User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Smartphone app simultaneously improves multiple chronic disease risk behaviors

ORLANDO – A 12-week intervention involving a smartphone app and weekly coaching by telephone resulted in sustained, clinically meaningful improvement in multiple unhealthy diet and activity behaviors in the randomized, controlled Make Better Choices 2 study.

“It’s far more possible than I would have believed to produce sustained, large-magnitude changes in cardiovascular risk behaviors without using large financial incentives through the use of technologic support and a scalable approach to coaching,” principal investigator Bonnie J. Spring, Ph.D., said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is an example of what preventive medicine experts term “primordial prevention.” It’s intervention further upstream than primary prevention, which addresses the standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors before a cardiovascular event has occurred. Primordial prevention addresses the unhealthy behaviors that eventually lead to the standard risk factors.

Make Better Choices 2 included 212 adults, all of whom had four unhealthy behaviors of interest: low fruit and vegetable intake, high consumption of saturated fat, low levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, and excessive sedentary leisure TV and computer screen time.

The smartphone app was used for self-monitoring on the journey toward goal attainment. The data were uploaded regularly to the remote coach, who provided individualized instruction weekly for 3 months, then every 2 weeks during the next 3 months, and monthly for the final 3 months, explained Dr. Spring, professor of preventive medicine and director of the Center for Behavior and Health at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study expanded upon the success of the earlier 204-subject Make Better Choices 1 study, which showed that targeting two of the four unhealthy behaviors resulted in efficiently synergistic improvement in all four (Arch Intern Med. 2012 May 28;172[10]:789-96). However, in the earlier trial, participants were paid $175 if they reached their goals. In Make Better Choices 2, Dr. Spring and her coworkers wanted to see if behavioral change could be achieved without a large financial incentive.

Make Better Choices 2 participants were randomized to one of three study arms: simultaneous targeting of fruit and vegetable intake, sedentary screen time, and low moderate to vigorous physical activity; sequential targeting of fruit/vegetables and screen time followed by the physical activity intervention; or a control group that received instruction on reducing stress and improving sleep.

The simultaneous and sequential interventions proved equally effective. And as in Make Better Choices 1, a carryover effect was seen: At 9 months, not only was fruit and vegetable consumption increased by 5.9 servings per day, compared with baseline and leisure screen time reduced by 2 hours and 7 minutes per day, but participants reduced their saturated fat intake by an absolute 3.7% of total calories consumed daily, even though saturated fat wasn’t targeted.

“We think the improvement in saturated fat intake was due mostly to cutting down on hand to mouth snacking behavior by decreasing TV time,” she explained.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity time was increased by an average of 16 minutes per day in the two active treatment arms, compared with controls at 6 months. However, at 9 months, there was no significant difference among the three groups.

“The hardest behavior change for us to initiate and maintain is moderate to vigorous physical activity. I think that warrants more research,” according to Dr. Spring.

Adherence was good, with roughly an 18% dropout rate through 9 months in each study arm.

Session moderator Dr. Sidney C. Smith of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, noted that only about 25% of participants in the trial were men. He’s observed a similarly skewed ratio in other behavioral studies, and he wondered why, given that men have their acute MIs an average of 10 years earlier than women.

“This is a classic challenge in behavior intervention trials. It’s very difficult to get men to enroll,” Dr. Spring replied. “There’s starting to be a body of work trying to address this challenge.”

She added that she believes for some men it’s an issue of control. They want to do things their way, and they confuse support with control.

“This is one of the hopes of having technology available: If you’re a do-it-yourselfer, here are tools to help you do it yourself,” Dr. Spring said.

Once men get on board, however, a consistent finding in behavioral intervention studies is that the strategies work as well in men as in women, she observed.

Make Better Choices 2 was funded by Northwestern University and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Spring reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – A 12-week intervention involving a smartphone app and weekly coaching by telephone resulted in sustained, clinically meaningful improvement in multiple unhealthy diet and activity behaviors in the randomized, controlled Make Better Choices 2 study.

“It’s far more possible than I would have believed to produce sustained, large-magnitude changes in cardiovascular risk behaviors without using large financial incentives through the use of technologic support and a scalable approach to coaching,” principal investigator Bonnie J. Spring, Ph.D., said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is an example of what preventive medicine experts term “primordial prevention.” It’s intervention further upstream than primary prevention, which addresses the standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors before a cardiovascular event has occurred. Primordial prevention addresses the unhealthy behaviors that eventually lead to the standard risk factors.

Make Better Choices 2 included 212 adults, all of whom had four unhealthy behaviors of interest: low fruit and vegetable intake, high consumption of saturated fat, low levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, and excessive sedentary leisure TV and computer screen time.

The smartphone app was used for self-monitoring on the journey toward goal attainment. The data were uploaded regularly to the remote coach, who provided individualized instruction weekly for 3 months, then every 2 weeks during the next 3 months, and monthly for the final 3 months, explained Dr. Spring, professor of preventive medicine and director of the Center for Behavior and Health at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study expanded upon the success of the earlier 204-subject Make Better Choices 1 study, which showed that targeting two of the four unhealthy behaviors resulted in efficiently synergistic improvement in all four (Arch Intern Med. 2012 May 28;172[10]:789-96). However, in the earlier trial, participants were paid $175 if they reached their goals. In Make Better Choices 2, Dr. Spring and her coworkers wanted to see if behavioral change could be achieved without a large financial incentive.

Make Better Choices 2 participants were randomized to one of three study arms: simultaneous targeting of fruit and vegetable intake, sedentary screen time, and low moderate to vigorous physical activity; sequential targeting of fruit/vegetables and screen time followed by the physical activity intervention; or a control group that received instruction on reducing stress and improving sleep.

The simultaneous and sequential interventions proved equally effective. And as in Make Better Choices 1, a carryover effect was seen: At 9 months, not only was fruit and vegetable consumption increased by 5.9 servings per day, compared with baseline and leisure screen time reduced by 2 hours and 7 minutes per day, but participants reduced their saturated fat intake by an absolute 3.7% of total calories consumed daily, even though saturated fat wasn’t targeted.

“We think the improvement in saturated fat intake was due mostly to cutting down on hand to mouth snacking behavior by decreasing TV time,” she explained.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity time was increased by an average of 16 minutes per day in the two active treatment arms, compared with controls at 6 months. However, at 9 months, there was no significant difference among the three groups.

“The hardest behavior change for us to initiate and maintain is moderate to vigorous physical activity. I think that warrants more research,” according to Dr. Spring.

Adherence was good, with roughly an 18% dropout rate through 9 months in each study arm.

Session moderator Dr. Sidney C. Smith of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, noted that only about 25% of participants in the trial were men. He’s observed a similarly skewed ratio in other behavioral studies, and he wondered why, given that men have their acute MIs an average of 10 years earlier than women.

“This is a classic challenge in behavior intervention trials. It’s very difficult to get men to enroll,” Dr. Spring replied. “There’s starting to be a body of work trying to address this challenge.”

She added that she believes for some men it’s an issue of control. They want to do things their way, and they confuse support with control.

“This is one of the hopes of having technology available: If you’re a do-it-yourselfer, here are tools to help you do it yourself,” Dr. Spring said.

Once men get on board, however, a consistent finding in behavioral intervention studies is that the strategies work as well in men as in women, she observed.

Make Better Choices 2 was funded by Northwestern University and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Spring reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – A 12-week intervention involving a smartphone app and weekly coaching by telephone resulted in sustained, clinically meaningful improvement in multiple unhealthy diet and activity behaviors in the randomized, controlled Make Better Choices 2 study.

“It’s far more possible than I would have believed to produce sustained, large-magnitude changes in cardiovascular risk behaviors without using large financial incentives through the use of technologic support and a scalable approach to coaching,” principal investigator Bonnie J. Spring, Ph.D., said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is an example of what preventive medicine experts term “primordial prevention.” It’s intervention further upstream than primary prevention, which addresses the standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors before a cardiovascular event has occurred. Primordial prevention addresses the unhealthy behaviors that eventually lead to the standard risk factors.

Make Better Choices 2 included 212 adults, all of whom had four unhealthy behaviors of interest: low fruit and vegetable intake, high consumption of saturated fat, low levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, and excessive sedentary leisure TV and computer screen time.

The smartphone app was used for self-monitoring on the journey toward goal attainment. The data were uploaded regularly to the remote coach, who provided individualized instruction weekly for 3 months, then every 2 weeks during the next 3 months, and monthly for the final 3 months, explained Dr. Spring, professor of preventive medicine and director of the Center for Behavior and Health at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study expanded upon the success of the earlier 204-subject Make Better Choices 1 study, which showed that targeting two of the four unhealthy behaviors resulted in efficiently synergistic improvement in all four (Arch Intern Med. 2012 May 28;172[10]:789-96). However, in the earlier trial, participants were paid $175 if they reached their goals. In Make Better Choices 2, Dr. Spring and her coworkers wanted to see if behavioral change could be achieved without a large financial incentive.

Make Better Choices 2 participants were randomized to one of three study arms: simultaneous targeting of fruit and vegetable intake, sedentary screen time, and low moderate to vigorous physical activity; sequential targeting of fruit/vegetables and screen time followed by the physical activity intervention; or a control group that received instruction on reducing stress and improving sleep.

The simultaneous and sequential interventions proved equally effective. And as in Make Better Choices 1, a carryover effect was seen: At 9 months, not only was fruit and vegetable consumption increased by 5.9 servings per day, compared with baseline and leisure screen time reduced by 2 hours and 7 minutes per day, but participants reduced their saturated fat intake by an absolute 3.7% of total calories consumed daily, even though saturated fat wasn’t targeted.

“We think the improvement in saturated fat intake was due mostly to cutting down on hand to mouth snacking behavior by decreasing TV time,” she explained.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity time was increased by an average of 16 minutes per day in the two active treatment arms, compared with controls at 6 months. However, at 9 months, there was no significant difference among the three groups.

“The hardest behavior change for us to initiate and maintain is moderate to vigorous physical activity. I think that warrants more research,” according to Dr. Spring.

Adherence was good, with roughly an 18% dropout rate through 9 months in each study arm.

Session moderator Dr. Sidney C. Smith of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, noted that only about 25% of participants in the trial were men. He’s observed a similarly skewed ratio in other behavioral studies, and he wondered why, given that men have their acute MIs an average of 10 years earlier than women.

“This is a classic challenge in behavior intervention trials. It’s very difficult to get men to enroll,” Dr. Spring replied. “There’s starting to be a body of work trying to address this challenge.”

She added that she believes for some men it’s an issue of control. They want to do things their way, and they confuse support with control.

“This is one of the hopes of having technology available: If you’re a do-it-yourselfer, here are tools to help you do it yourself,” Dr. Spring said.

Once men get on board, however, a consistent finding in behavioral intervention studies is that the strategies work as well in men as in women, she observed.

Make Better Choices 2 was funded by Northwestern University and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Spring reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Remote coaching supported by a smartphone app can simultaneously improve multiple unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.

Major finding: A 12-week intervention incorporating smartphone technology and weekly coaching by telephone produced sustained improvements in multiple unhealthy diet and physical activity behaviors without resorting to financial incentives.

Data source: Make Better Choices 2 was a multicenter trial in which 212 adults with four specific unhealthy behaviors were randomized to a mobile behavioral health intervention or a control group.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Northwestern University and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Spring reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

67% of teens have substantial cardiometabolic risk burden, blood donor survey shows

ORLANDO – Fully two-thirds of nearly 25,000 Dallas-area volunteer blood donors ages 16-19 had elevated or borderline total cholesterol, blood pressure, and/or hemoglobin A1c, Dr. Merlyn H. Sayers reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“It is startling that such a significant percentage of these young, ostensibly healthy volunteers have abnormal cardiometabolic health metrics,” observed Dr. Sayers, president and chief executive officer of Carter BloodCare of Bedford, Tex., a nonprofit organization that is the largest blood bank in the state.

After all, he noted, longitudinal studies have clearly shown that cardiometabolic risk factors present in adolescence will persist into adulthood and are associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Moreover, it’s troubling, albeit not really surprising, that for the most part these adolescents don’t seem to care about their cardiometabolic risk, the hematologist-oncologist added.

“We give all these youngsters an opportunity to go to the Carter BloodCare website and confidentially retrieve their values. But despite all manner of urging on our part that these results are important, at best only about 20% of the individuals actually do so, and that rate varies substantially by race and ethnicity,” according to Dr. Sayers. “Where appropriate, we need to find ways to impose behavior modification on a group that is relatively resistant to guidance and intervention. Even the best kids, as teenagers, really don’t take this sort of advice about their health risk very seriously. They regard themselves as immortal during their teenage years.”

Noting that behavioral change is not a core strength among transfusion medicine specialists, Dr. Sayers appealed to his audience of cardiologists for suggestions as to how to encourage lifestyle modification in this youthful group without browbeating them to the point that they’re driven off from becoming serial blood donors.

It’s not widely appreciated that across the U.S. during the school year, 20% of all unpaid blood donors are high school students. These high school blood drives provide an as-yet untapped opportunity to screen adolescents for cardiometabolic risk at low cost and minimal inconvenience to participants, said Dr. Sayers of the University of Texas, Dallas.

“We need allies to help us to ensure we get the kids’ attention better,” he explained. “I want to leave you with the sense that perhaps you will see these blood drives as an opportunity to find interventions that might address primordial prevention of cardiometabolic risk.”

He presented a study of 24,925 youths aged 16-19 who donated blood to Carter BloodCare during 2011-2012. Since blood is drawn for obligatory infectious diseases screening at each donation, Dr. Sayers and coinvestigators were able to measure nonfasting total cholesterol and HbA1c in every teen donor. Blood pressure is also measured at every donation.

The investigators used widely accepted definitions of elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, and HbA1c: namely, at least 140/80 mm Hg, 200 mg/dL, and 6.5%, respectively.

While the percentage of teen blood donors with borderline or elevated levels of all three cardiometabolic risk factors was in the low single figures, 21% of boys and 15% of girls were positive for two out of the three.

The prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors varied by ethnicity. Sixteen percent of white adolescents had elevated or borderline levels of two risk factors. So did 24% of African Americans, 22% of Asian Americans, and 18% of Hispanics.

“These are really staggering results,” commented session chair Dr. Seth S. Martin of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is a call to action now that you’ve identified all these kids who are on a trajectory that doesn’t look good.”

As to how physicians can help to favorably alter that trajectory, however, audience members admitted to being stumped, especially since many young people stop going to a primary care physician for preventive care during their teenage years.

“The big problem here is how to use this information to initiate lifestyle change,” observed Dr. Lewis H. Kuller, professor and past chair of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sayers reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

ORLANDO – Fully two-thirds of nearly 25,000 Dallas-area volunteer blood donors ages 16-19 had elevated or borderline total cholesterol, blood pressure, and/or hemoglobin A1c, Dr. Merlyn H. Sayers reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“It is startling that such a significant percentage of these young, ostensibly healthy volunteers have abnormal cardiometabolic health metrics,” observed Dr. Sayers, president and chief executive officer of Carter BloodCare of Bedford, Tex., a nonprofit organization that is the largest blood bank in the state.

After all, he noted, longitudinal studies have clearly shown that cardiometabolic risk factors present in adolescence will persist into adulthood and are associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Moreover, it’s troubling, albeit not really surprising, that for the most part these adolescents don’t seem to care about their cardiometabolic risk, the hematologist-oncologist added.

“We give all these youngsters an opportunity to go to the Carter BloodCare website and confidentially retrieve their values. But despite all manner of urging on our part that these results are important, at best only about 20% of the individuals actually do so, and that rate varies substantially by race and ethnicity,” according to Dr. Sayers. “Where appropriate, we need to find ways to impose behavior modification on a group that is relatively resistant to guidance and intervention. Even the best kids, as teenagers, really don’t take this sort of advice about their health risk very seriously. They regard themselves as immortal during their teenage years.”

Noting that behavioral change is not a core strength among transfusion medicine specialists, Dr. Sayers appealed to his audience of cardiologists for suggestions as to how to encourage lifestyle modification in this youthful group without browbeating them to the point that they’re driven off from becoming serial blood donors.

It’s not widely appreciated that across the U.S. during the school year, 20% of all unpaid blood donors are high school students. These high school blood drives provide an as-yet untapped opportunity to screen adolescents for cardiometabolic risk at low cost and minimal inconvenience to participants, said Dr. Sayers of the University of Texas, Dallas.

“We need allies to help us to ensure we get the kids’ attention better,” he explained. “I want to leave you with the sense that perhaps you will see these blood drives as an opportunity to find interventions that might address primordial prevention of cardiometabolic risk.”

He presented a study of 24,925 youths aged 16-19 who donated blood to Carter BloodCare during 2011-2012. Since blood is drawn for obligatory infectious diseases screening at each donation, Dr. Sayers and coinvestigators were able to measure nonfasting total cholesterol and HbA1c in every teen donor. Blood pressure is also measured at every donation.

The investigators used widely accepted definitions of elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, and HbA1c: namely, at least 140/80 mm Hg, 200 mg/dL, and 6.5%, respectively.

While the percentage of teen blood donors with borderline or elevated levels of all three cardiometabolic risk factors was in the low single figures, 21% of boys and 15% of girls were positive for two out of the three.

The prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors varied by ethnicity. Sixteen percent of white adolescents had elevated or borderline levels of two risk factors. So did 24% of African Americans, 22% of Asian Americans, and 18% of Hispanics.

“These are really staggering results,” commented session chair Dr. Seth S. Martin of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is a call to action now that you’ve identified all these kids who are on a trajectory that doesn’t look good.”

As to how physicians can help to favorably alter that trajectory, however, audience members admitted to being stumped, especially since many young people stop going to a primary care physician for preventive care during their teenage years.

“The big problem here is how to use this information to initiate lifestyle change,” observed Dr. Lewis H. Kuller, professor and past chair of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sayers reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

ORLANDO – Fully two-thirds of nearly 25,000 Dallas-area volunteer blood donors ages 16-19 had elevated or borderline total cholesterol, blood pressure, and/or hemoglobin A1c, Dr. Merlyn H. Sayers reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“It is startling that such a significant percentage of these young, ostensibly healthy volunteers have abnormal cardiometabolic health metrics,” observed Dr. Sayers, president and chief executive officer of Carter BloodCare of Bedford, Tex., a nonprofit organization that is the largest blood bank in the state.

After all, he noted, longitudinal studies have clearly shown that cardiometabolic risk factors present in adolescence will persist into adulthood and are associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Moreover, it’s troubling, albeit not really surprising, that for the most part these adolescents don’t seem to care about their cardiometabolic risk, the hematologist-oncologist added.

“We give all these youngsters an opportunity to go to the Carter BloodCare website and confidentially retrieve their values. But despite all manner of urging on our part that these results are important, at best only about 20% of the individuals actually do so, and that rate varies substantially by race and ethnicity,” according to Dr. Sayers. “Where appropriate, we need to find ways to impose behavior modification on a group that is relatively resistant to guidance and intervention. Even the best kids, as teenagers, really don’t take this sort of advice about their health risk very seriously. They regard themselves as immortal during their teenage years.”

Noting that behavioral change is not a core strength among transfusion medicine specialists, Dr. Sayers appealed to his audience of cardiologists for suggestions as to how to encourage lifestyle modification in this youthful group without browbeating them to the point that they’re driven off from becoming serial blood donors.

It’s not widely appreciated that across the U.S. during the school year, 20% of all unpaid blood donors are high school students. These high school blood drives provide an as-yet untapped opportunity to screen adolescents for cardiometabolic risk at low cost and minimal inconvenience to participants, said Dr. Sayers of the University of Texas, Dallas.

“We need allies to help us to ensure we get the kids’ attention better,” he explained. “I want to leave you with the sense that perhaps you will see these blood drives as an opportunity to find interventions that might address primordial prevention of cardiometabolic risk.”

He presented a study of 24,925 youths aged 16-19 who donated blood to Carter BloodCare during 2011-2012. Since blood is drawn for obligatory infectious diseases screening at each donation, Dr. Sayers and coinvestigators were able to measure nonfasting total cholesterol and HbA1c in every teen donor. Blood pressure is also measured at every donation.

The investigators used widely accepted definitions of elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, and HbA1c: namely, at least 140/80 mm Hg, 200 mg/dL, and 6.5%, respectively.

While the percentage of teen blood donors with borderline or elevated levels of all three cardiometabolic risk factors was in the low single figures, 21% of boys and 15% of girls were positive for two out of the three.

The prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors varied by ethnicity. Sixteen percent of white adolescents had elevated or borderline levels of two risk factors. So did 24% of African Americans, 22% of Asian Americans, and 18% of Hispanics.

“These are really staggering results,” commented session chair Dr. Seth S. Martin of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is a call to action now that you’ve identified all these kids who are on a trajectory that doesn’t look good.”

As to how physicians can help to favorably alter that trajectory, however, audience members admitted to being stumped, especially since many young people stop going to a primary care physician for preventive care during their teenage years.

“The big problem here is how to use this information to initiate lifestyle change,” observed Dr. Lewis H. Kuller, professor and past chair of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sayers reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Two-thirds of 16- to 19-year-olds have borderline or frank hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and/or high blood glucose.

Major finding: Of a very large group of 16- to 19-year-old blood donors, 67% had borderline or elevated total cholesterol, blood pressure, and/or hemoglobin A1c levels.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of total cholesterol, blood pressure, and HbA1c levels in 24,925 Dallas-area blood donors aged 16-19.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

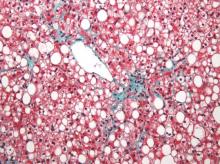

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will keep rising ‘in near term’

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) almost tripled among United States veterans in a recent 9-year period, investigators reported in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The trend “was evident in all racial groups, across all age groups, and in both genders,” said Dr. Fasiha Kanwal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, and her associates. The increasing prevalence of NAFLD “is likely generalizable to nonveterans,” and will probably persist because of a “fairly steady” 2%-3% overall annual incidence and a steeper rise among younger individuals, they added. “Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will continue to remain a major public health problem in the United States, at least in the near and intermediate future.”

Although NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver failure in the United States, few studies have examined its incidence or prevalence over time, which are key to predicting future disease burden. Therefore, the investigators analyzed data for more than 9.78 million patients who visited the VA at least once between 2003 and 2011. They defined NAFLD as at least two elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values (greater than 40 IU/mL) separated by at least 6 months, with no history of positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen or hepatitis C virus RNA, and no alcohol-related ICD-9 codes or positive AUDIT-C scores within a year of elevated ALT levels (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Aug 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.010).

During the study period, more than 1.3 million patients, or 13.6%, met the definition of NAFLD, said the researchers. Age-adjusted incidence rates dropped slightly from 3.16% in 2003 to 2.5% in 2011, ranging between 2.3% and 2.7% in most years. Prevalence, however, rose from 6.3% in 2003 (95% confidence interval, 6.26%-6.3%) to 17.6% in 2011 (95% CI, 17.58%-17.65%), a 2.8-fold increase. Moreover, about one in five patients with NAFLD who visited the VA in 2011 was at risk for advanced fibrosis.

Among individuals who were younger than 45 years, the incidence of NAFLD rose from 2.3 to 4.3 cases per 100 persons (annual percentage change, 7.4%; 95% CI, 5.7% to 9.2%), the researchers also found. “Although recent studies show that the rate of increase in both obesity and diabetes, which are both major risk factors for NAFLD, may be slowing down in the U.S., this may not be the case in the VA, where the prevalence of obesity and diabetes is in fact higher than in the U.S. population,” they said.

In general, the findings mirror a recent analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jan;41[1]:65-76), according to the investigators. “The VA is the largest integrated health care system in the United States,” they added. “We believe that the sheer size of the veteran cohort, combined with a complete dearth of information regarding the burden of NAFLD in the VA, renders our findings highly significant. Furthermore, the VA is in a unique position to test and implement systemic changes in medical care delivery to improve the health care of NAFLD patients.”

The study was partially supported by the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The researchers had no disclosures.

Kanwal and colleagues present an interesting study assessing the trends in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD in the United States. Findings suggest that the annual incidence of NAFLD has generally been stable (2.2%-3.2%), while the prevalence of NAFLD has increased by 2.8-fold (6.3%-17.6%). These findings are consistent with the literature and provide additional evidence supporting the increasing burden of NAFLD. Although an important study, there are some limitations to the study design. First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was solely based on elevated liver enzymes, which can underestimate the true incidence and prevalence of NAFLD. In fact, in a recent meta-analysis, NAFLD prevalence based on liver enzymes was 13%, while NAFLD prevalence based on radiologic diagnosis was 25% (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Second, the study subjects came from the VA system, which may not be representative of the U.S. population (Patrick AFB, FL: Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute, 2010). This is important because sex-specific differences in the prevalence of NAFLD have been reported (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Nevertheless, these limitations do not minimize the important contribution of this study. There appears to be an alarming increase in the burden of NAFLD within all the racial and age groups in the U.S. Further, this increase in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD is especially significant among the younger age groups (less than 45 years). This finding is in contrast to others who have reported a higher prevalence in older subjects (Presented at AASLD 2015. San Francisco. Abstract #534). If confirmed, this younger cohort of patients with NAFLD can fuel the future burden of liver disease for the next few decades (JAMA. 2012;307:491-7). Given the current lack of an effective treatment for NAFLD, a national strategy to deal with this important and rising cause of chronic liver disease is urgently needed.

Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, MPH, FACG, AGAF, FAASLD, is chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Hospital; vice president for research, Inova Health System; professor of medicine, VCU-Inova Campus and Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Falls Church, Va. He has consulted for Gilead, AbbVie, Intercept, BMS, and GSK.

Kanwal and colleagues present an interesting study assessing the trends in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD in the United States. Findings suggest that the annual incidence of NAFLD has generally been stable (2.2%-3.2%), while the prevalence of NAFLD has increased by 2.8-fold (6.3%-17.6%). These findings are consistent with the literature and provide additional evidence supporting the increasing burden of NAFLD. Although an important study, there are some limitations to the study design. First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was solely based on elevated liver enzymes, which can underestimate the true incidence and prevalence of NAFLD. In fact, in a recent meta-analysis, NAFLD prevalence based on liver enzymes was 13%, while NAFLD prevalence based on radiologic diagnosis was 25% (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Second, the study subjects came from the VA system, which may not be representative of the U.S. population (Patrick AFB, FL: Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute, 2010). This is important because sex-specific differences in the prevalence of NAFLD have been reported (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Nevertheless, these limitations do not minimize the important contribution of this study. There appears to be an alarming increase in the burden of NAFLD within all the racial and age groups in the U.S. Further, this increase in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD is especially significant among the younger age groups (less than 45 years). This finding is in contrast to others who have reported a higher prevalence in older subjects (Presented at AASLD 2015. San Francisco. Abstract #534). If confirmed, this younger cohort of patients with NAFLD can fuel the future burden of liver disease for the next few decades (JAMA. 2012;307:491-7). Given the current lack of an effective treatment for NAFLD, a national strategy to deal with this important and rising cause of chronic liver disease is urgently needed.

Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, MPH, FACG, AGAF, FAASLD, is chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Hospital; vice president for research, Inova Health System; professor of medicine, VCU-Inova Campus and Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Falls Church, Va. He has consulted for Gilead, AbbVie, Intercept, BMS, and GSK.

Kanwal and colleagues present an interesting study assessing the trends in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD in the United States. Findings suggest that the annual incidence of NAFLD has generally been stable (2.2%-3.2%), while the prevalence of NAFLD has increased by 2.8-fold (6.3%-17.6%). These findings are consistent with the literature and provide additional evidence supporting the increasing burden of NAFLD. Although an important study, there are some limitations to the study design. First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was solely based on elevated liver enzymes, which can underestimate the true incidence and prevalence of NAFLD. In fact, in a recent meta-analysis, NAFLD prevalence based on liver enzymes was 13%, while NAFLD prevalence based on radiologic diagnosis was 25% (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Second, the study subjects came from the VA system, which may not be representative of the U.S. population (Patrick AFB, FL: Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute, 2010). This is important because sex-specific differences in the prevalence of NAFLD have been reported (Hepatology. 2015 Dec 28. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [Epub ahead of print]). Nevertheless, these limitations do not minimize the important contribution of this study. There appears to be an alarming increase in the burden of NAFLD within all the racial and age groups in the U.S. Further, this increase in the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD is especially significant among the younger age groups (less than 45 years). This finding is in contrast to others who have reported a higher prevalence in older subjects (Presented at AASLD 2015. San Francisco. Abstract #534). If confirmed, this younger cohort of patients with NAFLD can fuel the future burden of liver disease for the next few decades (JAMA. 2012;307:491-7). Given the current lack of an effective treatment for NAFLD, a national strategy to deal with this important and rising cause of chronic liver disease is urgently needed.

Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, MPH, FACG, AGAF, FAASLD, is chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Hospital; vice president for research, Inova Health System; professor of medicine, VCU-Inova Campus and Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Falls Church, Va. He has consulted for Gilead, AbbVie, Intercept, BMS, and GSK.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) almost tripled among United States veterans in a recent 9-year period, investigators reported in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The trend “was evident in all racial groups, across all age groups, and in both genders,” said Dr. Fasiha Kanwal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, and her associates. The increasing prevalence of NAFLD “is likely generalizable to nonveterans,” and will probably persist because of a “fairly steady” 2%-3% overall annual incidence and a steeper rise among younger individuals, they added. “Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will continue to remain a major public health problem in the United States, at least in the near and intermediate future.”

Although NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver failure in the United States, few studies have examined its incidence or prevalence over time, which are key to predicting future disease burden. Therefore, the investigators analyzed data for more than 9.78 million patients who visited the VA at least once between 2003 and 2011. They defined NAFLD as at least two elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values (greater than 40 IU/mL) separated by at least 6 months, with no history of positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen or hepatitis C virus RNA, and no alcohol-related ICD-9 codes or positive AUDIT-C scores within a year of elevated ALT levels (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Aug 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.010).

During the study period, more than 1.3 million patients, or 13.6%, met the definition of NAFLD, said the researchers. Age-adjusted incidence rates dropped slightly from 3.16% in 2003 to 2.5% in 2011, ranging between 2.3% and 2.7% in most years. Prevalence, however, rose from 6.3% in 2003 (95% confidence interval, 6.26%-6.3%) to 17.6% in 2011 (95% CI, 17.58%-17.65%), a 2.8-fold increase. Moreover, about one in five patients with NAFLD who visited the VA in 2011 was at risk for advanced fibrosis.

Among individuals who were younger than 45 years, the incidence of NAFLD rose from 2.3 to 4.3 cases per 100 persons (annual percentage change, 7.4%; 95% CI, 5.7% to 9.2%), the researchers also found. “Although recent studies show that the rate of increase in both obesity and diabetes, which are both major risk factors for NAFLD, may be slowing down in the U.S., this may not be the case in the VA, where the prevalence of obesity and diabetes is in fact higher than in the U.S. population,” they said.

In general, the findings mirror a recent analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jan;41[1]:65-76), according to the investigators. “The VA is the largest integrated health care system in the United States,” they added. “We believe that the sheer size of the veteran cohort, combined with a complete dearth of information regarding the burden of NAFLD in the VA, renders our findings highly significant. Furthermore, the VA is in a unique position to test and implement systemic changes in medical care delivery to improve the health care of NAFLD patients.”

The study was partially supported by the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The researchers had no disclosures.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) almost tripled among United States veterans in a recent 9-year period, investigators reported in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The trend “was evident in all racial groups, across all age groups, and in both genders,” said Dr. Fasiha Kanwal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, and her associates. The increasing prevalence of NAFLD “is likely generalizable to nonveterans,” and will probably persist because of a “fairly steady” 2%-3% overall annual incidence and a steeper rise among younger individuals, they added. “Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will continue to remain a major public health problem in the United States, at least in the near and intermediate future.”

Although NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver failure in the United States, few studies have examined its incidence or prevalence over time, which are key to predicting future disease burden. Therefore, the investigators analyzed data for more than 9.78 million patients who visited the VA at least once between 2003 and 2011. They defined NAFLD as at least two elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values (greater than 40 IU/mL) separated by at least 6 months, with no history of positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen or hepatitis C virus RNA, and no alcohol-related ICD-9 codes or positive AUDIT-C scores within a year of elevated ALT levels (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Aug 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.010).

During the study period, more than 1.3 million patients, or 13.6%, met the definition of NAFLD, said the researchers. Age-adjusted incidence rates dropped slightly from 3.16% in 2003 to 2.5% in 2011, ranging between 2.3% and 2.7% in most years. Prevalence, however, rose from 6.3% in 2003 (95% confidence interval, 6.26%-6.3%) to 17.6% in 2011 (95% CI, 17.58%-17.65%), a 2.8-fold increase. Moreover, about one in five patients with NAFLD who visited the VA in 2011 was at risk for advanced fibrosis.

Among individuals who were younger than 45 years, the incidence of NAFLD rose from 2.3 to 4.3 cases per 100 persons (annual percentage change, 7.4%; 95% CI, 5.7% to 9.2%), the researchers also found. “Although recent studies show that the rate of increase in both obesity and diabetes, which are both major risk factors for NAFLD, may be slowing down in the U.S., this may not be the case in the VA, where the prevalence of obesity and diabetes is in fact higher than in the U.S. population,” they said.

In general, the findings mirror a recent analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jan;41[1]:65-76), according to the investigators. “The VA is the largest integrated health care system in the United States,” they added. “We believe that the sheer size of the veteran cohort, combined with a complete dearth of information regarding the burden of NAFLD in the VA, renders our findings highly significant. Furthermore, the VA is in a unique position to test and implement systemic changes in medical care delivery to improve the health care of NAFLD patients.”

The study was partially supported by the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has risen substantially since 2003, and will probably keep increasing in the near term.

Major finding: Prevalence among veterans rose about 2.8 times between 2003 and 2011, mirroring trends reported in the general population.

Data source: An analysis of data from 9.78 million Veterans Affairs patients.

Disclosures: The study was partially supported by the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The researchers had no disclosures.

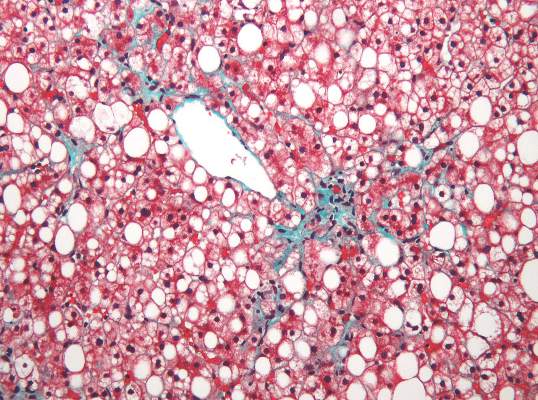

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease linked to liver cancer without cirrhosis

About 13% of U.S. veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma had no evidence of preexisting cirrhosis, according to a report published in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The main risk factors for this entity were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD] or metabolic syndrome” – not hepatitis C virus infection [HCV], HBV [hepatitis B virus] infection, or alcohol abuse, said Dr. Sahil Mittal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Screening all patients with NAFLD for hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC] is impractical, so studies should seek “actionable risk factors” or biomarkers that reliably identify NAFLD patients who are at particular risk of HCC, wrote Dr. Mittal and his coinvestigators.

Researchers have debated whether chronic HCV infection or alcohol abuse can lead to HCC in the absence of cirrhosis, while at least one study has shown that NAFLD can predispose patients to this disease entity (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1761-6).

But few studies have systematically examined risk factors for HCC without cirrhosis in the general population, the investigators said. Therefore, they randomly selected 1,500 patients from the U.S. Veterans Affairs system who were diagnosed with HCC between 2005 and 2010 on the basis of histopathology or established imaging criteria (Hepatology 2005;42:1208-36).

They reviewed complete medical records for these patients, and classified those who did not have cirrhosis according to the quality of supporting histology, laboratory, and imaging data (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. doi: 0.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.019).

In all, 3% of the cohort had level 1 (“highest-quality”) evidence for not having cirrhosis, while another 10% had level 2 evidence for no cirrhosis, the investigators said. “Compared with HCC in the presence of cirrhosis, these patients were more likely to have metabolic syndrome or NAFLD or no identifiable risk factor, and less likely to have alcohol abuse or HCV infection,” they added. Only two-thirds of NAFLD patients with HCC had cirrhosis, compared with 91% of patients with chronic HCV infection, 92% of HCV-infected patients, and 88% of patients with an alcohol use disorder. Notably, the odds of HCC in the absence of cirrhosis were more than five times higher when patients had NAFLD (odds ratio [OR], 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.4-8.5) or metabolic syndrome (OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 3.1-7.8) compared with HCV infection.

Patients with cirrhosis often go unscreened for HCC even though they are at greatest risk of this cancer. Therefore, trying to screen all patients with NAFLD for HCC would be “logistically impractical,” particularly when the absolute risk of HCC in noncirrhotic patients is unknown and no one has examined the best ways to screen this population, the investigators said. Instead, clinicians could prioritize screening and treating NAFLD patients for diabetes mellitus and obesity, both of which are associated with HCC. “There is evidence to suggest that metformin reduces the risk of HCC among diabetics,” they added. “Studies of these and other risk factors of HCC among NAFLD patients with and without cirrhosis are needed.”

Most patients in the study were male, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings, the researchers noted.

The National Cancer Institute, the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence, the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Dan Duncan Cancer Center funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

About 13% of U.S. veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma had no evidence of preexisting cirrhosis, according to a report published in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The main risk factors for this entity were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD] or metabolic syndrome” – not hepatitis C virus infection [HCV], HBV [hepatitis B virus] infection, or alcohol abuse, said Dr. Sahil Mittal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Screening all patients with NAFLD for hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC] is impractical, so studies should seek “actionable risk factors” or biomarkers that reliably identify NAFLD patients who are at particular risk of HCC, wrote Dr. Mittal and his coinvestigators.

Researchers have debated whether chronic HCV infection or alcohol abuse can lead to HCC in the absence of cirrhosis, while at least one study has shown that NAFLD can predispose patients to this disease entity (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1761-6).

But few studies have systematically examined risk factors for HCC without cirrhosis in the general population, the investigators said. Therefore, they randomly selected 1,500 patients from the U.S. Veterans Affairs system who were diagnosed with HCC between 2005 and 2010 on the basis of histopathology or established imaging criteria (Hepatology 2005;42:1208-36).

They reviewed complete medical records for these patients, and classified those who did not have cirrhosis according to the quality of supporting histology, laboratory, and imaging data (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. doi: 0.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.019).

In all, 3% of the cohort had level 1 (“highest-quality”) evidence for not having cirrhosis, while another 10% had level 2 evidence for no cirrhosis, the investigators said. “Compared with HCC in the presence of cirrhosis, these patients were more likely to have metabolic syndrome or NAFLD or no identifiable risk factor, and less likely to have alcohol abuse or HCV infection,” they added. Only two-thirds of NAFLD patients with HCC had cirrhosis, compared with 91% of patients with chronic HCV infection, 92% of HCV-infected patients, and 88% of patients with an alcohol use disorder. Notably, the odds of HCC in the absence of cirrhosis were more than five times higher when patients had NAFLD (odds ratio [OR], 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.4-8.5) or metabolic syndrome (OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 3.1-7.8) compared with HCV infection.

Patients with cirrhosis often go unscreened for HCC even though they are at greatest risk of this cancer. Therefore, trying to screen all patients with NAFLD for HCC would be “logistically impractical,” particularly when the absolute risk of HCC in noncirrhotic patients is unknown and no one has examined the best ways to screen this population, the investigators said. Instead, clinicians could prioritize screening and treating NAFLD patients for diabetes mellitus and obesity, both of which are associated with HCC. “There is evidence to suggest that metformin reduces the risk of HCC among diabetics,” they added. “Studies of these and other risk factors of HCC among NAFLD patients with and without cirrhosis are needed.”

Most patients in the study were male, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings, the researchers noted.

The National Cancer Institute, the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence, the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Dan Duncan Cancer Center funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

About 13% of U.S. veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma had no evidence of preexisting cirrhosis, according to a report published in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“The main risk factors for this entity were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD] or metabolic syndrome” – not hepatitis C virus infection [HCV], HBV [hepatitis B virus] infection, or alcohol abuse, said Dr. Sahil Mittal of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Screening all patients with NAFLD for hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC] is impractical, so studies should seek “actionable risk factors” or biomarkers that reliably identify NAFLD patients who are at particular risk of HCC, wrote Dr. Mittal and his coinvestigators.

Researchers have debated whether chronic HCV infection or alcohol abuse can lead to HCC in the absence of cirrhosis, while at least one study has shown that NAFLD can predispose patients to this disease entity (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1761-6).

But few studies have systematically examined risk factors for HCC without cirrhosis in the general population, the investigators said. Therefore, they randomly selected 1,500 patients from the U.S. Veterans Affairs system who were diagnosed with HCC between 2005 and 2010 on the basis of histopathology or established imaging criteria (Hepatology 2005;42:1208-36).

They reviewed complete medical records for these patients, and classified those who did not have cirrhosis according to the quality of supporting histology, laboratory, and imaging data (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. doi: 0.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.019).

In all, 3% of the cohort had level 1 (“highest-quality”) evidence for not having cirrhosis, while another 10% had level 2 evidence for no cirrhosis, the investigators said. “Compared with HCC in the presence of cirrhosis, these patients were more likely to have metabolic syndrome or NAFLD or no identifiable risk factor, and less likely to have alcohol abuse or HCV infection,” they added. Only two-thirds of NAFLD patients with HCC had cirrhosis, compared with 91% of patients with chronic HCV infection, 92% of HCV-infected patients, and 88% of patients with an alcohol use disorder. Notably, the odds of HCC in the absence of cirrhosis were more than five times higher when patients had NAFLD (odds ratio [OR], 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.4-8.5) or metabolic syndrome (OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 3.1-7.8) compared with HCV infection.

Patients with cirrhosis often go unscreened for HCC even though they are at greatest risk of this cancer. Therefore, trying to screen all patients with NAFLD for HCC would be “logistically impractical,” particularly when the absolute risk of HCC in noncirrhotic patients is unknown and no one has examined the best ways to screen this population, the investigators said. Instead, clinicians could prioritize screening and treating NAFLD patients for diabetes mellitus and obesity, both of which are associated with HCC. “There is evidence to suggest that metformin reduces the risk of HCC among diabetics,” they added. “Studies of these and other risk factors of HCC among NAFLD patients with and without cirrhosis are needed.”

Most patients in the study were male, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings, the researchers noted.

The National Cancer Institute, the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence, the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Dan Duncan Cancer Center funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis.

Major finding: Patients with these diseases were more than five times as likely to develop noncirrhotic HCC compared with patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection.

Data source: A study of 1,500 randomly selected U.S. veterans diagnosed with HCC between 2005 and 2010.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute, the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence, the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Dan Duncan Cancer Center funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

New diabetes guidelines put patient front and center

The 2016 updates of the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes bring an enhanced focus on patient-centered care, evidence-based updates for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and a dedicated section on obesity (Diabetes Care 2016;39[Suppl. 1]:S4-S5. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S003).

According to Dr. Robert E. Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association in Alexandria, Va., the focus of care for individuals with diabetes is to achieve a holistic approach coordinating patient-centered disease management to maximize the benefits of an integrated team approach. The 2016 guideline puts that mission front and center.

When formulating its yearly updates, the ADA looks for new information “that makes a significant change in the practice of medicine” and that will affect patient care, Dr. Ratner said in an interview. “We are trying to make the recommendations both thorough and evidence based.”

The guidelines were formulated by a professional practice committee chaired by Dr. William H. Herman, professor of epidemiology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. According to the guidelines, the appointed committee “adheres to the Institute of Medicine Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines,” and the draft guidelines were made publicly available for comment before publication.

What’s different for 2016? Foremost is a change in approach, to more patient-centered care. Guidelines always address best practices at the population health level, Dr. Ratner said. However, “for each individual patient, interventions must be tailored, and the intervention must be adjusted to meet individual needs.”

One example is a relaxation in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) targets for the infirm and the elderly, based on data from large Veterans Affairs studies and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that show the harms of inappropriately low HbA1c levels for fragile populations. The updated guidelines encourage those caring for these patients to “back off and be more patient centered,” said Dr. Ratner.

The practice guidelines also acknowledge new information regarding the risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

These changes strive to take into account new research, while acknowledging that in some areas there’s still a paucity of data, said Dr. Ratner. For example, recommendations regarding use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for certain individuals with dyslipidemia and diabetes are included, though study of this new class of medications is ongoing; the guideline includes an evidence rating system to allow practitioners to rate the strength of recommendations when making individualized treatment decisions.

The guideline also gives the option of adding ezetimibe to a moderate statin dose for some individuals with diabetes and dyslipidemia, acknowledging the findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial. Other atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease updates include considering aspirin therapy for women 50 years and older who have diabetes with at least one additional major risk factor.

A new section devoted to obesity management acknowledges its critical importance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). While continuing to emphasize the importance of lifestyle changes, such as healthful eating and physical activity, the guideline acknowledges that there’s a role for pharmacotherapy and surgical treatment. In addition to providing information on approved anti-obesity medication, the guideline addresses the benefit of bariatric surgery for a select group of patients. “We can’t ignore the data” that point toward a role for these interventions for some patients, said Dr. Ratner. The guideline weighs the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Other updates include a recommendation for testing all adults for diabetes beginning at age 45 years, without regard to weight; clarifying testing guidelines to emphasize that no one testing strategy is preferred over another; slightly relaxing HbA1c targets for pregnant women to 6%-6.5%; and enhancing guidelines for hospitalized patients with diabetes.

The complete practice guideline, which runs to 119 pages, is accompanied by an abridged version that provides a basic framework for diabetes management. Dr. Ratner said that the complete standards of care are appropriate for endocrinologists and others who focus on diabetes management, while the abridged version is a resource for primary care providers who may see some patients with diabetes in the mix of their caseload. Both documents are available to view or download free of charge. A summary of key updates precedes the full text of the guidelines, so that those using last year’s guidelines can familiarize themselves quickly with changes in the new version.

Dr. Herman reported chairing data and safety monitoring boards for Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. He has served as the editor for the Americas of Diabetic Medicine, and as ad hoc editor in chief of Diabetes Care.

On Twitter @karioakes

The 2016 updates of the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes bring an enhanced focus on patient-centered care, evidence-based updates for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and a dedicated section on obesity (Diabetes Care 2016;39[Suppl. 1]:S4-S5. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S003).

According to Dr. Robert E. Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association in Alexandria, Va., the focus of care for individuals with diabetes is to achieve a holistic approach coordinating patient-centered disease management to maximize the benefits of an integrated team approach. The 2016 guideline puts that mission front and center.

When formulating its yearly updates, the ADA looks for new information “that makes a significant change in the practice of medicine” and that will affect patient care, Dr. Ratner said in an interview. “We are trying to make the recommendations both thorough and evidence based.”

The guidelines were formulated by a professional practice committee chaired by Dr. William H. Herman, professor of epidemiology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. According to the guidelines, the appointed committee “adheres to the Institute of Medicine Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines,” and the draft guidelines were made publicly available for comment before publication.

What’s different for 2016? Foremost is a change in approach, to more patient-centered care. Guidelines always address best practices at the population health level, Dr. Ratner said. However, “for each individual patient, interventions must be tailored, and the intervention must be adjusted to meet individual needs.”

One example is a relaxation in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) targets for the infirm and the elderly, based on data from large Veterans Affairs studies and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that show the harms of inappropriately low HbA1c levels for fragile populations. The updated guidelines encourage those caring for these patients to “back off and be more patient centered,” said Dr. Ratner.

The practice guidelines also acknowledge new information regarding the risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

These changes strive to take into account new research, while acknowledging that in some areas there’s still a paucity of data, said Dr. Ratner. For example, recommendations regarding use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for certain individuals with dyslipidemia and diabetes are included, though study of this new class of medications is ongoing; the guideline includes an evidence rating system to allow practitioners to rate the strength of recommendations when making individualized treatment decisions.

The guideline also gives the option of adding ezetimibe to a moderate statin dose for some individuals with diabetes and dyslipidemia, acknowledging the findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial. Other atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease updates include considering aspirin therapy for women 50 years and older who have diabetes with at least one additional major risk factor.

A new section devoted to obesity management acknowledges its critical importance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). While continuing to emphasize the importance of lifestyle changes, such as healthful eating and physical activity, the guideline acknowledges that there’s a role for pharmacotherapy and surgical treatment. In addition to providing information on approved anti-obesity medication, the guideline addresses the benefit of bariatric surgery for a select group of patients. “We can’t ignore the data” that point toward a role for these interventions for some patients, said Dr. Ratner. The guideline weighs the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Other updates include a recommendation for testing all adults for diabetes beginning at age 45 years, without regard to weight; clarifying testing guidelines to emphasize that no one testing strategy is preferred over another; slightly relaxing HbA1c targets for pregnant women to 6%-6.5%; and enhancing guidelines for hospitalized patients with diabetes.

The complete practice guideline, which runs to 119 pages, is accompanied by an abridged version that provides a basic framework for diabetes management. Dr. Ratner said that the complete standards of care are appropriate for endocrinologists and others who focus on diabetes management, while the abridged version is a resource for primary care providers who may see some patients with diabetes in the mix of their caseload. Both documents are available to view or download free of charge. A summary of key updates precedes the full text of the guidelines, so that those using last year’s guidelines can familiarize themselves quickly with changes in the new version.

Dr. Herman reported chairing data and safety monitoring boards for Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. He has served as the editor for the Americas of Diabetic Medicine, and as ad hoc editor in chief of Diabetes Care.

On Twitter @karioakes

The 2016 updates of the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes bring an enhanced focus on patient-centered care, evidence-based updates for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and a dedicated section on obesity (Diabetes Care 2016;39[Suppl. 1]:S4-S5. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S003).

According to Dr. Robert E. Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association in Alexandria, Va., the focus of care for individuals with diabetes is to achieve a holistic approach coordinating patient-centered disease management to maximize the benefits of an integrated team approach. The 2016 guideline puts that mission front and center.

When formulating its yearly updates, the ADA looks for new information “that makes a significant change in the practice of medicine” and that will affect patient care, Dr. Ratner said in an interview. “We are trying to make the recommendations both thorough and evidence based.”

The guidelines were formulated by a professional practice committee chaired by Dr. William H. Herman, professor of epidemiology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. According to the guidelines, the appointed committee “adheres to the Institute of Medicine Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines,” and the draft guidelines were made publicly available for comment before publication.

What’s different for 2016? Foremost is a change in approach, to more patient-centered care. Guidelines always address best practices at the population health level, Dr. Ratner said. However, “for each individual patient, interventions must be tailored, and the intervention must be adjusted to meet individual needs.”

One example is a relaxation in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) targets for the infirm and the elderly, based on data from large Veterans Affairs studies and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that show the harms of inappropriately low HbA1c levels for fragile populations. The updated guidelines encourage those caring for these patients to “back off and be more patient centered,” said Dr. Ratner.

The practice guidelines also acknowledge new information regarding the risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

These changes strive to take into account new research, while acknowledging that in some areas there’s still a paucity of data, said Dr. Ratner. For example, recommendations regarding use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for certain individuals with dyslipidemia and diabetes are included, though study of this new class of medications is ongoing; the guideline includes an evidence rating system to allow practitioners to rate the strength of recommendations when making individualized treatment decisions.

The guideline also gives the option of adding ezetimibe to a moderate statin dose for some individuals with diabetes and dyslipidemia, acknowledging the findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial. Other atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease updates include considering aspirin therapy for women 50 years and older who have diabetes with at least one additional major risk factor.

A new section devoted to obesity management acknowledges its critical importance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). While continuing to emphasize the importance of lifestyle changes, such as healthful eating and physical activity, the guideline acknowledges that there’s a role for pharmacotherapy and surgical treatment. In addition to providing information on approved anti-obesity medication, the guideline addresses the benefit of bariatric surgery for a select group of patients. “We can’t ignore the data” that point toward a role for these interventions for some patients, said Dr. Ratner. The guideline weighs the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Other updates include a recommendation for testing all adults for diabetes beginning at age 45 years, without regard to weight; clarifying testing guidelines to emphasize that no one testing strategy is preferred over another; slightly relaxing HbA1c targets for pregnant women to 6%-6.5%; and enhancing guidelines for hospitalized patients with diabetes.

The complete practice guideline, which runs to 119 pages, is accompanied by an abridged version that provides a basic framework for diabetes management. Dr. Ratner said that the complete standards of care are appropriate for endocrinologists and others who focus on diabetes management, while the abridged version is a resource for primary care providers who may see some patients with diabetes in the mix of their caseload. Both documents are available to view or download free of charge. A summary of key updates precedes the full text of the guidelines, so that those using last year’s guidelines can familiarize themselves quickly with changes in the new version.

Dr. Herman reported chairing data and safety monitoring boards for Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. He has served as the editor for the Americas of Diabetic Medicine, and as ad hoc editor in chief of Diabetes Care.

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM DIABETES CARE

WDC: Data help clarify which diabetic patients benefit from bariatric surgery

VANCOUVER – It may be time to reconsider the criteria used to select obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus for bariatric surgery, according to data from a pooled cohort study.

Typically, diabetic patients are considered eligible only if they have a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 and poorly controlled glycemia, according to lead author Dr. Geltrude Mingrone, department of internal medicine, Catholic University, Rome, and department of diabetes and nutritional sciences, King’s College, London.

But in her team’s new analysis of 727 patients, the best predictors of remission after bariatric surgery were a lower fasting glucose level, shorter diabetes duration at baseline, and having a gastric procedure with diversion, she reported at the World Diabetes Congress. And the best baseline predictors of improved glycemic control after bariatric surgery were lower waist circumference, better diabetes control, and lower triglyceride levels.

“We can say that there is a clear advantage of an early operation on diabetes remission that is independent of baseline body mass index. Baseline waist circumference and HOMA-IR [homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance] are better predictors of glycemic control after bariatric surgery than body mass index,” Dr. Mingrone maintained.

“So I would like to advise the scientific community … to try to define new criteria for the selection of diabetic patients for metabolic surgery. Also, [it is important] because all over the world, the number of bariatric operations is only 250,000, a quarter of a million, while the potential eligible patients are many, many millions,” she concluded.

“I completely concur with Professor Mingrone – we need to come up with criteria for utilizing this procedure,” session comoderator Dr. Robert E. Ratner said in an interview.

“There are so many millions of individuals with diabetes, we cannot be doing surgery on all of them. We need to be selective, and we need to be very specific about why we are doing it and what we are looking for,” elaborated Dr. Rattner, who is a professor of medicine at Georgetown University and senior research scientist at the MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, as well as chief scientific and medical officer of the American Diabetes Association, Alexandria, Va.

In the new research, the investigators merged databases of the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) prospective controlled study (N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683-93) and two randomized, controlled trials conducted in Australia (JAMA. 2008;299:316-23) and Italy (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-85).

Overall, 415 patients had bariatric surgery (about three-fourths had a gastric-only procedure, while the rest had a gastric procedure plus diversion) and 312 patients had medical management. The mean duration of diabetes at baseline was roughly 3.5 years.

After 2 years the proportion of patients achieving diabetes remission, defined as a fasting plasma glucose of less than 5.6 mmol/L in the absence of any antidiabetes medication, was higher in the surgical group than in the medical group (64% vs. 15%, P less than .001). And within the surgical group, it was higher for those whose operation included a diversion (76% vs. 60%, P = .016).

Among the patients who had surgery, the probability of remission fell with increasing baseline diabetes duration (–0.210), and fasting blood glucose level (–0.145), whereas it rose with increasing body mass index (+0.059). But when the type of surgery was added to the model, body mass index was no longer a significant predictor, and two additional predictors emerged: use of only oral antidiabetic medications versus none (–1.22) and receipt of a procedure with diversion (2.180).

In the subgroup who had a gastric-only procedure, the probability of remission fell with increasing diabetes duration (–0.197), and increasing fasting blood glucose level (–0.186), and it was lower for patients who used only oral antidiabetic medications (–1.364) or insulin with or without oral medications (–1.783). In the subgroup who had a gastric procedure with diversion, the only predictor was diabetes duration (–0.273).

Of note, there was no significant difference in the odds of remission between patients with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or lower and patients with a body index between 35 and 40 kg/m2.