User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Lifestyle intervention can reduce gestational diabetes incidence

The incidence of gestational diabetes can be reduced in high-risk women with individualized lifestyle intervention focused on diet and physical activity, new research suggests.

A randomized, controlled trial of 269 women with a history of gestational diabetes or a prepregnancy body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 showed the intervention was associated with a 36% reduction in the incidence of gestational diabetes, compared with usual care (13.9% vs. 21.6%, P = .044).

This was after adjustment for age, prepregnancy BMI, previous gestational diabetes status, and number of weeks’ gestation at the time of the oral glucose tolerance test, according to a paper published online July 29 in Diabetes Care.

From baseline to the second trimester oral glucose tolerance test – when the gestational diabetes diagnosis was made – women in the intervention group gained slightly less weight than did those in the control group (2.5 kg vs. 3.1 kg).

The intervention was associated with a significantly greater reduction in fasting plasma glucose concentration from baseline to third trimester, but there were no impacts on other pregnancy or birth outcomes such as preeclampsia, birth weight, or gestational age at birth.

“This is, to our knowledge, the first randomized controlled lifestyle intervention trial that has succeeded in reducing the overall incidence of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] among high-risk pregnant women,” wrote Dr. Saila B. Koivusalo of University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital.

Women in the intervention arm were counseled by study nurses and dietitians three times during their pregnancy. Counseling was tailored to their risk and stage of pregnancy. The women continued their normal antenatal clinic visits (Diabetes Care 2015, Jul 29 [doi:10.2337/dc15-0511]).

Women with a prepregnancy BMI of 30 kg/m2 were advised not to gain any weight during the first two trimesters, and were given dietary counseling to optimize their consumption of healthy foods and reduce their intake of sugar-rich foods.

They also were counseled to aim for a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, as part of an active lifestyle.

Participants in the control group received leaflets on diet and physical activity, which were usually provide by the local antenatal clinics.

Women who undertook the intervention showed significantly greater improvements in their dietary index scores than did those in the control arm, and they increased their median weekly physical activity by 15 minutes while the control group showed no increases.

However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of women who met the physical activity goal of 150 minutes/week in their second trimester (26% of intervention group vs. 23% of the control group).

“Despite the fact that only a small proportion of the women in the intervention group reached the physical activity goals, and the difference in weight gain was modest between the groups, it is obvious that the individual changes in lifestyle do not need to be large but together they have a beneficial effect on the reduction of the incidence of GDM,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that as the women participating in the trial were all known to be at high risk for gestational diabetes, even the women in the control group would have received advice on weight control as part of their antenatal care and were therefore more of a “mini-intervention” group than pure control.

“We believe that in an unselected high-risk population the impact of this kind of lifestyle intervention could be even more pronounced.”

The Ahokas Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhälsan, Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, State Provincial Office of Southern Finland, and Social Insurance Institution of Finland funded the study. There were no conflicts of interest declared.

The incidence of gestational diabetes can be reduced in high-risk women with individualized lifestyle intervention focused on diet and physical activity, new research suggests.

A randomized, controlled trial of 269 women with a history of gestational diabetes or a prepregnancy body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 showed the intervention was associated with a 36% reduction in the incidence of gestational diabetes, compared with usual care (13.9% vs. 21.6%, P = .044).

This was after adjustment for age, prepregnancy BMI, previous gestational diabetes status, and number of weeks’ gestation at the time of the oral glucose tolerance test, according to a paper published online July 29 in Diabetes Care.

From baseline to the second trimester oral glucose tolerance test – when the gestational diabetes diagnosis was made – women in the intervention group gained slightly less weight than did those in the control group (2.5 kg vs. 3.1 kg).

The intervention was associated with a significantly greater reduction in fasting plasma glucose concentration from baseline to third trimester, but there were no impacts on other pregnancy or birth outcomes such as preeclampsia, birth weight, or gestational age at birth.

“This is, to our knowledge, the first randomized controlled lifestyle intervention trial that has succeeded in reducing the overall incidence of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] among high-risk pregnant women,” wrote Dr. Saila B. Koivusalo of University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital.

Women in the intervention arm were counseled by study nurses and dietitians three times during their pregnancy. Counseling was tailored to their risk and stage of pregnancy. The women continued their normal antenatal clinic visits (Diabetes Care 2015, Jul 29 [doi:10.2337/dc15-0511]).

Women with a prepregnancy BMI of 30 kg/m2 were advised not to gain any weight during the first two trimesters, and were given dietary counseling to optimize their consumption of healthy foods and reduce their intake of sugar-rich foods.

They also were counseled to aim for a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, as part of an active lifestyle.

Participants in the control group received leaflets on diet and physical activity, which were usually provide by the local antenatal clinics.

Women who undertook the intervention showed significantly greater improvements in their dietary index scores than did those in the control arm, and they increased their median weekly physical activity by 15 minutes while the control group showed no increases.

However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of women who met the physical activity goal of 150 minutes/week in their second trimester (26% of intervention group vs. 23% of the control group).

“Despite the fact that only a small proportion of the women in the intervention group reached the physical activity goals, and the difference in weight gain was modest between the groups, it is obvious that the individual changes in lifestyle do not need to be large but together they have a beneficial effect on the reduction of the incidence of GDM,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that as the women participating in the trial were all known to be at high risk for gestational diabetes, even the women in the control group would have received advice on weight control as part of their antenatal care and were therefore more of a “mini-intervention” group than pure control.

“We believe that in an unselected high-risk population the impact of this kind of lifestyle intervention could be even more pronounced.”

The Ahokas Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhälsan, Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, State Provincial Office of Southern Finland, and Social Insurance Institution of Finland funded the study. There were no conflicts of interest declared.

The incidence of gestational diabetes can be reduced in high-risk women with individualized lifestyle intervention focused on diet and physical activity, new research suggests.

A randomized, controlled trial of 269 women with a history of gestational diabetes or a prepregnancy body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 showed the intervention was associated with a 36% reduction in the incidence of gestational diabetes, compared with usual care (13.9% vs. 21.6%, P = .044).

This was after adjustment for age, prepregnancy BMI, previous gestational diabetes status, and number of weeks’ gestation at the time of the oral glucose tolerance test, according to a paper published online July 29 in Diabetes Care.

From baseline to the second trimester oral glucose tolerance test – when the gestational diabetes diagnosis was made – women in the intervention group gained slightly less weight than did those in the control group (2.5 kg vs. 3.1 kg).

The intervention was associated with a significantly greater reduction in fasting plasma glucose concentration from baseline to third trimester, but there were no impacts on other pregnancy or birth outcomes such as preeclampsia, birth weight, or gestational age at birth.

“This is, to our knowledge, the first randomized controlled lifestyle intervention trial that has succeeded in reducing the overall incidence of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] among high-risk pregnant women,” wrote Dr. Saila B. Koivusalo of University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital.

Women in the intervention arm were counseled by study nurses and dietitians three times during their pregnancy. Counseling was tailored to their risk and stage of pregnancy. The women continued their normal antenatal clinic visits (Diabetes Care 2015, Jul 29 [doi:10.2337/dc15-0511]).

Women with a prepregnancy BMI of 30 kg/m2 were advised not to gain any weight during the first two trimesters, and were given dietary counseling to optimize their consumption of healthy foods and reduce their intake of sugar-rich foods.

They also were counseled to aim for a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, as part of an active lifestyle.

Participants in the control group received leaflets on diet and physical activity, which were usually provide by the local antenatal clinics.

Women who undertook the intervention showed significantly greater improvements in their dietary index scores than did those in the control arm, and they increased their median weekly physical activity by 15 minutes while the control group showed no increases.

However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the number of women who met the physical activity goal of 150 minutes/week in their second trimester (26% of intervention group vs. 23% of the control group).

“Despite the fact that only a small proportion of the women in the intervention group reached the physical activity goals, and the difference in weight gain was modest between the groups, it is obvious that the individual changes in lifestyle do not need to be large but together they have a beneficial effect on the reduction of the incidence of GDM,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that as the women participating in the trial were all known to be at high risk for gestational diabetes, even the women in the control group would have received advice on weight control as part of their antenatal care and were therefore more of a “mini-intervention” group than pure control.

“We believe that in an unselected high-risk population the impact of this kind of lifestyle intervention could be even more pronounced.”

The Ahokas Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhälsan, Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, State Provincial Office of Southern Finland, and Social Insurance Institution of Finland funded the study. There were no conflicts of interest declared.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Key clinical point: Individualized lifestyle intervention focusing on diet and physical activity can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes in high-risk women.

Major finding: An individualized lifestyle intervention was associated with a 36% reduction in the incidence of gestational diabetes, compared with usual care.

Data source: A randomized, controlled trial of 269 women with a history of gestational diabetes or with a prepregnancy BMI of at least 30 kg/m2.

Disclosures: The Ahokas Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhälsan, Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, State Provincial Office of Southern Finland, and Social Insurance Institution of Finland funded the study. There were no conflicts of interest declared.

Diabetes in seniors increases dementia risk

A diagnosis of diabetes in later life is associated with an increased risk of dementia, particularly in individuals with preexisting vascular disease.

A population-based matched cohort study in 225,045 seniors newly diagnosed with diabetes and 668,070 without found a 16% higher risk of dementia among those with diabetes.

The association remained after adjustment for hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to a link between diabetes and dementia, with their shared cardiometabolic risk factors suggesting dementia may be yet another vascular complication of diabetes, wrote Dr. Nisha Nigil Haroon of the University of Toronto.

“We hypothesized that exposure to even short-term hyperglycemia in late life can trigger or accelerate cognitive decline and therefore that incident diabetes is a risk factor for dementia after accounting for differences in cardiovascular disease and other common risk factors,” wrote Dr. Haroon and her colleagues.

The risk of dementia was slightly higher in men with diabetes (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.22) than in women (HR 1.14; 95% CI, 1.12–1.16) compared with healthy controls, according to a paper published online July 27 in Diabetes Care.

Previous cardiovascular disease doubled the risk of dementia in patients with diabetes, while hospitalization or emergency department visits for hypoglycaemia were associated with a 73% increase in dementia risk. Patients with chronic kidney disease or prior vascular disease were at increased dementia risk (Diabetes Care 2015, July 27 [doi: 10.2337/dc15-0491]).

There was a 1% increase in the risk of dementia per year following the diagnosis of diabetes, such that patients who had had diabetes for 10 years had a nearly 30% higher incidence of dementia. The median age of the cohort was 73 years.

“This is of serious concern given the aging population, increasing prevalence of diabetes, and the limited effective treatment currently available for dementia,” the authors wrote.

They also found that many commonly used vascular and antidiabetic medications did not impact the risk of dementia, except statins and calcium-channel blockers.

“Although such treatments have been postulated to be protective against dementia, numerous trials have failed to identify any beneficial role of glucose-, blood pressure–, or lipid-lowering agents on cognitive decline, as suggested by previous observational data,” they noted.

Insulin use was associated with a 74% greater risk of developing dementia.

Recent immigrants or South Asian or Chinese ethnicity had a reduced risk of dementia, and hypertension also seemed to lower the risk by 5%.

The authors found that individuals with diabetes living in the lowest income areas were 17% more likely to develop dementia than were those in the wealthiest area.

“Impaired health literacy, poorer self-management, and adverse health behaviors, such as smoking, have been linked to low income and could explain this association,” reported Dr. Haroon and her coauthors.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the University of Toronto, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care supported the study. One author reported an unrestricted grant from Amgen, but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

A diagnosis of diabetes in later life is associated with an increased risk of dementia, particularly in individuals with preexisting vascular disease.

A population-based matched cohort study in 225,045 seniors newly diagnosed with diabetes and 668,070 without found a 16% higher risk of dementia among those with diabetes.

The association remained after adjustment for hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to a link between diabetes and dementia, with their shared cardiometabolic risk factors suggesting dementia may be yet another vascular complication of diabetes, wrote Dr. Nisha Nigil Haroon of the University of Toronto.

“We hypothesized that exposure to even short-term hyperglycemia in late life can trigger or accelerate cognitive decline and therefore that incident diabetes is a risk factor for dementia after accounting for differences in cardiovascular disease and other common risk factors,” wrote Dr. Haroon and her colleagues.

The risk of dementia was slightly higher in men with diabetes (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.22) than in women (HR 1.14; 95% CI, 1.12–1.16) compared with healthy controls, according to a paper published online July 27 in Diabetes Care.

Previous cardiovascular disease doubled the risk of dementia in patients with diabetes, while hospitalization or emergency department visits for hypoglycaemia were associated with a 73% increase in dementia risk. Patients with chronic kidney disease or prior vascular disease were at increased dementia risk (Diabetes Care 2015, July 27 [doi: 10.2337/dc15-0491]).

There was a 1% increase in the risk of dementia per year following the diagnosis of diabetes, such that patients who had had diabetes for 10 years had a nearly 30% higher incidence of dementia. The median age of the cohort was 73 years.

“This is of serious concern given the aging population, increasing prevalence of diabetes, and the limited effective treatment currently available for dementia,” the authors wrote.

They also found that many commonly used vascular and antidiabetic medications did not impact the risk of dementia, except statins and calcium-channel blockers.

“Although such treatments have been postulated to be protective against dementia, numerous trials have failed to identify any beneficial role of glucose-, blood pressure–, or lipid-lowering agents on cognitive decline, as suggested by previous observational data,” they noted.

Insulin use was associated with a 74% greater risk of developing dementia.

Recent immigrants or South Asian or Chinese ethnicity had a reduced risk of dementia, and hypertension also seemed to lower the risk by 5%.

The authors found that individuals with diabetes living in the lowest income areas were 17% more likely to develop dementia than were those in the wealthiest area.

“Impaired health literacy, poorer self-management, and adverse health behaviors, such as smoking, have been linked to low income and could explain this association,” reported Dr. Haroon and her coauthors.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the University of Toronto, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care supported the study. One author reported an unrestricted grant from Amgen, but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

A diagnosis of diabetes in later life is associated with an increased risk of dementia, particularly in individuals with preexisting vascular disease.

A population-based matched cohort study in 225,045 seniors newly diagnosed with diabetes and 668,070 without found a 16% higher risk of dementia among those with diabetes.

The association remained after adjustment for hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to a link between diabetes and dementia, with their shared cardiometabolic risk factors suggesting dementia may be yet another vascular complication of diabetes, wrote Dr. Nisha Nigil Haroon of the University of Toronto.

“We hypothesized that exposure to even short-term hyperglycemia in late life can trigger or accelerate cognitive decline and therefore that incident diabetes is a risk factor for dementia after accounting for differences in cardiovascular disease and other common risk factors,” wrote Dr. Haroon and her colleagues.

The risk of dementia was slightly higher in men with diabetes (hazard ratio, 1.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.22) than in women (HR 1.14; 95% CI, 1.12–1.16) compared with healthy controls, according to a paper published online July 27 in Diabetes Care.

Previous cardiovascular disease doubled the risk of dementia in patients with diabetes, while hospitalization or emergency department visits for hypoglycaemia were associated with a 73% increase in dementia risk. Patients with chronic kidney disease or prior vascular disease were at increased dementia risk (Diabetes Care 2015, July 27 [doi: 10.2337/dc15-0491]).

There was a 1% increase in the risk of dementia per year following the diagnosis of diabetes, such that patients who had had diabetes for 10 years had a nearly 30% higher incidence of dementia. The median age of the cohort was 73 years.

“This is of serious concern given the aging population, increasing prevalence of diabetes, and the limited effective treatment currently available for dementia,” the authors wrote.

They also found that many commonly used vascular and antidiabetic medications did not impact the risk of dementia, except statins and calcium-channel blockers.

“Although such treatments have been postulated to be protective against dementia, numerous trials have failed to identify any beneficial role of glucose-, blood pressure–, or lipid-lowering agents on cognitive decline, as suggested by previous observational data,” they noted.

Insulin use was associated with a 74% greater risk of developing dementia.

Recent immigrants or South Asian or Chinese ethnicity had a reduced risk of dementia, and hypertension also seemed to lower the risk by 5%.

The authors found that individuals with diabetes living in the lowest income areas were 17% more likely to develop dementia than were those in the wealthiest area.

“Impaired health literacy, poorer self-management, and adverse health behaviors, such as smoking, have been linked to low income and could explain this association,” reported Dr. Haroon and her coauthors.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the University of Toronto, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care supported the study. One author reported an unrestricted grant from Amgen, but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Key clinical point: Even short-term hyperglycemia in late life can trigger or accelerate cognitive decline and incident diabetes is a risk factor for dementia after adjustment for differences in cardiovascular disease and other common risk factors.

Major finding: Individuals diagnosed with diabetes later in life have a 16% higher risk of dementia than do those without diabetes.

Data source: A population-based matched cohort study in 225,045 seniors newly diagnosed with diabetes and 668,070 nondiabetic controls.

Disclosures: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the University of Toronto, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care supported the study. One author reported an unrestricted grant from Amgen, but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

Study: Most young adults with diabetes neglect eye exams

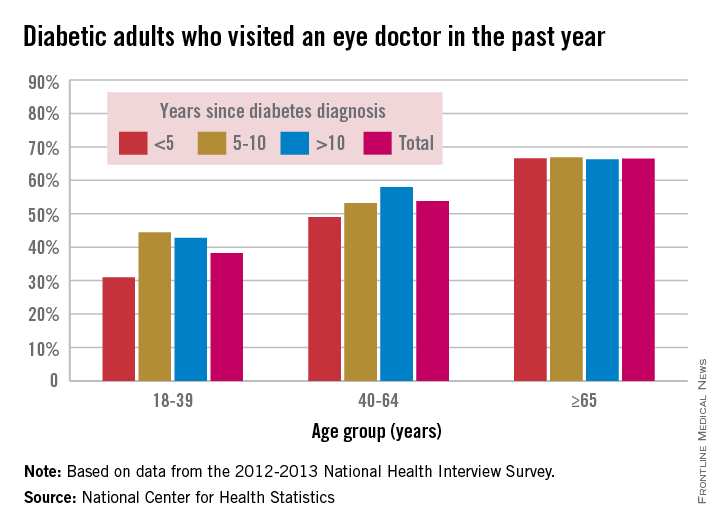

Adults younger than 40 years old who have diabetes were much less likely to have recently seen an eye doctor than were older adults during 2012-2013, especially if they had been diagnosed less than 5 years earlier, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among adults aged 18-39 years who had been diagnosed with diabetes in the previous 5 years, 31% had seen an eye doctor in the previous year, compared with 49% of adults aged 40-64 and about 67% of adults 65 and older. About 44% of 18- to 39-year-olds diagnosed 5-10 years earlier reported seeing an eye doctor recently, and just under 43% of 18- to 39-year olds diagnosed more than 10 years prior reported seeing an eye doctor in the past year, the researchers noted.

Adults aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed more than 10 years prior were significantly more likely to have seen an eye doctor recently (58%) than were those diagnosed between 5 and 10 years earlier (53%). In adults 65 and older, between 66% and 67% had seen an eye doctor recently in all diagnosis groups, according to the report.

“Among adults with diabetes, both age and years since diagnosis may play a role in visiting an eye doctor in the past 12 months. However, the findings here show that the association between years since diagnosis and visiting an eye doctor in the past year may only hold for certain age groups, specifically adults aged 40-64,” wrote the NCHS researchers.

The NCHS used data collected for the 2012-2013 National Health Interview Survey.

Adults younger than 40 years old who have diabetes were much less likely to have recently seen an eye doctor than were older adults during 2012-2013, especially if they had been diagnosed less than 5 years earlier, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among adults aged 18-39 years who had been diagnosed with diabetes in the previous 5 years, 31% had seen an eye doctor in the previous year, compared with 49% of adults aged 40-64 and about 67% of adults 65 and older. About 44% of 18- to 39-year-olds diagnosed 5-10 years earlier reported seeing an eye doctor recently, and just under 43% of 18- to 39-year olds diagnosed more than 10 years prior reported seeing an eye doctor in the past year, the researchers noted.

Adults aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed more than 10 years prior were significantly more likely to have seen an eye doctor recently (58%) than were those diagnosed between 5 and 10 years earlier (53%). In adults 65 and older, between 66% and 67% had seen an eye doctor recently in all diagnosis groups, according to the report.

“Among adults with diabetes, both age and years since diagnosis may play a role in visiting an eye doctor in the past 12 months. However, the findings here show that the association between years since diagnosis and visiting an eye doctor in the past year may only hold for certain age groups, specifically adults aged 40-64,” wrote the NCHS researchers.

The NCHS used data collected for the 2012-2013 National Health Interview Survey.

Adults younger than 40 years old who have diabetes were much less likely to have recently seen an eye doctor than were older adults during 2012-2013, especially if they had been diagnosed less than 5 years earlier, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among adults aged 18-39 years who had been diagnosed with diabetes in the previous 5 years, 31% had seen an eye doctor in the previous year, compared with 49% of adults aged 40-64 and about 67% of adults 65 and older. About 44% of 18- to 39-year-olds diagnosed 5-10 years earlier reported seeing an eye doctor recently, and just under 43% of 18- to 39-year olds diagnosed more than 10 years prior reported seeing an eye doctor in the past year, the researchers noted.

Adults aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed more than 10 years prior were significantly more likely to have seen an eye doctor recently (58%) than were those diagnosed between 5 and 10 years earlier (53%). In adults 65 and older, between 66% and 67% had seen an eye doctor recently in all diagnosis groups, according to the report.

“Among adults with diabetes, both age and years since diagnosis may play a role in visiting an eye doctor in the past 12 months. However, the findings here show that the association between years since diagnosis and visiting an eye doctor in the past year may only hold for certain age groups, specifically adults aged 40-64,” wrote the NCHS researchers.

The NCHS used data collected for the 2012-2013 National Health Interview Survey.

Fungal foot infections risk secondary infection in diabetic patients

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD 2015

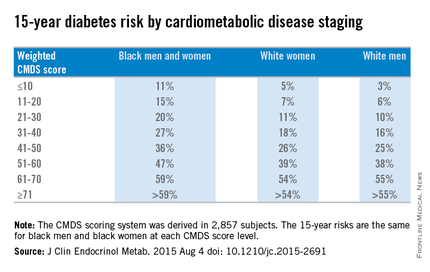

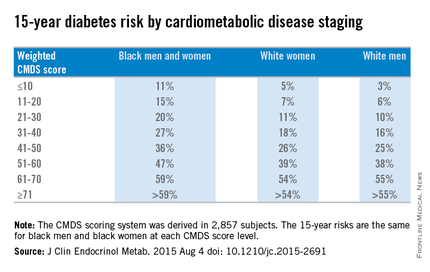

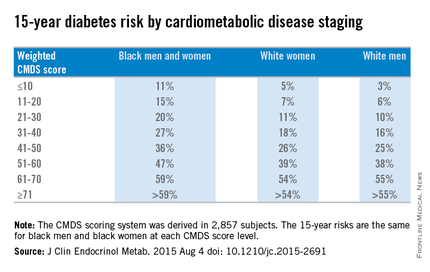

Weighted CMDS score predicts 15-year diabetes risk

A modified version of the cardiometabolic disease staging (CMDS) scoring system can be effectively used in a clinical setting to identify patients who are at an elevated risk for developing diabetes, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To enhance the application of the CMDS system in clinical settings, we sought to develop a weighted scoring system based on risk factor components in the CMDS system for the prediction of future diabetes by separate identification and weighting of those risk components,” said Dr. Fangjian Guo of the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, and Dr. W. Timothy Garvey of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

The CMDS scoring method involves these measures:

• Fasting blood glucose of at least 100 mg/dL.

• Two-hour glucose from oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of at least 140 mg/dL.

• Waist circumference of 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women.

• Blood pressure (systolic of at least 130 mm Hg and/or diastolic of at least 85 mm Hg) or use of antihypertensive medication.

• HDL cholesterol under 40 mg/dL in men and under 50 mg/dL in women.

• Fasting triglycerides of at least 150 mg/dL or use of antihyperlipidemia medication.

Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey used data from the CARDIA study and the ARIC study for their investigation.

CARDIA is a large, ongoing population study of 5,115 black and white adults, age 18-30 years, recruited from 1985 to 1986, with follow-up examinations conducted in seven visits over the next 25 years.

ARIC is an ongoing prospective cohort study of 15,792 men and women recruited at age 46-64 years in 1987 from either Mississippi, North Carolina, Minnesota, or Maryland, with follow-ups every 3 years.

The CMDS score was derived based on “verified incident diabetes cases from the CARDIA study” and was validated “in participants from the ARIC study,” after which the researchers “fitted Cox models and derived CMDS scores for diabetes accordingly,” the researchers wrote (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug 4 doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2691).

Overall, weighted diabetes CMDS scores were derived for 2,857 subjects and were validated in 6,425 subjects from the ARIC study. Scores in each of the six subcategories carried integer values that, when totaled, equaled a maximum of 100 per subject.

Weighted CMDS scores of 10 or lower were found to indicate a low 15-year risk of diabetes rate: 11% for both black men and women, 5% for white women, and 3% for white men. Weighted CMDS scores of 11-20 indicate a 15% risk for black men and women, 7% for white women, and 6% for white men. Scores of 21-30 indicated a 20% risk for black men and women, 11% for white women, and 10% for white men. Scores of 31-40 indicated a 27% risk for black men and women, 18% for white women, and 16% for white men. Scores of 41-50 indicated a 36% risk for black men and women, 26% for white women, and 25% for white men.

Fifteen-year diabetes-risk rates increased in the higher CMDS score brackets. In the 51-60 range, black men and women have a 47% risk, compared with 39% for white women and 38% for white men. Scores of 61-70 indicated a 59% risk for black men and women, 54% for white women, and 55% for white men. In the final score bracket of 71 and higher, the risk is greater than 59% for black men and women, greater than 54% for white women, and greater than 55% for white men.

“The main strength of this study is the development and validation of a weighted diabetes algorithm using data from two large prospective national cohorts,” Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey noted, adding that “incident diabetes in the CARDIA study was based on rigorous measures of fasting glucose and 2-hour OGTT glucose, such that the ascertained diabetes cases provide a solid basis for the development of our weighted CMDS scoring system.”

Limitations of the study include the fact that blood glucose measures were not available for ARIC participants after the fourth visit and that diabetes cases were based on hospital records and self-reports. Furthermore, both CARDIA and ARIC looked exclusively at black and white subjects, meaning that other minority groups – particularly Asians – were not included.

This study was supported by the merit review program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and the UAB Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Guo is supported by an institutional training grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development at the NIH.

A modified version of the cardiometabolic disease staging (CMDS) scoring system can be effectively used in a clinical setting to identify patients who are at an elevated risk for developing diabetes, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To enhance the application of the CMDS system in clinical settings, we sought to develop a weighted scoring system based on risk factor components in the CMDS system for the prediction of future diabetes by separate identification and weighting of those risk components,” said Dr. Fangjian Guo of the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, and Dr. W. Timothy Garvey of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

The CMDS scoring method involves these measures:

• Fasting blood glucose of at least 100 mg/dL.

• Two-hour glucose from oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of at least 140 mg/dL.

• Waist circumference of 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women.

• Blood pressure (systolic of at least 130 mm Hg and/or diastolic of at least 85 mm Hg) or use of antihypertensive medication.

• HDL cholesterol under 40 mg/dL in men and under 50 mg/dL in women.

• Fasting triglycerides of at least 150 mg/dL or use of antihyperlipidemia medication.

Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey used data from the CARDIA study and the ARIC study for their investigation.

CARDIA is a large, ongoing population study of 5,115 black and white adults, age 18-30 years, recruited from 1985 to 1986, with follow-up examinations conducted in seven visits over the next 25 years.

ARIC is an ongoing prospective cohort study of 15,792 men and women recruited at age 46-64 years in 1987 from either Mississippi, North Carolina, Minnesota, or Maryland, with follow-ups every 3 years.

The CMDS score was derived based on “verified incident diabetes cases from the CARDIA study” and was validated “in participants from the ARIC study,” after which the researchers “fitted Cox models and derived CMDS scores for diabetes accordingly,” the researchers wrote (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug 4 doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2691).

Overall, weighted diabetes CMDS scores were derived for 2,857 subjects and were validated in 6,425 subjects from the ARIC study. Scores in each of the six subcategories carried integer values that, when totaled, equaled a maximum of 100 per subject.

Weighted CMDS scores of 10 or lower were found to indicate a low 15-year risk of diabetes rate: 11% for both black men and women, 5% for white women, and 3% for white men. Weighted CMDS scores of 11-20 indicate a 15% risk for black men and women, 7% for white women, and 6% for white men. Scores of 21-30 indicated a 20% risk for black men and women, 11% for white women, and 10% for white men. Scores of 31-40 indicated a 27% risk for black men and women, 18% for white women, and 16% for white men. Scores of 41-50 indicated a 36% risk for black men and women, 26% for white women, and 25% for white men.

Fifteen-year diabetes-risk rates increased in the higher CMDS score brackets. In the 51-60 range, black men and women have a 47% risk, compared with 39% for white women and 38% for white men. Scores of 61-70 indicated a 59% risk for black men and women, 54% for white women, and 55% for white men. In the final score bracket of 71 and higher, the risk is greater than 59% for black men and women, greater than 54% for white women, and greater than 55% for white men.

“The main strength of this study is the development and validation of a weighted diabetes algorithm using data from two large prospective national cohorts,” Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey noted, adding that “incident diabetes in the CARDIA study was based on rigorous measures of fasting glucose and 2-hour OGTT glucose, such that the ascertained diabetes cases provide a solid basis for the development of our weighted CMDS scoring system.”

Limitations of the study include the fact that blood glucose measures were not available for ARIC participants after the fourth visit and that diabetes cases were based on hospital records and self-reports. Furthermore, both CARDIA and ARIC looked exclusively at black and white subjects, meaning that other minority groups – particularly Asians – were not included.

This study was supported by the merit review program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and the UAB Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Guo is supported by an institutional training grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development at the NIH.

A modified version of the cardiometabolic disease staging (CMDS) scoring system can be effectively used in a clinical setting to identify patients who are at an elevated risk for developing diabetes, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To enhance the application of the CMDS system in clinical settings, we sought to develop a weighted scoring system based on risk factor components in the CMDS system for the prediction of future diabetes by separate identification and weighting of those risk components,” said Dr. Fangjian Guo of the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, and Dr. W. Timothy Garvey of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

The CMDS scoring method involves these measures:

• Fasting blood glucose of at least 100 mg/dL.

• Two-hour glucose from oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of at least 140 mg/dL.

• Waist circumference of 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women.

• Blood pressure (systolic of at least 130 mm Hg and/or diastolic of at least 85 mm Hg) or use of antihypertensive medication.

• HDL cholesterol under 40 mg/dL in men and under 50 mg/dL in women.

• Fasting triglycerides of at least 150 mg/dL or use of antihyperlipidemia medication.

Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey used data from the CARDIA study and the ARIC study for their investigation.

CARDIA is a large, ongoing population study of 5,115 black and white adults, age 18-30 years, recruited from 1985 to 1986, with follow-up examinations conducted in seven visits over the next 25 years.

ARIC is an ongoing prospective cohort study of 15,792 men and women recruited at age 46-64 years in 1987 from either Mississippi, North Carolina, Minnesota, or Maryland, with follow-ups every 3 years.

The CMDS score was derived based on “verified incident diabetes cases from the CARDIA study” and was validated “in participants from the ARIC study,” after which the researchers “fitted Cox models and derived CMDS scores for diabetes accordingly,” the researchers wrote (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug 4 doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2691).

Overall, weighted diabetes CMDS scores were derived for 2,857 subjects and were validated in 6,425 subjects from the ARIC study. Scores in each of the six subcategories carried integer values that, when totaled, equaled a maximum of 100 per subject.

Weighted CMDS scores of 10 or lower were found to indicate a low 15-year risk of diabetes rate: 11% for both black men and women, 5% for white women, and 3% for white men. Weighted CMDS scores of 11-20 indicate a 15% risk for black men and women, 7% for white women, and 6% for white men. Scores of 21-30 indicated a 20% risk for black men and women, 11% for white women, and 10% for white men. Scores of 31-40 indicated a 27% risk for black men and women, 18% for white women, and 16% for white men. Scores of 41-50 indicated a 36% risk for black men and women, 26% for white women, and 25% for white men.

Fifteen-year diabetes-risk rates increased in the higher CMDS score brackets. In the 51-60 range, black men and women have a 47% risk, compared with 39% for white women and 38% for white men. Scores of 61-70 indicated a 59% risk for black men and women, 54% for white women, and 55% for white men. In the final score bracket of 71 and higher, the risk is greater than 59% for black men and women, greater than 54% for white women, and greater than 55% for white men.

“The main strength of this study is the development and validation of a weighted diabetes algorithm using data from two large prospective national cohorts,” Dr. Guo and Dr. Garvey noted, adding that “incident diabetes in the CARDIA study was based on rigorous measures of fasting glucose and 2-hour OGTT glucose, such that the ascertained diabetes cases provide a solid basis for the development of our weighted CMDS scoring system.”

Limitations of the study include the fact that blood glucose measures were not available for ARIC participants after the fourth visit and that diabetes cases were based on hospital records and self-reports. Furthermore, both CARDIA and ARIC looked exclusively at black and white subjects, meaning that other minority groups – particularly Asians – were not included.

This study was supported by the merit review program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and the UAB Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Guo is supported by an institutional training grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development at the NIH.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Key clinical point: The cardiometabolic disease staging (CMDS) scoring system can be used as an effective quantitative measure for predicting an individual’s chances of developing diabetes.

Major finding: CMDS scores that were adjusted according to age and race of each subject were more accurate in predicting risk of developing diabetes within 15 years; black men and women aged 61 years and older were most susceptible.

Data source: CARDIA, an ongoing population-based study of 5,115 black and white adults recruited during 1985-1986, and ARIC, an ongoing prospective cohort study of 15,792 men and women aged 45-64 years recruited in 1987.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the merit review program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and the UAB Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Guo is supported by an institutional training grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development at the NIH.

For diabetic patients, LRYGB safety comparable to other common procedures

CHICAGO – Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in diabetic patients has comparable short-term morbidity and mortality with other common surgical procedures and may circumvent the need for many of them, a NSQIP database analysis shows.

Thirty-day mortality for LRYGB was 3 per 1,000 patients, or approximately one-tenth that of coronary artery bypass graft (0.3% vs. 2.8%).

“This is significant to us moving forward from the point of meeting patients earlier on in their life and approaching the idea of bariatric surgery because the earlier intervention of bariatric surgery, which may have the chance of curing their diabetes, may eliminate the need for higher-risk procedures such as a cardiac bypass down the road,” study author Dr. Matthew Davis said at the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference.

Similarly, total knee arthroplasty had a complication rate nearly five times that of LRYGB (16.7% vs. 3.4%) and comparable mortality (both 0.3%).

“Being that morbid obesity, or obesity in general, is a significant risk factor for osteoarthritis, which is the number-one indication for total knee [arthroplasty], again, we can potentially perform one surgery to eliminate the need for a further surgery that does show to have a higher complication rate,” he said.

Five randomized controlled trials have shown the remarkable effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus, including better glycemic control, cardiovascular risk factor modification, and the potential for long-term remission. The safety profile of metabolic diabetes surgery, however, has been a matter of concern among patients and physicians, said Dr. Davis of the Bariatric & Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

To explore short-term metabolic diabetes surgery outcomes, the investigators used the American College of Surgeons’ NSQIP dataset to identify 16,509 diabetic patients who underwent LRYGB from January 2007 to December 2012 and compare them with patients undergoing seven other common surgical procedures: coronary artery bypass graft (n = 2,868), infrainguinal bypass (n = 10,454), laparoscopic partial colectomy (n = 5,511), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n = 15,306), laparoscopic appendectomy (n = 4,537), laparoscopic hysterectomy (n = 2,309), and total knee arthroplasty (n = 9,184).

Patients undergoing open or revisional bariatric surgery were excluded. Also excluded were sleeve gastrectomy cases because data were not available for the entire study period and gastric banding because its effect on diabetes is not as significant as gastric bypass, he said.

One-third (37.4%) of patients used insulin, 79% had hypertension, and 71.5% were women. The average body mass index was 46.5 kg/m2 and the average age was 50 years.

The 30-day composite complication rate was defined as the presence of any of nine postoperative adverse events: stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, septic shock, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, sepsis, and need for transfusion.

The most frequent adverse event with LRYGB was need for transfusion, which occurred in 1.22% of patients, Dr. Davis said. Rates for the other eight complications in ascending order were: stroke (0.05%), MI (0.16%), pulmonary embolism (0.22%), acute renal failure (0.22%), septic shock (0.30%), deep vein thrombosis (0.36%), pneumonia (0.66%), and sepsis (0.81%).

The 30-day complication rate for LRYGB was comparable with that for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (3.7%) and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Complication rates were significantly higher, however, for CABG (46.6%), infrainguinal bypass (23.6%), laparoscopic partial colectomy (12%), laparoscopic appendectomy (4.5%), and total knee arthroplasty (16.7%), according to Dr. Davis.

Among LRYGB patients, the mean length of stay was 2.6 days, and 6.7% were readmitted, 2.5% underwent reoperation, and 0.3% died.

In contrast, the average length of stay was 6 days for laparoscopic partial colectomy, with readmission, reoperation, and mortality rates of 9.4%, 3.8%, and 1.8%, respectively.

“Compared with laparoscopic colectomy, gastric bypass superseded in all categories with morbidity and mortality,” he said.

Limitations of the study were the lack of information on sleeve gastrectomy and long-term safety outcomes, and nonsimilar baseline characteristics for comparator groups.

Session comoderator Dr. Konstantin Umanskiy of the University of Chicago said that the results highlight the dramatic improvements achieved in bariatric surgery through centers of excellence and could serve to invigorate efforts to bring this model to colorectal surgery. An initiative by the 144-member Consortium for Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRICH) to establish a U.S. Rectal Cancer Centers of Excellence program was endorsed last year by the American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer.

The investigators and Dr. Umanskiy reported having no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in diabetic patients has comparable short-term morbidity and mortality with other common surgical procedures and may circumvent the need for many of them, a NSQIP database analysis shows.

Thirty-day mortality for LRYGB was 3 per 1,000 patients, or approximately one-tenth that of coronary artery bypass graft (0.3% vs. 2.8%).

“This is significant to us moving forward from the point of meeting patients earlier on in their life and approaching the idea of bariatric surgery because the earlier intervention of bariatric surgery, which may have the chance of curing their diabetes, may eliminate the need for higher-risk procedures such as a cardiac bypass down the road,” study author Dr. Matthew Davis said at the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference.

Similarly, total knee arthroplasty had a complication rate nearly five times that of LRYGB (16.7% vs. 3.4%) and comparable mortality (both 0.3%).

“Being that morbid obesity, or obesity in general, is a significant risk factor for osteoarthritis, which is the number-one indication for total knee [arthroplasty], again, we can potentially perform one surgery to eliminate the need for a further surgery that does show to have a higher complication rate,” he said.

Five randomized controlled trials have shown the remarkable effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus, including better glycemic control, cardiovascular risk factor modification, and the potential for long-term remission. The safety profile of metabolic diabetes surgery, however, has been a matter of concern among patients and physicians, said Dr. Davis of the Bariatric & Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

To explore short-term metabolic diabetes surgery outcomes, the investigators used the American College of Surgeons’ NSQIP dataset to identify 16,509 diabetic patients who underwent LRYGB from January 2007 to December 2012 and compare them with patients undergoing seven other common surgical procedures: coronary artery bypass graft (n = 2,868), infrainguinal bypass (n = 10,454), laparoscopic partial colectomy (n = 5,511), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n = 15,306), laparoscopic appendectomy (n = 4,537), laparoscopic hysterectomy (n = 2,309), and total knee arthroplasty (n = 9,184).

Patients undergoing open or revisional bariatric surgery were excluded. Also excluded were sleeve gastrectomy cases because data were not available for the entire study period and gastric banding because its effect on diabetes is not as significant as gastric bypass, he said.

One-third (37.4%) of patients used insulin, 79% had hypertension, and 71.5% were women. The average body mass index was 46.5 kg/m2 and the average age was 50 years.

The 30-day composite complication rate was defined as the presence of any of nine postoperative adverse events: stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, septic shock, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, sepsis, and need for transfusion.

The most frequent adverse event with LRYGB was need for transfusion, which occurred in 1.22% of patients, Dr. Davis said. Rates for the other eight complications in ascending order were: stroke (0.05%), MI (0.16%), pulmonary embolism (0.22%), acute renal failure (0.22%), septic shock (0.30%), deep vein thrombosis (0.36%), pneumonia (0.66%), and sepsis (0.81%).

The 30-day complication rate for LRYGB was comparable with that for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (3.7%) and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Complication rates were significantly higher, however, for CABG (46.6%), infrainguinal bypass (23.6%), laparoscopic partial colectomy (12%), laparoscopic appendectomy (4.5%), and total knee arthroplasty (16.7%), according to Dr. Davis.

Among LRYGB patients, the mean length of stay was 2.6 days, and 6.7% were readmitted, 2.5% underwent reoperation, and 0.3% died.

In contrast, the average length of stay was 6 days for laparoscopic partial colectomy, with readmission, reoperation, and mortality rates of 9.4%, 3.8%, and 1.8%, respectively.

“Compared with laparoscopic colectomy, gastric bypass superseded in all categories with morbidity and mortality,” he said.

Limitations of the study were the lack of information on sleeve gastrectomy and long-term safety outcomes, and nonsimilar baseline characteristics for comparator groups.

Session comoderator Dr. Konstantin Umanskiy of the University of Chicago said that the results highlight the dramatic improvements achieved in bariatric surgery through centers of excellence and could serve to invigorate efforts to bring this model to colorectal surgery. An initiative by the 144-member Consortium for Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRICH) to establish a U.S. Rectal Cancer Centers of Excellence program was endorsed last year by the American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer.

The investigators and Dr. Umanskiy reported having no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in diabetic patients has comparable short-term morbidity and mortality with other common surgical procedures and may circumvent the need for many of them, a NSQIP database analysis shows.

Thirty-day mortality for LRYGB was 3 per 1,000 patients, or approximately one-tenth that of coronary artery bypass graft (0.3% vs. 2.8%).

“This is significant to us moving forward from the point of meeting patients earlier on in their life and approaching the idea of bariatric surgery because the earlier intervention of bariatric surgery, which may have the chance of curing their diabetes, may eliminate the need for higher-risk procedures such as a cardiac bypass down the road,” study author Dr. Matthew Davis said at the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference.

Similarly, total knee arthroplasty had a complication rate nearly five times that of LRYGB (16.7% vs. 3.4%) and comparable mortality (both 0.3%).

“Being that morbid obesity, or obesity in general, is a significant risk factor for osteoarthritis, which is the number-one indication for total knee [arthroplasty], again, we can potentially perform one surgery to eliminate the need for a further surgery that does show to have a higher complication rate,” he said.

Five randomized controlled trials have shown the remarkable effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus, including better glycemic control, cardiovascular risk factor modification, and the potential for long-term remission. The safety profile of metabolic diabetes surgery, however, has been a matter of concern among patients and physicians, said Dr. Davis of the Bariatric & Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

To explore short-term metabolic diabetes surgery outcomes, the investigators used the American College of Surgeons’ NSQIP dataset to identify 16,509 diabetic patients who underwent LRYGB from January 2007 to December 2012 and compare them with patients undergoing seven other common surgical procedures: coronary artery bypass graft (n = 2,868), infrainguinal bypass (n = 10,454), laparoscopic partial colectomy (n = 5,511), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n = 15,306), laparoscopic appendectomy (n = 4,537), laparoscopic hysterectomy (n = 2,309), and total knee arthroplasty (n = 9,184).

Patients undergoing open or revisional bariatric surgery were excluded. Also excluded were sleeve gastrectomy cases because data were not available for the entire study period and gastric banding because its effect on diabetes is not as significant as gastric bypass, he said.

One-third (37.4%) of patients used insulin, 79% had hypertension, and 71.5% were women. The average body mass index was 46.5 kg/m2 and the average age was 50 years.

The 30-day composite complication rate was defined as the presence of any of nine postoperative adverse events: stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, septic shock, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, sepsis, and need for transfusion.

The most frequent adverse event with LRYGB was need for transfusion, which occurred in 1.22% of patients, Dr. Davis said. Rates for the other eight complications in ascending order were: stroke (0.05%), MI (0.16%), pulmonary embolism (0.22%), acute renal failure (0.22%), septic shock (0.30%), deep vein thrombosis (0.36%), pneumonia (0.66%), and sepsis (0.81%).

The 30-day complication rate for LRYGB was comparable with that for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (3.7%) and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Complication rates were significantly higher, however, for CABG (46.6%), infrainguinal bypass (23.6%), laparoscopic partial colectomy (12%), laparoscopic appendectomy (4.5%), and total knee arthroplasty (16.7%), according to Dr. Davis.

Among LRYGB patients, the mean length of stay was 2.6 days, and 6.7% were readmitted, 2.5% underwent reoperation, and 0.3% died.

In contrast, the average length of stay was 6 days for laparoscopic partial colectomy, with readmission, reoperation, and mortality rates of 9.4%, 3.8%, and 1.8%, respectively.

“Compared with laparoscopic colectomy, gastric bypass superseded in all categories with morbidity and mortality,” he said.

Limitations of the study were the lack of information on sleeve gastrectomy and long-term safety outcomes, and nonsimilar baseline characteristics for comparator groups.

Session comoderator Dr. Konstantin Umanskiy of the University of Chicago said that the results highlight the dramatic improvements achieved in bariatric surgery through centers of excellence and could serve to invigorate efforts to bring this model to colorectal surgery. An initiative by the 144-member Consortium for Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRICH) to establish a U.S. Rectal Cancer Centers of Excellence program was endorsed last year by the American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer.

The investigators and Dr. Umanskiy reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ACS NSQIP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with diabetes is as safe as other common procedures.

Major finding: At 30 days, LRYGB mortality was 0.3% and the composite complication rate was 3.4%.

Data source: Retrospective study in 16,509 diabetic patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 50,169 patients who had other surgical procedures.

Disclosures: The investigators and Dr. Umanskiy reported having no conflicts of interest.

Skipping breakfast incites hyperglycemic response in type 2 diabetes patients

When type 2 diabetes patients skipped breakfast, they had higher levels of glucagon and free fatty acids (FFA), and reduced levels of insulin, C-peptide, and intact glucagonlike peptide-1 (iGLP-1) after meals, compared with when they ate breakfast, according to a randomized, open-label, cross-over-within-subject clinical trial.

A total of 22 overweight or obese people who had type 2 diabetes completed the study. Patients could not be taking GLP-1 analogs, anorectic drugs, steroids, or oral hypoglycemic agents, other than metformin. Seven of the patients had a history of hypertension and were treated with ACE inhibitors and/or calcium antagonists, wrote Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz of the Diabetes Unit in Hospital de Clinicas in Caracas, Venezuela.

At the Diabetes Unit, the patients participated in 2 full days of testing, separated by a washout period of 2-4 weeks. On one of the days, patients consumed three meals, including breakfast. On the other testing day, patients fasted until 1:30 p.m., consuming only lunch and dinner. All patients ate each of their meals during the same scheduled times; all meals contained identical macronutrient content and composition.

Areas under the curve of data values for tested measures during an early response interval (0-30 minutes after eating a meal) and 0-180 minutes after eating a meal were calculated by the trapezoidal rule. These calculations were used as an estimate of response to meal consumption.

Plasma levels for glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and iGLP-1 were, respectively, 16.5%, 45%, 50%, and 33% higher before lunch, on the day that patients consumed breakfast, than they were on the day that they skipped breakfast.

The plasma FFA level was 1,787.1% higher for study participants on the day when they fasted until lunch than it was on the day when they ate breakfast. During tests taken 60-180 minutes after consumption of breakfast, patients’ glucagon levels were 12.5% lower than those of patients who fasted before lunch.

On the day that patients skipped breakfast, insulin was 17% lower after lunch and 7.9% lower after dinner, compared with the amounts of insulin found on the day that patients ate breakfast; iGLP-1 was also lower after dinner (16.5%) on the day that patients skipped breakfast.

After lunch and dinner, glucagon levels were 9.7% and 11.5% higher, respectively, on the day that patients refrained from eating breakfast than on the day that patients ate breakfast. Following lunch and dinner on the day that patients skipped breakfast, FFA values were higher (41.1% and 29.6%, respectively).

“We showed that the deleterious effects of breakfast omission triggering hyperglycemic response occurred after lunch and dinner, but the exact duration of this effect is not known,” wrote Dr. Jakubowicz and her colleagues. “In addition, the role of insulin sensitivity, suppression of hepatic glucose production, gastric emptying, and clock gene expression remain undefined.”

Read the full study in Diabetes Care (doi:10.2337/dc15-0761).

When type 2 diabetes patients skipped breakfast, they had higher levels of glucagon and free fatty acids (FFA), and reduced levels of insulin, C-peptide, and intact glucagonlike peptide-1 (iGLP-1) after meals, compared with when they ate breakfast, according to a randomized, open-label, cross-over-within-subject clinical trial.

A total of 22 overweight or obese people who had type 2 diabetes completed the study. Patients could not be taking GLP-1 analogs, anorectic drugs, steroids, or oral hypoglycemic agents, other than metformin. Seven of the patients had a history of hypertension and were treated with ACE inhibitors and/or calcium antagonists, wrote Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz of the Diabetes Unit in Hospital de Clinicas in Caracas, Venezuela.

At the Diabetes Unit, the patients participated in 2 full days of testing, separated by a washout period of 2-4 weeks. On one of the days, patients consumed three meals, including breakfast. On the other testing day, patients fasted until 1:30 p.m., consuming only lunch and dinner. All patients ate each of their meals during the same scheduled times; all meals contained identical macronutrient content and composition.

Areas under the curve of data values for tested measures during an early response interval (0-30 minutes after eating a meal) and 0-180 minutes after eating a meal were calculated by the trapezoidal rule. These calculations were used as an estimate of response to meal consumption.

Plasma levels for glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and iGLP-1 were, respectively, 16.5%, 45%, 50%, and 33% higher before lunch, on the day that patients consumed breakfast, than they were on the day that they skipped breakfast.

The plasma FFA level was 1,787.1% higher for study participants on the day when they fasted until lunch than it was on the day when they ate breakfast. During tests taken 60-180 minutes after consumption of breakfast, patients’ glucagon levels were 12.5% lower than those of patients who fasted before lunch.

On the day that patients skipped breakfast, insulin was 17% lower after lunch and 7.9% lower after dinner, compared with the amounts of insulin found on the day that patients ate breakfast; iGLP-1 was also lower after dinner (16.5%) on the day that patients skipped breakfast.

After lunch and dinner, glucagon levels were 9.7% and 11.5% higher, respectively, on the day that patients refrained from eating breakfast than on the day that patients ate breakfast. Following lunch and dinner on the day that patients skipped breakfast, FFA values were higher (41.1% and 29.6%, respectively).

“We showed that the deleterious effects of breakfast omission triggering hyperglycemic response occurred after lunch and dinner, but the exact duration of this effect is not known,” wrote Dr. Jakubowicz and her colleagues. “In addition, the role of insulin sensitivity, suppression of hepatic glucose production, gastric emptying, and clock gene expression remain undefined.”

Read the full study in Diabetes Care (doi:10.2337/dc15-0761).

When type 2 diabetes patients skipped breakfast, they had higher levels of glucagon and free fatty acids (FFA), and reduced levels of insulin, C-peptide, and intact glucagonlike peptide-1 (iGLP-1) after meals, compared with when they ate breakfast, according to a randomized, open-label, cross-over-within-subject clinical trial.

A total of 22 overweight or obese people who had type 2 diabetes completed the study. Patients could not be taking GLP-1 analogs, anorectic drugs, steroids, or oral hypoglycemic agents, other than metformin. Seven of the patients had a history of hypertension and were treated with ACE inhibitors and/or calcium antagonists, wrote Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz of the Diabetes Unit in Hospital de Clinicas in Caracas, Venezuela.

At the Diabetes Unit, the patients participated in 2 full days of testing, separated by a washout period of 2-4 weeks. On one of the days, patients consumed three meals, including breakfast. On the other testing day, patients fasted until 1:30 p.m., consuming only lunch and dinner. All patients ate each of their meals during the same scheduled times; all meals contained identical macronutrient content and composition.

Areas under the curve of data values for tested measures during an early response interval (0-30 minutes after eating a meal) and 0-180 minutes after eating a meal were calculated by the trapezoidal rule. These calculations were used as an estimate of response to meal consumption.