User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Literature review highlights benefits of chemical peels for field AK treatment

including 88 patients.

AKs remain an ongoing health concern because of their potential to become malignant, and chemical peels are among the recommended options for field therapy, wrote Angela J. Jiang, MD, from the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and colleagues. “Although most dermatologists agree on the importance of field treatment, cryotherapy still remains the standard of care for treatment of AKs,” they noted, adding that the safety and efficacy of chemical peels for AK field therapy have not been well studied.

Chemical peels offer the benefit of a single treatment for patients, which eliminates the patient compliance issue needed for successful topical therapy, the researchers said. In fact, “patients report preference for the tolerability of treatment with chemical peels and the shorter downtime, compared with other field treatments,” they added.

In the study published in Dermatologic Surgery, they reviewed data from five prospective studies on the safety and efficacy of chemical peels as AK field treatments published from 1946 to March 2020 in the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database. Of the 151 articles on the use of chemical peels for AKs, the 5 studies met the criteria for their review.

One split-face study evaluated glycolic acid peels (published in 1998), two split-face studies evaluated a combination of Jessner’s and 35% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) peels (published in 1995 and 1997), and two randomized studies evaluated TCA peels alone (published in 2006 and 2016).

Overall, the studies showed efficacy of peels in reducing AK counts, with minimal adverse events. In the glycolic acid study, 70% glycolic acid plus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) yielded a 91.9% mean reduction in AKs at 6 months’ follow-up. A combination of Jessner’s solution and 35% TCA showed a significant reduction in AKs at 12 and at 32 months post treatment – a 75% reduction at 12 months in one study and 78% at 32 months in the other – similar to results achieved with 5-FU.

In studies of TCA alone, 30% TCA peels were similar in AK reduction (89%) to 5-FU (83%) and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (92%). In another TCA study, 35% TCA was less effective at AK reduction at 12 months, compared with aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), but the 35% peel was applied at a more superficial level than in the study of 30% TCA, the authors wrote.

Chemical peels also demonstrated effectiveness in preventing keratinocytic carcinomas, the researchers wrote. In the 30% TCA study, the rate of keratinocyte carcinoma development was 3.75-5.25 times lower in patients treated with 30% TCA peels, compared with 5-FU and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (CO2) after 5 years.

Chemical peels were well tolerated overall, although side effects varied among the studies. Patients in one study reported no side effects, while patients in other studies reported transient erythema and discomfort. In the study comparing TCA with PDT treatment, PDT was associated with greater pain, erythema, and pustules, the researchers wrote; however, patients treated with 35% TCA reported scarring.

From patients’ perspectives, chemical peels were preferable because of the single application, brief downtime, and minimal adverse effects. From the provider perspective, chemical peels are a more cost-effective way to treat large surface areas for AKs, compared with 5-FU or lasers, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small number of prospective studies and relatively small number of patients, they noted. “The small number of included studies is partially due to the lack of studies that performed AK counts before and after treatments,” they said. The dearth of literature on chemical peels for AKs may stem from lack of residency training on the use of peels, they added.

However, the results support the use of chemical peels as an effective option for field treatment of AKs, with the added benefits of convenience and cost-effectiveness for patients, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

including 88 patients.

AKs remain an ongoing health concern because of their potential to become malignant, and chemical peels are among the recommended options for field therapy, wrote Angela J. Jiang, MD, from the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and colleagues. “Although most dermatologists agree on the importance of field treatment, cryotherapy still remains the standard of care for treatment of AKs,” they noted, adding that the safety and efficacy of chemical peels for AK field therapy have not been well studied.

Chemical peels offer the benefit of a single treatment for patients, which eliminates the patient compliance issue needed for successful topical therapy, the researchers said. In fact, “patients report preference for the tolerability of treatment with chemical peels and the shorter downtime, compared with other field treatments,” they added.

In the study published in Dermatologic Surgery, they reviewed data from five prospective studies on the safety and efficacy of chemical peels as AK field treatments published from 1946 to March 2020 in the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database. Of the 151 articles on the use of chemical peels for AKs, the 5 studies met the criteria for their review.

One split-face study evaluated glycolic acid peels (published in 1998), two split-face studies evaluated a combination of Jessner’s and 35% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) peels (published in 1995 and 1997), and two randomized studies evaluated TCA peels alone (published in 2006 and 2016).

Overall, the studies showed efficacy of peels in reducing AK counts, with minimal adverse events. In the glycolic acid study, 70% glycolic acid plus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) yielded a 91.9% mean reduction in AKs at 6 months’ follow-up. A combination of Jessner’s solution and 35% TCA showed a significant reduction in AKs at 12 and at 32 months post treatment – a 75% reduction at 12 months in one study and 78% at 32 months in the other – similar to results achieved with 5-FU.

In studies of TCA alone, 30% TCA peels were similar in AK reduction (89%) to 5-FU (83%) and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (92%). In another TCA study, 35% TCA was less effective at AK reduction at 12 months, compared with aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), but the 35% peel was applied at a more superficial level than in the study of 30% TCA, the authors wrote.

Chemical peels also demonstrated effectiveness in preventing keratinocytic carcinomas, the researchers wrote. In the 30% TCA study, the rate of keratinocyte carcinoma development was 3.75-5.25 times lower in patients treated with 30% TCA peels, compared with 5-FU and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (CO2) after 5 years.

Chemical peels were well tolerated overall, although side effects varied among the studies. Patients in one study reported no side effects, while patients in other studies reported transient erythema and discomfort. In the study comparing TCA with PDT treatment, PDT was associated with greater pain, erythema, and pustules, the researchers wrote; however, patients treated with 35% TCA reported scarring.

From patients’ perspectives, chemical peels were preferable because of the single application, brief downtime, and minimal adverse effects. From the provider perspective, chemical peels are a more cost-effective way to treat large surface areas for AKs, compared with 5-FU or lasers, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small number of prospective studies and relatively small number of patients, they noted. “The small number of included studies is partially due to the lack of studies that performed AK counts before and after treatments,” they said. The dearth of literature on chemical peels for AKs may stem from lack of residency training on the use of peels, they added.

However, the results support the use of chemical peels as an effective option for field treatment of AKs, with the added benefits of convenience and cost-effectiveness for patients, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

including 88 patients.

AKs remain an ongoing health concern because of their potential to become malignant, and chemical peels are among the recommended options for field therapy, wrote Angela J. Jiang, MD, from the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and colleagues. “Although most dermatologists agree on the importance of field treatment, cryotherapy still remains the standard of care for treatment of AKs,” they noted, adding that the safety and efficacy of chemical peels for AK field therapy have not been well studied.

Chemical peels offer the benefit of a single treatment for patients, which eliminates the patient compliance issue needed for successful topical therapy, the researchers said. In fact, “patients report preference for the tolerability of treatment with chemical peels and the shorter downtime, compared with other field treatments,” they added.

In the study published in Dermatologic Surgery, they reviewed data from five prospective studies on the safety and efficacy of chemical peels as AK field treatments published from 1946 to March 2020 in the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database. Of the 151 articles on the use of chemical peels for AKs, the 5 studies met the criteria for their review.

One split-face study evaluated glycolic acid peels (published in 1998), two split-face studies evaluated a combination of Jessner’s and 35% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) peels (published in 1995 and 1997), and two randomized studies evaluated TCA peels alone (published in 2006 and 2016).

Overall, the studies showed efficacy of peels in reducing AK counts, with minimal adverse events. In the glycolic acid study, 70% glycolic acid plus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) yielded a 91.9% mean reduction in AKs at 6 months’ follow-up. A combination of Jessner’s solution and 35% TCA showed a significant reduction in AKs at 12 and at 32 months post treatment – a 75% reduction at 12 months in one study and 78% at 32 months in the other – similar to results achieved with 5-FU.

In studies of TCA alone, 30% TCA peels were similar in AK reduction (89%) to 5-FU (83%) and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (92%). In another TCA study, 35% TCA was less effective at AK reduction at 12 months, compared with aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), but the 35% peel was applied at a more superficial level than in the study of 30% TCA, the authors wrote.

Chemical peels also demonstrated effectiveness in preventing keratinocytic carcinomas, the researchers wrote. In the 30% TCA study, the rate of keratinocyte carcinoma development was 3.75-5.25 times lower in patients treated with 30% TCA peels, compared with 5-FU and carbon dioxide laser resurfacing (CO2) after 5 years.

Chemical peels were well tolerated overall, although side effects varied among the studies. Patients in one study reported no side effects, while patients in other studies reported transient erythema and discomfort. In the study comparing TCA with PDT treatment, PDT was associated with greater pain, erythema, and pustules, the researchers wrote; however, patients treated with 35% TCA reported scarring.

From patients’ perspectives, chemical peels were preferable because of the single application, brief downtime, and minimal adverse effects. From the provider perspective, chemical peels are a more cost-effective way to treat large surface areas for AKs, compared with 5-FU or lasers, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small number of prospective studies and relatively small number of patients, they noted. “The small number of included studies is partially due to the lack of studies that performed AK counts before and after treatments,” they said. The dearth of literature on chemical peels for AKs may stem from lack of residency training on the use of peels, they added.

However, the results support the use of chemical peels as an effective option for field treatment of AKs, with the added benefits of convenience and cost-effectiveness for patients, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

ACIP recommends universal HBV vaccination for adults under 60, expands recommendations for vaccines against orthopoxviruses and Ebola

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pfizer says its COVID-19 pill is highly effective

, according to the drug’s maker, Pfizer.

The drug -- called Paxlovid -- was 89% effective, compared to a placebo, at preventing hospitalization or death in patients with COVID-19 who were at high risk of severe complications. The company says it plans to ask the FDA to authorize the drug for emergency use.

The medication appears to work so well that Pfizer has stopped enrollment in the trial of the drug, which works by blocking an enzyme called a protease that the new coronavirus needs to make more copies of itself.

Stopping a clinical trial is a rare action that’s typically taken when a therapy appears to be very effective or clearly dangerous. In both those cases, it’s considered unethical to continue a clinical trial where people are randomly assigned either an active drug or a placebo, when safer or more effective options are available to them.

In this case, the company said in a news release that the move was recommended by an independent panel of advisers who are overseeing the trial, called a data safety monitoring committee, and done in consultation with the FDA.

“Today’s news is a real game-changer in the global efforts to halt the devastation of this pandemic,” said Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer chairman and chief executive officer. “These data suggest that our oral antiviral candidate, if approved or authorized by regulatory authorities, has the potential to save patients’ lives, reduce the severity of COVID-19 infections, and eliminate up to nine out of ten hospitalizations.”

In a randomized clinical trial that included more than 1,900 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 and were at risk for having severe complications for their infections, those who received Paxlovid within 3 days of the start of their symptoms were 89% less likely to be hospitalized than those who got a placebo pill -- three patients out of 389 who got the drug were hospitalized, compared with 27 out of 385 who got the placebo. Among patients who got the drug within 5 days of the start of their symptoms, six out of 607 were hospitalized within 28 days, compared to 41 out of 612 who got the placebo.

There were no deaths over the course of a month in patients who took Paxlovid, but 10 deaths in the group that got the placebo.

The news comes on the heels of an announcement in October by the drug company Merck that its experimental antiviral pill, molnupiravir, reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients with mild to moderate COVID, compared to a placebo.

The United Kingdom became the first country to authorize the use of molnupiravir, which is brand-named Lagevrio.

Stephen Griffin, PhD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Leeds, hailed the success of both new antiviral pills.

“They both demonstrate that, with appropriate investment, the development of bespoke direct-acting antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV2 was eminently feasible and has ultimately proven far more successful than repurposing other drugs with questionable antiviral effects,” said Dr. Griffin, who was not involved in the development of either drug.

“The success of these antivirals potentially marks a new era in our ability to prevent the severe consequences of SARS-CoV2 infection, and is also a vital element for the care of clinically vulnerable people who may be unable to either receive or respond to vaccines,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to the drug’s maker, Pfizer.

The drug -- called Paxlovid -- was 89% effective, compared to a placebo, at preventing hospitalization or death in patients with COVID-19 who were at high risk of severe complications. The company says it plans to ask the FDA to authorize the drug for emergency use.

The medication appears to work so well that Pfizer has stopped enrollment in the trial of the drug, which works by blocking an enzyme called a protease that the new coronavirus needs to make more copies of itself.

Stopping a clinical trial is a rare action that’s typically taken when a therapy appears to be very effective or clearly dangerous. In both those cases, it’s considered unethical to continue a clinical trial where people are randomly assigned either an active drug or a placebo, when safer or more effective options are available to them.

In this case, the company said in a news release that the move was recommended by an independent panel of advisers who are overseeing the trial, called a data safety monitoring committee, and done in consultation with the FDA.

“Today’s news is a real game-changer in the global efforts to halt the devastation of this pandemic,” said Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer chairman and chief executive officer. “These data suggest that our oral antiviral candidate, if approved or authorized by regulatory authorities, has the potential to save patients’ lives, reduce the severity of COVID-19 infections, and eliminate up to nine out of ten hospitalizations.”

In a randomized clinical trial that included more than 1,900 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 and were at risk for having severe complications for their infections, those who received Paxlovid within 3 days of the start of their symptoms were 89% less likely to be hospitalized than those who got a placebo pill -- three patients out of 389 who got the drug were hospitalized, compared with 27 out of 385 who got the placebo. Among patients who got the drug within 5 days of the start of their symptoms, six out of 607 were hospitalized within 28 days, compared to 41 out of 612 who got the placebo.

There were no deaths over the course of a month in patients who took Paxlovid, but 10 deaths in the group that got the placebo.

The news comes on the heels of an announcement in October by the drug company Merck that its experimental antiviral pill, molnupiravir, reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients with mild to moderate COVID, compared to a placebo.

The United Kingdom became the first country to authorize the use of molnupiravir, which is brand-named Lagevrio.

Stephen Griffin, PhD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Leeds, hailed the success of both new antiviral pills.

“They both demonstrate that, with appropriate investment, the development of bespoke direct-acting antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV2 was eminently feasible and has ultimately proven far more successful than repurposing other drugs with questionable antiviral effects,” said Dr. Griffin, who was not involved in the development of either drug.

“The success of these antivirals potentially marks a new era in our ability to prevent the severe consequences of SARS-CoV2 infection, and is also a vital element for the care of clinically vulnerable people who may be unable to either receive or respond to vaccines,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to the drug’s maker, Pfizer.

The drug -- called Paxlovid -- was 89% effective, compared to a placebo, at preventing hospitalization or death in patients with COVID-19 who were at high risk of severe complications. The company says it plans to ask the FDA to authorize the drug for emergency use.

The medication appears to work so well that Pfizer has stopped enrollment in the trial of the drug, which works by blocking an enzyme called a protease that the new coronavirus needs to make more copies of itself.

Stopping a clinical trial is a rare action that’s typically taken when a therapy appears to be very effective or clearly dangerous. In both those cases, it’s considered unethical to continue a clinical trial where people are randomly assigned either an active drug or a placebo, when safer or more effective options are available to them.

In this case, the company said in a news release that the move was recommended by an independent panel of advisers who are overseeing the trial, called a data safety monitoring committee, and done in consultation with the FDA.

“Today’s news is a real game-changer in the global efforts to halt the devastation of this pandemic,” said Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer chairman and chief executive officer. “These data suggest that our oral antiviral candidate, if approved or authorized by regulatory authorities, has the potential to save patients’ lives, reduce the severity of COVID-19 infections, and eliminate up to nine out of ten hospitalizations.”

In a randomized clinical trial that included more than 1,900 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 and were at risk for having severe complications for their infections, those who received Paxlovid within 3 days of the start of their symptoms were 89% less likely to be hospitalized than those who got a placebo pill -- three patients out of 389 who got the drug were hospitalized, compared with 27 out of 385 who got the placebo. Among patients who got the drug within 5 days of the start of their symptoms, six out of 607 were hospitalized within 28 days, compared to 41 out of 612 who got the placebo.

There were no deaths over the course of a month in patients who took Paxlovid, but 10 deaths in the group that got the placebo.

The news comes on the heels of an announcement in October by the drug company Merck that its experimental antiviral pill, molnupiravir, reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients with mild to moderate COVID, compared to a placebo.

The United Kingdom became the first country to authorize the use of molnupiravir, which is brand-named Lagevrio.

Stephen Griffin, PhD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Leeds, hailed the success of both new antiviral pills.

“They both demonstrate that, with appropriate investment, the development of bespoke direct-acting antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV2 was eminently feasible and has ultimately proven far more successful than repurposing other drugs with questionable antiviral effects,” said Dr. Griffin, who was not involved in the development of either drug.

“The success of these antivirals potentially marks a new era in our ability to prevent the severe consequences of SARS-CoV2 infection, and is also a vital element for the care of clinically vulnerable people who may be unable to either receive or respond to vaccines,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

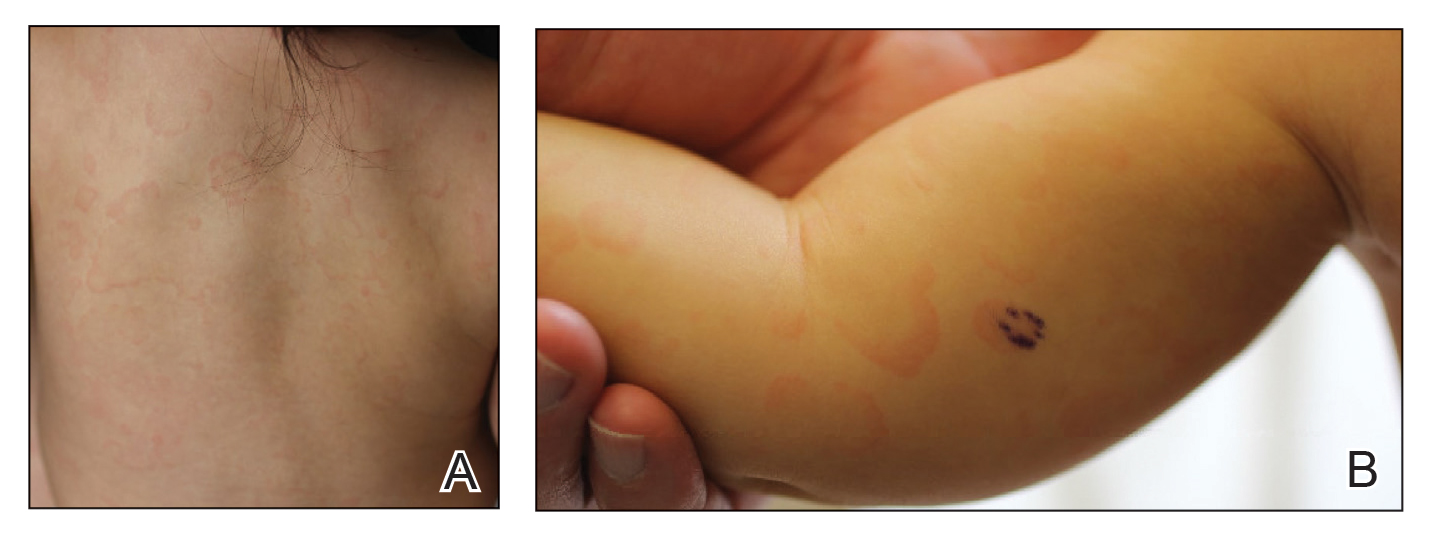

Linear Violaceous Papules in a Child

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

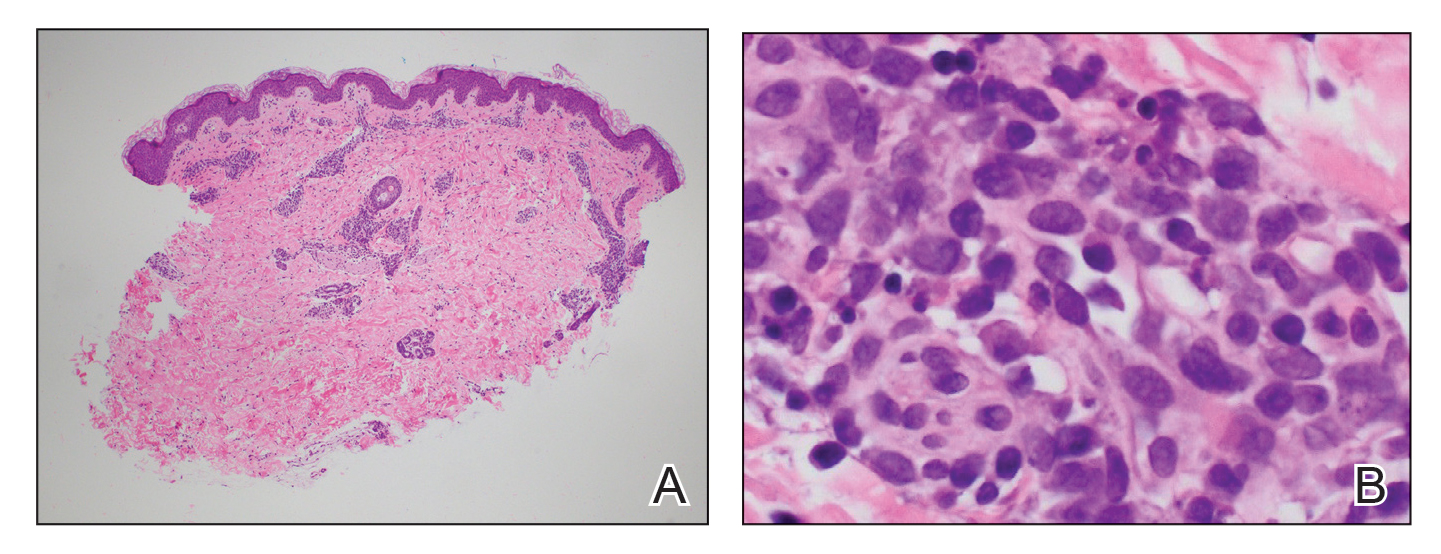

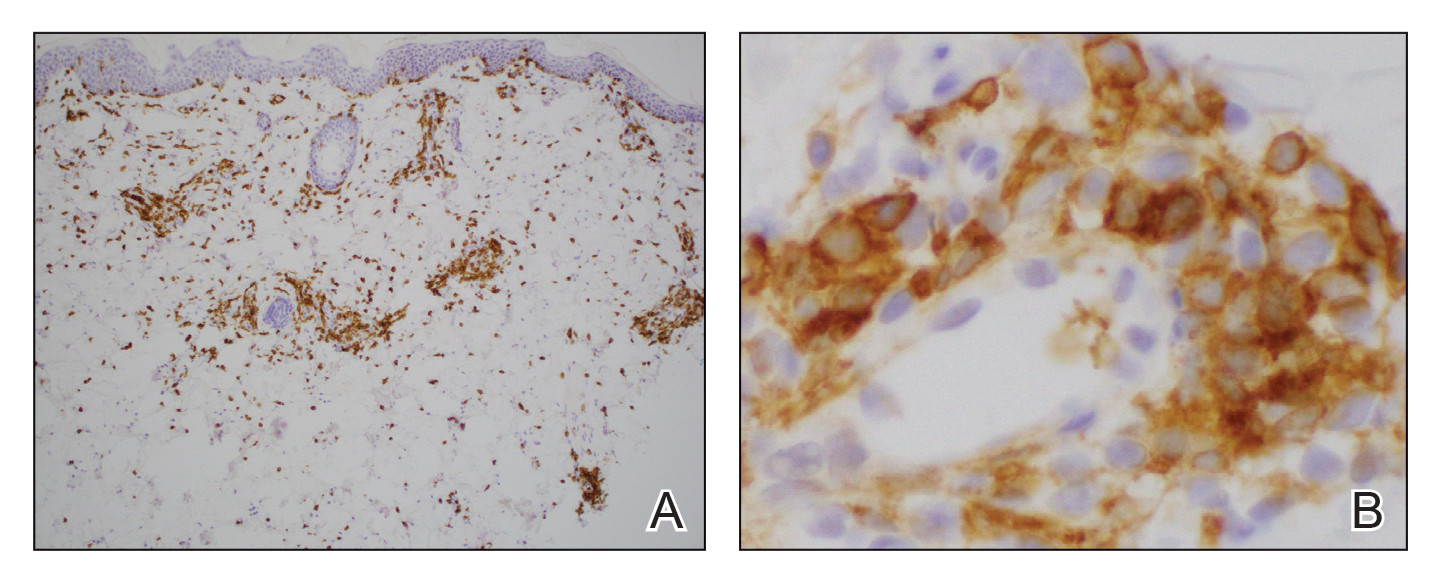

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

The Diagnosis: Linear Lichen Planus

The patient was clinically diagnosed with linear lichen planus and was started on betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% applied once daily with improvement in both the pruritus and appearance at 4-month follow-up. A biopsy was deferred based on the parents’ wishes.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder involving the skin and oral mucosa. Cutaneous lichen planus classically presents as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with overlying fine white or grey lines known as Wickham striae.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially in patients with darker skin tones. Expected histologic findings include orthokeratosis, apoptotic keratinocytes, and bandlike lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction.1

An estimated 5% of cases of cutaneous lichen planus occur in children.2 A study of 316 children with lichen planus demonstrated that the classic morphology remained the most common presentation, while the linear variant was present in only 6.9% of pediatric cases.3 Linear lichen planus appears to be more common among children than adults. A study of 36 pediatric cases showed a greater representation of lichen planus in Black children (67% affected vs 21% cohort).2

Cutaneous lichen planus often clears spontaneously in approximately 1 year.4 Treatment in children primarily is focused on shortening the time to resolution and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids as firstline therapy.3,4 Oral corticosteroids have a faster clinical response; greater efficacy; and more effectively prevent residual hyperpigmentation, which is especially relevant in individuals with darker skin.3 Nonetheless, oral corticosteroids are considered a second-line treatment due to their unfavorable side-effect profile. Additional treatment options include oral aromatic retinoids (acitretin) and phototherapy.3

Incontinentia pigmenti is characterized by a defect in the inhibitor of nuclear factor–κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG, gene on the X chromosome. Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males; in females, it leads to ectodermal dysplasia associated with skin findings in a blaschkoid distribution occurring in 4 stages.5 The verrucous stage is preceded by the vesicular stage and expected to occur within the first few months of life, making it unlikely in our 5-year-old patient. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually occurs in children younger than 5 years and is characterized by psoriasiform papules coalescing into a plaque with substantial scale instead of Wickham striae, as seen in our patient.6 Lichen striatus consists of smaller, pink to flesh-colored papules that rarely are pruritic.7 It is more common among atopic individuals and is associated with postinflammatory hypopigmentation.8 Linear psoriasis presents similarly to inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, with greater erythema and scale compared to the fine lacy Wickham striae that were seen in our patient.8

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Walton KE, Bowers EV, Drolet BA, et al. Childhood lichen planus: demographics of a U.S. population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-38.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN. Lichen planus in childhood: a series of 316 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:59-67.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:E45-E52.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell CJ. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

- Payette MJ, Weston G, Humphrey S, et al. Lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:631-643.

- Moss C, Browne F. Mosaicism and linear lesions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1894-1916.

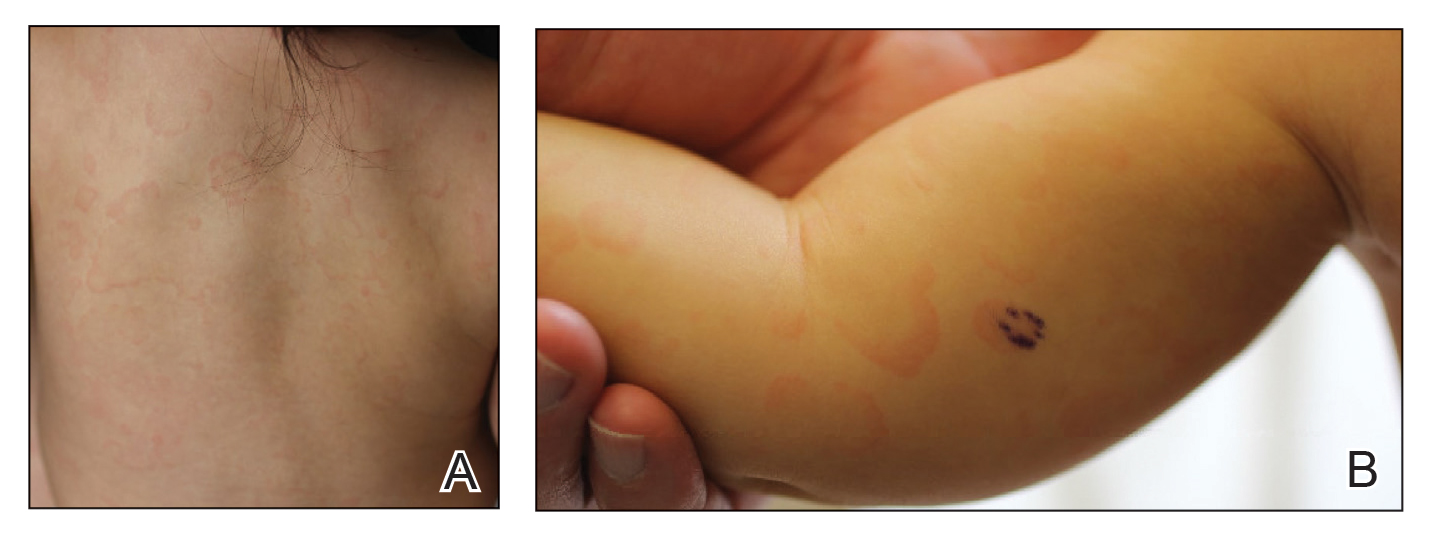

A 5-year-old Black girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a stable pruritic eruption on the right leg of 1 month’s duration. Over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream was applied for 3 days with no response. Physical examination revealed grouped, flat-topped, violaceous papules coalescing into plaques with overlying lacy white striae along the right lower leg, wrapping around to the right dorsal foot in a blaschkoid distribution. The patient was otherwise healthy and up-to-date on immunizations and had an unremarkable birth history.

Alopecia tied to a threefold increased risk for dementia

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Update on the Pediatric Dermatology Workforce Shortage

Pediatric dermatology is a relatively young subspecialty. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) was established in 1975, followed by the creation of the journal Pediatric Dermatology in 1982 and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Dermatology in 1986.1 In 2000, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) officially recognized pediatric dermatology as a unique subspecialty of the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). During that time, informal fellowship experiences emerged, and formal 1-year training programs approved by the ABD evolved by 2006. A subspecialty certification examination was created and has been administered every other year since 2004.1 Data provided by the SPD indicate that approximately 431 US dermatologists have passed the ABD’s pediatric dermatology board certification examination thus far (unpublished data, September 2021).

In 1986, the first systematic evaluation of the US pediatric dermatology workforce revealed a total of 57 practicing pediatric dermatologists and concluded that job opportunities appeared to be limited at that time.2 Since then, the demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to grow steadily, and the number of board-certified pediatric dermatologists practicing in the United States has increased to at least 317 per data from a 2020 survey.3 However, given that there are more than 11,000 board-certified dermatologists in the United States, there continues to be a severe shortage of pediatric dermatologists.1

Increased Demand for Pediatric Dermatologists

Approximately 10% to 30% of almost 200 million annual outpatient pediatric primary care visits involve a skin concern. Although many of these problems can be handled by primary care physicians, more than 80% of pediatricians report having difficulty accessing dermatology services for their patients.4 In surveys of pediatricians, pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate but has consistently ranked third among the specialties deemed most difficult to access.5-7 In addition, it is not uncommon for the wait time to see a pediatric dermatologist to be 6 weeks or longer.5,8

Recent population data estimate that there are 73 million children living in the United States.9 If there are roughly 317 practicing board-certified pediatric dermatologists, that translates into approximately 4.3 pediatric dermatologists per million children. This number is far smaller than the 4 general dermatologists per 100,000 individuals recommended by Glazer et al10 in 2017. To meet this suggested ratio goal, the workforce of pediatric dermatologists would have to increase to 2920. In addition to this severe workforce shortage, there is an additional problem with geographic maldistribution of pediatric dermatologists. More than 98% of pediatric dermatologists practice in metropolitan areas. At least 8 states and 95% of counties have no pediatric dermatologist, and there are no pediatric dermatologists practicing in rural counties.9 This disparity has considerable implications for barriers to care and lack of access for children living in underserved areas. Suggestions for attracting pediatric dermatologists to practice in these areas have included loan forgiveness programs as well as remote mentorship programs to provide professional support.8,9

Training in Pediatrics

There currently are 38 ABD-approved pediatric dermatology fellowship training programs in the United States. Beginning in 2009, pediatric dermatology fellowship programs have participated in the SF Match program. Data provided by the SPD show that, since 2012, up to 27 programs have participated in the annual Match, offering a total number of positions ranging from 27 to 38; however, only 11 to 21 positions have been filled each year, leaving a large number of post-Match vacancies (unpublished data, September 2021).

Surveys have explored the reasons behind this lack of interest in pediatric dermatology training among dermatology residents. Factors that have been mentioned include lack of exposure and mentorship in medical school and residency, the financial hardship of an additional year of fellowship training, and historically lower salaries for pediatric dermatologists compared to general dermatologists.3,6

A 2004 survey revealed that more than 75% of dermatology department chairs believed it was important to have a pediatric dermatologist on the faculty; however, at that time only 48% of dermatology programs reported having at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatology faculty member.11 By 2008, a follow-up survey showed an increase to 70% of dermatology training programs reporting at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatologist; however, 43% of departments still had at least 1 open position, and 76% of those programs shared that they had been searching for more than 1 year.2 Currently, the Accreditation Data System of the ACGME shows a total of 144 accredited US dermatology training programs. Of those, 117 programs have 1 or more board-certified pediatric dermatology faculty member, and 27 programs still have none (unpublished data, September 2021).

A shortage of pediatric dermatologists in training programs contributes to the lack of exposure and mentorship for medical students and residents during a critical time in professional development. Studies show that up to 91% of pediatric dermatologists decided to pursue training in pediatric dermatology during medical school, pediatrics residency, or dermatology residency. In one survey, 84% of respondents (N=109) cited early mentorship as the most important factor in their decision to pursue pediatric dermatology.6

A lack of pediatric dermatologists also results in suboptimal dermatology training for residents who care for children in primary care specialties, including pediatrics, combined internal medicine and pediatrics, and family practice. Multiple surveys have shown that many pediatricians feel they received inadequate training in dermatology during residency. Up to 38% have cited a need for more pediatric dermatology education (N=755).5,6 In addition, studies show a wide disparity in diagnostic accuracy between dermatologists and pediatricians, with one concluding that more than one-third of referrals to pediatric dermatologists were initially misdiagnosed and/or incorrectly treated.5,7

Recruitment Efforts for Pediatric Dermatologists

There are multiple strategies for recruiting trainees into the pediatric dermatology workforce. First, given the importance of early exposure to the field and role models/mentors, pediatric dermatologists must take advantage of every opportunity to interact with medical students and residents. They can share their genuine enthusiasm and love for the specialty while encouraging and supporting those who show interest. They also should seek opportunities for teaching, lecturing, and advising at every level of training. In addition, they can enhance visibility of the specialty by participating in career forums and/or assuming leadership roles within their departments or institutions.12 Another suggestion is for dermatology training programs to consider giving priority to qualified applicants who express sincere interest in pursuing pediatric dermatology training (including those who have already completed pediatrics residency). Although a 2008 survey revealed that 39% of dermatology residency programs (N=80) favored giving priority to applicants demonstrating interest in pediatric dermatology, others were against it, citing issues such as lack of funding for additional residency training, lack of pediatric dermatology mentors within the program, and an overall mistrust of applicants’ sincerity.2

Final Thoughts

The subspecialty of pediatric dermatology has experienced remarkable growth over the last 40 years; however, demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to outpace supply, resulting in a persistent and notable workforce shortage. Overall, the current supply of pediatric dermatologists can neither meet the clinical demands of the pediatric population nor fulfill academic needs of existing training programs. We must continue to develop novel strategies for increasing the pool of students and residents who are interested in pursuing careers in pediatric dermatology. Ultimately, we also must create incentives and develop tactics to address the geographic maldistribution that exists within the specialty.

- Prindaville B, Antaya R, Siegfried E. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12.

- Craiglow BG, Resneck JS, Lucky AW, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: perspectives from academia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:986-989.

- Ashrafzadeh S, Peters G, Brandling-Bennett H, et al. The geographic distribution of the US pediatric dermatologist workforce: a national cross-sectional study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:1098-1105.

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897.

- Prindaville B, Simon S, Horii K. Dermatology-related outpatient visits by children: implications for workforce and pediatric education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:228-229.

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim S, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-375.

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. The US pediatric dermatology workforce: an assessment of productivity and practice patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:825-829.

- Prindaville B, Horii K, Siegfried E, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:166-168.

- Ugwu-Dike P, Nambudiri V. Access as equity: addressing the distribution of the pediatric dermatology workforce [published online August 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14665

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Hester EJ, McNealy KM, Kelloff JN, et al. Demand outstrips supply of US pediatric dermatologists: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:431-434.

- Wright TS, Huang JT. Comment on “pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States”. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:177-178.

Pediatric dermatology is a relatively young subspecialty. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) was established in 1975, followed by the creation of the journal Pediatric Dermatology in 1982 and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Dermatology in 1986.1 In 2000, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) officially recognized pediatric dermatology as a unique subspecialty of the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). During that time, informal fellowship experiences emerged, and formal 1-year training programs approved by the ABD evolved by 2006. A subspecialty certification examination was created and has been administered every other year since 2004.1 Data provided by the SPD indicate that approximately 431 US dermatologists have passed the ABD’s pediatric dermatology board certification examination thus far (unpublished data, September 2021).

In 1986, the first systematic evaluation of the US pediatric dermatology workforce revealed a total of 57 practicing pediatric dermatologists and concluded that job opportunities appeared to be limited at that time.2 Since then, the demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to grow steadily, and the number of board-certified pediatric dermatologists practicing in the United States has increased to at least 317 per data from a 2020 survey.3 However, given that there are more than 11,000 board-certified dermatologists in the United States, there continues to be a severe shortage of pediatric dermatologists.1

Increased Demand for Pediatric Dermatologists

Approximately 10% to 30% of almost 200 million annual outpatient pediatric primary care visits involve a skin concern. Although many of these problems can be handled by primary care physicians, more than 80% of pediatricians report having difficulty accessing dermatology services for their patients.4 In surveys of pediatricians, pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate but has consistently ranked third among the specialties deemed most difficult to access.5-7 In addition, it is not uncommon for the wait time to see a pediatric dermatologist to be 6 weeks or longer.5,8

Recent population data estimate that there are 73 million children living in the United States.9 If there are roughly 317 practicing board-certified pediatric dermatologists, that translates into approximately 4.3 pediatric dermatologists per million children. This number is far smaller than the 4 general dermatologists per 100,000 individuals recommended by Glazer et al10 in 2017. To meet this suggested ratio goal, the workforce of pediatric dermatologists would have to increase to 2920. In addition to this severe workforce shortage, there is an additional problem with geographic maldistribution of pediatric dermatologists. More than 98% of pediatric dermatologists practice in metropolitan areas. At least 8 states and 95% of counties have no pediatric dermatologist, and there are no pediatric dermatologists practicing in rural counties.9 This disparity has considerable implications for barriers to care and lack of access for children living in underserved areas. Suggestions for attracting pediatric dermatologists to practice in these areas have included loan forgiveness programs as well as remote mentorship programs to provide professional support.8,9

Training in Pediatrics

There currently are 38 ABD-approved pediatric dermatology fellowship training programs in the United States. Beginning in 2009, pediatric dermatology fellowship programs have participated in the SF Match program. Data provided by the SPD show that, since 2012, up to 27 programs have participated in the annual Match, offering a total number of positions ranging from 27 to 38; however, only 11 to 21 positions have been filled each year, leaving a large number of post-Match vacancies (unpublished data, September 2021).

Surveys have explored the reasons behind this lack of interest in pediatric dermatology training among dermatology residents. Factors that have been mentioned include lack of exposure and mentorship in medical school and residency, the financial hardship of an additional year of fellowship training, and historically lower salaries for pediatric dermatologists compared to general dermatologists.3,6

A 2004 survey revealed that more than 75% of dermatology department chairs believed it was important to have a pediatric dermatologist on the faculty; however, at that time only 48% of dermatology programs reported having at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatology faculty member.11 By 2008, a follow-up survey showed an increase to 70% of dermatology training programs reporting at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatologist; however, 43% of departments still had at least 1 open position, and 76% of those programs shared that they had been searching for more than 1 year.2 Currently, the Accreditation Data System of the ACGME shows a total of 144 accredited US dermatology training programs. Of those, 117 programs have 1 or more board-certified pediatric dermatology faculty member, and 27 programs still have none (unpublished data, September 2021).

A shortage of pediatric dermatologists in training programs contributes to the lack of exposure and mentorship for medical students and residents during a critical time in professional development. Studies show that up to 91% of pediatric dermatologists decided to pursue training in pediatric dermatology during medical school, pediatrics residency, or dermatology residency. In one survey, 84% of respondents (N=109) cited early mentorship as the most important factor in their decision to pursue pediatric dermatology.6

A lack of pediatric dermatologists also results in suboptimal dermatology training for residents who care for children in primary care specialties, including pediatrics, combined internal medicine and pediatrics, and family practice. Multiple surveys have shown that many pediatricians feel they received inadequate training in dermatology during residency. Up to 38% have cited a need for more pediatric dermatology education (N=755).5,6 In addition, studies show a wide disparity in diagnostic accuracy between dermatologists and pediatricians, with one concluding that more than one-third of referrals to pediatric dermatologists were initially misdiagnosed and/or incorrectly treated.5,7

Recruitment Efforts for Pediatric Dermatologists