User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

High rates of early complications seen in youth with diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – There is a high burden of early complications among young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from an ongoing study demonstrated.

“We are witnessing a recent increase in type 2 diabetes in the pediatric U.S. population, paralleling a somewhat more established rise in type 1 diabetes among youth worldwide,” Dana Dabelea, MD, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “In the face of this increasing disease burden, we are left with limited information on the consequences of having diabetes on these youth, specifically the burden of diabetes-related chronic complications. No study exists in the U.S. that is able to compare this burden in youth with type 2 versus those with type 1 diabetes. Prior studies elsewhere worldwide have used mostly medical records or administrative data, have small sample sizes, and include youth with variable disease duration.”

The aim of the current study was to assess and compare the prevalence of several complications in youth with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes of similar age and disease (short) duration, and to explore the potential risk factors for observed differences by diabetes type. Dr. Dabelea of the department of epidemiology at the University of Colorado School of Public Health in Denver, and her colleagues from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, developed a cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed when younger than age 20, assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008. The most recent visit was between 2011 and 2015 when participants were at least 10 years of age.

Outcomes, measured once at the cohort visit between 2010 and 2015, included diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, arterial stiffness, and hypertension.

Dr. Dabelea reported that 32% of youth with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication. For all complications, except cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, the prevalence was significantly higher in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those who had type 1 disease, with a similar pattern by race, especially for minority youth. Estimates were also usually higher within type among minority vs. non-white Hispanic youth, especially for type 2 diabetes. The findings “indicate a need for heightened clinical suspicion and detection of early complications, together with aggressive risk factor control, especially in type 2 diabetes and minority youth,” she concluded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: There is a high prevalence of early complications in youth with either type of diabetes.

Major finding: About 32% of youths with type 1 diabetes and 72% of those with type 2 diabetes had at least one early complication.

Data source: A cohort of 1,746 individuals with type 1 and 272 with type 2 diabetes who were diagnosed before 20 years of age assembled from the population-based SEARCH Registry in five U.S. sites, and who were registered upon diagnosis between 2002 and 2008.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Dabelea reported having no financial disclosures.

FDA panel narrowly endorses empagliflozin’s cardiovascular mortality benefit

ROCKVILLE, MD. – In a 12-11 vote, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel just barely came down in favor of the agency adding a new labeling entry to the already-approved diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) that would say the drug reduces cardiovascular mortality.

While several members of the panel wished the FDA’s staff good luck in weighing both the evidence and the advisory committee’s closely split endorsement when deciding whether to grant this unprecedented labeling to a diabetes drug, the fact that a majority of panelists favored this course marked a watershed moment in the development of new agents for treating hyperglycemia.

“It’s the first time we have evidence that a diabetes drug can reduce cardiovascular risk. That’s never been seen before, and it’s huge,” said Marvin A. Konstam, MD, a temporary member of the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee (EMDAC) and chief physician executive of the cardiovascular center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “The question is whether or not this effect is real, and the vote was 50-50, but I think there is a good chance it’s real, and, if so, it’s a game changer,” Dr. Konstam said in an interview. He voted in favor of the new labeling, and, like many of his colleagues on the panel, he admitted to agonizing over the decision during the postvote comment period.

What he and the other committee members struggled with was a remarkably strong effect by empagliflozin on reducing cardiovascular mortality by a relative 38%, compared with placebo, in more than 7,000 patients with type 2 diabetes selected for their high cardiovascular disease risk. The major sticking point was that the study enrolled patients into a randomized, placebo-controlled trial that was primarily designed to test the drug’s cardiovascular safety and not its efficacy, and where cardiovascular death was not even a prespecified secondary endpoint.

“It’s very hard to go from safety to superiority in one study,” said Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, who voted against the added indication. Like many panel members who voted no, Dr. Wilson said that any claim to preventing cardiovascular mortality with empagliflozin should meet the standard FDA requirement to have consistent results from at least two studies. “This is the first drug in its class [the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors], and we should have a high bar for the quality of the evidence,” said Dr. Wilson, professor of medicine and public health at Emory University in Atlanta.

“There is substantial evidence [to support the mortality claim], but not yet to the extent to put it on the label,” said another voter on the no side, Judith Fradkin, MD, also a temporary committee member and director of the division of diabetes, endocrinology and metabolic diseases at the National Institutes of Health. The data collected so far in favor of the mortality claim “are very compelling, but what I couldn’t get past is my long-standing belief that a positive result to a study’s secondary outcome is hypothesis generating. We need a second study to put this on the label,” Dr. Fradkin said.

That dramatic and highly meaningful clinical effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular mortality jumped out at the investigators who ran the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial as well as to many others from the moment the results had their unveiling less than a year ago, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Stockholm, and in a concurrently published article (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The primary efficacy endpoint placed into the EMPA-REG OUTCOME safety trial as the study developed following the 2008 FDA mandate for cardiovascular safety trials for all new hypoglycemic drugs was a three-part, combined-outcome endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. Although this primary, combined endpoint had a statistically significant but much more modest benefit with a 14% relative risk reduction, compared with placebo, “the benefit was all driven by the reduction in cardiovascular death that had an astonishing P value of less than .0001 with no suggestion of benefit or risk for MI or stroke,” said Stuart Pocock, PhD, professor of medical statistics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who appeared before the committee as a consultant brought in by the applicant, Boehringer Ingelheim.

The total 309 cardiovascular deaths seen during the study that led to this finding provided more data than most cardiovascular trials, and while in some respects, the cardiovascular benefit seemed “too good to be true,” it also turned out that “the data were so strong that they overwhelm skepticism,” Dr. Pocock told the panel while presenting some advanced statistical test results to prove this assertion. The trial results showed “overwhelming evidence of benefit, beyond a reasonable doubt,” and while cardiovascular death was just one part of the efficacy endpoint, “mortality merits special attention,” he said. The statistical analyses also showed an equally robust 32% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality, and both the cardiovascular and all-cause death benefits seen in EMPA-REG OUTCOME were consistent across both dosages of empagliflozin tested in the study (10 mg and 25 mg daily) and across the sensitivity analyses applied by the investigators.

“These are convincing data, but I’m not comfortable enough that these robust data would be reproduced in a second trial,” said panel chair Robert J. Smith, MD, who voted against the indication.

An additional limitation acting against the proposed new labeling, according to several panel members, is that the mechanism by which empagliflozin might exert protection against cardiovascular death remains unknown, with no suggestion in the trial results that it acts by protecting patients against ischemic disease.

Current opinion also splits among clinicians on how empagliflozin, which has had FDA approval since 2014 as an option for treating type 2 diabetes, should be used in routine practice to treat diabetes patients with high cardiovascular risk who match those enrolled in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Dr. Smith urged a cautious approach.

“I think it’s important [for prescribers] to wait to hear from the FDA. If the cardiovascular mortality benefit was proven, then it would be an important option given the magnitude of cardiovascular disease and death as a consequence of type 2 diabetes. But people should be cautious in drawing their own interpretations of the data,” Dr. Smith, professor of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., said in an interview. For the time being, metformin remains the top oral drug for most of these patients because of its proven effectiveness and low cost, he added.

But others have already been active in prescribing empagliflozin to at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes based on last year’s EMPA-REG OUTCOME report.

“I am using it in addition to metformin and aggressive lifestyle changes in patients with established cardiovascular disease and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes,” commented Alison L. Bailey, MD, a cardiologist at the Erlanger Health System and University of Tennessee in Chattanooga. “A patient’s health insurance status must be taken into account as empagliflozin can be a significant financial burden, but if all other things are equal and cost is not prohibitive, I am definitely using this in my patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. I think there are enough data to warrant its use first line in patients who can get the drug without a financial burden,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Konstam cautioned that “just because empagliflozin may have a cardiovascular effect does not make it a cardiovascular drug. As a cardiologist I am not comfortable prescribing this drug. When it comes to diabetes management ,you need to take many things into consideration, most notably blood sugar and hemoglobin A1c,” which are usually best managed by a diabetologist or experienced primary care physician, he said.

Dr. Konstam, Dr. Wilson, Dr. Fradkin, and Dr. Smith had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pocock is a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Bailey has received research grants from CSL Behring.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

ROCKVILLE, MD. – In a 12-11 vote, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel just barely came down in favor of the agency adding a new labeling entry to the already-approved diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) that would say the drug reduces cardiovascular mortality.

While several members of the panel wished the FDA’s staff good luck in weighing both the evidence and the advisory committee’s closely split endorsement when deciding whether to grant this unprecedented labeling to a diabetes drug, the fact that a majority of panelists favored this course marked a watershed moment in the development of new agents for treating hyperglycemia.

“It’s the first time we have evidence that a diabetes drug can reduce cardiovascular risk. That’s never been seen before, and it’s huge,” said Marvin A. Konstam, MD, a temporary member of the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee (EMDAC) and chief physician executive of the cardiovascular center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “The question is whether or not this effect is real, and the vote was 50-50, but I think there is a good chance it’s real, and, if so, it’s a game changer,” Dr. Konstam said in an interview. He voted in favor of the new labeling, and, like many of his colleagues on the panel, he admitted to agonizing over the decision during the postvote comment period.

What he and the other committee members struggled with was a remarkably strong effect by empagliflozin on reducing cardiovascular mortality by a relative 38%, compared with placebo, in more than 7,000 patients with type 2 diabetes selected for their high cardiovascular disease risk. The major sticking point was that the study enrolled patients into a randomized, placebo-controlled trial that was primarily designed to test the drug’s cardiovascular safety and not its efficacy, and where cardiovascular death was not even a prespecified secondary endpoint.

“It’s very hard to go from safety to superiority in one study,” said Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, who voted against the added indication. Like many panel members who voted no, Dr. Wilson said that any claim to preventing cardiovascular mortality with empagliflozin should meet the standard FDA requirement to have consistent results from at least two studies. “This is the first drug in its class [the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors], and we should have a high bar for the quality of the evidence,” said Dr. Wilson, professor of medicine and public health at Emory University in Atlanta.

“There is substantial evidence [to support the mortality claim], but not yet to the extent to put it on the label,” said another voter on the no side, Judith Fradkin, MD, also a temporary committee member and director of the division of diabetes, endocrinology and metabolic diseases at the National Institutes of Health. The data collected so far in favor of the mortality claim “are very compelling, but what I couldn’t get past is my long-standing belief that a positive result to a study’s secondary outcome is hypothesis generating. We need a second study to put this on the label,” Dr. Fradkin said.

That dramatic and highly meaningful clinical effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular mortality jumped out at the investigators who ran the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial as well as to many others from the moment the results had their unveiling less than a year ago, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Stockholm, and in a concurrently published article (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The primary efficacy endpoint placed into the EMPA-REG OUTCOME safety trial as the study developed following the 2008 FDA mandate for cardiovascular safety trials for all new hypoglycemic drugs was a three-part, combined-outcome endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. Although this primary, combined endpoint had a statistically significant but much more modest benefit with a 14% relative risk reduction, compared with placebo, “the benefit was all driven by the reduction in cardiovascular death that had an astonishing P value of less than .0001 with no suggestion of benefit or risk for MI or stroke,” said Stuart Pocock, PhD, professor of medical statistics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who appeared before the committee as a consultant brought in by the applicant, Boehringer Ingelheim.

The total 309 cardiovascular deaths seen during the study that led to this finding provided more data than most cardiovascular trials, and while in some respects, the cardiovascular benefit seemed “too good to be true,” it also turned out that “the data were so strong that they overwhelm skepticism,” Dr. Pocock told the panel while presenting some advanced statistical test results to prove this assertion. The trial results showed “overwhelming evidence of benefit, beyond a reasonable doubt,” and while cardiovascular death was just one part of the efficacy endpoint, “mortality merits special attention,” he said. The statistical analyses also showed an equally robust 32% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality, and both the cardiovascular and all-cause death benefits seen in EMPA-REG OUTCOME were consistent across both dosages of empagliflozin tested in the study (10 mg and 25 mg daily) and across the sensitivity analyses applied by the investigators.

“These are convincing data, but I’m not comfortable enough that these robust data would be reproduced in a second trial,” said panel chair Robert J. Smith, MD, who voted against the indication.

An additional limitation acting against the proposed new labeling, according to several panel members, is that the mechanism by which empagliflozin might exert protection against cardiovascular death remains unknown, with no suggestion in the trial results that it acts by protecting patients against ischemic disease.

Current opinion also splits among clinicians on how empagliflozin, which has had FDA approval since 2014 as an option for treating type 2 diabetes, should be used in routine practice to treat diabetes patients with high cardiovascular risk who match those enrolled in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Dr. Smith urged a cautious approach.

“I think it’s important [for prescribers] to wait to hear from the FDA. If the cardiovascular mortality benefit was proven, then it would be an important option given the magnitude of cardiovascular disease and death as a consequence of type 2 diabetes. But people should be cautious in drawing their own interpretations of the data,” Dr. Smith, professor of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., said in an interview. For the time being, metformin remains the top oral drug for most of these patients because of its proven effectiveness and low cost, he added.

But others have already been active in prescribing empagliflozin to at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes based on last year’s EMPA-REG OUTCOME report.

“I am using it in addition to metformin and aggressive lifestyle changes in patients with established cardiovascular disease and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes,” commented Alison L. Bailey, MD, a cardiologist at the Erlanger Health System and University of Tennessee in Chattanooga. “A patient’s health insurance status must be taken into account as empagliflozin can be a significant financial burden, but if all other things are equal and cost is not prohibitive, I am definitely using this in my patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. I think there are enough data to warrant its use first line in patients who can get the drug without a financial burden,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Konstam cautioned that “just because empagliflozin may have a cardiovascular effect does not make it a cardiovascular drug. As a cardiologist I am not comfortable prescribing this drug. When it comes to diabetes management ,you need to take many things into consideration, most notably blood sugar and hemoglobin A1c,” which are usually best managed by a diabetologist or experienced primary care physician, he said.

Dr. Konstam, Dr. Wilson, Dr. Fradkin, and Dr. Smith had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pocock is a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Bailey has received research grants from CSL Behring.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

ROCKVILLE, MD. – In a 12-11 vote, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel just barely came down in favor of the agency adding a new labeling entry to the already-approved diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) that would say the drug reduces cardiovascular mortality.

While several members of the panel wished the FDA’s staff good luck in weighing both the evidence and the advisory committee’s closely split endorsement when deciding whether to grant this unprecedented labeling to a diabetes drug, the fact that a majority of panelists favored this course marked a watershed moment in the development of new agents for treating hyperglycemia.

“It’s the first time we have evidence that a diabetes drug can reduce cardiovascular risk. That’s never been seen before, and it’s huge,” said Marvin A. Konstam, MD, a temporary member of the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee (EMDAC) and chief physician executive of the cardiovascular center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “The question is whether or not this effect is real, and the vote was 50-50, but I think there is a good chance it’s real, and, if so, it’s a game changer,” Dr. Konstam said in an interview. He voted in favor of the new labeling, and, like many of his colleagues on the panel, he admitted to agonizing over the decision during the postvote comment period.

What he and the other committee members struggled with was a remarkably strong effect by empagliflozin on reducing cardiovascular mortality by a relative 38%, compared with placebo, in more than 7,000 patients with type 2 diabetes selected for their high cardiovascular disease risk. The major sticking point was that the study enrolled patients into a randomized, placebo-controlled trial that was primarily designed to test the drug’s cardiovascular safety and not its efficacy, and where cardiovascular death was not even a prespecified secondary endpoint.

“It’s very hard to go from safety to superiority in one study,” said Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, who voted against the added indication. Like many panel members who voted no, Dr. Wilson said that any claim to preventing cardiovascular mortality with empagliflozin should meet the standard FDA requirement to have consistent results from at least two studies. “This is the first drug in its class [the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors], and we should have a high bar for the quality of the evidence,” said Dr. Wilson, professor of medicine and public health at Emory University in Atlanta.

“There is substantial evidence [to support the mortality claim], but not yet to the extent to put it on the label,” said another voter on the no side, Judith Fradkin, MD, also a temporary committee member and director of the division of diabetes, endocrinology and metabolic diseases at the National Institutes of Health. The data collected so far in favor of the mortality claim “are very compelling, but what I couldn’t get past is my long-standing belief that a positive result to a study’s secondary outcome is hypothesis generating. We need a second study to put this on the label,” Dr. Fradkin said.

That dramatic and highly meaningful clinical effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular mortality jumped out at the investigators who ran the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial as well as to many others from the moment the results had their unveiling less than a year ago, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Stockholm, and in a concurrently published article (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The primary efficacy endpoint placed into the EMPA-REG OUTCOME safety trial as the study developed following the 2008 FDA mandate for cardiovascular safety trials for all new hypoglycemic drugs was a three-part, combined-outcome endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. Although this primary, combined endpoint had a statistically significant but much more modest benefit with a 14% relative risk reduction, compared with placebo, “the benefit was all driven by the reduction in cardiovascular death that had an astonishing P value of less than .0001 with no suggestion of benefit or risk for MI or stroke,” said Stuart Pocock, PhD, professor of medical statistics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who appeared before the committee as a consultant brought in by the applicant, Boehringer Ingelheim.

The total 309 cardiovascular deaths seen during the study that led to this finding provided more data than most cardiovascular trials, and while in some respects, the cardiovascular benefit seemed “too good to be true,” it also turned out that “the data were so strong that they overwhelm skepticism,” Dr. Pocock told the panel while presenting some advanced statistical test results to prove this assertion. The trial results showed “overwhelming evidence of benefit, beyond a reasonable doubt,” and while cardiovascular death was just one part of the efficacy endpoint, “mortality merits special attention,” he said. The statistical analyses also showed an equally robust 32% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality, and both the cardiovascular and all-cause death benefits seen in EMPA-REG OUTCOME were consistent across both dosages of empagliflozin tested in the study (10 mg and 25 mg daily) and across the sensitivity analyses applied by the investigators.

“These are convincing data, but I’m not comfortable enough that these robust data would be reproduced in a second trial,” said panel chair Robert J. Smith, MD, who voted against the indication.

An additional limitation acting against the proposed new labeling, according to several panel members, is that the mechanism by which empagliflozin might exert protection against cardiovascular death remains unknown, with no suggestion in the trial results that it acts by protecting patients against ischemic disease.

Current opinion also splits among clinicians on how empagliflozin, which has had FDA approval since 2014 as an option for treating type 2 diabetes, should be used in routine practice to treat diabetes patients with high cardiovascular risk who match those enrolled in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Dr. Smith urged a cautious approach.

“I think it’s important [for prescribers] to wait to hear from the FDA. If the cardiovascular mortality benefit was proven, then it would be an important option given the magnitude of cardiovascular disease and death as a consequence of type 2 diabetes. But people should be cautious in drawing their own interpretations of the data,” Dr. Smith, professor of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., said in an interview. For the time being, metformin remains the top oral drug for most of these patients because of its proven effectiveness and low cost, he added.

But others have already been active in prescribing empagliflozin to at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes based on last year’s EMPA-REG OUTCOME report.

“I am using it in addition to metformin and aggressive lifestyle changes in patients with established cardiovascular disease and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes,” commented Alison L. Bailey, MD, a cardiologist at the Erlanger Health System and University of Tennessee in Chattanooga. “A patient’s health insurance status must be taken into account as empagliflozin can be a significant financial burden, but if all other things are equal and cost is not prohibitive, I am definitely using this in my patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. I think there are enough data to warrant its use first line in patients who can get the drug without a financial burden,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Konstam cautioned that “just because empagliflozin may have a cardiovascular effect does not make it a cardiovascular drug. As a cardiologist I am not comfortable prescribing this drug. When it comes to diabetes management ,you need to take many things into consideration, most notably blood sugar and hemoglobin A1c,” which are usually best managed by a diabetologist or experienced primary care physician, he said.

Dr. Konstam, Dr. Wilson, Dr. Fradkin, and Dr. Smith had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Pocock is a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Bailey has received research grants from CSL Behring.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

AT AN FDA EMDAC MEETING

Novel vaccine scores better hepatitis B seroprotection in type 2 diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational hepatitis B vaccine known as Heplisav-B provided significantly better seroprotection among adults with type 2 diabetes than did a currently licensed vaccine, based on results from a randomized phase III trial.

A total of 321 patients received three doses of the Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of the investigational vaccine Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 and a placebo injection at week 24. In both groups of patients, two-thirds of subjects had diabetes for 5 or more years, Randall N. Hyer, MD, reported in a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

At 28 weeks, 90% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group and 65% in the Engerix-B group achieved seroprotection, defined as anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater. The difference reached statistical significance. Among study participants aged 60-70 years, 85.8% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 58.5% in the Engerix-B group. Among study participants with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2, 89.5% of subjects in the Heplisav-B group achieved seroprotection, compared with 61.4% in the Engerix-B group, reported Dr. Hyer, who is vice president of medical affairs for Dynavax, the maker of Heplisav-B.

The safety profile, including the incidence of immune-mediated adverse events, was similar in both treatment groups. The most frequently reported local reaction was injection-site pain, while the most common systemic reactions were fatigue, headache, and malaise.

Dynavax submitted a biologics license application to the FDA in March 2016, and a decision on whether to approve Heplisav-B is expected by mid-December. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does recommend that all adults with diabetes aged 19-59 be vaccinated against HBV [hepatitis B virus] as soon as feasible after diagnosis. For folks 60 and above, it’s at the discretion of the physician. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get HBV,” Dr. Hyer said in an interview.

Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Compared with Engerix-B, Heplisav-B protected more subjects with diabetes against hepatitis B.

Major finding: At 28 weeks, 90% of the Heplisav-B group and 65% of the Engerix-B group had anti–hepatitis B titers of 10 mIU/mL or greater.

Data source: A phase III randomized trial in which 321 patients received three doses of Engerix-B at weeks 0, 4, and 24, while 640 patients received two doses of Heplisav-B at weeks 0 and 4 (plus placebo at week 24).

Disclosures: Dynavax funded the study. Dr. Hyer is an employee of the company.

Who are the ‘no-shows’ to diabetes education classes?

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes who failed to show up for diabetes education classes were slightly younger and less likely to be insured, compared with those who attended the classes. Forty-one percent of those who failed to show were covered by private insurance, and 63% were women.

Those are key findings from an analysis by researchers to investigate the patterns of population characteristics related nonadherence to diabetes education classes that patients are referred to.

“What it shows us is that when we’re trying to get people to come to diabetes education classes, we have to be in tune with the sociodemographic characteristics that present different barriers or obstacles,” Ashby Walker, PhD, said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Walker, of the department of health outcomes and policy at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates, including Kathryn Parker, RD, program manager for diabetes education at the UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, conducted a manual chart review to examine the demographics of 257 “no-shows” who were referred to a diabetes education class at the university’s hospital between January 2015 and March 2015. Data of interest included age, gender, diagnosis, reasons for referral, referring department, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. For comparison purposes, the researchers also examined a cohort of 339 patients who showed up for their diabetes education classes between August 2014 and January 2015.

More than two-thirds of the no-shows (69%) had type 2 diabetes, 63% were women, and the mean age was 50 years. More than half (57%) were publicly insured or uninsured, while 41% had private insurance and 3% were self-pay or had missing data for insurance type.

The fact that a higher proportion of the insured no-shows were women surprised the researchers. “If you think about women who are working full time, they often shoulder the tremendous responsibility of household labor, too,” Dr. Walker said. “So for them to take time out of very busy lives to take care of themselves might create a different obstacle than someone who’s very low income or low health literacy who has transportation as a barrier. The findings show us that we have to tailor those interventions appropriately for different audiences.”

Another surprise finding, she said, was the fact that males were underrepresented in both the “no show” cohort (37%) and among those who honored their referrals (32%). “While there are some studies that indicate women fare worse with diabetes than men, the underrepresentation of men warrants further attention,” Dr. Walker said. “It begs the question: Are providers referring men less?”

Shannon Taylor, a fellow researcher at the University of Florida, said that the study’s findings underscore the need for clinicians “to be attuned to the different things about social life that can impact how people self-care, whether it’s gender differences or differences in socioeconomic status.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Endoscopic ablation follows gastric bypass principles

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

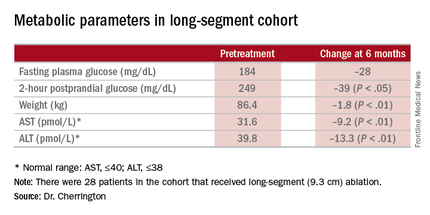

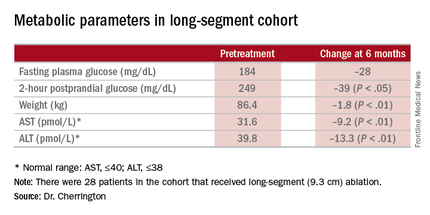

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

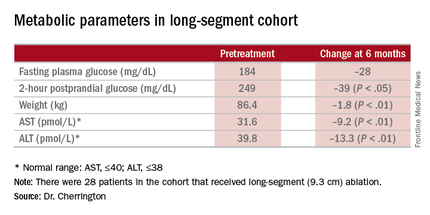

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

AT THE ADA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Duodenal mucosal resurfacing is an investigational procedure to achieve improvement in metabolic parameters in type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: A cohort that has HbA1c as high as 11% before the procedure had average HbA1c of 7.5% afterward.

Data source: Investigational study of 39 patients who had the procedure at a single center in Chile.

Disclosures: Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

Body weight of U.S. veterans increased significantly from 2000 to 2014

NEW ORLEANS – United States veterans born since 1950 have gained weight faster than a comparable cohort of older veterans, results from a large analysis demonstrated. In fact, they’re starting out about 10 kg heavier than previous generations.

“There is a tremendous need for an intervention to prevent or reverse weight gain in this population to prevent the development of diabetes,” lead author Margery J. Tamas said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In an effort to examine age-related trends in body weight and diabetes prevalence in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system, Ms. Tamas and her associates used the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to examine trends in diabetes among 4,680,735 patients born between 1915 and 1984 who had at least one outpatient visit per year within any consecutive 4-year interval between 2000 and 2014. More than one-third (36%) had diabetes, 92% were male, 78% were white, and their mean age was 69 years. The researchers defined the birth cohorts by 5-year intervals.

Ms. Tamas, who conducted the research as part of her master’s thesis at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, reported that diabetes was more prevalent among men, compared with women (38% vs. 24%, respectively). Diabetes prevalence was highest among patients born between 1940 and 1944 (44%) and lowest among those born between 1980 and 1984 (4%).

The assessment of weight also revealed that the median baseline weight was higher in men and women with diabetes (94 kg and 86 kg, respectively), compared with their counterparts who did not have diabetes (84 kg and 73 kg, respectively). The researchers observed that median weight increased significantly between 2000 and 2014 (P less than .001), with the greatest increase among patients without diabetes. The highest rate of weight increase occurred in women without diabetes (an increase of 0.39 kg per year). However, between 2000 and 2014 weight decreased in the oldest patient cohorts and increased in the youngest cohorts. “Weight changed faster at younger ages, and was highest in those with diabetes and in women,” Ms. Tamas said. “This kind of pattern where young people are gaining weight faster than older people has also been seen in the Global Burden of Disease Study.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the data do not correct for survival bias. The study was based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ms. Tamas reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this research.

NEW ORLEANS – United States veterans born since 1950 have gained weight faster than a comparable cohort of older veterans, results from a large analysis demonstrated. In fact, they’re starting out about 10 kg heavier than previous generations.

“There is a tremendous need for an intervention to prevent or reverse weight gain in this population to prevent the development of diabetes,” lead author Margery J. Tamas said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In an effort to examine age-related trends in body weight and diabetes prevalence in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system, Ms. Tamas and her associates used the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to examine trends in diabetes among 4,680,735 patients born between 1915 and 1984 who had at least one outpatient visit per year within any consecutive 4-year interval between 2000 and 2014. More than one-third (36%) had diabetes, 92% were male, 78% were white, and their mean age was 69 years. The researchers defined the birth cohorts by 5-year intervals.

Ms. Tamas, who conducted the research as part of her master’s thesis at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, reported that diabetes was more prevalent among men, compared with women (38% vs. 24%, respectively). Diabetes prevalence was highest among patients born between 1940 and 1944 (44%) and lowest among those born between 1980 and 1984 (4%).

The assessment of weight also revealed that the median baseline weight was higher in men and women with diabetes (94 kg and 86 kg, respectively), compared with their counterparts who did not have diabetes (84 kg and 73 kg, respectively). The researchers observed that median weight increased significantly between 2000 and 2014 (P less than .001), with the greatest increase among patients without diabetes. The highest rate of weight increase occurred in women without diabetes (an increase of 0.39 kg per year). However, between 2000 and 2014 weight decreased in the oldest patient cohorts and increased in the youngest cohorts. “Weight changed faster at younger ages, and was highest in those with diabetes and in women,” Ms. Tamas said. “This kind of pattern where young people are gaining weight faster than older people has also been seen in the Global Burden of Disease Study.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the data do not correct for survival bias. The study was based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ms. Tamas reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this research.

NEW ORLEANS – United States veterans born since 1950 have gained weight faster than a comparable cohort of older veterans, results from a large analysis demonstrated. In fact, they’re starting out about 10 kg heavier than previous generations.

“There is a tremendous need for an intervention to prevent or reverse weight gain in this population to prevent the development of diabetes,” lead author Margery J. Tamas said in an interview at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In an effort to examine age-related trends in body weight and diabetes prevalence in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system, Ms. Tamas and her associates used the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to examine trends in diabetes among 4,680,735 patients born between 1915 and 1984 who had at least one outpatient visit per year within any consecutive 4-year interval between 2000 and 2014. More than one-third (36%) had diabetes, 92% were male, 78% were white, and their mean age was 69 years. The researchers defined the birth cohorts by 5-year intervals.

Ms. Tamas, who conducted the research as part of her master’s thesis at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, reported that diabetes was more prevalent among men, compared with women (38% vs. 24%, respectively). Diabetes prevalence was highest among patients born between 1940 and 1944 (44%) and lowest among those born between 1980 and 1984 (4%).

The assessment of weight also revealed that the median baseline weight was higher in men and women with diabetes (94 kg and 86 kg, respectively), compared with their counterparts who did not have diabetes (84 kg and 73 kg, respectively). The researchers observed that median weight increased significantly between 2000 and 2014 (P less than .001), with the greatest increase among patients without diabetes. The highest rate of weight increase occurred in women without diabetes (an increase of 0.39 kg per year). However, between 2000 and 2014 weight decreased in the oldest patient cohorts and increased in the youngest cohorts. “Weight changed faster at younger ages, and was highest in those with diabetes and in women,” Ms. Tamas said. “This kind of pattern where young people are gaining weight faster than older people has also been seen in the Global Burden of Disease Study.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the data do not correct for survival bias. The study was based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ms. Tamas reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this research.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: The body weight of U.S. veterans increased significantly between 2000 and 2014.

Major finding: The median weight of U.S. veterans increased significantly between 2000 and 2014 (P less than .001), with the greatest increase among patients without diabetes.

Data source: An analysis of data from 4,680,735 VA patients born between 1915 and 1984 who had at least one outpatient visit per year within any consecutive 4-year interval between 2000 and 2014.

Disclosures: The study was based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ms. Tamas reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this research.

Empagliflozin surpasses glimepiride as metformin add-on

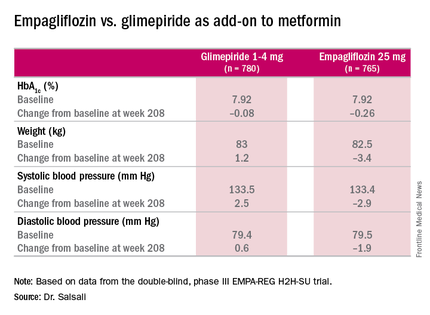

NEW ORLEANS – When used as an add-on therapy to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, empagliflozin has sustained safety and efficacy in reducing in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and other key metabolic measures for up to 4 years, according to results of the EMPA-REG H2H-SU trial presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

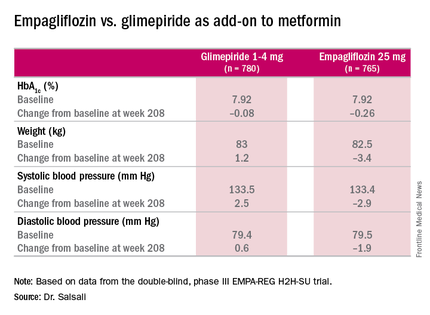

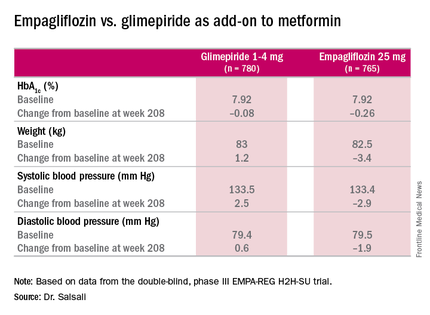

The latest results of the double-blind, phase III trial extended out to 4 years the previously published 2-year results (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:691-700) in comparing empagliflozin, a sodium glucose cotransporter inhibitor, 25 mg daily, and the sulfonylurea glimepiride, 1-4 mg daily, as add-on therapy to metformin. “As previously reported, after 2 years there was a modest difference in HbA1c between empagliflozin and glimepiride,” said Dr. Afshin Salsali, reporting for the trial group. “This difference continued for the remainder of the study, although there was a slight rebound in each group,” according to Dr. Salsali, executive director of global clinical development at Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, Conn.

The 4-year results involved more than 73% of the 1,545 patients who participated in the 2-year study, Dr. Salsali said. The majority of patients were white, with average HbA1c levels of 7.92% and weight of 82.5 kg at the outset of the 2-year study. After 4 years, average HbA1c levels declined 0.08% in those on glimepiride vs. 0.26% for empagliflozin, Dr. Salsali said, achieving the primary study endpoint of noninferiority to glimepiride. However, he noted that rates of hypoglycemia varied dramatically between the two therapies. “This was achieved at the rate of much lower hypoglycemia on empagliflozin, compared with glimepiride, 3% vs. 25% (P less than .001),” he said.