User login

EMERGENCY MEDICINE is a practical, peer-reviewed monthly publication and Web site that meets the educational needs of emergency clinicians and urgent care clinicians for their practice.

Troponins touted as ‘ally’ in COVID-19 triage, but message is nuanced

, cardiologists in the United Kingdom advise in a recently published viewpoint.

The tests can be used to “inform the triage of patients to critical care, guide the use of supportive treatments, and facilitate targeted cardiac investigations in those most likely to benefit,” Nicholas Mills, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. He is senior author on the viewpoint published online April 6 in the journal Circulation.

Older adults and those with a history of underlying cardiovascular disease appear to be at greatest risk of dying from COVID-19. “From early reports it is clear that elevated cardiac troponin concentrations predict in-hospital mortality,” said Mills.

In a recent report on hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, for example, cardiac injury (hs-cTn above the 99th-percentile upper reference limit) was seen in 1 in 5 patients and was an independent predictor of dying in the hospital. Mortality was 10-fold higher in those with cardiac injury on presentation.

Elevated cardiac troponin in the setting of COVID-19, Mills said, “may reflect illness severity with myocardial injury arising due to myocardial oxygen supply–demand imbalance. Or it may be due to direct cardiac involvement through viral myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy, or where the prothrombotic and proinflammatory state is precipitating acute coronary syndromes.”

In their viewpoint, the authors note that circulating cTn is a marker of myocardial injury, “including but not limited to myocardial infarction or myocarditis, and the clinical relevance of this distinction has never been so clear.”

Therefore, the consequence of not measuring cardiac troponin may be to “ignore the plethora of ischemic and nonischemic causes” of myocardial injury related to COVID-19. “Clinicians who have used troponin measurement as a binary test for myocardial infarction independent of clinical context and those who consider an elevated cardiac troponin concentration to be a mandate for invasive coronary angiography must recalibrate,” they write.

“Rather than encouraging avoidance of troponin testing, we must harness the unheralded engagement from the cardiovascular community due to COVID-19 to better understand the utility of this essential biomarker and to educate clinicians on its interpretation and implications for prognosis and clinical decision making.”

Based on “same logic” as recent ACC guidance

The viewpoint was to some extent a response to a recent informal guidance from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that advised caution in use of troponin and natriuretic peptide tests in patients with COVID-19.

Even so, that ACC guidance and the new viewpoint in Circulation are based on the “same logic,” James Januzzi Jr, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. Both documents:

- Point out that troponins are frequently abnormal in patients with severe cases of COVID-19

- Caution that clinicians should not equate an abnormal hs-cTn with acute myocardial infarction

- Note that, in most cases, hs-cTn elevations are a result of noncoronary mechanisms

- Recognize the potential risk to caregivers and the continued unchecked spread of SARS-CoV-2 related to downstream testing that might not be needed

“The Circulation opinion piece states that clinicians often use troponin as a binary test for myocardial infarction and a mandate for downstream testing, suggesting clinicians will need to recalibrate that approach, something I agree with and which is the central message of the ACC position,” Januzzi said.

Probably the biggest difference between the two documents, he said, is in the Circulation authors’ apparent enthusiasm to use hs-cTn as a tool to judge disease severity in patients with COVID-19.

It’s been known for more than a decade that myocardial injury is “an important risk predictor” in critical illness, Januzzi explained. “So the link between cardiac injury and outcomes in critical illness is nothing new. The difference is the fact we are seeing so many patients with COVID-19 all at once, and the authors suggest that using troponin might help in triage decision making.”

“There may be [such] a role here, but the data have not been systematically collected, and whether troponin truly adds something beyond information already available at the bedside — for example, does it add anything not already obvious at the bedside? — has not yet been conclusively proven,” Januzzi cautioned.

“As well, there are no prospective data supporting troponin as a trigger for ICU triage or for deciding on specific treatments.”

Positive cTn status “common” in COVID-19 patients

In his experience, Barry Cohen, MD, Morristown Medical Center, New Jersey, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, that positive cTn status is “common in COVID-19 patients and appears to have prognostic value, not only in type 1 MI due to atherothrombotic disease (related to a proinflammatory and prothrombotic state), but more frequently type 2 MI (supply–demand mismatch), viral myocarditis, coronary microvascular ischemia, stress cardiomyopathy or tachyarrhythmias.”

Moreover, Cohen said, hs-cTn “has identified patients at increased risk for ventilation support (invasive and noninvasive), acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, and mortality.”

Echoing both the ACC document and the Circulation report, Cohen also said hs-cTn measurements “appear to help risk stratify COVID-19 patients, but clearly do not mean that a troponin-positive patient needs to go to the cath lab and be treated as having acute coronary syndrome. Only a minority of these patients require this intervention.”

Mills discloses receiving honoraria from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens Healthineers, and LumiraDx. Januzzi has previously disclosed receiving personal fees from the American College of Cardiology, Pfizer, Merck, AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; grants and personal fees from Novartis, Roche, Abbott, and Janssen; and grants from Singulex and Prevencio. Cohen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, cardiologists in the United Kingdom advise in a recently published viewpoint.

The tests can be used to “inform the triage of patients to critical care, guide the use of supportive treatments, and facilitate targeted cardiac investigations in those most likely to benefit,” Nicholas Mills, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. He is senior author on the viewpoint published online April 6 in the journal Circulation.

Older adults and those with a history of underlying cardiovascular disease appear to be at greatest risk of dying from COVID-19. “From early reports it is clear that elevated cardiac troponin concentrations predict in-hospital mortality,” said Mills.

In a recent report on hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, for example, cardiac injury (hs-cTn above the 99th-percentile upper reference limit) was seen in 1 in 5 patients and was an independent predictor of dying in the hospital. Mortality was 10-fold higher in those with cardiac injury on presentation.

Elevated cardiac troponin in the setting of COVID-19, Mills said, “may reflect illness severity with myocardial injury arising due to myocardial oxygen supply–demand imbalance. Or it may be due to direct cardiac involvement through viral myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy, or where the prothrombotic and proinflammatory state is precipitating acute coronary syndromes.”

In their viewpoint, the authors note that circulating cTn is a marker of myocardial injury, “including but not limited to myocardial infarction or myocarditis, and the clinical relevance of this distinction has never been so clear.”

Therefore, the consequence of not measuring cardiac troponin may be to “ignore the plethora of ischemic and nonischemic causes” of myocardial injury related to COVID-19. “Clinicians who have used troponin measurement as a binary test for myocardial infarction independent of clinical context and those who consider an elevated cardiac troponin concentration to be a mandate for invasive coronary angiography must recalibrate,” they write.

“Rather than encouraging avoidance of troponin testing, we must harness the unheralded engagement from the cardiovascular community due to COVID-19 to better understand the utility of this essential biomarker and to educate clinicians on its interpretation and implications for prognosis and clinical decision making.”

Based on “same logic” as recent ACC guidance

The viewpoint was to some extent a response to a recent informal guidance from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that advised caution in use of troponin and natriuretic peptide tests in patients with COVID-19.

Even so, that ACC guidance and the new viewpoint in Circulation are based on the “same logic,” James Januzzi Jr, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. Both documents:

- Point out that troponins are frequently abnormal in patients with severe cases of COVID-19

- Caution that clinicians should not equate an abnormal hs-cTn with acute myocardial infarction

- Note that, in most cases, hs-cTn elevations are a result of noncoronary mechanisms

- Recognize the potential risk to caregivers and the continued unchecked spread of SARS-CoV-2 related to downstream testing that might not be needed

“The Circulation opinion piece states that clinicians often use troponin as a binary test for myocardial infarction and a mandate for downstream testing, suggesting clinicians will need to recalibrate that approach, something I agree with and which is the central message of the ACC position,” Januzzi said.

Probably the biggest difference between the two documents, he said, is in the Circulation authors’ apparent enthusiasm to use hs-cTn as a tool to judge disease severity in patients with COVID-19.

It’s been known for more than a decade that myocardial injury is “an important risk predictor” in critical illness, Januzzi explained. “So the link between cardiac injury and outcomes in critical illness is nothing new. The difference is the fact we are seeing so many patients with COVID-19 all at once, and the authors suggest that using troponin might help in triage decision making.”

“There may be [such] a role here, but the data have not been systematically collected, and whether troponin truly adds something beyond information already available at the bedside — for example, does it add anything not already obvious at the bedside? — has not yet been conclusively proven,” Januzzi cautioned.

“As well, there are no prospective data supporting troponin as a trigger for ICU triage or for deciding on specific treatments.”

Positive cTn status “common” in COVID-19 patients

In his experience, Barry Cohen, MD, Morristown Medical Center, New Jersey, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, that positive cTn status is “common in COVID-19 patients and appears to have prognostic value, not only in type 1 MI due to atherothrombotic disease (related to a proinflammatory and prothrombotic state), but more frequently type 2 MI (supply–demand mismatch), viral myocarditis, coronary microvascular ischemia, stress cardiomyopathy or tachyarrhythmias.”

Moreover, Cohen said, hs-cTn “has identified patients at increased risk for ventilation support (invasive and noninvasive), acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, and mortality.”

Echoing both the ACC document and the Circulation report, Cohen also said hs-cTn measurements “appear to help risk stratify COVID-19 patients, but clearly do not mean that a troponin-positive patient needs to go to the cath lab and be treated as having acute coronary syndrome. Only a minority of these patients require this intervention.”

Mills discloses receiving honoraria from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens Healthineers, and LumiraDx. Januzzi has previously disclosed receiving personal fees from the American College of Cardiology, Pfizer, Merck, AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; grants and personal fees from Novartis, Roche, Abbott, and Janssen; and grants from Singulex and Prevencio. Cohen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, cardiologists in the United Kingdom advise in a recently published viewpoint.

The tests can be used to “inform the triage of patients to critical care, guide the use of supportive treatments, and facilitate targeted cardiac investigations in those most likely to benefit,” Nicholas Mills, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. He is senior author on the viewpoint published online April 6 in the journal Circulation.

Older adults and those with a history of underlying cardiovascular disease appear to be at greatest risk of dying from COVID-19. “From early reports it is clear that elevated cardiac troponin concentrations predict in-hospital mortality,” said Mills.

In a recent report on hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, for example, cardiac injury (hs-cTn above the 99th-percentile upper reference limit) was seen in 1 in 5 patients and was an independent predictor of dying in the hospital. Mortality was 10-fold higher in those with cardiac injury on presentation.

Elevated cardiac troponin in the setting of COVID-19, Mills said, “may reflect illness severity with myocardial injury arising due to myocardial oxygen supply–demand imbalance. Or it may be due to direct cardiac involvement through viral myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy, or where the prothrombotic and proinflammatory state is precipitating acute coronary syndromes.”

In their viewpoint, the authors note that circulating cTn is a marker of myocardial injury, “including but not limited to myocardial infarction or myocarditis, and the clinical relevance of this distinction has never been so clear.”

Therefore, the consequence of not measuring cardiac troponin may be to “ignore the plethora of ischemic and nonischemic causes” of myocardial injury related to COVID-19. “Clinicians who have used troponin measurement as a binary test for myocardial infarction independent of clinical context and those who consider an elevated cardiac troponin concentration to be a mandate for invasive coronary angiography must recalibrate,” they write.

“Rather than encouraging avoidance of troponin testing, we must harness the unheralded engagement from the cardiovascular community due to COVID-19 to better understand the utility of this essential biomarker and to educate clinicians on its interpretation and implications for prognosis and clinical decision making.”

Based on “same logic” as recent ACC guidance

The viewpoint was to some extent a response to a recent informal guidance from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that advised caution in use of troponin and natriuretic peptide tests in patients with COVID-19.

Even so, that ACC guidance and the new viewpoint in Circulation are based on the “same logic,” James Januzzi Jr, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. Both documents:

- Point out that troponins are frequently abnormal in patients with severe cases of COVID-19

- Caution that clinicians should not equate an abnormal hs-cTn with acute myocardial infarction

- Note that, in most cases, hs-cTn elevations are a result of noncoronary mechanisms

- Recognize the potential risk to caregivers and the continued unchecked spread of SARS-CoV-2 related to downstream testing that might not be needed

“The Circulation opinion piece states that clinicians often use troponin as a binary test for myocardial infarction and a mandate for downstream testing, suggesting clinicians will need to recalibrate that approach, something I agree with and which is the central message of the ACC position,” Januzzi said.

Probably the biggest difference between the two documents, he said, is in the Circulation authors’ apparent enthusiasm to use hs-cTn as a tool to judge disease severity in patients with COVID-19.

It’s been known for more than a decade that myocardial injury is “an important risk predictor” in critical illness, Januzzi explained. “So the link between cardiac injury and outcomes in critical illness is nothing new. The difference is the fact we are seeing so many patients with COVID-19 all at once, and the authors suggest that using troponin might help in triage decision making.”

“There may be [such] a role here, but the data have not been systematically collected, and whether troponin truly adds something beyond information already available at the bedside — for example, does it add anything not already obvious at the bedside? — has not yet been conclusively proven,” Januzzi cautioned.

“As well, there are no prospective data supporting troponin as a trigger for ICU triage or for deciding on specific treatments.”

Positive cTn status “common” in COVID-19 patients

In his experience, Barry Cohen, MD, Morristown Medical Center, New Jersey, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, that positive cTn status is “common in COVID-19 patients and appears to have prognostic value, not only in type 1 MI due to atherothrombotic disease (related to a proinflammatory and prothrombotic state), but more frequently type 2 MI (supply–demand mismatch), viral myocarditis, coronary microvascular ischemia, stress cardiomyopathy or tachyarrhythmias.”

Moreover, Cohen said, hs-cTn “has identified patients at increased risk for ventilation support (invasive and noninvasive), acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, and mortality.”

Echoing both the ACC document and the Circulation report, Cohen also said hs-cTn measurements “appear to help risk stratify COVID-19 patients, but clearly do not mean that a troponin-positive patient needs to go to the cath lab and be treated as having acute coronary syndrome. Only a minority of these patients require this intervention.”

Mills discloses receiving honoraria from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche Diagnostics, Siemens Healthineers, and LumiraDx. Januzzi has previously disclosed receiving personal fees from the American College of Cardiology, Pfizer, Merck, AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; grants and personal fees from Novartis, Roche, Abbott, and Janssen; and grants from Singulex and Prevencio. Cohen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID 19: Confessions of an outpatient psychiatrist during the pandemic

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

TWILIGHT-COMPLEX: Tap ticagrelor monotherapy early after complex PCI

Patients who underwent complex PCI for acute coronary syndrome followed by 3 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor plus aspirin fared significantly better by dropping aspirin at that point in favor of long-term ticagrelor monotherapy than with continued dual-antiplatelet therapy in the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study.

The rate of clinically relevant bleeding was significantly lower at 12 months of follow-up in the ticagrelor monotherapy group than it was in patients randomized to continued DAPT. Moreover, this major benefit came at no cost in terms of ischemic events, which were actually numerically less frequent in the ticagrelor plus placebo group, George D. Dangas, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“We found that the aspirin just doesn’t add that much, even in complex patients – just bleeding complications, for the most part,” explained Dr. Dangas, professor of medicine and of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was a secondary post hoc analysis of outcomes in 2,342 participants in the previously reported larger parent TWILIGHT randomized trial who underwent complex PCI. The main TWILIGHT trial included 7,119 patients in 11 countries who underwent PCI for acute coronary syndrome, successfully completed 3 months of DAPT with ticagrelor plus aspirin without incident, and were then randomized double blind to 12 months of ticagrelor plus placebo or to another 12 months of ticagrelor and aspirin.

In the overall TWILIGHT trial, ticagrelor alone resulted in a significantly lower clinically relevant bleeding rate than did long-term ticagrelor plus aspirin, with no increase in the risk of death, MI, or stroke (N Engl J Med 2019; 381:2032-42). But the results left many interventional cardiologists wondering if a ticagrelor monotherapy strategy was really applicable to their more challenging patients undergoing complex PCI given that the risk of ischemic events is known to climb with PCI complexity. The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was specifically designed to address that concern.

To be eligible for TWILIGHT-COMPLEX, patients had to meet one or more prespecified angiographic or procedural criteria for complex PCI, such as a total stent length in excess of 60 mm, three or more treated lesions, use of an atherectomy device, or PCI of a left main lesion, a chronic total occlusion, or a bifurcation lesion with two stents. These complex PCI patients accounted for one-third of the total study population in TWILIGHT; 36% of them met more than one criteria for complex PCI.

TWILIGHT-COMPLEX findings

In the 12 months after randomization, patients who received ticagrelor plus placebo had a 4.2% incidence of clinically significant Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding, which was significantly lower than the 7.7% rate in the group on long-term DAPT and represented a 46% relative risk reduction. Severe or fatal bleeding – that is, BARC type 3 or 5 – occurred in 1.1% of those on ticagrelor monotherapy and 2.6% of the DAPT group, for a significant 59% relative risk reduction.

The composite ischemic endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke occurred in 3.6% of the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 4.8% of patients on long-term DAPT, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. The all-cause mortality rate was 0.9% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 1.5% with extended DAPT, again a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis was numerically lower with ticagrelor monotherapy, by a margin of 0.4% versus 0.8%, a nonsignificant difference.

The results were consistent regardless of which specific criteria for complex PCI a patient had or how many of them.

Results are ‘reassuring’

At a press conference where Dr. Dangas presented the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results, discussant Claire S. Duvernoy, MD, said she was “very impressed” with just how complex the PCIs were in the study participants.

“Really, these are the patients that in my own practice we’ve always been the most cautious about, the most worried about thrombotic risk, and the ones where we get down on our house staff when they drop an antiplatelet agent. So this study is very reassuring,” said Dr. Duvernoy, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She identified two key differences between TWILIGHT-COMPLEX and earlier studies that showed a benefit for extended DAPT in higher-risk patients. In the earlier studies, it was the P2Y12 inhibitor that was dropped; TWILIGHT was the first major randomized trial to discontinue the aspirin instead. And patients in the TWILIGHT study received second-generation drug-eluting stents.

“That makes a huge difference,” Dr. Duvernoy said. “We have stents now that are much safer than the old ones were, and that’s what allows us to gain this incredible benefit of reduced bleeding.”

Dr. Dangas cautioned that since this was a secondary post hoc analysis, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study must be viewed as hypothesis-generating.

The TWILIGHT trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Dangas reported receiving institutional research grants from that company as well as Bayer and Daichi-Sankyo. He also served as a paid consultant to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Biosensors.

Simultaneous with his presentation at ACC 2020, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.011).

SOURCE: Dangas GD. ACC 20, Abstract 410-09.

Patients who underwent complex PCI for acute coronary syndrome followed by 3 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor plus aspirin fared significantly better by dropping aspirin at that point in favor of long-term ticagrelor monotherapy than with continued dual-antiplatelet therapy in the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study.

The rate of clinically relevant bleeding was significantly lower at 12 months of follow-up in the ticagrelor monotherapy group than it was in patients randomized to continued DAPT. Moreover, this major benefit came at no cost in terms of ischemic events, which were actually numerically less frequent in the ticagrelor plus placebo group, George D. Dangas, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“We found that the aspirin just doesn’t add that much, even in complex patients – just bleeding complications, for the most part,” explained Dr. Dangas, professor of medicine and of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was a secondary post hoc analysis of outcomes in 2,342 participants in the previously reported larger parent TWILIGHT randomized trial who underwent complex PCI. The main TWILIGHT trial included 7,119 patients in 11 countries who underwent PCI for acute coronary syndrome, successfully completed 3 months of DAPT with ticagrelor plus aspirin without incident, and were then randomized double blind to 12 months of ticagrelor plus placebo or to another 12 months of ticagrelor and aspirin.

In the overall TWILIGHT trial, ticagrelor alone resulted in a significantly lower clinically relevant bleeding rate than did long-term ticagrelor plus aspirin, with no increase in the risk of death, MI, or stroke (N Engl J Med 2019; 381:2032-42). But the results left many interventional cardiologists wondering if a ticagrelor monotherapy strategy was really applicable to their more challenging patients undergoing complex PCI given that the risk of ischemic events is known to climb with PCI complexity. The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was specifically designed to address that concern.

To be eligible for TWILIGHT-COMPLEX, patients had to meet one or more prespecified angiographic or procedural criteria for complex PCI, such as a total stent length in excess of 60 mm, three or more treated lesions, use of an atherectomy device, or PCI of a left main lesion, a chronic total occlusion, or a bifurcation lesion with two stents. These complex PCI patients accounted for one-third of the total study population in TWILIGHT; 36% of them met more than one criteria for complex PCI.

TWILIGHT-COMPLEX findings

In the 12 months after randomization, patients who received ticagrelor plus placebo had a 4.2% incidence of clinically significant Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding, which was significantly lower than the 7.7% rate in the group on long-term DAPT and represented a 46% relative risk reduction. Severe or fatal bleeding – that is, BARC type 3 or 5 – occurred in 1.1% of those on ticagrelor monotherapy and 2.6% of the DAPT group, for a significant 59% relative risk reduction.

The composite ischemic endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke occurred in 3.6% of the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 4.8% of patients on long-term DAPT, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. The all-cause mortality rate was 0.9% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 1.5% with extended DAPT, again a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis was numerically lower with ticagrelor monotherapy, by a margin of 0.4% versus 0.8%, a nonsignificant difference.

The results were consistent regardless of which specific criteria for complex PCI a patient had or how many of them.

Results are ‘reassuring’

At a press conference where Dr. Dangas presented the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results, discussant Claire S. Duvernoy, MD, said she was “very impressed” with just how complex the PCIs were in the study participants.

“Really, these are the patients that in my own practice we’ve always been the most cautious about, the most worried about thrombotic risk, and the ones where we get down on our house staff when they drop an antiplatelet agent. So this study is very reassuring,” said Dr. Duvernoy, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She identified two key differences between TWILIGHT-COMPLEX and earlier studies that showed a benefit for extended DAPT in higher-risk patients. In the earlier studies, it was the P2Y12 inhibitor that was dropped; TWILIGHT was the first major randomized trial to discontinue the aspirin instead. And patients in the TWILIGHT study received second-generation drug-eluting stents.

“That makes a huge difference,” Dr. Duvernoy said. “We have stents now that are much safer than the old ones were, and that’s what allows us to gain this incredible benefit of reduced bleeding.”

Dr. Dangas cautioned that since this was a secondary post hoc analysis, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study must be viewed as hypothesis-generating.

The TWILIGHT trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Dangas reported receiving institutional research grants from that company as well as Bayer and Daichi-Sankyo. He also served as a paid consultant to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Biosensors.

Simultaneous with his presentation at ACC 2020, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.011).

SOURCE: Dangas GD. ACC 20, Abstract 410-09.

Patients who underwent complex PCI for acute coronary syndrome followed by 3 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor plus aspirin fared significantly better by dropping aspirin at that point in favor of long-term ticagrelor monotherapy than with continued dual-antiplatelet therapy in the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study.

The rate of clinically relevant bleeding was significantly lower at 12 months of follow-up in the ticagrelor monotherapy group than it was in patients randomized to continued DAPT. Moreover, this major benefit came at no cost in terms of ischemic events, which were actually numerically less frequent in the ticagrelor plus placebo group, George D. Dangas, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“We found that the aspirin just doesn’t add that much, even in complex patients – just bleeding complications, for the most part,” explained Dr. Dangas, professor of medicine and of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was a secondary post hoc analysis of outcomes in 2,342 participants in the previously reported larger parent TWILIGHT randomized trial who underwent complex PCI. The main TWILIGHT trial included 7,119 patients in 11 countries who underwent PCI for acute coronary syndrome, successfully completed 3 months of DAPT with ticagrelor plus aspirin without incident, and were then randomized double blind to 12 months of ticagrelor plus placebo or to another 12 months of ticagrelor and aspirin.

In the overall TWILIGHT trial, ticagrelor alone resulted in a significantly lower clinically relevant bleeding rate than did long-term ticagrelor plus aspirin, with no increase in the risk of death, MI, or stroke (N Engl J Med 2019; 381:2032-42). But the results left many interventional cardiologists wondering if a ticagrelor monotherapy strategy was really applicable to their more challenging patients undergoing complex PCI given that the risk of ischemic events is known to climb with PCI complexity. The TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study was specifically designed to address that concern.

To be eligible for TWILIGHT-COMPLEX, patients had to meet one or more prespecified angiographic or procedural criteria for complex PCI, such as a total stent length in excess of 60 mm, three or more treated lesions, use of an atherectomy device, or PCI of a left main lesion, a chronic total occlusion, or a bifurcation lesion with two stents. These complex PCI patients accounted for one-third of the total study population in TWILIGHT; 36% of them met more than one criteria for complex PCI.

TWILIGHT-COMPLEX findings

In the 12 months after randomization, patients who received ticagrelor plus placebo had a 4.2% incidence of clinically significant Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding, which was significantly lower than the 7.7% rate in the group on long-term DAPT and represented a 46% relative risk reduction. Severe or fatal bleeding – that is, BARC type 3 or 5 – occurred in 1.1% of those on ticagrelor monotherapy and 2.6% of the DAPT group, for a significant 59% relative risk reduction.

The composite ischemic endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke occurred in 3.6% of the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 4.8% of patients on long-term DAPT, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. The all-cause mortality rate was 0.9% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group and 1.5% with extended DAPT, again a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis was numerically lower with ticagrelor monotherapy, by a margin of 0.4% versus 0.8%, a nonsignificant difference.

The results were consistent regardless of which specific criteria for complex PCI a patient had or how many of them.

Results are ‘reassuring’

At a press conference where Dr. Dangas presented the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results, discussant Claire S. Duvernoy, MD, said she was “very impressed” with just how complex the PCIs were in the study participants.

“Really, these are the patients that in my own practice we’ve always been the most cautious about, the most worried about thrombotic risk, and the ones where we get down on our house staff when they drop an antiplatelet agent. So this study is very reassuring,” said Dr. Duvernoy, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She identified two key differences between TWILIGHT-COMPLEX and earlier studies that showed a benefit for extended DAPT in higher-risk patients. In the earlier studies, it was the P2Y12 inhibitor that was dropped; TWILIGHT was the first major randomized trial to discontinue the aspirin instead. And patients in the TWILIGHT study received second-generation drug-eluting stents.

“That makes a huge difference,” Dr. Duvernoy said. “We have stents now that are much safer than the old ones were, and that’s what allows us to gain this incredible benefit of reduced bleeding.”

Dr. Dangas cautioned that since this was a secondary post hoc analysis, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study must be viewed as hypothesis-generating.

The TWILIGHT trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Dangas reported receiving institutional research grants from that company as well as Bayer and Daichi-Sankyo. He also served as a paid consultant to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Biosensors.

Simultaneous with his presentation at ACC 2020, the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX results were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.011).

SOURCE: Dangas GD. ACC 20, Abstract 410-09.

FROM ACC 2020

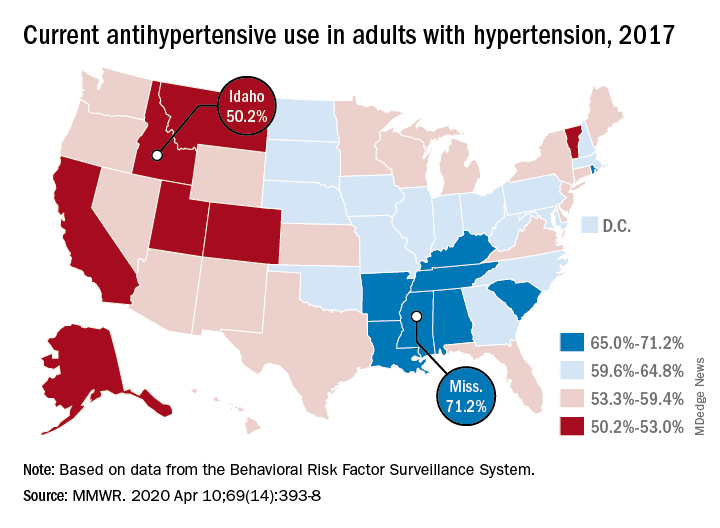

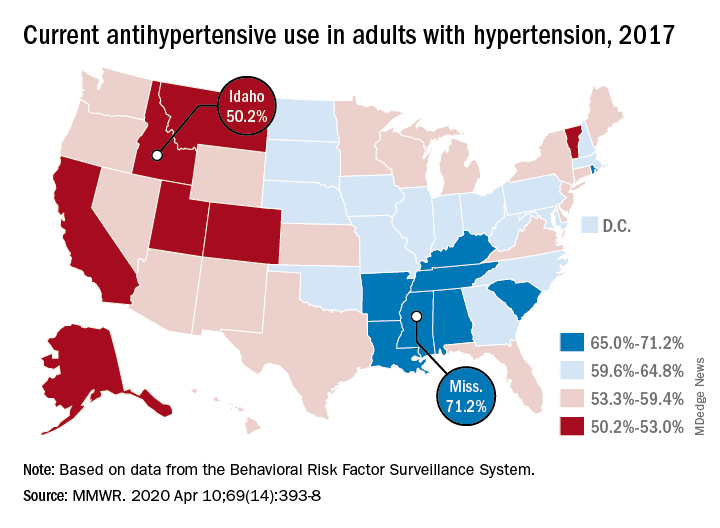

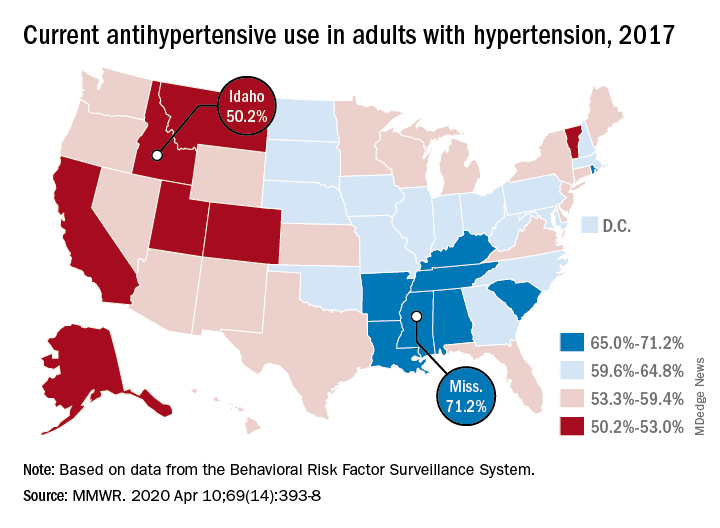

Hypertension goes unmedicated in 40% of adults

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.