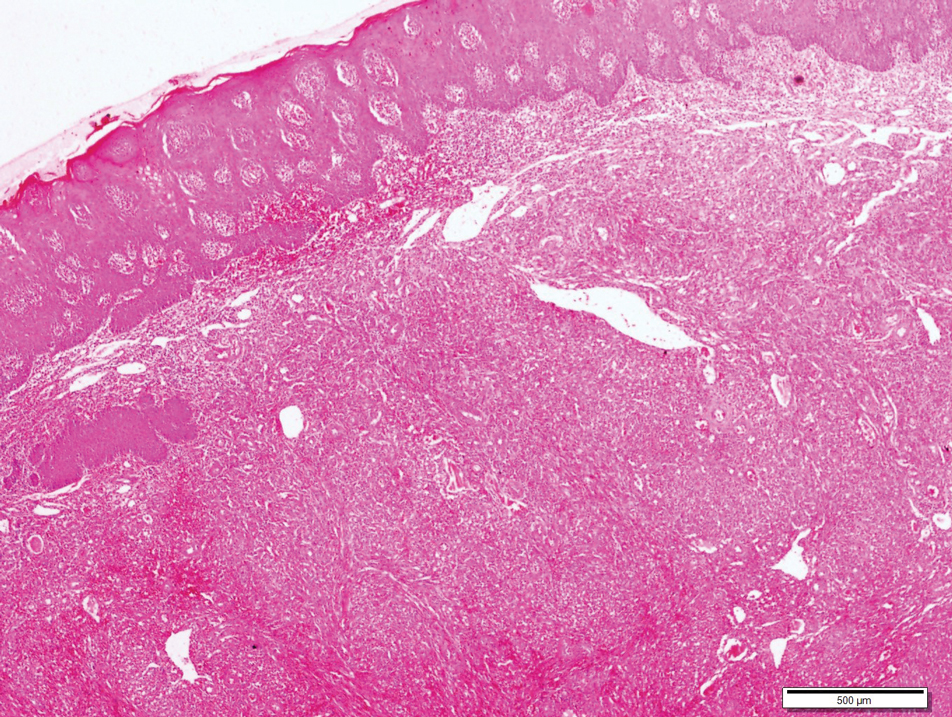

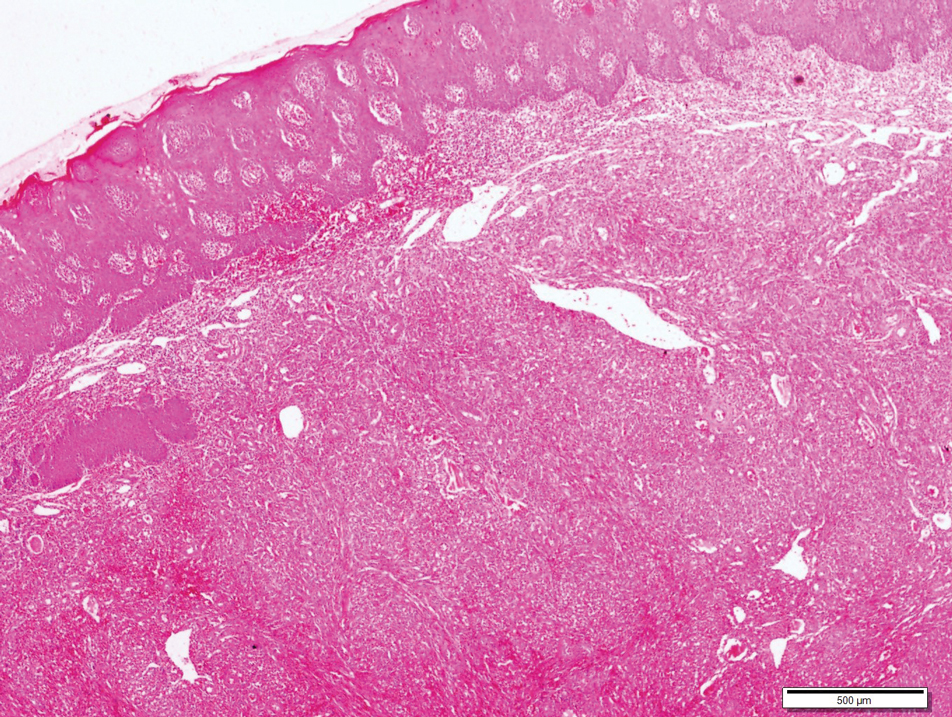

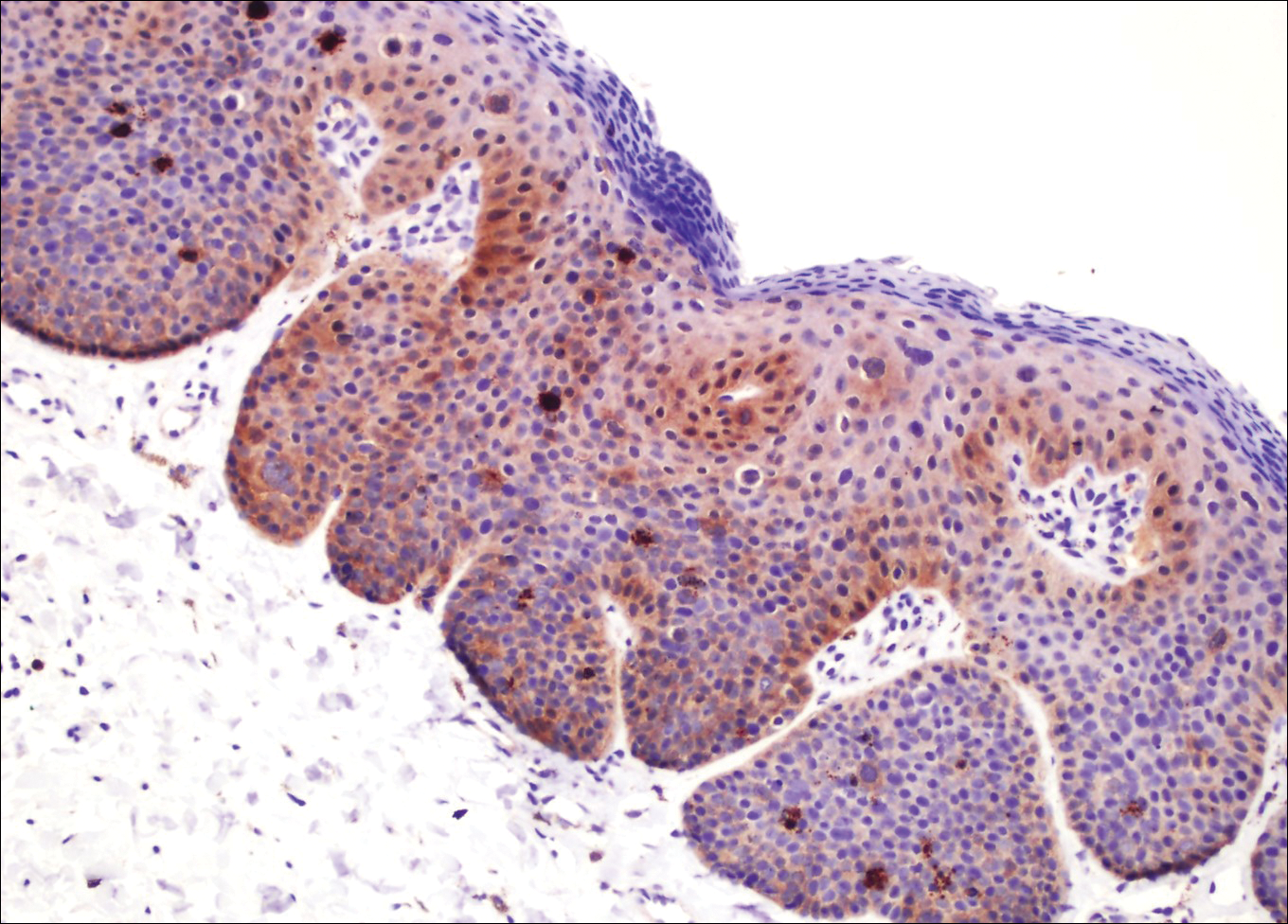

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

A 30-year-old man presented to our outpatient clinic with rapidly growing, ulcerated, violaceous lesions on the hard palate of 4 months' duration. Physical examination revealed approximately 2.0×1.5-cm, centrally ulcerated, violaceous, nodular lesions on the hard palate, as well as a 4-mm pinkish papular lesion on the soft palate.

Brown Papules on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

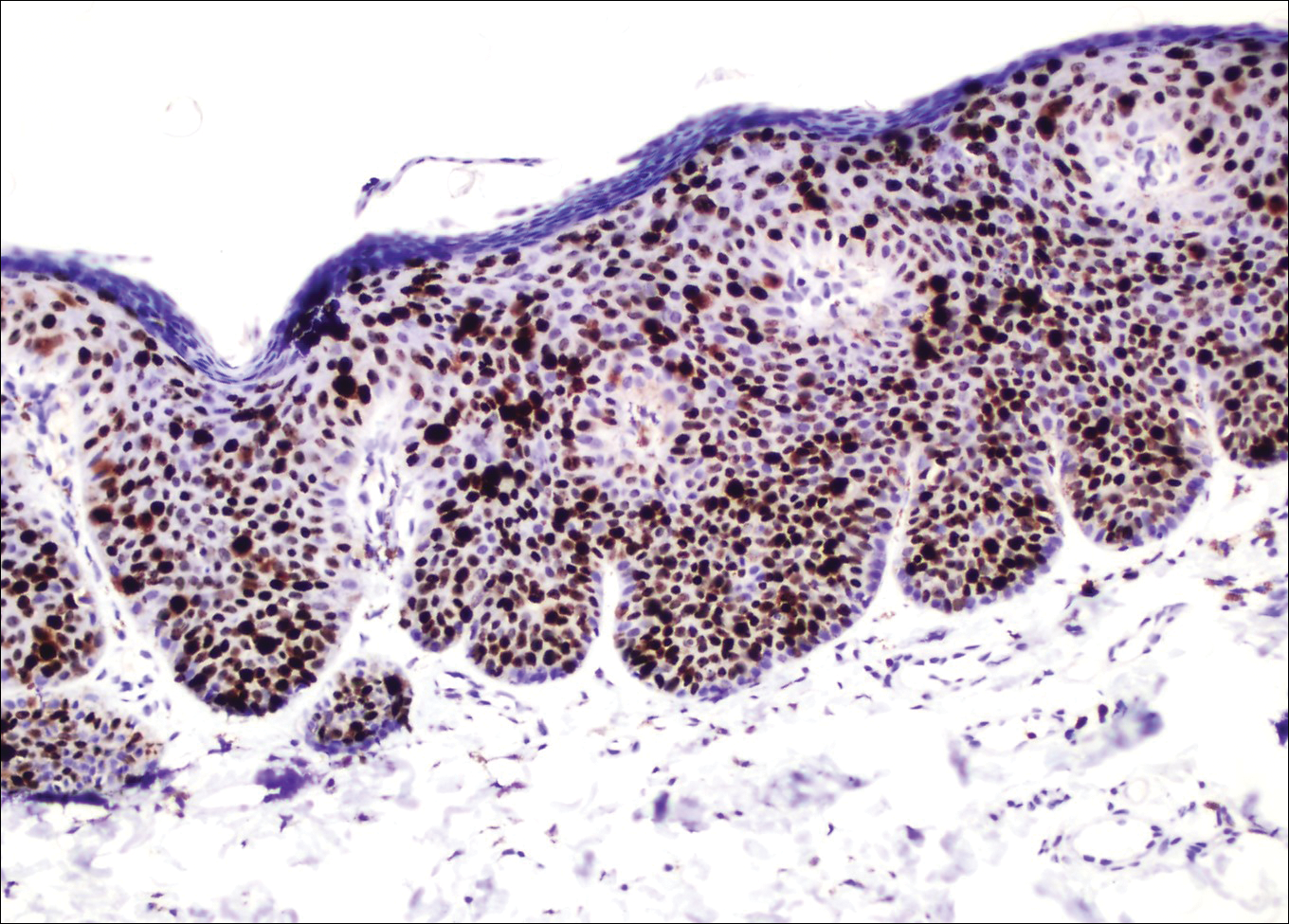

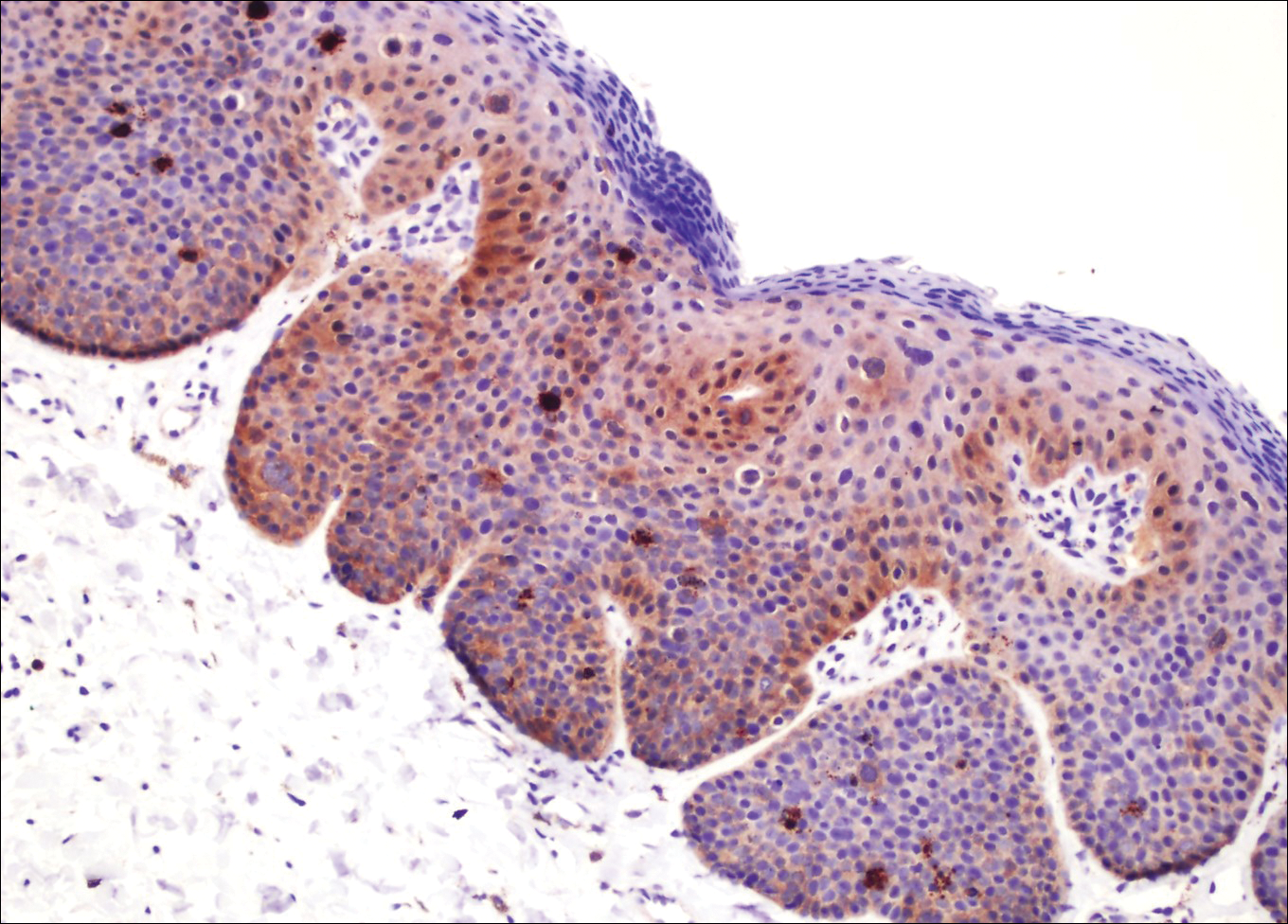

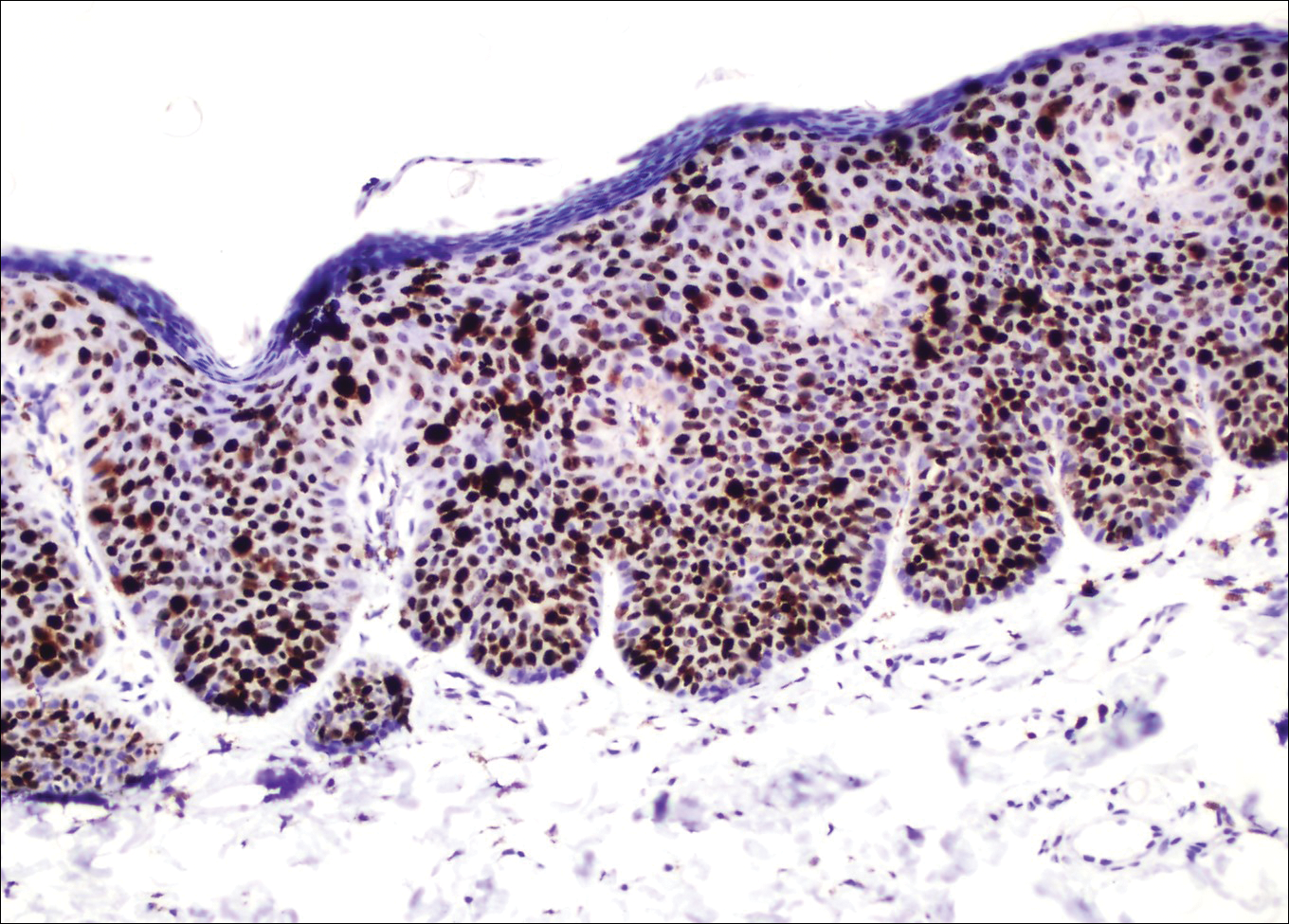

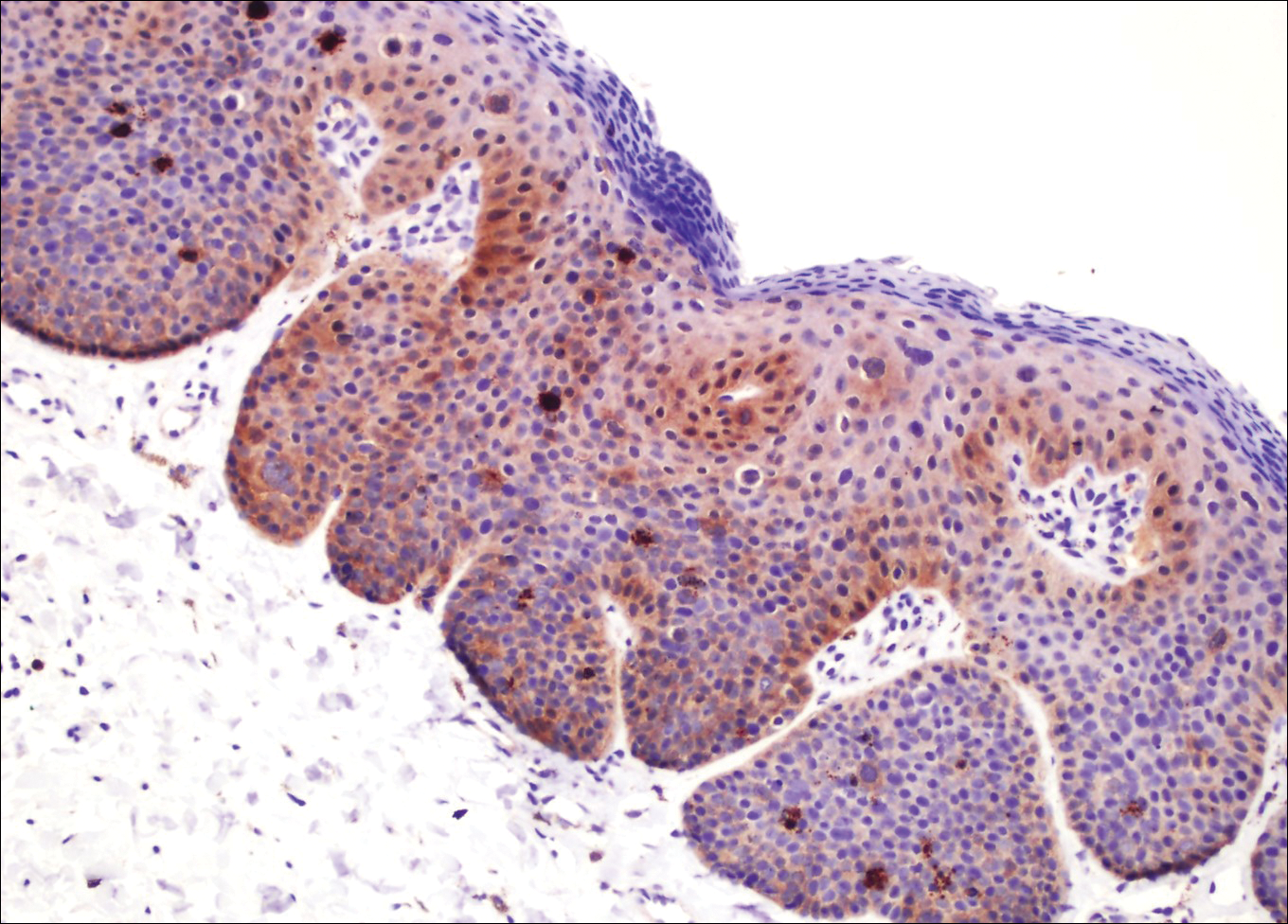

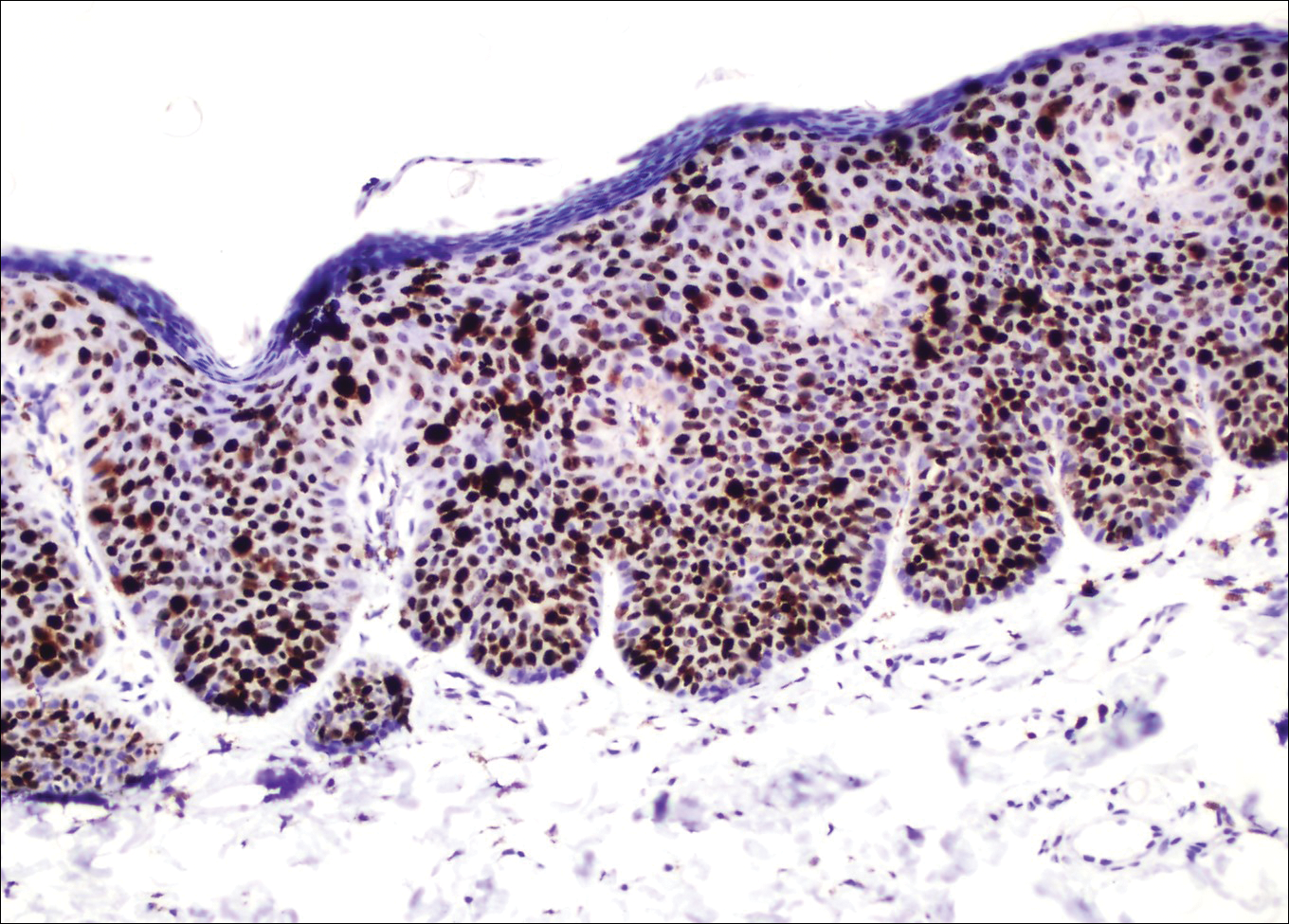

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

A 32-year-old man presented to the outpatient clinic with reddish brown lesions on the penis of 5 months' duration. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple mildly infiltrated, bright reddish brown papules and plaques on the dorsal penis.