User login

Solar Urticaria Treated With Omalizumab

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

Practice Points

- Recurrent solar urticaria can be recalcitrant to treatment.

- Omalizumab may be an effective treatment option for solar urticaria, especially in patients with a concomitant asthma diagnosis.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Perineural Involvement in Nevus Sebaceus

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

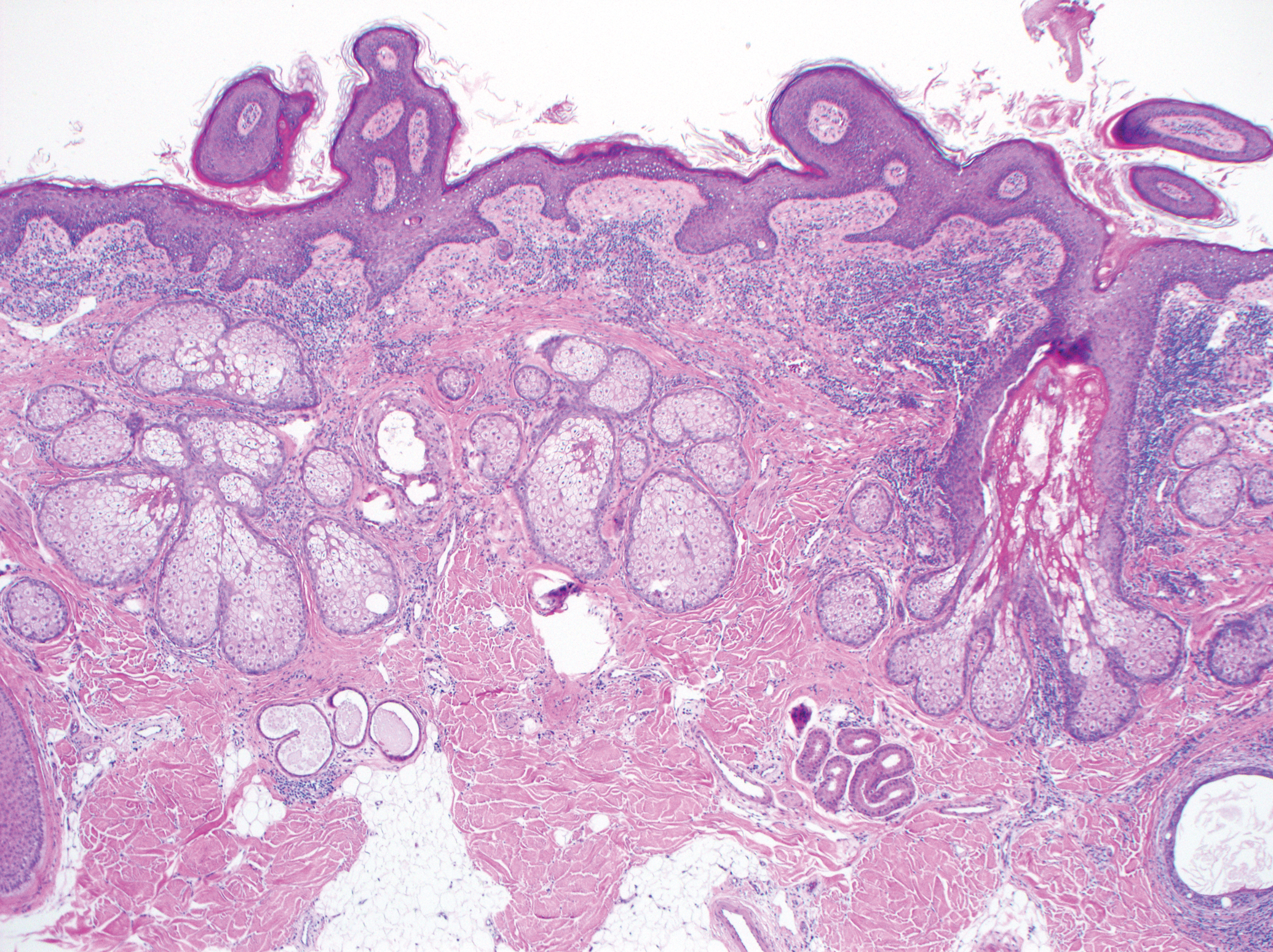

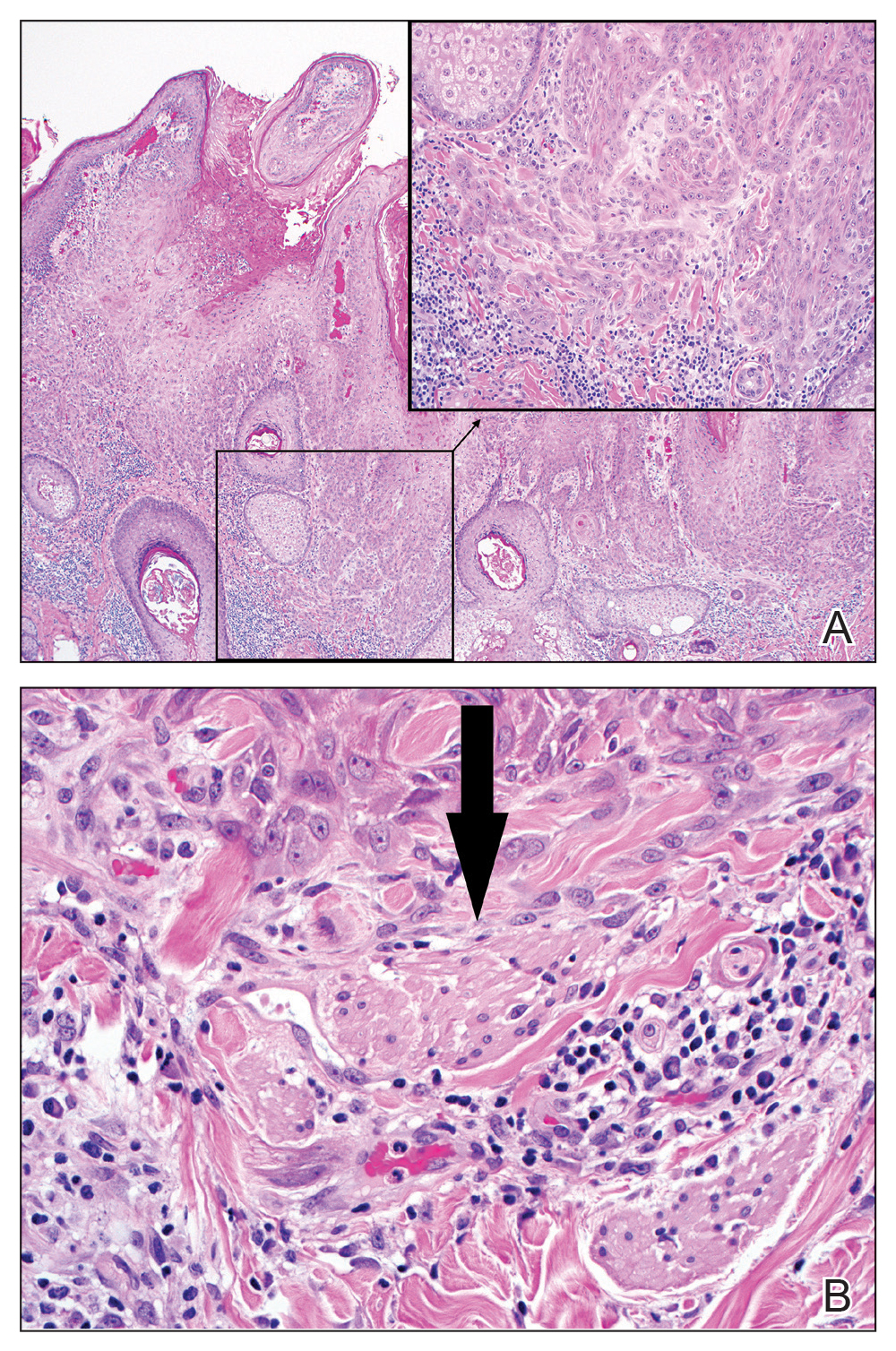

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

Practice Points

- Nevus sebaceus (NS) is frequently found on the scalp and may increase in size during puberty.

- Commonly found additional neoplasms within NS include trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Malignancies are possible but rare.