User login

Tips and tools to help refine your approach to chest pain

One of the most concerning and challenging patient complaints presented to physicians is chest pain. Chest pain is a ubiquitous complaint in primary care settings and in the emergency department (ED), accounting for 8 million ED visits and 0.4% of all primary care visits in North America annually.1,2

Despite the great number of chest-pain encounters, early identification of life-threatening causes and prompt treatment remain a challenge. In this article, we examine how the approach to a complaint of chest pain in a primary care practice (and, likewise, in the ED) must first, rest on the clinical evaluation and second, employ risk-stratification tools to aid in evaluation, appropriate diagnosis, triage, and treatment.

Chest pain by the numbers

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the cause of chest pain in 5.1% of patients with chest pain who present to the ED, compared with 1.5% to 3.1% of chest-pain patients seen in ambulatory care.1,3 “Nonspecific chest pain” is the most frequent diagnosis of chest pain in the ED for all age groups (47.5% to 55.8%).3 In contrast, the most common cause of chest pain in primary care is musculoskeletal (36%), followed by gastrointestinal disease (18% to 19%); serious cardiac causes (15%), including ACS (1.5%); nonspecific causes (16%); psychiatric causes (8%); and pulmonary causes (5% to 10%).4 Among patients seen in the ED because of chest pain, 57.4% are discharged, 30.6% are admitted for further evaluation, and 0.4% die in the ED or after admission.3

First challenge: The scale of the differential Dx

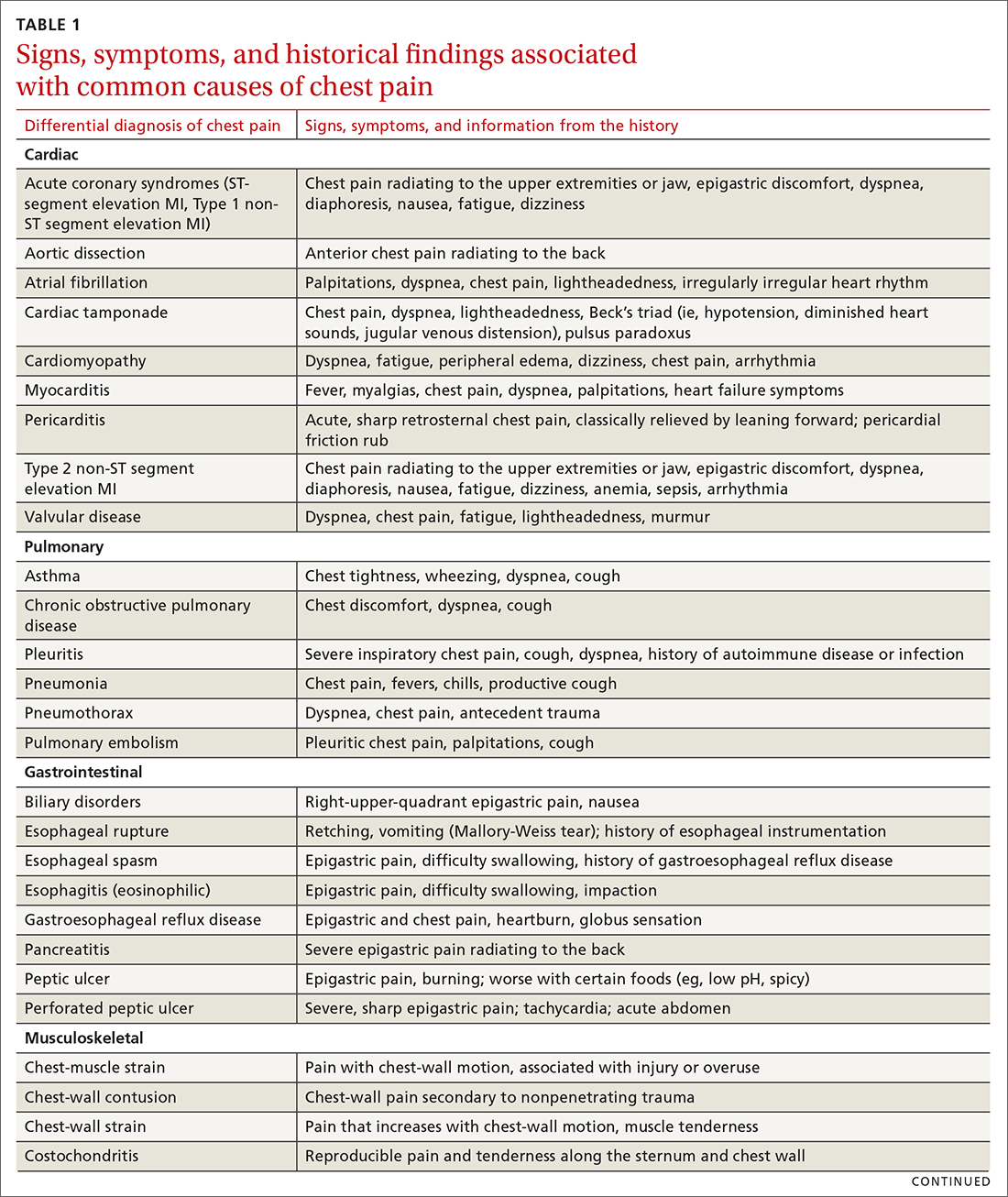

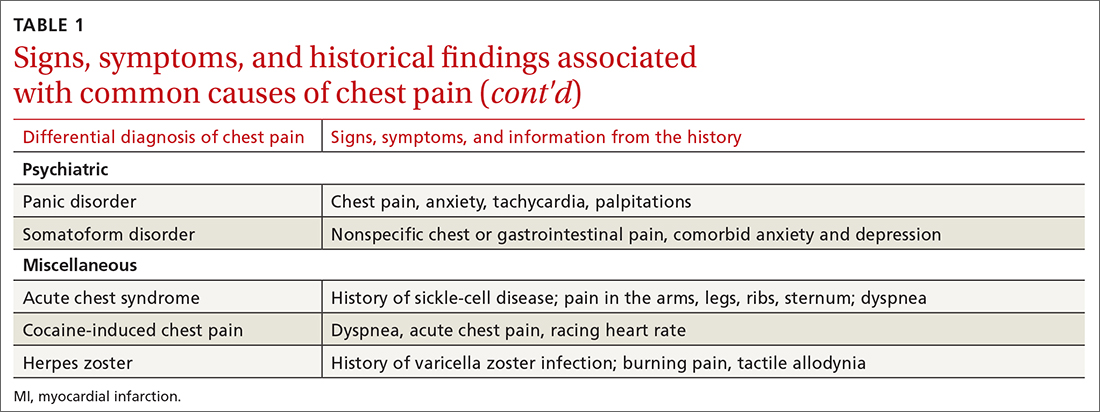

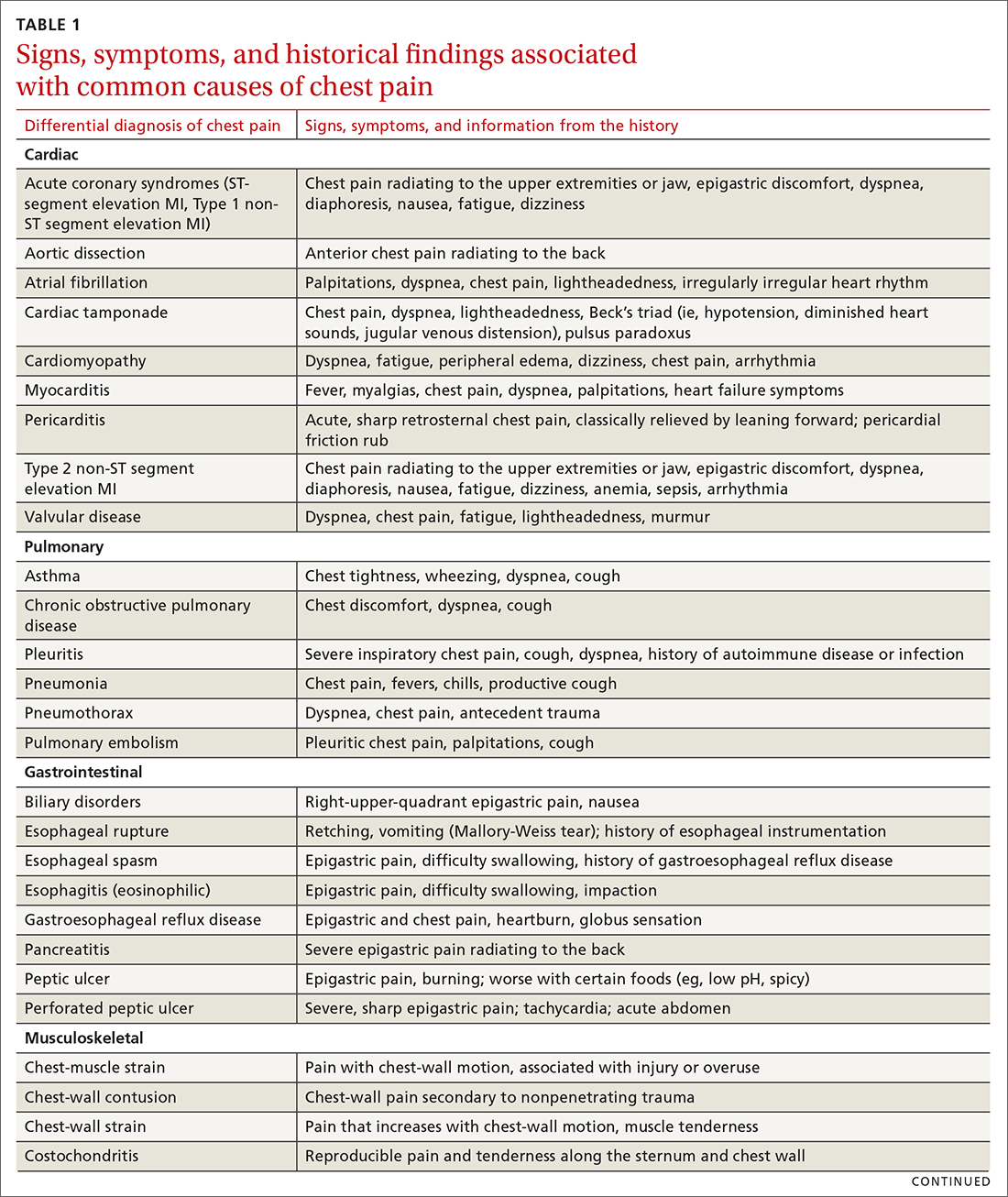

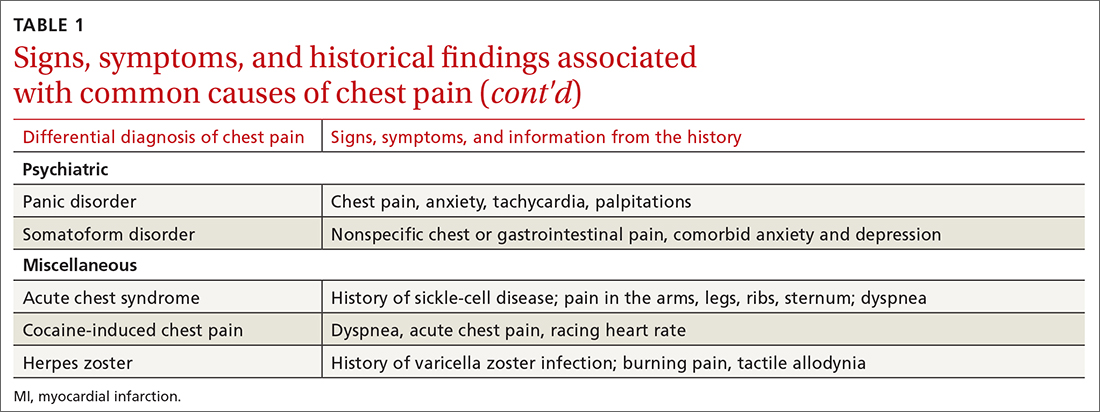

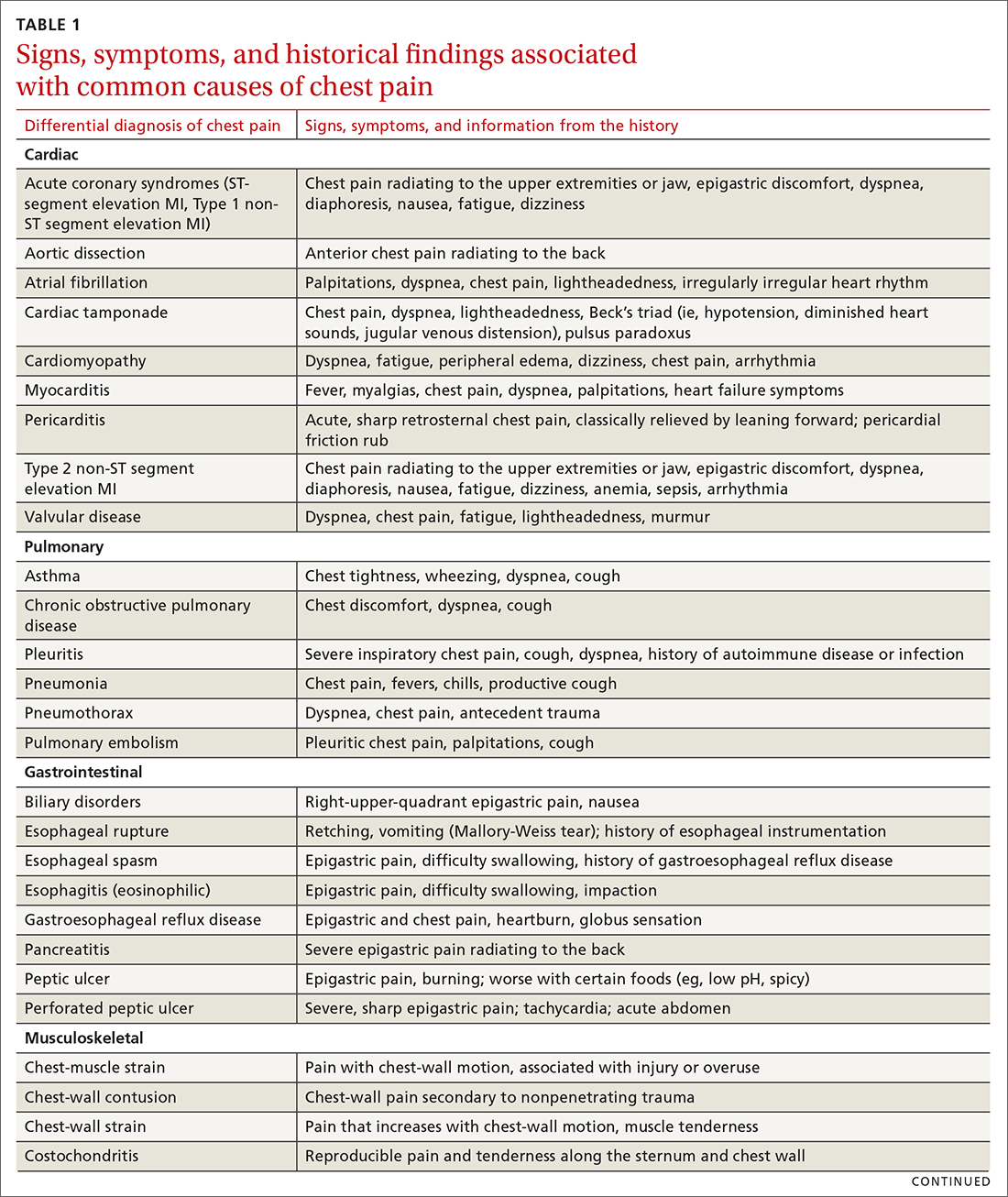

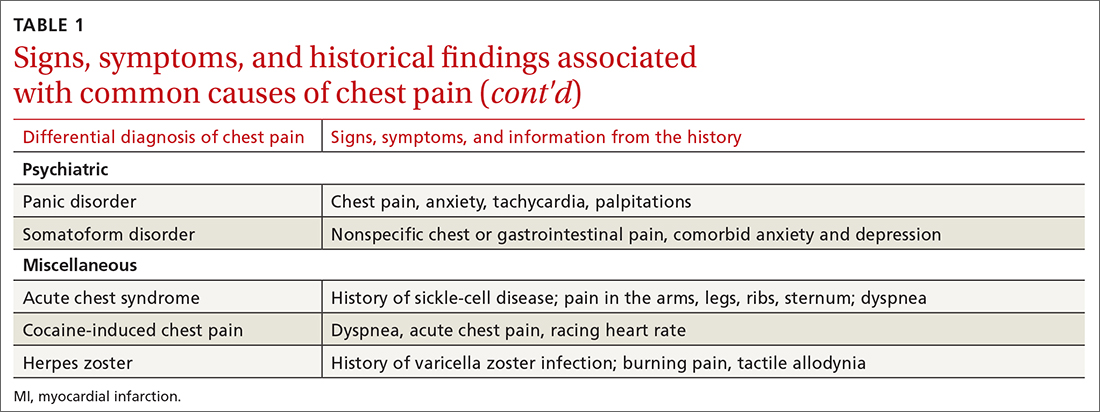

The differential diagnosis of chest pain is broad. It includes life-threatening causes, such as ACS (from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], Type 1 non-STEMI, and unstable angina), acute aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism (PE), esophageal rupture, and tension pneumothorax, as well as non-life-threatening causes (TABLE 1).

History and physical exam guide early decisions

Triage assessment of the patient with chest pain, including vital signs, general appearance, and basic symptom questions, can guide you as to whether they require transfer to a higher level of care. Although an individual’s findings cannot, alone, accurately exclude or diagnose ACS, the findings can be used in combination in clinical decision tools to distinguish noncardiac chest pain from ACS.

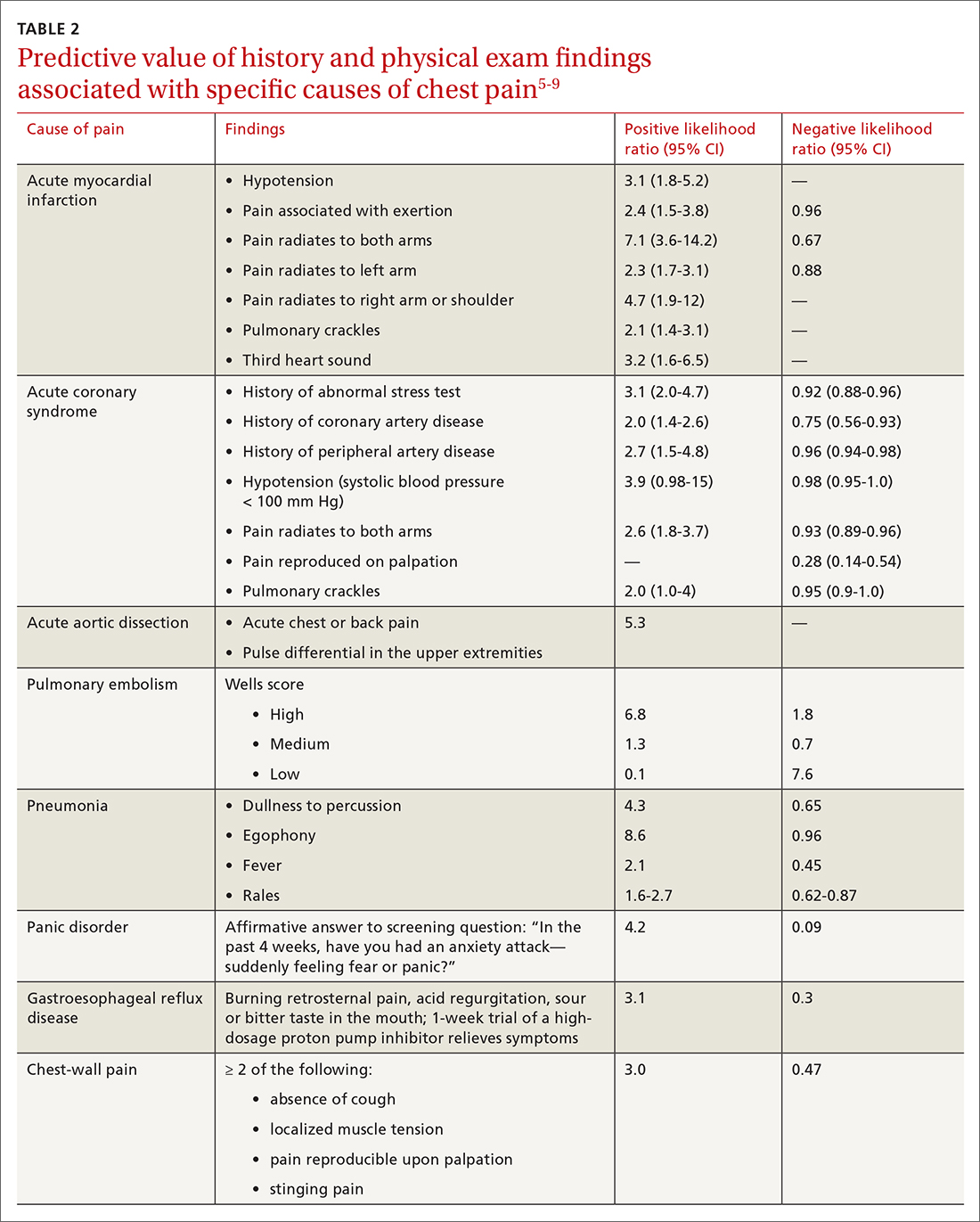

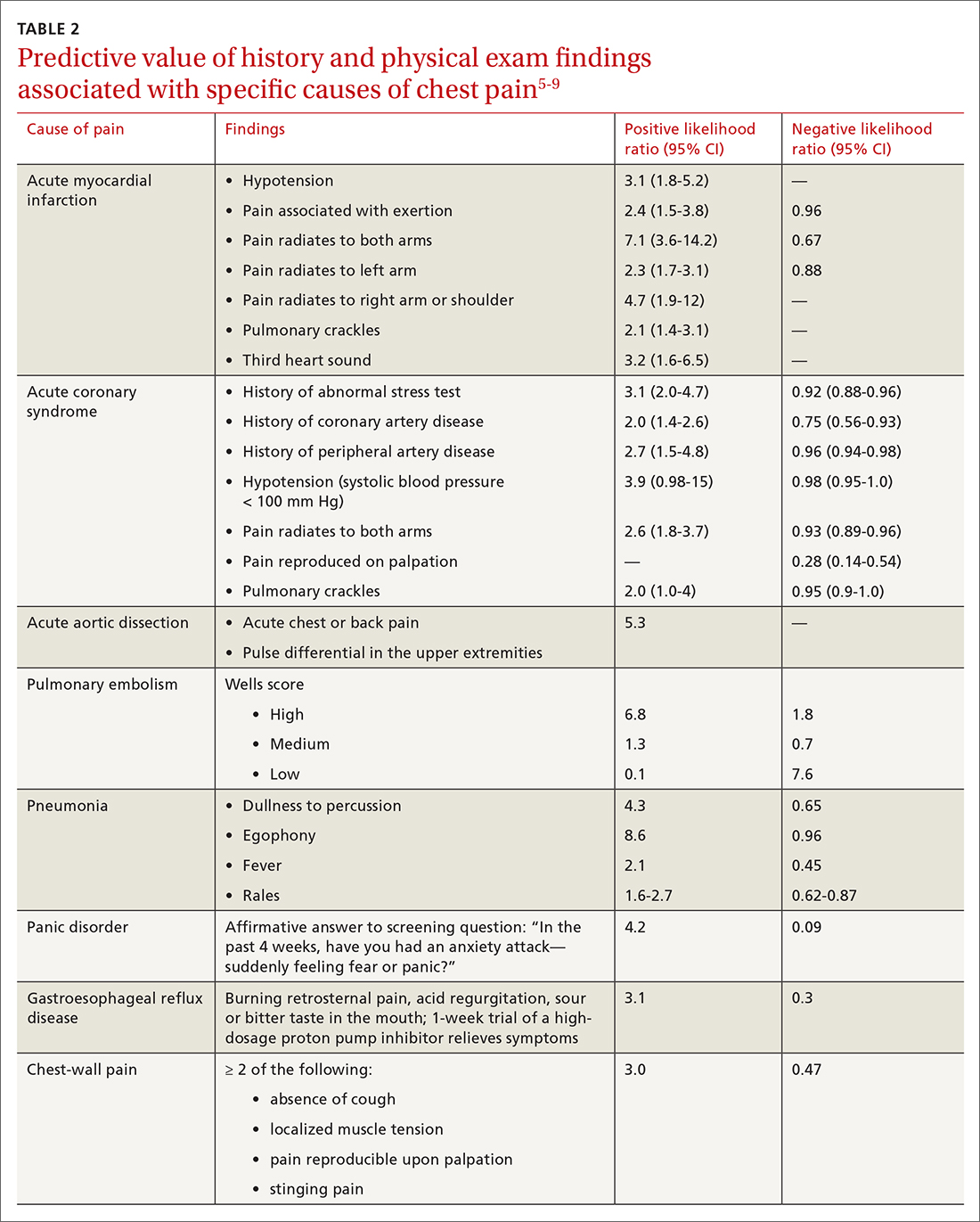

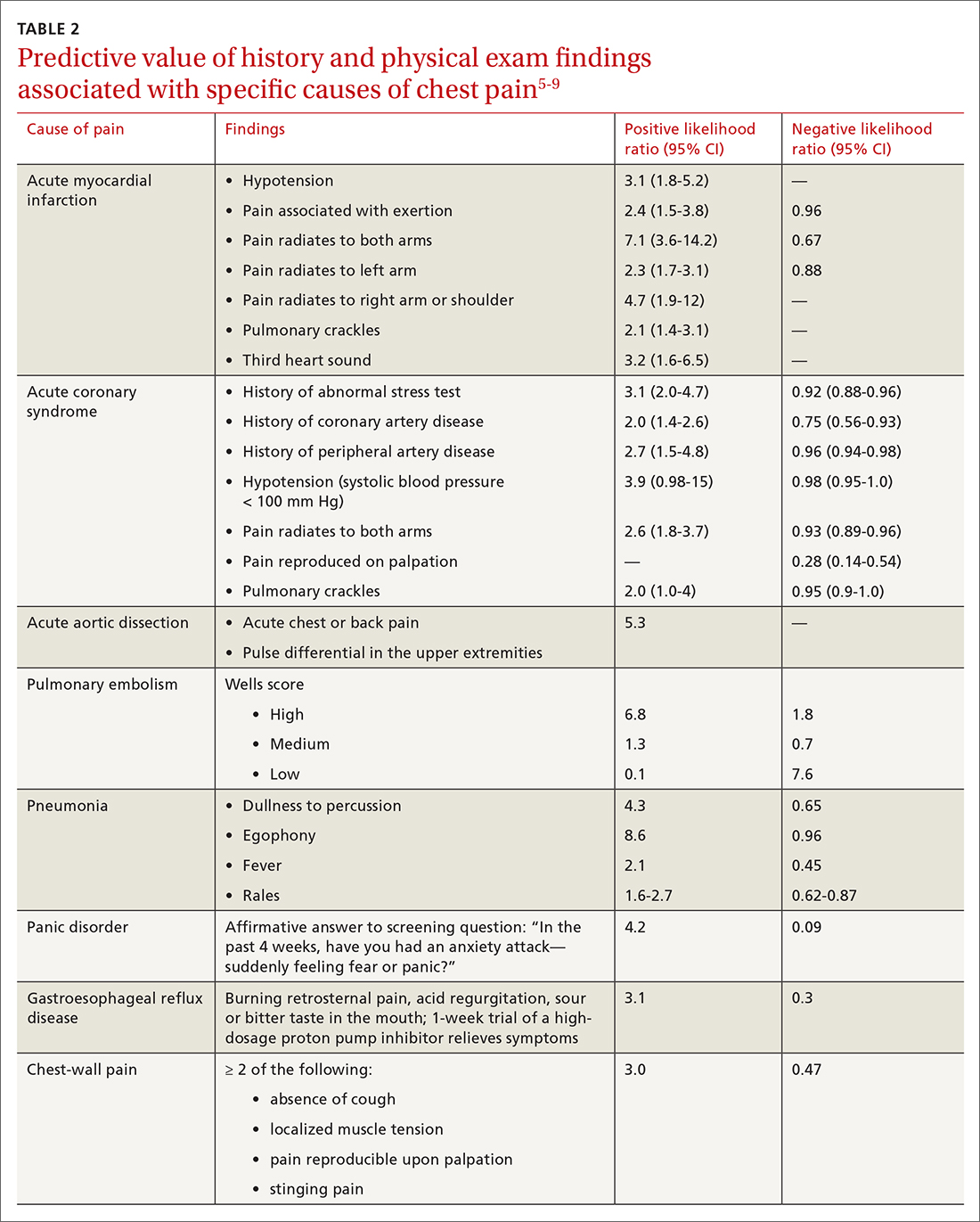

History. Features in the history (TABLE 25-9) that are most helpful at increasing the probability (ie, a positive likelihood ratio [LR] ≥ 2) of chest pain being caused by ACS are:

- pain radiating to both arms or the right arm

- pain that is worse upon exertion

- a history of peripheral artery disease or coronary artery disease (CAD)

- a previously abnormal stress test.

The presence of any prior normal stress test is unhelpful: Such patients have a similar risk of a 30-day adverse cardiac event as a patient who has never had a stress test.5

Continue to: A history of tobacco use...

A history of tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery bypass grafting, or a family history of CAD does not significantly increase the risk of ACS.6 However, exploring each of these risk factors further is important, because genetic links between these risk factors can lead to an increased risk of CAD (eg, familial hypercholesterolemia).7

A history of normal or near-normal coronary angiography (< 25% stenosis) is associated with a lower likelihood of ACS, because 98% of such patients are free of AMI and 90% are without single-vessel coronary disease nearly 10 years out.6 A history of coronary artery bypass grafting is not necessarily predictive of ACS (LR = 1-3).5,6

Historical features classically associated with ACS, but that have an LR < 2, are pain radiating to the neck or jaw, nausea or vomiting, dyspnea, and pain that is relieved with nitroglycerin.5,6 Pain described as pleuritic, sharp, positional, or reproduced with palpation is less likely due to AMI.5

Physical exam findings are not independently diagnostic when evaluating chest pain. However, a third heart sound is the most likely finding associated with AMI and hypotension is the clinical sign most likely associated with ACS.5

Consider the diagnosis of PE in all patients with chest pain. In PE, chest pain might be associated with dyspnea, presyncope, syncope, or hemoptysis.8 On examination, 40% of patients have tachycardia.8 If PE is suspected; the patient should be risk-stratified using a validated prediction rule (see the discussion of PE that follows).

Continue to: Other historical features...

Other historical features or physical exam findings correlate with aortic dissection, pneumonia, and psychiatric causes of chest pain (TABLE 25-9).

Useful EKG findings

Among patients in whom ACS or PE is suspected, 12-lead electrocardiography (EKG) should be performed.

AMI. EKG findings most predictive of AMI are new ST-segment elevation or depression > 1 mm (LR = 6-54), new left bundle branch block (LR = 6.3), Q wave (positive LR = 3.9), and prominent, wide-based (hyperacute) T wave (LR = 3.1).10

ACS. Useful EKG findings to predict ACS are ST-segment depression (LR = 5.3 [95% CI, 2.1-8.6]) and any evidence of ischemia, defined as ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, or Q wave (LR = 3.6 [95% CI, 1.6-5.7]).10

PE. The most common abnormal finding on EKG in the setting of PE is sinus tachycardia.

Continue to: Right ventricular strain

Right ventricular strain. Other findings that reflect right ventricular strain, but are much less common, are complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, prominent S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III, and T-wave inversion in lead III (S1Q3T3; the McGinn-White sign) and in leads V1-V4.8

The utility of troponin and high-sensitivity troponin testing

Clinical evaluation and EKG findings are unable to diagnose or exclude ACS without the use of the cardiac biomarker troponin. In the past decade, high-sensitivity troponin assays have been used to stratify patients at risk of ACS.11,12 Many protocols now exist using short interval (2-3 hours), high-sensitivity troponin testing to identify patients at low risk of myocardial infarction who can be safely discharged from the ED after 2 normal tests of the troponin level.13-16

An elevated troponin value alone, however, is not a specific indicator of ACS; troponin can be elevated in the settings of myocardial ischemia related to increased oxygen demand (Type 2 non-STEMI) and decreased renal clearance. Consideration of the rate of rising and falling levels of troponin, its absolute value > 99th percentile, and other findings is critical to interpreting an elevated troponin level.17 Studies in which the HEART score (History, Electrocardiography, Age, Risk factors, Troponin) was combined with high-sensitivity troponin measurement show that this pairing is promising in reducing unnecessary admissions for chest pain.18 (For a description of this tool, see the discussion of the HEART score that follows.) Carlton and colleagues18 showed that a HEART score ≤ 3 and a negative high-sensitivity troponin I level had a negative predictive value of ≥ 99.5% for AMI.

Clinical decision tools: Who needs care? Who can go home?

Given the varied presentations of patients with life-threatening causes of chest pain, it is challenging to confidently determine who is safe to send home after initial assessment. Guidance in 2014 from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology recommends risk-stratifying patients for ACS using clinical decision tools to help guide management.19,20 The American College of Physicians, in its 2015 guidelines, also recommends using a clinical decision tool to assess patients when there is suspicion of PE.21 Clinical application of these tools identifies patients at low risk of life-threatening conditions and can help avoid unnecessary intervention and a higher level of care.

Tools for investigating ACS

The Marburg Heart Score22 assesses the likelihood of CAD in ambulatory settings while the HEART score assesses the risk of major adverse cardiac events in ED patients.23 The Diamond Forrester criteria can be used to assess the pretest probability of CAD in both settings.24

Continue to: Marburg Heart Score

Marburg Heart Score. Validated in patients older than 35 years of age in 2 different outpatient populations in 201022 and 2012,25 the Marburg score is determined by answering 5 questions:

- Female ≥ 65 years? Or male ≥ 55 years of age? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Known CAD, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain worse with exercise? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain reproducible with palpation? (No, +1, Yes, 0)

- Does the patient assume that the pain is cardiac in nature? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

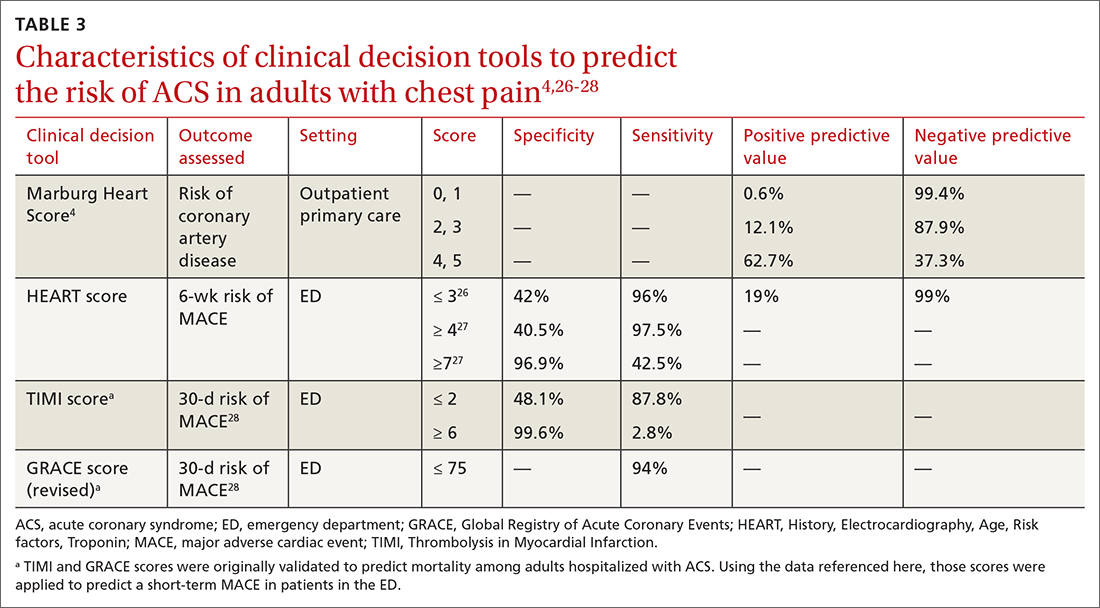

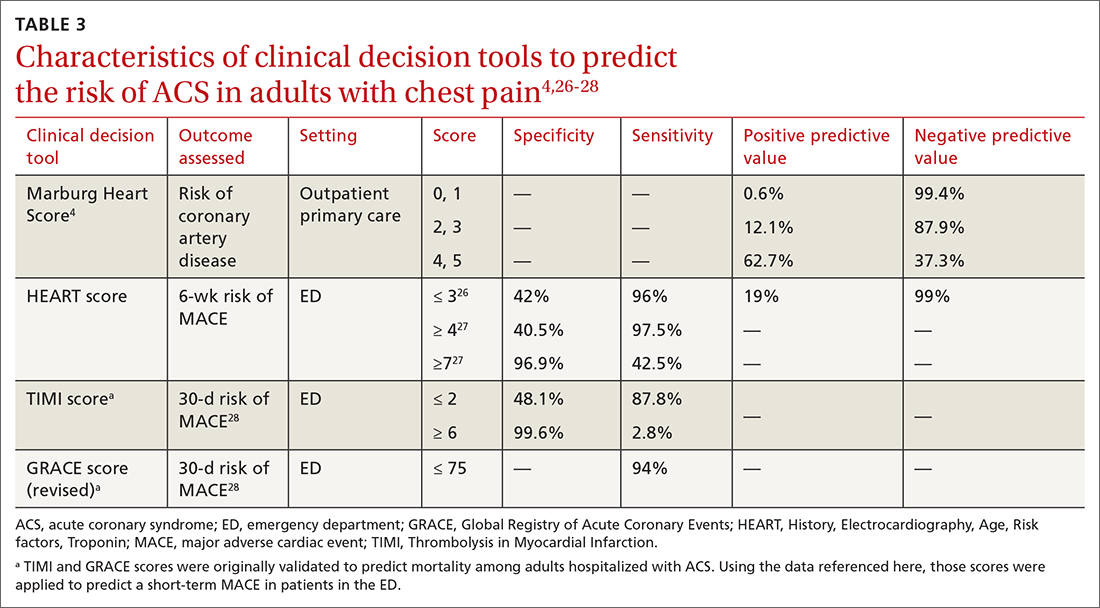

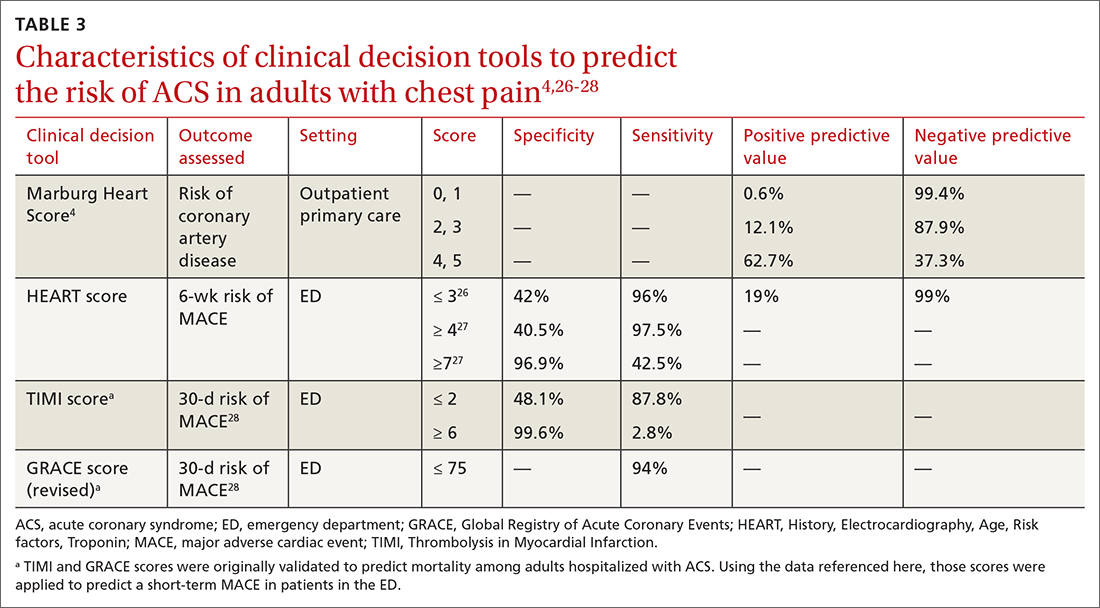

A Marburg Heart Score of 0 or 1 means CAD is highly unlikely in a patient with chest pain (negative predictive value = 99%-100%; positive predictive value = 0.6%)4 (TABLE 34,26-28). A score of ≤ 2 has a negative predictive value of 98%. A Marburg Heart Score of 4 or 5 has a relatively low positive predictive value (63%).4

This tool does not accurately diagnose acute MI, but it does help identify patients at low risk of ACS, thus reducing unnecessary subsequent testing. Although no clinical decision tool can rule out AMI with absolute certainty, the Marburg Heart Score is considered one of the most extensively tested and sensitive tools to predict low risk of CAD in outpatient primary care.29

INTERCHEST rule (in outpatient primary care) is a newer prediction rule using data from 5 primary care–based studies of chest pain.30 For a score ≤ 2, the negative predictive value for CAD causing chest pain is 97% to 98% and the positive predictive value is 43%. INTERCHEST incorporates studies used to validate the Marburg Heart Score, but has not been validated beyond initial pooled studies. Concerns have been raised about the quality of these pooled studies, however, and this rule has not been widely accepted for clinical use at this time.29

The HEART score has been validated in patients older than 12 years in multiple institutions and across multiple ED populations.23,31,32 It is widely used in the ED to assess a patient’s risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over the next 6 weeks. MACE is defined as AMI, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or death.

Continue to: The HEART score...

The HEART score is calculated based on 5 components:

- History of chest pain (slightly [0], moderately [+1], or highly [+2]) suspicious for ACS)

- EKG (normal [0], nonspecific ST changes [+1], significant ST deviations [+2])

- Age (< 45 y [0], 45-64 y [+1], ≥ 65 y [+2])

- Risk factors (none [0], 1 or 2 [+1], ≥ 3 or a history of atherosclerotic disease [+2]) a

- Initial troponin assay, standard sensitivity (≤ normal [0], 1-3× normal [+1], > 3× normal [+2]).

For patients with a HEART score of 0-3 (ie, at low risk), the pooled positive predictive value of a MACE was determined to be 0.19 (95% CI, 0.14-0.24), and the negative predictive value was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98-0.99)—making it an effective tool to rule out a MACE over the short term26 (TABLE 34,26-28).

Because the HEART Score was published in 2008, multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compared it to the TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) and GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) scores for predicting short-term (30-day to 6-week) MACE in ED patients.27,28,33,34 These studies have all shown that the HEART score is relatively superior to the TIMI and GRACE tools.

Characteristics of these tools are summarized in TABLE 3.4,26-28

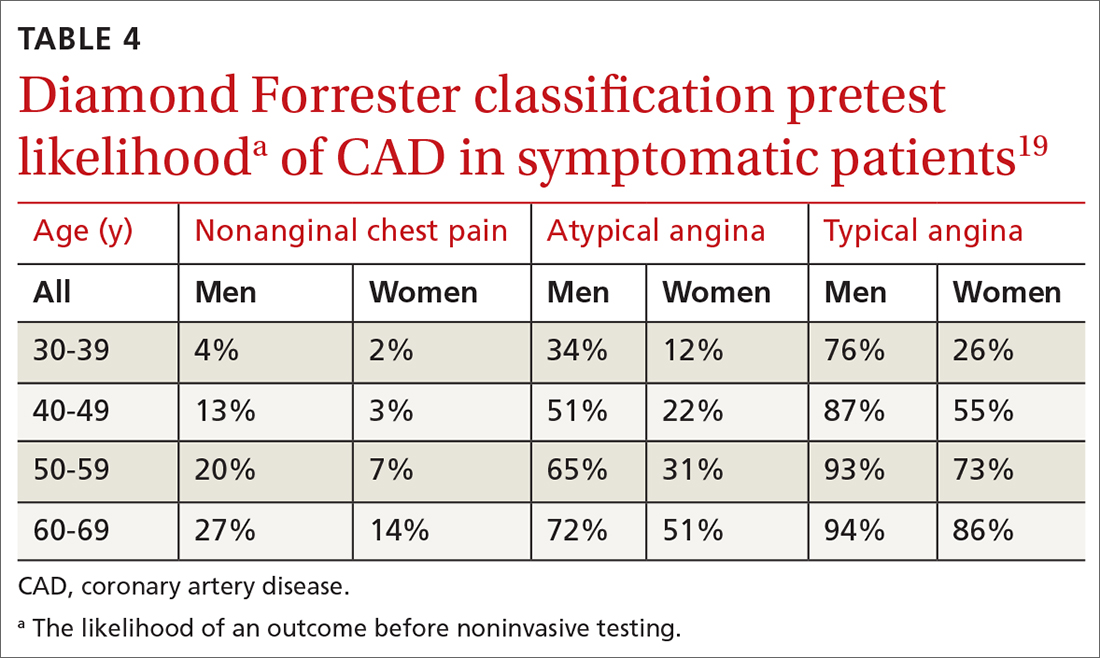

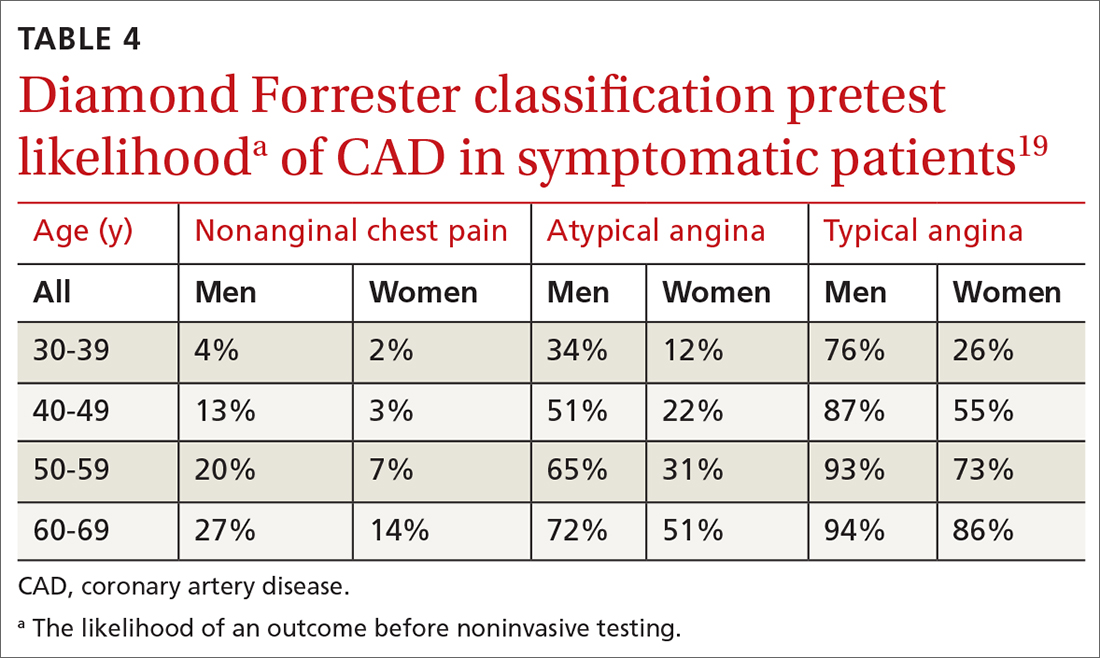

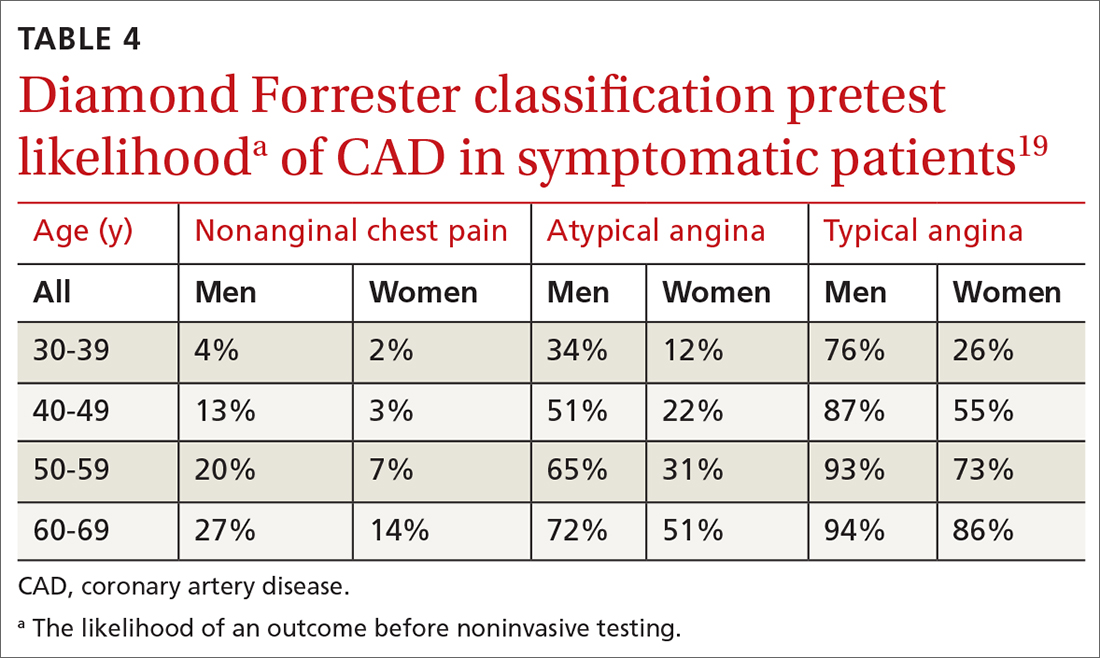

Diamond Forrester classification (in ED and outpatient settings). This tool uses 3 criteria—substernal chest pain, pain that increases upon exertion or with stress, and pain relieved by nitroglycerin or rest—to classify chest pain as typical angina (all 3 criteria), atypical angina (2 criteria), or noncardiac chest pain (0 criteria or 1 criterion).24 Pretest probability (ie, the likelihood of an outcome before noninvasive testing) of the pain being due to CAD can then be determined from the type of chest pain and the patient’s gender and age19 (TABLE 419). Recent studies have found that the Diamond Forrester criteria might overestimate the probability of CAD.35

Continue to: Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Positron-emission tomography stress testing, stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion scanning, exercise treadmill testing. The first 3 of these imaging tests have a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 74% to 87%36; exercise treadmill testing is less sensitive (68%) and specific (77%).37

In a patient with a very low (< 5%) probability of CAD, a positive stress test (of any modality) is likely to be a false-positive; conversely, in a patient with a very high (> 90%) probability of CAD, a negative stress test is likely to be a false-negative.19 The American Heart Association, therefore, does not recommend any of these modalities for patients who have a < 5% or > 90% probability of CAD.19

Noninvasive testing to rule out ACS in low- and intermediate-risk patients who present to the ED with chest pain provides no clinical benefit over clinical evaluation alone.38 Therefore, these tests are rarely used in the initial evaluation of chest pain in an acute setting.

Coronary artery calcium score (CACS), coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). These tests have demonstrated promise in the risk stratification of chest pain, given their high sensitivity and negative predictive value in low- and intermediate-risk patients.39,40 However, their application remains unclear in the evaluation of acute chest pain: Appropriate-use criteria do not favor CACS or CCTA alone to evaluate acute chest pain when there is suspicion of ACS.41 The Choosing Wisely initiative (for “avoiding unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures”; www.choosingwisely.org) recommends against CCTA for high-risk patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain.42

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging does not have an established role in the evaluation of patients with suspected ACS.43

Continue to: Tools for investigating PE

Tools for investigating PE

Three clinical decision tools have been validated to predict the risk of PE: the Wells score, the Geneva score, and Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria (PERC).44,45

Wells score is more sensitive than the Geneva score and has been validated in ambulatory1 and ED46-48 settings. Based on Wells criteria, high-risk patients need further evaluation with imaging. In low-risk patients, a normal D-dimer level effectively excludes PE, with a < 1% risk of subsequent thromboembolism in the following 3 months. Positive predictive value of the Wells decision tool is low because it is intended to rule out, not confirm, PE.

PERC can be used in a low-probability setting (defined as the treating physician arriving at the conclusion that PE is not the most likely diagnosis and can be excluded with a negative D-dimer test). In that setting, if the patient meets the 8 clinical variables in PERC, the diagnosis of PE is, effectively, ruled out.48

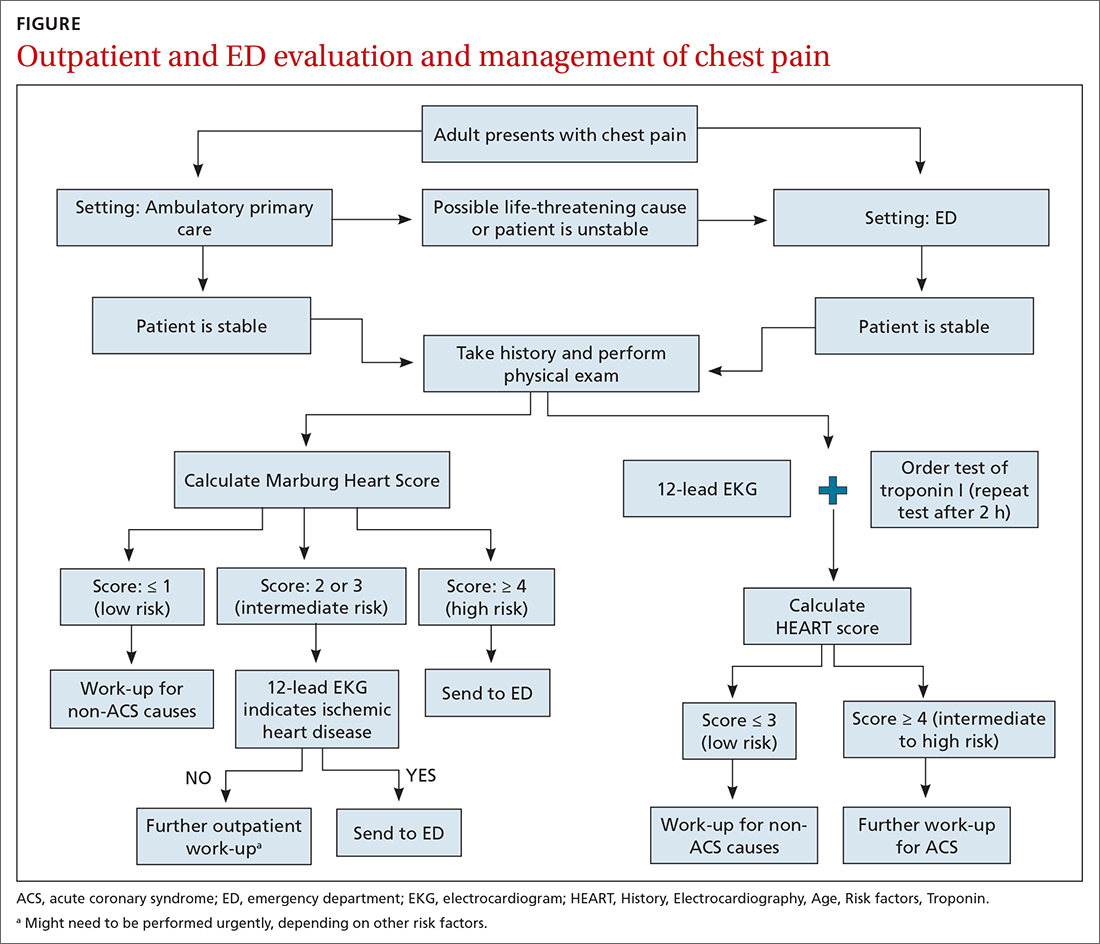

Summing up: Evaluation of chest pain guided by risk of CAD

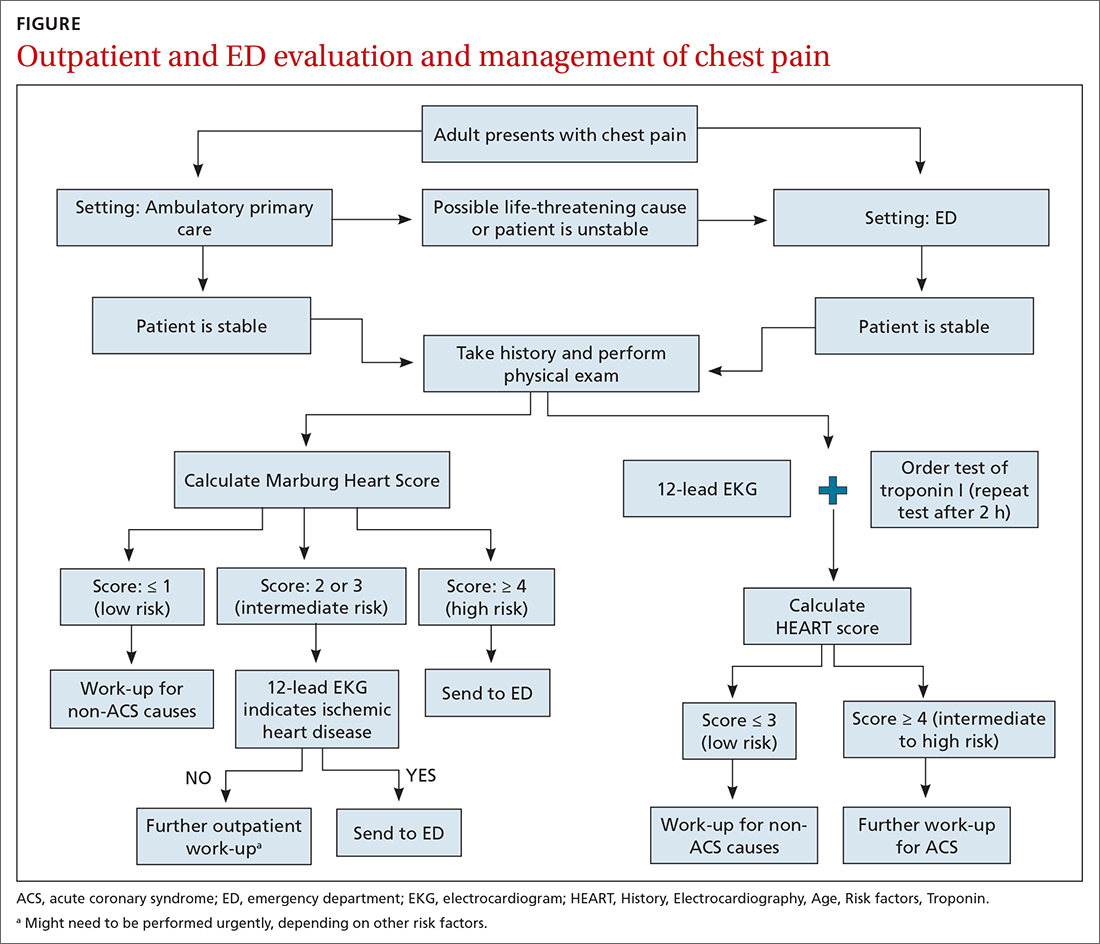

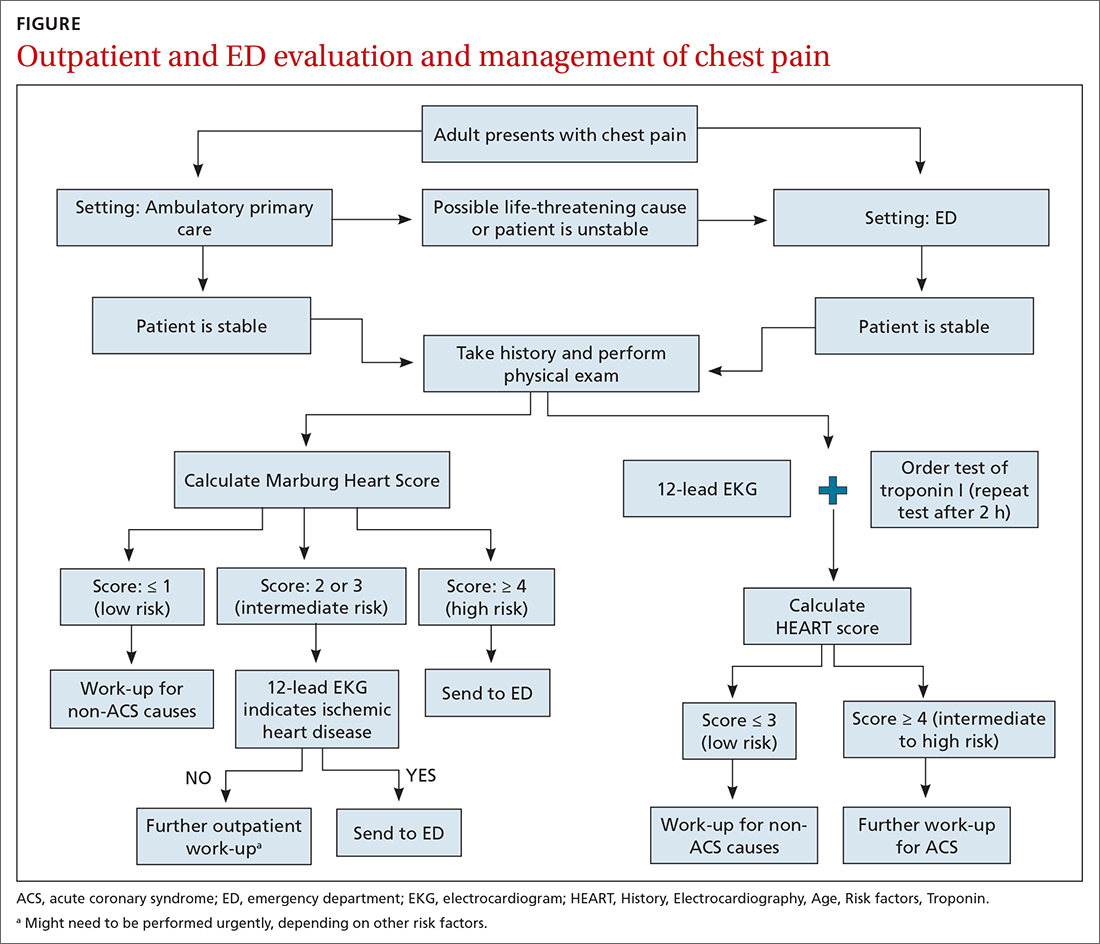

Patients who present in an outpatient setting with a potentially life-threatening cause of chest pain (TABLE 1) and patients with unstable vital signs should be sent to the ED for urgent evaluation. In the remaining outpatients, use the Marburg Heart Score or Diamond Forrester classification to assess the likelihood that pain is due to CAD (in the ED, the HEART score can be used for this purpose) (FIGURE).

When the risk is low. No further cardiac testing is indicated in patients with a risk of CAD < 5%, based on a Marburg score of 0 or 1, or on Diamond Forrester criteria; an abnormal stress test is likely to be a false-positive.19

Continue to: Moderate risk

Moderate risk. However, further testing is indicated, with a stress test (with or without myocardial imaging), in patients whose risk of CAD is 5% to 70%, based on the Diamond Forrester classification or an intermediate Marburg Heart Score (ie, a score of 2 or 3 but a normal EKG). This further testing can be performed urgently in patients who have multiple other risk factors that are not assessed by the Marburg Heart Score.

High risk. In patients whose risk is > 70%, invasive testing with angiography should be considered.35,49

EKG abnormalities. Patients with a Marburg Score of 2 or 3 and an abnormal EKG should be sent to the ED (FIGURE). There, patients with a HEART score < 4 and a negative 2-3–hour troponin test have a < 1% chance of ACS and can be safely discharged.31

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected]

1. Chang AM, Fischman DL, Hollander JE. Evaluation of chest pain and acute coronary syndromes. Cardiol Clin. 2018;36:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.001

2. Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. Accessed February 16, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_web_tables.pdf

3. Hsia RY, Hale Z, Tabas JA. A national study of the prevalence of life-threatening diagnoses in patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1029-1032. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2498

4. Ebell MH. Evaluation of chest pain in primary care patients. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:603-605.

5. Hollander JE, Than M, Mueller C. State-of-the-art evaluation of emergency department patients presenting with potential acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2016;134:547-564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021886

6. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, et al. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:1955-1965. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12735

7. Kolminsky J, Choxi R, Mahmoud AR, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: cardiovascular risk stratification and clinical management. American College of Cardiology. June 1, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/06/01/13/54/familial-hypercholesterolemia

8. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al; . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405

9. McConaghy JR, Oza RS. Outpatient diagnosis of acute chest pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:177-182.

10. Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, et al. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA. 1998;280:1256-1263.

11. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:868-877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903515

12. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858-867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428

13. Tada M, Azuma H, Yamada N, et al. A comprehensive validation of very early rule-out strategies for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in emergency departments: protocol for a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026985. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026985

14. Reichlin T, Schindler C, Drexler B, et al. One-hour rule-out and rule-in of acute myocardial infarction using high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1211-1218. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3698

15. Shah AS, Anand A, Sandoval Y, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I at presentation in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:2481-2488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00391-8

16. Chapman AR, Lee KK, McAllister DA, et al. Association of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I concentration with cardiac outcomes in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2017;318:1913-1924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17488

17. Vasile VC, Jaffe AS. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin in the evaluation of possible AMI. American College of Cardiology. July 16, 2018. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2018/07/16/09/17/high-sensitivity-cardiac-troponin-in-the-evaluation-of-possible-am

18. Carlton EW, Khattab A, Greaves K. Identifying patients suitable for discharge after a single-presentation high-sensitivity troponin result: a comparison of five established risk scores and two high-sensitivity assays. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:635-645.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.006

19. Qaseem A, Fihn SD, Williams S, et al; . Diagnosis of stable ischemic heart disease: summary of a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians/American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Preventative Cardiovascular nurses Association/Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:729-734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00010

20. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:2354-2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133

21. Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:701-711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772

22. Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Becker A, et al. Ruling out coronary artery disease in primary care: development and validation of a simple prediction rule. CMAJ. 2010;182:1295-1300. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100212

23. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:191-196. doi: 10.1007/BF03086144

24. Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350-1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402

25. Haasenritter J, Bösner S, Vaucher P, et al. Ruling out coronary heart disease in primary care: external validation of a clinical prediction rule. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e415-e21. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649106

26. Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Aryal S, et al. HEART score risk stratification of low-risk chest pain patients in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:187-203. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.12.010

27. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Prognostic accuracy of the HEART score for prediction of major adverse cardiac events in patients presenting with chest pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26:140-151. doi: 10.1111/acem.13649

28. Sakamoto JT, Liu N, Koh ZX, et al. Comparing HEART, TIMI, and GRACE scores for prediction of 30-day major adverse cardiac events in high acuity chest pain patients in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:759-764. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.147

29. Harskamp RE, Laeven SC, Himmelreich JCL, et al. Chest pain in general practice: a systematic review of prediction rules. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027081. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027081

30. Aerts M, Minalu G, Bösner S, et al. Internal Working Group on Chest Pain in Primary Care (INTERCHEST). Pooled individual patient data from five countries were used to derive a clinical prediction rule for coronary artery disease in primary care. J. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:120-128. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.011

31. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2153-2158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.255

32. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9:164-169. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e3181ec36d8

33. Poldervaart JM, Langedijk M, Backus BE, et al. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:656-661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.080

34. Reaney PDW, Elliott HI, Noman A, et al. Risk stratifying chest pain patients in the emergency department using HEART, GRACE and TIMI scores, with a single contemporary troponin result, to predict major adverse cardiac events. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:420-427. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2017-207172

35. Bittencourt MS, Hulten E, Polonsky TS, et al. European Society of Cardiology-recommended coronary artery disease consortium pretest probability scores more accurately predict obstructive coronary disease and cardiovascular events than the Diamond Forrester score: The Partners Registry. Circulation. 2016;134:201-211. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023396

36. Mordi IR, Badar AA, Irving RJ, et al. Efficacy of noninvasive cardiac imaging tests in diagnosis and management of stable coronary artery disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2017;13:427-437. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S106838

37. Borque JM, Beller GA. Value of exercise ECG for risk stratification in suspected or known CAD in the era of advanced imaging technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1309-1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.006

38. Reinhardt SW, Lin C-J, Novak E, et al. Noninvasive cardiac testing vs clinical evaluation alone in acute chest pain: a secondary analysis of the ROMICAT-II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:212-219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7360

39. Fernandez-Friera L, Garcia-Alvarez A, Bagheriannejad-Esfahani F, et al. Diagnostic value of coronary artery calcium scoring in low-intermediate risk patients evaluated in the emergency department for acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:17-23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.037

40. Linde JJ, H, Hansen TF, et al. Coronary CT angiography in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J AM Coll Cardiol 2020;75:453-463. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.012

41. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation. 2010;122:e525-e555. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fcae66

42. Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Campaign. February 21, 2013. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/SCCT-Choosing-Wisely-List.pdf

43. Hamm CW, Bassand J-P, Agewall S, et al; . ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999-3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236

44. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

45. Ceriani E, Combescure C, Le Gal G, et al. Clinical prediction rules for pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:957-970. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03801.x

46. Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, et al. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in the emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1247-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00790.x

47. Hendriksen JMT, Geersing G-J, Lucassen WAM, et al. Diagnostic prediction models for suspected pulmonary embolism: systematic review and independent external validation in primary care. BMJ. 2015;351:h4438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4438

48. Shen J-H, Chen H-L, Chen J-R, et al. Comparison of the Wells score with the revised Geneva score for assessing suspected pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:482-492. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1250-2

49. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Physicians; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventative Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44-e164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013

One of the most concerning and challenging patient complaints presented to physicians is chest pain. Chest pain is a ubiquitous complaint in primary care settings and in the emergency department (ED), accounting for 8 million ED visits and 0.4% of all primary care visits in North America annually.1,2

Despite the great number of chest-pain encounters, early identification of life-threatening causes and prompt treatment remain a challenge. In this article, we examine how the approach to a complaint of chest pain in a primary care practice (and, likewise, in the ED) must first, rest on the clinical evaluation and second, employ risk-stratification tools to aid in evaluation, appropriate diagnosis, triage, and treatment.

Chest pain by the numbers

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the cause of chest pain in 5.1% of patients with chest pain who present to the ED, compared with 1.5% to 3.1% of chest-pain patients seen in ambulatory care.1,3 “Nonspecific chest pain” is the most frequent diagnosis of chest pain in the ED for all age groups (47.5% to 55.8%).3 In contrast, the most common cause of chest pain in primary care is musculoskeletal (36%), followed by gastrointestinal disease (18% to 19%); serious cardiac causes (15%), including ACS (1.5%); nonspecific causes (16%); psychiatric causes (8%); and pulmonary causes (5% to 10%).4 Among patients seen in the ED because of chest pain, 57.4% are discharged, 30.6% are admitted for further evaluation, and 0.4% die in the ED or after admission.3

First challenge: The scale of the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis of chest pain is broad. It includes life-threatening causes, such as ACS (from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], Type 1 non-STEMI, and unstable angina), acute aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism (PE), esophageal rupture, and tension pneumothorax, as well as non-life-threatening causes (TABLE 1).

History and physical exam guide early decisions

Triage assessment of the patient with chest pain, including vital signs, general appearance, and basic symptom questions, can guide you as to whether they require transfer to a higher level of care. Although an individual’s findings cannot, alone, accurately exclude or diagnose ACS, the findings can be used in combination in clinical decision tools to distinguish noncardiac chest pain from ACS.

History. Features in the history (TABLE 25-9) that are most helpful at increasing the probability (ie, a positive likelihood ratio [LR] ≥ 2) of chest pain being caused by ACS are:

- pain radiating to both arms or the right arm

- pain that is worse upon exertion

- a history of peripheral artery disease or coronary artery disease (CAD)

- a previously abnormal stress test.

The presence of any prior normal stress test is unhelpful: Such patients have a similar risk of a 30-day adverse cardiac event as a patient who has never had a stress test.5

Continue to: A history of tobacco use...

A history of tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery bypass grafting, or a family history of CAD does not significantly increase the risk of ACS.6 However, exploring each of these risk factors further is important, because genetic links between these risk factors can lead to an increased risk of CAD (eg, familial hypercholesterolemia).7

A history of normal or near-normal coronary angiography (< 25% stenosis) is associated with a lower likelihood of ACS, because 98% of such patients are free of AMI and 90% are without single-vessel coronary disease nearly 10 years out.6 A history of coronary artery bypass grafting is not necessarily predictive of ACS (LR = 1-3).5,6

Historical features classically associated with ACS, but that have an LR < 2, are pain radiating to the neck or jaw, nausea or vomiting, dyspnea, and pain that is relieved with nitroglycerin.5,6 Pain described as pleuritic, sharp, positional, or reproduced with palpation is less likely due to AMI.5

Physical exam findings are not independently diagnostic when evaluating chest pain. However, a third heart sound is the most likely finding associated with AMI and hypotension is the clinical sign most likely associated with ACS.5

Consider the diagnosis of PE in all patients with chest pain. In PE, chest pain might be associated with dyspnea, presyncope, syncope, or hemoptysis.8 On examination, 40% of patients have tachycardia.8 If PE is suspected; the patient should be risk-stratified using a validated prediction rule (see the discussion of PE that follows).

Continue to: Other historical features...

Other historical features or physical exam findings correlate with aortic dissection, pneumonia, and psychiatric causes of chest pain (TABLE 25-9).

Useful EKG findings

Among patients in whom ACS or PE is suspected, 12-lead electrocardiography (EKG) should be performed.

AMI. EKG findings most predictive of AMI are new ST-segment elevation or depression > 1 mm (LR = 6-54), new left bundle branch block (LR = 6.3), Q wave (positive LR = 3.9), and prominent, wide-based (hyperacute) T wave (LR = 3.1).10

ACS. Useful EKG findings to predict ACS are ST-segment depression (LR = 5.3 [95% CI, 2.1-8.6]) and any evidence of ischemia, defined as ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, or Q wave (LR = 3.6 [95% CI, 1.6-5.7]).10

PE. The most common abnormal finding on EKG in the setting of PE is sinus tachycardia.

Continue to: Right ventricular strain

Right ventricular strain. Other findings that reflect right ventricular strain, but are much less common, are complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, prominent S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III, and T-wave inversion in lead III (S1Q3T3; the McGinn-White sign) and in leads V1-V4.8

The utility of troponin and high-sensitivity troponin testing

Clinical evaluation and EKG findings are unable to diagnose or exclude ACS without the use of the cardiac biomarker troponin. In the past decade, high-sensitivity troponin assays have been used to stratify patients at risk of ACS.11,12 Many protocols now exist using short interval (2-3 hours), high-sensitivity troponin testing to identify patients at low risk of myocardial infarction who can be safely discharged from the ED after 2 normal tests of the troponin level.13-16

An elevated troponin value alone, however, is not a specific indicator of ACS; troponin can be elevated in the settings of myocardial ischemia related to increased oxygen demand (Type 2 non-STEMI) and decreased renal clearance. Consideration of the rate of rising and falling levels of troponin, its absolute value > 99th percentile, and other findings is critical to interpreting an elevated troponin level.17 Studies in which the HEART score (History, Electrocardiography, Age, Risk factors, Troponin) was combined with high-sensitivity troponin measurement show that this pairing is promising in reducing unnecessary admissions for chest pain.18 (For a description of this tool, see the discussion of the HEART score that follows.) Carlton and colleagues18 showed that a HEART score ≤ 3 and a negative high-sensitivity troponin I level had a negative predictive value of ≥ 99.5% for AMI.

Clinical decision tools: Who needs care? Who can go home?

Given the varied presentations of patients with life-threatening causes of chest pain, it is challenging to confidently determine who is safe to send home after initial assessment. Guidance in 2014 from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology recommends risk-stratifying patients for ACS using clinical decision tools to help guide management.19,20 The American College of Physicians, in its 2015 guidelines, also recommends using a clinical decision tool to assess patients when there is suspicion of PE.21 Clinical application of these tools identifies patients at low risk of life-threatening conditions and can help avoid unnecessary intervention and a higher level of care.

Tools for investigating ACS

The Marburg Heart Score22 assesses the likelihood of CAD in ambulatory settings while the HEART score assesses the risk of major adverse cardiac events in ED patients.23 The Diamond Forrester criteria can be used to assess the pretest probability of CAD in both settings.24

Continue to: Marburg Heart Score

Marburg Heart Score. Validated in patients older than 35 years of age in 2 different outpatient populations in 201022 and 2012,25 the Marburg score is determined by answering 5 questions:

- Female ≥ 65 years? Or male ≥ 55 years of age? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Known CAD, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain worse with exercise? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain reproducible with palpation? (No, +1, Yes, 0)

- Does the patient assume that the pain is cardiac in nature? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

A Marburg Heart Score of 0 or 1 means CAD is highly unlikely in a patient with chest pain (negative predictive value = 99%-100%; positive predictive value = 0.6%)4 (TABLE 34,26-28). A score of ≤ 2 has a negative predictive value of 98%. A Marburg Heart Score of 4 or 5 has a relatively low positive predictive value (63%).4

This tool does not accurately diagnose acute MI, but it does help identify patients at low risk of ACS, thus reducing unnecessary subsequent testing. Although no clinical decision tool can rule out AMI with absolute certainty, the Marburg Heart Score is considered one of the most extensively tested and sensitive tools to predict low risk of CAD in outpatient primary care.29

INTERCHEST rule (in outpatient primary care) is a newer prediction rule using data from 5 primary care–based studies of chest pain.30 For a score ≤ 2, the negative predictive value for CAD causing chest pain is 97% to 98% and the positive predictive value is 43%. INTERCHEST incorporates studies used to validate the Marburg Heart Score, but has not been validated beyond initial pooled studies. Concerns have been raised about the quality of these pooled studies, however, and this rule has not been widely accepted for clinical use at this time.29

The HEART score has been validated in patients older than 12 years in multiple institutions and across multiple ED populations.23,31,32 It is widely used in the ED to assess a patient’s risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over the next 6 weeks. MACE is defined as AMI, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or death.

Continue to: The HEART score...

The HEART score is calculated based on 5 components:

- History of chest pain (slightly [0], moderately [+1], or highly [+2]) suspicious for ACS)

- EKG (normal [0], nonspecific ST changes [+1], significant ST deviations [+2])

- Age (< 45 y [0], 45-64 y [+1], ≥ 65 y [+2])

- Risk factors (none [0], 1 or 2 [+1], ≥ 3 or a history of atherosclerotic disease [+2]) a

- Initial troponin assay, standard sensitivity (≤ normal [0], 1-3× normal [+1], > 3× normal [+2]).

For patients with a HEART score of 0-3 (ie, at low risk), the pooled positive predictive value of a MACE was determined to be 0.19 (95% CI, 0.14-0.24), and the negative predictive value was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98-0.99)—making it an effective tool to rule out a MACE over the short term26 (TABLE 34,26-28).

Because the HEART Score was published in 2008, multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compared it to the TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) and GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) scores for predicting short-term (30-day to 6-week) MACE in ED patients.27,28,33,34 These studies have all shown that the HEART score is relatively superior to the TIMI and GRACE tools.

Characteristics of these tools are summarized in TABLE 3.4,26-28

Diamond Forrester classification (in ED and outpatient settings). This tool uses 3 criteria—substernal chest pain, pain that increases upon exertion or with stress, and pain relieved by nitroglycerin or rest—to classify chest pain as typical angina (all 3 criteria), atypical angina (2 criteria), or noncardiac chest pain (0 criteria or 1 criterion).24 Pretest probability (ie, the likelihood of an outcome before noninvasive testing) of the pain being due to CAD can then be determined from the type of chest pain and the patient’s gender and age19 (TABLE 419). Recent studies have found that the Diamond Forrester criteria might overestimate the probability of CAD.35

Continue to: Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Positron-emission tomography stress testing, stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion scanning, exercise treadmill testing. The first 3 of these imaging tests have a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 74% to 87%36; exercise treadmill testing is less sensitive (68%) and specific (77%).37

In a patient with a very low (< 5%) probability of CAD, a positive stress test (of any modality) is likely to be a false-positive; conversely, in a patient with a very high (> 90%) probability of CAD, a negative stress test is likely to be a false-negative.19 The American Heart Association, therefore, does not recommend any of these modalities for patients who have a < 5% or > 90% probability of CAD.19

Noninvasive testing to rule out ACS in low- and intermediate-risk patients who present to the ED with chest pain provides no clinical benefit over clinical evaluation alone.38 Therefore, these tests are rarely used in the initial evaluation of chest pain in an acute setting.

Coronary artery calcium score (CACS), coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). These tests have demonstrated promise in the risk stratification of chest pain, given their high sensitivity and negative predictive value in low- and intermediate-risk patients.39,40 However, their application remains unclear in the evaluation of acute chest pain: Appropriate-use criteria do not favor CACS or CCTA alone to evaluate acute chest pain when there is suspicion of ACS.41 The Choosing Wisely initiative (for “avoiding unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures”; www.choosingwisely.org) recommends against CCTA for high-risk patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain.42

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging does not have an established role in the evaluation of patients with suspected ACS.43

Continue to: Tools for investigating PE

Tools for investigating PE

Three clinical decision tools have been validated to predict the risk of PE: the Wells score, the Geneva score, and Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria (PERC).44,45

Wells score is more sensitive than the Geneva score and has been validated in ambulatory1 and ED46-48 settings. Based on Wells criteria, high-risk patients need further evaluation with imaging. In low-risk patients, a normal D-dimer level effectively excludes PE, with a < 1% risk of subsequent thromboembolism in the following 3 months. Positive predictive value of the Wells decision tool is low because it is intended to rule out, not confirm, PE.

PERC can be used in a low-probability setting (defined as the treating physician arriving at the conclusion that PE is not the most likely diagnosis and can be excluded with a negative D-dimer test). In that setting, if the patient meets the 8 clinical variables in PERC, the diagnosis of PE is, effectively, ruled out.48

Summing up: Evaluation of chest pain guided by risk of CAD

Patients who present in an outpatient setting with a potentially life-threatening cause of chest pain (TABLE 1) and patients with unstable vital signs should be sent to the ED for urgent evaluation. In the remaining outpatients, use the Marburg Heart Score or Diamond Forrester classification to assess the likelihood that pain is due to CAD (in the ED, the HEART score can be used for this purpose) (FIGURE).

When the risk is low. No further cardiac testing is indicated in patients with a risk of CAD < 5%, based on a Marburg score of 0 or 1, or on Diamond Forrester criteria; an abnormal stress test is likely to be a false-positive.19

Continue to: Moderate risk

Moderate risk. However, further testing is indicated, with a stress test (with or without myocardial imaging), in patients whose risk of CAD is 5% to 70%, based on the Diamond Forrester classification or an intermediate Marburg Heart Score (ie, a score of 2 or 3 but a normal EKG). This further testing can be performed urgently in patients who have multiple other risk factors that are not assessed by the Marburg Heart Score.

High risk. In patients whose risk is > 70%, invasive testing with angiography should be considered.35,49

EKG abnormalities. Patients with a Marburg Score of 2 or 3 and an abnormal EKG should be sent to the ED (FIGURE). There, patients with a HEART score < 4 and a negative 2-3–hour troponin test have a < 1% chance of ACS and can be safely discharged.31

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected]

One of the most concerning and challenging patient complaints presented to physicians is chest pain. Chest pain is a ubiquitous complaint in primary care settings and in the emergency department (ED), accounting for 8 million ED visits and 0.4% of all primary care visits in North America annually.1,2

Despite the great number of chest-pain encounters, early identification of life-threatening causes and prompt treatment remain a challenge. In this article, we examine how the approach to a complaint of chest pain in a primary care practice (and, likewise, in the ED) must first, rest on the clinical evaluation and second, employ risk-stratification tools to aid in evaluation, appropriate diagnosis, triage, and treatment.

Chest pain by the numbers

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the cause of chest pain in 5.1% of patients with chest pain who present to the ED, compared with 1.5% to 3.1% of chest-pain patients seen in ambulatory care.1,3 “Nonspecific chest pain” is the most frequent diagnosis of chest pain in the ED for all age groups (47.5% to 55.8%).3 In contrast, the most common cause of chest pain in primary care is musculoskeletal (36%), followed by gastrointestinal disease (18% to 19%); serious cardiac causes (15%), including ACS (1.5%); nonspecific causes (16%); psychiatric causes (8%); and pulmonary causes (5% to 10%).4 Among patients seen in the ED because of chest pain, 57.4% are discharged, 30.6% are admitted for further evaluation, and 0.4% die in the ED or after admission.3

First challenge: The scale of the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis of chest pain is broad. It includes life-threatening causes, such as ACS (from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], Type 1 non-STEMI, and unstable angina), acute aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism (PE), esophageal rupture, and tension pneumothorax, as well as non-life-threatening causes (TABLE 1).

History and physical exam guide early decisions

Triage assessment of the patient with chest pain, including vital signs, general appearance, and basic symptom questions, can guide you as to whether they require transfer to a higher level of care. Although an individual’s findings cannot, alone, accurately exclude or diagnose ACS, the findings can be used in combination in clinical decision tools to distinguish noncardiac chest pain from ACS.

History. Features in the history (TABLE 25-9) that are most helpful at increasing the probability (ie, a positive likelihood ratio [LR] ≥ 2) of chest pain being caused by ACS are:

- pain radiating to both arms or the right arm

- pain that is worse upon exertion

- a history of peripheral artery disease or coronary artery disease (CAD)

- a previously abnormal stress test.

The presence of any prior normal stress test is unhelpful: Such patients have a similar risk of a 30-day adverse cardiac event as a patient who has never had a stress test.5

Continue to: A history of tobacco use...

A history of tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery bypass grafting, or a family history of CAD does not significantly increase the risk of ACS.6 However, exploring each of these risk factors further is important, because genetic links between these risk factors can lead to an increased risk of CAD (eg, familial hypercholesterolemia).7

A history of normal or near-normal coronary angiography (< 25% stenosis) is associated with a lower likelihood of ACS, because 98% of such patients are free of AMI and 90% are without single-vessel coronary disease nearly 10 years out.6 A history of coronary artery bypass grafting is not necessarily predictive of ACS (LR = 1-3).5,6

Historical features classically associated with ACS, but that have an LR < 2, are pain radiating to the neck or jaw, nausea or vomiting, dyspnea, and pain that is relieved with nitroglycerin.5,6 Pain described as pleuritic, sharp, positional, or reproduced with palpation is less likely due to AMI.5

Physical exam findings are not independently diagnostic when evaluating chest pain. However, a third heart sound is the most likely finding associated with AMI and hypotension is the clinical sign most likely associated with ACS.5

Consider the diagnosis of PE in all patients with chest pain. In PE, chest pain might be associated with dyspnea, presyncope, syncope, or hemoptysis.8 On examination, 40% of patients have tachycardia.8 If PE is suspected; the patient should be risk-stratified using a validated prediction rule (see the discussion of PE that follows).

Continue to: Other historical features...

Other historical features or physical exam findings correlate with aortic dissection, pneumonia, and psychiatric causes of chest pain (TABLE 25-9).

Useful EKG findings

Among patients in whom ACS or PE is suspected, 12-lead electrocardiography (EKG) should be performed.

AMI. EKG findings most predictive of AMI are new ST-segment elevation or depression > 1 mm (LR = 6-54), new left bundle branch block (LR = 6.3), Q wave (positive LR = 3.9), and prominent, wide-based (hyperacute) T wave (LR = 3.1).10

ACS. Useful EKG findings to predict ACS are ST-segment depression (LR = 5.3 [95% CI, 2.1-8.6]) and any evidence of ischemia, defined as ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, or Q wave (LR = 3.6 [95% CI, 1.6-5.7]).10

PE. The most common abnormal finding on EKG in the setting of PE is sinus tachycardia.

Continue to: Right ventricular strain

Right ventricular strain. Other findings that reflect right ventricular strain, but are much less common, are complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, prominent S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III, and T-wave inversion in lead III (S1Q3T3; the McGinn-White sign) and in leads V1-V4.8

The utility of troponin and high-sensitivity troponin testing

Clinical evaluation and EKG findings are unable to diagnose or exclude ACS without the use of the cardiac biomarker troponin. In the past decade, high-sensitivity troponin assays have been used to stratify patients at risk of ACS.11,12 Many protocols now exist using short interval (2-3 hours), high-sensitivity troponin testing to identify patients at low risk of myocardial infarction who can be safely discharged from the ED after 2 normal tests of the troponin level.13-16

An elevated troponin value alone, however, is not a specific indicator of ACS; troponin can be elevated in the settings of myocardial ischemia related to increased oxygen demand (Type 2 non-STEMI) and decreased renal clearance. Consideration of the rate of rising and falling levels of troponin, its absolute value > 99th percentile, and other findings is critical to interpreting an elevated troponin level.17 Studies in which the HEART score (History, Electrocardiography, Age, Risk factors, Troponin) was combined with high-sensitivity troponin measurement show that this pairing is promising in reducing unnecessary admissions for chest pain.18 (For a description of this tool, see the discussion of the HEART score that follows.) Carlton and colleagues18 showed that a HEART score ≤ 3 and a negative high-sensitivity troponin I level had a negative predictive value of ≥ 99.5% for AMI.

Clinical decision tools: Who needs care? Who can go home?

Given the varied presentations of patients with life-threatening causes of chest pain, it is challenging to confidently determine who is safe to send home after initial assessment. Guidance in 2014 from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology recommends risk-stratifying patients for ACS using clinical decision tools to help guide management.19,20 The American College of Physicians, in its 2015 guidelines, also recommends using a clinical decision tool to assess patients when there is suspicion of PE.21 Clinical application of these tools identifies patients at low risk of life-threatening conditions and can help avoid unnecessary intervention and a higher level of care.

Tools for investigating ACS

The Marburg Heart Score22 assesses the likelihood of CAD in ambulatory settings while the HEART score assesses the risk of major adverse cardiac events in ED patients.23 The Diamond Forrester criteria can be used to assess the pretest probability of CAD in both settings.24

Continue to: Marburg Heart Score

Marburg Heart Score. Validated in patients older than 35 years of age in 2 different outpatient populations in 201022 and 2012,25 the Marburg score is determined by answering 5 questions:

- Female ≥ 65 years? Or male ≥ 55 years of age? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Known CAD, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain worse with exercise? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

- Is pain reproducible with palpation? (No, +1, Yes, 0)

- Does the patient assume that the pain is cardiac in nature? (No, 0; Yes, +1)

A Marburg Heart Score of 0 or 1 means CAD is highly unlikely in a patient with chest pain (negative predictive value = 99%-100%; positive predictive value = 0.6%)4 (TABLE 34,26-28). A score of ≤ 2 has a negative predictive value of 98%. A Marburg Heart Score of 4 or 5 has a relatively low positive predictive value (63%).4

This tool does not accurately diagnose acute MI, but it does help identify patients at low risk of ACS, thus reducing unnecessary subsequent testing. Although no clinical decision tool can rule out AMI with absolute certainty, the Marburg Heart Score is considered one of the most extensively tested and sensitive tools to predict low risk of CAD in outpatient primary care.29

INTERCHEST rule (in outpatient primary care) is a newer prediction rule using data from 5 primary care–based studies of chest pain.30 For a score ≤ 2, the negative predictive value for CAD causing chest pain is 97% to 98% and the positive predictive value is 43%. INTERCHEST incorporates studies used to validate the Marburg Heart Score, but has not been validated beyond initial pooled studies. Concerns have been raised about the quality of these pooled studies, however, and this rule has not been widely accepted for clinical use at this time.29

The HEART score has been validated in patients older than 12 years in multiple institutions and across multiple ED populations.23,31,32 It is widely used in the ED to assess a patient’s risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over the next 6 weeks. MACE is defined as AMI, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or death.

Continue to: The HEART score...

The HEART score is calculated based on 5 components:

- History of chest pain (slightly [0], moderately [+1], or highly [+2]) suspicious for ACS)

- EKG (normal [0], nonspecific ST changes [+1], significant ST deviations [+2])

- Age (< 45 y [0], 45-64 y [+1], ≥ 65 y [+2])

- Risk factors (none [0], 1 or 2 [+1], ≥ 3 or a history of atherosclerotic disease [+2]) a

- Initial troponin assay, standard sensitivity (≤ normal [0], 1-3× normal [+1], > 3× normal [+2]).

For patients with a HEART score of 0-3 (ie, at low risk), the pooled positive predictive value of a MACE was determined to be 0.19 (95% CI, 0.14-0.24), and the negative predictive value was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98-0.99)—making it an effective tool to rule out a MACE over the short term26 (TABLE 34,26-28).

Because the HEART Score was published in 2008, multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compared it to the TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) and GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) scores for predicting short-term (30-day to 6-week) MACE in ED patients.27,28,33,34 These studies have all shown that the HEART score is relatively superior to the TIMI and GRACE tools.

Characteristics of these tools are summarized in TABLE 3.4,26-28

Diamond Forrester classification (in ED and outpatient settings). This tool uses 3 criteria—substernal chest pain, pain that increases upon exertion or with stress, and pain relieved by nitroglycerin or rest—to classify chest pain as typical angina (all 3 criteria), atypical angina (2 criteria), or noncardiac chest pain (0 criteria or 1 criterion).24 Pretest probability (ie, the likelihood of an outcome before noninvasive testing) of the pain being due to CAD can then be determined from the type of chest pain and the patient’s gender and age19 (TABLE 419). Recent studies have found that the Diamond Forrester criteria might overestimate the probability of CAD.35

Continue to: Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Noninvasive imaging-based diagnostic methods

Positron-emission tomography stress testing, stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion scanning, exercise treadmill testing. The first 3 of these imaging tests have a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 74% to 87%36; exercise treadmill testing is less sensitive (68%) and specific (77%).37

In a patient with a very low (< 5%) probability of CAD, a positive stress test (of any modality) is likely to be a false-positive; conversely, in a patient with a very high (> 90%) probability of CAD, a negative stress test is likely to be a false-negative.19 The American Heart Association, therefore, does not recommend any of these modalities for patients who have a < 5% or > 90% probability of CAD.19

Noninvasive testing to rule out ACS in low- and intermediate-risk patients who present to the ED with chest pain provides no clinical benefit over clinical evaluation alone.38 Therefore, these tests are rarely used in the initial evaluation of chest pain in an acute setting.

Coronary artery calcium score (CACS), coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). These tests have demonstrated promise in the risk stratification of chest pain, given their high sensitivity and negative predictive value in low- and intermediate-risk patients.39,40 However, their application remains unclear in the evaluation of acute chest pain: Appropriate-use criteria do not favor CACS or CCTA alone to evaluate acute chest pain when there is suspicion of ACS.41 The Choosing Wisely initiative (for “avoiding unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures”; www.choosingwisely.org) recommends against CCTA for high-risk patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain.42

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging does not have an established role in the evaluation of patients with suspected ACS.43

Continue to: Tools for investigating PE

Tools for investigating PE

Three clinical decision tools have been validated to predict the risk of PE: the Wells score, the Geneva score, and Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria (PERC).44,45

Wells score is more sensitive than the Geneva score and has been validated in ambulatory1 and ED46-48 settings. Based on Wells criteria, high-risk patients need further evaluation with imaging. In low-risk patients, a normal D-dimer level effectively excludes PE, with a < 1% risk of subsequent thromboembolism in the following 3 months. Positive predictive value of the Wells decision tool is low because it is intended to rule out, not confirm, PE.

PERC can be used in a low-probability setting (defined as the treating physician arriving at the conclusion that PE is not the most likely diagnosis and can be excluded with a negative D-dimer test). In that setting, if the patient meets the 8 clinical variables in PERC, the diagnosis of PE is, effectively, ruled out.48

Summing up: Evaluation of chest pain guided by risk of CAD

Patients who present in an outpatient setting with a potentially life-threatening cause of chest pain (TABLE 1) and patients with unstable vital signs should be sent to the ED for urgent evaluation. In the remaining outpatients, use the Marburg Heart Score or Diamond Forrester classification to assess the likelihood that pain is due to CAD (in the ED, the HEART score can be used for this purpose) (FIGURE).

When the risk is low. No further cardiac testing is indicated in patients with a risk of CAD < 5%, based on a Marburg score of 0 or 1, or on Diamond Forrester criteria; an abnormal stress test is likely to be a false-positive.19

Continue to: Moderate risk

Moderate risk. However, further testing is indicated, with a stress test (with or without myocardial imaging), in patients whose risk of CAD is 5% to 70%, based on the Diamond Forrester classification or an intermediate Marburg Heart Score (ie, a score of 2 or 3 but a normal EKG). This further testing can be performed urgently in patients who have multiple other risk factors that are not assessed by the Marburg Heart Score.

High risk. In patients whose risk is > 70%, invasive testing with angiography should be considered.35,49

EKG abnormalities. Patients with a Marburg Score of 2 or 3 and an abnormal EKG should be sent to the ED (FIGURE). There, patients with a HEART score < 4 and a negative 2-3–hour troponin test have a < 1% chance of ACS and can be safely discharged.31

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected]

1. Chang AM, Fischman DL, Hollander JE. Evaluation of chest pain and acute coronary syndromes. Cardiol Clin. 2018;36:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.001

2. Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. Accessed February 16, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_web_tables.pdf

3. Hsia RY, Hale Z, Tabas JA. A national study of the prevalence of life-threatening diagnoses in patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1029-1032. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2498

4. Ebell MH. Evaluation of chest pain in primary care patients. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:603-605.

5. Hollander JE, Than M, Mueller C. State-of-the-art evaluation of emergency department patients presenting with potential acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2016;134:547-564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021886

6. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, et al. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:1955-1965. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12735

7. Kolminsky J, Choxi R, Mahmoud AR, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: cardiovascular risk stratification and clinical management. American College of Cardiology. June 1, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/06/01/13/54/familial-hypercholesterolemia

8. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al; . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405

9. McConaghy JR, Oza RS. Outpatient diagnosis of acute chest pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:177-182.

10. Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, et al. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA. 1998;280:1256-1263.

11. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:868-877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903515

12. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858-867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428

13. Tada M, Azuma H, Yamada N, et al. A comprehensive validation of very early rule-out strategies for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in emergency departments: protocol for a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026985. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026985

14. Reichlin T, Schindler C, Drexler B, et al. One-hour rule-out and rule-in of acute myocardial infarction using high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1211-1218. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3698

15. Shah AS, Anand A, Sandoval Y, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I at presentation in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:2481-2488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00391-8

16. Chapman AR, Lee KK, McAllister DA, et al. Association of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I concentration with cardiac outcomes in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2017;318:1913-1924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17488

17. Vasile VC, Jaffe AS. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin in the evaluation of possible AMI. American College of Cardiology. July 16, 2018. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2018/07/16/09/17/high-sensitivity-cardiac-troponin-in-the-evaluation-of-possible-am

18. Carlton EW, Khattab A, Greaves K. Identifying patients suitable for discharge after a single-presentation high-sensitivity troponin result: a comparison of five established risk scores and two high-sensitivity assays. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:635-645.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.006

19. Qaseem A, Fihn SD, Williams S, et al; . Diagnosis of stable ischemic heart disease: summary of a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians/American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Preventative Cardiovascular nurses Association/Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:729-734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00010

20. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:2354-2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133

21. Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:701-711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772

22. Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Becker A, et al. Ruling out coronary artery disease in primary care: development and validation of a simple prediction rule. CMAJ. 2010;182:1295-1300. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100212

23. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:191-196. doi: 10.1007/BF03086144

24. Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350-1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402

25. Haasenritter J, Bösner S, Vaucher P, et al. Ruling out coronary heart disease in primary care: external validation of a clinical prediction rule. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e415-e21. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649106

26. Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Aryal S, et al. HEART score risk stratification of low-risk chest pain patients in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:187-203. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.12.010

27. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Prognostic accuracy of the HEART score for prediction of major adverse cardiac events in patients presenting with chest pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26:140-151. doi: 10.1111/acem.13649

28. Sakamoto JT, Liu N, Koh ZX, et al. Comparing HEART, TIMI, and GRACE scores for prediction of 30-day major adverse cardiac events in high acuity chest pain patients in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:759-764. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.147

29. Harskamp RE, Laeven SC, Himmelreich JCL, et al. Chest pain in general practice: a systematic review of prediction rules. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027081. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027081

30. Aerts M, Minalu G, Bösner S, et al. Internal Working Group on Chest Pain in Primary Care (INTERCHEST). Pooled individual patient data from five countries were used to derive a clinical prediction rule for coronary artery disease in primary care. J. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:120-128. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.011

31. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2153-2158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.255

32. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9:164-169. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e3181ec36d8

33. Poldervaart JM, Langedijk M, Backus BE, et al. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:656-661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.080

34. Reaney PDW, Elliott HI, Noman A, et al. Risk stratifying chest pain patients in the emergency department using HEART, GRACE and TIMI scores, with a single contemporary troponin result, to predict major adverse cardiac events. Emerg Med J. 2018;35:420-427. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2017-207172

35. Bittencourt MS, Hulten E, Polonsky TS, et al. European Society of Cardiology-recommended coronary artery disease consortium pretest probability scores more accurately predict obstructive coronary disease and cardiovascular events than the Diamond Forrester score: The Partners Registry. Circulation. 2016;134:201-211. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023396

36. Mordi IR, Badar AA, Irving RJ, et al. Efficacy of noninvasive cardiac imaging tests in diagnosis and management of stable coronary artery disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2017;13:427-437. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S106838

37. Borque JM, Beller GA. Value of exercise ECG for risk stratification in suspected or known CAD in the era of advanced imaging technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1309-1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.006

38. Reinhardt SW, Lin C-J, Novak E, et al. Noninvasive cardiac testing vs clinical evaluation alone in acute chest pain: a secondary analysis of the ROMICAT-II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:212-219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7360

39. Fernandez-Friera L, Garcia-Alvarez A, Bagheriannejad-Esfahani F, et al. Diagnostic value of coronary artery calcium scoring in low-intermediate risk patients evaluated in the emergency department for acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:17-23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.037

40. Linde JJ, H, Hansen TF, et al. Coronary CT angiography in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J AM Coll Cardiol 2020;75:453-463. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.012

41. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation. 2010;122:e525-e555. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fcae66

42. Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Campaign. February 21, 2013. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/SCCT-Choosing-Wisely-List.pdf

43. Hamm CW, Bassand J-P, Agewall S, et al; . ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999-3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236

44. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

45. Ceriani E, Combescure C, Le Gal G, et al. Clinical prediction rules for pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:957-970. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03801.x

46. Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, et al. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in the emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1247-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00790.x

47. Hendriksen JMT, Geersing G-J, Lucassen WAM, et al. Diagnostic prediction models for suspected pulmonary embolism: systematic review and independent external validation in primary care. BMJ. 2015;351:h4438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4438

48. Shen J-H, Chen H-L, Chen J-R, et al. Comparison of the Wells score with the revised Geneva score for assessing suspected pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:482-492. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1250-2

49. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Physicians; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventative Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44-e164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013

1. Chang AM, Fischman DL, Hollander JE. Evaluation of chest pain and acute coronary syndromes. Cardiol Clin. 2018;36:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.001

2. Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. Accessed February 16, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_web_tables.pdf

3. Hsia RY, Hale Z, Tabas JA. A national study of the prevalence of life-threatening diagnoses in patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1029-1032. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2498

4. Ebell MH. Evaluation of chest pain in primary care patients. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:603-605.

5. Hollander JE, Than M, Mueller C. State-of-the-art evaluation of emergency department patients presenting with potential acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2016;134:547-564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021886

6. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, et al. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:1955-1965. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12735

7. Kolminsky J, Choxi R, Mahmoud AR, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: cardiovascular risk stratification and clinical management. American College of Cardiology. June 1, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/06/01/13/54/familial-hypercholesterolemia

8. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al; . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405