User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

AI tool perfect in study of inflammatory diseases

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACR 2023

Classification identifies four stages of heart attack

Relying on more than 50 years of data on acute MI with reperfusion therapy, the society has identified the following four stages of progressively worsening myocardial tissue injury:

- Aborted MI (no or minimal myocardial necrosis).

- MI with significant cardiomyocyte necrosis but without microvascular injury.

- Cardiomyocyte necrosis and microvascular dysfunction leading to microvascular obstruction (that is, “no reflow”).

- Cardiomyocyte and microvascular necrosis leading to reperfusion hemorrhage.

The classification is described in an expert consensus statement that was published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The new classification will allow for better risk stratification and more appropriate treatment and provide refined endpoints for clinical trials and translational research, according to the authors.

Currently, all patients with acute MI receive the same treatment, even though they may have different levels of tissue injury severity, statement author Andreas Kumar, MD, chair of the writing group and associate professor of medicine at Northern Ontario School of Medicine University, Sudbury, said in an interview.

“In some cases, treatment for a mild stage 1 acute MI may be deadly for someone with stage 4 hemorrhagic MI,” said Dr. Kumar.

Technological advances

The classification is based on decades of data. “The initial data were obtained with pathology studies in the 1970s. When cardiac MRI came around, around the year 2000, suddenly there was a noninvasive imaging method where we could investigate patients in vivo,” said Dr. Kumar. “We learned a lot about tissue changes in acute MI. And especially in the last 2 to 5 years, we have learned a lot about hemorrhagic MI. So, this then gave us enough knowledge to come up with this new classification.”

The idea of classifying acute MI came to Dr. Kumar and senior author Rohan Dharmakumar, PhD, executive director of the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center at Indiana University, Indianapolis, when both were at the University of Toronto.

“This work has been years in the making,” Dr. Dharmakumar said in an interview. “We’ve been thinking about this for a long time, but we needed to get substantial layers of evidence to support the classification. We had a feeling about these stages for a long time, but that feeling needed to be substantiated.”

In 2022, Dr. Dharmakumar and Dr. Kumar observed that damage to the heart from MI was not only a result of ischemia caused by a blocked artery, but also a result of bleeding in the myocardium after the artery had been opened. Their findings were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The author of an accompanying editorial lauded the investigators “for providing new, mechanistic insights into a difficult clinical problem that has an unmet therapeutic need.”

“Hemorrhagic MI is a very dangerous injury because hemorrhage itself causes a lot of problems,” said Dr. Kumar. “We reported that there is infarct expansion after reperfusion, so once you open up the vessel, the heart attack actually gets larger. We also showed that the remodeling of these hearts is worse. These patients take a second hit with hemorrhage occurring in the myocardium.”

Classification and staging

“The standard guideline therapy for somebody who comes into the hospital is to put in a stent, open the artery, have the patient stay in the hospital for 48-72 hours, and then be released home,” said Dr. Dharmukumar. “But here’s the problem. These two patients who are going back home have different levels of injury, yet they are taking the same medications. Even inside the hospital, we have heterogeneity in mortality risk. But we are not paying attention to one patient differently than the other, even though we should, because their injuries are very different.”

The CCS classification may provide endpoints and outcome measures beyond the commonly used clinical markers, which could lead to improved treatments to help patients recover from their cardiac events.

“We have this issue of rampant heart failure in acute MI survivors. We’ve gotten really good at saving patients from immediate death, but now we are just postponing some of the serious problems survivors are going to face, said Dr. Dharmukumar. “What are we doing for these patients who are really at risk? We’ve been treating every single patient the same way and we have not been paying attention to the very different stages of injury.”

In an accompanying editorial, Prakriti Gaba, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, wrote: “There is no doubt that the classification system proposed by the investigators is important and timely, as acute MI continues to account for substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.”

Imaging and staging could be useful in guiding appropriate therapy, Bhatt said in an interview. “The authors’ hope, which I think is a very laudable one, is that more finely characterizing exactly what the extent of damage is and what the mechanism of damage is in a heart attack will make it possible to develop therapies that are particularly targeted to each of the stages,” he said.

“It is quite common to have the ability to do cardiac MRI at experienced cardiovascular centers, although this may not be true for smaller community hospitals,” Dr. Bhatt added. “But at least at larger hospitals, this will allow for much finer evaluation and assessment of exactly what is going on in that particular patient and how extensive the heart muscle damage is. Eventually, this will facilitate the development of therapies that are specifically targeted to treat each stage.”

Dr. Kumar is partly supported by a research grant from the Northern Ontario Academic Medicine Association. Dr. Dharmakumar was funded in part by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dharmakumar has an ownership interest in Cardio-Theranostics. Dr. Bhatt has served on advisory boards for Angiowave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, McKinsey, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, and Stasys. He is a member of the board of directors of or holds stock in Angiowave, Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol-Myers Squibb, DRS.LINQ, High Enroll, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, and TobeSoft. He has worked as a consultant for Broadview Ventures, and Hims. He has received honoraria from the American College of Cardiology, Arnold and Porter law firm, Baim Institute for Clinical Research, Belvoir Publications, Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group, Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute, HMP Global, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, K2P, Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD, MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME, Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute, Slack Publications, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, WebMD, and Wiley.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Relying on more than 50 years of data on acute MI with reperfusion therapy, the society has identified the following four stages of progressively worsening myocardial tissue injury:

- Aborted MI (no or minimal myocardial necrosis).

- MI with significant cardiomyocyte necrosis but without microvascular injury.

- Cardiomyocyte necrosis and microvascular dysfunction leading to microvascular obstruction (that is, “no reflow”).

- Cardiomyocyte and microvascular necrosis leading to reperfusion hemorrhage.

The classification is described in an expert consensus statement that was published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The new classification will allow for better risk stratification and more appropriate treatment and provide refined endpoints for clinical trials and translational research, according to the authors.

Currently, all patients with acute MI receive the same treatment, even though they may have different levels of tissue injury severity, statement author Andreas Kumar, MD, chair of the writing group and associate professor of medicine at Northern Ontario School of Medicine University, Sudbury, said in an interview.

“In some cases, treatment for a mild stage 1 acute MI may be deadly for someone with stage 4 hemorrhagic MI,” said Dr. Kumar.

Technological advances

The classification is based on decades of data. “The initial data were obtained with pathology studies in the 1970s. When cardiac MRI came around, around the year 2000, suddenly there was a noninvasive imaging method where we could investigate patients in vivo,” said Dr. Kumar. “We learned a lot about tissue changes in acute MI. And especially in the last 2 to 5 years, we have learned a lot about hemorrhagic MI. So, this then gave us enough knowledge to come up with this new classification.”

The idea of classifying acute MI came to Dr. Kumar and senior author Rohan Dharmakumar, PhD, executive director of the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center at Indiana University, Indianapolis, when both were at the University of Toronto.

“This work has been years in the making,” Dr. Dharmakumar said in an interview. “We’ve been thinking about this for a long time, but we needed to get substantial layers of evidence to support the classification. We had a feeling about these stages for a long time, but that feeling needed to be substantiated.”

In 2022, Dr. Dharmakumar and Dr. Kumar observed that damage to the heart from MI was not only a result of ischemia caused by a blocked artery, but also a result of bleeding in the myocardium after the artery had been opened. Their findings were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The author of an accompanying editorial lauded the investigators “for providing new, mechanistic insights into a difficult clinical problem that has an unmet therapeutic need.”

“Hemorrhagic MI is a very dangerous injury because hemorrhage itself causes a lot of problems,” said Dr. Kumar. “We reported that there is infarct expansion after reperfusion, so once you open up the vessel, the heart attack actually gets larger. We also showed that the remodeling of these hearts is worse. These patients take a second hit with hemorrhage occurring in the myocardium.”

Classification and staging

“The standard guideline therapy for somebody who comes into the hospital is to put in a stent, open the artery, have the patient stay in the hospital for 48-72 hours, and then be released home,” said Dr. Dharmukumar. “But here’s the problem. These two patients who are going back home have different levels of injury, yet they are taking the same medications. Even inside the hospital, we have heterogeneity in mortality risk. But we are not paying attention to one patient differently than the other, even though we should, because their injuries are very different.”

The CCS classification may provide endpoints and outcome measures beyond the commonly used clinical markers, which could lead to improved treatments to help patients recover from their cardiac events.

“We have this issue of rampant heart failure in acute MI survivors. We’ve gotten really good at saving patients from immediate death, but now we are just postponing some of the serious problems survivors are going to face, said Dr. Dharmukumar. “What are we doing for these patients who are really at risk? We’ve been treating every single patient the same way and we have not been paying attention to the very different stages of injury.”

In an accompanying editorial, Prakriti Gaba, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, wrote: “There is no doubt that the classification system proposed by the investigators is important and timely, as acute MI continues to account for substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.”

Imaging and staging could be useful in guiding appropriate therapy, Bhatt said in an interview. “The authors’ hope, which I think is a very laudable one, is that more finely characterizing exactly what the extent of damage is and what the mechanism of damage is in a heart attack will make it possible to develop therapies that are particularly targeted to each of the stages,” he said.

“It is quite common to have the ability to do cardiac MRI at experienced cardiovascular centers, although this may not be true for smaller community hospitals,” Dr. Bhatt added. “But at least at larger hospitals, this will allow for much finer evaluation and assessment of exactly what is going on in that particular patient and how extensive the heart muscle damage is. Eventually, this will facilitate the development of therapies that are specifically targeted to treat each stage.”

Dr. Kumar is partly supported by a research grant from the Northern Ontario Academic Medicine Association. Dr. Dharmakumar was funded in part by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dharmakumar has an ownership interest in Cardio-Theranostics. Dr. Bhatt has served on advisory boards for Angiowave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, McKinsey, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, and Stasys. He is a member of the board of directors of or holds stock in Angiowave, Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol-Myers Squibb, DRS.LINQ, High Enroll, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, and TobeSoft. He has worked as a consultant for Broadview Ventures, and Hims. He has received honoraria from the American College of Cardiology, Arnold and Porter law firm, Baim Institute for Clinical Research, Belvoir Publications, Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group, Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute, HMP Global, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, K2P, Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD, MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME, Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute, Slack Publications, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, WebMD, and Wiley.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Relying on more than 50 years of data on acute MI with reperfusion therapy, the society has identified the following four stages of progressively worsening myocardial tissue injury:

- Aborted MI (no or minimal myocardial necrosis).

- MI with significant cardiomyocyte necrosis but without microvascular injury.

- Cardiomyocyte necrosis and microvascular dysfunction leading to microvascular obstruction (that is, “no reflow”).

- Cardiomyocyte and microvascular necrosis leading to reperfusion hemorrhage.

The classification is described in an expert consensus statement that was published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The new classification will allow for better risk stratification and more appropriate treatment and provide refined endpoints for clinical trials and translational research, according to the authors.

Currently, all patients with acute MI receive the same treatment, even though they may have different levels of tissue injury severity, statement author Andreas Kumar, MD, chair of the writing group and associate professor of medicine at Northern Ontario School of Medicine University, Sudbury, said in an interview.

“In some cases, treatment for a mild stage 1 acute MI may be deadly for someone with stage 4 hemorrhagic MI,” said Dr. Kumar.

Technological advances

The classification is based on decades of data. “The initial data were obtained with pathology studies in the 1970s. When cardiac MRI came around, around the year 2000, suddenly there was a noninvasive imaging method where we could investigate patients in vivo,” said Dr. Kumar. “We learned a lot about tissue changes in acute MI. And especially in the last 2 to 5 years, we have learned a lot about hemorrhagic MI. So, this then gave us enough knowledge to come up with this new classification.”

The idea of classifying acute MI came to Dr. Kumar and senior author Rohan Dharmakumar, PhD, executive director of the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center at Indiana University, Indianapolis, when both were at the University of Toronto.

“This work has been years in the making,” Dr. Dharmakumar said in an interview. “We’ve been thinking about this for a long time, but we needed to get substantial layers of evidence to support the classification. We had a feeling about these stages for a long time, but that feeling needed to be substantiated.”

In 2022, Dr. Dharmakumar and Dr. Kumar observed that damage to the heart from MI was not only a result of ischemia caused by a blocked artery, but also a result of bleeding in the myocardium after the artery had been opened. Their findings were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The author of an accompanying editorial lauded the investigators “for providing new, mechanistic insights into a difficult clinical problem that has an unmet therapeutic need.”

“Hemorrhagic MI is a very dangerous injury because hemorrhage itself causes a lot of problems,” said Dr. Kumar. “We reported that there is infarct expansion after reperfusion, so once you open up the vessel, the heart attack actually gets larger. We also showed that the remodeling of these hearts is worse. These patients take a second hit with hemorrhage occurring in the myocardium.”

Classification and staging

“The standard guideline therapy for somebody who comes into the hospital is to put in a stent, open the artery, have the patient stay in the hospital for 48-72 hours, and then be released home,” said Dr. Dharmukumar. “But here’s the problem. These two patients who are going back home have different levels of injury, yet they are taking the same medications. Even inside the hospital, we have heterogeneity in mortality risk. But we are not paying attention to one patient differently than the other, even though we should, because their injuries are very different.”

The CCS classification may provide endpoints and outcome measures beyond the commonly used clinical markers, which could lead to improved treatments to help patients recover from their cardiac events.

“We have this issue of rampant heart failure in acute MI survivors. We’ve gotten really good at saving patients from immediate death, but now we are just postponing some of the serious problems survivors are going to face, said Dr. Dharmukumar. “What are we doing for these patients who are really at risk? We’ve been treating every single patient the same way and we have not been paying attention to the very different stages of injury.”

In an accompanying editorial, Prakriti Gaba, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, wrote: “There is no doubt that the classification system proposed by the investigators is important and timely, as acute MI continues to account for substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.”

Imaging and staging could be useful in guiding appropriate therapy, Bhatt said in an interview. “The authors’ hope, which I think is a very laudable one, is that more finely characterizing exactly what the extent of damage is and what the mechanism of damage is in a heart attack will make it possible to develop therapies that are particularly targeted to each of the stages,” he said.

“It is quite common to have the ability to do cardiac MRI at experienced cardiovascular centers, although this may not be true for smaller community hospitals,” Dr. Bhatt added. “But at least at larger hospitals, this will allow for much finer evaluation and assessment of exactly what is going on in that particular patient and how extensive the heart muscle damage is. Eventually, this will facilitate the development of therapies that are specifically targeted to treat each stage.”

Dr. Kumar is partly supported by a research grant from the Northern Ontario Academic Medicine Association. Dr. Dharmakumar was funded in part by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dharmakumar has an ownership interest in Cardio-Theranostics. Dr. Bhatt has served on advisory boards for Angiowave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, McKinsey, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, and Stasys. He is a member of the board of directors of or holds stock in Angiowave, Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol-Myers Squibb, DRS.LINQ, High Enroll, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, and TobeSoft. He has worked as a consultant for Broadview Ventures, and Hims. He has received honoraria from the American College of Cardiology, Arnold and Porter law firm, Baim Institute for Clinical Research, Belvoir Publications, Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group, Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute, HMP Global, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, K2P, Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD, MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME, Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute, Slack Publications, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, WebMD, and Wiley.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY

Potential dapagliflozin benefit post MI is not a ‘mandate’

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

AT AHA 2023

Long COVID and mental illness: New guidance

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of mental health symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, was published online in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the journal of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R).

The statement was developed by a task force that included experts from physical medicine, neurology, neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and primary care. It is the eighth guidance statement on long COVID published by AAPM&R).

“Many of our patients have reported experiences in which their symptoms of long COVID have been dismissed either by loved ones in the community, or also amongst health care providers, and they’ve been told their symptoms are in their head or due to a mental health condition, but that’s simply not true,” Abby L. Cheng, MD, a physiatrist at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and a coauthor of the new guidance, said in a press briefing.

“Long COVID is real, and mental health conditions do not cause long COVID,” Dr. Cheng added.

Millions of Americans affected

Anxiety and depression have been reported as the second and third most common symptoms of long COVID, according to the guidance statement.

There is some evidence that the body’s inflammatory response – specifically, circulating cytokines – may contribute to the worsening of mental health symptoms or may bring on new symptoms of anxiety or depression, said Dr. Cheng. Cytokines may also affect levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin, she said.

Researchers are also exploring whether the persistence of virus in the body, miniature blood clots in the body and brain, and changes to the gut microbiome affect the mental health of people with long COVID.

Some mental health symptoms – such as fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbances, and tachycardia – can mimic long COVID symptoms, said Dr. Cheng.

The treatment is the same for someone with or without long COVID who has anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other mental health conditions and includes treatment of coexisting medical conditions, supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacologic interventions, she said.

“Group therapy may have a particular role in the long COVID population because it really provides that social connection and awareness of additional resources in addition to validation of their experiences,” Dr. Cheng said.

The guidance suggests that primary care practitioners – if it’s within their comfort zone and they have the training – can be the first line for managing mental health symptoms.

But for patients whose symptoms are interfering with functioning and their ability to interact with the community, the guidance urges primary care clinicians to refer the patient to a specialist.

“It leaves the door open to them to practice within their scope but also gives guidance as to how, why, and who should be referred to the next level of care,” said Dr. Cheng.

Coauthor Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at UT Health San Antonio, Texas, said that although fewer people are now getting long COVID, “it’s still an impactful number.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 7% of American adults (18 million) and 1.3% of children had experienced long COVID.

Dr. Gutierrez said that it’s an evolving number, as some patients who have a second or third or fourth SARS-CoV-2 infection experience exacerbations of previous bouts of long COVID or develop long COVID for the first time.

“We are still getting new patients on a regular basis with long COVID,” said AAPM&R President Steven R. Flanagan, MD, a physical medicine specialist.

“This is a problem that really is not going away. It is still real and still ever-present,” said Dr. Flanagan, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PHYSICAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION

In MI with anemia, results may favor liberal transfusion: MINT

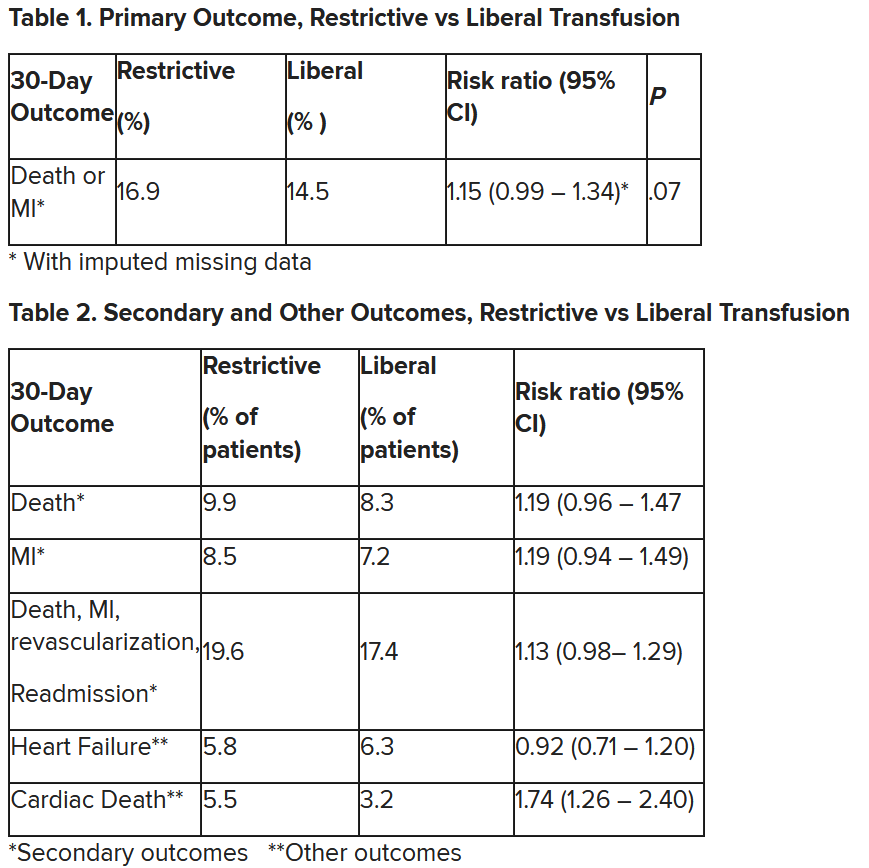

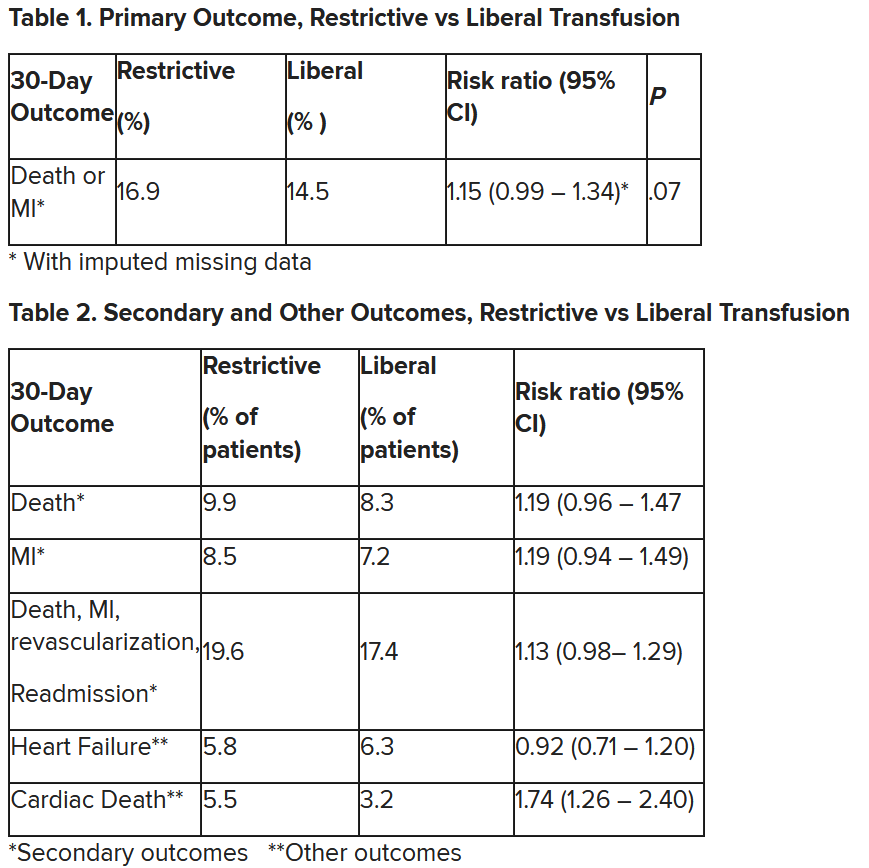

In patients with myocardial infarction and anemia, a “liberal” red blood cell transfusion strategy did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent MI or death within 30 days, compared with a “restrictive” transfusion strategy, in the 3,500-patient MINT trial.

Jeffrey L. Carson, MD, from Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in a press briefing.

He presented the study in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and it was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Whether to transfuse is an everyday decision faced by clinicians caring for patients with acute MI,” Dr. Carson said.

“We cannot claim that a liberal transfusion strategy is definitively superior based on our primary outcome,” he said, but “the 95% confidence interval is consistent with treatment effects corresponding to no difference between the two transfusion strategies and to a clinically relevant benefit with the liberal strategy.”

“In contrast to other trials in other settings,” such as anemia and cardiac surgery, Dr. Carson said, “the results suggest that a liberal transfusion strategy has the potential for clinical benefit with an acceptable risk of harm.”

“A liberal transfusion strategy may be the most prudent approach to transfusion in anemic patients with MI,” he added.

Not a home run

Others agreed with this interpretation. Martin B. Leon, MD, from Columbia University, New York, the study discussant in the press briefing, said the study “addresses a question that is common” in clinical practice. It was well conducted, and international (although most patients were in the United States and Canada), in a very broad group of patients, designed to make the results more generalizable. The 98% follow-up was extremely good, Dr. Leon added, and the trialists achieved their goal in that they did show a difference between the two transfusion strategies.

The number needed to treat was 40 to see a benefit in the combined outcome of death or recurrent MI at 30 days, Dr. Leon said. The P value for this was .07, “right on the edge” of statistical significance.

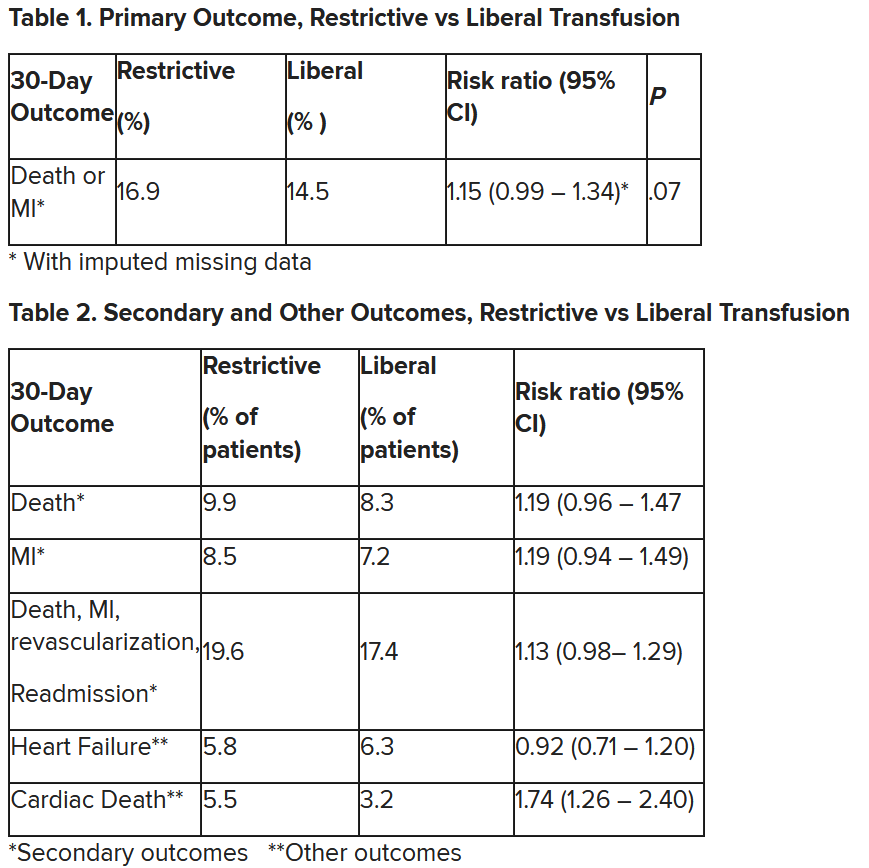

This study is “not a home run,” for the primary outcome, he noted; however, many of the outcomes tended to be in favor of a liberal transfusion strategy. Notably, cardiovascular death, which was not a specified outcome, was significantly lower in the group who received a liberal transfusion strategy.

Although a liberal transfusion strategy was “not definitely superior” in these patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Carson said, he thinks the trial will be interpreted as favoring a liberal transfusion strategy.

C. Michael Gibson, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard’s Baim and PERFUSE institutes for clinical research, voiced similar views.

“Given the lack of acute harm associated with liberal transfusion and the preponderance of evidence favoring liberal transfusion in the largest trial to date,” concluded Dr. Gibson, the assigned discussant at the session, “liberal transfusion appears to be a viable management strategy, particularly among patients with non-STEMI type 1 MI and as clinical judgment dictates.”

Only three small randomized controlled trials have compared transfusion thresholds in a total of 820 patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Gibson said, a point that the trial investigators also made. The results were inconsistent between trials: the CRIT trial (n = 45) favored a restrictive strategy, the MINT pilot study (n = 110) favored a liberal one, and the REALITY trial (n = 668) showed noninferiority of a restrictive strategy, compared with a liberal strategy in 30-day MACE.

The MINT trial was four times larger than all prior studies combined. However, most outcomes were negative or of borderline significance for benefit.

Cardiac death was more common in the restrictive group at 5.5% than the liberal group at 3.2% (risk ratio, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.26-2.40), but this was nonadjudicated, and not designated as a primary, secondary, or tertiary outcome – which the researchers also noted. Fewer than half of the deaths were classified as cardiac, which was “odd,” Dr. Gibson observed.

A restrictive transfusion strategy was associated with increased events among participants with type 1 MI (RR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.04-1.67), he noted.

Study strengths included that 45.5% of participants were women, Dr. Gibson said. Limitations included that the trial was “somewhat underpowered.” Also, even in the restrictive group, participants received a mean of 0.7 units of packed red blood cells.

Adherence to the 10 g/dL threshold in the liberal transfusion group was moderate (86.3% at hospital discharge), which the researchers acknowledged. They noted that this was frequently caused by clinical discretion, such as concern about fluid overload, and to the timing of hospital discharge. In addition, long-term potential for harm (microchimerism) is not known.

“There was a consistent nonsignificant acute benefit for liberal transfusion and a nominal reduction in CV mortality and improved outcomes in patients with type 1 MI in exploratory analyses, in a trial that ended up underpowered,” Dr. Gibson summarized. “Long-term follow up would be helpful to evaluate chronic outcomes.”

This is a very well-conducted, high-quality, important study that will be considered a landmark trial, C. David Mazer, MD, University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital, also in Toronto, said in an interview.

Unfortunately, “it was not as definitive as hoped for,” Dr. Mazer lamented. Nevertheless, “I think people may interpret it as providing support for a liberal transfusion strategy” in patients with anemia and MI, he said.

Dr. Mazer, who was not involved with this research, was a principal investigator on the TRICS-3 trial, which disputed a liberal RBC transfusion strategy in patients with anemia undergoing cardiac surgery, as previously reported.

The “Red Blood Cell Transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines,” led by Dr. Carson and published in JAMA, recommend a restrictive strategy in stable patients, although these guidelines did not include the current study, Dr. Mazer observed.

In the REALITY trial, there were fewer major adverse cardiac events (MACE) events in the restrictive strategy, he noted.

MINT can be viewed as comparing a high versus low hemoglobin threshold. “It is possible that the best is in between,” he said.

Dr. Mazer also noted that MINT may have achieved significance if it was designed with a larger enrollment and a higher power (for example, 90% instead of 80%) to detect between-group difference for the primary outcome.

Study rationale, design, and findings

Anemia, or low RBC count, is common in patients with MI, Dr. Carson noted. A normal hemoglobin is 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women. Administering a packed RBC transfusion only when a patient’s hemoglobin falls below 7 or 8 g/dL has been widely adopted, but it is unclear if patients with acute MI may benefit from a higher hemoglobin level.

“Blood transfusion may decrease ischemic injury by improving oxygen delivery to myocardial tissues and reduce the risk of reinfarction or death,” the researchers wrote. “Alternatively, administering more blood could result in more frequent heart failure from fluid overload, infection from immunosuppression, thrombosis from higher viscosity, and inflammation.”

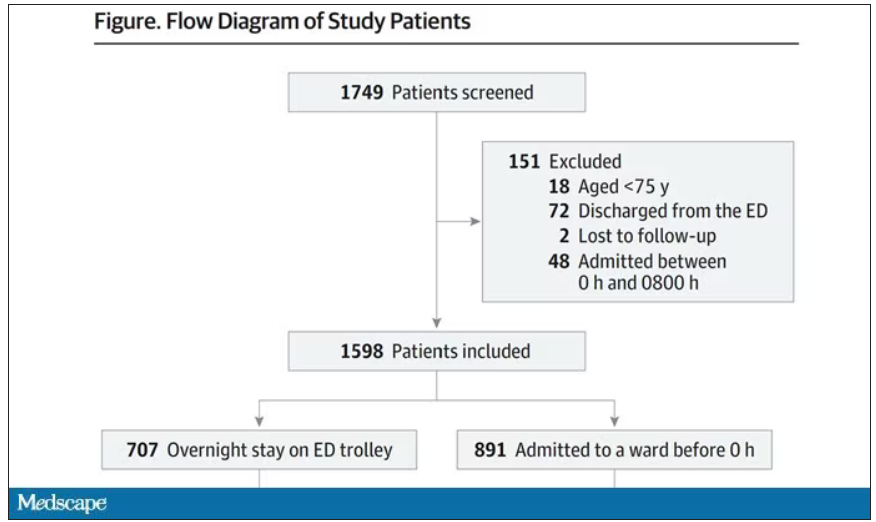

From 2017 to 2023, investigators enrolled 3,504 adults aged 18 and older at 144 sites in the United States (2,157 patients), Canada (885), France (323), Brazil (105), New Zealand (25), and Australia (9).

The participants had ST-elevation or non–ST-elevation MI and hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL within 24 hours. Patients with type 1 (atherosclerotic plaque disruption), type 2 (supply-demand mismatch without atherothrombotic plaque disruption), type 4b, or type 4c MI were eligible.

They were randomly assigned to receive:

- A ‘restrictive’ transfusion strategy (1,749 patients): Transfusion was permitted but not required when a patient’s hemoglobin was less than 8 g/dL and was strongly recommended when it was less than 7 g/dL or when anginal symptoms were not controlled with medications.

- A ‘liberal’ transfusion strategy (1,755 patients): One unit of RBCs was administered after randomization, and RBCs were transfused to maintain hemoglobin 10 g/dL or higher until hospital discharge or 30 days.

The patients had a mean age of 72 years and 46% were women. More than three-quarters (78%) were White and 14% were Black. They had frequent coexisting illnesses, about a third had a history of MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, or heart failure; 14% were on a ventilator and 12% had renal dialysis. The median duration of hospitalization was 5 days in the two groups.

At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL in both groups. At days 1, 2, and 3, the mean hemoglobin was 8.8, 8.9, and 8.9 g/dL, respectively, in the restrictive transfusion group, and 10.1, 10.4, and 10.5 g/dL, respectively, in the liberal transfusion group.

The mean number of transfused blood units was 0.7 units in the restrictive strategy group and 2.5 units in the liberal strategy group, roughly a 3.5-fold difference.

After adjustment for site and incomplete follow-up in 57 patients (20 with the restrictive strategy and 37 with the liberal strategy), the estimated RR for the primary outcome in the restrictive group versus the liberal group was 1.15 (P = .07).

“We observed that the 95% confidence interval contains values that suggest a clinical benefit for the liberal transfusion strategy and does not include values that suggest a benefit for the more restrictive transfusion strategy,” the researchers wrote. Heart failure and other safety outcomes were comparable in the two groups.

The trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the Canadian Blood Services and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health. Dr. Carson, Dr. Leon, Dr. Gibson, and Dr. Mazer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with myocardial infarction and anemia, a “liberal” red blood cell transfusion strategy did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent MI or death within 30 days, compared with a “restrictive” transfusion strategy, in the 3,500-patient MINT trial.

Jeffrey L. Carson, MD, from Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in a press briefing.

He presented the study in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and it was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Whether to transfuse is an everyday decision faced by clinicians caring for patients with acute MI,” Dr. Carson said.

“We cannot claim that a liberal transfusion strategy is definitively superior based on our primary outcome,” he said, but “the 95% confidence interval is consistent with treatment effects corresponding to no difference between the two transfusion strategies and to a clinically relevant benefit with the liberal strategy.”

“In contrast to other trials in other settings,” such as anemia and cardiac surgery, Dr. Carson said, “the results suggest that a liberal transfusion strategy has the potential for clinical benefit with an acceptable risk of harm.”

“A liberal transfusion strategy may be the most prudent approach to transfusion in anemic patients with MI,” he added.

Not a home run

Others agreed with this interpretation. Martin B. Leon, MD, from Columbia University, New York, the study discussant in the press briefing, said the study “addresses a question that is common” in clinical practice. It was well conducted, and international (although most patients were in the United States and Canada), in a very broad group of patients, designed to make the results more generalizable. The 98% follow-up was extremely good, Dr. Leon added, and the trialists achieved their goal in that they did show a difference between the two transfusion strategies.

The number needed to treat was 40 to see a benefit in the combined outcome of death or recurrent MI at 30 days, Dr. Leon said. The P value for this was .07, “right on the edge” of statistical significance.

This study is “not a home run,” for the primary outcome, he noted; however, many of the outcomes tended to be in favor of a liberal transfusion strategy. Notably, cardiovascular death, which was not a specified outcome, was significantly lower in the group who received a liberal transfusion strategy.

Although a liberal transfusion strategy was “not definitely superior” in these patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Carson said, he thinks the trial will be interpreted as favoring a liberal transfusion strategy.

C. Michael Gibson, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard’s Baim and PERFUSE institutes for clinical research, voiced similar views.

“Given the lack of acute harm associated with liberal transfusion and the preponderance of evidence favoring liberal transfusion in the largest trial to date,” concluded Dr. Gibson, the assigned discussant at the session, “liberal transfusion appears to be a viable management strategy, particularly among patients with non-STEMI type 1 MI and as clinical judgment dictates.”

Only three small randomized controlled trials have compared transfusion thresholds in a total of 820 patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Gibson said, a point that the trial investigators also made. The results were inconsistent between trials: the CRIT trial (n = 45) favored a restrictive strategy, the MINT pilot study (n = 110) favored a liberal one, and the REALITY trial (n = 668) showed noninferiority of a restrictive strategy, compared with a liberal strategy in 30-day MACE.

The MINT trial was four times larger than all prior studies combined. However, most outcomes were negative or of borderline significance for benefit.

Cardiac death was more common in the restrictive group at 5.5% than the liberal group at 3.2% (risk ratio, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.26-2.40), but this was nonadjudicated, and not designated as a primary, secondary, or tertiary outcome – which the researchers also noted. Fewer than half of the deaths were classified as cardiac, which was “odd,” Dr. Gibson observed.

A restrictive transfusion strategy was associated with increased events among participants with type 1 MI (RR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.04-1.67), he noted.