User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Aged black garlic supplement may help lower BP

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

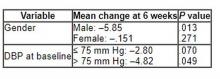

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRIENTS

New York NPs join half of states with full practice authority

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More medical schools build training in transgender care

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The best statins to lower non-HDL cholesterol in diabetes?

A network meta-analysis of 42 clinical trials concludes that rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin are the statins most effective at lowering non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) in people with diabetes and at risk for cardiovascular disease.

The analysis focused on the efficacy of statin treatment on reducing non-HDL-C, as opposed to reducing low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), which has traditionally been used as a surrogate to determine cardiovascular disease risk from hypercholesterolemia.

“The National Cholesterol Education Program in the United States recommends that LDL-C values should be used to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease related to lipoproteins,” lead author Alexander Hodkinson, MD, senior National Institute for Health Research fellow, University of Manchester, England, told this news organization.

“But we believe that non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol is more strongly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, because non-HDL-C combines all the bad types of cholesterol, which LDL-C misses, so it could be a better tool than LDL-C for assessing CVD risk and effects of treatment. We already knew which of the statins reduce LDL-C, but we wanted to know which ones reduced non-HDL-C; hence the reason for our study,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

The findings were published online in BMJ.

In April 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom updated guidelines for adults with diabetes to recommend that non-HDL-C should replace LDL-C as the primary target for reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease with lipid-lowering treatment.

Currently, NICE is alone in its recommendation. Other international guidelines do not have a non-HDL-C target and use LDL-C reduction instead. These include guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the National Lipid Association.

Non–HDL-C is simple to calculate and can easily be done by clinicians by subtracting HDL-C from the total cholesterol level, he added.

This analysis compared the effectiveness of different statins at different intensities in reducing levels of non-HDL-C in 42 randomized controlled trials that included 20,193 adults with diabetes.

Compared with placebo, rosuvastatin, given at moderate- and high-intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin at high-intensity doses, were the best at lowering levels of non-HDL-C over an average treatment period of 12 weeks.

High-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.31 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.39 to –1.21). Moderate-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.27 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.00 to –1.49).

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 2.26 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.99 to –1.51).

High-intensity atorvastatin led to a 2.20 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.69 to –1.70).

Atorvastatin and simvastatin at any intensity and pravastatin at low intensity were also effective in reducing levels of non-HDL-C, the researchers noted.

In 4,670 patients who were at great risk for a major cardiovascular event, atorvastatin at high intensity showed the largest reduction in levels of non-HDL-C (1.98 mmol/L; 95% credible interval, –4.16 to 0.26).

In addition, high-intensity simvastatin and rosuvastatin were the most effective in reducing LDL-C.

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 1.93 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.63 to –1.21), and high-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 1.76 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.37 to –1.15).

In four studies, significant reductions in nonfatal myocardial infarction were shown for atorvastatin at moderate intensity, compared with placebo (relative risk, 0.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.43-.76). No significant differences were seen for discontinuations, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death.

“We hope our findings will help guide clinicians on statin selection itself, and what types of doses they should be giving patients. These results support using NICE’s new policy guidelines on cholesterol monitoring, using this non-HDL-C measure, which contains all the bad types of cholesterol for patients with diabetes,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

“This study further emphasizes what we have known about the benefit of statin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

Dr. Deedwania and others have published data on patients with diabetes that showed that treatment with high-intensity atorvastatin was associated with significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events.

“Here they use non-HDL cholesterol as a target. The NICE guidelines are the only guidelines looking at non-HDL cholesterol; however, all guidelines suggest an LDL to be less than 70 in all people with diabetes, and for those with recent acute coronary syndromes, the latest evidence suggests the LDL should actually be less than 50,” said Dr. Deedwania, spokesperson for the AHA and ACC.

As far as which measure to use, he believes both are useful. “It’s six of one and half a dozen of the other, in my opinion. The societies have not recommended non-HDL cholesterol and it’s easier to stay with what is readily available for clinicians, and using LDL cholesterol is still okay. The results of this analysis are confirmatory, in that looking at non-HDL cholesterol gives results very similar to what these statins have shown for their effect on LDL cholesterol,” he said.

Non-HDL cholesterol a better marker?

For Robert Rosenson, MD, director of metabolism and lipids at Mount Sinai Health System and professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, non-HDL cholesterol is becoming an important marker of risk for several reasons.

“The focus on LDL cholesterol has been due to the causal relationship of LDL with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but in the last few decades, non-HDL has emerged because more people are overweight, have insulin resistance, and have diabetes,” Dr. Rosenson told this news organization. “In those situations, the LDL cholesterol underrepresents the risk of the LDL particles. With insulin resistance, the particles become more triglycerides and less cholesterol, so on a per-particle basis, you need to get more LDL particles to get to a certain LDL cholesterol concentration.”

Non-HDL cholesterol testing does not require fasting, another advantage of using it to monitor cholesterol, he added.

What is often forgotten is that moderate- to high-intensity statins have very good triglyceride-lowering effects, Dr. Rosenson said.

“This article highlights that, by using higher doses, you get more triglyceride-lowering. Hopefully, this will get practitioners to recognize that non-HDL cholesterol is a better predictor of risk in people with diabetes,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Hodkinson, Dr. Rosenson, and Dr. Deedwania report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A network meta-analysis of 42 clinical trials concludes that rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin are the statins most effective at lowering non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) in people with diabetes and at risk for cardiovascular disease.

The analysis focused on the efficacy of statin treatment on reducing non-HDL-C, as opposed to reducing low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), which has traditionally been used as a surrogate to determine cardiovascular disease risk from hypercholesterolemia.

“The National Cholesterol Education Program in the United States recommends that LDL-C values should be used to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease related to lipoproteins,” lead author Alexander Hodkinson, MD, senior National Institute for Health Research fellow, University of Manchester, England, told this news organization.

“But we believe that non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol is more strongly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, because non-HDL-C combines all the bad types of cholesterol, which LDL-C misses, so it could be a better tool than LDL-C for assessing CVD risk and effects of treatment. We already knew which of the statins reduce LDL-C, but we wanted to know which ones reduced non-HDL-C; hence the reason for our study,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

The findings were published online in BMJ.

In April 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom updated guidelines for adults with diabetes to recommend that non-HDL-C should replace LDL-C as the primary target for reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease with lipid-lowering treatment.

Currently, NICE is alone in its recommendation. Other international guidelines do not have a non-HDL-C target and use LDL-C reduction instead. These include guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the National Lipid Association.

Non–HDL-C is simple to calculate and can easily be done by clinicians by subtracting HDL-C from the total cholesterol level, he added.

This analysis compared the effectiveness of different statins at different intensities in reducing levels of non-HDL-C in 42 randomized controlled trials that included 20,193 adults with diabetes.

Compared with placebo, rosuvastatin, given at moderate- and high-intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin at high-intensity doses, were the best at lowering levels of non-HDL-C over an average treatment period of 12 weeks.

High-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.31 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.39 to –1.21). Moderate-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.27 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.00 to –1.49).

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 2.26 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.99 to –1.51).

High-intensity atorvastatin led to a 2.20 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.69 to –1.70).

Atorvastatin and simvastatin at any intensity and pravastatin at low intensity were also effective in reducing levels of non-HDL-C, the researchers noted.

In 4,670 patients who were at great risk for a major cardiovascular event, atorvastatin at high intensity showed the largest reduction in levels of non-HDL-C (1.98 mmol/L; 95% credible interval, –4.16 to 0.26).

In addition, high-intensity simvastatin and rosuvastatin were the most effective in reducing LDL-C.

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 1.93 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.63 to –1.21), and high-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 1.76 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.37 to –1.15).

In four studies, significant reductions in nonfatal myocardial infarction were shown for atorvastatin at moderate intensity, compared with placebo (relative risk, 0.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.43-.76). No significant differences were seen for discontinuations, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death.

“We hope our findings will help guide clinicians on statin selection itself, and what types of doses they should be giving patients. These results support using NICE’s new policy guidelines on cholesterol monitoring, using this non-HDL-C measure, which contains all the bad types of cholesterol for patients with diabetes,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

“This study further emphasizes what we have known about the benefit of statin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

Dr. Deedwania and others have published data on patients with diabetes that showed that treatment with high-intensity atorvastatin was associated with significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events.

“Here they use non-HDL cholesterol as a target. The NICE guidelines are the only guidelines looking at non-HDL cholesterol; however, all guidelines suggest an LDL to be less than 70 in all people with diabetes, and for those with recent acute coronary syndromes, the latest evidence suggests the LDL should actually be less than 50,” said Dr. Deedwania, spokesperson for the AHA and ACC.

As far as which measure to use, he believes both are useful. “It’s six of one and half a dozen of the other, in my opinion. The societies have not recommended non-HDL cholesterol and it’s easier to stay with what is readily available for clinicians, and using LDL cholesterol is still okay. The results of this analysis are confirmatory, in that looking at non-HDL cholesterol gives results very similar to what these statins have shown for their effect on LDL cholesterol,” he said.

Non-HDL cholesterol a better marker?

For Robert Rosenson, MD, director of metabolism and lipids at Mount Sinai Health System and professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, non-HDL cholesterol is becoming an important marker of risk for several reasons.

“The focus on LDL cholesterol has been due to the causal relationship of LDL with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but in the last few decades, non-HDL has emerged because more people are overweight, have insulin resistance, and have diabetes,” Dr. Rosenson told this news organization. “In those situations, the LDL cholesterol underrepresents the risk of the LDL particles. With insulin resistance, the particles become more triglycerides and less cholesterol, so on a per-particle basis, you need to get more LDL particles to get to a certain LDL cholesterol concentration.”

Non-HDL cholesterol testing does not require fasting, another advantage of using it to monitor cholesterol, he added.

What is often forgotten is that moderate- to high-intensity statins have very good triglyceride-lowering effects, Dr. Rosenson said.

“This article highlights that, by using higher doses, you get more triglyceride-lowering. Hopefully, this will get practitioners to recognize that non-HDL cholesterol is a better predictor of risk in people with diabetes,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Hodkinson, Dr. Rosenson, and Dr. Deedwania report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A network meta-analysis of 42 clinical trials concludes that rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin are the statins most effective at lowering non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) in people with diabetes and at risk for cardiovascular disease.

The analysis focused on the efficacy of statin treatment on reducing non-HDL-C, as opposed to reducing low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), which has traditionally been used as a surrogate to determine cardiovascular disease risk from hypercholesterolemia.

“The National Cholesterol Education Program in the United States recommends that LDL-C values should be used to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease related to lipoproteins,” lead author Alexander Hodkinson, MD, senior National Institute for Health Research fellow, University of Manchester, England, told this news organization.

“But we believe that non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol is more strongly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, because non-HDL-C combines all the bad types of cholesterol, which LDL-C misses, so it could be a better tool than LDL-C for assessing CVD risk and effects of treatment. We already knew which of the statins reduce LDL-C, but we wanted to know which ones reduced non-HDL-C; hence the reason for our study,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

The findings were published online in BMJ.

In April 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom updated guidelines for adults with diabetes to recommend that non-HDL-C should replace LDL-C as the primary target for reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease with lipid-lowering treatment.

Currently, NICE is alone in its recommendation. Other international guidelines do not have a non-HDL-C target and use LDL-C reduction instead. These include guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the National Lipid Association.

Non–HDL-C is simple to calculate and can easily be done by clinicians by subtracting HDL-C from the total cholesterol level, he added.

This analysis compared the effectiveness of different statins at different intensities in reducing levels of non-HDL-C in 42 randomized controlled trials that included 20,193 adults with diabetes.

Compared with placebo, rosuvastatin, given at moderate- and high-intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin at high-intensity doses, were the best at lowering levels of non-HDL-C over an average treatment period of 12 weeks.

High-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.31 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.39 to –1.21). Moderate-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 2.27 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –3.00 to –1.49).

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 2.26 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.99 to –1.51).

High-intensity atorvastatin led to a 2.20 mmol/L reduction in non-HDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.69 to –1.70).

Atorvastatin and simvastatin at any intensity and pravastatin at low intensity were also effective in reducing levels of non-HDL-C, the researchers noted.

In 4,670 patients who were at great risk for a major cardiovascular event, atorvastatin at high intensity showed the largest reduction in levels of non-HDL-C (1.98 mmol/L; 95% credible interval, –4.16 to 0.26).

In addition, high-intensity simvastatin and rosuvastatin were the most effective in reducing LDL-C.

High-intensity simvastatin led to a 1.93 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.63 to –1.21), and high-intensity rosuvastatin led to a 1.76 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (95% credible interval, –2.37 to –1.15).

In four studies, significant reductions in nonfatal myocardial infarction were shown for atorvastatin at moderate intensity, compared with placebo (relative risk, 0.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.43-.76). No significant differences were seen for discontinuations, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death.

“We hope our findings will help guide clinicians on statin selection itself, and what types of doses they should be giving patients. These results support using NICE’s new policy guidelines on cholesterol monitoring, using this non-HDL-C measure, which contains all the bad types of cholesterol for patients with diabetes,” Dr. Hodkinson said.

“This study further emphasizes what we have known about the benefit of statin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

Dr. Deedwania and others have published data on patients with diabetes that showed that treatment with high-intensity atorvastatin was associated with significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events.

“Here they use non-HDL cholesterol as a target. The NICE guidelines are the only guidelines looking at non-HDL cholesterol; however, all guidelines suggest an LDL to be less than 70 in all people with diabetes, and for those with recent acute coronary syndromes, the latest evidence suggests the LDL should actually be less than 50,” said Dr. Deedwania, spokesperson for the AHA and ACC.

As far as which measure to use, he believes both are useful. “It’s six of one and half a dozen of the other, in my opinion. The societies have not recommended non-HDL cholesterol and it’s easier to stay with what is readily available for clinicians, and using LDL cholesterol is still okay. The results of this analysis are confirmatory, in that looking at non-HDL cholesterol gives results very similar to what these statins have shown for their effect on LDL cholesterol,” he said.

Non-HDL cholesterol a better marker?

For Robert Rosenson, MD, director of metabolism and lipids at Mount Sinai Health System and professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, non-HDL cholesterol is becoming an important marker of risk for several reasons.

“The focus on LDL cholesterol has been due to the causal relationship of LDL with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but in the last few decades, non-HDL has emerged because more people are overweight, have insulin resistance, and have diabetes,” Dr. Rosenson told this news organization. “In those situations, the LDL cholesterol underrepresents the risk of the LDL particles. With insulin resistance, the particles become more triglycerides and less cholesterol, so on a per-particle basis, you need to get more LDL particles to get to a certain LDL cholesterol concentration.”

Non-HDL cholesterol testing does not require fasting, another advantage of using it to monitor cholesterol, he added.

What is often forgotten is that moderate- to high-intensity statins have very good triglyceride-lowering effects, Dr. Rosenson said.

“This article highlights that, by using higher doses, you get more triglyceride-lowering. Hopefully, this will get practitioners to recognize that non-HDL cholesterol is a better predictor of risk in people with diabetes,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Hodkinson, Dr. Rosenson, and Dr. Deedwania report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. life expectancy dropped by 2 years in 2020: Study

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.

The life expectancy drop from 2019 to 2020 hit Black and Hispanic people hardest, according to the study. But the drop from 2020 to 2021 affected White people the most, with average life expectancy among them going down about a third of a year.

Researchers looked at death data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Human Mortality Database, and overseas statistical agencies. Life expectancy for 2021 was estimated “using a previously validated modeling method,” the study said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.

The life expectancy drop from 2019 to 2020 hit Black and Hispanic people hardest, according to the study. But the drop from 2020 to 2021 affected White people the most, with average life expectancy among them going down about a third of a year.

Researchers looked at death data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Human Mortality Database, and overseas statistical agencies. Life expectancy for 2021 was estimated “using a previously validated modeling method,” the study said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.