User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Prazosin and doxazosin for PTSD are underutilized and underdosed

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

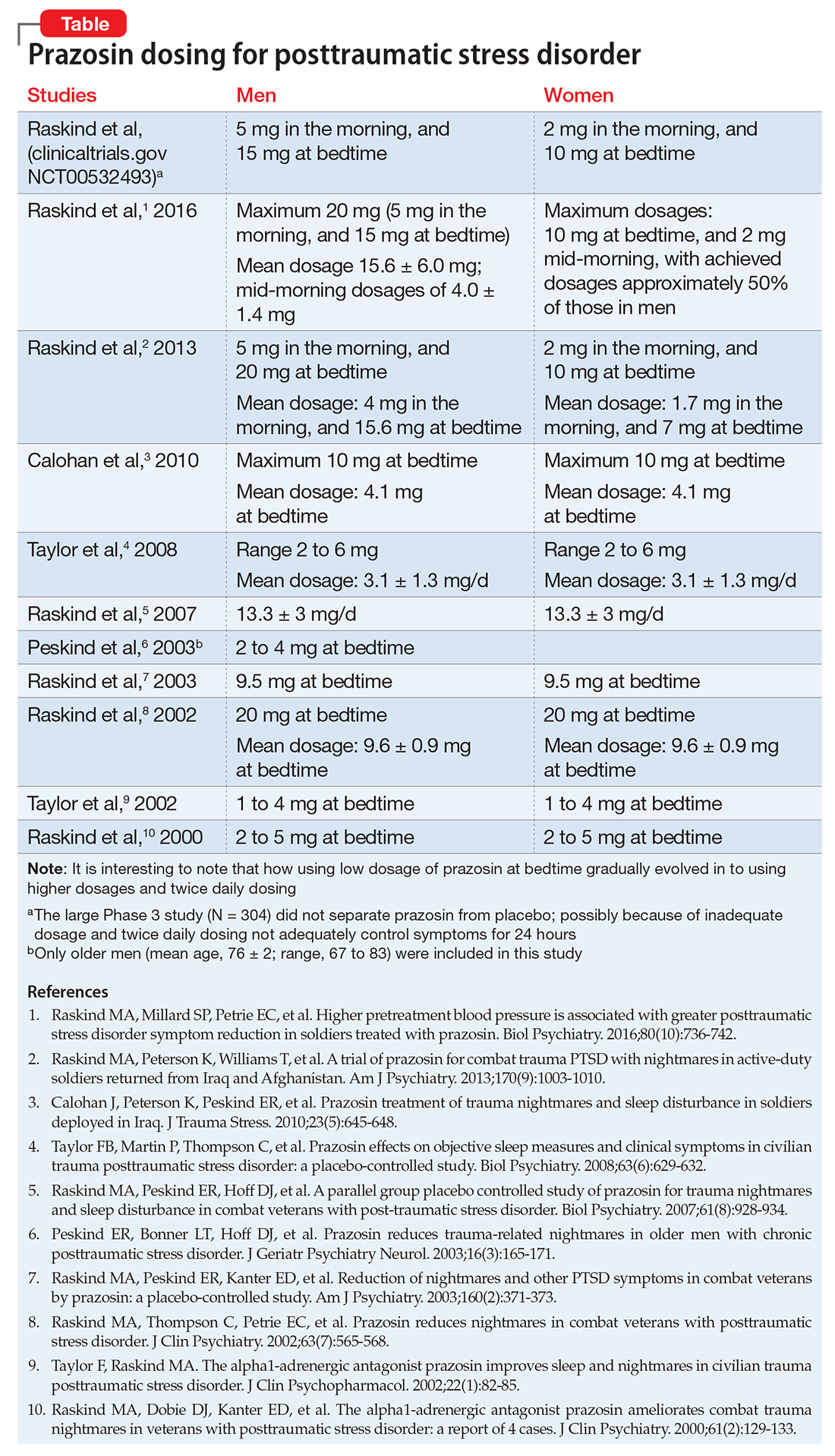

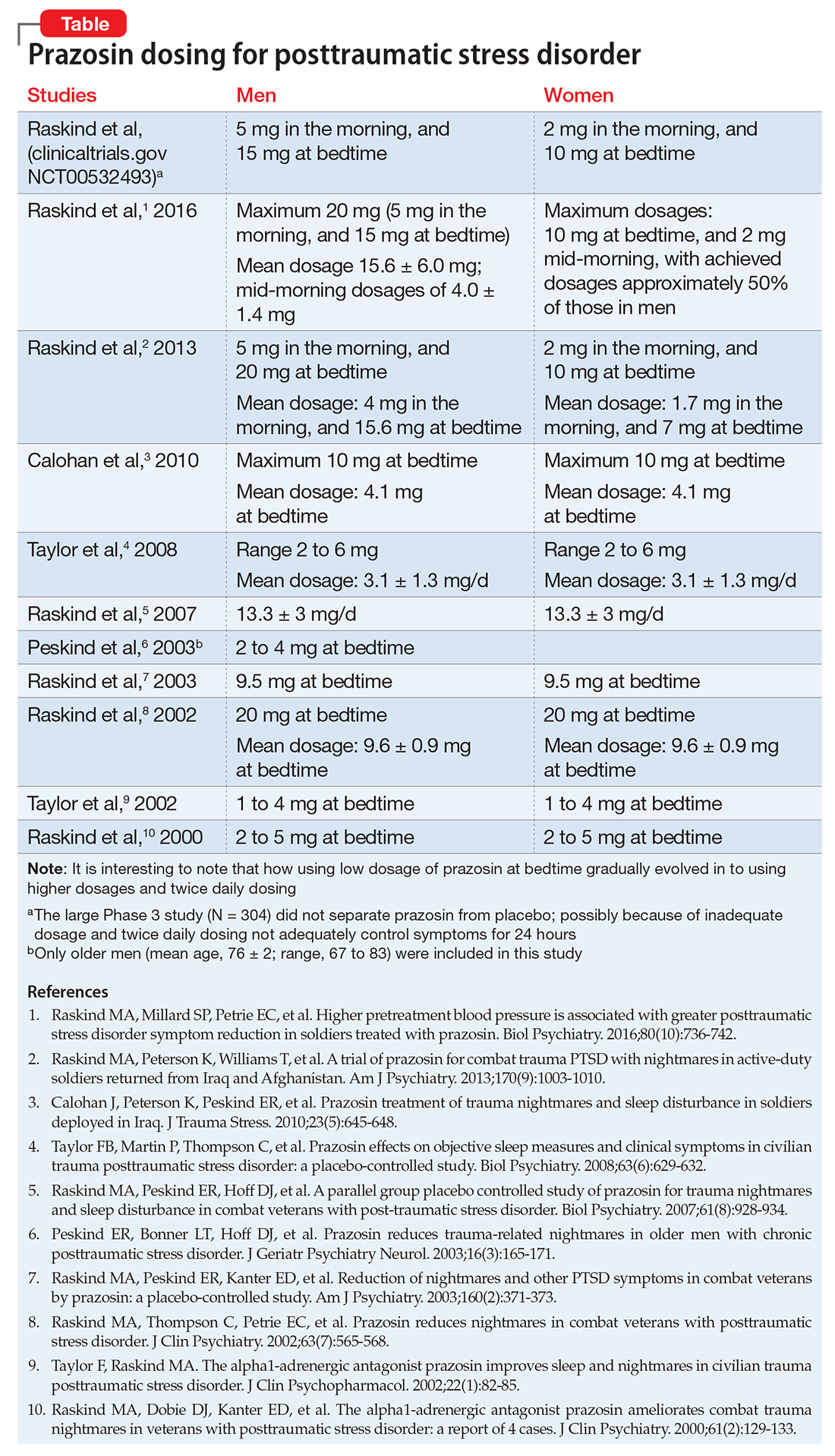

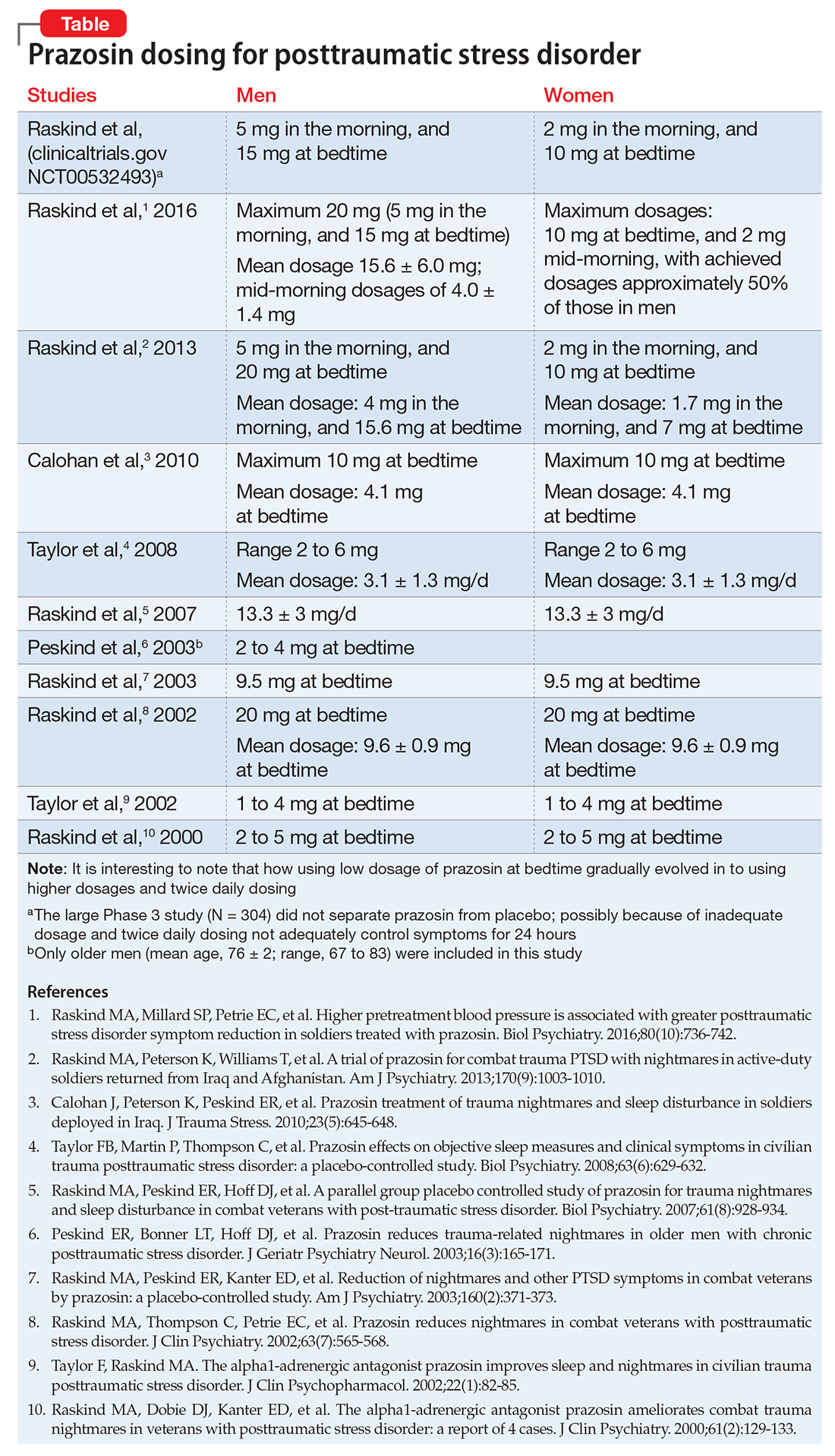

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

What I wish I knew when I started my internship

In my first year of residency I faced a steep learning curve. I learned a lot about psychiatry, but I learned so much more about myself. If I had known then what I know now, my internship would have been smoother and more enjoyable.

Be organized. Create systems to remember your patients’ information and your to-do list. I have templates of progress notes, psychiatry assessments, mental status assessments, “rounds sheets” (a sheet listing every patient on my floor, including their diagnoses, laboratories, medications, and other notes). Although my system involves lots of paper, I like it. Make a system that works for you. Go out and have fun. I know you are tired, you haven’t slept, and your apartment is a mess, but you won’t remember that time you went home, did laundry, and went to bed early. You will remember the fun night when you and other interns went out and explored the city.

Unplug from medicine. Nothing is more boring than working for 12 hours, only to go out for drinks with coworkers and talk about work. Although you need to vent, life is more than medicine. Find time for something else. Read a book, play a video game, hang out with people who are not doctors. I started a monthly book club with other women around my age. Make some time for something other than your profession.

Reach out to your senior colleagues. I was so concerned about making a good first impression that I didn’t share my concerns with others. I kept my head low because I always blame myself first when something is wrong.

During an off-service rotation, I was unable to finish my shift because I had food poisoning. To make up for that uncompleted shift, the chief from that service gave me 2 extra night shifts. I found the measure extreme, but thought it was my fault for going home early. A few days later, the Psychiatry Chief Resident approached me, after he had seen my schedule and spoke with the other chief because he found the situation unfair. He was reaching out to me saying, “We’ve got your back.” I realized that it wasn’t always my fault, and I could speak up when there was an issue. I was fortunate to have seniors and chiefs who looked out for me. I always found support, good advice, and respect for my feelings.

If you have questions or concerns, are anxious, or feel something is wrong, approach a senior or the chief. They were in your shoes once and will give you their best advice.

Medicine is different in the United States. As an international medica

People understand that you are from another country. At the beginning, I used Google to search for everything, and then I realized that my 2 wonderful students didn’t think less of me because I didn’t know what BKA (below knee amputation) means. Do not be ashamed if you don’t know how things work in a different country. You will find people who are willing to help you; you will learn, and it will be a minor thing a year from now.

Keep your support system. It was 3

If you moved away from home for residency, you are surrounded by new faces and far from the people you are comfortable with. Do not lose touch with them because you never know when you might need them the most. I had a hard road getting to where I am now, and many people helped me. You have to be there for them, too; a text message takes 30 seconds, and an e-mail, 1 minute.

Remember, you need to take care of yourself before taking care of others. No matter how much the MD or DO degree makes you feel like a superhero, you are still human.

In my first year of residency I faced a steep learning curve. I learned a lot about psychiatry, but I learned so much more about myself. If I had known then what I know now, my internship would have been smoother and more enjoyable.

Be organized. Create systems to remember your patients’ information and your to-do list. I have templates of progress notes, psychiatry assessments, mental status assessments, “rounds sheets” (a sheet listing every patient on my floor, including their diagnoses, laboratories, medications, and other notes). Although my system involves lots of paper, I like it. Make a system that works for you. Go out and have fun. I know you are tired, you haven’t slept, and your apartment is a mess, but you won’t remember that time you went home, did laundry, and went to bed early. You will remember the fun night when you and other interns went out and explored the city.

Unplug from medicine. Nothing is more boring than working for 12 hours, only to go out for drinks with coworkers and talk about work. Although you need to vent, life is more than medicine. Find time for something else. Read a book, play a video game, hang out with people who are not doctors. I started a monthly book club with other women around my age. Make some time for something other than your profession.

Reach out to your senior colleagues. I was so concerned about making a good first impression that I didn’t share my concerns with others. I kept my head low because I always blame myself first when something is wrong.

During an off-service rotation, I was unable to finish my shift because I had food poisoning. To make up for that uncompleted shift, the chief from that service gave me 2 extra night shifts. I found the measure extreme, but thought it was my fault for going home early. A few days later, the Psychiatry Chief Resident approached me, after he had seen my schedule and spoke with the other chief because he found the situation unfair. He was reaching out to me saying, “We’ve got your back.” I realized that it wasn’t always my fault, and I could speak up when there was an issue. I was fortunate to have seniors and chiefs who looked out for me. I always found support, good advice, and respect for my feelings.

If you have questions or concerns, are anxious, or feel something is wrong, approach a senior or the chief. They were in your shoes once and will give you their best advice.

Medicine is different in the United States. As an international medica

People understand that you are from another country. At the beginning, I used Google to search for everything, and then I realized that my 2 wonderful students didn’t think less of me because I didn’t know what BKA (below knee amputation) means. Do not be ashamed if you don’t know how things work in a different country. You will find people who are willing to help you; you will learn, and it will be a minor thing a year from now.

Keep your support system. It was 3

If you moved away from home for residency, you are surrounded by new faces and far from the people you are comfortable with. Do not lose touch with them because you never know when you might need them the most. I had a hard road getting to where I am now, and many people helped me. You have to be there for them, too; a text message takes 30 seconds, and an e-mail, 1 minute.

Remember, you need to take care of yourself before taking care of others. No matter how much the MD or DO degree makes you feel like a superhero, you are still human.

In my first year of residency I faced a steep learning curve. I learned a lot about psychiatry, but I learned so much more about myself. If I had known then what I know now, my internship would have been smoother and more enjoyable.

Be organized. Create systems to remember your patients’ information and your to-do list. I have templates of progress notes, psychiatry assessments, mental status assessments, “rounds sheets” (a sheet listing every patient on my floor, including their diagnoses, laboratories, medications, and other notes). Although my system involves lots of paper, I like it. Make a system that works for you. Go out and have fun. I know you are tired, you haven’t slept, and your apartment is a mess, but you won’t remember that time you went home, did laundry, and went to bed early. You will remember the fun night when you and other interns went out and explored the city.

Unplug from medicine. Nothing is more boring than working for 12 hours, only to go out for drinks with coworkers and talk about work. Although you need to vent, life is more than medicine. Find time for something else. Read a book, play a video game, hang out with people who are not doctors. I started a monthly book club with other women around my age. Make some time for something other than your profession.

Reach out to your senior colleagues. I was so concerned about making a good first impression that I didn’t share my concerns with others. I kept my head low because I always blame myself first when something is wrong.

During an off-service rotation, I was unable to finish my shift because I had food poisoning. To make up for that uncompleted shift, the chief from that service gave me 2 extra night shifts. I found the measure extreme, but thought it was my fault for going home early. A few days later, the Psychiatry Chief Resident approached me, after he had seen my schedule and spoke with the other chief because he found the situation unfair. He was reaching out to me saying, “We’ve got your back.” I realized that it wasn’t always my fault, and I could speak up when there was an issue. I was fortunate to have seniors and chiefs who looked out for me. I always found support, good advice, and respect for my feelings.

If you have questions or concerns, are anxious, or feel something is wrong, approach a senior or the chief. They were in your shoes once and will give you their best advice.

Medicine is different in the United States. As an international medica

People understand that you are from another country. At the beginning, I used Google to search for everything, and then I realized that my 2 wonderful students didn’t think less of me because I didn’t know what BKA (below knee amputation) means. Do not be ashamed if you don’t know how things work in a different country. You will find people who are willing to help you; you will learn, and it will be a minor thing a year from now.

Keep your support system. It was 3

If you moved away from home for residency, you are surrounded by new faces and far from the people you are comfortable with. Do not lose touch with them because you never know when you might need them the most. I had a hard road getting to where I am now, and many people helped me. You have to be there for them, too; a text message takes 30 seconds, and an e-mail, 1 minute.

Remember, you need to take care of yourself before taking care of others. No matter how much the MD or DO degree makes you feel like a superhero, you are still human.

Strategies for preventing and detecting false-negatives in urine drug screens

Urine drug screening (UDS) is an important tool in emergency settings and substance abuse or pain management clinics. According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 9.2% of individuals age ≥12 used an illicit drug other than marijuana within the previous year.1

There are 2 types of UDS: gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) and enzymatic immunoassay (EIA). A GC-MS uses a 2-step mechanisms to detect chemical compounds. First the GC separate the illicit substance into molecules, which is then introduced to the MS, which then separates compounds depending on their mass and charge using magnetic fields.2,3 Although GC-MS is a more definitive means to confirm the presence of a specific drug, it rarely is used in clinical settings because it is expensive and time-consuming.

EIA is an anti-drug antibody added to the patient’s urine that causes a positive indicator reaction that can be measured.2,3 It is a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective way of detecting illicit substances.4 However, there are limitations to EIAs used in most hospital laboratories.

Limitations of EIAs

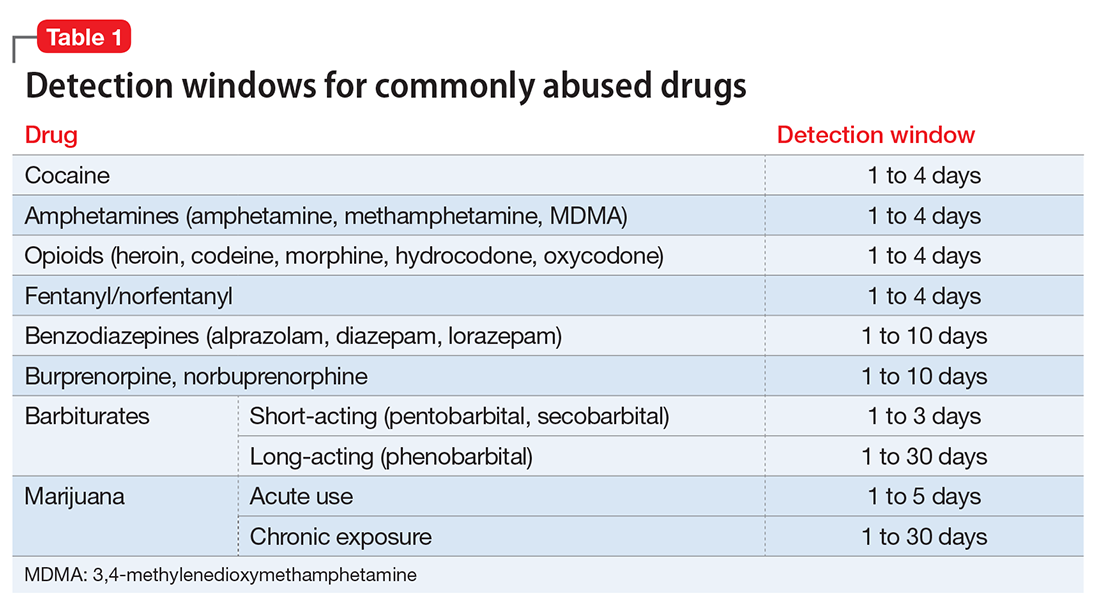

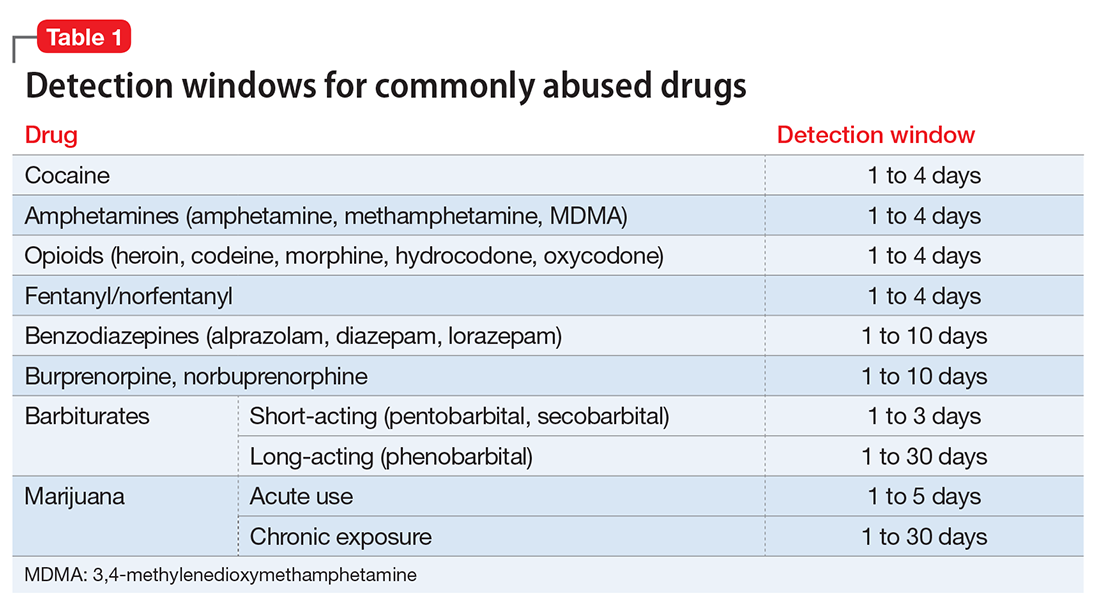

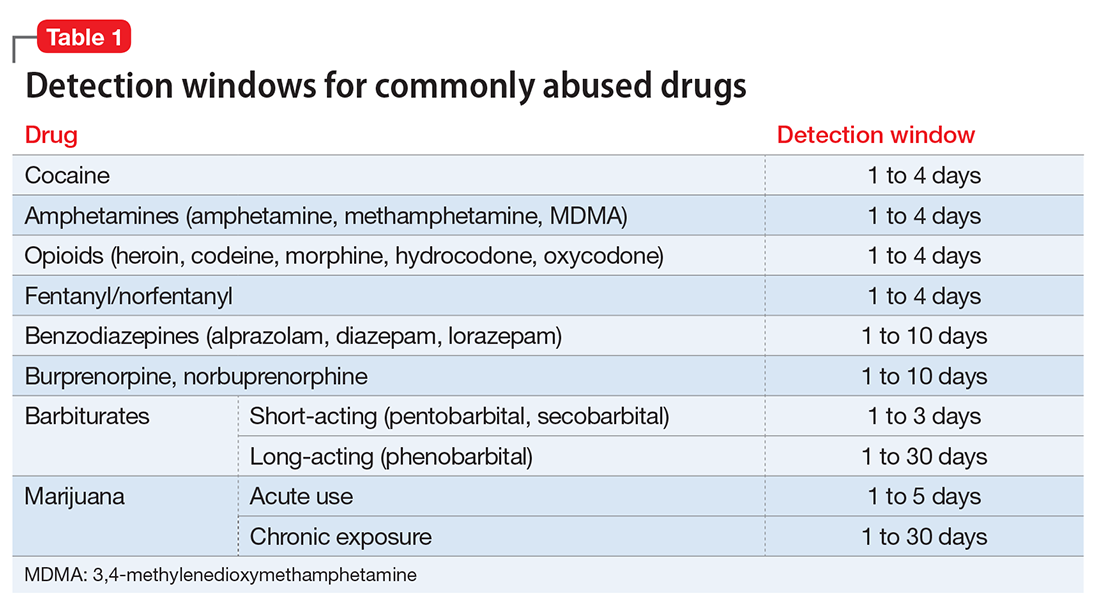

Timing. Results of the drug screen depend on the time and frequency of drug use (Table 1).5

Sensitivity. The immunoassay methods used vary in their ability to detect substances and depend on the test’s sensitivity; however, most of these versions have high sensitivity for detecting many illicit substances.4

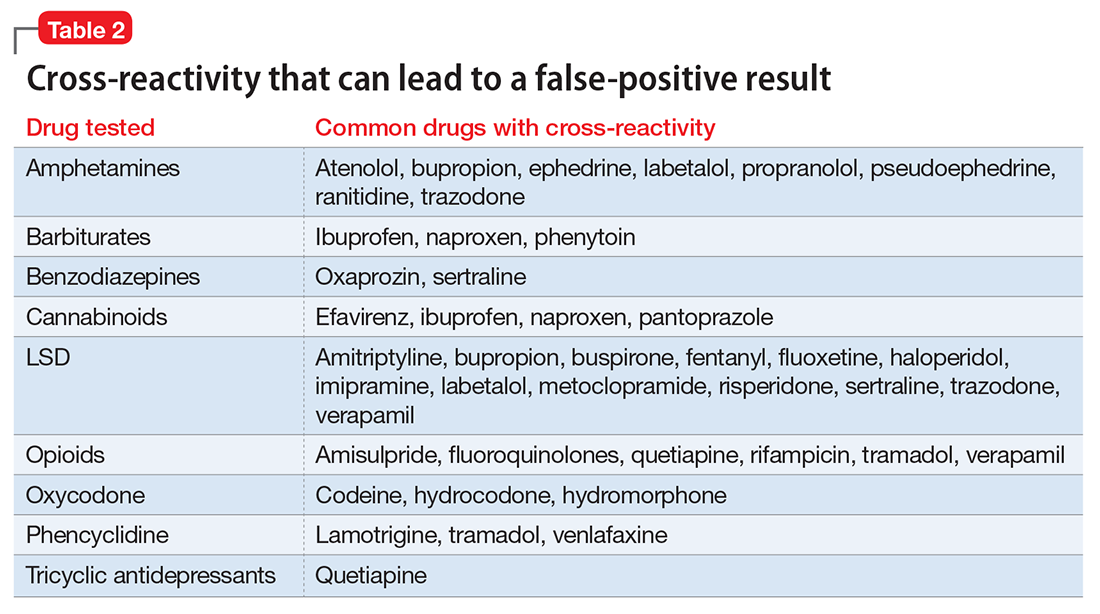

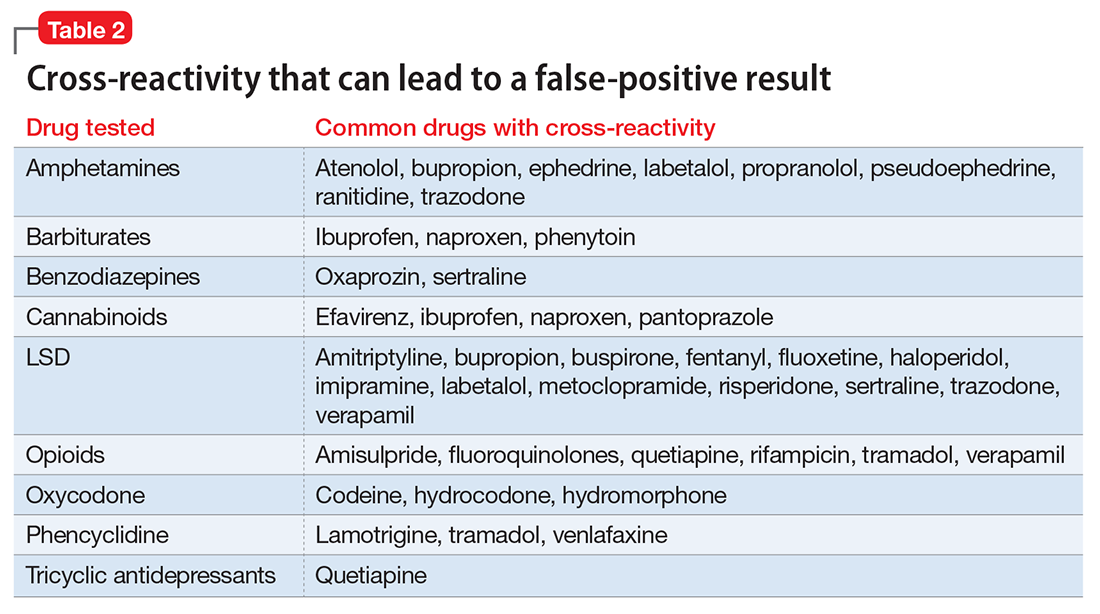

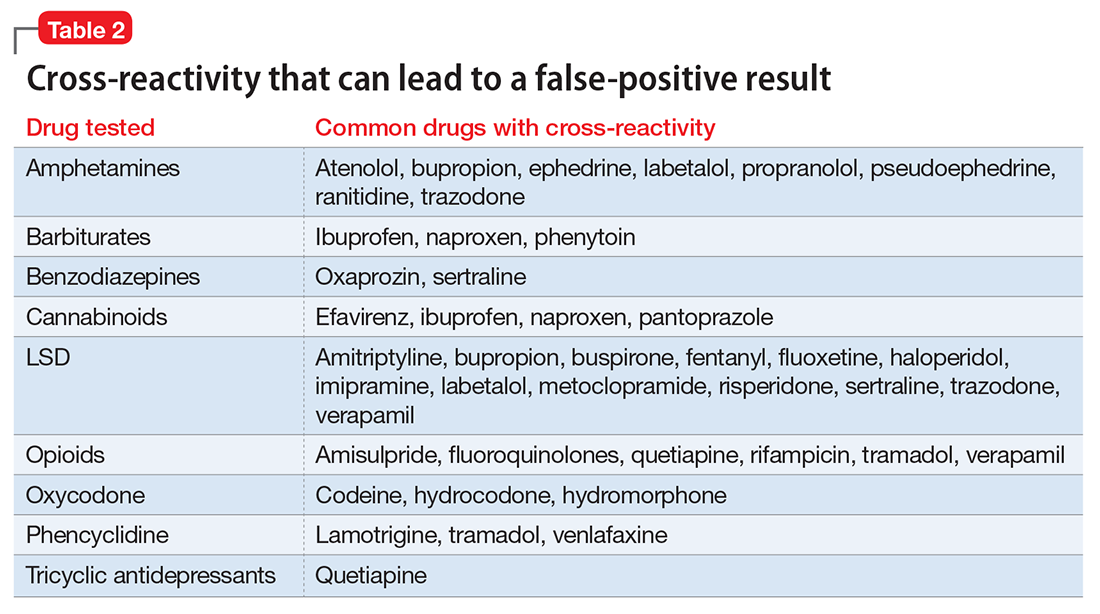

Specificity and cross-reactivity. Unfortunately, many drugs, such as opioids, amphetamines, and commonly prescribed medications, exhibit cross-reactivity that can produce false-positive results (Table 2).5,6

Synthetic cannabinoids, such as “spice” and cathinones, also known as “bath salts,” cannot be detected with standard UDS. However, some newer EIA kits can detect synthetic cannabinoids but do not detect newer designer drugs.7 Detection of specific cathinones by EIA is not yet available.7

Preventing false-negatives

Substance abusing individuals could try to avoid detection of illicit drug use by using the following techniques:

- In vivo methods, such as drinking a large amount of water or using herbal products, can lead to false-negative results because of dilution.8

- In vitro adulterants are substances added to urine samples after urination to avoid drug detection. Active ingredients include glutaraldehyde (Clean-X), sodium or potassium nitrate (Klear, Whizzies), pyridinium chlorochromate (Urine Luck), andj (Stealth).9

- Other methods used to avoid drug detection include substituting a urine sample with someone else’s clean urine or adding household products, such as bleach, vinegar, or pipe cleaner.

You can spot and prevent false-negatives by:

Directly observing the patient, which helps to prevent individuals from adding foreign materials or substituting the urine sample.

Visually inspecting the urine helps identify sample tampering. Adding household adulterants can produce unusually bubbly, cloudy, clear, or dark sample.

On-site analyses and laboratory analyses of samples. Commercially sold kits can detect adulterants by on-site analysis, such as Intect 7 and AdultaCheck 4 test strips.9 Simple on-site methods can help discover tampering, such as measuring the urine’s temperature and using pigmented toilet water. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends validity checks during laboratory analysis for all urine samples, including temperature, creatinine, specific gravity, pH, and tests for oxidizing adulterants.10

Considerations

The results of UDS should not be interpreted as absolute. Knowing the sensitivity and specificity of the UDS that your institution uses and the patient’s current medication regimen is valuable in distinguishing between true results and false-positives. False-positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. When EIA is positive and patient denies substance use, confirming the result with GC-MS may be a good clinical practice.3 Ordering a GC-MS test can be helpful in situations requiring greater precision, such as in methadone or pain management clinics, to verify if the patient is taking a prescribed medication properly or to rule out illicit exposures with greater certainty.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Steven Lippmann, MD, for his mentorship, encouragement, and editorial support.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Prevalence estimates, standard errors, P values, and sample sizes. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Published September 8, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

2. Schweitzer BN. An assessment of lateral flow immunoassay testing and gas chromatography mass spectrometry as methods for the detection of five drugs of abuse in forensic bloodstains. https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/19477/Schweitzer_bu_0017N_12357.pdf?sequence=1. Published 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

3. Pawlowski J, Ellingrod VL. Urine drug screens: when might a test result be false-positive? Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(10):17,22-24.

4. Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

5. AIT Laboratories. Physician’s reference for urine and blood drug testing and interpretation. http://web.archive.org/web/20160312195526/http://aitlabs.com/uploadedfiles/services/pocket_guide_smr086.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 7, 2017.

6. Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

7. Namera A, Kawamura M, Nakamoto A, et al. Comprehensive review of the detection methods for synthetic cannabinoids and cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):175-194.

8. Cone EJ, Lange R, Darwin WD. In vivo adulteration: excess fluid ingestion causes false-negative marijuana and cocaine urine test results. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22(6):460-473.

9. Jaffee WB, Trucco E, Levy S, et al. Is this urine really negative? A systematic review of tampering methods in urine drug screening and testing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(1):33-42.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mandatory guidelines for federal workplace drug testing programs. Federal Register. 2004;69:19644-19673.

Urine drug screening (UDS) is an important tool in emergency settings and substance abuse or pain management clinics. According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 9.2% of individuals age ≥12 used an illicit drug other than marijuana within the previous year.1

There are 2 types of UDS: gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) and enzymatic immunoassay (EIA). A GC-MS uses a 2-step mechanisms to detect chemical compounds. First the GC separate the illicit substance into molecules, which is then introduced to the MS, which then separates compounds depending on their mass and charge using magnetic fields.2,3 Although GC-MS is a more definitive means to confirm the presence of a specific drug, it rarely is used in clinical settings because it is expensive and time-consuming.

EIA is an anti-drug antibody added to the patient’s urine that causes a positive indicator reaction that can be measured.2,3 It is a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective way of detecting illicit substances.4 However, there are limitations to EIAs used in most hospital laboratories.

Limitations of EIAs

Timing. Results of the drug screen depend on the time and frequency of drug use (Table 1).5

Sensitivity. The immunoassay methods used vary in their ability to detect substances and depend on the test’s sensitivity; however, most of these versions have high sensitivity for detecting many illicit substances.4

Specificity and cross-reactivity. Unfortunately, many drugs, such as opioids, amphetamines, and commonly prescribed medications, exhibit cross-reactivity that can produce false-positive results (Table 2).5,6

Synthetic cannabinoids, such as “spice” and cathinones, also known as “bath salts,” cannot be detected with standard UDS. However, some newer EIA kits can detect synthetic cannabinoids but do not detect newer designer drugs.7 Detection of specific cathinones by EIA is not yet available.7

Preventing false-negatives

Substance abusing individuals could try to avoid detection of illicit drug use by using the following techniques:

- In vivo methods, such as drinking a large amount of water or using herbal products, can lead to false-negative results because of dilution.8

- In vitro adulterants are substances added to urine samples after urination to avoid drug detection. Active ingredients include glutaraldehyde (Clean-X), sodium or potassium nitrate (Klear, Whizzies), pyridinium chlorochromate (Urine Luck), andj (Stealth).9

- Other methods used to avoid drug detection include substituting a urine sample with someone else’s clean urine or adding household products, such as bleach, vinegar, or pipe cleaner.

You can spot and prevent false-negatives by:

Directly observing the patient, which helps to prevent individuals from adding foreign materials or substituting the urine sample.

Visually inspecting the urine helps identify sample tampering. Adding household adulterants can produce unusually bubbly, cloudy, clear, or dark sample.

On-site analyses and laboratory analyses of samples. Commercially sold kits can detect adulterants by on-site analysis, such as Intect 7 and AdultaCheck 4 test strips.9 Simple on-site methods can help discover tampering, such as measuring the urine’s temperature and using pigmented toilet water. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends validity checks during laboratory analysis for all urine samples, including temperature, creatinine, specific gravity, pH, and tests for oxidizing adulterants.10

Considerations

The results of UDS should not be interpreted as absolute. Knowing the sensitivity and specificity of the UDS that your institution uses and the patient’s current medication regimen is valuable in distinguishing between true results and false-positives. False-positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. When EIA is positive and patient denies substance use, confirming the result with GC-MS may be a good clinical practice.3 Ordering a GC-MS test can be helpful in situations requiring greater precision, such as in methadone or pain management clinics, to verify if the patient is taking a prescribed medication properly or to rule out illicit exposures with greater certainty.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Steven Lippmann, MD, for his mentorship, encouragement, and editorial support.

Urine drug screening (UDS) is an important tool in emergency settings and substance abuse or pain management clinics. According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 9.2% of individuals age ≥12 used an illicit drug other than marijuana within the previous year.1

There are 2 types of UDS: gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) and enzymatic immunoassay (EIA). A GC-MS uses a 2-step mechanisms to detect chemical compounds. First the GC separate the illicit substance into molecules, which is then introduced to the MS, which then separates compounds depending on their mass and charge using magnetic fields.2,3 Although GC-MS is a more definitive means to confirm the presence of a specific drug, it rarely is used in clinical settings because it is expensive and time-consuming.

EIA is an anti-drug antibody added to the patient’s urine that causes a positive indicator reaction that can be measured.2,3 It is a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective way of detecting illicit substances.4 However, there are limitations to EIAs used in most hospital laboratories.

Limitations of EIAs

Timing. Results of the drug screen depend on the time and frequency of drug use (Table 1).5

Sensitivity. The immunoassay methods used vary in their ability to detect substances and depend on the test’s sensitivity; however, most of these versions have high sensitivity for detecting many illicit substances.4

Specificity and cross-reactivity. Unfortunately, many drugs, such as opioids, amphetamines, and commonly prescribed medications, exhibit cross-reactivity that can produce false-positive results (Table 2).5,6

Synthetic cannabinoids, such as “spice” and cathinones, also known as “bath salts,” cannot be detected with standard UDS. However, some newer EIA kits can detect synthetic cannabinoids but do not detect newer designer drugs.7 Detection of specific cathinones by EIA is not yet available.7

Preventing false-negatives

Substance abusing individuals could try to avoid detection of illicit drug use by using the following techniques:

- In vivo methods, such as drinking a large amount of water or using herbal products, can lead to false-negative results because of dilution.8

- In vitro adulterants are substances added to urine samples after urination to avoid drug detection. Active ingredients include glutaraldehyde (Clean-X), sodium or potassium nitrate (Klear, Whizzies), pyridinium chlorochromate (Urine Luck), andj (Stealth).9

- Other methods used to avoid drug detection include substituting a urine sample with someone else’s clean urine or adding household products, such as bleach, vinegar, or pipe cleaner.

You can spot and prevent false-negatives by:

Directly observing the patient, which helps to prevent individuals from adding foreign materials or substituting the urine sample.

Visually inspecting the urine helps identify sample tampering. Adding household adulterants can produce unusually bubbly, cloudy, clear, or dark sample.

On-site analyses and laboratory analyses of samples. Commercially sold kits can detect adulterants by on-site analysis, such as Intect 7 and AdultaCheck 4 test strips.9 Simple on-site methods can help discover tampering, such as measuring the urine’s temperature and using pigmented toilet water. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends validity checks during laboratory analysis for all urine samples, including temperature, creatinine, specific gravity, pH, and tests for oxidizing adulterants.10

Considerations

The results of UDS should not be interpreted as absolute. Knowing the sensitivity and specificity of the UDS that your institution uses and the patient’s current medication regimen is valuable in distinguishing between true results and false-positives. False-positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. When EIA is positive and patient denies substance use, confirming the result with GC-MS may be a good clinical practice.3 Ordering a GC-MS test can be helpful in situations requiring greater precision, such as in methadone or pain management clinics, to verify if the patient is taking a prescribed medication properly or to rule out illicit exposures with greater certainty.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Steven Lippmann, MD, for his mentorship, encouragement, and editorial support.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Prevalence estimates, standard errors, P values, and sample sizes. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Published September 8, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

2. Schweitzer BN. An assessment of lateral flow immunoassay testing and gas chromatography mass spectrometry as methods for the detection of five drugs of abuse in forensic bloodstains. https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/19477/Schweitzer_bu_0017N_12357.pdf?sequence=1. Published 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

3. Pawlowski J, Ellingrod VL. Urine drug screens: when might a test result be false-positive? Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(10):17,22-24.

4. Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

5. AIT Laboratories. Physician’s reference for urine and blood drug testing and interpretation. http://web.archive.org/web/20160312195526/http://aitlabs.com/uploadedfiles/services/pocket_guide_smr086.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 7, 2017.

6. Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

7. Namera A, Kawamura M, Nakamoto A, et al. Comprehensive review of the detection methods for synthetic cannabinoids and cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):175-194.

8. Cone EJ, Lange R, Darwin WD. In vivo adulteration: excess fluid ingestion causes false-negative marijuana and cocaine urine test results. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22(6):460-473.

9. Jaffee WB, Trucco E, Levy S, et al. Is this urine really negative? A systematic review of tampering methods in urine drug screening and testing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(1):33-42.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mandatory guidelines for federal workplace drug testing programs. Federal Register. 2004;69:19644-19673.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Prevalence estimates, standard errors, P values, and sample sizes. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Published September 8, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

2. Schweitzer BN. An assessment of lateral flow immunoassay testing and gas chromatography mass spectrometry as methods for the detection of five drugs of abuse in forensic bloodstains. https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/19477/Schweitzer_bu_0017N_12357.pdf?sequence=1. Published 2016. Accessed February 7, 2017.

3. Pawlowski J, Ellingrod VL. Urine drug screens: when might a test result be false-positive? Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(10):17,22-24.

4. Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

5. AIT Laboratories. Physician’s reference for urine and blood drug testing and interpretation. http://web.archive.org/web/20160312195526/http://aitlabs.com/uploadedfiles/services/pocket_guide_smr086.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 7, 2017.

6. Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

7. Namera A, Kawamura M, Nakamoto A, et al. Comprehensive review of the detection methods for synthetic cannabinoids and cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):175-194.

8. Cone EJ, Lange R, Darwin WD. In vivo adulteration: excess fluid ingestion causes false-negative marijuana and cocaine urine test results. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22(6):460-473.

9. Jaffee WB, Trucco E, Levy S, et al. Is this urine really negative? A systematic review of tampering methods in urine drug screening and testing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(1):33-42.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mandatory guidelines for federal workplace drug testing programs. Federal Register. 2004;69:19644-19673.

Clinical rating scales

Expanding APRN practice and more

Medical psychiatry: The skill of integrating medical and psychiatric care

Although the meaning of these terms varied from department to department, biologically oriented programs—influenced by Eli Robins and Samuel Guze and DSM-III—were focused on descriptive psychiatry: reliable, observable, and symptom-based elements of psychiatric illness. Related and important elements were a focus on psychopharmacologic treatments, genetics, epidemiology, and putative mechanisms for both diseases and treatments. Psychodynamic programs had a primary focus on psychodynamic theory, with extensive training in long-term, depth-oriented psychotherapy. Many of these are programs employed charismatic and brilliant teachers whose supervisory and interviewing skills were legendary. And, of course, all the programs claimed they did everything and did it well.

However, none of these programs were exactly what I was looking for. Although I had a long-standing interest in psychodynamics and was fascinated by the implications of—what was then a far more nascent—neurobiology, I was looking for a program that had all of these elements, but also had a focus on, what I thought of as, “medical psychiatry.” Although this may have meant different things to others, and was known as “psychosomatic medicine” or “consultation-liaison psychiatry,” to me, it was about the psychiatric manifestations of medical and neurologic disorders.

My years training in internal medicine were full of patients with neuropsychiatric illness due to a host of general medical and neurologic disorders. When I was an intern, the most common admitting diagnosis was what we called “Delta MS”—change in mental status. As I advanced in my residency and focused on a subspecialty of internal medicine, it became clear that whichever illnesses I studied, conditions such as anxiety disorders in Grave’s disease or the psychotic symptoms in lupus held my interest. Finally, the only specialty left was psychiatry.

The only program I found that seemed to understand medical psychiatry at the time was at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). MGH not only had eminent psychiatrists in every area of the field, it seemed, but also a special focus on training psychiatrists in medical settings and as medical experts. My first Chief of Psychiatry was Thomas P. Hackett, MD—a brilliant clinician, raconteur, and polymath—who had written a cri de coeur on the importance of medical skills and training in psychiatry.1 At last, I had found a place where I could remain a physician and think and learn about every aspect of psychiatry, especially medical psychiatry.

What is medical psychiatry, and why is it relevant now?

There has been substantial and increasing interest in the integration of medical and psychiatric care. Whether it is collaborative care or co-location models, the recognition of the high rate of combined medical and psychiatric illnesses and associated increased mortality and total health care costs of these patients requires psychiatrists to be deeply familiar with the interactions among medical and psychiatric conditions.

Building on long-developed expertise in consultation-liaison psychiatry and other forms of medical psychiatric training, such as double-board medicine–psychiatry programs, medical psychiatry includes several specific areas of knowledge and skill sets, including understanding the impact that psychiatric illnesses and the medications used to treat them can have on medical illnesses and the ways in which the presence of medical disorders can change the presentation of psychiatric illnesses. Similarly, the psychiatric impact of the general medical pharmacopeia and the ways in which psychiatric illness can affect the presentation of medical illness are important for all psychiatrists to know. Most importantly, medical psychiatry should focus on the medical and neurologic causes of psychiatric illnesses. Many general medical conditions produce symptoms, which, in whole or in part, mimic psychiatric illnesses and, in some cases, could lead to psychiatric disorders, which makes identification of the underlying cause difficult.

Whether due to infectious, autoimmune, metabolic, or endocrinologic disorders, being aware of these conditions and, where clinical circumstances warrant, be able to diagnose them, with other specialists as needed, and ensure they are appropriately treated should be an essential skill for psychiatrists.

An illustrative case

I remember a case from early in my training of a woman with a late-onset mood disorder with abulia, wide-based gait, and urinary incontinence, in addition to withdrawal and loss of pleasure. Despite the skepticism of the neurology team, at autopsy she was found to have arteriosclerosis of the deep, penetrating arterioles causing white matter hyperintensities—Binswanger’s disease. There was no question that despite the neurologic cause of her symptoms treating her depression with antidepressants was needed and helpful. It also was important that her family was aware of her underlying medical condition and its implications for her care.2

Medicine is our calling

Many of these illnesses, even when identified, require expert psychiatric management of psychiatric symptoms. This should not be surprising to psychiatrists or other clinicians. No one expects a cardiologist to beg off the care of a patient with heart failure caused by alcohol abuse or a virus rather than vascular heart disease, and psychiatrists likewise need to manage psychosis due to steroid use or N-methyl-

Medical psychiatry has a broader and more inclusive perspective than what we generally mean by “biological psychiatry,” if by the latter, we mean a focus on the neurobiology and psychopharmacology of “primary” psychiatric conditions that are not secondary to other medical or neurologic disorders. As important and fundamental as deep understanding of neurobiology, genetics, and psychopharmacology are, medical psychiatry embeds our work more broadly in all of human biology and requires the full breadth of our medical training.

At a time when political battles over prescriptive privileges by non-medically trained mental health clinicians engage legislatures and professional organizations, medical psychiatry is a powerful reminder that prescribing or not prescribing medications is the final step in, what should be, an extensive, clinical evaluation including a thorough medical work up and consideration of the medical–psychiatric interactions and the differential diagnosis of these illnesses. It is, after all, what physicians do and is essential to our calling as psychiatric physicians. If psychiatrists are not at home in medicine, as Tom Hackett reminded us in 19771—at a time when psychiatry had temporarily eliminated the requirement for medical internships—then, indeed, psychiatry would be “homeless.”

2. Summergrad P. Depression in Binswanger’s encephalopathy responsive to tranylcypromine: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(2):69-70.

Although the meaning of these terms varied from department to department, biologically oriented programs—influenced by Eli Robins and Samuel Guze and DSM-III—were focused on descriptive psychiatry: reliable, observable, and symptom-based elements of psychiatric illness. Related and important elements were a focus on psychopharmacologic treatments, genetics, epidemiology, and putative mechanisms for both diseases and treatments. Psychodynamic programs had a primary focus on psychodynamic theory, with extensive training in long-term, depth-oriented psychotherapy. Many of these are programs employed charismatic and brilliant teachers whose supervisory and interviewing skills were legendary. And, of course, all the programs claimed they did everything and did it well.

However, none of these programs were exactly what I was looking for. Although I had a long-standing interest in psychodynamics and was fascinated by the implications of—what was then a far more nascent—neurobiology, I was looking for a program that had all of these elements, but also had a focus on, what I thought of as, “medical psychiatry.” Although this may have meant different things to others, and was known as “psychosomatic medicine” or “consultation-liaison psychiatry,” to me, it was about the psychiatric manifestations of medical and neurologic disorders.

My years training in internal medicine were full of patients with neuropsychiatric illness due to a host of general medical and neurologic disorders. When I was an intern, the most common admitting diagnosis was what we called “Delta MS”—change in mental status. As I advanced in my residency and focused on a subspecialty of internal medicine, it became clear that whichever illnesses I studied, conditions such as anxiety disorders in Grave’s disease or the psychotic symptoms in lupus held my interest. Finally, the only specialty left was psychiatry.

The only program I found that seemed to understand medical psychiatry at the time was at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). MGH not only had eminent psychiatrists in every area of the field, it seemed, but also a special focus on training psychiatrists in medical settings and as medical experts. My first Chief of Psychiatry was Thomas P. Hackett, MD—a brilliant clinician, raconteur, and polymath—who had written a cri de coeur on the importance of medical skills and training in psychiatry.1 At last, I had found a place where I could remain a physician and think and learn about every aspect of psychiatry, especially medical psychiatry.

What is medical psychiatry, and why is it relevant now?

There has been substantial and increasing interest in the integration of medical and psychiatric care. Whether it is collaborative care or co-location models, the recognition of the high rate of combined medical and psychiatric illnesses and associated increased mortality and total health care costs of these patients requires psychiatrists to be deeply familiar with the interactions among medical and psychiatric conditions.

Building on long-developed expertise in consultation-liaison psychiatry and other forms of medical psychiatric training, such as double-board medicine–psychiatry programs, medical psychiatry includes several specific areas of knowledge and skill sets, including understanding the impact that psychiatric illnesses and the medications used to treat them can have on medical illnesses and the ways in which the presence of medical disorders can change the presentation of psychiatric illnesses. Similarly, the psychiatric impact of the general medical pharmacopeia and the ways in which psychiatric illness can affect the presentation of medical illness are important for all psychiatrists to know. Most importantly, medical psychiatry should focus on the medical and neurologic causes of psychiatric illnesses. Many general medical conditions produce symptoms, which, in whole or in part, mimic psychiatric illnesses and, in some cases, could lead to psychiatric disorders, which makes identification of the underlying cause difficult.

Whether due to infectious, autoimmune, metabolic, or endocrinologic disorders, being aware of these conditions and, where clinical circumstances warrant, be able to diagnose them, with other specialists as needed, and ensure they are appropriately treated should be an essential skill for psychiatrists.

An illustrative case

I remember a case from early in my training of a woman with a late-onset mood disorder with abulia, wide-based gait, and urinary incontinence, in addition to withdrawal and loss of pleasure. Despite the skepticism of the neurology team, at autopsy she was found to have arteriosclerosis of the deep, penetrating arterioles causing white matter hyperintensities—Binswanger’s disease. There was no question that despite the neurologic cause of her symptoms treating her depression with antidepressants was needed and helpful. It also was important that her family was aware of her underlying medical condition and its implications for her care.2

Medicine is our calling

Many of these illnesses, even when identified, require expert psychiatric management of psychiatric symptoms. This should not be surprising to psychiatrists or other clinicians. No one expects a cardiologist to beg off the care of a patient with heart failure caused by alcohol abuse or a virus rather than vascular heart disease, and psychiatrists likewise need to manage psychosis due to steroid use or N-methyl-

Medical psychiatry has a broader and more inclusive perspective than what we generally mean by “biological psychiatry,” if by the latter, we mean a focus on the neurobiology and psychopharmacology of “primary” psychiatric conditions that are not secondary to other medical or neurologic disorders. As important and fundamental as deep understanding of neurobiology, genetics, and psychopharmacology are, medical psychiatry embeds our work more broadly in all of human biology and requires the full breadth of our medical training.

At a time when political battles over prescriptive privileges by non-medically trained mental health clinicians engage legislatures and professional organizations, medical psychiatry is a powerful reminder that prescribing or not prescribing medications is the final step in, what should be, an extensive, clinical evaluation including a thorough medical work up and consideration of the medical–psychiatric interactions and the differential diagnosis of these illnesses. It is, after all, what physicians do and is essential to our calling as psychiatric physicians. If psychiatrists are not at home in medicine, as Tom Hackett reminded us in 19771—at a time when psychiatry had temporarily eliminated the requirement for medical internships—then, indeed, psychiatry would be “homeless.”

Although the meaning of these terms varied from department to department, biologically oriented programs—influenced by Eli Robins and Samuel Guze and DSM-III—were focused on descriptive psychiatry: reliable, observable, and symptom-based elements of psychiatric illness. Related and important elements were a focus on psychopharmacologic treatments, genetics, epidemiology, and putative mechanisms for both diseases and treatments. Psychodynamic programs had a primary focus on psychodynamic theory, with extensive training in long-term, depth-oriented psychotherapy. Many of these are programs employed charismatic and brilliant teachers whose supervisory and interviewing skills were legendary. And, of course, all the programs claimed they did everything and did it well.

However, none of these programs were exactly what I was looking for. Although I had a long-standing interest in psychodynamics and was fascinated by the implications of—what was then a far more nascent—neurobiology, I was looking for a program that had all of these elements, but also had a focus on, what I thought of as, “medical psychiatry.” Although this may have meant different things to others, and was known as “psychosomatic medicine” or “consultation-liaison psychiatry,” to me, it was about the psychiatric manifestations of medical and neurologic disorders.

My years training in internal medicine were full of patients with neuropsychiatric illness due to a host of general medical and neurologic disorders. When I was an intern, the most common admitting diagnosis was what we called “Delta MS”—change in mental status. As I advanced in my residency and focused on a subspecialty of internal medicine, it became clear that whichever illnesses I studied, conditions such as anxiety disorders in Grave’s disease or the psychotic symptoms in lupus held my interest. Finally, the only specialty left was psychiatry.

The only program I found that seemed to understand medical psychiatry at the time was at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). MGH not only had eminent psychiatrists in every area of the field, it seemed, but also a special focus on training psychiatrists in medical settings and as medical experts. My first Chief of Psychiatry was Thomas P. Hackett, MD—a brilliant clinician, raconteur, and polymath—who had written a cri de coeur on the importance of medical skills and training in psychiatry.1 At last, I had found a place where I could remain a physician and think and learn about every aspect of psychiatry, especially medical psychiatry.

What is medical psychiatry, and why is it relevant now?

There has been substantial and increasing interest in the integration of medical and psychiatric care. Whether it is collaborative care or co-location models, the recognition of the high rate of combined medical and psychiatric illnesses and associated increased mortality and total health care costs of these patients requires psychiatrists to be deeply familiar with the interactions among medical and psychiatric conditions.

Building on long-developed expertise in consultation-liaison psychiatry and other forms of medical psychiatric training, such as double-board medicine–psychiatry programs, medical psychiatry includes several specific areas of knowledge and skill sets, including understanding the impact that psychiatric illnesses and the medications used to treat them can have on medical illnesses and the ways in which the presence of medical disorders can change the presentation of psychiatric illnesses. Similarly, the psychiatric impact of the general medical pharmacopeia and the ways in which psychiatric illness can affect the presentation of medical illness are important for all psychiatrists to know. Most importantly, medical psychiatry should focus on the medical and neurologic causes of psychiatric illnesses. Many general medical conditions produce symptoms, which, in whole or in part, mimic psychiatric illnesses and, in some cases, could lead to psychiatric disorders, which makes identification of the underlying cause difficult.

Whether due to infectious, autoimmune, metabolic, or endocrinologic disorders, being aware of these conditions and, where clinical circumstances warrant, be able to diagnose them, with other specialists as needed, and ensure they are appropriately treated should be an essential skill for psychiatrists.

An illustrative case

I remember a case from early in my training of a woman with a late-onset mood disorder with abulia, wide-based gait, and urinary incontinence, in addition to withdrawal and loss of pleasure. Despite the skepticism of the neurology team, at autopsy she was found to have arteriosclerosis of the deep, penetrating arterioles causing white matter hyperintensities—Binswanger’s disease. There was no question that despite the neurologic cause of her symptoms treating her depression with antidepressants was needed and helpful. It also was important that her family was aware of her underlying medical condition and its implications for her care.2

Medicine is our calling

Many of these illnesses, even when identified, require expert psychiatric management of psychiatric symptoms. This should not be surprising to psychiatrists or other clinicians. No one expects a cardiologist to beg off the care of a patient with heart failure caused by alcohol abuse or a virus rather than vascular heart disease, and psychiatrists likewise need to manage psychosis due to steroid use or N-methyl-

Medical psychiatry has a broader and more inclusive perspective than what we generally mean by “biological psychiatry,” if by the latter, we mean a focus on the neurobiology and psychopharmacology of “primary” psychiatric conditions that are not secondary to other medical or neurologic disorders. As important and fundamental as deep understanding of neurobiology, genetics, and psychopharmacology are, medical psychiatry embeds our work more broadly in all of human biology and requires the full breadth of our medical training.