User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Severity of obesity matters in pediatric population

Children and adolescents with more severe obesity show a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic abnormalities than those with less severe obesity, so differentiating among levels of obesity is important in the pediatric population, according to a report published online Oct. 1 in New England Journal of Medicine.

Current screening guidelines for pediatric patients use only a single category for obesity, which doesn’t take into account their varying levels of risk for obesity-related disorders. To assess the distribution of cardiometabolic risk factors in obese children and adolescents, researchers performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 2011-2012.

They assessed a nationally representative sample of 8,579 participants aged 3-19 years, categorizing them by age- and gender-specific body mass index percentiles: overweight (85th-94th percentile), class I obesity (95th percentile to 119% of the 95th percentile), class II obesity (120% to 139% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 35-39, whichever was lower), or class III obesity (140% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 40 or greater, whichever was lower).

A total of 47% of the study participants were overweight, 36% had class I obesity, 12% had class II obesity, and 5% had class III obesity. The prevalence of abnormal values for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic BP, diastolic BP, glycated hemoglobin, and fasting glucose all increased with increasing severity of obesity, at most ages and across both genders. The correlations were more pronounced in boys than in girls, said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of the department of pediatrics and the department of health policy and management, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her associates.

The findings indicate that distinguishing among at least three levels of obesity severity “provides a more fine-tuned approach to identifying patients with the greatest risk of potential complications and death,” allowing targeted interventions to those at greatest risk. This is especially important because resources are too limited to provide services for every child with obesity, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1502821). “As older adolescents transition to young adulthood, the recognition that teens with obesity have increased cardiometabolic risk will be important,” they added.

This study did not specify a source of funding. Dr. Skinner reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported receiving personal fees from Nestle unrelated to this work.

Children and adolescents with more severe obesity show a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic abnormalities than those with less severe obesity, so differentiating among levels of obesity is important in the pediatric population, according to a report published online Oct. 1 in New England Journal of Medicine.

Current screening guidelines for pediatric patients use only a single category for obesity, which doesn’t take into account their varying levels of risk for obesity-related disorders. To assess the distribution of cardiometabolic risk factors in obese children and adolescents, researchers performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 2011-2012.

They assessed a nationally representative sample of 8,579 participants aged 3-19 years, categorizing them by age- and gender-specific body mass index percentiles: overweight (85th-94th percentile), class I obesity (95th percentile to 119% of the 95th percentile), class II obesity (120% to 139% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 35-39, whichever was lower), or class III obesity (140% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 40 or greater, whichever was lower).

A total of 47% of the study participants were overweight, 36% had class I obesity, 12% had class II obesity, and 5% had class III obesity. The prevalence of abnormal values for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic BP, diastolic BP, glycated hemoglobin, and fasting glucose all increased with increasing severity of obesity, at most ages and across both genders. The correlations were more pronounced in boys than in girls, said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of the department of pediatrics and the department of health policy and management, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her associates.

The findings indicate that distinguishing among at least three levels of obesity severity “provides a more fine-tuned approach to identifying patients with the greatest risk of potential complications and death,” allowing targeted interventions to those at greatest risk. This is especially important because resources are too limited to provide services for every child with obesity, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1502821). “As older adolescents transition to young adulthood, the recognition that teens with obesity have increased cardiometabolic risk will be important,” they added.

This study did not specify a source of funding. Dr. Skinner reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported receiving personal fees from Nestle unrelated to this work.

Children and adolescents with more severe obesity show a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic abnormalities than those with less severe obesity, so differentiating among levels of obesity is important in the pediatric population, according to a report published online Oct. 1 in New England Journal of Medicine.

Current screening guidelines for pediatric patients use only a single category for obesity, which doesn’t take into account their varying levels of risk for obesity-related disorders. To assess the distribution of cardiometabolic risk factors in obese children and adolescents, researchers performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 2011-2012.

They assessed a nationally representative sample of 8,579 participants aged 3-19 years, categorizing them by age- and gender-specific body mass index percentiles: overweight (85th-94th percentile), class I obesity (95th percentile to 119% of the 95th percentile), class II obesity (120% to 139% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 35-39, whichever was lower), or class III obesity (140% of the 95th percentile, or BMI of 40 or greater, whichever was lower).

A total of 47% of the study participants were overweight, 36% had class I obesity, 12% had class II obesity, and 5% had class III obesity. The prevalence of abnormal values for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic BP, diastolic BP, glycated hemoglobin, and fasting glucose all increased with increasing severity of obesity, at most ages and across both genders. The correlations were more pronounced in boys than in girls, said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of the department of pediatrics and the department of health policy and management, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her associates.

The findings indicate that distinguishing among at least three levels of obesity severity “provides a more fine-tuned approach to identifying patients with the greatest risk of potential complications and death,” allowing targeted interventions to those at greatest risk. This is especially important because resources are too limited to provide services for every child with obesity, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1502821). “As older adolescents transition to young adulthood, the recognition that teens with obesity have increased cardiometabolic risk will be important,” they added.

This study did not specify a source of funding. Dr. Skinner reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported receiving personal fees from Nestle unrelated to this work.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Children and adolescents with more severe obesity show a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic abnormalities, so differentiating among levels of obesity is important in the pediatric population.

Major finding: Forty-seven percent of the study participants were overweight, 36% had class I obesity, 12% had class II obesity, and 5% had class III obesity.

Data source: A cross-sectional analysis of NHANES data concerning 8,579 overweight/obese participants aged 3-19 years.

Disclosures: This study did not specify a source of funding. Dr. Skinner reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported receiving personal fees from Nestle unrelated to this work.

EASD: Metformin-induced B12 deficiency linked to diabetic neuropathy

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point: Metformin has an overall detrimental effect on neuropathy mediated by its effect on MMA, a specific biomarker of B12 deficiency.

Major finding: Metformin use was associated with a significant (P = .001) 0.04 micromol/L increase in MMA over the course of the study when compared with placebo.

Data source: A prospective, randomized controlled trial of 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to metformin or placebo for 4.3 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Out reported that he had no disclosures. The HOME study was supported by Takeda, Lifescan, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, and Novo Nordisk.

EASD: Liraglutide lowers HbA1c when added to insulin in longstanding type 2 diabetes

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

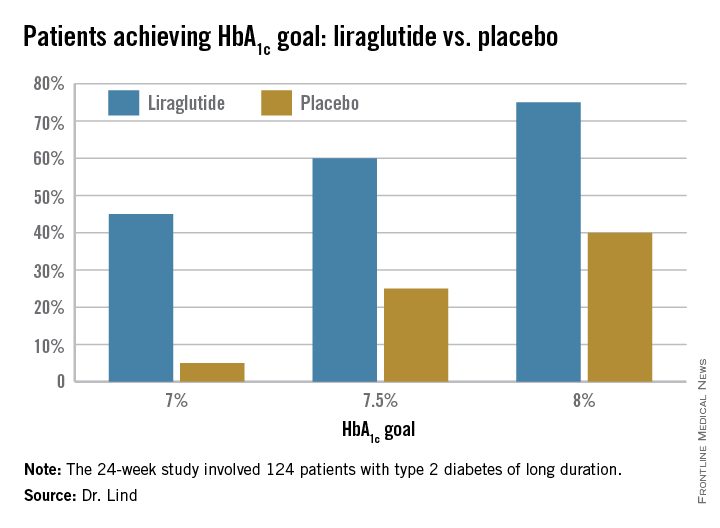

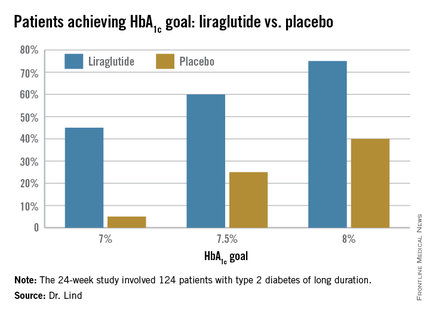

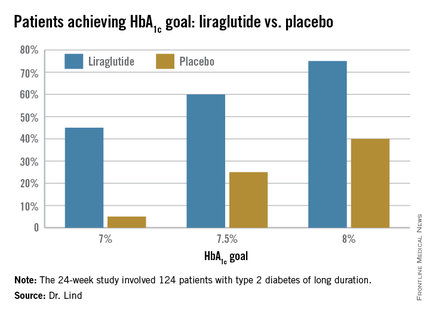

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point: Liraglutide added to multiple daily insulin injections lowered HbA1c significantly more than did placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: HbA1c at 24 weeks declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%).

Data source: A randomized, placebo-controlled study of 124 patients.

Disclosures: The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

Evidence links common endocrine-disrupting chemicals to obesity, diabetes, reproductive disorders

Cash register receipts, tin can linings, and a range of cosmetics and other common household products increasingly are implicated in the most intractable of society’s diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

So-called endocrine-disrupting chemicals have become so common, according to the Washington-based Endocrine Society, that nearly every human alive has been exposed to at least one such chemical, probably more than once, and just as likely, over an extended period of time.

The World Health Organization reports that there are more than 800 known endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) used in products globally, but only a fraction of them have been tested in humans. What effects, if any, this exposure is having on individuals is still unknown, but data linking the ability of EDCs – either singularly or in combination – to mimic, block, or otherwise interfere with the body’s natural hormone signaling has some experts sounding the alarm.

“The evidence is more definitive than ever before – EDCs disrupt hormones in a manner that harms human health,” Andrea C. Gore, Ph.D., a pharmacology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a press conference. Dr. Gore chairs the Endocrine Society task force that recently released an executive summary of its second scientific statement on EDCs. The Society presented the statement, an update of one released in 2009, at this year’s International Conference on Chemicals Management annual meeting in Geneva.

Because the endocrine system’s role is to interact with the environment, it is predisposed to react to triggers increasingly found in everything from pesticides to shower curtains, which have now made their way into waterways and the food chain primarily without any studies on their impact. “Both natural hormones and EDCs have unique dose-response properties [and can] act at very-low doses,” Dr. Gore told reporters. “We’re exposed throughout our lives.”

The use of EDCs largely began post-WWII with pesticides such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), but over time came to include use as thickeners, plastic softeners, and scent in many common household items. Dr. Gore told a reporter that even though these chemicals were not intended to enter the environment at large, decades of use has made their entry into the food chain inevitable. The population health effects of this are only now becoming evident as data accumulate linking EDCs to a constellation of ill health effects.

“In humans, there are strong epidemiological associations between EDCs and chronic diseases.” Dr. Gore said.

She specifically cited obesity, diabetes, and a range of reproductive disorders, including infertility and certain hormone-related cancers. Research also shows a link between prenatal EDC exposure in animals to obesity, insulin resistance, and overabundant insulin later in life.

The Society’s meta-analysis of more than 1,300 studies published in the last 5 years also implicated EDCs in disorders of the prostate gland, the thyroid, and the neuroendocrine systems, the latter two being particularly vulnerable because of their role in hormone regulation at all stages of development.

“We’re particularly concerned about fetuses and how exposure can set the stage for later development of diseases,” Dr. Gore said, noting that human studies have shown a link between higher EDC exposures over time and cognitive deficits and other adverse neurocognitive outcomes.

Because the effect of EDC exposure differs according to the dose, length, and timing of exposure, designing studies to measure any harm has been difficult, said Dr. Gore, although in the past 5 years, there has been increased insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying EDCs.

Among the most common EDCs are bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, synthetic chemicals that bind to hormone receptors and depending upon the dose, either potentiate, inhibit – or both – the hormone’s effect on receptors. These EDCs frequently occur in toys, bottle nipples, rain coats, shower curtains, and in medical supplies such as blood bags, IV tubing, and catheters.

Initially registered as a pesticide, the EDC triclosan’s antimicrobial power has meant it is now used in deodorants and even in toothpaste. Triclosan has been shown to disrupt the thyroid, and to have antiestrogenic, and antiandrogenic properties. It also has been linked to asthma.

Plastic water bottles and disposable, plastic-based food packaging commonly found in microwaveable products often are high in BPAs, according to Dr. Gore, who urged all primary care physicians to counsel patients on the importance of avoiding products that contain them whenever possible, particularly in cases of pediatric obesity or diabetes, and for patients who are pregnant or in the family-planning stages. “You might not see an adverse outcome until years or decades later.”

Because many EDCs are lipophilic, our bodies often store them in our fat cells, often for years at a time.

While bisphenol A tends to exit the body quickly, we are commonly exposed to it on a daily basis, usually through a compound that leaches into our food, allowing the chemical an opportunity to exert an effect, even if the results of this effect aren’t immediately apparent. “If it’s a pregnant woman or someone planning a family, that exposure can change something,” Dr. Gore warned.

Although earlier studies had linked EDC exposure to a variety of reproductive health concerns, Dr. Gore said that since the Society’s last statement, there is much more corroborating evidence. In particular, polycystic ovarian syndrome in humans has been associated with higher body burdens of BPA and other chemicals, as have endometriosis, fibroids, and some adverse birth outcomes. Still, much of the data come from animal studies, and studies of specific links between EDCs and reproductive outcomes and cancers are inconsistent.

According to Dr. Renee Howard, a pediatric dermatologist with Sutter Health in San Francisco, who regularly gives presentations on the effects of EDCs in cosmetics and other skin care products, although much of the current research shows a link between EDCs and chronic illness, so far a causal relationship has not been established. Still, she said she routinely tells other physicians to keep an “open mind” when discussing EDCs with patients.

“We can acknowledge there is uncertainty, and we can tell patients that these chemicals are actively being studied, but that the studies are, as of now, inconclusive, and that there are still no documented adverse health effects associated with skin care products,” Dr. Howard said. Nevertheless, she said common sense dictates her to counsel patients to avoid products containing the EDC triclosan such as antimicrobials and scented products. She also advises them to eat organic produce in order to avoid pesticides.

Dr. Gore and her coauthors hope the statement will help bump EDC oversight higher up the policy chain globally.

“Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals during early development can have long-lasting, even permanent consequences,” Endocrine Society member Dr. Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, a professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Liège in Belgium, said in a statement. “The science is clear, and it’s time for policy makers to take this wealth of evidence into account as they develop legislation.”

To that end, earlier this year, twin bills are now before the House and Senate, which – if passed – will take effect in 2018, banning the sale of any personal care products containing microbeads, BPA-rich, microscopic plastic particles that have entered much of the natural water supply, threatening marine life which often mistake the tiny bits as food. Meanwhile, Minnesota has banned the use of triclosan statewide as of 2017.

Dr. Gore also said in addition to funding for this research being made a priority, it’s time to rethink who gets to be in on the science. Rather than just industrial chemists, she believes the teams should include so-called “green chemists,” basic, translational, and clinical scientists; epidemiologists, as well as public health professionals. Health care providers should be familiar with endocrine science and the latest developments in EDC research, accordingly, because, said Dr. Gore, “The [health] costs of EDCs have been estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Prevention might seem expensive, but it’s far-less-expensive than all the ensuing diseases.”

Most of all, Dr. Gore and her colleagues emphasize that there will never be “absolute proof” of anything, but that taking action to stem exposure is essential.

The analysis was sponsored by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Gore is editor in chief of Endocrinology. Dr. Howard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Cash register receipts, tin can linings, and a range of cosmetics and other common household products increasingly are implicated in the most intractable of society’s diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

So-called endocrine-disrupting chemicals have become so common, according to the Washington-based Endocrine Society, that nearly every human alive has been exposed to at least one such chemical, probably more than once, and just as likely, over an extended period of time.

The World Health Organization reports that there are more than 800 known endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) used in products globally, but only a fraction of them have been tested in humans. What effects, if any, this exposure is having on individuals is still unknown, but data linking the ability of EDCs – either singularly or in combination – to mimic, block, or otherwise interfere with the body’s natural hormone signaling has some experts sounding the alarm.

“The evidence is more definitive than ever before – EDCs disrupt hormones in a manner that harms human health,” Andrea C. Gore, Ph.D., a pharmacology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a press conference. Dr. Gore chairs the Endocrine Society task force that recently released an executive summary of its second scientific statement on EDCs. The Society presented the statement, an update of one released in 2009, at this year’s International Conference on Chemicals Management annual meeting in Geneva.

Because the endocrine system’s role is to interact with the environment, it is predisposed to react to triggers increasingly found in everything from pesticides to shower curtains, which have now made their way into waterways and the food chain primarily without any studies on their impact. “Both natural hormones and EDCs have unique dose-response properties [and can] act at very-low doses,” Dr. Gore told reporters. “We’re exposed throughout our lives.”

The use of EDCs largely began post-WWII with pesticides such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), but over time came to include use as thickeners, plastic softeners, and scent in many common household items. Dr. Gore told a reporter that even though these chemicals were not intended to enter the environment at large, decades of use has made their entry into the food chain inevitable. The population health effects of this are only now becoming evident as data accumulate linking EDCs to a constellation of ill health effects.

“In humans, there are strong epidemiological associations between EDCs and chronic diseases.” Dr. Gore said.

She specifically cited obesity, diabetes, and a range of reproductive disorders, including infertility and certain hormone-related cancers. Research also shows a link between prenatal EDC exposure in animals to obesity, insulin resistance, and overabundant insulin later in life.

The Society’s meta-analysis of more than 1,300 studies published in the last 5 years also implicated EDCs in disorders of the prostate gland, the thyroid, and the neuroendocrine systems, the latter two being particularly vulnerable because of their role in hormone regulation at all stages of development.

“We’re particularly concerned about fetuses and how exposure can set the stage for later development of diseases,” Dr. Gore said, noting that human studies have shown a link between higher EDC exposures over time and cognitive deficits and other adverse neurocognitive outcomes.

Because the effect of EDC exposure differs according to the dose, length, and timing of exposure, designing studies to measure any harm has been difficult, said Dr. Gore, although in the past 5 years, there has been increased insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying EDCs.

Among the most common EDCs are bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, synthetic chemicals that bind to hormone receptors and depending upon the dose, either potentiate, inhibit – or both – the hormone’s effect on receptors. These EDCs frequently occur in toys, bottle nipples, rain coats, shower curtains, and in medical supplies such as blood bags, IV tubing, and catheters.

Initially registered as a pesticide, the EDC triclosan’s antimicrobial power has meant it is now used in deodorants and even in toothpaste. Triclosan has been shown to disrupt the thyroid, and to have antiestrogenic, and antiandrogenic properties. It also has been linked to asthma.

Plastic water bottles and disposable, plastic-based food packaging commonly found in microwaveable products often are high in BPAs, according to Dr. Gore, who urged all primary care physicians to counsel patients on the importance of avoiding products that contain them whenever possible, particularly in cases of pediatric obesity or diabetes, and for patients who are pregnant or in the family-planning stages. “You might not see an adverse outcome until years or decades later.”

Because many EDCs are lipophilic, our bodies often store them in our fat cells, often for years at a time.

While bisphenol A tends to exit the body quickly, we are commonly exposed to it on a daily basis, usually through a compound that leaches into our food, allowing the chemical an opportunity to exert an effect, even if the results of this effect aren’t immediately apparent. “If it’s a pregnant woman or someone planning a family, that exposure can change something,” Dr. Gore warned.

Although earlier studies had linked EDC exposure to a variety of reproductive health concerns, Dr. Gore said that since the Society’s last statement, there is much more corroborating evidence. In particular, polycystic ovarian syndrome in humans has been associated with higher body burdens of BPA and other chemicals, as have endometriosis, fibroids, and some adverse birth outcomes. Still, much of the data come from animal studies, and studies of specific links between EDCs and reproductive outcomes and cancers are inconsistent.

According to Dr. Renee Howard, a pediatric dermatologist with Sutter Health in San Francisco, who regularly gives presentations on the effects of EDCs in cosmetics and other skin care products, although much of the current research shows a link between EDCs and chronic illness, so far a causal relationship has not been established. Still, she said she routinely tells other physicians to keep an “open mind” when discussing EDCs with patients.

“We can acknowledge there is uncertainty, and we can tell patients that these chemicals are actively being studied, but that the studies are, as of now, inconclusive, and that there are still no documented adverse health effects associated with skin care products,” Dr. Howard said. Nevertheless, she said common sense dictates her to counsel patients to avoid products containing the EDC triclosan such as antimicrobials and scented products. She also advises them to eat organic produce in order to avoid pesticides.

Dr. Gore and her coauthors hope the statement will help bump EDC oversight higher up the policy chain globally.

“Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals during early development can have long-lasting, even permanent consequences,” Endocrine Society member Dr. Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, a professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Liège in Belgium, said in a statement. “The science is clear, and it’s time for policy makers to take this wealth of evidence into account as they develop legislation.”

To that end, earlier this year, twin bills are now before the House and Senate, which – if passed – will take effect in 2018, banning the sale of any personal care products containing microbeads, BPA-rich, microscopic plastic particles that have entered much of the natural water supply, threatening marine life which often mistake the tiny bits as food. Meanwhile, Minnesota has banned the use of triclosan statewide as of 2017.

Dr. Gore also said in addition to funding for this research being made a priority, it’s time to rethink who gets to be in on the science. Rather than just industrial chemists, she believes the teams should include so-called “green chemists,” basic, translational, and clinical scientists; epidemiologists, as well as public health professionals. Health care providers should be familiar with endocrine science and the latest developments in EDC research, accordingly, because, said Dr. Gore, “The [health] costs of EDCs have been estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Prevention might seem expensive, but it’s far-less-expensive than all the ensuing diseases.”

Most of all, Dr. Gore and her colleagues emphasize that there will never be “absolute proof” of anything, but that taking action to stem exposure is essential.

The analysis was sponsored by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Gore is editor in chief of Endocrinology. Dr. Howard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Cash register receipts, tin can linings, and a range of cosmetics and other common household products increasingly are implicated in the most intractable of society’s diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

So-called endocrine-disrupting chemicals have become so common, according to the Washington-based Endocrine Society, that nearly every human alive has been exposed to at least one such chemical, probably more than once, and just as likely, over an extended period of time.

The World Health Organization reports that there are more than 800 known endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) used in products globally, but only a fraction of them have been tested in humans. What effects, if any, this exposure is having on individuals is still unknown, but data linking the ability of EDCs – either singularly or in combination – to mimic, block, or otherwise interfere with the body’s natural hormone signaling has some experts sounding the alarm.

“The evidence is more definitive than ever before – EDCs disrupt hormones in a manner that harms human health,” Andrea C. Gore, Ph.D., a pharmacology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a press conference. Dr. Gore chairs the Endocrine Society task force that recently released an executive summary of its second scientific statement on EDCs. The Society presented the statement, an update of one released in 2009, at this year’s International Conference on Chemicals Management annual meeting in Geneva.

Because the endocrine system’s role is to interact with the environment, it is predisposed to react to triggers increasingly found in everything from pesticides to shower curtains, which have now made their way into waterways and the food chain primarily without any studies on their impact. “Both natural hormones and EDCs have unique dose-response properties [and can] act at very-low doses,” Dr. Gore told reporters. “We’re exposed throughout our lives.”

The use of EDCs largely began post-WWII with pesticides such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), but over time came to include use as thickeners, plastic softeners, and scent in many common household items. Dr. Gore told a reporter that even though these chemicals were not intended to enter the environment at large, decades of use has made their entry into the food chain inevitable. The population health effects of this are only now becoming evident as data accumulate linking EDCs to a constellation of ill health effects.

“In humans, there are strong epidemiological associations between EDCs and chronic diseases.” Dr. Gore said.

She specifically cited obesity, diabetes, and a range of reproductive disorders, including infertility and certain hormone-related cancers. Research also shows a link between prenatal EDC exposure in animals to obesity, insulin resistance, and overabundant insulin later in life.

The Society’s meta-analysis of more than 1,300 studies published in the last 5 years also implicated EDCs in disorders of the prostate gland, the thyroid, and the neuroendocrine systems, the latter two being particularly vulnerable because of their role in hormone regulation at all stages of development.

“We’re particularly concerned about fetuses and how exposure can set the stage for later development of diseases,” Dr. Gore said, noting that human studies have shown a link between higher EDC exposures over time and cognitive deficits and other adverse neurocognitive outcomes.

Because the effect of EDC exposure differs according to the dose, length, and timing of exposure, designing studies to measure any harm has been difficult, said Dr. Gore, although in the past 5 years, there has been increased insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying EDCs.

Among the most common EDCs are bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, synthetic chemicals that bind to hormone receptors and depending upon the dose, either potentiate, inhibit – or both – the hormone’s effect on receptors. These EDCs frequently occur in toys, bottle nipples, rain coats, shower curtains, and in medical supplies such as blood bags, IV tubing, and catheters.

Initially registered as a pesticide, the EDC triclosan’s antimicrobial power has meant it is now used in deodorants and even in toothpaste. Triclosan has been shown to disrupt the thyroid, and to have antiestrogenic, and antiandrogenic properties. It also has been linked to asthma.

Plastic water bottles and disposable, plastic-based food packaging commonly found in microwaveable products often are high in BPAs, according to Dr. Gore, who urged all primary care physicians to counsel patients on the importance of avoiding products that contain them whenever possible, particularly in cases of pediatric obesity or diabetes, and for patients who are pregnant or in the family-planning stages. “You might not see an adverse outcome until years or decades later.”

Because many EDCs are lipophilic, our bodies often store them in our fat cells, often for years at a time.

While bisphenol A tends to exit the body quickly, we are commonly exposed to it on a daily basis, usually through a compound that leaches into our food, allowing the chemical an opportunity to exert an effect, even if the results of this effect aren’t immediately apparent. “If it’s a pregnant woman or someone planning a family, that exposure can change something,” Dr. Gore warned.

Although earlier studies had linked EDC exposure to a variety of reproductive health concerns, Dr. Gore said that since the Society’s last statement, there is much more corroborating evidence. In particular, polycystic ovarian syndrome in humans has been associated with higher body burdens of BPA and other chemicals, as have endometriosis, fibroids, and some adverse birth outcomes. Still, much of the data come from animal studies, and studies of specific links between EDCs and reproductive outcomes and cancers are inconsistent.

According to Dr. Renee Howard, a pediatric dermatologist with Sutter Health in San Francisco, who regularly gives presentations on the effects of EDCs in cosmetics and other skin care products, although much of the current research shows a link between EDCs and chronic illness, so far a causal relationship has not been established. Still, she said she routinely tells other physicians to keep an “open mind” when discussing EDCs with patients.

“We can acknowledge there is uncertainty, and we can tell patients that these chemicals are actively being studied, but that the studies are, as of now, inconclusive, and that there are still no documented adverse health effects associated with skin care products,” Dr. Howard said. Nevertheless, she said common sense dictates her to counsel patients to avoid products containing the EDC triclosan such as antimicrobials and scented products. She also advises them to eat organic produce in order to avoid pesticides.

Dr. Gore and her coauthors hope the statement will help bump EDC oversight higher up the policy chain globally.

“Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals during early development can have long-lasting, even permanent consequences,” Endocrine Society member Dr. Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, a professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Liège in Belgium, said in a statement. “The science is clear, and it’s time for policy makers to take this wealth of evidence into account as they develop legislation.”

To that end, earlier this year, twin bills are now before the House and Senate, which – if passed – will take effect in 2018, banning the sale of any personal care products containing microbeads, BPA-rich, microscopic plastic particles that have entered much of the natural water supply, threatening marine life which often mistake the tiny bits as food. Meanwhile, Minnesota has banned the use of triclosan statewide as of 2017.

Dr. Gore also said in addition to funding for this research being made a priority, it’s time to rethink who gets to be in on the science. Rather than just industrial chemists, she believes the teams should include so-called “green chemists,” basic, translational, and clinical scientists; epidemiologists, as well as public health professionals. Health care providers should be familiar with endocrine science and the latest developments in EDC research, accordingly, because, said Dr. Gore, “The [health] costs of EDCs have been estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Prevention might seem expensive, but it’s far-less-expensive than all the ensuing diseases.”

Most of all, Dr. Gore and her colleagues emphasize that there will never be “absolute proof” of anything, but that taking action to stem exposure is essential.

The analysis was sponsored by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Gore is editor in chief of Endocrinology. Dr. Howard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Long-acting insulin degludec – and degludec combo drug – win FDA nod

Two new insulins have gained FDA approval.

Insulin degludec (Tresiba) and insulin degludec/insulin aspart (Ryzodeg 70/30) – both manufactured by Novo Nordisk – have been shown to improve glucose control in adults with hard-to-regulate type 1 diabetes, and in patients with advanced type 2 diabetes, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approvals on Sept. 25.

Insulin degludec is intended to be used as add-on therapy to prandial insulin or oral antidiabetic drugs. Findings from 9 randomized studies comprising almost 4,000 patients supported the approval: three in patients with type 1 disease and six in patients with type 2 disease.

Three trials comprising 1,102 patients with type 1 diabetes examined degludec in combination with prandial insulin or oral therapy. Six trials comprising 2,702 patients with type 2 diabetes also examined the drug in combination with prandial insulin or as an add-on to oral therapy. In all of these studies, degludec was associated with reductions in HbA1c.

The combination of the long-acting insulin degludec and rapid-acting insulin aspart was evaluated in five studies – one with 362 patients with type 1 diabetes and four comprising 998 patients with type 2 disease.

In the first study, the drug was used with prandial insulin. In the second group of studies, it was administered once or twice a day as the sole treatment.

Both Tresiba and Ryzodeg have been approved in Europe, Mexico, and Japan.

The most common adverse reactions associated with both drugs in clinical trials were hypoglycemia, allergic reactions, injection site reactions, lipodystrophy, itching, rash, edema, and weight gain, according to the FDA.

In 2013, FDA refused to approve either of these drugs, despite a positive recommendation from the review committee. The agency asked for additional cardiovascular risk data, which Novo Nordisk is now acquiring with a 7,600-patient study called DEVOTE. DEVOTE is set to be completed in 2016; it is designed to generate follow-up data for 2 additional years.

In April, the company resubmitted its new drug application based on the study’s interim results, which are not publicly available.

Two new insulins have gained FDA approval.

Insulin degludec (Tresiba) and insulin degludec/insulin aspart (Ryzodeg 70/30) – both manufactured by Novo Nordisk – have been shown to improve glucose control in adults with hard-to-regulate type 1 diabetes, and in patients with advanced type 2 diabetes, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approvals on Sept. 25.

Insulin degludec is intended to be used as add-on therapy to prandial insulin or oral antidiabetic drugs. Findings from 9 randomized studies comprising almost 4,000 patients supported the approval: three in patients with type 1 disease and six in patients with type 2 disease.

Three trials comprising 1,102 patients with type 1 diabetes examined degludec in combination with prandial insulin or oral therapy. Six trials comprising 2,702 patients with type 2 diabetes also examined the drug in combination with prandial insulin or as an add-on to oral therapy. In all of these studies, degludec was associated with reductions in HbA1c.

The combination of the long-acting insulin degludec and rapid-acting insulin aspart was evaluated in five studies – one with 362 patients with type 1 diabetes and four comprising 998 patients with type 2 disease.

In the first study, the drug was used with prandial insulin. In the second group of studies, it was administered once or twice a day as the sole treatment.

Both Tresiba and Ryzodeg have been approved in Europe, Mexico, and Japan.

The most common adverse reactions associated with both drugs in clinical trials were hypoglycemia, allergic reactions, injection site reactions, lipodystrophy, itching, rash, edema, and weight gain, according to the FDA.

In 2013, FDA refused to approve either of these drugs, despite a positive recommendation from the review committee. The agency asked for additional cardiovascular risk data, which Novo Nordisk is now acquiring with a 7,600-patient study called DEVOTE. DEVOTE is set to be completed in 2016; it is designed to generate follow-up data for 2 additional years.

In April, the company resubmitted its new drug application based on the study’s interim results, which are not publicly available.

Two new insulins have gained FDA approval.

Insulin degludec (Tresiba) and insulin degludec/insulin aspart (Ryzodeg 70/30) – both manufactured by Novo Nordisk – have been shown to improve glucose control in adults with hard-to-regulate type 1 diabetes, and in patients with advanced type 2 diabetes, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approvals on Sept. 25.

Insulin degludec is intended to be used as add-on therapy to prandial insulin or oral antidiabetic drugs. Findings from 9 randomized studies comprising almost 4,000 patients supported the approval: three in patients with type 1 disease and six in patients with type 2 disease.

Three trials comprising 1,102 patients with type 1 diabetes examined degludec in combination with prandial insulin or oral therapy. Six trials comprising 2,702 patients with type 2 diabetes also examined the drug in combination with prandial insulin or as an add-on to oral therapy. In all of these studies, degludec was associated with reductions in HbA1c.

The combination of the long-acting insulin degludec and rapid-acting insulin aspart was evaluated in five studies – one with 362 patients with type 1 diabetes and four comprising 998 patients with type 2 disease.

In the first study, the drug was used with prandial insulin. In the second group of studies, it was administered once or twice a day as the sole treatment.

Both Tresiba and Ryzodeg have been approved in Europe, Mexico, and Japan.

The most common adverse reactions associated with both drugs in clinical trials were hypoglycemia, allergic reactions, injection site reactions, lipodystrophy, itching, rash, edema, and weight gain, according to the FDA.

In 2013, FDA refused to approve either of these drugs, despite a positive recommendation from the review committee. The agency asked for additional cardiovascular risk data, which Novo Nordisk is now acquiring with a 7,600-patient study called DEVOTE. DEVOTE is set to be completed in 2016; it is designed to generate follow-up data for 2 additional years.

In April, the company resubmitted its new drug application based on the study’s interim results, which are not publicly available.

In type 2 diabetes, pump therapy costs more but saves much

STOCKHOLM – Insulin pump therapy is considerably more expensive than daily insulin injections for patients with type 2 diabetes, but the benefits it confers offset about 30% of the price difference.

A cost-modeling study showed that patients who use the pump gain almost another year of life expectancy and experience a delay in the onset of major complications, such as end-stage renal disease and amputation, Stephane Roze said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Pump therapy also conferred a significantly improved quality of life over multiple daily injections, a benefit that carries its own economic value, said Mr. Roze of HEVA-HEOR, a health economics evaluation company in Lyon, France.

“Even though these patients are initiating the pump at an older age than patients with type 1 diabetes, the therapy still looks to be cost effective,” he said. “It’s a good investment for payers.”

Mr. Roze used the CORE Diabetes Model to examine the cost/benefit ratio of insulin pump therapy, compared with multiple daily injections in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes who lived in the Netherlands. The CORE model comprises 14 sub-Markov models that run in parallel; it examines all of the micro- and macrovascular complications related to diabetes. Model input data were the cohort characteristics and 6-month clinical outcomes of the OpT2mise study.

The trial examined glucose variability in 331 patients with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to either pump therapy or daily insulin injections.

It is an excellent study for cost-modeling initiatives, Mr. Roze said. It’s multicenter and multinational, conducted in 36 institutions in the United States, Canada, Europe, Israel, and South Africa. The cohort is large and diverse. Importantly, all of the patients had their treatment optimized with daily insulin analogue injections before being randomized. That initial step lent credence to their baseline glucose control; despite optimization, they still had a mean hemoglobin A1cof 9%. The OpT2mise patients were a mean of 56 years old, with mean disease duration of 15 years.

At 6 months, the study showed that HbA1c had decreased significantly more in the pump group than in the injection group (1.1% vs. 0.4%). Patients using the pump also needed significantly lower daily insulin doses (97 unit/kg per day vs. 122 unit/kg per day).

These results were inputted into the CORE model, along with the costs of diabetes-related complications in the Netherlands and the costs of both pump therapy and daily insulin injections. For the first year of treatment, pump therapy more than twice as expensive as daily injections (4,407 euros vs. 1,597 euros). This difference remained when costs were extrapolated to year 2 and beyond (4,365 euros vs. 1,555 euros).

The model, however, determined that pump therapy has the potential to extend life expectancy by almost 1 year, compared with injection therapy, by reducing and/or delaying life-threatening diabetes complications. These clinical benefits translated into an additional 9.38 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) for patients using the pump, compared with 8.95 QALY for patients using injections.

Over a lifetime of treatment (13 years), pump therapy would cost a total of 58,024 euros, compared with 20,237 euros for injection therapy – a difference of 37,787 euros. Compared with injection therapy, though, pump therapy would save almost 10,000 euros in the cost of renal complications; 625 euros in the cost of ulcer, amputation, and neuropathy complications; 152 euros in the cost of eye complications; and 410 euros in complications due to hypoglycemia. These savings reduced the total cost difference between the two to 27,051 euros, Mr. Roze said.

The benefits held over time, despite the paradox of survivorship, he said. “The longer a patient with chronic disease lives, the more opportunity they have to develop a complication.”

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was 62,295 euros/QALY – an amount that falls well within the Netherlands’ “willingness to pay” threshold, which is a measure of what payers or society are generally willing to accept as a good value for health care expenditures.

The newest data from OpT2mise, also released at EASD, bolster Mr. Roze’s modeling. In phase II of the study, patients who had been on injections crossed over to pump therapy. Within 6 months of crossover, these patients experienced a mean HbA1c decrease of 0.8%. By 12 months from study start, when all patients had been on pump therapy for at least 6 months, the mean HbA1chad dropped to 7.8% from baseline.

“We were reassured to see the 12-month data, which confirm the sustainability of the effect,” Mr. Roze said. “This is one of the main questions when you do health care modeling.”

Mr. Roze is a co-owner of HEVA-HEOR.

STOCKHOLM – Insulin pump therapy is considerably more expensive than daily insulin injections for patients with type 2 diabetes, but the benefits it confers offset about 30% of the price difference.

A cost-modeling study showed that patients who use the pump gain almost another year of life expectancy and experience a delay in the onset of major complications, such as end-stage renal disease and amputation, Stephane Roze said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Pump therapy also conferred a significantly improved quality of life over multiple daily injections, a benefit that carries its own economic value, said Mr. Roze of HEVA-HEOR, a health economics evaluation company in Lyon, France.

“Even though these patients are initiating the pump at an older age than patients with type 1 diabetes, the therapy still looks to be cost effective,” he said. “It’s a good investment for payers.”

Mr. Roze used the CORE Diabetes Model to examine the cost/benefit ratio of insulin pump therapy, compared with multiple daily injections in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes who lived in the Netherlands. The CORE model comprises 14 sub-Markov models that run in parallel; it examines all of the micro- and macrovascular complications related to diabetes. Model input data were the cohort characteristics and 6-month clinical outcomes of the OpT2mise study.

The trial examined glucose variability in 331 patients with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to either pump therapy or daily insulin injections.

It is an excellent study for cost-modeling initiatives, Mr. Roze said. It’s multicenter and multinational, conducted in 36 institutions in the United States, Canada, Europe, Israel, and South Africa. The cohort is large and diverse. Importantly, all of the patients had their treatment optimized with daily insulin analogue injections before being randomized. That initial step lent credence to their baseline glucose control; despite optimization, they still had a mean hemoglobin A1cof 9%. The OpT2mise patients were a mean of 56 years old, with mean disease duration of 15 years.

At 6 months, the study showed that HbA1c had decreased significantly more in the pump group than in the injection group (1.1% vs. 0.4%). Patients using the pump also needed significantly lower daily insulin doses (97 unit/kg per day vs. 122 unit/kg per day).

These results were inputted into the CORE model, along with the costs of diabetes-related complications in the Netherlands and the costs of both pump therapy and daily insulin injections. For the first year of treatment, pump therapy more than twice as expensive as daily injections (4,407 euros vs. 1,597 euros). This difference remained when costs were extrapolated to year 2 and beyond (4,365 euros vs. 1,555 euros).

The model, however, determined that pump therapy has the potential to extend life expectancy by almost 1 year, compared with injection therapy, by reducing and/or delaying life-threatening diabetes complications. These clinical benefits translated into an additional 9.38 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) for patients using the pump, compared with 8.95 QALY for patients using injections.

Over a lifetime of treatment (13 years), pump therapy would cost a total of 58,024 euros, compared with 20,237 euros for injection therapy – a difference of 37,787 euros. Compared with injection therapy, though, pump therapy would save almost 10,000 euros in the cost of renal complications; 625 euros in the cost of ulcer, amputation, and neuropathy complications; 152 euros in the cost of eye complications; and 410 euros in complications due to hypoglycemia. These savings reduced the total cost difference between the two to 27,051 euros, Mr. Roze said.

The benefits held over time, despite the paradox of survivorship, he said. “The longer a patient with chronic disease lives, the more opportunity they have to develop a complication.”

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was 62,295 euros/QALY – an amount that falls well within the Netherlands’ “willingness to pay” threshold, which is a measure of what payers or society are generally willing to accept as a good value for health care expenditures.

The newest data from OpT2mise, also released at EASD, bolster Mr. Roze’s modeling. In phase II of the study, patients who had been on injections crossed over to pump therapy. Within 6 months of crossover, these patients experienced a mean HbA1c decrease of 0.8%. By 12 months from study start, when all patients had been on pump therapy for at least 6 months, the mean HbA1chad dropped to 7.8% from baseline.

“We were reassured to see the 12-month data, which confirm the sustainability of the effect,” Mr. Roze said. “This is one of the main questions when you do health care modeling.”

Mr. Roze is a co-owner of HEVA-HEOR.

STOCKHOLM – Insulin pump therapy is considerably more expensive than daily insulin injections for patients with type 2 diabetes, but the benefits it confers offset about 30% of the price difference.

A cost-modeling study showed that patients who use the pump gain almost another year of life expectancy and experience a delay in the onset of major complications, such as end-stage renal disease and amputation, Stephane Roze said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Pump therapy also conferred a significantly improved quality of life over multiple daily injections, a benefit that carries its own economic value, said Mr. Roze of HEVA-HEOR, a health economics evaluation company in Lyon, France.

“Even though these patients are initiating the pump at an older age than patients with type 1 diabetes, the therapy still looks to be cost effective,” he said. “It’s a good investment for payers.”

Mr. Roze used the CORE Diabetes Model to examine the cost/benefit ratio of insulin pump therapy, compared with multiple daily injections in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes who lived in the Netherlands. The CORE model comprises 14 sub-Markov models that run in parallel; it examines all of the micro- and macrovascular complications related to diabetes. Model input data were the cohort characteristics and 6-month clinical outcomes of the OpT2mise study.

The trial examined glucose variability in 331 patients with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to either pump therapy or daily insulin injections.

It is an excellent study for cost-modeling initiatives, Mr. Roze said. It’s multicenter and multinational, conducted in 36 institutions in the United States, Canada, Europe, Israel, and South Africa. The cohort is large and diverse. Importantly, all of the patients had their treatment optimized with daily insulin analogue injections before being randomized. That initial step lent credence to their baseline glucose control; despite optimization, they still had a mean hemoglobin A1cof 9%. The OpT2mise patients were a mean of 56 years old, with mean disease duration of 15 years.

At 6 months, the study showed that HbA1c had decreased significantly more in the pump group than in the injection group (1.1% vs. 0.4%). Patients using the pump also needed significantly lower daily insulin doses (97 unit/kg per day vs. 122 unit/kg per day).

These results were inputted into the CORE model, along with the costs of diabetes-related complications in the Netherlands and the costs of both pump therapy and daily insulin injections. For the first year of treatment, pump therapy more than twice as expensive as daily injections (4,407 euros vs. 1,597 euros). This difference remained when costs were extrapolated to year 2 and beyond (4,365 euros vs. 1,555 euros).

The model, however, determined that pump therapy has the potential to extend life expectancy by almost 1 year, compared with injection therapy, by reducing and/or delaying life-threatening diabetes complications. These clinical benefits translated into an additional 9.38 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) for patients using the pump, compared with 8.95 QALY for patients using injections.

Over a lifetime of treatment (13 years), pump therapy would cost a total of 58,024 euros, compared with 20,237 euros for injection therapy – a difference of 37,787 euros. Compared with injection therapy, though, pump therapy would save almost 10,000 euros in the cost of renal complications; 625 euros in the cost of ulcer, amputation, and neuropathy complications; 152 euros in the cost of eye complications; and 410 euros in complications due to hypoglycemia. These savings reduced the total cost difference between the two to 27,051 euros, Mr. Roze said.

The benefits held over time, despite the paradox of survivorship, he said. “The longer a patient with chronic disease lives, the more opportunity they have to develop a complication.”

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was 62,295 euros/QALY – an amount that falls well within the Netherlands’ “willingness to pay” threshold, which is a measure of what payers or society are generally willing to accept as a good value for health care expenditures.