User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Off-label prescribing: 7 steps for safer, more effective treatment

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene

Dr. Kramer reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. McCall receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, and Wyeth, is an advisor to King Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor, and is a speaker for GlaxoSmtihKline, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

1. Lowe-Ponsford FL, Baldwin DS. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull 2000;24(11):415-17.

2. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000;283(8):1025-30.

3. Kelly DL, Love RC, Mackowick M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14(1):75-85.

4. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M. From clinical trials to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care 2001;39(3):302-8.

5. Fountoulakis KN, Nimatoudis I, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G. Off-label indications for atypical antipsychotics: A systematic review. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;3(1):4.-

6. Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al. Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(3):395-404.

1. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent. Food Drug Law J 1998;53:71-104.

8. Hepper F, Fellow-Smith E. Off-label prescribing in a community child and adolescent mental health service: Implications for information giving and informed consent. Clin Manag 2005;13(1):29-33.

9. O’Reilly JD, Dalal A. Off-label or out of bounds? Prescriber and marketer liability for unapproved uses of FDA-approved drugs. Ann Health Law 2003;12:295-324.

10. Ware JC, Pittard JT. Increased deep sleep after trazodone use: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy young adults. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:18-22.

11. McCall WV. Use of off-label medications in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1(4):e494-5.

12. Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, Martin BC. An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14(9):629-38.

13. Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm 2003;9(6):559-68.

14. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of valproate: extent of inpatient use in the New York State Office of Mental Health. Psychiatr Q 1998;69(4):283-300.

15. De Leon O. Antiepileptic drugs for the acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2001;9(5):209-22.

16. Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, et al. Double-blind, placebocontrolled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol postwithdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):377-83.

17. Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):195-205.

18. Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35(3):187-91.

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene

Dr. Kramer reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. McCall receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, and Wyeth, is an advisor to King Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor, and is a speaker for GlaxoSmtihKline, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene

Dr. Kramer reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. McCall receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, and Wyeth, is an advisor to King Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor, and is a speaker for GlaxoSmtihKline, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

1. Lowe-Ponsford FL, Baldwin DS. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull 2000;24(11):415-17.

2. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000;283(8):1025-30.

3. Kelly DL, Love RC, Mackowick M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14(1):75-85.

4. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M. From clinical trials to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care 2001;39(3):302-8.

5. Fountoulakis KN, Nimatoudis I, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G. Off-label indications for atypical antipsychotics: A systematic review. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;3(1):4.-

6. Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al. Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(3):395-404.

1. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent. Food Drug Law J 1998;53:71-104.

8. Hepper F, Fellow-Smith E. Off-label prescribing in a community child and adolescent mental health service: Implications for information giving and informed consent. Clin Manag 2005;13(1):29-33.

9. O’Reilly JD, Dalal A. Off-label or out of bounds? Prescriber and marketer liability for unapproved uses of FDA-approved drugs. Ann Health Law 2003;12:295-324.

10. Ware JC, Pittard JT. Increased deep sleep after trazodone use: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy young adults. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:18-22.

11. McCall WV. Use of off-label medications in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1(4):e494-5.

12. Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, Martin BC. An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14(9):629-38.

13. Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm 2003;9(6):559-68.

14. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of valproate: extent of inpatient use in the New York State Office of Mental Health. Psychiatr Q 1998;69(4):283-300.

15. De Leon O. Antiepileptic drugs for the acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2001;9(5):209-22.

16. Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, et al. Double-blind, placebocontrolled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol postwithdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):377-83.

17. Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):195-205.

18. Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35(3):187-91.

1. Lowe-Ponsford FL, Baldwin DS. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull 2000;24(11):415-17.

2. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000;283(8):1025-30.

3. Kelly DL, Love RC, Mackowick M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14(1):75-85.

4. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M. From clinical trials to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care 2001;39(3):302-8.

5. Fountoulakis KN, Nimatoudis I, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G. Off-label indications for atypical antipsychotics: A systematic review. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;3(1):4.-

6. Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al. Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(3):395-404.

1. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent. Food Drug Law J 1998;53:71-104.

8. Hepper F, Fellow-Smith E. Off-label prescribing in a community child and adolescent mental health service: Implications for information giving and informed consent. Clin Manag 2005;13(1):29-33.

9. O’Reilly JD, Dalal A. Off-label or out of bounds? Prescriber and marketer liability for unapproved uses of FDA-approved drugs. Ann Health Law 2003;12:295-324.

10. Ware JC, Pittard JT. Increased deep sleep after trazodone use: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy young adults. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:18-22.

11. McCall WV. Use of off-label medications in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1(4):e494-5.

12. Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, Martin BC. An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14(9):629-38.

13. Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm 2003;9(6):559-68.

14. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of valproate: extent of inpatient use in the New York State Office of Mental Health. Psychiatr Q 1998;69(4):283-300.

15. De Leon O. Antiepileptic drugs for the acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2001;9(5):209-22.

16. Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, et al. Double-blind, placebocontrolled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol postwithdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):377-83.

17. Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):195-205.

18. Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35(3):187-91.

Intramuscular naltrexone

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

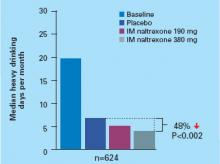

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.

Oral board jitters? Try these rehearsal tips

Many candidates become anxious before and during the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) part II oral exam, especially if they failed before. As many as 50% of candidates fail the part II oral exam on the first try, and those who fail a second time risk failing several times.1

Studying more and worrying less can improve your chance of passing, whether it’s your first time taking the test or after an initial failure. You may also perform better if you begin the certification process promptly after residency training.2 By fitting rehearsal opportunities into a busy schedule, you—or residents you supervise—can prepare for the exam’s oral portion and reduce test-taking anxiety.

Form a study group. Take turns performing oral board-type interviews with other candidates. Give and receive informal feedback while you practice.

Conduct many mock board interviews. Mock interviews with volunteer patients who have given written or verbal consent are the most-thorough form of exam preparation, especially when supervised by psychiatrists who have been examiners. Try to do as many as your schedule permits.

Practice on your patients. When you see a new patient, keep the board process in mind and try to do a 30-minute interview. Imagine you are in front of the examiners.

Dictate evaluations as if presenting to examiners. Tape-recording dictations allows you to review your presentation later and critique yourself.

Practice for the exam’s video portion. Because this part is commonly overlooked, many candidates pass the live interview but fail the video portion.

For the video portion, you are asked to watch a short video of a patient interview and present a case based on information from the video. You can purchase sample videos from commercial test preparation organizations, which often advertise in American Psychiatric Association newsletters.

Videotape yourself interviewing and presenting the case. Reviewing the videos can help you identify and correct body language problems so that you convey warmth, empathy, and confidence. You can videotape an interview after obtaining written consent from the patient. If no patients agree, videotape yourself giving the case presentation only.

Practice in inpatient, outpatient, and office settings. This gives you a chance to practice interviewing patients with a variety of psychiatric conditions.

These tips can help you make the 30-minute interview and presentation second nature, reduce exam anxiety, and increase your chance of passing.

1. Moran M. Project helps candidate succeed on ABPN exam. Psychiatr News 2005;40(17):22.-

2. Juul D, Scully JH, Jr, Scheiber SC. Achieving board certification in psychiatry: a cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(3):563-5.

Dr. Khawaja is staff psychiatrist, VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, and has recently been appointed assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Minnesota.

Many candidates become anxious before and during the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) part II oral exam, especially if they failed before. As many as 50% of candidates fail the part II oral exam on the first try, and those who fail a second time risk failing several times.1

Studying more and worrying less can improve your chance of passing, whether it’s your first time taking the test or after an initial failure. You may also perform better if you begin the certification process promptly after residency training.2 By fitting rehearsal opportunities into a busy schedule, you—or residents you supervise—can prepare for the exam’s oral portion and reduce test-taking anxiety.

Form a study group. Take turns performing oral board-type interviews with other candidates. Give and receive informal feedback while you practice.

Conduct many mock board interviews. Mock interviews with volunteer patients who have given written or verbal consent are the most-thorough form of exam preparation, especially when supervised by psychiatrists who have been examiners. Try to do as many as your schedule permits.

Practice on your patients. When you see a new patient, keep the board process in mind and try to do a 30-minute interview. Imagine you are in front of the examiners.

Dictate evaluations as if presenting to examiners. Tape-recording dictations allows you to review your presentation later and critique yourself.

Practice for the exam’s video portion. Because this part is commonly overlooked, many candidates pass the live interview but fail the video portion.

For the video portion, you are asked to watch a short video of a patient interview and present a case based on information from the video. You can purchase sample videos from commercial test preparation organizations, which often advertise in American Psychiatric Association newsletters.

Videotape yourself interviewing and presenting the case. Reviewing the videos can help you identify and correct body language problems so that you convey warmth, empathy, and confidence. You can videotape an interview after obtaining written consent from the patient. If no patients agree, videotape yourself giving the case presentation only.

Practice in inpatient, outpatient, and office settings. This gives you a chance to practice interviewing patients with a variety of psychiatric conditions.

These tips can help you make the 30-minute interview and presentation second nature, reduce exam anxiety, and increase your chance of passing.

Many candidates become anxious before and during the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) part II oral exam, especially if they failed before. As many as 50% of candidates fail the part II oral exam on the first try, and those who fail a second time risk failing several times.1

Studying more and worrying less can improve your chance of passing, whether it’s your first time taking the test or after an initial failure. You may also perform better if you begin the certification process promptly after residency training.2 By fitting rehearsal opportunities into a busy schedule, you—or residents you supervise—can prepare for the exam’s oral portion and reduce test-taking anxiety.

Form a study group. Take turns performing oral board-type interviews with other candidates. Give and receive informal feedback while you practice.

Conduct many mock board interviews. Mock interviews with volunteer patients who have given written or verbal consent are the most-thorough form of exam preparation, especially when supervised by psychiatrists who have been examiners. Try to do as many as your schedule permits.

Practice on your patients. When you see a new patient, keep the board process in mind and try to do a 30-minute interview. Imagine you are in front of the examiners.

Dictate evaluations as if presenting to examiners. Tape-recording dictations allows you to review your presentation later and critique yourself.

Practice for the exam’s video portion. Because this part is commonly overlooked, many candidates pass the live interview but fail the video portion.

For the video portion, you are asked to watch a short video of a patient interview and present a case based on information from the video. You can purchase sample videos from commercial test preparation organizations, which often advertise in American Psychiatric Association newsletters.

Videotape yourself interviewing and presenting the case. Reviewing the videos can help you identify and correct body language problems so that you convey warmth, empathy, and confidence. You can videotape an interview after obtaining written consent from the patient. If no patients agree, videotape yourself giving the case presentation only.

Practice in inpatient, outpatient, and office settings. This gives you a chance to practice interviewing patients with a variety of psychiatric conditions.

These tips can help you make the 30-minute interview and presentation second nature, reduce exam anxiety, and increase your chance of passing.

1. Moran M. Project helps candidate succeed on ABPN exam. Psychiatr News 2005;40(17):22.-

2. Juul D, Scully JH, Jr, Scheiber SC. Achieving board certification in psychiatry: a cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(3):563-5.

Dr. Khawaja is staff psychiatrist, VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, and has recently been appointed assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Minnesota.

1. Moran M. Project helps candidate succeed on ABPN exam. Psychiatr News 2005;40(17):22.-

2. Juul D, Scully JH, Jr, Scheiber SC. Achieving board certification in psychiatry: a cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(3):563-5.

Dr. Khawaja is staff psychiatrist, VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, and has recently been appointed assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Minnesota.

4 ECT electrode options: Which is best for your patient?

Patients with severe mood disorders tend to respond more favorably to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) when electrode placement has been individually selected for them. Yet most ECT practitioners use one electrode placement—bitemporal—for all patients (Figure 1).1

While standard bitemporal ECT is generally most effective, it also produces the greatest degree of disorientation, which can prolong a hospital stay or increase the need for supportive care.

Bifrontal ECT (Figure 2, part A) has been shown as efficacious as bitemporal placement while producing less disorientation.2 I have found left anterior right temporal (LART) placement (Figure 2, part B), to be equally effective with fewer side effects.

Figure 1 Bitemporal electrode placement

This generally effective and most widely used electrode placement causes the greatest post-ECT disorientation.

Figure 2a Bifrontal placement

Figure 2b Left anterior right temporal (LART) placement

Figure 2c Right unilateral placement

Side Effects of Lart

Side effects such as disorientation and loss of self-care should be less severe and prevalent with LART than with other bilateral placements because:

- the left electrode is far anterior to the temporal lobe, rather than close to it as in bitemporal placement.

- LART avoids symmetrical effect, which can block compensation by the opposite hemisphere.

Hypothetically, some patients might not respond to bifrontal or LART placement but respond to bitemporal ECT, although no such instances have been reported in the literature. By contrast, response to bitemporal ECT after failure of right unilateral ECT (Figure 2, part C) is well known; indeed, studies of unilateral ECT typically include provisions for changing to bitemporal ECT. Moreover, early relapse (within 2 months) appears more frequently after unilateral ECT.

Patient Selection and Dosing

Low-dose right unilateral ECT should suffice in men younger than age 40 because they usually develop vigorous seizures without substantial disorientation afterward. Low dose in unilateral ECT is millicoulomb (mC) charge less than 4 times the patient’s age in years.

In patients who do not develop vigorous seizures—a common problem in men age >65—unilateral ECT is more likely to produce disappointing results than other ECT configurations. Moreover, severe confusion from unilateral ECT is not rare in patients older than 65. Unilateral ECT should not be a routine choice for this age group.

Stimulus dosing in effect alters electrode placement. High dose spreads the stimulus as if the electrodes were much larger. As a result, all forms of placement at high stimulus doses more closely resemble bitemporal ECT, increasing side effect risk and negating differences among the forms of electrode placement. In fact side effects from unilateral ECT at high stimulus doses approximate those of bitemporal ECT.3 Right unilateral ECT in this context has no apparent advantages.

When intervention with ECT is urgently needed—such as for patients with severe catatonia, inanition, or active suicidality—efficacy is paramount and bitemporal ECT is the usual choice. Typical starting dose in mC is 2.5 times age.

In nonemergency circumstances, my experience with LART placement has resulted in strong enthusiasm for ECT by nursing staff and patients who recognize improvement without noticeable side effects.

Clinicians who use ECT should obtain first-hand experience with all four methods of electrode placement. In addition, use of brief-pulse rather than sine-wave stimuli is as important to minimizing side effects as electrode placement.

Disclosure

Dr. Swartz has equity interests in Somatics, LLC, a manufacturer of ECT instruments.

1. Prudic J, Olfson M, Sackeim HA. Electro-convulsive therapy practices in the community. Psychol Med 2001;31:929-34.

2. Swartz CM, Nelson AI. Rational electroconvulsive therapy electrode placement. Psychiatry 2005 2005;2(7):37-43.Available at: http://psychiatrymmc.com/displayArticle.cfm?articleID=article14. Accessed February 6, 2006.

3. McCall WV, Dunn A, Rosenquist PB, Hughes D. Markedly suprathreshold right unilateral ECT versus minimally suprathreshold bilateral ECT: antidepressant and memory effects. J ECT 2002;3:126-9.

Dr. Swartz is professor and chief, division of psychiatric research, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield, IL.

Patients with severe mood disorders tend to respond more favorably to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) when electrode placement has been individually selected for them. Yet most ECT practitioners use one electrode placement—bitemporal—for all patients (Figure 1).1

While standard bitemporal ECT is generally most effective, it also produces the greatest degree of disorientation, which can prolong a hospital stay or increase the need for supportive care.

Bifrontal ECT (Figure 2, part A) has been shown as efficacious as bitemporal placement while producing less disorientation.2 I have found left anterior right temporal (LART) placement (Figure 2, part B), to be equally effective with fewer side effects.

Figure 1 Bitemporal electrode placement

This generally effective and most widely used electrode placement causes the greatest post-ECT disorientation.

Figure 2a Bifrontal placement

Figure 2b Left anterior right temporal (LART) placement

Figure 2c Right unilateral placement

Side Effects of Lart

Side effects such as disorientation and loss of self-care should be less severe and prevalent with LART than with other bilateral placements because:

- the left electrode is far anterior to the temporal lobe, rather than close to it as in bitemporal placement.

- LART avoids symmetrical effect, which can block compensation by the opposite hemisphere.

Hypothetically, some patients might not respond to bifrontal or LART placement but respond to bitemporal ECT, although no such instances have been reported in the literature. By contrast, response to bitemporal ECT after failure of right unilateral ECT (Figure 2, part C) is well known; indeed, studies of unilateral ECT typically include provisions for changing to bitemporal ECT. Moreover, early relapse (within 2 months) appears more frequently after unilateral ECT.

Patient Selection and Dosing

Low-dose right unilateral ECT should suffice in men younger than age 40 because they usually develop vigorous seizures without substantial disorientation afterward. Low dose in unilateral ECT is millicoulomb (mC) charge less than 4 times the patient’s age in years.

In patients who do not develop vigorous seizures—a common problem in men age >65—unilateral ECT is more likely to produce disappointing results than other ECT configurations. Moreover, severe confusion from unilateral ECT is not rare in patients older than 65. Unilateral ECT should not be a routine choice for this age group.

Stimulus dosing in effect alters electrode placement. High dose spreads the stimulus as if the electrodes were much larger. As a result, all forms of placement at high stimulus doses more closely resemble bitemporal ECT, increasing side effect risk and negating differences among the forms of electrode placement. In fact side effects from unilateral ECT at high stimulus doses approximate those of bitemporal ECT.3 Right unilateral ECT in this context has no apparent advantages.

When intervention with ECT is urgently needed—such as for patients with severe catatonia, inanition, or active suicidality—efficacy is paramount and bitemporal ECT is the usual choice. Typical starting dose in mC is 2.5 times age.

In nonemergency circumstances, my experience with LART placement has resulted in strong enthusiasm for ECT by nursing staff and patients who recognize improvement without noticeable side effects.

Clinicians who use ECT should obtain first-hand experience with all four methods of electrode placement. In addition, use of brief-pulse rather than sine-wave stimuli is as important to minimizing side effects as electrode placement.

Disclosure

Dr. Swartz has equity interests in Somatics, LLC, a manufacturer of ECT instruments.

Patients with severe mood disorders tend to respond more favorably to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) when electrode placement has been individually selected for them. Yet most ECT practitioners use one electrode placement—bitemporal—for all patients (Figure 1).1

While standard bitemporal ECT is generally most effective, it also produces the greatest degree of disorientation, which can prolong a hospital stay or increase the need for supportive care.

Bifrontal ECT (Figure 2, part A) has been shown as efficacious as bitemporal placement while producing less disorientation.2 I have found left anterior right temporal (LART) placement (Figure 2, part B), to be equally effective with fewer side effects.

Figure 1 Bitemporal electrode placement

This generally effective and most widely used electrode placement causes the greatest post-ECT disorientation.

Figure 2a Bifrontal placement

Figure 2b Left anterior right temporal (LART) placement

Figure 2c Right unilateral placement

Side Effects of Lart

Side effects such as disorientation and loss of self-care should be less severe and prevalent with LART than with other bilateral placements because:

- the left electrode is far anterior to the temporal lobe, rather than close to it as in bitemporal placement.

- LART avoids symmetrical effect, which can block compensation by the opposite hemisphere.