User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Opiates and psychotropics: Pharmacokinetics for practitioners

• When choosing pharmacologic therapy, make sure that all medications your patient takes are documented, consider drug-drug interactions, and instruct the patient to notify you of any new medications.

• In addition to toxicity, loss of efficacy of some opiate drugs may occur as a result of metabolic inhibition or induction by psychotropic medications.

• Collaborate with the physician who is prescribing the opioid if psychotropic choices are limited. The patient’s pain may be treated adequately with another analgesic that does not interact with the psychotropic that has been chosen.

As prescribed by his internist, Mr. G, age 44, takes 10 mg of methadone every 4 hours for chronic back pain secondary to a work-related injury 3 years ago. He experiences minimal sedation. Mr. G presents for psychiatric evaluation with complaints of increasing irritability, poor focus, low energy, and lack of interest in usual activities. The psychiatrist diagnoses him with depressive disorder not otherwise specified, and prescribes fluoxetine, 20 mg/d. Three weeks later, Mr. G’s wife contacts the psychiatrist reporting that her husband seems “overmedicated” and describes excess drowsiness and slowed thought processing.

After discussion with Mr. G’s internist and pharmacist, the psychiatrist decides that this oversedation may represent a drug-drug interaction between methadone and fluoxetine resulting in higher-than-expected methadone serum levels. Mr. G is instructed to stop fluoxetine with no taper, and his methadone dose is lowered with good results. Over the next 2 weeks Mr. G is titrated back to his original methadone dose and is re-evaluated by the psychiatrist to discuss medication options to address his depression.

Psychiatrists commonly encounter patients who receive opiate medications for chronic pain. Being aware of potential drug-drug interactions between opiate medications and psychotropics can help avoid adverse effects and combinations that may affect the efficacy of either drug. Pharmacokinetic interactions may affect your choice of psychiatric medication and should be taken into account when addressing adverse effects in any patient who takes opiates and psychotropics.

Metabolic pathways

The primary metabolic pathways for opiate metabolism are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes. Depending on the agent used, prescribers may need to consider interactions for both pathways (Table 11,2 and Table 21). For example, oxycodone is metabolized via 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes and is a potent analgesic with oxymorphone and noroxycodone as its active metabolites. These metabolites, however, make a negligible contribution to oxycodone’s analgesic effect.3,4 Metabolism by the 3A4 isoenzyme is the principal oxidative pathway and the 2D6 site accounts for approximately 10% of oxycodone metabolism. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study showed that 2D6 inhibition by paroxetine had no significant effect on oxycodone levels; however, a combination of paroxetine and itraconazole, a potent 3A4 inhibitor, resulted in substantial increases in oxycodone plasma levels.5 Remain vigilant for possible opiate toxicity when administering oxycodone with 3A4 inhibitors.

Methadone and meperidine also involve dual pathways. Methadone is metabolized primarily by 3A4 and 2B6, with 2D6 playing a smaller role.6 CYP2D6 seems to play an important part in metabolizing the R-enantiomer of methadone, which is largely responsible for the drug’s opiate effects, such as analgesia and respiratory depression.7,8 Induction of the 3A4 isoenzyme may result in methadone withdrawal, and inhibition may cause methadone toxicity.9 Inducers of 3A4, such as carbamazepine, and inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, should be avoided or used very cautiously in patients taking methadone. The 2B6 and 2D6 isoenzymes also may increase or decrease methadone levels and should be treated similarly. In Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine inhibited all 3 isoenzymes that are primarily responsible for methadone metabolism. A better antidepressant choice for Mr. G may have been venlafaxine, which is known to only mildly inhibit 2D6, or mirtazapine, which does not seem to inhibit the major CYP isoforms to an appreciable degree.10

Although the full scope of meperidine metabolism has not been identified,9 an in vitro test demonstrated that 2B6 and 3A4 play important roles in metabolizing meperidine to normeperidine, its major metabolite.11 Normeperidine does not provide analgesia and is associated with neurotoxicity, including anxiety, tremor, muscle twitching, and seizure.12 Agents that induce 3A4—such as carbamazepine or St. John’s wort—may contribute to neurotoxicity.9 Inhibition of these isoenzymes may increase meperidine levels and lead to anticholinergic toxicity or respiratory and central nervous system depression.13,14

Opiates metabolized by the 2D6 isoenzyme include codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol. The analgesic effect of codeine seems dependent on 2D6 metabolism. Via this pathway, codeine is converted into morphine, which has a 300-times stronger affinity for the μ opioid receptor compared with codeine. 2D6 poor metabolizers have shown codeine intolerance and toxicity.3 Psychotropics known to strongly inhibit 2D6 isoenzyme processes—such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—should be avoided in patients taking codeine to prevent adverse effects and potential loss of efficacy. Better antidepressant choices include citalopram or venlafaxine, which inhibit 2D6 to a lesser degree.

Hydrocodone may be a viable option for patients taking 2D6 inhibitors. Hydrocodone is metabolized by 2D6 into hydromorphone, which is 7 to 33 times more potent than hydrocodone.15 Unlike codeine, 2D6 inhibition may have little effect on hydrocodone’s analgesic properties. Animal studies have shown that inhibition of the CYP analog to 2D6 does not affect analgesic response. In humans, 2D6 inhibition does not seem to affect hydrocodone’s abuse liability.16 Two case reports describe known 2D6 poor metabolizers who showed at least a partial response to hydrocodone.15,16

Tramadol’s analgesic properties may be related to serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. It is less potent than codeine but is metabolized via the 2D6 isoenzyme into 0-desmethyltramadol, which is up to 200 times stronger than its parent compound.17 Clinicians should be aware that tramadol’s efficacy may be decreased when coadministered with 2D6 inhibitors. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, paroxetine, a potent 2D6 inhibitor, was shown to lessen the analgesic effect of tramadol.18

The 3A4 site is the primary pathway for fentanyl metabolism. Agents that inhibit 3A4 could increase fentanyl plasma concentration, leading to respiratory depression.19 Examples of 3A4 inhibitors include fluoxetine and fluvoxamine.

Psychotropics may inhibit or induce P450 isoenzymes to varying degrees. For example, paroxetine and citalopram are known to inhibit 2D6 but paroxetine is a stronger inhibitor; therefore, a significant drug-drug interaction is more likely with paroxetine and a 2D6 substrate than the same substrate administered with citalopram.

Table 1

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibited and induced by psychotropics

| Isoenzyme | Potency | Psychotropic(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Moderate | Carbamazepine |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine |

| Moderate | Sertraline | |

| Potent | Paroxetine | |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Mild | Venlafaxine |

| Mild to moderate | Citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, risperidone | |

| Moderate | Duloxetine | |

| Moderate to potent | Bupropion | |

| Potent | Fluoxetine, haloperidol, paroxetine | |

| Dose-dependent | Sertraline | |

| 3A4 inducer | Potent | Carbamazepine |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Mild | Sertraline |

| Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | |

| Source: References 1,2 | ||

Table 2

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibiting and inducing opiate metabolism

| Isoenzyme | Opiates |

|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Methadone |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Meperidine, methadone |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Codeine (may involve loss of efficacy as well as toxicity), methadone, tramadol (may involve loss of efficacy) |

| 3A4 inducer | Meperidine, methadone |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Fentanyl, oxycodone, meperidine, methadone |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Other considerations

In addition to pharmacokinetic interactions, it is important to consider synergistic effects of some opiates and psychotropics. Examples include:

- additive effect on respiratory depression by benzodiazepines and opiates

- increased risk of serotonin syndrome and seizure when using tramadol with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants

- additive prolongation of the QTc interval by methadone when used with psychotropics known to prolong the QTc, such as ziprasidone.9,17,20

Careful attention to these interactions and collaboration among providers can ensure the best outcome for our patients. In Mr. G’s case, collaboration with his internist would be in order, particularly if antidepressant choices are limited. In consultation with the psychiatrist, the internist might choose another opiate to treat Mr. G’s pain that would not interact with fluoxetine. If Mr. G and his physician have struggled to manage his pain and if he is stable on the current regimen, selecting a different antidepressant may be warranted.

Related Resources

- Indiana University School of Medicine drug interactions: cytochrome P450 drug interaction table. http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.asp.

- Ferrando SJ, Levenson JL, Owen JA, eds. Clinical manual of psychopharmacology in the medically ill. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2010.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fentanyl • Duragesic, Actiq

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Lortab, Vicodin, others

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Meperidine • Demerol

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Morphine • Avinza, Duramorph, others

- Oxycodone • OxyContin, Roxicodone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:464-494.

2. Faucette SR, Wang H, Hamilton GA. Regulation of CYP2B6 in primary human hepatocytes by prototypical inducers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(3):348-358.

3. Smith HS. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:613-624.

4. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of morphine codeine, and their derivatives: theory and clinical reality, part II. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:515-520.

5. Grönlund J, Saari TI, Hagelberg NM, et al. Exposure to oral oxycodone is increased by concomitant inhibition of CYP2D6 and 3A4 pathways, but not by inhibition of CYP2D6 alone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:78-87.

6. Leavitt SB. Methadone-drug* interactions. (*medications illicit drugs, and other substances). 3rd ed. Mundelein, IL: Addiction Treatment Forum; 2005.

7. Pérez de los Cobos J, Siñol N, Trujols J, et al. Association of CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer genotype with deficient patient satisfaction regarding methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:190-194.

8. Kristensen K, Christensen CB, Christrup LL. The mu1 mu2, delta, kappa opioid receptor binding profiles of methadone stereoisomers and morphine. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL45-50.

9. Armstrong SC, Wynn GH, Sandson NB. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of synthetic opiate analgesics. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:169-176.

10. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

11. Ramírez J, Innocenti F, Schuetz EG, et al. CYP2B6, CYP3A4, and CYP2C19 are responsible for the in vitro N-demethylation of meperidine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:930-936.

12. Kaiko RF, Foley KM, Grabinski PY, et al. Central nervous system excitatory effects of meperidine in cancer patients. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:180-185.

13. Chalverus C. Clinically important meperidine toxicities. Journal of Pharmaceutical Care in Pain and Symptom Control. 2001;9:37-55.

14. Beckwith MC, Fox ER, Chandramouli J. Removing meperidine from the health-system formulary—frequently asked questions. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2002;16:45-59.

15. Foster A, Mobley E, Wang Z. Complicated pain management in a CYP450 2D6 poor metabolizer. Pain Pract. 2007;7:352-356.

16. Susce MT, Murray-Carmichael E, de Leon J. Response to hydrocodone codeine and oxycodone in a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1356-1358.

17. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Tramadol: seizures serotonin syndrome, and coadministered antidepressants. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6:17-21.

18. Laugesen S, Enggaard TP, Pedersen RS, et al. Paroxetine, a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, diminishes the stereoselective O-demethylation and reduces the hypoalgesic effect of tramadol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:312-323.

19. Duragesic [package insert]. Raritan NJ: Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

20. Caplehorn JR, Drummer OH. Fatal methadone toxicity: signs and circumstances and the role of benzodiazepines. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:358-362;discussion 362–363.

• When choosing pharmacologic therapy, make sure that all medications your patient takes are documented, consider drug-drug interactions, and instruct the patient to notify you of any new medications.

• In addition to toxicity, loss of efficacy of some opiate drugs may occur as a result of metabolic inhibition or induction by psychotropic medications.

• Collaborate with the physician who is prescribing the opioid if psychotropic choices are limited. The patient’s pain may be treated adequately with another analgesic that does not interact with the psychotropic that has been chosen.

As prescribed by his internist, Mr. G, age 44, takes 10 mg of methadone every 4 hours for chronic back pain secondary to a work-related injury 3 years ago. He experiences minimal sedation. Mr. G presents for psychiatric evaluation with complaints of increasing irritability, poor focus, low energy, and lack of interest in usual activities. The psychiatrist diagnoses him with depressive disorder not otherwise specified, and prescribes fluoxetine, 20 mg/d. Three weeks later, Mr. G’s wife contacts the psychiatrist reporting that her husband seems “overmedicated” and describes excess drowsiness and slowed thought processing.

After discussion with Mr. G’s internist and pharmacist, the psychiatrist decides that this oversedation may represent a drug-drug interaction between methadone and fluoxetine resulting in higher-than-expected methadone serum levels. Mr. G is instructed to stop fluoxetine with no taper, and his methadone dose is lowered with good results. Over the next 2 weeks Mr. G is titrated back to his original methadone dose and is re-evaluated by the psychiatrist to discuss medication options to address his depression.

Psychiatrists commonly encounter patients who receive opiate medications for chronic pain. Being aware of potential drug-drug interactions between opiate medications and psychotropics can help avoid adverse effects and combinations that may affect the efficacy of either drug. Pharmacokinetic interactions may affect your choice of psychiatric medication and should be taken into account when addressing adverse effects in any patient who takes opiates and psychotropics.

Metabolic pathways

The primary metabolic pathways for opiate metabolism are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes. Depending on the agent used, prescribers may need to consider interactions for both pathways (Table 11,2 and Table 21). For example, oxycodone is metabolized via 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes and is a potent analgesic with oxymorphone and noroxycodone as its active metabolites. These metabolites, however, make a negligible contribution to oxycodone’s analgesic effect.3,4 Metabolism by the 3A4 isoenzyme is the principal oxidative pathway and the 2D6 site accounts for approximately 10% of oxycodone metabolism. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study showed that 2D6 inhibition by paroxetine had no significant effect on oxycodone levels; however, a combination of paroxetine and itraconazole, a potent 3A4 inhibitor, resulted in substantial increases in oxycodone plasma levels.5 Remain vigilant for possible opiate toxicity when administering oxycodone with 3A4 inhibitors.

Methadone and meperidine also involve dual pathways. Methadone is metabolized primarily by 3A4 and 2B6, with 2D6 playing a smaller role.6 CYP2D6 seems to play an important part in metabolizing the R-enantiomer of methadone, which is largely responsible for the drug’s opiate effects, such as analgesia and respiratory depression.7,8 Induction of the 3A4 isoenzyme may result in methadone withdrawal, and inhibition may cause methadone toxicity.9 Inducers of 3A4, such as carbamazepine, and inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, should be avoided or used very cautiously in patients taking methadone. The 2B6 and 2D6 isoenzymes also may increase or decrease methadone levels and should be treated similarly. In Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine inhibited all 3 isoenzymes that are primarily responsible for methadone metabolism. A better antidepressant choice for Mr. G may have been venlafaxine, which is known to only mildly inhibit 2D6, or mirtazapine, which does not seem to inhibit the major CYP isoforms to an appreciable degree.10

Although the full scope of meperidine metabolism has not been identified,9 an in vitro test demonstrated that 2B6 and 3A4 play important roles in metabolizing meperidine to normeperidine, its major metabolite.11 Normeperidine does not provide analgesia and is associated with neurotoxicity, including anxiety, tremor, muscle twitching, and seizure.12 Agents that induce 3A4—such as carbamazepine or St. John’s wort—may contribute to neurotoxicity.9 Inhibition of these isoenzymes may increase meperidine levels and lead to anticholinergic toxicity or respiratory and central nervous system depression.13,14

Opiates metabolized by the 2D6 isoenzyme include codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol. The analgesic effect of codeine seems dependent on 2D6 metabolism. Via this pathway, codeine is converted into morphine, which has a 300-times stronger affinity for the μ opioid receptor compared with codeine. 2D6 poor metabolizers have shown codeine intolerance and toxicity.3 Psychotropics known to strongly inhibit 2D6 isoenzyme processes—such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—should be avoided in patients taking codeine to prevent adverse effects and potential loss of efficacy. Better antidepressant choices include citalopram or venlafaxine, which inhibit 2D6 to a lesser degree.

Hydrocodone may be a viable option for patients taking 2D6 inhibitors. Hydrocodone is metabolized by 2D6 into hydromorphone, which is 7 to 33 times more potent than hydrocodone.15 Unlike codeine, 2D6 inhibition may have little effect on hydrocodone’s analgesic properties. Animal studies have shown that inhibition of the CYP analog to 2D6 does not affect analgesic response. In humans, 2D6 inhibition does not seem to affect hydrocodone’s abuse liability.16 Two case reports describe known 2D6 poor metabolizers who showed at least a partial response to hydrocodone.15,16

Tramadol’s analgesic properties may be related to serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. It is less potent than codeine but is metabolized via the 2D6 isoenzyme into 0-desmethyltramadol, which is up to 200 times stronger than its parent compound.17 Clinicians should be aware that tramadol’s efficacy may be decreased when coadministered with 2D6 inhibitors. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, paroxetine, a potent 2D6 inhibitor, was shown to lessen the analgesic effect of tramadol.18

The 3A4 site is the primary pathway for fentanyl metabolism. Agents that inhibit 3A4 could increase fentanyl plasma concentration, leading to respiratory depression.19 Examples of 3A4 inhibitors include fluoxetine and fluvoxamine.

Psychotropics may inhibit or induce P450 isoenzymes to varying degrees. For example, paroxetine and citalopram are known to inhibit 2D6 but paroxetine is a stronger inhibitor; therefore, a significant drug-drug interaction is more likely with paroxetine and a 2D6 substrate than the same substrate administered with citalopram.

Table 1

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibited and induced by psychotropics

| Isoenzyme | Potency | Psychotropic(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Moderate | Carbamazepine |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine |

| Moderate | Sertraline | |

| Potent | Paroxetine | |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Mild | Venlafaxine |

| Mild to moderate | Citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, risperidone | |

| Moderate | Duloxetine | |

| Moderate to potent | Bupropion | |

| Potent | Fluoxetine, haloperidol, paroxetine | |

| Dose-dependent | Sertraline | |

| 3A4 inducer | Potent | Carbamazepine |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Mild | Sertraline |

| Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | |

| Source: References 1,2 | ||

Table 2

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibiting and inducing opiate metabolism

| Isoenzyme | Opiates |

|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Methadone |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Meperidine, methadone |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Codeine (may involve loss of efficacy as well as toxicity), methadone, tramadol (may involve loss of efficacy) |

| 3A4 inducer | Meperidine, methadone |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Fentanyl, oxycodone, meperidine, methadone |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Other considerations

In addition to pharmacokinetic interactions, it is important to consider synergistic effects of some opiates and psychotropics. Examples include:

- additive effect on respiratory depression by benzodiazepines and opiates

- increased risk of serotonin syndrome and seizure when using tramadol with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants

- additive prolongation of the QTc interval by methadone when used with psychotropics known to prolong the QTc, such as ziprasidone.9,17,20

Careful attention to these interactions and collaboration among providers can ensure the best outcome for our patients. In Mr. G’s case, collaboration with his internist would be in order, particularly if antidepressant choices are limited. In consultation with the psychiatrist, the internist might choose another opiate to treat Mr. G’s pain that would not interact with fluoxetine. If Mr. G and his physician have struggled to manage his pain and if he is stable on the current regimen, selecting a different antidepressant may be warranted.

Related Resources

- Indiana University School of Medicine drug interactions: cytochrome P450 drug interaction table. http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.asp.

- Ferrando SJ, Levenson JL, Owen JA, eds. Clinical manual of psychopharmacology in the medically ill. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2010.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fentanyl • Duragesic, Actiq

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Lortab, Vicodin, others

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Meperidine • Demerol

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Morphine • Avinza, Duramorph, others

- Oxycodone • OxyContin, Roxicodone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

• When choosing pharmacologic therapy, make sure that all medications your patient takes are documented, consider drug-drug interactions, and instruct the patient to notify you of any new medications.

• In addition to toxicity, loss of efficacy of some opiate drugs may occur as a result of metabolic inhibition or induction by psychotropic medications.

• Collaborate with the physician who is prescribing the opioid if psychotropic choices are limited. The patient’s pain may be treated adequately with another analgesic that does not interact with the psychotropic that has been chosen.

As prescribed by his internist, Mr. G, age 44, takes 10 mg of methadone every 4 hours for chronic back pain secondary to a work-related injury 3 years ago. He experiences minimal sedation. Mr. G presents for psychiatric evaluation with complaints of increasing irritability, poor focus, low energy, and lack of interest in usual activities. The psychiatrist diagnoses him with depressive disorder not otherwise specified, and prescribes fluoxetine, 20 mg/d. Three weeks later, Mr. G’s wife contacts the psychiatrist reporting that her husband seems “overmedicated” and describes excess drowsiness and slowed thought processing.

After discussion with Mr. G’s internist and pharmacist, the psychiatrist decides that this oversedation may represent a drug-drug interaction between methadone and fluoxetine resulting in higher-than-expected methadone serum levels. Mr. G is instructed to stop fluoxetine with no taper, and his methadone dose is lowered with good results. Over the next 2 weeks Mr. G is titrated back to his original methadone dose and is re-evaluated by the psychiatrist to discuss medication options to address his depression.

Psychiatrists commonly encounter patients who receive opiate medications for chronic pain. Being aware of potential drug-drug interactions between opiate medications and psychotropics can help avoid adverse effects and combinations that may affect the efficacy of either drug. Pharmacokinetic interactions may affect your choice of psychiatric medication and should be taken into account when addressing adverse effects in any patient who takes opiates and psychotropics.

Metabolic pathways

The primary metabolic pathways for opiate metabolism are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes. Depending on the agent used, prescribers may need to consider interactions for both pathways (Table 11,2 and Table 21). For example, oxycodone is metabolized via 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes and is a potent analgesic with oxymorphone and noroxycodone as its active metabolites. These metabolites, however, make a negligible contribution to oxycodone’s analgesic effect.3,4 Metabolism by the 3A4 isoenzyme is the principal oxidative pathway and the 2D6 site accounts for approximately 10% of oxycodone metabolism. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study showed that 2D6 inhibition by paroxetine had no significant effect on oxycodone levels; however, a combination of paroxetine and itraconazole, a potent 3A4 inhibitor, resulted in substantial increases in oxycodone plasma levels.5 Remain vigilant for possible opiate toxicity when administering oxycodone with 3A4 inhibitors.

Methadone and meperidine also involve dual pathways. Methadone is metabolized primarily by 3A4 and 2B6, with 2D6 playing a smaller role.6 CYP2D6 seems to play an important part in metabolizing the R-enantiomer of methadone, which is largely responsible for the drug’s opiate effects, such as analgesia and respiratory depression.7,8 Induction of the 3A4 isoenzyme may result in methadone withdrawal, and inhibition may cause methadone toxicity.9 Inducers of 3A4, such as carbamazepine, and inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, should be avoided or used very cautiously in patients taking methadone. The 2B6 and 2D6 isoenzymes also may increase or decrease methadone levels and should be treated similarly. In Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine inhibited all 3 isoenzymes that are primarily responsible for methadone metabolism. A better antidepressant choice for Mr. G may have been venlafaxine, which is known to only mildly inhibit 2D6, or mirtazapine, which does not seem to inhibit the major CYP isoforms to an appreciable degree.10

Although the full scope of meperidine metabolism has not been identified,9 an in vitro test demonstrated that 2B6 and 3A4 play important roles in metabolizing meperidine to normeperidine, its major metabolite.11 Normeperidine does not provide analgesia and is associated with neurotoxicity, including anxiety, tremor, muscle twitching, and seizure.12 Agents that induce 3A4—such as carbamazepine or St. John’s wort—may contribute to neurotoxicity.9 Inhibition of these isoenzymes may increase meperidine levels and lead to anticholinergic toxicity or respiratory and central nervous system depression.13,14

Opiates metabolized by the 2D6 isoenzyme include codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol. The analgesic effect of codeine seems dependent on 2D6 metabolism. Via this pathway, codeine is converted into morphine, which has a 300-times stronger affinity for the μ opioid receptor compared with codeine. 2D6 poor metabolizers have shown codeine intolerance and toxicity.3 Psychotropics known to strongly inhibit 2D6 isoenzyme processes—such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—should be avoided in patients taking codeine to prevent adverse effects and potential loss of efficacy. Better antidepressant choices include citalopram or venlafaxine, which inhibit 2D6 to a lesser degree.

Hydrocodone may be a viable option for patients taking 2D6 inhibitors. Hydrocodone is metabolized by 2D6 into hydromorphone, which is 7 to 33 times more potent than hydrocodone.15 Unlike codeine, 2D6 inhibition may have little effect on hydrocodone’s analgesic properties. Animal studies have shown that inhibition of the CYP analog to 2D6 does not affect analgesic response. In humans, 2D6 inhibition does not seem to affect hydrocodone’s abuse liability.16 Two case reports describe known 2D6 poor metabolizers who showed at least a partial response to hydrocodone.15,16

Tramadol’s analgesic properties may be related to serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. It is less potent than codeine but is metabolized via the 2D6 isoenzyme into 0-desmethyltramadol, which is up to 200 times stronger than its parent compound.17 Clinicians should be aware that tramadol’s efficacy may be decreased when coadministered with 2D6 inhibitors. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, paroxetine, a potent 2D6 inhibitor, was shown to lessen the analgesic effect of tramadol.18

The 3A4 site is the primary pathway for fentanyl metabolism. Agents that inhibit 3A4 could increase fentanyl plasma concentration, leading to respiratory depression.19 Examples of 3A4 inhibitors include fluoxetine and fluvoxamine.

Psychotropics may inhibit or induce P450 isoenzymes to varying degrees. For example, paroxetine and citalopram are known to inhibit 2D6 but paroxetine is a stronger inhibitor; therefore, a significant drug-drug interaction is more likely with paroxetine and a 2D6 substrate than the same substrate administered with citalopram.

Table 1

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibited and induced by psychotropics

| Isoenzyme | Potency | Psychotropic(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Moderate | Carbamazepine |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine |

| Moderate | Sertraline | |

| Potent | Paroxetine | |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Mild | Venlafaxine |

| Mild to moderate | Citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, risperidone | |

| Moderate | Duloxetine | |

| Moderate to potent | Bupropion | |

| Potent | Fluoxetine, haloperidol, paroxetine | |

| Dose-dependent | Sertraline | |

| 3A4 inducer | Potent | Carbamazepine |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Mild | Sertraline |

| Mild to moderate | Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | |

| Source: References 1,2 | ||

Table 2

Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes inhibiting and inducing opiate metabolism

| Isoenzyme | Opiates |

|---|---|

| 2B6 inducer | Methadone |

| 2B6 inhibitors | Meperidine, methadone |

| 2D6 inhibitors | Codeine (may involve loss of efficacy as well as toxicity), methadone, tramadol (may involve loss of efficacy) |

| 3A4 inducer | Meperidine, methadone |

| 3A4 inhibitors | Fentanyl, oxycodone, meperidine, methadone |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Other considerations

In addition to pharmacokinetic interactions, it is important to consider synergistic effects of some opiates and psychotropics. Examples include:

- additive effect on respiratory depression by benzodiazepines and opiates

- increased risk of serotonin syndrome and seizure when using tramadol with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants

- additive prolongation of the QTc interval by methadone when used with psychotropics known to prolong the QTc, such as ziprasidone.9,17,20

Careful attention to these interactions and collaboration among providers can ensure the best outcome for our patients. In Mr. G’s case, collaboration with his internist would be in order, particularly if antidepressant choices are limited. In consultation with the psychiatrist, the internist might choose another opiate to treat Mr. G’s pain that would not interact with fluoxetine. If Mr. G and his physician have struggled to manage his pain and if he is stable on the current regimen, selecting a different antidepressant may be warranted.

Related Resources

- Indiana University School of Medicine drug interactions: cytochrome P450 drug interaction table. http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.asp.

- Ferrando SJ, Levenson JL, Owen JA, eds. Clinical manual of psychopharmacology in the medically ill. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2010.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fentanyl • Duragesic, Actiq

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Hydrocodone • Lortab, Vicodin, others

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Meperidine • Demerol

- Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Morphine • Avinza, Duramorph, others

- Oxycodone • OxyContin, Roxicodone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tramadol • Ultram

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:464-494.

2. Faucette SR, Wang H, Hamilton GA. Regulation of CYP2B6 in primary human hepatocytes by prototypical inducers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(3):348-358.

3. Smith HS. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:613-624.

4. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of morphine codeine, and their derivatives: theory and clinical reality, part II. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:515-520.

5. Grönlund J, Saari TI, Hagelberg NM, et al. Exposure to oral oxycodone is increased by concomitant inhibition of CYP2D6 and 3A4 pathways, but not by inhibition of CYP2D6 alone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:78-87.

6. Leavitt SB. Methadone-drug* interactions. (*medications illicit drugs, and other substances). 3rd ed. Mundelein, IL: Addiction Treatment Forum; 2005.

7. Pérez de los Cobos J, Siñol N, Trujols J, et al. Association of CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer genotype with deficient patient satisfaction regarding methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:190-194.

8. Kristensen K, Christensen CB, Christrup LL. The mu1 mu2, delta, kappa opioid receptor binding profiles of methadone stereoisomers and morphine. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL45-50.

9. Armstrong SC, Wynn GH, Sandson NB. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of synthetic opiate analgesics. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:169-176.

10. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

11. Ramírez J, Innocenti F, Schuetz EG, et al. CYP2B6, CYP3A4, and CYP2C19 are responsible for the in vitro N-demethylation of meperidine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:930-936.

12. Kaiko RF, Foley KM, Grabinski PY, et al. Central nervous system excitatory effects of meperidine in cancer patients. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:180-185.

13. Chalverus C. Clinically important meperidine toxicities. Journal of Pharmaceutical Care in Pain and Symptom Control. 2001;9:37-55.

14. Beckwith MC, Fox ER, Chandramouli J. Removing meperidine from the health-system formulary—frequently asked questions. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2002;16:45-59.

15. Foster A, Mobley E, Wang Z. Complicated pain management in a CYP450 2D6 poor metabolizer. Pain Pract. 2007;7:352-356.

16. Susce MT, Murray-Carmichael E, de Leon J. Response to hydrocodone codeine and oxycodone in a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1356-1358.

17. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Tramadol: seizures serotonin syndrome, and coadministered antidepressants. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6:17-21.

18. Laugesen S, Enggaard TP, Pedersen RS, et al. Paroxetine, a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, diminishes the stereoselective O-demethylation and reduces the hypoalgesic effect of tramadol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:312-323.

19. Duragesic [package insert]. Raritan NJ: Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

20. Caplehorn JR, Drummer OH. Fatal methadone toxicity: signs and circumstances and the role of benzodiazepines. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:358-362;discussion 362–363.

1. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:464-494.

2. Faucette SR, Wang H, Hamilton GA. Regulation of CYP2B6 in primary human hepatocytes by prototypical inducers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(3):348-358.

3. Smith HS. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:613-624.

4. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of morphine codeine, and their derivatives: theory and clinical reality, part II. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:515-520.

5. Grönlund J, Saari TI, Hagelberg NM, et al. Exposure to oral oxycodone is increased by concomitant inhibition of CYP2D6 and 3A4 pathways, but not by inhibition of CYP2D6 alone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:78-87.

6. Leavitt SB. Methadone-drug* interactions. (*medications illicit drugs, and other substances). 3rd ed. Mundelein, IL: Addiction Treatment Forum; 2005.

7. Pérez de los Cobos J, Siñol N, Trujols J, et al. Association of CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer genotype with deficient patient satisfaction regarding methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:190-194.

8. Kristensen K, Christensen CB, Christrup LL. The mu1 mu2, delta, kappa opioid receptor binding profiles of methadone stereoisomers and morphine. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL45-50.

9. Armstrong SC, Wynn GH, Sandson NB. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of synthetic opiate analgesics. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:169-176.

10. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

11. Ramírez J, Innocenti F, Schuetz EG, et al. CYP2B6, CYP3A4, and CYP2C19 are responsible for the in vitro N-demethylation of meperidine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:930-936.

12. Kaiko RF, Foley KM, Grabinski PY, et al. Central nervous system excitatory effects of meperidine in cancer patients. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:180-185.

13. Chalverus C. Clinically important meperidine toxicities. Journal of Pharmaceutical Care in Pain and Symptom Control. 2001;9:37-55.

14. Beckwith MC, Fox ER, Chandramouli J. Removing meperidine from the health-system formulary—frequently asked questions. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2002;16:45-59.

15. Foster A, Mobley E, Wang Z. Complicated pain management in a CYP450 2D6 poor metabolizer. Pain Pract. 2007;7:352-356.

16. Susce MT, Murray-Carmichael E, de Leon J. Response to hydrocodone codeine and oxycodone in a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1356-1358.

17. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Tramadol: seizures serotonin syndrome, and coadministered antidepressants. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6:17-21.

18. Laugesen S, Enggaard TP, Pedersen RS, et al. Paroxetine, a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, diminishes the stereoselective O-demethylation and reduces the hypoalgesic effect of tramadol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:312-323.

19. Duragesic [package insert]. Raritan NJ: Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

20. Caplehorn JR, Drummer OH. Fatal methadone toxicity: signs and circumstances and the role of benzodiazepines. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:358-362;discussion 362–363.

Evaluating medication outcomes: 3 key questions

Post hoc ergo propter hoc—”after this, therefore because of this”—suggests that 2 distinct events linked temporally are related causally. Clinicians often apply this dictum when monitoring effects of psychotropics. Because of stigma associated with psychiatric medications, and the readiness with which many practitioners blame them for unexpected results, it is important to develop a rational approach to evaluating outcomes—particularly adverse ones—after administering psychotropic agents.

Consider a geriatric patient admitted to the hospital for a urinary tract infection. He becomes verbally aggressive and is given IV haloperidol. Five minutes later he strikes a nurse and receives lorazepam. Twenty minutes later, he is lying calmly in his bed. The nursing staff and primary team conclude that the patient’s agitation worsened because of the antipsychotic and responded to the benzodiazepine; the physician documents in the patient’s chart that he had an adverse reaction to haloperidol.

In light of what we know about psychotropic medications’ mechanism of action, a more plausible explanation is that whatever caused the patient to become agitated (delirium) resulted in physical aggression. Haloperidol simply did not have enough time to exert its effect before the patient hit the nurse. It also would be wrong to automatically conclude that the last intervention (a benzodiazepine) produced the beneficial outcome. Was it the lorazepam, the haloperidol finally “kicking in,” or a combination of both? Perhaps it was none of the above but rather a worsening infection or irregular waxing and waning of delirium that was the culprit.

To avoid incorrectly attributing negative outcomes to medications, we suggest asking yourself 3 questions:

1. Is the negative outcome a potential consequence of the underlying condition?

Consider the possibility that the medication did not cause the adverse event but merely failed to adequately treat the underlying problem. A teenager who attempts suicide 2 weeks after starting an antidepressant may be exhibiting symptoms related to depression rather than behavior caused by the medication.

2. Are other medical conditions or medications responsible for the negative outcome?

Weigh the relative likelihood that these factors are contributing to your patient’s presentation. In a surgical patient who is overly somnolent after receiving an anxiolytic, consider the possibility that a narcotic or worsening hypoxia are contributing to her somnolence.

3. Is the negative outcome likely to have occurred spontaneously?

Consider the possibility of coincidence. Lithium might not be causing declining renal function in an older patient. A dosing adjustment based on the patient’s current renal function may be a better harm-reduction strategy than discontinuing a potentially useful medication.

Careful evaluation of these potential confounding factors will greatly reduce the likelihood of falsely identifying psychotropic medications as responsible for negative outcomes. After this, but not always because of this.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc—”after this, therefore because of this”—suggests that 2 distinct events linked temporally are related causally. Clinicians often apply this dictum when monitoring effects of psychotropics. Because of stigma associated with psychiatric medications, and the readiness with which many practitioners blame them for unexpected results, it is important to develop a rational approach to evaluating outcomes—particularly adverse ones—after administering psychotropic agents.

Consider a geriatric patient admitted to the hospital for a urinary tract infection. He becomes verbally aggressive and is given IV haloperidol. Five minutes later he strikes a nurse and receives lorazepam. Twenty minutes later, he is lying calmly in his bed. The nursing staff and primary team conclude that the patient’s agitation worsened because of the antipsychotic and responded to the benzodiazepine; the physician documents in the patient’s chart that he had an adverse reaction to haloperidol.

In light of what we know about psychotropic medications’ mechanism of action, a more plausible explanation is that whatever caused the patient to become agitated (delirium) resulted in physical aggression. Haloperidol simply did not have enough time to exert its effect before the patient hit the nurse. It also would be wrong to automatically conclude that the last intervention (a benzodiazepine) produced the beneficial outcome. Was it the lorazepam, the haloperidol finally “kicking in,” or a combination of both? Perhaps it was none of the above but rather a worsening infection or irregular waxing and waning of delirium that was the culprit.

To avoid incorrectly attributing negative outcomes to medications, we suggest asking yourself 3 questions:

1. Is the negative outcome a potential consequence of the underlying condition?

Consider the possibility that the medication did not cause the adverse event but merely failed to adequately treat the underlying problem. A teenager who attempts suicide 2 weeks after starting an antidepressant may be exhibiting symptoms related to depression rather than behavior caused by the medication.

2. Are other medical conditions or medications responsible for the negative outcome?

Weigh the relative likelihood that these factors are contributing to your patient’s presentation. In a surgical patient who is overly somnolent after receiving an anxiolytic, consider the possibility that a narcotic or worsening hypoxia are contributing to her somnolence.

3. Is the negative outcome likely to have occurred spontaneously?

Consider the possibility of coincidence. Lithium might not be causing declining renal function in an older patient. A dosing adjustment based on the patient’s current renal function may be a better harm-reduction strategy than discontinuing a potentially useful medication.

Careful evaluation of these potential confounding factors will greatly reduce the likelihood of falsely identifying psychotropic medications as responsible for negative outcomes. After this, but not always because of this.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc—”after this, therefore because of this”—suggests that 2 distinct events linked temporally are related causally. Clinicians often apply this dictum when monitoring effects of psychotropics. Because of stigma associated with psychiatric medications, and the readiness with which many practitioners blame them for unexpected results, it is important to develop a rational approach to evaluating outcomes—particularly adverse ones—after administering psychotropic agents.

Consider a geriatric patient admitted to the hospital for a urinary tract infection. He becomes verbally aggressive and is given IV haloperidol. Five minutes later he strikes a nurse and receives lorazepam. Twenty minutes later, he is lying calmly in his bed. The nursing staff and primary team conclude that the patient’s agitation worsened because of the antipsychotic and responded to the benzodiazepine; the physician documents in the patient’s chart that he had an adverse reaction to haloperidol.

In light of what we know about psychotropic medications’ mechanism of action, a more plausible explanation is that whatever caused the patient to become agitated (delirium) resulted in physical aggression. Haloperidol simply did not have enough time to exert its effect before the patient hit the nurse. It also would be wrong to automatically conclude that the last intervention (a benzodiazepine) produced the beneficial outcome. Was it the lorazepam, the haloperidol finally “kicking in,” or a combination of both? Perhaps it was none of the above but rather a worsening infection or irregular waxing and waning of delirium that was the culprit.

To avoid incorrectly attributing negative outcomes to medications, we suggest asking yourself 3 questions:

1. Is the negative outcome a potential consequence of the underlying condition?

Consider the possibility that the medication did not cause the adverse event but merely failed to adequately treat the underlying problem. A teenager who attempts suicide 2 weeks after starting an antidepressant may be exhibiting symptoms related to depression rather than behavior caused by the medication.

2. Are other medical conditions or medications responsible for the negative outcome?

Weigh the relative likelihood that these factors are contributing to your patient’s presentation. In a surgical patient who is overly somnolent after receiving an anxiolytic, consider the possibility that a narcotic or worsening hypoxia are contributing to her somnolence.

3. Is the negative outcome likely to have occurred spontaneously?

Consider the possibility of coincidence. Lithium might not be causing declining renal function in an older patient. A dosing adjustment based on the patient’s current renal function may be a better harm-reduction strategy than discontinuing a potentially useful medication.

Careful evaluation of these potential confounding factors will greatly reduce the likelihood of falsely identifying psychotropic medications as responsible for negative outcomes. After this, but not always because of this.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Is your depressed postpartum patient bipolar?

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Many individuals think of postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder within 4 weeks of delivery; however, postpartum depressive symptoms also can occur in the context of bipolar I disorder (BD I) or bipolar II disorder (BD II). Despite the high prevalence of postpartum hypomania (9% to 20%), clinicians often fail to screen for symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 Determining if your patient’s postpartum depressive episode is caused by BD is essential when formulating an appropriate treatment plan that protects the mother and child.

Postpartum depression literature offers little guidance on the recognition and management of postpartum bipolar disorder.2 For example, there is scant evidence on pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum bipolar depression, and no studies have evaluated the use of screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to detect bipolar disorder.

Misdiagnosis of postpartum depression is more likely in cases of subtle bipolarity—BD II and BD not otherwise specified—than in BD I because:3

- physicians often fail to ask postpartum patients about hypomanic symptoms such as feelings of elation, being overly talkative, racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep

- DSM-IV-TR does not recognize hypomania with a postpartum onset specifier

- hypomania symptoms overlap normal feelings of elation and sleep disturbance following childbirth.

Clues to postpartum bipolar disorder include:

- hypomania: persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- depression onset immediately after delivery

- atypical features such as hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and increased appetite

- racing thoughts

- concomitant psychotic symptoms

- history of BD in a first-degree relative

- antidepressants “misadventures” (rapid response; loss of response; induction of mania, hypomania, or depressive mixed episodes; and poor response).

Treatment strategies

Avoid antidepressants. Bipolar depression does not respond to antidepressants as well as unipolar depression. Moreover, antidepressants can induce mania, hypomania, or mixed states, and can increase mood cycle frequency.

Administer mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine, or atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine.

In breast-feeding women the benefits of treatment should be balanced carefully against the risk of infant exposure to medications. Lamotrigine should be used cautiously because of concerns of skin rash and higher-than-expected drug levels in the infant. In light of recent data showing no significant adverse clinical or behavioral effects in infants, breast-feeding while taking lithium should be considered in carefully selected women. The preliminary evidence supporting the use of quetiapine during breast-feeding appears promising; however, data on the safety of atypical antipsychotics in lactating women are limited.

Promote sleep. Sleep disruption can be a symptom of as well as a trigger for postpartum bipolar depression. In women with BD, the benefits of breast-feeding should be balanced carefully against the potential for the deleterious effects of sleep deprivation in triggering mood episodes. Women should consider using a breast pump allowing others to assist with feeding or supplementing breast milk with formula to help get uninterrupted sleep.3

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

1. Heron J, Craddock N, Jones I. Postnatal euphoria: are ‘the highs’ an indicator of bipolarity? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:103-110.

2. Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, et al. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:742-747.

3. Sharma V, Burt VK, Ritchie, HL. Bipolar II postpartum depression: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1217-1221.

The ABCs of estimating adherence to antipsychotics

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

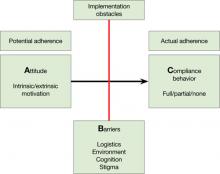

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

Should you prescribe medications for family and friends?

Dear Dr. Mossman:

On a recent golf outing, my buddy Mike told me about his trouble staying “focused” while studying for his grad school exams. He asked me to write him a prescription for methylphenidate, which he had taken in high school and college. I want to help Mike, but I’m worried about my liability if something goes wrong. What should I do?—Submitted by “Dr. C”

Doctors learn early in their careers that family, friends, or coworkers often seek informal medical advice and ask for prescriptions. Also, doctors commonly diagnose and medicate themselves rather than seek care from other professionals.1,2

In this article, we use the phrase “casual prescribing” to describe activities related to prescribing drugs for individuals such as Mike, a friend who has sought medication outside Dr. C’s customary practice setting. Despite having good intentions, you’re probably increasing your malpractice liability whenever you casually prescribe medication. Even more serious, if you casually prescribe controlled substances (eg, stimulants), you risk investigation and potential sanction by your state medical licensing agency.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

To decide whether, how, and when you may prescribe drugs for yourself, family members, colleagues, or friends, you need to:

- anticipate being asked to casually prescribe

- understand the emotions and forces that drive casual prescribing

- know your state medical board’s rules and regulations

- be prepared with an appropriate response.

After we explore these points, we’ll consider what Dr. C might do.

A common request

People often seek medical advice outside doctors’ offices. Playing a sport together, sitting on an airplane, or sharing other social activities strips away the veneer of formality, lets people relax, makes doctors seem more approachable, and allows medical concerns to come forth more easily.3

Access to medical care is a problem for lay people and doctors alike. In many locales, simply getting an appointment with a primary care physician or psychiatrist is difficult.4,5 Navigating health insurance rules and referral lists is frustrating. When people find a provider, they may feel guilty about taking a slot from someone else. Job expectations or a tough economy can make employees reluctant to take time off work6,7 or concerned that they’ll miss productivity goals because of illness.1