User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Is your patient’s poor recall more than just a ‘senior moment’?

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Memory and other cognitive complaints are common among the general population and become more prevalent with age.1 People who have significant emotional investment in their cognitive competence, mood disturbance, somatic symptoms, and anxiety or related disorders are likely to worry more about their cognitive functioning as they age.

Common complaints

Age-related complaints, typically beginning by age 50, often include problems retaining or retrieving names, difficulty recalling details of conversations and written materials, and hazy recollection of remote events and the time frame of recent life events. Common complaints involve difficulties with mental calculations, multi-tasking (including vulnerability to distraction), and problems keeping track of and organizing information. The most common complaint is difficulty with remembering the reason for entering a room.

More concerning are complaints involving recurrent lapses in judgment or forgetfulness with significant implications for everyday living (eg, physical safety, job performance, travel, and finances), especially when validated by friends or family members and coupled with decline in at least 1 activity of daily living, and poor insight.

Helping your forgetful patient

Office evaluation with brief cognitive screening instruments—namely, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the recent revision of the Mini-Mental State Examination—might help clarify the clinical presentation. Proceed with caution: Screening tests tap a limited number of neurocognitive functions and can generate a false-negative result among brighter and better educated patients and a false-positive result among the less intelligent and less educated.2 Applying age- and education-corrected norms can reduce misclassification but does not eliminate it.

Screening measures can facilitate decision-making regarding the need for more comprehensive psychometric assessment. Such evaluations sample a broader range of neurobehavioral domains, in greater depth, and provide a more nuanced picture of a patient’s neurocognition.

Findings on a battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that might evoke concern include problems with incidental, anterograde, and recent memory that are not satisfactorily explained by: age and education or vocational training; estimated premorbid intelligence; residual neurodevelopmental disorders (attention, learning, and autistic-spectrum disorders); situational, sociocultural, and psychiatric factors; and motivational influences—notably, malingering.

Some difficulties with memory are highly associated with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia:

• anterograde memory (involving a reduced rate of verbal and nonverbal learning over repeated trials)

• poor retention

• accelerated forgetting of newly learned information

• failure to benefit from recognition and other mnemonic cues

• so-called source error confusion—a misattribution that involves difficulty differentiating target information from competing information, as reflected in confabulation errors and an elevated rate of intrusion errors.

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

1. Weiner MF, Garrett R, Bret ME. Neuropsychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In: Weiner MF, Lipton AM, eds. Clinical manual of Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2012: 3-46.

2. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary: third edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Discharging your patients who display contingency-based suicidality: 6 steps

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discharging patients from a hospital or emergency department despite his (her) ongoing suicidal ideation is a clinical dilemma. Typically, these patients do not respond to hospital care and do not follow up after discharge. They often have a poorly treated illness and many unmet psychosocial and interpersonal needs.1 These patients may communicate their suicidality as conditional, aimed at satisfying unmet needs; secondary gain; dependency needs; or remaining in the sick role. Faced with impending discharge, such a patient might increase the intensity of his suicidal statements or engage in behaviors that subvert discharge. Some go as far as to engage in behaviors with apparent suicidal intent soon after discharge.

A complicated decision

Such patients often are at a chronically elevated risk for suicide because of mood disorders, personality pathology, substance use disorder, or a history of serious suicide attempt.2 Do not dismiss a patient’s suicidal statements; he is ill and may end his own life.

Managing these situations can put you under a variety of pressures: your own negative emotional and psychological reactions to the patient; pressure from staff to avoid admission or expedite discharge of the patient; and administrative pressure to efficiently manage resources.3 You’re faced with a difficult decision: Discharge a patient who might self-harm or commit suicide, or continue care that may be counterproductive.

We propose 6 steps that have helped us promote good clinical care while documenting the necessary information to manage risk in these complex situations.

1. Define and document the clinical situation. Summarize the clinical dilemma.

2. Assess and document current suicide risk.4 Conduct a formal suicide risk assessment; if necessary, reassess throughout care. Focus on dynamic risk factors; protective risk factors (static and dynamic); acute stressors (or lack thereof) that would increase their risk of suicide above their chronically elevated baseline; and access to lethal means—firearms, stockpiled medication, etc.

3. Document modified dynamic or protective factors. Review the dynamic risk and protective factors you have identified and how they have been modified by treatment to date. If dynamic factors have not been modified, indicate why and document the recommended plan to address these matters. You might not be able to provide relief, but you should be able to outline a plan for eventual relief.

4. Document the reasons continued care in the acute setting is not indicated. Reasons might include: the patient isn’t participating in recommended care or treatment; the patient isn’t improving, or is becoming worse, in the care environment; continued care is preventing or interfering with access to more effective care options; is counterproductive to the patient’s stated goals; or compromising the safety benefit of the structured care environment because the patient is not collaborating with his care team.

5. Document your discussion of discharge with the patient. Highlight attempts to engage the patient in adaptive problem solving. Work out a crisis or suicide safety plan and give the patient a copy and keep a copy in his (her) chart.

If the patient refuses to engage in safety planning, document it in the chart. Note the absence of any conditions that might impair the patient’s volitional capacity to not end their life—intoxication, delirium, acute psychosis, etc. Explicitly frame the patient’s responsibility for his life. Discuss and document a follow-up plan and make direct contact with providers and social supports, documenting whether contacting these providers was successful.

6. Consult with a colleague. An informal non-visit consultation with a colleague demonstrates your recognition of the complexity of the situation and your due diligence in arriving at a discharge decision. Consultation often will result in useful additional strategies for managing or engaging the patient. A colleague’s agreement helps demonstrate that “average practitioner” and “prudent practitioner” standards of care have been met with respect to clinical decision-making.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

1. Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(8):871-873.

2. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):527-543, viii-ix.

3. Gutheil TG, Schetky D. A date with death: management of time-based and contingent suicidal intent. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1502-1507.

4. Haney EM, O’Neil ME, Carson S, et al. Suicide risk factors and risk assessment tools: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

Medication for alcohol use disorder: Which agents work best?

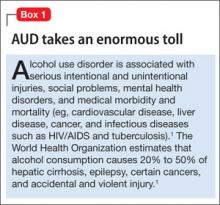

Historically, alcohol use disorder (AUD; classified as alcohol abuse or dependence in DSM-IV-TR) has been treated with psychosocial therapies, but many patients treated this way relapse into heavy drinking patterns and are unable to sustain sobriety (Box 11). Although vital for treating AUD, psychosocial methods have, to date, a modest success rate. Research has demonstrated that combining pharmacotherapy with psychosocial programs is effective for treating AUD.2

Patients and clinicians might associate AUD medications with so-called aversion therapy because, for many years, the only treatment was disulfiram, which causes unpleasant physical effects when consumed with alcohol. However, newer medications help patients maintain abstinence by targeting brain neurotransmitters relevant to addiction neurocircuitry, such as dopamine, serotonin, ϒ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, and opioid.3 These medications may help patients with AUD achieve sobriety, avoid relapse, decrease heavy drinking days, and delay time to recurrent drinking.

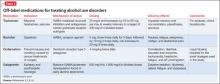

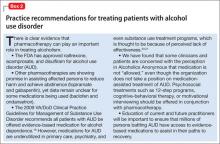

In this article, we review FDA-approved medications (Table 1)4-6 and off-label agents (Table 2)3,7-18 and provide recommendations for treating patients with AUD (Box 2).19-21

FDA-approved treatments

Naltrexone is an opiate antagonist that blocks the mu receptor and is believed to interrupt the dopamine reward pathway in the brain for alcohol. A meta-analysis of 2,861 patients in 24 combined randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated naltrexone to be an effective short-term (12 weeks) treatment for alcoholism, significantly decreasing relapses.22 The large multisite COMBINE study (N = 1,383) showed that naltrexone, 100 mg/d, and medical treatment without behavioral treatment over 16 weeks was more effective than placebo in increasing percentage of days abstinent (80.6% vs 75.1%, respectively) and reducing the percentage of patients experiencing heavy drinking days (66.2% vs 73.1%, respectively).2 Patients who have a family history of AUD or strong cravings, or both, may benefit most from naltrexone.3,7,23 Despite evidence of the effectiveness of naltrexone for AUD, not all studies have yielded positive results.24

Common side effects of naltrexone, if present, appear early in treatment and include GI upset (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), headache, and fatigue.2,3,22,23 Hepatotoxicity has been reported with dosages of 100 to 300 mg/d, but lab values typically normalize when naltrexone is discontinued.2,3,23 Monitor markers of liver function including ϒ-glutamyltransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and bilirubin before and during naltrexone treatment (we check patients 1 to 3 months after starting treatment and yearly thereafter). Obtain a negative urine drug screen for opioids before administering naltrexone, because if opioids were consumed recently naltrexone could precipitate withdrawal. Because of the unknown teratogenicity of naltrexone, women of childbearing age should undergo pregnancy testing before and periodically during naltrexone therapy.

Naltrexone also is available in a once-monthly, 380-mg injectable formulation. Studies show that, similar to its oral counterpart, injectable naltrexone effectively reduces heavy drinking days and number of drinks a day compared with placebo.25,26 Advantages of injectable naltrexone are its extended steady release of medication and its efficacy for patients who do not adhere to oral dosing.7,27 Side effects are similar to oral naltrexone, except for injection site reactions and pain.

Contraindications to naltrexone include current opioid use because its antagonistic effects on opioid receptors render opioid analgesia ineffective. Patients who have used opioids within 7 to 10 days or who may be surreptitiously using opioids should not take naltrexone because it may cause opioid withdrawal. Some patients may try to override the opioid receptor blockade of naltrexone with higher opioid doses, which could result in overdose.

Naltrexone is approved for treating opioid use disorder and may be useful for persons with comorbid opioid use disorder and AUD, if the patient has been adequately detoxified from opioids and intends to abstain from these drugs. Patients who have extensive liver damage secondary to acute hepatitis or uncompensated cirrhosis would not be good candidates for naltrexone because of a risk of hepatotoxicity.2,3,22

Because of ease of dosing, we recommend naltrexone as a first-line treatment for AUD, unless the patient requires opioids or has severe liver disease. We recommend increasing naltrexone from 50 mg to 100 mg before switching to acamprosate, based on European studies.

Acamprosate is a glutamate antagonist that is thought to modulate overactive glutamatergic brain activity that occurs after stopping chronic heavy alcohol use. In a meta-analysis of 17 studies (N = 4,087), continuous abstinence rates at 6 months were significantly higher in acamprosate-treated patients (36.1%) than in patients receiving placebo (23.4%).28 In a review of European studies, acamprosate benefited patients who have increased anxiety, physiological dependence, negative family history of AUD, and late age of onset (age >25) of alcohol dependence.7 However, in the COMBINE trial acamprosate was no more effective than placebo.2

We consider acamprosate an effective option for patients who do not respond to naltrexone or have a contraindication. Dosages of 333 mg to 666 mg, 3 times a day, are recommended, although dosages up to 3 g/d have been studied; titration is not required.2,7,28 We recommend advising patients to continue treatment even if they relapse, because these medications may mitigate relapse severity. Adherence to multiple daily doses can be problematic for some patients, but pairing medications with meals or bedtime may improve adherence.

Diarrhea is the most common side effect of acamprosate; nervousness, fatigue, insomnia, and depression have been reported with high dosages.2,3,7,28 Acamprosate is excreted through the kidney and is safe for patients with liver disorders such as acute hepatitis or cirrhosis. The drug is contraindicated in patients with acute or chronic renal failure with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min; those with less severe renal insufficiency might need a lower dosage. Obtain baseline renal function before starting acamprosate; women of childbearing age should undergo a pregnancy test.

Disulfiram inhibits alcohol metabolism, resulting in acetaldehyde accumulation, which causes unpleasant physical effects such as nausea, vomiting, and hypotension. This creates a negative rather than a positive experience with drinking. A US Veterans Administration Cooperative Study randomized 605 participants to riboflavin, disulfiram, 1 mg/d (an inactive dose), or disulfiram, 250 mg/d (standard dose). There was no difference in percentage of patients remaining abstinent or time to first drink.8 Participants receiving disulfiram, 250 mg/d, had fewer drinking days after relapse compared with the other groups.8

Adverse physical effects produced when disulfiram and alcohol interact include tremor, diaphoresis, unstable blood pressure, and severe diarrhea and vomiting. Disulfiram can cause medically serious reactions in a small percentage of patients, especially those with significant medical comorbidity or advanced age. Patients with severe hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, a history of stroke, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, or renal or hepatic insufficiency should not use disulfiram.3 Patients taking disulfiram should avoid casual exposures to food, aftershave, mouthwash, and hand sanitizer that might contain alcohol. Disulfiram has no significant effect on alcohol craving. Social support to help oversee dosing may enhance adherence.7

Off-label medications

Topiramate is FDA-approved to treat migraine headaches and some seizure disorders. Topiramate facilitates GABA-mediated neuronal inhibition and antagonizes certain glutamate receptor subtypes. In an RCT (N = 150), topiramate, up to 300 mg/d, was more effective than placebo at reducing heavy drinking days and number of drinks per day, increasing days abstinent, and alleviating cravings.9 In a 12-week, double-blind RCT (N = 150), topiramate increased “safe drinking”—defined as ≤1 standard drink per day for women and ≤2 per day for men—vs placebo.10 Dosages were 75 mg to 300 mg/d in twice daily divided doses. Dosing starts at 25 mg/d and increases by 25 to 50 mg a day at weekly intervals. We recommend reserving topiramate for persons who do not respond to or cannot tolerate naltrexone and acamprosate because of the slow titration needed to prevent side effects. Although not studied, it may seem that topiramate’s antiepileptic actions could prevent seizures during alcohol withdrawal, but the protracted titration would limit its utility.

Side effects of topiramate include impaired memory and concentration, paresthesia, and anorexia and are more likely to present during rapid titration or with a high dosage.7,8 Rare reports of spontaneous myopia, angle-closure glaucoma, increased intraocular pressure, ocular pain, and blurry vision have been reported, but these complications often resolve with discontinuation of topiramate.7,8

Topiramate primarily is excreted through the kidney, and its action in the renal tubules can lead to metabolic acidosis or nephrolithiasis.8 Relative contraindications include acute or chronic kidney disease, including kidney stones. Consider slower titration and a 50% reduction in dosing if creatinine clearance is <70 mL/min. Obtain renal function tests before starting topiramate and consider monitoring serum bicarbonate for metabolic acidosis (we test at 3 and 6 months, then every 6 months). Because of teratogenic effects of topiramate (eg, cleft lip and palate), rule out pregnancy in all women of childbearing age.

Baclofen is a GABAb receptor agonist that is FDA approved for treating spasticity. Because GABA transmission is down-regulated in chronic AUD, it is a commonly targeted neurotransmitter when developing medications for AUD. GABAa receptors are fast-acting inhibitory ion channels, and its agonists (eg, benzodiazepines) have a significant abuse and cross-addiction liability. GABAb receptors, however, are slow-acting through a complex cascade of intracellular signals, and therefore GABAb agonists such as baclofen have been studied for treating addiction.

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 39), baclofen was superior to placebo in suppressing obsessive aspects of cravings and decreasing state anxiety.11 Baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, in another randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 42) reduced the number of drinks per day by 53% vs placebo; 20 mg 3 times a day resulted in a 68% reduction in drinks per day vs placebo.12 However, a placebo-controlled RCT (n = 80) reported that baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, was not superior to placebo for primary outcomes related to alcohol consumption, although it did significantly decrease cravings and anxiety among persons with AUD.13 Evidence suggests that baclofen might be effective for promoting abstinence, reducing the risk of relapse, and alleviating cravings and anxiety in persons with AUD, although further investigation is needed.

In studies for AUD, the side-effect profile for baclofen was relatively benign.11-13 Nausea, fatigue, sleepiness, vertigo, and abdominal pain were reported; overall, baclofen was found to be safe and to have no abuse liability.7,10,12 The addictive potential of other muscle relaxers may have dissuaded providers from using baclofen for AUD, but we consider it a reasonable alternative when FDA-approved treatments fail.

Because baclofen is primarily eliminated by the kidneys, it may be safe for people with cirrhosis or severe liver disease.12 Baseline renal labs should be performed before administering baclofen and a negative pregnancy test obtained for women of childbearing age.

Ondansetron is a serotonin receptor type 3 (5-HT3) antagonist that has shown promising results for AUD.3,7 Research suggests that 5-HT3 receptors are an action site for alcohol in the brain and are thought to play a role in its rewarding effects.7 Ondansetron may be more effective for early-onset alcoholism (EOA) than late-onset alcoholism (LOA).14,15 EOA (age ≤25) is characterized by strong family history of AUD and prominent antisocial traits. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 271) reported that ondansetron, 4 mcg/kg twice daily, was superior to placebo in reducing number of drinks per day, increasing days abstinent, and reducing cravings in patients with EOA.14 Among persons with EOA, ondansetron, 16 mcg/kg twice daily, significantly reduced the severity of symptoms of fatigue, confusion, and overall mood disturbance such as depression, anxiety, and hostility compared with placebo in an RCT (n = 321).15 The lowest available oral dosage of ondansetron is 4 mg tablets or 4 mg/5 mL solution. We have used 4 mg twice daily for patients who have failed naltrexone and acamprosate or when these agents are contraindicated.

Common side effects of ondansetron include constipation, diarrhea, elevated liver enzymes, tachycardia, headache, and fatigue. Contraindications include congenital long QT syndrome, QTc prolongation risk, or significant hepatic impairment. We suggest evaluating baseline electrocardiogram and liver function tests. Women should undergo a pregnancy test before receiving medications.

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant that is FDA-approved for treating epilepsy and postherpetic neuralgia. Gabapentin is related structurally to GABA and may potentiate central nervous system GABA activity, inhibit glutamate activity, and reduce norepinephrine and dopamine release.16 Gabapentin is thought to balance the GABA/glutamate dysregulation found in early alcohol abstinence and reduce risk for alcohol relapse.16A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 60) demonstrated that gabapentin, 600 mg/d, significantly reduced number of drinks per day and heavy drinking days and increased days of abstinence compared with placebo over 28 days.17 Another double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 150 people used gabapentin, 900 or 1,800 mg/d; there was a linear dose response for increased days abstinent and no heavy drinking days in favor of gabapentin.18

An RCT (N = 150) evaluated adding gabapentin, up to 1200 mg/d, to naltrexone, 50 mg/d, vs naltrexone with placebo or double placebo over 6 weeks of treatment. The combined gabapentin-naltrexone group outperformed the other 2 groups on time to heavy drinking, number of heavy drinking days, and number of drinks per day. Gabapentin’s positive effects on sleep may have mediated some of its beneficial effects.29 In an open-label pilot study, gabapentin was more effective than trazodone for insomnia during early alcohol abstinence.30 Of note, gabapentin is a safe alternative to benzodiazepines for alcohol detoxification in patients with severe hepatic disease or those at risk of interacting with alcohol (eg, outpatients at high risk to drink during detoxification).31 Gabapentin, 400 mg/d to 1,600 mg/d, generally is safe and well tolerated and has some support for improving cravings, reducing alcohol consumption, delaying relapse, and improving sleep in patients with AUD.

Side effects of gabapentin include daytime sedation, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, and dyspepsia. Using 3 divided doses might enhance tolerability. To reduce daytime sedation, we recommend administering most of the dose at night, which also may relieve insomnia. Gabapentin is excreted through the kidney; baseline renal function tests should be performed before initiating treatment, because the dosage might need to be adjusted in people with renal insufficiency.

Bottom Line

FDA-approved (acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram) and off-label (baclofen, gabapentin, ondansetron, and topiramate) agents can help patients with alcohol use disorder achieve abstinence, reduce heavy drinking days, prevent relapse, and maintain sobriety. Research supports the use of pharmacotherapy combined with psychosocial modalities, such as 12-step programs, motivational interviewing, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Related Resources

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide (third edition). www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/evidence-based-approaches-to-drug-addiction-treatment/pharmacotherapi-1.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Incorporating alcohol pharmacotherapies into medical practice. http://162.99.3.213/products/manuals/tips/pdf/TIP49.pdf.

- Pettinati HM, Mattson ME. Medical management treatment manual: A clinical guide for researchers and clinicians providing pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/MedicalManual/MMManual.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral Naltrexone • Vivitrol, ReVia

Baclofen • Lioresal Ondansetron • Zofran

Disulfiram • Antabuse Topiramate • Topamax

Gabapentin • Neurontin Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. World Health Organization. Alcohol fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs349/en/index.html. Published February 2011. Accessed April 30, 2013.

2. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence. The COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017.

3. Mann K. Pharmacotherapy of alcohol dependence a review of the clinical data. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(8):485-504.

4. ReVia [package insert]. Pomona, NY: Barr Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

5. Campral [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2004.

6. Antabuse [package insert]. Pomona, NY: Barr Pharmaceuticals; 2010.

7. Johnson BA. Update on neuropharmacological treatments for alcoholism: scientific basis and clinical findings. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(1):34-56.

8. Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism: a Veterans Administration cooperative study. JAMA. 1986;256(11):1449-1454.

9. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9370):

1677-1685.

10. Ma JZ, Ait-Daoud N, Johnson BA. Topiramate reduces the harm of excessive drinking: implications for public health and primary care. Addiction. 2006;101:1561-1568.

11. Addolorato G, Caputo F, Capristo E, et al. Baclofen efficacy in reducing alcohol craving and intake: a preliminary double-blind randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(5):504-508.

12. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Dose-response effect of baclofen in reducing daily alcohol intake in alcohol dependence: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(3):312-317.

13. Garbutt JC, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Gallop R, et al. Efficacy and safety of baclofen for alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(11):1849-1857.

14. Johnson BA, Roache JD, Javors MA, et al. Ondansetron for reduction of drinking among biologically predisposed alcoholic patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284(8):963-971.

15. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Ma JZ, et al. Ondansetron reduces mood disturbance among biologically predisposed, alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(11):1773-1779.

16. Myrick H, Anton R, Voronin K, et al. A double-blind evaluation of gabapentin on alcohol effects and drinking in a clinical laboratory paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):221-227.

17. Furieri FA, Nakamura-Palacios EM. Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1691-1700.

18. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial [published online November 4, 2013]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950.

19. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of substance use disorders (SUD). http://www.healthquality.va.gov/sud/sud_full_601f.pdf. Published August 2009. Accessed November 22, 2013.

20. Mark TL, Kranzler HR, Song X, et al. Physicians’ opinions about medication to treat alcoholism. Addiction. 2003;98(5):617-626.

21. Thomas CP, Wallack SS, Lee S, et al. Research to practice: adoption of naltrexone in alcoholism treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(1):1-11.

22. Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:267-280.

23. Anton RF. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(7):715-721.

24. Gueorguieva R, Wu R, Pittman B, et al. New insights into the efficacy of naltrexone based on trajectory-based reanalysis of two negative clinical trials. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(11): 1290-1295.

25. Lapham S, Forman R, Alexander M, et al. The effects of extended-release naltrexone on holiday drinking in alcohol-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse. 2009;36(1):1-6.

26. Ciraulo DA, Dong Q, Silverman BL, et al. Early treatment response in alcohol dependence with extended-release naltrexone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):190-195.

27. Mark TL, Montejano LB, Kranzler HR, et al. Comparison of healthcare utilization among patients treated with alcoholism medications. Am J Managed Care. 2010;16(12): 879-888.

28. Mann K, Lehert P, Morgan MY. The efficacy of acamprosate in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol-dependent individuals: results of a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(1):51-63.

29. Anton RF, Myrick H, Wright TM, et al. Gabapentin combined with naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):709-717.

30. Karam-Hage M, Brower KJ. Open pilot study of gabapentin versus trazodone to treat insomnia in alcoholic outpatients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(5):542-544.

31. Myrick H, Malcolm R, Randall PK, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

Historically, alcohol use disorder (AUD; classified as alcohol abuse or dependence in DSM-IV-TR) has been treated with psychosocial therapies, but many patients treated this way relapse into heavy drinking patterns and are unable to sustain sobriety (Box 11). Although vital for treating AUD, psychosocial methods have, to date, a modest success rate. Research has demonstrated that combining pharmacotherapy with psychosocial programs is effective for treating AUD.2

Patients and clinicians might associate AUD medications with so-called aversion therapy because, for many years, the only treatment was disulfiram, which causes unpleasant physical effects when consumed with alcohol. However, newer medications help patients maintain abstinence by targeting brain neurotransmitters relevant to addiction neurocircuitry, such as dopamine, serotonin, ϒ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, and opioid.3 These medications may help patients with AUD achieve sobriety, avoid relapse, decrease heavy drinking days, and delay time to recurrent drinking.

In this article, we review FDA-approved medications (Table 1)4-6 and off-label agents (Table 2)3,7-18 and provide recommendations for treating patients with AUD (Box 2).19-21

FDA-approved treatments

Naltrexone is an opiate antagonist that blocks the mu receptor and is believed to interrupt the dopamine reward pathway in the brain for alcohol. A meta-analysis of 2,861 patients in 24 combined randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated naltrexone to be an effective short-term (12 weeks) treatment for alcoholism, significantly decreasing relapses.22 The large multisite COMBINE study (N = 1,383) showed that naltrexone, 100 mg/d, and medical treatment without behavioral treatment over 16 weeks was more effective than placebo in increasing percentage of days abstinent (80.6% vs 75.1%, respectively) and reducing the percentage of patients experiencing heavy drinking days (66.2% vs 73.1%, respectively).2 Patients who have a family history of AUD or strong cravings, or both, may benefit most from naltrexone.3,7,23 Despite evidence of the effectiveness of naltrexone for AUD, not all studies have yielded positive results.24

Common side effects of naltrexone, if present, appear early in treatment and include GI upset (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), headache, and fatigue.2,3,22,23 Hepatotoxicity has been reported with dosages of 100 to 300 mg/d, but lab values typically normalize when naltrexone is discontinued.2,3,23 Monitor markers of liver function including ϒ-glutamyltransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and bilirubin before and during naltrexone treatment (we check patients 1 to 3 months after starting treatment and yearly thereafter). Obtain a negative urine drug screen for opioids before administering naltrexone, because if opioids were consumed recently naltrexone could precipitate withdrawal. Because of the unknown teratogenicity of naltrexone, women of childbearing age should undergo pregnancy testing before and periodically during naltrexone therapy.

Naltrexone also is available in a once-monthly, 380-mg injectable formulation. Studies show that, similar to its oral counterpart, injectable naltrexone effectively reduces heavy drinking days and number of drinks a day compared with placebo.25,26 Advantages of injectable naltrexone are its extended steady release of medication and its efficacy for patients who do not adhere to oral dosing.7,27 Side effects are similar to oral naltrexone, except for injection site reactions and pain.

Contraindications to naltrexone include current opioid use because its antagonistic effects on opioid receptors render opioid analgesia ineffective. Patients who have used opioids within 7 to 10 days or who may be surreptitiously using opioids should not take naltrexone because it may cause opioid withdrawal. Some patients may try to override the opioid receptor blockade of naltrexone with higher opioid doses, which could result in overdose.

Naltrexone is approved for treating opioid use disorder and may be useful for persons with comorbid opioid use disorder and AUD, if the patient has been adequately detoxified from opioids and intends to abstain from these drugs. Patients who have extensive liver damage secondary to acute hepatitis or uncompensated cirrhosis would not be good candidates for naltrexone because of a risk of hepatotoxicity.2,3,22

Because of ease of dosing, we recommend naltrexone as a first-line treatment for AUD, unless the patient requires opioids or has severe liver disease. We recommend increasing naltrexone from 50 mg to 100 mg before switching to acamprosate, based on European studies.

Acamprosate is a glutamate antagonist that is thought to modulate overactive glutamatergic brain activity that occurs after stopping chronic heavy alcohol use. In a meta-analysis of 17 studies (N = 4,087), continuous abstinence rates at 6 months were significantly higher in acamprosate-treated patients (36.1%) than in patients receiving placebo (23.4%).28 In a review of European studies, acamprosate benefited patients who have increased anxiety, physiological dependence, negative family history of AUD, and late age of onset (age >25) of alcohol dependence.7 However, in the COMBINE trial acamprosate was no more effective than placebo.2

We consider acamprosate an effective option for patients who do not respond to naltrexone or have a contraindication. Dosages of 333 mg to 666 mg, 3 times a day, are recommended, although dosages up to 3 g/d have been studied; titration is not required.2,7,28 We recommend advising patients to continue treatment even if they relapse, because these medications may mitigate relapse severity. Adherence to multiple daily doses can be problematic for some patients, but pairing medications with meals or bedtime may improve adherence.

Diarrhea is the most common side effect of acamprosate; nervousness, fatigue, insomnia, and depression have been reported with high dosages.2,3,7,28 Acamprosate is excreted through the kidney and is safe for patients with liver disorders such as acute hepatitis or cirrhosis. The drug is contraindicated in patients with acute or chronic renal failure with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min; those with less severe renal insufficiency might need a lower dosage. Obtain baseline renal function before starting acamprosate; women of childbearing age should undergo a pregnancy test.

Disulfiram inhibits alcohol metabolism, resulting in acetaldehyde accumulation, which causes unpleasant physical effects such as nausea, vomiting, and hypotension. This creates a negative rather than a positive experience with drinking. A US Veterans Administration Cooperative Study randomized 605 participants to riboflavin, disulfiram, 1 mg/d (an inactive dose), or disulfiram, 250 mg/d (standard dose). There was no difference in percentage of patients remaining abstinent or time to first drink.8 Participants receiving disulfiram, 250 mg/d, had fewer drinking days after relapse compared with the other groups.8

Adverse physical effects produced when disulfiram and alcohol interact include tremor, diaphoresis, unstable blood pressure, and severe diarrhea and vomiting. Disulfiram can cause medically serious reactions in a small percentage of patients, especially those with significant medical comorbidity or advanced age. Patients with severe hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, a history of stroke, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, or renal or hepatic insufficiency should not use disulfiram.3 Patients taking disulfiram should avoid casual exposures to food, aftershave, mouthwash, and hand sanitizer that might contain alcohol. Disulfiram has no significant effect on alcohol craving. Social support to help oversee dosing may enhance adherence.7

Off-label medications

Topiramate is FDA-approved to treat migraine headaches and some seizure disorders. Topiramate facilitates GABA-mediated neuronal inhibition and antagonizes certain glutamate receptor subtypes. In an RCT (N = 150), topiramate, up to 300 mg/d, was more effective than placebo at reducing heavy drinking days and number of drinks per day, increasing days abstinent, and alleviating cravings.9 In a 12-week, double-blind RCT (N = 150), topiramate increased “safe drinking”—defined as ≤1 standard drink per day for women and ≤2 per day for men—vs placebo.10 Dosages were 75 mg to 300 mg/d in twice daily divided doses. Dosing starts at 25 mg/d and increases by 25 to 50 mg a day at weekly intervals. We recommend reserving topiramate for persons who do not respond to or cannot tolerate naltrexone and acamprosate because of the slow titration needed to prevent side effects. Although not studied, it may seem that topiramate’s antiepileptic actions could prevent seizures during alcohol withdrawal, but the protracted titration would limit its utility.

Side effects of topiramate include impaired memory and concentration, paresthesia, and anorexia and are more likely to present during rapid titration or with a high dosage.7,8 Rare reports of spontaneous myopia, angle-closure glaucoma, increased intraocular pressure, ocular pain, and blurry vision have been reported, but these complications often resolve with discontinuation of topiramate.7,8

Topiramate primarily is excreted through the kidney, and its action in the renal tubules can lead to metabolic acidosis or nephrolithiasis.8 Relative contraindications include acute or chronic kidney disease, including kidney stones. Consider slower titration and a 50% reduction in dosing if creatinine clearance is <70 mL/min. Obtain renal function tests before starting topiramate and consider monitoring serum bicarbonate for metabolic acidosis (we test at 3 and 6 months, then every 6 months). Because of teratogenic effects of topiramate (eg, cleft lip and palate), rule out pregnancy in all women of childbearing age.

Baclofen is a GABAb receptor agonist that is FDA approved for treating spasticity. Because GABA transmission is down-regulated in chronic AUD, it is a commonly targeted neurotransmitter when developing medications for AUD. GABAa receptors are fast-acting inhibitory ion channels, and its agonists (eg, benzodiazepines) have a significant abuse and cross-addiction liability. GABAb receptors, however, are slow-acting through a complex cascade of intracellular signals, and therefore GABAb agonists such as baclofen have been studied for treating addiction.

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 39), baclofen was superior to placebo in suppressing obsessive aspects of cravings and decreasing state anxiety.11 Baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, in another randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 42) reduced the number of drinks per day by 53% vs placebo; 20 mg 3 times a day resulted in a 68% reduction in drinks per day vs placebo.12 However, a placebo-controlled RCT (n = 80) reported that baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, was not superior to placebo for primary outcomes related to alcohol consumption, although it did significantly decrease cravings and anxiety among persons with AUD.13 Evidence suggests that baclofen might be effective for promoting abstinence, reducing the risk of relapse, and alleviating cravings and anxiety in persons with AUD, although further investigation is needed.

In studies for AUD, the side-effect profile for baclofen was relatively benign.11-13 Nausea, fatigue, sleepiness, vertigo, and abdominal pain were reported; overall, baclofen was found to be safe and to have no abuse liability.7,10,12 The addictive potential of other muscle relaxers may have dissuaded providers from using baclofen for AUD, but we consider it a reasonable alternative when FDA-approved treatments fail.

Because baclofen is primarily eliminated by the kidneys, it may be safe for people with cirrhosis or severe liver disease.12 Baseline renal labs should be performed before administering baclofen and a negative pregnancy test obtained for women of childbearing age.

Ondansetron is a serotonin receptor type 3 (5-HT3) antagonist that has shown promising results for AUD.3,7 Research suggests that 5-HT3 receptors are an action site for alcohol in the brain and are thought to play a role in its rewarding effects.7 Ondansetron may be more effective for early-onset alcoholism (EOA) than late-onset alcoholism (LOA).14,15 EOA (age ≤25) is characterized by strong family history of AUD and prominent antisocial traits. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 271) reported that ondansetron, 4 mcg/kg twice daily, was superior to placebo in reducing number of drinks per day, increasing days abstinent, and reducing cravings in patients with EOA.14 Among persons with EOA, ondansetron, 16 mcg/kg twice daily, significantly reduced the severity of symptoms of fatigue, confusion, and overall mood disturbance such as depression, anxiety, and hostility compared with placebo in an RCT (n = 321).15 The lowest available oral dosage of ondansetron is 4 mg tablets or 4 mg/5 mL solution. We have used 4 mg twice daily for patients who have failed naltrexone and acamprosate or when these agents are contraindicated.

Common side effects of ondansetron include constipation, diarrhea, elevated liver enzymes, tachycardia, headache, and fatigue. Contraindications include congenital long QT syndrome, QTc prolongation risk, or significant hepatic impairment. We suggest evaluating baseline electrocardiogram and liver function tests. Women should undergo a pregnancy test before receiving medications.

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant that is FDA-approved for treating epilepsy and postherpetic neuralgia. Gabapentin is related structurally to GABA and may potentiate central nervous system GABA activity, inhibit glutamate activity, and reduce norepinephrine and dopamine release.16 Gabapentin is thought to balance the GABA/glutamate dysregulation found in early alcohol abstinence and reduce risk for alcohol relapse.16A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 60) demonstrated that gabapentin, 600 mg/d, significantly reduced number of drinks per day and heavy drinking days and increased days of abstinence compared with placebo over 28 days.17 Another double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 150 people used gabapentin, 900 or 1,800 mg/d; there was a linear dose response for increased days abstinent and no heavy drinking days in favor of gabapentin.18

An RCT (N = 150) evaluated adding gabapentin, up to 1200 mg/d, to naltrexone, 50 mg/d, vs naltrexone with placebo or double placebo over 6 weeks of treatment. The combined gabapentin-naltrexone group outperformed the other 2 groups on time to heavy drinking, number of heavy drinking days, and number of drinks per day. Gabapentin’s positive effects on sleep may have mediated some of its beneficial effects.29 In an open-label pilot study, gabapentin was more effective than trazodone for insomnia during early alcohol abstinence.30 Of note, gabapentin is a safe alternative to benzodiazepines for alcohol detoxification in patients with severe hepatic disease or those at risk of interacting with alcohol (eg, outpatients at high risk to drink during detoxification).31 Gabapentin, 400 mg/d to 1,600 mg/d, generally is safe and well tolerated and has some support for improving cravings, reducing alcohol consumption, delaying relapse, and improving sleep in patients with AUD.

Side effects of gabapentin include daytime sedation, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, and dyspepsia. Using 3 divided doses might enhance tolerability. To reduce daytime sedation, we recommend administering most of the dose at night, which also may relieve insomnia. Gabapentin is excreted through the kidney; baseline renal function tests should be performed before initiating treatment, because the dosage might need to be adjusted in people with renal insufficiency.

Bottom Line

FDA-approved (acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram) and off-label (baclofen, gabapentin, ondansetron, and topiramate) agents can help patients with alcohol use disorder achieve abstinence, reduce heavy drinking days, prevent relapse, and maintain sobriety. Research supports the use of pharmacotherapy combined with psychosocial modalities, such as 12-step programs, motivational interviewing, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Related Resources

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide (third edition). www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/evidence-based-approaches-to-drug-addiction-treatment/pharmacotherapi-1.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Incorporating alcohol pharmacotherapies into medical practice. http://162.99.3.213/products/manuals/tips/pdf/TIP49.pdf.

- Pettinati HM, Mattson ME. Medical management treatment manual: A clinical guide for researchers and clinicians providing pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/MedicalManual/MMManual.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral Naltrexone • Vivitrol, ReVia

Baclofen • Lioresal Ondansetron • Zofran

Disulfiram • Antabuse Topiramate • Topamax

Gabapentin • Neurontin Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Historically, alcohol use disorder (AUD; classified as alcohol abuse or dependence in DSM-IV-TR) has been treated with psychosocial therapies, but many patients treated this way relapse into heavy drinking patterns and are unable to sustain sobriety (Box 11). Although vital for treating AUD, psychosocial methods have, to date, a modest success rate. Research has demonstrated that combining pharmacotherapy with psychosocial programs is effective for treating AUD.2

Patients and clinicians might associate AUD medications with so-called aversion therapy because, for many years, the only treatment was disulfiram, which causes unpleasant physical effects when consumed with alcohol. However, newer medications help patients maintain abstinence by targeting brain neurotransmitters relevant to addiction neurocircuitry, such as dopamine, serotonin, ϒ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, and opioid.3 These medications may help patients with AUD achieve sobriety, avoid relapse, decrease heavy drinking days, and delay time to recurrent drinking.

In this article, we review FDA-approved medications (Table 1)4-6 and off-label agents (Table 2)3,7-18 and provide recommendations for treating patients with AUD (Box 2).19-21

FDA-approved treatments

Naltrexone is an opiate antagonist that blocks the mu receptor and is believed to interrupt the dopamine reward pathway in the brain for alcohol. A meta-analysis of 2,861 patients in 24 combined randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated naltrexone to be an effective short-term (12 weeks) treatment for alcoholism, significantly decreasing relapses.22 The large multisite COMBINE study (N = 1,383) showed that naltrexone, 100 mg/d, and medical treatment without behavioral treatment over 16 weeks was more effective than placebo in increasing percentage of days abstinent (80.6% vs 75.1%, respectively) and reducing the percentage of patients experiencing heavy drinking days (66.2% vs 73.1%, respectively).2 Patients who have a family history of AUD or strong cravings, or both, may benefit most from naltrexone.3,7,23 Despite evidence of the effectiveness of naltrexone for AUD, not all studies have yielded positive results.24

Common side effects of naltrexone, if present, appear early in treatment and include GI upset (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), headache, and fatigue.2,3,22,23 Hepatotoxicity has been reported with dosages of 100 to 300 mg/d, but lab values typically normalize when naltrexone is discontinued.2,3,23 Monitor markers of liver function including ϒ-glutamyltransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and bilirubin before and during naltrexone treatment (we check patients 1 to 3 months after starting treatment and yearly thereafter). Obtain a negative urine drug screen for opioids before administering naltrexone, because if opioids were consumed recently naltrexone could precipitate withdrawal. Because of the unknown teratogenicity of naltrexone, women of childbearing age should undergo pregnancy testing before and periodically during naltrexone therapy.

Naltrexone also is available in a once-monthly, 380-mg injectable formulation. Studies show that, similar to its oral counterpart, injectable naltrexone effectively reduces heavy drinking days and number of drinks a day compared with placebo.25,26 Advantages of injectable naltrexone are its extended steady release of medication and its efficacy for patients who do not adhere to oral dosing.7,27 Side effects are similar to oral naltrexone, except for injection site reactions and pain.

Contraindications to naltrexone include current opioid use because its antagonistic effects on opioid receptors render opioid analgesia ineffective. Patients who have used opioids within 7 to 10 days or who may be surreptitiously using opioids should not take naltrexone because it may cause opioid withdrawal. Some patients may try to override the opioid receptor blockade of naltrexone with higher opioid doses, which could result in overdose.

Naltrexone is approved for treating opioid use disorder and may be useful for persons with comorbid opioid use disorder and AUD, if the patient has been adequately detoxified from opioids and intends to abstain from these drugs. Patients who have extensive liver damage secondary to acute hepatitis or uncompensated cirrhosis would not be good candidates for naltrexone because of a risk of hepatotoxicity.2,3,22

Because of ease of dosing, we recommend naltrexone as a first-line treatment for AUD, unless the patient requires opioids or has severe liver disease. We recommend increasing naltrexone from 50 mg to 100 mg before switching to acamprosate, based on European studies.

Acamprosate is a glutamate antagonist that is thought to modulate overactive glutamatergic brain activity that occurs after stopping chronic heavy alcohol use. In a meta-analysis of 17 studies (N = 4,087), continuous abstinence rates at 6 months were significantly higher in acamprosate-treated patients (36.1%) than in patients receiving placebo (23.4%).28 In a review of European studies, acamprosate benefited patients who have increased anxiety, physiological dependence, negative family history of AUD, and late age of onset (age >25) of alcohol dependence.7 However, in the COMBINE trial acamprosate was no more effective than placebo.2

We consider acamprosate an effective option for patients who do not respond to naltrexone or have a contraindication. Dosages of 333 mg to 666 mg, 3 times a day, are recommended, although dosages up to 3 g/d have been studied; titration is not required.2,7,28 We recommend advising patients to continue treatment even if they relapse, because these medications may mitigate relapse severity. Adherence to multiple daily doses can be problematic for some patients, but pairing medications with meals or bedtime may improve adherence.

Diarrhea is the most common side effect of acamprosate; nervousness, fatigue, insomnia, and depression have been reported with high dosages.2,3,7,28 Acamprosate is excreted through the kidney and is safe for patients with liver disorders such as acute hepatitis or cirrhosis. The drug is contraindicated in patients with acute or chronic renal failure with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min; those with less severe renal insufficiency might need a lower dosage. Obtain baseline renal function before starting acamprosate; women of childbearing age should undergo a pregnancy test.

Disulfiram inhibits alcohol metabolism, resulting in acetaldehyde accumulation, which causes unpleasant physical effects such as nausea, vomiting, and hypotension. This creates a negative rather than a positive experience with drinking. A US Veterans Administration Cooperative Study randomized 605 participants to riboflavin, disulfiram, 1 mg/d (an inactive dose), or disulfiram, 250 mg/d (standard dose). There was no difference in percentage of patients remaining abstinent or time to first drink.8 Participants receiving disulfiram, 250 mg/d, had fewer drinking days after relapse compared with the other groups.8

Adverse physical effects produced when disulfiram and alcohol interact include tremor, diaphoresis, unstable blood pressure, and severe diarrhea and vomiting. Disulfiram can cause medically serious reactions in a small percentage of patients, especially those with significant medical comorbidity or advanced age. Patients with severe hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, a history of stroke, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, or renal or hepatic insufficiency should not use disulfiram.3 Patients taking disulfiram should avoid casual exposures to food, aftershave, mouthwash, and hand sanitizer that might contain alcohol. Disulfiram has no significant effect on alcohol craving. Social support to help oversee dosing may enhance adherence.7

Off-label medications

Topiramate is FDA-approved to treat migraine headaches and some seizure disorders. Topiramate facilitates GABA-mediated neuronal inhibition and antagonizes certain glutamate receptor subtypes. In an RCT (N = 150), topiramate, up to 300 mg/d, was more effective than placebo at reducing heavy drinking days and number of drinks per day, increasing days abstinent, and alleviating cravings.9 In a 12-week, double-blind RCT (N = 150), topiramate increased “safe drinking”—defined as ≤1 standard drink per day for women and ≤2 per day for men—vs placebo.10 Dosages were 75 mg to 300 mg/d in twice daily divided doses. Dosing starts at 25 mg/d and increases by 25 to 50 mg a day at weekly intervals. We recommend reserving topiramate for persons who do not respond to or cannot tolerate naltrexone and acamprosate because of the slow titration needed to prevent side effects. Although not studied, it may seem that topiramate’s antiepileptic actions could prevent seizures during alcohol withdrawal, but the protracted titration would limit its utility.

Side effects of topiramate include impaired memory and concentration, paresthesia, and anorexia and are more likely to present during rapid titration or with a high dosage.7,8 Rare reports of spontaneous myopia, angle-closure glaucoma, increased intraocular pressure, ocular pain, and blurry vision have been reported, but these complications often resolve with discontinuation of topiramate.7,8

Topiramate primarily is excreted through the kidney, and its action in the renal tubules can lead to metabolic acidosis or nephrolithiasis.8 Relative contraindications include acute or chronic kidney disease, including kidney stones. Consider slower titration and a 50% reduction in dosing if creatinine clearance is <70 mL/min. Obtain renal function tests before starting topiramate and consider monitoring serum bicarbonate for metabolic acidosis (we test at 3 and 6 months, then every 6 months). Because of teratogenic effects of topiramate (eg, cleft lip and palate), rule out pregnancy in all women of childbearing age.