User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Artificial pancreas can improve inpatient glycemic control in type 2 diabetes

NEW ORLEANS – Having people with type 2 diabetes mellitus use an artificial pancreas during hospitalization has the potential to improve control of their glycemia when compared with conventional insulin therapy, based on the results of a small study of inpatients in the United Kingdom.

“This is the first study to show that automated subcutaneous closed-loop insulin delivery without meal-time insulin is feasible and safe in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” Dr. Hood Thabit of the University of Cambridge (England) reported at the ADA annual scientific sessions. “Closed-loop [delivery] increased time in target, with reduced glucose variability and reduced time spent hyperglycemic without actually increasing time spent hypoglycemic,” he said.

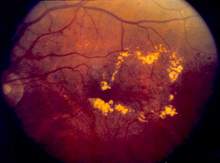

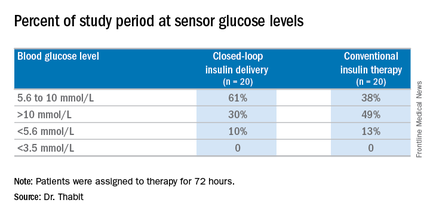

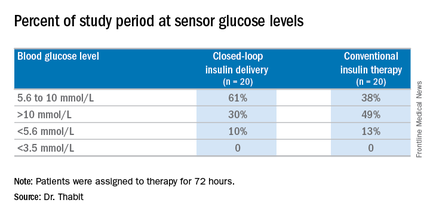

The study involved 40 general ward inpatients evenly assigned to the closed-loop system and conventional insulin therapy for 72 hours.

Dr. Thabit said hyperglycemia in hospital patients is a common problem that’s poorly managed. “There’s an unmet need for an effective and safe glucose control, specifically in the underserved and understudied population of type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” he said. The use of the closed-loop system in inpatients with type 2 diabetes “remains untested until now,” Dr. Thabit added.

The 20 patients randomized to the closed-loop system spent an average of 61% of the whole study period within the sensor glucose target vs. 38% of those on conventional insulin therapy. The closed-loop patients also used comparable insulin daily on average: 62.6 U (±36.3 U) vs. 66.0 U (±39.6 U), Dr. Thabit said.

He noted that those on the closed-loop system did not have to announce meals to the control algorithm, or give any meal-time insulin – “we didn’t want to trouble our nurses with this, due to the increasing workload that health care professionals in the hospital currently face,” he said – and showed “significantly improved” nighttime control of glucose while “simultaneously reducing the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia”. “The closed loop may potentially be an effective and safe tool to manage hospital inpatient hyperglycemia in this particularly underserved population of patients whilst easing the burden of health care professionals in hospital,” he said.

The cost is not insignificant. The pump and sensor devices together with related consumables can cost up to £6,000 (about $8,600), but he did note the artificial pancreas device itself is reusable. The cost of the automated closed-loop glucose control system can also potentially be offset by the reduced time of health care professionals spent managing inpatient hyperglycemia safely. The study investigators are in the process of planning a larger trial, Dr. Thabit said.

Dr. Thabit had no financial disclosures. Some coauthors disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk; Medtronic MiniMed; Becton, Dickinson and Co.; Abbott Diabetes Care; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Cell Novo; Animas; Eli Lilly; B. Braun Melsungen; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland; and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

NEW ORLEANS – Having people with type 2 diabetes mellitus use an artificial pancreas during hospitalization has the potential to improve control of their glycemia when compared with conventional insulin therapy, based on the results of a small study of inpatients in the United Kingdom.

“This is the first study to show that automated subcutaneous closed-loop insulin delivery without meal-time insulin is feasible and safe in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” Dr. Hood Thabit of the University of Cambridge (England) reported at the ADA annual scientific sessions. “Closed-loop [delivery] increased time in target, with reduced glucose variability and reduced time spent hyperglycemic without actually increasing time spent hypoglycemic,” he said.

The study involved 40 general ward inpatients evenly assigned to the closed-loop system and conventional insulin therapy for 72 hours.

Dr. Thabit said hyperglycemia in hospital patients is a common problem that’s poorly managed. “There’s an unmet need for an effective and safe glucose control, specifically in the underserved and understudied population of type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” he said. The use of the closed-loop system in inpatients with type 2 diabetes “remains untested until now,” Dr. Thabit added.

The 20 patients randomized to the closed-loop system spent an average of 61% of the whole study period within the sensor glucose target vs. 38% of those on conventional insulin therapy. The closed-loop patients also used comparable insulin daily on average: 62.6 U (±36.3 U) vs. 66.0 U (±39.6 U), Dr. Thabit said.

He noted that those on the closed-loop system did not have to announce meals to the control algorithm, or give any meal-time insulin – “we didn’t want to trouble our nurses with this, due to the increasing workload that health care professionals in the hospital currently face,” he said – and showed “significantly improved” nighttime control of glucose while “simultaneously reducing the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia”. “The closed loop may potentially be an effective and safe tool to manage hospital inpatient hyperglycemia in this particularly underserved population of patients whilst easing the burden of health care professionals in hospital,” he said.

The cost is not insignificant. The pump and sensor devices together with related consumables can cost up to £6,000 (about $8,600), but he did note the artificial pancreas device itself is reusable. The cost of the automated closed-loop glucose control system can also potentially be offset by the reduced time of health care professionals spent managing inpatient hyperglycemia safely. The study investigators are in the process of planning a larger trial, Dr. Thabit said.

Dr. Thabit had no financial disclosures. Some coauthors disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk; Medtronic MiniMed; Becton, Dickinson and Co.; Abbott Diabetes Care; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Cell Novo; Animas; Eli Lilly; B. Braun Melsungen; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland; and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

NEW ORLEANS – Having people with type 2 diabetes mellitus use an artificial pancreas during hospitalization has the potential to improve control of their glycemia when compared with conventional insulin therapy, based on the results of a small study of inpatients in the United Kingdom.

“This is the first study to show that automated subcutaneous closed-loop insulin delivery without meal-time insulin is feasible and safe in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” Dr. Hood Thabit of the University of Cambridge (England) reported at the ADA annual scientific sessions. “Closed-loop [delivery] increased time in target, with reduced glucose variability and reduced time spent hyperglycemic without actually increasing time spent hypoglycemic,” he said.

The study involved 40 general ward inpatients evenly assigned to the closed-loop system and conventional insulin therapy for 72 hours.

Dr. Thabit said hyperglycemia in hospital patients is a common problem that’s poorly managed. “There’s an unmet need for an effective and safe glucose control, specifically in the underserved and understudied population of type 2 diabetes in the general wards,” he said. The use of the closed-loop system in inpatients with type 2 diabetes “remains untested until now,” Dr. Thabit added.

The 20 patients randomized to the closed-loop system spent an average of 61% of the whole study period within the sensor glucose target vs. 38% of those on conventional insulin therapy. The closed-loop patients also used comparable insulin daily on average: 62.6 U (±36.3 U) vs. 66.0 U (±39.6 U), Dr. Thabit said.

He noted that those on the closed-loop system did not have to announce meals to the control algorithm, or give any meal-time insulin – “we didn’t want to trouble our nurses with this, due to the increasing workload that health care professionals in the hospital currently face,” he said – and showed “significantly improved” nighttime control of glucose while “simultaneously reducing the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia”. “The closed loop may potentially be an effective and safe tool to manage hospital inpatient hyperglycemia in this particularly underserved population of patients whilst easing the burden of health care professionals in hospital,” he said.

The cost is not insignificant. The pump and sensor devices together with related consumables can cost up to £6,000 (about $8,600), but he did note the artificial pancreas device itself is reusable. The cost of the automated closed-loop glucose control system can also potentially be offset by the reduced time of health care professionals spent managing inpatient hyperglycemia safely. The study investigators are in the process of planning a larger trial, Dr. Thabit said.

Dr. Thabit had no financial disclosures. Some coauthors disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk; Medtronic MiniMed; Becton, Dickinson and Co.; Abbott Diabetes Care; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Cell Novo; Animas; Eli Lilly; B. Braun Melsungen; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland; and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:Hospitalized patients in the general ward with type 2 diabetes mellitus can maintain better glycemic control by using an artificial pancreas than by taking conventional therapy.

Major finding: Patients on the closed-loop system spent an average of 61% of the study period within the sensor glucose target vs. 38% for those on conventional insulin therapy.

Data source: A single-center study of 40 patients randomized to wear the artificial pancreas or take conventional therapy.

Disclosures: Dr. Thabit had no financial disclosures. Some coauthors disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk; Medtronic MiniMed; Becton, Dickinson and Co.; Abbott Diabetes Care; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Cell Novo; Animas; Eli Lilly; B. Braun Melsungen; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland; and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

Pioglitazone safe and effective for steatohepatitis in T2DM

Long-term pioglitazone is not only safe for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes but is associated with significant improvements in fatty liver disease outcomes, compared with placebo, research suggests.

Investigators randomized 101 individuals with biopsy-proven NASH and either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes to 18 months of 45 mg/day of pioglitazone or placebo, followed by an 18 month open-label phase of pioglitazone, in addition to a hypocaloric diet, according to a paper published online June 20 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Among patients randomized to pioglitazone, 58% achieved at least a two-point reduction in their NASH activity score, without a worsening of fibrosis, compared with only 17% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

The pioglitazone group also showed a significantly greater likelihood that their NASH would resolve, with 51% of the treatment group achieving resolution, compared with 19% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

Pioglitazone treatment was also associated with significantly greater improvements in steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning necrosis, as well as mean histologic scores and fibrosis scores (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M15-1774).

The study also showed that only 12% of the pioglitazone group showed progression of any fibrosis, compared with 28% of the placebo group (P = .039), while pioglitazone was associated with significant 2.5 kg weight gain over placebo.

“Because thiazolidinediones target insulin resistance and adipose tissue dysfunction or inflammation that promotes hepatic ‘lipotoxicity’ in NASH (which is also a prominent feature of T2DM), they may be more helpful for treating steatohepatitis in this population,” wrote Dr. Kenneth Cusi, from the division of endocrinology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted that there have been relatively few studies of pioglitazone and its effects on steatohepatitis in individuals with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

“This study also has implications for patients with prediabetes and NASH (about half of our participants) because hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for T2DM, even in nonobese patients,” the authors wrote. They suggested that future studies could explore whether the reversal of hepatic steatosis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with prediabetes may help to halt the development of type 2 diabetes.

The study was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the American Diabetes Association. One author reported nonfinancial support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals in the form of study medication and placebo, and grants and consultancies from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

This study extends previous observations of the therapeutic benefits of pioglitazone in NASH to include patients with impaired glucose regulation, but the use of pioglitazone beyond 18 months did not provide significant additional resolution of fibrosis, although it may retard further progression.

We believe that physicians should consider adding pioglitazone to their toolboxes when facing patients with NASH and diabetes, but the primary obstacle to the widespread use of pioglitazone remains its safety profile.

Thus, treatment should be considered for patients at the greatest risk (those with NASH and fibrosis) and should be balanced against the common risk for weight gain and the uncommon risks for fracture and heart failure.

Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Gomez is from the University of Seville, Spain, and Dr. Leon A. Adams is from the University of Western Australia, Perth. These comments were made in an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M16-1303). No conflicts of interest were declared.

This study extends previous observations of the therapeutic benefits of pioglitazone in NASH to include patients with impaired glucose regulation, but the use of pioglitazone beyond 18 months did not provide significant additional resolution of fibrosis, although it may retard further progression.

We believe that physicians should consider adding pioglitazone to their toolboxes when facing patients with NASH and diabetes, but the primary obstacle to the widespread use of pioglitazone remains its safety profile.

Thus, treatment should be considered for patients at the greatest risk (those with NASH and fibrosis) and should be balanced against the common risk for weight gain and the uncommon risks for fracture and heart failure.

Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Gomez is from the University of Seville, Spain, and Dr. Leon A. Adams is from the University of Western Australia, Perth. These comments were made in an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M16-1303). No conflicts of interest were declared.

This study extends previous observations of the therapeutic benefits of pioglitazone in NASH to include patients with impaired glucose regulation, but the use of pioglitazone beyond 18 months did not provide significant additional resolution of fibrosis, although it may retard further progression.

We believe that physicians should consider adding pioglitazone to their toolboxes when facing patients with NASH and diabetes, but the primary obstacle to the widespread use of pioglitazone remains its safety profile.

Thus, treatment should be considered for patients at the greatest risk (those with NASH and fibrosis) and should be balanced against the common risk for weight gain and the uncommon risks for fracture and heart failure.

Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Gomez is from the University of Seville, Spain, and Dr. Leon A. Adams is from the University of Western Australia, Perth. These comments were made in an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M16-1303). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Long-term pioglitazone is not only safe for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes but is associated with significant improvements in fatty liver disease outcomes, compared with placebo, research suggests.

Investigators randomized 101 individuals with biopsy-proven NASH and either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes to 18 months of 45 mg/day of pioglitazone or placebo, followed by an 18 month open-label phase of pioglitazone, in addition to a hypocaloric diet, according to a paper published online June 20 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Among patients randomized to pioglitazone, 58% achieved at least a two-point reduction in their NASH activity score, without a worsening of fibrosis, compared with only 17% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

The pioglitazone group also showed a significantly greater likelihood that their NASH would resolve, with 51% of the treatment group achieving resolution, compared with 19% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

Pioglitazone treatment was also associated with significantly greater improvements in steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning necrosis, as well as mean histologic scores and fibrosis scores (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M15-1774).

The study also showed that only 12% of the pioglitazone group showed progression of any fibrosis, compared with 28% of the placebo group (P = .039), while pioglitazone was associated with significant 2.5 kg weight gain over placebo.

“Because thiazolidinediones target insulin resistance and adipose tissue dysfunction or inflammation that promotes hepatic ‘lipotoxicity’ in NASH (which is also a prominent feature of T2DM), they may be more helpful for treating steatohepatitis in this population,” wrote Dr. Kenneth Cusi, from the division of endocrinology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted that there have been relatively few studies of pioglitazone and its effects on steatohepatitis in individuals with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

“This study also has implications for patients with prediabetes and NASH (about half of our participants) because hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for T2DM, even in nonobese patients,” the authors wrote. They suggested that future studies could explore whether the reversal of hepatic steatosis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with prediabetes may help to halt the development of type 2 diabetes.

The study was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the American Diabetes Association. One author reported nonfinancial support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals in the form of study medication and placebo, and grants and consultancies from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Long-term pioglitazone is not only safe for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes but is associated with significant improvements in fatty liver disease outcomes, compared with placebo, research suggests.

Investigators randomized 101 individuals with biopsy-proven NASH and either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes to 18 months of 45 mg/day of pioglitazone or placebo, followed by an 18 month open-label phase of pioglitazone, in addition to a hypocaloric diet, according to a paper published online June 20 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Among patients randomized to pioglitazone, 58% achieved at least a two-point reduction in their NASH activity score, without a worsening of fibrosis, compared with only 17% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

The pioglitazone group also showed a significantly greater likelihood that their NASH would resolve, with 51% of the treatment group achieving resolution, compared with 19% of the placebo group (P less than .001).

Pioglitazone treatment was also associated with significantly greater improvements in steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning necrosis, as well as mean histologic scores and fibrosis scores (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jun 20. doi: 10.7326/M15-1774).

The study also showed that only 12% of the pioglitazone group showed progression of any fibrosis, compared with 28% of the placebo group (P = .039), while pioglitazone was associated with significant 2.5 kg weight gain over placebo.

“Because thiazolidinediones target insulin resistance and adipose tissue dysfunction or inflammation that promotes hepatic ‘lipotoxicity’ in NASH (which is also a prominent feature of T2DM), they may be more helpful for treating steatohepatitis in this population,” wrote Dr. Kenneth Cusi, from the division of endocrinology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted that there have been relatively few studies of pioglitazone and its effects on steatohepatitis in individuals with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

“This study also has implications for patients with prediabetes and NASH (about half of our participants) because hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for T2DM, even in nonobese patients,” the authors wrote. They suggested that future studies could explore whether the reversal of hepatic steatosis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with prediabetes may help to halt the development of type 2 diabetes.

The study was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the American Diabetes Association. One author reported nonfinancial support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals in the form of study medication and placebo, and grants and consultancies from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Long-term pioglitazone is not only safe for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, but is associated with significant improvements in fatty liver disease outcomes.

Major finding: Among patients randomized to pioglitazone, 58% achieved at least a two-point reduction in their nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score, compared with only 17% of the placebo group.

Data source: Randomized placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in 101 individuals with biopsy-proven NASH and either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the American Diabetes Association. One author reported nonfinancial support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals in the form of study medication and placebo, and grants and consultancies from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

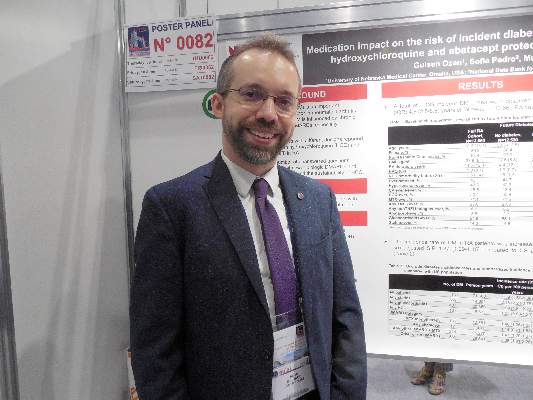

Comprehensive diabetic retinopathy screening challenging

NEW ORLEANS – Fewer than one-third of patients with diabetes being cared for by a public hospital system underwent screening for retinopathy within the past year, judging from the results from a survey of administrative data.

“Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of vision loss in the United States,” researchers led by Dr. David C. Ziemer wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In 2011, the age-adjusted percentage of adults with diagnosed diabetes reporting visual impairment was 17.6%. This is a pressing issue as the number of Americans with diabetic retinopathy is expected to double from 7.7 million in 2010 to 15.6 million in 2050.”

In an effort to plan for better diabetic retinopathy screening, Dr. Ziemer and his associates analyzed 2014 administrative data from 19,361 patients with diabetes who attended one of several clinics operated by the Atlanta-based Grady Health System. Diabetic retinopathy was considered complete if ophthalmology clinic, optometry, or retinal photograph visit was attended. The researchers also surveyed a convenience sample of 80 patients about their diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year.

The mean age of patients was 57 years, their mean hemoglobin A1c level was 7.8%, 59% were female, and 83% were African-American. Of the 19,361 patients, 5,595 (29%) underwent diabetic retinopathy screening and 13,766 (71%) did not. The unscreened had a mean of 1 clinic visit for diabetes care, compared with a mean of 3.1 for those who underwent screening (P less than .0005). In the analysis of administrative data, Dr. Ziemer, of the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, reported that 29% of patients underwent diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year, with variation by care site that ranged from 5% to 66%, and 5,000 had no diabetes continuity care visit.

Factors associated with increased diabetic retinopathy screening were treatment in a diabetes clinic (odds ratio, 2.8), treatment in a primary care clinic (OR, 2.1), and being older (OR, 1.03/year; P less than .001 for all associations), according to a multivariable analysis. Factors associated with decreased diabetic retinopathy screening were Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 0.7) and having a mental health diagnosis (OR, .8; P less than .001 for both associations). The researchers also found that having an in-clinic eye screening doubled the proportion of diabetic retinopathy screenings (48% vs. 22%) and decreased the number of screenings done in an outside clinic (45% vs. 95%).

Of the 80 patients who completed the survey, 68% reported that they underwent diabetic retinopathy screening within the past year, which was in contrast to the 29% reported by administrative data. In addition, 50% of survey respondents who did not undergo diabetic retinopathy screening reported that they received a referral, yet more than 40% failed to honor eye appointments. “The first barrier to address is people who don’t keep appointments,” Dr. Ziemer said in an interview. “Getting people in care is one issue. Having the capacity is another. That’s a real problem.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Ziemer reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Fewer than one-third of patients with diabetes being cared for by a public hospital system underwent screening for retinopathy within the past year, judging from the results from a survey of administrative data.

“Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of vision loss in the United States,” researchers led by Dr. David C. Ziemer wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In 2011, the age-adjusted percentage of adults with diagnosed diabetes reporting visual impairment was 17.6%. This is a pressing issue as the number of Americans with diabetic retinopathy is expected to double from 7.7 million in 2010 to 15.6 million in 2050.”

In an effort to plan for better diabetic retinopathy screening, Dr. Ziemer and his associates analyzed 2014 administrative data from 19,361 patients with diabetes who attended one of several clinics operated by the Atlanta-based Grady Health System. Diabetic retinopathy was considered complete if ophthalmology clinic, optometry, or retinal photograph visit was attended. The researchers also surveyed a convenience sample of 80 patients about their diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year.

The mean age of patients was 57 years, their mean hemoglobin A1c level was 7.8%, 59% were female, and 83% were African-American. Of the 19,361 patients, 5,595 (29%) underwent diabetic retinopathy screening and 13,766 (71%) did not. The unscreened had a mean of 1 clinic visit for diabetes care, compared with a mean of 3.1 for those who underwent screening (P less than .0005). In the analysis of administrative data, Dr. Ziemer, of the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, reported that 29% of patients underwent diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year, with variation by care site that ranged from 5% to 66%, and 5,000 had no diabetes continuity care visit.

Factors associated with increased diabetic retinopathy screening were treatment in a diabetes clinic (odds ratio, 2.8), treatment in a primary care clinic (OR, 2.1), and being older (OR, 1.03/year; P less than .001 for all associations), according to a multivariable analysis. Factors associated with decreased diabetic retinopathy screening were Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 0.7) and having a mental health diagnosis (OR, .8; P less than .001 for both associations). The researchers also found that having an in-clinic eye screening doubled the proportion of diabetic retinopathy screenings (48% vs. 22%) and decreased the number of screenings done in an outside clinic (45% vs. 95%).

Of the 80 patients who completed the survey, 68% reported that they underwent diabetic retinopathy screening within the past year, which was in contrast to the 29% reported by administrative data. In addition, 50% of survey respondents who did not undergo diabetic retinopathy screening reported that they received a referral, yet more than 40% failed to honor eye appointments. “The first barrier to address is people who don’t keep appointments,” Dr. Ziemer said in an interview. “Getting people in care is one issue. Having the capacity is another. That’s a real problem.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Ziemer reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Fewer than one-third of patients with diabetes being cared for by a public hospital system underwent screening for retinopathy within the past year, judging from the results from a survey of administrative data.

“Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of vision loss in the United States,” researchers led by Dr. David C. Ziemer wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In 2011, the age-adjusted percentage of adults with diagnosed diabetes reporting visual impairment was 17.6%. This is a pressing issue as the number of Americans with diabetic retinopathy is expected to double from 7.7 million in 2010 to 15.6 million in 2050.”

In an effort to plan for better diabetic retinopathy screening, Dr. Ziemer and his associates analyzed 2014 administrative data from 19,361 patients with diabetes who attended one of several clinics operated by the Atlanta-based Grady Health System. Diabetic retinopathy was considered complete if ophthalmology clinic, optometry, or retinal photograph visit was attended. The researchers also surveyed a convenience sample of 80 patients about their diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year.

The mean age of patients was 57 years, their mean hemoglobin A1c level was 7.8%, 59% were female, and 83% were African-American. Of the 19,361 patients, 5,595 (29%) underwent diabetic retinopathy screening and 13,766 (71%) did not. The unscreened had a mean of 1 clinic visit for diabetes care, compared with a mean of 3.1 for those who underwent screening (P less than .0005). In the analysis of administrative data, Dr. Ziemer, of the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, reported that 29% of patients underwent diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year, with variation by care site that ranged from 5% to 66%, and 5,000 had no diabetes continuity care visit.

Factors associated with increased diabetic retinopathy screening were treatment in a diabetes clinic (odds ratio, 2.8), treatment in a primary care clinic (OR, 2.1), and being older (OR, 1.03/year; P less than .001 for all associations), according to a multivariable analysis. Factors associated with decreased diabetic retinopathy screening were Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 0.7) and having a mental health diagnosis (OR, .8; P less than .001 for both associations). The researchers also found that having an in-clinic eye screening doubled the proportion of diabetic retinopathy screenings (48% vs. 22%) and decreased the number of screenings done in an outside clinic (45% vs. 95%).

Of the 80 patients who completed the survey, 68% reported that they underwent diabetic retinopathy screening within the past year, which was in contrast to the 29% reported by administrative data. In addition, 50% of survey respondents who did not undergo diabetic retinopathy screening reported that they received a referral, yet more than 40% failed to honor eye appointments. “The first barrier to address is people who don’t keep appointments,” Dr. Ziemer said in an interview. “Getting people in care is one issue. Having the capacity is another. That’s a real problem.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Ziemer reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Some 71% of diabetes patients did not undergo screening for diabetic retinopathy.

Major finding: Only 29% of patients underwent diabetic retinopathy screening in the past year, with variation by care site that ranged from 5% to 66%.

Data source: An analysis of administrative data from 19,361 patients with diabetes who attended one of several clinics operated by the Atlanta-based Grady Health System in 2014.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Ziemer reported having no financial disclosures.

Phentermine-topiramate shows best chance of weight loss at 1 year

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight by 1 year, compared with four other weight-loss drugs.

Major finding: Patients taking phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants.

Disclosures: Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

Hydroxychloroquine, abatacept linked with reduced type 2 diabetes

LONDON – U.S. rheumatoid arthritis patients had a significantly reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when on treatment with either hydroxychloroquine or abatacept in an analysis of more than 13,000 patients enrolled in a U.S. national registry during 2000-2015.

The same analysis also showed statistically significant increases in the risk for new-onset type 2 diabetes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with a glucocorticoid or a statin, Kaleb Michaud, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Our findings can inform clinicians about determining appropriate treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis patients at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Michaud, an epidemiologist at the University of Nebraska in Omaha and also codirector of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases in Wichita, Kan., the source of the data used in his study.

Hydroxychloroquine, a relatively inexpensive drug that’s often used in RA patients in combination with other drugs, might be a good agent to consider adding to the therapeutic mix of RA patients at risk for developing type 2 diabetes, he said in an interview. Although the implications of this finding for the use of abatacept (Orencia) are less clear, it is a signal of a novel benefit from the drug that merits further study, Dr. Michaud said.

The findings also suggest that, when rheumatoid arthritis patients receive statin treatment, they are candidates for more intensive monitoring of diabetes onset, he added.

His analysis focused on the 13,669 RA patients who participated in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases for at least a year during 2000-2015 and had not been diagnosed as having diabetes of any type at the time they entered the registry. During a median 4.6 years of follow-up, 1,139 patients either self-reported receiving a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or began treatment with a hypoglycemic medication. Patients averaged about 59 years old at the time they entered the registry, and about 80% were women.

Dr. Michaud and his associates assessed the incidence rate of type 2 diabetes according to six categories of RA treatment: methotrexate monotherapy, which they used as the reference group; any treatment with abatacept with or without methotrexate; any treatment with hydroxychloroquine; any treatment with a glucocorticoid; treatment with any other disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) with methotrexate; and treatment with any other DMARD without methotrexate or no DMARD treatment. A seventh treatment category was treatment with a statin.

A series of time-varying Cox proportional hazard models that adjusted for sociodemographic variables, comorbidities, body mass index, and measures of RA severity showed that, when compared with methotrexate monotherapy, patients treated with abatacept had a statistically significant 48% reduced rate of developing diabetes, and those treated with hydroxychloroquine had a statistically significant 33% reduced diabetes incidence, they reported.

In contrast, compared with methotrexate monotherapy, treatment with a glucocorticoid linked with a statistically significant 31% increased rate of type 2 diabetes, and treatment with a statin linked with a statistically significant 56% increased rate of diabetes. Other forms of DMARD treatment, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and other biologic DMARDs, had no statistically significant link with diabetes development.

Dr. Michaud also reported additional analyses that further defined the associations between hydroxychloroquine treatment and reduced diabetes incidence: The reduction in diabetes incidence became statistically significant in patients only when they had received the drug for at least 2 years. The link with reduced diabetes incidence seemed dose dependent, with a stronger protective effect in patients who received at least 400 mg/day. Also, the strength of the protection waned in patients who had discontinued hydroxychloroquine for at least 6 months, and the protective effect completely disappeared once patients were off hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 year. Finally, the link between hydroxychloroquine use and reduced diabetes incidence also was statistically significant in patients who concurrently received a glucocorticoid, but a significant protective association disappeared in patients who received a statin as well as hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Michaud had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LONDON – U.S. rheumatoid arthritis patients had a significantly reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when on treatment with either hydroxychloroquine or abatacept in an analysis of more than 13,000 patients enrolled in a U.S. national registry during 2000-2015.

The same analysis also showed statistically significant increases in the risk for new-onset type 2 diabetes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with a glucocorticoid or a statin, Kaleb Michaud, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Our findings can inform clinicians about determining appropriate treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis patients at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Michaud, an epidemiologist at the University of Nebraska in Omaha and also codirector of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases in Wichita, Kan., the source of the data used in his study.

Hydroxychloroquine, a relatively inexpensive drug that’s often used in RA patients in combination with other drugs, might be a good agent to consider adding to the therapeutic mix of RA patients at risk for developing type 2 diabetes, he said in an interview. Although the implications of this finding for the use of abatacept (Orencia) are less clear, it is a signal of a novel benefit from the drug that merits further study, Dr. Michaud said.

The findings also suggest that, when rheumatoid arthritis patients receive statin treatment, they are candidates for more intensive monitoring of diabetes onset, he added.

His analysis focused on the 13,669 RA patients who participated in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases for at least a year during 2000-2015 and had not been diagnosed as having diabetes of any type at the time they entered the registry. During a median 4.6 years of follow-up, 1,139 patients either self-reported receiving a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or began treatment with a hypoglycemic medication. Patients averaged about 59 years old at the time they entered the registry, and about 80% were women.

Dr. Michaud and his associates assessed the incidence rate of type 2 diabetes according to six categories of RA treatment: methotrexate monotherapy, which they used as the reference group; any treatment with abatacept with or without methotrexate; any treatment with hydroxychloroquine; any treatment with a glucocorticoid; treatment with any other disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) with methotrexate; and treatment with any other DMARD without methotrexate or no DMARD treatment. A seventh treatment category was treatment with a statin.

A series of time-varying Cox proportional hazard models that adjusted for sociodemographic variables, comorbidities, body mass index, and measures of RA severity showed that, when compared with methotrexate monotherapy, patients treated with abatacept had a statistically significant 48% reduced rate of developing diabetes, and those treated with hydroxychloroquine had a statistically significant 33% reduced diabetes incidence, they reported.

In contrast, compared with methotrexate monotherapy, treatment with a glucocorticoid linked with a statistically significant 31% increased rate of type 2 diabetes, and treatment with a statin linked with a statistically significant 56% increased rate of diabetes. Other forms of DMARD treatment, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and other biologic DMARDs, had no statistically significant link with diabetes development.

Dr. Michaud also reported additional analyses that further defined the associations between hydroxychloroquine treatment and reduced diabetes incidence: The reduction in diabetes incidence became statistically significant in patients only when they had received the drug for at least 2 years. The link with reduced diabetes incidence seemed dose dependent, with a stronger protective effect in patients who received at least 400 mg/day. Also, the strength of the protection waned in patients who had discontinued hydroxychloroquine for at least 6 months, and the protective effect completely disappeared once patients were off hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 year. Finally, the link between hydroxychloroquine use and reduced diabetes incidence also was statistically significant in patients who concurrently received a glucocorticoid, but a significant protective association disappeared in patients who received a statin as well as hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Michaud had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LONDON – U.S. rheumatoid arthritis patients had a significantly reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when on treatment with either hydroxychloroquine or abatacept in an analysis of more than 13,000 patients enrolled in a U.S. national registry during 2000-2015.

The same analysis also showed statistically significant increases in the risk for new-onset type 2 diabetes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with a glucocorticoid or a statin, Kaleb Michaud, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Our findings can inform clinicians about determining appropriate treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis patients at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Michaud, an epidemiologist at the University of Nebraska in Omaha and also codirector of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases in Wichita, Kan., the source of the data used in his study.

Hydroxychloroquine, a relatively inexpensive drug that’s often used in RA patients in combination with other drugs, might be a good agent to consider adding to the therapeutic mix of RA patients at risk for developing type 2 diabetes, he said in an interview. Although the implications of this finding for the use of abatacept (Orencia) are less clear, it is a signal of a novel benefit from the drug that merits further study, Dr. Michaud said.

The findings also suggest that, when rheumatoid arthritis patients receive statin treatment, they are candidates for more intensive monitoring of diabetes onset, he added.

His analysis focused on the 13,669 RA patients who participated in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases for at least a year during 2000-2015 and had not been diagnosed as having diabetes of any type at the time they entered the registry. During a median 4.6 years of follow-up, 1,139 patients either self-reported receiving a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or began treatment with a hypoglycemic medication. Patients averaged about 59 years old at the time they entered the registry, and about 80% were women.

Dr. Michaud and his associates assessed the incidence rate of type 2 diabetes according to six categories of RA treatment: methotrexate monotherapy, which they used as the reference group; any treatment with abatacept with or without methotrexate; any treatment with hydroxychloroquine; any treatment with a glucocorticoid; treatment with any other disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) with methotrexate; and treatment with any other DMARD without methotrexate or no DMARD treatment. A seventh treatment category was treatment with a statin.

A series of time-varying Cox proportional hazard models that adjusted for sociodemographic variables, comorbidities, body mass index, and measures of RA severity showed that, when compared with methotrexate monotherapy, patients treated with abatacept had a statistically significant 48% reduced rate of developing diabetes, and those treated with hydroxychloroquine had a statistically significant 33% reduced diabetes incidence, they reported.

In contrast, compared with methotrexate monotherapy, treatment with a glucocorticoid linked with a statistically significant 31% increased rate of type 2 diabetes, and treatment with a statin linked with a statistically significant 56% increased rate of diabetes. Other forms of DMARD treatment, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and other biologic DMARDs, had no statistically significant link with diabetes development.

Dr. Michaud also reported additional analyses that further defined the associations between hydroxychloroquine treatment and reduced diabetes incidence: The reduction in diabetes incidence became statistically significant in patients only when they had received the drug for at least 2 years. The link with reduced diabetes incidence seemed dose dependent, with a stronger protective effect in patients who received at least 400 mg/day. Also, the strength of the protection waned in patients who had discontinued hydroxychloroquine for at least 6 months, and the protective effect completely disappeared once patients were off hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 year. Finally, the link between hydroxychloroquine use and reduced diabetes incidence also was statistically significant in patients who concurrently received a glucocorticoid, but a significant protective association disappeared in patients who received a statin as well as hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Michaud had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE EULAR 2016 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: U.S. rheumatoid arthritis patients on hydroxychloroquine or abatacept had a significantly reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with patients on methotrexate monotherapy.

Major finding: Hydroxychloroquine cut type 2 diabetes incidence by 33% and abatacept cut it by 48%, compared with patients on methotrexate monotherapy.

Data source: Analysis of data collected from 13,669 U.S. rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in a registry during 2000-2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Michaud had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

Bevacizumab offers best value of anti-VEGF drugs to treat DME

Despite recent data showing that aflibercept is the most effective anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment available for patients with diabetic macular edema, bevacizumab is still by far the best drug option available from a cost-effectiveness perspective, according to a post hoc analysis.

Dr. Joshua D. Stein of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors analyzed the anti-VEGF drugs prescribed to 624 diabetic macular edema (DME) patients – 209 taking aflibercept, 207 taking bevacizumab, and 208 taking ranibizumab – enrolled in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Comparative Effectiveness Trial for incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

“On the basis of 2015 wholesale acquisition costs, aflibercept (2 mg) costs $1,850, ranibizumab (0.3mg) costs $1,170, and bevacizumab repackaged at compounding pharmacies into syringes for ophthalmologic use containing 1.25 mg of bevacizumab costs approximately $60 per dose,” Dr. Stein and his coauthors wrote (JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 June 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1669). “Considering that these medicines may be given 9 to 11 times in the first year of treatment and, on average, 17 times during 5 years, total costs can be substantial.”

Data from the randomized clinical trial were used to calculate projected benefit, costs, and cost-effectiveness of aflibercept and ranibizumab compared with bevacizumab as baseline. In addition, the investigators also determined both ICERs and Quality Life-Adjusted Years (QALY) for each drug over periods of 1 and 10 years. Results indicated that for 1 year of treatment, the ICER of aflibercept was $1.11 million per QALY and for ranibizumab, $1.73 million per QALY. Over the course of 10 years, aflibercept would come out to $349,000 per QALY, while ranibizumab would be $603,000 per QALY. In an analysis of a subgroup with highly reduced eyesight due to DME, the 10-year ICER of aflibercept would be $287,000 per QALY and for ranibizumab, $817,000, according to Dr. Stein and his associates.

Over a 1-year period, bevacizumab would cost $4,100, compared to $26,100 for aflibercept and $18,600 for ranibizumab. Over a 10-year period, those costs would jump up to $102,500 for aflibercept and $79,400 for ranibizumab, while bevacizumab would cost $39,800. Overall, the costs of aflibercept and ranibizumab would have to decrease by 69% and 80%, respectively, for the costs to become competitive with bevacizumab.

“Aflibercept (2.0 mg) and ranibizumab (0.3 mg) are not cost-effective relative to bevacizumab for treatment of DME unless their prices decrease substantially [and] in contexts where bevacizumab is unavailable for DME treatment, aflibercept is not cost-effective relative to ranibizumab,” the authors concluded, adding that bevacizumab makes the most sense as a primary anti-VEGF treatment because it allows for the greatest overall value.

The National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Stein did not report any relevant financial disclosures; however, other coauthors reported potentially relevant disclosures.

Despite recent data showing that aflibercept is the most effective anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment available for patients with diabetic macular edema, bevacizumab is still by far the best drug option available from a cost-effectiveness perspective, according to a post hoc analysis.

Dr. Joshua D. Stein of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors analyzed the anti-VEGF drugs prescribed to 624 diabetic macular edema (DME) patients – 209 taking aflibercept, 207 taking bevacizumab, and 208 taking ranibizumab – enrolled in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Comparative Effectiveness Trial for incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

“On the basis of 2015 wholesale acquisition costs, aflibercept (2 mg) costs $1,850, ranibizumab (0.3mg) costs $1,170, and bevacizumab repackaged at compounding pharmacies into syringes for ophthalmologic use containing 1.25 mg of bevacizumab costs approximately $60 per dose,” Dr. Stein and his coauthors wrote (JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 June 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1669). “Considering that these medicines may be given 9 to 11 times in the first year of treatment and, on average, 17 times during 5 years, total costs can be substantial.”

Data from the randomized clinical trial were used to calculate projected benefit, costs, and cost-effectiveness of aflibercept and ranibizumab compared with bevacizumab as baseline. In addition, the investigators also determined both ICERs and Quality Life-Adjusted Years (QALY) for each drug over periods of 1 and 10 years. Results indicated that for 1 year of treatment, the ICER of aflibercept was $1.11 million per QALY and for ranibizumab, $1.73 million per QALY. Over the course of 10 years, aflibercept would come out to $349,000 per QALY, while ranibizumab would be $603,000 per QALY. In an analysis of a subgroup with highly reduced eyesight due to DME, the 10-year ICER of aflibercept would be $287,000 per QALY and for ranibizumab, $817,000, according to Dr. Stein and his associates.

Over a 1-year period, bevacizumab would cost $4,100, compared to $26,100 for aflibercept and $18,600 for ranibizumab. Over a 10-year period, those costs would jump up to $102,500 for aflibercept and $79,400 for ranibizumab, while bevacizumab would cost $39,800. Overall, the costs of aflibercept and ranibizumab would have to decrease by 69% and 80%, respectively, for the costs to become competitive with bevacizumab.

“Aflibercept (2.0 mg) and ranibizumab (0.3 mg) are not cost-effective relative to bevacizumab for treatment of DME unless their prices decrease substantially [and] in contexts where bevacizumab is unavailable for DME treatment, aflibercept is not cost-effective relative to ranibizumab,” the authors concluded, adding that bevacizumab makes the most sense as a primary anti-VEGF treatment because it allows for the greatest overall value.

The National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Stein did not report any relevant financial disclosures; however, other coauthors reported potentially relevant disclosures.

Despite recent data showing that aflibercept is the most effective anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment available for patients with diabetic macular edema, bevacizumab is still by far the best drug option available from a cost-effectiveness perspective, according to a post hoc analysis.

Dr. Joshua D. Stein of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors analyzed the anti-VEGF drugs prescribed to 624 diabetic macular edema (DME) patients – 209 taking aflibercept, 207 taking bevacizumab, and 208 taking ranibizumab – enrolled in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Comparative Effectiveness Trial for incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

“On the basis of 2015 wholesale acquisition costs, aflibercept (2 mg) costs $1,850, ranibizumab (0.3mg) costs $1,170, and bevacizumab repackaged at compounding pharmacies into syringes for ophthalmologic use containing 1.25 mg of bevacizumab costs approximately $60 per dose,” Dr. Stein and his coauthors wrote (JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 June 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1669). “Considering that these medicines may be given 9 to 11 times in the first year of treatment and, on average, 17 times during 5 years, total costs can be substantial.”

Data from the randomized clinical trial were used to calculate projected benefit, costs, and cost-effectiveness of aflibercept and ranibizumab compared with bevacizumab as baseline. In addition, the investigators also determined both ICERs and Quality Life-Adjusted Years (QALY) for each drug over periods of 1 and 10 years. Results indicated that for 1 year of treatment, the ICER of aflibercept was $1.11 million per QALY and for ranibizumab, $1.73 million per QALY. Over the course of 10 years, aflibercept would come out to $349,000 per QALY, while ranibizumab would be $603,000 per QALY. In an analysis of a subgroup with highly reduced eyesight due to DME, the 10-year ICER of aflibercept would be $287,000 per QALY and for ranibizumab, $817,000, according to Dr. Stein and his associates.

Over a 1-year period, bevacizumab would cost $4,100, compared to $26,100 for aflibercept and $18,600 for ranibizumab. Over a 10-year period, those costs would jump up to $102,500 for aflibercept and $79,400 for ranibizumab, while bevacizumab would cost $39,800. Overall, the costs of aflibercept and ranibizumab would have to decrease by 69% and 80%, respectively, for the costs to become competitive with bevacizumab.

“Aflibercept (2.0 mg) and ranibizumab (0.3 mg) are not cost-effective relative to bevacizumab for treatment of DME unless their prices decrease substantially [and] in contexts where bevacizumab is unavailable for DME treatment, aflibercept is not cost-effective relative to ranibizumab,” the authors concluded, adding that bevacizumab makes the most sense as a primary anti-VEGF treatment because it allows for the greatest overall value.

The National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Stein did not report any relevant financial disclosures; however, other coauthors reported potentially relevant disclosures.

FROM JAMA OPHTHALMOLOGY

Key clinical point: Bevacizumab remains the best option, in terms of price and value, over aflibercept and ranibizumab for treatment of diabetic macular edema.

Major finding: Based on incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) over 1- and 10-year periods, the costs of aflibercept and ranibizumab would have to decrease by 69% and 80%, respectively, to match the cost of bevacizumab over the same time periods.

Data source: Post hoc analysis of patients enrolled in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Comparative Effectiveness Trial at 1-year follow-up.

Disclosures: The National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Stein did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Postpartum glycemic screening rates are low for women with GDM history

Most women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are not receiving recommended glycemic screenings in their first postpartum year. And screening rates vary based on geography, race, and use of antiglycemic medication in pregnancy, according to the results of a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) at 6-12 weeks postpartum with either fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). A hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) is not recommended in the early postpartum period.

Dr. Emma Morton Eggleston of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of medical records from a large U.S. health plan database to determine the rates of glycemic screenings – 75-g OGTT, HBA1c only, FPG only, or HbA1c plus FPG – in women with a history of GDM who were enrolled in the health plan from 2000-2012.

Rates were also measured for specific geographic regions, races/ethnicities, and patient clinical characteristics, including comorbidity in or before pregnancy, a visit to a nutritionist or diabetes educator during pregnancy, a visit to an endocrinologist during pregnancy, and the use of any antiglycemic agent during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:159-67. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001467).

Of all 447,556 women continuously enrolled in the health plan for 1 year before and after delivery, 32,253 (7.2%) had a history of GDM. The majority of women (76.1%) did not receive any of the glycemic screening tests in their first postpartum year.

The rates of these recommended tests were found to be low in general, although improvements in rates were noted between 2001 and 2011 for all but FPG alone, which declined from 7% within 12 weeks postpartum to 2% (adjusted odds ratio, 0.2). Conversely, the rate of receiving a 75-g OGTT within 12 weeks postpartum increased from 3% to 8% (adjusted OR, 3.2).

Geography was a predictor of postpartum screening. Women who lived in the West were the most likely to receive any screening within 12 weeks (18%) and at 1 year (31%). Among those who were screened, women in the West were most likely to receive a 75-g OGTT within 12 weeks (36%), compared with women in the Northeast (19%) and South (18%).

Race also played a role. Black women were the least likely to receive a 75-g OGTT and the most likely to receive HbA1c alone, even though this group has the highest rates of conversion to type 2 diabetes.

The strongest predictor of screening was the use of antiglycemic medication during pregnancy, according to the study. Women on antiglycemic medication in pregnancy (21%) were twice as likely to receive any type of screening, compared with women who were not on medication. Women who saw a nutritionist or diabetes educator during pregnancy, as well as those who saw an endocrinologist, were also more likely to receive any type of glycemic screening.

“Whether at the level of health system or population, quality improvement efforts must identify effective means of postpartum screening that are feasible for both women and health care providers and based on risk factors rather than geography or disparities in care,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Most women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are not receiving recommended glycemic screenings in their first postpartum year. And screening rates vary based on geography, race, and use of antiglycemic medication in pregnancy, according to the results of a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) at 6-12 weeks postpartum with either fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). A hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) is not recommended in the early postpartum period.

Dr. Emma Morton Eggleston of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of medical records from a large U.S. health plan database to determine the rates of glycemic screenings – 75-g OGTT, HBA1c only, FPG only, or HbA1c plus FPG – in women with a history of GDM who were enrolled in the health plan from 2000-2012.

Rates were also measured for specific geographic regions, races/ethnicities, and patient clinical characteristics, including comorbidity in or before pregnancy, a visit to a nutritionist or diabetes educator during pregnancy, a visit to an endocrinologist during pregnancy, and the use of any antiglycemic agent during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:159-67. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001467).

Of all 447,556 women continuously enrolled in the health plan for 1 year before and after delivery, 32,253 (7.2%) had a history of GDM. The majority of women (76.1%) did not receive any of the glycemic screening tests in their first postpartum year.

The rates of these recommended tests were found to be low in general, although improvements in rates were noted between 2001 and 2011 for all but FPG alone, which declined from 7% within 12 weeks postpartum to 2% (adjusted odds ratio, 0.2). Conversely, the rate of receiving a 75-g OGTT within 12 weeks postpartum increased from 3% to 8% (adjusted OR, 3.2).

Geography was a predictor of postpartum screening. Women who lived in the West were the most likely to receive any screening within 12 weeks (18%) and at 1 year (31%). Among those who were screened, women in the West were most likely to receive a 75-g OGTT within 12 weeks (36%), compared with women in the Northeast (19%) and South (18%).

Race also played a role. Black women were the least likely to receive a 75-g OGTT and the most likely to receive HbA1c alone, even though this group has the highest rates of conversion to type 2 diabetes.

The strongest predictor of screening was the use of antiglycemic medication during pregnancy, according to the study. Women on antiglycemic medication in pregnancy (21%) were twice as likely to receive any type of screening, compared with women who were not on medication. Women who saw a nutritionist or diabetes educator during pregnancy, as well as those who saw an endocrinologist, were also more likely to receive any type of glycemic screening.

“Whether at the level of health system or population, quality improvement efforts must identify effective means of postpartum screening that are feasible for both women and health care providers and based on risk factors rather than geography or disparities in care,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Most women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are not receiving recommended glycemic screenings in their first postpartum year. And screening rates vary based on geography, race, and use of antiglycemic medication in pregnancy, according to the results of a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) at 6-12 weeks postpartum with either fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). A hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) is not recommended in the early postpartum period.

Dr. Emma Morton Eggleston of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of medical records from a large U.S. health plan database to determine the rates of glycemic screenings – 75-g OGTT, HBA1c only, FPG only, or HbA1c plus FPG – in women with a history of GDM who were enrolled in the health plan from 2000-2012.

Rates were also measured for specific geographic regions, races/ethnicities, and patient clinical characteristics, including comorbidity in or before pregnancy, a visit to a nutritionist or diabetes educator during pregnancy, a visit to an endocrinologist during pregnancy, and the use of any antiglycemic agent during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:159-67. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001467).

Of all 447,556 women continuously enrolled in the health plan for 1 year before and after delivery, 32,253 (7.2%) had a history of GDM. The majority of women (76.1%) did not receive any of the glycemic screening tests in their first postpartum year.

The rates of these recommended tests were found to be low in general, although improvements in rates were noted between 2001 and 2011 for all but FPG alone, which declined from 7% within 12 weeks postpartum to 2% (adjusted odds ratio, 0.2). Conversely, the rate of receiving a 75-g OGTT within 12 weeks postpartum increased from 3% to 8% (adjusted OR, 3.2).