User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Anxiety in children during a new administration; Why medical psychiatry is vital for my patients; And more

Anxiety in children during a new administration

Since the current administration took office, many children continue to grapple with the initial shock of the election results and the uncertainty of what the next 4 years will bring. In the days after the election, several patients sat in my office and spoke of intense feelings of sadness, anger, and worry. Their stress levels were elevated, and they searched desperately for refuge from the unknown. On the other side of the hospital, patients expressing suicidal ideation filed into the emergency room. A similar scene played out nationally when suicide prevention hotlines experienced a sharp increase in calls.

During this emotional time, it is critical to support our children. Some will be more affected than others. Children from immigrant backgrounds might be particularly fearful of what this means for them and their families. In the days after the election, a video surfaced from a middle school in Michigan featuring kids at lunch chanting, “Build the wall!”

Bullying also is a concern. Despite being a third-generation American, an 8-year-old boy woke up the day after the election confused and scared. One mother told me that a student confronted her 11-year-old son at school, yelling that the election outcome was a “good thing” and he should “go back to his country.” Like his mother, the 11-year-old was born in the United States.

Kids get their cues from the adults in their lives. Parents and teachers play an important role in modeling behavior and providing comfort. Adults need to support children and to do that properly they need make sure they have processed their own feelings. They do not need to be unrealistic or overly positive, but should offer hope and trust in our democratic system. With discussion, children should have ample opportunity to express how they feel. Psychiatrists can evaluate a child’s symptoms and presentation. Are current medications helping enough with the recent changes? Does a child need a medication adjustment or to be seen more often? Does he (she) need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation of suicidal ideation? As a psychiatrist, do you need to revisit the list of resources in the community and give children a crisis hotline number? Also consider referring a child to a psychotherapist if needed. Some schools offered counseling after the election. It is worthwhile to contact school officials if a student is struggling or could benefit from additional support.

Although many unknowns remain, 1 thing is certain: children will have more questions and we must be ready to answer.

Balkozar S. Adam, MD

Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

University of Missouri

Columbia, Missouri

Co-Editor

Missouri Psychiatry Newsletter

Jefferson City, Missouri

Two additional adjunctive therapies for mental health

I was excited to read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about adjunctive therapies for mental health disorders (Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider,

The article missed 2 important vitamins that play a crucial role in positive mental health treatment outcomes: folic acid and vitamin B12. In my practice, I have found up to 50% of my patients with depression have a vitamin B12 deficiency. After supplementation, these patients’ symptoms improve to the point that we often can reduce or eliminate medication. Folic acid deficiency has been found among individuals with depression and linked to poor response to treatment.1 Higher serum levels of homocysteine—a consequence of low folic acid levels—are linked to increased risk of developing depression later in life, as well as higher risk of cardiovascular disease.2,3 Folate also can be used for enhancing treatment response to antidepressants by increasing production of neurotransmitters.2

Another factor to consider is methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) variants. Approximately 20% of the population cannot methylate B vitamins because of a variation on the MTHFR gene.4,5 These patients are at increased risk for depression because they are unable to use B vitamins, which are essential in the synthesis of serotonin and dopamine. These patients do not respond to B12 and folate supplements. For these individuals, I recommend methylated products, which can be purchased online.

I have found these practices, as well as many of those listed in the editorial, are effective in treating depression and anxiety.

Lara Kain, PA-C, MPAS

Psychiatric Physician Assistant

Tidewater Psychotherapy Services

Virginia Beach, Virginia

References

1. Kaner G, Soylu M, Yüksel N, et al. Evaluation of nutritional status of patients with depression. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:521481. doi: 10.1155/2015/521481.

2. Seppälä J, Koponen H, Kautiainen H, et al. Association between vitamin B12 and melancholic depressive symptoms: a Finnish population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-145.

3. Petridou ET, Kousoulis AA, Michelakos T, et al. Folate and B12 serum levels in association with depression in the aged: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(9):965-973.

4. Lynch B. MTHFR mutations and the conditions they cause. MTHFR.Net. http://mthfr.net/mthfr-mutations-and-the-conditions-they-cause/2011/09/07. Accessed February 16, 2017.

5. Eszlari N, Kovacs D, Petschner P, et al. Distinct effects of folate pathway genes MTHFR and MTHFD1L on ruminative response style: a potential risk mechanism for depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(3):e745. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.19.

An honest perspective on Cannabis in therapy

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments” (From the

As a psychiatrist specializing in bipolar and psychotic disorders—as well as the founder and Board President of Doctors for Cannabis Regulation—I appreciate his reservations about the potential of Cannabis to trigger psychosis in vulnerable individuals. My reading of the literature is there is good evidence for marijuana as a trigger—not as a cause—of the disease. However, what is the evidence for hallucinogens?

Cannabis can have adverse effects on brain development, but it is not clear whether those effects are worse than those caused by alcohol. In the absence of any head-to-head studies, how can we proceed?

David L. Nathan, MD, DFAPA

Clinical Associate Professor

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Director of Continuing Medical Education

Princeton HealthCare System

Princeton, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

LSD can cause psychosis, paranoid delusions, and altered thinking in addition to vivid visual hallucinations in some individuals but not all, because vulnerability occurs on a spectrum. I postulate that the recently discovered inverse agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, pimavanserin (FDA-approved for visual hallucinations and delusions of Parkinson’s disease psychosis), might be effective for LSD psychosis because this hallucinogen has a strong binding affinity to the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.

Studies show that marijuana can induce apoptosis, which would adversely affect brain development. Patients with schizophrenia who abuse marijuana have a lower gray matter volume than those who do not abuse the drug, and both groups have lower gray matter volume than matched healthy controls. I strongly advise a pregnant woman against smoking marijuana because it could impair the fetus’s brain development.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Self-administering LSD: Solution or abuse

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not aware of any systematic data about self-prescribed use of microdoses of LSD to reduce anxiety and depression. Among persons with anxiety and depression who have not had access to psychiatric care, self-medicating with agents such as alcohol, stimulants, ketamine, or LSD is regarded as substance abuse. It also is questionable whether people can determine which microdose of LSD to use. Finally, most drugs of abuse are not “pure,” and many are laced with potentially harmful contaminants.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Why medical psychiatry is vital for my patients

Dr. Paul Summergrad’s guest editorial “Medical psychiatry: The skill of integrating medical and psychiatric care” (

For me, the most inspiring sentence in Dr. Summergrad’s editorial was, “It is incumbent on us to pursue the medical differential of patients when we think it is needed, even if other physicians disagree.” I believe that this describes our job as physicians who specialize in psychiatry. To have a clinician of Dr. Summergrad’s stature write this was inspiring because it goes to the core of what more of us should do.

Ruth Myers, MD

Psychiatrist

The Community Circle PLLC

Burnsville, Minnesota

Anxiety in children during a new administration

Since the current administration took office, many children continue to grapple with the initial shock of the election results and the uncertainty of what the next 4 years will bring. In the days after the election, several patients sat in my office and spoke of intense feelings of sadness, anger, and worry. Their stress levels were elevated, and they searched desperately for refuge from the unknown. On the other side of the hospital, patients expressing suicidal ideation filed into the emergency room. A similar scene played out nationally when suicide prevention hotlines experienced a sharp increase in calls.

During this emotional time, it is critical to support our children. Some will be more affected than others. Children from immigrant backgrounds might be particularly fearful of what this means for them and their families. In the days after the election, a video surfaced from a middle school in Michigan featuring kids at lunch chanting, “Build the wall!”

Bullying also is a concern. Despite being a third-generation American, an 8-year-old boy woke up the day after the election confused and scared. One mother told me that a student confronted her 11-year-old son at school, yelling that the election outcome was a “good thing” and he should “go back to his country.” Like his mother, the 11-year-old was born in the United States.

Kids get their cues from the adults in their lives. Parents and teachers play an important role in modeling behavior and providing comfort. Adults need to support children and to do that properly they need make sure they have processed their own feelings. They do not need to be unrealistic or overly positive, but should offer hope and trust in our democratic system. With discussion, children should have ample opportunity to express how they feel. Psychiatrists can evaluate a child’s symptoms and presentation. Are current medications helping enough with the recent changes? Does a child need a medication adjustment or to be seen more often? Does he (she) need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation of suicidal ideation? As a psychiatrist, do you need to revisit the list of resources in the community and give children a crisis hotline number? Also consider referring a child to a psychotherapist if needed. Some schools offered counseling after the election. It is worthwhile to contact school officials if a student is struggling or could benefit from additional support.

Although many unknowns remain, 1 thing is certain: children will have more questions and we must be ready to answer.

Balkozar S. Adam, MD

Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

University of Missouri

Columbia, Missouri

Co-Editor

Missouri Psychiatry Newsletter

Jefferson City, Missouri

Two additional adjunctive therapies for mental health

I was excited to read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about adjunctive therapies for mental health disorders (Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider,

The article missed 2 important vitamins that play a crucial role in positive mental health treatment outcomes: folic acid and vitamin B12. In my practice, I have found up to 50% of my patients with depression have a vitamin B12 deficiency. After supplementation, these patients’ symptoms improve to the point that we often can reduce or eliminate medication. Folic acid deficiency has been found among individuals with depression and linked to poor response to treatment.1 Higher serum levels of homocysteine—a consequence of low folic acid levels—are linked to increased risk of developing depression later in life, as well as higher risk of cardiovascular disease.2,3 Folate also can be used for enhancing treatment response to antidepressants by increasing production of neurotransmitters.2

Another factor to consider is methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) variants. Approximately 20% of the population cannot methylate B vitamins because of a variation on the MTHFR gene.4,5 These patients are at increased risk for depression because they are unable to use B vitamins, which are essential in the synthesis of serotonin and dopamine. These patients do not respond to B12 and folate supplements. For these individuals, I recommend methylated products, which can be purchased online.

I have found these practices, as well as many of those listed in the editorial, are effective in treating depression and anxiety.

Lara Kain, PA-C, MPAS

Psychiatric Physician Assistant

Tidewater Psychotherapy Services

Virginia Beach, Virginia

References

1. Kaner G, Soylu M, Yüksel N, et al. Evaluation of nutritional status of patients with depression. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:521481. doi: 10.1155/2015/521481.

2. Seppälä J, Koponen H, Kautiainen H, et al. Association between vitamin B12 and melancholic depressive symptoms: a Finnish population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-145.

3. Petridou ET, Kousoulis AA, Michelakos T, et al. Folate and B12 serum levels in association with depression in the aged: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(9):965-973.

4. Lynch B. MTHFR mutations and the conditions they cause. MTHFR.Net. http://mthfr.net/mthfr-mutations-and-the-conditions-they-cause/2011/09/07. Accessed February 16, 2017.

5. Eszlari N, Kovacs D, Petschner P, et al. Distinct effects of folate pathway genes MTHFR and MTHFD1L on ruminative response style: a potential risk mechanism for depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(3):e745. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.19.

An honest perspective on Cannabis in therapy

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments” (From the

As a psychiatrist specializing in bipolar and psychotic disorders—as well as the founder and Board President of Doctors for Cannabis Regulation—I appreciate his reservations about the potential of Cannabis to trigger psychosis in vulnerable individuals. My reading of the literature is there is good evidence for marijuana as a trigger—not as a cause—of the disease. However, what is the evidence for hallucinogens?

Cannabis can have adverse effects on brain development, but it is not clear whether those effects are worse than those caused by alcohol. In the absence of any head-to-head studies, how can we proceed?

David L. Nathan, MD, DFAPA

Clinical Associate Professor

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Director of Continuing Medical Education

Princeton HealthCare System

Princeton, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

LSD can cause psychosis, paranoid delusions, and altered thinking in addition to vivid visual hallucinations in some individuals but not all, because vulnerability occurs on a spectrum. I postulate that the recently discovered inverse agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, pimavanserin (FDA-approved for visual hallucinations and delusions of Parkinson’s disease psychosis), might be effective for LSD psychosis because this hallucinogen has a strong binding affinity to the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.

Studies show that marijuana can induce apoptosis, which would adversely affect brain development. Patients with schizophrenia who abuse marijuana have a lower gray matter volume than those who do not abuse the drug, and both groups have lower gray matter volume than matched healthy controls. I strongly advise a pregnant woman against smoking marijuana because it could impair the fetus’s brain development.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Self-administering LSD: Solution or abuse

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not aware of any systematic data about self-prescribed use of microdoses of LSD to reduce anxiety and depression. Among persons with anxiety and depression who have not had access to psychiatric care, self-medicating with agents such as alcohol, stimulants, ketamine, or LSD is regarded as substance abuse. It also is questionable whether people can determine which microdose of LSD to use. Finally, most drugs of abuse are not “pure,” and many are laced with potentially harmful contaminants.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Why medical psychiatry is vital for my patients

Dr. Paul Summergrad’s guest editorial “Medical psychiatry: The skill of integrating medical and psychiatric care” (

For me, the most inspiring sentence in Dr. Summergrad’s editorial was, “It is incumbent on us to pursue the medical differential of patients when we think it is needed, even if other physicians disagree.” I believe that this describes our job as physicians who specialize in psychiatry. To have a clinician of Dr. Summergrad’s stature write this was inspiring because it goes to the core of what more of us should do.

Ruth Myers, MD

Psychiatrist

The Community Circle PLLC

Burnsville, Minnesota

Anxiety in children during a new administration

Since the current administration took office, many children continue to grapple with the initial shock of the election results and the uncertainty of what the next 4 years will bring. In the days after the election, several patients sat in my office and spoke of intense feelings of sadness, anger, and worry. Their stress levels were elevated, and they searched desperately for refuge from the unknown. On the other side of the hospital, patients expressing suicidal ideation filed into the emergency room. A similar scene played out nationally when suicide prevention hotlines experienced a sharp increase in calls.

During this emotional time, it is critical to support our children. Some will be more affected than others. Children from immigrant backgrounds might be particularly fearful of what this means for them and their families. In the days after the election, a video surfaced from a middle school in Michigan featuring kids at lunch chanting, “Build the wall!”

Bullying also is a concern. Despite being a third-generation American, an 8-year-old boy woke up the day after the election confused and scared. One mother told me that a student confronted her 11-year-old son at school, yelling that the election outcome was a “good thing” and he should “go back to his country.” Like his mother, the 11-year-old was born in the United States.

Kids get their cues from the adults in their lives. Parents and teachers play an important role in modeling behavior and providing comfort. Adults need to support children and to do that properly they need make sure they have processed their own feelings. They do not need to be unrealistic or overly positive, but should offer hope and trust in our democratic system. With discussion, children should have ample opportunity to express how they feel. Psychiatrists can evaluate a child’s symptoms and presentation. Are current medications helping enough with the recent changes? Does a child need a medication adjustment or to be seen more often? Does he (she) need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation of suicidal ideation? As a psychiatrist, do you need to revisit the list of resources in the community and give children a crisis hotline number? Also consider referring a child to a psychotherapist if needed. Some schools offered counseling after the election. It is worthwhile to contact school officials if a student is struggling or could benefit from additional support.

Although many unknowns remain, 1 thing is certain: children will have more questions and we must be ready to answer.

Balkozar S. Adam, MD

Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

University of Missouri

Columbia, Missouri

Co-Editor

Missouri Psychiatry Newsletter

Jefferson City, Missouri

Two additional adjunctive therapies for mental health

I was excited to read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about adjunctive therapies for mental health disorders (Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider,

The article missed 2 important vitamins that play a crucial role in positive mental health treatment outcomes: folic acid and vitamin B12. In my practice, I have found up to 50% of my patients with depression have a vitamin B12 deficiency. After supplementation, these patients’ symptoms improve to the point that we often can reduce or eliminate medication. Folic acid deficiency has been found among individuals with depression and linked to poor response to treatment.1 Higher serum levels of homocysteine—a consequence of low folic acid levels—are linked to increased risk of developing depression later in life, as well as higher risk of cardiovascular disease.2,3 Folate also can be used for enhancing treatment response to antidepressants by increasing production of neurotransmitters.2

Another factor to consider is methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) variants. Approximately 20% of the population cannot methylate B vitamins because of a variation on the MTHFR gene.4,5 These patients are at increased risk for depression because they are unable to use B vitamins, which are essential in the synthesis of serotonin and dopamine. These patients do not respond to B12 and folate supplements. For these individuals, I recommend methylated products, which can be purchased online.

I have found these practices, as well as many of those listed in the editorial, are effective in treating depression and anxiety.

Lara Kain, PA-C, MPAS

Psychiatric Physician Assistant

Tidewater Psychotherapy Services

Virginia Beach, Virginia

References

1. Kaner G, Soylu M, Yüksel N, et al. Evaluation of nutritional status of patients with depression. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:521481. doi: 10.1155/2015/521481.

2. Seppälä J, Koponen H, Kautiainen H, et al. Association between vitamin B12 and melancholic depressive symptoms: a Finnish population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-145.

3. Petridou ET, Kousoulis AA, Michelakos T, et al. Folate and B12 serum levels in association with depression in the aged: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(9):965-973.

4. Lynch B. MTHFR mutations and the conditions they cause. MTHFR.Net. http://mthfr.net/mthfr-mutations-and-the-conditions-they-cause/2011/09/07. Accessed February 16, 2017.

5. Eszlari N, Kovacs D, Petschner P, et al. Distinct effects of folate pathway genes MTHFR and MTHFD1L on ruminative response style: a potential risk mechanism for depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(3):e745. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.19.

An honest perspective on Cannabis in therapy

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments” (From the

As a psychiatrist specializing in bipolar and psychotic disorders—as well as the founder and Board President of Doctors for Cannabis Regulation—I appreciate his reservations about the potential of Cannabis to trigger psychosis in vulnerable individuals. My reading of the literature is there is good evidence for marijuana as a trigger—not as a cause—of the disease. However, what is the evidence for hallucinogens?

Cannabis can have adverse effects on brain development, but it is not clear whether those effects are worse than those caused by alcohol. In the absence of any head-to-head studies, how can we proceed?

David L. Nathan, MD, DFAPA

Clinical Associate Professor

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Director of Continuing Medical Education

Princeton HealthCare System

Princeton, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

LSD can cause psychosis, paranoid delusions, and altered thinking in addition to vivid visual hallucinations in some individuals but not all, because vulnerability occurs on a spectrum. I postulate that the recently discovered inverse agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, pimavanserin (FDA-approved for visual hallucinations and delusions of Parkinson’s disease psychosis), might be effective for LSD psychosis because this hallucinogen has a strong binding affinity to the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.

Studies show that marijuana can induce apoptosis, which would adversely affect brain development. Patients with schizophrenia who abuse marijuana have a lower gray matter volume than those who do not abuse the drug, and both groups have lower gray matter volume than matched healthy controls. I strongly advise a pregnant woman against smoking marijuana because it could impair the fetus’s brain development.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Self-administering LSD: Solution or abuse

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial (From the Editor,

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Retired Tenured Professor of Psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not aware of any systematic data about self-prescribed use of microdoses of LSD to reduce anxiety and depression. Among persons with anxiety and depression who have not had access to psychiatric care, self-medicating with agents such as alcohol, stimulants, ketamine, or LSD is regarded as substance abuse. It also is questionable whether people can determine which microdose of LSD to use. Finally, most drugs of abuse are not “pure,” and many are laced with potentially harmful contaminants.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Why medical psychiatry is vital for my patients

Dr. Paul Summergrad’s guest editorial “Medical psychiatry: The skill of integrating medical and psychiatric care” (

For me, the most inspiring sentence in Dr. Summergrad’s editorial was, “It is incumbent on us to pursue the medical differential of patients when we think it is needed, even if other physicians disagree.” I believe that this describes our job as physicians who specialize in psychiatry. To have a clinician of Dr. Summergrad’s stature write this was inspiring because it goes to the core of what more of us should do.

Ruth Myers, MD

Psychiatrist

The Community Circle PLLC

Burnsville, Minnesota

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia: What are realistic treatment goals?

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

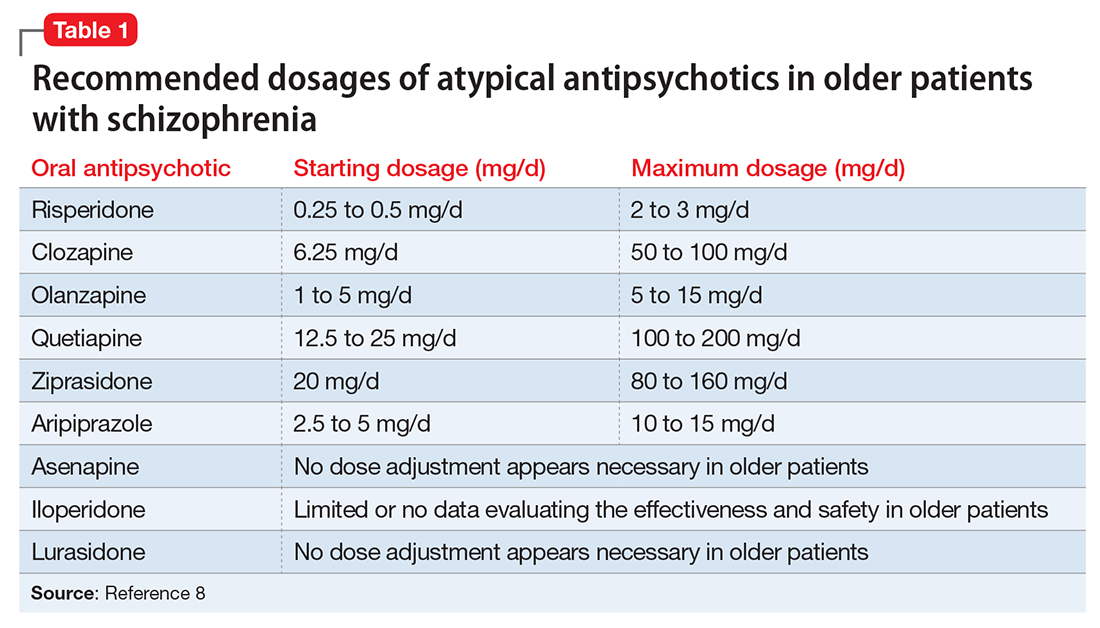

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

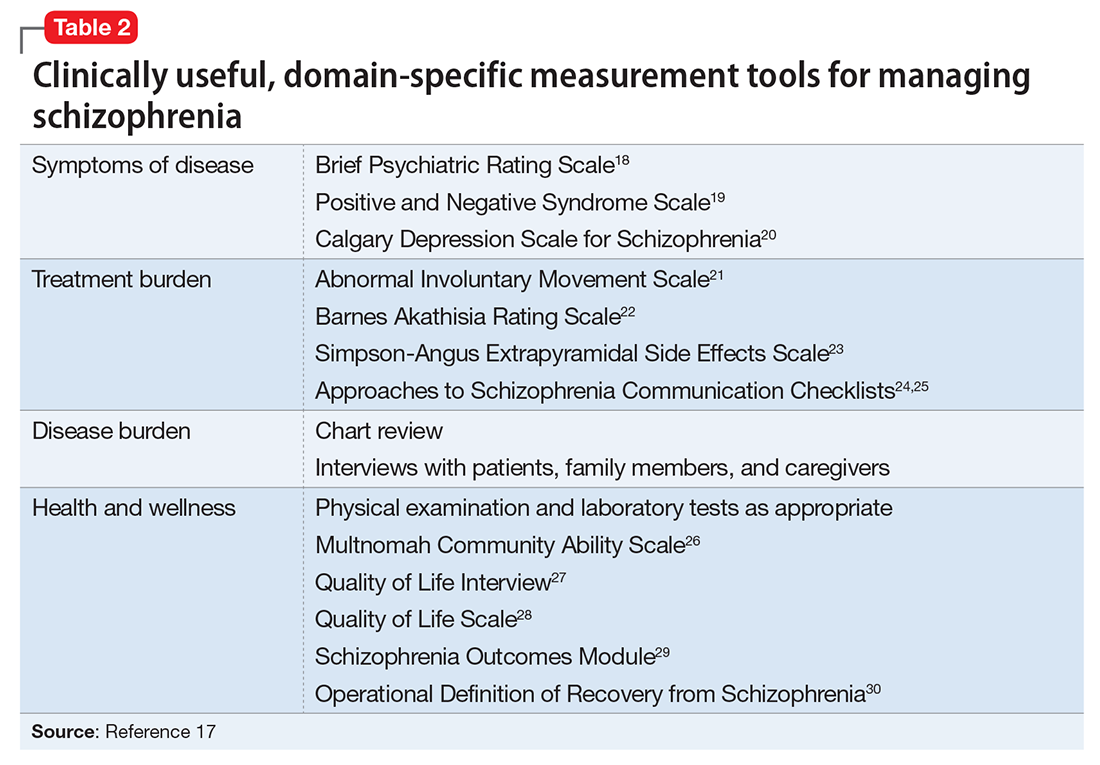

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.