User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Mentally ill and behind bars

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

Memory problems

Post-surgical cognitive decline hits women hardest

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Offer these interventions to help prevent suicide by firearm

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

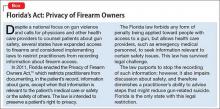

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

When ‘eating healthy’ becomes disordered, you can return patients to genuine health

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

Precipitously and certainly psychotic—but what’s the cause?

CASE Sudden personality change

Ms. L, age 38, is brought to the university hospital’s emergency department (ED) under police escort after she awoke in the middle of the night screaming, “I found it out! I’m a lie! Life is a lie!” and began threatening suicide. This prompted her spouse to call emergency services because of concerns about her safety.

Over the preceding 9 days—and, most precipitously, over the last 24 hours—Ms. L has experienced a dramatic “change in her personality,” according to her spouse. In the ED, she is oriented to person, place, and time. Her vital signs are within normal limits, other than a mild tachycardia. Complete blood count and complete metabolic profile are unremarkable and a urine drug screen is positive only for benzodiazepines (she recently was prescribed alprazolam). Ms. L smiles inappropriately at the ED physicians and confides that she is hearing music by The Lumineers, despite silence in her room.

The psychiatry service is consulted after she is seen making threats of harm to her family members.

EVALUATION Confusion

Over past several weeks, Ms. L has experienced rapid onset of neurovegetative symptoms, with poor oral intake, increased somnolence, neglect of hygiene, excessive time spent in bed, and weight loss of 15 to 20 lb, according to her spouse. She also has been complaining of foggy mentation, weakening handgrip, and tinnitus. She has no previous psychiatric history.

She recently established care with an outpatient neurologist and infectious disease specialist to address these symptoms. Outpatient EEG and sexually transmitted infection (STI) tests were scheduled but not yet obtained. Ms. L’s spouse observes that her drastic “personality change” over the preceding 24 hours coincided with her feeling upset and offended by a physician’s recommendation to obtain STI tests (it is unclear why the physician recommended these tests).

Ms. L had presented to another local ED 4 times over several weeks for various complaints, and had been prescribed alprazolam, 0.5 mg, 3 times a day as needed, and buspirone, 15 mg/d, for anxiety. She also had received a short course of doxycycline, 200 mg/d, which she did not finish, for treatment of presumed Lyme disease. According to her spouse, Ms. L had completed a course of doxycycline for Lyme disease 1 year earlier, but the medical records are not available for review.

During the interview, Ms. L is fairly well groomed but appears confused; she asks her spouse if she is “real” and states that she feels “crazy.” She seems uncomfortable and is guarded, with a minimally reactive, anxious affect. She has general psychomotor slowing and her speech is soft and monotonous, with prominent latency. She reports passive suicidal ideations as well as active auditory hallucinations of a musical quality.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score is 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment, and she is unable to complete attention, executive function, 3-stage command, and delayed word recall tasks. She reports fatigue, diarrhea, and decreased appetite. Her physical examination is notable for an overweight white woman without focal neurologic deficits. Her family psychiatric history reveals bipolar disorder in 2 distant relatives.

In the ED, Ms. L is given 3 provisional diagnoses:

- adjustment disorder, because of her reaction to the proposed STI testing

- psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, because of her obvious psychosis of unknown cause

- rule out delirium due to a general medical condition, because of her sudden onset of attention, perception, and memory difficulties.

As Ms. L sits in her room, her abnormal behaviors become more apparent. She starts to endorse active suicidal ideations and becomes aggressive, trying to choke her spouse, shouting, jumping on her bed, and attempting to strike herself. For her safety, she is physically restrained and given IM haloperidol, 10 mg, and IM lorazepam, 2 mg.

What would you do next to treat Ms. L?

a) Admit her to the psychiatric unit for monitoring and treatment of psychosis and consider additional antipsychotics for agitation

b) Perform a bedside lumbar puncture to assess for findings suggestive of a CNS infection or anomaly

c) Sedate her with IM ketamine, intubate her, and admit her to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further medical workup

d) Begin IV antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone for early-disseminated Lyme disease with CNS involvement

The authors’ observations

Clearly, Ms. L was psychotic. However, psychosis is a nonspecific term used to describe a heterogeneous group of phenomena in which one experiences an impaired sense of reality. Although commonly caused by psychiatric disorders, psychosis can arise from a variety of causes.1 Ms. L’s initial physical examination and laboratory studies were within the normal range, but her mental status exam and MMSE were abnormal. At this point, selecting the appropriate setting for further observation, workup, and treatment became important.

TREATMENT The right setting

Given the abrupt onset of Ms. L’s symptoms, the treatment team is concerned about active neurologic or infectious disease. However, no acute laboratory or physical examination findings support this hypothesis, and the ED physicians conclude that no further emergent workup is indicated. Because Ms. L is threatening harm to herself and others, she cannot be safely discharged. The treatment team decides the safest option is to admit Ms. L to the inpatient psychiatric unit for observation, further non-emergent workup, and consultation with the neurology service.

At admission. Ms. L is cooperative and calm, lying in bed comfortably. She obeys simple commands; a brief neurologic examination is remarkable for a sedated female without focal motor or sensory deficits. Although her answers to questions are brief, they are appropriate. She sleeps without incident for approximately 10 hours.

The next morning. Ms. L does not awaken to verbal or gentle physical stimuli. Upon sternal rub, she awakens and forcefully squeezes the examiner’s arm, after which she closes her eyes and does not answer further questions (but does resist passive eye opening). After several minutes, she begins exhibiting verbigeration, shouting repeated phrases such as “The birds are in my ears” and “No, I am not okay.”

An emergent EEG is ordered because the team is concerned about nonconvulsive status epilepticus and the neurology service is consulted about the need for an urgent lumbar puncture. Without any obvious abnormal physical examination findings, however, the neurology team’s initial assessment attributes Ms. L’s presentation to a primary psychiatric illness and does not recommend a lumbar puncture or EEG.

That day and night, Ms. L has several episodes of agitation with a disorganized thought process and perseverative speech. She appears distraught and exhibits menacing behaviors. She is poorly redirectable and physically hostile toward staff, requiring several emergent doses of IM haloperidol and IM lorazepam, to which she responds minimally. Ms. L is placed on constant observation, requiring frequent redirection from the rooms of other patients and intermittent seclusion because of her violent, destructive behavior.

The next day. Ms. L remains grossly agitated and psychotic. Although an EEG is ordered, it is not performed because the technicians are concerned about their safety. With her unclear history of Lyme disease and concern for an infectious encephalopathy, Ms. L’s history and symptoms are discussed with the infectious disease service. Given her abrupt onset of symptoms, including auditory hallucinations, they express concern for herpes simplex encephalitis and recommend emergent treatment with IV acyclovir and ceftriaxone.

This recommendation, however, causes a practical conundrum. Because of state laws and differences in staff training, the treatment team believes that the inpatient psychiatric unit is not the appropriate setting to administer these IV treatments. At the same time, hospital security, nursing staff, and the receiving medical team are concerned about transporting Ms. L to the general medical floor.

In the ICU. After discussion, the teams decide that the safest and least traumatic option is to transport Ms. L to the ICU after she is sedated and intubated. In the ICU, she undergoes empirical treatment for herpes simplex encephalitis and further medical workup.

An EEG reveals findings suggestive of severe encephalopathy. A lumbar puncture shows lymphocytic pleocytosis with an opening pressure of 28 cm H2O and normal protein and glucose levels. Her serum C-reactive protein is slightly elevated at 1.4 mg/dL. She also is found to have an elevated herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 IgG antibody.

Subsequent hospital stay. Ms. L has 2 episodes of seizure-like activity, for which she is treated with levetiracetam, 2,000 mg/d, increased to 3,000 mg/d. She is sedated for several days to allow broad treatment with antiviral and antibiotic medications. Although she experiences intermittent fevers and tachycardia, cultures of blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) show no growth. Similarly, a test of serum HSV IgM antibodies is negative.

CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis reveals no findings suggestive of malignancy but does show a solid-appearing 6-mm nodule in her right lung. Magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck shows no evidence of abnormalities other than atrophy of the superior cerebellar vermis and a subtle focus of T2/FLAIR signal abnormality in the medial portion of the left occipital lobe.

The following weeks. Ms. L’s cognitive status improves markedly. Extensive studies—including serum ammonia, thyroid-stimulating hormone, Lyme disease antibody, vitamin B12, folate, beta-hCG, HIV, hepatitis B and C, Varicella zoster, syphilis, Lyme disease serology, CSF Eastern equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Babesia microti, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, John Cunningham virus, typhus fever, cryptococcal antigen, rabies, 2 serum tests for anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibodies, and serum ceruloplasmin—are normal.

At discharge, Ms. L’s clinical presentation is thought to be most consistent with viral encephalitis, because of her CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis, fever, and improvement with supportive care. Because she improves, the team does not find it necessary to wait for results of pending studies, including a paraneoplastic autoantibody panel and a CSF anti-NMDA receptor antibody, before discharging her.

Readmission. Although the results of the paraneoplastic autoantibody panel are unremarkable, several weeks after discharge Ms. L’s CSF anti-NMDA receptor antibodies return positive, despite 2 earlier negative serum studies. She is readmitted to the neurology service for treatment with immunomodulators.

A positron-emission tomography scan is negative for malignancy. She is treated on an ongoing basis with immunomodulators; cognition improves such that she is able to start working again with good overall functioning. Despite this improvement, she experiences residual sequelae, including noise sensitivity, amnesia of the events surrounding her hospitalization, mild short-term memory deficits, and persistent affective blunting.

The authors’ observations

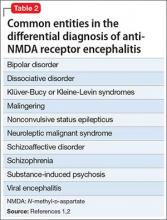

Psychosis is not exclusive to psychiatric syndromes and frequently is a symptom of an underlying neurologic, immunologic, metabolic, infectious, or oncologic abnormality.1 Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is an autoimmune disease in which antibodies attack NMDA-type glutamate receptors at central neuronal synapses and can produce psychosis, as seen with Ms. L2 (Table 12,3). The etiology of the disease is not fully understood. Determining the appropriate setting to perform a complete medical workup in a severely agitated patient after an initial negative medical workup can be challenging.

What’s the most appropriate treatment setting?

This case illustrates the importance, with any new-onset psychosis, of weighing heavily a carefully obtained psychiatric history, even in the absence of focal physical examination and initial laboratory abnormalities. It also highlights the challenge of determining the most appropriate initial setting for performing the important task of a complete medical workup for first-episode psychosis.

Ms. L initially was treated in the inpatient psychiatric unit because of safety concerns and practical limitations, but was later found to have a disease that could not be managed in that setting. She proved to be too agitated to obtain a full medical workup on the inpatient psychiatric or general medical floors and required transfer to the ICU. Despite her normal basic laboratory tests, her EEG and CSF studies did demonstrate abnormalities, suggesting these can be useful to the basic workup for psychosis of unknown cause (Table 21,2).

This case also demonstrates that negative serum anti-NMDA receptor antibody tests do not rule out the disease; one study found that only 85% of patients with CSF anti-NMDA receptor antibodies also had detectable antibodies in their serum and that detectability changed during the course of the disease.4 This supports the utility of a lumbar puncture as part of a basic initial workup for some cases of new-onset psychosis. Because clinical outcomes often correlate with early treatment, as with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, a timely diagnostic workup of psychosis often can be important.3,5 The ICU can be considered an appropriate setting for working up some patients who develop new, rapid-onset psychosis and severe agitation, even in the absence of initial laboratory or physical examination findings.

Ms. L’s case also illustrates the importance of completing a thorough medical workup for patients with new-onset psychosis before transferring them to an independent psychiatric hospital. Initially, the university’s psychiatric unit was at capacity and a bed was sought at outside psychiatric hospitals while Ms. L waited in the ED. Had Ms. L not been admitted to a large academic medical center, she may not have had access to the multidisciplinary collaboration that proved necessary for the appropriate diagnosis and treatment of her anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis (Table 35,6).

What prodromal symptoms occur as long as 2 weeks as an initial presentation in many patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis?

a) Flu-like symptoms of lethargy, headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, and upper respiratory symptoms

b) Delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behaviors and thoughts, behavioral outbursts, hypersexuality, mood lability, personality change, paranoia, echolalia, mutism, anxiety, agitation, aggression, hyperactivity, sleep dysfunction, and blunted affect

c) Dyskinesias, autonomic instability, central hypoventilation, and seizures

The authors’ observations

Lab results, vital signs, and physical examination should not supplant a careful history when determining an appropriate clinical course of action. As experts in the cognitive sciences, psychiatrists may be the most qualified in determining whether a patient with new-onset psychosis should undergo further medical testing before a condition is deemed to be solely of a psychiatric cause. As a neurologic disease of immunologic origin with psychiatric manifestations, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a complex condition requiring collaboration among several specialists for appropriate management.

1. Freudenreich O. Differential diagnosis of psychotic symptoms: medical “mimics.” Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/forensic-psychiatry/differential-diagnosis-psychotic-symptoms-medical-%E2%80%9Cmimics%E2%80%9D. Published December 3, 2012. Accessed March 31, 2016.

2. Kayser MS, Dalmau J. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in psychiatry. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2011;7(3):189-193.

3. Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(1):63-74.

4. Gresa-Arribas N, Titulaer MJ, Torrents A, et al. Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):167-177.

5. Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1091-1098.

6. Dalmau J, Tüzün E, Wu HY, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25-36.

CASE Sudden personality change

Ms. L, age 38, is brought to the university hospital’s emergency department (ED) under police escort after she awoke in the middle of the night screaming, “I found it out! I’m a lie! Life is a lie!” and began threatening suicide. This prompted her spouse to call emergency services because of concerns about her safety.

Over the preceding 9 days—and, most precipitously, over the last 24 hours—Ms. L has experienced a dramatic “change in her personality,” according to her spouse. In the ED, she is oriented to person, place, and time. Her vital signs are within normal limits, other than a mild tachycardia. Complete blood count and complete metabolic profile are unremarkable and a urine drug screen is positive only for benzodiazepines (she recently was prescribed alprazolam). Ms. L smiles inappropriately at the ED physicians and confides that she is hearing music by The Lumineers, despite silence in her room.

The psychiatry service is consulted after she is seen making threats of harm to her family members.

EVALUATION Confusion

Over past several weeks, Ms. L has experienced rapid onset of neurovegetative symptoms, with poor oral intake, increased somnolence, neglect of hygiene, excessive time spent in bed, and weight loss of 15 to 20 lb, according to her spouse. She also has been complaining of foggy mentation, weakening handgrip, and tinnitus. She has no previous psychiatric history.