User login

Slowly Enlarging Nodule on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

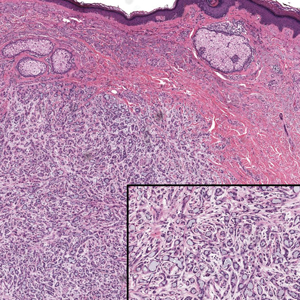

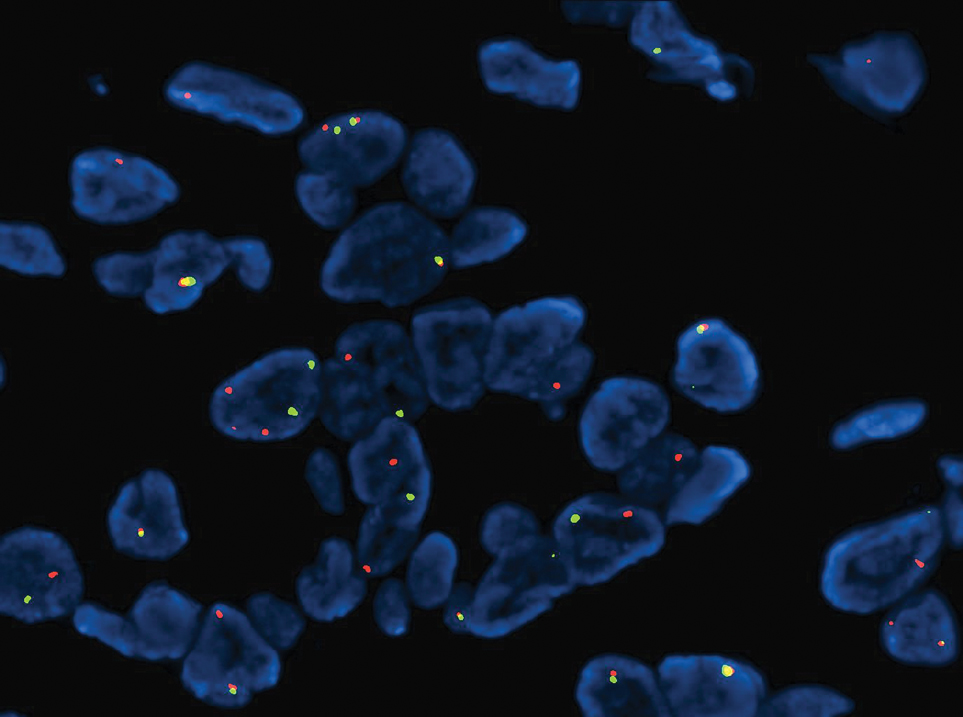

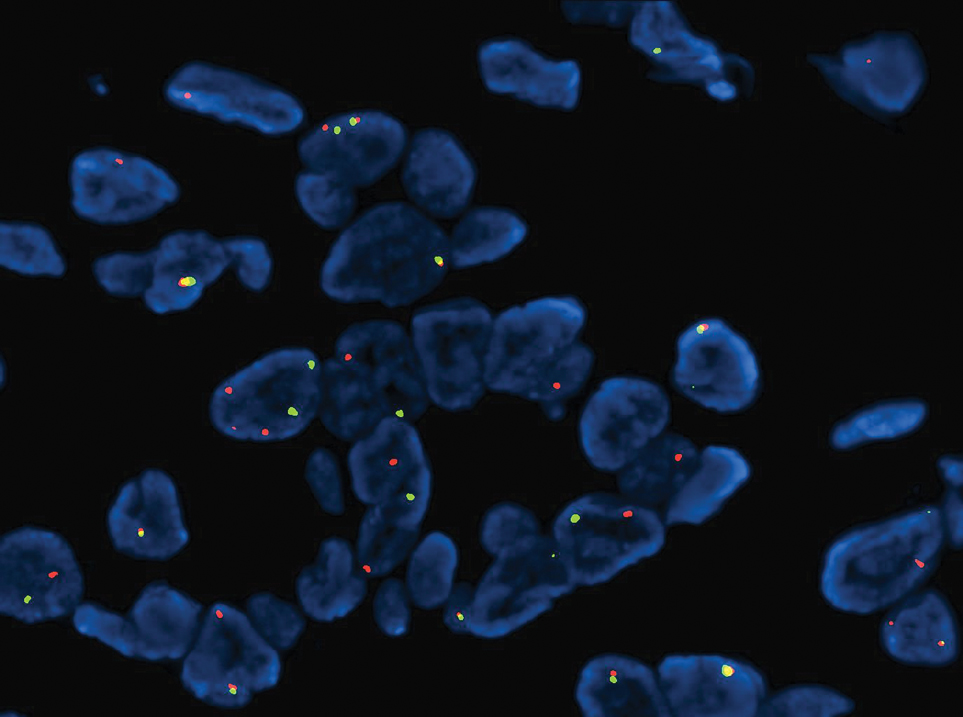

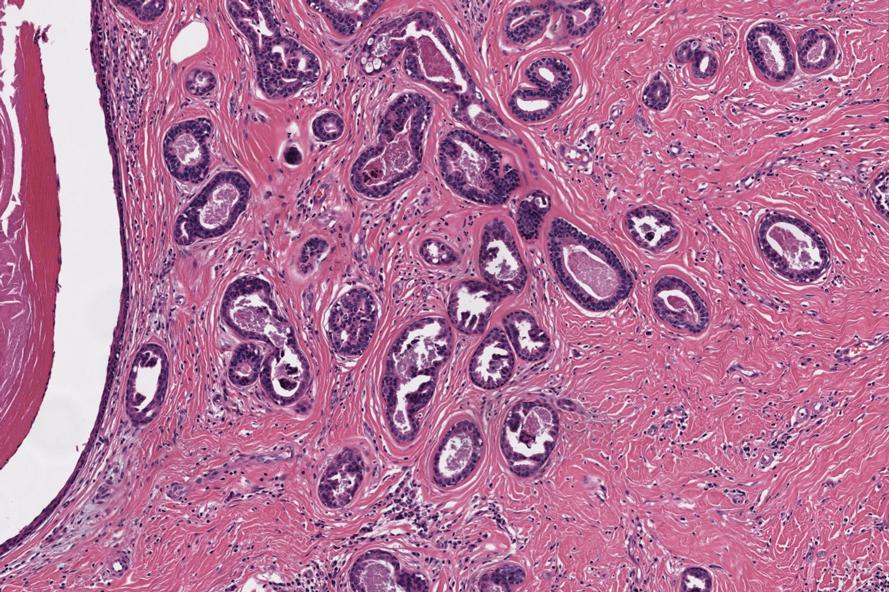

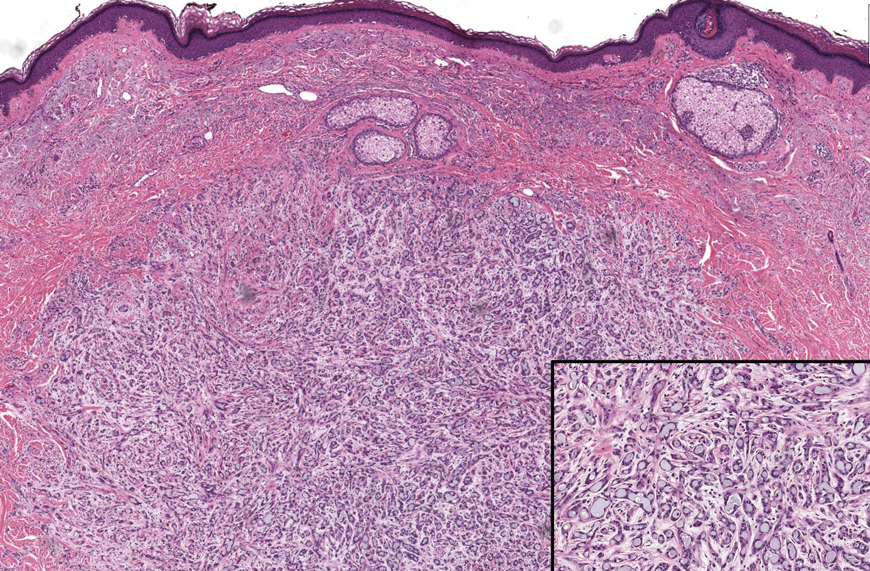

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

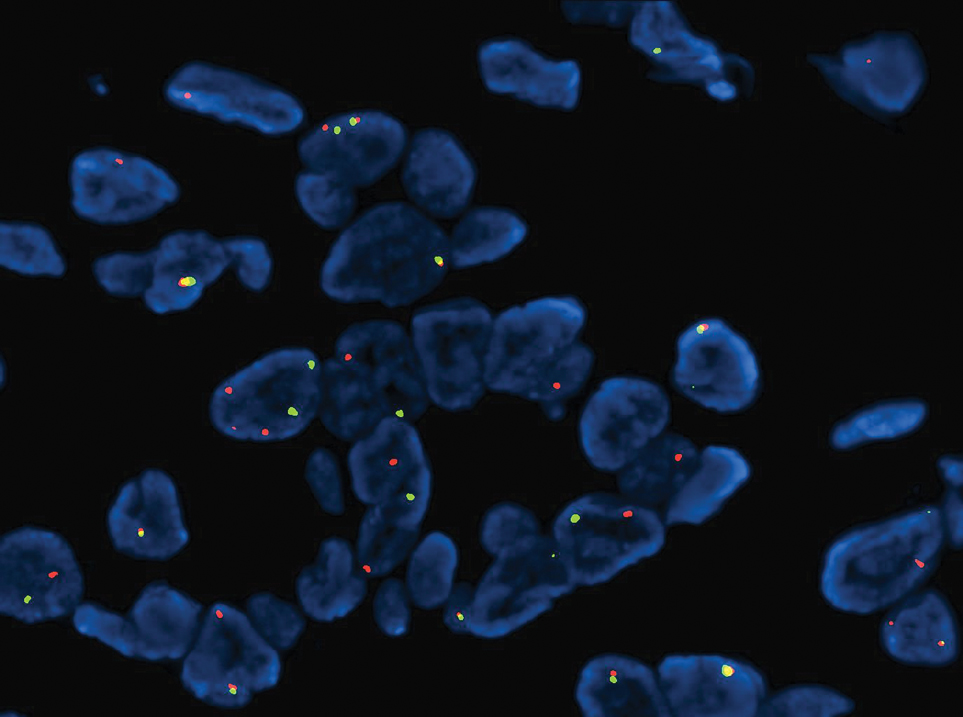

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

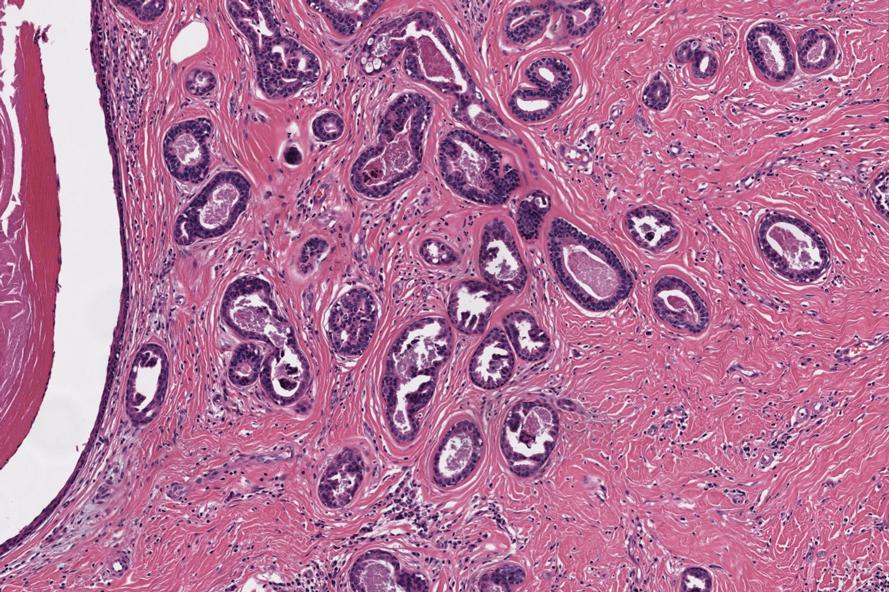

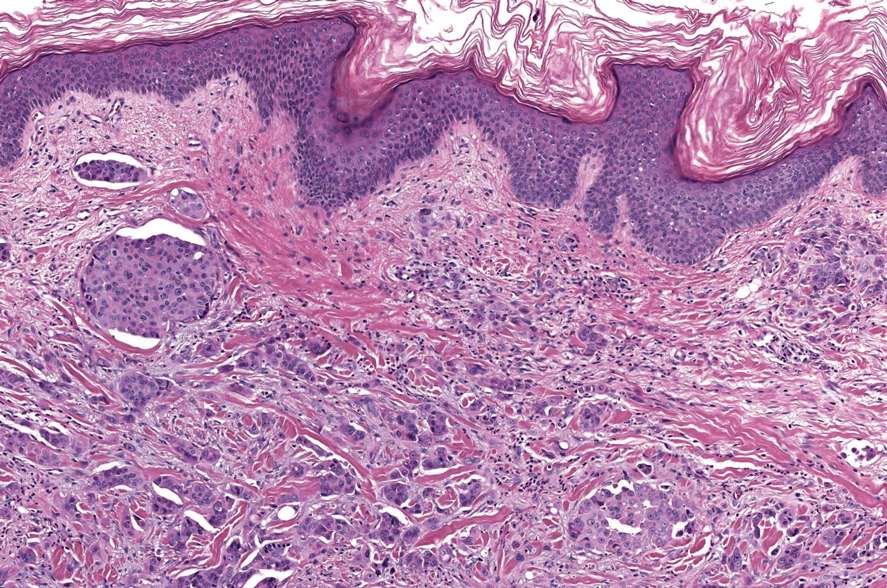

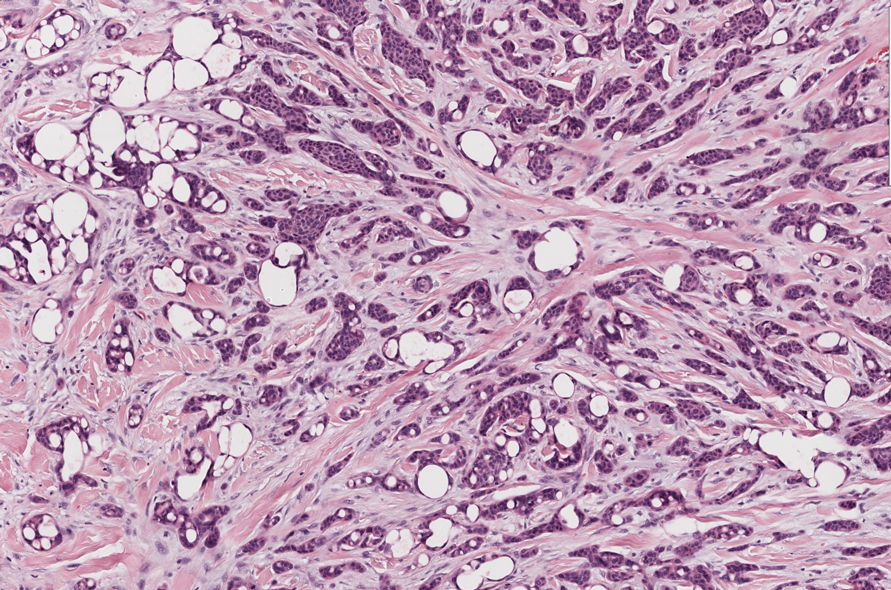

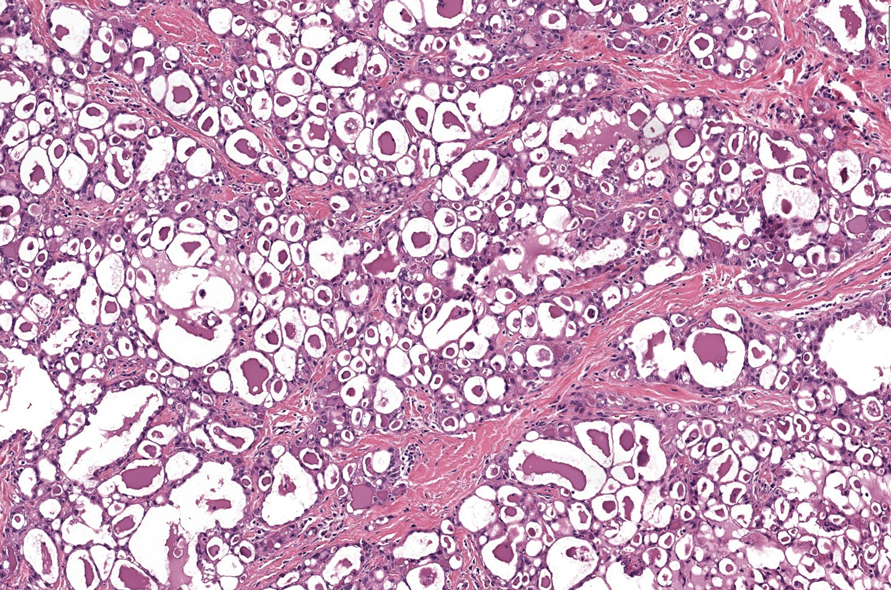

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

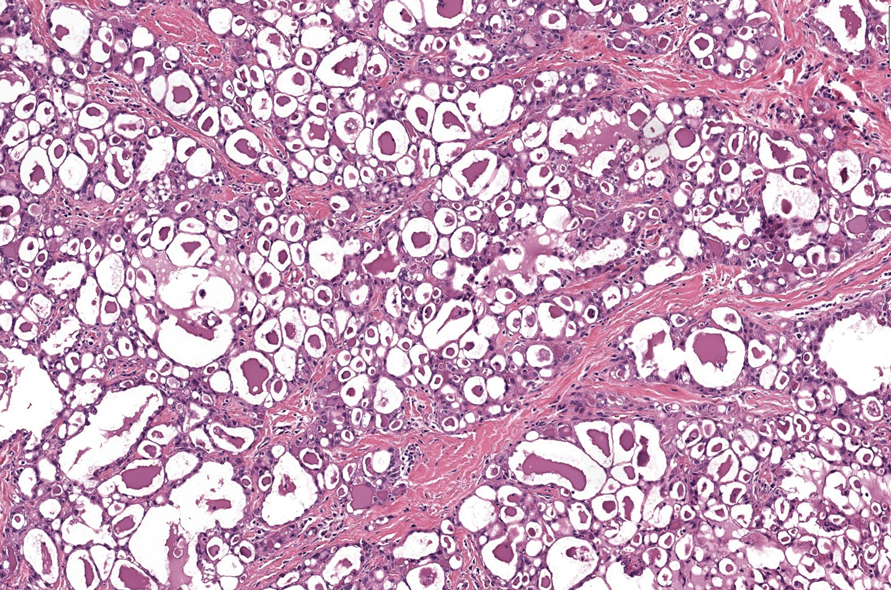

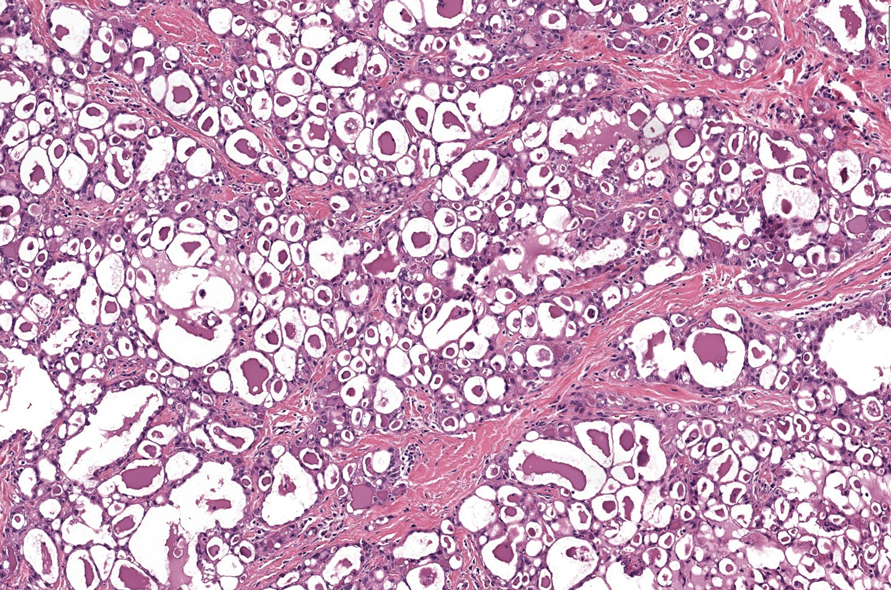

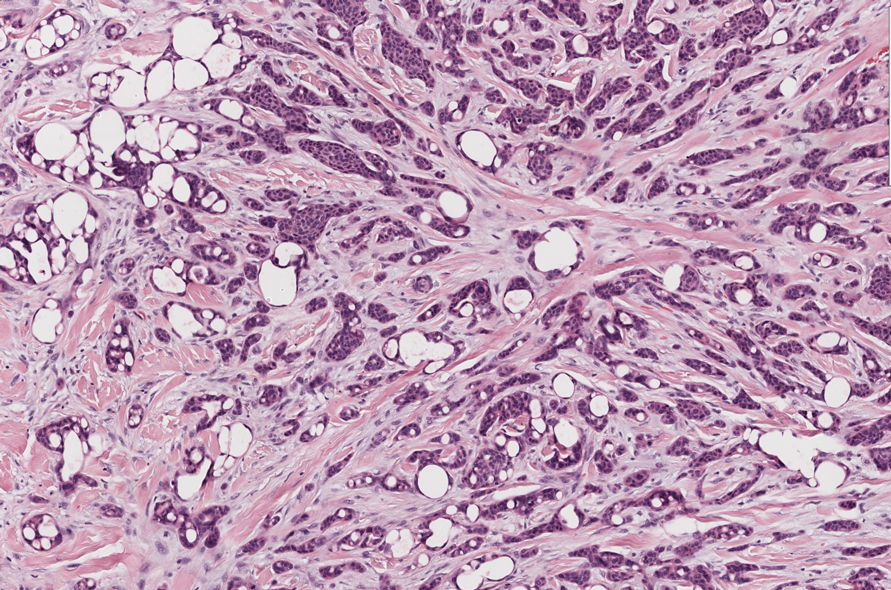

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

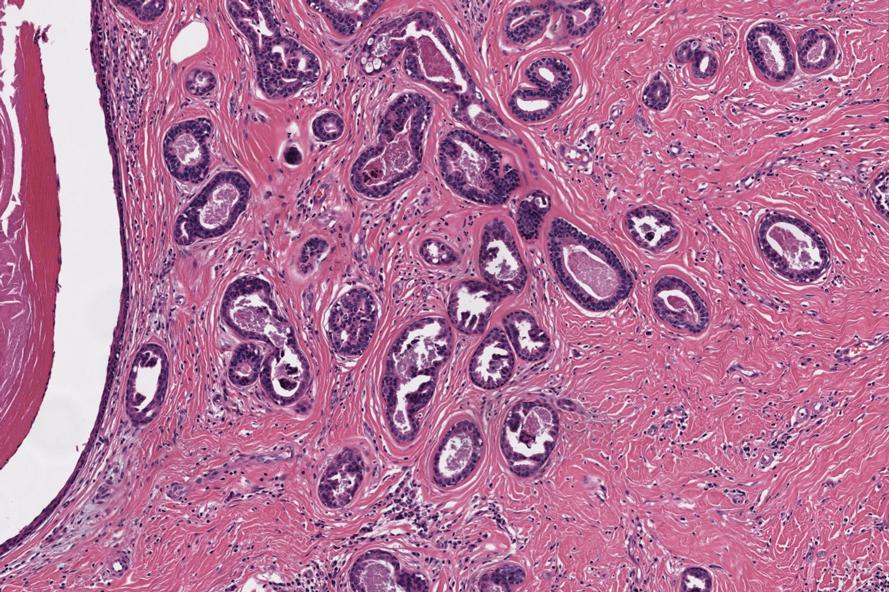

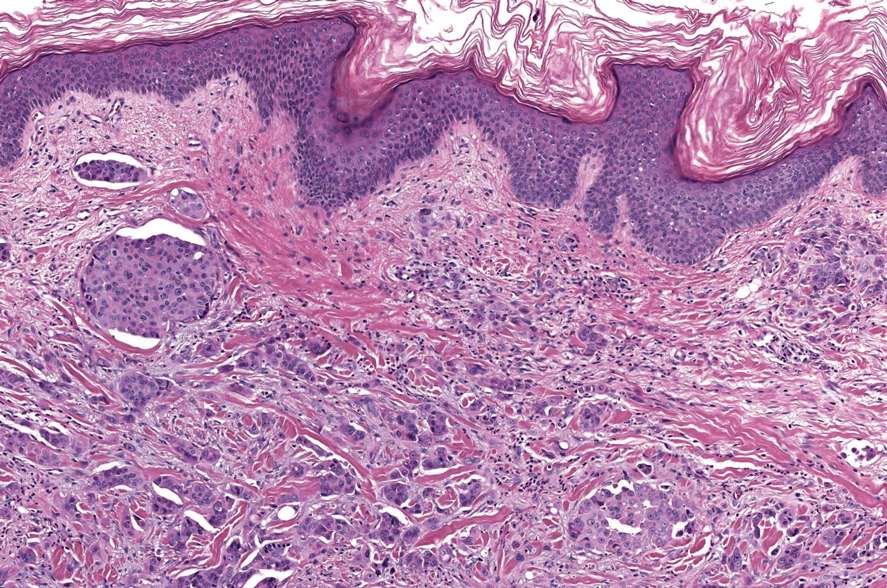

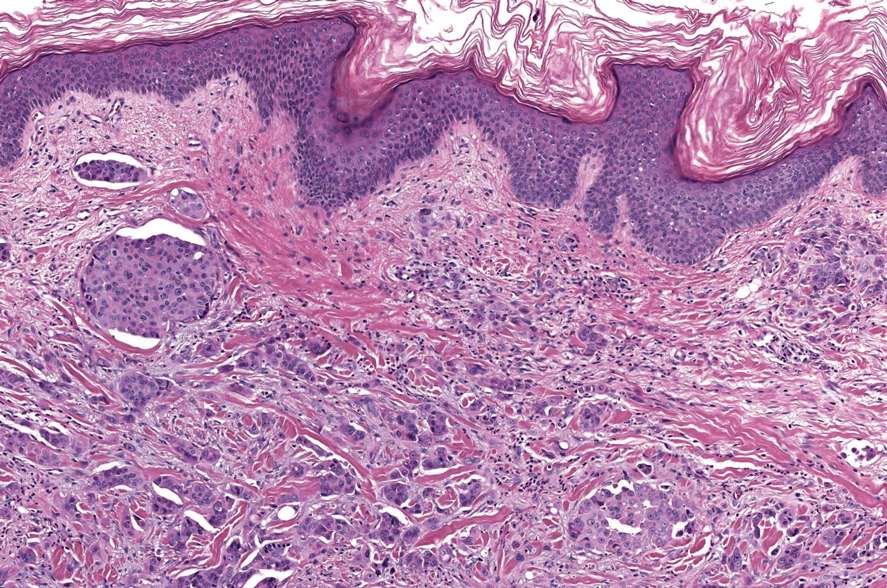

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

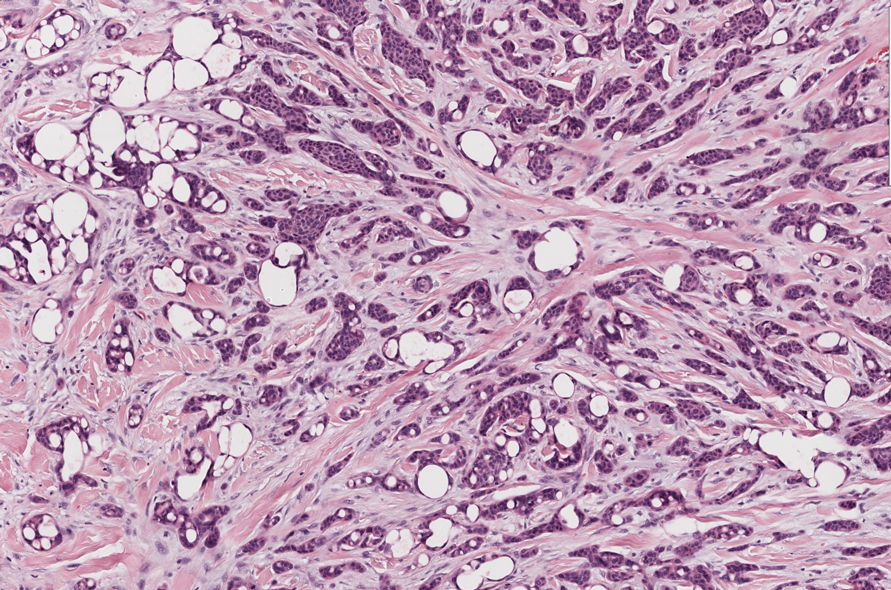

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

A 74-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic nodule on the left neck measuring approximately 2 cm. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Hypopigmented Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in a Hispanic Infant

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

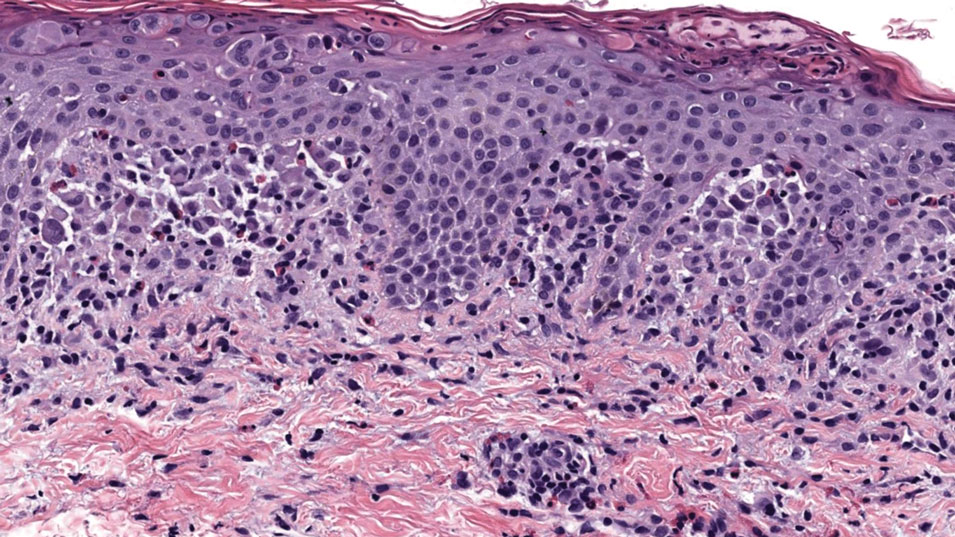

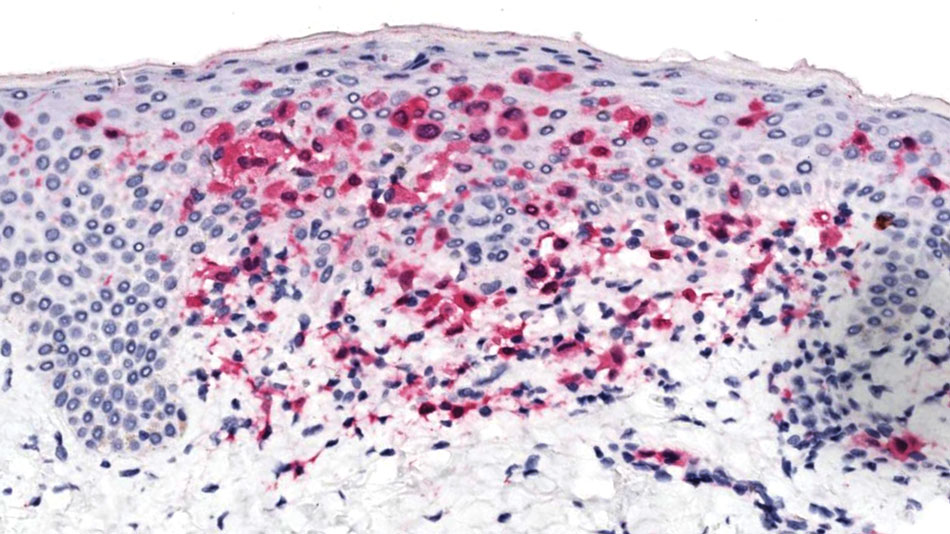

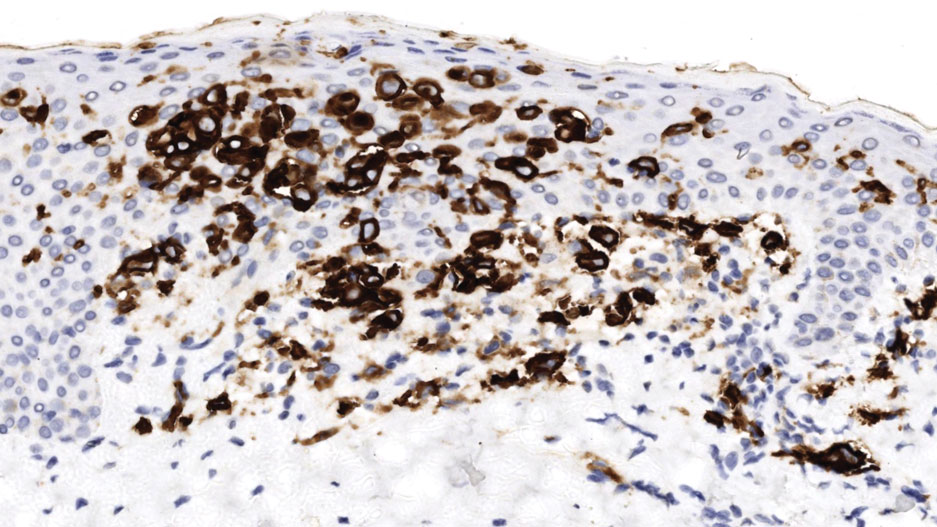

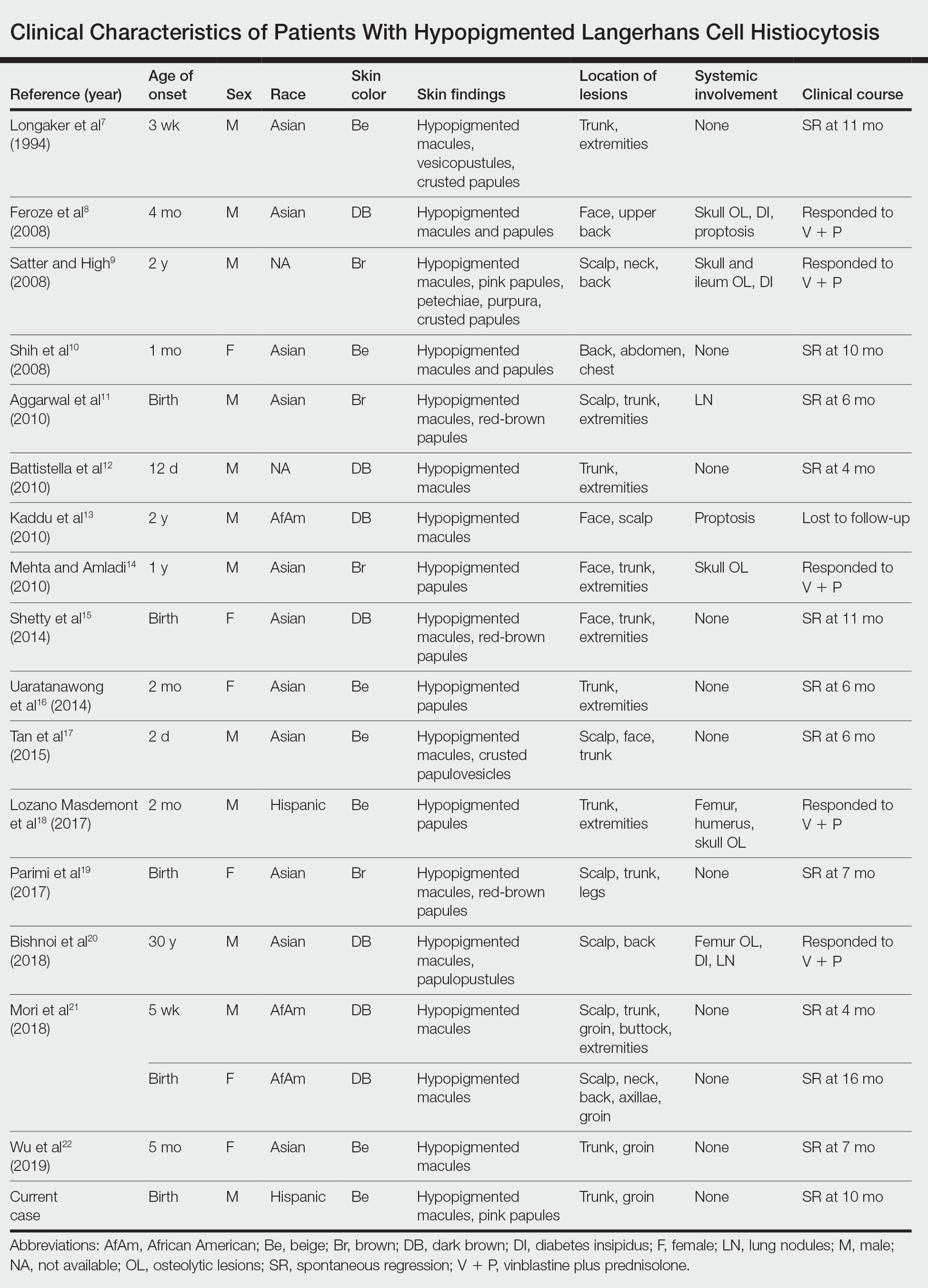

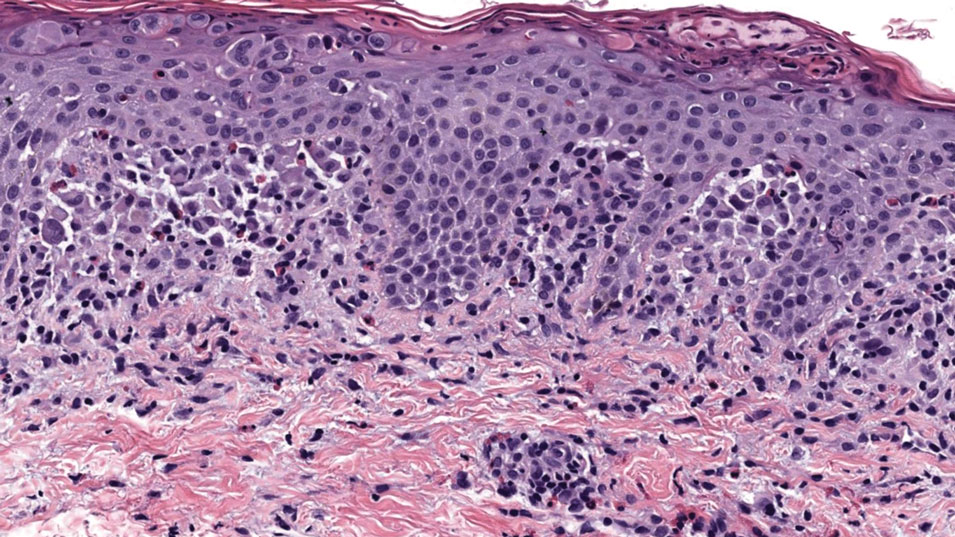

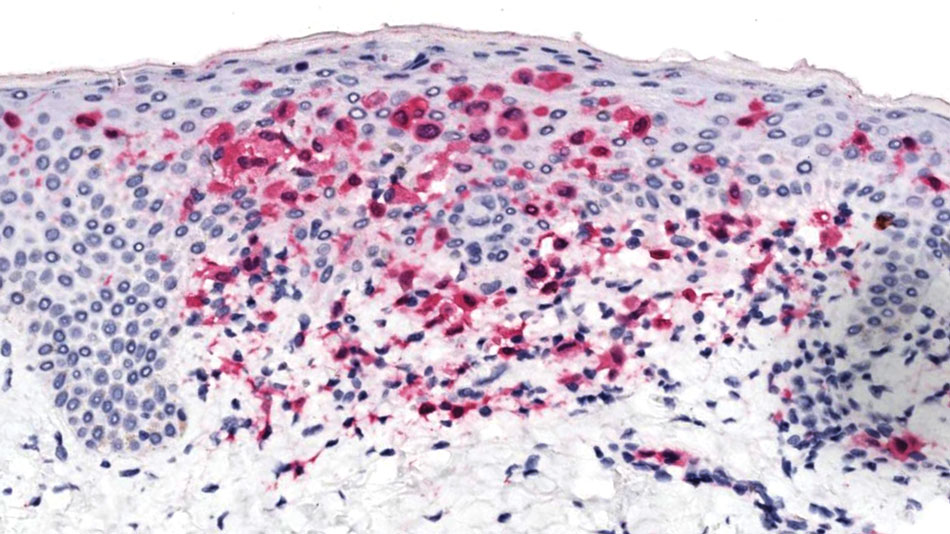

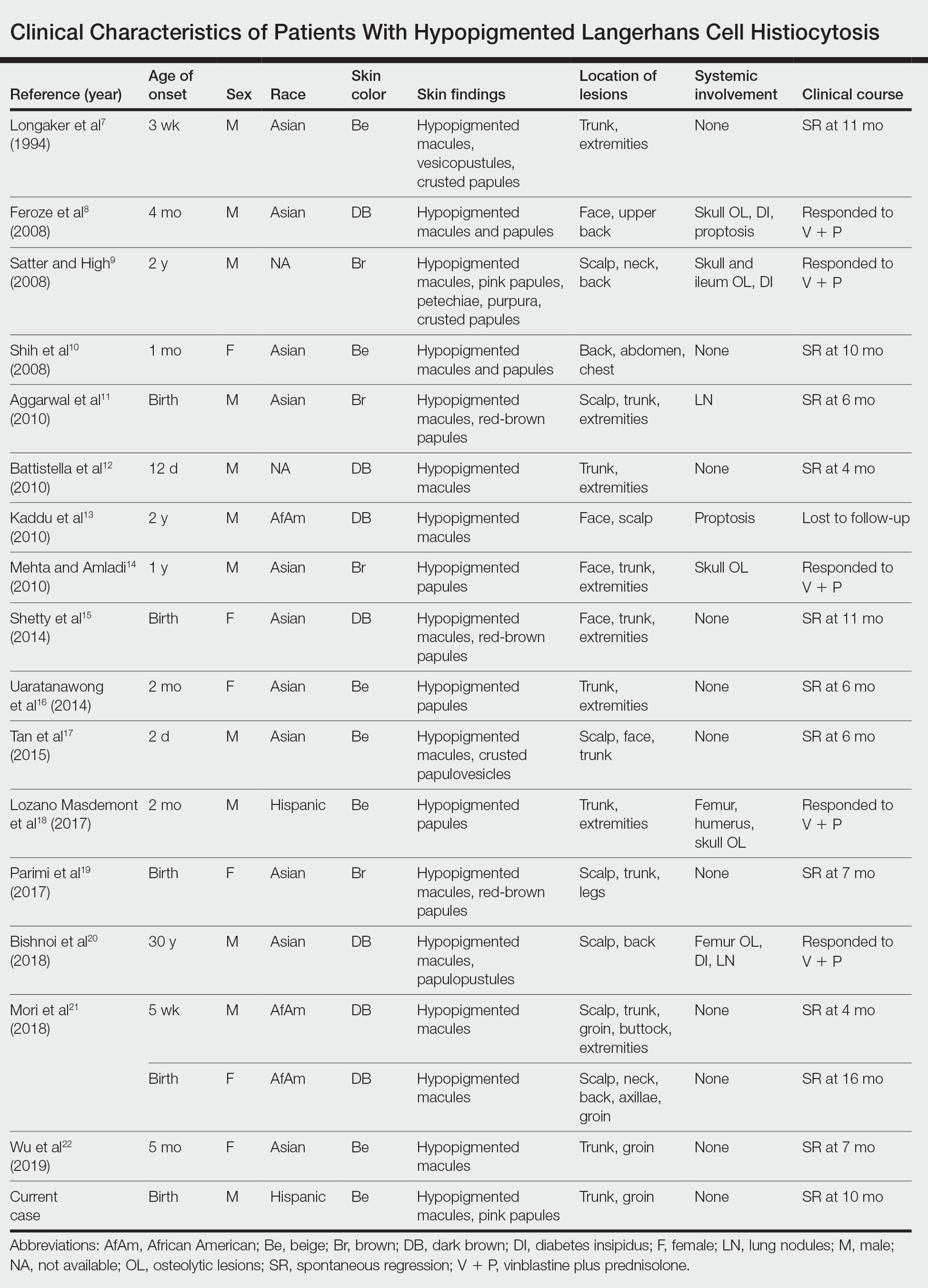

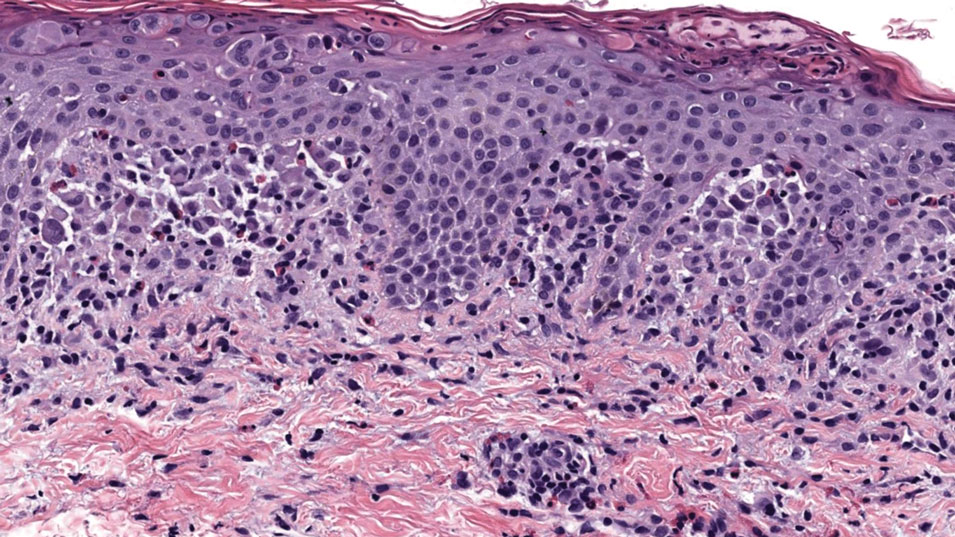

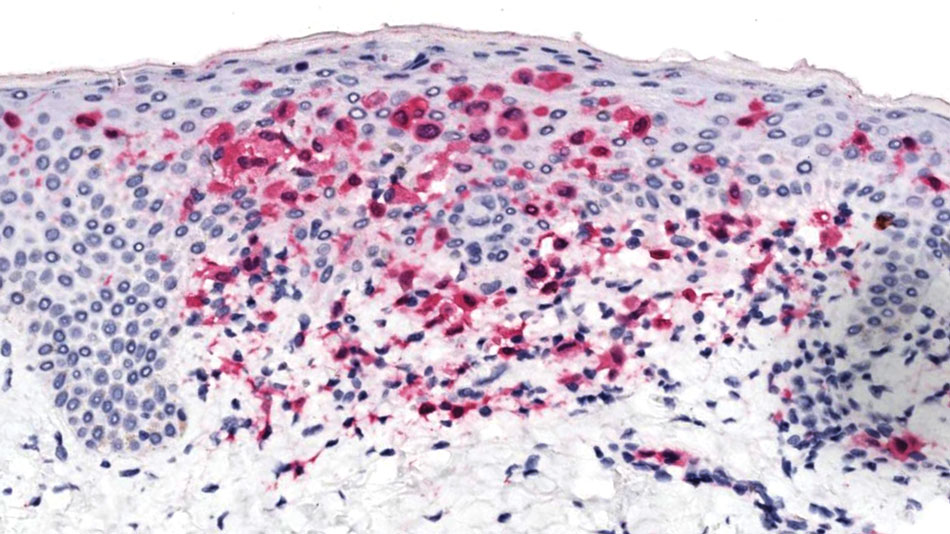

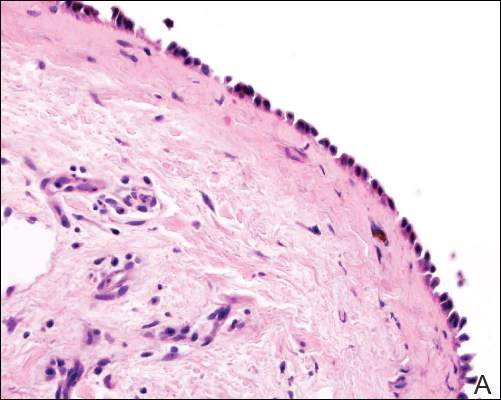

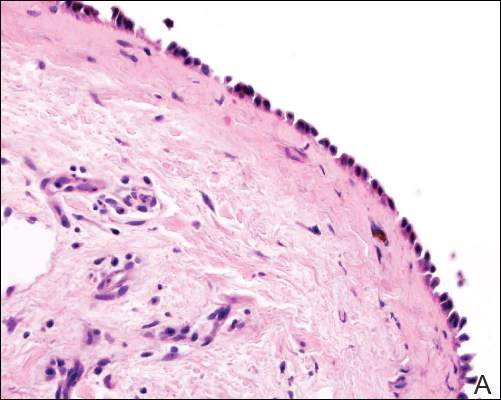

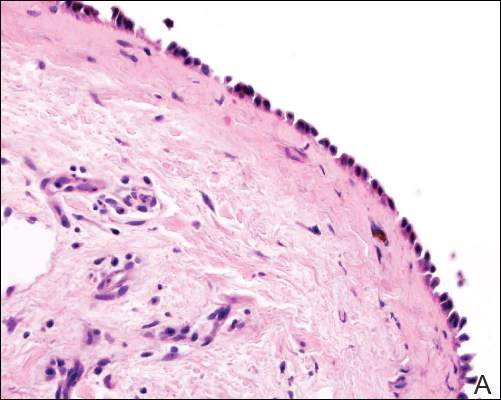

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

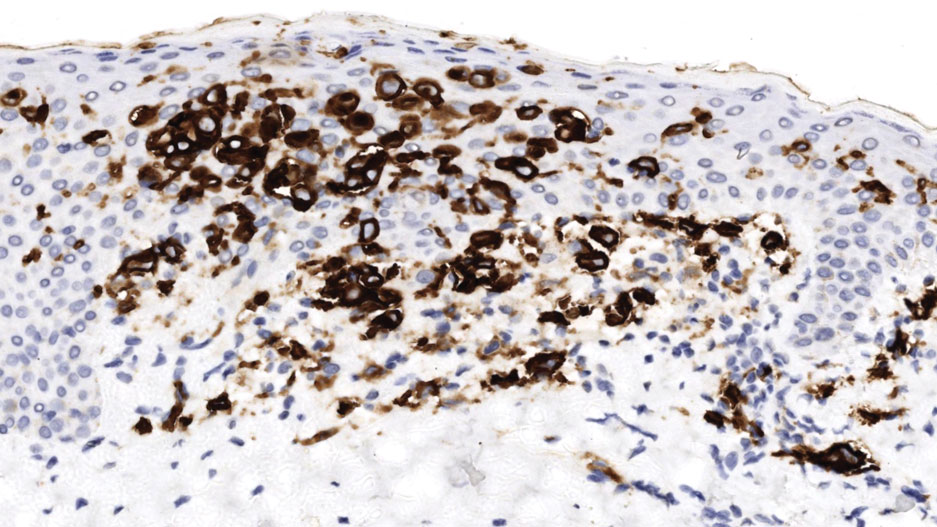

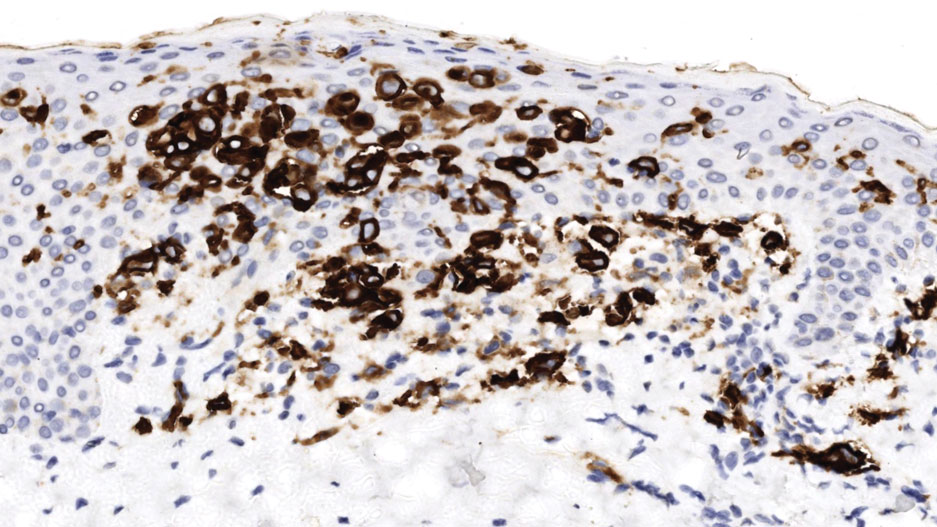

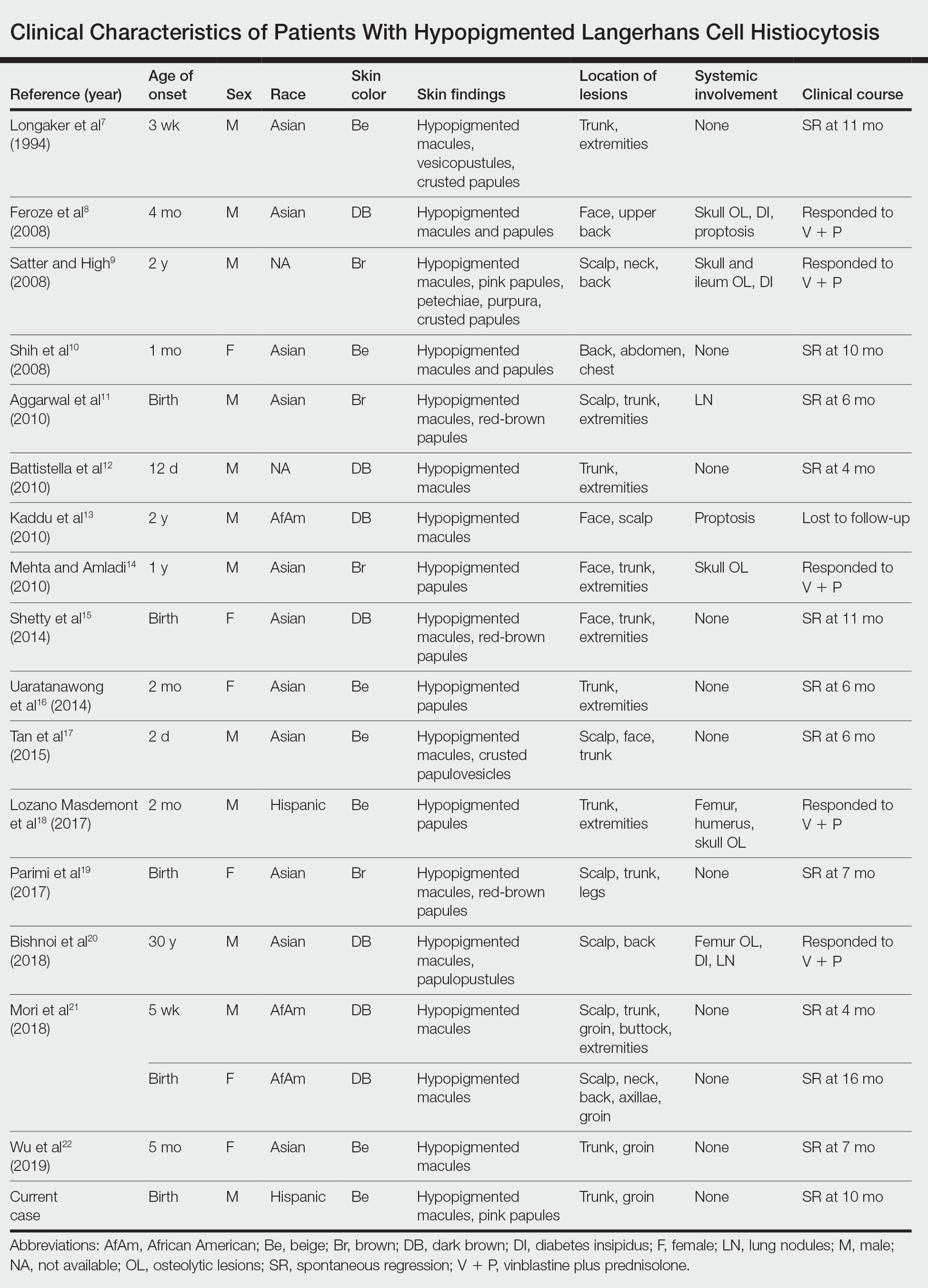

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the hypopigmented variant of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), which has been reported exclusively in patients with skin of color.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of hypopigmented macules, which may be the only cutaneous manifestation or may coincide with typical lesions of LCH.

- Hypopigmented cutaneous LCH may be more common in newborns and associated with a better prognosis.

Radiation-Induced Pemphigus or Pemphigoid Disease in 3 Patients With Distinct Underlying Malignancies

A number of adverse cutaneous effects may result from radiation therapy, including radiodermatitis, alopecia, and radiation-induced neoplasms. Radiation therapy rarely induces pemphigus or pemphigoid disease, but awareness of this disorder is of clinical importance because these cutaneous lesions may resemble other skin diseases, including recurrent underlying cancer. We report 3 cases of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease that occurred after radiation therapy for in situ ductal carcinoma of the breast, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin, respectively.

Case Reports

To identify all the patients with radiation-induced pemphigus, pemphigoid diseases, or both diagnosed and treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) from 1988 to 2009, we performed a computerized search of dermatology, laboratory medicine, and pathology medical records using the following keywords: radiation, pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, and blistering disease. Inclusion criteria were a history of radiation therapy and subsequent development of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease within the irradiated fields. Patients with a history of immunobullous disease preceding radiation therapy and patients with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus or paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome were excluded. The diagnoses were confirmed by routine pathology as well as direct and indirect immunofluorescence examinations.

We identified 3 patients with severe extensive radiation-associated pemphigus/pemphigoid disease that had developed within 14 months after they received radiation therapy for their underlying cancer. The identified patients’ medical records were reviewed for underlying malignancy, symptoms at the time of diagnosis, treatment course, and follow-up. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Patient 1—A 58-year-old woman was diagnosed with in situ ductal carcinoma of the right breast and underwent a lumpectomy with subsequent radiation therapy at an outside institution. Fourteen months after the final radiation treatment, she developed localized flaccid blisters and a superficial erosion on the right areola (Figure 1). Routine pathologic and direct immunofluorescence studies performed on shave biopsies in conjunction with serum analysis by indirect immunofluorescence confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 2). Additionally, a deeper 4-mm punch biopsy ruled out metastatic breast carcinoma. The patient initially was treated with prednisone 60 mg and azathioprine 50 mg daily. The prednisone was tapered over 4 to 5 months to a dose of 5 mg every other day for another 4 to 5 months. Azathioprine was discontinued after a few months because of increased liver enzyme levels and a rapid clinical response of the pemphigus to this regimen.

Subsequently, she developed oral and ocular erosions that were compatible with pemphigus and were believed to be precipitated by trauma secondary to dental work and to the use of contact lenses. These flares were treated and stabilized with short courses of prednisone at higher doses that were successfully tapered to a maintenance dose of 5 mg every other day to control the pemphigus. With that prednisone dosage, her disease has remained clinically stable.

Patient 2—A 40-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IIIB cervical squamous carcinoma with para-aortic adenopathy. She was initially treated with primary radiation therapy directed at the pelvis and para-aortic regions using a 4-field approach at our institution, and she received weekly cisplatin chemotherapy at another institution. Nine months later, the patient was admitted to our institution with persistent metastatic cervical carcinoma of the retroperitoneum. She was scheduled for intraoperative radiation therapy as well as aggressive surgical cytoreduction. The day before her surgery she presented to our dermatology clinic with a generalized pruritic rash of 1 month’s duration and occasional blistering without mucosal involvement. Biopsy specimens from the lower back and abdomen were sent for routine histologic studies and direct immunofluorescence. Serum was sent for analysis by indirect immunofluorescence. Pathology results were consistent with a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid with an infiltrate of eosinophils in the papillary dermis; direct immunofluorescence revealed continuous strong linear deposition of C3, which also was consistent with pemphigoid.

At that time, we recommended application of topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily to affected areas before initiating prednisone. Postoperatively, her rash improved dramatically with clobetasol monotherapy. However, 4 months after discharge from our hospital, her local dermatologist called us for a telephone consultation regarding clinical and laboratory evidence of pemphigoid relapse. A direct immunofluorescence study showed both linear IgG and C3 deposition. The patient had healed well from the surgery, and the metastatic cervical carcinoma was quiescent. Prednisone in combination with a second immunosuppressive agent was recommended, pending approval by her local oncologist. No further follow-up information is available at this time.

Patient 3—A 72-year-old woman presented with a blistering eruption that had developed on the neck, the upper part of the chest, and other body sites, including the oral mucosa, 6 months after radiation therapy for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin on the neck. On admission to the local hospital, she received a diagnosis of pemphigoid, although the outside biopsy specimens and reports were not available.

The patient was initially treated with prednisone, which was rapidly tapered because she was diabetic and her blood glucose levels were labile. Consequently, she was switched to azathioprine 50 mg 3 times daily and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 3 times daily. The patient was transferred to our institution with mild fatigue, dysphagia, weight loss, and generalized blistering involving the skin and lips. Otolaryngologic consultation and radiographic evaluation revealed no evidence of recurrent carcinoma. A shave biopsy was obtained for routine histologic evaluation and immunofluorescence and confirmed the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. The patient, however, also was found to have pancytopenia, most likely induced by the combination of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Her therapeutic regimen was switched to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to be applied to the eroded areas twice daily and mupirocin ointment to be applied to the hemorrhagic scabs. Subsequently, her complete blood cell count returned to normal.

She continued to use topical corticosteroid therapy to control pemphigoid symptoms, but 6 months later the patient was found to have a lung mass and died secondary to respiratory failure.

|

|

| Figure 2. Pathologic and immunofluorescence studies confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. Intraepidermal acantholysis forming a suprabasal blister with a tombstone appearance was seen along the basal cell layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Intercellular IgG deposition involving the epidermis was noted with direct immunofluorescence (B)(original magnification ×600). | |

|

|

Comment

A wide range of cutaneous reactions are known to occur in conjunction with radiation therapy. Early or acute adverse effects on the skin, such as erythema, edema, and desquamation, can be observed during radiation therapy and for several weeks thereafter. They are usually followed by hair loss and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pemphigus or pemphigoid disease is a rare complication of radiation therapy and has been reported in case reports and small case series.1-17 These disorders include bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, bullous lupus erythematosus, and acquired epidermolysis bullosa.10

The mechanism by which radiation therapy induces pemphigus remains open to speculation. Ionizing radiation may alter the antigenicity of the keratinocyte surface by disrupting the sulfhydryl groups,13 thus changing the immunoreactivity of the desmogleins or unmasking certain epidermal antigens. Another possible explanation is immune surveillance interference by damaged T-suppressor cells, which are preferentially sensitive to radiation.8 Robbins et al12 presented a patient with radiation-induced mucocutaneous pemphigus. They performed immunomapping of perilesional skin for the irradiated field, which illustrated altered expression of desmoglein (Dsg) 1, a commonly targeted antigen in pemphigus. Their study also suggested that radiation changed either the distribution or the expression of Dsg1 in the epidermis.12

Approximately half the reported cases we identified were associated with breast carcinoma,1-4,8,14 as in the case of patient 1. The majority of patients initially experienced blistering confined to the irradiated area followed by a variable degree of dissemination to other sites, probably due to the epitope-spreading phenomenon.12 During the months after radiation therapy, Aguado et al1 documented that their patient, who was initially positive for only anti-Dsg3 antibody, developed anti-Dsg1 antibodies. Therefore, the unusual development of mucosal ulcers, other skin lesions, or both after radiation therapy should raise suspicion for this diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid primarily affects elderly patients with blister formation along the dermoepidermal junction. Various causes, such as drugs, trauma, UV light, and ionizing radiation, have been associated with this autoimmune blistering disorder. In a systemic literature review, Mul et al10 discovered 27 case reports of bullous pemphigoid that were associated with radiation. It has been suggested that the alteration of the antigenicity and damaged dermoepidermal junction by radiation is a disease-producing mechanism.15,16 Another explanation is that the patients had subclinical pemphigoid and underwent radiation therapy, which damaged the basal layer sufficiently to produce subepidermal blister formation (triggered pemphigoid).17

The patients in this analysis had clinical presentations similar to those previously reported, with a blistering rash that usually began in the irradiated field, raising the possibility of acute radiation dermatitis. However, unlike acute radiation dermatitis, the lesions extended beyond the radiation fields in all 3 cases with mucosal involvement in patients 1 and 3. Although an onset of pemphigoid was previously observed after a minimum dose of 20 Gy,10 there was no definitive correlation observed between the extent and the severity of the cutaneous eruption and the radiation dose in prior studies. Unfortunately, we could not obtain exact radiation doses in our cases because all 3 patients were treated by radiation oncologists at other institutions. We did not, however, observe in our patients that the eruptions were more severe within the irradiated areas. Our analysis demonstrated that radiation-induced pemphigus or pemphigoid disease does not differ greatly from the endogenous form of the disease in its response to therapy or clinical course.