User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Feds launch COVID-19 worker vaccine mandates

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

James Bond taken down by an epidemiologist

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

Phototoxicity Secondary to Home Fireplace Exposure After Photodynamic Therapy for Actinic Keratosis

To the Editor:

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for actinic keratosis (AK). It also commonly is administered off label for basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, photoaging, and acne vulgaris and is being investigated for other applications.1,2 In the context of treating AK, the mechanism employed in PDT most commonly involves the application of exogenous aminolevulinic acid (ALA), which is metabolized to the endogenous photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in skin cells by enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway.3 The preferential uptake of ALA and conversion to PpIX is due to the altered and increased permeability of abnormal keratin layers of aging, sun-damaged cells, and skin tumors. Selectivity of ALA also occurs due to the preferential intracellular accumulation of PpIX in proliferating, relatively iron–deficient, precancerous and cancerous cells. The therapeutic effect is achieved with light exposure to blue light wavelength at 417 nm and corresponds to the excitation peak of PpIX,4 which activates PpIX and forms reactive oxygen species in the presence of oxygen that ultimately cause cell necrosis and apoptosis.5 Because it takes approximately 24 hours for PpIX to be completely metabolized from the skin, patients are counseled to avoid sun or artificial light exposure in the first 24 hours post-PDT, regardless of the indication, to avoid a severe phototoxic reaction.3,6,7 Although it is normal and desirable for patients to experience some form of a phototoxic reaction, which may include erythema, edema, crusting, vesiculation, or erosion in most patients, these types of reactions most often are secondary to the intended exposure and incidental natural or artificial light exposures.6 We report a case of a severe phototoxic reaction in which a patient experienced painful erythema and purulence on the left side of the chin after being within an arm’s length of a flame in a fireplace following PDT treatment.

A 59-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for his second of 3 PDT sessions to treat AKs on the face. He had a history of a basal cell carcinoma on the left nasolabial fold that previously was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and melanoma on the left ear that was previously treated with excision. The patient received the initial PDT session 1 month prior and experienced a mild reaction with minimal redness and peeling that resolved in 4 to 5 days. For the second treatment, per standard protocol at our clinic, ALA was applied to the face, after which the patient incubated for 1 hour prior to blue light exposure (mean [SD] peak output of 417 [5] nm for 1000 seconds and 10 J/cm2).

After blue light exposure, broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 47) was applied to our patient’s face, and he wore a wide-brimmed hat upon leaving the clinic and walking to his car. Similar to the first PDT session 1 month prior, he experienced minimal pain immediately after treatment. Once home and approximately 4 to 5 hours after PDT, he tended to a fire using his left hand and leaned into the fireplace with the left side of his face, which was within an arm’s length of the flames. Although his skin did not come in direct contact with the flames, the brief 2- to 3-minute exposure to the flame’s light and heat produced an immediate intense burning pain that the patient likened to the pain of blue light exposure. Within 24 hours, he developed a severe inflammatory reaction that included erythema, edema, desquamation, and pustules on the left side of the chin and cheek that produced a purulent discharge (Figure). The purulence resolved the next day; however, the other clinical manifestations persisted for 1 week. Despite the discomfort and symptoms, our patient did not seek medical attention and instead managed his symptoms conservatively with cold compresses. Although he noticed an overall subjective improvement in the appearance of his face after this second treatment, he received a third treatment with PDT approximately 1 month later, which resulted in a response that was similar to his first visit.

Photodynamic therapy is an increasingly accepted treatment modality for a plethora of benign and malignant dermatologic conditions. Although blue and red light are the most common light sources utilized with PDT because their wavelengths (404–420 nm and 635 nm, respectively) correspond to the excitation peaks of photosensitizers, alternative light sources increasingly are being explored. There is increasing interest in utilizing infrared (IR) light sources (700–1,000,000 nm) to penetrate deeper into the skin in the treatment of precancerous and cancerous lesions. Exposure to IR radiation is known to raise skin temperature via inside-out dermal water absorption and is thought to be useful in PDT-ALA by promoting ALA penetration and its conversion to PpIX.8 In a randomized controlled trial by Giehl et al,9 visible light plus water-filtered IR-A light was shown to produce considerably less pain in ALA-PDT compared to placebo, though efficacy was not statistically affected. There are burgeoning trials examining the role of IR in treating dermatologic conditions such as acne, but research is still needed on ALA-PDT activated by IR radiation to target AKs.

Although the PDT side-effect profile of phototoxicity, dyspigmentation, and hypersensitivity is well documented, phototoxicity secondary to flame exposure is rare. In our patient, the synergistic effect of light and heat produced an exuberant phototoxic reaction. As the applications for PDT continue to broaden, this case may represent the importance of addressing additional precautions, such as avoiding open flames in the house or while camping, in the PDT aftercare instructions to maximize patient safety.

- Fritsch C, Ruzicka T. Fluorescence diagnosis and photodynamic therapy in dermatology from experimental state to clinic standard methods. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25:425-439.

- Lang K, Schulte KW, Ruzicka T, et al. Aminolevulinic acid (Levulan)in photodynamic therapy of actinic keratoses. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2, 5.

- Kennedy JC, Pottier RH. Endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992;14:275-292.

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163.

- Gad F, Viau G, Boushira M, et al. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid induces apoptosis and caspase activation in malignant T cells. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:8-13.

- Piacquadio DJ, Chen DM, Farber HF, et al. Photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid topical solution and visible blue light in the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses of the face and scalp: investigator-blinded, phase 3, multicenter trials. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:41-46.

- Rhodes LE, Tsoukas MM, Anderson RR, et al. Iontophoretic delivery of ALA provides a quantitative model for ALA pharmacokinetics and PpIX phototoxicity in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:87-91.

- Dover JS, Phillips TJ, Arndt KA. Cutaneous effects and therapeutic uses of heat with emphasis on infrared radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):278-286.

- Giehl KA, Kriz M, Grahovac M, et al. A controlled trial of photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis comparing different red light sources. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:335-341.

To the Editor:

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for actinic keratosis (AK). It also commonly is administered off label for basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, photoaging, and acne vulgaris and is being investigated for other applications.1,2 In the context of treating AK, the mechanism employed in PDT most commonly involves the application of exogenous aminolevulinic acid (ALA), which is metabolized to the endogenous photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in skin cells by enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway.3 The preferential uptake of ALA and conversion to PpIX is due to the altered and increased permeability of abnormal keratin layers of aging, sun-damaged cells, and skin tumors. Selectivity of ALA also occurs due to the preferential intracellular accumulation of PpIX in proliferating, relatively iron–deficient, precancerous and cancerous cells. The therapeutic effect is achieved with light exposure to blue light wavelength at 417 nm and corresponds to the excitation peak of PpIX,4 which activates PpIX and forms reactive oxygen species in the presence of oxygen that ultimately cause cell necrosis and apoptosis.5 Because it takes approximately 24 hours for PpIX to be completely metabolized from the skin, patients are counseled to avoid sun or artificial light exposure in the first 24 hours post-PDT, regardless of the indication, to avoid a severe phototoxic reaction.3,6,7 Although it is normal and desirable for patients to experience some form of a phototoxic reaction, which may include erythema, edema, crusting, vesiculation, or erosion in most patients, these types of reactions most often are secondary to the intended exposure and incidental natural or artificial light exposures.6 We report a case of a severe phototoxic reaction in which a patient experienced painful erythema and purulence on the left side of the chin after being within an arm’s length of a flame in a fireplace following PDT treatment.

A 59-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for his second of 3 PDT sessions to treat AKs on the face. He had a history of a basal cell carcinoma on the left nasolabial fold that previously was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and melanoma on the left ear that was previously treated with excision. The patient received the initial PDT session 1 month prior and experienced a mild reaction with minimal redness and peeling that resolved in 4 to 5 days. For the second treatment, per standard protocol at our clinic, ALA was applied to the face, after which the patient incubated for 1 hour prior to blue light exposure (mean [SD] peak output of 417 [5] nm for 1000 seconds and 10 J/cm2).

After blue light exposure, broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 47) was applied to our patient’s face, and he wore a wide-brimmed hat upon leaving the clinic and walking to his car. Similar to the first PDT session 1 month prior, he experienced minimal pain immediately after treatment. Once home and approximately 4 to 5 hours after PDT, he tended to a fire using his left hand and leaned into the fireplace with the left side of his face, which was within an arm’s length of the flames. Although his skin did not come in direct contact with the flames, the brief 2- to 3-minute exposure to the flame’s light and heat produced an immediate intense burning pain that the patient likened to the pain of blue light exposure. Within 24 hours, he developed a severe inflammatory reaction that included erythema, edema, desquamation, and pustules on the left side of the chin and cheek that produced a purulent discharge (Figure). The purulence resolved the next day; however, the other clinical manifestations persisted for 1 week. Despite the discomfort and symptoms, our patient did not seek medical attention and instead managed his symptoms conservatively with cold compresses. Although he noticed an overall subjective improvement in the appearance of his face after this second treatment, he received a third treatment with PDT approximately 1 month later, which resulted in a response that was similar to his first visit.

Photodynamic therapy is an increasingly accepted treatment modality for a plethora of benign and malignant dermatologic conditions. Although blue and red light are the most common light sources utilized with PDT because their wavelengths (404–420 nm and 635 nm, respectively) correspond to the excitation peaks of photosensitizers, alternative light sources increasingly are being explored. There is increasing interest in utilizing infrared (IR) light sources (700–1,000,000 nm) to penetrate deeper into the skin in the treatment of precancerous and cancerous lesions. Exposure to IR radiation is known to raise skin temperature via inside-out dermal water absorption and is thought to be useful in PDT-ALA by promoting ALA penetration and its conversion to PpIX.8 In a randomized controlled trial by Giehl et al,9 visible light plus water-filtered IR-A light was shown to produce considerably less pain in ALA-PDT compared to placebo, though efficacy was not statistically affected. There are burgeoning trials examining the role of IR in treating dermatologic conditions such as acne, but research is still needed on ALA-PDT activated by IR radiation to target AKs.

Although the PDT side-effect profile of phototoxicity, dyspigmentation, and hypersensitivity is well documented, phototoxicity secondary to flame exposure is rare. In our patient, the synergistic effect of light and heat produced an exuberant phototoxic reaction. As the applications for PDT continue to broaden, this case may represent the importance of addressing additional precautions, such as avoiding open flames in the house or while camping, in the PDT aftercare instructions to maximize patient safety.

To the Editor:

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for actinic keratosis (AK). It also commonly is administered off label for basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, photoaging, and acne vulgaris and is being investigated for other applications.1,2 In the context of treating AK, the mechanism employed in PDT most commonly involves the application of exogenous aminolevulinic acid (ALA), which is metabolized to the endogenous photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in skin cells by enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway.3 The preferential uptake of ALA and conversion to PpIX is due to the altered and increased permeability of abnormal keratin layers of aging, sun-damaged cells, and skin tumors. Selectivity of ALA also occurs due to the preferential intracellular accumulation of PpIX in proliferating, relatively iron–deficient, precancerous and cancerous cells. The therapeutic effect is achieved with light exposure to blue light wavelength at 417 nm and corresponds to the excitation peak of PpIX,4 which activates PpIX and forms reactive oxygen species in the presence of oxygen that ultimately cause cell necrosis and apoptosis.5 Because it takes approximately 24 hours for PpIX to be completely metabolized from the skin, patients are counseled to avoid sun or artificial light exposure in the first 24 hours post-PDT, regardless of the indication, to avoid a severe phototoxic reaction.3,6,7 Although it is normal and desirable for patients to experience some form of a phototoxic reaction, which may include erythema, edema, crusting, vesiculation, or erosion in most patients, these types of reactions most often are secondary to the intended exposure and incidental natural or artificial light exposures.6 We report a case of a severe phototoxic reaction in which a patient experienced painful erythema and purulence on the left side of the chin after being within an arm’s length of a flame in a fireplace following PDT treatment.

A 59-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for his second of 3 PDT sessions to treat AKs on the face. He had a history of a basal cell carcinoma on the left nasolabial fold that previously was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and melanoma on the left ear that was previously treated with excision. The patient received the initial PDT session 1 month prior and experienced a mild reaction with minimal redness and peeling that resolved in 4 to 5 days. For the second treatment, per standard protocol at our clinic, ALA was applied to the face, after which the patient incubated for 1 hour prior to blue light exposure (mean [SD] peak output of 417 [5] nm for 1000 seconds and 10 J/cm2).

After blue light exposure, broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 47) was applied to our patient’s face, and he wore a wide-brimmed hat upon leaving the clinic and walking to his car. Similar to the first PDT session 1 month prior, he experienced minimal pain immediately after treatment. Once home and approximately 4 to 5 hours after PDT, he tended to a fire using his left hand and leaned into the fireplace with the left side of his face, which was within an arm’s length of the flames. Although his skin did not come in direct contact with the flames, the brief 2- to 3-minute exposure to the flame’s light and heat produced an immediate intense burning pain that the patient likened to the pain of blue light exposure. Within 24 hours, he developed a severe inflammatory reaction that included erythema, edema, desquamation, and pustules on the left side of the chin and cheek that produced a purulent discharge (Figure). The purulence resolved the next day; however, the other clinical manifestations persisted for 1 week. Despite the discomfort and symptoms, our patient did not seek medical attention and instead managed his symptoms conservatively with cold compresses. Although he noticed an overall subjective improvement in the appearance of his face after this second treatment, he received a third treatment with PDT approximately 1 month later, which resulted in a response that was similar to his first visit.

Photodynamic therapy is an increasingly accepted treatment modality for a plethora of benign and malignant dermatologic conditions. Although blue and red light are the most common light sources utilized with PDT because their wavelengths (404–420 nm and 635 nm, respectively) correspond to the excitation peaks of photosensitizers, alternative light sources increasingly are being explored. There is increasing interest in utilizing infrared (IR) light sources (700–1,000,000 nm) to penetrate deeper into the skin in the treatment of precancerous and cancerous lesions. Exposure to IR radiation is known to raise skin temperature via inside-out dermal water absorption and is thought to be useful in PDT-ALA by promoting ALA penetration and its conversion to PpIX.8 In a randomized controlled trial by Giehl et al,9 visible light plus water-filtered IR-A light was shown to produce considerably less pain in ALA-PDT compared to placebo, though efficacy was not statistically affected. There are burgeoning trials examining the role of IR in treating dermatologic conditions such as acne, but research is still needed on ALA-PDT activated by IR radiation to target AKs.

Although the PDT side-effect profile of phototoxicity, dyspigmentation, and hypersensitivity is well documented, phototoxicity secondary to flame exposure is rare. In our patient, the synergistic effect of light and heat produced an exuberant phototoxic reaction. As the applications for PDT continue to broaden, this case may represent the importance of addressing additional precautions, such as avoiding open flames in the house or while camping, in the PDT aftercare instructions to maximize patient safety.

- Fritsch C, Ruzicka T. Fluorescence diagnosis and photodynamic therapy in dermatology from experimental state to clinic standard methods. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25:425-439.

- Lang K, Schulte KW, Ruzicka T, et al. Aminolevulinic acid (Levulan)in photodynamic therapy of actinic keratoses. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2, 5.

- Kennedy JC, Pottier RH. Endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992;14:275-292.

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163.

- Gad F, Viau G, Boushira M, et al. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid induces apoptosis and caspase activation in malignant T cells. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:8-13.

- Piacquadio DJ, Chen DM, Farber HF, et al. Photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid topical solution and visible blue light in the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses of the face and scalp: investigator-blinded, phase 3, multicenter trials. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:41-46.

- Rhodes LE, Tsoukas MM, Anderson RR, et al. Iontophoretic delivery of ALA provides a quantitative model for ALA pharmacokinetics and PpIX phototoxicity in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:87-91.

- Dover JS, Phillips TJ, Arndt KA. Cutaneous effects and therapeutic uses of heat with emphasis on infrared radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):278-286.

- Giehl KA, Kriz M, Grahovac M, et al. A controlled trial of photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis comparing different red light sources. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:335-341.

- Fritsch C, Ruzicka T. Fluorescence diagnosis and photodynamic therapy in dermatology from experimental state to clinic standard methods. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25:425-439.

- Lang K, Schulte KW, Ruzicka T, et al. Aminolevulinic acid (Levulan)in photodynamic therapy of actinic keratoses. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2, 5.

- Kennedy JC, Pottier RH. Endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992;14:275-292.

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163.

- Gad F, Viau G, Boushira M, et al. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid induces apoptosis and caspase activation in malignant T cells. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:8-13.

- Piacquadio DJ, Chen DM, Farber HF, et al. Photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid topical solution and visible blue light in the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses of the face and scalp: investigator-blinded, phase 3, multicenter trials. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:41-46.

- Rhodes LE, Tsoukas MM, Anderson RR, et al. Iontophoretic delivery of ALA provides a quantitative model for ALA pharmacokinetics and PpIX phototoxicity in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:87-91.

- Dover JS, Phillips TJ, Arndt KA. Cutaneous effects and therapeutic uses of heat with emphasis on infrared radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):278-286.

- Giehl KA, Kriz M, Grahovac M, et al. A controlled trial of photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis comparing different red light sources. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:335-341.

Practice Points

- As the applications of photodynamic therapy (PDT) in dermatology continue to expand, it is imperative for providers and patients alike to be knowledgeable with aftercare instructions and potential adverse effects.

- Avoid open flames in the house or while camping following PDT to maximize patient safety and prevent phototoxicity.

Early Pilomatrix Carcinoma: A Case Report With Emphasis on Molecular Pathology and Review of the Literature

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare adnexal tumor with origin from the germinative matrical cells of the hair follicle. Clinically, it presents as a solitary lesion commonly found in the head and neck region as well as the upper back. The tumors cannot be distinguished by their clinical appearance only and frequently are mistaken for cysts. Histopathologic examination provides the definitive diagnosis in most cases. These carcinomas are aggressive neoplasms with a high probability of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Assessment of the Wnt signaling pathway components such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2) potentially can be used for diagnostic purposes and targeted therapy.

We report a rare and unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes. We review the molecular pathology and pathogenesis of these carcinomas as well as the significance of early diagnosis.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man with a history of extensive sun exposure presented with a 1-cm, raised, rapidly growing, slightly irregular, purple lesion on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration with tendency to bleed. He did not have a history of skin cancers and was otherwise healthy. Excision was recommended due to the progressive and rapid growth of the lesion.

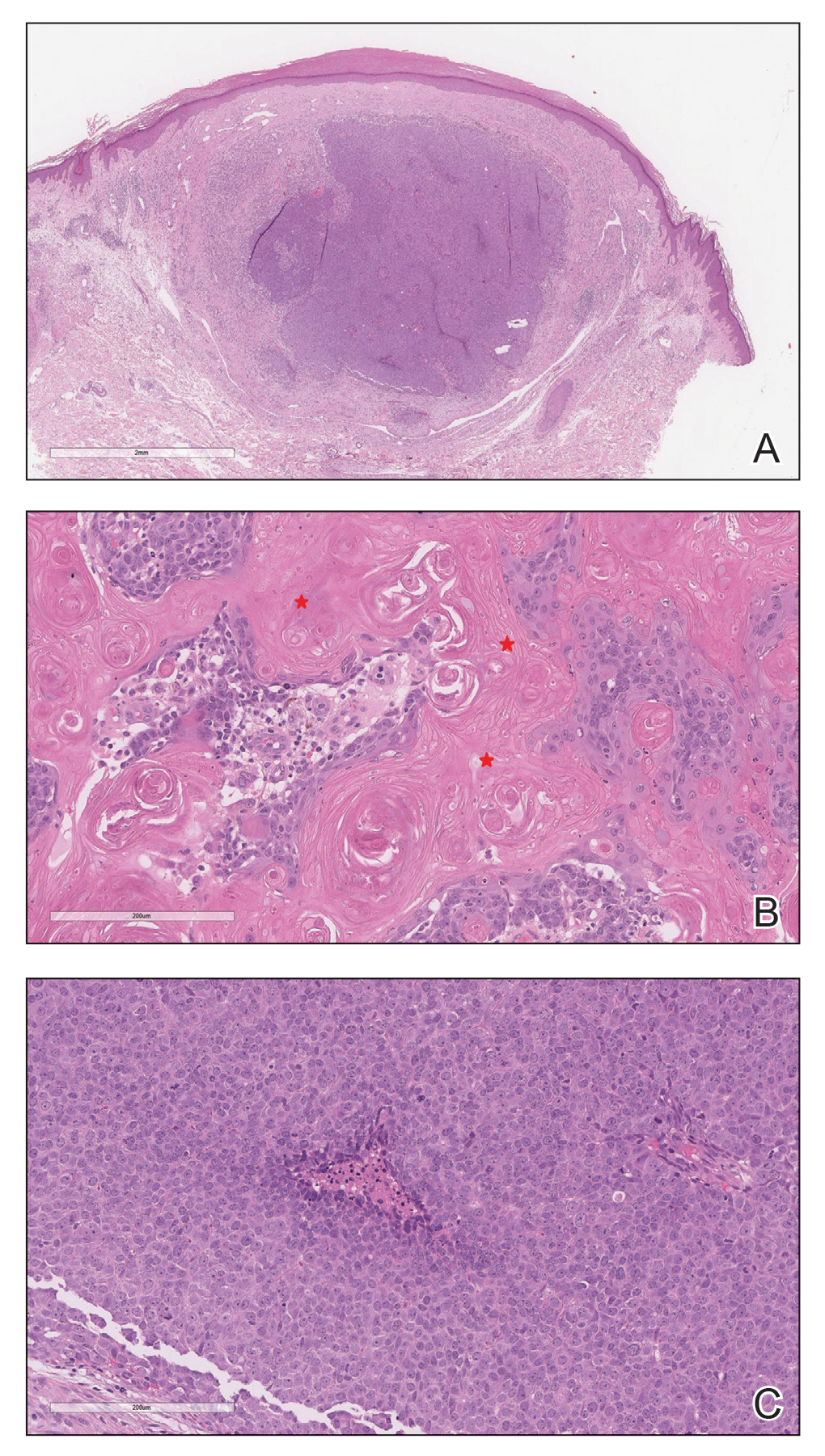

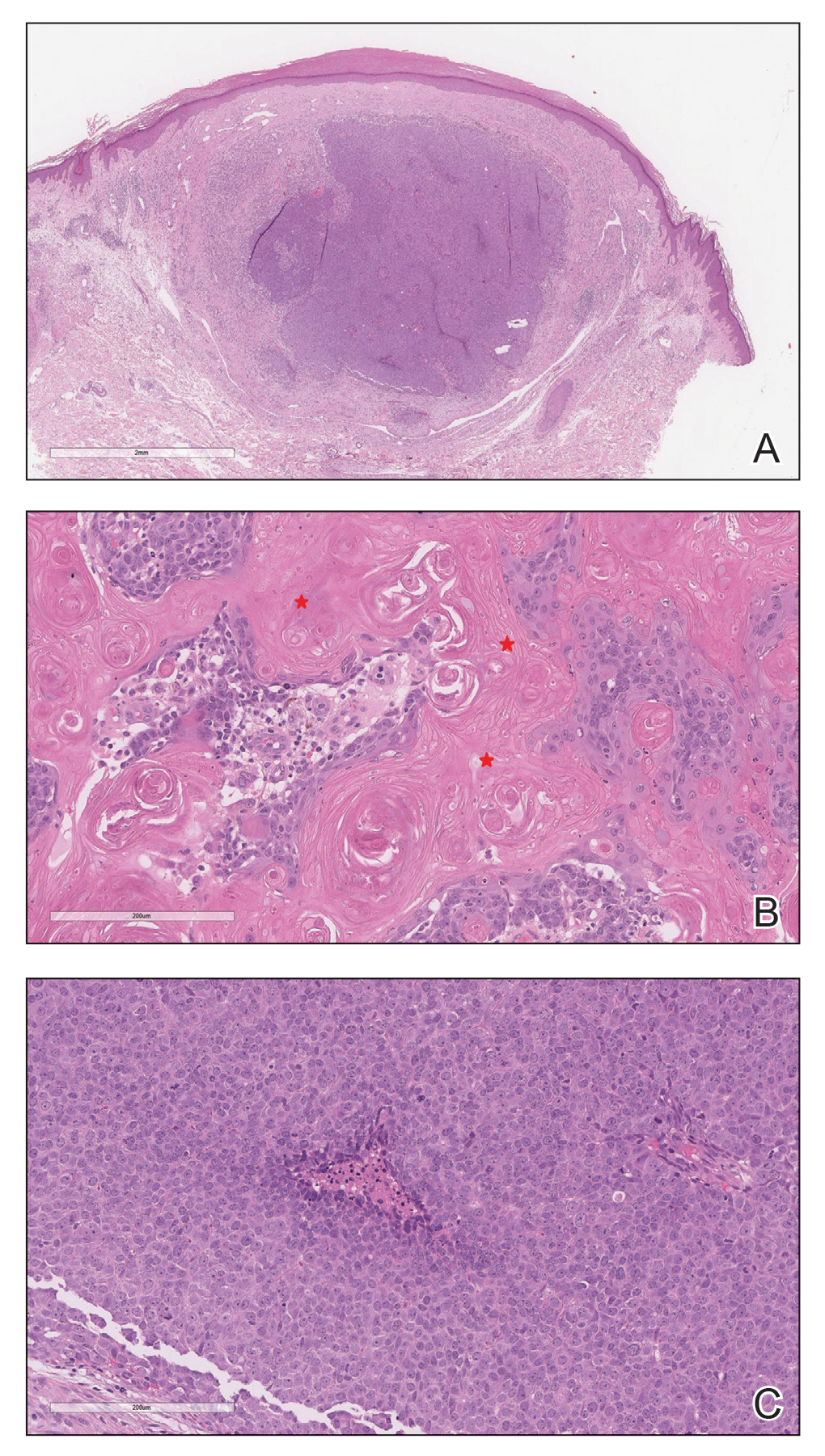

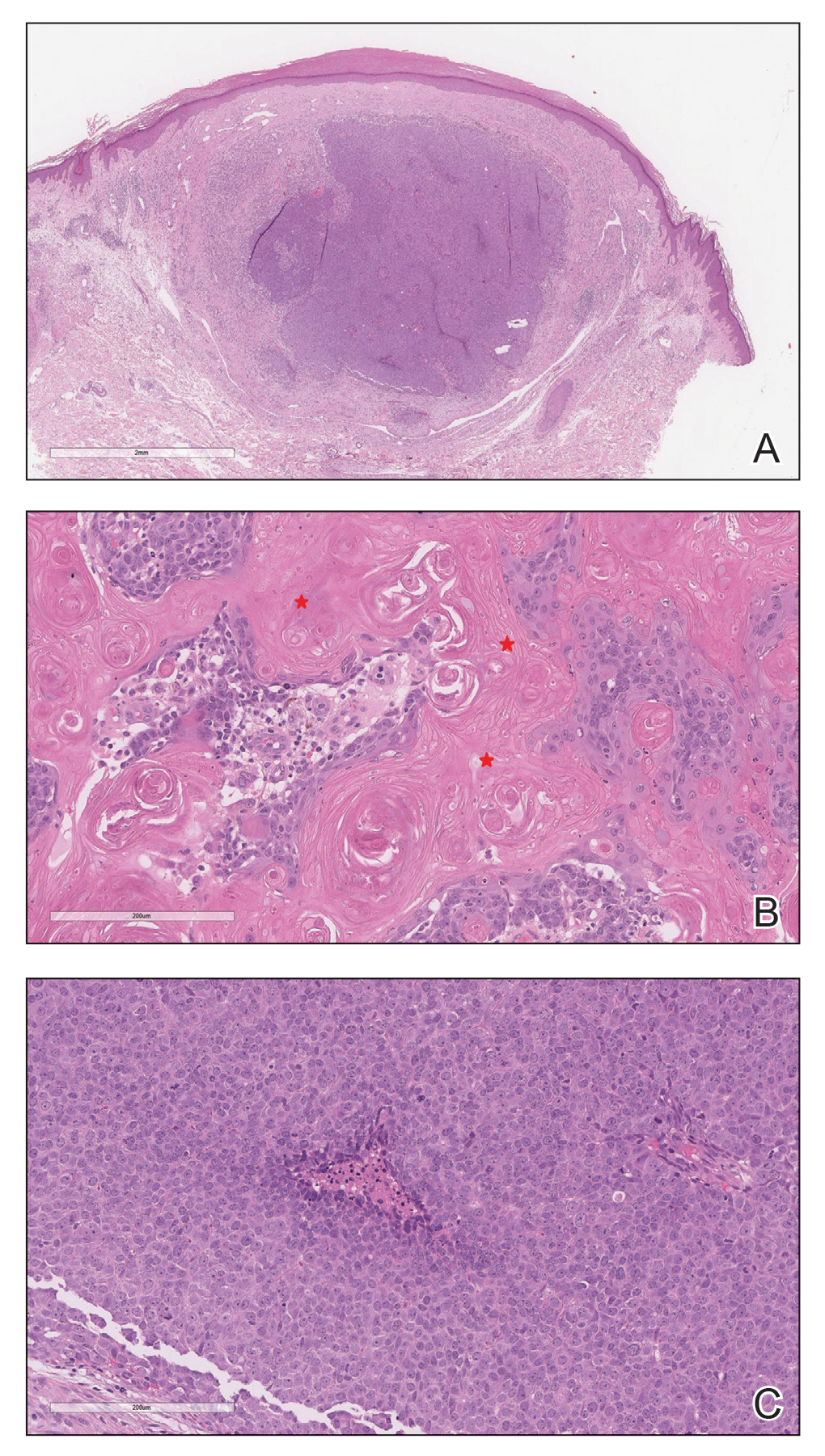

Histopathologic Findings—Gross examination revealed a 0.9×0.7-cm, raised, slightly irregular lesion located 1 mm away from the closest peripheral margin. Histologically, the lesion was a relatively circumscribed, dermal-based basaloid neoplasm with slightly ill-defined edges involving the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). The neoplasm was formed predominantly of sheets of basaloid cells and small nests of ghost cells, in addition to some squamoid and transitional cells (Figure 1B). The basaloid cells exhibited severe nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1C), minimal to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and coarse chromatin pattern. Abundant mitotic activity and apoptotic bodies were present as well as focal area of central necrosis (Figure 1C). Also, melanophages and a multinucleated giant cell reaction was noted. Elastic trichrome special stain highlighted focal infiltration of the neoplastic cells into the adjacent desmoplastic stroma. Melanin stain was negative for melanin pigment within the neoplasm. Given the presence of severely atypical basaloid cells along with ghost cells indicating matrical differentiation, a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma was rendered.

Immunohistochemistry—The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for p63, CDX-2 (Figure 2A), β-catenin (Figure 2B), and CD10 (Figure 2C), and focally and weakly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, BerEP4 (staining the tumor periphery), androgen receptor, and CK18 (a low-molecular-weight keratin). They were negative for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, CK7, CK20, CD34, SOX-10, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Cytokeratin 14 was positive in the squamoid cells but negative in the basaloid cells. SOX-10 and melanoma cocktail immunostains demonstrated few intralesional dendritic melanocytes.

Comment

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm with origin from the germinative matrix of the hair bulb region of hair follicles. Pilomatrix carcinoma was first reported in 1980.1,2 These tumors are characterized by rapid growth and aggressive behavior. Their benign counterpart, pilomatrixoma, is a slow-growing, dermal or subcutaneous tumor that rarely recurs after complete excision.

As with pilomatrixoma, pilomatrix carcinomas are asymptomatic and present as solitary dermal or subcutaneous masses3,4 that most commonly are found in the posterior neck, upper back, and preauricular regions of middle-aged or elderly adults with male predominance.5 They range in size from 0.5 to 20 cm with a mean of 4 cm that is slightly larger than pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas predominantly are firm tumors with or without cystic components, and they exhibit a high probability of recurrence and have risk for distant metastasis.6-15

The differential diagnosis includes epidermal cysts, pilomatrixoma, basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas frequently are mistaken for epidermal cysts on clinical examination. Such a distinction can be easily resolved by histopathologic evaluation. The more challenging differential diagnosis is with pilomatrixoma. Histologically, pilomatrixomas consist of a distinct population of cells including basaloid, squamoid, transitional, and shadow cells in variable proportions. The basaloid cells transition to shadow cells in an organized zonal fashion.16 Compared to pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas often show predominance of the basaloid cells; marked cytologic atypia and pleomorphism; numerous mitotic figures; deep infiltrative pattern into subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skeletal muscle; stromal desmoplasia; necrosis; and neurovascular invasion (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, the shadow cells tend to form a small nested pattern in pilomatrix carcinoma instead of the flat sheetlike pattern usually observed in pilomatrixoma.16 Basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation can pose a diagnostic challenge in the differential diagnosis; basal cell carcinoma usually exhibits a peripheral palisade of the basaloid cells accompanied by retraction spaces separating the tumor from the stroma. Trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma with matrical differentiation can be distinguished by its exuberant stroma, prominent primitive hair follicles, and papillary mesenchymal bodies. Trichilemmal carcinomas are recognized by their connection to the overlying epidermis, peripheral palisading, and presence of clear cells, while pilomatrix carcinoma lacks connection to the surface epithelium.

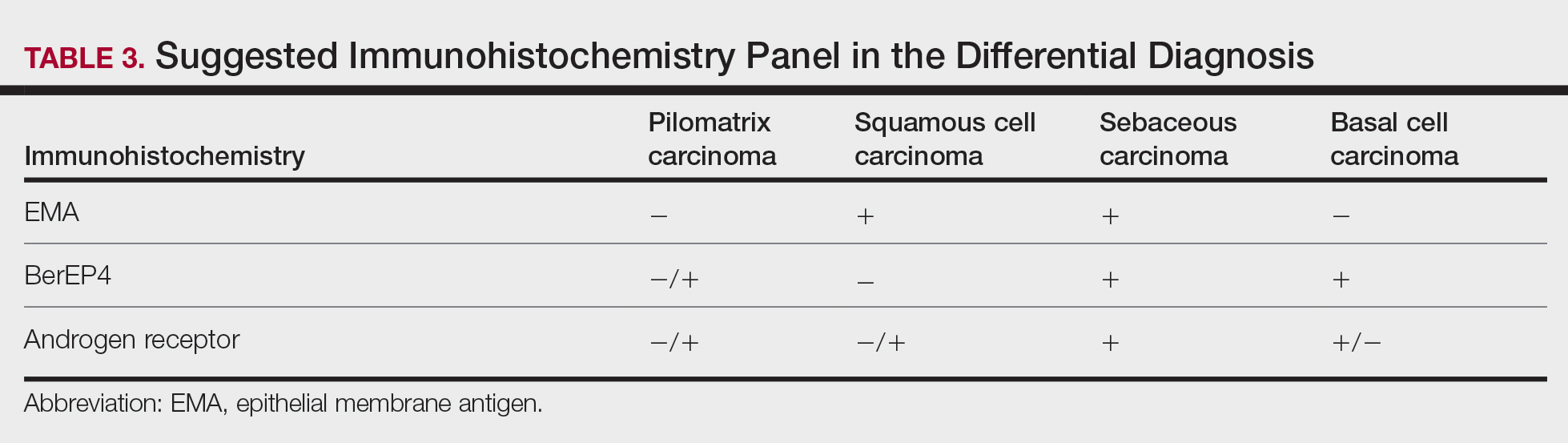

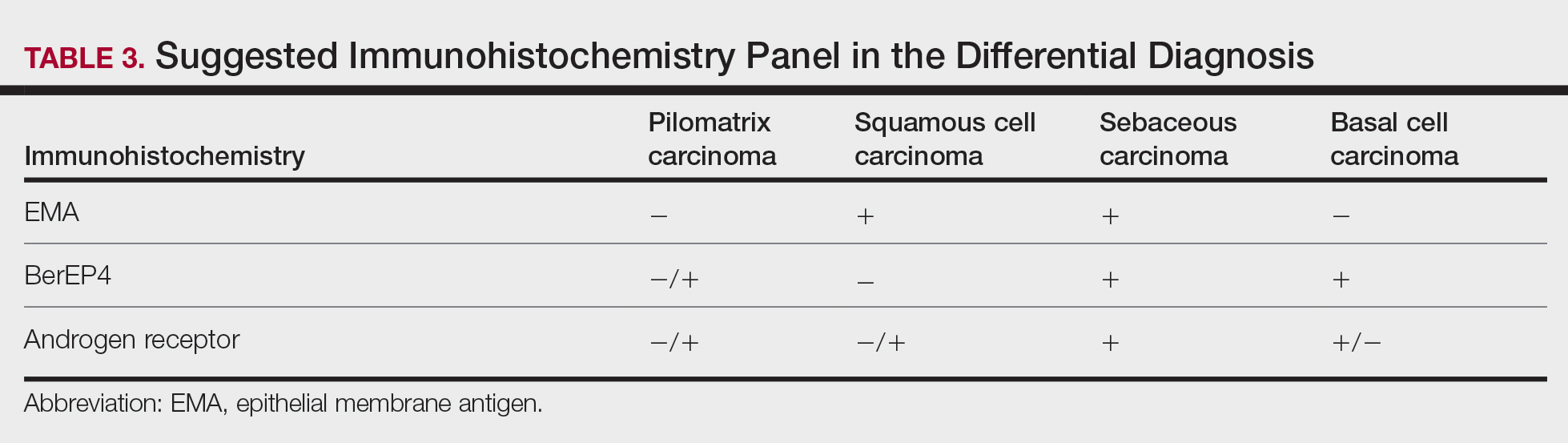

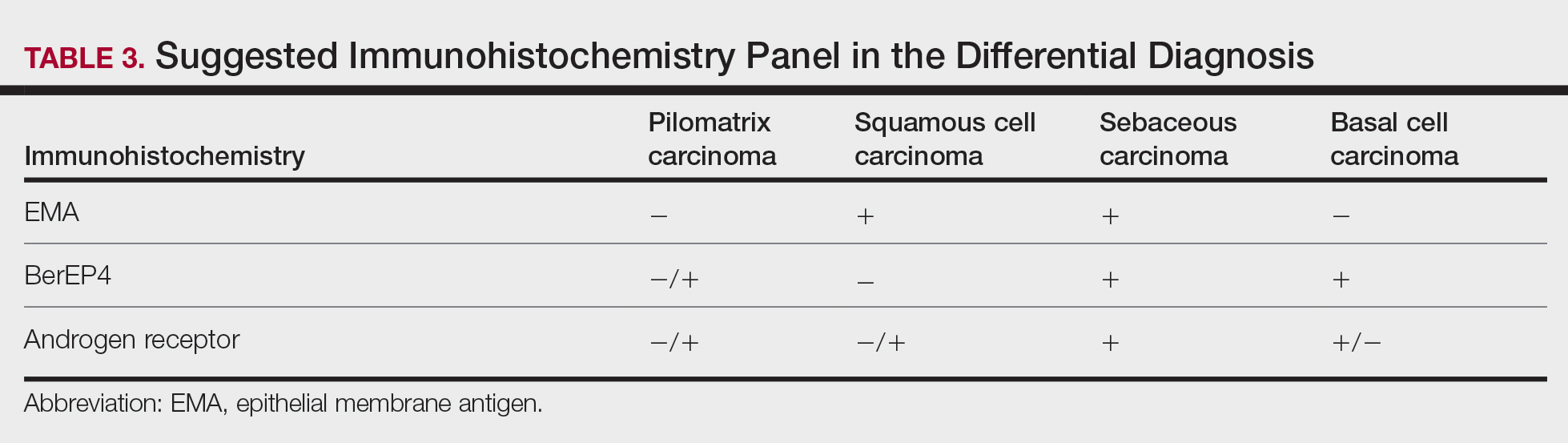

Immunohistochemical stains have little to no role in the differential diagnosis, and morphology is the mainstay in making the diagnosis. Rarely, pilomatrix carcinoma can be confused with poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Although careful scrutiny of the histologic features may help identify mature sebocytes in sebaceous carcinoma, evidence of keratinization in squamous cell carcinoma and ghost cells in pilomatrix carcinoma, using a panel of immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in reaching the final diagnosis (Table 3).

The development of hair matrix tumors have been known to harbor mutations in exon 3 of the catenin beta-1 gene, CTNNB1, that encodes for β-catenin, a downstream effector in the Wnt signaling pathway responsible for differentiation, proliferation, and adhesion of epithelial stem cells.17-21 In a study conducted by Kazakov et al,22 DNA was extracted from 86 lesions: 4 were pilomatrixomas and 1 was a pilomatrix carcinoma. A polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 8 pathogenic variants of the β-catenin gene. D32Y (CTNNB1):c.94G>T (p.Asp32Tyr) and G34R (CTNNB1):c.100G>C (p.Gly34Arg) were the mutations present in pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma, respectively.22 In addition, there are several proteins that are part of the Wnt pathway in addition to β-catenin—LEF-1 and CDX-2.

Tumminello and Hosler23 found that pilomatrixomas and pilomatrix carcinomas were positive for CDX-2, β-catenin, and LEF-1 by immunohistochemistry. These downstream molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway could have the potential to be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers.2,13,15,23

Although the pathogenesis is unclear, there are 2 possible mechanisms by which pilomatrix carcinomas develop. They can either arise as de novo tumors, or it is possible that initial mutations in β-catenin result in the formation of pilomatrixomas at an early age that may undergo malignant transformation in elderly patients over time with additional mutations.2

Our case was strongly and diffusely positive for β-catenin in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern and CDX-2 in a nuclear pattern, supporting the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in such tumors. Furthermore, our case demonstrated the presence of few intralesional normal dendritic melanocytes, a rare finding1,24,25 but not unexpected, as melanocytes normally are present within the hair follicle matrix.

Pilomatrix carcinomas are aggressive tumors with a high risk for local recurrence and tendency for metastasis. In a study of 13 cases of pilomatrix carcinomas, Herrmann et al13 found that metastasis was significantly associated with local tumor recurrence (P<.0413). They concluded that the combination of overall high local recurrence and metastatic rates of pilomatrix carcinoma as well as documented tumor-related deaths would warrant continued patient follow-up, especially for recurrent tumors.13 Rapid growth of a tumor, either de novo or following several months of stable size, should alert physicians to perform a diagnostic biopsy.

Management options of pilomatrix carcinoma include surgery or radiation with close follow-up. The most widely reported treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma is wide local excision with histologically confirmed clear margins. Mohs micrographic surgery is an excellent treatment option.2,13-15 Adjuvant radiation therapy may be necessary following excision. Currently there is no consensus on surgical management, and standard excisional margins have not been defined.26 Jones et al2 concluded that complete excision with wide margins likely is curative, with decreased rates of recurrence, and better awareness of this carcinoma would lead to appropriate treatment while avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests.2

Conclusion

We report an exceptionally unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with a discussion on the pathogenesis and molecular pathology of hair matrix tumors. A large cohort of patients with longer follow-up periods and better molecular characterization is essential in drawing accurate information about their prognosis, identifying molecular markers that can be used as therapeutic targets, and determining ideal management strategy.

- Jani P, Chetty R, Ghazarian DM. An unusual composite pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes: differential diagnosis, immunohistochemical evaluation, and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:174-177.

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38.

- Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606.

- Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Tumors of epidermal appendages. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Lippincott Raven; 1997:757-759.

- Aherne NJ, Fitzpatrick DA, Gibbons D, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma presenting as an extra axial mass: clinicopathological features. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:47.

- Papadakis M, de Bree E, Floros N, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: more malignant biological behavior than was considered in the past. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:415-418.

- LeBoit PE, Parslow TG, Choy SH. Hair matrix differentiation: occurrence in lesions other than pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:399-405.

- Campoy F, Stiefel P, Stiefel E, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: role played by MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:196-198.

- Tateyama H, Eimoto T, Tada T, et al. Malignant pilomatricoma: an immunohistochemical study with antihair keratin antibody. Cancer. 1992;69:127-132.

- O’Donovan DG, Freemont AJ, Adams JE, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1993;23:385-386.

- Cross P, Richmond I, Wells S, et al. Malignant pilomatrixoma with bone metastasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:499-500.

- Niedermeyer HP, Peris K, Höfler H. Pilomatrix carcinoma with multiple visceral metastases: report of a case. Cancer. 1996;77:1311-1314.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

- Xing L, Marzolf SA, Vandergriff T, et al. Facial pilomatrix carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:253-255.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Sarcomatoid pilomatrix carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:508-514.

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498.

- Chan E, Gat U, McNiff JM, et al. A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nat Genet. 1999;21:410-413.

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. β-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533-545.

- Kikuchi A. Tumor formation by genetic mutations in the components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:225-229.

- Durand M, Moles J. Beta-catenin mutations in a common skin cancer: pilomatricoma. Bull Cancer. 1999;86:725-726.

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding beta-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157.

- Kazakov DV, Sima R, Vanecek T, et al. Mutations in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene (β-catenin gene) in cutaneous adnexal tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:248-255.

- Tumminello K, Hosler GA. CDX2 and LEF-1 expression in pilomatrical tumors and their utility in the diagnosis of pilomatrical carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:318-324.

- Rodic´ N, Taube JM, Manson P, et al Locally invasive dermal squamomelanocytic tumor with matrical differentiation: a peculiar case with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E72-E76.

- Perez C, Debbaneh M, Cassarino D. Preference for the term pilomatrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia: letter to the editor. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:655-657.

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare adnexal tumor with origin from the germinative matrical cells of the hair follicle. Clinically, it presents as a solitary lesion commonly found in the head and neck region as well as the upper back. The tumors cannot be distinguished by their clinical appearance only and frequently are mistaken for cysts. Histopathologic examination provides the definitive diagnosis in most cases. These carcinomas are aggressive neoplasms with a high probability of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Assessment of the Wnt signaling pathway components such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2) potentially can be used for diagnostic purposes and targeted therapy.

We report a rare and unique case of early pilomatrix carcinoma with intralesional melanocytes. We review the molecular pathology and pathogenesis of these carcinomas as well as the significance of early diagnosis.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man with a history of extensive sun exposure presented with a 1-cm, raised, rapidly growing, slightly irregular, purple lesion on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration with tendency to bleed. He did not have a history of skin cancers and was otherwise healthy. Excision was recommended due to the progressive and rapid growth of the lesion.

Histopathologic Findings—Gross examination revealed a 0.9×0.7-cm, raised, slightly irregular lesion located 1 mm away from the closest peripheral margin. Histologically, the lesion was a relatively circumscribed, dermal-based basaloid neoplasm with slightly ill-defined edges involving the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). The neoplasm was formed predominantly of sheets of basaloid cells and small nests of ghost cells, in addition to some squamoid and transitional cells (Figure 1B). The basaloid cells exhibited severe nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1C), minimal to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and coarse chromatin pattern. Abundant mitotic activity and apoptotic bodies were present as well as focal area of central necrosis (Figure 1C). Also, melanophages and a multinucleated giant cell reaction was noted. Elastic trichrome special stain highlighted focal infiltration of the neoplastic cells into the adjacent desmoplastic stroma. Melanin stain was negative for melanin pigment within the neoplasm. Given the presence of severely atypical basaloid cells along with ghost cells indicating matrical differentiation, a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma was rendered.

Immunohistochemistry—The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for p63, CDX-2 (Figure 2A), β-catenin (Figure 2B), and CD10 (Figure 2C), and focally and weakly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, BerEP4 (staining the tumor periphery), androgen receptor, and CK18 (a low-molecular-weight keratin). They were negative for monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, CK7, CK20, CD34, SOX-10, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Cytokeratin 14 was positive in the squamoid cells but negative in the basaloid cells. SOX-10 and melanoma cocktail immunostains demonstrated few intralesional dendritic melanocytes.

Comment

Pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm with origin from the germinative matrix of the hair bulb region of hair follicles. Pilomatrix carcinoma was first reported in 1980.1,2 These tumors are characterized by rapid growth and aggressive behavior. Their benign counterpart, pilomatrixoma, is a slow-growing, dermal or subcutaneous tumor that rarely recurs after complete excision.

As with pilomatrixoma, pilomatrix carcinomas are asymptomatic and present as solitary dermal or subcutaneous masses3,4 that most commonly are found in the posterior neck, upper back, and preauricular regions of middle-aged or elderly adults with male predominance.5 They range in size from 0.5 to 20 cm with a mean of 4 cm that is slightly larger than pilomatrixoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas predominantly are firm tumors with or without cystic components, and they exhibit a high probability of recurrence and have risk for distant metastasis.6-15

The differential diagnosis includes epidermal cysts, pilomatrixoma, basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma. Pilomatrix carcinomas frequently are mistaken for epidermal cysts on clinical examination. Such a distinction can be easily resolved by histopathologic evaluation. The more challenging differential diagnosis is with pilomatrixoma. Histologically, pilomatrixomas consist of a distinct population of cells including basaloid, squamoid, transitional, and shadow cells in variable proportions. The basaloid cells transition to shadow cells in an organized zonal fashion.16 Compared to pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas often show predominance of the basaloid cells; marked cytologic atypia and pleomorphism; numerous mitotic figures; deep infiltrative pattern into subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skeletal muscle; stromal desmoplasia; necrosis; and neurovascular invasion (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, the shadow cells tend to form a small nested pattern in pilomatrix carcinoma instead of the flat sheetlike pattern usually observed in pilomatrixoma.16 Basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation can pose a diagnostic challenge in the differential diagnosis; basal cell carcinoma usually exhibits a peripheral palisade of the basaloid cells accompanied by retraction spaces separating the tumor from the stroma. Trichoblastoma/trichoblastic carcinoma with matrical differentiation can be distinguished by its exuberant stroma, prominent primitive hair follicles, and papillary mesenchymal bodies. Trichilemmal carcinomas are recognized by their connection to the overlying epidermis, peripheral palisading, and presence of clear cells, while pilomatrix carcinoma lacks connection to the surface epithelium.

Immunohistochemical stains have little to no role in the differential diagnosis, and morphology is the mainstay in making the diagnosis. Rarely, pilomatrix carcinoma can be confused with poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Although careful scrutiny of the histologic features may help identify mature sebocytes in sebaceous carcinoma, evidence of keratinization in squamous cell carcinoma and ghost cells in pilomatrix carcinoma, using a panel of immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in reaching the final diagnosis (Table 3).

The development of hair matrix tumors have been known to harbor mutations in exon 3 of the catenin beta-1 gene, CTNNB1, that encodes for β-catenin, a downstream effector in the Wnt signaling pathway responsible for differentiation, proliferation, and adhesion of epithelial stem cells.17-21 In a study conducted by Kazakov et al,22 DNA was extracted from 86 lesions: 4 were pilomatrixomas and 1 was a pilomatrix carcinoma. A polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 8 pathogenic variants of the β-catenin gene. D32Y (CTNNB1):c.94G>T (p.Asp32Tyr) and G34R (CTNNB1):c.100G>C (p.Gly34Arg) were the mutations present in pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma, respectively.22 In addition, there are several proteins that are part of the Wnt pathway in addition to β-catenin—LEF-1 and CDX-2.

Tumminello and Hosler23 found that pilomatrixomas and pilomatrix carcinomas were positive for CDX-2, β-catenin, and LEF-1 by immunohistochemistry. These downstream molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway could have the potential to be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers.2,13,15,23

Although the pathogenesis is unclear, there are 2 possible mechanisms by which pilomatrix carcinomas develop. They can either arise as de novo tumors, or it is possible that initial mutations in β-catenin result in the formation of pilomatrixomas at an early age that may undergo malignant transformation in elderly patients over time with additional mutations.2

Our case was strongly and diffusely positive for β-catenin in a nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern and CDX-2 in a nuclear pattern, supporting the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in such tumors. Furthermore, our case demonstrated the presence of few intralesional normal dendritic melanocytes, a rare finding1,24,25 but not unexpected, as melanocytes normally are present within the hair follicle matrix.