User login

Multiple Nodules on the Scrotum

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

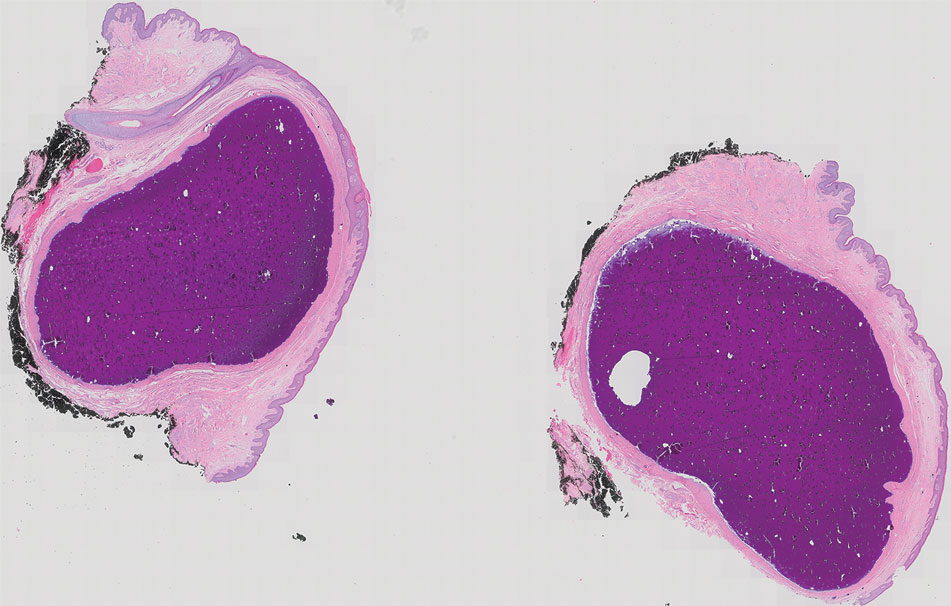

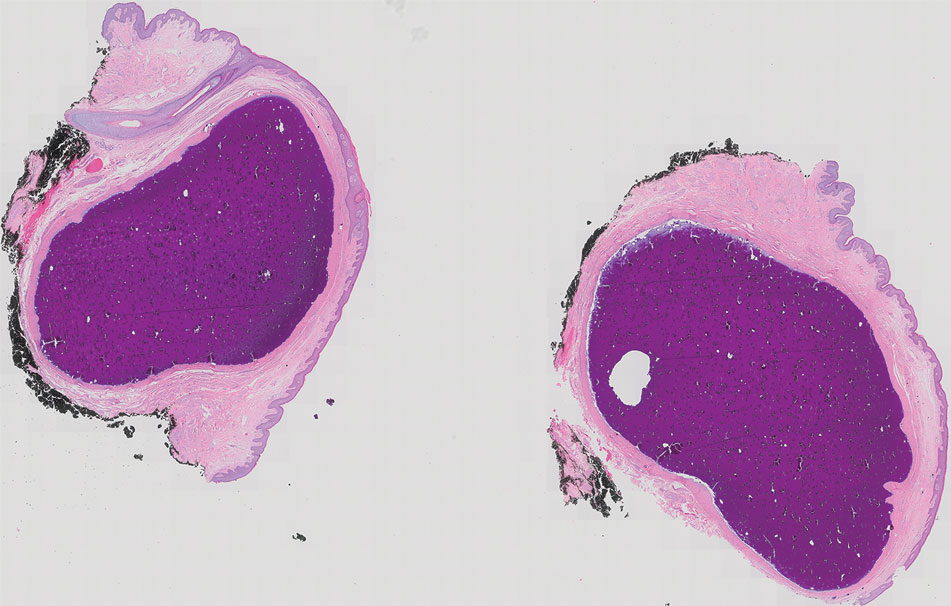

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

A 33-year-old man presented with progressively enlarging bumps on the scrotum that were present since adolescence. He had a history of hyperlipidemia but no history of systemic or autoimmune disease. The lesions were asymptomatic without associated pruritus, pain, or discharge. No treatments had been administered, and he had no known personal or family history of similar skin conditions or skin cancer. He endorsed a monogamous relationship with his wife. Physical examination revealed 15 firm, yellow-white, subcutaneous nodules on the scrotum that varied in size.

Combined Treatment of Disfiguring Facial Angiofibromas in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex With Surgical Debulking and Topical Sirolimus

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

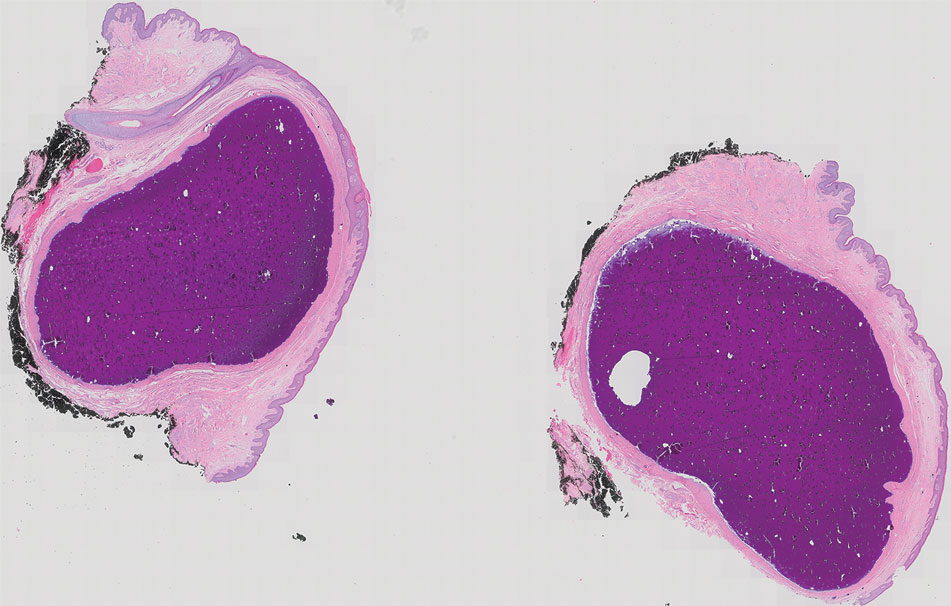

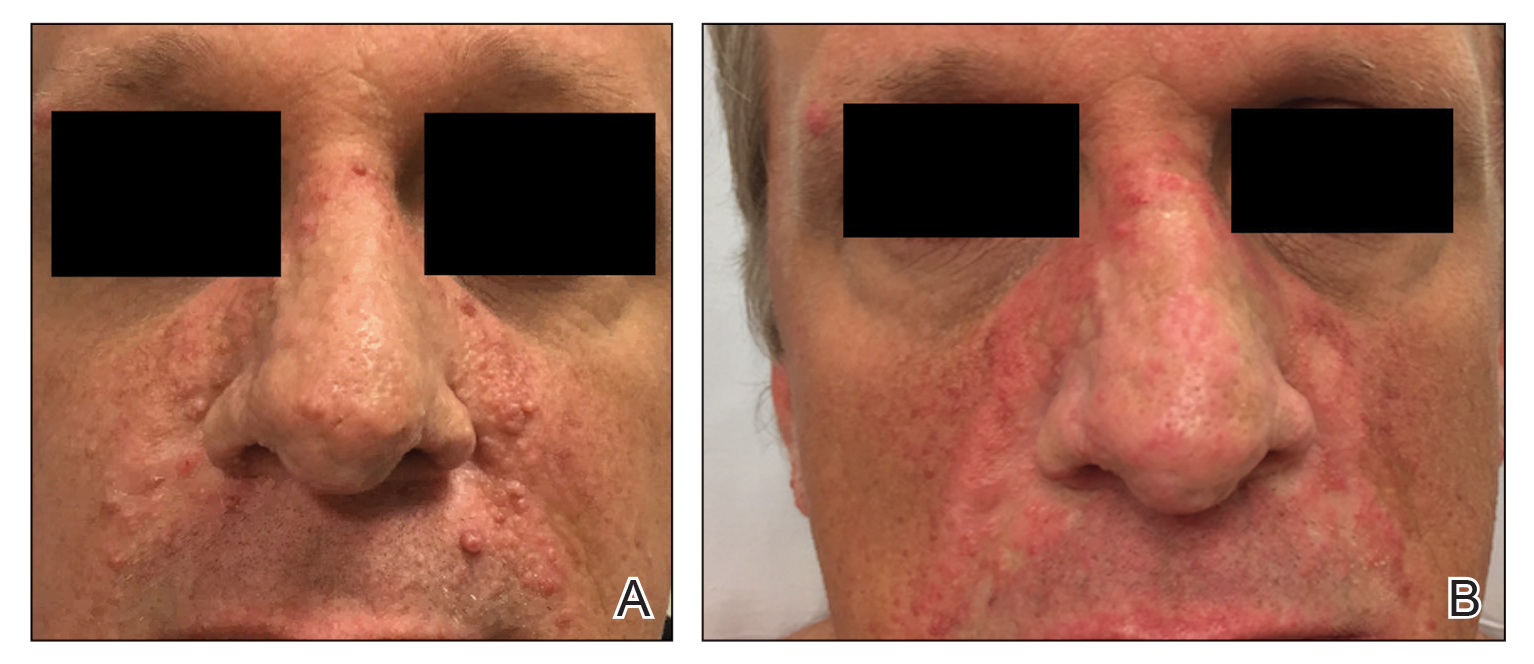

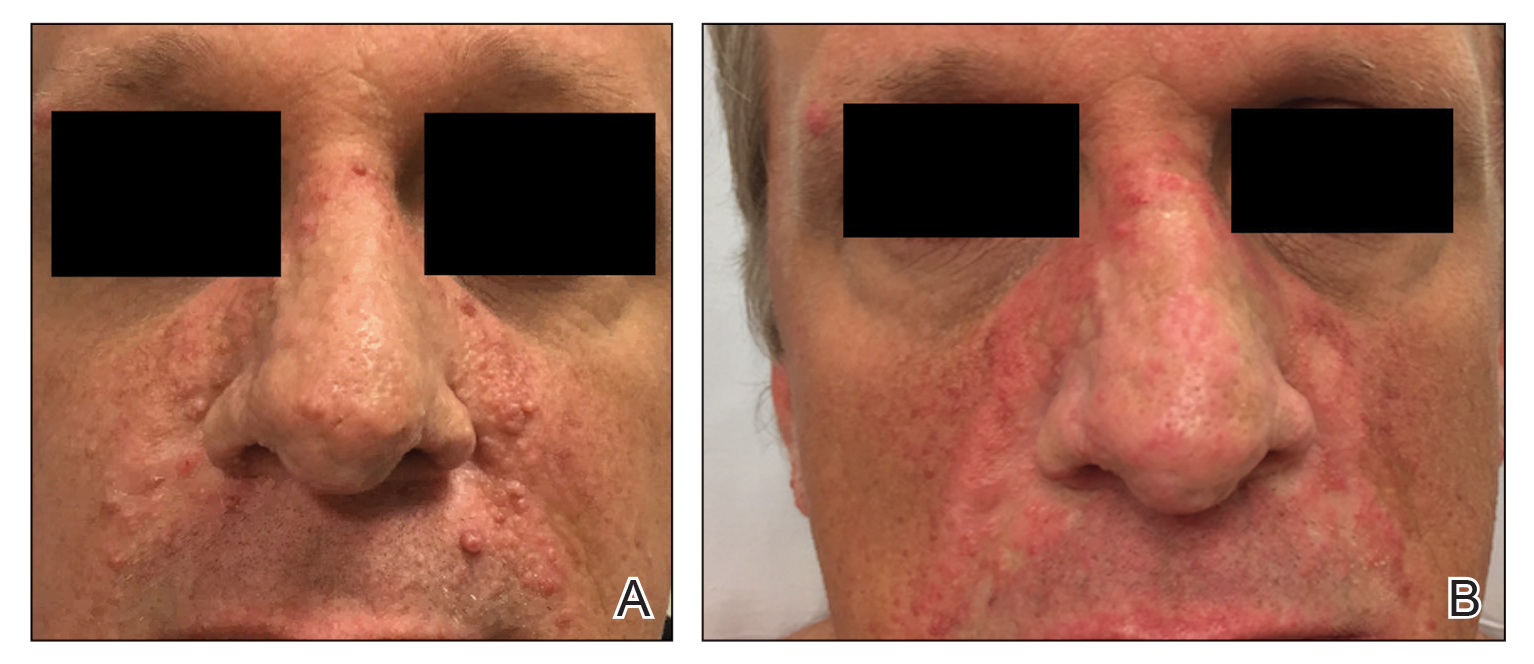

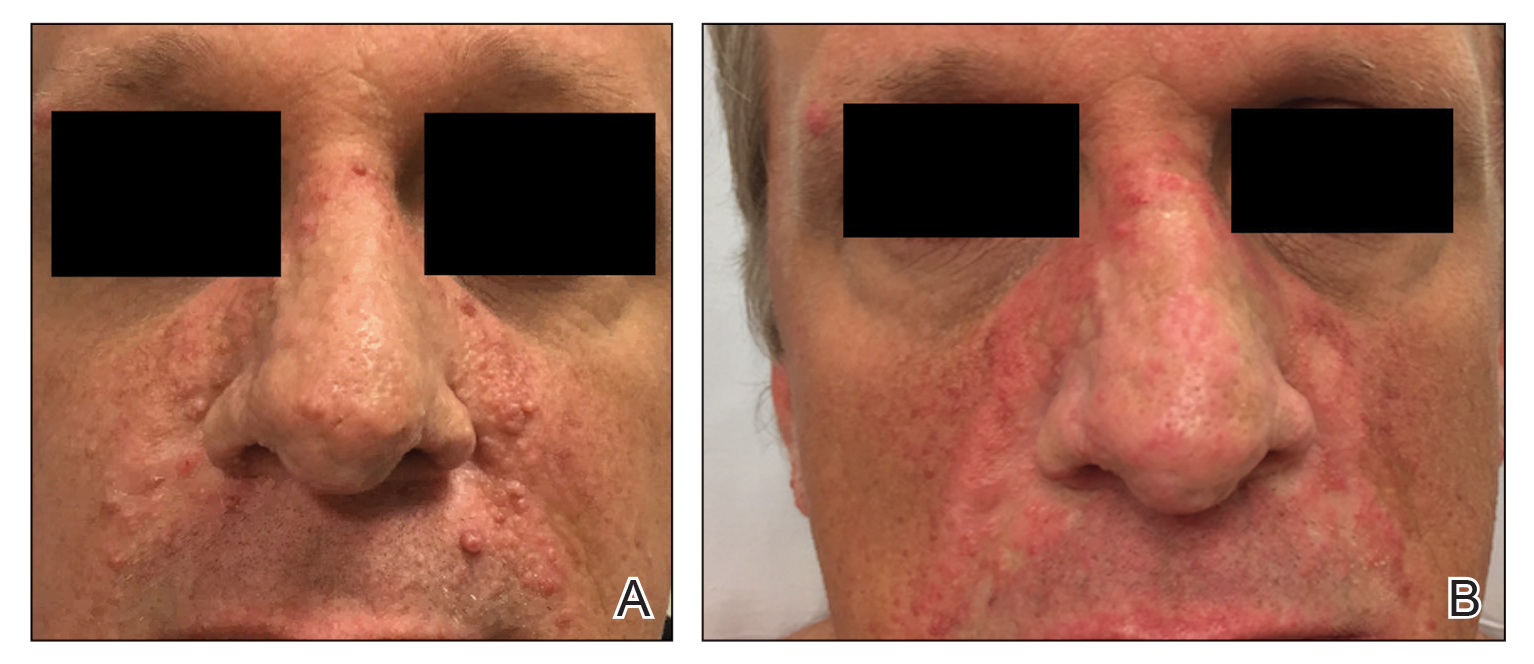

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

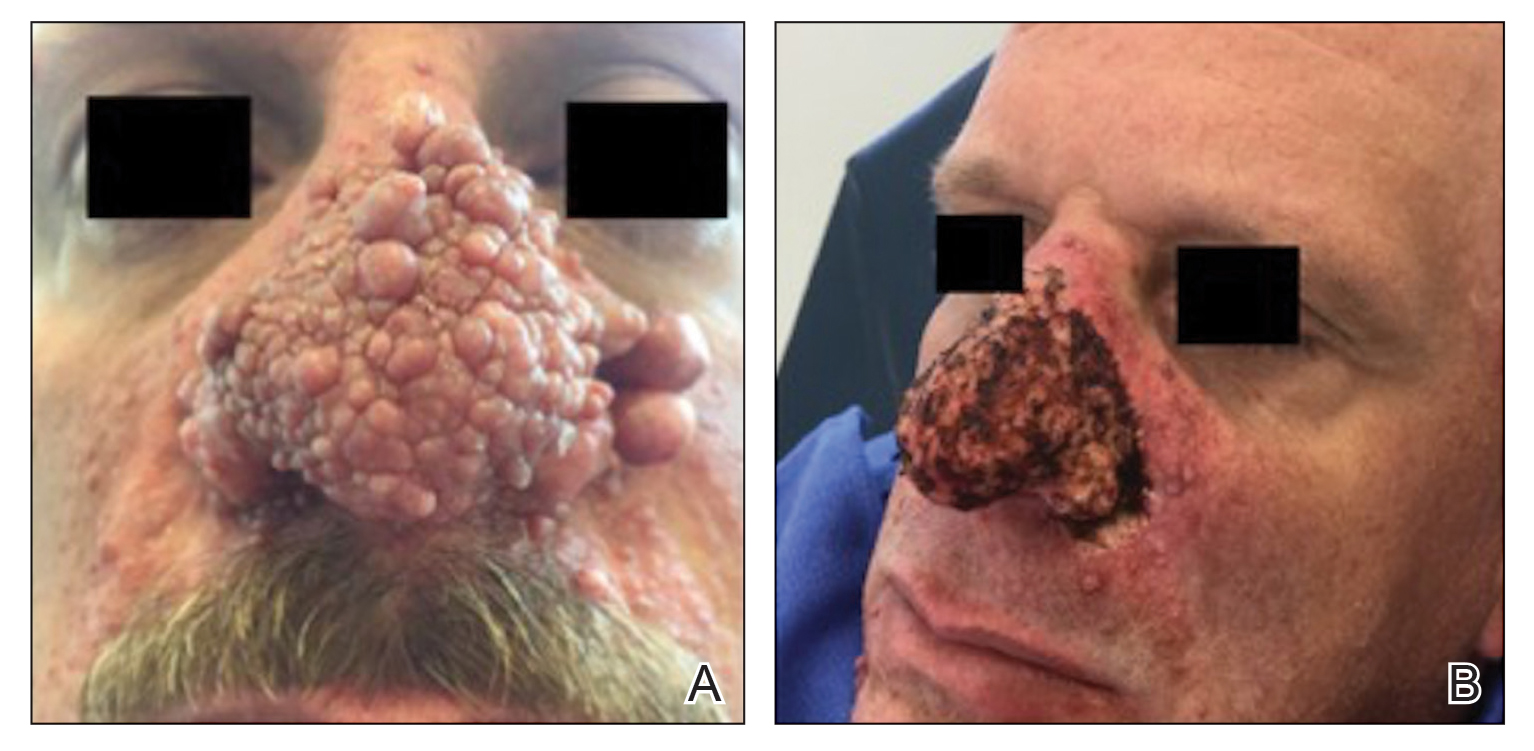

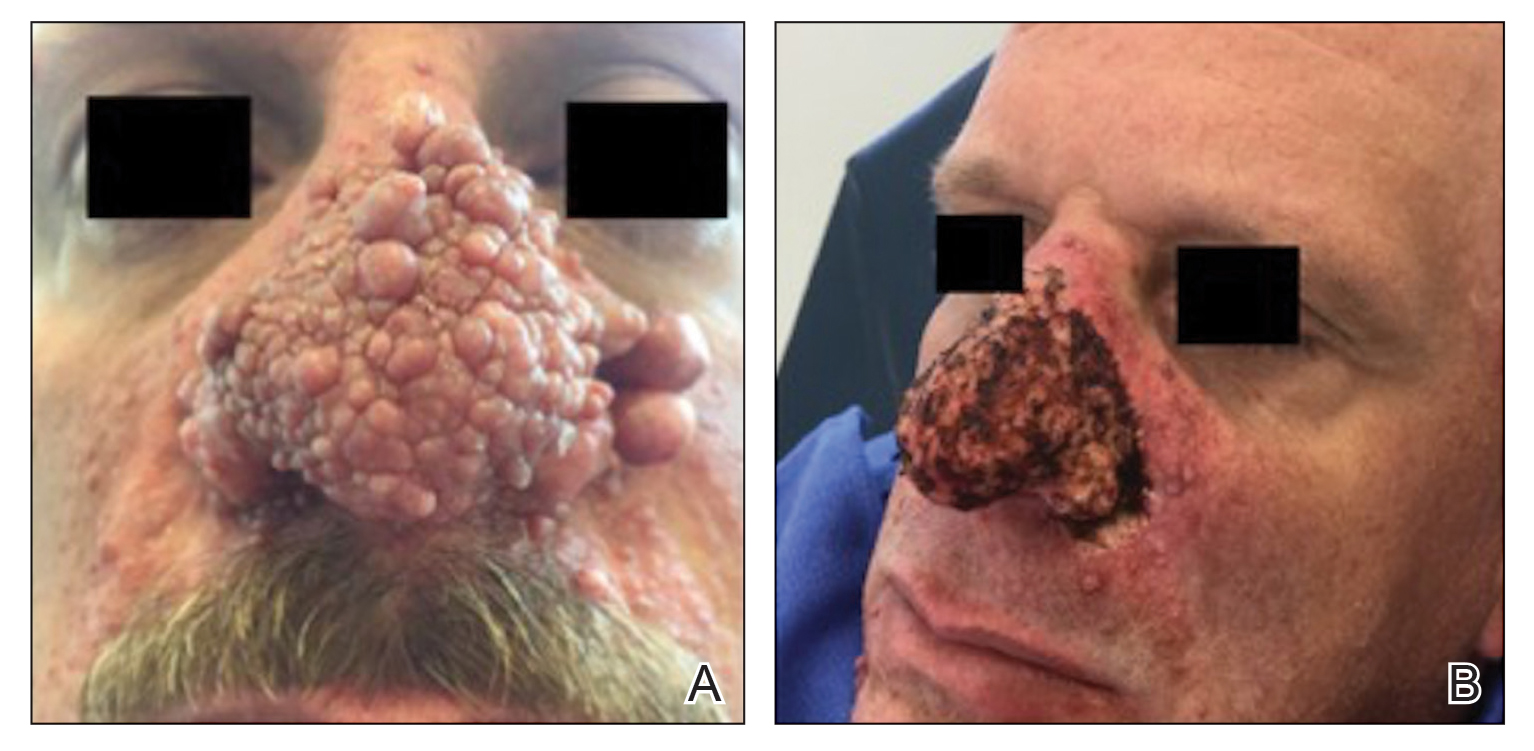

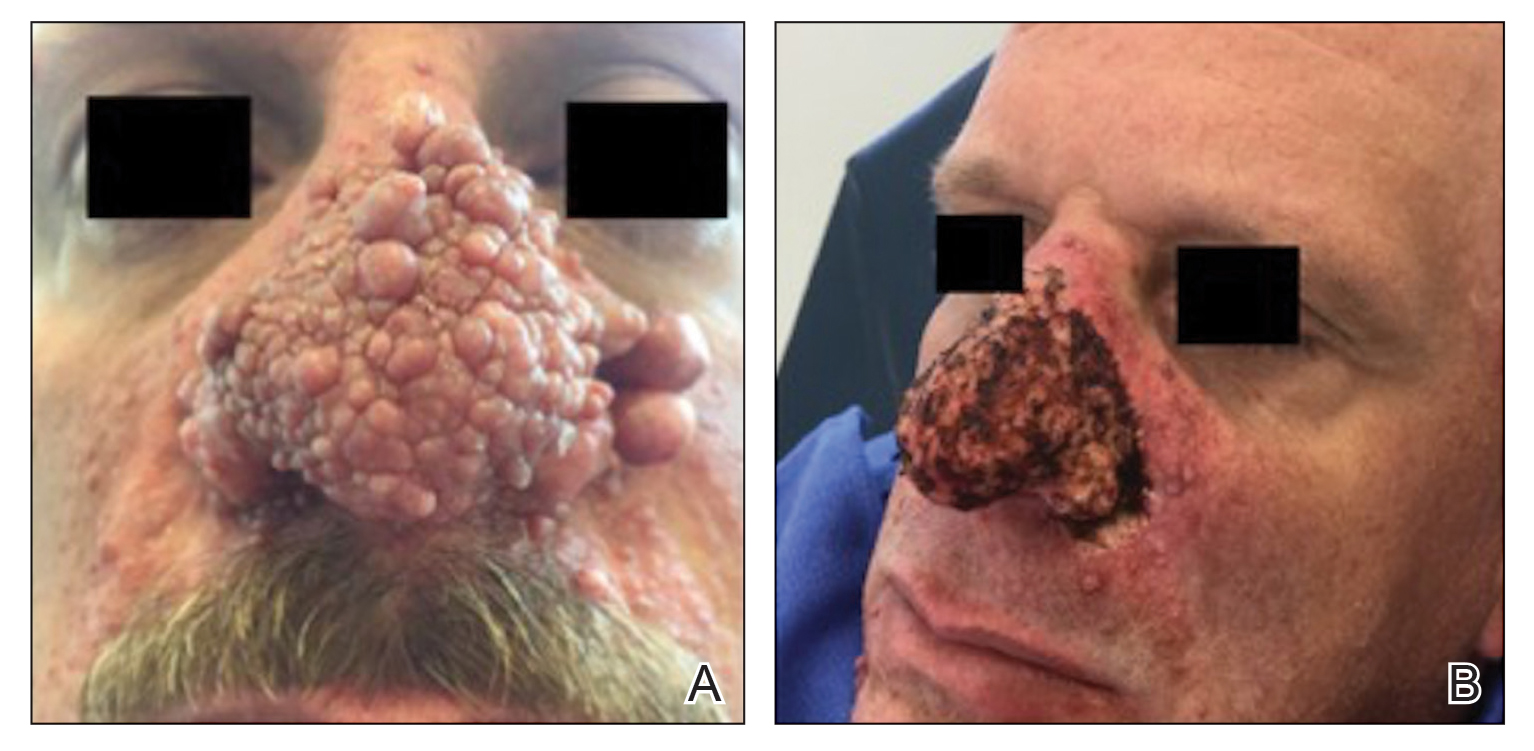

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.