User login

Blue Nodules on the Forearms in an Active-Duty Military Servicemember

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

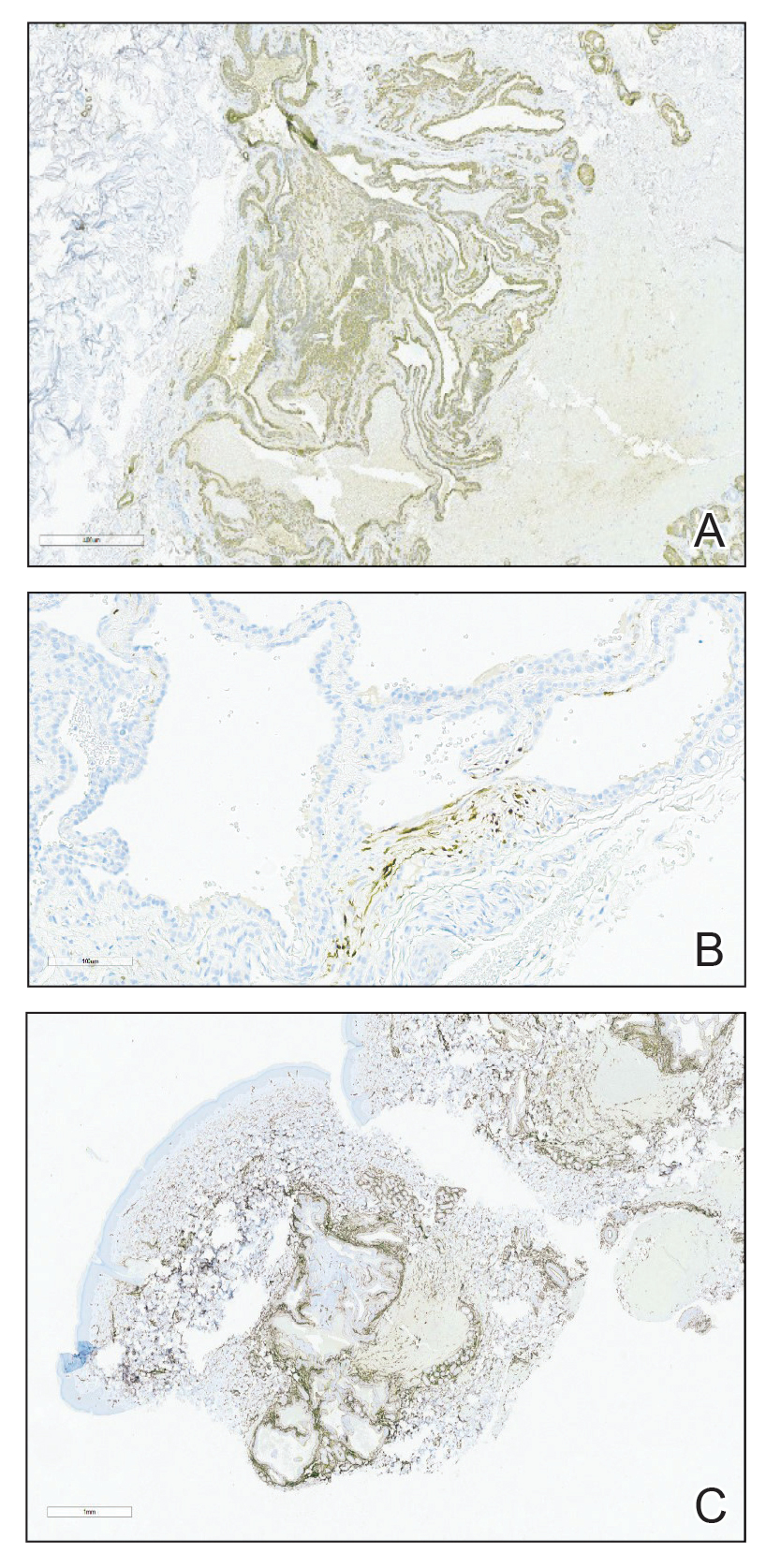

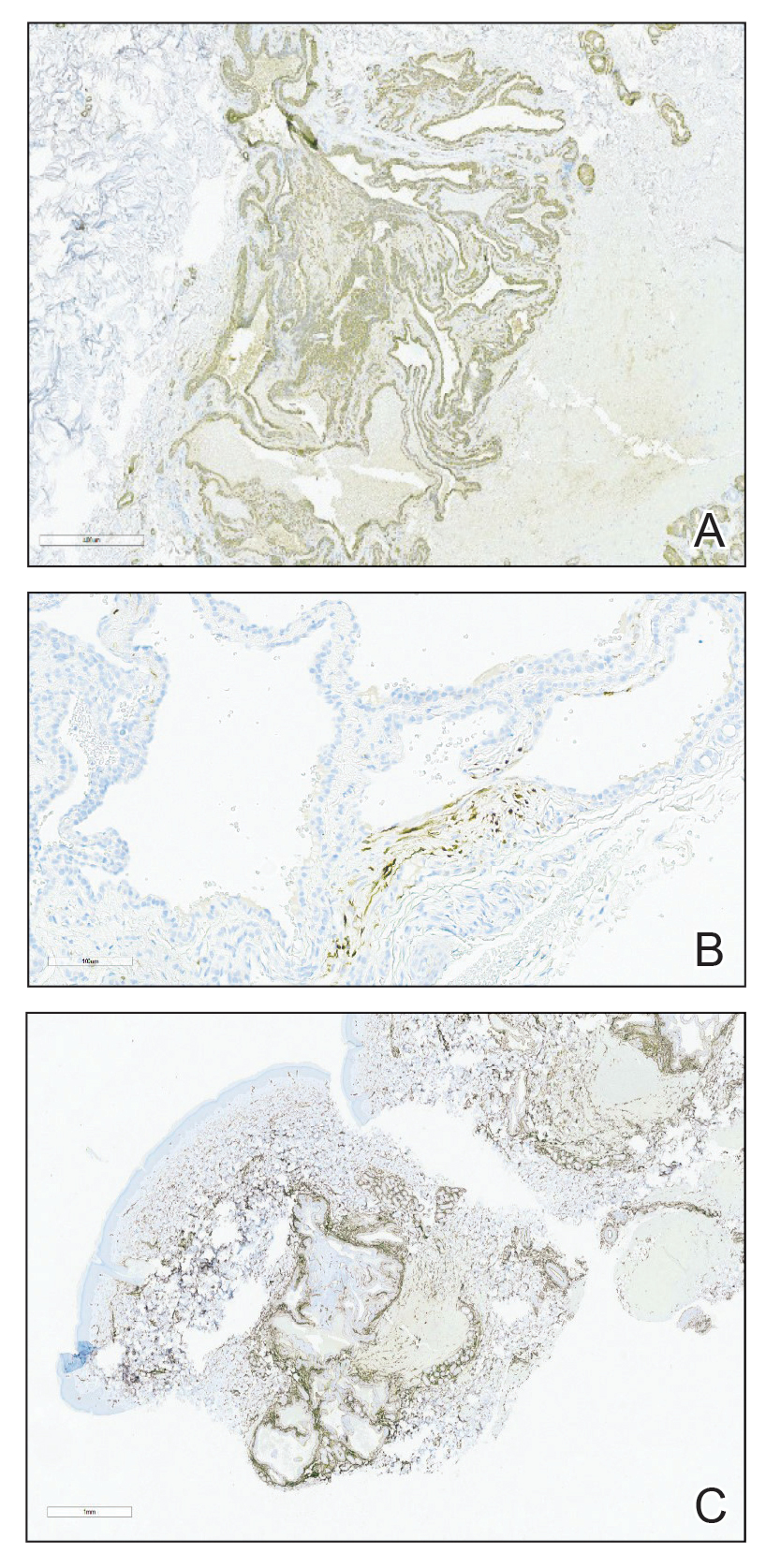

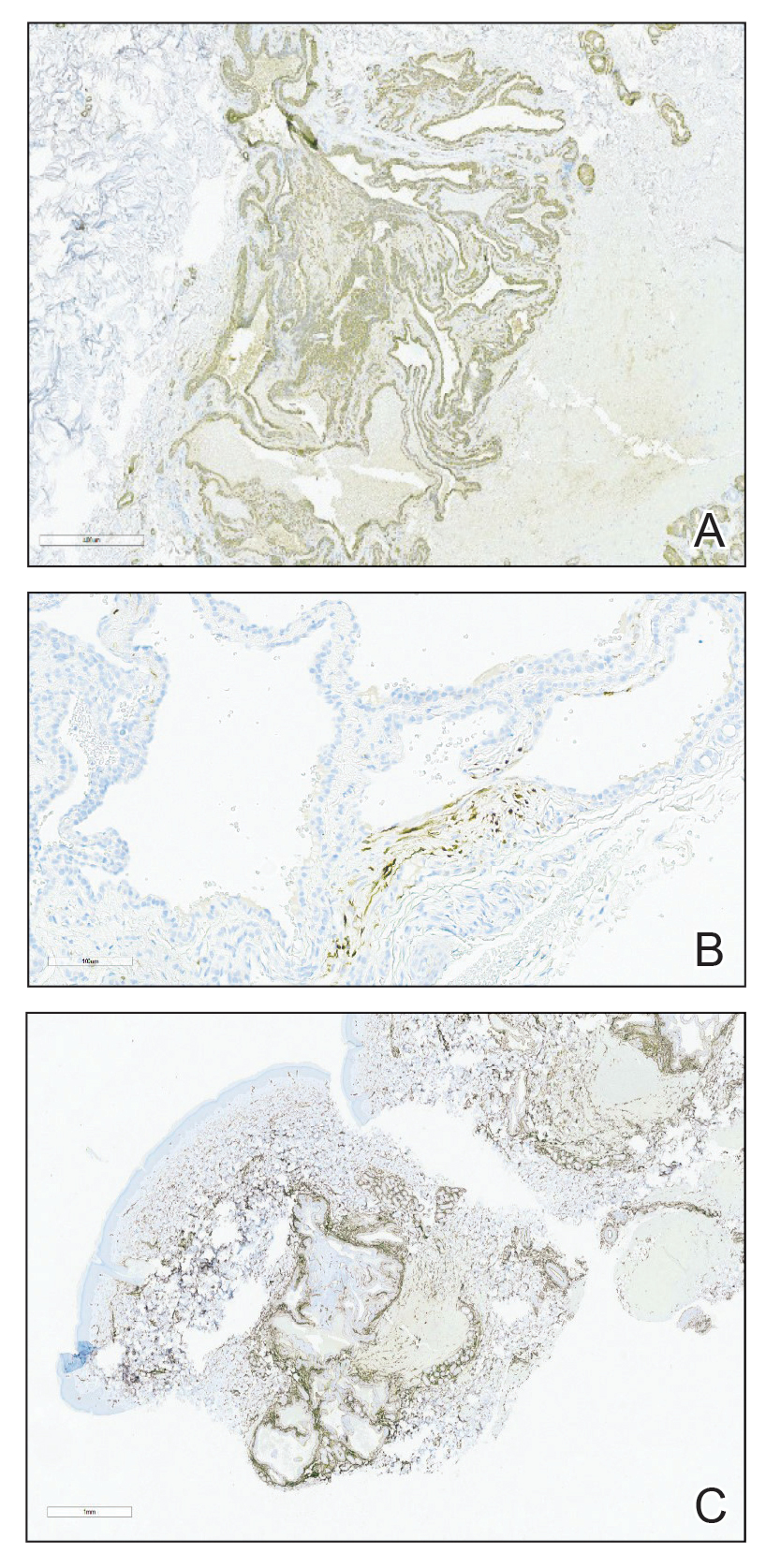

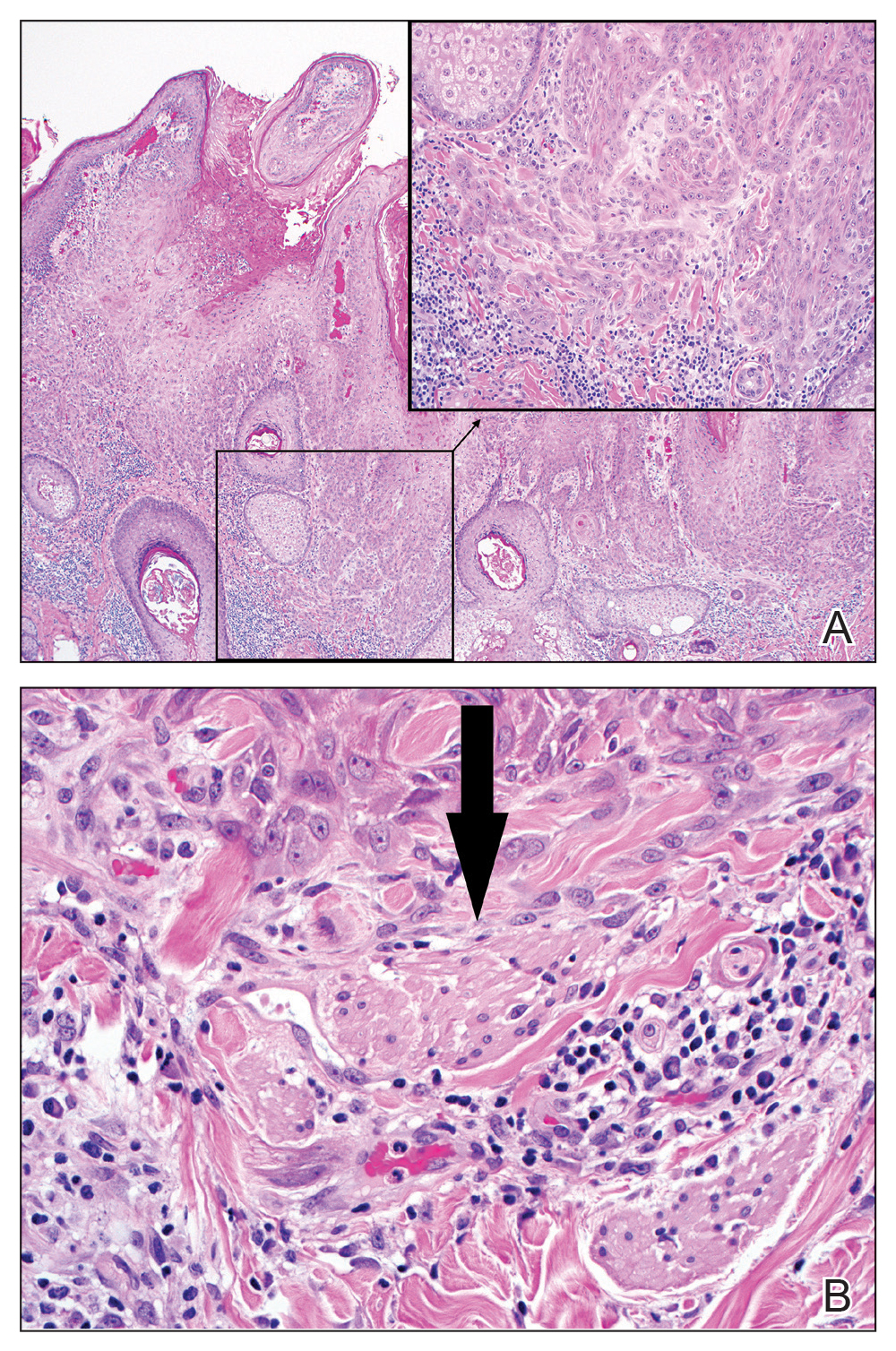

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

A 31-year-old active-duty military servicemember presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of 0.3- to 2-cm, tender, blue nodules on the wrists and forearms. The lesions first appeared on the right volar wrist secondary to a presumed injury sustained approximately 10 years prior to presentation and spread to the proximal forearm as well as the left wrist and forearm. He denied fevers, chills, chest pain, hematochezia, hematuria, or other skin findings. Physical examination revealed blue-violaceous, firm nodules on the right volar wrist and forearm that were tender to palpation. Blue-violaceous, papulonodular lesions on the left volar wrist and dorsal hand were not tender to palpation. A punch biopsy was performed.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Perineural Involvement in Nevus Sebaceus

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

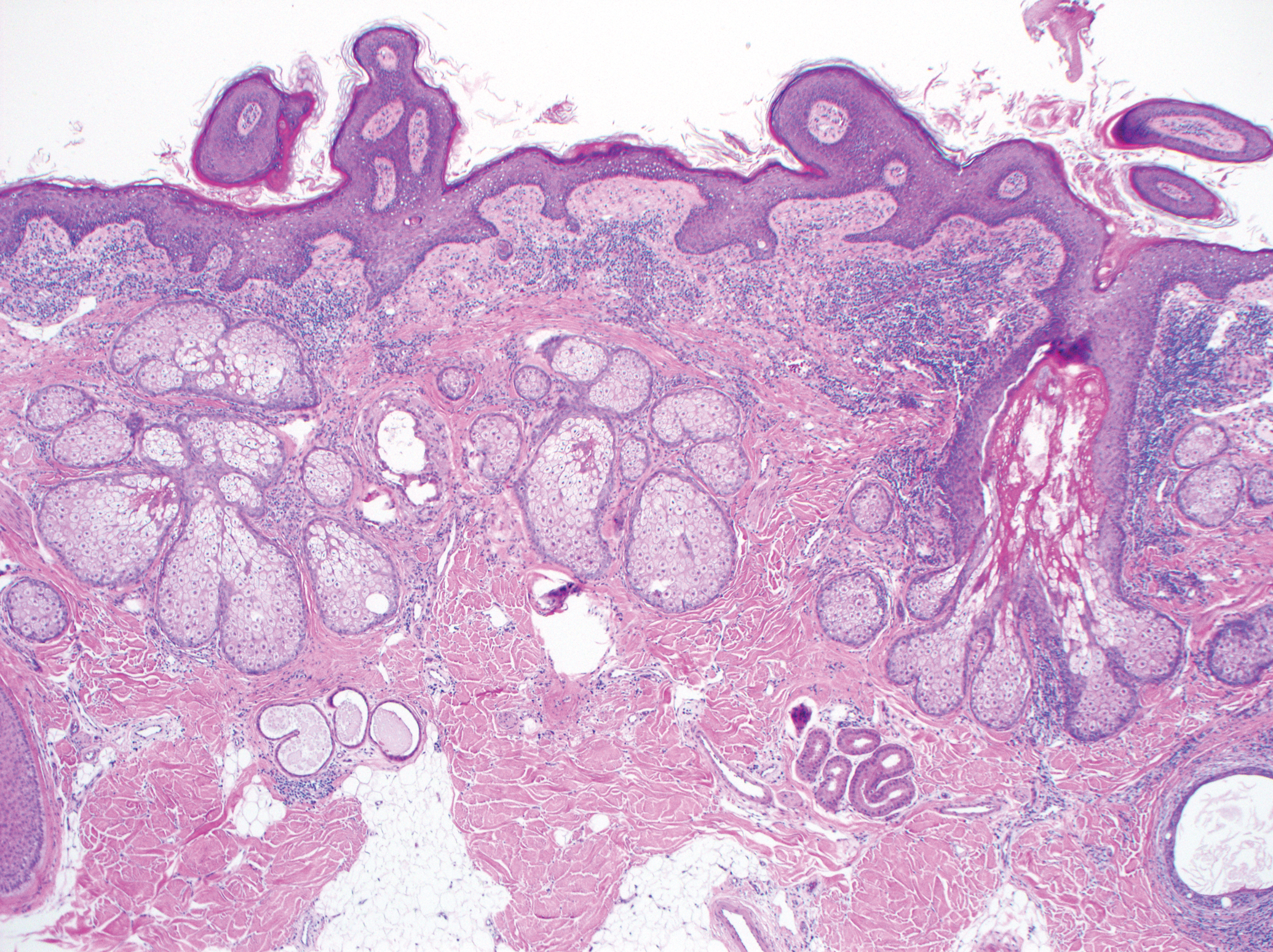

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

Practice Points

- Nevus sebaceus (NS) is frequently found on the scalp and may increase in size during puberty.

- Commonly found additional neoplasms within NS include trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Malignancies are possible but rare.